Abstract

Background.

Organ donation registration rates in the United States are lowest among Asian Americans. This study aimed to investigate the reasons for low organ donation registration rates among Asian Americans and develop educational material to help improve organ donation rates and awareness.

Methods.

We conducted a 2-phase study. In phase 1, a cross-sectional observational survey was distributed in-person on an iPad to members of the Asian community in Queens, New York, to investigate their knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs toward organ donation. Based on the results, an educational video was developed, and the efficacy of the video was assessed with an independent cohort of participants in phase 2 using a pre-/post-video comprehension assessment survey.

Results.

Among 514 Chinese or Korean Americans who participated in the phase 1 survey, 97 participants (19%) reported being registered organ donors. Registered donors were more likely to have previously discussed their organ donation wishes with their family (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 4.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.56-8.85; P < 0.01), knowledge of the different registration methods (aOR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.24-5.31; P < 0.01), or know a registered organ donor (aOR, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.39-4.95; P < 0.01). For the educational video efficacy assessment given pre-/post-video, the majority (90%) of the respondents reported learning something new from the video. After watching the video, there was a significant improvement in the mean knowledge score regarding organ donation (63% versus 92%; P < 0.01) and an increase in intention to have discussion regarding organ donation with family.

Conclusions.

We found varies factors associated with low organ donation registration rates among Asian Americans and demonstrated the potential of our educational video to impart organ donation knowledge to viewers and instigate the intention to have family discussions regarding organ donation. Further research is needed to assess the impact of videos in motivating actual organ donation registration.

INTRODUCTION

The need for organ transplantation continues to far exceed the number of organs available for transplantation. In 2022, while >100 000 individuals were awaiting life-saving organ transplants in the United States, just >42 000 transplants were performed.1 Historically, organ donation rates among racial and ethnic minority groups have been lower than that of the White populations in the United States.2 Among minority groups, organ donation rates in Asian and Pacific Islander populations, in particular, have remained stagnant despite the fact that Asian Americans are the fastest growing racial and ethnic group in the United States, and there has been a corresponding increase in the number of Asian Americans with end-stage organ failure in need of solid organ translantation.2,3 In 2022, Asian Americans constituted 8% of candidates awaiting a transplant but made up only approximately 3% of donors.1 Although shared ethnicity is not a requirement for matching organ donors and recipients, a more diverse donor registry gives ethnic minorities on the transplant waiting list a better chance to find compatible donors and expands the donor pool to benefit all patients.

The reasons for the low organ donor registration rates among Asian Americans remain incompletely understood, although preexisting negative attitudes toward organ donation, limited knowledge and experience with organ donation, the role of the family in decision-making, healthcare system distrust, and level of acculturation have been implicated in previous literature.4 Prior literature has suggested that the need for culturally competent interventions associated with opportunities for registration immediately after intervention could help improve the overall organ donation registration rates, but this remains a poorly understood area with few appropriate educational materials and interventions available.4-6

This study attempts to bridge the gap by assessing the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs toward organ donation as well as other factors affecting organ donation registration among Asian Americans in a large and diverse city and developing culturally competent educational material. We conducted surveys to identify factors associated with low organ donation registration among Asian Americans, developed an educational video informed by our findings, and then assessed the efficacy of this educational video to increase knowledge of organ donation to ultimately increase donor registrations among Asian Americans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and Data Collection

In phase 1 of the study, we administered a cross-sectional observational survey to assess knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs toward organ donation among community members in Queens, New York (NY)—an area with a large Asian population and low organ donation registration rate. In phase 2 of the study, we created an educational video based on the results of phase 1 survey and evaluated its efficacy in improving knowledge of organ donation and intention to register as a donor in the future using pre-/post-video comprehension testing.

For phase 1 of the study, to ensure a broad sampling of the population, bilingual research coordinators (Chinese/English and Korean/English) administered the survey in-person at various locations in the community, including a local health fair, the local community library, Queens College, and 20 primary care physician offices to include participants who were students, patients, and members of the general public during February 2019 and March 2019. Recruitment was complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic for phase 2 of the study. Independent cohort of respondents were recruited via email invitation and then in-person at a community health fair and Queens College after the pandemic restrictions were lifted in between January 2022 and June 2022.

Anyone who self-identified as being of Chinese or Korean descent and aged 18 y old or above was eligible to participate. Participants received and signed the consent form and completed the survey in their preferred language (Mandarin Chinese, Korean, or English) on an iPad. Both surveys were first pilot-tested in English, then translated to Chinese and Korean, and pilot-tested among native speakers on the iPad, mimicking the actual survey administration. Phase 1 survey was approximately 20 min in length, and phase 2 survey, including a 3 min and 37 s video, took approximately 10 min to complete. All participants in both phase 1 and phase 2 of the study received a $10 incentive upon completion of the survey. This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University.

Phase I: Knowledge, Attitude, and Beliefs Investigation Survey

Questions for the phase 1 survey were composed based on our prior systematic literature review and 15 face-to-face key informant interviews.7 Demographics, organ donation registration status, knowledge and attitudes toward organ donation, religious beliefs, altruism and acculturation scores, and personal experience related to organ donation were surveyed (Table S1, SDC, http://links.lww.com/TXD/A690). The level of acculturation was measured using 5 questions extracted from the Asian American Multidimensional Acculturation Scale (AAMAS),8 along with a single question about the extent of their perceived affiliation with Asian and American cultures where answers were recategorized into predominantly American (relatively acculturated), Asian and American identification (bicultural) and predominantly Asian (relatively unacculturated).

We evaluated knowledge regarding organ donation and registration using 12 questions about organ donation based on educational material that is widely disseminated by the local organ procurement organization, which is responsible for organ donation-related activities in the region.9 The knowledge questions were framed as True/False/Don’t know where “Don’t know” was considered an incorrect response. Attitudes and beliefs surrounding organ donation included 16 items informed by the existing literature on evaluating organ donation attitudes.10-13 Likert scales assessing agreement with various statements were also used to measure religious and spiritual beliefs as well as altruism as an influence on the desire to register as organ donors.10,14 Prior organ donation experience was assessed, including participants’ past blood donations, whether they had ever discussed their organ donation wishes with family, and whether they knew any registered organ donors, deceased donors, living donors, individuals waitlisted for transplant, or transplant recipients.

Phase II: Educational Video Efficacy Assessment Survey

Based on the findings of phase 1 (Tables 1–4), we created an educational video, as well as a pre-/post-video comprehension assessment to evaluate the video’s efficacy to increase knowledge of organ donation and to examine intention to register as a donor in the future. A total of 5 people of Chinese or Korean descent participated in the educational video filming, including 1 transplant recipient, 1 living donor, 1 registered organ donor, a transplant nephrologist at our institution, and a Buddhist venerable. The video is available in 3 versions: the original produced in English, English with Mandarin Chinese subtitles, and English with Korean subtitles, which were pilot-tested with native speakers.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of barrier investigation survey respondents (n = 514) by organ donation registration status

| Total, N (%) | Organ donation registration status | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered, N (%) | Not registered, N (%) | |||

| 514 (100) | 97 (19) | 417 (81) | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 290 (56) | 43 (44) | 247 (59) | 0.01 |

| Male | 224 (44) | 54 (56) | 170 (41) | |

| Age (dichotomized at the median) | ||||

| <35 | 251 (49) | 35 (36) | 216 (52) | 0.01 |

| 35 old or older | 258 (50) | 61 (63) | 197 (47) | |

| Unknown | 5 (1) | 1 (1) | 4 (1) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 229 (44) | 49 (51) | 180 (43) | 0.41 |

| Single | 245 (48) | 41 (42) | 204 (49) | |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 40 (8) | 7 (7) | 33 (8) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Chinese | 372 (72) | 54 (56) | 318 (76) | <0.001 |

| Korean | 132 (26) | 40 (41) | 92 (22) | |

| Other (mix with Chinese or Korean descent) | 10 (2) | 3 (3) | 7 (2) | |

| Place of birth | ||||

| US born | 157 (31) | 31 (32.0) | 126 (30.2) | 0.54 |

| Non-US born | 352 (68) | 66 (68.0) | 286 (68.6) | |

| Unknown | 5 (1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.2) | |

| Years in United States | ||||

| <10 | 165 (32) | 21 (22) | 144 (34) | 0.02 |

| ≥10 | 191 (37) | 46 (47) | 145 (35) | |

| Born in United States | 153 (30) | 30 (31) | 123 (30) | |

| Unknown | 5 (1) | 0 (0) | 5 (1) | |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school or no formal education | 38 (7) | 6 (6) | 32 (7) | 0.05 |

| High school graduate | 82 (16) | 17 (18) | 65 (16) | |

| Some college, trade school, or technical | 72 (14) | 18 (19) | 54 (13) | |

| Undergraduate | 282 (55) | 43 (44) | 239 (57) | |

| Graduate degree | 40 (8) | 13 (13) | 27 (7) | |

| Employment | ||||

| Not used | 98 (19) | 12 (12) | 86 (21) | 0.17 |

| Part time | 129 (25) | 22 (23) | 107 (26) | |

| Full time | 145 (28) | 38 (39) | 107 (26) | |

| Homemaker | 29 (6) | 4 (4) | 25 (6) | |

| Retired | 88 (17) | 16 (17) | 72 (17) | |

| Disabled | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Student | 22 (4) | 4 (4) | 18 (4) | |

| Income (dichotomized at the median) | ||||

| <40 K | 230 (45) | 30 (31) | 200 (48) | <0.0001 |

| ≥40 K | 121 (24) | 37 (38) | 84 (20) | |

| Unknown | 163 (32) | 30 (31) | 133 (32) | |

| Acculturation level | ||||

| Self-perceived (1 question) | ||||

| Asian (relatively unacculturated) | 272 (53) | 49 (51) | 223 (54) | 0.22 |

| Both American and Asian (bicultural) | 221 (43) | 41 (42) | 180 (43) | |

| American (relatively acculturated) | 21 (4) | 7 (7) | 14 (3) | |

| Measured (5 AAMAS questions), median (IQR) | ||||

| English language | 2.94 (2–4) | 2.65 (2–3.67) | 0.009 | |

| American culture | 2.95 (2.5–3.5) | 2.70 (2–3) | 0.006 | |

AAMAS, Asian American Multidimensional Acculturation Scale; IQR, interquartile range.

TABLE 4.

Factors associated with organ donation registration among the barrier investigation survey respondents (n = 514)

| Crude OR (95% CI) | P | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Referent | NA | Referent | NA |

| Male | 1.82 (1. 17-2.85) | 0.008 | 2.44 (1.33-4.47) | 0.004 |

| Acculturation | ||||

| How well do you read and write in English? | 1.37 (1.10-1.72) | 0.006 | 1.27 (0.93-1.75) | 0.14 |

| Knowledge | ||||

| You can save up to 8 lives by donating your organs after death | 2.33 (1.42-3.80) | 0.001 | 1.32 (0.70-2.49) | 0.40 |

| No one in the US dies waiting for a transplant because of not receiving an organ in time | 2.10 (1.24-3.54) | 0.005 | 1.34 (0.67-2.67) | 0.41 |

| You can register to donate your organs when you get or renew your driver’s license, and when you apply for a NYC identification card or go through the NY State Department of Health website | 4.45 (2.40-8.23) | <0.0001 | 2.57 (1.24-5.31) | 0.01 |

| You cannot donate your organs if you have high blood pressure or diabetes | 1.86 (1.19-2.92) | 0.006 | 1.42 (0.77-2.62) | 0.27 |

| Attitudes toward donation | ||||

| My family would respect my wish to donate my organs after I pass away | 2.96 (1.56-5.62) | 0.001 | 1.44 (0.58-3.58) | 0.43 |

| Donating a body part would enable part of myself to remain alive after I am gone | 0.55 (0.35-0.86) | 0.008 | 0.62 (0.34-1.12) | 0.11 |

| My family would object if I registered as an organ donor | 2.15 (1.32-3.49) | 0.002 | 1.09 (0.52-2.29) | 0.83 |

| Organ donation leaves the body disfigured and incomplete | 1.94 (1.21-3.13) | 0.006 | 1.42 (0.73-2.78) | 0.30 |

| It is important for the body to be remained complete and buried intact | 2.78 (1.65-4.67) | <0.0001 | 1.83 (0.91-3.70) | 0.09 |

| It is uncomfortable to think or talk about organ donation | 1.77 (1.05-2.99) | 0.033 | 0.75 (0.34-1.68) | 0.49 |

| The thought of my body being cut up or taken apart after I’m gone makes me feel uneasy | 2.49 (1.50-4.13) | <0.0001 | 1.16 (0.54-2.53) | 0.70 |

| Attitudes toward registration | ||||

| Registering will make me proud | 2.77 (1.34-5.71) | 0.006 | 1.52 (0.59-3.92) | 0.39 |

| Registering will make me uncomfortable | 0.24 (0.11-0.51) | <0.0001 | 0.35 (0.13-0.93) | 0.04 |

| Altruism | ||||

| If I could save someone’s life, I would do everything possible | 2.68 (1.04-6.89) | 0.041 | 1.08 (0.34-3.51) | 0.89 |

| Religion/spiritual | ||||

| Religion is an important part of my life | 2.10 (1.32-3.34) | 0.002 | 2.07 (1.10-3.91) | 0.03 |

| Blood donation | ||||

| No | Referent | NA | Referent | NA |

| Yes | 2.05 (1.31-3.20) | 0.002 | 1.49 (0.83-2.68) | 0.19 |

| Discussion with family | ||||

| No | Referent | NA | Referent | NA |

| Yes | 7.19 (4.45-11.61) | <0.0001 | 4.77 (2.57-8.85) | <0.0001 |

| Personal connection | ||||

| Registered organ donor | 6.02 (3.75-9.67) | <0.0001 | 2.62 (1.39-4.95) | 0.003 |

| Deceased organ donor | 2.89 (1.43-5.85) | 0.003 | 1.00 (0.37-2.69) | 0.99 |

| Living organ donor | 2.33 (1.15-4.72) | 0.019 | 1.93 (0.75-4.99) | 0.18 |

| Patient on the waitlist | 2.00 (1.08-3.71) | 0.027 | 0.71 (0.29-1.76) | 0.46 |

CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; NYC, New York City; NY, New York; OR, odds ratio.

In phase 2 survey, we gathered demographic information, organ donation registration status or willingness to register. For those not registered, willingness to register was captured again at post-video. Participants’ knowledge toward organ donation was assessed using 5 questions related to the key concepts communicated in the video before and after watching the video. Additionally, participants were asked if they learned anything new from the video and whether the video influenced their intention to discuss organ donation with their families. The complete survey with the video embedded is included in Table S2 (SDC, http://links.lww.com/TXD/A690).

Data Analysis

Phase I: Knowledge, Attitude, and Beliefs Investigation Survey

We conducted descriptive analyses that included frequency distributions and performed bivariable analyses using chi-square and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables to examine the relationships between study covariates (survey responses of age, marital status, ethnicity, place of birth, years in the United States, education level, employment, income, and acculturation level) and organ donation registration status (registered versus not registered). Age was dichotomized at the mean (<35 versus 35 y old or older), as were years living in the United States (<10 versus ≥10 y) and self-reported household income (<$40 K versus ≥$40 K). For the 5 AAMAS acculturation questions, composite scores and the median (interquartile range) scores and internal consistency were calculated (Cronbach’s alpha, α= 0.90). Factors associated with organ donor registration were examined using logistic regression, adjusted for sex and acculturation.15,16 Results were reported as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). P values of <0.05 determined statistical significance. Data were analyzed using STATA/MP 17.0.

Phase II: Educational Video Efficacy Assessment Survey

We conducted descriptive analyses that included the relationships between organ donation registration status and demographics, including family discussion. For individuals who were not registered for organ donation, we examined the willingness to register and the helpfulness of the video. Bivariable analyses were conducted using Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. Mean knowledge scores were derived using the number of correct responses for all organ donation knowledge questions. Pre- and post-video differences in knowledge scores were assessed using McNemar’s test for individual knowledge questions and mean knowledge scores. Data were analyzed using STATA/MP 17.0.

RESULTS

Phase I: Knowledge, Attitude, and Beliefs Investigation Survey

Demographics

Approximately 882 individuals were approached in-person, of which 544 (62%) agreed to participate in the study. Five hundred fourteen (58%) completed the survey, and their responses were included in the analysis. The most common reason for discontinuing the survey was time constraints. Of the 514 participants, only 97 participants (19%) reported being registered organ donors at the time of the survey. Of all participants, 72% were Chinese American and 26% were Korean American, whereas 2% were of mixed ethnicity (Chinese or Korean and another ethnicity). Slightly more than half the participants were female (56%), single (55%), <35 y (50%), held a bachelor’s degree and above (63%), and were born outside of the United States (68%). Among those participants who were foreign-born, approximately half (54%) reported living in the United States for a median of >10 y (Table 1).

Acculturation

Regardless of country of birth, more than half of the participants (53%) self-identified as being predominantly Asian (relatively unacculturated), 43% of participants identified as both Asian American (bicultural) and only 4% self-identified as predominantly American (relatively acculturated). There was no significant difference between registered and nonregistered participants on the level of acculturation using this one-question assessment. However, when the acculturation level is measured using 5 questions extracted from AAMAS, registered participants reported greater proficiency in speaking, reading, writing, and understanding English (2.94 versus 2.65; P = 0.009) and were more assimilated to American culture (2.95 versus 2.70; P = 0.006) compared with those nonregistered participants (Table 1).

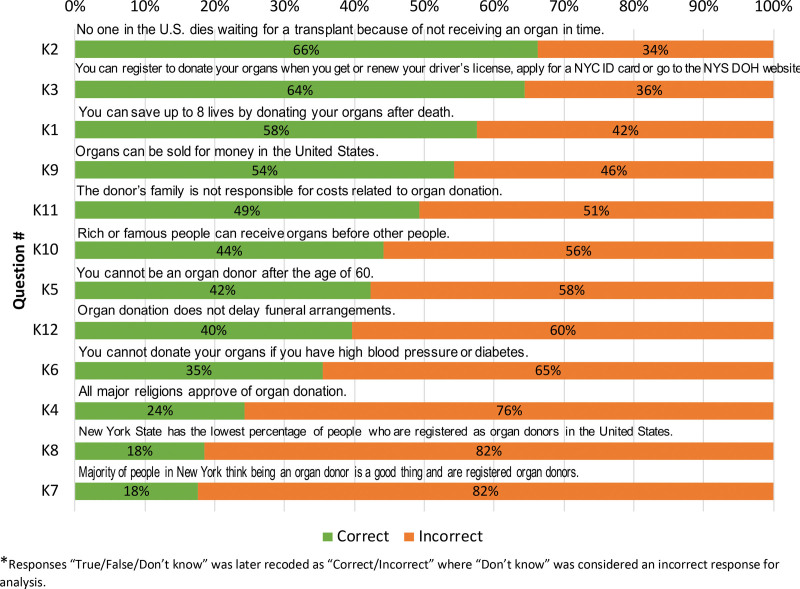

Knowledge

The overall median knowledge score among the participants was low (42%), with only 2% of the participants getting >80% correct. Registered participants scored higher than those who were not registered (50% versus 42%; P < 0.0001), and they were more likely than the nonregistered counterparts to know that one single organ donor can save up to 8 lives (73% versus 54%; P = 0.001), aware of different methods to register as an organ donor (87% versus 59%; P < 0.001), know that many people die while waiting for organ transplant (78% versus 63%; P = 0.005) or that health conditions such as hypertension and diabetes are not contraindications for organ donation (47% versus 33%; P = 0.006; Table 2; Figure 1).

TABLE 2.

Organ donation-related knowledge and attitudes among barrier investigation survey respondents (n = 514) by organ donation registration status

| Total, N (%) | Organ donation registration status | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered, N (%) | Not registered, N (%) | |||

| 514 (100) | 97 (19) | 417 (81) | ||

| Knowledge | ||||

| Overall score, 12 items, % correct, median (IQR) | 42 (25–58) | 50 (42–58) | 42 (25–58) | <0.0001 |

| You can save up to 8 lives by donating your organs after death | 0.001 | |||

| Correct | 296 (58) | 71 (73) | 225 (54) | |

| No one in the US dies waiting for a transplant because of not receiving an organ in time | 0.005 | |||

| Correct | 340 (66) | 76 (78) | 264 (63) | |

| The thought of my body being cut up or taken apart after I’m gone makes me feel uneasy | <0.001 | |||

| Correct | 331 (64) | 84 (87) | 247 (59) | |

| You cannot donate your organs if you have high blood pressure or diabetes | 0.006 | |||

| Correct | 182 (35) | 46 (47) | 136 (33) | |

| Attitudes toward organ donation | ||||

| Positive attitude statements | ||||

| Organ donation is a charitable and noble act | 0.16 | |||

| Agree | 482 (94) | 94 (97) | 388 (93) | |

| Organ donation can help save lives and improve quality of life | 0.82 | |||

| Agree | 474 (92) | 90 (93) | 384 (92) | |

| My family would respect my wish to donate my organs after I pass away | 0.001 | |||

| Agree | 379 (74) | 85 (88) | 294 (71) | |

| Donating a body part would enable part of myself to remain alive after I am gone | 0.008 | |||

| Agree | 355 (65) | 52 (54) | 283 (68) | |

| Negative attitude statements | ||||

| My family would object if I registered as an organ donor | 0.002 | |||

| Agree | 216 (42) | 27 (28) | 189 (45) | |

| Organ donation leaves the body disfigured and incomplete | 0.006 | |||

| Agree | 218 (42) | 29 (30) | 189 (45) | |

| It is important for the body to be remained complete and buried intact | <0.0001 | |||

| Agree | 202 (39) | 21 (22) | 181 (43) | |

| The thought of my body being cut up or taken apart after I’m gone makes me feel uneasy | <0.0001 | |||

| Agree | 205 (40) | 74 (76) | 235 (56) | |

| It is uncomfortable to think or talk about organ donation | 0.03 | |||

| Agree | 158 (31) | 21 (22) | 137 (33) | |

| Attitudes toward registration | ||||

| Registering will make me proud | 0.004 | |||

| Yes | 413 (80) | 88 (91) | 325 (78) | |

| Registering will make me uncomfortable | <0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 121 (23) | 8 (8) | 113 (27) | |

| Altruism | ||||

| If I could save someone’s life, I would do everything possible | 0.03 | |||

| Agree | 456 (89) | 92 (95) | 364 (87) | |

| Religion/spiritual | ||||

| Religion is an important part of my life | 0.002 | |||

| Agree | 270 (53) | 65 (67) | 205 (49) | |

| God/spirituality is an important part of my life | 0.02 | |||

| Agree | 279 (54) | 63 (65) | 216 (52) | |

| It is wrong to donate our organs because we should maintain our entire bodies, which our parents have given us | 0.38 | |||

| Agree | 107 (21) | 17 (18) | 90 (22) | |

| After a person passed away his/her spirits will watch over the descendants; therefore, it would be very disrespectful to damage the body by donating organs | 0.31 | |||

| Agree | 98 (19) | 15 (16) | 83 (20) | |

IQR, interquartile range.

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of phase 1 knowledge, attitude, and beliefs investigation survey participants’ (n = 514) response to organ donation-related knowledge questions. DOH, Department of Health; NYC ID card, New York City identification card.

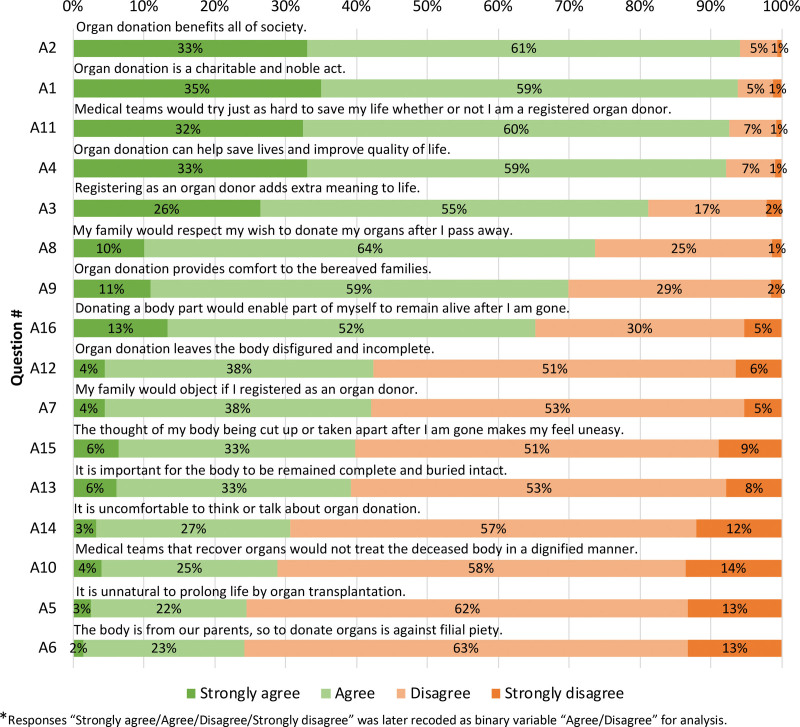

Attitudes

In general, respondents held positive attitudes toward organ donation (Table 2; Figure 2). More than 90% of the participants agreed that organ donation is a charitable and noble act that can help save lives and improve the quality of life. This did not differ based on registration status. However, agreement with negative attitude statements was consistently significantly higher among nonregistered participants compared with registered participants, except for one statement. Surprisingly, unease at the thought of being cut up after death was more often reported among those registered participants compared with those nonregistered participants (76% versus 56%; P < 0.001). Registered participants were also more likely to indicate that registering to be an organ donor makes them proud (91% versus 78%; P = 0.004) and agreed with the altruistic statement “If I could save someone’s life, I would do everything possible” (95% versus 87%; P = 0.03).

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of phase 1 knowledge, attitude, and beliefs investigation survey participants’ (n = 514) response to organ donation-related attitude statements.

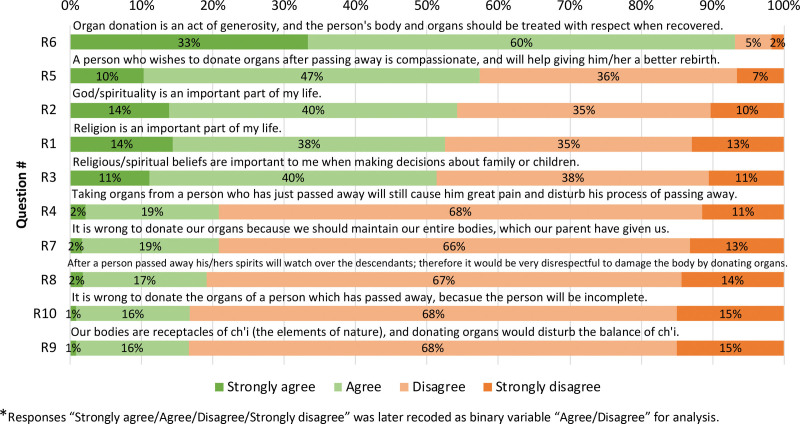

Religious/Spiritual Beliefs

Approximately half of the respondents (54%) stated that religion, God, and spirituality were important parts of their lives (Table 2). Registered participants were more likely than nonregistered participants to consider religion being important part of life (67% versus 49%; P = 0.002). However, there was no significant difference between registered and nonregistered respondents for other religious and spirituality statements (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of phase 1 knowledge, attitude, and beliefs investigation survey participants’ (n = 514) response to religious/spiritual statements.

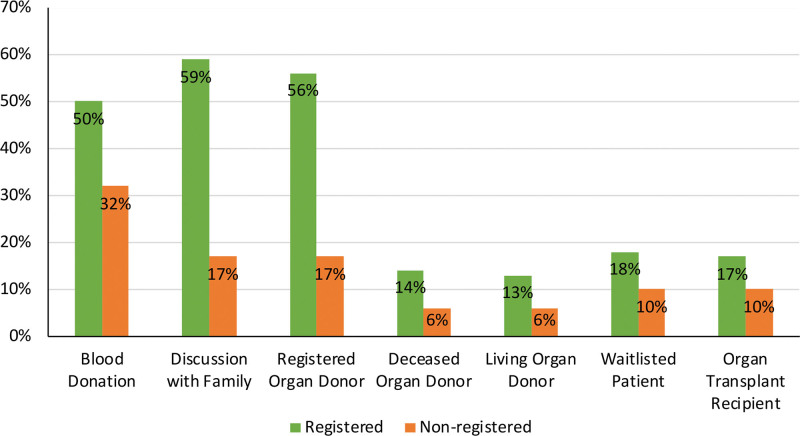

Previous Experiences

Only a minority of participants (25%) reported having had a previous family discussion regarding organ donation registration wishes, but more than half of the registered participants had done so compared with nonregistered participants (56% versus 17%; P < 0.001). Registered respondents also reported higher rates of previous blood donation experience (50% versus 32%; P = 0.002) and knowing another registered organ donor (56% versus 17%; P < 0.001; Table 3; Figure 4).

TABLE 3.

Previous experience with organ donation among barrier investigation survey respondents (n = 514) by organ donation registration status

| Total, N (%) | Organ donation registration status | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered, N (%) | Not registered, N (%) | |||

| 514 (100) | 97 (19) | 417 (81) | ||

| Blood donation | ||||

| Yes | 183 (36) | 48 (50) | 135 (32) | 0.002 |

| Discussion with family | ||||

| Yes | 126 (25) | 57 (59) | 69 (17) | <0.0001 |

| Personal connections | ||||

| Registered organ donor | ||||

| Yes | 126 (25) | 54 (56) | 72 (17) | <0.0001 |

| Deceased organ donor | ||||

| Yes | 37 (7) | 14 (14) | 23 (6) | 0.002 |

| Living organ donor | ||||

| Yes | 39 (8) | 13 (13) | 26 (6) | 0.02 |

| Waitlisted patient | ||||

| Yes | 57 (11) | 17 (18) | 40 (10) | 0.03 |

| Organ transplant recipient | ||||

| Yes | 57 (11) | 16 (17) | 41 (10) | 0.06 |

FIGURE 4.

Distribution of phase 1 knowledge, attitude, and beliefs investigation survey participants’ (n = 514) regarding previous organ donation-related experience by registration status.

Overall

In an adjusted model, after controlling for sex and acculturation level, organ donation registration among the respondents was primarily associated with having knowledge of organ donation registration methods (aOR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.24-5.31; P = 0.01), considering religion to be an important part of life (aOR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.10-39.1; P = 0.03), knowing a registered donor (aOR, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.39-4.95; P = 0.003), and having a family discussion about one’s wishes related to organ donation (aOR, 4.77; 95% CI, 2.57-8.85; P < 0.0001). Participants who reported that registering to become an organ donor would make them feel uncomfortable were less likely to be registered (aOR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.13-0.93; P = 0.04; Table 4).

Phase II: Educational Video Efficacy Assessment Survey

Demographics

Of the 64 people who agreed to participate in the study, 62 (97%) completed the survey, and their responses were included in the analysis. All participants were Asian American of Chinese or Korean descent, with the majority being 35 y old or older (71%) and married (56%) and included very few registered organ donors (10%; Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Sociodemographic of respondents (n = 62) to pre-/post-comprehension assessment to evaluate video efficacy by organ donation registration status

| Total, N (%) | Organ donation registration status | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered, N (%) | Not registered, N (%) | |||

| 62 (100) | 6 (10) | 56 (90) | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 40 (65) | 3 (50) | 37 (66) | 0.66 |

| Male | 22 (35) | 3 (50) | 19 (34) | |

| Age | ||||

| <35 y old | 18 (29) | 2 (33) | 16 (29) | 1.00 |

| >35 y old | 44 (71) | 4 (67) | 40 (71) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 35 (56) | 2 (33) | 33 (59) | 0.12 |

| Single | 18 (29) | 2 (33) | 16 (29) | |

| Other (separated/divorced/widowed) | 9 (15) | 2 (33) | 7 (12) | |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 11 (18) | 1 (17) | 10 (18) | 0.03 |

| High school graduate | 18 (29) | 2 (33) | 16 (29) | |

| Some college, trade school, or technical | 11 (18) | 2 (33) | 9 (16) | |

| College graduate | 21 (34) | 0 (0) | 21 (38) | |

| Postgraduate professional degree | 1 (2) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | |

| Discussion with family | ||||

| Yes | 17 (27) | 3 (50) | 14 (25) | 0.33 |

| No | 45 (73) | 3 (50) | 42 (75) | |

Video Efficacy Assessment

Among those nonregistered participants (90%), the majority expressed willingness to register (73%) and that the video will help them make the decision about organ donation in the future (80%). Few participants (27%) reported having had a prior conversation with family about organ donation, but a majority (67%) of those who had not done so expressed intention to do so after watching the video (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Participants response to pre-/post-video comprehension assessment

| Questions | Pre-video, N (%) | Post-video, N (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| If not registered, willingness to register? (n = 56) | |||

| Yes | 41 (73) | 40 (71) | 0.78 |

| No | 15 (27) | 16 (19) | |

| If not registered, helpfulness of the video? (n = 56) | |||

| Yes | NA | 45 (80) | |

| No | NA | 11 (20) | |

| Discussion with family (n-=62) | |||

| Yes | 17 (27) | NA | |

| No | 45 (73) | NA | |

| If no discussion with family, post-video family discussion intention? (n = 45) | |||

| Yes | NA | 30 (67) | |

| No | NA | 15 (33) | |

| Learned anything from the video? (n = 62) | |||

| Yes | NA | 56 (90) | |

| No | NA | 6 (10) | |

| If yes, content learned (n = 56) | |||

| Organ donation saves life | NA | 26 (46) | |

| Desperate need of organ | NA | 11 (20) | |

| Family discussion importance | NA | 8 (14) | |

| Other (all age can donate, registration method, etc) | NA | 11 (20) | |

| Knowledge | |||

| Mean score, % | 63 | 92 | <0.01 |

| K1. You can save up to 8 lives by donating your organs after death | <0.0001 | ||

| Correct | 37 (60) | 59 (95) | |

| K2. No one is ever too old to become an organ donor | <0.0001 | ||

| Correct | 39 (63) | 58 (94) | |

| K3. Registering as an organ donor does not change the medical care you will receive | 0.0002 | ||

| Correct | 44 (71) | 58 (94) | |

| K4. Most religion view organ donation as a noble act | <0.0001 | ||

| Correct | 38 (61) | 57 (92) | |

| K5. You can register to donate your organs through the DMV, on your iPhone health App, and online at DonateLife.net | <0.0001 | ||

| Correct | 38 (61) | 54 (87) | |

DMV, Department of Motor Vehicles; NA, not applicable.

Most participants (90%) said they had learned something new from the video. Most stated learning about the life-saving nature of organ transplantation (46%), the need for organ for transplantation (20%), and the importance of open conversation with family about organ donation registration (14%). There was a significant improvement in the mean knowledge score regarding organ donation after watching the video (63% versus 92%; P < 0.01; Table 6).

DISCUSSION

The findings of our study revealed a myriad of potential barriers and facilitators to organ donation among Asian Americans. We used what we learned from our phase 1 survey to create a culturally tailored short educational video. Our pre-/post-video knowledge assessment demonstrated a significant increase in comprehension of the key organ donation concepts conveyed in the video, thus showing the potential of this intervention to increase organ donation awareness, potentially improve registration rates and stimulate additional discussions with families about organ donation registration in Asian American communities.

We found that only a minority of the respondents were registered organ donors at the time of the surveys, which was consistent with the low organ donation registration rates in Queens, NY. Similar to other studies, registered participants overall had significantly more organ donation knowledge compared with the nonregistered counterparts, and general knowledge about organ donation and transplantation was low—underscoring the educational opportunity in this community.11,17-19 Not surprisingly, acculturation in terms of English speaking, writing, and reading proficiency was significantly higher among registered respondents highlighting the need for educational materials in one’s native languages to successfully reach communities with large and/or recent immigrant populations with language barriers.

Our study identified previous family discussions and personal experiences related to organ donation as being strongly associated with organ donor registration.11,18,20,21 The importance of family discussion likely stems from the Confucian ideology prioritizing family above all, highlighting the role of culture-specific values and beliefs involved in the decision of registering as an organ donor among Asian Americans.11,21 The majority of our respondents never discussed organ donation with their family previously, which could be because of the cultural avoidance of talks about death-related topics, fearing that such discussion can bring bad luck.22

When asked specifically about the Confucian concept of filial piety—that our body, skin, and hair are all received from our parents; we dare not injure them—only a minority of respondents (24%) felt that organ donation violated this concept. Our result coincided with a more recent study conducted in mainland China, where 65.3% of the respondents did not agree with filial piety, and only 28.1% of the respondents thought that body intactness was important.12 In another study, only 15.3% of the participants felt that organ donation went against Chinese traditions.23 These more recent data highlighted the trend of decreasing the influence of filial piety on making decisions about organ donation with time, especially among the younger generations. These results revealed the complexity of cultural values and beliefs’ effect on organ donation and highlighted the importance of a keen understanding of the culture when integrating it into the design of educational materials.

The overall attitude toward organ donation and registration was positive in our study population despite low rates of organ donation registration. Nonregistered participants agreed with negative attitude statements more often than registered participants, except for one negative statement “the thought of my body being cut up or taken apart after I’m gone makes me feel uneasy.” Understanding how registered individuals have overcome the negative attitude to still register as organ donors may help identify additional strategies for improve organ donation registration rates further.

Although the results from phase 2 of the study suggested our educational video is engaging and understandable to viewers, and it is effective in imparting new organ knowledge and instigating intention for a family discussion about organ donation, the retention of the learned knowledge and its effect on intention to register as an organ donor is uncertain. The highly stated willingness to register by the respondents both before and after watching the video limited our ability to truly assess if providing additional education on organ donation and transplantation actually increase willingness to register by individuals who are considering registration. Further research is needed to assess the impact of the educational video in motivating actual organ donation registration.

Our study was limited by a small sample size and low response rate, especially for the video assessment survey in the second phase of the study. We were unable to administer the survey entirely in-person like we did in phase 1 of the study due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in a drastically decreased response rate and sample size. Most of the respondents in the second phase of the study were recruited at a local community health fair that was attended by seniors, which inadvertently introduced selection bias.

Although our study was limited by a relatively small sample size and was observational in nature, it studied the Asian American population on a more granular level. We focused on Chinese and Korean Americans, evaluating the factors associated with organ donor registration decisions, and developed and tested the efficacy of culturally specific organ donation educational material for Chinese and Korean Americans. Most of the previous research studied Asian Americans as a large group when Asian Americans are a diverse population that is comprised of many ethnic groups, including Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, etc.24,25 There are more differences than similarities between these Asian ethnic groups, so it is essential that they are studied as distinct groups to create effective culturally specific organ donation educational materials. Our study was also limited to a specific geographic location (Queens, NY) and Chinese and Korean Americans, but this lack of geographic and demographic diversity was by design. The high concentration of Asians in Queens, NY, provided a unique environment for us to conduct our investigation about the reason for low organ donation registration rates among Chinese and Korean Americans.

Because of geographical and ethnicity limitations, our results’ generalizability and educational video’s applicability to other Asian American groups require further research. The educational video developed focused heavily on improving general organ donation knowledge and promoting the importance of family discussion about organ donation—its efficacy can be assessed in new study populations such as high school students or population with different ethnical or cultural backgrounds in future studies.

Regarding the survey design, although we inquired about organ donation discussions with the family, we did not specifically ask about the temporality of the discussion. That is, we did not ascertain if the conversation occurred before or after registration for those who registered and thus cannot comment on the impact of the family to persuade or dissuade an individual from registering if the discussion occurred before registration. Additionally, although both surveys were pilot-tested, they were not systematically validated by testing the reliability and validity. We successfully demonstrated that our video has the potential to significantly increase knowledge of organ donation needs and registration methods. Whether knowledge alone is sufficient to overcome negative attitudes and deep-seated cultural values to motivate individuals to act and register as a donor remains to be investigated in the future studies. Our efforts represent the first steps in moving toward greater awareness of this important issue regarding organ donation and open the door for future dialogue in this community.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

S.M. and G.C.H. were supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK114893).

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

M.T. L., G.C.H., K.L.K., M.Y., S.A.H., and S.M. participated in research design, performance of the research and analysis, and writing of the article.

Supplemental digital content (SDC) is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.transplantationdirect.com).

Contributor Information

Miah T. Li, Email: mtl2156@cumc.columbia.edu.

Grace C. Hillyer, Email: gah28@cumc.columbia.edu.

Kristen L. King, Email: klking92@gmail.com.

Miko Yu, Email: my2750@cumc.columbia.edu.

S. Ali Husain, Email: sah2134@cumc.columbia.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Organ procurement and transplantation network, national data. Available at https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/. Accessed February 8, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kernodle AB, Zhang W, Motter JD, et al. Examination of racial and ethnic differences in deceased organ donation ratio over time in the US. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:e207083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pew Research Center. Asian Americans are the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in the U.S.. Available at https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/09/asian-americans-are-the-fastest-growing-racial-or-ethnic-group-in-the-u-s/. Accessed February 8, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li MT, Hillyer GC, Husain SA, et al. Cultural barriers to organ donation among Chinese and Korean individuals in the United States: a systematic review. Transpl Int. 2019;32:1001–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deedat S, Kenten C, Morgan M. What are effective approaches to increasing rates of organ donor registration among ethnic minority populations: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li AH, Garg AX, Grimshaw JM, et al. Promoting deceased organ and tissue donation registration in family physician waiting rooms (RegisterNow-1): a pragmatic stepped-wedge, cluster randomized controlled registry trial. BMC Med. 2022;20:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li MT, Hillyer GC, Kim DW, et al. Factors that influence organ donor registration among Asian American physicians in Queens, New York. J Immigr Minor Health. 2021;24:394–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung RH, Kim BS, Abreu JM. Asian American multidimensional acculturation scale: development, factor analysis, reliability, and validity. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2004;10:66–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LiveOnNY. Commonly asked questions. Available at https://www.liveonny.org/info/. Accessed February 2, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rumsey S, Hurford DP, Cole AK. Influence of knowledge and religiousness on attitudes toward organ donation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:2845–2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung CK, Ng CW, Li JY, et al. Attitudes, knowledge, and actions with regard to organ donation among Hong Kong medical students. Hong Kong Med J. 2008;14:278–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo AJ, Xie WZ, Luo JJ, et al. Public perception of cadaver organ donation in Hunan province, China. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:2571–2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parisi N, Katz I. Attitudes toward posthumous organ donation and commitment to donate. Health Psychol. 1986;5:565–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam WA, McCullough LB. Influence of religious and spiritual values on the willingness of Chinese-Americans to donate organs for transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2000;14:449–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thornton JD, Wong KA, Cardenas V, et al. Ethnic and gender differences in willingness among high school students to donate organs. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trompeta JA, Cooper BA, Ascher NL, et al. Asian American adolescents’ willingness to donate organs and engage in family discussion about organ donation and transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2012;22:33–40, 70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bresnahan M, Lee SY, Smith SW, et al. A theory of planned behavior study of college students’ intention to register as organ donors in Japan, Korea, and the United States. Health Commun. 2007;21:201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu D, Huang H. Knowledge, attitudes, and willingness toward organ donation among health professionals in China. Transplantation. 2015;99:1379–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sehgal NK, Scallan C, Sullivan C, et al. The relationship between verified organ donor designation and patient demographic and medical characteristics. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:1294–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung J, Choi D, Park Y. Knowledge and opinions of deceased organ donation among middle and high school students in Korea. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:2805–2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu AM. Discussion of posthumous organ donation in Chinese families. Psychol Health Med. 2008;13:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braun KL, Nichols R. Death and dying in four Asian American cultures: a descriptive study. Death Stud. 1997;21:327–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H, Zheng J, Liu W, et al. Investigation and strategic analysis of public willingness and attitudes toward organ donation in East China. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:2419–2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siminoff LA, Chansiri K, Alolod G, et al. Culturally tailored and community-based social media intervention to promote organ donation awareness among Asian Americans: “heart of gold”. J Health Commun. 2022;27:450–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alolod GP, Gardiner HM, Blunt R, et al. Organ donation willingness among Asian Americans: results from a national study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;10:1478–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.