Abstract

Multiple myeloma is a hematological malignancy arising from immunoglobulin-secreting plasma cells. It remains poorly understood how chromatin rewiring of regulatory elements contributes to tumorigenesis and therapy resistance in myeloma. Here we generate a high-resolution contact map of myeloma-associated super-enhancers by integrating H3K27ac ChIP-seq and HiChIP from myeloma cell lines, patient-derived myeloma cells and normal plasma cells. Our comprehensive transcriptomic and phenomic analyses prioritize candidate genes with biological and clinical implications in myeloma. We show that myeloma cells frequently acquire SE that transcriptionally activate an oncogene PPP1R15B, which encodes a regulatory subunit of the holophosphatase complex that dephosphorylates translation initiation factor eIF2α. Epigenetic silencing or knockdown of PPP1R15B activates pro-apoptotic eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP pathway, while inhibiting protein synthesis and immunoglobulin production. Pharmacological inhibition of PPP1R15B using Raphin1 potentiates the anti-myeloma effect of bortezomib. Our study reveals that myeloma cells are vulnerable to perturbation of PPP1R15B-dependent protein homeostasis, highlighting a promising therapeutic strategy.

Subject terms: Myeloma, Epigenomics

The role of chromatin rewiring of regulatory elements in multiple myeloma (MM) remains poorly understood. Here, the authors identify a super-enhancer driven gene, PPP1R15B whose perturbation confers vulnerability in MM cells and suggest it as a therapeutic target.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most common hematological malignancy characterized by clonal expansion of malignant plasma cells within the bone marrow1. With the recent development of anti-myeloma therapies including proteasome inhibitors (PIs; bortezomib, carfilzomib, ixazomib), immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs; thalidomide, lenalidomide, pomalidomide), as well as monoclonal antibodies (mAbs; elotuzumab, daratumumab), there has been a significant improvement in the overall survival of patients with MM2,3. However, majority of the patients fail to achieve long-lasting complete remission, necessitating the search for novel therapeutic targets4.

Super-enhancers (SEs) are large clusters of putative enhancers densely occupied by mediators and transcription-regulating proteins that evoke stronger transcriptional activation compared to typical enhancers5. Several oncogenic drivers, such as MYC, MAF, NSD2 and CCND1/2/3, were found to be associated with enhancer hijacking in MM6–8. Moreover, SE deregulation alters the transcription factor (TF) repertoire associated with B-lineage commitment and oncogenic transcriptional programs, including NF-κB pathway, unfolded protein response (UPR) and hypoxia response9,10.

Accumulating evidence has shown that reconfiguration of the three-dimensional (3D) chromatin architecture rewires enhancer-promoter interactions and orchestrates disease-associated transcriptional reprogramming11–13. However, it remains elusive how 3D enhancer connectomes are altered and mediate transcriptional dysregulation in MM. Previous studies have indicated that enhancers may not exert transcriptional effects on the nearest gene but can interact with distal target genes located even hundreds of kilobases away14–16, making it challenging to predict SE target genes solely based on linear proximity. Chromosome conformation capture-based assays have emerged as powerful tools for visualizing spatial contacts between putative enhancers and promoters17. H3K27ac HiChIP enables genome-wide detection of chromatin loops between enhancers and promoters.

In view of the secretory origin, myeloma cells are highly evolved with the capacity to cope with a high abundance of monoclonal immunoglobulins and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress by activating the UPR pathways. In response to accumulated misfolded proteins, global translational repression is rapidly induced through the activation of PERK and subsequent phosphorylation of eIF2α, thereby limiting the availability of the translation initiation ternary complex through inhibition of the guanine exchange factor activity of eIF2B. The translational recovery is accomplished through dephosphorylation of eIF2α by protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) holoenzyme and its regulatory subunits including the constitutively expressed PPP1R15B (CReP) and stress-induced PPP1R15A (GADD34)18,19. The high dependence on elevated UPR for survival represents a vulnerability of MM, whereas unresolved ER stress activates terminal UPR that ultimately promotes apoptosis.

In this work, we interrogate the 3D chromatin contacts of SEs and their target genes in MM based on H3K27ac ChIP-seq and HiChIP. By leveraging transcriptomic and phenomic databases, we derive a prioritized list of candidate SE-driven genes with biological and clinical implications in MM. Further, we identify a SE-associated oncogene, PPP1R15B, which functions to protect myeloma cells against ER stress-induced apoptosis while promoting immunoglobulin synthesis. Our study reveals promising therapeutic potential of targeting PPP1R15B and/or eIF2α dephosphorylation for MM treatment.

Results

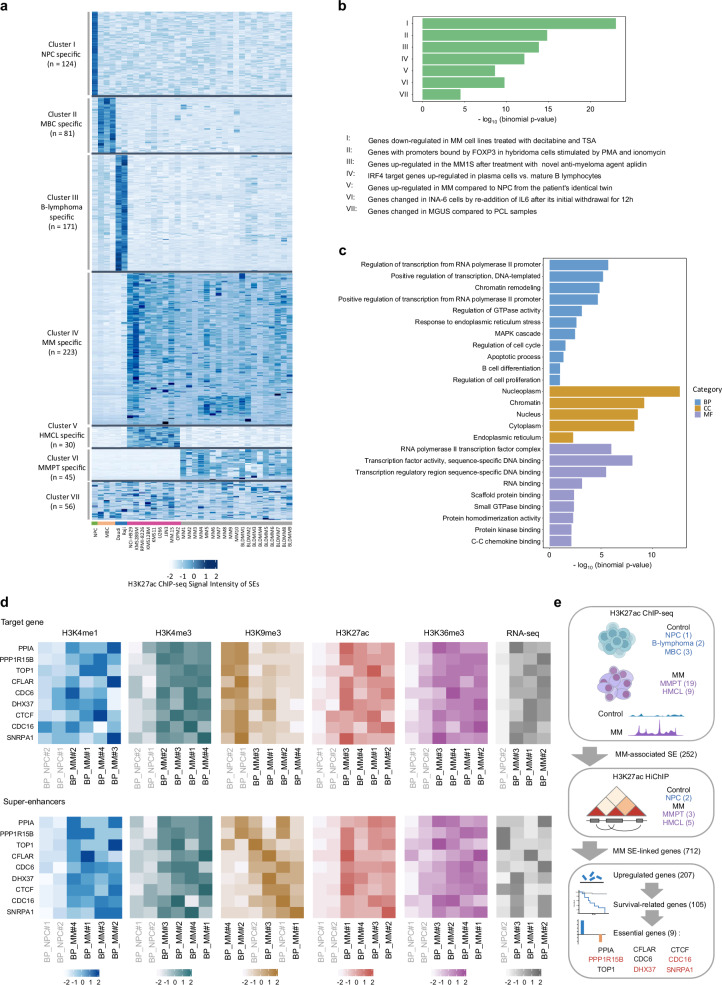

Enhancer connectomes in multiple myeloma link super-enhancers to functionally important genes

SEs are clustered enhancers characterized by exceptionally high enrichment for H3K27ac, which have been associated with oncogenic transcriptional addiction20,21. We and others have previously profiled the SE landscape in MM based on the H3K27ac ChIP-seq data from 19 MM patient samples (MM1-10, BLDMM1-9), nine human myeloma cell lines (HMCLs; NCI-H929, KMS28BM, RPMI-8226, KMS12BM, KMS11, U266, JJN3, MM.1 S, OPM2), together with a group of control cells including a NPC, two B-lymphoma cell lines (Daudi, Raji) and three memory B cell samples (MBC, Supplementary Data 1)9,22. In this study, we superimposed the SEs obtained from the Rank Ordering of Super-enhancers (ROSE) algorithm across all examined samples. We identified 2097 SEs across HMCLs (n = 9), of which 12.0% (252/2097) are unique to a single cell line. Notably, 49.4% of SEs (1036/2097) were recurrently present in at least seven HMCLs (Supplementary Fig. 1a), suggesting a high degree of conservation of SE formation among HMCLs. In MM patients (n = 19), we identified 3406 SEs including 651 SEs (19.1%) detected in only one primary sample. Compared to HMCLs, SEs identified in MM patients exhibited a reduced tendency to be recurrent (Supplementary Fig. 1b), indicating an extensive variation in the SE repertoire among primary samples. However, we observed a significant increase in the frequency of SEs recurrently present in five patients, with more than half of the SEs (61.1%) identified in five or more primary samples. No SEs were conserved across all MM samples in our study. Therefore, we focused on epigenetic alterations of high recurrent SEs that were reliably detected in multiple samples, which accounted for about half of the SEs identified in HMCLs and primary samples. Specifically, 274 nonredundant SEs were recurrently gained in at least seven HMCLs and in at least five myeloma patient cases, relative to control samples (Supplementary Data 2). We further validated and selected SEs that were significantly enriched with H3K27ac signals in HMCLs and primary samples compared to the controls, and vice versa ( | log2FC | > 1, adj. p value < 0.05, Supplementary Data 2). Accordingly, we obtained 223 gained SEs (referred to as MM-associated SEs) and 376 lost SEs (non-MM-associated SEs), which exhibited distinct patterns of H3K27ac (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1. Three-dimensional epigenomic profiling reveals altered super-enhancer engagement in multiple myeloma.

a Heatmap showing H3K27ac enrichment patterns in different clusters of SE across NPC (n = 1), MBC (n = 3), B-lymphoma cell lines (n = 2), HMCLs (n = 9), and MM patient samples (n = 19). Each column represents a sample, which are color-coded by the corresponding sample group (NPC, MBC, B-lymphoma, HMCL, and primary MM). The clusters and the number of SEs specific to each cluster are indicated on the left. b GREAT analysis of genes linked to MM-associated enhancers, showing enriched pathway terms curated from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB). P values were calculated using one-sided Fisher’s exact test and were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. c GO enrichment analysis of genes associated with acquired SEs in MM. Each GO category (BP, CC, MF) is shown. P values were calculated using one-sided Fisher’s exact test and were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. d Heatmaps illustrating the H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K9me3, H3K27ac and H3K36me3 ChIP-seq and RNA-seq patterns from the Blueprint database34–37,54 at the candidate MM SE-associated genes (top panel) and MM-associated SEs (bottom panel) in patient-derived myeloma cells (n = 4) compared to NPCs (n = 2). RNA-seq data (FPKM) is available for three myeloma samples and one NPC sample only. Samples are organized by hierarchical clustering, with labels colored in gray and black highlighting MM patient and normal control samples, respectively. e Schematic representation of the workflow utilized to discover target genes driven by MM SEs and associated with potential clinical relevance. The number of samples or candidate genes is indicated in brackets. The nine prioritized candidate genes that have been characterized in MM are labeled in blue, and other genes are labeled in red. Figure 1 created with BioRender.com released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license. BP biological process, CC cellular component, MF molecular function.

Previous studies have shown the regulatory effects of functional enhancers cannot be solely predicted by H3K27ac-marked enhancer activity; rather, these effects also depend on chromatin loop contact propensity23,24. To map the 3D regulatory landscape of enhancer-promoter interactions, we performed H3K27ac HiChIP in five HMCLs (NCI-H929, KMS28BM, RPMI-8226, U266, MM.1 S) with different molecular subgroups, three patient-derived MM cells and two NPC samples. H3K27ac HiChIP provides a genome-wide contact map of long-range enhancer connectome that allows us to directly link putative SEs to the target genes. Hichipper25 was utilized to call significant chromatin interactions using the previously annotated H3K27ac ChIP-seq narrow and broad peaks as anchors. We identified ~12,700,000–29,500,000 significant interactions in HMCLs (n = 5), ~2,000,000–8,400,000 significant loops in MM patient samples (n = 3), and ~6,860,000-7,200,000 significant chromatin interactions in NPCs (n = 2, Supplementary Data 3). Notably, NPCs exhibit a higher prevalence of both cis long-range and trans interactions in comparison to myeloma samples (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d). This may be attributable to increased number of topologically associating domains (TADs) and smaller average TAD size in myeloma cells26.

Next, we identified genes linked to the gained SEs through H3K27ac HiChIP, and found 1155 SE-associated genes common across all five HMCLs and 809 genes common for primary patient samples, respectively (Supplementary Data 2). Approximately 56.9% (712/1252) of SE-associated genes were found in HMCLs and primary patient samples, not in NPCs (Supplementary Fig. 1e).

Several previously reported SE-associated genes, such as MYC, HJURP, FAM53B and CCND27,27,28, presented strong H3K27ac enrichment and extensive chromatin loops in MM cells (Supplementary Fig. 2). Enhancer hijacking facilitated by prevalent inter-chromosomal translocations in MM was also recapitulated by our data between IgH loci and its translocation partners (MAF, NSD2, CCND1, Supplementary Fig. 3). Of note, we identified approximately fivefold of genes specifically regulated by MM-associated SEs compared to our earlier study22, which assigned putative genes based on linear proximity to the corresponding SEs (Supplementary Fig. 1e). This is in concordant with related work in B cell malignancies suggesting that about half of the SEs control genes beyond their closest neighboring genes along the linear genome29.

We functionally annotated the MM-associated SEs using GREAT30. The top enriched hallmark gene sets were related to IRF4 regulation, MM progression and drug responses (Fig. 1b). Gene ontology (GO) pathway analysis31 of MM-associated SE target genes revealed overrepresented transcriptional regulatory processes and key pathways that feature prominently in MM pathobiology, including cell proliferation, cell survival, MAPK and UPR signaling (Fig. 1c). Notably, the UPR and IRF4 regulatory network in MM fuses with the gene expression programs during B cell activation and plasma cell differentiation32,33. By interrogating the UPR-related genes, we found SE-associated genes involved in the activation of the three UPR branches in MM (IRE1, ATF6, PERK), whereas the PERK arm of the UPR is primarily silenced in plasma cell differentiation (Supplementary Fig. 1f). In addition to a number of SE-associated IRF4 target genes highly expressed in both myeloma cells and NPCs relative to activated B cells, we found several MM-specific IRF4 targets driven by SE32, including MYC, HDAC5 and ITGA4 (Supplementary Fig. 1g). These observations reflect the pleiotropic effects of IRF4 and UPR signaling in MM.

To identify promising target genes driven by MM-associated SEs with biological significance and clinical relevance, an integrated analysis of gene expression and functional profiling was performed. A detailed workflow for candidate gene selection is depicted in Fig. 1e. We first examined the expression of SE-linked genes using the Blueprint RNA-seq dataset34–37. Genes associated with MM-acquired SEs were significantly upregulated in patient-derived MM cells (n = 14) as compared to NPCs (n = 7), underscoring the transcriptional dysregulation mediated by enhancer rewiring (Supplementary Fig. 1h). Most cases of MM, if not all, are preceded by premalignant conditions termed monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), and smoldering MM (SMM), a transitional stage between MGUS and MM. We further analyzed two microarray datasets from independent patient cohorts38,39, which collectively comprised of 20 non-malignant samples, 33 MGUS, 24 SMM, and 206 newly diagnosed MM (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Genes consistently upregulated across the RNA-seq35 and microarray datasets38,39, with available microarray probes corresponding to the relevant genes, were chosen (see Methods), resulting in a refined list of 207 genes transcriptionally activated in MM as compared to the pre-malignancies or healthy controls. Among these genes, 105 (50.7%) genes displayed a significant correlation with poor survival of MM patients from the CoMMpass dataset40 (Supplementary Fig. 4b, c).

To gain insights into the functional non-redundancy and potential therapeutic vulnerabilities of the candidate genes, we queried the CRISPR-Cas9 screening database from Depmap (www.Depmap.org). We thus further narrowed down to a prioritized list of nine essential genes (median CERES score < −0.5, Supplementary Fig. 4d), which includes MM-related genes that have been reported in pre-clinical studies, such as PPIA41, CDC642, CTCF43, CFLAR44 and TOP145, as well as four genes previously uncharacterized in MM, namely DHX37, SNRPA1, CDC16 and PPP1R15B (Fig. 1e). Specifically, DHX37 and SNRPA1 are involved in RNA processing and metabolism, and their significant roles in oncogenesis and metastasis have been reported in solid tumors46–48. CDC16, a component of the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) pivotal for regulating cell cycle transition, remains largely unexplored in MM, but the therapeutic potential of inhibiting APC/C and its co-activator CDC20 has been implicated in MM49. PPP1R15B encodes the constitutively expressed regulatory protein CReP that forms an eIF2α phosphatase complex with PP1. Emerging evidence has suggested the crucial roles of PPP1R15B in cellular stress responses during embryonic development and neurodegenerative disease progression50–52, yet its definitive role in MM remains unclear. Taken together, we leveraged transcriptomic and survival data, along with DepMap CRISPR functional genomics data, to identify transcriptional dependencies associated with recurrently dysregulated SEs in HMCLs and MM patients. More importantly, the discovery of hitherto unexplored SE-driven transcriptional dependencies may point to avenues for the development of targeted therapeutic interventions in MM.

Combinations of different histone modifications can provide instructive cues for chromatin states and transcriptional activities53. We examined the changes in epigenetic characteristics of the shortlisted candidate genes and the cognate SEs domains utilizing the Blueprint ChIP-seq dataset54 obtained from four MM patients and two healthy donors. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of ChIP-seq signals demonstrated distinct patterns of enhancer-specific histone markers (H3K4me1, H3K27ac) at the SE regions in MM and NPCs, corroborating our earlier findings (Fig. 1d). The repressive H3K9me3 mark was mostly absent at the target gene loci in MM cells, whereas notable enrichment of accessible chromatin marks (H3K4me3, H3K36me3) was observed in patient-derived MM cells, indicative of a positive association with transcriptional activation. Collectively, our integrative analysis deciphered the transcriptional regulation facilitated by SE-centered chromatin interactions.

PPP1R15B is a super-enhancer-driven gene in multiple myeloma

We identified nine SE-driven candidate genes through integrative analysis of gene expression level, prognostic value and gene essentiality across multiple datasets35,38–40,54 (Fig. 1e). These include both previously implicated oncogenes and unreported genes that are surmised to play a key role in MM pathobiology. Intriguingly, the transcript levels of most candidate genes showed a moderate to strong correlation with the H3K27ac ChIP-seq signals of the associated SEs, with marginal significance in HMCLs and primary patient samples (r > 0.4, p < 0.1, Supplementary Fig. 4e). These observations support the notion that aberrations in SE activity are associated with transcriptional dysregulation. Of particular interest are PPP1R15B, CFLAR and CDC6, which are among the top genes whose transcriptional activity strongly associated with SE acquisition. In addition, PPP1R15B is associated with one of the most highly recurrent SEs among the candidate genes in both HMCLs and primary patient samples (Supplementary Fig. 4f), reflecting a universal pattern of transcriptional deregulation underlying MM progression. We therefore chose to focus on the functional and mechanistic interrogation of PPP1R15B as a promising SE-driven oncogene in MM.

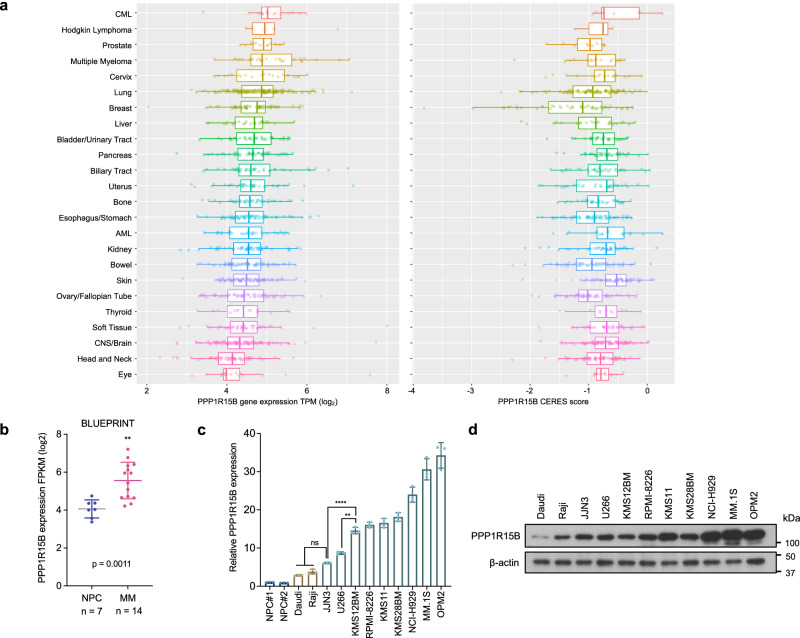

PPP1R15B is a highly expressed essential gene in MM, consistently ranking within the top four across various cancer types (Fig. 2a). On the contrary, the stress-induced paralogue PPP1R15A is not implicated in MM progression, cell survival or molecular vulnerability (Supplementary Fig. 5), highlighting the crucial and non-redundant role of PPP1R15B in MM. We confirmed elevated PPP1R15B expression at both mRNA and protein levels in a panel of HMCLs compared to CD138+ plasma cells from healthy donors and B-lymphoma cell lines (Fig. 2b–d). Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated a persistent overexpression of PPP1R15B (CReP) in patient-derived CD138+ myeloma cells (n = 10) when compared to MGUS (n = 3) and NPC (n = 3, Fig. 3a, b, Supplementary Fig. 6a). The antibody specificity was validated by negative controls without primary antibodies and knockdown/add-back experiments (Supplementary Fig. 6b, c). Notably, we observed a perinuclear and/or cytoplasmic staining pattern of the CReP protein in most myeloma cells. Given that CReP was annotated as an ER/Golgi-localized protein55,56, we co-stained myeloma cells with anti-CReP antibody and ER cytopainter (Supplementary Fig. 6d). Our findings revealed a diffuse cytoplasmic staining of the ER marker that overlapped with the CReP staining, which is consistent with the previous reports that the cytoplasm of plasma cells is replete with dilated rough ER and abundant Golgi apparatus57,58.

Fig. 2. PPP1R15B is overexpressed in multiple myeloma.

a PPP1R15B expression and gene dependency across different types of diseases/tissues (n = 24) using the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE, left) and DepMap (right). Each point represents a cell line. The CERES value at −0.5 is used as the cutoff point for essential gene dependency. Lower CERES score indicates higher gene essentiality. The left and right edges of the box represent the 25th and 75th quartiles, respectively, and the middle line denotes median. The whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range of 25th and 75th quartiles. b PPP1R15B expression level in plasma cells from healthy donors (n = 7) and patients (n = 14) based on the Blueprint database34–37. Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was performed (p value in NPC vs MM = 0.0011). c, d RT-qPCR (c) and western blot (d) analysis of PPP1R15B expression in NPCs (n = 2), B-cell lymphoma cell lines (n = 2) and HMCLs (n = 9). For RT-qPCR, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed (p values in NPC#1 vs JJN3 = 0.0101; NPC#2 vs JJN3 = 0.0078; Daudi vs JJN3 = 0.2883; Raji vs JJN3 = 0.7576; JJN3 vs KMS12BM = 8.24 × 10-6; U266 vs KMS12BM = 0.0018). All western blots are representative of 3 biological replicates. β-actin was used as a loading control. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

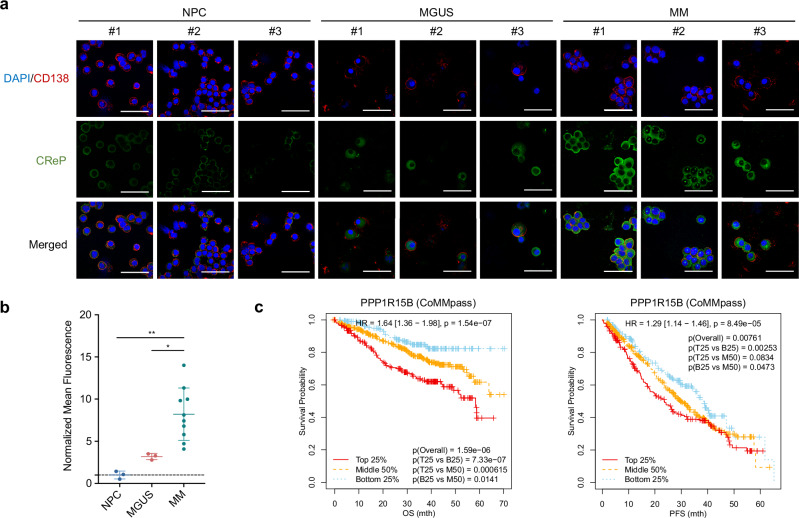

Fig. 3. PPP1R15B is associated with unfavorable patient survival outcomes.

a, b Immunofluorescence analysis of PPP1R15B expression in CD138+ plasma cells from healthy donors (n = 3), MGUS (n = 3) and MM patients (n = 10). Representative images are displayed (a), with the additional samples presented in Supplementary Fig. 6a. Cells were stained for CD138 (red) and PPP1R15B (green), with nuclei counterstain (blue). Immunofluorescence intensity of PPP1R15B protein was quantified (b). Each data point represents the average fluorescence intensity of PPP1R15B in a minimum of 50 cells per donor/patient. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed (p values in NPC vs MGUS = 0.57, NPC vs MM = 0.0027, MGUS vs MM = 0.029). Scale bar: 50 µm. Data are presented as mean ± SD. c Kaplan-Meier survival curves depicting the association of PPP1R15B expression with MM patient overall and progression-free survival based on CoMMpass dataset (n = 958)40. Patients were categorized into groups based on PPP1R15B expression (TPM): top 25% (T25), middle 50% (M50), and bottom 25% (B25). The hazard ratio, along with its confidence interval and log-rank p values, derived from the univariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, are presented. MGUS monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, SMM smoldering multiple myeloma, HR, hazard ratio. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We asked whether aberrant PPP1R15B expression could be related to a specific molecular subgroup of MM using CoMMpass40 and UAMS59 transcriptomic databases. No consistent subgroup-specific differences were observed in the gene expression patterns of PPP1R15B between these two databases, except for the MAF subgroup (Supplementary Fig. 7a). The widespread overexpression of PPP1R15B may represent a universal mechanism involved in ER stress adaptation underlying the development of malignant plasma cells.

Myeloma patients with high PPP1R15B expression were significantly correlated with inferior overall survival (p = 1.59e-06) and progression-free survival (p = 0.00761) based on the analysis of CoMMpass dataset40 (Fig. 3c). Multivariate Cox proportional hazard model analysis revealed that PPP1R15B was an independent prognostic factor for overall survival, but not for progression-free survival in MM patients (Supplementary Table 2), altogether indicating the role of PPP1R15B in myeloma progression and disease aggressiveness.

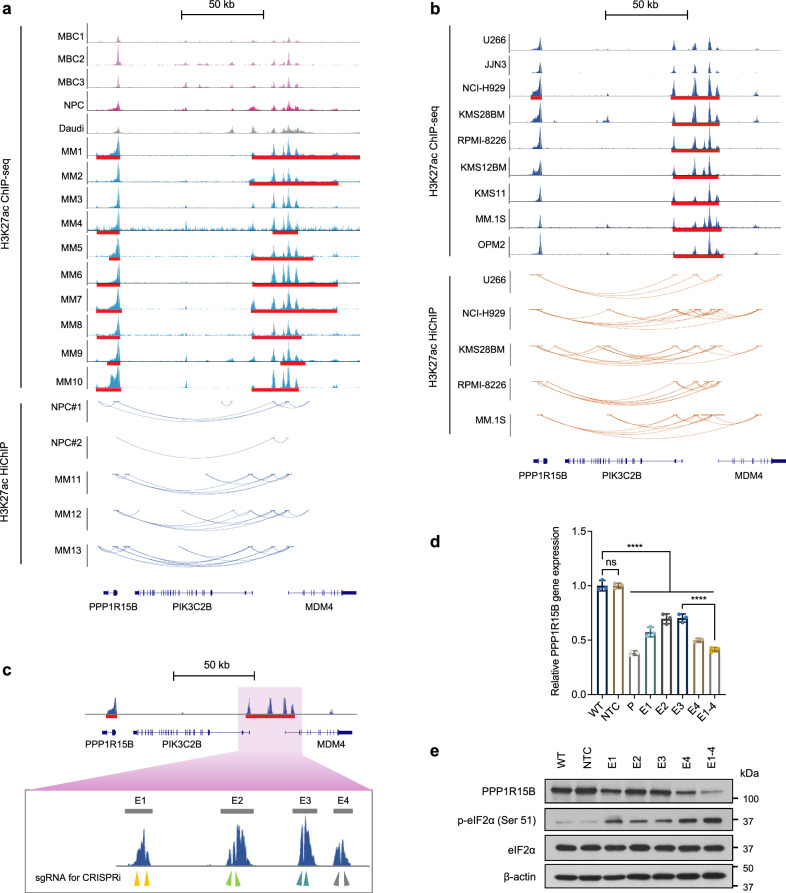

PPP1R15B is transcriptionally activated via long-range enhancer-promoter interactions

To explore the transcriptional control mechanisms governing PPP1R15B, we examined the H3K27ac ChIP-seq signals and HiChIP loops within the genomic region encompassing PPP1R15B in both MM patient samples and cell lines. We observed a prominent enrichment of H3K27ac signals within the gene body of PPP1R15B, accompanied by the presence of a distal SE approximately 80 kb upstream of the PPP1R15B transcription start site (TSS) in majority of MM patients and cell lines (Fig. 4a, b). Notably, we did not observe structural variations at the PPP1R15B locus and its cognate SE regions in 958 myeloma patients from the CoMMpass cohort40. Only 13 somatic mutations were identified in the PPP1R15B gene locus, including 3 missense mutations (0.313%) and 10 synonymous mutations (1.04%, Supplementary Table 3). A partial overlap was observed between the distal SE of PPP1R15B and the gene body of MDM4, with chromatin loops connecting to the PPP1R15B and PIK3C2B loci (Fig. 4a, b). In contrast, H3K27ac peaks associated with the PPP1R15B SE exhibited lower signal intensities and less chromatin interactions in control cells, suggesting increased enhancer activity in the activation of the PPP1R15B gene in MM.

Fig. 4. PPP1R15B is a multiple myeloma-specific super-enhancer-associated gene.

a ChIP-seq around PPP1R15B gene and SE locus in patient-derived myeloma cells (MM1-10), and controls including three MBCs, one NPC sample and a Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line Daudi (top panel). SE broad peaks are marked by red lines. Enhancer-promoter linkages as determined by H3K27ac HiChIP are shown in patient-derived myeloma cells (n = 3) and NPCs from different donors (n = 2, bottom panel). b H3K27ac ChIP-seq signals at the PPP1R15B gene and SE locus in HMCLs (n = 9), with H3K27ac HiChIP interactions in HMCLs (n = 5) displayed below. c dCas9-KRAB sgRNA target sites at the constituent enhancers (E1-4) within the SE, as indicated by arrows. d, e RT-qPCR (d) and western blot analysis (e) of PPP1R15B expression in KMS28BM upon dCas9-KRAB-mediated repression of SE using sgRNAs targeting PPP1R15B promoter (P), individual SE constituents or in combination (E1-4). For RT-qPCR, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed (p values in WT vs NTC = 1.00; WT vs P = 6.40 × 10-12; WT vs E1 = 1.55 × 10-9; WT vs E2 = 2.08 × 10-7; WT vs E3 = 2.83 × 10-7; WT vs E4 = 1.18 × 10-10; WT vs E1-4 = 1.32 × 10-11; E3 vs E1-4 = 4.05 × 10-7). n = 3 biological replicates. β-actin was used as a loading control. All western blots are representative of 3 biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SD. NPC, normal plasma cell; MBC memory B cell, NTC non-targeting control. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We observed a significantly strong correlation between the H3K27ac ChIP-seq signals of the PPP1R15B SE and its transcript levels in HMCLs (Supplementary Fig. 4e, Supplementary Fig. 7b). Notably, NCI-H929, KMS28BM and MM.1 S cell lines exhibited relatively strong H3K27ac signals, and were therefore chosen for downstream studies. We utilized the dCas9-KRAB-based CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) system to investigate the influence of the SE on PPP1R15B transcription. sgRNAs were designed to selectively target the four constituent enhancers (E1-E4) within the SE (Fig. 4c). We used a sgRNA targeting the PPP1R15B promoter as a positive control, and a non-targeting control (NTC) sgRNA as a negative control. Epigenetic silencing of PPP1R15B led to a significant downregulation of PPP1R15B and eIF2α hyperphosphorylation (Fig. 4d, e, Supplementary Fig. 8a–f). The expression of MDM4 and PIK3C2B were also reduced upon suppression of PPP1R15B SE or promoter activity. Negative control genes LRRN2 and SLC26A9, which reside outside the high connected PPP1R15B enhancer-promoter hub, were not affected at the transcription levels (Supplementary Fig. 8g–i). Functional analysis revealed that CRISPRi perturbation of the PPP1R15B SE inhibited cell proliferation and induced apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. 8j, k). These results indicate the transcriptional dependency of PPP1R15B in MM driven by SE.

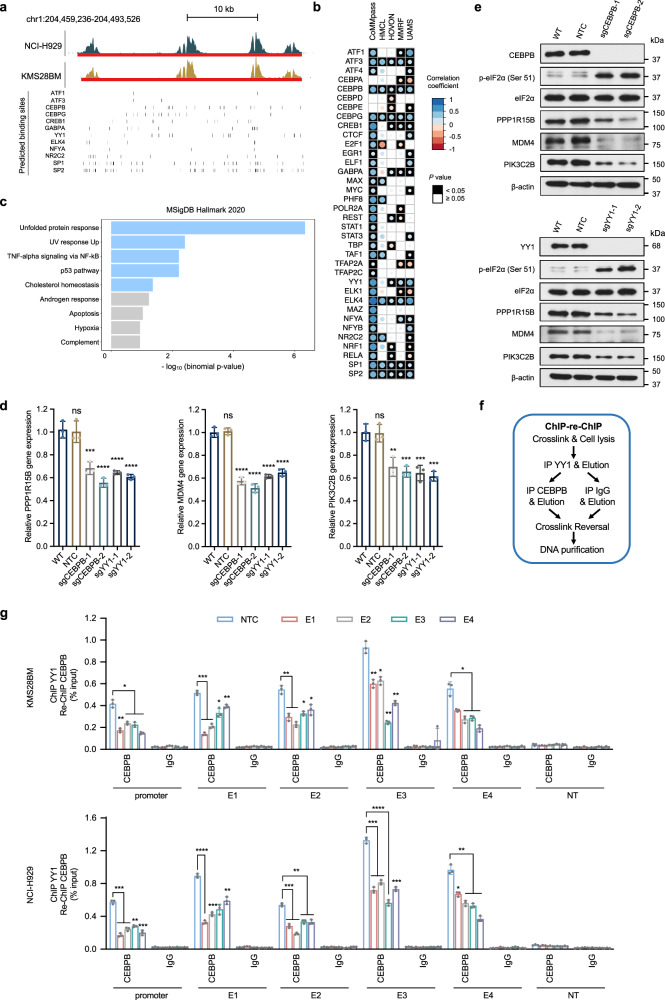

CEBPB and YY1 bind to and transactivate the super-enhancer of PPP1R15B

SEs have a higher transcription factor density and exhibit stronger interactions with the transcriptional apparatus in comparison to typical enhancers60,61. We identified putative transcription factor binding sites using FIMO62, and performed co-expression analysis of putative TFs and PPP1R15B using four microarray datasets59,63–65 and the CoMMpass RNA-seq dataset40 (Fig. 5a, b, Supplementary Fig. 9a). We thus narrowed down to a list of 12 TFs, including ATF1, ATF3, CEBPB, CEBPG, CREB1, GABPA, YY1, ELK4, NFYA, NR2C2, SP1 and SP2, whose expression positively correlated with PPP1R15B in ≥ 3 datasets with statistical significance (Spearman Rho > 0, p ≤ 0.05). We observed a generally stronger correlation between PPP1R15B and TFs in the CoMMpass dataset compared to other microarray datasets, likely attributable to its large sample size (Supplementary Table 1). Specifically, a strong correlation was observed between all 12 candidate TFs and PPP1R15B in the CoMMpass dataset (Spearman Rho > 0.4, p ≤ 0.05). Moreover, except for CREB1, NFYA and GABPA, nine out of these 12 TFs demonstrated a moderate to strong correlation with PPP1R15B in at least one microarray dataset (Spearman Rho > 0.3, p ≤ 0.05). Enrichr analysis revealed a significant overrepresentation of these TFs among components involved in the UPR signaling (Fig. 5c). On the other hand, we noted 11 TFs, potentially acting as repressors, exhibited a significant negative association with PPP1R15B in at least one transcriptomic dataset (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 9b). However, the strength of correlation generally appears weak or negligible (−0.2 <Spearman Rho <0). These results suggest the PPP1R15B SE domain is preferentially enriched with binding sites for TFs functioning as activators.

Fig. 5. CEBPB and YY1 regulate the transcription of PPP1R15B by binding to its promoter and super-enhancer.

a Genome browser views of the putative binding sites of prominent TFs predicted using FIMO and JASPAR motifs. Vertical bars correspond to the predicted binding sites for each TF. b Correlation patterns between TFs and PPP1R15B based on publicly available CoMMpass RNA-seq dataset40 and microarray datasets (HMCL65, HOVON63, MMRF64, UAMS59). Univariate analysis was performed using Spearman correlation analysis. Circle radius and color represent the correlation coefficient (Spearman Rho), and the color of the squares represents statistical significance (p value). c Functional enrichment analysis for a list of 12 TFs whose expression positively correlates with PPP1R15B level in ≥ 3 datasets with statistical significance (Spearman Rho > 0, p ≤ 0.05), showing enriched pathway terms curated from the MSigDB hallmark. P values were calculated using one-sided Fisher’s exact test and were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. d, e Cas9-expressing KMS28BM were transfected with NTC sgRNA or sgRNA targeting CEBPB or YY1. Effects of CEBPB or YY knockout on the mRNA (d) and protein (e) levels of PPP1R15B, MDM4, PIK3C2B in KMS28BM. For RT-qPCR, n = 3 biological replicates. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed (All p values in WT vs sgCEBPB/sgYY1 < 0.01. Detailed calculations of p values are provided in the Source Data file). All western blots are representative of 3 biological replicates. β-actin was used as a loading control. f, g ChIP-qPCR analysis of CEBPB and YY1 co-recruitment at PPP1R15B gene and SE loci using ChIP-re-ChIP (f). Epigenetic silencing of SE led to diminished co-recruitment of CEBPB and YY1 in KMS28BM and NCI-H929 cells (g). Significant differences were determined using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (All p values in NTC vs E1/E2/E3/E4/E1-4 < 0.05. Detailed calculations of p values are provided in the Source Data file). n = 3 biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SD. NT non-transcribed region. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To elucidate the association between TFs and the transcriptional activation of PPP1R15B, we knocked out candidate TFs and evaluated the subsequent regulatory effects on the expression of target genes. We hypothesized that enhancer inactivation resulting from loss of endogenous TFs bound to the PPP1R15B SE would downregulate its target genes, including PPP1R15B, MDM4, and PIK3C2B. Knockout efficiency was confirmed by western blot (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). Of the 12 TFs examined, the transcriptional levels of SE neighboring genes MDM4 and PIK3C2B was significantly downregulated upon depletion of 5 TFs (CEBPB, GABPA, YY1, SP1, SP2), whereas only 2 TFs CEBPB and YY1 transcriptionally regulated the expression of PPP1R15B (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 10c, d). As confirmed by western blot, depletion of CEBPB or YY1 remarkably reduced the protein levels of PPP1R15B SE-associated genes, accompanied by an increase in the phosphorylation of eIF2α, a downstream target of PPP1R15B (Fig. 5e).

We next sought to ask whether CEBPB and YY1 directly bind to the PPP1R15B promoter and distal SE. CEBPB loss reduced the recruitment of transcriptional coactivator p300 and RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II) to the PPP1R15B promoter and constituent enhancers (E1-E4) within the SE using ChIP-qPCR (Supplementary Fig. 11a, b). Similar effects of YY1 depletion on the enrichment of p300 and RNA Pol II were observed at the PPP1R15B promoter and SE region (Supplementary Fig. 11c).

Previous studies reported the direct interaction between YY1 and CEBPB that governs the transcriptional control of cell-type-specific activities66,67. In line with these findings, we found that YY1 binding to PPP1R15B promoter and SE loci was CEBPB-dependent as evidenced by decreased YY1 occupancy upon depletion of CEBPB (Supplementary Fig. 12). Conversely, knockdown of YY1 abrogated CEBPB recruitment to PPP1R15B promoter and SE. To further assess whether YY1 and CEBPB co-bound to the SE loci, we conducted ChIP-re-ChIP experiments in MM cells expressing dCas9-KRAB, along with either NTC sgRNA or sgRNAs targeting the constituent enhancers. Chromatin was sequentially immunoprecipitated using an antibody specific to YY1 followed by a second round of immunoprecipitation with anti-CEBPB antibody or IgG control (Fig. 5f). We observed a co-recruitment of YY1 and CEBPB at the PPP1R15B promoter and SE loci (Fig. 5g), whereas localization of dCas9-KRAB to the PPP1R15B SE disrupted the YY1-CEBPB interactions. This is consistent with earlier studies that dCas9-KRAB disrupts TF binding to DNA due to a much lower dissociation rate68. Collectively, these findings indicate that the cooperative binding of CEBPB and YY1 promotes SE-mediated transcriptional activation of PPP1R15B.

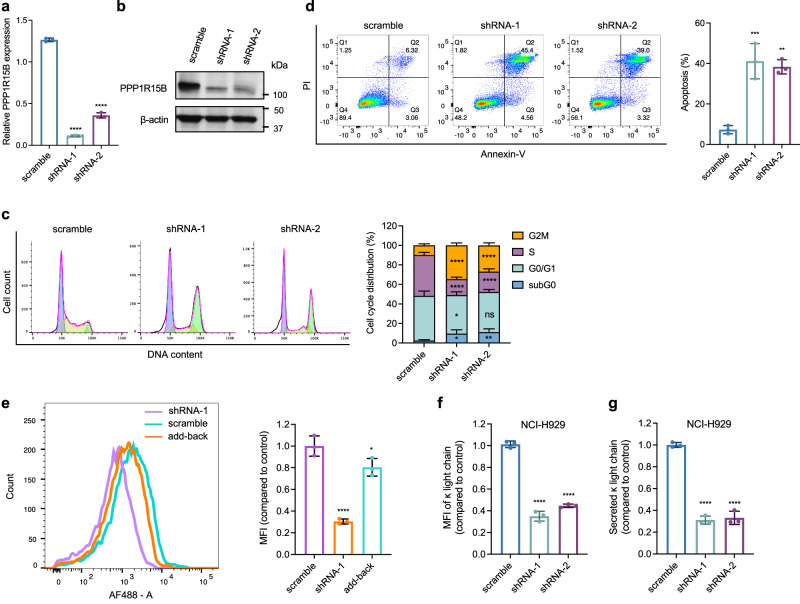

PPP1R15B promotes multiple myeloma cell proliferation and immunoglobulin production

We carried out loss-of-function and gain-of-function experiments to investigate the functional roles of PPP1R15B in MM. Knockdown of PPP1R15B significantly attenuated cell growth and proliferation in both 2D and 3D colony cultures (Fig. 6a, b, Supplementary Fig. 13, Supplementary Fig. 14a–d), phenocopying the effect of SE epigenetic silencing. Loss of PPP1R15B also suppressed the traverse of cycling cells through G2/M phase, accompanied by a decline in the proportion of S phase cells (Fig. 6c). PPP1R15B depletion triggered apoptosis, as evidenced by increased sub-G0/G1 hypodiploid population, annexin V/PI positive staining, upregulated proapoptotic genes (BAK, PUMA) and higher BAX/BCL-2 ratio (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Fig. 14e). The effects of genetic depletion of PPP1R15B were significantly rescued by reintroduction of PPP1R15B into knockdown cells (Supplementary Fig. 14c, d). Ectopic overexpression of wild-type PPP1R15B in U266 (with relatively low basal levels of PPP1R15B) promoted cell proliferation and colony growth (Supplementary Fig. 15a–e). These findings indicate an essential role of PPP1R15B in sustaining MM cell survival and proliferation.

Fig. 6. PPP1R15B promotes malignant phenotypes of multiple myeloma cells in vitro.

a, b Knockdown of PPP1R15B was confirmed by RT-qPCR (a) and western blot (b) in NCI-H929 transfected with scramble and PPP1R15B shRNAs. n = 3 biological replicates. For RT-qPCR, significant differences were determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (p values in scramble vs shRNA-1 = 8.23 × 10-11; scramble vs shRNA-2 = 5.22 × 10-9). All western blots are representative of 3 biological replicates. β-actin was used as a loading control. c Cell cycle analysis of NCI-H929 after transfection with the indicated shRNAs. Significant differences were determined using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (Detailed calculations of p values are provided in the Source Data file). Data were obtained from 3 independent experiments, with representative plots shown. d Apoptosis detection by Annexin-V/PI staining in NCI-H929 cells at day 4 post-transfection with scramble or PPP1R15B shRNAs. Bar chart showing the percentage of apoptotic cells (Annexin V + , right). n = 3 biological replicates. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed (p values in scramble vs shRNA-1 = 0.00074; scramble vs shRNA-2 = 0.0012). e Protein synthesis analysis by flow cytometry in PPP1R15B knockdown or add-back NCI-H929 cells. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for HPG incorporation (AF488) was measured and normalized to scramble control, with representative plots shown. n = 3 biological replicates. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed (p values in scramble vs shRNA-1 = 5.65×10-5; scramble vs add-back = 0.037). f Flow cytometric analysis of cytoplasmic immunoglobulin κ light chain expression upon PPP1R15B knockdown. n = 3 biological replicates. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed (p values in scramble vs shRNA-1 = 9.05 × 10-7; scramble vs shRNA-2 = 1.79 × 10-6). g Secretion of M protein measured by ELISA in PPP1R15B knockdown cells in NCI-H929. Results are shown as the relative MFI compared to the control. n = 3 biological replicates. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed (p values in scramble vs shRNA-1 = 2.70 × 10-6; scramble vs shRNA-2 = 3.23 × 10-6). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The translation initiation factor eIF2α, whose phosphorylation governs translational control, is a major substrate of the PPP1R15B-PP1c holophosphatase complex. To investigate whether PPP1R15B mediates MM cell survival by modulating basal eIF2α phosphorylation levels, we transduced knockdown cells with the loss-of-function PPP1R15B mutant (p.R658C) or wild-type PPP1R15B. The R658C mutation, located in the conserved PP1-binding domain, has been demonstrated to diminish PP1 binding and impair eIF2α dephosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 15f)52. While reported in a clinical case associated with a rare diabetes syndrome52, PPP1R15B R658C mutation was not detected in HMCLs or primary samples (Supplementary Table 3). We observed elevated levels of eIF2α phosphorylation in PPP1R15B-depleted MM cells, which can be reversed by reintroducing wild-type PPP1R15B (Supplementary Fig. 15g). The mutant add-back cells exhibited hyperphosphorylation of eIF2α similar to that in knockdown cells, but failed to negate the knockdown effects on cell survival and proliferation in KMS28BM and NCI-H929 (Supplementary Figs. 13, 14). These results suggest that eIF2α-directed phosphatase activity of PPP1R15B is a key factor underlying its oncogenic function in MM.

We therefore queried whether aberrant expression of PPP1R15B has an impact on translational efficiency in MM cells. Loss of PPP1R15B led to approximately 70% decrease in general protein synthesis (Fig. 6e). MM is characterized by overproduction of monoclonal immunoglobulin. We found that silencing of PPP1R15B diminished the intracellular abundance and secretion of immunoglobulin light chains (Fig. 6f, g, Supplementary Fig. 16a, b). These findings demonstrate MM cells are vulnerable to perturbation of PPP1R15B-dependent protein homeostasis. We further assessed the effect of genetic modulation of PPP1R15B on transcription of immunoglobulin light chain genes. Our data showed that the transcript levels of IGKC and IGLC were unaffected by PPP1R15B knockdown or add-back (Supplementary Fig. 16c, d), and exhibited a very weak and non-significant association with PPP1R15B gene expression in MM patients and HMCLs (Supplementary Fig. 17), indicating that PPP1R15B regulates immunoglobin production at the translational level through eIF2α dephosphorylation.

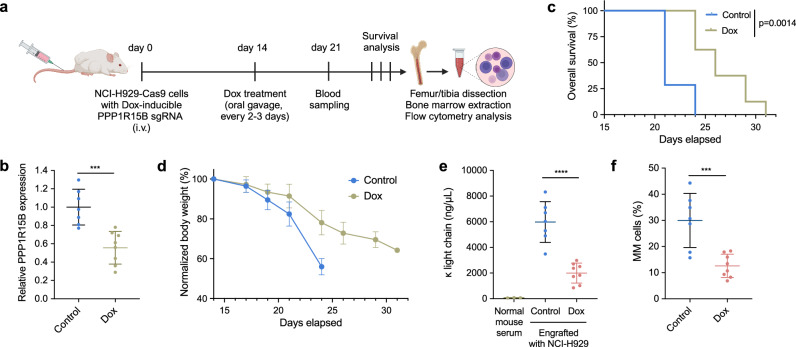

We next investigated the oncogenic potential of PPP1R15B in vivo using a disseminated xenograft model established by intravenous administration of NCI-H929 cells with stably expressed Cas9 and Dox-inducible PPP1R15B sgRNA into NSG mice. Mice were treated with Dox supplemented with 1% sucrose in water (n = 8) or a control buffer (1% sucrose in water, n = 7) through oral gavage three times a week, starting from day 14 post-injection (Fig. 7a). RT-qPCR analysis of isolated human myeloma cells from the mouse bone marrow samples confirmed the reduced expression of PPP1R15B upon in vivo induction of Dox (Fig. 7b). Mice were monitored daily for signs of myeloma development, including hind limb paralysis and distress, which served as the end-point of the experiments. In comparison with the control group, dox-induced PPP1R15B loss significantly prolonged the survival of mice, characterized by a delayed presentation of myeloma-related symptoms and less severe weight loss (Fig. 7c, d). Tumor burden was assessed by circulating levels of human M-protein in the mouse serum and the percentage of human myeloma cells (hCD138 + mCD45-) in the bone marrow. The level of human κ light chain in the sera of Dox-treated mice was approximately 3-fold lower than in the control mice at day 21 (Fig. 7e). Human κ light chain was not detectable in the sera of mice not injected with NCI-H929 cells by ELISA. Additionally, we observed a decreased level of bone marrow infiltration by MM cells (12.59% vs 29.96%, p = 0.00082) in mice receiving Dox compared to the control group (Fig. 7f), suggesting the crucial role of PPP1R15B in myeloma tumorigenesis.

Fig. 7. PPP1R15B promotes malignant phenotypes of multiple myeloma cells in vivo.

a Schematic representation of the mouse experiment timeline. NSG mice were injected with NCI-H929 cells with stably expressed Cas9 and Dox-inducible sgRNA through tail veins. Figure 7a created with BioRender.com released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license. b RT-qPCR analysis of PPP1R15B expression in hCD138 isolated MM cells from mouse bone marrow samples. n = 7 independent mice in the control group (1% sucrose in water), n = 8 independent mice in the Dox group. Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was performed (p value = 0.00049). c Kaplan-Meier plot of overall survival durations of tumor-bearing mice treated with Dox (n = 8) or control (1% sucrose in water, n = 7). Presence of hind limb paraplegia and distress is the experimental end-point. P value was determined using the log-rank test. d Body weights of tumor-bearing mice treated with Dox (n = 8) or control buffer (1% sucrose in water, n = 7). e Levels of human κ light chain in mouse serum as determined by ELISA on day 21. n = 3 independent mice not receiving tumor cells (negative controls), n = 7 independent tumor-bearing mice receiving control buffer (1% sucrose in water), and n = 8 independent tumor-bearing mice receiving Dox.` One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed (p values in normal mouse serum vs control = 5.09 × 10-6; control vs Dox = 1.80 × 10-5). f Percentages of hCD138 + mCD45- MM cells in the bone marrow of mice receiving Dox or control buffer (1% sucrose in water). Gating strategy is shown in Supplementary Fig. 20. n = 7 independent mice in the control group, n = 8 independent mice cells in the Dox group. Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was performed (p value = 0.00082). Data are presented as mean ± SD. i.v., intravenous. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

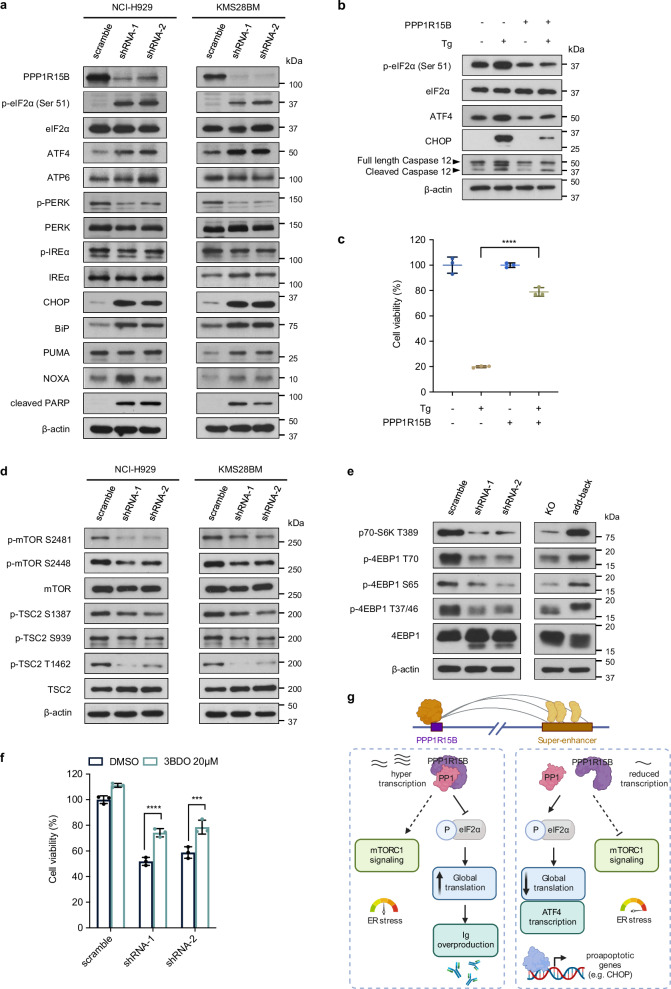

PPP1R15B regulates unfolded protein response and mTORC1 signaling

To explore the mechanistic roles of PPP1R15B in MM, we conducted RNA-seq analysis and profiled the transcriptome-level alterations resulting from the loss of PPP1R15B in KMS28BM (Supplementary Fig. 18a). Comparative analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs, |log2FC | > 1, FDR < 0.05) revealed 579 upregulated and 593 downregulated genes in PPP1R15B knockdown cells versus control cells. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)69 and GO analyzes revealed that downregulated genes were involved in cell proliferation, cell cycle, UPR and mTORC1 signaling (Supplementary Fig. 18b, d). Downregulated DEGs were notably enriched in KEGG pathways associated with translation (Supplementary Fig. 18c), which is consistent with our earlier findings that PPP1R15B regulates protein synthesis.

Immunoblot analysis showed that depletion of PPP1R15B triggered ER stress-induced apoptosis through upregulation of the eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP pathway without affecting other UPR branches (Fig. 8a). ER stress-associated pro-apoptotic proteins, such as CHOP, NOXA and PUMA, were upregulated in knockdown cells. Additionally, PPP1R15B knockdown remarkably induced the expression of ER chaperone GRP78/BiP, which is a transcriptional target of ATF4 and other arms of the UPR, such as activated p50-ATF6 and IRE1/XBP1s70–72. These effects were reversed by add-back of PPP1R15B (Supplementary Fig. 18e). Hence, our results highlight PPP1R15B as a key determinant that controls the switch between adaption and terminal UPR in MM cells.

Fig. 8. Depletion of PPP1R15B induces pro-apoptotic unfolded protein response and inhibits mTORC1 signaling.

a Western blot analysis in NCI-H929 and KMS28BM infected with scramble or shRNAs targeting PPP1R15B was performed using the indicated antibodies. All western blots are representative of 3 biological replicates. β-actin was used as a loading control. b Western blot analysis of UPR pathway components in U266 cell line that ectopically overexpressed PPP1R15B and WT U266 after treatment with 1 µM thapsigargin (Tg) for 12 hours. All western blots are representative of 3 biological replicates. c Cell viability analysis of U266 expressing empty (EV) or PPP1R15B overexpression plasmids (PPP1R15B) after Tg treatment. n = 3 biological replicates. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed (p values in WT + DMSO vs WT+Tg =2.03 × 10-8; WT+Tg vs OE+Tg = 2.14 × 10-7; OE + DMSO vs OE+Tg = 0.00054). Data are presented as mean ± SD. d, e The expression of mTORC1 signaling components were evaluated by western blot in PPP1R15B knockdown or add-back cells. All western blots are representative of 3 biological replicates. β-actin was used as a loading control. f Effect on cell viability of NCI-H929 cells infected with scramble or PPP1R15B-targeting shRNAs after treatment with the mTOR activator 3BDO (20 µM) for 48 hours. n = 3 biological replicates. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed (p values in scramble:DMSO vs 3BDO = 0.028; shRNA-1:DMSO vs 3BDO = 8.60 × 10-5; shRNA-2:DMSO vs 3BDO = 0.00028). Data are presented as mean ± SD. g Proposed model of the functional roles of PPP1R15B in MM. MM-specific PPP1R15B SE coordinates with master transcription factors, mediators and other cofactors, thereby leading to overexpression of PPP1R15B. PPP1R15B forms a holophosphatase complex with PP1c that dephosphorylates eIF2α under basal conditions, which elevates the threshold for activation of the lethal UPR pathway. On the other hand, hypophosphorylation of eIF2α allows for increased protein synthesis and immunoglobulin production. Depletion of PPP1R15B induces apoptosis in MM cells by activating eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP pathway and indirectly inhibiting mTORC1 pathway. Figure 8g created with BioRender.com released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To test whether PPP1R15B has a protective role against ER stress, we studied the effect of the ER stressor thapsigargin (Tg) on MM cells. Our results demonstrated that PPP1R15B overexpression attenuated the apoptotic effects elicited by Tg through suppression of eIF2α hyperphosphorylation (Fig. 8b, c).

ER stress was found to cross-talk with mTORC1 signaling in regulating various cellular processes, such as apoptosis, metabolism and translation73,74. Consistent with these findings, knockdown of PPP1R15B activated TSC2, an upstream negative regulator of mTORC1, and subsequently restricted mTORC1 activity by reduced phosphorylation on S2481 and S2448 residues (Fig. 8d). We also showed that downstream mTOR targets 4E-BP1 and S6K1 were hypophosphorylated in knockdown cells, whereas PPP1R15B add-back led to mTORC1 reactivation (Fig. 8e). Furthermore, mTOR activator 3BDO partially rescued PPP1R15B knockdown cells from apoptosis, suggesting that mTORC1 may act downstream of PPP1R15B (Fig. 8f). Collectively, these data suggest that SE-driven PPP1R15B protects MM cells by suppressing pro-apoptotic UPR components and indirectly activating pro-survival mTORC1 signaling.

Pharmacological inhibition of PPP1R15B exhibits anti-myeloma activity and synergizes with bortezomib

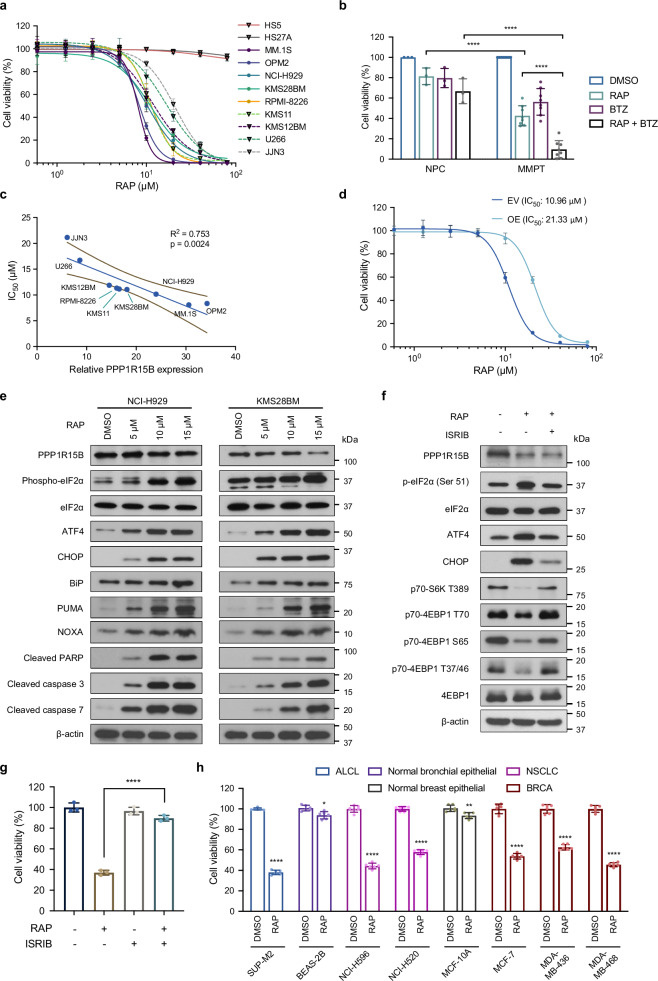

To investigate the therapeutic potential of targeting PPP1R15B, we examined the anti-myeloma effect of a selective inhibitor of PPP1R15B, Raphin1. Raphin1 treatment led to a dose-dependent cytotoxicity in HMCLs (n = 9) and patient-derived myeloma cells (n = 8), while sparing the stromal cell lines (HS5, HS27A) and bone marrow PCs from healthy donors up to 100 µM (Fig. 9a, b). We observed significant positive correlation between Raphin1 sensitivity and PPP1R15B (Fig. 9c). Notably, the IC50 values of Raphin1 in the majority of HMCLs range from 8.1 to 11.9 μM, except for JJN3 and U266 (IC50 > 15 μM), which agrees with the previous finding that 10 μM Raphin1 achieves near complete target engagement of PPP1R15B-PP1c75. Overexpression of PPP1R15B conferred resistance to Raphin1, suggesting the on-target effects of PPP1R15B inhibition (Fig. 9d).

Fig. 9. Therapeutic potential of targeting PPP1R15B using a selective phosphatase inhibitor Raphin1.

a Dose response for stromal cell lines (HS5, HS27A) and HMCLs (n = 9), treated with Raphin1 for 48 hours. n = 4 biological replicates. b Combination treatment with 10 μM Raphin1 and/or 2.5 nM bortezomib on NPCs (n = 3) and patient-derived myeloma cells (n = 8) for 48 hours. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed (p values in NPC:RAP vs MMPT:RAP = 7.51×10-6; NPC:RAP + BTZ vs MMPT:RAP + BTZ = 1.30×10-9; MMPT:RAP vs MMPT:RAP + BTZ = 4.18×10-7). c Correlation of PPP1R15B expression with drug response of Raphin1. Each dot represents a HMCL. Univariate linear regression analysis was performed, with coefficient of determination R2 and p value shown. Solid line represents the fitted linear regression curve, and dashed lines indicate 95% confidence band. d Cell viability of U266 overexpressing PPP1R15B or EV control after 48-hour Raphin1 treatment. n = 3 biological replicates. e Immunoblot analysis of UPR and apoptotic markers after 72-hour Raphin1 treatment. All western blots are representative of 3 biological replicates. β-actin was used as a loading control. f Immunoblot analysis of UPR and mTORC1 pathways in NCI-H929 treated with 10 μM Raphin1 and/or 100 nM ISRIB for 72 hours. All western blots are representative of 3 biological replicates. g Effects of Raphin1 (10 μM) and ISRIB (100 nM) on cell viability of NCI-H929 after 48 hours. n = 3 biological replicates. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed (p values in RAP vs DMSO = 4.95 × 10-8; RAP vs RAP + ISRIB = 2.47 × 10-7). h Cell viability of other cancer cell lines exhibiting relatively high PPP1R15B expression and the related normal cells (BEAS-2B, MCF-10A) after 48-hour treatment with 10 μM Raphin1 or DMSO. n = 6 biological replicates. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed (Detailed calculations of p values are provided in the Source Data file). Data presented as mean ± SD. RAP Raphin1, BTZ Bortezomib, ALCL Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, NSCLC Non-small cell lung cancer, BRCA Breast invasive carcinoma. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Pharmacological inhibition of PPP1R15B induced activation of the eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP pathway, accompanied by activation and cleavage of caspase-3, caspase-7 and PARP after 72 hours of Raphin1 treatment (Fig. 9e). We observed a pronounced elevation of terminal UPR components PUMA and NOXA with increasing concentrations of Raphin1, indicative of aggravated ER stress following Raphin1 treatment. Notably, Raphin1 mitigated mTOR-mediated phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1, which was abrogated by co-treatment with ISRIB, a PERK inhibitor that reversed eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. 9f). ISRIB counteracted the massive apoptosis inflicted by Raphin1 (Fig. 9g), demonstrating that the Raphin1-induced apoptosis is predominantly dependent on eIF2α hyperphosphorylation.

Early studies have reported that quiescent MM cells have the ability to evade bortezomib-induced apoptosis through suppression of eIF2α phosphorylation76,77. We found that PPP1R15B-depleted cells exhibited enhanced apoptosis after bortezomib treatment (Supplementary Fig. 19a). Moreover, Raphin1 re-sensitized bortezomib-resistant cells RPMI8226-P100V to bortezomib, and synergistically augmented bortezomib-induced apoptosis in MM cells (Supplementary Fig. 19b, c). These findings offer insights into the therapeutic potential of targeting PPP1R15B for the treatment of relapsed/refractory MM.

To assess the molecular vulnerability of PPP1R15B in other tumor types (Fig. 2a), we compared the anti-tumor effects of PPP1R15B depletion between non-malignant cell lines, BEAS-2B (bronchial epithelial) and MCF-10A (breast epithelial), and different cancer cell lines, including an anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) cell line SUP-M2, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines (NCI-H596, NCI-H520) and breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7, MDA-MB-436, MDA-MB-468). In contrast to normal controls, the examined ALCL, lung and breast cancer cell lines demonstrated susceptibility to PPP1R15B knockdown and consistent responsiveness to Raphin1 treatment (Fig. 9h, Supplementary Fig. 19d), potentially broadening the spectrum of malignancies amenable to pharmacological inhibition of PPP1R15B.

Discussion

SE has been implicated as a key driver of oncogenes and lineage-specific factors in solid tumors and hematologic malignancies21. In this study, we examined the enhancer connectomes in MM through integrative analysis of H3K27ac HiChIP and ChIP-seq. Our findings revealed the acquisition of SEs driving transcriptional dependency of genes that may be exploited as potential targetable vulnerabilities in MM. Our gene selection strategy of combining transcriptomic, survival and functional genomics data resulted in a catalog of MM SE-associated candidate genes (n = 9), including known oncogenes and genes previously uncharacterized in MM (Fig. 1e). These genes are broadly involved in various cellular and biological processes crucial for myeloma cell growth and survival, such as oxidative stress and ER stress responses, cell cycle regulation, RNA processing and translational control. Further investigation into the precise mechanisms of transcriptional activation by SEs and the functional relevance of these candidate genes in MM is warranted. In the present study, we highlighted and experimentally validated one of the candidate genes, PPP1R15B, as an oncogene transcriptionally driven by a highly recurrent SE gained in HMCLs and primary myeloma cells over normal controls.

Notably, structural variations at the PPP1R15B genomic locus and its SE domain were rarely detected in MM patients, which rules out the possibility of transcriptional activation by enhancer hijacking. In comparison to normal plasma cells, there were gains of the H3K27ac enhancer signal at the PPP1R15B SE domain but no formation of de novo enhancer peaks in MM patients and cell lines. These results indicate that aberrant activation of the PPP1R15B SE may be driven by master TFs and/or mediators. In support of this notion, Jin et al. reported that altered enhancer activity in MM is linked to dysregulation of TF genes mediated by SEs9.

We further demonstrated that TFs CEBPB and YY1 preferentially co-occupied PPP1R15B SE and regulated PPP1R15B transcription. Intriguingly, a previous study on SE-associated TF-based regulatory network identified CEBPB as a myeloma-specific TF driven by SE9. CEBPB is known to be crucial for myeloma cell growth and survival by regulating the expression of IRF-4, Blimp1, and PAX578. Therefore, it would be intriguing to explore the possibility that activation of CEBPB by SE could in turn foster the SE-associated transcriptional cascades, such as UPR pathways, for myeloma development. Additionally, YY1 has profound effects on MM cell proliferation, and its depletion has been shown to re-sensitize drug resistant cells to BTZ79. Our findings of YY1-bound transcriptional SE of PPP1R15B and increased cellular responsiveness to BTZ following PPP1R15B knockdown suggest that silencing of YY1 target gene PPP1R15B may reverse BTZ resistance in MM cells. Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that YY1 binds to active enhancers and promoters, and mediates enhancer-promoter interactions through dimerization, which is in line with our observation80.

Our results showed that altered expression level of PPP1R15B has a pronounced impact on the eIF2α phosphorylation status. The eIF2α is a master regulator of the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 integrated stress response that plays dichotomous roles in dampening global protein synthesis to accommodate ER stress while diverting UPR signaling towards apoptosis under the regimen of irremediable ER stress. During plasma cell differentiation, PERK-dependent UPR branch was silenced preceding increased immunoglobulin synthesis81; however, the IRE1 and ATF6 branches were both induced following lipopolysaccharide stimulation in murine B cells82. In concert with these findings, our study provided further evidence that MM cells suppress eIF2α-ATF4 signaling pathway through epigenetic upregulation of PPP1R15B to support cell survival and extensive immunoglobulin production (Fig. 8g).

Further mechanistic studies revealed regulatory pathways downstream of PPP1R15B in which eIF2α dephosphorylation promoted cross-talk signaling with mTORC1 pathways. Studies have shown interplay between mTORC1 activity and the UPR pathways under various cellular stresses. For instance, oxidative stress induces PERK/GCN2-dependent eIF2α phosphorylation, leading to diminished mTORC1 and elevated Akt activity83. Activation of mTORC1 coordinates with transcriptional regulation of UPR-affiliated genes, and promotes plasma cell differentiation and immunoglobulin secretion84. mTORC1 was also shown to promote eIF4F complex by inhibiting 4E-BPs while bolstering ternary complex recycling through eIF2β phosphorylation85. Given that eIF4F complex assembly and formation of ternary complex (eIF2-GTP-Met-tRNAi) are the two major rate-limiting steps of translation, the downstream effects of PPP1R15B on UPR and mTORC1 signaling may converge on translation control in MM cells.

Functional analyzes revealed that PPP1R15B knockdown induced apoptosis and impeded cell proliferation in HMCLs in vitro and in vivo. One caveat of the cell line-based xenograft model employed in this study is its potential limitation in comprehensively recapitulating the bone marrow milieu, as well as genetic diversity and intra-tumoral heterogeneity observed in MM patients. Nevertheless, our study provided a proof-of-concept validation of PPP1R15B as a potential therapeutic target in MM. Raphin1 is an inhibitor of PPP1R15B, with approximately 30-fold selectivity toward PPP1R15B-PP1c holophosphatase compared to PPP1R15A-PP1c75. We found that Raphin1 induced apoptosis in HMCLs and patient-derived myeloma cells harboring various genetic background and synergistically interacts with bortezomib. These findings, together with the fact that PPP1R15B is frequently overexpressed in MM cells regardless of their molecular subtypes, suggest that inhibition of the PP1-PPP1R15B/CReP complex and/or eIF2α dephosphorylation may open avenues for the development of anti-myeloma drugs. Furthermore, the survival dependency of PPP1R15B may extend to solid tumors, such as lung and breast carcinoma. Our findings align with the previous reports that eIF2α hyperphosphorylation potentiates the apoptotic effects induced by IFN-γ and estrogen in lung and breast cancer cells, respectively86,87. In addition, overexpression of PPP1R15B has been reported to confer survival advantage and resistance to tamoxifen in ERα-positive breast cancer88.

Overall, our study highlights the biological significance and clinical relevance of SE-driven PPP1R15B as a pivotal regulator of the UPR underlying MM progression. These findings suggest that PPP1R15B and/or eIF2α dephosphorylation warrants further investigation as potential therapeutic targets for treatment of MM and other solid tumors.

Methods

Ethics statement

All animal handling protocols and experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National University of Singapore (NUS IACUC, protocol number: R18-1254), and conducted in conformity with all relevant ethical regulations. All patients samples were obtained following informed consent for sample banking, analysis and publication according to the protocol approved by the institutional ethics review board for the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (NHG DSRB) in Singapore (reference number: 2017/00196). No participant compensation was provided.

Statistics and reproducibility

All quantitative data were obtained from at least 3 biologically independent experiments and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). All western blots are representative of 3 biological replicates. For each experiment, the number of replicates and the number of samples are provided in the figure legends. Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism (8.4.2) or R 4.2.1, except that Fig. 1b was analyzed by Enrichr89, and Fig. 1c was analyzed by the DAVID Bioinformatics Resource. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test. Prognostic factors were evaluated by two-sided multivariate and univariate analyzes of Cox proportional hazards regression model. Co-expression correlation was analyzed by Spearman’s correlation analysis. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using FlowJo software v9. Image J/FIJI (version 2.0.0-rc-69/1.52i) was used for quantification of western blots and immunofluorescence intensity. Figure 1e, Fig. 7a, Fig. 8g, and Supplementary Fig. 10c were created with BioRender.com. No statistical method was used to predetermine the sample size. No data were excluded from the analyzes. Statistically significant differences between groups were determined using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test, one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests as indicated (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). P values < 0.05 are considered statistically significant. Mice were randomly divided into groups following tumor cell engraftment. The investigators were blinded to allocation during immunofluorescence staining and imaging. In all other experiments performed in this study, the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Cell culture and reagents

Multiple myeloma cell lines [NCI-H929 (ATCC #CRL-3580), U266 (ATCC #TIB-196), MM.1 S (ATCC #CRL − 2974), RPMI-8226 (ATCC #CCL-155)], Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines [Daudi (ATCC #CCL-213), Raji (ATCC #CCL-86)], stromal cell lines [HS-5 (ATCC #CRL-3611), HS-27A (ATCC #CRL-2496)], breast cancer cell lines [MDA-MB-436 (ATCC #HTB-130), MDA-MB-468 (ATCC #HTB-132), MCF-7 (ATCC #HTB-22)], non-small cell lung cancer cell lines [NCI-H596 (ATCC #HTB-178), NCI-H520 (ATCC #HTB-182)], non-cancerous human brachial epithelial cell BEAS-2B (ATCC #CRL-3588), non-cancerous breast epithelial cell MCF-10A (ATCC #CRL-10317) and human embryonic kidney 293 T (HEK293T, ATCC #CRL-3216) were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). KMS12BM was obtained from DSMZ (#ACC 551). KMS11 (#JCRB1179) and KMS28BM (#JCRB1192) were obtained from JCRB Cell Bank. The anaplastic large-cell lymphoma cell line SUP-M2 was purchased from Creative Bioarray (#CSC-C0518). NCI-H929, KMS28BM, KMS11, U266, MM.1 S, KMS12BM, Daudi, Raji, HS-5, HS-27A, NCI-H596, MCF-7 and SUP-M2 were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (#SH30027.01, Hyclone, Irvine, CA, USA). MDA-MB-436, MDA-MB-468, and HEK293T were cultured as monolayers and maintained in DMEM (L0104-500, Biowest, France) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The culture medium was supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, #26140079) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, #15140122). In addition, MCF-10A cells were cultured in mammary epithelial growth medium (MEGM) supplemented with 100 ng/mL cholera toxin from Lonza (#CC-3150, Walkersville, MD, USA). NCI-H596 and NCI-H520 were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mM glutamine (Gibco, #25030081).

Cell lines were periodically tested to confirm the absence of mycoplasma contamination using MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, #LT07-710), and were recently authenticated by STR analysis (Centre for Translational Research and Diagnostics, National University of Singapore).

DMSO (D2650) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). THZ1 (HY-80013), thapsigargin (HY-13433), 3BDO (HY-U00434), bortezomib (HY-10227) and Raphin1 (HY-123960) were obtained from MedChem Express (NJ, USA).

Myeloma patient and normal donor samples

Human bone marrow aspirates from myeloma patients were obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki following written informed consent and approved by the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board in Singapore (NHG DSRB reference number: 2017/00196). All patients provided written informed consent to publish patient information, including diagnosis, sex/gender, age at diagnosis and race. Bone marrow mononuclear cells from healthy donors were obtained from Lonza. For the 19 myeloma patients (MM11-29) and three MGUS patients (MGUS1-3) included in this study, bone marrow samples from patients were subjected to red cell lysis followed by CD138 immunomagnetic selection with an AutoMACS separator (Miltenyi Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Normal plasma cells from healthy donors were enriched by positive selection of CD138+ cells using AutoMACS. Characteristics of myeloma patients and healthy donors were outlined in Supplementary Data 1.

Sex of all human research participants were assigned based on self-reporting at enrollment and confirmed with genomic analysis. All available donor samples were included irrespective of sex because the gene of interest is located on the autosome.

Mouse xenograft model

All animal experiments were carried out according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National University of Singapore and guidelines on the care and use of animals for scientific purpose. Fifteen female NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice aged 4-6 weeks were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (strain code #005557) via InVivos (Singapore). Female recipient mice were chosen for improved efficiency of tumor cell engraftment90. Sex or gender-based analysis is not relevant for the study.

The animals were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions at 22-24 °C, 50-70% relative humidity, a 12-hour light-to-dark cycle and ad libitum access to food and water. Mice were conditioned with sublethal irradiation one day prior to transplantation, and tumor inoculation was performed by different routes through intravenous administration. For Dox-inducible PPP1R15B knockout experiments, 10 × 106 NCI-H929 cells were injected into each mouse via tail vein. Mice were randomized to treatment or control groups based on body weights. Tumor cells were allowed for engraftment in the bone marrow for 2 weeks. Eight mice were treated with 10 mg/ml Dox supplemented with 1% sucrose in water, and seven mice were treated with control buffer (1% sucrose). Treatments were administered every 2-3 days by oral gavage from day 14 post-transplantation. Blood samples were collected from individual mice at day 21 post-transplantation. All mice were monitored daily, and euthanized within 24 hours when they reached a body condition score (BSC) less than 2, or developed disease symptoms such as impaired movement, hind limb paralysis, labored breathing and distress. Animals showing severe clinical symptoms were euthanized immediately. Bone marrow was harvested from femur and tibia, and used for phenotypic analysis after red blood cell lysis. Mice were euthanized by carbon dioxide (CO2) inhalation followed by cervical dislocation. In all animal experiments performed in this study, the mouse tumor burden has never exceeded the maximum limits permitted by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National University of Singapore.

Candidate gene selection based on gene expression profiling

To prioritize candidate genes associated with MM SEs, we performed differential gene expression analysis to identify genes overexpressed in MM patients in three different publicly available datasets, including the Blueprint RNA-seq dataset35 and two independent microarray datasets (MAYO39, GSE3975438). Detailed information for these datasets is summarized in Supplementary Table 1. We used DESeq2 for differential expression analysis of the RNA-seq dataset. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) are defined as genes with |log2FC | > 1 and FDR < 0.05. For GSE39754, raw data (CEL files) were retrieved from the GEO repository and processed using Affy R package91 for quality control, RMA normalization and calculation of expression values. Probes were converted based on the platform annotation. The MAYO microarray dataset (GSE6477) is known to be pre-processed by the MAS5 algorithm92, and was thus utilized to assess gene expression changes without any additional modification. For both microarray datasets, the limma R package93 was used for differential gene expression analysis using the cutoff criteria of |log2FC | > 1 and Benjamini-Hochberg-corrected p < 0.05.

We identified a small subset of 46 MM SE-associated genes consistently upregulated in MM compared to premalignant stages or healthy controls across all three transcriptomic datasets. However, the microarray platforms probed only a limited portion of genes, with different number of genes represented by distinct probe sets in the HuEx-1_0-st (GSE39754) and HG-U133 A (MAYO) platforms. Despite missing probe sets in some microarray datasets, DEGs present only in the Blueprint dataset or concordantly overexpressed in one of the microarray datasets were retained for further analyzes and gene selection. Specifically, 58 SE-associated genes were significantly overexpressed in MM in the Blueprint dataset but were not probed in either of the above-mentioned microarray datasets. Among the upregulated DEGs associated in the Blueprint dataset, we identified a list of 87 genes concordantly upregulated in MM in the GSE39754 dataset but not detected by the HG-U133 A (MAYO) platform, and 16 genes overlapping with the upregulated DEGs in the MAYO dataset but not detected by the HuEx-1_0-st (GSE39754) platform. We thus obtained a total of 207 MM SE-associated genes significantly overexpressed in MM.

Plasmid construction and lentiviral production

Two short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs, pLV[shRNA]-Puro-U6 > hPPP1R15B [shRNA]) against PPP1R15B were purchased from VectorBuilder (Chicago, IL, USA). For ectopic overexpression of PPP1R15B, expression plasmid including full-length human PPP1R15B (pLV[Exp]-Neo-CMV>hPPP1R15B[NM_032833.5]) and its mutant variant (c.1972C>T; p.R658C) was obtained from VectorBuilder. The plasmid constructs were validated by sequencing. Lentivirus was generated by co-transfecting lentiviral plasmids with packaging vectors (pMDLg/pRRE, pRSV-Rev, and pMD2.G) into HEK293T cells via X-tremeGENE HP DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche) and harvested 48 hours post-transfection. Cells were infected with filtered lentivirus in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) and selected with the respective antibiotics for 5 passages. Control cells were transduced with scramble control or empty vector. The shRNA sequences are listed in Supplementary Data 4.

RNA extraction, reverse transcription and quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and reversely transcribed into cDNA using iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). RT-qPCR was performed using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on a QuantStudio 5 real-time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The relative expressions of genes were calculated based on the 2−△△CT method and normalized by GAPDH level. Primers used in this study were listed in Supplementary Data 4.

Cell proliferation and cell cycle assays

Cell proliferation was assessed using BrdU labeling kit (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) according to manufacturer’s instruction. Cells were synchronized by incubating in serum-free medium for 24 hours. Cells were allowed to recover for 1 hour and then labeled with BrdU (10 µM) for 1 hour. Cells were fixed and permeabilized followed by staining with APC-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody. BrdU incorporation was detected using a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and the data was analyzed using FlowJo software (v9, FlowJo, LLC).

For colony formation assay, 2000 cells were resuspended in 1 ml of the semisolid methylcellulose-based media (MethoCult H4034; Stem Cell Technologies, Canada) and cultured in 35 mm dishes at 37 °C in a fully humidified atmosphere at 5% CO2. After 3 weeks of culture, colonies were imaged using Olympus SZX12. Each condition was repeated twice in triplicates.

For cell cycle analysis, samples were collected and fixed with 70% ethanol overnight at 4 °C. Cells were washed in PBS supplemented with 2% BSA and then incubated with PI/RNase Staining Buffer (BD biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. Cell cycle distribution was analyzed using LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Cell viability and apoptosis assays

Cell viability assay was performed using CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Briefly, cells were plated into opaque-bottom 96-well plates at a density of 3 × 104 in 100 µL of culture medium per well after transfection or drug treatment. Each experiment was performed in quintuplicate. Luminescence signal was measured using Infinite M200 Microplate reader (Tecan) at the indicated timepoints. To detect apoptosis, cells were washed twice in cold PBS and resuspended in Annexin V binding buffer (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA), following which they were stained with Annexin V-APC (10 µg/mL) and propidium iodide (PI, 40 µg/mL). Flow cytometry analysis was performed using LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

CRISPR-dCas9-KRAB-mediated suppression of super-enhancer

The dCas9-KRAB-T2A-mCherry plasmid was constructed by replacing the GFP expression cassette of dCas9-KRAB-T2A-GFP lentiviral vector (Addgene plasmid #71237) with mCherry sequence. The single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting the PPP1R15B promoter or enhancer loci were designed using the online design tool Synthego (https://www.synthego.com/) and subsequently cloned into the BsmBI site of doxycycline-inducible gRNA vector FgH1tUTG (Addgene plasmid # 70183). The sgRNA sequences including non-targeting control are listed in Supplementary Data 4. Myeloma cells were infected with dCas9-KRAB-T2A-mCherry lentivirus and the mCherry positive cells were sorted using FACSAria Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences). The cells that stably express dCas9-KRAB were next transduced with sgRNA-expressing constructs and were FACS sorted for double-positive cells (GFP + ;mCherry + ). Doxycycline (Dox, 1 µg/ml) was added following infection and the gene silencing effect was assessed by PCR and western blot.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout

To generate Cas9-expressing stable cell lines, cells were infected with lentivirus containing FUCas9Cherry (Addgene plasmid #70182) and enriched by FACS sorting. Doxycycline-inducible gRNA plasmids (FgH1tUTG) targeting the transcription factor of interest were introduced into cells stably expressing Cas9. Gene disruption was further confirmed by PCR and western blot. The sgRNA sequences are provided in Supplementary Data 4.

Immunofluorescence staining

CD138+ plasma cells from bone marrow aspirates of healthy donors and myeloma patients were cytospinned at 1200 rpm for 5 min onto glass slides, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and immunostained as follows. Cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton-X in PBS/Tween-20 (0.01%) (PBST) for 10 min. After a brief wash in PBST, the slides were blocked with 1% BSA in PBST for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by incubation with primary antibodies (1:200 for anti-CReP and anti-GADD34, 1:300 for anti-CD138) overnight at 4 °C. Cells were washed for 3 times in PBST and incubated with secondary antibodies at a dilution of 1:1000 for 1 hour in the dark at room temperature. For ER staining, cells were stained with ER cytopainter-red fluorescence (Abcam, ab139482) for 10 min at 37 °C according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Coverslips were mounted using mounting medium with DAPI (Vectashield, H-1200). Slides were imaged using LSM710 (Zeiss, Germany) confocal microscope. The anti-CReP antibody were validated by shRNA-mediated knockdown and add-back experiments. No primary antibody controls were also included in each experiment. Details of primary and secondary antibodies are listed in Supplementary Data 4.

Protein synthesis assay

Nascent protein synthesis was analyzed using the Click-iT homopropargylglycine protein synthesis assay kit (C10428) from Invitrogen according to manufacturer’s instructions. The incorporated amino acids were detected by Alexa Fluor 488 and then cell nuclei were labeled with the NuclearMaskTM blue stain. The samples were analyzed using a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and the median fluorescence intensity of each sample was analyzed using FlowJo software (v9, FlowJo, LLC).

Quantification of secreted and intracellular immunoglobulin light chain