Abstract

Purpose

Fabry disease is an X-linked lysosomal storage disorder that results in multi-systemic renal, cardiovascular, and neuropathological damage, including in the eyes. We evaluated anterior segment ocular abnormalities based on age, sex (male and female), and genotype (wild-type, knockout [KO] male, heterozygous [HET] female, and KO female) in a rat model of Fabry disease.

Methods

The α-Gal A KO and WT rats were divided into young (6–24 weeks), adult (25–60 weeks), and aged (61+ weeks) groups. Intraocular pressure (IOP) was measured. Eyes were clinically scored for corneal and lens opacity as well as evaluated for corneal epithelial integrity and tear break-up time (TBUT). Anterior chamber depth (ACD) and central corneal thickness (CCT) using anterior segment-optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT).

Results

The Fabry rats showed an age-dependent increase in IOP, predominantly in the male genotype. TBUT was decreased in both male and female groups with aging. Epithelial integrity was defective in KO males and HET females with age. However, it was highly compromised in KO females irrespective of age. Corneal and lens opacities were severely affected irrespective of sex or genotype in the aging Fabry rats. AS-OCT quantification of CCT and ACD also demonstrated age-dependent increases but were more pronounced in Fabry versus WT genotypes.

Conclusions

Epithelial integrity, corneal, and lens opacities worsened in Fabry rats, whereas IOP and TBUT changes were age-dependent. Similarly, CCT and ACD were age-related but more pronounced in Fabry rats, providing newer insights into the anterior segment ocular abnormalities with age, sex, and genotype in a rat model of Fabry disease.

Keywords: fabry disease, α-galactosidase A (α-Gal A), anterior segment, ocular surface cornea, lens

Fabry disease is an X-linked inborn error of glycosphingolipid metabolism caused by the gene mutation in a lysosomal exoglycohydrolase, α-galactosidase A (α-Gal A or GLA).1,2 The absence or deficiency of the α-Gal A enzyme results in the accumulation of glycosphingolipid (GSL) substrates, namely globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) and globotriaosylsphingosine (Lyso-Gb3), that trigger cellular damage and oxidative stress. This leads to renal, cardiac, gastrointestinal, and neurological dysfunction.3–5 Fabry disease is the most common lysosomal storage disease, with a prevalence of 1 in 1237 to 1 in 1334 incidences.6–8 Being an X-linked disease, male subjects are found to be more commonly affected. Those with minimal α-Gal A activity, such as knockout (KO) female subjects and KO male subjects, are seen to have a greater intensity of symptoms.9 Although the genetic incidence of carrying the single copy of the α-Gal mutation is comparable in male and female subjects, half of the female subjects do not show the symptoms or remain unidentified due to heterogeneity.10

The Mainz Severity Score Index (MSSI) and the Fabry Outcome Survey (FOS), the international databases of patients with Fabry disease, suggest that ocular abnormalities are common and often correlate with disease severity.11 Fabry disease in childhood presents with extreme pain (neuropathic),12,13 asymptomatic corneal opacities known as corneal verticillata,14,15 and angiokeratoma (vascular skin lesions)16 that often appear in late adolescence. The ocular findings in adult patients include corneal verticillata, lenticular opacities, and vascular tortuosity of the conjunctival, retinal, or choroidal vessels. In the absence of family history, these symptoms typically delay the diagnosis due to the nonspecificity of the disease, ultimately lowering the quality of life.17,18

Fabry disease is currently managed using enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) in many countries except the United States due to pending US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, which requires an intravenous infusion of agaksidase alfa (Replagal; Takeda-Shire Human Genetic Therapies, USA)19 or agaksidase beta (Fabrazyme; Sanofi, USA).20 The FDA recently approved a chaperone therapy, migalastat (Galafold; Amicus Therapeutics, USA), which is also suggested for managing patients with Fabry disease.21 Current therapies are expensive, not designed for all mutations, require multiple treatments, and even elicit severe immune side effects.22

Overall, no curative treatments are available for Fabry disease. The first patients with Fabry disease who have received gene therapy with recombinant lentivirus targeting their hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells may bring hope if safety and durability are demonstrated.23 Given the evolving treatment for Fabry disease, there is an unmet need for a better understanding of the early diagnosis of the disease, where ophthalmic examinations might play a decisive role in the identification of Fabry disease.24 An α-Gal A KO rat model was previously established that depicts several systemic-cardiac, renal, and neurological pathologies similar to those seen in human patients.25 Importantly, several ocular phenotypes of Fabry disease, including the development of corneal and lenticular opacities and the accumulation of α-galactosyl glycosphingolipids in keratocytes, lens fibers, and retinal vascular endothelial cells were observed.9 Because Fabry is a progressive X-linked disease, there is a need to further characterize the model and disease with aging. The present study was designed to comprehensively study the anterior segment ocular abnormalities in an age-dependent manner (young, adult, and aged) and its correlation to sex (male and female mice) and genotype (wild-type [WT], KO male, heterozygous [HET] female, and KO female) using multimodal clinical imaging modalities in a rat model of Fabry disease.

Methods

Animals

All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), Medical College of Wisconsin (Milwaukee, WI, USA), and were carried out in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, adhering to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. As previously reported, the Dark Agouti, DA-Glaem2Mcwi (Rat Genome Database ID # 10054398) rats were previously generated at the Medical College of Wisconsin's Transgenic Core facility using CRISPR/Cas9 technology by disrupting the rat Gla gene (GenBank accession number NM_001108820.3) from α-Gal A.25 All the animals were procured from the existing Medical College of Wisconsin rat colony. The Dark Agouti WT rats of the same strain were used as controls. The rats were initially genotyped as WT male (Gla+/0), KO male (Gla−/0), WT female (Gla+/+), HET female (Gla±), and KO female (Gla−/−). The rats were further subdivided based on their age into 3 groups: 6 to 24 weeks (young), 25 to 60 weeks (adult), and 61+ weeks (aged), as described in the Supplementary Files S1 to S7. Rats were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle and provided standard laboratory chow (Purina, diet 5001) and drinking water ad libitum.

Anesthesia

Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane in an induction chamber (VetEquip, Livermore, CA, USA) equipped with a precision vaporizer and provided with 100% oxygen at a flow rate of 0.2 to 1 L/min.

Tonometry

The intraocular pressure (IOP) was measured with an iCare TONOLAB tonometer (iCare, Raleigh, NC, USA) based on the rebound tonometry designed explicitly for rodents. Briefly, the rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and stationed on a flat surface. The disposable probe was positioned approximately 1 mm to 4 mm from the cornea at a horizontal angle of 25 degrees relative to the visual axis at the cornea apex. The IOP was measured six times per eye in sequential order and averaged in each group. IOP was measured between 9 and 11 AM to minimize diurnal variation during the day.

Slit Lamp Biomicroscopy

The cornea was examined for abnormalities, such as opacities and deposits, using a slit lamp biomicroscope (Topcon Medical Systems-SL-D8Z, Oakland, NJ, USA) equipped with a camera (Nikon D810 36.3 MP DSLR, Melville, NY, USA).26 Corneal integrity was captured using diffused illumination and an optical section. The cornea scoring was on a scale of 1 to 5 based on the severity of corneal deposits using a rubric as follows: 1 (no or few scattered deposits), 2 (<25% of honeycomb network), 3 (25–50% of honeycomb network), 4 (>50% of honeycomb network), and 5 (confluent deposits and plaques), as described previously.9

Lenticular opacity was assessed after the corneal examination. Topical eye drops containing 2.5% phenylephrine HCL and 1% tropicamide (Akorn, Lake Forest, IL, USA) were administered for pupil dilation. In brief, the scoring of 1 to 4 was assigned to the rat lens based on the development of lenticular opacities as follows: 1 = none or developmental suture; 2 = punctate opacities; 3 = central focal cataract; and 4 = halo patterns/nuclear cataract. For tear break-up time (TBUT), the rat eye was instilled with 1 drop of 1% fluorescein sodium dye. The slit lamp biomicroscope cobalt-blue filter for fluorescein excitation was engaged. The eyes were manually closed and opened by the examiner, and once the eyelids were opened, the time it took for the tear film to break was recorded. Fluorescein dye was used further to evaluate the epithelial integrity of the corneal surface. Based on the reported literature, the corneal staining was scored on a scale from 0 to 15.27 All the images were randomized and scored by at least three investigators in a masked manner.9

Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography

The central corneal thickness (CCT) and anterior chamber depth (ACD) were measured on rats using a Bioptigen Envisu R2200 spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a Gen-3 telecentric lens (12 mm). Image acquisition was performed by completing a series of volume scans (1000 A-scans/B-scans and 100 B-scans) with a 1.6126 µM axial resolution. The captured images were further processed for CCT and ACD measurements by determining the distance from the corneal epithelium to the corneal endothelium and corneal endothelium to the anterior capsule of the crystalline lens, respectively. All the measurements were performed using Bioptigen InVivoVue software (Leica Microsystems, Durham, NC, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Eye examinations were performed randomly on one eye. Data were analysed using GraphPad Prism 9 software (GraphPad, Boston, MA, USA). No statistical differences were found between the male and female WT groups, so the values were combined for statistical analysis. We performed a 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the Kruskal-Wallis test corrected for multiple analyses with Dunn's test for a single variable, such as age. Two-way ANOVA was performed using Tukey's multiple comparisons tests (95% confidence interval [CI]) to compare the groups with two variables, such as age and gender.

Results

Intraocular Pressure was Related to Age and Sex in Fabry Rats

Although ocular hemodynamics and its role in Fabry disease are not yet characterized, we measured IOP in the Fabry rat model and compared them across age, sex, and genotype. A significant difference in IOP levels was observed in aged rats (18.61 ± 0.56 mm Hg, n = 31, P < 0.05) compared to the adult group (16.72 ± 0.33 mm Hg, n = 29), as shown in Figure 1A. Young rats (16.95 ± 0.65 mm Hg, n = 21) showed no statistical differences compared to adult or aged rats. Among all age groups, female rats showed the same median IOP levels as male rats. An age-dependent increase in IOP levels was observed among the male Fabry rats between young (16.6 ± 0.70 mm Hg, n = 15) versus the adult group (17.26 ± 0.57 mm Hg, n = 19, P < 0.05) and adult rats versus the aged group (19.79 ± 0.46 mm Hg, n = 14, P < 0.05), as shown in Figure 1B. Next, we analyzed the Fabry rats based on their genotype (Fig. 1C). In the young age group, there was no significant differences in IOP of HET and KO female rats versus WT and KO male rats.

Figure 1.

Age-, sex-, and genotype-dependent changes in intraocular pressure (IOP) levels in a rat model of Fabry disease. Mean IOP was obtained in Fabry rats using a Tonolab rebound tonometer. All readings averaged the 6 values recorded between 9 and 11 AM to avoid diurnal variation during the day. (A) There was a significant increase in IOP levels in an age-dependent manner. (B) The aged male Fabry rats were observed to have higher IOP levels than the adult rats group. Similarly, the adult male rats showed a significant increase in IOP compared to the young male rats. (C) When the Fabry rats were divided based on genotypes, IOP levels showed an increasing trend in KO male rats, heterozygous (HET) female rats, and KO female rats but were not significant versus wild-type (WT). *, P < 0.05.

Tear Film Break-Up Time Decreased With Age and was Dependent on Sex and Genotype in Fabry Rats

Next, we measured TBUT to determine precorneal tear film (PTF) stability across the age, sex, and genotype of Fabry rats. A significant decrease in TBUT was observed in the adult age group (6.32 ± 0.39 seconds, n = 31, P < 0.05; Fig. 2A) compared to the young group (8.2 ± 0.60 seconds, n = 24). However, no changes were observed between the young versus the aged groups (7.17 ± 0.42 seconds, n = 28) or the adult versus the aged groups. When the rats were categorized based on their sex, they showed similar TBUT in the young group (8.2 ± 0.57 seconds, n = 15 male rats and 8.11 ± 1.34 seconds, n = 9 female rats), the adult group (6.84 ± 0.54 seconds, n = 19 male rats and 5.5 ± 0.48 seconds, n = 12 female rats), and the aged group (6.45 ± 0.56 seconds, n = 11 male rats and 7.64 ± 0.57 seconds, n = 17 female rats), except there were significantly lower TBUT values in the adult female rat group compared to the young Fabry rats group (P < 0.05; Fig. 2B). When the Fabry rats were further evaluated based on genotype, the KO male Fabry rats demonstrated significantly lower TBUT in the adult group (5.8 ± 0.55 seconds, n = 10, P < 0.05) and the aged group (5.78 ± 0.40 seconds, n = 9, P < 0.05) compared to the young KO male rats group (7.5 ± 0.78 seconds, n = 8; Fig. 2C). Similarly, the HET female rats showed significantly high TBUT values in the young age group (13.0 ± 0.58 seconds, n = 3) compared to the HET female rats in the adult group (6.4 ± 0.69 seconds, n = 5, P < 0.001). On the contrary, the WT rats showed no differences in TBUT across the different age groups.

Figure 2.

Age-, sex-, and genotype-dependent changes in tear break up time (TBUT) levels in a rat model of Fabry disease. Fabry rats showed a significant decrease in TBUT in the adult rats group compared to the young rats group (A). The bar graph represents the average mean values of TBUT for different age groups. When Fabry rats were compared based on sex irrespective of gender, the female rats in the adult rats group showed significantly low TBUT values compared to the young rats group. Further analysis comparing genotypes in Fabry rats, adult and aged KO male rats depict significantly decreased TBUT compared to the young KO male rats (C). Similarly, heterozygous (HET) female rats in the adult rats group showed significantly lower TBUT values than the young HET female rats. Data are represented as mean ± SE. *, P < 0.05; ****, P < 0.0001.

Corneal Epithelial Integrity was Reduced in Fabry Rats

Fluorescein staining of the corneal epithelium was used to evaluate the integrity in Fabry rat eyes (Fig. 3A). The staining score was significantly higher for the rats in the aged group (n = 29, P < 0.01) compared to the young rats group (n = 26; Fig. 3B). There were no differences observed between young versus adult rats (n = 34) or adult versus aged rats. Similarly, when the staining score was assessed based on sex, male KO rats in the aged group (n = 13) showed increased scores compared to the Fabry rats in the young group (n = 17, P < 0.01). In contrast, there was no significant difference in the score observed between male and female adult rats in the other age groups (Fig. 3C). Based on genotypes, the corneal integrity was reduced in the male KO rats and female HET rats. Male KO rats in the aged group (n = 10) exhibited significantly higher stain scores compared to the adult rats group (n = 11, P < 0.01) and the young rats group (n = 9, P < 0.01). On the other hand, HET female rats in the adult group (n = 6) were significantly higher than the young rats group (n = 3, P < 0.05; Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Age-, sex-, and genotype-dependent changes in corneal epithelial integrity in a rat model of Fabry disease. Fabry rats were administered 1% sodium fluorescein dye topically to the eye. The images were randomized and scored by at least three investigators in a blinded manner using cornea scoring rubrics described previously. Based on the reported literature, the scoring was given on a scale from 0 to 5.27 (A) Present the representative images of rat cornea of male and female Fabry rats in different age groups and genotypes based on the epithelial defects; the arrows point at the damage to the cornea indicated by the deposition of fluorescein stain. (B) The aged rats developed more severe corneal defects and attained a higher stain score than the young Fabry rats. (C) Sex-related differences were observed only in the aged male Fabry rats, depicting a significant increase in epithelial damage compared to the young male group. (D) The genotypic separation of Fabry rats suggests a significant increase in the KO male Fabry rats in the adult group compared to the young rats group. Similarly, the KO male rats in the aged group showed increased corneal damage compared to the adult group. On the other hand, the heterozygous (HET) adult female rats showed significantly increased corneal stain scores compared to their HET counterparts in the young group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Corneal Opacities Depend on Genotype and Increase With Age in Fabry Rats

Corneal deposits observed in patients with Fabry disease, described as cornea verticillata, are often considered highly specific for Fabry disease as the only time it is observed as an effect of a small number of medications, so the presence is pathognomonic. In the present study, eyes were analyzed based on age, sex, and genotype using slit lamp biomicroscopy, as described in our previous study.9 Corneal deposit scoring was assigned to the corneas based on the severity of these deposits observed on the slit lamp images (Fig. 4A). The corneal phenotype in Fabry rats was predominantly present on the superior surface in a honeycomb pattern, and the corneal deposits increase with age in all genotypes. The Fabry rats in the aged group (n = 28, P < 0.001) showed the highest accumulation of corneal deposits, followed by the adult rats (n = 35, P < 0.05) compared to the young rats (n = 24; Fig. 4B). When Fabry rats were analyzed based on sex, the male cohort in the aged group (n = 11) showed a significantly high corneal score compared to the adult rats group (n = 19, P < 0.05) and to the young rats group (n = 15, P < 0.01; Fig. 4C). On the contrary, there were no differences in the female Fabry rats at any age studied (young group = n = 9; adult group = 3.0 ± 0.26, n = 16; and aged group = n = 16). Comparing corneal opacity in different genotypes revealed further corneal deposits in Fabry rats (Fig. 4D). Male Fabry rats showed significantly higher corneal scores in the aged KO rats (n = 9) compared to their counterparts in the adult KO group (n = 10, P < 0.01) and the young KO male group (n = 8, P < 0.0001). A similar pattern was observed in female rats, where the cornea score was highest in KO female rats in the aged group (n = 8, P < 0.01), followed by the adult group (n = 6, P < 0.05) when compared to the young KO female rats (n = 3). Additionally, we found a significant increase in corneal opacity in the HET female rats in the aged group (n = 3, P < 0.01) versus the adult group (n = 5; see Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Age-, sex-, and genotype-dependent changes in corneal opacity in a rat model of Fabry disease. The slit lamp images were captured, and corneal opacity was scored on a scale of 1 to 5 based on the severity of corneal deposits using a cornea scoring rubric described previously.9 Briefly, a score of 1 represents no or few scattered deposits, a score of 2 represents < 25% of the honeycomb network, a score of 3 represents 25% to 50% of the honeycomb network, a score of 4 represents >50% of the honeycomb network, and a score of 5 represents confluent deposits and plaques. (A) The representative images of rat cornea slit images of male and female Fabry rats in different age groups based on the severity of corneal deposits; the arrows point at the deposits similar to cornea verticillata observed in the Fabry cornea. (B) The Fabry rats in the aged rats group developed significantly higher corneal opacities than the adult and young rats groups. (C) When compared between the sexes, the aged male rats showed significantly higher corneal scores compared to the young male rats. (D) When the Fabry rats were defined based on their genotype, the group most affected was the KO male rats, which showed significantly high corneal scores in the adult rats group and a further increase in the aged rats group. The KO female rats group also showed elevated corneal scores in the adult versus the young female rats. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001, and ****, P < 0.0001.

Central Corneal Thickness was Related to Age, Sex, and Genotype in Fabry Rats

CCT was measured in Fabry rats using anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) measurements by age, sex, and genotype (Fig. 5A). Aging does affect the CCT in Fabry rats, as there was an age-dependent increase in the thickness in the aged group (0.144 mm ± 0.002 mm, n = 29, P < 0.0001) followed by the adult age group (0.139 mm ± 0.002 mm, n = 33, P < 0.0001) when compared to the young Fabry rats (0.126 mm ± 0.002 mm, n = 28; Fig. 5B). Fabry rats analyzed based on sex revealed significantly higher CCT values in both male and female rats from the adult (0.141 mm ± 0.002 mm, n = 16 male rats and 0.138 mm ± 0.003 mm, n = 17 female rats, P < 0.01) and the aged group (0.149 mm ± 0.003 mm, n = 11 male rats and 0.14 mm ± 0.003 mm, n = 18 female rats, P < 0.0001) compared to the young Fabry rats (0.129 mm ± 0.002 mm, n = 15 male rats and 0.122 mm ± 0.004 mm, n = 13 female rats; Fig. 5C). When compared across all genotypes, the aged cohorts showed higher CCT values compared to the adult and young rat cohorts. In particular, the WT adult group (0.139 mm ± 0.003 mm, n = 11, P < 0.001) and the aged group (0.146 mm ± 0.004 mm, n = 9, P < 0.0001) have elevated CCT values when compared to the young Fabry rats (0.123 mm ± 0.004 mm, n = 13). Similarly, male KO rats showed an age-dependent increase in CCT, with maximum values observed in the aged group (0.151 mm ± 0.003 mm, n = 9, P < 0.0001), followed by the adult rats group (0.140 mm ± 0.003 mm, n = 8, P < 0.001), when compared to the young Fabry rats (0.129 mm ± 0.002 mm, n = 8). Similar results were obtained in the KO female rats, where significantly high CCT values were seen in the aged group (0.131 mm ± 0.004 mm, n = 7, P < 0.05) versus the adult group (0.147 mm ± 0.002 mm, n = 6, P < 0.05) versus the Young Fabry rats (0.131 mm ± 0.002 mm, n = 4; Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Age-, sex-, and genotype-dependent changes in central corneal thickness (CCT) in a rat model of Fabry disease. (A) Representative optical coherence tomography (OCT) images were used to measure the central corneal thickness (CCT) in Fabry rats. (B) An age-dependent increase in CCT was observed in the Fabry rats. (C) Compared among the sexes, Fabry rats displayed significantly higher CCT values in the adult rats group and the aged rats group than the young rats group. (D) When Fabry rats were compared based on genotypes, the wild-type (WT) and KO male rats had an age-dependent increase in CCT. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001, and ****, P < 0.0001.

Anterior Chamber Depth was Critically Influenced by Age, Sex, and Genotype in Fabry Rats

Similar to the results obtained with CCT values, an age-dependent increasing trend was observed for ACD values in Fabry rats (Fig. 6A). The mean ACD values in the aged rats (0.838 mm ± 0.004 mm, n = 29) were significantly higher than in the adult (0.822 mm ± 0.003 mm, n = 33, P < 0.05) and the young (0.792 mm ± 0.006 mm, n = 28, P < 0.0001) groups. In addition, the adult Fabry rats had elevated ACD values (P < 0.0001) compared to the rats in the young group (Fig. 6B). Further, the rats were analyzed for ACD measurement based on sex. It was found that the adult (0.822 mm ± 0.005 mm, n = 17, P < 0.0001) and the aged (0.837 mm ± 0.004 mm, n = 18, P < 0.0001) female rats groups exhibited significantly higher ACD values compared to the young (0.779 mm ± 0.008 mm, n = 13) female cohort of Fabry rats (Fig. 6C). A further correlation for the genotypic differences for ACD measurements revealed remarkable alterations in the ACD values in Fabry rats. The WT adult (0.831 mm ± 0.005 mm, n = 11, P < 0.001) and the aged (0.844 mm ± 0.014 mm, n = 9, P < 0.0001) rats had significantly deeper ACD than their young (0.791 mm ± 0.008 mm, n = 13) counterparts. In contrast, KO male rats showed high ACD values in the aged Fabry rats (0.84 mm ± 0.005 mm, n = 9, P < 0.01) and no change in the adult rats (0.82 mm ± 0.005 mm, n = 8) compared to the young group (0.804 mm ± 0.010 mm, n = 8). A similar result was obtained in the HET female rats, where ACD values were significantly higher in the aged group (0.843 mm ± 0.008 mm, n = 4, P < 0.05) compared to the young group (0.799 mm ± 0.007 mm, n = 3). In addition, the KO aged (0.826 mm ± 0.014 mm, n = 7, P < 0.001) and the adult (0.830 mm ± 0.003 mm, n = 6, P < 0.001) female rats showed higher ACD values compared to their respective young cohorts (0.767 mm ± 0.001 mm, n = 4; Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

Age-, sex-, and genotype-dependent changes in the anterior chamber depth (ACD) in a rat model of Fabry disease. (A) Representative optical coherence tomography (OCT) images were used to measure the anterior chamber depth (ACD) in Fabry rats. (B) An age-dependent increase in ACD was observed in the Fabry rats. (C) Compared between the sexes, the aged male and female rats displayed significantly higher ACD values in the adult and aged groups than the young rats group (adult group; and n = 11 male rats and n = 18 female rats to the aged rats group). (D) When Fabry rats were compared based on genotypes, the wild-type (WT), KO male rats, heterozygous (HET) female rats, and KO female rats, all had an age-dependent increase in ACD values. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001, and ****, P < 0.0001.

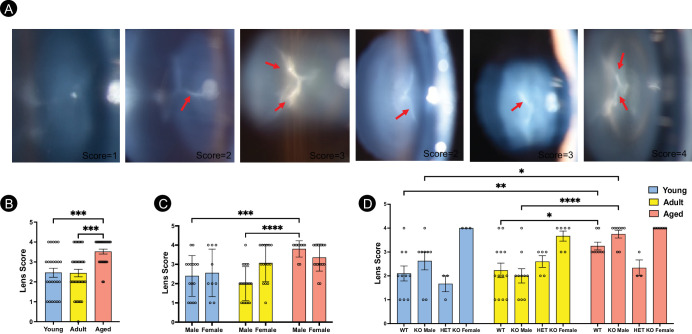

Lenticular Opacities Were Predominantly Observed in Male Fabry Rats

Because cataracts are considered one of the clinical ocular manifestations of Fabry disease, the lens opacity was characterized in the Fabry rat model based on age, sex, and genotype (Fig. 7A). The severity of the lenticular opacity was observed to be age-dependent with aged Fabry rats with the highest score (n = 27, P < 0.001 compared to the adult group (n = 34) and the young rats (n = 24; Fig. 7B). When the rats were assessed based on their sex, the aged male rats group (n = 10) had a higher score compared to the adult group (n = 19, P < 0.0001) and the young rats group (n = 15, P < 0.001). In contrast, no change in lens score was observed in any age group of the female Fabry rats (n = 9 young, n = 15 adult, and n = 17 aged; Fig. 7C). The genotype of Fabry rats was further analyzed for the lens score. Most importantly, the male rats of both the genotypes (WT and KO) were found to be predominantly affected in an age-dependent manner (Fig. 7D). The aged WT group (n = 8) displayed a significantly higher lens score compared to the adult (n = 13, P < 0.05) or young Fabry rats (n = 10, P < 0.01). Similarly, the KO male rats in the aged group (n = 8) showed elevated lens scores versus the adult group (n = 10, P < 0.0001) or the young group (n = 8, P < 0.05). In contrast, female KO Fabry rats show consistently high lenticular scores, although not affected by age, whereas female HET Fabry rats were unaffected (see Fig. 7D).

Figure 7.

Age-, sex-, and genotype-dependent changes on lenticular opacity in a rat model of Fabry disease. (A) Representative images of the lens examined using the slit lamp showed varying levels of lenticular opacities in the Fabry rat lens. The arrows indicate lenticular opacities, scored and assessed in a rubric based on the severity described previously.31 A lens score of 1 represents none or developmental suture, a lens score of 2 represents some puncta, a lens score of 3 means central focal cataract, and a lens score of 4 represents nuclear cataract and halo pattern. (B) A significant increase in the lens score was observed in an age-dependent manner in the Fabry rats. (C) When analyzed based on sex, the aged male rats showed a significant increase in lens score compared to the adult and young rats groups. (D) There were significant differences in the lens score in various genotypes of the Fabry rats. Wild-type (WT) Fabry rats showed increased lenticular opacity based on age. Similarly, there was an increased lens score in the KO males in an age-dependent manner. On the other hand, KO female rats showed high lenticular opacities overall, regardless of age. The mean score of individual age groups was compared using 1-way ANOVA, and 2-way ANOVA was performed comparing the gender versus age and genotype versus age datasets. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001, and ****, P < 0.0001.

Discussion

Ocular manifestations in patients with Fabry disease are predominantly considered limited to corneal verticillata for diagnosis. Early detection improves the patient's quality of life with prompt treatment. However, the role of this and other ocular manifestations, primarily related to the progressive nature and sex dependence of Fabry disease pathology, is meager. Recent work suggests vascular anomalies and corneal/lens opacifications are the ocular indicators of Fabry disease.28–30 Additionally, conjunctival vascular aneurysms, corneal or retinal vessel tortuosity, and lenticular opacities were also reported in the patients with Fabry disease.15,31,32 However, these sporadic studies do not highlight the significance of age, sex, or genotype in this X-linked lysosomal storage disease, making a more extensive population study difficult, particularly in female subjects who are heterozygous with variable phenotypic expression due to X-chromosome inactivation.

In 2018, Miller et al.25 developed an α-Gal A KO rat model of Fabry disease using CRISPR/Cas9 technology at the Medical College of Wisconsin to investigate systemic abnormalities further and advance our understanding of Fabry disease pathophysiology. Their research recapitulated the progression of Fabry disease in the rat, namely neuropathic pain, vascular disease, and the indiscriminate presence of α-galactosyl glycosphingolipids in both the cornea and lens. Until then, mouse models had not been known to demonstrate ocular pathology,33,34 giving a significant advantage to the Fabry rat model. Since then, the model revealed abnormalities in Fabry disease-induced anterior and posterior segments of the rat eye. Ocular findings were notable, not only for cornea verticillata but for Fabry cataracts and anterior lens damage. Building upon our previous report,9 this study provides a more comprehensive depiction of corneal and lenticular opacities through additional clinical indicators of IOP, TBUT, corneal epithelial integrity, CCT, and ACD.

The age-dependent increase in IOP might be due to several factors, such as aqueous humor dynamics and blood volume.35 The trabecular meshwork (TM) plays a vital role in the passage of aqueous humor, and the elasticity of TM decreases with age. At older ages, the drainage capacity of aqueous humor through the pores decreases due to the thickening of elastic fibers and increased extracellular matrix of the TM, leading to increased resistance of aqueous outflow through the pores, leading to increased IOP. In addition to the physiology of the aqueous humor, the blood volume that flows through the retinal, choroidal arteries, and veins also has a role in fluctuating the IOP levels.36 Although IOP has been greatly overlooked in Fabry disease,37 international Fabry registries indicate that 57% to 67% of patients develop hypertension associated with renal dysfunction.38 Previous studies suggest that hypertension could increase aqueous humor production due to elevated ciliary blood flow and capillary pressure, and aqueous outflow may be decreased due to increased episcleral venous pressure,38 suggesting decreased outflow and IOP increase with age. Another possibility of increased IOP could be due to the increase in CCT. The age dependent increase in CCT affects the anterior chamber volume by the movement of posterior corneal endothelial surface, thus affecting the IOP levels.39 In the present study, there was a significant increase in IOP with age in the male Fabry rats (Gla+/0 and Gla−/0) and not in female rats, suggesting male rats are more susceptible to damage in aqueous humor dynamics owing to the sex-dependent and X-linked nature of Fabry disease. A rising IOP indicates a fluid build-up in the anterior chamber due to possible outflow obstruction in the TM by GLA substrate deposits distally or due to age-dependent increase in CCT. As a result, constant exertion of pressure could put patients with Fabry disease at a higher risk of irreparable damage to the optic nerve. Further study on the risk of glaucoma in patients with Fabry disease would be beneficial to help inform if screening for glaucoma should be part of their multidisciplinary care.

The precorneal tear film (PTF) overlays on the exposed surfaces of the cornea and bulbar conjunctiva, providing lubrication for the cornea and conjunctiva. It facilitates solute exchange, contributes to antimicrobial defense, and is a medium to remove debris from the ocular surface.40 The TBUT measures PTF integrity that may contribute to dry eye syndrome (DES). Despite its applicability to the clinic, this correlation has yet to be well elucidated in patients with Fabry disease. Here, we found that adult or aged Fabry rats, predominantly KO male (Gla−/0) and HET female (Gla−/+) rats, exhibited significantly decreased TBUT older than 25 weeks of age. The decreased TBUT hints that the degenerative nature of tear quality is linked to pathological progression in patients with Fabry disease. A previous case study41 found progressively worsening vision, stinging and burning of the eyes, and occasional foreign body sensation in patients with Fabry disease. Further evaluation in our rat model revealed a DES consistent with Fabry disease, with the mechanisms still under question. One of the explanations for decreased corneal epithelial integrity may be autonomic impairment, causing decreased tears and saliva formation because of the classical lysosomal dysfunction noted in Fabry disease.15,42

Corneal opacities, often clinically described as cornea verticillata in patients with Fabry disease, are one of the most prevalent ocular symptoms found in the rat model of Fabry disease.9 The corneal epithelium and surrounding anterior stroma are home to these whorl-shaped, linear opacities in the inferior region of the cornea.43 These modifications in the cornea, nevertheless, have been a central aspect in recent studies on the eyes and served as one of the best early diagnostic tools for detecting Fabry disease because it is so specific to the disease and pathognomonic in the absence of an offending medication. Given the consequences of corneal deposits, a compromise in the integrity of epithelial cells can imply deterioration of the cellular processes that support ocular structures in the anterior segment of the eye. In the present study, corneal fluorescein staining, which highlighted areas of epithelial disruption, was increased with age in Fabry rats. Corneal deposits were also conspicuous in aged rats, especially among KO male rats (Gla−/0), HET females (Gla−/+), and KO females (Gla−/−) rats. It has been extensively documented that a loss of function of the Gla gene makes male patients with Fabry disease more susceptible and confers a buildup of glycosphingolipid, which lends itself to the progression of vascular, corneal, and lens aberrations found in the Fabry rats. Additional toxic substrates, such as globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) and globotriaosylsphingosine (Lyso-Gb3), can be related to the severity of symptoms; an increased amount has been discovered in Gla KO models.44 The buildup of these substrates can be present in different ways, such as in the clinical condition of cornea verticillata or vortex keratopathy. Without other significant systemic symptoms, cornea verticillata is a highly specific and sensitive finding for Fabry disease; hence, its presence in a patient is clinically essential when making a diagnosis. Its rarity in healthy individuals underscores its importance in assessing pathology. This finding can often be the sole indication of Fabry disease, yet the extent of its development has not been demonstrated as a predictor of disease severity.

Next, we measured CCT and ACD in Fabry rats using AS-OCT as two additional indicators of ocular anomalies in disease pathology. We observed that aged male and female rats had an overwhelmingly increased CCT post-young age (>25 weeks old) across genotypes but were most predominantly noticed in KO female (Gla−/−) and KO male (Gla−/0) rats. Similarly, ACD differences were prominent in older rats compared to the young ones, highlighting the age-dependent contribution of glycosphingolipid deposits to the pathological findings in Fabry rats. Prior studies have alluded to similar results, with Miller and colleagues positing that Gb3 accumulation will lead to downstream dysfunction and injury of cells.9

Lens opacities are also widely demonstrated in patients with Fabry disease, more frequently in male patients than in female patients in their second decade of life.31,43 Similarly, male rats developed more lens opacities than WT rats in the present study. The affected male cohorts were almost exclusively found in older age due to the deposition of Gb3 and related α-galactosyl glycosphingolipids contributing to the opacification of the lens, primarily via dysfunction of epithelial cells and impaired oxidation of lenticular lipids. Lens opacities on the posterior lens have been previously documented, but an excessive accumulation is thought to be rare even in Fabry individuals. A study in 2016 determined that the development of lens opacities often denotes extensive systemic and pathological involvement.44 Hence, patients presenting with Fabry disease with cataracts frequently have manifestations of other systemic pathologies.

On average, patients with Fabry disease consult 10 specialists before receiving a correct diagnosis. Identifying initial signs is imperative in curbing systemic involvement and symptom severity. The results of the present study indicate increased severity of ocular abnormalities in KO male rats (Gla−/0) and aged Fabry rats. Furthermore, all rats became ocular manifestations over time, with aging and sex being some of the determinants in the advancement of Fabry symptoms. The findings advance our knowledge and expand our understanding of this X-linked lysosomal storage disease by demonstrating the cumulative effects of age, sex, and genotype-dependent ocular manifestation in the anterior segment of the eyes. Our study describes several anterior segment ocular manifestations of Fabry disease in a rat animal model and how they may change with sex, gender, and genotype. In addition, we demonstrated increasing IOP in our rats, which is a significant risk factor for glaucoma and may warrant further study in human patients. Early diagnosis can slow progression with ERT and chaperone therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH)/National Eye Institute (NEI), Bethesda, Maryland, grant number R01EY030077 to S.S.C.

Disclosure: M.E. Erdman, None; S. Ch, None; A. Mohiuddin, None; K. Al-Kirwi, None; M.R. Rasper, None; S. Sokupa, None; S.W.Y. Low, None; C.M.B. Skumatz, None; V. De Stefano, None; I.S. Kassem, Novartis Biomedical Research (E), none of the work in this manuscript is related to her job; S.S. Chaurasia, None

References

- 1. Zarate YA, Hopkin RJ.. Fabry's disease. Lancet. 2008; 372: 1427–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Germain DP. Fabry disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010; 5: 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kint JA. The enzyme defect in Fabry's disease. Nature. 1970; 227: 1173–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brady RO, Gal AE, Bradley RM, Martensson E, Warshaw AL, Laster L.. Enzymatic defect in Fabry's disease. N Engl J Med. 1967; 276: 1163–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sweeley CC, Klionsky B.. Fabry's disease: classification as a sphingolipidosis and partial characterization of a novel glycolipid. J Biol Chem. 1963; 238: PC3148–PC3150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hopkins PV, Campbell C, Klug T, Rogers S, Raburn-Miller J, Kiesling J.. Lysosomal storage disorder screening implementation: findings from the first six months of full population pilot testing in Missouri. J Pediatr. 2015; 166: 172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matern D, Gavrilov D, Oglesbee D, Raymond K, Rinaldo P, Tortorelli S.. Newborn screening for lysosomal storage disorders. Semin Perinatol. 2015; 39: 206–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burton BK, Charrow J, Hoganson GE, et al.. Newborn screening for lysosomal storage disorders in Illinois: the initial 15-month experience. J Pediatr. 2017; 190: 130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miller JJ, Aoki K, Reid CA, Tiemeyer M, Dahms NM, Kassem IS.. Rats deficient in α-galactosidase A develop ocular manifestations of Fabry disease. Scientific Reports. 2019; 9: 9392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mehta A, Ricci R, Widmer U, et al.. Fabry disease defined: baseline clinical manifestations of 366 patients in the Fabry Outcome Survey. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004; 34: 236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pitz S, Kalkum G, Arash L, et al.. Ocular signs correlate well with disease severity and genotype in Fabry disease. PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0120814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Attal N, Bouhassira D.. Mechanisms of pain in peripheral neuropathy. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1999; 100: 12–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schiffmann R. Fabry disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2009; 122: 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Macrae WG, Ghosh M, McCulloch C.. Corneal changes in Fabry's disease: a clinico-pathologic case report of a heterozygote. Ophthalmic Paediatr Genet. 1985; 5: 185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nguyen TT, Gin T, Nicholls K, Low M, Galanos J, Crawford A.. Ophthalmological manifestations of Fabry disease: a survey of patients at the Royal Melbourne Fabry Disease Treatment Centre. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005; 33: 164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hashimoto K, Gross BG, Lever WF.. Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (FABRY). J Invest Dermatol. 1965; 44: 119–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Branton MH, Schiffmann R, Sabnis SG, et al.. Natural history of Fabry renal disease: influence of α-galactosidase A activity and genetic mutations on clinical course. Medicine (Baltimore). 2002; 81: 122–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rolfs A, Bottcher T, Zschiesche M, et al.. Prevalence of Fabry disease in patients with cryptogenic stroke: a prospective study. Lancet. 2005; 366: 1794–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schiffmann R, Kopp JB, Austin HA 3rd, et al.. Enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001; 285: 2743–2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eng CM, Guffon N, Wilcox WR, et al.. Safety and efficacy of recombinant human alpha-galactosidase A replacement therapy in Fabry's disease. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345: 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McCafferty EH, Scott LJ.. Migalastat: a review in Fabry disease. Drugs. 2019; 79: 543–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rombach SM, Smid BE, Bouwman MG, Linthorst GE, Dijkgraaf MGW, Hollak CEM.. Long term enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease: effectiveness on kidney, heart and brain. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013; 8: 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Domm JM, Wootton SK, Medin JA, West ML.. Gene therapy for Fabry disease: progress, challenges, and outlooks on gene-editing. Mol Genet Metab. 2021; 134: 117–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miller JJ, Kanack AJ, Dahms NM.. Progress in the understanding and treatment of Fabry disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2020; 1864: 129437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miller JJ, Aoki K, Moehring F, et al.. Neuropathic pain in a Fabry disease rat model. JCI Insight. 2018; 3: e99171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gupta S, Buyank F, Sinha NR, et al.. Decorin regulates collagen fibrillogenesis during corneal wound healing in mouse in vivo. Exp Eye Res. 2022; 216: 108933. PMC8885890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Amparo F, Wang H, Yin J, Marmalidou A, Dana R.. Evaluating corneal fluorescein staining using a novel automated method. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017; 58: Bio168–Bio173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Spaeth GL, Frost P. Fabry's Disease: its ocular manifestations. Arch Ophthalmol. 1965; 74: 760–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Orssaud C, Dufier JL, Germain DP.. Ocular manifestations in Fabry disease: a survey of 32 hemizygous male patients. Ophthalmic Genet. 2003; 24: 129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Samiy N. Ocular features of Fabry disease: diagnosis of a treatable life-threatening disorder. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008; 53: 416–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tsutsumi A, Uchida Y, Kanai T, Tsutsumi O, Satoh K, Sakamoto S.. Corneal findings in a foetus with Fabry's disease. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1984; 62: 923–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kurschat CE. Fabry disease-what cardiologists can learn from the nephrologist: a narrative review. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2021; 11: 672–682. PMC8102258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ohshima T, Schiffmann R, Murray GJ, et al.. Aging accentuates and bone marrow transplantation ameliorates metabolic defects in Fabry disease mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999; 96: 6423–6427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ohshima T, Murray GJ, Swaim WD, et al.. α-Galactosidase A deficient mice: a model of Fabry disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997; 94: 2540–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen Z, Sun J, Li M, et al.. Effect of age on the morphologies of the human Schlemm's canal and trabecular meshwork measured with swept‑source optical coherence tomography. Eye. 2018; 32: 1621–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Murgatroyd H, Bembridge J.. Intraocular pressure. Contin Educ Anaesthesia Crit Care Pain. 2008; 8: 100–103. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wasielica-Poslednik J, Politino G, Schmidtmann I, et al. Influence of corneal opacity on intraocular pressure assessment in patients with lysosomal storage diseases. PLoS One. 2017; 12: e0168698. PMC5230782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Levine RM, Yang A, Brahma V, Martone JF.. Management of blood pressure in patients with glaucoma. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2017; 19: 109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Doughty MJ, Zaman ML.. Human corneal thickness and its impact on intraocular pressure measures: a review and meta-analysis approach. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000; 44: 367–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cho P. Stability of the precorneal tear film: a review. Clin Exp Optom. 1991; 74: 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Klein P. Ocular manifestations of Fabry's disease. J Am Optom Assoc. 1986; 57: 672–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sodi A, Ioannidis AS, Mehta A, Davey C, Beck M, Pitz S.. Ocular manifestations of Fabry's disease: data from the Fabry Outcome Survey. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007; 91: 210–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tuttolomondo A, Simonetta I, Riolo R, et al.. Pathogenesis and molecular mechanisms of Anderson–Fabry disease and possible new molecular addressed therapeutic strategies. Int J Molec Sci. 2021; 22: 10088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kalkum G, Pitz S, Karabul N, et al.. Paediatric Fabry disease: prognostic significance of ocular changes for disease severity. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016; 16: 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.