Abstract

Introduction

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) is a primary cicatricial alopecia with mixed infiltrate. It is more common in Africans or persons of African descent.

Objectives

Our objective was to describe the epidemiology and clinical and trichoscopic presentations of AKN in a large series of Hispanic patients.

Methods

This was a retrospective study from 10 different dermatological centers in Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. Patients with a clinical diagnosis of AKN treated by 12 dermatologists experienced in trichology from 2018 to 2022 were included. The Umar classification system was used to determine severity.

Results

We identified 142 patients with AKN: 98% were male (n=140) with a mean age of 32 years; 108 patients had a previous history of trauma to the nuchal area (76%, P < 0.001); and 48 were positive for a history of acne (33.8%, P = 0.021). Patients with >50 months of evolution were mainly classified in classes III and IV compared to patients with an evolution of <50 months (30%, n=9 vs. 14%, n=15; P = 0.019; respectively).

Conclusion

AKN should be considered in the differential diagnosis in the Hispanic population. Advanced stages of the disease are correlated with chronic evolution.

Keywords: acne keloid, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, Hispanic or Latino, follicular occlusive disorders

Introduction

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN), also known as folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, is a chronic scalp disease first described by Hebra in 1860. AKN mainly affects young male patients (20:1), especially African patients or those of African descent [1]. This scarring alopecia begins in the nuchae region with papules and pustules that may evolve to nodules and plaques [1,2]. In severe cases, keloid-like hypertrophic masses occur [1,2].

The etiology of AKN remains unclear, the most widely accepted theory being an immune response leading to incipient folliculitis caused by local trauma from razor use in the nuchal area or use of a helmet, but also by ingrown hairs due to the kinky nature of the hair and curvature of the follicular type, which is more prevalent in the African American population [1–5]. Some studies have suggested a genetic, metabolic, and hormonal component in the development of this condition, but none has been proven [6–9]. The trichoscopic features have been described, such as hair tuft and loss of follicular ostia, but these findings are not pathognomonic either [10,11].

Most studies on AKN have been performed in patients of African descent, and it is likely that racial factors are critical to disease development and response to treatment [1–3].

Objective

The aim of this study was to describe the epidemiology and clinical and trichoscopic characteristics of Hispanic patients with AKN.

Methods

This was a retrospective study involving patients from 10 different dermatological centers in Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru with a clinical diagnosis of AKN or folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, from 2018 to 2022. The medical records of the patients with AKN were reviewed and registered in a database for further statistical analyses. Clinical evaluation was performed by 12 dermatologists experienced in trichology. The Umar classification was used to determine the severity accordingly:

Distribution: class I: occipital area (OA) < 3 cm, class II: OA > 3 cm < 6.5 cm, class III: OA > 6.5 cm, class IV: beyond the occipital notch.

Morphology: discrete papules and nodules, merged papules and nodules, plaque, or tumorous mass.

Associated diseases were also investigated, such as folliculitis decalvans (FD), dissecting cellulitis (DC), or pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB). Trichoscopic analysis was performed using manual dermoscopy (DermLite) or digital dermoscopy (FotoFinder) devices. The data procured were subjected to descriptive statistics analyses (medians, ranges, and proportions) and inferential statistics (Fisher’s exact test and Chi-square test).

Results

In ten clinical dermatology centers in Argentina, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico, 142 patients with AKN were identified (Table 1): 140 were male (98.6%) and two were female (1.4%). The age at onset ranged from 18 to 41 years, with a mean of 32 years. Two patients were Caucasian (1.4%), one was of African American descent (0.7%), and the remaining 139 were Hispanic (97.8%).

Table 1.

Comparisons of Demographics and Clinical Characteristics for Our Study Sample With Findings from Umar et al. [3] and Lobato-Berezo et al. [11]

| Statistical Values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Statistics/Categories | Our Study Sample | Umar et al. (2021) | Lobato-Berezo et al. (2023) |

| Demographic | ||||

| Sex: N (%) | Male | 140 (98.6) | 100 (100) | 75 (94.94) |

| Female | 2 (1.4) | - | 4 (5.06) | |

| Ethnicity: N (%) | Hispanic | 139 (97.8) | 40 (37) | 11 (14.29) |

| Caucasian | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 32 (41.56) | |

| African American | 1 (0.7) | 62 (58) | 9 (11.69) | |

| Middle Eastern | - | 2 (2) | 6 (7.79) | |

| Asian | - | 3 (3) | 4 (5.19) | |

| African | - | - | 15 (19.48) | |

| Medical history | ||||

| Acne, n (%) | 48 (33.8) | 42 (39) | 11 (14.29) | |

| FD, n (%) | 10 (7) | 7 (7) | 16 (20.25) | |

| DC, n (%) | 3 (2.1) | 1 (1) | 5 (6.33) | |

| PFB, n (%) | 8 (5.6) | - | 15 (19.48%) | |

| Clinical classification | ||||

| Lesion distribution | Class I, n (%) | 71 (50) | 17 (16) | 32 (41.03) |

| Class II, n (%) | 45 (31.6) | 63 (58) | 26 (33.33) | |

| Class III, n (%) | 21 (14.7) | 21 (19) | 20 (25.64) | |

| Class IV, n (%) | 5 (3.5) | 7 (7) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Lesion type | Discrete papules/nodules, n (%) | 14 (9.8) | 2 (2) | 46 (58.97) |

| Merge Papules/Nodules, n (%) | 101 (71.1) | 48 (44) | 14 (17.95) | |

| Plaque, n (%) | 21 (14.7) | 40 (37) | 9 (11.54) | |

| Tumorous Mass, n (%) | 6 (4.2) | 18 (17) | 9 (11.54) | |

| Main trichoscopic findings | ||||

| Tufted Hairs, n (%) | 60 (42.2) | - | - | |

| Erythema, n (%) | 80 (56.3) | - | - | |

| Pustules, n (%) | 69 (48.5) | - | - | |

| Treatment | ||||

| Antibiotics, n (%) | 58 (41) | 29 (27) | 44 (56.41) | |

| Oral retinoids, n (%) | 19 (13) | 2 (2) | 47 (60.26) | |

| Laser, surgery and ablation, n (%) | 4 (2.8) | 7 (7) | 10 (12.66) | |

| Topical steroids, n (%) | 21 (19) | 8 (7) | 28 (35.90) | |

| Systemic steroids, n (%) | 5 (3.5) | - | 7 (8.97) | |

| Intralesional steroids, n (%) | 20 (14) | 45 (42) | 48 (61.54) | |

One patient from Dr. Umar had no ethnicity listed.

DC = dissecting cellulitis; FD = folliculitis decalvans; PFB = pseudofolliculitis barbae.

In terms of personal history, 108 patients had a history of trauma to the nuchal area (76%, P < 0.001) and 48 had a history of acne (33.8%, P = 0.021). Interestingly, in addition to the AKN diagnosis, 10 patients were diagnosed with FD (7%), eight with PFB (5.6%), three with DC (2.1%), and one with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) (0.7%, n=1). Only seven patients had other non-dermatological comorbidities (4.9%), all of whom were diagnosed with dyslipidemia (100%, n=7).

The main distribution corresponded to classes I and II of the Umar classification system (Figures 1 and 2), with 116 identified in these classes (81.6%), class III with 21 patients (14.7%) (Figures 3 and 4), and class IV with five patients (3.5%). The main clinical lesions were papules and nodules, which were found in 115 (80.9%), plaque in 21 patients (14.7%), and tumorous mass in six patients (4.2%) (Figures 3 and 4). Regarding the trichoscopic findings, we found that 80 patients had diffuse erythema (56.3%), 69 patients had pustules (48.6%), and 60 patients had tufted hairs (42.2%) (Figure 2). In addition, 65 of the patients with diffuse erythema were classified as either class I or II (81.25%, n=80).

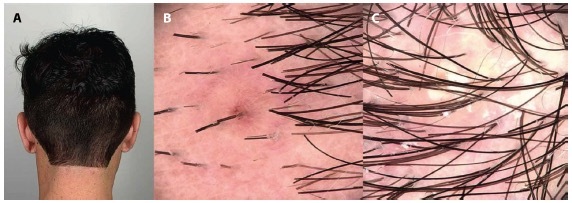

Figure 1.

(A) A 24-year-old male with acne keloidalis nuchae, class I, discrete papules and nodules. (B, C) Trichoscopy: follicular papules with dotted vessels and follicular pustules.

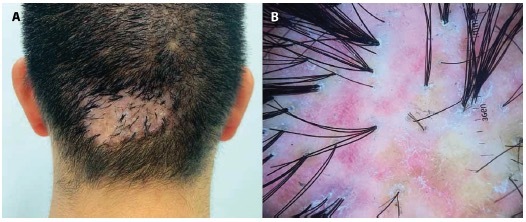

Figure 2.

(A) A 32-year-old male with acne keloidalis nuchae class III, tumorous mass, (B) Trichoscopy: perifollicular scale, unstructured red areas, unstructured white areas, and tufted hairs.

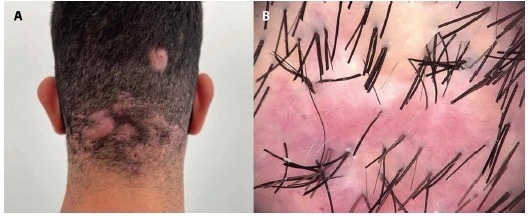

Figure 3.

(A) A 25-year-old male with acne keloidalis nuchae class III, grouped papules and nodules associated with dissecting cellulitis. (B) Trichoscopy: perifollicular erythema, unstructured red areas, unstructured white areas, and tunneled hairs.

Figure 4.

(A) A 65-year-old male with acne keloidalis nuchae, 10-year history, class III, tumorous mass. (B) Results after surgical removal of tumoral mass and secondary intention healing.

The most common treatment among all patients was systemic antibiotic in 31 patients (21.8%). Laser and surgery were performed in four of the patients (2.8%) (Figure 4 A and B).

The patients were divided into two groups according to the chronicity of their disease: 1) patients with an evolution of ≤50 months, and 2) patients with an evolution time >50 months. We found that most patients who had >50 months of evolution of the disease were mainly classes III and IV compared to patients with an evolution of ≤ 50 months (30%, n=9 vs. 14%, n=15; P = 0.019; respectively). The other comparisons were not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our results showed that male was the predominant sex affected by AKN in the Hispanic population, with a mean age at onset of 32 years, which is consistent with reports from other studies [7–11]. Shaving of the nape of the neck was the main risk factor, in agreement with similar studies in other populations, reflecting mechanical trauma also observed in patients wearing helmets [1,2].

Recently, Umar et al. reported a classification system for AKN: 1) based on the distribution of lesions in terms of the area between two lines parallel to the occipital prominence and mastoid processes, defined in classes I to IV, and 2) according to the type of lesions in isolated papules/nodules, grouped papules/nodules, plaques, and tumorous masses [5]. This classification provides an objective clinical description of patients with AKN and assesses the subsequent response to treatment [5]. Patients who reported a risk factor for the disease were classified as either class I or II (88.8%, n=108), suggesting that this acts as a trigger for the development of the disease (Table 1). We found that patients classified as class IV, with extension beyond the occipital notch, had >50 months of evolution. We hypothesize that Hispanic patients may evolve to a more extensive disease over time, which is different from what other studies have reported and that that AKN remains stable over time.

Follicular occlusive disorders such as acne vulgaris/conglobata, DC, and HS occurred in 52 patients (36.6%), which was similar to that reported by East-Innis et al. (37%) and Lobato-Berezo et al., who also reported a prevalence of 37.2% for this group of disorders (Table 1) [5,10,12]. The most common skin disease related in our study was acne vulgaris (33%), followed by FD (7%). In contrast, PFB was less frequent (5%) in our population than in other reports [5,10,12].

We were able to identify the following trichoscopic findings: follicular papules with hair shafts, follicular papules with dotted vessels, follicular pustules, perifollicular erythema, perifollicular scale, unstructured red areas, unstructured white areas, tunneled hairs, yellowish crusts, and tufted hairs. Interestingly, most patients in classes III and IV had tufted hairs, suggesting that there is a higher chance of identifying this trichoscopic finding in a wider distribution of AKN. In classes I and II, the erythema and pustules were the most frequent trichoscopic findings (Table 1).

AKN represents a therapeutic challenge because none of the available treatments has been shown to be reliable in all patients [6]. Medical therapy (mainly with antibiotics, steroids, and retinoids), laser therapy (Nd:YAG, CO2 and diode), cryosurgery, and surgical approaches are the main therapies currently used (Figures 4A and 3B) [1,2,3]. In our study, systemic antibiotic treatment was the most used therapy (Table 1). However, all of them have different response rates, and relapse may occur [1,3].

Limitations

The limitations of this study are its retrospective nature and the lack of histopathologic correlation. Further studies may help establish criteria to differentiate AKN from other follicular occlusive diseases.

Conclusions

AKN is a complex disease that should be considered not only as a single entity, but also as a scarring alopecia within other follicular occlusive diseases such as acne, DC, and HS. AKN is a disease that could be more common than what we think in the Hispanic population, and further studies in specific populations are required to establish specific risk factors. Most patients within classes III and IV had tufted hairs, suggesting that there is a higher chance of identifying this trichoscopic finding in a widespread disease. Advanced stages of the disease correlate with chronic evolution.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing Interests: None.

Authorship: All authors have contributed significantly to this publication.

References

- 1.Ogunbiyi A. Acne keloidalis nuchae: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:483–489. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S99225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adegbidi H, Atadokpede F, do Ango-Padonou F, Yedomon H. Keloid acne of the neck: epidemiological studies over 10 years. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(Suppl 1):49–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maranda EL, Simmons BJ, Nguyen AH, Lim VM, Keri JE. Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae: a systematic review of the literature. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2016;6(3):363–78. doi: 10.1007/s13555-016-0134-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapero J, Shapero H. Acne keloidalis nuchae is scar and keloid formation secondary to mechanically induced folliculitis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2011;15(4):238–40. doi: 10.2310/7750.2011.10057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Umar S, Lee DJ, Lullo JJ. A retrospective cohort study and clinical classification system of acne keloidalis nuchae. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(4):E61–E67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loayza E, Vanegas E, Cherrez A, Cherrez Ojeda I. Acne keloidalis nuchae in Latin America: is there a different phenotype? Int J Dermatol. 2017;56(12):1469–1470. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loayza E, Cazar T, Uraga V, Lubkov A, Garces JC. Acne keloidalis nuchae in Latin American women. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(5):e183–5. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kridin K, Solomon A, Tzur-Bitan D, Damiani G, Comaneshter D, Cohen AD. Acne keloidalis nuchae and the metabolic syndrome: a population-based study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(5):733–739. doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00541-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsunaga AM, Tortelly VD, Machado CJ, Pedrosa LR, Melo DF. High Frequency of Obesity in Acne Keloidalis Nuchae Patients: A Hypothesis from a Brazilian Study. Skin Appendage Disord. 2020 Nov;6(6):374–378. doi: 10.1159/000509203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.East-Innis ADC, Stylianou K, Paolino A, Ho JD. Acne keloidalis nuchae: risk factors and associated disorders - a retrospective study. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56(8):828–832. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Na K, Oh SH, Kim SK. Acne keloidalis nuchae in Asian: A single institutional experience. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0189790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lobato-Berezo A, Escolá-Rodríguez A, Courtney A, et al. Acne keloidalis nuchae: An international multicentric review of 79 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023 doi: 10.1111/jdv.19609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chouk C, Litaiem N, Jones M, Zeglaoui F. Acne keloidalis nuchae: clinical and dermoscopic features. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017222222. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-222222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]