Abstract

Introduction

Adult female acne is a chronic condition that significantly impacts quality of life. The content on social media can influence patients perception of their disease and serve as a channel through which they may seek or obtain treatment options.

Objectives

This study aims to evaluate the impact of social media usage habits on treatment decisions among adult female acne patients.

Methods

A cross-sectional, multicenter survey study involved 358 females aged 25 or above, diagnosed with acne. Sociodemographic data were collected, and social media behavior, treatment choices, outcomes, and motivation were explored.

Results

Among 358 participants, 95.3% used at least 1 social media platform; 72.1% sought acne information online. Top platforms used to seek acne information were Google (75.6%), Instagram (72.3%), YouTube (60%), and TikTok (29.4%). For advice, 67.4% consulted doctor accounts, 53.5% non-medical influencers, 53.5% patient accounts, and 36.1% product promotion accounts. Commonly followed advice included skincare products (88%), dietary changes (42.3%), home remedies (38.8%), exercise (30.3%), topical medications (25.2%), and dietary supplements (17.4%). Notably, 20.9% were willing to alter prescribed treatment by their physician for acne based on social media advice. Patient motivations included quick information access (84.1%) and difficulty in securing dermatologist appointments (54.3%).

Conclusions

The study reveals widespread social media use among adult female acne patients, highlighting concerns about potentially misleading information. Dermatologists can enhance the impact of social media by providing reliable sources for patients.

Keywords: acne vulgaris, social media, treatment, Internet, dermatology

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a chronic multifactorial disease of the pilosebaceous follicle. It has typically been regarded as an adolescent condition; however, recent data show that a substantial number of adults aged over 25 years are also affected, particularly women. The estimated prevalence of adult female acne demonstrates regional and ethnic variability, ranging from 12% to 41% [1–3]. Acne impairs the quality of life among those individuals, and it negatively impacts self-perceptions, emotional well-being, and social functioning [4,5].

In the last two decades, the internet and social media have become integral parts of our lives, bringing about revolutionary changes in social communication and the exchange of information. The trend of seeking medical information online has been on the rise, with 75% of Internet users now using search engines or social media to access health-related information [6]. People use the internet not only for self-diagnosing their conditions, obtaining information about specific ailments, and exploring alternative therapies but also to connect with individuals who share similar health experiences and provide social support [6]. This shift reflects the evolving landscape of patient empowerment, where individuals actively engage in their health decisions.

A series of recent studies have investigated social media use among acne patients and assessed the practice of self-medication and/or intervention to treat acne. A study conducted by Aslan Kayıran et al concluded that 71% of patients use social media to make inquiries about acne vulgaris [7]. Some other studies found that 42% to 55% of acne patients consulted social media on the choice of treatment [8–10]. The internet and social media, while holding enormous potential for the dissemination of evidence-based information and disease prevention, also pose significant risks, notably in the form of the dissemination of misleading and potentially hazardous content. The unregulated nature of online content can potentially expose individuals to misinformation, rendering them susceptible to making erroneous health-related decisions [11]. For instance, Borba et al conducted a cross-sectional study that assessed the quality and accuracy of acne-related videos on YouTube. Their findings indicated that viewers were consistently exposed to markedly inaccurate and low-quality information [12]. Similarly, Yousaf et al study found that 69% of patients who sought acne treatment advice on social media made changes not fully aligned with the American Academy of Dermatology acne management guidelines [10].

Objectives

The literature suggests that social media has a significant impact on acne management. However, no study has specifically focused on the social media behavior of adult female acne patients. This particular target group may introduce potentially different dynamics, given their distinct generational background compared to teenagers. The objective of this study is to explore social media usage among adult female acne patients and to evaluate their treatment choices and outcomes.

Methods

Survey Methods and Procedure

The study was approved by the Koç University Institutional Review Board (IRB no: 2023.082.IRB1.030). It included female acne patients aged over 25 years who presented at various dermatology outpatient clinics in Turkey between March 2023 and May 2023.

Survey questions were prepared by the researchers who planned the study. A 2-page questionnaire was hand-delivered to ambulatory adult female acne patients. The patients were asked to complete the questionnaire, which consisted of 14 items, including age, duration of acne, patient-reported acne severity, daily social media usage, platforms consulted, treatment and/or lifestyle changes based on social media, and patient-perceived improvement from social media suggestions. The questionnaire was anonymous, and patients were expected to complete it without any time limitations.

Statistical Analysis

The sample sizes Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0 (SPSS Inc.). Data for qualitative variables were presented as a number (percentage), and data for quantitative variables as mean ± standard deviation. The Pearson χ2 test or Fisher exact test was used to compare the qualitative variables. A P value <0.05 was taken as significant.

Results

Patients Characteristics and Social Media/Internet Usage to Seek Medical Information

A total of 358 women were included to the study, with a mean age of 29.98 ± 0.24 years. Among the participants, 44.4% exhibited persistent or intermittent acne since adolescence, while 55.6% experienced its onset during adulthood. The average disease duration was 71.30 ± 3.86 months. Notably, most respondents held a university degree or higher (65.4%). Regarding acne severity, 51.1% reported a moderate level, and 52.5% indicated that acne frequently or always had a negative impact on their self-esteem.

Physician consultation emerged as the primary choice for acne treatment among most patients (56.4%). Additionally, 77.7% of participants reported spending at least one hour daily on social media. A significant proportion (72.1%) sought medical information about acne vulgaris from social media and the Internet, with the prevalence being statistically significantly higher among those with an extended disease duration, more severe acne, frequent negative effects on self-esteem, and increased daily social media usage (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Social Media/Internet Usage to Obtain Medical Information.

| Variables | Social Media and Internet Consultation (total N = 258) N (%) | No Social Media and Internet Consultation (total N = 100) N (%) | Total N (%) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (Mean ± SD) | 30.04 ± 0.27 | 29.85 ± 0.52 | 29.98 ± 0.24 | .184 |

| Disease duration, months (Mean± SD) | 75.95 ± 4.56 | 59.30 ± 6.96 | 71.30 ± 3.86 | .004 |

| Education level | .736 | |||

| High school or lower | 88 (71.0) | 36 (29) | 124 (34.5) | |

| University degree or higher | 170 (72.6) | 64 (27.4) | 234 (65.4) | |

| Patient-reported acne severity | .003 | |||

| Mild | 56 (59.6) | 38 (40.4) | 94 (26.3) | |

| Moderate | 136 (74.3) | 47 (25.7) | 183 (51.1) | |

| Severe | 66 (81.5) | 15 (18.5) | 81 (22.6) | |

| Patient-reported negative impact of acne on self-esteem | .000 | |||

| No impact | 24 (46.2) | 28 (53.8) | 52 (14.5) | |

| Occasionally | 77 (65.3) | 41 (34.7) | 118 (33.0) | |

| Frequently | 95 (85.6) | 16 (14.4) | 111 (31.0) | |

| Always | 62 (80.5) | 15 (19.5) | 77 (21.5) | |

| Average daily time spent on social media | .003 | |||

| None | 8 (47.1) | 9 (52.9) | 17 (4.7) | |

| < 1 hours | 39 (61.9) | 24 (38.1) | 63 (17.6) | |

| 1–3 hours | 103 (71.0) | 42 (29.0) | 145 (40.5) | |

| >3 hours | 108 (81.2) | 25 (18.8) | 133 (37.2) | |

| First source of choice to acne treatment | .000 | |||

| Internet/social media | 76 (100) | 0 (0) | 76 (21.2) | |

| Family/friends | 13 (43) | 17 (57) | 30 (8.4) | |

| Pharmacists | 41 (82.0) | 9 (18.0) | 50 (14.0) | |

| Physician/Dermatologist | 128 (63.4) | 74 (36.6) | 202 (56.4) |

Social Media/Internet Using Patterns and Its Impact on Treatment Choices

Respondents primarily accessed searching engines (Google, Yandex, etc) (75.6 %), İnstagram (72.3%) and YouTube (60%), followed by TikTok (29.4%), personal blogs/websites (22.5%), Facebook (19.8%) and Snapchat (0.8%) when seeking information about acne (Table 2). When asked about their preferred source of choice on social media for obtaining information about acne, 67.4% followed recommendations from medical doctor accounts, 53.5% from non-medical social media influencers, 53.5% from patient groups/accounts and 36.1% from dermatological product retailers/companies.

Table 2.

Details of Social Media Use Patterns and Treatment Modalities Followed Among Individuals With Adult Female Acne.

| Parameters | N (%, out of 258) |

|---|---|

| Social media platforms used | |

| Search engines (Google, Yandex, etc.) | 195 (75.6) |

| 188 (72.3) | |

| YouTube | 155 (60.0) |

| Tiktok | 76 (29.4) |

| Personal blogs | 58 (22.5) |

| 51 (19.8) | |

| Snapchat | 2 (0.8) |

| Source of choice for obtaining information | |

| Medical doctor accounts/webpages | 174 (67.4) |

| Social media influencers (non-medical) | 138 (53.5) |

| Patient groups/accounts on social media | 138 (53.5) |

| Dermatological product retailers/companies | 93(36.1) |

| Other | 30 (11.6) |

| Subjects of inquiry concerning acne vulgaris on social media | |

| Acne scars/marks | 180 (69.8) |

| Pore/blackhead/comedones | 177 (68.7) |

| Oily skin | 129 (50.0) |

| Red/inflamed pimples | 128 (49.6) |

| Cysts and/or nodules | 58 (22.5) |

| Change of acne after following the treatment recommendation on social media | |

| No change | 83 (32.2) |

| Minimal improvement | 110 (42.6) |

| Significant improvement | 2 (0.8) |

| Worsened | 33 (12.8) |

| Did not follow any recommendations on social media | 30 (11.6) |

| Have you ever changed a treatment prescribed by your doctor for acne based on recommendation obtained from the social media? | |

| Yes | 54 (20.9) |

| No | 204 (79.1) |

Table 3.

Patients Motivations to Use Social Media for Obtaining Information About Acne.

| Motivation | N (%, out of 258) |

|---|---|

| Quick and easy access to information provided on social media/internet | 217 (84.1) |

| Affordability | 76 (29.5) |

| The persuasive impact of the before-and-after photos posted on social media | 114 (44.2) |

| The difficulty/long wait list for the appointment with a dermatologist | 140 (54.3) |

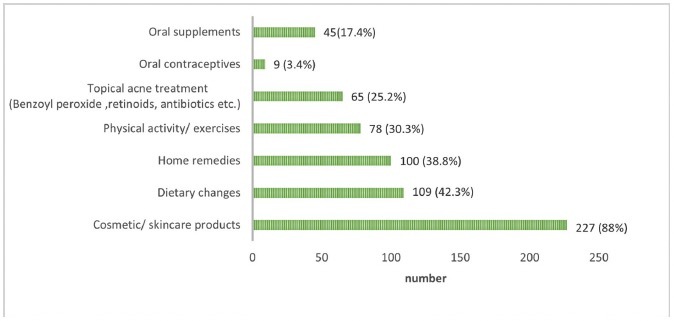

Respondents most frequently made inquiries concerning acne scars/marks (69.8%) and pores/comedones (68.7%); followed by oily skin (50.0%), red and inflamed pimples (49.6%) and cysts and/or nodules (22.5%). Regarding tried acne treatments based on social media recommendations, cosmetic/skin-care products was reported by 88%, followed by dietary changes (42.3%), home remedies (38.8%), physical activity/exercises 30.3%, over-the-counter topical acne medications (25.2%), oral supplements (17.4%) and oral contraceptives (3.4%) (Figure 1). Only 30 patients (11.6%) reported that they have not followed any recommendations from social media regarding on their acne treatment. Notably, 42.6% of the participants noticed minimal improvement in their acne after using recommendations from social media, while only 0.8% noticed a significant improvement (Table 2). A small portion of the respondent (20.1%) reported changing a treatment prescribed by their doctor for acne based on recommendation obtained from social media.

Figure 1.

Treatment and lifestyle changes as per social media. Percentage distribution of treatment and/or lifestyle changes influenced or guided by information from social media and the Internet.

Patients Motivations to Use Social Media/Internet for Seeking Information About Acne

In relation to the motivations of participants to utilize social media for acquiring information about acne, the predominant incentive was the quick and easy access to information (84.1%), followed by the challenge in securing appointments with dermatologists (54.3%), the persuasive impact of before-and-after photos posted on social media (44.2%), and considerations of affordability (29.5%).

Conclusions

The prevalence of acne vulgaris among adult females is a notable concern, affecting both quality of life and psychosocial well-being of individuals. With the increasing influence of the internet and social media, patients are turning to online platforms for health-related information. The present study reveals that a substantial portion of adult female acne patients (72.1%) actively seeks information about their condition on social and on the Internet, and a further 88.4% of them followed at least one recommendation from social media and the Internet regarding their acne treatment. This engagement underscores the influential role of digital platforms in shaping the medical decision-making process for patients dealing with adult female acne.

The landscape of healthcare-seeking behaviors among dermatology patients is undergoing a transformative shift with the burgeoning prevalence of internet and social media use. In a recent questionnaire-based study, it was revealed that a substantial 82.4% of patients consulted the Internet and social media for medical information [11]. Additionally, in another study, acne vulgaris emerged as the most frequently searched skin-related condition on social media, accounting for 54.2%, followed by eczema (19.8%) and hair loss (17.7%) respectively [13]. Furthermore, the findings of a separate study exploring the most common dermatology-related content on Instagram highlighted that acne was the most prevalent cutaneous disease-related hashtag [14]. This tendency among acne patients to utilize social media platforms can be attributed to its status as one of the most common dermatological diseases, particularly prevalent among a relatively young population. While a limited number of studies have explored social media use among acne patients and its potential impact on treatment, our study is the first, to our knowledge, to specifically investigate these trends in adult female acne patients [7,8,10].

Our findings indicated that 72.1% of participants sought medical information about acne vulgaris from social media and the Internet, aligning closely with a recent Turkish study where 75.1% of patients with acne utilized these platforms for disease-related information [7].

In other studies, specifically addressing the impact of social media use on acne vulgaris treatment, respondents reported seeking treatment advice, with prevalence varying from 42.4% to 83.3% across different studies [8,10,15,16]. These variations in social media usage trends for acne may be attributed to geographic disparities, study years, and the demographics of participants, including age and sex. Furthermore, in line with prior studies, our research reveals a significant correlation between the severity and duration of acne and the search for medical information on social media. [7,8]. This may be attributed to a higher disease burden, which encourages patients to engage in more active treatment advice-seeking behavior.

In our current study, the most frequently consulted online platforms by our patients were Google, Instagram, and YouTube, in descending order. These findings align with a previous study involving 1609 patients investigating social media use among individuals with acne, where 67% of participants reported using Google, 54% Instagram, and 49% YouTube for inquiries [7]. Gantenbain et al reached a similar conclusion, stating that, similar to non-dermatology patients, Google and YouTube were the two online platforms most commonly accessed by dermatology patients for medical information in general [11]. The prevalence of video content on YouTube and Instagram may contribute to their increased engagement among patients.

The findings of the present study suggest that a significant number of participants made lifestyle changes and/or engaged in self-medication based on information obtained from online platforms. Notably, some practices diverged from current international acne management guidelines, including dietary changes (42.3%), the use of home remedies (38.8%), and oral supplements (17.4%). Of particular concern is the small yet noteworthy percentage (3.4%) of participants who initiated oral contraceptive use for acne without seeking professional consultation. These results find resonance in the study by Yousaf et al, wherein 48% of numerous social media users incorporated lifestyle changes not supported by acne treatment guidelines, such as dietary adjustments and supplement use [10]. Another study revealed that 33.7% of social media users commenced acne treatment without a prescription, including topical benzoyl peroxide, retinoic acid, and topical antibiotics [8]. The authors of that study expressed concern about the potential side effects and harms associated with obtaining prescription drugs without proper medical guidance. In Lima et al study, 10.1% of participants reported experiencing complications or side effects after following treatment advice from social media, predominantly in the form of skin irritation, worsening of acne, and the development of spots [16].

Notably, in our study 88.4% of the participants who used social media and the Internet to seek information about acne, did follow at least a treatment advice from those platforms. Only 0.8% of them reported significant improvement in their acne, while 32.2% stated that there were no changes and 12.8% worsening of acne. Similarly, in the study of Yousaf et al 6.9% of the patients reported a significant improvement and 39.7% no change in their acne from social media acne treatment advice. These findings may raise concerns about potential delays in receiving proper acne treatment and preventing complications such as scarring or high psychosocial impact. Our study findings, indicating that 20.9% of patients would alter their physician-prescribed acne treatment based on social media recommendations, align with the observations by Aslan Kayıran et al, who reported that 15.3% of participants would seek a second opinion or additional information on social platforms if it contradicted their physician advice [7]. These collective results underscore the considerable influence of online platforms in shaping healthcare decisions.

In exploring the motivations driving patients to seek medical information on social media, our study reveals that 84.1% of participants are primarily motivated by the quick and easy access to information offered by these platforms, highlighting their convenience in disseminating healthcare-related content. Additionally, the persuasive impact of before-and-after photos on social media emerges as a significant motivator, influencing nearly half of the participants and emphasizing the visual appeal and persuasive nature of such content in shaping perceptions and decisions regarding acne treatment. Furthermore, our findings illuminate the challenges patients encounter in accessing traditional healthcare services, with 54.3% citing difficulties or long wait lists for dermatologist appointments as a motivation to turn to social media. Comparatively, Kaliyadan et al found financial reasons, self-perceived mild severity, and a lack of available appointments as discouraging factors for participants consulting a dermatologist for their acne [15].

In our study, diverse sources were chosen by participants for obtaining information online for acne. Medical doctor accounts and webpages emerged as the primary source for 67.4% of respondents, underscoring the continued trust and reliance on professional medical expertise in the digital era. Concurrently, the substantial reliance on non-medical social media influencers (53.5%) and patient groups/accounts on social media (53.5%) signals a notable shift towards peer-driven and influencer-led health information seeking. Moreover, the significant engagement with dermatological product retailers and companies (36.1%) suggests an increasing interest in commercial entities as sources of information, possibly influenced by the intersection of healthcare and the market. Several studies have highlighted patients distinct preference for receiving high-quality professional advice on dermatological issues, including acne and their wish for dermatologists to contribute more professional content on social media [7,11]. This emphasis is crucial due to the prevalence of unscientific, misleading, and low-quality information found in the majority of acne-related content on social media, as demonstrated in various studies [12,17,18]. Additionally, research indicates that poor-quality videos tend to be more engaging for the public, accruing significantly higher viewer counts compared to high-quality videos [12]. The persistence of such misinformation poses a significant challenge. Without effective intervention, clinicians may find themselves spending considerable time correcting inaccuracies acquired by patients from these platforms. It is also important to note that to prevent the creation of fake accounts that impersonate healthcare professionals, verifying the legitimacy of any accounts created on social media with a username that includes a doctor abbreviation might be logical. This could be achieved by requesting a username and password from an additional medical digital platform (ORCID, Clarivate, medical license number, etc) in order to complete the registration process.

Despite the extensive sample size in our study, an important limitation merits attention. The recruitment of study subjects exclusively from patients seeking medical consultation introduces a potential bias, as a substantial group of patients resorts to self-treatment based on diverse internet-derived knowledge. This could impact the generalizability of our findings.

In conclusion, our study sheds light on the significant impact of social media on the healthcare-seeking behaviors and treatment decisions of adult female acne patients. The findings underscore the need for targeted interventions to address the impact of social media on treatment decisions, mitigate potential risks associated with misinformation, and promote collaborative efforts between healthcare providers and patients in the digital age.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing Interests: None.

Authorship: All authors have contributed significantly to this publication.

References

- 1.Poli F, Dreno B, Verschoore M. An epidemiological study of acne in female adults: results of a survey conducted in France. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(6):541–545. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perkins AC, Maglione J, Hillebrand GG, Miyamoto K, Kimball AB. Acne vulgaris in women: prevalence across the life span. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21(2):223–230. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorelick J, Daniels SR, Kawata AK, et al. Acne-Related Quality of Life Among Female Adults of Different Races/Ethnicities. J Dermatol Nurses Assoc. 2015;7(3):154–162. doi: 10.1097/JDN.0000000000000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanghetti EA, Kawata AK, Daniels SR, et al. Understanding the burden of adult female acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(2):22–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dreno B, Bagatin E, Blume-Peytavi U, Rocha M, Gollnick H. Female type of adult acne: Physiological and psychological considerations and management. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16(10):1185–1194. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Y, Zhang J. Consumer health information seeking in social media: a literature review. Health Info Libr J. 2017;34(4):268–283. doi: 10.1111/hir.12192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aslan Kayıran M, Karadağ AS, Alyamaç G, et al. Social media use in patients with acne vulgaris: What do patients expect from social media? J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(8):2556–2564. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahaj RK, Alsaggaf ZH, Abduljabbar MH, Hariri JO. The Influence of Social Media on the Treatment of Acne in Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2022;14(3):e23169. doi: 10.7759/cureus.23169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agarwala MK, Shukla A, Chandrakar R. The Impact of Social Media on Management of Acne: A Survey from Central India. International Journal of Academic Medicine and Pharmacy. 2022 February;:188–190. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yousaf A, Hagen R, Delaney E, Davis S, Zinn Z. The influence of social media on acne treatment: A cross-sectional survey. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37(2):301–304. doi: 10.1111/pde.14091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gantenbein L, Navarini AA, Maul LV, Brandt O, Mueller SM. Internet and social media use in dermatology patients: Search behavior and impact on patient-physician relationship. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6):e14098. doi: 10.1111/dth.14098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borba AJ, Young PM, Read C, Armstrong AW. Engaging but inaccurate: A cross-sectional analysis of acne videos on social media from non-health care sources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):610–612. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoenberg E, Shalabi D, Wang JV, Saedi N, Keller M. Public social media consultations for dermatologic conditions: an online survey. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26(3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braunberger T, Mounessa J, Rudningen K, Dunnick CA, Dellavalle RP. Global skin diseases on Instagram hashtags. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23(5) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaliyadan FAH, Alsaqer HS. The effect of social media on treatment options for acne vulgaris. IJMDC. 2021;5(1):140–145. doi: 10.24911/IJMDC.51-1605689866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lima YVNBA, Pontello R, Júnior, Silva TMG. O impacto das mídias sociais no tratamento da acne vulgar. Surg Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;15:e20230198. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng DX, Ning AY, Levoska MA, et al. Acne and social media: A cross-sectional study of content quality on TikTok. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38(1):336–338. doi: 10.1111/pde.14471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward S, Rojek N. Acne Information on Instagram: Quality of Content and the Role of Dermatologists on Social Media. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21(3):333–335. doi: 10.36849/JDD.6411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]