Abstract

Our research group created a public communication strategy of expressive writing, to use within our research center over the Massachusetts COVID-19 stay at home advisories. Our goals were to 1) build community, 2) recognize the unique experiences, needs, concerns and coping strategies of our colleagues, and 3) create a mechanism to creatively share those experiences. We conceptualized a weekly e-newsletter, “Creativity in the Time of COVID-19,” a collective effort for expressing and documenting the extraordinary, lived experiences of our colleagues during this unique time of a coronavirus pandemic. Through 23 online issues, we have captured 72 colleagues’ perspectives on social isolation, the challenges of working from home, and hope in finding connection through virtual platforms. We have organized the themes of these submissions, in the forms of photos, essays, poetry, original artwork, and more, according to three components of the Social Connection Framework: structural, functional and quality approaches to creating social connectedness.

Work and home are one. Desks are in bedroom corners; prized kitchen table spaces are shared with children attending school. We no longer stretch our legs walking to meetings, sharing cheerful hellos and appreciative smiles as we pass our colleagues in the hallway. Now we try to create a sense of togetherness through videoconference calls, devoid of sitting shoulder to shoulder. Children and pets punctuate video meetings, coming in for snuggles or requests. These scenes delight our colleagues, who claim these are the highlights of their day. This is our new normal.

Massachusetts, where we work and live, was among the first states to experience the surge in cases of COVID-19 (Massachusetts Department of Public Health [MDPH], 2020). We have been working at home since March 10, 2020, when Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker declared a state of emergency. School districts abruptly closed. Colleges and universities began sending students home; they would not return for the rest of the semester, and many not for the next year. Our home wireless networks suddenly faced unending demand.

We are researchers at the Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research (CHOIR), one of 18 national Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Services Research and Development-funded Centers of Innovation. CHOIR, co-located in Bedford and Boston, Massachusetts, consists of 121 investigators, research staff and administrative personnel whose mission is to advance coordinated, patient-centered health care for all Veterans through research and quality improvement. We confront issues in our patient population that affect other safety net hospitals, but with one difference – the military and/or combat history of many of our patients. This translates into elevated rates of conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder, military sexual trauma, and mental health and substance use disorders. Thus, we are particularly attuned to how social circumstances affect health. Hearing directly from Veterans about their perceptions of health care access and quality is a hallmark of CHOIR research.

Our team (ARE, EMM, DKM, GMF) met virtually on March 11, 2020, to brainstorm how we would communicate with CHOIR during our time working from home. Because of our organization’s culture of learning from patients’ stories, we felt that our colleagues would be eager to share their stories and reflections on living and working through a pandemic. We decided to create a space for them to listen to each other, and an opportunity to share their experiences through expressive writing, considered a kind of therapy that uses the writing process to cope with and heal from emotional trauma (Pennebaker, 2018, 1997; Pennebaker & Smyth, 2016). Others recognized this too: the day before we met, Professor Nicholas Christakis, tweeted:

If I were a college president and were closing schools for a once-in-a-century reason, in order to help build campus community and curate a historical archive, I would set up a system so students could record their experiences, as a kind of individual and collective diary.

Our team discussed the communication strategies we hoped to use over the next several weeks (not realizing this might be months, and eventually an entire year). We took prior research and Christakis’ ideas to heart, and conceptualized a weekly e-newsletter, “Creativity in the Time of COVID-19,” a collective effort for expressing and documenting the extraordinary, lived experiences of our colleagues during this unique time. Our e-newsletter goals were to 1) create a connected community of colleagues, 2) recognize the unique needs, concerns and coping strategies of our colleagues, and 3) create a mechanism to creatively share experiences. Our Defining Moments essay aims to share our colleagues’ stories, highlighted in our newsletter. The themes that we identified from these narratives related to how our colleagues developed much-needed social connections during the pandemic.

On March 12, 2020, we emailed our colleagues to request contributions in the forms of short essays or stories, poetry, photos with captions, artwork, and other creative mediums (Figure 1). We set ground rules: submissions must be original, no clinical advice was to be given, newsletters would be made public to the wider research community so highly personal information was discouraged (employee support for personal or work issues were described in other e-mails), and submissions involving other people would require their permission. Our team consists of three editors who solicit and track submissions and take charge of developing and disseminating an issue on a rotating basis (ARE, DKM, GMF), and one communication strategist who creates the issue layout and manages public dissemination (EMM). A draft of the e-newsletter is sent to contributors for final approval prior to Center-wide and public dissemination.

Figure 1.

Call for submissions to Creativity in the Time of COVID-19.

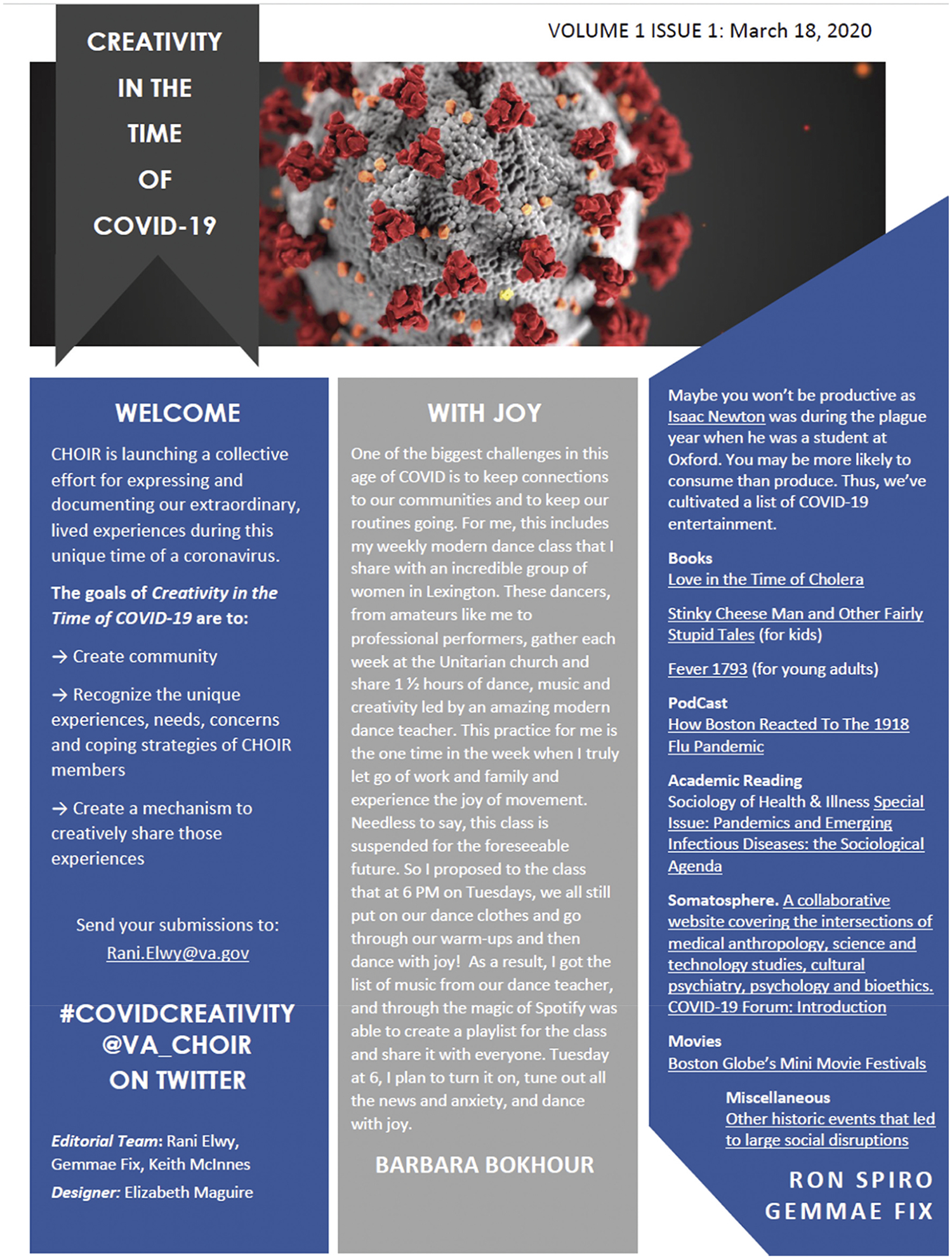

The response to Creativity in the Time of COVID-19 was tremendous; we received submissions from 72 colleagues, many contributing more than once. Our first issue was published just one week after the conception of our newsletter, on March 18, 2020 (Figure 2). We published 15 weekly issues between March 18 and June 24, 2020; when we realized the extended public health timeline of working from home, we amended our issue frequency to monthly for issues 16–23, starting in July 2020 and continuing through February 2021. We concluded our newsletter efforts on February 24, 2021, covering 12 months of our colleagues’ lived experiences and efforts to create social connection during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 2.

The first issue of creativity in the time of COVID-19, March 18, 2020.

Our 23 issues are dominated by photos with captions, poems, essays, original artwork and games. Many reflect our coworkers’ efforts to create social connection with others – family members and friends, both near and far, neighbors, and other colleagues. These submissions highlight tangible tools for creating connection, and also describe the quality of these relationships and why they are particularly important during a time of physical distancing. Below, we present topics from our submissions aligning with the Social Connection Framework, which describes the structural, functional and quality domains of social connection (Holt-Lundstadt et al., 2017). Structural connection involves the interconnections among differing ties and roles in social networks, including the number and size of social contacts, participation and active engagement in a variety of social activities and relationships, a sense of communality, and social contact frequency. Functional connection includes emotional, informational, tangible or belonging support, either received or perceived to be available when needed. Quality social connections exist when people report satisfaction and cohesion in their relationships, and ratings of conflict, distress or ambivalence in their relationships are low (Holt-Lundstadt et al., 2017). Our newsletter submissions also reveal how colleagues are actively fighting social disconnection, defined as social isolation, low social integration, loneliness and relationship distress (Holt-Lundstadt, 2015; Cornwell & Waite, 2009).

Creating structures to enhance social connection

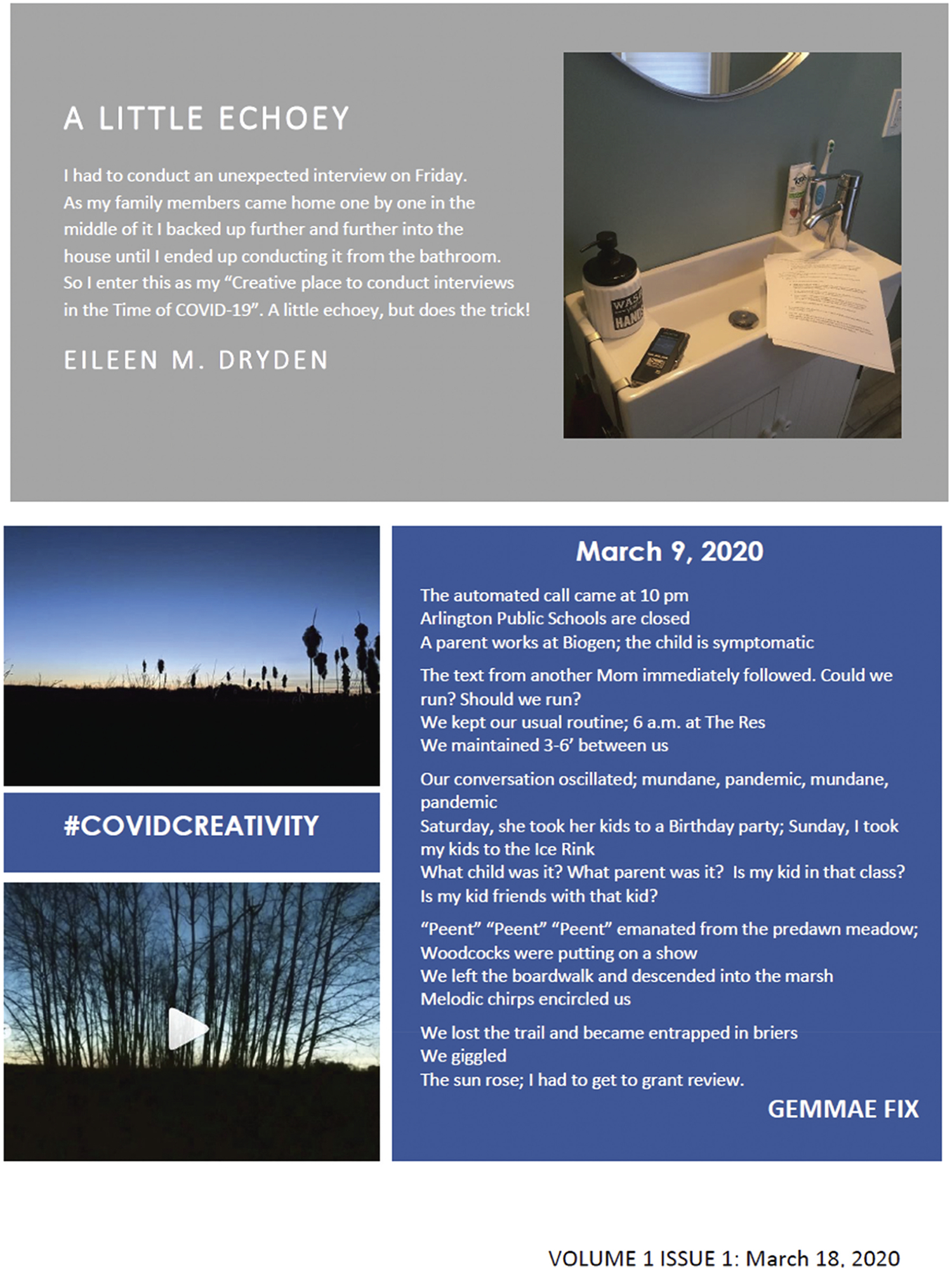

Colleagues had to quickly learn to work from home. This often consisted of designing new ways of working while attending to different social roles and responsibilities that exist at home, and creating new ways of conceptualizing the existence of colleagues while working remotely. One colleague shared a poem and photo about this challenge of working away from others (Figure 3):

Wake up in the morning to telework … still in my PJs

Practicing social isolation

Surrounded by boxes of …

unidentified surveys

Too quiet, but full on

concentration

Attempting not to get too … stir

crazy

Miss the people, the productivity &

predictable building mishaps at

CHOIR … What elevator fire?

Home is where the work is

For now

Be safe everyone

These times are just … wow.

Figure 3.

Creating structure for working from home.

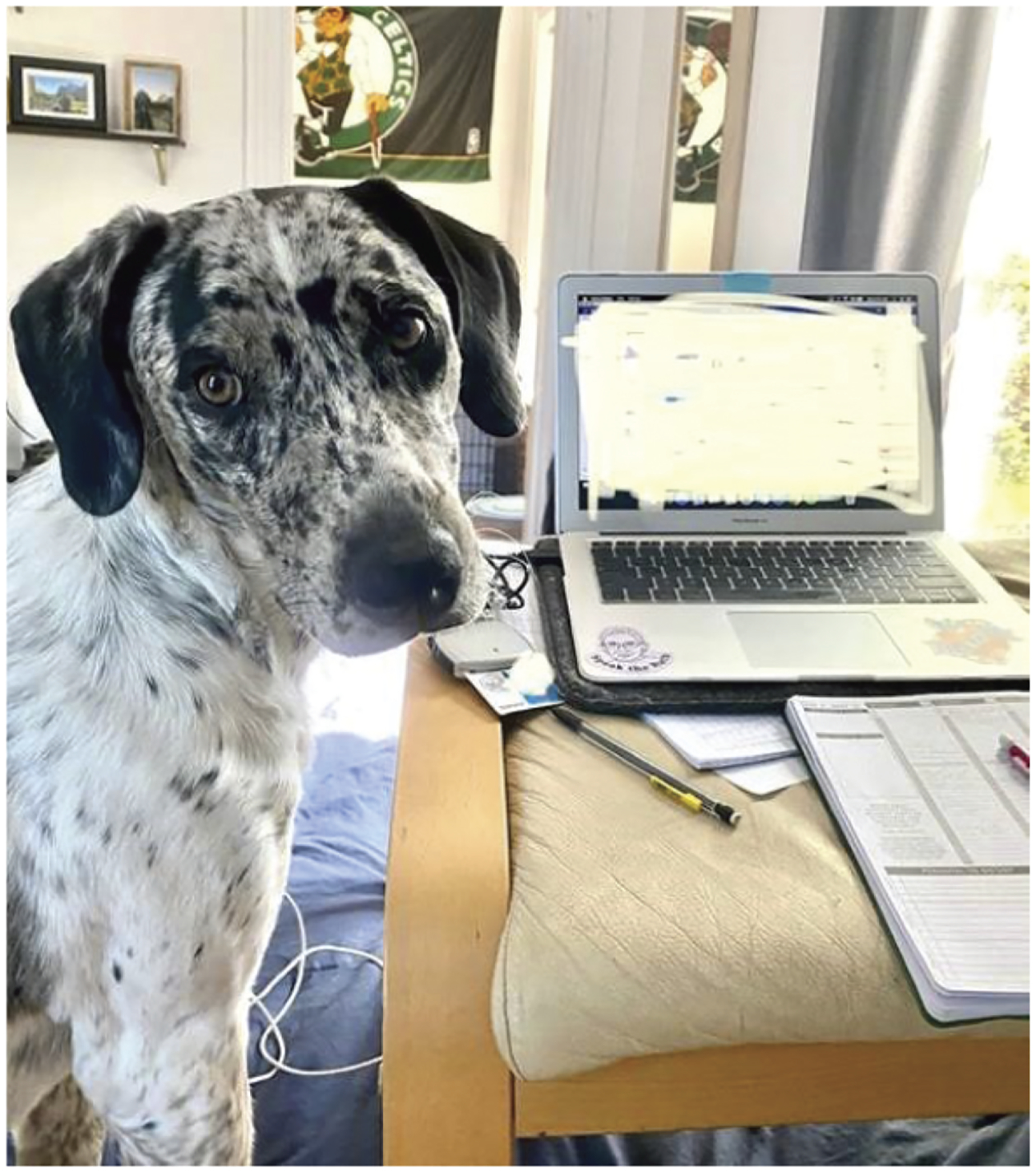

Others had to learn to share home spaces with other household members including pets, who helped with coping during the pandemic (Figure 4): “Here is a photo of my pup Koa, who is dedicated to helping me stay on task as I diligently reply to emails.”

Figure 4.

Creating structure for working at home.

For parents with young children at home, productivity often felt elusive. They sought help from other family members, sometimes even traveling to “pod,” or live together as a unit in isolation during the pandemic, to help them meet their work demands: “On the one hand, I have everything I need as I write at my in-law’s house in upstate New York. On the other hand, this view of Lake Canandaigua and my kids splashing with joy in the water is a bit distracting! Realistically, though, working from home with grandparents around has upped my productivity by a million.” Another colleague shared how she structures daily virtual connections with her research team:

Each day, I send my staff an email around noon, and I try to include a funny photo or poll question that everybody can participate in. Last week’s question was: ‘what was something you ate as a child that you would never eat now?’

Functions that provide social connection

Many colleagues provided emotional, tangible or belonging support to colleagues, friends, families and neighbors throughout the pandemic. Creating virtual game nights to connect family members across states served an important function for social and emotional connection. One colleague provided an example of how to create this critical function for others:

My family is far-flung, so we had a great family game night last weekend playing Yahtzee across 3 households. We used FaceTime with the people in a group chat list. Each household needs Yahtzee scoring sheets for each person and 5 dice. I really appreciated this way to enjoy time with my brother’s family, my parents, and my own family. We intend to keep doing this post-COVID to stay connected between visits.

Several colleagues used baking and cooking to provide a functional way to create social connection and belonging. One colleague shared (Figure 5): “I’m not able to see family this holiday season, so I’ve been learning how to perfect my grandmothers’ Thanksgiving and Christmas recipes. I’m proud of this cherry pie, which we serve with homemade whipped cream. The secret ingredient? Love … and lots of sugar.” Home improvements to create functional outdoor space for gathering were also shared in our newsletter (Figure 6): “I suspect like a lot of people, being home more of the time has motivated several home improvements, among them hanging these lights in our backyard.”

Figure 5.

Functions that provide social connection.

Figure 6.

Functions that provide social connection.

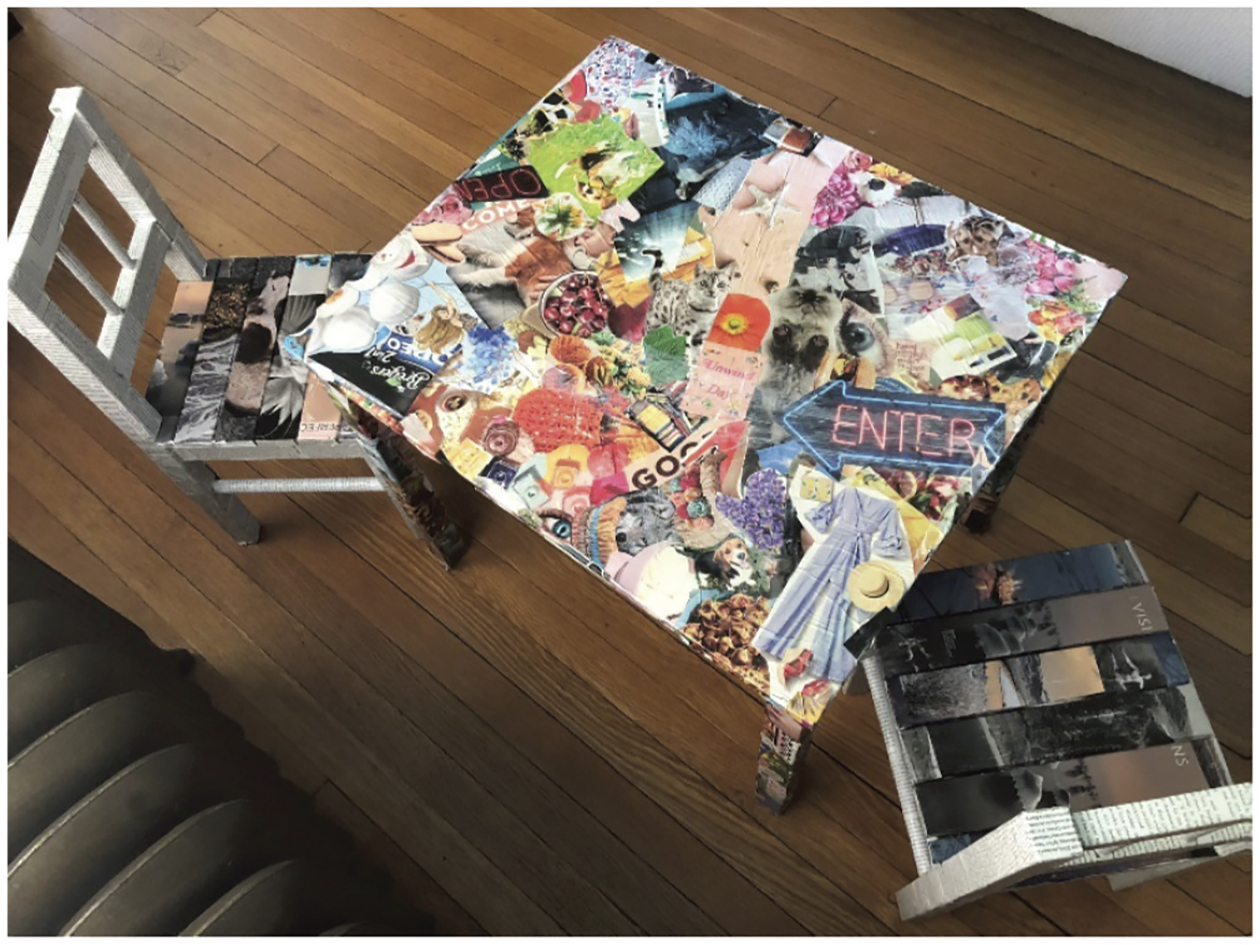

Colleagues described spending more family time on community service projects done at home. This helped increase social connection, through time together and tangible support for each other and community organizations (Figure 7):

Each year our town auctions off upcycled old chairs [for a benefit]. This year my daughters and I decided to decoupage an Ikea table and chair set they’ve long outgrown. We gathered magazine donations from all around town by posting on the town listserv, and then cut and Mod Podged pieces of paper to the lightly-sanded table and chairs.

Figure 7.

Functions that provide social connection.

Quality relationships increase social connection

Enjoying quality time outdoors with family, friends and neighbors is a frequent focus of several newsletter contributions. This highlights ways colleagues are seeking to increase the positive aspects of their social relationships. One colleague shared an essay of how she created connections to neighbors by venturing outdoors in the early stages of the pandemic:

On a typical March day in my neighborhood couples and dog-walkers stroll down the street, the occasional runner jogs by and children play in their yards. Lately this has shifted. Dogs are still walked and runners still run; but now, every afternoon, groupings of people are out walking together … I met a woman and her child who have lived down the street from me for years for the first time. We’re all likely feeling worried, confused, and uncertain as we as we grapple with a constant influx of information about COVID-19 and an ever-shifting reality. These group walks have the practical purpose of getting parents and kids out of the house after hours of home-schooling. For me they exemplify how we still find ways to “be” in the world and connect with our fellow humans, even during a time where we must separate and keep our distance from each other. As I look out my window at the passers-by, it inspires the feeling, even if only temporarily, that we’re in this together.

Similarly, another colleague wrote a poem to describe how kids on her street are now getting together more often than previously, as enjoying the outdoors is now one activity that all kids can enjoy together (Figure 8):

We’ve lived on this street for years,

It’s quiet, it’s dead, it’s sprinkled

with cars,

Each family contained in a

backyard.

But,

As confinement lingers, backyards

shrink,

releasing swarms on the street.

For the first time, kids meet

Fast friendships established

Every day, on bike, on foot,

on whatever comes afoot

Our street taken by storm

Dead end no more.

Figure 8.

Quality relationships increase social connection.

For some, artistic pursuits with family can also create a sense of community quality, thereby serving a social connection purpose. One colleague shared (Figure 9): “My kids have been painting some ‘kindness rocks’ to leave in places for other people to find. I wanted to get in on the fun, so I painted a mandala rock.”

Figure 9.

quality relationships increase social connection.

Newsletter dissemination

Each “Creativity in the Time of COVID-19” issue is located on CHOIR’s website (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2020), and is compliant with Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act (29 U.S.C. § 794d), as amended by the Workforce Investment Act of 1998 (P.L. 105–220), to be accessible to those with disabilities. Public dissemination through our Center’s Twitter account @VA_CHOIR is an important aspect of our research, and thus, our team decided to use this form of social media to share our pandemic communication efforts with other Centers of Innovation and organizations doing related work, using the hashtag #COVIDCreativity. This sharing proved useful. Colleagues from other VA Centers, who viewed our newsletter via Twitter, became contributors to the publication as well.

Once a week, and later, once a month, one of the editors emailed the newsletter to the entire Center. We delighted in the feedback we received in response: “Thank you! Loving each and every one of these pieces”; “Thanks for brightening up my day!”; “This brought a big smile to my face this Wednesday morning! Great way to start the day.” These statements confirm our belief that a regularly occurring, online newsletter of lived experiences during COVID-19 succeeded in keeping our research center connected during our time of telework. Additionally, one colleague stated in their submission, “Working from home is hard for me – I usually focus better in a separate space, and thrive on contact with coworkers.” Although our mission with Creativity in the Time of COVID-19 was to create a sense of community connection through creative expression and lived experiences during our time working from home, COVID-19 has illuminated the important function of social connection as a remedy to loneliness exacerbated by the need to physically distance.

On May 29, 2021, Massachusetts lifted all COVID-19 restrictions. COVID-19 cases continue to decline, mainly through heroic vaccination efforts. Our workplace expects employees to return to our building at least half-time by September 2021. Thus, our Creativity in the Time of COVID-19 newsletter has run its course. Its lessons of creating community building and social connection, we hope, will remain with our colleagues for many months to come.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. Our project was funded through VA Health Services Research and Development CIN 13-403. We thank the many members of the VA Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research for their submissions to Creativity in the Time of COVID-19. Our essay, and our newsletter, would not have been possible without their contributions. Permission has been granted from contributors for all quotes used from Creativity in the Time of COVID-19 submissions, as well as for the photos and contributions displayed in Figures 2–9.

Funding

The work was funded through VA Health Services Research and Development [CIN 13-403].

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Cornwell EY, & Waite LJ (2009). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation and health among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(1), 31–48. 10.1177/002214650905000103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lundstadt J (2015). The potential public health relevance of social isolation and loneliness: Prevalence, epidemiology, and risk factors. Public Policy and Aging Report, 27(4), 127–130. 10.1093/ppar/prx030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lundstadt J, Robles TF, & Sbarra DA (2017). Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. American Psychologist, 72(6), 517–530. 10.1037/amp0000103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases in MA as of March 30, 2020. Retrieved August 2, 2020, from https://www.mass.gov/doc/covid-19-cases-in-massachusetts-as-of-march-30-2020/download

- Pennebaker JW (1997). Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science, 8(3), 162–166. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00403x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW (2018). Expressive writing in psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(2), 226–229. 10.1177/1745691617707315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, & Smyth J (2016). Opening up by writing it down: The healing power of expressive writing. (3rd ed.). Guildford. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service, Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research. (2020). Retrieved November 3, 2020, from https://www.choir.research.va.gov/