Abstract

Purpose

Concerns exist regarding the potential for transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) to yield poorer functional outcomes compared to laparoscopic TME (LaTME). The aim of this study is to assess the functional outcomes following taTME and LaTME, focusing on bowel, anorectal, and urogenital disorders and their impact on the patient’s QoL.

Methods

A systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and A Measurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) guidelines. A comprehensive search was conducted in Medline, Embase, Scopus, and Cochrane Library databases. The variables considered are: Low Anterior Resection Syndrome (LARS), International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and Jorge-Wexner scales; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C29 and QLQ-C30 scales.

Results

Eleven studies involving 1020 patients (497-taTME group/ 523-LaTME group) were included. There was no significant difference between the treatments in terms of anorectal function: LARS (MD: 2.81, 95% CI: − 2.45–8.08, p = 0.3; I2 = 97%); Jorge-Wexner scale (MD: -1.3, 95% CI: -3.22–0.62, p = 0.19). EORTC QLQ C30/29 scores were similar between the groups. No significant differences were reported in terms of urogenital function: IPSS (MD: 0.0, 95% CI: − 1.49–1.49, p = 0.99; I2 = 72%).

Conclusions

This review supports previous findings indicating that functional outcomes and QoL are similar for rectal cancer patients who underwent taTME or LaTME. Further research is needed to confirm these findings and understand the long-term impact of the functional sequelae of these surgical approaches.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00384-024-04703-x.

Keywords: Transanal TME, Laparoscopic TME, Functional outcomes, Quality of Life, Rectal cancer, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Total mesorectal excision (TME) is the gold standard treatment for middle and lower rectal tumors. The technique involves the complete, en bloc removal of the mesorectal fat with associated lymph nodes, which is pivotal for achieving low local recurrence rates [1].

The evolution of TME surgery from open to laparoscopic, robotic, and transanal approaches, accompanied by significant technological advancements, has improved surgical outcomes and minimized invasiveness.

Transanal TME (taTME) is the latest advancement, pioneered to tackle insidious pelvic dissections required for tumors located in the lower third of the rectum [2]. First described by Sylla et al. in 2010, it has since seen a progressive and wide adoption in clinical practice [3]. taTME offers the advantage of improved visibility and access to the distal rectum, with the aim of achieving a more precise dissection that may lead to a lower rate of positive circumferential resection margins and better preservation of autonomic nerves. This approach appears particularly advantageous in case of patients with anatomic constraints that make LaTME challenging, including a narrow pelvis, obesity, and low-lying tumors [2, 4–8]. Several studies indicate that taTME may offer advantages over LaTME, including a lower conversion rate to open surgery, wider circumferential resection margins (CRM), and lower rates of positive CRM involvement. [9–12] However, in terms of oncological outcomes, when performed in high-volume centers, both taTME and LaTME achieve equivalent resection quality and show similar local recurrence rates [9–11, 13, 14]. Perioperative outcomes such as estimated blood loss, hospital stay, intraoperative complications, and postoperative complications do not show significant differences between the two approaches [9–12, 15–17]. However, in some studies, taTME has been associated with shorter operative times, lower overall morbidity, and reduced rates of anastomotic leak compared to LaTME [10, 12, 17–19]. Conversely, there have been increased concerns about reports of higher incidence of postoperative fecal incontinence following taTME. [13]

While the long-term outcomes and comparisons with standard laparoscopic or robotic rectal resections are still being evaluated [20, 21], data about the functional sequelae from both laparoscopic and transanal approaches and their impact on patient’s quality of life (QoL) are still limited [22].

While some variability exists in the literature [23], evidence suggests that taTME might initially be associated with more significant functional impairments, though these differences may diminish over time [24, 25].

This paper aims to assess the comparative functional outcomes following taTME and LaTME, focusing on bowel, anorectal, and urogenital disorders and their impact on the patient’s QoL.

Material and methods

Data sources and searches

The peer-reviewed literature published from January 1982 to May 2024 was searched using Medline (PubMed), Embase, Scopus, and Cochrane Library databases with MeSH terms [rectal neoplasm OR cancer] AND [transanal TME OR laparoscopic TME OR “Total Mesorectal Excision”] AND [“function” OR “functional outcomes” OR “Quality of Life”], and with limits “Title/Abstract, Human Subjects, English”.

This meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies (PRISMA-DTA) Statement, Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines and A Measurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) guidelines [26–28]. The planned protocol of this meta-analysis was registered in PROSPERO (PROSPERO 2023: CRD42024540266). In addition, the reference lists of retrieved articles were screened to identify further studies. The final aim of the search was to identify studies comparing taTME vs LaTME in terms of functional outcomes and Quality of Life in adult patients to provide a synthesis of the scientific evidence by the meta-analysis process.

Study selection

Two investigators (SL and FB) independently screened titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible studies using Rayyan systematic review software [29] and confirmed eligibility by reading the full-text publication of selected records. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus or arbitration by a third reviewer (PS). Studies were considered eligible if they included adult patients diagnosed with rectal cancer, compared transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME) to laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (LaTME), and reported on functional outcomes and quality of life (QoL).

No geographic or language restrictions were applied. Papers were excluded if they reported duplicative results from the same authors’ group, if they lacked sufficient data, or in case of non-comparative studies, reviews, meta-analyses, letters, case reports, or conference abstracts.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors examined the main features of each retrieved article, reporting the following data: (a) study characteristics: the first author, country, year of publication, number of patients, study type; (b) patient baseline: tumor site, gender, age, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, rectal cancer distance from the anal verge, tumor staging, neoadjuvant treatment, protective ileostomy, time of ileostomy reversal, time of follow up from index surgery, and previous functional impairments; (c) study outcomes: (1) functional results: Low Anterior Resection Syndrome (LARS) scale [30, 31], International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) [32] and Jorge-Wexner scale [33]; (2) the QoL: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C29 [34] and QLQ-C30 [35, 36] scales.

Data synthesis and analysis

Categorical data were collected as absolute numbers. If reported as median and range, these were converted to mean and standard deviation (SD) using the method described by Wan et al. [37] A random-effects model was used for the meta-analysis of all outcomes. All estimates were presented with a 95% confidence interval (CI). A continuity correction of 0.5 was applied in studies with zero cell frequencies to calculate confidence limits and standard errors.

Heterogeneity among effect size (ES) results was assessed using the Q and I2 statistics. I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% represented low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [38]. All analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan, Version 5.4.1). When high heterogeneity was detected, a sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the robustness of the overall findings by systematically excluding individual studies or subgroups to determine their impact on the pooled effect estimates.

Risk of bias assessment

The quality of non-randomized controlled trials (NRCTs) was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [39], with scores ranging from 7 to 8 stars, indicating good quality. Two researchers independently assessed the study using the Review Manager tool, focusing on five key domains: bias arising from the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported result. Discrepancies were resolved through consultation with a third-party expert. The detailed risk of bias assessment is provided in the supplementary materials. In accordance with Cochrane guidelines, publication bias was not assessed as fewer than ten studies were included in each data comparison. [40]

Results

Study characteristics

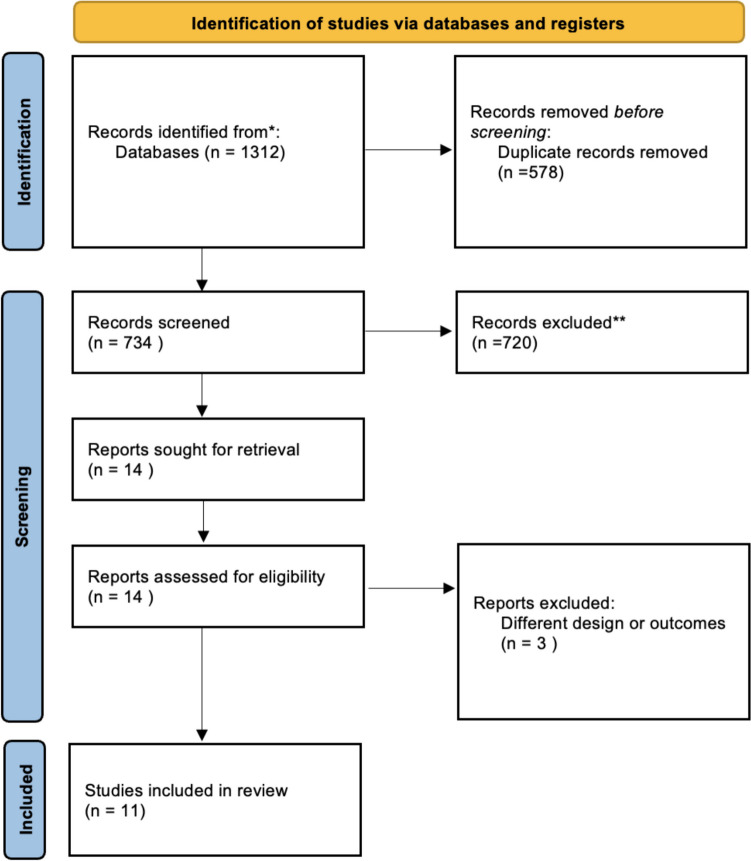

The initial literature search retrieved 1312 publications. Of these, 11 studies [19, 21, 41–49] were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1), involving 1020 patients (497 in the taTME group and 523 in the LaTME group). Among the included studies, eight were retrospective studies [41–44, 46–49], three prospective cohort studies [19, 45, 50].

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) flowchart of the literature search

Patient characteristics

The baseline characteristics of patients from the included studies are presented in Table 1 and Table 2, allowing for comparison between the taTME and LaTME groups. Demographic parameters and the use of neoadjuvant treatment were assessed.

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Author and year | Study period | No. of centres, country | Study design | Functional outcome assessment | No of patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaTME | LaTME | |||||

| Seow-En et al. [44], 2024 | 2021–2022 | 1, Singapore | Retrospective, PS matched | LARS, Jorge-Wexner scale | 12 | 36 |

| Yang et al. [49], 2023 | 2019–2021 | 1, China | Retrospective | LARS, Jorge-Wexner scale | 17 | 34 |

| Li et al. [50], 2021 | 2014–2018 | 1, China | Prospective | QLQ-C29, LARS, Jorge-Wexner scale | 30 | 30 |

| Kyong Ha et al. [45], 2021 | 2014–2017 | 1, Korea | Prospective, PS matched | LARS, IPSS, QLQ-C30 | 202 | 202 |

| Foo et al. [46], 2020 | 2016–2018 | 1, China | Retrospective | LARS, Jorge-Wexner scale | 35 | 35 |

| Bjoern et al. [41], 2019 | 2010–2017 | 1, Denmark | Retrospective, prosp. DB | LARS, IPSS, EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-C29 | 49 | 36 |

| Rubinkiewicz et al. [48], 2019 | 2013–2017 | 1, Poland | Retrospective, prosp. DB | LARS, Jorge-Wexner scale | 23 | 23 |

| Dou et al. [43], 2019 | 2016–2017 | 1, China | Retrospective | LARS | 54 | 53 |

| Mora et al. [47], 2018 | 2011–2014 | 1, Spain | Retrospective, prosp. DB | LARS, EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ C-29 | 16 | 15 |

| Veltcamp Helbach et al. [42], 2018 | 2010–2012 | 1, The Netherlands | Retrospective | LARS, EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ C-29, IPSS | 27 | 27 |

| de' Angelis et al. [19], 2015 | 2011–2014 | 1, France | case-matched study | Jorge-Wexner scale | 32 | 32 |

Table 2.

Patients characteristics

| Author and year | Age, mean (SD) | Sex ratio, M/F, (%) | Neoadjuvant CRTx, n (%) | NOS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaTME | LaTME | TaTME | LaTME | TaTME | LaTME | p value | 7 | |

| Seow-En et al. [44], 2024 | 69.3 ( 6.2) | 67.9 ± 11.2 | 8 (66.7)/4 (33.3) | 23 (63.9)/ 13 (36.1) | 2 (16.7) | 10 (27.8) | 0.829 | 7 |

| Yang et al. [49], 2023 | 62.88 (10.37) | 63.74 ± 11.07 | 11 (64.71)/ 6 (35.29) | 19 (55.88)/ 15 (44.12) | 6 (35.29) | 16 (47.06) | 0.617 | 8 |

| Li et al. [50], 2021 | NR | NR | 14 (47)/ 16 (53) | 13 (43)/ 17 (57) | 17 (57) | 15 (50) | 0.446 | 8 |

| Kyong Ha et al. [45], 2021 | 62.43 ( 9.98) | 61.46 ± 11.24 | 129 (63.9)/ 73 (36.1) | 131 (64.9)/ 71 (35.1) | 129 (63.9) | 118 (58.4) | 0.262 | 7 |

| Foo et al. [46], 2020 | 67 (25.93) | 68 (27.41) | 24 (68.6)/11 (31.4) | 23 (65.7)/12 (34.3) | 14 (40) | 15 (42.9) | 1.000 | 8 |

| Bjoern et al. [41], 2019 | 64.88 (9.645) | 62.42 (10.146) | 37 (75.5)/12 (24.5) | 16 (44.4)/20 (55.6) | 8 (16.3) | 8 (22.2) | 0.492 | 8 |

| Rubinkiewicz et al. [48], 2019 | 60 (11.85) | 64 (6.67) | 13 (56.5)/10 (43.5) | 13 (56.5)/10 (43.5) | 18 (78.3) | 19 (82.6) | 0.71 | 8 |

| Dou et al. [43], 2019 | 57.5 (37.78) | 62 (29.63) | 35 (64.8)/19 (35.2) | 35 (66)/18 (34) | 12 (22.2) | NR | NR | 7 |

| Mora et al. [47], 2018 | 64 (NR) | 59.9 (NR) | 12 (75)/4 (25) | 10 (66.7)/5 (33.3) | 7 (43.75) | NR | NR | 6 |

| Veltcamp Helbach et al. [42], 2018 | 68 (5.33) | 62.7 (4.52) | 18 (66.7)/9 (33.3) | 20 (74)/7 (26) | 18 (66.67) | 22 (81.5) | 0.395 | 7 |

| de' Angelis et al. [19], 2015 | 64.9 (10.0) | 67.2 (9.6) | 21 (65.6)/11 (34.4) | 21 (65.6)/11 (34.4) | 27 (84.4) | 23 (71.8) | 0.365 | 8 |

| Author and year | Distance from a.v. (cm) | Tumor staging | Protective ileostomy, n (%) | Time of ileostomy reversal (mo) | Time of follow up from index surgery (mo) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| taTME | LaTME | p value | taTME | LaTME | p value | taTME | LaTME | p value | taTME | LaTME | p value | taTME | LaTME | p value | |

| Seow-En et al. [44], 2024 | NR | NR | NR |

pCR = 1 T1 = 2 T2 = 0 T3 = 9 T4 = 0 N0 = 5 N1 = 7 N2 = 0 |

pCR = 2 T1 = 3 T2 = 9 T3 = 20 T4 = 2 N0 = 25 N1 = 9 N2 = 2 |

0.035* | NR | NR | NR | 5 ± 3 | 7 ± 6.5 | 28 ± 14 | < 0.05* | ||

| Yang et al. [49], 2023 | 4.03 ± 0.86 | 4.32 ± 0.75 | 0.251 |

I = 4 II = 7 III = 6 |

I = 4 II = 14 III = 15 |

0.7 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 18.56 ± 4.35 | 17.86 ± 6.36 | 0.645 | |

| Li et al. [50], 2021 |

< 5 cm = 11 ≥ 5 cm = 19 |

< 5 cm = 13 ≥ 5 cm = 17 |

0.778 |

T0/1 = 12 T2/3/4 = 18 |

T0/1 = 13 T2/3/4 = 17 |

0.793 | 28 (93.3) | 29 (96.7) | 0.776 | 7.8 ± 8 | 8.1 ± 10 | 0.83 | 3 and 12 | 3 and 12 | NR |

| Kyong Ha et al. [45], 2021 |

≤ 5 cm = 98 ≤ 10 cm = 94 > 10 cm = 10 |

≤ 5 cm = 83 ≤ 10 cm = 111 > 10 cm = 8 |

0.238 |

T1 = 24 T2 = 24 T3 = 136 T4 = 18 |

T1 = 24 T2 = 27 T3 = 135 T4 = 16 |

0.96 | 151 (74.8) | 168 (83.2) | 0.038 | 3 months postoperatively or 1 month after adjuvant therapy | 12 | 12 | NR | ||

|

N- = 61 N + = 141 |

N- = 66 N + = 136 |

0.592 | |||||||||||||

| Foo et al. [46], 2020 | 7 ± 8 | 7 ± 8 | 0.953 |

T1/2 = 26 T3/4 = 9 |

T1/2 = 17 T3/4 = 17 |

0.05 | 27 (77.1) | 8 (87.5) | 0.347 | 8 ± 9 | 8.5 ± 11 | 0.146 | 3,6 and 12 | 3,6 and 12 | NR |

| Bjoern et al. [41], 2019 | 8.35 ± 1.727 | 8.14 ± 1.885 | 0.599 |

T2 = 25 T3 = 23 T4 = 1 |

T2 = 17 T3 = 19 T4 = 0 |

0.625 | 49 (100) | 36 (100) | NR | 3 months postoperatively or until the completion of adjuvant CT | 22.69 ± 10.308 | 75.08 ± 17.609 | < 0.001* | ||

|

N0 = 35 N1 = 6 N2 = 8 |

N0 = 10 N1 = 10 N2 = 16 |

< 0.001* | |||||||||||||

| Rubinkiewicz et al. [48], 2019 | 3 ± 2 | 4 ± 2 | *0.01 |

T1 = 2 T2 = 3 T3 = 15 T4 = 3 |

T1 = 3 T2 = 6 T3 = 12 T4 = 2 |

0.24 | 23 (100) | 23 (100) | NR | NR | NR | Follow up at 6 months after ileostomy reversal | NR | ||

|

N—= 13 N + = 23 |

N—= 14 N + = 23 |

0.76 | |||||||||||||

| Dou et al. [43], 2019 |

< 5 cm = 22 ≥ 5 cm = 32 |

< 5 cm = 25 ≥ 5 cm = 28 |

> 0.05 | NR | NR | NR | 20 (37) | 34 (64.2) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Mora et al. [47], 2018 | 7.44 | 7.93 | 0.723 |

0 = 0 I = 5 II = 7 III = 2 |

0 = 3 I = 6 II = 3 III = 3 |

0.143 | 16 (100) | 15 (100) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Veltcamp Helbach et al. [42], 2018 |

Low = 9 Mid = 14 High = 4 |

Low = 7 Mid = 18 High = 2 |

0.569 |

T0/1 = 4 T2 = 12 T3 = 11 |

T0/1 = 6 T2 = 9 T3 = 12 |

0.647 | 22 (81.5) | 22 (81.5) | NR | 6 weeks after surgery | NR | 20 ± 37.8 | 59.5 ± 42.3 | 0.000* | |

| de' Angelis et al. [19], 2015 | 4 ± 2.5 | 3.7 ± 2.5 | 0.631 |

T2 = 13 T3 = 17 T4 = 2 |

T2 = 16 T3 = 13 T4 = 3 |

0.593 | 32 (100) | 32 (100) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 32.06 ± 12.1 | 62.91 ± 12.3 | < 0.05* |

|

N0 = 21 N1 = 10 N2 = 1 |

N0 = 14 N1 = 15 N2 = 3 |

0.183 | |||||||||||||

There were no substantial differences in demographics between groups across studies. The proportion of males was slightly higher in the taTME group (65%) compared to the LaTME group (62%). Mean age was similar between groups, with a negligible difference of -0.541 years (95% CI: -2.951 to 1.869; p = 0.66). Based on five studies, the mean BMI difference between groups was 1.18 (95% CI: -59.03 to 61.39; p = 0.5). Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy was administered to a slightly higher percentage of patients in the taTME group (61.4%) compared to the LaTME group (54.5%), but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.08). The distance from the anal verge has not shown statistical significance in any studies, with the exception of the study published by Rubinkiewicz et al. (taTME = 3 ± 2; LaTME = 4 ± 2; p = 0.01) [48].

Three studies examined previous functional impairments [45, 46, 48].

Kyong Ha et al. [45] revealed that major LARS was found in 19.1% of patients in the taTME group vs 13.6% in the LaTME group. No statistical significant difference was reported. Additionally, no patient experienced fecal incontinence before treatment.

Foo et al. [46] showed that the median preoperative baseline Wexner score was 0 for both groups.

Rubinkiewicz et al. [48] revealed that the median preoperative LARS score were 0 (IQR: 0–5) and 5 (0–21) in LaTME and TaTME groups, respectively (p = 0.10). Furthermore, there was no significant difference for the median preoperative Wexner score between groups (p = 0.20).

Finally, only four studies [42, 45, 49, 50] have reported their experience with taTME.

A detailed descriptive analysis of functional outcomes and quality of life is provided in Tables 3 and 4 and Tables 1s-2s in the Supplementary materials.

Table 3.

EORTC QLQ-C29

| EORTC QLQ-C29 | Li et al. [50] (2021) | Bjoern et al. [41] (2019) | Mora et al. [47] (2018) | Veltcamp Helbach et al. [42] (2018) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaTME | LaTME | p | TaTME | LaTME | p | TaTME | LaTME | p | TaTME | LaTME | p | ||

| Functional scales | Body image | 81 | 83.5 | 0.730 | 89.34 | 88.58 | 0.647 | 90.97 | 85.19 | 0.432 | 88.40 | 90.90 | 0.325 |

| Anxiety | 70 | 66 | 0.297 | 79.59 | 81.48 | 0.954 | 72.92 | 64.44 | 0.489 | 74.40 | 75.30 | 0.715 | |

| Weight | 72 | 71 | 0.836 | 84.35 | 86.11 | 0.605 | 66.67 | 77.78 | 0.361 | 87.20 | 84.10 | 0.493 | |

| Sexual interest (men) | 34 | 36 | 0.426 | 50.45 (37) | 50 (20) | 0.959 | 53.33 (12) | 44.44 (10) | 0.629 | 68.9 (15) | 63.3 (20) | 0.564 | |

| Sexual interest (women) | 25 | 34.5 | 0.039* | 5.55 (12) | 20.83 (16) | 0.053 | 83.33 (4) | 88.89 (5) | 0.715 | 83.3 (6) | 73.3 (5) | 0.662 | |

| Symptom scales | Urinary frequency | 23 | 24 | 0.650 | 11.90 | 19.44 | 0.516 | NR | NR | NR | 38.90 | 28.40 | 0.101 |

| Blood + mucus stool | 1 | 3 | 0.102 | 4.76 | 0.92 | 0.183 | NR | NR | NR | 3.70 | 3.70 | 1.000 | |

| Stool frequency | 19 | 19.5 | 0.860 | 19.79 | 17.12 | 0.440 | 25.64 | 36.11 | 0.327 | 36.50 | 30.70 | 0.556 | |

| Urinary incontinence | 15 | 15.5 | 0.910 | 2.04 | 3.70 | 0.674 | 8.33 | 8.89 | 0.919 | 7.40 | 9.90 | 0.886 | |

| Dysuria | 4.5 | 4 | 0.903 | 2.04 | 1.85 | 0.771 | 4.44 | 6.67 | 0.765 | 2.50 | 1.20 | 0.556 | |

| Abdo pain | 7.5 | 13 | 0.053 | 8.16 | 11.11 | 0.329 | 11.11 | 28.89 | 0.044* | 10.30 | 7.40 | 0.643 | |

| Buttock pain | 9.5 | 11 | 0.472 | 14.28 | 2.77 | 0.011* | 18.75 | 28.89 | 0.335 | 24.70 | 12.30 | 0.114 | |

| Bloating | 18 | 24.5 | 0.061 | 17.68 | 12.96 | 0.362 | 14.58 | 37.78 | 0.042* | 14.80 | 14.80 | 1.000 | |

| Dry mouth | 19 | 26 | 0.087 | 18.36 | 10.18 | 0.387 | NR | NR | NR | 29.80 | 8.60 | 0.156 | |

| Hair loss | 12.5 | 10 | 0.581 | 2.72 | 1.85 | 0.896 | NR | NR | NR | 9.90 | 0.00 | 0.010* | |

| Taste | 9.1 | 9 | 0.821 | 4.16 | 0.00 | 0.047* | NR | NR | NR | 17.30 | 6.20 | 0.083 | |

| Flatulence | 70 | 66 | 0.940 | 32.65 | 26.85 | 0.392 | 51.28 | 47.22 | 0.788 | 41.00 | 39.70 | 0.975 | |

| Faecal incontinence | 8 | 19 | 0.860 | 20.40 | 13.88 | 0.133 | 28.20 | 33.33 | 0.688 | 33.30 | 16.70 | 0.032* | |

| Sore skin | 14 | 14 | 0.992 | 14.96 | 7.40 | 0.128 | 20.51 | 13.89 | 0.527 | 26.90 | 7.70 | 0.023* | |

| Embarrassment | 9 | 11 | 0.695 | 10.20 | 8.33 | 0.318 | NR | NR | NR | 38.50 | 28.20 | 0.180 | |

| Impotence | 49 | 53 | 0.154 | 50.45 (37) | 48.33 (20) | 0.767 | 51.85 (12) | 66.67 (10) | 0.472 | 41.0 (13) | 51.0 (17) | 0.483 | |

| Dyspareunia | 7 | 10 | < 0.001* | 0 (12) | 2.08 (16) | 0.802 | 8.33 (4) | 13.33 (5) | 0.761 | 7.4 (9) | 8.3 (5) | 0.905 | |

Table 4.

EORTC QLQ-C30

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | Kyong Ha et al. [45] (2021) | Bjoern et al. [41] (2019) | Mora et al. [47] (2018) | Veltcamp Helbach et al. [42] (2018) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaTME | LaTME | p | TaTME | LaTME | p | TaTME | LaTME | p | TaTME | LaTME | p | ||

| Global health status | 66.67 | 66.67 | 0.456 | 77.72 | 79.86 | 0.625 | 73.96 | 72.62 | 0.874 | 79.60 | 83.60 | 0.208 | |

| Functional scales | Physical | 100 | 100 | 0.937 | 88.29 | 89.81 | 0.688 | 92.50 | 86.67 | 0.273 | 83.20 | 88.10 | 0.128 |

| Role | 100 | 100 | 0.280 | 84.69 | 85.18 | 0.772 | 91.67 | 79.76 | 0.255 | 80.20 | 89.50 | 0.042* | |

| Emotional | 100 | 100 | 0.368 | 87.07 | 93.51 | 0.041* | 89.58 | 77.38 | 0.031* | 89.40 | 90.10 | 0.887 | |

| Cognitive | 100 | 100 | 0.304 | 90.47 | 95.83 | 0.069 | 85.42 | 83.33 | 0.775 | 89.40 | 90.10 | 0.860 | |

| Social | 100 | 100 | 0.464 | 88.43 | 93.51 | 0.272 | 91.67 | 86.90 | 0.604 | 87.70 | 92.60 | 0.093 | |

| Symptom scales | Fatigue | 0 | 0 | 0.684 | 48.63 | 44.44 | 0.392 | 15.97 | 22.61 | 0.462 | 26.50 | 14.00 | 0.021* |

| N&V | 0 | 0 | 0.357 | 2.04 | 1.38 | 0.978 | 1.04 | 0.00 | 0.359 | 3.10 | 2.50 | 0.987 | |

| Pain | 0 | 0 | 0.491 | 10.20 | 8.79 | 0.645 | 5.20 | 13.09 | 0.235 | 12.8 | 3.70 | 0.051 | |

| Dyspnoea | 0 | 0 | 0.489 | 12.24 | 4.62 | 0.063 | 16.67 | 14.28 | 0.814 | 23.50 | 9.90 | 0.214 | |

| Insomnia | 0 | 0 | 0.300 | 18.36 | 14.81 | 0.449 | 14.58 | 21.42 | 0.426 | 18 | 14.80 | 0.385 | |

| Appetite Loss | 0 | 0 | 0.295 | 10.88 | 2.77 | 0.052 | 12.50 | 2.38 | 0.190 | 7.40 | 2.50 | 0.358 | |

| Constipation | 0 | 0 | 0.491 | 10.88 | 6.48 | 0.549 | 22.92 | 33.33 | 0.381 | 8.60 | 9.90 | 0.763 | |

| Diarrhoea | 0 | 0 | 0.861 | 17.68 | 4.62 | 0.009* | 14.60 | 23.80 | 0.372 | 16 | 3.70 | 0.070 | |

| Financial difficulties | 0 | 0 | 0.286 | 1.36 | 0.00 | 0.223 | NR | NR | NR | 14.80 | 2.40 | 0.032* | |

Functional outcomes

LARS

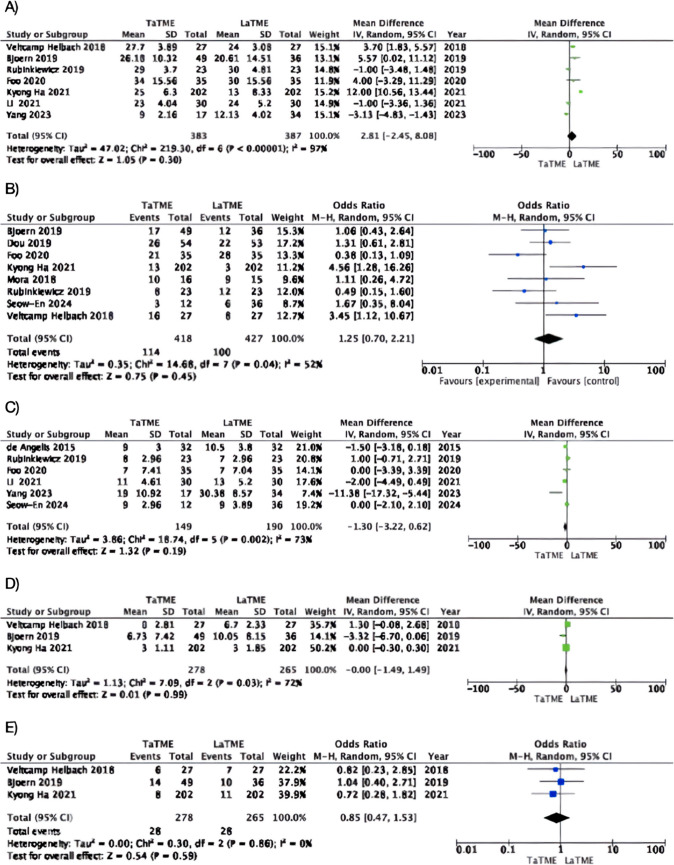

Seven studies [41, 42, 45, 46, 48–50] (taTME group n = 421; LaTME group n = 421) examined LARS scores (Table 1s), revealing a mean score of 26.24 ± 5.32 in the taTME group and 23.84 ± 25.53 in the LaTME group. No statistically significant distinction emerged between the two groups, although the mean difference (MD) favoured the taTME group (MD: 2.81, 95% CI: − 2.45 – 8.08, p= 0.3; I2 = 97%) (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of mean differences of (a) low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) score, (b) low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) major events, (c) Wexner score, (d) International Prostate Syndrome Core (IPSS), (e) International Prostate Syndrome Core (IPSS) comparison in case of moderate and severe symptoms; TaTME transanal total mesorectal excision, LaTME laparoscopic total mesorectal excision

The present analysis shows substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 97%). After removing two studies [42, 45], heterogeneity decreased significantly to 67%. This suggests that these studies were major contributors to the overall variability. Significantly, the overall results of the meta-analysis did not change after their removal (MD: -0.43, 95% CI: − 2.81 – 1.96, p = 0.73; I2 = 67%).

Overall, 27.27% of taTME patients and 23.42% of LaTME patients reported major LARS. In this case, as well, the analysis of the population with major LARS does not show statistical significance between taTME and LaTME groups (OR: 1.25, CI: 0.7 – 2.21, p = 0.45; I2 = 54%).

Jorge-Wexner scale

Six studies [19, 44, 46, 48–50] (taTME group n = 149; LaTME group n = 190) assessed the severity of fecal incontinence using the Jorge-Wexner score [33] (Table 1s). While the average score was slightly lower for the taTME group (10.29) compared to the LaTME group (12.41), this difference was not statistically significant (MD: -1.3, 95% CI: -3.22 to 0.62, p = 0.19) (Fig. 2b). Moderate inconsistency in results across studies (I2 = 73%) was noted.

IPSS

Three studies [41, 42, 45] (taTME group n = 278; LaTME group n = 265) provided data on IPSS [32] (Table 2s) in patients undergoing taTME and LaTME. The IPSS score is 5.8 ± 2.67 in the taTME group and 5.81 ± 3.34 in the LaTME group. Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences between the two groups, with the mean difference (MD) favouring the taTME group (MD: 0.0, 95% CI: − 1.49 – 1.49, p = 0.99; I2 = 72%) (Fig. 2d).

A total of 28 (10.07%) patients in the taTME group and 28 (10.56%) patients in the LaTME group exhibited moderate or severe IPSS symptoms. Statistical analysis between these subgroups revealed no significant disparities between the two groups, with the mean difference (MD) favouring the taTME group (MD: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.47–1.53, p = 0.52; I2 = 0%) (Fig. 2e).

EORTC QLQ-C29

Four studies [41, 42, 47, 50] (taTME group n = 122; LaTME group n = 108) reported the QLQ-C29 questionnaire results [34] (Table 3). The assessment revealed that sexual interest (women), dyspareunia, buttock pain, altered taste, hair loss, fecal incontinence, and sore skin were significantly more prevalent in the taTME group (p = 0.039, < 0.001, 0.011, 0.047, 0.010, 0.032, and 0.023, respectively). In contrast, abdominal pain and bloating were significantly more frequent in the LaTME group (p = 0.044 and 0.042, respectively).

EORTC QLQ-C30

Four studies [41, 42, 45, 47] (taTME group n = 294; LaTME group n = 280) reported the QLQ-C30 questionnaire [35, 36] results (Table 4). The questionnaire indicated that diarrhea, fatigue, and financial difficulties were significantly more common in the LaTME group (p = 0.009, 0.021, and 0.032). Additionally, role functioning improved considerably in the LaTME group (p = 0.042). Emotional function yielded conflicting significant results in two studies, with Bjoern et al. [41] favouring LaTME (p = 0.041) and Mora et al. [47] favouring taTME (p = 0.031). Across all studies, we noted no statistically significant differences in global health status scores.

Discussion

Quality of life and functional outcomes have been recognized as crucial outcome measures after TME surgery, alongside traditional oncological endpoints. This meta-analysis aimed to compare the functional outcomes and QoL between patients undergoing LaTME and taTME. The results indicate that the two techniques provide similar overall functional outcomes, with no statistically significant differences across various scoring systems and QoL questionnaires. Similar conclusions have been reached by Choy KT et al., who reported comparable functional outcomes with both surgical techniques, including LARS, incontinence scores, and QoL [23]. Transanal TME has recently emerged as an effective technique for treating tumors located in the lower rectum. This approach involves a bottom-up dissection starting transanally, which allows for precise establishment of the distal margin and facilitates dissection in anatomically challenging areas such as a narrow pelvis or patients with obesity.

Although the technique is associated with favorable short-term oncological outcomes and low conversion rates to open surgery [51], concerns have been rising regarding poor-postoperative functional outcomes due to the low anastomosis and the potential damage to the anal sphincter complex caused by the sustained dilation required during the procedure. Studies have shown that both taTME and LaTME result in decreased anal sphincter pressures postoperatively, with significant reductions observed in squeeze pressures [24, 25]. However, these changes do not appear to differ significantly between the taTME and LaTME approaches, suggesting that the transanal approach does not inherently confer a higher risk of sphincter damage than the laparoscopic approach [23, 24].

Furthermore, the long-term follow-up studies indicate that the initial postoperative deterioration in sphincter function may improve over time, with no significant differences in anorectal manometry outcomes between taTME and LaTME after extended periods [24, 25].

Using validated questionnaires, a phase II North American multicenter prospective observational trial assessed 100 patients after taTME for rectal cancer. The study revealed that defecatory function and fecal continence initially worsened post-ileostomy closure but showed significant improvement by 12–18 months, although they did not return to preoperative status. Urinary function remained stable, while sexual function declined and did not improve by 18 months post-taTME [52].

The results of this study showed that the LARS score did not significantly differ between taTME and LaTME. However, the taTME group had a slightly higher mean LARS score, indicating more severe bowel dysfunction, though this difference was not statistically significant. This suggests that while taTME may offer surgical advantages, it does not necessarily result in better bowel functional outcomes than LaTME. The high heterogeneity (I2 = 97%) among studies indicates variability in results, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. The high heterogeneity across studies can be attributed to variations in study design, differences in patient populations, variations in surgical techniques within the same approach (taTME or LaTME), the use of different questionnaires and scoring systems with inherent subjectivity, and varying lengths of follow-up. Similarly, the Jorge-Wexner scores did not differ significantly between groups, with taTME showing a slightly lower mean score, indicating less incontinence. However, this difference was still not statistically significant. Moderate inconsistency (I2 = 73%) suggests variability in findings across different studies investigating the same outcome measures, complicating the final interpretation of these findings.

Comparable results were also reported in studies that evaluated anorectal function using manometry in LaTME vs taTME patients. In particular, Bjoern & Perdawood report on similar mean resting pressure at anorectal manometry between taTME and LaTME (36.44 mmHg ± 18.514 vs. 36.58 mmHg ± 13.318, respectively, p = 0.981). Squeeze pressures were also comparable between the groups (125.00 mmHg ± 66.141 vs. 111.83 mmHg ± 51.111, respectively, p = 0.533). These findings suggest that the internal sphincter function is similarly impaired following both surgical techniques, while the external sphincter function remains within normal ranges [24]. De Simone et al. also evaluated anorectal function and QoL of 33 patients who underwent taTME surgery for mid- or low rectal cancer and completed a 12-month follow-up using questionnaires, anorectal manometry, and 3D endoanal ultrasonography (3D-EAUS). All the evaluations were performed before and after surgery, allowing for a homogenous comparison. At manometry, results showed a statistically significant decrease in mean resting pressure at the 12-month follow-up (from 40.7 mmHg to 32.2 mmHg, p = 0.012). However, maximum resting pressure and maximum squeeze pressure did not change significantly. At the 3D-EAUS, 15% of patients showed increased inhomogeneity of the sphincter fibers, which could indicate some degree of muscle damage or alteration [53].

In terms of sexual function, limited data exists, but the available studies indicate no significant differences between the two techniques. Sexual dysfunction following taTME for rectal cancer is a recognized complication with varying impacts on erectile and ejaculatory functions. Studies indicate that sexual dysfunction, including reduced erectile function and ejaculatory problems, is common postoperatively. Interestingly, Nishizawa Y et al. reported significant erectile dysfunction in 80% of men at three months postoperatively, which slightly improved to 76% at 12 months [54]. Another study highlighted that sexual impairment after taTME remains a serious concern, with nearly half of the patients experiencing impaired spontaneous erectile function [55].

Conversely, Pontallier A. et al. demonstrated a better erectile function with a significantly higher rate of sexual activity in the transanal group compared to the conventional laparoscopic approach (71% vs 39%, p = 0.02) [56].

In our study, the EORTC QLQ-C29 demonstrated that a low sex drive in women and dyspareunia were significantly more prevalent in the taTME group. Conversely, in men, sexual interest and potency were preserved. Regarding urogenital function, there is no clear evidence that taTME results in more dysfunction than LaTME. Both techniques are associated with similar IPSS scores, suggesting comparable impact on urogenital function. In our analysis, both groups had similar mean IPSS scores, and the distribution of moderate or severe symptoms was comparable, indicating that neither surgical technique has a clear advantage in preserving urogenital function. However, the high variability and subjective nature of these assessments warrant caution in interpretation. Similar conclusions have been reached by Bjoern et al. using the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Male/Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (ICIQ-MLUTS/FLUTS). No significant differences in urinary function or bother scores between baseline and follow-ups were found. However, a trend towards increased urinary incontinence and total bother scores was observed in male patients at the second follow-up at 13.5 months (p = 0.060 and p= 0.052, respectively) [24].

Our meta-analysis has several limitations. First, the high heterogeneity of the included studies, as indicated by the variability in the LARS and Jorge-Wexner scores, prevents drawing definitive conclusions. This variability may originate from differences in study designs, patient populations, distance of the tumor from anal verge, neo- and adjuvant regimens, variations in surgical techniques, in the timeline of administered questionnaires to assess patient functional status after surgery, and perioperative care protocols. Second, the reliance on subjective scoring systems such as LARS, Jorge-Wexner, and IPSS introduces the potential for bias and variability in patient self-reporting, which may overestimate or underestimate the true impact on functional outcomes and quality of life. Additionally, the lack of long-term follow-up data limits our understanding of the prolonged effects of taTME and LaTME on urogenital and sexual function. Finally, the limited number of studies specifically assessing sexual function further limits the comprehensiveness of our findings in this important aspect of patient well-being. Future research should address these limitations by incorporating more objective measures, like pre- and post-operative anorectal manometry and endoanal ultrasound, ensuring consistent methodologies, and extending the follow-up period to capture long-term outcomes.

Conclusions

Functional outcomes and QoL are similar for rectal cancer patients who underwent either taTME or LaTME. However, the evidence is limited by the heterogeneity of studies and the reliance on subjective outcome measures. Further research is needed to confirm these findings and better understand the long-term impact of the possible functional sequelae of these surgical approaches.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Milano within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This study has received no funding or financial support.

Author contributions

SL and FB wrote the main manuscript text, and DC and FMC prepared the Figures. RC and PS reviewed the manuscript, which was then reviewed by all authors.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Milano within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. There is nothing to declare.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Sara Lauricella and Francesco Brucchi shares the first authorship.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.You YN, Hardiman KM, Bafford A, Poylin V, Francone TD, Davis K, Paquette IM, Steele SR, Feingold DL (2020) The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Rectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 63:1191–1222. 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penna M, Buchs NC, Bloemendaal AL, Hompes R (2016) Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer: The Journey towards a New Technique and Its Current Status. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 16:1145–1153. 10.1080/14737140.2016.1240040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sylla P, Rattner DW, Delgado S, Lacy AM (2010) NOTES Transanal Rectal Cancer Resection Using Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery and Laparoscopic Assistance. Surg Endosc 24:1205–1210. 10.1007/s00464-010-0965-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vignali A, Elmore U, Milone M, Rosati R (2019) Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision (TaTME): Current Status and Future Perspectives. Updat Surg 71:29–37. 10.1007/s13304-019-00630-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gloor S, Pozza G, Troller R, Wehrli M, Adamina M (2023) Surgical Outcomes, Long-Term Recurrence Rate, and Resource Utilization in a Prospective Cohort of 165 Patients Treated by Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision for Distal Rectal Cancer. Cancers 15:1190. 10.3390/cancers15041190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng JY, Chen C-C (2022) Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer: It’s Come a Long Way and Here to Stay. Ann Coloproctology 38:283–289. 10.3393/ac.2022.00374.0053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emile SH, Lacy FBD, Keller DS, Martin-Perez B, Alrawi S, Lacy AM, Chand M (2018) Evolution of Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer: From Top to Bottom. World J Gastrointest Surg 10:28–39. 10.4240/wjgs.v10.i3.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang T, Ma J, Zheng M (2021) Controversies and Consensus in Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision (taTME): Is It a Valid Choice for Rectal Cancer? J Surg Oncol 123:S59–S64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yi Chi Z, Gang O, Xiao Li F, Ya L, Zhijun Z, Yong Gang D, Dan R, Xin L et al (2024) Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision versus Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision for Mid and Low Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 103:e36859. 10.1097/MD.0000000000036859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aubert M, Mege D, Panis Y (2020) Total Mesorectal Excision for Low and Middle Rectal Cancer: Laparoscopic versus Transanal Approach—a Meta-Analysis. Surg Endosc 34:3908–3919. 10.1007/s00464-019-07160-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ren J, Luo H, Liu S, Wang B, Wu F (2021) Short- and Mid-Term Outcomes of Transanal versus Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision for Low Rectal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Ann Surg Treat Res 100:86. 10.4174/astr.2021.100.2.86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lei P, Ruan Y, Yang X, Fang J, Chen T (2018) Trans-Anal or Trans-Abdominal Total Mesorectal Excision? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Recent Comparative Studies on Perioperative Outcomes and Pathological Result. Int J Surg 60:113–119. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ong GKb, Tsai B, Patron RL, Johansen O, Lane F, Melbert RB, Reidy T, Maun D, (2021) Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision Achieves Equivalent Oncologic Resection Compared to Laparoscopic Approach, but with Functional Consequences. Am J Surg 221:566–569. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshimitsu K, Mori S, Tanabe K, Wada M, Hamada Y, Yasudome R, Kurahara H, Arigami T et al (2023) Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision Considering the Embryology Along the Fascia in Rectal Cancer Patients. Anticancer Res 43:3597–605. 10.21873/anticanres.16539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yi X, Zhang X, Li Q, Ouyang J (2023) Comparing Perioperative and Oncological Outcomes of Transanal and Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials and Prospective Studies. Surg Endosc 37:9228–9243. 10.1007/s00464-023-10495-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sparreboom CL, Komen N, Rizopoulos D, Van Westreenen HL, Doornebosch PG, Dekker JWT, Menon AG, Tuynman JB et al (2019) Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision: How Are We Doing so Far? Colorectal Dis 21:767–774. 10.1111/codi.14601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu W, Xu Z, Cheng H, Ying J, Cheng F, Xu W, Cao J, Luo J (2016) Comparison of Short-Term Clinical Outcomes between Transanal and Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision for the Treatment of Mid and Low Rectal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol EJSO 42:1841–1850. 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perdawood SK, Al Khefagie GAA (2016) Transanal vs Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer: Initial Experience from Denmark. Colorectal Dis 18:51–58. 10.1111/codi.13225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de’Angelis N, Portigliotti L, Azoulay D, Brunetti F, (2015) Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer: A Single Center Experience and Systematic Review of the Literature. Langenbecks Arch Surg 400:945–959. 10.1007/s00423-015-1350-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ourô S, Ferreira M, Roquete P, Maio R (2022) Transanal versus Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision: A Comparative Study of Long-Term Oncological Outcomes. Tech Coloproctology 26:279–290. 10.1007/s10151-022-02570-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z, Liu H, Luo S, Hou Y, Zhou Y, Zheng X, Zhang X, Huang L et al (2024) Long-Term Oncological Outcomes of Transanal versus Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision for Mid-Low Rectal Cancer: A Retrospective Analysis of 2502 Patients. Int J Surg 110:1611–1619. 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heijden JAG, Koëter T, Smits LJH, Sietses C, Tuynman JB, Maaskant-Braat AJG, Klarenbeek BR, Wilt JHW (2020) Functional Complaints and Quality of Life after Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision: A Meta-Analysis. Br J Surg 107:489–498. 10.1002/bjs.11566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choy KT, Yang TWW, Prabhakaran S, Heriot A, Kong JC, Warrier SK (2021) Comparing Functional Outcomes between Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision (TaTME) and Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision (LaTME) for Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 36:1163–1174. 10.1007/s00384-021-03849-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bjoern MX, Perdawood SK (2020) Manometric Assessment of Anorectal Function after Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision. Tech Coloproctology 24:231–236. 10.1007/s10151-020-02147-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.López-Sánchez A, Morandeira-Rivas A, Moreno-Sanz C, Cortina-Oliva FJ, Manzanera-Díaz M, Gonzales-Aguilar JD (2021) Long-Term Anorectal Manometry Outcomes After Laparoscopic and Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 31:395–401. 10.1089/lap.2020.1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McInnes MDF, Moher D, Thombs BD, McGrath TA, Bossuyt PM, and the PRISMA-DTA Group, Clifford T, Cohen JF et al (2018) Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies: The PRISMA-DTA Statement. JAMA 319:388. 10.1001/jama.2017.19163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, et al (2017). AMSTAR 2: A Critical Appraisal Tool for Systematic Reviews That Include Randomised or Non-Randomised Studies of Healthcare Interventions, or Both. BMJ: j4008. 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Brooke BS, Schwartz TA, Pawlik TM (2021) MOOSE Reporting Guidelines for Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies. JAMA Surg 156:787. 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A (2016) Rayyan—a Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst Rev 5:210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S (2012) Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Score: Development and Validation of a Symptom-Based Scoring System for Bowel Dysfunction After Low Anterior Resection for Rectal Cancer. Ann Surg 255:922–928. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824f1c21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juul T, Ahlberg M, Biondo S, Emmertsen KJ, Espin E, Jimenez LM, Matzel KE, Palmer G et al (2014) International Validation of the Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Score. Ann Surg 259:728–734. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828fac0b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wadie BS, Ibrahim E-HI, De La Rosette JJ, Gomha MA, Ghoneim MA (2001) The relationship of the international prostate symptom score and objective parameters for diagnosing bladder outlet obstruction. Part i: when statistics fail. J Urol 165:32–34. 10.1097/00005392-200101000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jorge MJN, Wexner SD (1993) Etiology and Management of Fecal Incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 36:77–97. 10.1007/BF02050307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganesh V, Agarwal A, Popovic M, Cella D, McDonald R, Vuong S, Lam H, Rowbottom L et al (2016) Comparison of the FACT-C, EORTC QLQ-CR38, and QLQ-CR29 Quality of Life Questionnaires for Patients with Colorectal Cancer: A Literature Review. Support Care Cancer 24:3661–3668. 10.1007/s00520-016-3270-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sprangers MAG, Cull A, Groenvold M, Bjordal K, Blazeby J, Aaronson NK (1998) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Approach to Developing Questionnaire Modules: An Update and Overview. EORTC Quality of Life Study Group. Qual Life Res 7:291–300. 10.1023/A:1008890401133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H et al (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A Quality-of-Life Instrument for Use in International Clinical Trials in Oncology. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 85:365–376. 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T (2014) Estimating the Sample Mean and Standard Deviation from the Sample Size, Median, Range and/or Interquartile Range. BMC Med Res Methodol 14:135. 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF et al (2011) The Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 343:d5928–d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wells, GA, Wells, G, Shea, B, Shea, B, O’Connell, D, Peterson, J, Welch, Losos, M, Tugwell, P, Ga, SW, Zello, GA, Petersen JA (2014) The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Non-Randomized Studies in Meta-Analysis. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 40.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (2023) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4 (Updated August 2023). Cochrane. 10.1002/9781119536604

- 41.Bjoern MX, Nielsen S, Perdawood SK (2019) Quality of Life After Surgery for Rectal Cancer: A Comparison of Functional Outcomes After Transanal and Laparoscopic Approaches. J Gastrointest Surg 23:1623–1630. 10.1007/s11605-018-4057-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veltcamp Helbach M, Koedam TWA, Knol JJ, Velthuis S, Bonjer HJ, Tuynman JB, Sietses C (2019) Quality of Life after Rectal Cancer Surgery: Differences between Laparoscopic and Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision. Surg Endosc 33:79–87. 10.1007/s00464-018-6276-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dou R, Sun W, Luo S, Hou Y, Zhang C, Kang L (2019) Comparison of postoperative bowel function between patients undergoing transanal and laparoscopic total mesorectal excision. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi Chin J Gastrointest Surg 22:246–254 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seow-En I, Wu J, Tan IE-H, Zhao Y, Seah AWM, Wee IJY, Ying-Ru Ng Y, Kwong-Wei Tan E (2024) Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision With Delayed Coloanal Anastomosis (TaTME-DCAA) Versus Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision (LTME) and Robotic Total Mesorectal Excision (RTME) for Low Rectal Cancer: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis of Short-Term Outcomes, Bowel Function, and Cost. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 34:54–61. 10.1097/SLE.0000000000001247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ha RK, Park SC, Park B, Park SS, Sohn DK, Chang HJ, Oh JH (2021) Comparison of Patient-Reported Quality of Life and Functional Outcomes Following Laparoscopic and Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision of Rectal Cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res 101:1. 10.4174/astr.2021.101.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Foo CC, Kin Ng K, Tsang JS, Siu-hung Lo O, Wei R, Yip J, Lun Law W (2020) Low Anterior Resection Syndrome After Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision: A Comparison With the Conventional Top-to-Bottom Approach. Dis Colon Rectum 63:497–503. 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mora L, Zarate A, Serra-Aracil X, Pallisera A, Serra S, Navarro-Soto S (2019) Afectación funcional y calidad de vida tras cirugía de cáncer rectal. Cir Cir 86:868. 10.24875/CIRU.M18000022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rubinkiewicz M, Zarzycki P, Witowski J, Pisarska M, Gajewska N, Torbicz G, Nowakowski M, Major P et al (2019) Functional Outcomes after Resections for Low Rectal Tumors: Comparison of Transanal with Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision. BMC Surg 19:79. 10.1186/s12893-019-0550-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang W-F, Chen W, He Z, Wu Z, Liu H, Li G, Li W-L (2023) Simple Transanal Total Mesorectal Resection versus Laparoscopic Transabdominal Total Mesorectal Resection for the Treatment of Low Rectal Cancer: A Single-Center Retrospective Case-Control Study. Front Surg 10:1171382. 10.3389/fsurg.2023.1171382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Y, Bai X, Niu B, Zhou J, Qiu H, Xiao Y, Lin G (2021) A Prospective Study of Health Related Quality of Life, Bowel and Sexual Function after TaTME and Conventional Laparoscopic TME for Mid and Low Rectal Cancer. Tech Coloproctology 25:449–459. 10.1007/s10151-020-02397-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Penna M, Hompes R, Arnold S, Wynn G, Austin R, Warusavitarne J, Moran B, Hanna GB et al (2017) Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision: International Registry Results of the First 720 Cases. Ann Surg 266:111–117. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Donovan KF, Lee KC, Ricardo A, Berger N, Bonaccorso A, Alavi K, Zaghiyan K, Pigazzi A et al (2024) Functional Outcomes After Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision (taTME) for Rectal Cancer: Results from the Phase II North American Multicenter Prospective Observational Trial. Ann Surg. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000006374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Simone V, Persiani R, Biondi A, Litta F, Parello A, Campennì P, Orefice R, Marra A et al (2021) One-Year Evaluation of Anorectal Functionality and Quality of Life in Patients Affected by Mid-to-Low Rectal Cancer Treated with Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision. Updat Surg 73:157–164. 10.1007/s13304-020-00919-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nishizawa Y, Ito M, Saito N, Suzuki T, Sugito M, Tanaka T (2011) Male Sexual Dysfunction after Rectal Cancer Surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 26:1541–1548. 10.1007/s00384-011-1247-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sartori CA, Sartori A, Vigna S, Occhipinti R, Baiocchi GL (2011) Urinary and Sexual Disorders After Laparoscopic TME for Rectal Cancer in Males. J Gastrointest Surg 15:637–643. 10.1007/s11605-011-1459-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pontallier A, Denost Q, Van Geluwe B, Adam J-P, Celerier B, Rullier E (2016) Potential Sexual Function Improvement by Using Transanal Mesorectal Approach for Laparoscopic Low Rectal Cancer Excision. Surg Endosc 30:4924–4933. 10.1007/s00464-016-4833-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.