Abstract

The integration of assisted dying into end-of-life care is raising reflections on bereavement. Patients and families may be faced with a choice between this option and natural death assisted by palliative care; a choice that may affect grief. Therefore, this study describes and compares grief experiences of individuals who have lost a loved one by medical assistance in dying or natural death with palliative care. A mixed design was used. Sixty bereaved individuals completed two grief questionnaires. The qualitative component consisted of 16 individual semi-structured interviews. We found no statistically significant differences between medically assisted and natural deaths, and scores did not suggest grief complications. Qualitative results are nuanced: positive and negative imprints may influence grief in both contexts. Hastened and natural deaths are death circumstances that seem to generally help ease mourning. However, they can still, in interaction with other risk factors, produce difficult experiences for some family caregivers.

Keywords: grief, bereavement, medical assistance in dying, euthanasia, palliative care

In Quebec, Canada, as in other parts of the world, medical assistance in dying (MAiD) continues to spark debate. However, there is still little empirical evidence available to inform care policies and understand the full implications of what the Quebec legislator defines as: “care consisting in the administration by a physician of medications or substances to an end-of-life patient, at the patient’s request, in order to relieve their suffering by hastening death.” (Government of Quebec, 2021). Further investigation seems necessary not only to understand MAiD’s impact on patients and health professionals, but also to understand how families, those who “survive” the loss of a significant person, cope with this type of death (Andriessen et al., 2019; Gamondi et al., 2019; Variath et al., 2020). To this end, several researchers have contributed to the empirical literature on grief in the context of assisted dying (an umbrella term that includes euthanasia and assisted suicide), particularly in recent years.

Grief after MAiD is being increasingly described as an experience that is no more challenging or more complex than grief in other dying contexts (e.g., natural/not hastened death, and suicide) (Andriessen et al., 2019; Arteau, 2019; Aubin-Cantin, 2020; Ganzini et al., 2009; Hashemi et al., 2021; Holmes et al., 2018; Lowers et al., 2020; Srinivasan, 2018). It may even be easier (Swarte et al., 2003). However, several scholars invite researchers and clinicians to consider the existence of both positive and negative impacts on the experience (Beuthin et al., 2021; Brown et al., 2020; Frolic et al., 2020; Gamondi et al., 2015, 2018; Hales et al., 2019; Schutt, 2020; Starks et al., 2007; Srinivasan, 2018; Wagner et al., 2011, 2012a, 2012b). Some potential risk factors for more complicated or prolonged grief have been identified: family disagreements (Arteau, 2019; Kimsma & van Leeuwen, 2007; Srinivasan, 2018; Starks et al., 2007), value conflicts (Gamondi et al., 2015; Srinivasan, 2018), having to deal with the procedures and authorities that structure the assisted death’s trajectory (Arteau, 2019; Brown et al., 2020; Hales et al., 2019; Wagner et al., 2011, 2012a), the presence and/or perception of negative judgments, social stigma, and silence (Hales et al., 2019; Gamondi et al., 2018; Schutt, 2020; Srinivasan, 2018; Starks et al., 2007, 2012a), and the sheer fact of witnessing death, a potentially traumatic experience (Wagner et al., 2012b). Conversely, factors that may protect or facilitate the grieving process have also been postulated: family consensus and consistency between personal values and assisted death (Srinivasan, 2018), being able to prepare oneself for the death and say goodbye (Aubin-Cantin, 2020; Beuthin et al., 2021; Hashemi et al., 2021; Holmes et al., 2018; Srinivasan, 2018; Starks et al., 2007; Swarte et al., 2003), a feeling of control over the other’s suffering and end-of-life—not having to witness a slow decline (Beuthin et al., 2021; Hashemi et al., 2021; Srinivasan, 2018), and the power to act, to get involved in the procedures, planning, and last wishes, which makes it possible to counteract the powerlessness experienced in the face of the suffering and death of the loved one (Beuthin et al., 2021; Hashemi et al., 2021; Schutt, 2020). However, the relative weight of each of these factors in families’ experiences has not yet been assessed. Nor does this categorization of factors fully account for the phenomenon’s complexity and the inter- and intra-individual differences. As several researchers have pointed out in their literature review (Andriessen et al., 2019; Gamondi et al., 2019), more studies are still needed to understand the diversity of grief dynamics in such circumstances. It also seems relevant to collect data in different cultural, legal and care delivery contexts since the experiences of family members can be influenced by the environment in which they unfold (Gamondi et al., 2019; Variath et al., 2020).

In addition, the current empirical literature has several limitations that require caution in considering the various studies’ findings and highlight the need for differently designed studies (Andriessen et al., 2019). For example, although some researchers compare bereavement in assisted death’s context to comparison groups of bereaved individuals in natural death’s context (Ganzini et al., 2009; Swarte et al., 2003), none of these authors specify whether natural deaths were assisted by palliative care. And yet, the effects of palliative care interventions on the well-being of patients and family members have been described (Kavalieratos et al., 2016; Kustanti et al., 2021) and a natural death without specialized end-of-life care cannot be considered equivalent to a death with palliative care. In this respect, it is possible to consider a natural death assisted by palliative care (NDPC) as the current “gold standard” in terms of best practices in end-of-life care and for death preparation. Participants in many qualitative studies on assisted dying even spontaneously compare their grief experience to other experiences in the context of natural death (Arteau, 2019; Aubin-Cantin, 2020; Hashemi et al., 2021; Holmes et al., 2018). Such a comparison allows to distinguish the needs that are specific to a certain group of bereaved individuals (if any), to compare two types of death that can be considered anticipated, and to adapt death preparation and support services according to the particularities of each type of experience (Lowers et al., 2020). It should be noted that NDPC are also worthy of study in their own right. Indeed, one can argue that assisted dying’s integration into the landscape of end-of-life care is coloring and perhaps changing how natural death and the associated bereavements are enacted (Richards & Krawczyk, 2021).

In light of these premises, this study’s goal is to describe the grief experiences of individuals who have lost a loved one through MAiD or NDPC in Quebec. The similarities and differences between the experiences described in these two contexts, as well as the implications for family support, will be discussed.

Methods

Design and Participants

To provide a detailed understanding of the grief phenomenon, we employed a mixed design, combining qualitative and quantitative methods (Creswell & Clark, 2017; Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2010). The qualitative component allows the exploration of grief experiences as described by bereaved individuals in MAiD and NDPC contexts. The quantitative component is used to assess certain symptoms associated with more difficult bereavements and for a direct comparison between the two populations. The integration of the two sets of data may reveal dynamics and explanations that would otherwise remain obscure (Creswell & Clark, 2017).

Participants have lost a loved one by MAiD or NDPC. A “family member” was defined as a person who was related to the deceased by a biological bond, an acquired bond (e.g., spouse and adoption) or a bond of friendship (Kristjanson & Aoun, 2004). Selection criteria included: to be 18 years of age or older, to be able to read, understand and speak French or English, and to have been bereaved for a minimum of 6 months and a maximum of 4 years. As of March 12, 2020, the end-of-life criterion as part of Quebec legislation to receive MAiD no longer applies. However, the data collected for this study exclusively concerns individuals who have lost a loved one at the end of one’s life.

Data Collection

After receiving approval from Université de Montréal’s Education and Psychology Research Ethics Board, participant recruitment was conducted between October 10, 2019, and October 19, 2020 within the province of Quebec via postings on social media and through networks of researchers, clinicians, and community organizations. Interested participants first took part in the study’s quantitative component by completing online questionnaires and then indicated whether they wished to be considered for an in-depth semi-structured individual interview about their grief experience. The quantitative sample consists of 25 individuals bereaved by MAiD and 35 bereaved by NDPC. The qualitative subsample was constructed by selecting a few interested participants. Participants for the qualitative component of the study were chosen to diversify the subsample as much as possible according to factors that may influence grief (Stroebe et al., 2007) (e.g., age, sex, relationship type, and time elapsed since death). The interviews lasted between 65 and 131 minutes (mean = 86) and were conducted by the lead author who has considerable experience with interviews in the context of bereavement and end-of-life. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, three interviews were conducted online on the Zoom Video Communications, Inc. software. It is worth mentioning that the participants’ loved ones had all passed away before the onset of the pandemic. Participants stated that the current context did not have a major influence on the way they grieved and felt comfortable during the online interview. Recent evidence supports the idea that online “videoconference” interviews may produce the same data richness as in-person interviews (Namey et al., 2020). All interviews were subsequently transcribed verbatim and the quality of the transcripts was assessed. The qualitative sample size (MAiD = 8, NDPC = 8, see Table 1) was informed and revised according to the information power concept (Malterud et al., 2016). Thus, we do not claim to have achieved empirical saturation. However, our sample provides a deep and novel understanding of the phenomenon under study.

Table 1.

Quantitative and Qualitative Samples Sociodemographic Variables.

| Quantitative Sample | MAiD (n = 25) | NDPC (n = 35) | ||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Age | 47.16 (16.16) | 43.15 (15.61) | ||

| Time elapsed since death (in months) | 16.60 (11.67) | 18.69 (11.94) | ||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 19 | 76.00 | 32 | 91.43 |

| Male | 6 | 24.00 | 3 | 8.57 |

| Education | ||||

| Elementary | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 2.86 |

| High school | 3 | 12.00 | 2 | 5.71 |

| Postsecondary education | 22 | 88.00 | 32 | 91.43 |

| Spiritual/Religious beliefs | ||||

| Christian | 13 | 52.00 | 9 | 25.71 |

| Atheist or agnostic | 12 | 48.00 | 17 | 48.57 |

| Other | 0 | 0.00 | 9 | 25.71 |

| The deceased loved one place of death Hospital | 16 | 64.00 | 13 | 37.14 |

| Hospice | 3 | 12.00 | 13 | 37.14 |

| Home | 6 | 24.00 | 7 | 20.00 |

| Long-term care facility (CHSLD) | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 5.71 |

| The deceased loved one illness | ||||

| Cancer | 19 a | 73.08 | 29 b | 76.32 |

| Other | 7 a | 26.92 | 9 b | 23.68 |

| Relationship with the deceased loved one | ||||

| First- and second-degree relationship (mother, father, brother, sister, spouse, ex-spouse, children) | 19 | 76.00 | 30 b | 78.95 |

| Other relationship (grandmother, grandfather, friend, father-in-law, uncle, aunt, cousin) | 6 | 24.00 | 8 b | 21.05 |

| Involvement during the deceased loved one’s end-of-life | ||||

| Frequency of visits | ||||

| Less than 1 day a week | 4 | 16.00 | 4 | 11.43 |

| 1–2 days a week | 4 | 16.00 | 5 | 14.29 |

| 3–4 days a week | 3 | 12.00 | 3 | 8.57 |

| 5–6 days a week | 5 | 20.00 | 1 | 2.86 |

| 7 days a week | 9 | 36.00 | 22 | 62.86 |

| Duration of visits | ||||

| Less than 30 minutes | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 5.71 |

| Between 30 and 60 minutes | 4 | 16.00 | 2 | 5.71 |

| Between 1 and 3 hours | 7 | 28.00 | 8 | 22.86 |

| Quantitative Sample | MAiD (n = 25) | NDPC (n = 35) | ||

| Between 3 and 5 hours | 7 | 28.00 | 3 | 8.57 |

| More than 5 hours | 7 | 28.00 | 20 | 57.14 |

| MAiD’s degree of favorability | ||||

| To what extent are you in favor of MAiD? | ||||

| Very much in favor | 21 | 84.00 | 18 | 51.43 |

| In favor | 4 | 16.00 | 10 | 28.57 |

| Neither in favor nor against it | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 5.71 |

| Against it | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 11.43 |

| Very much against it | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 2.86 |

| To what extent do you think your family, friends, and colleagues are in favor of MAiD? | ||||

| Very much in favor | 11 | 44.0 | 8 | 22.86 |

| In favor | 12 | 48.00 | 18 | 51.43 |

| Neither in favor nor against it | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 2.86 |

| Against it | 1 | 4.00 | 2 | 5.71 |

| Very much against it | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 5.71 |

| Have no idea | 1 | 4.00 | 4 | 11.43 |

| To what extent to you think the society of Quebec is in favor of MAiD? | ||||

| Very much in favor | 1 | 4.00 | 4 | 11.43 |

| In favor | 19 | 76.00 | 23 | 65.71 |

| Neither in favor nor against it | 2 | 8.00 | 4 | 11.43 |

| Against it | 2 | 8.00 | 2 | 5.71 |

| Very much against it | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Have no idea | 1 | 4.00 | 2 | 5.71 |

| Qualitative sample | MAiD (n = 8) | NDPC (n = 8) | ||

| M (Range) | M (Range) | |||

| Age | 49.00 (25–68) | 49.63 (25–72) | ||

| Time elapsed since death (in months) c | 19.13 (6–47) | 17.25 (10–24) | ||

| RGEI global score | 66.38 (39–104) | 61.75 (30–104) | ||

| PG-13 continuous score d | 25.38 (19–34) | 21.75 (12–32) | ||

| Sex | Female (6), male (2) | Female (6), male (2) | ||

| Beliefs | Christian (3), atheist (3), agnostic (2) | Christian (3), atheist (3), Muslim (1), spiritual (1) | ||

| Relationship with the deceased loved one | Mother (2), spouse (2), father (1), grandmother (1), cousin (1), friend (1) | Father (2), mother and father (1) e , spouse (1), ex-spouse (1), brother (1), daughter (1), grandmother (1) | ||

| The deceased loved one place of death | Hospital (5), hospice (2), home (1) | Hospital (4), hospice (2), hospital and hospice (1) e , home (1) | ||

| The deceased loved one illness | Cancer (2), leukemia (1), esophagus cancer (1), lung cancer (1), pulmonary disease (1), renal dysfunction/double cervical fracture (1), old age/generalized pain (1) | Cancer (3), colon cancer (1), liver cancer (1), cervical glioblastoma (1), lewy body dementia (1), arteriopathy obliterans/stroke/treatment refusal and colon cancer (1) e | ||

| Involvement during the deceased loved one’s end of life | ||||

| Frequency of visits | 7 days a week (5), 5–6 days a week (1), 3–4 days a week (1), 1–2 days a week (1) | 7 days a week (5), 3–4 days a week (1), 1–2 days a week (1), less than 1 day a week (1) | ||

| Duration of visits | More than 5 hours (4), 3–5 hours (2), 30–60 minutes (2) | More than 5 hours (6), 1–3 hours (2), less than 30 minutes (1) | ||

MAiD = Medical assistance in dying; NDPC = Natural death assisted by palliative care; RGEI = Revised Grief Experience Inventory; PG-13 = Prolonged Grief-13.

a1 participant in the MAiD group reported that his loved one had died from a bladder cancer and heart problems. He did not prioritize one of these medical conditions as the primary cause of death. Therefore, we decided to consider both illnesses. For this item, the total n for the MAiD group is 26.

b3 participants reported having lost more than one loved one in the NDPC group. They have reported more than one illness and more than one relationship with the deceased. For those two items, the total n for the NDPC group is therefore 38. As all the other items were multiple-choice, we cannot determine whether these 3 participants were referring to only one of their deceased loved ones when answering the questionnaires or to their two deceased loved ones at the same time.

cTime elapsed when the interview took place.

dContinuous score: the cut-off score for Prolonged Grief Disorder’s diagnosis proposed by Pohlkamp and colleagues (2018) is 35.

eOne interviewee lost both her father and mother in a short period of time. She felt like she was grieving for both parents at the same time and talked about both during her interview.

Measures

The 60 bereaved participants in the quantitative sample completed a sociodemographic information sheet and two short grief questionnaires. The Prolonged Grief-13 (PG-13) (Prigerson et al., 2009) is composed of 13 items and allows to assess the presence of prolonged grief disorder. This questionnaire has been translated and validated into several languages and is widely used. However, the French version (home translation) used in the present study has not yet been validated. The translation of the PG-13 was carried out according to the method discussed by Wild et al. (2005) (translation in French and back translation in English). The Revised Grief Experience Inventory (RGEI) (Lev et al., 1993) is a questionnaire that describes grief along four scales: (1) existential tension, (2) depression, (3) guilt, and (4) physical distress. Its psychometric properties are deemed adequate by Sealey et al. (2015) who conducted a review of grief assessment measures. Its global Cronbach’s alpha is 0.93. The RGEI consists of 22 items that inform beyond the intensity or complexity of grief by identifying which of four types of grief domains are more present in the experience. However, the French version of the RGEI has not been validated either. Finally, as part of the qualitative component, we designed a semi-structured interview grid informed by grief theories’ literature (see Supplemental Material). To ensure a critical and transparent approach, we also maintained a journal, in which reflective and analytical notes were recorded (Thorne, 2016).

Data Analysis

The analyses of the quantitative and qualitative data were undertaken separately. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 26 software. Descriptive statistics were produced in order to describe the sample on a sociodemographic level. Inferential statistics (ANCOVA) were also performed to compare the two groups of bereaved individuals on their continuous scores on the PG-13, their global grief intensity scores on the RGEI, and their scores on the RGEI’s four dimensions. We previously performed various tests (t-tests, chi-square tests, and Pearson correlations) to determine whether the two groups differed according to confounding variables (e.g., age, time since death, and illness of the deceased). We then considered the effect of the sole problematic confounding variable in our subsequent calculations. In addition, only one missing data was identified.

The qualitative data analysis was inspired by Interpretive Description (Thorne, 2016), an approach frequently used in applied health research that is epistemologically consistent with mixed-methods research and encourages the researcher to produce meaningful results that go beyond description and simple records of themes. We conducted an initial open-ended reading of the interview transcripts in order to familiarize ourselves with the content. We then produced codes that we gradually regrouped and refined, moving from a more descriptive level to a more interpretive one. We carried out these different steps in an iterative fashion for each transcript. Then, we created four corpora of four transcripts (4 MAiD, 4 MAiD, 4 NDPC, and 4 NDPC) that we analyzed in turn to produce increasingly refined and transversal themes. We finally merged the corpora one last time in order to identify similarities and differences between the experiences in MAiD and NDPC contexts.

The qualitative and quantitative analyses’ results were combined at the end of the analytical process so as to identify convergences, divergences, nuances, and hypotheses/explanations revealed only through the integration of the two types of data (Pluye et al., 2018).

Results

Quantitative Results

Sociodemographic Variables and MAiD’s Degree of Favorability

Bereaved participants in the MAiD and NDPC groups are very similar with respect to the majority of sociodemographic variables (see Table 1). It should be noted, however, that both samples are overwhelmingly female. Unfortunately, the recruitment of men was challenging. The results may be less representative of their experiences.

Social stigma and fear of negative judgment about the death’s modality is a complicative factor of grief that has been reported regularly in grief literature with assisted death (Hales et al., 2019; Gamondi et al., 2018; Srinivasan, 2018; Starks et al., 2007; Wagner et al., 2012a). It is interesting to observe that participants in both bereaved groups were mainly in favor of MAiD, in addition to having the impression that their entourage (family, friends, and colleagues) and Quebec society were also in favor of this practice (see Table 1). Although a direct association cannot be made between the degree of perceived favorability and the fear of social stigma, our results tend to indicate that the social environment is experienced as generally welcoming towards MAiD.

Grief Outcomes

The two groups did not differ on grief distress. No statistically significant or even marginally significant differences were found on the PG-13 and RGEI scores (see Table 2). Moreover, the two types of bereavement do not appear to be generally associated with high levels of grief symptomatology. To this end, no participants met the minimal criteria for a PG-13 diagnosis of prolonged grief disorder and only three participants (1 MAiD, 2 NDPC) scored above the cut-off proposed by Pohlkamp et al. (2018) to screen cases of prolonged grief. The psychopathological symptomatology of grief is therefore marginal, if not absent in both groups. Global mean scores on the RGEI (MAiD: M = 57.52; NDPC: M = 56.40) also remain “typical,” even lower, when compared to scores from several other samples of bereaved individuals (Kowalski & Bondmass, 2008; Lev et al., 1993; MacKinnon et al., 2015; MacKinnon et al., 2016; Robinson & Marwit, 2006). Based only on these results, MAiD and NDPC could be regarded both as death contexts with the potential to produce softer grief experiences than in many other circumstances.

Table 2.

Quantitative Analysis Results.

| MAiD (n = 25) | NDPC (n = 35) | Comparison between the groups (ANCOVA) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Scale Range a | M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | Range | Diff | F | Sign | Effect Size |

| PG-13 (continuous score) b | 11.00–55.00 | 22.52 (6.90) | 12.00–38.00 | 22.11 (8.14) | 11.00–43.00 | 0.41 | 0.215 | 0.645 | 0.004 |

| RGEI – global score | 22.00–132.00 | 57.52 (24.27) | 22.00–104.00 | 56.40 (24.32) | 22.00–104.00 | 1.12 | 0.534 | 0.468 | 0.009 |

| Physical distress | 7.00–42.00 | 16.32 (7.80) | 7.00–30.00 | 15.74 (7.20) | 7.00–32.00 | 0.58 | 0.992 | 0.324 | 0.017 |

| Existential tension | 6.00–36.00 | 15.32 (7.72) | 6.00–33.00 | 14.40 (7.70) | 6.00–31.00 | 0.92 | 0.712 | 0.402 | 0.013 |

| Guilt | 3.00–18.00 | 6.56 (3.37) | 3.00–14.00 | 7.37 (3.70) | 3.00–15.00 | −0.81 | 0.191 | 0.664 | 0.003 |

| Depression | 6.00–36.00 | 19.32 (8.12) | 6.00–34.00 | 18.89 (8.13) | 6.00–32.00 | 0.43 | 0.395 | 0.532 | 0.007 |

MAiD = Medical assistance in dying; NDPC = Natural death assisted by palliative care; RGEI = Revised grief experience inventory; PG-13 = Prolonged Grief-13; ANCOVA = Analysis of covariance.

aScale range refers to minimum and maximum scores. Higher scores on the PG-13 and RGEI global score indicate greater grief distress/intensity. Higher scores on the RGEI subscales indicate that these grief dimensions are more problematic for the individual.

bThe cut-off score for Prolonged Grief Disorder’s diagnosis proposed by Pohlkamp and colleagues (2018) is 35.

Qualitative Results

We consider that death circumstances can influence grief through the images, traces, symbols or “imprints” they leave in the memory of the individual. These imprints are more or less vivid and anchored in the mind. More so, these are constructed and reconstructed time and time again by the bereaved person. We have conceptualized them into two stages: imprints that may color the experiences of (1) the last moments before death and (2) the separation.

On the Edge of Death: Imprints of Distance

End-of-life in the context of MAiD and NDPC are similar in some respects. Both contexts have the potential to foster greater distance or conversely greater proximity between the dying person and family members. This distance is temporal, as it is expressed in rhythms that we describe as synchronous or asynchronous.

Distance and Asynchrony. When the rhythms are asynchronous, the rational and especially emotional understanding of the impending death does not occur at the same speed. “My heart was not there yet,” said one of our participants. In the context of MAiD, this difference in rhythm can take the form of time passing much too quickly and/or much too slowly “and it is agonizing.” Time may be omnipresent (an extreme awareness of the hours and minutes passing) and tinted with incomprehension: the dying person keeps secrets, his/her experience remains in part impenetrable. The understanding of the family member comes with delay or is done differently. For some participants, the rhythm is not their own, it is imposed on them.

I don’t like MAiD, not at all, it’s not a nice experience [crying]. I’m trying to remember things and it’s just ... I find it aggressive. You don’t choose the rhythm. So, we should have more choice on the pace of how it goes. [Interviewer: As if the rhythm was imposed on you?] Yes. And for me, it was too fast. Oh sure, if I put myself in my spouse’s shoes, he’ll never think that it was too fast. You know, the person is alive, yes, he’s sick, but he’s been sick for a long time, and now he’s ... he’s breathing, and now a fraction of a second and he’s not breathing [crying]. You see, how it’s still so painful [for me]. (Participant who lost her spouse to MAiD)

These imprints of temporal distance, where we fail to come together, can still be very painful even months after death. In the context of NDPC, asynchrony can be embodied in a rhythm that ultimately remains uncontrollable and where death continues to surprise even if anticipated.

I believed in it until the end, even when he fell into a coma, I thought he was going to wake up, and that he was going to get stronger. […] And I think he saw that I was sad. Because he didn’t want me to be sad anymore. So, he acted like nothing was wrong. And I find that ... that’s something that bothers me, and I often think about why it was like that [that we did not talk about death]. And especially knowing that he talked about it with others. So, he knew that he was going to die. But he didn’t tell me. That’s why when he died, I was so surprised, because I didn’t expect him to die. He was in palliative care, but still ... (Participant who lost her spouse to NDPC)

Unlike death by MAiD, death imminence can be avoided in NDPC by both individuals and a distance can be maintained in this regard. One’s denial, which illustrates that the family member and the dying person are not at the same point in their integration and understanding of death, is also possible thanks to the abstract or less concrete nature of the forthcoming passing away. One interviewee recalls that her mother remained in denial of her own end-of-life for a long time and that this was a source of conflict between the two. However, when her mother suddenly became aware of her impending death, this shift in perception was no easier to live with.

It was like almost as bad. It’s hard ... it was as hard. You know, you go from denial to: “Okay.” It was weird. Because as long as my mother was not suffering, for her, she was cured. But from the moment she started suffering, she said to herself: “Okay, the cancer won.” That’s when she started to change her approach at the end, you know, she changed her way of... of doing things. [Interviewer: She kind of went from one extreme to the other, just like that.] From one extreme to the other ... from one extreme to the other big bang! That’s exactly it, yeah. (Participant who lost her mother and father to NDPC)

This participant’s mother has integrated the reality of her own death at a pace that is not her daughter’s. And again, this difference in rhythm “it’s hard.” NDPC can also be experienced as shortened, rushed, and quick, as can be the case with MAiD. This finding may be surprising, but it highlights the fact that two participants had to deal with death in the context of terminal palliative sedation performed emergently, when initially the dying person was to receive MAiD. The dying individuals were in too much suffering to wait until the scheduled date for MAiD and decided to hasten their farewells by using continuous palliative sedation (administering medications or substances to an end-of-life patient to relieve their suffering by rendering them unconscious without interruption until death ensues).

Proximity and Synchrony: At the other end of the spectrum, we have participants who feel that they are getting closer to their loved one and moving at the same pace. For these people, MAiD does not hasten death. Rather, it comes at the right time, at the end of a fully accomplished life and death process. The imminence of death is experienced quite serenely.

You know, it’s not a person who suddenly dies, and you feel sad at that moment. It was really something that happened over time. [...] You know, the relationship really remained there, but it was just, you die quietly like a soft fire. The fire goes out slowly, and then we stayed there, both of us, until the end. I think it was a beautiful moment. (Participant who lost her father to MAiD)

We also postulate that some participants voluntarily adjusted their rhythm to feel closer to their loved one. The other’s wish to die by MAiD, his/her last wishes, became family members’ life mission. There is an urgent need to have the loved one’s wishes respected and to fight even against the health care system, professionals or any other person who would oppose MAiD’s request for example. And when the bereaved individuals feel that they have fully fulfilled their role as an advocate, they seem to experience some degree of relief in their grief.

The fact that she is 85 years old that ... that I managed to get what she wanted, which was MAiD. Um, it was a relief to me, you know. Because ... um, it had gone so badly the previous months that I said to myself: “You know, okay. I was successful in my mandate.” (Participant who lost her mother to MAiD)

For participants in the context of NDPC, the “going with the flow” metaphor, used by one interviewee, illustrates how the synchronization of rhythms can be experienced. Time is described as less omnipresent and unbearable than within MAiD’s context. Without a predefined appointment with death, both the dying person and their loved one have the time to gradually come to terms with the upcoming death. They mature together and experience themselves as a “fruit that is ripe enough to fall off the tree by itself, instead of cutting it while it is still green.” (Participant who lost her ex-spouse to NDPC)

When Death Do Us Part: Imprints of Hero

Once the waiting and the last moments of life are completed, death comes to permanently separate our participants from their loved one. We have noticed that our bereaved interviewees retain certain images or attributes of the deceased with respect to this final separation. In other words, they seem to be inhabited by images of what their loved one personified at the moment of their passing.

We have grouped the various representations of the dying person who leaves us (or symbolically remains with us) under the hero’s heading. This terminology may seem a bit strong and must admittedly be tempered according to individual experiences. Yet, what we were told by participants seemed to echo Tourret’s (2011) description of the modern hero. To understand the heroism behind deaths by MAiD and NDPC, we refer to courage, the idea of defying “evil’s” forces (death, suffering, and their pernicious effects), as well as a being who is truthful and embodies through choice and self-sacrifice important and debated values (e.g., self-determination). He/she who is a hero escapes the catastrophic spiral of death. In this sense, the separations produced in MAiD and NDPC contexts may leave the bereaved person with different heroes that influence grieving journeys.

To Be Left with the Hero: Some participants are inhabited by beautiful images of death and the deceased. The latter continues to be with them despite his/her death. The hero who inhabits the bereaved individual by MAiD is the one who was courageous until the very end. It is a deceased who is strong in the face of death, even so strong that he/she has defied death or welcomed it willingly. In the imagination of the bereaved person, he/she is almost immortal perhaps, since he/she did not die in decay. The person dies remaining fully him/herself until the very end, liberated, inspiring and in complete control.

With ... what I take from that [crying] is the courage, the determination and choosing the moment when ... when she wanted to leave. She didn’t want to suffer, that’s what she always asked me. She wanted to choose herself, she was always a person who was, the control of everything. She wanted to be in control of that too. [...] It’s a beautiful memory. It’s a beautiful way to go. (Participant who lost her mother to MAiD)

In NDPC context, the deceased rather represents the beauty that never completely fades. The dying person, who has transformed and withered away, continues to experience moments when he/she becomes his/her true self again. The dying person pierces the clouds with his/her light until the very end. The moments when he sings and smiles do the family members good. They remind one participant that an end of life lived to the very end was worth it.

There were times when I was ... I was like no, like, it’s not worth it because like, he lost all his autonomy, he couldn’t ... he’s not happy and all that. But after that, in the moments when he was smiling or singing, it was like, okay no, I’m glad that [he’s still alive]. (Participant who lost her father to NDPC)

To Be Left by the Hero: Other participants seemed to feel rather left behind by the hero.

But that’s it, the exile, the survival um the ... the violence ... well maybe violence is too strong, but the ... the harshness of the state, that is, the ... I didn’t tell my friend, the one who referred me to the study, but I think it now, it’s that we’re left to ourselves. (Participant who lost his spouse to MAiD)

Some bereaved individuals in MAiD context tell us that the deceased is so beautiful and inspiring that the void he/she leaves behind is even greater. He/she was so in control, so fully him/herself up until the moment of death, that it is difficult to integrate the reality of the departure. Some participants report that their loved one was experiencing a surge of energy at the edge of MAiD. They described the absurdity of seeing them moving and smiling one moment, and dead the next. They elaborate on the difficulty of staying with an image of a somewhat abrupt departure.

Participants sometimes also have in mind the image of a tortured hero. To defend his/her right to receive MAiD, the dying person must be assessed, answer questions and justify him/herself. This process can be painful. One interviewee describes it as torture.

And in the end, he cried almost every time he was asked those questions [Why do you want to die?]. It was like torture. Because I’m talking about what I saw in my spouse: torture. Watching the other person being tortured, well you are also being tortured [crying]. (Participant who lost her spouse to MAiD)

In the context of NDPC, the imprints that seem to hurt the most are those that we associate with the impostor metaphor. The loved one is negatively transformed because of his/her illness. He/she becomes unrecognizable, and participants have to deal with the new person in front of them, when what they want most is to take care of their “real” loved one, not this impostor, this fallen hero.

And then she was running away [from the hospice]. She tried to take the elevator. We didn’t want to ... in any case there were a lot of ... it wasn’t easy. We saw her wanting so much ... it wasn’t her! It wasn’t her! We were so nice, and she was angry with us, and ... ouhh! [Interviewer: She didn’t have the same personality?] No, no. No, no, she didn’t. She was no longer the same person. [...] You know, because ... our last time with her, we would have liked to coddle her, to pamper her, but it was like ... not easy to do what she wanted. We often had to fight with her. (Participant who lost her daughter to NDPC)

The imprints described seem to do a lot of good in some cases, but can also be a source of distress. Both MAiD and NDPC cannot therefore be described as necessarily facilitating circumstances for bereavement. Rather, we paint a complex and open-ended picture based on the qualitative findings.

Integrated Results

First and foremost, combining the quantitative and qualitative results allows us to suggest that MAiD does not generally increase the risk of prolonged grief when compared to NDPC. However, our qualitative results indicate that there is a continuum of imprints ranging from painful to comforting. MAiD and NDPC therefore have the potential to foster difficult grief experiences, although this would not be generally the case. Beyond this main finding, the integration of the results sheds light on different dynamics with respect to (1) possible interaction and potentiation effects, (2) a certain volatility of imprints, and (3) acceptance of MAiD in Quebec.

Interaction and Potentiation Effects

In general, in both groups, the participants with the most “negative” or intense imprints are also among those with higher scores on the grief questionnaires. However, some interviewees describe negative imprints, but the effect of these imprints is not reflected in their questionnaire scores (scores that are low). The three interviewees with the most intense imprints and higher scores on the grief questionnaires all lost a spouse and above all a person to whom they were deeply attached. They also had an intense experience of caregiving over several years. On the other hand, one interviewee describing negative imprints, but scoring low on the questionnaires, lost her grandmother and had little caregiving experience. These results can be explained by the existence of interaction and/or potentiation phenomena between different factors that influence grief (e.g., the relationship with the deceased and the degree of involvement during the illness trajectory). Thus, the effect of the imprints created around MAiD and NDPC could be attenuated or on the contrary accentuated by other factors. Negative imprints can then be considered a risk factor, but its impact must be considered within a broad set of other risks and protective factors.

Imprints that Are not Ubiquitous

Some interviewees seemed to be “suffering” during their interview, or at least the recall of events, of negative imprints, made them more emotional and they reported a difficulty to talk about these events. Oddly, their scores on the grief questionnaires are (very) low when compared to the rest of the sample. It should be noted that very little time elapsed between the completion of the questionnaires and the interview for these participants. Yet, the difficulties experienced during the interview are not reflected in the quantitative results. We hypothesize that MAiD and NDPC’s imprints not only undergo interaction and potentiation effects, but are also not ever-present in the minds and daily lives of the bereaved individuals, who may focus on other things and may momentarily forget an imprint. Imprints are also not necessarily conscious, and their meanings evolve. In this regard, the interviews allowed us to observe that participants give new meanings to their experience by interacting with the interviewer and their social environment more generally. The imprints can thus be brought to consciousness or modified at different moments during bereavement.

Furthermore, it seems that several imprints can be experienced almost simultaneously by the same individual. The latter can alternate between positive and difficult imprints, and it can be tricky to determine which imprints predominate (and will predominate) in one’s experience. For example, for one interviewee, MAiD is an experience painted with paradoxes that are difficult to explain and tolerate.

That’s why it was unbearable. It seems like we have ... well, usually, an event gives you either a negative or a positive feeling, but here, it was really non-stop for 2 weeks. As much positive as negative, and as much well-being as ill-being. (Participant who lost his grandmother to MAiD)

A Socially Welcomed Assisted Death

Finally, both qualitative and quantitative results seem to indicate that the social stigma around MAiD may be less important in Quebec than elsewhere. The majority of individuals who completed the questionnaires perceive a supportive environment and society for MAiD. The interviewees did not report any difficulty in expressing themselves on the modality of death in their environment. Some even emphasized that others’ curiosity and openness to this phenomenon helped them in their grief. These results may be an indication that this practice is consistent with Quebecers’ values, at least for certain groups. However, there is a lack of religious, ethnic and cultural diversity in our sample which makes it necessary to temper this conclusion. We must also consider a possible sampling bias: perhaps individuals who perceive social stigma did not participate in the study due to fear of stigma.

Discussion

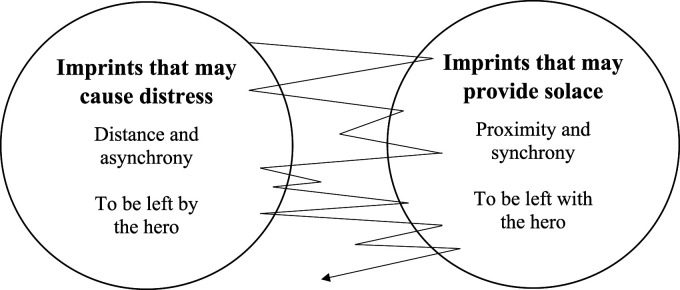

This study’s goal was to describe and compare grief experiences in MAiD and NDPC contexts. We have established that these two contexts do not generally favor prolonged grief. However, a deeper look at the specifics of grief in these circumstances reveals a much more nuanced reality for some individuals, echoing several researchers’ findings (Beuthin et al., 2021; Brown et al., 2020; Frolic et al., 2020; Gamondi et al., 2015, 2018; Hales et al., 2019; Schutt, 2020; Starks et al., 2007; Srinivasan, 2018; Wagner et al., 2011, 2012a, 2012b). Frolic et al. (2020) described the experience of MAiD for families as a set of conflicting, double-edged experiences that the bereaved individual must come to terms with. Schutt (2020) construes this experience as multiple voices coexisting and interacting inside the family caregiver, some of them incongruent and contradictory. Likewise, the imprints we have conceptualized allow for the phenomenon’s description on a continuum of experiences. The imprints’ shifting natures and the coexistence of both comforting and distressing imprints within the same individual speak particularly to the assumption that grief can be made up of tensions of various intensities to be coped with. Our participants could also be described as oscillating between different types of imprints, and this at very variable speeds and frequencies. In this sense, our results fit well with Stroebe and Schut’s dual-process model (2010), which organizes grief experiences into two orientations (loss and restoration) between which the bereaved individuals oscillate. Just as they oscillate between multiple aspects of their grief, the bereaved persons may also alternate between imprints related to death circumstances (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Grief Experiences in the Contexts of Medical Assistance in Dying and Natural Death with Palliative Care – Inspired by the Dual-Process Model of Stroebe & Schut (1999, 2010).

However, the interaction effects we posited and the volatile nature of some of the imprints make it necessary to put into perspective the impact of MAiD and NDPC on grief. The imprints’ effect would depend on many other factors (e.g., the attachment style) that may be more influential than death circumstances. At the very least, the weights of MAiD and NDPC in the grief experience need to be viewed with caution. Caution is also needed in considering the impact on grief of palliative care support for the dying. We have not directly tackled this issue in our results, but our consideration of NDPC as a “gold standard” requires reflection. Our interviewees described palliative care teams in sometimes very different ways. Some described palliative care environments as a warm bubble and a bridge to death. Others spoke of a team that “throws” you out into the world alone once death has occurred. For one participant, palliative care was a sterile space made up of people desensitized to death. Not all palliative care accompaniments can therefore be considered equivalent. We also noticed that for some participants, NDPC is limited in the well-being it can provide to the bereaved individuals. It cannot prevent all negative imprints from being formed. In some respects, MAiD becomes the solution in the face of palliative care’s limitations. NDPC seems to be colored by MAiD discourses: some participants referred to MAiD when palliative care failed to provide relief or to keep the dying person’s personality intact. Others praised a fully lived end of life, saying that MAiD would have deprived them of a gradual preparation for death experience. Dilemmas emerged, such as between continuous palliative sedation and MAiD (Koksvik et al., 2020). Our findings suggest that NDPC and MAiD are interconnected: they are being fashioned in response to, in opposition to, or sometimes even in synergy (Bernheim & Raus, 2017) with one another. For some, NDPC is still the “gold standard,” but for others, there might be a new ideal path (Cain & McCleskey, 2019). We do not die quite as we used to, and our grief is affected by new influences and choices.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this study is the first to directly compare grief experiences in MAiD and NDPC contexts using a mixed methodology. Our results are noteworthy for their nuanced and complex nature, suggesting that our sample was not solely made up of MAiD advocates or individual who had a very positive grief experience, a concern raised by several researchers (Andriessen et al., 2019; Gamondi et al., 2018; Holmes et al., 2018; Srinivasan, 2018; Swarte et al., 2003). Furthermore, the study is the first to consider the impact of MAiD’s option on death experience and grief in NDPC context. We bring to the forefront choices and dilemmas that can leave imprints on grief. The study finally allows us to see Quebec as a society that is rather favorable to MAiD (less stigmatizing), or at least perceived as such by some bereaved individuals.

However, our research is particularly limited quantitatively. The sample size is small and the questionnaires used are not validated in French. The questionnaires are also self-reported, which forces us to rely solely on individuals’ understanding of their own grief and questionnaires’ items. Furthermore, grief reactions are not fully quantifiable (Fasse et al., 2014). These instruments do not allow us to disentangle what belongs to a specific bereavement from other problems experienced in parallel or even other bereavements. The study’s qualitative component provides a richer account of grief experiences, but these results cannot be generalized directly. However, they do overlap with several themes reported in the scientific literature, which suggests that our findings are transferable to other populations. Both the qualitative and quantitative samples also lack sex and cultural diversity.

Practical Implications

Our results allow us to draw an empirical and theoretical portrait of bereavement in the context of MAiD and NDPC. They inform health care providers on issues to consider when supporting families and offer metaphors (e.g., the hero) for understanding and explaining grief reactions. Our data interpretation suggests that individuals bereaved by MAiD do not generally require more specialized services or more intensive aftercare than individuals bereaved in NDPC context. Rather, we encourage health professionals to identify potentially negative imprints and assess the risk of prolonged grief by considering a range of other factors. The non-omnipresent nature of imprints should lead those involved in bereavement support to be cautious: it seems possible to bring to others’ minds imprints that may cause suffering. Hence, discussing imprints should not be done unnecessarily, but with a therapeutic aim and in a sensitive manner.

Future Directions

Many studies, including this one, have been conducted on small samples that are not necessarily representative of the bereaved population by assisted death and NDPC. Quantitative studies with larger cohorts would allow for a much more consequential portrayal of the phenomenon. This portrayal would complement those provided by exploratory qualitative studies already published. Longitudinal designs are also needed to understand the evolution and intensity of the imprints left by MAiD and NDPC in the course of bereavement. There is also little data available on the particularities of these types of bereavements when experienced within non-Caucasian groups. Likewise, we know little about the grief experiences of individuals who did not attend MAiD (all of our interviewees attended the procedure). Research on the optimal level of information for families (talking about potential imprints) to facilitate the grieving process also seems necessary to help and not unwittingly harm. Lastly, certain new dilemmas’ impact (e.g., continuous palliative sedation vs. MAiD) would benefit from consideration, so as to better care for those who bear witness to death; deaths that are now negotiated, chosen, and to some extent created.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-ome-10.1177_00302228221085191 for To Lose a Loved One by Medical Assistance in Dying or by Natural Death with Palliative Care: A Mixed Methods Comparison of Grief Experiences Philippe Laperle, Marie Achille, and Deborah Ummel in OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying

Acknowledgments

A heartfelt thank you to all the study participants for your generous and inspirational testimonials. Special thanks to all the researchers and clinicians in our networks who have enriched the conceptualization of our results with their insights. Last but not least, thanks to Jeff Ferreri, Research Assistant, who helped transcribe the interviews, and Chloé Evans, who revised the English of this paper.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a scholarship from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (#270134).

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

Philippe Laperle https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9579-6248

References

- Andriessen K., Krysinska K., Dransart D. A. C., Dargis L., Mishara B. L. (2019). Grief after euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Crisis, 41(4), 255–272. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arteau J. (2019). Le recours à l’aide médicale à mourir au Québec: L’expérience occultée des proches. (Master’s thesis). https://corpus.ulaval.ca/jspui/handle/20.500.11794/34970 [Google Scholar]

- Aubin-Cantin C. (2020). Étude exploratoire de l’expérience de deuil des proches en contexte d’aide médicale à mourir au Québec. (Doctoral dissertation). https://savoirs.usherbrooke.ca/handle/11143/17884 [Google Scholar]

- Bernheim J. L., Raus K. (2017). Euthanasia embedded in palliative care. Responses to essentialistic criticisms of the Belgian model of integral end-of-life care. Journal of Medical Ethics, 43(8), 489–494. 10.1136/medethics-2016-103511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuthin R., Bruce A., Thompson M., Andersen A. E., Lundy S. (2021). Experiences of grief-bereavement after a medically assisted death in Canada: Bringing death to life. Death Studies. Advance online publication. 10.1080/07481187.2021.1876790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J., Goodridge D., Harrison A., Kemp J., Thorpe L., Weiler R. (2020). Care considerations in a patient- and family-centered medical assistance in dying program. Journal of Palliative Care. Article 825859720951661. 10.1177/0825859720951661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain C. L., McCleskey S. (2019). Expanded definitions of the ‘good death’? Race, ethnicity and medical aid in dying. Sociology of Health & Illness, 41(6), 1175–1191. 10.1111/1467-9566.12903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W., Clark V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fasse L., Sultan S., Flahault C. (2014). Le deuil, des signes à l’expérience. Réflexions sur la norme et le vécu de la personne endeuillée à l’heure de la classification du deuil compliqué. L’Évolution Psychiatrique, 79(2), 295–311. 10.1016/j.evopsy.2013.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frolic A. N., Swinton M., Murray L., Oliphant A. (2020). Double-edged MAiD death family legacy: A qualitative descriptive study. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. Advance online publication. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamondi C., Fusi-Schmidhauser T., Oriani A., Payne S., Preston N. (2019). Family members’ experiences of assisted dying: A systematic literature review with thematic synthesis. Palliative Medicine, 33(8), 1091–1105. 10.1177/0269216319857630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamondi C., Pott M., Forbes K., Payne S. (2015). Exploring the experiences of bereaved families involved in assisted suicide in Southern Switzerland: A qualitative study. Palliative Care, 5(2), 146–152. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamondi C., Pott M., Preston N., Payne S. (2018). Family caregivers’ reflections on experiences of assisted suicide in Switzerland: A qualitative interview study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 55(4), 1085–1094. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.12.482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzini L., Goy E. R., Dobscha S. K., Prigerson H. (2009). Mental health outcomes of family members of Oregonians who request physician aid in dying. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 38(6), 807–815. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Quebec . (2021, March 18). Loi concernant les soins de fin de vie; S-32.0001. http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/fr/showdoc/cs/S-32.0001 [Google Scholar]

- Hales B. M., Bean S., Isenberg-Grzeda E., Ford B., Selby D. (2019). Improving the medical assistance in dying (MAID) process: A qualitative study of family caregiver perspectives. Palliative & Supportive Care, 17(5), 590–595. 10.1017/S147895151900004X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi N., Amos E., Lokuge B. (2021). The quality of bereavement for caregivers of patients who died by medical assistance in dying at home and the factors impacting their experience: A qualitative study. Journal of Palliative Medicine. Advance online publication. 10.1089/jpm.2020.0654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes S., Wiebe E., Shaw J., Nuhn A., Just A., Kelly M. (2018). Exploring the experience of supporting a loved one through a medically assisted death in Canada. Canadian Family Physician, 64(9), 387–393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavalieratos D., Corbelli J., Zhang D., Dionne-Odom J. N., Ernecoff N. C., Hanmer J., et al. (2016). Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 316(20), 2104–2114. 10.1001/jama.2016.16840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimsma G. K., van Leeuwen E. (2007). The role of family in euthanasia decision making. HEC Forum, 19(4), 365–373. 10.1007/s10730-007-9048-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koksvik G. H., Richards N., Gerson S. M., Materstvedt L. J., Clark D. (2020). Medicalisation, suffering and control at the end of life: The interplay of deep continuous palliative sedation and assisted dying. Health. Article 1363459320976746. 10.1177/1363459320976746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski S. D., Bondmass M. D. (2008). Physiological and psychological symptoms of grief in widows. Research in Nursing & Health, 31(1), 23–30. 10.1002/nur.20228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristjanson L. J., Aoun S. (2004). Palliative care for families: Remembering the hidden patients. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49(6), 359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kustanti C. Y., Fang H.-F., Kang X. L., Chiou J.-F., Wu S.-C., Yunitri N., et al. (2021). The effectiveness of bereavement support for adult family caregivers in palliative care: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 53(2), 208–217. 10.1111/jnu.12630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev E., Munro B. H., McCorkle R. (1993). A shortened version of an instrument measuring bereavement. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 30(3), 213-226. 10.1016/0020-7489(93)90032-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowers J., Scardaville M., Hughes S., Preston N. J. (2020). Comparison of the experience of caregiving at end of life or in hastened death: A narrative synthesis review. BMC Palliative Care, 19(1), 154. 10.1186/s12904-020-00660-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon C. J., Smith N. G., Henry M., Milman E., Berish M., Farrace A., et al. (2016). A pilot study of meaning-based group counseling for bereavement. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 72(3), 210–233. 10.1177/0030222815575002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon C. J., Smith N. G., Henry M., Milman E., Chochinov H. M., Körner A., et al. (2015). Reconstructing meaning with others in loss: A feasibility pilot randomized controlled trial of a bereavement group. Death Studies, 39(7), 411–421. 10.1080/07481187.2014.958628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malterud K., Siersma V. D., Guassora A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. 10.1177/1049732315617444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namey E., Guest G., O’Regan A., Godwin C. L., Taylor J., Martinez A. (2020). How does mode of qualitative data collection affect data and cost? Findings from a quasi-experimental study. Field Methods, 32(1), 58–74. 10.1177/1525822X19886839 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pluye P., Bengoechea E. G., Granikov V., Kaur N., Tang D. L. (2018). Tout un monde de possibilités en méthodes mixtes: revue des combinaisons des stratégies utilisées pour intégrer les phases, résultats et données qualitatifs et quantitatifs en méthodes mixtes. In Bujold M., Hong Q. N., Ridde V., Bourque C. J., Dogba M. J., Vedel I., et al. (Eds.), Oser les défis des méthodes mixtes en sciences sociales et sciences de la santé (pp.28–48). ACFAS. [Google Scholar]

- Pohlkamp L., Kreicbergs U., Prigerson H. G., Sveen J. (2018). Psychometric properties of the prolonged grief disorder-13 (PG-13) in bereaved Swedish parents. Psychiatry Research, 267, 560-565. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson H. G., Horowitz M. J., Jacobs S. C., Parkes C. M., Aslan M., Goodkin K., et al. (2009). Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLOS Medicine, 6(8). Article e1000121. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards N., Krawczyk M. (2021). What is the cultural value of dying in an era of assisted dying? Medical Humanities, 47(1), 61–67. 10.1136/medhum-2018-011621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson T., Marwit S. J. (2006). An investigation of the relationship of personality, coping, and grief intensity among bereaved mothers. Death Studies, 30(7), 677–696. 10.1080/07481180600776093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutt K. C. H. (2020). Exploring how family members experience medical assistance in dying (MAiD). (Doctoral dissertation). https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/322800357.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Sealey M., Breen L. J., O’Connor M., Aoun S. M. (2015). A scoping review of bereavement risk assessment measures: Implications for palliative care. Palliative Medicine, 29(7), 577–589. 10.1177/0269216315576262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan E. G. (2018). Bereavement and the Oregon Death with Dignity Act: How does assisted death impact grief? Death Studies, 43(10), 647–655. 10.1080/07481187.2018.1511636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starks H., Back A. L., Pearlman R. A., Koenig B. A., Hsu C., Gordon J. R., et al. (2007). Family member involvement in hastened death. Death Studies, 31(2), 105–130. 10.1080/07481180601100483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M., Schut H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23(3), 197-224. 10.1080/074811899201046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M., Schut H. (2010). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: A decade on. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 61(4), 273–289. 10.2190/OM.61.4.b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M., Schut H., Stroebe W. (2007). Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet, 370(9603), 1960–1973. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarte N. B., Van Der Lee M. L., Van Der Bom J. G., Van Den Bout J., Heintz A. P. M. (2003). Effects of euthanasia on the bereaved family and friends: A cross sectional study. BMJ, 327(7408), 1–5. 10.1136/bmj.327.7408.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori A., Teddlie C. (2010). SAGE handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. (2016) Interpretive description: Qualitative research for applied practice (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tourret M. (2011). Qu’est-ce qu’un héros? Inflexions, 16(1), 95–103. 10.3917/infle.016.0095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Variath C., Peter E., Cranley L., Godkin D., Just D. (2020). Relational influences on experiences with assisted dying: A scoping review. Nursing Ethics, 27(7), 1501–1516. 10.1177/0969733020921493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner B., Boucsein V., Maercker A. (2011). The impact of forensic investigations following assisted suicide on post-traumatic stress disorder. Swiss Medical Weekly, 141(4142), 1–6. 10.4414/smw.2011.13284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner B., Keller V., Knaevelsrud C., Maercker A. (2012. a). Social acknowledgement as a predictor of post-traumatic stress and complicated grief after witnessing assisted suicide. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 58(4), 381–385. 10.1177/0020764011400791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner B., Müller J., Maercker A. (2012. b). Death by request in Switzerland: Posttraumatic stress disorder and complicated grief after witnessing assisted suicide. European Psychiatry, 27(7), 542–546. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild D., Grove A., Martin M., Eremenco S., McElroy S., Verjee-Lorenz A., et al. (2005). Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: Report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value in Health, 8(2), 94–104. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-ome-10.1177_00302228221085191 for To Lose a Loved One by Medical Assistance in Dying or by Natural Death with Palliative Care: A Mixed Methods Comparison of Grief Experiences Philippe Laperle, Marie Achille, and Deborah Ummel in OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying