Abstract

In this study, boron nitride nanotubes (BNNTs) were utilized as covering and reinforcing materials owing to their extraordinary insulation and extremely high hydrophobicity. The gas–liquid–solid annealing process was used to manufacture the BNNT stainless-steel filter, with a 120 mesh stainless steel filter serving as the substrate and B2O3 as the raw material. Scanning electron microscopy showed that the average diameter of the nanotubes was 0.40 μm. The BNNTs were bamboo shaped, and the BNNT stainless-steel filter was superhydrophobic, with a water contact angle was 150.49°. The materials demonstrated good separation performance, as indicated by the separation results obtained under four different test conditions (0 and 0.3 MPa, 3 and 10 mL/min). The solid–liquid separation effect of the BNNT stainless-steel filter was better than that of the Teflon filter. In oil–water separation experiments with varying water contents (1.2 and 5.8 wt%), the BNNT stainless-steel filter was more hydrophobic. Based on the results, the role of the hydrodynamic method in the separation of two superhydrophobic materials is discussed. The method introduced in this study can serve as a reference for the application of other filtration separation technologies. Furthermore, the superior separation performance of the superhydrophobic BNNT stainless-steel filter may enable the quick, effective, and continuous collection of water contaminated with oil, giving it a wide range of potential applications.

Keywords: Superhydrophobic materials, Oil-water separation, Solid-liquid separation, Filtration ratio, Boron nitride nanotubes

1. Introduction

With their arrangement of hollow carbon atoms and unique mechanical, optical, and electronic properties [1,2], carbon nanotubes have emerged as promising nanomaterials in international nanotechnology since their discovery by Iijima [3] in 1991. Owing to their structural similarities, carbon (C) and boron nitride (BN) nanotubes have benefits that are comparable or superior to one-dimensional nanomaterials [4]. These advantages include good resistance to high-temperature oxidation [5], excellent superhydrophobicity, stable insulation properties [6,7], and good thermal conductivity [8,9]. As a result, BN nanotubes (BNNTs) have been extensively studied. Arc discharge, laser ablation, and carbon nanotube replacement reaction methods have been applied to manufacture BNNTs [7,[10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]]. Furthermore, the morphological features and processes of nanotube nucleation [19,20] and development have been examined [21,22].

Nonetheless, few conclusions about the superhydrophobicity of BNNTs have been made. Pakdel et al. [23] prepared BN coatings at 700 °C using thermochemical vapor deposition. With a contact angle (CA) greater than 150°, the BN coatings exhibited controlled hydrophobicities, ranging from partial hydrophilicity to superhydrophobicity. Additionally, at higher synthesis temperatures, the hydrophobicity of BN coatings has been reported to be independent of the pH of the water. Lee et al. [24] proposed a straightforward and workable method to enhance the desalination performance by incorporating two-dimensional BN nanosheets into poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) (PVDF-co-HFP) electrospun nanofiber membranes (BN-PH). This strategy can improve the performance and stability of seawater desalination systems. Excellent salt rejection (99.99 %) and consistent water vapor flux (18 LMH) are two advantages of the BN-PH membrane. Although the thermal conductivity and crystallinity of the membrane were lowered, BNNS addition enhanced the hydrophobicity, anti-wetting, and long-term stability of the membrane.

Moreover, to improve the industrial application of BN nanostructures, researchers have begun to study the properties of the material itself [[25], [26], [27], [28]]. Abbas [29] et al. presented a straightforward procedure for creating 2D BN hierarchical nanostructures using boric acid (H3BO3) and hexamethylenetetramine (C6H12N4) as the initial reactants. They discovered that by appropriately modifying the growth settings, the size, shape, and thickness of the BN QDs could be varied to provide a variety of wettability characteristics. 2D BN nanostructures exhibited superhydrophobic characteristics (CA = 155°) when the BN quantum dot thickness was <5 nm. Moreover, to improve the industrial application of BN nanostructures, researchers have begun to study the properties of the material itself [[25], [26], [27], [28]]. To remove or collect contaminants from polluted water, Zhang et al. fabricated novel, efficient, and low-cost Ag@wood composites [30], porous lignocellulosic nanofiber composites [31], and specific membranes by loading polypyrrole/silver nanoparticles (PPy/Ag NPs) onto spandex fabrics at different stages [32]. These materials solve the issue of the removal and collection of oil contaminants from different water/oil mixtures and have potential in environmental remediation.

We have previously conducted studies [[33], [34], [35]], and Zhang et al. [36] successfully prepared BNNTs with superhydrophobic properties using a gas–liquid–solid annealing method and studied the related properties of BNNTs. Li [34] was the first to create BNNTs in the laboratory by ball milling and annealing, and then examined the shape of the prepared BNNTs as well as the different types of nucleation catalytic materials. Based on this work, Li [35] synthesized a large number of BN nanoparticles using a high-temperature (1200 °C) ball-milling annealing process using boron oxide as a raw material.

However, most laboratories use the density difference between water and oil or differences in their chemical properties to design a basic static test device. The principle of gravity sedimentation or other physical and chemical reactions are harnessed to remove impurities or filter and separate water and oil [[37], [38], [39]]. This allows laboratories to test the filtration performances of superhydrophobic materials. Oil and water are mainly separated using gravity, centrifugation, electric, adsorption, and air-flotation separation. In the laboratory, attention is often paid to the simple experimental device and fixed separation conditions to explain the excellent separation performance of the materials. However, this process often ignores the complexity of the oil–water separation conditions required in industrial fields, which includes the proportion of the oil–water mixture, density difference, temperature, pressure, separation efficiency, and continuity of the separation process.

In this study, BNNTs were grown on the surface of a 120-mesh 304 stainless steel filter in a special corundum tube at 1250 °C using the gas–liquid–solid annealing method and inexpensive, easily obtained B2O3 as the raw material. This process followed the laboratory superhydrophobic BNNT stainless-steel filter preparation method. A filtration device was constructed to more comprehensively test the filtration performance of the prepared BNNT stainless-steel filter. The variation in the oil–water filtration and impurity filtration performance of a BN stainless-steel filter with respect to the pressure drop and flow rate was analyzed. The effect of the BNNT surface layer on filtration performance is discussed.

2. Experimental

2.1. Fabrication of the superhydrophobic surface

First, 99.9 % pure B2O3 powder was ball milled for 100 h at 450 rpm in a high-energy ball mill under the protection of a high-purity N2 atmosphere. Micron-sized B2O3 powder with a diameter of 1∼30 μm and ultrafine nanosized B powder with a diameter of 0.2–0.3 μm were obtained under the experimental conditions, using a ball-to-material ratio of approximately 20:1. The spherical tank was composed of stainless steel, and each steel ball had an average diameter of ≈6 mm. Next, the agate body was filled with B2O3 at a mass ratio of 4:1 and ground for 30–40 min. The combined raw materials were thinly spread in a porcelain boat made of ventilated alumina. Finally, the edge of the porcelain boat was secured to a stainless-steel filter with a 120 mesh. To set the temperature range for annealing, the raw material-covered porcelain boat was gradually pushed into a tube annealing furnace. To remove the air in the furnace tube, the inside of the tube furnace was washed with ammonia for 5–10 min before heating, until no obvious bubbles remained in the water bottle that absorbed excess ammonia. The entire BNNT growth reaction was conducted in an atmosphere of high-purity NH3. Owing to the unstable reaction, the NH3 gas flow rate was 40 mL/min when the tube furnace temperature rose from 500 °C to 1250 °C. The NH3 gas flow rate was maintained in the range of 40–45 mL/min during the annealing stage when the temperature reached 1250 °C, and the holding period was 2 h. When the temperature dropped to 500 °C, the NH3 gas flow was stopped, and N2 gas was reintroduced to allow as much of the remaining NH3 gas in the tube furnace as possible into the recovery bottle, which was filled with liquid water. The annealing time was 6 h; previous studies have reported the preparation method in detail [36].

Under high-temperature conditions, the possible chemical reactions of boron oxide precursors in an ammonia atmosphere are as follows:

| NH3(g)→N2(g) + H2(g) | (1) |

| B2O3(s)+3H2(g)→2B(s)+3H2O(g) | (2) |

| 2B(g) + N2(g)→2BN(s) | (3) |

When heated, NH3 progressively breaks down to produce H2 and N2, as shown in Eq. (1). H2 is highly reducible. The reduction reaction between H2 and B2O3 proceeded as the temperature increased, decreasing B2O3 to B and H2O, as shown in Eq. (2). As the nitrogen source in the reaction, N2 reacts with B with high activity at high temperatures in the presence of iron catalysts to form BN, as shown in Eq. (3).

2.2. Characterization

Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM; S4800) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM; JEM-2100Plus) were used to observe the surface morphology of the samples (Fig. 1 a–d). Fig. 1a shows the macroscopic surface of the BNNT stainless-steel filter annealed at 1250 °C, which reveals that the resultant material is fibrous. These fibrous materials are several microns long and range in diameter from a few dozen to several hundred nanometers. The macroscopic surface exhibited white matter, and the tip of the nanotube contained a few tiny particles. This is because the stainless-steel mesh of the tube furnace was at the front end of the NH3 inflow. At 1250 °C, the metal droplets on the stainless-steel mesh surface reacted completely with NH3, producing a significant amount of white flocculent material. Given that the BNNTs are white, it follows that these white materials are the intended products. The SEM images in Fig. 1b–d shows that many nanotubes grew densely on the surface of the stainless-steel mesh. These nanotubes have an average diameter of 0.40 μm and resemble bamboo shoots. An optical contact-angle measuring instrument (JC2000D1, Zhongchen, Shanghai, China) was used to measure the contact angle at 150.49° [36].

Fig. 1.

Surface (a) and SEM (b–d) images of BNNT-modified stainless-steel filter after annealing at 1250 °C (SEM images of the as-synthesized products and static contact angle of BNNT stainless-steel filter at a contact angle of 150.49°, respectively).

2.3. Filtration performance experiment

2.3.1. Filtration performance experimental setup

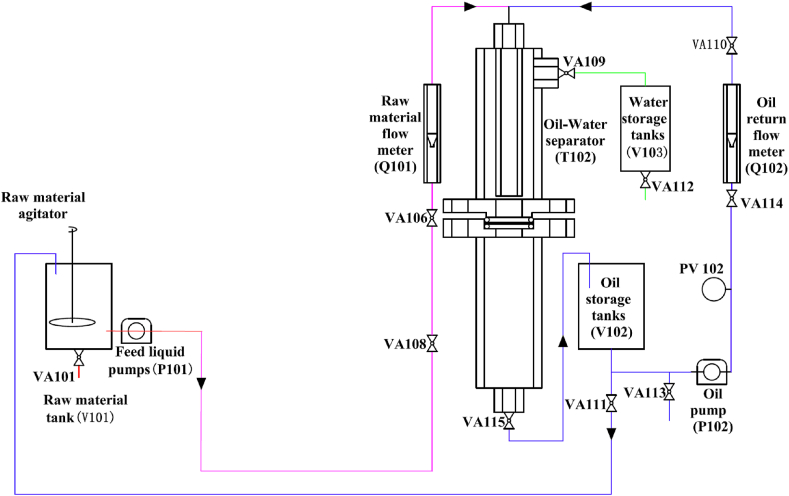

Fig. 2 shows a diagram of the device used to test the oil–water separation performance of the BNNT stainless-steel filter, which features a two-stage separator in series with a bottom inlet and bottom outlet in order. The red line represents the solid–liquid separation system, the blue line represents the oil–water separation system, and the yellow and pink lines represent the series path.

-

(1)

Solid-liquid separation device circuit

Fig. 2.

Schematic of oil-water separation performance test system.

In the process of testing the oil–water separation performance of the BNNT stainless-steel filter, a solid–liquid separation system was also added to the device to study the ability of the filter to intercept impurities. Before the start of the experiment, the target filter was cut into a circular sheet with a diameter of ≈30 mm, which was installed in the middle of a solid–liquid separator (T101) and an oil–water separator (T102). To prevent the gap from affecting the experimental performance, O-rings were installed on the top and bottom of the circular sheet before installation and finally connected by screws. Before the solid–liquid separation experiment, a solid–liquid mixture containing a certain amount of impurities was configured, and the solid–liquid mixture to be separated was stored in a raw material liquid tank (V101) and maintained by a raw material liquid agitator. Valves VA103, VA104, and VA102 were opened, and all other valves were closed to ensure normal operation of the solid–liquid separation pipeline. Starting with the feed liquid pump (P101), the solid–liquid mixture flows out from the feed liquid tank (V101) through valve VA104, enters the solid–liquid separator (T101) for separation, and then returns to the feed liquid tank (V101) through VA102. The separated impurities were collected and weighed through valve VA105, and the related calculations were performed. After the solid–liquid separation experiment, the sheet material was removed from the T101 component, valve VA101 was opened, and the remaining solid–liquid raw materials were introduced into a recovery bottle using a plastic hose for unified treatment. The process flow of the solid–liquid separation system is illustrated in Fig. 3.

-

(2)

Liquid-liquid separation device circuit

Fig. 3.

Flow chart of solid-liquid separation system.

Oil–water separation is the main function of the device, effectively separating aqueous mixtures containing a certain concentration of oil and water.

Before the start of the experiment, a mixture of water and a certain concentration of oil was configured; the oil–water mixture to be separated was stored in the raw material liquid tank (V101), and the solid–liquid mixture was kept uniform using a raw material liquid stirrer. To ensure that the oil–water separation pipeline operated normally, valves VA106, VA108, VA109, VA112, and VA115 were used to close the other valves in the system. When the feed liquid pump (V101) was turned on, the oil–water mixture flowed out of the feed liquid pump (V101) and into the feed liquid flowmeter (Q101) through valves VA108 and VA106, and then into the oil–water separator (T102). After the oil–water mixture was separated by the hydrophobic target material, it was discharged into the oil tank (V102) at the bottom of the oil–water separator (T102) through valve VA115, and the separated water was discharged into the water storage tank (V103) from the upper part of the oil–water separator (T102) through valve VA112. To study the circulation performance of the target separation material for the oil–water mixture, using the same separation pipeline as described above, valve VA111 was opened so that the oil in the oil storage tank flowed back into the raw material liquid tank (V101). The oil pump (P102) and valves VA114 and VA110 were opened. The oil–water mixture to be separated by circulation flowed out the oil pump (P102) and into the oil–water separator (T102) through the oil return flow meter (Q102) pipeline, storing the separated water and oil in the water-storage tank (V103) and oil-storage tank (V102) using valves VA109 and VA115, respectively. The flow rates of the feed liquid flow meter (Q101) and oil return flow meter (Q102) were adjusted using valves VA106 and VA114, respectively. After the oil–water separation experiment, the sheet material was removed from the T102 parts, valves VA101 and VA112 were opened, and the waste liquid was introduced into the recovery bottle for unified treatment. The process flow of the oil–water separation system is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Flow chart of oil-water separation system.

The purpose of the series separation of the solid–liquid and oil–water separation systems was to investigate whether the performance of the BN stainless-steel filter changed as the mixed liquid composition increased. The oil–water separator (T102) and solid–liquid separator (T101) were connected by valves VA104 and VA107, and these two separators formed the foundation of the series separation. The solid–oil–liquid mixture to be separated was kept in the raw material liquid tank (V101), and a certain concentration was prepared before the start of the experiment. Initially, the solid–oil separation process proceeded according to the operating sequence of the solid–oil separation system. VA105 was responsible for collecting and discharging the separated solid–liquid pollutants. A small amount of the oil mixture was delivered into the upper portion of T101 owing to the possibility of the modified BN material on the filter being destroyed during separate separations of the solid impurities. For re-separation, the VA107 pipeline entered the oil–water separator (T102). The liquid entered the water-storage tank (V101), and the separated oil entered the oil-storage tank (V102). Finally, the waste liquid underwent consistent treatment, and the experimental data were documented. Fig. 5 shows the experimental apparatus based on a process flow diagram.

Fig. 5.

Separation device.

In the experiment on solid–liquid separation and oil–water separation, we conducted comparison tests using a commercial hydrophobic Teflon (TFL) 120 mesh and a homemade hydrophobic BNNT stainless-steel filter (120 mesh BN).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Solid-liquid separation performance

Solid particles are one of the most prevalent oil contaminants. Iron chips, metal rust chips, and other particle contaminants have been found in oil after long-term use, where Fe2O3 is one of the most prevalent impurities. Therefore, in this study, Fe2O3 was added to fuel oil as a contaminant and then separated. First, Fe2O3 (99.99 % pure) was processed in a high-energy stainless-steel ball mill under an N2 atmosphere for 0.5 h. The ball mill speed was 450 rpm, the steel ball diameter was 6 mm, and the ball-to-material ratio was 20:1. After ball-milling and processing for 30 min in an agate mortar, the Fe2O3 powder was sealed in a vacuum box in a fresh bag. Then, 50 g of the ground Fe2O3 powder was added to 8 L of fuel oil, and the oil that needed to be separated was mechanically agitated for 5 h at 200 rpm to ensure that the contaminants were dispersed throughout. The operating sequence of the solid–liquid separation system was then used to conduct the impurity separation experiments.

This study aimed to examine the oil conditions before and after the separation of solid impurities using a BNNT stainless-steel filter. To achieve this, 24 mL samples were randomly taken from the oil storage tank at various stages using a calibrated rubber head dropper, and the solid impurities were separated using various separation materials. A particle detector (MP Filtri Spa LPA2) was used to detect the number of particles in the collected samples, which were then categorized and numbered. Using Eq. (4), the separation efficiency of the solid impurities was calculated.

| (4) |

In Eq. (4) is the solid-liquid separation efficiency, is the number of solid impurity particles prior to separation, and is the number of solid impurity particles following separation. Hydrophobic materials—a commercial TFL filter and stainless-steel filter altered with BNNTs—were tested at 0 MPa and 10 MPa. Solid–liquid separation experiments were conducted under four different conditions at 3 mL/min and 10 mL/min. Fig. 6 illustrates the separation effect.

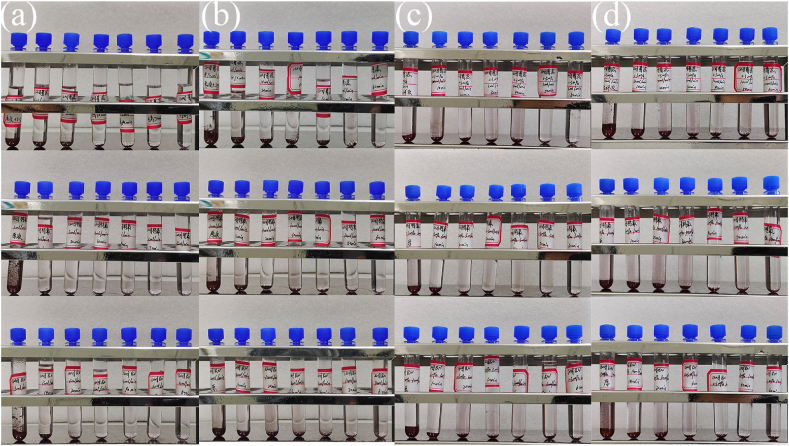

Fig. 6.

Schematic showing the products of solid–liquid separation at (a) 0 MPa, 3 mL/min; (b) 0 MPa, 10 mL/min; (c) 0.3 MPa, 3 mL/min; (d) 0.3 MPa, 10 mL/min; (from left to right: initial sample solution, solutions collected after filtration for 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 min; from top to bottom: 120 mesh filter, TFL filter, BNNT stainless-steel filter.).

Fig. 6 shows a comparison of the solutions obtained using a stainless-steel filter mesh modified by BNNTs and a TFL filter mesh at varying pressures and flow rates over time before and after oil purification. As seen in Fig. 1, Fig. 6 under different circumstances, both filters exhibit strong solid–liquid separation capabilities; (2) for a stainless-steel filter enhanced with BNNTs after 30 min of filtration at 0 MPa and 3 mL/min, hardly any Fe3O2 powder is visible in the test tube. After 30–60 min of filtration, the oil in the samples was essentially clear. TFL and stainless-steel filters enhanced with BNNTs have comparable filtration effects and both exhibit good separation performance. Owing to the increased flow rate at 0 MPa and 10 mL/min, filtration was less effective than separation at 0 mL/min, and a small amount of Fe3O2 powder remained at the bottom of the sample tube. The TFL filter outperformed the BN filter. The separation performance of the two filters rapidly diminished as the pressure increased to 0.3 MPa (flow rate of 3 mL/min). Many pollutants at the bottom of the BN filter were partially removed during the first 50 min of filtration. A small amount of contaminant remained in the sample tube after 60 min of filtration, but the oil gradually became clear. The filtration was not complete, even though in the first 50 min, the contaminants in the TFL filter sample tube were marginally less than those in the BN filter sample tube. Some impurities were deposited, and the sample resembled that of the BN filter sample tube after 60 min of filtration. The filtration performance of both filters decreased further at 0.3 MPa and 10 mL/min. However, after 40 min, the filtration performance of the BN filter was marginally superior to that of the TFL filter. Furthermore, both samples still contained some pollutants after the 60 min filtration process, but the initial unclean oil had been cleaned and clarified.

The upper and middle layers of the sample bottle were removed to better compare the filters of the two materials, and a particle detector (MP Filtri Spa LPA2) was used to determine the number of particles. Table 1, Table 2 display the detection data for the stock and sample solutions.

Table 1.

Raw liquid particle pollution data.

| μm (c) | average value |

|---|---|

| 4 | 67707 |

| 6 | 26556 |

| 14 | 2256 |

| 21 | 442 |

| 25 | 210 |

| 38 | 160 |

| 50 | 132 |

| 70 | 103 |

Table 2.

Pollution data of particles to be separated.

| μm (c) | average value |

|---|---|

| 4 | 6936037 |

| 6 | 2778410 |

| 14 | 164256 |

| 21 | 140805 |

| 25 | 55636 |

| 38 | 18878 |

| 50 | 7432 |

| 70 | 5972 |

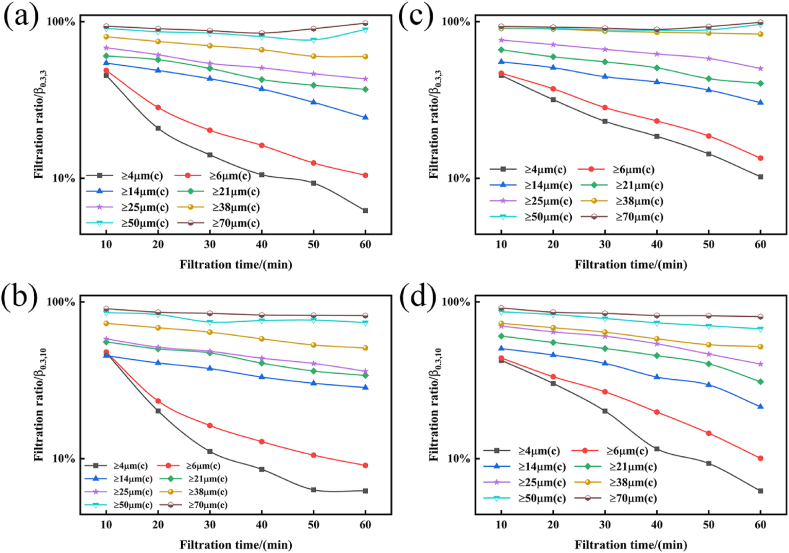

Fig. 7 illustrates the relationship between the time in four states and the filtration ratios of the TFL and BN filters.

Fig. 7.

Filtration ratio diagrams: (a) 0 MPa, 3 mL/min TFL filter; (b) 0 MPa, 3 mL/min BN filter; (c) 0 MPa, 10 mL/min TFL filter; and (d) 0 MPa, 10 mL/min BN filter.

The results presented in Fig. 9 indicate that the filtration ratios of the TFL and BN filters gradually decreased over time at 0 MPa and 3 mL/min. After 60 min of filtration, the percentage of 4 μm (c) particles filtered by the TFL filter dropped from 55.34 % to 37 %, while the percentage of 4 μm (c) particles filtered by the BN filter dropped from 50.85 % to 33.12 %. During solid–liquid separation and filtration, the percentage of 6 μm (c) particles dropped from 58.54 % to 45.09 % after 60 min using the TFL filter, while that of the BN filter dropped from 53.4 % to 38.45 %. The percentage of 14 μm (c) particle pollutants filtered by the TFL filter dropped from 67.38 % to 51.56 % after 60 min of solid–liquid separation, while that of the BN filter fell from 70.25 % to 63.56 %. The percentage of 21 μm (c) particles captured by the TFL filter decreased from 79 % to 58.96 % after 60 min, whereas that of the BN filter decreased from 79 % to 72.66 %. In addition, 80.11 % of 25 μm (c) particle pollutants were initially captured by the TFL filter, falling to 64 % after 60 min; for the BN filter, the percentage dropped from 90.11 % to 78.55 %. The TFL filter's initial filtering ratios for 38 μm (c), 50 μm (c), and 70 μm (c) particle pollutants were 97.3 %, 98.5 %, and 97.3 %, respectively, where all particles were captured in less than 20 min. For 38 μm (c), 50 μm (c), and 70 μm (c) particle pollution, the initial filtering ratios of the BN filters were 96.4 %, 97.34 %, and 98 %, respectively. Similar to the TFL filter, the BN filter was analyzed after filtration for 20 min. The filtration ratios of the TFL and BN filters decreased with increasing time at 0 MPa and 10 mL/min. The filtration ratio of the 4 μm particles (c) by the TFL filter dropped from 54 % to 25.91 % after 60 min, while the ratio dropped from 49.34 % to 10.22 % for the BN filter. The 6 μm (c) filtration ratio for the TFL filter dropped from 58.54 % to 31.11 % after 60 min, while that for the BN filter dropped from 53.85 % to 20.45 %. The filtering efficiency of the 14 μm (c) particle pollutants dropped from 66.38 % to 35.65 % after 60 min using the TFL filter, while BN filter's efficiency dropped from 65.42 % to 40.41 %. The efficiency of the TFL filter decreased from 78.11 % to 47.96 % after 60 min for pollutants measuring 21 μm (c), while that of the BN filter decreased from 71.54 % to 48.96 %. The TFL filter's filtration ratio for 25 μm (c) particle pollutants dropped from 79.56 % to 64 % after 60 min, while the BN filter's filtration ratio dropped from 86.31 % to 60.22 %. For 38 μm (c), 50 μm (c), and 70 μm (c) particle pollutants, the initial TFL filter filtration ratios were 95.3 %, 97.3 %, and 98 %, respectively. Following solid–liquid separation for 50–60 min, the particle contaminants were captured. For 38 μm (c), 50 μm (c), and 70 μm (c) particle pollutants, the initial filtering ratios of the BN filters were 94.3 %, 92.2 %, and 94.3 %, respectively. Particulate pollutants were collected after 60 min of separation.

Fig. 9.

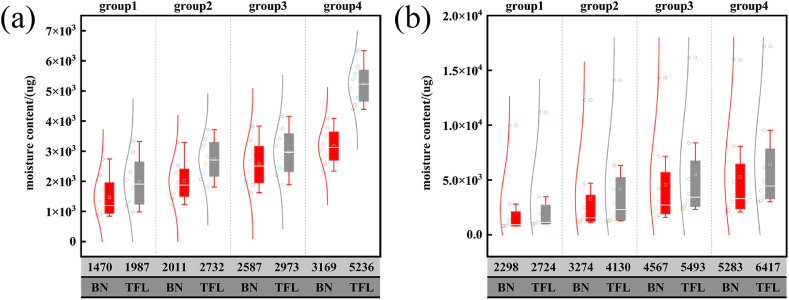

Comparison of BN and TFL filter oil–water separation: (a) 1.2 wt% and (b) 5.83 wt%.

This data shows that at 0 MPa, the filtration performances of the TFL and BN filters were essentially the same. The TFL filter, particularly for 4 μm (c) and 7 μm (c) particles, keeps the filtering ratio of contaminants with varying particle sizes relatively constant. The TFL filter outperformed the BN filter in terms of small-particle pollution filtration. This could be because the BNNTs were microshed during the filtering process, causing secondary contamination of the oil and a decline in its filtration efficiency. Nevertheless, BN retained good filtration performance for large-scale particle contaminants, marginally outperforming the TFL filter during the separation process.

The filtration ratio curves for the TFL and BN filters at 0.3 MPa, 3 mL/min, and 10 mL/min for pollutants of varying particle sizes after 60 min of separation are shown in Fig. 8. Based on the graph, it is evident that for 4 μm (c) particle pollution, the TFL filter's filtration ratio dropped from 45.34 % to 6.22 %, and the BN filter's filtration ratio dropped from 45.68 % to 10.23 % at 0.3 MPa and 3 mL/min. The TFL filter's filtration ratio dropped from 48.9 % to 10.44 %, and the BN filter's filtration ratio dropped from 48.3 % to 13.45 % for 6 μm (c) particle pollutants. After 60 min of separation, the TFL filter's ability to filter 14 μm (c) particle pollutants dropped to 24.37 %, while the BN filter's filtration efficiency dropped from 55.38 % to 30.41 %. For 21 μm (c) particle contaminants, the TFL and BN filters' filtration ratios dropped from 65.15 % to 40.35 %, respectively. After 60 min of separation, the TFL filter's filtration ratio dropped from 68.11 % to 43.12 % for the separation of 25 μm (c) particle contaminants, while the BN filter's filtration ratio reduced from 76.32 % to 50.22 %. The TFL filter's filtration ratio dropped from 80.13 % to 59.85 % for 38 μm (c) particle pollutants, while the BN filter's filtration ratio dropped from 90.43 % to 83.21 %. Both filters demonstrated an exceptional filtration ratio of >90 % for particle pollutants measuring 50 μm (c) and 70 μm (c).

Fig. 8.

Filtration ratio diagrams for (a) TFL filter (0.3 MPa, 3 mL/min), (b) BN filter (0.3 MPa, 3 mL/min), (c) TFL filter (0.3 MPa, 10 mL/min), and (d) BN filter.

At 0.3 MPa and 10 mL/min, the TFL filter's filtration ratio dropped from 47.34 % to 6.22 %, while the BN filter's filtration ratio dropped from 42.23 % to 7.34 % for 4 μm (c) particle pollutants. The TFL filter's filtration ratio decreased from 47.85 % to 9.04 %, and the BN filter's filtration ratio decreased from 43.85 % to 10.04 % for 6 μm (c) particle pollutants. The data from the separation test for the particulate pollutants measuring 14 μm (c), 21 μm (c), 25 μm (c), 38 μm (c), 50 μm (c), and 70 μm (c) indicate that the TFL filter's final filtration ratio is comparable to that of the BN filter. However, the change in the curve indicated that the filtration ratio of the particulate matter on the BN filter was higher than that on the TFL filter, and the ratio remained steady for the first 40 min. TFL filters are more durable than BN filters. The filtration ratio of the BN filter is noticeably lower than that of the TFL filter at this point in the separation process, as can be observed in the 50–60 min stage.

The filtration ratios of the TFL and BN filters at varying pressure drops and flow rates were deduced from the data analysis. The TFL filter's remarkable anti-scouring ability is demonstrated by the fact that, at 0 MPa, the filtration ratio remains relatively constant as the flow rate varies. The filtration ratio of the stainless-steel filter with BNNTs changed significantly when the flow rate was increased below 0 MPa. The TFL filter outperforms the BN filter in terms of separation efficiency for both 4 μm (c) and 6 μm (c) particles. However, for large-sized particle pollutants, the filtration ratio of the TFL filter was marginally higher than that of the BNNT stainless-steel filter. At 0.3 MPa, the filtration performances of the two filters exhibited different trends with increasing pressure. At a flow rate of 3 mL/min, the BNNT stainless steel filter showed a slower downward trend than the TFL filter, and the filtration of particulate pollutants of 38 μm (c), 50 μm (c), 70 μm (c) and other sizes was close to 99 %. For the BNNT stainless steel filter, the trend for the 14 μm (c), 21 μm (c), 25 μm (c), 38 μm (c), 50 μm (c), and 70 μm (c) particles is comparatively flat at a flow rate of 10 mL/min, 0–30 min separation stage. However, compared with the TFL filters, the filtration of the stainless-steel BNNT filter was steeper during the 30–60 min stage. This might be the result of BNNT shedding over an extended period of time at high pressure and high flow rate. The total solid–liquid separation performance of the BNNT stainless-steel filter was considerably good, as indicated by the data analysis. When it comes to separating small-sized impurities at high pressures and low flow rates, it outperforms TFL filters. The field of solid–liquid separation may benefit from the use of BNNT stainless-steel filters.

3.2. Liquid-liquid separation performance

The BNNT-modified stainless-steel filter mesh was sliced into ≈30 mm thick sheets and installed in an oil–water separator (T102). The oil–water separation experiment was conducted in accordance with the operating procedure of the system using a mixture of reddish aerospace hydraulic oil (GJB 1177A-2013) and deionized water for visual observation.

This study examined the effects of the initial water content (1.2 and 5.8 wt%), pressure (0 and 0.3 MPa), and flow rate (3 and 10 mL/min) on the oil–water separation performance for the same separation duration to test the filter material prepared in the laboratory. The oil–water separation efficiency of the two test materials can be quantitatively described by their separation performance using Eq. (5).

| (5) |

In Eq. (5), the initial water content in the oil–water combination (μg) is represented by , the initial water content in the mixture after separation by , and the water removal rate in the oil sample by . Oil–water separation experiments were conducted on two hydrophobic materials: a 120 mesh BNNT stainless-steel filter (BN) and a 120 mesh commercial TFL filter. Following the separation of the target oil–water mixture by the filter, 1 mL of the separated oil was analyzed using a micro-moisture meter (HF–102B), and pertinent data were recorded. Following the initial test, the separation device's VA111 valve was opened once more, allowing the separated oil (V102) to flow into the crude oil tank (V101) for the second oil–water separation, while the pertinent data were collected. The measured values after eight operation cycles are presented in Fig. 9.

The two types of superhydrophobic filter screens shown in Fig. 9 were used to separate 1.2 wt% and 5.83 wt% oil from water. The four test groups were as follows: 0 MPa, 3 mL/min (group 1); 0 MPa, 10 mL/min (group 2), 0.3 MPa, 3 mL/min (group 3), and 10 mL/min (group 4). The 1.2 wt% oil separation results show that in groups 1–4, there was a sizable oil–water separation gap between the TFL filter and BN filter. For groups 1 and 2, after eight separations, the average water content of the TFL filter was 1987 μg, 2732 μg, and the average water content of the BN filter was 1470 μg, 2011 μg. For the same pressure and varying flow rates, the water contents of the eight groups using the BN filter were lower than the TFL water contents. For groups 3 and 4, the filtration performance of the two filters was lower, and the water content of the oil after separation was continuously increased by the micro-moisture analyzer. It was also found that during the separation process of the two filters, under the same pressure, the slower the flow rate, the lower the water content after separation; at the same flow rate, the lower the pressure, the lower the water content after separation. This might be because when the oil–water mixture infiltrates the filter during the separation process, the amount of oil and water that passes through the filter increases owing to excessive pressure or excessive flow rate, causing a sharp drop in the time the oil–water mixture remains on the filter surface. Finally, some of the water in the oil–water mixture did not have time to wet the filter; as a result, it was washed through with a large amount of oil and then flowed into the oil pipe, lowering the separation performance of the two filters. Some of the water in the oil could still be separated by the filter, although the separation time increased. Both filters are better at removing water when the water content of the oil–water mixture is 5.83 wt%. The water contents of the oil after 8 separations by the TLF and BN filters were 791.12 μg and 979.32 μg, respectively, and the average masses of water removed were ≈2298 μg and 2724 μg, respectively, under 0 MPa and 3 mL/min (group 1). Both filters exhibited outstanding water removal capabilities. Following eight cycles of separation at 0 MPa and 10 mL/min (group 2), the water contents of the oil were 1123.1 μg and 1297.8 μg after filtration by the TFL and BN filters, respectively. According to the results, the BN filter had a better filtration performance. When the separation environment gradually deteriorated (0.3 MPa, 0.3 mL/min; 0.3 MPa, 10 mL/min), the separation performances of the two filters were affected to varying degrees. Under 0.3 MPa and 0.3 mL/min (group 3), the water contents of the oil after separation by the BN and TLF filters were 1771.2 μg and 2417.9 μg, respectively. Under 0.3 MPa and 10 mL/min (group 4), the water contents of the oil after separation by the BN and TLF filters were 2211.4 μg and 3112.2 μg, respectively. Comparing the separation performance of the filters for groups 1 and 2 vs 3 and 4, the water contents of the oil were higher for groups 3 and 4, so the water removal performances of the two filters in these groups were poorer. However, although the water removal performance of the BN filter gradually decreased under harsh experimental conditions, it can be seen from the box plot and normal distribution curve that the water removal capacity of the BN filter gradually reached equilibrium after 6–7 separations. The water content of the oil separated by the BN filter was greater than that separated by the TFL filter, and it can be seen from the normal distribution curve in the figure that the first water-removal capacity of the BN filter was much better than that of the TFL filter under the four conditions.

Afterwards, the oil–water separation data of the two filters were processed. The separation efficiencies of the two filters are shown in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Oil–water separation efficiency diagram of BN and TFL filter (1.2 wt%): (a) 0 MPa, 3 mL/min; (b) 0 MPa, 10 mL/min; (c) 0.3 MPa, 3 mL/min; and (d) 0.3 MPa, 10 mL/min.

According to the separation efficiencies of the two filters in Fig. 10, each filtration was effective in removing water under the four conditions for a water content of 1.2 wt%. The filtration efficiencies of the two filters decreased with increasing filtration time. The analysis revealed that under 0 MPa and 3 mL/min, the first water-removal rate of the BN filter was ≈72 %, and the first water-removal rate of the TFL filter was ≈66 %. After eight cycles of separation, the water content of the oil–water mixture separated by the BN filter was ≈858.3 μg, and the total water removal rate was 91.25 %. The water content of the oil–water mixture separated by the TLF filter was ≈1281.78 μg, and the total water removal rate was 86.94 %. The filtration effectiveness of the two filters was marginally lower at 0 MPa and 10 mL/min than it was at low-flow settings when the flow rate increased. The BN filter's initial water removal rate was 67 %, and the overall water removal rate was 87.27 %. The TFL filters had an initial water removal rate of 62.19 % and an overall water removal rate of 82.78 %. When the flow rate increased, the water removal performances of the two filters decreased. This may be because the speed of the oil–water mixture flushing the filter increased, and the separation time decreased. The emulsified and free water did not fully interact with the filter surface, and a large amount of oil was continuously rinsed and removed from the filter surface. The two filters were less effective in removing water when the flow rate increased; this could be because the oil–water mixture flushes the filter more quickly, and the filtration takes less time. A significant amount of the oil–water mixture was continually removed from the filter's surface because the emulsified and free water did not fully interact with the filter surface. Under 0.3 MPa and 3 mL/min, the initial water removal rate of the BN filter was 61.2 %, and the total water removal rate was 80.61 %. The initial water removal rate of the TFL filter was 56.67 %, and the total water removal rate was 75.27 %. Under 0.3 MPa and 10 mL/min, the initial water removal rate of the BN filter was 58.37 %, and the total water removal rate was 76.19 %. The initial water removal rate of the TFL filter was 35.45 %, and the total water removal rate was 50.2 %. Based on these data, it was discovered that while the water removal rates of the two filters rapidly decreased when the pressure and flow rate were increased, the BN filter's water removal rate still exceeded 70 %, which was significantly better than the TFL filter's water removal capabilities.

For the four sets of conditions of the oil–water mixture containing 5.8 wt% water, Fig. 11 shows the filtration efficiencies of the two types of filters. Altering the test conditions affected the separation efficiencies of the two filters. At 0 MPa and 3 mL/min, the first filtration efficiency of the BN filter was not only higher than that of the TFL filter, but also the water removal rate of the BN filter was higher than that of the TFL filter after eight cycles of separation. The total separation efficiencies of the BN and TFL filters were 98.5 % and 98.04 %, respectively. At a flow rate of 10 mL/min, the initial filtration performance of the BN filter was 75.4 %, which was higher than that of the TFL filter (71.7 %), and the final separation efficiency of the BN filter was slightly higher than that of the TFL filter. Under the conditions of 0.3 MPa and 3 mL/min or 10 mL/min, the separation performance of the two filters decreased; however, from the data analysis of the downward trend and final efficiency ratio, it was found that the overall separation efficiency of the BN filter was higher than that of the TFL filter.

Fig. 11.

BN and TFL filter oil–water (5.8 wt%) separation efficiency diagrams: (a) 0 MPa, 3 mL/min; (b) 0 MPa, 10 mL/min; (c) 0.3 MPa, 3 mL/min; and (d) 0.3 MPa, 10 mL/min.

The experimental results for the separation of oil–water mixtures containing 1.2 wt% and 5.8 wt% water were compared. It was discovered that when the water content of the oil increased, the ability of the two superhydrophobic filters to remove water increased. Even at 0.3 MPa, 3 mL/min and 0.3 MPa, 10 mL/min, the two types of filters were still able to retain over 90 % of their water removal rate. However, for an oil–water mixture with a water content of ≈1.2 wt%, the final water removal rates of the TFL filters were 50 %, and the water removal rate of the BN filter was 76.2 %. These experimental results demonstrate that both filters are effective in removing water from an oil–water mixture when the water content is high; however, the BN filter is more useful for removing micrograms of water. Thus, the BN filter has potential practical application and is better suited for removing water in harsh environments.

3.3. Oil-water separation mechanism

Fig. 12 illustrates the mechanism of the separation performance of the superhydrophobic BNNT stainless-steel filter used for oil–water separation.

Fig. 12.

Superhydrophobic BNNT stainless-steel filter oil–water separation diagram.

The pure h-BN structure is the building block of BNNTs, which are formed through constant adhesion and superposition. The densely packed superhydrophobic BNNTs create a uniform film layer that traps all droplets as the oil–water mixture passes through its surface. However, because BNNTs are lipophilic, oil can pass through the film they form and enter the stainless-steel filter, whereas countless droplets are continuously intercepted by the BNNTs on the stainless-steel surface to form larger water droplets, ultimately resulting in the separation of oil and water.

The data acquired for the oil–water and solid–liquid separation by the TFL filter and superhydrophobic BNNT stainless-steel filter were analyzed. In addition to the unique hydrophobicity of the material surface, the thickness and pore size of the separation material are also critical to the separation efficiency. Eq. (6) indicates that the separation flux correlated with the substrate's pore size, thickness, and fluid viscosity in accordance with the classical Hagen–Poiseuille fluid dynamics law [40,41].

| (6) |

where denotes the surface porosity of the substrate; is the surface pore radius; represents the pressure difference between the two ends of the fluid; represents the viscosity of the fluid; and is the total distance the fluid travels through the surface.

A more intuitive interpretation of Eq. (6) is that the separation flux in the separation process is proportional to the square of the pore radius of the substrate (R2) and inversely proportional to the thickness of the substrate (L). Because the mesh number of the TFL filter was the same as that of the 304 stainless-steel filter, the average pore size of the TFL filter was smaller than that of the BNNT stainless-steel filter, and the substrate thickness of the TFL filter was greater than that of the BNNT filter. Therefore, the separation performance of the BNNT stainless-steel filter was better than that of the TFL filter.

4. Conclusions

In summary, a gas–liquid–solid annealing process was used to easily and successfully manufacture BNNTs. According to the TEM data, the 120 stainless-steel mesh is coated with superhydrophobic BNNTs (CA = 150°). A simple separation apparatus was built to investigate the potential applications of the BNNT stainless-steel filters. Using the control-variable approach, the separation performances of a commercial TFL filter and the BNNT stainless-steel filter were assessed. The findings indicate that in the solid–liquid separation experiment, the filtration ratios of the BNNT stainless-steel filter for particle pollutants with sizes of 4 μm (c), 6 μm (c), 14 μm (c), 21 μm (c), 25 μm (c), 38 μm (c), 50 μm (c), and 70 μm (c) were 33.12 %, 38.45 %, 63.56 %, 72.66 %, 78.45 %, 100 %, 100 %, and 100 %, respectively. Under 0 MPa and 10 mL/min, the filtration ratios were 10.22 %, 20.45 %, 40.41 %, 48.96 %, 60.22 %, 100 %, 100 %, and 100 %, respectively; under 0.3 MPa and 3 mL/min, the filtration ratios were 10.23 %, 13.45 %, 30.41 %, 40.35 %, 50.22 %, 83.21 %, 96 % and 99 %, respectively; and under 0.3 MPa and 10 mL/min, the filtration ratios were 7.34 %, 10.04 %, 21.41 %, 30.96 %, 40.13 %, 51.85 %, 67.39 %, and 80.53 %, respectively. In the oil–water separation experiment, for groups 1–4, the water removal rates of the BNNT stainless-steel filter were 91.26 %, 88.51 %, 80.61 %, and 76.20 %, respectively, for a water content of 1.2 wt%, and 98.14 %, 96.63 %, 96.71 %, and 95.65 %, respectively, for a water content of 5.8 wt%. The BNNT stainless-steel filter performed exceptionally well, as indicated by the two sets of separation testing data. The BNNT stainless-steel filter exhibited superior solid–liquid and liquid–liquid separation performances compared with standard TFL filters when subjected to high pressure and high flow rates. These results demonstrate that the BNNT stainless-steel filters can be used for a wide range of filtration applications in challenging environments.

Data and code availability

Research-related data is not stored in publicly available repositories. Data will be made available on request. Please contact the author Zhang Lie, email: zhanglie826175118@163.com.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lie Zhang: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation. Yongbao Feng: Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis. Shuzhi Li: Software, Project administration, Investigation. Liang Li: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Bo Yuan: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Formal analysis.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who have helped us during the writing of this thesis.

References

- 1.Liew K.M., Kai M.F., Zhang L.-W. Carbon nanotube reinforced cementitious composites: an overview. Compos. Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016;91:301–323. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kai M.F., Zhang L.-W., Liew K.M. Carbon nanotube-geopolymer nanocomposites: a molecular dynamics study of the influence of interfacial chemical bonding upon the structural and mechanical properties. Carbon. 2020;161:772–783. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iijima S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature. 1991;354:56–58. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loiseau A., Willaime F., Demoncy N., et al. Boron nitride nanotubes. Carbon. 1998;36(5):743–752. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y., Pan Y., Yin D., et al. Investigations on microstructure and mechanical properties of boron nitride fiber using experimental and numerical methods. Mater. Today Commun. 2022;33 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng X., He Y., Fan Y., et al. Strengthening the mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of NiW coatings by PDA-functionalized h-BN nanosheets. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024;141 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng B., Chen J., Yang Y., et al. Fabrication of BN thin films by chemical vapor deposition on 4H–SiC (0001) single-crystalline surfaces. Vacuum. 2024;222 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y., Zou J., Campbell S.J., et al. Boron nitride nanotubes: pronounced resistance to oxidation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004;84(13):2430–2432. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Y., Fang R., Zhou Z., et al. Theoretical study on thermal conductivity of epoxy composites doped with boron nitride with multiple dimensions. Mater. Today Commun. 2024;38 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seo H.W., Bae S.Y., Park J., et al. Nitrogen-doped gallium phosphide nanowires. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2003;378:420–424. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu D.P., Sun X.S., Lee C.S., et al. Synthesis of boron nitride nanotubes by means of excimer laser ablation at high temperature. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998;72(16):1966–1968. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chopra N.G., Luyken R.J., Cherrey K., et al. Boron nitride nanotubes. Science. 1995;269(5226):966–967. doi: 10.1126/science.269.5226.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan S.D., Ding X.X., Huang Z.X., et al. Synthesis of BN nanobamboos and nanotubes from barium metaborate. J. Cryst. Growth. 2003;256(1–2):67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang C.C., Ding X.X., Huang X.T., et al. Effective growth of boron nitride nanotubes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2002;356(3–4):254–258. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han W., Bando Y., Kurashima K., et al. Synthesis of boron nitride nanotubes from carbon nanotubes by a substitution reaction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998;73(21):3085–3087. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golberg D., Bando Y. Springer US; Boston, MA: 2003. Electron Microscopy of Boron Nitride Nanotubes [M]//WANG Z L, HUI C. Electron Microscopy of Nanotubes; pp. 221–250. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y., Fitz Gerald J.D., Williams J.S., et al. Synthesis of boron nitride nanotubes at low temperatures using reactive ball milling [J] Chemical Physics Letters. 1999;299(3):260–264. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deepak F.L., Vinod C.P., Mukhopadhyay K., et al. Boron nitride nanotubes and nanowires. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2002;353(5–6):345–352. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y., Xu C., Xu B., et al. Chirality-activated mechanoluminescence from aggregation-induced emission enantiomers with high contrast mechanochromism and force-induced delayed fluorescence. Mater. Chem. Front. 2019;3(9):1800–1806. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang C.C., Bando Y., Sato T., et al. Uniform boron nitride coatings on silicon carbide nanowires. Adv. Mater. 2002;14(15):1046–+. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chadderton L.T., Chen Y. A model for the growth of bamboo and skeletal nanotubes: catalytic capillarity. J. Cryst. Growth. 2002;240(1–2):164–169. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Velazquez-Salazar J.J., Munoz-Sandoval E., Romo-Herrera J.M., et al. Synthesis and state of art characterization of BN bamboo-like nanotubes: evidence of a root growth mechanism catalyzed by Fe. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2005;416(4–6):342–348. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pakdel A., Zhi C.Y., Bando Y., et al. Boron nitride nanosheet coatings with controllable water repellency. ACS Nano. 2011;5(8):6507–6515. doi: 10.1021/nn201838w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee D., Woo Y.C., Park K.H., et al. Polyvinylidene fluoride phase design by two-dimensional boron nitride enables enhanced performance and stability for seawater desalination. J. Membr. Sci. 2020:598. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng Y.H., Xia M.J., Cheng Y., et al. Direct observation of metastable face-centered cubic Sb2Te3 crystal. Nano Res. 2016;9(11):3453–3462. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qi R.S., Li N., Du J.L., et al. Four-dimensional vibrational spectroscopy for nanoscale mapping of phonon dispersion in BN nanotubes. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21452-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu L., Park J., Siegel D.A., et al. Heteroepitaxial growth of two-dimensional hexagonal boron nitride templated by graphene edges. Science. 2014;343(6167):163–167. doi: 10.1126/science.1246137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y.F., Zhang X.W., Wang J.H., et al. Engineering interlayer electron-phonon coupling in WS2/BN heterostructures. Nano Lett. 2022;22(7):2725–2733. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c04598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abbas S., Abbas A., Liu Z.Y., et al. The two-dimensional boron nitride hierarchical nanostructures: controllable synthesis and superhydrophobicity. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020;240 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang M., Zhou N.Y., Shi Y.H., et al. Construction of antibacterial, superwetting, catalytic, and porous lignocellulosic nanofibril composites for wastewater purification. Adv. Mater. Interfac. 2022;9(34) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du X.L., Shi L., Pang J.Y., et al. Fabrication of superwetting and antimicrobial wood-based mesoporous composite decorated with silver nanoparticles for purifying the polluted-water with oils, dyes and bacteria. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022;10(2) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang M., Wang C.Y., Ma Y.H., et al. Fabrication of superwetting, antimicrobial and conductive fibrous membranes for removing/collecting oil contaminants. RSC Adv. 2020;10(36):21636–21642. doi: 10.1039/d0ra02704a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y.J., Wang X.R., Wang J., et al. A simple method for the synthesis of a coral-like boron nitride micro-/nanostructure catalyzed by Fe. Nanomaterials. 2023;13(4) doi: 10.3390/nano13040753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y.J., Zhou J.E., Zhao K., et al. Synthesis of boron nitride nanotubes from boron oxide by ball milling and annealing process. Mater. Lett. 2009;63(20):1733–1736. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y.J., Wang Y.J., Lv Q.J., et al. Synthesis of uniform plate-like boron nitride nanoparticles from boron oxide by ball milling and annealing process. Mater. Lett. 2013;108:96–102. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang L., Feng Y., Li L., et al. Preparation of super-hydrophobic BN nanotube mesh and theoretical research of wetting state. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li K.R., Zhang Q., Li J., et al. Dual-templating synthesis of superhydrophobic Fe3O4/PSt porous composites for highly efficient oil-water separation. J. Mol. Liq. 2024:396. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu Y.H., Feng A.X., Yu J.H., et al. Preparation of pH-responsive reversible wettable surfaces and application for oil-water separation. Nanotechnology. 2024;35(4) doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/ad00c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen J.F., Hu Y.J., Zhang Z.Y., et al. Study on oil-water separation performance of PDA/ODA composite-modified sponge. Lubric. Sci. 2024 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng X., Jin J., Nakamura Y., et al. Ultrafast permeation of water through protein-based membranes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009;4(6):353–357. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen I.J., Eckstein E.C., Lindner E. Computation of transient flow rates in passive pumping micro-fluidic systems. Lab Chip. 2009;9(1):107–114. doi: 10.1039/b808660e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Research-related data is not stored in publicly available repositories. Data will be made available on request. Please contact the author Zhang Lie, email: zhanglie826175118@163.com.