Abstract

RmInt1 is a group II intron of Sinorhizobium meliloti which was initially found within the insertion sequence ISRm2011-2. Although the RmInt1 intron-encoded protein lacks a recognizable endonuclease domain, it is able to mediate insertion of RmInt1 at an intron-specific location in intronless ISRm2011-2 recipient DNA, a phenomenon termed homing. Here we have characterized three additional insertion sites of RmInt1 in the genome of S.meliloti. Two of these sites are within IS elements closely related to ISRm2011-2, which appear to form a characteristic group within the IS630-Tc1 family. The third site is in the oxi1 gene, which encodes a putative oxide reductase. The newly identified integration sites contain conserved intron-binding site (IBS1 and IBS2) and δ′ sequences (14 bp). The RNA of the intron-containing oxi1 gene is able to splice and the oxi1 site is a DNA target for RmInt1 transposition in vivo. Ectopic transposition of RmInt1 into the oxi1 gene occurs at 20-fold lower efficiency than into the homing site (ISRm2011-2) and is independent of the major RecA recombination pathway. The possibility that transposition of RmInt1 to the oxi1 site occurs by reverse splicing into DNA is discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Group II introns are a unique class of introns initially found in organellar genes of lower eukaryotes and plants but recently also found in bacteria (1). These introns are large catalytic RNAs which splice via a lariat intermediate, similar to the mechanism of spliceosomal introns (1). Some group II introns are mobile genetic elements that insert site specifically at intron-specific locations in intronless alleles, a process known as homing. In addition to homing, some introns are able to transpose to novel (ectopic) sites at low frequency (2–4).

Recent studies with the Lactoccocus lactis Ll.ltrB intron and the yeast mitochondrial aI1 and aI2 introns have established a mechanism for group II intron retrohoming (5–7). Mobility occurs by a target DNA-primed reverse transcription mechanism involving intron-encoded reverse transcriptase (RT) and a site-specific DNA endonuclease (5–10). The endonuclease is a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex containing both the intron RNA and the intron-encoded protein (IEP). The intron RNA cleaves the sense DNA strand by a partial or complete reverse splicing reaction at the intron insertion site, while the IEP cleaves the antisense strand after the +10 position of the 3′ exon, or +9 in the case of the Ll.ltrB intron. The 3′-end of the cleavage site is then used as the primer for reverse transcription of either the unspliced RNA precursor or the intron RNA that had reverse spliced into the sense strand of the recipient DNA. Group II intron endonucleases use both their RNA and protein components to recognize specific sequences in their DNA target sites. In the case of the Ll.ltrB intron the RNP recognition site spans from –25 to +10, while intron RNA base pairs over positions –13 to +1 (5). Retrohoming of the Ll.ltrB intron occurs via complete reverse splicing of the intron RNA into DNA, independent of homologous recombination (5).

In contrast to retrohoming, the mechanism(s) of ectopic transposition is still poorly understood and different pathways have been proposed (2–4). Recently, data obtained with the L1.ltrB intron suggest that the major retrotransposition pathway can proceed by reverse splicing of the intron into an ectopic site in RNA followed by reverse transcription and homologous recombination of the resulting cDNA. This retrotransposition occurs in an endonuclease-independent and recombinase-dependent fashion (11). On the other hand, for yeast intron aI1 in vitro data show that it reverse splices directly into ectopic DNA transposition sites (6).

RmInt1 is a group II intron from Sinorhizobium meliloti, the IEP of which lacks a recognizable endonuclease domain (12,13). Nevertheless, this intron has been shown to be mobile (13). Although the homing pathway of this intron has yet to be determined, the fact that the IEP lacks a HNH motif suggests that its mobility may involve a different mechanism. RmInt1 is abundant and widespread within S.meliloti native populations, where it appears located mostly within the insertion sequence ISRm2011-2. Nevertheless, some S.meliloti strains harbor copies of RmInt1 at different locations. From sequence analysis data it was previously suggested that one of these heterologous sites was another IS element closely related to ISRm2011-2 (12).

In the present study we have characterized three additional insertion sites of RmInt1 in the genome of S.meliloti. We show that RmInt1 is able to splice at the most divergent of these locations (the oxi1 gene) and that it transposes in vivo to this ectopic site independently of homologous recombination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media and growth conditions

Escherichia coli was routinely grown at 37°C on Luria–Bertani medium (14) and rhizobial strains at 28°C on TY (15) or defined minimal medium (16). Antibiotics were used as required at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 200 µg/ml; kanamycin, 180 µg/ml for S.meliloti and 50 µg/ml for E.coli. Sinorhizobium meliloti strains used were GR4 and RMO17 (this laboratory), GR4 RecA– (13), 2011 (Nod+, Fix+ SU47 derivative strain; J. Denarié), CE31A and LPU119 (17)

DNA sequencing and analysis

Sequencing was performed with an Automatic Laser Fluorescent DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems). DNA sequence edition, translation and analysis were performed with the GeneWorks software package (Oxford Molecular Group). The program FASTA and the BLAST Network Server at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) were utilized for homology searching.

DNA hybridization and fingerprinting

Total DNA was isolated according to standard protocols (14). After restriction enzyme digestion, 2 µg of DNA was electrophoretically separated in a 0.8% Tris–borate agarose gel and vacuum blotted onto nylon filters (Hybond-N; Amersham) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA probes for ISRm2011-2 and RmInt1 were obtained by PCR amplification of internal fragments, in the presence of digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim), using plasmid pRmNT40 (18) as template. Oligonucleotides used in the amplification reaction were: ISRm2011-2 5′ exon, ORFAII 5′ (5′-GAATGATCTTCGGGAACGCG-3′) and ORFAII 3′ (5′-CTCAACCCCTCTTCGTGCA-3′); ISRm2011-2 3′ exon, 2011B1 (5′-TGGACGAAGACGAACATGG-3′) and 2011B2 (5′-TTGAAGTAGGCTGCGCATT-3′); RmInt1 5′-end, Epsilon (5′-GTGAGCGTCGGATGAAAC-3′) and 18R0 (5′-ACGTTTCTCAATTCGAAACG-3′); RmInt1 3′-end, Int1 (5′-GTATCCGAATGTCACGTTCG-3′) and Int2 (5′-CCGTCCATAGTAGGCAATCC-3′). DNA probes for ISRm10-1(5′ exon), ISRm10-2(3′ exon) and oxi1(5′ exon) spanning positions 1–816, 687–969 and 49–422, respectively, were synthesized by PCR. Probes were further purified on S300HR Sephadex columns (Pharmacia). Hybridization was carried out under high stringency conditions according to the supplier’s instructions. Washing of the membranes and detection of the hybridization signals were performed as specified by Boehringer Mannheim.

Isolation and DNA sequence analysis of RmInt1 insertion sites

The 5′ and 3′ exon junctions of insertion sites additional to that of ISRm2011-2 for intron RmInt1 in the genome of S.meliloti strains 2011, CE31A and LPU119 were identified by DNA hybridization using RmInt1 and ISRm2011-2 specific probes. The corresponding DNA was amplified by inverse PCR using divergently annealing primers (see below) to identify exon sequences (12) and by PCR using intron internal primers 6 and 7 to characterize the inserted RmInt1 copy. Direct sequencing of amplified reaction products was performed as described above. Primers 1 and 2 were used to amplify the 5′ exon junction of ISRm10-2 (CE31A strain) and oxi1 (LPU119 strain) using as templates EcoRI fragments of 1.65 and 1.55 kb, respectively. Primers 3 and 4 were used to amplify the 3′ exon junction of ISRm10-1 (2011 strain) and ISRm10-2 using as templates EcoRI fragments of 1.4 and 2.1 kb, respectively. Finally, primers 4 and 5 were used to amplify the 3′ exon junction of oxi1 using a 3.0 kb SacI fragment as template. Primers: 1, positions 21–40 in RmInt1 – strand; 2, positions 661–680 in RmInt1 + strand; 3, positions 981–1000 in RmInt1 – strand; 4, positions 1861–1880 in RmInt1 + strand; 5, positions 230–247 in oxi1 – strand; 6, positions 147–164 in RmInt1 + strand; 7, positions 575–594 in RmInt1 – strand.

Splicing analysis

Total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis were carried out as previously described (12), using ORB (positions 528–546 in the oxi1 – strand) as the RNA annealing primer. PCR reactions were carried out in a Robocycler 40 (Stratagene) using primers ORA (positions 49–64 in the oxi1 + strand) and ORB. The cycling conditions were 3 min initial denaturation at 94°C, followed by 35–40 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min and 72°C for 2.5 min, with an extension of 15 min at 72°C. PCR samples (8 µl) were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The RT–PCR product of 0.5 kb was isolated, purified from the agarose gel and sequenced using primers ORA and ORB.

In vivo analysis of transposition to the oxi1 gene

The region encompassing –415 to +98 of the oxi1 gene insertion site was amplified and subcloned into pGEM-T (Promega), resulting in plasmid pTOR. Plasmid pTOR was then digested with ApaI and SalI and the oxi1-derived fragment was cloned into plasmid pBBCRMS-2 (19), to generate plasmid pBBTOR. Plasmid pBB0.6+, containing a 640 bp fragment encompassing the intron insertion site of ISRm2011-2, and the derivative pBBΔ129, carrying an internal deletion of the target site, were used as controls for homing (13). Plasmids were transferred from E.coli cells to Sinorhizobium by triparental mating using the helper plasmid pRK2013 (20). Plasmid isolation from S.meliloti was from cells grown in TY medium until stationary phase. The DNA was digested with SalI and Southern hybridization with the 5′-end RmInt1 probe was performed at high stringency. Detection of pBBTOR+Intron (pBB2.4) required overexposure of the film, which resulted in non-specific hybridization signals from the intron recipient plasmid (T form, Fig. 4B, bottom, lanes 2–5). The heavy hybridization signals observed at the bottom of Figure 4B (lanes 1 and 6) correlate with the level of intron-invaded plasmids and are due to undigested supercoiled forms. Densitometric scanning of the bands of ethidium bromide stained gels was carried out with an Imagequant AQ system (Applied Biosystems), which revealed that equivalent amounts of recipient plasmid DNA were loaded in each lane (Fig. 4A). The percentage of invasion of recipient plasmids containing the homing target site (pBB0.6+, Fig. 4A, lanes 1 and 6) was calculated from the ethidium bromide stained gel data, corrected by taking into account the differences in size between the two plasmids analyzed (intron-invaded and recipient). However, the percentage of invasion of plasmid containing the oxi1 target (pBBTOR, Fig. 4, lanes 2 and 4) could only be estimated by comparing the specific hybridization signal intensities displayed by the RmInt1-invaded plasmid forms.

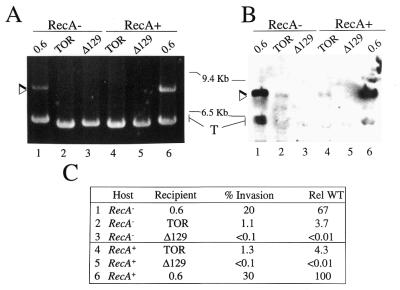

Figure 4.

RecA-independent transposition of RmInt1 into the oxi1 gene. (A) Plasmid pool analysis from GR4 (lanes 4–6) and its recA– derivative (lanes 1–3) were performed as specified (see Materials and Methods). Lanes 1 and 6, pBB0.6+ pool; lanes 2 and 4, pBBTOR pool; lanes 3 and 5, pBBΔ129 pool. (B) DNA hybridization blot performed with the intron-specific probe. Arrowheads indicate the novel plasmids that migrate 1.8 kb above the cognate target pBB0.6+ and pBBTOR plasmids. Molecular markers are indicated. T, recipient plasmid. (C) Levels of invasion of the respective recipient plasmids at the indicated host. The percentage intron invasion was determined as indicated (see Materials and Methods). Rel WT indicates relative to 100 for the pBB0.6+ recipient in a RecA+ host. The data is the mean of two independent experiments.

RESULTS

The insertion sites for intron RmInt1 in the genome of S.meliloti

Even though in S.meliloti intron RmInt1 is mostly located in ISRm2011-2, some strains carry copies of the intron at a different location. We investigated these additional insertion sites in strains 2011, CE31A and LPU119 (see Materials and Methods).

Consistent with our previous findings (12), DNA and amino acid sequence analyses of the 3′ exon showed that the additional insertion site in strain 2011 is an IS element, hereafter referred to as ISRm10-1. Similarly, in strain CE31A the additional insertion site is another IS element, hereafter named ISRm10-2. Interestingly, in strain LPU119 the insertion site appears to be a gene coding for a putative oxide reductase (hereafter referred to as oxi1; Table 1), which shows similarity (39% identity) with DltE protein of Bacillus subtilis (21). The intron integration site in oxi1 is located close to the end of the coding region. DNA hybridization studies indicated that ISRm10-1 and ISRm10-2 are less abundant than ISRm2011-2 in S.meliloti (Table 1). In addition, it was found that oxi1 is present as a single copy in the genome of S.meliloti, where it mostly appears as an oxi1 intronless gene (Table 1; N.Toro, unpublished data). All the insertion sites identified are in the sense orientation of the respective genes.

Table 1. Presence of RmInt1 and host elements in the genome of S.meliloti.

| Strain | Host element | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISRm2011-2a | ISRm10-1a | ISRm10-2a | oxi1a | |

| GR4 | 12/9 | 2/1 | 0/0 | 1/0 |

| 2011 | 12/2 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 1/0 |

| CE31A | 4/2 | 1/0 | 1/1 | 1/0 |

| LPU119 | 5/4 | 2/1 | 0/0 | 1/1 |

aTotal copy number of the host element/number of copies of the host element invaded by RmInt1.

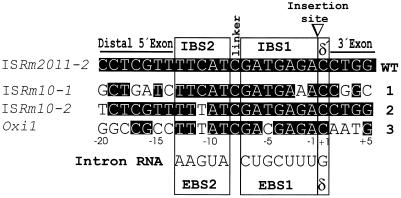

The intron copies in the above insertion sites were partially sequenced (from 165 to 584 bp, including the EBS1 and EBS2 motifs) and each was shown to have an identical DNA sequence to that of the intron found within ISRm2011-2 in pRmNT40 (12). Furthermore, the intron inserts between the same A and C nucleotides (Fig. 1). Identification of these new intron insertion sites enabled us to propose the sequence UUUCGUC (nt 256–263) as the EBS1 sequence of intron RmInt1, instead of the sequence previously suggested (12).

Figure 1.

Insertion sites for intron RmInt1 in the genome of S.meliloti. DNA alignment of the insertion sites encompassing the –20/+5 positions from the wild-type (WT) and additional characterized sites (1–3) are shown. The intron insertion site is indicated with a triangle, dividing the gene into two exons, 5′ and 3′. Potential base pairing interactions (EBS1/IBS1, EBS2/IBS2 and δ/δ′) of the intron RNA RmInt1 with its target DNA sequence, including the linker, are indicated. White nucleotides on a black background represent identity with the wild-type. ISRm2011-2, ISRm10-1, ISRm10-2, oxi1 and RmInt1 intron sequences are deposited in the EMBL data bank with accession nos U22370, AJ242573, AJ242574, AJ242575 and Y11597, respectively.

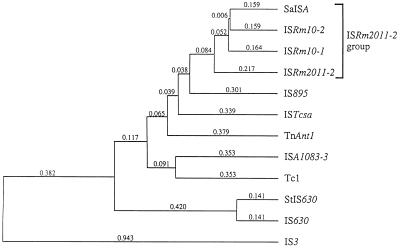

The three ISs harboring RmInt1 in S.meliloti are closely related and, together with an IS found in Sphingomonas aromaticivorans (22), appear to constitute a particular group within the IS630-Tc1 family (12,23), hereafter referred to as the ISRm2011-2 group (Fig. 2). Proteins encoded by ISRm10-1, ISRm10-2 and the IS found in S.aromaticivorans (SaISA) show 45, 43 and 42% amino acid identity, respectively, with ISRm2011-2 ORF AB. The ISs have a similar size (1042 bp for ISRm10-1, 1049 bp for ISRm10-2, 1053 bp for ISRm2011-2 and 1056 bp for SaISA) and identical terminal direct repeats (TA) and encode two ORFs (A and B) with a potential translational frameshifting site (AAAAAAAG) at a similar distance upstream of the intron insertion site (109 nt for ISRm2011-2, 108 nt for ISRm10-1 and 109 nt for ISRm10-2). The ISRm2011-2 group, in addition to the characteristic ‘DE, D35E’ motif (23) has the conserved motif FIDET encompassing the dipeptide Asp–Glu (DE), which results from translation of the IBS2, IBS1 and δ′ sequences (Fig. 1). The oxi1 gene also contains the IBS1, IBS2 and δ′ sequences and its encoded product contains in its C-terminal region the FIDET motif.

Figure 2.

UPGMA (unweighted pair group method using arithmetic averages) tree of the predicted transposases from some representative members of the IS630-Tc1 family and the ISs harboring RmInt1. The amino acid sequences of the transposases were aligned by the Clustal method using the Geneworks software package (Oxford Molecular Group). The distance scale represents the percentage divergence. ISRm10-1, ISRm10-2, ISRm2011-2 and SaISA form the ISRm2011-2 group (bracket). IS630 from Shigella sonnei (X05955), StIS630 from Salmonella typhimurium (M58505), ISA1083-3 from Archaeglobus fulgidus (AE000956), IS895 from Anabaena (U96137), TnAnt1 from Aspergillus niger (S80872), ISTcsa from Synechocystis (D90911), ISRm2011-2 from S.meliloti (U22370), SaISA from S.aromaticivorans (AF079317) and Tc1 (X01005) from Caenorhabditis elegans. A representative member of the related IS3 family is also included (X02311).

The DNA target site for intron RmInt1

A deletion analysis of the wild-type DNA target site (ISRm2011-2) defined a minimal region of 25 bp (20 bp of homology in the 5′ exon and 5 bp of homology in the 3′ exon) that supports homing to wild-type levels (F.M.García-Rodríguez and N.Toro, unpublished results). Hence, the DNA target sites compared in Figure 1 encompass only 25 bp (5′ exon –20 to 3′ exon +5). Within the IBS (positions –1 to –13) and δ′ (position +1) sequences, which base pair with complementary intron RNA EBS and δ sequences, only positions –2, –5 and –11 show nucleotide changes that represent transitions that can still allow Watson–Crick pairings with the internal guide sequences of the intron (Fig. 1). Beyond the IBS and δ′ sequences the conservation decreases. This is particularly relevant for the oxi1 insertion site, where only residues at positions –16G, –17C and +5G are maintained with respect to the wild-type (ISRm2011-2).

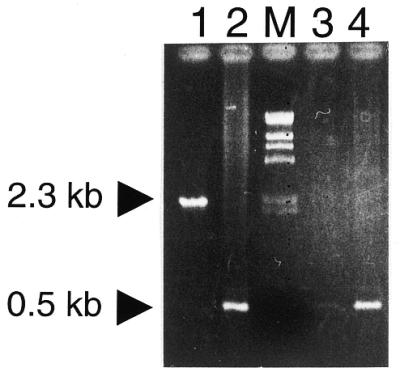

Forward splicing of RmInt1 at the oxi1 insertion site

RmInt1 splices at the ISRm2011-2 wild-type insertion site (12,24). We investigated whether RmInt1 is also competent for splicing at the oxi1 site. RNA from S.meliloti strain LPU119 was reverse transcribed and amplified by PCR with primers specific for both exons of oxi1. The 0.5 kb RT–PCR product obtained (Fig. 3, lanes 3 and 4) was ∼1.8 kb smaller than the product amplified by PCR from LPU119 total DNA (lane 1). Furthermore, it was the same size as the PCR product obtained using total DNA of strain GR4, which carries an oxi1 intronless gene (lane 2). Sequence analysis of the 0.5 kb RT–PCR fragment from LPU119 RNA revealed the joined exons of oxi1. Although the splicing efficiency needs to be estimated, we conclude that intron RmInt1 is able to splice at the oxi1 insertion site.

Figure 3.

Splicing of RmInt1 at the oxi1 site. Electrophoretic analysis of PCR products obtained using 10 ng total DNA from LPU119 (lane 1) or GR4 (lane 2) or LPU119 cDNA (lanes 3 and 4). PCR amplification was carried out for 35 (lane 3) and 40 (lanes 1, 2 and 4) cycles using the ORA (positions 49–64 in the oxi1 + strand) and ORB (positions 528–546 in the oxi1 – strand) primers annealing to both exons. Arrows indicate the PCR products derived from DNA of the oxi1 gene invaded by RmInt1 (2.3 kb) and from mRNA of the ligated exons (0.5 kb) or native oxi1 gene (not invaded by RmInt1).

RmInt1 transposition to the ectopic oxi1 site in vivo is RecA-independent

To test if the RmInt1 intron is able to invade the intronless oxi1 gene in vivo (Fig. 4), plasmid pBBTOR carrying the oxi1 insertion site was transferred to S.meliloti strain GR4 (harboring an intronless oxi1 gene; Table 1) and to its recA– derivative (13). Intron invasion of pBBTOR was compared with that of pBB0.6+ carrying the wild-type insertion site of ISRm2011-2 (13). Plasmid pool analysis and DNA hybridization indicated that intron invasion occurred in all transconjugants analyzed (two independent experiments; data not shown) but not in those where the target (pBBΔ129) lacks the insertion site (Fig. 4, lanes 3 and 5; 13). DNA sequence analysis of invaded pBBTOR in strain GR4 shows that intron insertion occurs at the exon junction and that the flanking regions are identical to those of the wild-type oxi1 intronless gene. Moreover, the DNA sequence of the intron inserted into pBBTOR was identical to the sequence already published for intron RmInt1 (12; data not shown). These results indicate that the transposition of RmInt1 to the oxi1 gene is a site-specific event, like homing (13). To test if the ectopic transposition of RmInt1 follows a RecA-dependent pathway as described for L1.LtrB (11), transposition assays were carried out in parallel with a GR4 recA– derivative strain (Fig. 4, lanes 1–3). In both recA+ and recA– hosts the oxi1 target site was invaded by the intron with similar efficiencies of 1.3 and 1.1%, respectively (Fig. 4C), which represents a 20-fold lower efficiency compared with that of the homing site (ISRm2011-2). This result indicates that ectopic transposition of RmInt1 to the oxi1 gene is independent of homologous recombination and suggests that it may involve a DNA rather than an RNA target.

DISCUSSION

Here, we report on group II intron RmInt1 natural insertion sites and transposition events in S.meliloti. We have characterized three additional insertion sites, two of them corresponding to IS elements closely related to ISRm2011-2, while the third shows similarity to genes of the family of oxide reductases.

Most of the bacterial group II introns identified to date have been localized within genes likely to be involved in DNA mobility (25–30). However, the association of RmInt1 with a specific group of IS elements is remarkable and unprecedented for bacterial group II introns. The target site within these IS elements and the flanking regions are conserved, exhibiting a high similarity between the corresponding encoded ORFs and inverted repeats. Interestingly, in addition to the DE and D35E motifs characteristic of the IS630-Tc1 family (23), the host IS elements for intron RmInt1 contain in the ORF B portion of the transposase the motif FIDET, which results from translation of the IBS1, IBS2 and δ′ sequences (Fig. 1). All these features suggest that they form a subgroup within the IS630-Tc1 family (Fig. 2). Recently, an IS element of this group (ISRm2011-2) has been reported in plasmid pNL1 of S.aromaticivorans (22). However, it is not known whether this bacterial species contains more copies of this element and if any of them is interrupted by an RmInt1 homolog. ISRm2011-2 is considered an ancestral IS element of S.meliloti (31), but similar mobile elements have been detected in the closely related species Sinorhizobium medicae, where each appears as a single copy and is free of introns (E.Muñoz and N.Toro, unpublished results). On the other hand, a group II intron similar to RmInt1 (>95% nt identity) has been identified in other Sinorhizobium species within a putative mobile element of the ISRm2011-2 group (E.Muñoz and N.Toro, unpublished results). Thus it is likely that the presence of specific DNA target sites provided by the abundance of these IS elements, particularly of ISRm2011-2, in S.meliloti has facilitated the successful spread of the intron in these bacterial species.

In addition to the former ISRm2011-2 group of IS elements, RmInt1 was found in a gene, oxi1, which codes for a putative oxide reductase that is not related to genes involved in DNA mobility. This ectopic site contains the IBS1, IBS2 and δ′ sequences (Fig. 1) recognized by the intron RNA, which allows sufficient base pairings with intron sequences for forward splicing (Fig. 3). Hence, it is unlikely that insertion of the intron into the oxi1 gene would interfere with the putative function of this locus. Although the oxi1 gene encoded product does not show similarity to the transposases of the ISRm2011-2 group, it does carry the FIDET motif as a consequence of possession of the IBS1, IBS2 and δ′ sequences. Whether this particular translated frame has any meaning in either splicing or intron invasion remains to be elucidated.

All the insertions found for intron RmInt1 in the genome of S.meliloti are in the sense orientation of the respective transposase and oxi1 genes. Similarly, the ectopic insertions described for intron Ll.ltrB were in the sense orientation of the gene (11), which was taken to support the hypothesis of retrotransposition into an RNA target. Although it is questionable whether insertions of RmInt1 into the closely related IS elements qualify as transpositions, insertion into oxi1 in strain GR4 can certainly be considered a transposition event. Group II intron endonucleases use both their RNA and protein components to recognize specific sequences in their DNA target sites (32). In L1.ltrB retrohoming protein recognition of the DNA target site is required at G–21 for reverse splicing and at T+5 for antisense strand cleavage (33). In vivo changes to the complementary nucleotide at positions –21 and +5 resulted in homing levels <5% of wild-type. The DNA target site for intron RmInt1 is shorter than that of the lactoccocal intron (33) and extends from position –20 in the 5′ exon to +5 in the 3′ exon (F.M.García-Rodríguez and N.Toro, unpublished results). In addition to the IBS–EBS and δ′–δ interactions, the DNA sequence comparison between oxi1 and ISRm2011-2 (wild-type homing site) revealed conserved residues in the distal 5′ exon region (positions –16 and –17) and 3′ exon (position +5). Since we found that the oxi1 site is a DNA target for RmInt1 transposition in vivo, it would appear that this ectopic site conserves critical residues enabling intron RNA recognition, as well as the RmInt1 IEP interaction. Following the model proposed for yeast and lactoccocal introns, the finding that the level of invasion of oxi1 is <5% of wild-type would suggest that other non-conserved residues in the 5′ distal exon (i.e. –14, –15, –18 and/or –20) and 3′ exon (i.e. +2, +3 and/or +4) in oxi1 are required for protein recognition. In addition, the change at position –11 of a C to a T residue in IBS2 decreases the homing level (F.M.García-Rodríguez, J.I.Jiménez-Zurdo and N.Toro, unpublished data), which would be consistent with the lower level of invasion of oxi1.

In contrast to the major pathway of L1.ltrB ectopic mobility that proceeds in an endonuclease-independent and recombinase-dependent fashion (11), RmInt1 ectopic transposition, at least into the oxi1 site, is RecA-independent, as is invasion of wild-type ISRm2011-2, which suggests a DNA rather than an RNA target. The L1.ltrB ectopic transposition sites reported lack the apparent protein recognition sites, particularly at T+5 in exon II (11), which is required for antisense strand cleavage. Interestingly, the RmInt1 IEP lacks the endonuclease domain (13) involved in antisense DNA strand cleavage in other mobile group II introns and it is still not known whether this IEP carries another endonuclease domain or whether the putative antisense strand cleavage is mediated by a host protein. The more plausible explanation for our results is that transposition into the ectopic oxi1 site proceeds by reverse splicing of intron RNA directly into double-stranded DNA followed by reverse transcription of the inserted intron RNA. However, we cannot rule out that the former pathway could be restricted to a small number of cases in which the ectopic site coincidentally resembles the wild-type homing site. Further work will be required to elucidate this question.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr José Ignacio Jiménez-Zurdo and Pieter van Dillewijn for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grant BIO99-0905 from the Comisión Asesora de Investigación Científica y Técnica and by grant BIO4-CT98-0483 from the Biotechnology Programme of the EU.

REFERENCES

- 1.Michel F. and Ferat,J.L. (1995) Annu. Rev. Biochem., 64, 435–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mueller M.W., Allmaier,M., Eskes,R. and Schweyen,R.J. (1993) Nature, 366, 174–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt W.M., Schweyen,R.J., Wolf,K. and Mueller,M.W. (1994) J. Mol. Biol., 243, 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sellem C.H., Lecellier,G. and Belcour,L. (1993) Nature, 366, 176–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cousineau B., Smith,D., Lawrence-Cavanagh,S., Mueller,J.E., Yang,J., Mills,D., Manias,D., Dunny,G., Lambowitz,A.M. and Belfort,M. (1998) Cell, 94, 451–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang J., Mohr,G., Perlman,P.S. and Lambowitz,A.M. (1998) J. Mol. Biol., 282, 505–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmerly S., Guo,H., Perlman,P.S. and Lambowitz,A.M. (1995) Cell, 82, 545–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmerly S., Guo,H., Eskes,R., Yang,J., Perlman,P.S. and Lambowitz,A.M. (1995) Cell, 83, 529–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuura M., Saldanha,R., Ma,H., Wank,H., Yang,J., Mohr,G., Cavanagh,S., Dunny,G.M., Belfort,M. and Lambowitz,A.M. (1997) Genes Dev., 11, 2910–2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eskes R., Yang,J., Lambowitz,A.M. and Perlman,P.S. (1997) Cell, 88, 865–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cousineau B., Lawrence,S. and Belfort,M. (2000) Nature, 404, 1018–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martínez-Abarca F., Zekri,S. and Toro,N. (1998) Mol. Microbiol., 28, 1295–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martínez-Abarca F., García-Rodríguez,F.M. and Toro,N. (2000) Mol. Microbiol., 35, 1405–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 15.Beringer J.E. (1974) J. Gen. Microbiol., 84, 188–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertsen B.K., Aiman,P., Darvill,A.G., McNeil,M. and Alberstein,P. (1981) Plant Physiol., 67, 389–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Segundo E., Martínez-Abarca,F., van Dillewijn,P., Fernández-López,M., Lagares,A., Martínez-Drets,G., Niehaus,K., Pühler,A. and Toro,N. (1999) FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 28, 169–176 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toro N. and Olivares,J. (1986) Mol. Gen. Genet., 202, 231–235. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovach M.E., Phillips,R.W., Elzer,P.H., Roop,R.M. and Peterson,K.M. (1994) Biotechniques, 16, 800–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ditta G., Stanfield,S., Corbin,D. and Helsinski,D.R. (1980) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 77, 7347–7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perego M., Glaser,P., Minutello,A., Strauch,M.A., Leopold,K. and Fischer,W. (1995) J. Biol. Chem., 270, 15598–15606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romine M.F., Stillell,L.C., Wong,K.K., Thurson,S.J., Sisk,E.C., Sensen,C., Gaasterland,T., Fredrickson,J.K. and Saffer,J.D. (1999) J. Bacteriol., 181, 1585–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doak T.G., Doerder,F.P., Jahn,C.L. and Herrick,G. (1994) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 942–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martínez-Abarca F., García-Rodríguez,F.M., Muñoz,E. and Toro,N. (1999) Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser., 41, 117–119. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mills D.A., Mckay,L.L. and Dunny,G.M. (1996) J. Bacteriol., 178, 3531–3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferat J.L., Le Gouar,M. and Michel,F. (1994) C. R. Acad. Sci. III, 317, 141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knoop V. and Brennicke,A. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 1167–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mullany P., Pallen,M., Wilks,M., Stephen,J.R. and Tabaqchali,S. (1996) Gene, 174, 145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shearman C., Godon,J.J. and Gasson,M. (1995) Mol. Microbiol., 21, 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeo C.C., Tham,J.M., Yap,M.W.-C. and Poh,C.L. (1997) Microbiology, 143, 2833–2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Selbitschka W., Arnold,W., Jording,D., Kosier,B., Toro,N. and Pühler,A. (1995) Gene, 163, 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo H., Zimmerly,S., Perlman,P.S. and Lambowitz,A.M. (1997) EMBO J., 16, 6835–6848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohr G., Smith,D., Belfort,M. and Lambowitz,A.M. (2000) Genes Dev., 14, 559–573. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]