ABSTRACT

The bacteriophages of Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus) play a key role in population shaping, genetic transfer, and virulence of this bacterial pathogen. Lytic phages like A25 can alter population distributions through elimination of susceptible serotypes but also serve as key mediators for genetic transfer of virulence genes and antibiotic resistance via generalized transduction. The sequencing of multiple S. pyogenes genomes has uncovered a large and diverse population of endogenous prophages that are vectors for toxins and other virulence factors and occupy multiple attachment sites in the bacterial genomes. Some of these sites for integration appear to have the potential to alter the bacterial phenotype through gene disruption. Remarkably, the phage-like chromosomal islands (SpyCI), which share many characteristics with endogenous prophages, have evolved to mediate a growth-dependent mutator phenotype while acting as global transcriptional regulators. The diverse population of prophages appears to share a large pool of genetic modules that promotes novel combinations that may help disseminate virulence factors to different subpopulations of S. pyogenes. The study of the bacteriophages of this pathogen, both lytic and lysogenic, will continue to be an important endeavor for our understanding of how S. pyogenes continues to be a significant cause of human disease.

OVERVIEW

The year 2015 was the centenary of the discovery of bacteriophages (phages) by Frederick Twort (1), and the first associations of phages with Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus) were made by Cantacuzene and Boncieu in 1926 (2) and by Frobisher and Brown in 1927 (3), both groups showing that the “scarlatina toxin” (erythrogenic toxin, pyrogenic exotoxin A) could be passed to a new strain after exposure to a sterile filtrate from a toxigenic isolate. Additional studies by Evans in the 1930s and 1940s documented the prevalence of group A streptococcal phages, linked them with virulence, and provided early additional evidence for lysogeny (4–8). More studies followed of both lysogenic and lytic streptococcal phages (9–15), but the link between lysogeny and the transmission of the erythrogenic toxin was not made until the landmark study by Zabriskie in 1964 (16); the phage-encoded toxin structural gene (speA) was subsequently identified by Weeks and Ferretti (17, 18) and independently by Johnson and Schlievert (19). The history and contributions of these and other early workers to our knowledge of the bacteriophages of S. pyogenes are covered elsewhere (20). Following these studies, a significant body of research has shown that phages contribute to the success and virulence of their host streptococci by acting as vectors for genes encoding virulence factors and through their ability to disseminate streptococcal genes from one cell to another through transduction. Since group A streptococci are not thought to be normally competent for transformation, except possibly under certain conditions (21), and since Hfr-type conjugal transfer of chromosomal genes has not been observed, it is easy to argue that the bacteriophages of S. pyogenes play a major role in the genetics and molecular biology of this pathogen.

LYTIC PHAGES OF GROUP A STREPTOCOCCI

Biology and Distribution of Lytic Phages

Bacteriophages typically may be grouped by their life cycle into two categories: lytic phages and lysogenic (temperate) phages. Lytic phages infect their host cell and begin the viral replicative cycle within a short time frame. At the end of replication and assembly, the host bacterial cell typically lyses and releases the newly formed bacteriophage particles. The five decades following the discovery of phages saw numerous investigations of lytic phages of S. pyogenes, which included studies of their host range, their basic biology, and their ability to mediate general transduction. In contrast to lysogenic phages, lytic phages do not alter the phenotype of the host streptococcal cell by a long-term genetic relationship, but they can shape the host population by eliminating susceptible cells in a population or by facilitating genetic exchange by transduction.

Bacteriophage A25

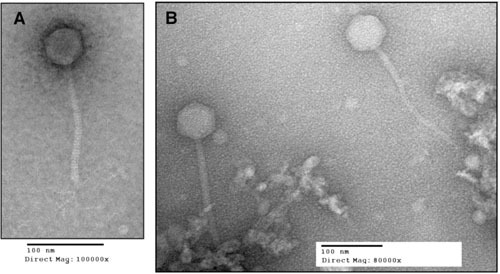

The best-studied lytic phage of S. pyogenes is bacteriophage A25, which was originally isolated in the early 1950s from Paris sewage (11, 12) and was found to mediate generalized transduction in S. pyogenes (22). Phage A25 is also referred to in the literature as phage 12204, its designation by the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC 12204). The genome sequence of A25 has been determined to be 33,900 bp with a GC content of 38.44%, very close to the predicted size (23) and GC content (24) reported previously. The sequence is available from GenBank (accession no. KT388093.1). Electron microscopy shows that it belongs to the Siphoviridae with an isometric, octahedral head measuring 58 to 60 nm across and a long flexible tail that measures 180 to 190 nm in length and 10 nm in diameter (25, 26). The tail of this phage is composed of 8-nm circular subunits and terminates in a transverse plate with a single projecting spike that is about 20 nm long (26, 27). In contrast to many lysogenic phages, the genome sequence shows that A25 does not encode a hyaluronidase (hyaluronate lyase) as part of its tail fiber. It does, however, encode a lysin that has activity against groups A, C, G, and H streptococci (28).

One-step growth experiments showed that phage A25 has an average burst size that may vary depending upon the host strain, with reported average burst sizes of 30 PFU/cell when propagated with strain K56 (29) and 12 CFU/cell using strain T253 (30). Peptidoglycan is the cell receptor for A25, and treatment of the cells with the group C streptococcus phage C1 lysin (PlyC) destroyed the receptor binding (31). Phage A25 has a broad host range, being adaptable to group G streptococci after passage (31). This broad host range is reflected by the mosaic nature of the A25 genome, which contains genetic modules shared with bacteriophages from S. pyogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus suis, Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, Streptococcus iniae, and Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus (32). Wannamaker and coworkers showed that A25 also could infect 48% of group C strains tested (33). Other S. pyogenes lytic phages in the same study could also infect group C strains at frequencies ranging from 34 to 47%. The possibility that A25 and other lytic S. pyogenes phages can infect multiple species of streptococci may contribute to horizontal transfer of both host and prophage genes via transduction. Phylogenetic analysis of the terminase suggests that A25 uses pac style packaging of its genome (32), and low-stringency pac site recognition has been associated with high-frequency transduction in phages (34). The efficiency of transduction by A25, discussed below, suggests that its packaging of DNA sequences is not highly stringent.

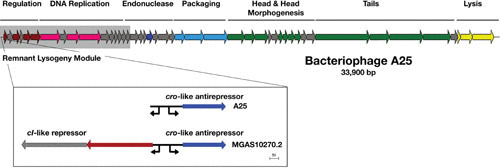

The genome sequence of A25 revealed that, remarkably, this bacteriophage was very likely an escaped lysogen containing a remnant lysogeny module that retained a cro-like antirepressor and operator sequence but no longer contained a cI-like repressor or integrase (32). The genome has a modular genetic arrangement similar to many S. pyogenes genome prophages (Fig. 1) with regions associated with regulation, DNA replication, endonucleolytic cleavage, DNA packaging, head and head morphogenesis genes, tail genes, and lysis. In contrast to most genome prophages, however, no identifiable virulence genes were found. An extended region of high DNA homology with the lysogeny module of a number of genome prophages is present (shaded gray in Fig. 1), and the shared operator sequence between these prophages and A25 appears to be a mechanism of A25 resistance for these prophages, allowing their Lambda-like repressor proteins to silence A25 expression and abort its replication. The key role of this repressor was confirmed by transferring a plasmid-encoded copy of this gene into susceptible strains of S. pyogenes, leading to high-level resistance to A25 infection (32). The remainder of the A25 genome shows little homology to known S. pyogenes prophages, instead having regions of homology to phages from other streptococcal species as described above. Streptococcal phage Str01, sequenced after A25, showed near identical homology to the A25 genome except for the presence of a cI-like repressor and integrase gene. Interestingly, homology to this portion of the Str01 genome was found to prophages from group G streptococci. This suggests that lysogenic escape was a more distant event then rescued by the acquisition of integrase and cI-like repressor from a group G streptococcal phage, further implicating multispecies genetic transfer within streptococci and streptococcal phages.

FIGURE 1.

The genome of bacteriophage A25 reveals an escape from lysogeny. The 33,900-bp generalized transducing phage A25 is shown. The portion of the chromosome included in the shaded box is the high homology region that contains the remnant lysogeny module and other genes that A25 shares with prophages from genome strains MGAS10270 (M2), MGAS315 (M3), MGAS10570 (M4), and STAB902 (M4). Unlike these complete lysogens, A25 only has the operator and antirepressor from the lysogeny module (shown in expanded view below the map), apparently having lost the integrase and repressor for lysogeny some time in the past. This A25 expanded region is compared to the homologous region from genome prophage MGAS10270.2, which contains these elements as well as the upstream genes including the cI-like repressor. Promoters are shown as directional arrows. Introduction of the MGAS10270.2 repressor into an A25-sensitive S. pyogenes strain results in its conversion to a high level of A25 resistance (32). The genome follows a typical modular arrangement, with the predicted function for A25 genes indicated by color: regulation, dark red; DNA replication, pink; encode endonucleases, dark blue; genome packaging, light blue; structural, green; and lysis, yellow. The figure is redrawn from McCullor et al. (32).

Transduction in S. pyogenes

Transformation, conjugation, and transduction are common means of genetic exchange in bacteria. In S. pyogenes, natural transformation may occur when the cells live in a biofilm (35), but such exchange has not been seen under typical laboratory conditions. Conjugative transposons are frequent elements in S. pyogenes, but they are not associated with transfer events seen with the F plasmid of E. coli. Generalized transduction, by contrast, occurs in S. pyogenes and is mediated by both lytic and lysogenic phages.

Transduction in S. pyogenes was first reported in 1968, detailing how five phages, three lytic and two lysogenic, were able to transduce streptomycin resistance (22). Of this group of phages, phage A25 (phage 12204) was able to transduce antibiotic resistance at the highest frequency (1 × 10–6 transductants per PFU). Transfer was DNase resistant but sensitive to antiphage serum, supporting generalized transduction as the mechanism of genetic exchange. The capsule of S. pyogenes is composed of hyaluronic acid, which was found to be a barrier to A25 infection (11). Lysogenic phages often encode a hyaluronidase, but phage A25 lacks such a gene since this enzymatic activity has not been associated with nor was a gene identified by genome sequencing (32). The state of S. pyogenes encapsulation can vary during the growth phase (36), and some strains, such as the recently described M4 isolate from Australia (37), do not express capsule at all. Therefore, the susceptibility of cells to phage-mediated transduction probably varies by growth state and genetic background, both of which could influence horizontal transfer.

A number of strategies have been used to improve transduction frequencies. Malke showed that transduction frequencies could be improved by using specific A25 antiserum to block unabsorbed or progeny phages from infecting transductants resulting from the initial adsorption (38). In theory, this phenomenon leading to higher transduction frequencies can occur in nature, particularly with infections of strains containing resident prophages with high homology to A25 within the lambda-type regulatory region. As discussed above, superinfection immunity represses A25 gene expression but does not impede initial phage adsorption and injection of DNA material. This mechanism protects the infected cell from lysis by A25 infection and allows for survival of transduced cells. Increased levels could also be obtained by the use of temperature-sensitive mutants of phage A25 (29), as could UV irradiation of transducing lysates prior to adsorption to the host streptococci (38–40).

Lysogenic bacteriophages of S. pyogenes are capable of mediating transfer of antibiotic resistance by transduction. Strains with bacteriophage T12-like prophages can produce transducing lysates capable of transferring resistance to tetracycline, chloramphenicol, macrolides, lincomycin, and clindamycin following lysogen induction. Generalized transduction transfer of erythromycin and streptomycin resistance following mitomycin C treatment of endogenous prophages has also been observed (41).

Transduction may play a role in the dissemination of genes among related streptococcal species. Some bacteriophages isolated from groups A and G streptococci can infect serotype A, C, G, H, and L strains; some were capable of infecting multiple serotypes (42). The same study showed that phage A25 could transduce streptomycin resistance to a group G strain. Wannamaker and coworkers further showed that streptomycin resistance could be transferred to S. pyogenes strains by a temperate transducing phage isolated from group C streptococcus (33). The wealth of S. pyogenes genome data supports the idea that horizontal gene transfer has been important in the evolution of this pathogen (43), and transduction is assumed to play an important role in this process. However, the molecular mechanisms that would drive this process are little understood. The majority of the studies into streptococcal transduction were done before the advent of modern techniques of molecular biology and genomics, and therefore this may be an opportune time to reexamine this phenomenon. A better understanding of streptococcal transduction may prove key to understanding the flow of genetic information in natural populations of S. pyogenes and the horizontal transfer of information from other genera. In addition, better understanding of gene transfer mediated by phage transduction could translate to better molecular tools for manipulation of S. pyogenes genomes, which currently remains a more challenging feat compared to other streptococcal species. More efficient genetic manipulation, in turn, could further our understanding of gene function within S. pyogenes.

LYSOGENIC PHAGES OF GROUP A STREPTOCOCCI

Genome Prophages, their Distribution, and Attachment Sites

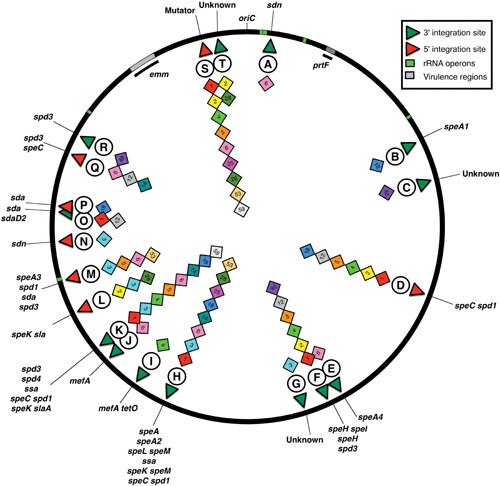

Lysogenic bacteriophages are defined by their ability to integrate their DNA into the host bacterium’s chromosome via site-specific recombination, becoming a stable genetic element that can be passed to daughter cells following cell division. Studies from the pregenomics era suggested that lysogeny was common in S. pyogenes (9, 10, 44–47), but it was genome sequencing, starting with the first sequence completed and confirmed by almost every subsequent sequenced genome, that demonstrated that toxin-carrying prophages were not only common but prominent genetic features that shaped the fundamental biology of this bacterial pathogen (Table 1). The number of lambdoid prophages or phage-like chromosomal islands found in a given genome strain has ranged from a low of one (MGAS15252) to as many as eight (MGAS10394), with three to four elements being common. These prophages are found integrated into multiple sites on the S. pyogenes genome, being found in each quadrant (Fig. 2 and Table 2). The majority of the genome prophages (72%) are found integrated into genes encoded on the lagging strand (relative to oriC). No prophages have been found to target genes in the hypervariable regions that include the M-protein (emm) or the streptococcal pilus. Some sites are frequent targets for prophage integration; the genes for DNA binding protein HU, transfer messenger RNA (tmRNA), and DNA mismatch repair (MMR) protein MutL are commonly occupied by a prophage or prophage-like chromosomal island.

TABLE 1.

Assembled and annotated genomes of S. pyogenes that are hosts to prophages

| Strain | M type | Prophages (CI)a | Origin | Diseaseb | Genome size (bp) | Accession no. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF370 | M1 | 3 (1) | USA | Wound | 1,852,441 | NC_002737 | 113 |

| MGAS5005 | M1 | 3 | Canada | Invasive (CSF) | 1,838,554 | NC_007297 | 114 |

| M1 476 | M1 | 3 | Japan | STSS | 1,831,128 | NC_020540.2 | 115 |

| A20 | M1 | 3 | Taiwan | Necrotizing fasciitis | 1,837,281 | NC_018936.1 | 116 |

| MGAS10270 | M2 | 4 (1) | USA | Pharyngitis | 1,928,252 | NC_008022 | 117 |

| MGAS315 | M3 | 6 | USA | STSS | 1,900,521 | NC_004070 | 118 |

| SSI-1 | M3 | 6 | Japan | STSS | 1,894,275 | NC_004606 | 119 |

| MGAS10750 | M4 | 3 (1) | USA | Pharyngitis | 1,937,111 | NC_008024 | 117 |

| Manfredo | M5 | 4 (1) | USA | ARF | 1,841,271 | NC_009332 | 120 |

| MGAS10394 | M6 | 7 (1) | USA | Pharyngitis | 1,899,877 | NC_006086 | 118 |

| MGAS2096 | M12 | 2 | Trinidad | AGN | 1,860,355 | NC_008023 | 117 |

| MGAS9429 | M12 | 3 | USA | Pharyngitis | 1,836,467 | NC_008021 | 117 |

| HKU16 | M12 | 3 | Hong Kong | Scarlet fever | 1,908,100 | AFRY00000001 | 121 |

| HSC5 | M14 | 3 | USA | Not known | 1,818,351 | NC_021807.1 | 122 |

| MGAS8232 | M18 | 5 | USA | ARF | 1,895,017 | NC_003485 | 123 |

| M23ND | M23 | 4 | USA | Invasive | 1,846,477 | CP008695 | 109 |

| MGAS6180 | M28 | 2 (2) | USA | Puerperal sepsis | 1,897,573 | NC_007296 | 124 |

| NZ131 | M49 | 3 | New Zealand | AGN | 1,815,785 | NC_011375 | 125 |

| Alab49 | M53 | 3 (1) | USA | Impetigo | 1,827,308 | NC_017596 | 126 |

| MGAS15252 | M59 | 0 (1) | Canada | SSTI | 1,750,832 | NC_017040 | 127 |

| MGAS1882 | M59 | 1 (1) | USA | AGN, pyoderma | 1,781,029 | NC_017053 | 127 |

Number of lambdoid prophages (number of phage-like chromosomal islands [CIs]).

AGN, acute glomerulonephritis; ARF, acute rheumatic fever; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; SSTI, skin or soft tissue infection; STSS, streptococcal toxic shock syndrome.

FIGURE 2.

Prophage attachment sites in the S. pyogenes genome. The locations of the genome prophages are shown as a generalized chromosome backbone based on the SF370 M1 genome; each diamond represents a genome prophage identified at that site. The M type of the host for each prophage is indicated by the number within the diamond, and the circled letter is the identifier linked to Table 2 for attB gene identification, the integration target within that gene (5′ or 3′), and associated prophage virulence genes. The rRNA operons are indicated as green blocks, and the hypervariable regions containing virulence genes associated with emm or prtF are hatched. The origin of replication is indicated (OriC).

TABLE 2.

Prophages of S. pyogenes and their integration sites and associated virulence genes

| Target gene (attB) | Gene target for integration (attB) | Associated phages (virulence genesa) | Identifierb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-stranded DNA binding protein recO | 3′ | MGAS10394.1 (sdn) | A |

| RNA helicase snf | 3′ | MGAS8232.1 (speA1) | B |

| Promoter of hypothetical Spy49_0371 | 5′ | NZ131.1 (none identified) | C |

| Dipeptidase | 5′ | SF370.1 (speC-spd1)MGAS10270.1 (speC-spd1)MGAS10750.1 (speC-spd1)Man.4 (speC-spd1) MGAS2096.1 (speC-spd1)MGAS9429.1 (speC-spd1)MGAS8232.2 (speC-spd1)ND23.1 (speC-spd1) | D |

| tRNAarg | 3′ | MGAS10394.2(speA4) | E |

| dTDP-glucose-4,6-dehydratase | 3′ | SF370.2 (speH-speI)MGAS10270.2 (spd3)MGAS10750.2 (spd3)Man.3 (speH-speI)MGAS9429.2 (speH-speI)HKU16.3 (speH-speI)ND23.3 (ssa)NZ131.2 (speH) | F |

| CRISPR type II system direct repeat sequence | 5′ | MGAS315.1 (none identified)SPsP6 (none identified) | G |

| tmRNA | 3′ | T12 (speA) MGAS5005.1 (speA2)A20.1 (speA2)M1 476.1 (speA2)HSC5.1 (speL-speM)MGAS315.2 (ssa)SpsP5 (ssa)MGAS10394.3 (speK-slaA)MGAS8232.3 (speL-speM)ND23.4 (spd3)MGAS6180.1 (speC-spd1)Alab49.1 (speL-speM) | H |

| trmA | 3′ | m46.1 (mefA) | I |

| comE | NDc | MGAS10394.4 (mefA) | J |

| DNA-binding protein HU | 5′ | SF370.3 (spd3)MGAS5005.2 (spd3)A20.2 (spd3)M1 476.2 (spd3)MGAS315.3 (spd4)SPsP4 (ssa)MGAS10750.3 (ssa)Man.2 (spd4)MGAS10394.5 (speC-spd1)MGAS8232.4 (spd3)ND23.2 (speI)HSC5.2 (spd3)Alab49.2 (speC-spd1)MGAS1882.1 (speK-slaA) | K |

| Promoter of yesN | 5′ | MGAS10270.3 (speK-sla)MGAS315.4 (speK-sla)SPsP3 (speK-sla)MGAS6180.2 (speK-slaA) | L |

| Regulatory protein recX | 5′ | MGAS315.5 (speA3)SPsP2 (speA3)Man.1 (spd1)MGAS10394.6 (sda)Alab49.3 (spd3) | M |

| Putative gamma-glutamyl kinase | 5′ | MGAS315.6 (sdn)SPsP1 (sdn) | N |

| tRNAser | 3′ | MGAS5005.3 (sda)A20.3 (sdaD2)M1 476.3 (sdaD2)HKU16.2 (sdaD2)MGAS2096.2 (sdaD2)MGAS9429.3 (sda) | O |

| HAD-like hydrolase | 5′ | MGAS8232.5 (sda) | P |

| Excinuclease subunit uvrA | 5′ | HSC5.3 (spd3)HKU16.1 (ssa speC)MGAS10394.7 (spd3) | Q |

| Conserved hypothetical protein Spy49_1532 | 5′ | NZ131.3 (spd3) | R |

| DNA MMR protein mutL | 5′ | SpyCIM1 (SF370.4)SpyCIM2 (MGAS10270.4)SpyCIM4 (MGAS10750.4)SpyCIM5 (man.5)SpyCIM6 (MGAS10394.8)SpyCIM25 SpyCIM28 (MGAS6180.3)SpyCIM53 (Alab49.4)SpyCIM59 (MGAS15252.1)SpyCIM59.1 (MGAS1882.1) | S |

| SSU ribosomal protein S4P | 3′’ | MGAS10270.5 (none identified)MGAS6180.4 (none identified)MGAS15252.2 (none identified) | T |

Prophage associated genes: superantigens: speA, speC, speH, speI, speK, speL, speM, ssa, and their alleles; DNases (streptodornases): sda, spn, spd, and their alleles; phospholipase: sla and alleles; macrolide efflux pump: mefA.

Identifier for the phylogenetic tree in Fig. 5.

ND, not determined.

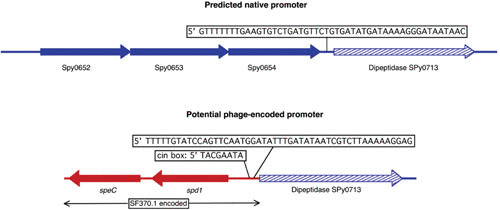

Integration of prophages occurs via homologous exchange between sequences shared between the phage and host chromosomes (attP and attB, respectively); this process is mediated by a phage-encoded integrase. These duplications between the phage and host DNA can be as little as a few nucleotides to over 100 bp, often including coding regions of the bacterial genome (48–50). In S. pyogenes, the identifiable duplications between attB and attP range from 12 bp (MGAS10394.1) to 96 bp (T12). An extensive survey of bacterial genome prophages found that prophages usually integrate into a gene open reading frame (ORF) (69% of identified prophages), while integration into an intragenic region, such as seen in coliphage Lambda, is less common, accounting for only 31% of prophages (50). Gene targets included tRNA genes (33%), tmRNA (8%), and various other genes (28%). Examples of each target site are observed in the S. pyogenes genome prophages (Table 2). Most commonly, the duplication occurs between the phage and the 3′ end of the host gene, and integration leaves the ORF intact via the duplicated sequence (50, 51). In S. pyogenes, however, the 5′ ends of genes are frequently targeted for integration, which potentially could lead to altered expression of the host gene (Table 2). The best-characterized system of altered host gene expression is the control of MMR in strain SF370 by S. pyogenes chromosomal island, serotype M1 (SpyCIM1), where the expression of genes for MMR, multidrug efflux, Holliday junction resolution, and base excision repair are controlled by this phage-like chromosomal island in response to growth (51–54). Similarly, the phage-like transposon MGAS10394.4 (also known as Tn1207.3 [55]) separates the DNA translocation machinery channel protein ComEC operon proteins 2 and 3, potentially creating a polar mutation that silences protein 3. A number of other streptococcal genes are targeted at their 5′ ends by prophages, including genes encoding the recombination protein RecX, a HAD-like hydrolase, and DNA-binding protein HU (Table 2). Other prophages integrate into the promoter region preceding the ORF in dipeptidase Spy-713, yesN, and a gamma-glutamyl kinase. In the case of dipeptidase Spy0713 that is targeted by members of the SF370.1 family, integration separates the ORF from the predicted native promoter and may replace it with a phage-encoded promoter found immediately upstream of the coding region following integration (Fig. 3). This phage-encoded promoter is preceded by a canonical CinA box (56), suggesting that this putative alternative promoter may also change the transcriptional program of the gene. In another example, two serotype M3 prophages were found integrated into a clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) type II system direct repeat; remarkably, this event may have led to the loss of CRISPR function in these cells. In all of these examples, the integration of a phage or phage-like element into the 5′ end of a gene has the potential to alter streptococcal gene expression by blocking transcription or providing an alternative promoter, and the frequency of such transcription-altering prophages may be an important regulatory strategy in S. pyogenes.

FIGURE 3.

Integration of prophage SF370.1 may provide an alternative promoter for dipeptidase Spy0713. In strains lacking an integrated prophage at this site, the native promoter for dipeptidase Spy0713 is downstream of the uncharacterized gene Spy0654; the predicted sequence is shown above. Integration of phage SF370.1 into Spy0713 separates this gene from that of the native promoter, and a predicted promoter encoded by the prophage is now positioned in front of the dipeptidase ORF. This phage-encoded promoter is preceded also by a canonical CinA box (56), which is not part of the native promoter. Transcription of prophage virulence genes speC and spd1 is from the opposite strand and should not influence transcription of Spy0713. Promoter predictions were done using the online tool at http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html (110).

Not all S. pyogenes prophages inactivate host genes following integration. Those that integrate into the 3′ ends of genes typically preserve gene function through the shared DNA sequence between the DNA molecules, and a number of examples are found in the genome prophages (Table 2). Bacteriophage T12 integrates by site-specific recombination into what was initially identified as a gene for a serine tRNA (57) but was correctly identified as a tmRNA gene after the completion of genome sequencing. Genes encoding tmRNA are frequently used as bacterial attachment sites (attB) for prophages that infect a range of bacterial species, including Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholerae, and Dichelobacter nodosus (50, 58). Besides the tmRNA gene, other 3′ gene targets used by genome prophages include the histone-like protein HU, dTDP-glucose-4,6-dehydratase, a putative SNF family helicase, and recombination protein recO.

Morphology and Genome Organization

Tailed phages with double-stranded DNA genomes (Caudovirales) are abundant in the biosphere, perhaps being the most frequent form of life on Earth (59). Of the Caudovirales, the phage subset Siphoviridae (icosahedral heads with long, noncontractile tails) make up about 60% of the total (60) order. A bacteriophage survey from the pregenomics era found that 92% of phages of the genus Streptococcus were Siphoviridae by the current classification (61), and the few early electron micrographs published reflect this prevalence (13, 25, 26, 38). Figure 4 shows the typical Siphoviridae morphology of two well-studied S. pyogenes phages, SF370.1 and T12. The tail fibers of SF370.1, which contain the hyaluronidase (hyaluronate lyase) used for capsule penetration during phage infection (62), are seen in the micrograph. The lytic transducing phage A25 also has typical Siphoviridae morphology (25, 38). While lysogenic phages may be found to be mostly members of the Siphoviridae, given their probable common pool of genetic modules (see below), other phage morphotypes may be found in the lytic phages, such as the Podoviridae C1 phage of the related group C streptococci (63). The coliphage Lambda has been the prototype for lysogenic prophages, and the genetic organization of most group A streptococcal genome prophages follows a similar general plan (64, 65), having identifiable genetic modules for integration and lysogeny, replication, regulation, head morphogenesis, head-tail joining, tail and tail fiber genes, lysis, and virulence (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 4.

Morphology of streptococcal lysogenic phages. Prophages SF370.1 (A) and T12 (B) release typical Siphoviridae virions following induction. The SF370.1 head is about 55 nm across and the tail is 168 nm in length in this micrograph. In this image, the tail fibers that contain hyaluronate lyase (hyaluronidase) are visible. The T12 capsid has similar dimensions, with the head being about 66 nm and the tail length 196 nm. Electron micrographs provided by W.M. McShan and S.V. Nguyen.

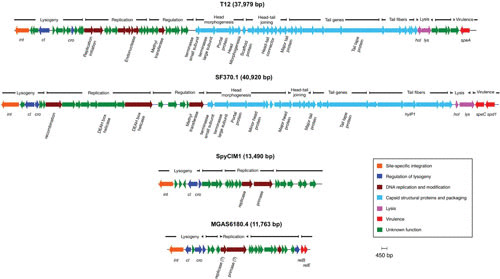

FIGURE 5.

The genetic structure of streptococcal prophages and phage-like chromosomal islands. The prophages found in the genomes of S. pyogenes follow a typical lambdoid pattern in their organization with genetic modules for lysogeny, DNA replication, regulation, head morphogenesis, head-tail joining, tails and tail fibers, lysis, and virulence.

Lysogeny module

Temperate phages are defined by their carriage of genes that establish and maintain a stable condition within a host cell, usually via site-specific integration. Minimally, lysogeny requires genes encoding an integrase (recombinase) and excisionase to mediate prophage DNA integration and excision as well as genes encoding repressor and antirepressor proteins to direct and control this process following the pattern seen in coliphage Lambda (66). Phage integrases typically mediate a recombination event between an identical sequence shared between the circular form of the prophage genome (attP) and the bacterial chromosome (attB), and the recognition of these DNA sequences is inherent in a given integrase protein (49, 67, 68). Most lambdoid phages usually have integrases that belong to the tyrosine integrase family, and the integrases of genome S. pyogenes prophages belong to this group. The excisionase gene in Lambda and many other Gram-negative host phages is positioned upstream of integrase, but in the lactic acid bacteria and other Gram-positive bacteria its genome location is variable (69, 70). Indeed, since excisionase proteins often show little conservation (71), the identification of the correct ORF in a given prophage is often difficult. Some excisionase genes may be provisionally identified in the S. pyogenes genome prophages by homology to other phages (64); however, to date, none have been confirmed experimentally.

DNA replication and modification

Following the lysogeny module is a region that shows considerable diversity between individual prophages and that encodes genes involving DNA replication and modification. Homologs of DNA polymerases, replisome organizer, restriction-modification systems, and primase genes are present in these regions as well as potential sequences that may function as origins of phage DNA replication (64, 65). Inspection of the genome annotations of these regions also shows that while many genes are unique to group A streptococcal phages, others have close homologs in phages from other streptococcal species such as Streptococcus thermophilus or S. equi, suggesting that a pool of genetic material is shared by a diverse group of phages (discussed below).

DNA packaging, capsid structural genes, and host lysis genes

The next region of prophage genomes is typically dedicated to the genes encoding the proteins for the assembly of phage heads and tails as well as the proteins needed to package the phage DNA into the heads and join this complex to the tails. The function of many of these genes has been inferred by homology to known phage proteins or sequences or by presumption of function due to their relative order in the chromosome. However, with the exception of the hyaluronate lyase (hyaluronidase) gene found in some S. pyogenes phage tail fibers (45, 62, 72), most of these genes have not been characterized experimentally, and these function assignments remain provisional. Following the capsid genes are the typical holin-lysin genes that are employed at the end of the lytic phase to lyse the infected bacterial cell and release the newly formed phage particles.

Virulence genes

Finally, at the distal end of the phage chromosome are the genes for host conversion that encode a range of virulence factors; prominent are exotoxins that are often superantigens and DNases such as streptodornase (Table 2). The origin of phage-encoded toxins remains unclear, but the fact that these toxin genes play no known role in the replication of the phage suggests that such genes were acquired at some point late in the phage’s evolutionary history. It has been proposed that virulence factors may be acquired by phages by imprecise excision events (73), but finding known phage-associated virulence genes independently on the bacterial chromosome has not occurred. Some superantigen genes are not associated with prophages (74, 75), but whether these genes are a genetic source of prophage superantigens is unclear. Lateral gene capture of virulence genes has undoubtedly been important in their dissemination (76), and such exotoxins may have evolved de novo as elements to increase bacterial host cell fitness (77). Decayed prophage remnants with superantigen domains may be seen in the S. pyogenes genome (65), and these regions may serve as a genetic reservoir for virulence genes. Similarly, host-range variants of phages from different bacterial species or even genera are another potential reservoir for toxin genes; for example, the speA gene of S. pyogenes and the enterotoxins B and C1 of Staphylococcus aureus show a significant degree of homology and thus may share a common origin (18).

Diversity of Lysogenic Phages

Structural genes dominate phylogenic relations

Botstein, in a seminal 1980 paper, proposed that the product of bacteriophage evolution is not the individual virus but a pool of interchangeable genetic modules, each of which carries out a biological function in the phage lifecycle; natural selection therefore acts at the level of these individual modules (functional units) (78). Phylogenetic analysis of the Lambdoid S. pyogenes prophages predicts that several prominent groups exist (Fig. 6). Within each branch, considerable group diversity may exist in terms of targeted bacterial attachment site and encoded virulence factors (Table 2). Inspection of each group shows that phylogeny is driven by large shared blocks of genes encoding proteins for DNA packaging, heads and tails, and host lysis (Table 3); for example, see the analysis of the group of prophages containing phage T12, where all members of the group minimally share these structural genes (Fig. 7). However, others, such as the SF370.1 group, are much more clonal, all sharing the same virulence and lysogeny modules. Therefore, the phylogeny of individual functional modules (such as toxin genes) may be unrelated to other regions of the genome (such as the lysogeny module or capsid genes). The apparent shuffling of the individual modules may be driven by both homologous and nonhomologous recombination (64, 79–82). The actual driving force behind this engine of prophage diversity in S. pyogenes remains poorly understood, but some clues have emerged. In a survey of 21 toxin-carrying S. pyogenes strains, 18 were found to carry a highly conserved ORF adjacent to the toxin genes (83). This ORF, which was named paratox, may help promote homologous recombination between phages so that toxin genes may be exchanged, leading to phage diversity. Some genome phages or phage-like elements do not readily fall into any group: MGAS10394.2, HKU16.1, NZ131.1, m46.1, and MGAS10394.4 are phylogenetic outliers that have little commonality with other prophages. When the prophages are clustered by the M type of their host cell, some patterns do emerge (Figure 8). There appears to be a pool of phages shared by M1 and M12 S. pyogenes strains, for example. M3 strains have some phages that appear more frequently within this serotype, but the current sample size is too small to draw any definite conclusions. Indeed, more genomic data will be required to get a clearer picture of prophage distribution by serotype.

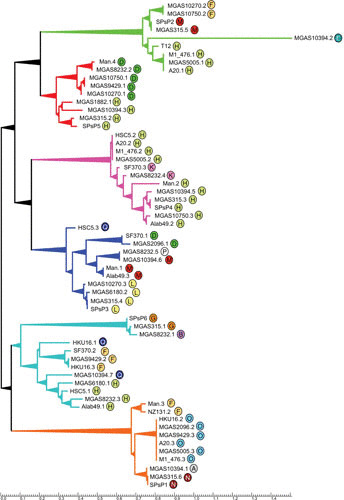

FIGURE 6.

Phylogenetic relationships of S. pyogenes prophages. An unrooted phylogenetic tree was created by DNA alignment of the genome prophages. Prophages MGAS10394.2, HKU16.1, NZ131.1, m46.1, and MGAS10394.4 were so dissimilar from the other prophages that each occupied an independent branch; consequently, for clarity, they are not shown on the tree. The alignment organized the remaining prophages into six major branches, and the encircled letter identifier by each prophage refers to its associated attachment site (attB) described in Table 2; each identifier is colored to facilitate viewing. The groups are defined by shared modules for structural genes (Table 3). The tree was created using the software packages Clustal-omega and TreeGraph 2 (111, 112).

TABLE 3.

S. pyogenes prophages grouped by shared structural modules

| T12 group | SF370.1 group | SF370.2 group | SF370.3 group | MGAS315.1 group | MGAS315.2 group | MGAS315.6 group | MGAS6180.4 group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGAS5005.1 | SF370.1a | SF370.2a | SF370.3a | MGAS315.1* | MGAS10270.1a | MGAS5005.3 | MGAS10270.5 |

| M1 476.1 | MGAS10270.3a | MGAS10394.7a | MGAS5005.2 | SPsP5* | MGAS315.2a | M1 476.3 | MGAS6180.4 |

| A20.1 | MGAS315.4a | MGAS9429.2a | M1 476.2 | MGAS8232.1* | SpsP6a | A20.3 | MGAS15252.2 |

| MGAS10270.2 | SPsP3a | HKU16.3 | A20.2 | MGAS10750.1a | MGAS315.6a | ||

| MGAS315.5 | Man.1a | HSC5.1a | MGAS315.3a | Man.4a | SPsP1a | ||

| SPsP2 | MGAS10394.6a | MGAS8232.3a | SPsP4a | MGAS10394.3a | Man.3a | ||

| MGAS10750.2 | MGAS2096.1a | MGAS6180.1 | MGAS10750.3a | MGAS9429.1a | MGAS10394.1a | ||

| T12 | HSC5.3a | Alab49.1a | Man.2a | MGAS8232.2a | MGAS2096.2a | ||

| MGAS8232.5a | MGAS10394.5a | MGAS1882.1a | MGAS9429.3a | ||||

| MGAS6180.2a | HKU16.1a | HKU16.2 | |||||

| Alab49.3a | HSC5.2a | NZ131.2a | |||||

| MGAS8232.4a | |||||||

| NZ131.3a | |||||||

| Alab49.2a |

Contains a hyaluronate lyase (hyaluronidase) as a component of the tail fiber.

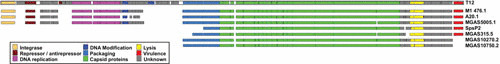

FIGURE 7.

Shared genetic modules of the T12-related prophage family. The top line is the simplified genetic map of bacteriophage T12 colored by gene or genetic module for the integrase, repressor-antirepressor, DNA replication, DNA modification, DNA packaging, capsid proteins, lysis, and virulence (speA). Regions of unknown or uncertain function are colored gray. Beneath T12 is shown the genetic maps of the other genome prophages that share the extended region dedicated to packaging, capsid proteins, and lysis. DNA regions that are divergent from T12 are not shown. The figure illustrates that a structural gene module can be associated with divergent attachment sites or virulence genes. The alignment was derived from the phylogenetic tree presented in Fig. 5.

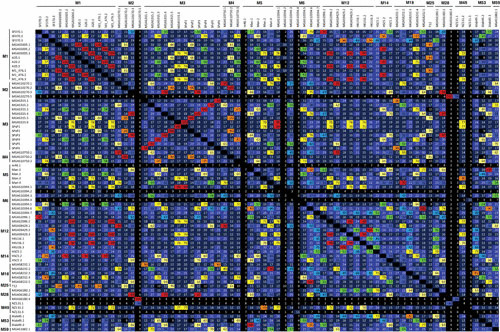

FIGURE 8.

Identity matrix of genome prophages grouped by M type. The identity matrix presents the Clustal-omega DNA alignment from Fig. 5 as the percentage identity between genome prophages, which are grouped by the M type of their host streptococcus. The numbers within each cell represent the identity rounded to the nearest whole number, and the cell colors show the range into which each identity falls by increasing percentages of 10.

Prophage hyaluronidase (hyaluronate lyase)

A subset of genome prophages encode a hyaluronidase (hyaluronate lyase, hyaluronoglucosaminidase) gene (Table 3). Two alleles (hylP and hylP2) of this gene were originally identified (45, 72), and subsequent studies show that this gene exists in multiple alleles mainly distinguished by single nucleotide polymorphisms and by collagen-like domain indels in some variants (84, 85). The phage hyaluronidase gene found in the genome sequences also shows considerable diversity that may have resulted from recombination (45, 72, 84, 85). It had been suggested that phage hyaluronidase was a potential virulence factor, but the crystallization and structural analysis of HylP1 from phage SF370.1 suggested that the function of this enzyme is to introduce widely spaced cuts in the bacterial hyaluronic acid to cause a local reduction in capsule viscosity and aid phage invasion during infection (62). Similar structural properties were observed in the hyaluronidase proteins encoded by prophages SF370.2 and SF370.3 (86).

Horizontal transfer of genes from other species

One observation to come from extensive genome sequencing is that the lysogenic phages of S. pyogenes share a gene pool with other streptococcal species, including those that are closely related (e.g., S. equi) as well as those more distantly related (S. pneumoniae). These shared genes include ones essential to the basic phage life cycle, such as capsid proteins, and virulence genes such as exotoxins and superantigens. For example, S. equi prophages share many superantigens or virulence genes with S. pyogenes phages, including slaA, speL, speM, speH, and speI (87). This study found that phage Seq.4 from S. equi strain Se4047 was very closely related at the DNA level to S. pyogenes Manfredo phage Man.3, including the two phage-encoded exotoxins. Similarly, Streptococcus agalactiae phage JX01, isolated in milk from cattle with mastitis, shares extensive homology with S. pyogenes prophage MGAS315.2 in the modules controlling DNA replication, tail, head-tail connector, head capsid, and DNA packaging, with over 97% amino acid identity between their terminase subunits; however, no virulence-associated genes were identified in this phage (88). The temperate phage MM1 of S. pneumoniae also draws from a common pool of structural genes, sharing the DNA packaging, the head-to-tail joining, and the tail genes with phage SF370.1 (89). Further, this phage and MGAS315.4 share tail and tape measure genes. Some of the oral streptococci also have phages that contribute to this common pool. The portal, terminase, major capsid protein, major tail protein, and tape measure protein of Streptococcus mitis phage SM1 share homology with prophage SF370.3 and a number of other phages of low-GC Gram-positive hosts (90). While acquisition of these phage structural genes from other streptococcal species may not directly impact virulence the same way that a novel exotoxin would, these capsid genes may help to expand the host range within the group A organisms. The dairy species Lactococcus lactis also is included in this pool of shared phage genes since prophage SF370.3 closely resembles the cos-site temperate phage r1t of L. lactis (64, 91).

S. PYOGENES PROPHAGES AND THE HOST PHENOTYPE

Prophages as Vectors for Virulence Genes

As described above, the link between bacteriophages and virulence in S. pyogenes may be traced to the earliest days of bacteriophage research. A considerable range of virulence-associated genes are carried by these prophages and prophage-like elements, including superantigens (speA, speC, speG, speH, speI, speJ, speK, speL, SSA, and variants), DNases (spd1, MF2, MF3, and MF4), phospholipase A2 (sla), and macrolide resistance (mefA). It is quite common for a given prophage to carry more than one virulence gene, such as phage SF370.1, which contains both speC and spd1. The number and diversity of prophage-associated virulence genes in S. pyogenes argues that these frequently play an important role in pathogenesis.

The expression of phage-encoded virulence genes, rather than an autonomous event, may be linked to the host streptococcal cell genetic background (92) or physiological state (93). For example, the reception of signals from cocultured human cells influences S. pyogenes prophage virulence gene expression. Human pharyngeal cells release a soluble factor that stimulates expression of pyrogenic exotoxin C (SpeC) and phage DNase Spd1 as well as induction and release of phages by S. pyogenes grown in coculture (94, 95). Similar results were observed independently where the expression of prophage-encoded toxins SpeK and Sla was enhanced by coculture with pharyngeal cells (96). Eukaryotic cells also provide an environment that promotes the transfer of toxin-producing phages from a lysogen to a new host; this phenomenon can occur in either in vitro culture or a mouse model (97). However, the genetic background of the streptococcus influences whether the acquisition of a new prophage expressing DNase results in enhanced pathogenic potential of the resulting lysogen (92). Some of these bacterium-phage interactions appear to be linked to the cellular regulatory networks; for example, the S. pyogenes global regulator Rgg can control the expression of the phage-encoded DNase Spd3 by interacting with phage promoters of that gene (93). Alteration of streptococcal gene expression may also impact the levels of phage toxins released during an infection. Employing a murine subcutaneous chamber model, Aziz and coworkers showed that the expression of S. pyogenes protease SpeB diminished after extended colonization in the mouse; this loss of protease activity occurred with simultaneous enhancement of phage-encoded exotoxin SpeA and streptodornase expression (98). Interestingly, these altered expression patterns were independent events.

Phage-Like Elements that Carry Antimicrobial Resistance Genes

S. pyogenes harbors a number of genetic elements that appear to have phage sequences combined with sequences from transposons or plasmids and are vectors for antibiotic resistance. One example is Φm46.1, the main S. pyogenes element carrying the mefA and tetO genes (99). The chromosome integration site of Φm46.1 is a 23S rRNA uracil methyltransferase gene, and this phage has high levels of amino acid sequence similarity to Φ10394.4 of S. pyogenes strain MGAS10394.4 and λSa04 of S. agalactiae A909 (100, 101). The antibiotic resistance cassette of the PhiM46.1 family may be a recent acquisition: the lysogeny module appears split due to the insertion of a segment containing tetO and mefA into the phage DNA (99). Phage Φm46.1, besides being found frequently in S. pyogenes, has a broad host range that allows it to transduce antibiotic resistance to strains of S. agalactiae, Streptococcus gordonii, and S. suis (102). All of these species share a highly conserved attB site, which undoubtedly facilitates dissemination of this phage. Further, within GAS, Φm46.1 appears to be able to infect a wide range of M types (103). The ability of this phage family to mediate transfer of antibiotic resistance shows again how frequently S. pyogenes prophages modify the phenotypes of their host to improve fitness.

Prophages, Phage-Like Elements, and Regulation of Host Gene Expression

The impact of prophages on the host phenotype extends beyond toxigenic conversion. One early report noted the possible control of M protein and serum opacity factor expression by a prophage or other extrachromosomal element that could be cured upon passage. In light of our current understanding of global transcriptional regulators, such a change suggests that the identified prophage could be interacting with or substituting for a regulator to mediate the changes reported in the older literature. The regulator Rgg has been shown to interact with several prophage-encoded genes. In addition to the DNase Spd3 mentioned above (93), Rgg has been shown to bind prophage-encoded promoters controlling genes for an integrase and a surface antigen (104). Recent studies suggest that the two-component regulatory system CovRS may also be influenced by prophage carriage. Many invasive strains of S. pyogenes often have mutations in covRS, and a subset of these invasive strains produce no detectable capsule at 37°C but produce capsule at sub-body temperatures. Brown and coworkers reported that the presence of prophage PhiHSC5.3 could rescue capsule production independent of temperature in a covR-defective strain but that this spontaneous capsule production was eliminated by curing of this prophage (105). Thus, in this case a prophage appears to act as a thermoregulator, possibly repressing capsule production at 37°C.

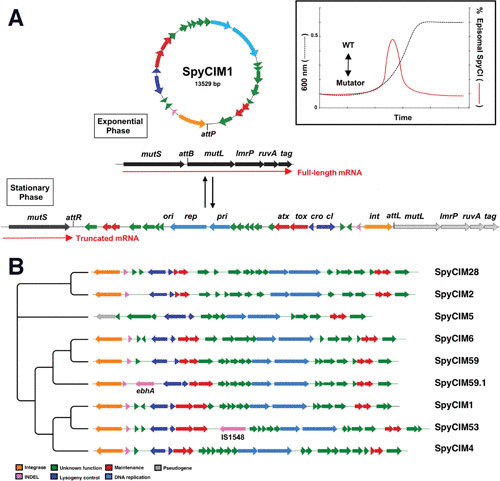

A mobile element frequently found in S. pyogenes genomes is the phage-like SpyCI, which integrates into the 5′ end of the MMR gene mutL (Fig. 9A) (52–54). The SpyCIs share integrase modules with related phage-like chromosomal islands from Streptococcus anginosus, Streptococcus canis, S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, Streptococcus intermedius, and Streptococcus parauberis (Fig. 9B) (52). The DNA replication module is even more widespread among other species, and in addition to the ones named above, is found in related chromosomal islands found in S. agalactiae, S. mitis, S. pneumoniae, Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae, S. suis, and S. thermophilus (52). The remarkable defining characteristic of SpyCIs is how they regulate MMR and the other genes in the operon (major facilitator family efflux pump lmrP, Holliday junction resolvase ruvA, and base excision repair glycosylase tag). The best-studied member of this family, SpyCIM1 from strain SF370, is a dynamic element that excises from the bacterial chromosome during early logarithmic growth and replicates as a circular episome (54). As the bacterial population reaches the end of the logarithmic phase and enters the stationary phase, SpyCIM1 reintegrates into the unique attachment site at the beginning of mutL ORF (Fig. 9A, insert). The result of this cycle is that SpyCIM1 acts as a growth-dependent molecular switch to control the expression of MMR, causing SF370 to alternate between a mutator and wild-type phenotype in response to growth: during rapid cell division and DNA replication, the integrity of the genome is maintained by an active MMR system, while during periods of infrequent cell division, mutations may accumulate at a higher rate (53, 54). Preliminary studies suggest that the SpyCIs, which lack identifiable structural genes, may employ a helper prophage for packaging and dissemination in a fashion similar to the well-characterized S. aureus pathogenicity islands (106).

FIGURE 9.

(A) SpyCIM1 regulation of the MMR operon through dynamic site-specific excision and integration. The MMR operon of S. pyogenes groups the genes encoding DNA MMR (mutS and mutL), multidrug efflux (lmrP), Holliday-junction resolvase (ruvA), and base excision repair glycosylase (tag). The orientation of this chromosomal region is shown here from the lagging strand to emphasize the MMR operon transcription. During exponential phase, SpyCIM1 excises from the chromosome, circularizes, and replicates as an episome, restoring transcription of the entire DNA MMR operon (WT). Excision and mobilization occur early in logarithmic growth in response to as yet unknown cellular signals (insert; adapted from Scott et al. [53]). As logarithmic growth continues, SpyCIM1 reintegrates into mutL at attB, and by the time the culture reaches the stationary phase, the integration process has completed, again blocking transcription of the MMR operon. WT, wild-type phenotype associated with unimpeded expression of the MMR operon. Reproduced from Frontiers in Microbiology (52) under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY 4.0). (B) The phylogenetic tree of the SpyCI DNA sequences is presented. The tree was created with TreeGraph 2 (111) using previously analyzed data (52).

More recent studies have shown that SpyCIM1 and related phage-like chromosomal islands also act as global regulators for host genes. The elimination of SpyCIM1 shifted the expression of over 100 bacterial genes involved in virulence and metabolism (107). These shifts in global expression occurred at both the logarithmic and stationary phases, upregulating some genes while repressing the expression of others. Some of the virulence genes with increased expression included the antiphagocytic M protein (emm1), streptolysin O (slo), capsule operon (hasABC), and streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin (speB) (107). Other genes, such as the regulator ropB, arginine deiminase, and l-lactate oxidase, were depressed in expression in either early or late logarithmic growth or both. Several uncharacterized SpyCIM1 genes are predicted to encode proteins with helix-turn-helix domains, which could possibly act as DNA regulatory elements to control host genes. Further work will be needed to understand the molecular mechanism of SpyCIM1 as a regulator. Thus, phage-like chromosomal islands in S. pyogenes appear not only to mediate a growth-dependent mutator phenotype but also to be global regulators. This remarkable evolutionary adaption may help promote survival of S. pyogenes when faced with changing environments.

Prophages as Agents of Genome Plasticity

Our understanding of the role of prophages in shaping the biology of S. pyogenes continues to evolve. In S. pyogenes and many other bacterial species, symmetric genome rearrangements have been observed, and often these genome rearrangements from S. pyogenes patient isolates are associated with invasive infections. A hypervirulent M23 serotype strain, M23ND, was found to have a unique and extensive asymmetric rearrangement in its genome, these rearrangements being mediated by competence genes (rRNA-comX), transposons (IS1239), and conserved prophage genes (hylP) (108, 109). While these rearrangements did not affect genome integrity, some rearrangements did recluster a broad set of CovRS regulated genes to the same leading strands, suggesting a potential selective advantage to S. pyogenes by clustering genes for virulence, growth, and/or survival. An approximately 400,000-bp inversion was found to have occurred through shared hyaluronidase genes (hylP) between two different genome prophages; this inversion was predicted to prevent normal excision of either prophage due to the spatial disruption of the attachment site sequences. Remarkably, induction with mitomycin C led to reversal of the large inversion, allowing induction of these prophages to the lytic cycle. A subpopulation of survival cells was generated following induction that no longer had the large-scale inversion (108). Thus, genome prophages appear not only to improve the fitness of their host cell through the carriage of virulence genes, but also to play a role in genome plasticity.

CONCLUSIONS

The association of S. pyogenes with its bacteriophages is a major factor in the biology of this human pathogen, influencing the distribution of virulence genes, the spread of antibiotic resistance, the horizontal transfer of host genes, and the population distribution of cells. These relationships can range from simple predator-prey models to complex symbiotic associations and genome plasticity that promote the evolutionary success of both cell and phage. Further, in prophages the choice of integration site into the bacterial chromosome may alter the streptococcal genotype through either gene inactivation or replacement of normal promoter elements with phage-encoded ones. The similarity that prophages have to pathogenicity islands can hardly be overlooked, and the range of prophage-mediated characteristics that add to host survival or virulence can be easily predicted to increase as new investigations are reported. Genome sequencing has contributed greatly to our understanding of prophage distribution and genetic composition, and this bank of knowledge has been and will be an important foundation for future biological studies of the interactions of S. pyogenes and its phages that will be certain to reveal many novel and perhaps surprising relationships.

REFERENCES

- 1.Twort FW. 1915. An investigation on the nature of ultra-microscopic viruses. Lancet 186:1241–1243 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)20383-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cantacuzene J, Boncieu O. 1926. Modifications subies pare des streptococques d’origine non-scarlatineuse qu contact des produits scarlatineux filtres. C R Acad Sci 182:1185. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frobisher M, Brown JH. 1927. Transmissible toxicogenicity of streptococci. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 41:167–173. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans AC. 1933. Inactivation of antistreptococcus bacteriophage by animal fluids. Public Health Rep 48:411–426 10.2307/4580757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans AC. 1934. Streptococcus bacteriophage: a study of four serological types. Public Health Rep 49:1386–1401 10.2307/4581377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans AC. 1934. The prevalence of Streptococcus bacteriophage. Science 80:40–41 10.1126/science.80.2063.40. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans AC. 1940. The potency of nascent Streptococcus bacteriophage B. J Bacteriol 39:597–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans AC, Sockrider EM. 1942. Another serologic type of streptococcic bacteriophage. J Bacteriol 44:211–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kjems E. 1960. Studies on streptococcal bacteriophages. 4. The occurrence of lysogenic strains among group A haemolytic streptococci. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 49:199–204 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1960.tb01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krause RM. 1957. Studies on bacteriophages of hemolytic streptococci. I. Factors influencing the interaction of phage and susceptible host cell. J Exp Med 106:365–384 10.1084/jem.106.3.365. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maxted WR. 1952. Enhancement of streptococcal bacteriophage lysis by hyaluronidase. Nature 170:1020–1021 10.1038/1701020b0. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maxted WR. 1955. The influence of bacteriophage on Streptococcus pyogenes. J Gen Microbiol 12:484–495 10.1099/00221287-12-3-484. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kjems E. 1958. Studies on streptococcal bacteriophages. 3. Hyaluronidase produced by the streptococcal phage-host cell system. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 44:429–439 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1958.tb01094.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kjems E. 1955. Studies on streptococcal bacteriophages. I. Technique of isolating phage-producing strains. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 36:433–440 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1955.tb04638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maxted W. 1964. Streptococcal bacteriophages, p 25–52. In Uhr J (ed), Streptococci, Rheumatic Fever, and Glomerulonephritis. Williams and Wilkins Co, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zabriskie JB. 1964. The role of temperate bacteriophage in the production of erythrogenic toxin by group A streptococci. J Exp Med 119:761–780 10.1084/jem.119.5.761. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weeks CR, Ferretti JJ. 1984. The gene for type A streptococcal exotoxin (erythrogenic toxin) is located in bacteriophage T12. Infect Immun 46:531–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weeks CR, Ferretti JJ. 1986. Nucleotide sequence of the type A streptococcal exotoxin (erythrogenic toxin) gene from Streptococcus pyogenes bacteriophage T12. Infect Immun 52:144–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson LP, Schlievert PM. 1984. Group A streptococcal phage T12 carries the structural gene for pyrogenic exotoxin type A. Mol Gen Genet 194:52–56 10.1007/BF00383496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferretti J, Köhler W. History of streptococcal research. In Ferretti J, Stevens D, Fischetti V (ed), Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations. University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26866232. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mashburn-Warren L, Morrison DA, Federle MJ. 2012. The cryptic competence pathway in Streptococcus pyogenes is controlled by a peptide pheromone. J Bacteriol 194:4589–4600 10.1128/JB.00830-12. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leonard CG, Colón AE, Cole RM. 1968. Transduction in group A streptococcus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 30:130–135 10.1016/0006-291X(68)90459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pomrenke ME, Ferretti JJ. 1989. Physical maps of the streptococcal bacteriophage A25 and C1 genomes. J Basic Microbiol 29:395–398 10.1002/jobm.3620290621. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moynet DJ, Colon-Whitt AE, Calandra GB, Cole RM. 1985. Structure of eight streptococcal bacteriophages. Virology 142:263–269 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malke H. 1970. Characteristics of transducing group A streptococcal bacteriophages A 5 and A 25. Arch Gesamte Virusforsch 29:44–49 10.1007/BF01253879. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zabriskie JB, Read SE, Fischetti VA. 1972. Lysogeny in streptococci, p 99–118. In Wannamaker LW, Matsen JM (ed), Streptococci and Streptococcal Diseases: Recognition, Understanding, and Management. Academic Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Read SE, Reed RW. 1972. Electron microscopy of the replicative events of A25 bacteriophages in group A streptococci. Can J Microbiol 18:93–96 10.1139/m72-015. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill JE, Wannamaker LW. 1981. Identification of a lysin associated with a bacteriophage (A25) virulent for group A streptococci. J Bacteriol 145:696–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malke H. 1969. Transduction of Streptococcus pyogenes K 56 by temperature-sensitive mutants of the transducing phage A 25. Z Naturforsch B 24:1556–1561 10.1515/znb-1969-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischetti VA, Barron B, Zabriskie JB. 1968. Studies on streptococcal bacteriophages. I. Burst size and intracellular growth of group A and group C streptococcal bacteriophages. J Exp Med 127:475–488 10.1084/jem.127.3.475. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cleary PP, Wannamaker LW, Fisher M, Laible N. 1977. Studies of the receptor for phage A25 in group A streptococci: the role of peptidoglycan in reversible adsorption. J Exp Med 145:578–593 10.1084/jem.145.3.578. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCullor K, Postoak B, Rahman M, King C, McShan WM. 2018. Genomic sequencing of high-efficiency transducing streptococcal bacteriophage A25: consequences of escape from lysogeny. J Bacteriol 200:e00358-18. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wannamaker LW, Almquist S, Skjold S. 1973. Intergroup phage reactions and transduction between group C and group A streptococci. J Exp Med 137:1338–1353 10.1084/jem.137.6.1338. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casjens SR, Gilcrease EB. 2009. Determining DNA packaging strategy by analysis of the termini of the chromosomes in tailed-bacteriophage virions. Methods Mol Biol 502:91–111 10.1007/978-1-60327-565-1_7. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marks LR, Mashburn-Warren L, Federle MJ, Hakansson AP. 2014. Streptococcus pyogenes biofilm growth in vitro and in vivo and its role in colonization, virulence, and genetic exchange. J Infect Dis 210:25–34 10.1093/infdis/jiu058. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crater DL, van de Rijn I. 1995. Hyaluronic acid synthesis operon (has) expression in group A streptococci. J Biol Chem 270:18452–18458 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18452. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henningham A, Yamaguchi M, Aziz RK, Kuipers K, Buffalo CZ, Dahesh S, Choudhury B, Van Vleet J, Yamaguchi Y, Seymour LM, Ben Zakour NL, He L, Smith HV, Grimwood K, Beatson SA, Ghosh P, Walker MJ, Nizet V, Cole JN. 2014. Mutual exclusivity of hyaluronan and hyaluronidase in invasive group A Streptococcus. J Biol Chem 289:32303–32315 10.1074/jbc.M114.602847. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malke H. 1972. Linkage relationships of mutations endowing Streptococcus pyogenes with resistance to antibiotics that affect the ribosome. Mol Gen Genet 116:299–308 10.1007/BF00270087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colón AE, Cole RM, Leonard CG. 1970. Transduction in group A streptococci by ultraviolet-irradiated bacteriophages. Can J Microbiol 16:201–202 10.1139/m70-034. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malke H. 1969. Transduction of Streptococcus pyogenes K 56 by temperature-sensitive mutants of the transducing phage A 25. Z Naturforsch B 24:1556–1561 10.1515/znb-1969-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hyder SL, Streitfeld MM. 1978. Transfer of erythromycin resistance from clinically isolated lysogenic strains of Streptococcus pyogenes via their endogenous phage. J Infect Dis 138:281–286 10.1093/infdis/138.3.281. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Colón AE, Cole RM, Leonard CG. 1972. Intergroup lysis and transduction by streptococcal bacteriophages. J Virol 9:551–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bessen DE, McShan WM, Nguyen SV, Agarwal S, Shetty A, Tettelin H. 2015. Molecular epidemiology and genomics of group A Streptococcus. Infect Genet Evol 33:393–418. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chaussee MS, Liu J, Stevens DL, Ferretti JJ. 1996. Genetic and phenotypic diversity among isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes from invasive infections. J Infect Dis 173:901–908 10.1093/infdis/173.4.901. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hynes WL, Hancock L, Ferretti JJ. 1995. Analysis of a second bacteriophage hyaluronidase gene from Streptococcus pyogenes: evidence for a third hyaluronidase involved in extracellular enzymatic activity. Infect Immun 63:3015–3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wannamaker LW, Skjold S, Maxted WR. 1970. Characterization of bacteriophages from nephritogenic group A streptococci. J Infect Dis 121:407–418 10.1093/infdis/121.4.407. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu C-E, Ferretti JJ. 1989. Molecular epidemiologic analysis of the type A streptococcal exotoxin (erythrogenic toxin) gene (speA) in clinical Streptococcus pyogenes strains. Infect Immun 57:3715–3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campbell AM. 1992. Chromosomal insertion sites for phages and plasmids. J Bacteriol 174:7495–7499 10.1128/jb.174.23.7495-7499.1992. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Groth AC, Calos MP. 2004. Phage integrases: biology and applications. J Mol Biol 335:667–678 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.082. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fouts DE. 2006. Phage_Finder: automated identification and classification of prophage regions in complete bacterial genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 34:5839–5851 10.1093/nar/gkl732. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McShan WM, Ferretti JJ. 2007. Bacteriophages and the host phenotype, p 229–250. In McGrath S (ed), Bacteriophages: genetics and molecular biology. Horizon Scientific Press, Hethersett, Norwich, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nguyen SV, McShan WM. 2014. Chromosomal islands of Streptococcus pyogenes and related streptococci: molecular switches for survival and virulence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4:109 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00109. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scott J, Nguyen S, King CJ, Hendrickson C, McShan WM. 2012. Mutator phenotype prophages in the genome strains of Streptococcus pyogenes: control by growth state and by a cryptic prophage-encoded promoter. Front Microbiol 3:317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scott J, Thompson-Mayberry P, Lahmamsi S, King CJ, McShan WM. 2008. Phage-associated mutator phenotype in group A Streptococcus. J Bacteriol 190:6290–6301 10.1128/JB.01569-07. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.D’Ercole S, Petrelli D, Prenna M, Zampaloni C, Catania MR, Ripa S, Vitali LA. 2005. Distribution of mef(A)-containing genetic elements in erythromycin-resistant isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes from Italy. Clin Microbiol Infect 11:927–930 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01250.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Claverys J-P, Martin B. 1998. Competence regulons, genomics and streptococci. Mol Microbiol 29:1126–1127 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01005.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McShan WM, Tang Y-F, Ferretti JJ. 1997. Bacteriophage T12 of Streptococcus pyogenes integrates into the gene encoding a serine tRNA. Mol Microbiol 23:719–728 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2591616.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams KP. 2002. Integration sites for genetic elements in prokaryotic tRNA and tmRNA genes: sublocation preference of integrase subfamilies. Nucleic Acids Res 30:866–875 10.1093/nar/30.4.866. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brüssow H, Hendrix RW. 2002. Phage genomics: small is beautiful. Cell 108:13–16 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00637-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ackermann HW. 2006. Classification of bacteriophages, p 8–16. In Calendar R (ed), The Bacteriophages, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ackermann H-W, DuBow MS. 1987. Viruses of Prokaryotes: General Properties of Bacteriophages, vol 1. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith NL, Taylor EJ, Lindsay AM, Charnock SJ, Turkenburg JP, Dodson EJ, Davies GJ, Black GW. 2005. Structure of a group A streptococcal phage-encoded virulence factor reveals a catalytically active triple-stranded beta-helix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:17652–17657 10.1073/pnas.0504782102. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nelson D, Schuch R, Zhu S, Tscherne DM, Fischetti VA. 2003. Genomic sequence of C1, the first streptococcal phage. J Bacteriol 185:3325–3332 10.1128/JB.185.11.3325-3332.2003. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Desiere F, McShan WM, van Sinderen D, Ferretti JJ, Brüssow H. 2001. Comparative genomics reveals close genetic relationships between phages from dairy bacteria and pathogenic streptococci: evolutionary implications for prophage-host interactions. Virology 288:325–341 10.1006/viro.2001.1085. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Canchaya C, Desiere F, McShan WM, Ferretti JJ, Parkhill J, Brüssow H. 2002. Genome analysis of an inducible prophage and prophage remnants integrated in the Streptococcus pyogenes strain SF370. Virology 302:245–258 10.1006/viro.2002.1570. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ptashne M. 2004. A Genetic Switch: Phage Lambda Revisited, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Campbell A, del-Campillo-Campbell A, Ginsberg ML. 2002. Specificity in DNA recognition by phage integrases. Gene 300:13–18 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00846-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Argos P, Landy A, Abremski K, Egan JB, Haggard-Ljungquist E, Hoess RH, Kahn ML, Kalionis B, Narayana SV, Pierson LS. 1986. The integrase family of site-specific recombinases: regional similarities and global diversity. EMBO J 5:433–440 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04229.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bruttin A, Desiere F, Lucchini S, Foley S, Brüssow H. 1997. Characterization of the lysogeny DNA module from the temperate Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophage phi Sfi21. Virology 233:136–148 10.1006/viro.1997.8603. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Breüner A, Brøndsted L, Hammer K. 1999. Novel organization of genes involved in prophage excision identified in the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage TP901-1. J Bacteriol 181:7291–7297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lewis JA, Hatfull GF. 2001. Control of directionality in integrase-mediated recombination: examination of recombination directionality factors (RDFs) including Xis and Cox proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 29:2205–2216 10.1093/nar/29.11.2205. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hynes WL, Ferretti JJ. 1989. Sequence analysis and expression in Escherichia coli of the hyaluronidase gene of Streptococcus pyogenes bacteriophage H4489A. Infect Immun 57:533–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barksdale L, Arden SB. 1974. Persisting bacteriophage infections, lysogeny, and phage conversions. Annu Rev Microbiol 28:265–299 10.1146/annurev.mi.28.100174.001405. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Proft T, Sriskandan S, Yang L, Fraser JD. 2003. Superantigens and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis 9:1211–1218 10.3201/eid0910.030042. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Proft T, Moffatt SL, Berkahn CJ, Fraser JD. 1999. Identification and characterization of novel superantigens from Streptococcus pyogenes. J Exp Med 189:89–102 10.1084/jem.189.1.89. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ochman H, Lawrence JG, Groisman EA. 2000. Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation. Nature 405:299–304 10.1038/35012500. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brüssow H, Canchaya C, Hardt WD. 2004. Phages and the evolution of bacterial pathogens: from genomic rearrangements to lysogenic conversion. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 68:560–602 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.560-602.2004. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Botstein D. 1980. A theory of modular evolution for bacteriophages. Ann N Y Acad Sci 354:484–490 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb27987.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ford ME, Sarkis GJ, Belanger AE, Hendrix RW, Hatfull GF. 1998. Genome structure of mycobacteriophage D29: implications for phage evolution. J Mol Biol 279:143–164 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1610. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lucchini S, Desiere F, Brüssow H. 1999. Similarly organized lysogeny modules in temperate Siphoviridae from low GC content gram-positive bacteria. Virology 263:427–435 10.1006/viro.1999.9959. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Monod C, Repoila F, Kutateladze M, Tétart F, Krisch HM. 1997. The genome of the pseudo T-even bacteriophages, a diverse group that resembles T4. J Mol Biol 267:237–249 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0867. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Juhala RJ, Ford ME, Duda RL, Youlton A, Hatfull GF, Hendrix RW. 2000. Genomic sequences of bacteriophages HK97 and HK022: pervasive genetic mosaicism in the lambdoid bacteriophages. J Mol Biol 299:27–51 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3729. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Aziz RK, Edwards RA, Taylor WW, Low DE, McGeer A, Kotb M. 2005. Mosaic prophages with horizontally acquired genes account for the emergence and diversification of the globally disseminated M1T1 clone of Streptococcus pyogenes. J Bacteriol 187:3311–3318 10.1128/JB.187.10.3311-3318.2005. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marciel AM, Kapur V, Musser JM. 1997. Molecular population genetic analysis of a Streptococcus pyogenes bacteriophage-encoded hyaluronidase gene: recombination contributes to allelic variation. Microb Pathog 22:209–217 10.1006/mpat.1996.9999. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mylvaganam H, Bjorvatn B, Hofstad T, Osland A. 2000. Molecular characterization and allelic distribution of the phage-mediated hyaluronidase genes hylP and hylP2 among group A streptococci from western Norway. Microb Pathog 29:145–153 10.1006/mpat.2000.0378. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Martinez-Fleites C, Smith NL, Turkenburg JP, Black GW, Taylor EJ. 2009. Structures of two truncated phage-tail hyaluronate lyases from Streptococcus pyogenes serotype M1. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 65:963–966 10.1107/S1744309109032813. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Holden MT, Heather Z, Paillot R, Steward KF, Webb K, Ainslie F, Jourdan T, Bason NC, Holroyd NE, Mungall K, Quail MA, Sanders M, Simmonds M, Willey D, Brooks K, Aanensen DM, Spratt BG, Jolley KA, Maiden MC, Kehoe M, Chanter N, Bentley SD, Robinson C, Maskell DJ, Parkhill J, Waller AS. 2009. Genomic evidence for the evolution of Streptococcus equi: host restriction, increased virulence, and genetic exchange with human pathogens. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000346 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000346. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bai Q, Zhang W, Yang Y, Tang F, Nguyen X, Liu G, Lu C. 2013. Characterization and genome sequencing of a novel bacteriophage infecting Streptococcus agalactiae with high similarity to a phage from Streptococcus pyogenes. Arch Virol 158:1733–1741 10.1007/s00705-013-1667-x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Obregón V, García JL, García E, López R, García P. 2003. Genome organization and molecular analysis of the temperate bacteriophage MM1 of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol 185:2362–2368 10.1128/JB.185.7.2362-2368.2003. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Siboo IR, Bensing BA, Sullam PM. 2003. Genomic organization and molecular characterization of SM1, a temperate bacteriophage of Streptococcus mitis. J Bacteriol 185:6968–6975 10.1128/JB.185.23.6968-6975.2003. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.van Sinderen D, Karsens H, Kok J, Terpstra P, Ruiters MHJ, Venema G, Nauta A. 1996. Sequence analysis and molecular characterization of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage r1t. Mol Microbiol 19:1343–1355 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02478.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Venturini C, Ong CL, Gillen CM, Ben-Zakour NL, Maamary PG, Nizet V, Beatson SA, Walker MJ. 2013. Acquisition of the Sda1-encoding bacteriophage does not enhance virulence of the serotype M1 Streptococcus pyogenes strain SF370. Infect Immun 81:2062–2069 10.1128/IAI.00192-13. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Anbalagan S, Chaussee MS. 2013. Transcriptional regulation of a bacteriophage encoded extracellular DNase (Spd-3) by Rgg in Streptococcus pyogenes. PLoS One 8:e61312 10.1371/journal.pone.0061312. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]