Abstract

Introduction:

Families with multiple and complex problems often deal with multiple professionals and organizations for support. Integrated social care supposedly prevents the fragmentation of care that often occurs.We identified facilitators and barriers experienced by families receiving integrated social care and by the professionals who provide it.

Method:

We performed a scoping review following Arksey and O’Malley’s framework, using the following databases: PsycINFO, Web of Science Core Collection, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, CINAHL, PubMed, and Medline. Furthermore, conducted a thematic analysis. The results were divided into facilitators and barriers of integrated social care.

Results:

We identified 278 studies and finally included sixteen in our scoping review. We identified facilitators, including: linking formal care with informal networks, promoting collaboration among professionals e.g., working in pairs, and professionals autonomy. We identified barriers, including: time constraints, tasks outside professionals’ expertise, along with resistance to integrated collaboration among organizations. These findings can enhance the advancement of social integrated care as a promising approach to support families facing multiple and complex problems.

Conclusion:

To empower families, integrated social care requires a systematic approach based on trust. It involves coordinated care, shared decision-making, informal networks and the participation of all family members, including children.

Keywords: families with multiple and complex problems, multi-problem families, integrated social care, integrated care, multi-agency working, interdisciplinary collaboration, fragmentation of care

Introduction

Families facing multiple and complex problems often deal with severe, chronic difficulties and multiple stressors. Problems frequently accumulate and interact with each other in different areas of life are, for example, poor family functioning, parenting problems, (mental) health, financial problems, and substance abuse [1]. In the literature, various terms are used to identify families that encounter such difficulties, for example, multi-problem families; multi-stressed families; multi-crisis families; and multi-assisted families [2]. Although the terms slightly differ in nature, it is generally agreed that they concern families experiencing multiple and complex problems [3,4]. Although all these names serve the same target group. In this study we used the following definition for families with multiple and complex problems: “families who suffers long-term combined socio-economic and psychosocial problems, which manifest themselves in various areas within the family” [5].

Because of the complexity and interconnectedness of the problems these families encounter, support from a single professional is often insufficient [3]. As a consequence, families often receive support from social workers, youth professionals, counsellors, (mental) healthcare providers, psychologists, psychiatrists, teachers, and nurses from different service organizations. These professionals often tend to work from their own area of expertise and therefore focus on a specific problem [6]. While it would be preferable for social care to be inherently integrated, this often is not the case highlighting the fragmented nature of social care services. Social care often operate in silos with limited coordination and collaboration among different service providers and sectors [6].

This is considered a risk since it is well known that care is not always well coordinated and can lead to fragmentation of care and support in this case for families already much in need of support. This fragmentation means that professionals do not know each other what they are doing and that they work past each other [7,8,9]. As a consequence fragmentation jeopardizes successful treatment, decreases client satisfaction, and limits the effectiveness of the support [8]. Furthermore, with multiple professionals each focusing on a specific problem, there is a risk that some issues may be overlooked [10]. This has negative consequences for the quality of care, disproportionate use of scarce services, and high costs for social care systems [8,11,12,13]. Integrated care in general is suggested as a promising approach to counteract the fragmentation of care [14], despite the use of different operationalizations and definitions [15,16,17,18].

A frequently used version of integrated care is as follows: “An approach to strengthen people-centered health systems through the promotion of the comprehensive delivery of quality services across the life-course, designed according to the multi-dimensional needs of the population and the individual and delivered by a coordinated multidisciplinary team of providers working across settings and levels of care” [13]. In this study we applied this in social care: Integrated Social Care. Here, the focus is on integrated care among social services, distinct from for instance its integration with medical care, primarily to enhance the delivery of the complex social care for families facing multiple and complex problems.

Much is known in the literature from barriers and facilitators about integrated care in general, with a focus on medical care [19]. Studies have for instance shown that integrated care is associated with improved quality of care and increased client satisfaction [10]. We could not identify such studies for integrated social care. Therefore, we focussed on barriers and facilitators of integrated social care departing from the above-mentioned definition of integrated care. Integrated social care resonates with the definition of integrated healthcare, sharing core elements and similarities such as comprehensiveness, (care) coordination, cooperation between professionals and organizations, partnership, and holism, to improve care, health and well-being [13]. Furthermore, integrated social care in its broadest sense can come from a variety of professional sources, as well as informal resources such as family and friends [8].

Although there is research into one or more factors that contribute to integrated social care, knowledge about this is also fragmented. For instance, research focuses specifically on youth care rather than integrated care with other domains within social care [1]. Other research focuses specifically on care coordination for vulnerable families which is only an aspect of integrated social care. [20]. Comprehensive knowledge about barriers an facilitators for social integrated care for families with multiple and complex problems so far is lacking. In addition, existing literature pays attention to integrated care, but not specifically to the social domain of integrated care. Therefore, study aims to identify facilitators and barriers for families receiving integrated social care and for professionals, policymakers and researchers to improve providing integrated social care in practice and research.

We formulated the following research questions: What are facilitators and barriers for integrated care within the context of social care for families facing multiple and complex problems who receive this care and for professionals who provide it?

Methods

We performed a scoping literature review following the PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews [21]. Our aim was to provide an overview of the existing literature in order to identify these facilitators and barriers [22].

We conducted a literature search, selection, and synthesis of existing knowledge to chart key concepts, types of evidence, and research gaps related to facilitators and barriers in integrated social care, as perceived by both families and professionals [22]. For this we used the six-stage process of the scoping review framework originally developed by Arksey and O’Malley [23], with additional recommendations from Levac et al. [24].

Stage 1. Identifying the research questions fewer

To answer the research question, we identified facilitators and barriers in integrated social care for families and professionals and we provide an overview of the relevant literature and considered the purpose of this scoping review, as described in the introduction.

Stage 2. Identifying relevant studies

To identify the relevant literature, we searched the following databases: PsycINFO, Web of Science Core Collection, Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, CINAHL, PubMed, and Medline in the period December 2022-October 2023.

The search was performed with an alternate combination of Boolean search operators (AND/OR; Table 1). We supplemented this search with manual searches of reference lists of the identified articles. In our scoping review, we employed the PICO framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) [25] to construct the search string. Since this study does not involve a comparison between interventions, the ‘C’ component was excluded. Additionally, trial and error revealed that including the ‘O’ (Outcome) component resulted in less relevant articles, leading to its exclusion as well. The search rule was composed by the first author MvE and the second author RE.

Table 1.

Selection criteria.

|

| |

|---|---|

| INCLUSION CRITERIA | EXCLUSION CRITERIA |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

See appendix 1. Database search overview.

Stage 3. Study selection

The data screening program Rayyan QCRI was used to select the articles [26]. The selected articles were arranged by author(s), the year of publication, and the contribution to the research question. The results were mapped at the family and professional level to elucidate what is currently known about integrated social care for families experiencing multiple and complex problems. For both levels, we used inductive reasoning to identify overarching themes. The definition of integrated social care as defined in the introduction serves as a central concept, and so does the concept of families with multiple and complex problems. The inclusion and exclusion criteria in Table 1 have been drawn up to select the articles.

The studies were selected and categorized by MvE. Any doubts about whether an article should be included were discussed with RE.

Stage 4. Charting the data

We first mapped the first author, the year of publication, the study location, and the study design. The results were then classified into facilitators and barriers. Table 2 provides a summary of the data:

Table 2.

Summary of the data.

|

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STUDY DESIGN | COUNTRY | FACILITATORS FOR FAMILIES | BARRIERS FOR FAMILIES | FACILITATORS FOR PROFESSIONALS | BARRIERS FOR PROFESSIONALS | |

|

| ||||||

| Serbati, et al, 2016 [29] | Pre- and post-test design (qualitative and quantitative) | Italy |

|

gap between social services

|

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Eastwood et al, 2020 [30] | Realist evaluation | Australia |

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Eastwood et al, 2020 [31] | Realist evaluation | Australia |

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Tennant et al, 2020 [32] | Realist evaluation | Australia |

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Nooteboom et al, 2020 [33] | Qualitative | Netherlands |

|

|

||

|

| ||||||

| Morris 2013 [34] | Qualitative | United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Bachler et al, 2016 [35] | Pre/post-naturalistic | Austria/Germany |

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Onyskiw et al, 1999 [36] | Descriptive/evaluative | Canada |

|

- home visits not always seen as positive by clients - project operated during business hours |

||

|

| ||||||

| Sousa 2005 [37] | Qualitative/explorative | Portugal |

|

|

||

|

| ||||||

| Lawick et al, (2008) [38] | Qualitative | The Netherlands |

|

|

||

|

| ||||||

| Bachler et al, (2017) [39] | Naturalistic | Austria |

|

|

||

|

| ||||||

| Thoburn et al, (2013) [40] | Ethnographic | United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Nooteboom et al, (2020a) [41] | Qualitative | The Netherlands |

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Sousa & Rodrigues (2009) [42] | Qualitative | Portugal |

|

|

||

|

| ||||||

| Nadeau et al, (2012) [43] | Qualitative Participatory | Canada |

|

|

||

|

| ||||||

| Tausenfreund et al, (2014) [44] | Prospective one-group repeated measures outcome |

The Netherlands |

|

|

||

|

| ||||||

Facilitators of and barriers to integrated social care amongst families with multiple and complex problems;

Facilitators of and barriers to integrated social care amongst professionals.

Stage 5. Collating, summarizing, and reporting results

A critical appraisal of qualitative and quantitative research was carried out using Treloar et al. Butcher et al. [27,28 Appendix 2]. We than performed a qualitative thematic analysis by coding the results according to different themes. We searched for recognizable patterns in the data and distilled seven themes with regard to families and seven themes with regard to professionals. See Table 2 for the facilitators and barriers within the two sets of seven themes.

Stage 6. Consultation

The content of the studies was assessed and discussed with two authors (MC and TvR) who have expertise in this area.

Results

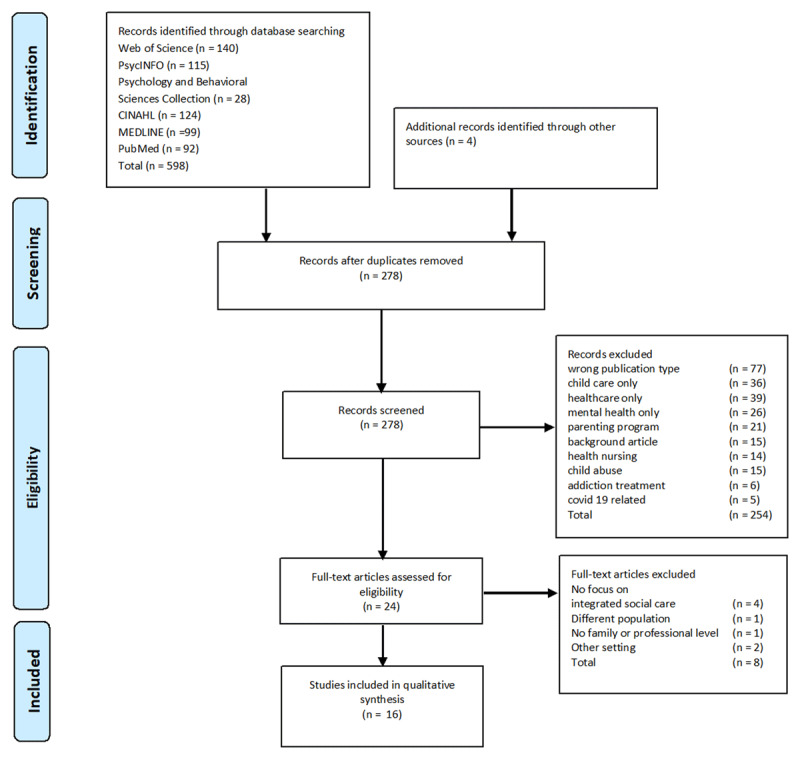

A total of 598 articles were initially identified, and after removing the duplicates, 278 remained. Four articles were found through a manual search. After screening titles and abstracts, 254 were excluded. The 24 remaining articles were read in full and eight articles were excluded because they did not fit the inclusion criteria. Finally sixteen articles were selected. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study.

The data from the articles comprised facilitators of and barriers to integrated social care amongst families and professionals (see Table 2).

Facilitators of and barriers to integrated social care amongst families

The studies identify a large number of facilitators and barriers that influenced the reception of integrated social care amongst families experiencing multiple and complex problems. By ‘amongst families’, it is meant that these barriers and facilitators are described from the perspective of families. We identified the following seven principal themes.

(Mis)match between families and social services

The gap between the real-life experience of families and the world of social services acts as a barrier to integrated social care. This can leave parents feeling confused and powerless [29], leading to mistrust [30,31,32] and negatively impacting the acceptance of integrated social care. Parents also perceive a limited freedom of choice in the support they receive [33], leading to a diminished sense of control.

Understanding the daily lives of families is considered to be facilitative [34] because engaging with families on their terms and beyond professional duties helps bridge the gap between their lived experience and the world of social services [32]. However, professionals may struggle to balance their responsibilities and display empathy, which can be a barrier [31].

Understanding the daily lives of families experiencing multiple and complex problems and offering practical help provided is considered a facilitator [34] because the families feel that the professionals are meeting them on their own terms [32]. Also, the literature indicates that professionals who show their appreciation to family members by acting outside their duties strengthen the collaboration [32], though it can be difficult to delineate the dividing line between their professional role and the degree of empathy required [31].

A relationship built on trust and collaboration

A facilitator of integrated social care is a collaborative relationship between family members and professionals, as well as formal and informal partners. Relationship-building takes time, particularly at the beginning of the support process [35]. Family members are not always immediately open to integrated social care, which acts as a two-way barrier [35]. Facilitators strengthening a collaborative relationship from the perspective of the family are an informal, accepting, non-threatening, and non-judgemental attitude from the professional [36]. Several of the studies point out that a relationship built on trust between professionals and families is a crucial facilitator [31,32,34,35,37]. Families appreciate professionals who are likeable and approachable [33], who exhibit an informal, accepting, non-threatening, and non-judgemental attitude, who address problems promptly, and who help to reduce stress [36]. It should also be noted that, because building relationships takes time, family members may be resistant to the integrated social care approach, which can create a barrier for professionals [35].

Another specific facilitator for integrated social care and collaboration is asking for feedback; this helps families to take the initiative and make a commitment to change. Humour can put problems into perspective and strengthen collaboration [38].

Hope and self-reliance

Professional support that helps families to develop a positive outlook and a sense of self-reliance and control are facilitative because such attributes reinforce collaborative goal-setting and the likelihood of positive outcomes. However, feelings of hopelessness act as a barrier to successful integrated social care [35].

Addressing problems in multiple areas of life

Integrated social care aims to address problems across various areas of life simultaneously. The research suggests that when this happens, it facilitates positive experiences of integrated social care, both for families and professionals [29,33,35,39,40,41].

However, the process presents challenges for families and professionals in terms of the prioritization and management of problems [41]. Additionally, too many treatment goals can overburden parents and lead to a decline in motivation and self-efficacy [33,34].

Systemic approach within the family and the informal social network

An important facilitator of integrated social care is a systemic approach where the family constitutes a system rather than a collection of individuals [33,35,40]. Both parents and professionals consider a systemic approach to be an important ingredient of integrated social care [33,41]. Various studies reveal that a social network approach involving other stakeholders leads to successful integrated social care, but an informal network can also be facilitative [37]. Thus, informal social support (e.g., family and friends) can relieve stress and provide support by assisting in the development of personal coping and parenting skills [36].

For the family, an informal network might be a more important source of support than the formal one, though a combination of the two makes it that much easier to overcome adversity [37]. Several of the studies argue that family members can benefit from building a reciprocal relationship within an informal network by involving family members, friends, or neighbours alongside the formal setup [32,35,42]. Informal networks can offer emotional support, which then creates a space wherein families become more open to other forms of help [38].

A potential barrier to informal networks includes difficulties in maintaining reciprocal relationships with others [42] and overburdened social ties. Moreover, parents do not always perceive informal networks as beneficial [33].

In turn, the extensive involvement of professionals in the social network can be a barrier because it can place too much responsibility on them; consequently, ownership does not reside within the families themselves or their personal networks [37].

The literature demonstrates that a systemic approach, involving all family members rather than individuals, is a key facilitator of integrated social care [33,35,40]. This is recognized by both parents and professionals [33,41]. Many of the studies argue that informal networks are an essential aspect of integrated social care [30,33,34,35,37,39,40,41,42]. Emotional support from family members, friends, and neighbours helps to create openness to other forms of help [38], guide families towards formal support [38], provide stress relief, and enhance coping and parenting skills [36]. Establishing mutual relationships within the informal network is a key aspect of integrated social care [32,35,42].

However, families may have limited or unsupportive social networks [42]. Preventing the overload of social networks can also be a challenge, and not all parents perceive them as beneficial [33]. Extensive involvement of professionals in the social network can hinder familial ownership and a sense of responsibility [38]. Finally, the fragmentation of care amongst formal and informal stakeholders is recognized as a barrier to successful integrated social care [42].

Shared decision-making

Several of the studies reveal that shared decision-making is an important facilitator from the family perspective [30,31,33]. Prioritizing problems with the professionals and up-to-date care plans are facilitative for many parents [33,41]. The professionals can then discuss the needs of the families in a comprehensive manner [29].

Home visits

Home visits create opportunities for successful integrated social care, especially when the professionals involved take a collaborative and egalitarian position [38,41]. Notwithstanding, home visits can sometimes cause discomfort and lead to a loss of control on the part of the families [36].

Facilitators of and barriers to integrated social care amongst professionals

We also identified a large number of both facilitators and barriers that influenced the reception of integrated social care amongst professionals. By ‘amongst professionals’, it is meant that these barriers and facilitators are described from the perspective of professionals. There are seven principal themes.

Interprofessional collaboration

Shared professional learning can serve as a facilitator [32], along with multi-professional decision-making [29,31]. Warm handoffs between professionals are perceived as a facilitator of integrated social care from the perspective of parents and professionals [33,41]. Meanwhile, case discussions that are overly focused on crises [41]; difficulties in interprofessional collaboration [41]; privacy issues regarding the sharing of information [30,32,33]; and a lack of familiarity with other institutions can form barriers to interprofessional collaboration [43]. Also, in many cases, parents have reported a lack of clarity in service provision and the specific demands of organizations [33]. Professionals who have to compromise with child welfare workers can come into conflict with parents, and this in turn can hinder collaboration [32].

Shared professional learning and multi-professional decision-making facilitate the provision of integrated social care [29,31,32,34], though case discussions that prioritize crises can be a barrier to both professionals and parents [41]. Difficulties in interprofessional collaboration, which may arise from professionals having to operate within separate systems and cultures, hinder the provision of integrated social care [41], as do privacy concerns regarding information-sharing amongst professionals [30,32,33] and a lack of familiarity with other services or organizations [43]. In particular, conflicts between social workers and child welfare workers has been found to hinder interprofessional collaboration as well as that with parents [32]. In the former, some studies show that professionals regard working in pairs as a facilitator in the provision of integrated social care [41,44]. The involvement of two professionals in one family case (one for the parents and one for the children) can be a facilitator because the focus is often on the parents at the expense of their offspring [44].

Multidisciplinary teams

For both professionals and families, multidisciplinary expertise and the composition of teams [33,36,41] are potentially highly facilitative. militates against blind spots and enhances professional learning [41,43]. Multi-agency partnerships as a specific form of collaboration amongst professionals from different organizations reduce the probability of conflicts, strengthen relationships, and improve outcomes for families [40,41]. However, they require those involved to give up certain privileges that hinder the process and demand that managers address blind spots, which can be difficult [43]. Resistance to (integrated) collaboration and competition among organizations are barriers to integrated social care [30,31].

Coordination of care

A care coordinator is often assigned the formal task of maintaining an overview of the support process and encouraging and coordinating interprofessional collaboration [33]. Three studies note that professionals and family members appreciate care coordination as a facilitator in preventing or resolving conflicts between, for example, social and child welfare services [31,33,41].

In addition, care coordination implies a sense of mastery over the support process by professionals and families experiencing multiple and complex problems [31]. Care coordination is also found to improve interagency collaboration between different organizations, particularly if they share policies, protocols, and training opportunities [31].

Training and supervision

Several of the studies make a plea that professionals remain up to date through training and supervision because there is always the risk that their expertise will not be utilized when working within multidisciplinary teams [32,40,41]. What is more, through training and supervision, professionals can learn to become more resilient and maintain control over situations when they are supporting families.

Professional autonomy

Professional autonomy makes possible the provision of tailor-made guidance to families [31,40,41]. Too much autonomy, however, can make tasks more opaque [41]. While flexibility in the duration and intensity of care [31] is considered a facilitator for integrated social care [40], too much flexibility can lead to burnout [31,33]. High pressure and waiting lists have also been identified as barriers [33,41].

Roles and task structure

Professionals have identified the need for a broad assessment of the support needed by families, a continuous support pathway, and an ongoing evaluation of the support process within the families themselves as important facilitators [41]. Some studies show that clear agreements about tasks, roles, and responsibilities are also facilitative [33,41].

A potential barrier to integrated social care as a broad approach can arise when professionals provide support in areas outside their expertise and when they provide too much support for relatively trivial issues [41]. Professionals may not always have the skills necessary to provide the required support. As a result, they may experience a sense of loss of competence and control [41].

Accessibility of care

For professionals, being able to provide families with access to multiple providers through one organization facilitates integrated social care [43]. For the families themselves, this one point of entry may determine whether they have a positive experience of the process [33,36]. In addition, professionals see working at a co-location as an advantage because it creates a greater sense of familiarity, generates stronger relationships [33,41], and makes it possible to respond more quickly when support is needed [33,36,41].

Barriers to accessibility include a want of strict referral procedures [30,31,39,44]; by contrast, clear ones are facilitative [40,43]. Underdeveloped pathways for intra- and interagency collaborations are another barrier [31].

Discussion

This scoping review aims to identify facilitators and barriers for families receiving integrated social care and for professionals providing such care.

Key elements for families

Our review shows that multiple studies highlight that collaborate relation based on trust between families and professionals, crucial for providing integrated social care [31,32,34,35,37]. Also, others studies suggest that if there is sufficient trust, if information is not withheld and if the family is more involved in the assistance, an uncooperative and/or sceptical attitude of the family can be prevented [45]. Our review also indicates that family members often have a considerable level of distrust towards care services [29,30,31,32]. Reflecting on this issue, it becomes evident that efforts should be directed towards fostering and strengthening trust-based collaborative relationships between families and professionals.

In addition, shared decision making can enhance trust in supporting families [30,31,33]. An other study also reported that involving families in the decision-making process, professionals not only gain valuable insights into the family’s perspective but also empower families [46]. Another study show that shared decision making is an facilitator for family members to take an active role in defining their priorities [1]. As shared decision making enhances coping, problem-solving, and empowerment [45] and problem prioritization, it can be considered integral to integrated social care.

A systematic approach involving all family members should serve as a fundamental pillar in the provision of integrated social care to families [33,35,36,37,38,40,41]. We think that a systemic approach is necessary, but at the same time it is complicated by the current fragmented social care system. Preventing fragmentation by developing policy that prevents this fragmentation of care is therefore needed. This can be done, for example, by not only financing per field, discipline or specialization (monodisciplinary) but by allocating financial resources for multiple disciplines, fields and specializations (multidisciplinary) so that integrated policy can be made. In addition, multi-agency collaboration, where organizations work together to develop integrated social care, is also necessary. More research is needed on these aspects.

Explicitly involving the informal network can be supportive in avoiding fragmentation between those two sources of support [42]. However, one other study shows that the successful involvement of informal networks in formal social care has often limited attention in practice [45]. This underlines the need for a more concerted effort in practice to bridge the gap between formal and informal support network.

In addition, other studies shows that the informal network of these families cannot always contribute positively because these networks are often unstable or because there is a lack of positive parenting norms [47,48]. For this reason, we endorse that a tailor-made assessment must be done for insight in the added value of linking the formal care and the informal network. While, our study indicates the usefulness of informal networks, there is however also a lack of in-depth understanding of this phenomenon, so further research is needed.

Key elements for professionals

For professionals, the wide variety and complexity of problems can make them feel overwhelmed [38]. In line with Lonne and colleagues [46] we argue that resilient professionals are better able to provide qualitative support in often difficult situations of these families [46]. Organizations must therefore ensure that the right conditions exist for strengthening the resilience of these professionals [46]. For delivering support, professionals need clarity about formal agreements on tasks, roles, and responsibilities to avoid overburdening [41]. Also, professional autonomy e.g., in making decisions, the professional needs space to do what is necessary in supporting these families [41]. Care providers face several barriers in their efforts to provide integrated social care. One of these is the fragmentation of services across different sectors and organizations [7,8,9,31]. A lack of collaboration between different service providers can result in gaps, duplications, and inconsistencies in support. Interprofessional collaboration can be a possible solution and strengthen resilience of professionals.

Interprofessional collaboration is an essential part of integrated social care. In this review, we identified several facilitators for interprofessional collaboration, including shared learning [32], multi professional decision-making [29,31], warm handoffs [33,41] and case discussions [41]. These facilitators play a crucial role in enhancing the capabilities of professionals, allowing for the collective deployment of expertise. This positive influence can significantly contribute to fostering successful interprofessional collaboration.

A specific form of interprofessional collaboration is working in pairs, the benefits of which include collaboration and mutual support in the form of feedback, debriefing, continuity of care, and the sharing of knowledge and expertise [41,44]. Working in pairs can be valuable by allowing one professional to concentrate on the children and their needs while the other focuses on the parents with their needs [44]. This division of attention ensures that the child or children receive adequate care and attention within the context of the family dynamic. Although research on this subject is limited, working in pairs could play a significant role in integrated social care for families. We urge future research into working in pairs.

While the goal of integrated care is to improve coordination and collaboration, it can also introduce additional challenges and stressors for professionals [32,41]. Therefore it is important to provide training and supervision opportunities for professionals, establishing robust information-sharing protocols that prioritize family privacy, and actively fostering partnerships with other organizations. Collaborative efforts are needed to cultivate a culture of collaboration and shared responsibility. Because families receive support from multiple professionals, future research should provide in-depth insight into effective elements and mechanisms for interprofessional collaboration with these families of interprofessional collaboration in supporting families is required.

Strengths and limitations

The present study, which is the first scoping literature review of integrated social care, has several limitations. First, integrated social care is a broad and multifaceted concept that lacks a precise definition. Therefore, the studies we have identified may not always explicitly use the term integrated social care. To address this issue, we conducted a thorough search within the selected articles for components related to integrated social care based on the definition underlying the present study. In addition, the concept of families with multiple and complex problems is often operationalized or described differently [11].

Secondly, we report on barriers and facilitators that apply not only to integrated social care but also to the provision of integrated care in general, for instance, strengthening collaborative relationships, asking for feedback, the use of humour, and home visits. These facilitators and barriers are fundamental to the principles of integrated social care and are inherently part of it. Therefore, we did not differentiate these general facilitators from the more specific ones for integrated social care. Also, the studies were of a high quality, thereby ensuring the reliability of the evidence (Appendix 2).

Conclusion

We found the key elements of integrated social care to be a systemic approach based on trust; shared decision-making; social networks; and coordinated care. Shared decision-making helps to establish a systemic approach and empowers all family members (including the children). This allows them maximum control over the support process and respect for their autonomy, If a family does not have a supportive informal network, this can give its members more agency. Finally, care coordination can help to prevent fragmentation, especially when its implementation involves a care plan. Families often face multiple and complex problems and interact with various professionals, it is crucial that there be integrated collaboration between the families and these professionals within social care.

Additional Files

The additional files for this article can be found as follows:

Search overview databases.

Methodological appraisal of the studies: qualitative.

Reviewers

Cam Donaldson PhD FRSE, Yunus Chair & Distinguished Professor of Health Economics, Yunus Centre for Social Business & Health, Glasgow Caledonian University, UK.

One anonymous reviewer.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- 1.Nooteboom LA, Mulder EA, Kuiper CHZ, Colins OF, Vermeiren RRJM. Towards integrated youth care: a systematic review of facilitators and barriers for professionals. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2021; 48(1): 88–105. DOI: 10.1007/s10488-020-01049-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sousa L, Ribeiro C, Rodrigues S. Are practitioners incorporating a strengths-focused approach when working with multi-problem poor families? Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 2007. Jan; 17(1): 53–66. DOI: 10.1002/casp.875 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knot-Dickscheit J, Knorth EJ. Gezinnen met meervoudige en complexe problemen: Theorie en praktijk. [Families with multiple and complex problems: theory and practice]. Rotterdam, the Netherlands: Lemniscaat; 2019. [in Dutch]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verwey Jonker Instituut. Typologie voor een strategische aanpak van multiprobleemgezinnen in Rotterdam. [Typology for a strategic approach to multi-problem families in Rotterdam.]. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Verwey Jonker Instituut; 2010. [in Dutch]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghesquière P. Multi probleem gezinnen: problematische hulpverleningssituaties in perspective. [Multi-problem families: problematic assistance situations in perspective]. Louvain, Belgium: Garant; 1993. [in Dutch]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nooteboom L, Mulder E, Kuiper C, Vermeiren R. Integraal werken? Focus op de uitvoerende hulpverleners: Complexiteit van uitvoering te vaak over het hoofd gezien. [Integral work? Focus on the executive aid workers: complexity of implementation too often overlooked. Kind & Adolescent Praktijk]. 2021; 20: 24–30. [in Dutch]. DOI: 10.1007/s12454-021-0650-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tausendfreund T. Coaching families with multiple problems: care activities and outcomes of the flexible family support programme Ten for the Future. Groningen, the Netherlands: University of Groningen; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleek EN, Wofsy M, Boyd-Franklin N, Mundy B, Howell TJ. The Family Empowerment Program: an interdisciplinary approach to working with multi-stressed urban families. Family Process. 2012; 51(2): 207–217. DOI: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01392.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sousa R. The collaborative professional: towards empowering vulnerable families. Journal of Social Work Practice. 2012; 26(4): 411–425. DOI: 10.1080/02650533.2012.668878 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tausendfreund T, Knot-Dickscheit J, Schulze GC, Knorth EJ, Grietens H. Families in multi-problem situations: backgrounds, characteristics, and care services. Child and Youth Services. 2016; 37(1): 4–22. DOI: 10.1080/0145935X.2015.1052133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly LM, Knowles JM. The integrated care team: a practice model in child and family services. Journal of Family Social Work. 2015; 18(5): 382–395. DOI: 10.1080/10522158.2015.1101728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goerge W. Understanding vulnerable families in multiple service systems. Understanding vulnerable families. The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences. 2019; 5(2): 86–104. DOI: 10.7758/rsf.2019.5.2.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sacco FC, Twemlow SW, Fonagy P. Secure attachment to family and community. Smith College Studies in Social Work. 2008; 77(4): 31–51. DOI: 10.1300/J497v77n04_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization (WHO). Integrated care models: an overview. Working document. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2016. (PDF) Integrated care models: an overview. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2016. (researchgate.net) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruce D, Parry B. Integrated care: a Scottish perspective. International Journal of Primary Care. 2016; 7(3): 44–48. DOI: 10.1080/17571472.2015.11494376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evers S, Paulus ATG. Health economics and integrated care: a growing and challenging relationship. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2015; 15. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.2201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis M. Integrated care in Wales: a summary position. London Journal of Primary Care. 2016; 7(3): 49–54. DOI: 10.1080/17571472.2015.11494377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spicer J. Integrated care in the UK: variations on a theme? London Journal of Primary Care. 2016; 7(3): 41–43. DOI: 10.1080/17571472.2015.11494375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozlowska O, Lumb A, Tan GD, Rea R. Barriers and facilitators to integrating primary and specialist healthcare in the United Kingdom: a narrative literature review. Future healthcare journal. 2018. Feb; 5(1): 64. DOI: 10.7861/futurehosp.5-1-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eastwood J, Barmaky S, Hansen S, Millere E, Ratcliff S, Fotheringham P, et al. Refining program theory for a place-based integrated care initiative in Sydney, Australia. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2020; 20: 13. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.5422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018; 169(7): 467. DOI: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2014; 67(12): 1291–1294. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005; 8(1): 19–32. DOI: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science. 2010; 5: 69. DOI: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.da Costa Santos CM, de Mattos Pimenta CA, Nobre MR. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2007; 15: 508–11. 11. Minayo MCS, Souza. DOI: 10.1590/S0104-11692007000300023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2016; 5: 1. DOI: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Treloar C, Champness S, Simpson PL, Higginbotham N. Critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research studies. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2000; 67(5): 347–351. DOI: 10.1007/BF02820685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butcher NJ, Monsour A, Mew EJ, Chan AW, Moher D, Mayo-Wilson E, Terwee CB, Chee-A-Tow A, Baba A, Gavin F, Grimshaw JM, Kelly LE, Saeed L, Thabane L, Askie L, Smith M, Farid-Kapadia M, Williamson PR, Szatmari P, Tugwell P, Golub RM, Monga S, Vohra S, Marlin S, Ungar WJ, Offringa M. Guidelines for Reporting Outcomes in Trial Reports: The CONSORT-Outcomes 2022 Extension. JAMA. 2022; 328(22): 2252–2264. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2022.21022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serbati S, Ius M, Milani P. PIPPI Programme of Intervention for Prevention of Institutionalization. Capturing the evidence of an innovative programme of family support. Revista de cercetare si interventie sociala. 2016; 52. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eastwood J, Barmaky S, Hansen S, Millere E, Ratcliff S, Fotheringham P, et al. Refining program theory for a place-based integrated care initiative in Sydney, Australia. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2020; 20: 13. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.5422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eastwood JG, Dewhurst S, Hansen S, Tennant E, Miller E, Moensted ML, et al. Care coordination for vulnerable families in the Sydney local health district: what works for whom, under what circumstances, and why? International Journal of Integrated Care. 2020; 20: 22. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.5437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tennant E, Miller E, Costantino K, De Souza D, Coupland H, Fotheringham P, et al. A critical realist evaluation of an integrated care project for vulnerable families in Sydney, Australia. BMC Health Services Research. 2020; 995. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-020-05818-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nooteboom LA, Kuiper CHZ, Mulder EA, Roetman PJ, Eilander J, Vermeiren RRJM. What do parents expect in the 21st century? A qualitative analysis of integrated youth care. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2020; 20(3): 1–13. DOI: 10.1186/s13034-020-00321-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris K. Troubled families: vulnerable families’ experiences of multiple service use. Child Family Social Work. 2013; 18(2): 198–206. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2011.00822.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bachler E, Frühmann A, Bachler H, Aas B, Strunk G, Nickel M. Differential effects of the working alliance in family therapeutic home-based treatment of multi-problem families. Journal of Family Therapy. 2016; 38(1): 120–148. DOI: 10.1111/1467-6427.12063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Onyskiw JE, Harrison MJ, Spady D, McConnan L. Formative evaluation of a collaborative community-based child abuse prevention project. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999; 23(11): 1069–1081. DOI: 10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00080-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sousa L. Building on personal networks when intervening with multi- problem poor families. Journal of Social Work Practice. 2005; 19(2): 163–179. DOI: 10.1080/02650530500144766 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Lawick J, Bom H. Building bridges: home visits to multi-stressed families where professional help reached a deadlock. Journal of Family Therapy. 2008; 30(4): 504–516. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-6427.2008.00435.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bachler E, Fruehmann A, Bachler H, Aas B, Nickel M, Schiepek GK. Patterns of change in collaboration are associated with baseline characteristics and predict outcome and dropout rates in treatment of multi-problem families. A validation study. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017; 8. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thoburn J, Cooper N, Brandon M, Connolly S. The place of “think family“ approaches in child and family social work: messages from a process evaluation of an English pathfinder service. Children and Youth Services Review. 2013; 35(2): 228–236. DOI: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.11.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nooteboom LA, van den Driesschen SI, Kuiper CHZ, Vermeiren RRJM, Mulder EA. An integrated approach to meet the needs of high-vulnerable families: a qualitative study on integrated care from a professional perspective. Child Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2020; 14(18). DOI: 10.1186/s13034-020-00321-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sousa L, Rodrigues S. Linking formal and informal support in multiproblem low-income families: the role of the family manager. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009; 37(5): 649–662. DOI: 10.1002/jcop.20313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nadeau L, Jaimes A, Rousseau C, Papazian-Zohrabian G, Germain K, Broadhurst J, Battaglini A, Measham T. Partnership at the forefront of change: documenting the transformation of child and youth mental health services in Quebec. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012; 21(2): 91–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tausendfreund T, Knot-Dickscheit J, Post WJ, Knorth EJ, Grietens H. Outcomes of a coaching program for families with multiple problems in the Netherlands: a prospective study. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014; 46: 203–212. DOI: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.08.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stabler L, O’Donnell C, Forrester D, Diaz C, Willis S, Brand S. Shared decision-making: What is good practice in delivering meetings? Involving families meaningfully in decision-making to keep children safely at home: A rapid realist review. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lonne B, Higgins D, Herrenkohl TI, Scott D. Reconstructing the workforce within public health protective systems: Improving resilience, retention, service responsiveness and outcomes. Child abuse & Neglect. 2020; 110: 104191. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bodden DHM, Deković M. Multiproblem Families Referred to Youth Mental Health: What’s in a Name? Family process. 2016; 55(1): 31–47. DOI: 10.1111/famp.12144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fernandez E. Supporting children and responding to their families: Capturing the evidence on family support. Children and youth services review. 2007; 29(10): 1368–1394. DOI: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.05.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search overview databases.

Methodological appraisal of the studies: qualitative.