Abstract

Background

The pervasiveness of the Internet in everyday life, especially among young people, has raised concerns about its effects on mental health, education, and, recently, oral health. Previous research has suggested a complex relationship between Problematic Internet Use (PIU), lifestyles, and oral health-related quality of life, highlighting the need to examine these interactions further. This study seeks to explore the PIU as a predictor of oral health-related quality of life and examine the mediating role of lifestyles between both in a sample of Peruvian schoolchildren.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was carried out with 293 Peruvian students aged 12 to 17 years (M = 14.42, SD = 1.5), using structural equations to analyze the relationship between PIU, lifestyles, and quality of life related to oral health. The data collection procedure was through a face-to-face survey. Validated instruments measured PIU, lifestyles, and oral health-related quality of life. The study’s theoretical model was analyzed through structural equation modeling with the MLR estimator. The fit assessment was performed using the comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR).

Results

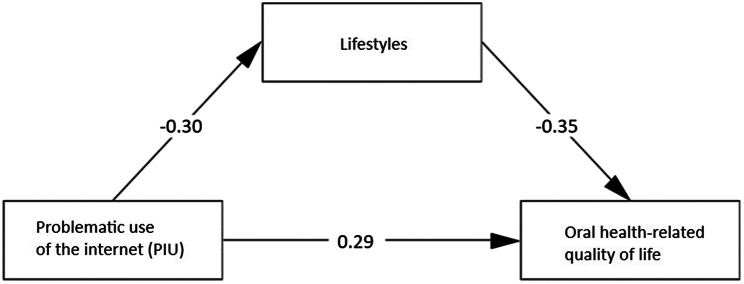

They indicated significant correlations between PIU, lifestyles, and oral health-related quality of life. A negative influence of PIU on lifestyles (β = -0.30, p < .001) and on oral health-related quality of life (β = -0.35, p < .001) was observed, as well as a positive relationship between PIU and oral health-related quality of life (β = 0.29, p < .001). The mediation of lifestyles was statistically significant, suggesting that they mediate the relationship between PIU and oral health-related quality of life.

Conclusions

The study confirms that PIU can negatively affect adolescents’ oral health-related quality of life, mediated by unhealthy lifestyles. It underlines the importance of promoting balanced Internet use and healthy lifestyles among young people to improve their oral well-being.

Keywords: Oral health, Lifestyles, Internet use, School age population, Quality of life

Introduction

In the current technological revolution, the Internet has permeated all aspects of daily life, redefining social, educational, and health dynamics. This phenomenon is particularly notable among young people, especially Generation Z, who have grown up in a digital environment. The integration of the Internet into the daily lives of adolescents has been the subject of numerous studies, which have explored both its benefits and its possible negative repercussions on various aspects of life, including mental and physical health [1, 2]. Internet penetration has significantly transformed educational practices, replacing traditional physical classroom structures with distance learning modalities, thus democratizing access to education [3]. However, this transformation is challenging, especially when teaching practical skills and direct interaction between students and educators. Furthermore, the prevalence of the Internet has led to a change in learning methods, with a more practical and game-based approach, which is especially relevant for digital native generations [4]. In parallel, heavy Internet use and lack of consumer socialization skills make adolescents vulnerable to online privacy risks, such as profiling, identity fraud, and sexual exploitation [5]. Furthermore, pressure on body image, exacerbated by social media, significantly affects adolescents, with a notable impact on their mental well-being. The school, as a key space for access to information and communication technologies, especially for those from homes with fewer resources, emerges as a fundamental environment for studying this dynamic [6].

Likewise, the increasing prevalence of problematic Internet use (PIU) and its impact on oral health constitute an emerging area of medical and psychological research interest. PIU is defined as the uncontrollable and potentially harmful use of the Internet and has been identified as an emerging public health problem, mainly affecting adolescents, a particularly vulnerable group [1, 2, 4, 7]. This problem manifests itself in two primary forms: generalized internet addiction (IA), which encompasses multidimensional excessive use of the Internet and smartphones, and specific AI, focused on particular activities such as social networks, games, or betting [8]. AI affects emotional well-being and academic performance and is associated with unhealthy lifestyle habits and oral health problems. Recent studies have revealed that adolescents with problematic Internet use have poor oral hygiene, irregular eating patterns, and reduced sleep quality, all of which contribute to oral health problems [9]. Additionally, AI in young adults is linked to mental and psychological symptoms, as well as negative health habits such as smoking and low frequency of tooth brushing [10]. Interestingly, the prevalence and consequences of AI vary by academic year, gender, and marital status, with younger and unmarried students showing higher rates of AI and poorer oral health-related quality of life [9]. Likewise, in a study focused on children aged 12 to 15 years, a significant relationship was found between the use of the Internet to search for information about oral health and a higher prevalence of dental caries, suggesting less healthy behaviors related to the Internet [7]. AI is also linked to risk behaviors in adolescence, such as substance use and inappropriate diets, which can persist into adulthood and negatively affect oral health [11, 12]. In this sense, PIU has been linked to a range of disorders and pathologies, including obsessive-compulsive disorder, alcohol abuse, sleep disorders, ADHD, eating disorders, overweight and obesity, as well as personality problems, distress tolerance, depression, stress, anxiety, and physical problems such as dry eye [3, 8].

PIU, as documented in recent studies, is associated with several adverse effects on the physical and mental health of adolescents. Adolescents with PIU have a high prevalence of subjective health complaints, especially of a psychological nature, such as irritability, depression, and nervousness [13, 14]. These health problems are exacerbated by sedentary lifestyles, characterized by insufficient physical activity and unhealthy eating habits, which often accompany excessive Internet use. Additionally, PIU has been linked to a decrease in perceived quality of life and the development of co-occurring psychiatric disorders [14, 15]. Although most people can benefit from using the Internet, for a significant minority, especially among teenagers and young adults, it can become dysfunctional. This demographic is particularly vulnerable due to the emotional and social stress characteristic of this stage of life, as well as changes in brain development. The proliferation of high-performance smartphones has facilitated unprecedented access to the Internet, contributing to the rise of PIU and its associated effects [16, 17]. It is crucial to recognize that PIU is not an isolated phenomenon but is intrinsically related to multiple lifestyle and psychosocial factors. The relationship between PIU and variables such as sleep, exercise, perceived stress, and leisure habits requires further exploration to develop effective intervention strategies. Although “Internet gaming disorder” has been included in the DSM-5 for further study, the definition and diagnostic criteria of PIU still require clarification and consensus in the scientific community [14].

Some studies have concluded that some lifestyles, such as sleep, can mediate the relationship between PIU and oral health-related quality of life, as proposed by Do KY et al., in a sizable Korean population where PIU directly affected sleep and indirectly affected oral health-related quality of life, confirming direct and indirect causal relationships between the three factors [18]. Furthermore, another study found a statistically positive mediation of eight different lifestyle behaviors associated with oral hygiene habits-related quality of life, sleep time, and consumption of sugary foods between PIU and dental caries in Japanese adolescent students [11].

Taking into account the arguments adduced, the following hypotheses are proposed (See Fig. 1):

Fig. 1.

Theoretical model

H1:

There is a negative relationship between problematic Internet use and lifestyles.

H2:

There is a negative relationship between lifestyles and oral health-related quality of life.

H3:

There is a negative relationship between problematic Internet use and oral health-related quality of life.

H4:

Lifestyles mediate the relationship between problematic Internet use and oral health-related quality of life.

Methods

Design and participants

A non-experimental study with cross-sectional and explanatory design was carried out in which latent variables represented through a system of structural equations (SEM) were considered [19]. The students were recruited from two state schools in the Arequipa department. They live in the surrounding areas, which are rural and urban areas in expansion. In some sectors, there still needs to be more drinking water and drainage. For this reason, the participants are considered to belong to sectors D and E (categorized as low socioeconomic level). To determine the appropriate sample size, the Soper electronic calculator was used, which takes into account the number of observed and latent variables in the SEM model, an anticipated effect size of 0.2, a desired statistical significance level of 0.05, and a statistical power level of 0.90. This analysis resulted in the need to have a minimum of 119 participants. The selection criteria were: Students of both sexes, aged between 12 and 17 years, enrolled in schools and studying between the 1st and 5th year of secondary school. In addition, they had to voluntarily agree to participate and sign the informed assent and even have the informed consent of their parents. The sample was selected through a non-probabilistic method, resulting in the participation of 293 Peruvian students between the ages of 12 and 17 (M = 14.42, SD = 1.5). Regarding gender distribution, 54.9% (161 students) were female and 45.1% (132 students) were male. Regarding the distribution by school grade, the following distribution was observed: 10.6% (31 students) in fourth grade, 21.8% (64 students) in first grade, 27.3% (80 students) in fifth grade, 25.6% (75 students) in second grade and 14.7% (43 students) in third grade.

Procedure

The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of a Peruvian University, and the directors of two educational institutions were contacted through a written request. Subsequently, the professors responsible for each section were given a detailed explanation of the project at each institution and obtained the signed informed consent from all parents or legal representatives/guardians of all students. The data collection procedure was through a face-to-face survey. After obtaining informed consent, a hard copy of the questionnaire was given to them. During the administration of each survey, the general parameters were clarified, and a period of 5 to 10 min was granted for completion, during which individual doubts were resolved. Upon completion, students voluntarily returned the completed questionnaires. All these actions were carried out following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, guaranteeing ethics and transparency in research with human beings.

Instruments

Problematic Internet Use. The PIUS-a Adolescent Problematic Internet Use Scale was used, and the scale was designed to detect problematic Internet use early. The unidimensional scale comprises 11 items, with 5 categories from 0 (Totally disagree) to 4 (Totally agree). Likewise, it presents an adequate (α = 0.82) [20]. In the present study, a 5-item model was carried out considering the permanence of items 3, 5, 7, 9, and 10. This questionnaire comprised of questions which included: On some occasions I have neglected some tasks or performed less, in exams, sports, etc. because I connected to the Internet; Sometimes I get irritated or in a bad mood about not being able to connect to the Internet or having to disconnect; I have stopped going to places or doing things that previously interested me in order to connect to the Internet; It annoys me to spend hours without connecting to the Internet; When I can’t connect I can’t stop thinking if I’m missing something important, respectively. The adjustment of the unidimensional model presented adequate reliability indices (α = 0.72) and validity based on the internal structure (χ2 = 0.620, df = 2, p < .01, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00 (90% CI 0.00–0.07), SRMR = 0.01).

Lifestyles. The FANTASTICO instrument is a support tool for health promotion and disease prevention professionals. It allows for the identification and measurement of lifestyles in a population. It is composed of 10 dimensions and 30 questions. The 10 dimensions areF: family and friends, A: associativity and physical activity, N: nutrition, T: toxicity, A: alcohol, S: sleep and stress, T: personality type and activities, I: inner image, C: health control and sexuality and, O: order. Each question presents three response options on a Likert-type scale, rated from 0 to 120 points. A higher score in the dimension is more favorable towards health. It was validated using the Delphi method, obtaining a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.797 [21]. In the present study, the unidimensional model presented adequate validity indices based on the internal structure (χ2 = 66.160, df = 43, p < .01, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.04 (90% CI 0.02–0.06 ), SRMR = 0.04).

Quality of life-related to Oral health. The Child Perception Questionnaire CPQ was used [22]. The CPQ scale consists of 8 items, is structured in four first-order domains, and is administered to evaluate the quality of life related to oral health in adolescents. The dimensions are: oral symptoms, functional limitation, emotional well-being and social well-being. The scale has proven to have high internal consistency, with values greater than 0.8, thus ensuring the results’ reliability. In the present study, this questionnaire presented adequate reliability indices (α = 0.70) and validity based on the internal structure (χ2 = 33.830, df = 20, p < .01, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.05 (90% CI 0.02–0.07), SRMR = 0.04.

Statistical analysis

The study’s theoretical model was analyzed through structural equation modeling with the MLR estimator, which is appropriate for numerical variables and robust to deviations from inferential normality. The fit assessment was performed using the comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). CFI and TLI values > 0.90 were used, RMSEA < 0.080, and SRMR < 0.080. The software “R” version 4.1.2, and the “lavaan” library in its 06–10 version were used.

Results

Preliminary analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1, and correlations indicate significant relationships between the variables. Problematic Internet use is positively correlated with oral health-related quality of life (r = .31, p < .01) and negatively with lifestyles (r = − .23, p < .01). Oral health-related quality of life is also negatively correlated with lifestyles (r = − .34, p < .01). Regarding internal consistency measured using Cronbach’s Alpha, all variables show an acceptable value, with “Lifestyles” having the highest value (α = 0.76) and “Oral health-related quality of life” having the lowest (α = 0.7). “Problematic Internet use” has an α of 0.72.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, internal consistencies, and correlations for the study variables

| Variable | M | SD | A | α | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problematic Internet Use | 8.98 | 3.35 | 0.44 | 0.72 | - | ||

| Oral Health-related quality of life | 7.49 | 4.72 | 0.94 | 0.70 | 0.31** | - | |

| Lifestyles | 14.02 | 3.48 | -0.11 | 0.76 | − 0.23** | − 0.34** | - |

Note: M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation, A = Asymmetry, α = Cronbach’s Alpha, ** indicates p < .01

Analysis of the theoretical model

In the analysis of the theoretical model, an adequate fit was achieved, evidenced by the following indicators: χ2 = 307.180, df = 226, p = .000, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.04 (with a confidence interval of 90% between 0.02 and 0.04) and SRMR = 0.05. A significant negative influence was observed between problematic Internet use and lifestyles (H1: β = -0.30, p < .001), as well as between lifestyles and oral health-related quality of life (H2: β = -0.35, p < .001). On the other hand, a significant positive relationship was identified between problematic Internet use and oral health-related quality of life (H3: β = 0.29, p < .001) (See Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Results of the explanatory structural model of job performance

Mediation model

The bootstrapping technique was implemented with 5,000 iterations to conduct the mediation analysis (Table 2). Through this analysis, it was possible to corroborate the mediating role of lifestyles in the relationship between problematic Internet use and oral health-related quality of life. (H4: β = 0.05, p = < 0.05).

Table 2.

Research hypotheses on indirect effects and their estimates

| Hypothesis | Path in the model | β | p | IC 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||

| Hypothesis 4 | Problematic use → Lifestyles → Oral Health-related quality of life | 0.05 | < 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

Discussion

The current technological era has led to the Internet being deeply integrated into daily life, primarily affecting young people and Generation Z. This integration has transformed social, educational, and health dynamics, with studies that point out both benefits and negative impacts, including mental and physical health effects. In education, it has promoted distance learning, although with challenges in practical teaching and interaction. In addition, it has changed learning methods towards more interactive and playful approaches. Problematic Internet Use (PIU) has been identified as a public health problem related to poor lifestyle habits and oral health-related quality of life problems. Adolescents with PIU present health problems exacerbated by sedentary lifestyles. Internationally, an increase in PIU has been observed among students during the COVID-19 pandemic, linked to unhealthy lifestyles and poor oral health-related quality of life. A negative relationship is suggested between PIU, lifestyles, and oral health-related quality of life, with lifestyles mediating between PIU and oral health-related quality of life.

Hypothesis H1 was confirmed, establishing a negative relationship between problematic Internet use (PIU) and lifestyles, particularly in primary education adolescents. Studies have shown that adolescents have a high prevalence of PIU, with significant adverse effects on their health and well-being [13, 16]. Subjective health complaints, especially of a psychological nature, such as irritability, depression, and nervousness, are common in this group. These health problems are exacerbated by unhealthy lifestyles, such as physical inactivity, lack of sleep, and poor eating habits, which often accompany PIU [13]. Increased Internet access and smartphone ownership have led to a proliferation of online psychosocial problems, such as cyberbullying and Internet addiction. Furthermore, a correlation has been found between PIU and time spent on the Internet, suggesting an intrinsic relationship with lifestyle habits [14]. Furthermore, the literature suggests that PIU contributes to a decrease in participation in physical and social activities, thus reducing opportunities for the development of interpersonal skills and stress management in natural environments, which further aggravates their state of well-being [2, 4].

Hypothesis H2 was confirmed, suggesting an adverse correlation between lifestyles and oral health-related quality of life, indicating how everyday behaviors can negatively influence the dental well-being of adolescents. This relationship has been widely documented in different geographical and cultural contexts, highlighting the universality of this phenomenon. In Europe, studies have shown that excessive consumption of soft drinks among adolescents is linked to deterioration in oral health-related quality of life and is associated with unhealthy lifestyle practices [23]. This evidence highlights the importance of a balanced diet and the risk that sugary drinks pose to dental integrity. On the other hand, a significant relationship has been identified between overweight/obesity and a higher prevalence of cavities in young people, suggesting that body weight and oral health-related quality of life are intrinsically connected, probably through diets rich in sugars and carbohydrates that promote both, weight gain and tooth decay [24]. In Asia, particularly China, adolescent smokers were found not only to have higher soft drink consumption but also to have poorer oral hygiene practices and significantly reduced oral health related to quality of life [25]. This finding highlights how smoking, a well-known negative lifestyle, can have collateral effects on oral health-related quality of life. In Indonesia, negative lifestyle behaviors such as poor dietary practices, increased sedentary time, drug use, and psychological distress were found to be associated with infrequent tooth brushing [26]. This reinforces the notion that healthy lifestyle habits are essential for preventing dental problems, highlighting the need to promote healthy practices early on.

Confirmation of hypothesis H3 suggests a significant adverse correlation between problematic Internet use and oral health-related quality of life among Peruvian schoolchildren, expanding our understanding of the digital environment’s implications for young people’s physical health. Previous research has shown that excessive and uncontrolled use of the Internet and electronic devices can interfere with daily activities, mood swings, concern about Internet access, and difficulties in reducing online time [8]. Specifically, it has been observed that adolescents with problematic Internet use patterns present poor oral hygiene, which can be attributed to negligence in daily dental care practices [27]. This neglect may be related to a decrease in the priority assigned to oral health-related quality of life due to absorption in digital activities. Additionally, these young people tend to adopt unhealthy lifestyles, including irregular eating patterns, such as skipping meals or consuming unbalanced diets, and reducing sleep hours. These behaviors contribute significantly to the appearance of oral health-related quality of life problems, such as cavities, periodontal diseases, and less frequent tooth brushing. The connection between excessive Internet use and these negative health habits underscores the importance of addressing digital well-being as an integral component of public health and health education programs [28–31].

Hypothesis H4 suggests that lifestyle is a mediator between problematic Internet use (PIU) and oral health-related quality of life, a finding corroborated by recent evidence that expands our understanding of digital behavior and physical health. Our research findings highlight a significant mediation of lifestyles between Problematic Internet Use (PIU) and oral health-related quality of life, corroborating the evidence of previous studies [18]. A plausible explanation for this mediation lies in effective time management, observed in adolescents with healthy lifestyles. These young people tend to use the Internet more balanced, allowing them to allocate enough time to essential oral hygiene practices such as brushing and flossing. This pattern is evidenced by research showing a correlation between increased screen time and decreased oral health in adolescents [32]. Additionally, adolescents with a higher quality of life-related to oral health have been found to consume fewer harmful substances, such as tobacco and alcohol, which are consumed more frequently by young people with PIU [33, 34]. It is widely recognized that these substances harm oral health, including dental pigmentation, bad breath, and periodontal diseases [35]. On the other hand, proper time management, favored by healthy lifestyles, allows greater dedication to oral hygiene-related quality of life. Additional research suggests that efficient time management improves the quality of life of adolescents, allowing them to use the Internet more consciously and moderately [36, 37].

Although the interaction of these three variables requires further research to understand its nature and repercussions, the importance and need to promote healthy lifestyles and responsible use of screen time in a population as vulnerable as teenagers.

Implications

The findings of this study reveal significant implications for professional practice, public policy formulation, and academic theorizing on Internet use, lifestyles, and oral health-related quality of life, especially among adolescents. The confirmation of the proposed hypotheses highlights the urgent need to address Problematic Internet Use (PIU) and its impact on the health and well-being of young people, not only from a reactive approach but also a preventive and educational one.

Health professionals, educators, and caregivers should be equipped with resources and training to identify signs of PIU and its potential impact on adolescent lifestyles and oral health-related quality of life. Integrated intervention strategies that address healthy Internet use and healthy lifestyle habits, including oral hygiene-related quality of life, should be promoted. This involves developing educational programs that teach young people to manage their time online effectively and recognize the importance of maintaining a balance between digital and physical activities.

The findings underscore the importance of policymakers integrating digital well-being into national public health strategies. Policies promoting equitable access to oral health education and healthy lifestyles are essential, especially in disadvantaged communities. Public policies should encourage the creation of safe and accessible online spaces that promote positive Internet use while combating the risks associated with its problematic use.

This study contributes to the existing literature by providing a theoretical model linking PIU, lifestyles, and oral health-related quality of life. Future research should explore how these elements interact in different cultural and socioeconomic contexts. Expanding the theoretical base to include additional mediating and moderating variables that may influence these relationships, such as individual resilience, social support, and family context, is crucial.

Limitations

A significant limitation of our study is its cross-sectional design. This design allows us to identify associations between variables at a specific time but does not establish causality. Future research should consider longitudinal designs to examine how these relationships evolve and more firmly establish the direction of causality. Furthermore, non-probabilistic sample selection may limit the generalizability of our findings. The participants were Peruvian students between 12 and 17 years old, which suggests that the results may not directly apply to populations of different cultural contexts, ages, or educational systems. Future research could benefit from more diverse and representative samples to examine whether the patterns observed in this study hold across different demographic and geographic groups. Finally, although we have explored the mediation of lifestyles in the relationship between PIU and oral health-related quality of life, other potential factors that could influence this dynamic have not been considered. For example, psychosocial variables such as family support, mental health, access to health services, and some habits as dental brushing and the type of diet followed by the participants could play important roles. Future research should include these and other factors to gain a more holistic understanding of how PIU affects oral health-related quality of life indirectly through lifestyles.

Conclusion

The present study confirms the interaction between problematic Internet use (PIU), lifestyles, and oral health-related quality of life in adolescents. By confirming that lifestyles significantly mediate the relationship between PIU and oral health-related quality of life, our research underscores the importance of jointly addressing digital behavior and healthy lifestyle habits to improve oral health-related quality of life outcomes among youth. In this sense, balanced time management and adopting healthy lifestyle practices can mitigate the negative effects of PIU on oral health-related quality of life.

Author contributions

M.M.G-P and A.A.R-H conceptualized, collected the data, and contributed manuscript writing. E.E.N-N designed the study, contributed to the interpretation of the findings, and manuscript writing. W.M-G did the data processing, contributed to data analysis and manuscript writing. S.H-V contributed with interpretation of the findings and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research and authorship of this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding autor.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Peruana Unión (2022-CEUPeU-026). All methods were performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents or legal representatives/guardians of all students before the start of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lahti H, Lyyra N, Hietajärvi L, Villberg J, Paakkari L. Profiles of internet use and health in adolescence: a person-oriented Approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Torous J, Bucci S, Bell IH, Kessing LV, Faurholt-Jepsen M, Whelan P, et al. The growing field of digital psychiatry: current evidence and the future of apps, social media, chatbots, and virtual reality. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):318–35. 10.1002/wps.20883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Condori-Meza IB, Dávila-Cabanillas LA, Challapa-Mamani MR, Pinedo-Soria A, Torres RR, Yalle J, et al. Problematic internet use Associated with symptomatic Dry Eye Disease in Medical students from Peru. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:4357–65. 10.2147/OPTH.S334156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szymkowiak A, Melović B, Dabić M, Jeganathan K, Kundi GS. Information technology and Gen Z: the role of teachers, the internet, and technology in the education of young people. Technol Soc. 2021;65:101565. 10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101565 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moscardelli DM, Divine R. Adolescents’ concern for privacy when using the internet: an empirical analysis of predictors and relationships with privacy-protecting behaviors. Family Consumer Sci Res J. 2007;35(3):232–52. 10.1177/1077727X06296622 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Livingstone S. Young people and new media: Childhood and the changing media environment. Young People and New Media. 2002:1-278.

- 7.Almoddahi D, Machuca Vargas C, Sabbah W. Association of dental caries with use of internet and social media among 12 and 15-year-olds. Acta Odontol Scand. 2022;80(2):125–30. 10.1080/00016357.2021.1951349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elbilgahy AA, Sweelam RK, Eltaib FA, Bayomy HE, Elwasefy SA. Effects of electronic devices and internet addiction on sleep and academic performance among female Egyptian and Saudi nursing students: a comparative study. SAGE Open Nurs. 2021;7:23779608211055614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghareghol H, Pakkhesal M, Naghavialhosseini A, Ahmadinia AR, Behnampour N. Association of problematic internet use and oral health-related quality of life among medical and dental students. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):11. 10.1186/s12909-021-03092-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Ansari A, El Tantawi M, AlMadan N, Nazir M, Gaffar B, Al-Khalifa K, et al. Internet addiction, oral Health practices, clinical outcomes, and self-perceived oral health in young Saudi adults. Scientific World J. 2020;2020:7987356. 10.1155/2020/7987356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwasaki M, Kakuta S, Ansai T. Associations among internet addiction, lifestyle behaviors, and dental caries among high school students in Southwest Japan. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):17342. 10.1038/s41598-022-22364-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olczak-Kowalczyk D, Tomczyk J, Gozdowski D, Kaczmarek U. Excessive computer use as an oral health risk behaviour in 18-year-old youths from Poland: a cross-sectional study. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2019;5(3):284–93. 10.1002/cre2.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klavina A, Veliks V, Zusa-Rodke A, Porozovs J, Aniscenko A, Bebrisa-Fedotova L, editors. The associations between problematic internet use, healthy lifestyle behaviors and health complaints in adolescents. Frontiers in education. Frontiers Media SA; 2021.

- 14.Kojima R, Sato M, Akiyama Y, Shinohara R, Mizorogi S, Suzuki K, et al. Problematic internet use and its associations with health-related symptoms and lifestyle habits among rural Japanese adolescents. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;73(1):20–6. 10.1111/pcn.12791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao L, Gan Y, Whittal A, Lippke S. Problematic internet use and perceived quality of life: findings from a cross-sectional study investigating work-time and leisure-time internet use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):4056. 10.3390/ijerph17114056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Islam MS, Sujan MSH, Tasnim R, Ferdous MZ, Masud JHB, Kundu S, et al. Problematic internet use among young and adult population in Bangladesh: correlates with lifestyle and online activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addict Behav Rep. 2020;12:100311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yıldız İ, Yıldırım F. The relation between problematic internet use and healthy lifestyle behaviours in high school students. Adv School Mental Health Promotion. 2012;5(2):93–104. 10.1080/1754730X.2012.691355 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Do KY, Lee KS. Relationship between problematic internet use, sleep problems, and oral health in Korean adolescents: a National Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Ato M, López-García JJ, Benavente A. Un Sistema De clasificación De Los diseños de investigación en psicología. Anales De Psicología/Annals Psychol. 2013;29(3):1038–59. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boubeta AR, Salgado PG, Folgar MI, Gallego MA, Mallou JV. PIUS-a: problematic internet use scale in adolescents. Development and psychometric validation EUPI-a: Escala De Uso Problemático De Internet en adolescentes. Desarrollo Y validación psicométrica. Adicciones. 2015;27(1):47–63. 10.20882/adicciones.193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murillo-Llorente MT, Brito-Gallego R, Alcalá-Dávalos ML, Legidos-García ME, Pérez-Murillo J, Perez-Bermejo M. The validity and reliability of the FANTASTIC questionnaire for Nutritional and Lifestyle studies in University students. Nutrients. 2022;14(16):3328. 10.3390/nu14163328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abanto J, Albites U, Bönecker M, Martins-Paiva S, Castillo JL, Aguilar-Gálvez D. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric properties of the child perceptions Questionnaire 11–14 (CPQ11-14) for the Peruvian Spanish language. Med oral Patologia oral y Cir Bucal. 2013;18(6):e832. 10.4317/medoral.18975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasselkvist A, Johansson A, Johansson AK. Association between soft drink consumption, oral health and some lifestyle factors in Swedish adolescents. Acta Odontol Scand. 2014;72(8):1039–46. 10.3109/00016357.2014.946964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alm A, Isaksson H, Fåhraeus C, Koch G, Andersson-Gäre B, Nilsson M, et al. BMI status in Swedish children and young adults in relation to caries prevalence. Swed Dent J. 2011;35(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu H, Zhou H, Qin Q, Zhang W. Association between smoking and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, tooth brushing among adolescents in China. Child (Basel). 2022;9(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Santoso CMA, Bramantoro T, Nguyen MC, Nagy A. Lifestyle and psychosocial correlates of oral hygiene practice among Indonesian adolescents. Eur J Oral Sci. 2021;129(1):e12755. 10.1111/eos.12755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park MH, Park S, Jung KI, Kim JI, Cho SC, Kim BN. Moderating effects of depressive symptoms on the relationship between problematic use of the internet and sleep problems in Korean adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):280. 10.1186/s12888-018-1865-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almoraie NM, Saqaan R, Alharthi R, Alamoudi A, Badh L, Shatwan IM. Snacking patterns throughout the life span: potential implications on health. Nutr Res. 2021;91:81–94. 10.1016/j.nutres.2021.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mobley C, Marshall TA, Milgrom P, Coldwell SE. The contribution of dietary factors to dental caries and disparities in caries. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(6):410–4. 10.1016/j.acap.2009.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mestaghanmi H, Labriji A, M’Touguy I, Kehailou FZ, Idhammou S, Kobb N, et al. Impact of eating habits and Lifestyle on the oral health status of a Casablanca’s Academic Population. Open Access Libr J. 2018;5(11):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 31.You HW. Modelling analysis on dietary patterns and oral health status among adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(22). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Alcaina Lorente A, Saura López V, Pérez Pardo A, Guzmán Pina S. Cortés Lillo O. Salud oral: influencia de Los estilos de vida en adolescentes. Pediatría Atención Primaria. 2020;22(87):251–61. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brondani B, Sfreddo CS, Knorst JK, Ramadan YH, Ortiz FR, Ardenghi TM. Oral health-related quality of life as a predictor of alcohol and cigarette consumption in adolescents. Braz Oral Res. 2022;36:e025. 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2022.vol36.0025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dib JE, Haddad C, Sacre H, Akel M, Salameh P, Obeid S, et al. Factors associated with problematic internet use among a large sample of Lebanese adolescents. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):148. 10.1186/s12887-021-02624-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sardiñas SAV, Gutíerrez DH, Pombo AB, Morales XS, Tejera AF, López GM. El Tabaquismo Y Su asociación con la salud bucal de Los adolescentes. Acta Médica Del Centro. 2020;14(1):44–52. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pontes HM, Macur M. Problematic internet use profiles and psychosocial risk among adolescents. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(9):e0257329. 10.1371/journal.pone.0257329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shuai L, He S, Zheng H, Wang Z, Qiu M, Xia W, et al. Influences of digital media use on children and adolescents with ADHD during COVID-19 pandemic. Global Health. 2021;17(1):48. 10.1186/s12992-021-00699-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding autor.