Summary

Background

Results of the randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled Bangkok Tenofovir Study (BTS) showed that taking tenofovir daily as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) can reduce the risk of HIV infection by 49% in people who inject drugs. In an extension to the trial, participants were offered 1 year of open-label tenofovir. We aimed to examine the demographic characteristics, drug use, and risk behaviours associated with participants’ uptake of and adherence to PrEP.

Methods

In this observational, open-label extension of the BTS (NCT00119106), non-pregnant, non-breastfeeding, HIV-negative BTS participants, all of whom were current or previous injecting drug users at the time of enrolment in the BTS, were offered daily oral tenofovir (300 mg) for 1 year at 17 Bangkok Metropolitan Administration drug-treatment clinics. Participant demographics, drug use, and risk behaviours were assessed at baseline and every 3 months using an audio computer-assisted self-interview. HIV testing was done monthly and serum creatinine was assessed every 3 months. We used logistic regression to examine factors associated with the decision to take daily tenofovir as PrEP, the decision to return for at least one PrEP follow-up visit, and greater than 90% adherence to PrEP.

Findings

Between Aug 1, 2013, and Aug 31, 2014, 1348 (58%) of the 2306 surviving BTS participants returned to the clinics, 33 of whom were excluded because they had HIV (n=27) or grade 2–4 creatinine results (n=6). 798 (61%) of the 1315 eligible participants chose to start open-label PrEP and were followed up for a median of 335 days (IQR 0–364). 339 (42%) participants completed 12 months of follow-up; 220 (28%) did not return for any follow-up visits. Participants who were 30 years or older (odds ratio [OR] 1·8, 95% CI 1·4–2·2; p<0·0001), injected heroin (OR 1·5, 1·1–2·1; p=0·007), or had been in prison (OR 1·7, 1·3–2·1; p<0·0001) during the randomised trial were more likely to choose PrEP than were those without these characteristics. Participants who reported injecting heroin or being in prison during the 3 months before open-label enrolment were more likely to return for at least one open-label follow-up visit than those who did not report injecting heroin (OR 3·0, 95 % CI 1·3–7·3; p=0·01) or being in prison (OR 2·3, 1·4–3·7; p=0·0007). Participants who injected midazolam or were in prison during open-label follow-up were more likely to be greater than 90% adherent than were those who did not inject midazolam (OR 2·2, 95% CI 1·2–4·3; p=0·02) or were not in prison (OR 4·7, 3·1–7·2; p<0·0001). One participant tested positive for HIV, yielding an HIV incidence of 2·1 (95% CI 0·05–11·7) per 1000 person-years. No serious adverse events related to tenofovir use were reported.

Interpretation

More than 60% of returning, eligible BTS participants started PrEP, which indicates that a substantial proportion of PWID who are knowledgeable about PrEP might be interested in taking it. Participants who had injected heroin or been in prison were more likely to choose to take PrEP, suggesting that participants based their decision to take PrEP, at least in part, on their perceived risk of incident HIV infection.

Funding

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration.

Introduction

One in ten of the 2 million new HIV infections in 20141 was probably caused by injection drug use, and more than 80% of all HIV infections in some countries of eastern Europe and central Asia are related to drug use.2

The Bangkok Tenofovir Study (BTS) was a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) trial, assessed in people who inject drugs (PWID) in Bangkok during 2005–12.3 The trial showed that taking tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (tenofovir) daily can reduce the risk of HIV infection by 49% (95% CI 9·6–72·2) in PWID. On the basis of results of BTS,3 as well as PrEP trials in men who have sex with men4 and heterosexual men and women,5,6 the US Public Health Service,7 WHO,8 and the Thailand Ministry of Public Health9 have published guidelines for the use of PrEP to prevent HIV infections.

Following the publication of the BTS randomised trial results,3 and consistent with the study protocol, participants were offered 1 year of daily tenofovir for HIV PrEP, and were followed-up in an open-label extension to the trial. During the randomised, placebo-controlled trial, we told participants that we did not know whether they were taking tenofovir or placebo, and that even if they were taking tenofovir, we did not know whether it would prevent HIV infection. During the open-label follow-up, we told participants that tenofovir, if taken daily in combination with other HIV prevention strategies, could reduce their risk of HIV infection.

The objectives of this open-label extension to the trial were to examine demographic characteristics, drug use, and risk behaviours of BTS participants who chose to take daily open-label tenofovir to identify factors associated with the decision to take daily tenofovir as PrEP, the decision to return for at least one open-label PrEP follow-up visit, and greater than 90% adherence to open-label PrEP.

Methods

Study design and participants

The randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (BTS) and the observational, open-label 1-year extension were done in HIV-negative people who were aged 20–60 years at BTS enrolment and who had injected drugs in the year preceding BTS enrolment, at 17 Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) drug-treatment clinics in densely populated urban communities of Bangkok. At the end of the randomised BTS, study drug (placebo or tenofovir) was stopped while the data were analysed. Study staff attempted to contact BTS participants with information provided by participants at least once every 3 months after the randomised trial was completed to tell them about study progress, when results were expected, and to update contact information. After the publication of the BTS results in 2013,3 staff contacted participants and asked them to return to the clinic to hear about the results and to be told whether they had received tenofovir or placebo during the trial. All non-pregnant, non-breastfeeding, HIV-uninfected BTS participants who did not have grade 2, 3, or 4 creatinine results during the randomised trial were offered daily oral tenofovir (300 mg) for 1 year, free of charge, at the 17 BMA drug-treatment clinics. Tenofovir was also provided to imprisoned participants within prisons. Study staff met with officials from the Thailand Department of Correction before initiation of the randomised trial and open-label extension to discuss the study and request permission and assistance to offer imprisoned participants the study drug during the randomised trial and daily tenofovir during the open-label extension. Study staff worked with prison medical staff to identify a private space in the prison medical clinic for participants to complete study activities. At study visits during the open-label extension staff asked participants whether they would like to continue to receive PrEP or to stop. Participants took tenofovir in the clinics or the prisons; tenofovir was not given to participants to take at home.

Ethical review committees of the BMA and the Thailand Ministry of Public Health and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Institutional Review Board approved the BTS protocol, including the open-label extension. Volunteers meeting all eligibility criteria could enrol after providing written informed consent.

Procedures

At open-label enrolment and monthly visits (we defined months as 28 days) over a period of up to 1 year, we assessed participants for adverse events, provided individualised adherence and risk-reduction counselling, tested participants’ oral fluid for HIV antibodies (OraSure Technologies Inc, Bethlehem, PA, USA), and female participants had urine pregnancy tests (ULTI Med Products, Ahrensburg, Germany). Participants signed a tenofovir adherence diary on the days that they came to the clinic to take tenofovir; clinic staff marked the days that participants did not return. These data were used to assess adherence and follow-up. Participants completed a risk behaviour assessment of injection drug use, sexual activity, and incarceration in an audio computer-assisted self-interview, every 3 months. We tested participant blood samples for HIV (enzyme-immunoassay [EIA], Bio-Rad Laboratories, Redmond, WA, USA), and kidney and liver function every 3 months. Participants received 350 baht (about US$9·20) compensation for their time and travel at the 3 month visits. Participants with reactive HIV test results discontinued tenofovir, and infection was confirmed with EIA and western blot (Bio-Rad). Newly infected individuals were referred for care according to national guidelines.9

Statistical analyses

We used logistic regression to determine whether participant demographic characteristics, drug use, or risk behaviours reported during the randomised trial were associated with the decision to take daily tenofovir as PrEP during the open-label extension, whether risks during the 3 months before the PrEP open-label enrolment visit were associated with returning for at least one PrEP open-label follow-up visit, and whether risks reported during PrEP open-label follow-up were associated with greater than 90% adherence.10 Variables with a p value of less than 0·15 in the bivariable analysis were assessed in a multivariable model. We assessed the fit of the logistic models with the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. We defined adherence as the number of days, recorded in the tenofovir adherence diary, that the participant took tenofovir divided by the number of days that the participant was followed up, expressed as a percentage. We chose 90% adherence because data from PrEP trials suggest a high level of adherence is associated with protection from HIV infection.3,4,6,11,12 HIV incidence and exact 95% Poisson CIs were calculated per 1000 person-years of HIV-negative observation. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to assess the association between adherence to study drug in the randomised trial and adherence to tenofovir in the open-label follow-up.10 We used generalised estimating equations logistic regression to model trends in participant reports of injecting drugs, sharing needles, incarceration, and sexual activity.13

We used SAS version 9.3 for statistical analyses. The BTS is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT0011910G.

Role of the funding source

Staff from the CDC participated in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Follow-up of BTS participants in the randomised trial was completed on June 8, 2012, and trial results were announced on June 13, 2013. From Aug 1, 2013, to Aug 31, 2014, 1348 (58%) of the 230G surviving BTS participants returned to the clinics to discuss BTS results with staff and decided whether or not to take daily tenofovir as HIV PrEP in the open-label extension. Participants who returned were older (526 [51%] of 1033 aged <30 years vs 822 [60%] of 1380 aged ≥30 years; p<0·0001), more likely to have injected drugs (723 [52%] of 1399 who did not inject vs 625 [62%] of 1014 who injected; p<0·0001), and more likely to have been imprisoned (699 [49%] of 1420 who were not imprisoned vs G49 [G5%] of 993 who were imprisoned; p<0·0001) during the randomised trial than were participants who did not return. Of the 1348 participants who returned, 27 (2%) had tested positive for HIV and six (<1%) had grade 2, 3, or 4 creatinine results during the randomised trial and were not eligible for the open-label tenofovir extension. Of the 1315 eligible BTS participants, 798 (61%) chose to start taking open-label tenofovir. The median age of participants who started PrEP in the open-label extension was 39 years (IQR 35–47) and 640 (80%) were men. In multivariable analysis, older participants (odds ratio [OR] 1·8; 95% CI 1·4–2·2), those who had injected heroin during the randomised trial, and those who had been in prison during the randomised trial were more likely to choose PrEP than those who did not share these characteristics (table 1).

Table 1:

Logistic regression analysis of behaviours during the BTS as predictors of starting open-label tenofovir in the extension study, in all participants eligible for the extension study

| Total (N=1315) | Chose to take tenofovir (n=798)* | Bivariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | |||

| General characteristics | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 274 | 158 (58%) | 1 | ・・ | ・・ | ・・ |

| Male | 1041 | 640 (61%) | 1・2 (0・9–1・5) | 0・25 | Not included | NA |

| Age at BTS enrolment | ||||||

| 20–29 years | 509 | 269 (53%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| 30–59 years | 806 | 529 (66%) | 1・7 (1・4–2・1) | <0・0001 | 1・8 (1・4–2・2) | <0・0001 |

| Education | ||||||

| ≤grade 6 | 648 | 401 (62%) | 1 | ・・ | ・・ | ・・ |

| >grade 6 | 667 | 397 (60%) | 0・9 (0・7–1・1) | 0・38 | Not included | NA |

| Behaviours during the BTS | ||||||

| Injected any drugs | ||||||

| No | 711 | 399 (56%) | 1 | ・・ | ・・ | ・・ |

| Yes | 604 | 399 (66%) | 1・5 (1・2–1・9) | 0・0002 | Not included† | NA |

| Injected heroin | ||||||

| No | 990 | 570 (58%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Yes | 325 | 228 (70%) | 1・7 (1・3–2・3) | <0・0001 | 1・5 (1・1–2・1) | 0・007 |

| Injected methamphetamine | ||||||

| No | 924 | 539 (58%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Yes | 391 | 259 (66%) | 1・4 (1・1–1・8) | 0・007 | 1・1 (0・8–1・4) | 0・72 |

| Injected midazolam | ||||||

| No | 970 | 583 (60%) | 1 | ・・ | ・・ | ・・ |

| Yes | 345 | 215 (62%) | 1・1 (0・9–1・4) | 0・47 | Not included | NA |

| Shared needles | ||||||

| No | 1140 | 677 (59%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Yes | 175 | 121 (69%) | 1・5 (1・1–2・2) | 0・01 | 1・0 (0・7–1・6) | 0・83 |

| In prison | ||||||

| No | 684 | 375 (55%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Yes | 631 | 423 (67%) | 1・7 (1・3–2・1) | <0・0001 | 1・7 (1・3–2・1) | <0・0001 |

| Sex with a casual partner | ||||||

| No | 452 | 259 (57%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Yes | 863 | 539 (62%) | 1・2 (1・0–1・6) | 0・07 | 1・2 (0・9–1・5) | 0・16 |

BTS=Bangkok Tenofovir Study. NA=not applicable.

Proportions in this column are out of the denominator listed in the Total column.

Not included in the multivariable analysis because it correlated closely with the injection of heroin, methamphetamine, or midazolam.

Of the 798 BTS participants who chose to start open-label PrEP, five (1%) tested positive for HIV and were referred for care. On the basis of the date of the final HIV test in the randomised trial, HIV incidence was estimated to be 3·6 (95% CI 1·2–8·3) per 1000 person-years in the 798 participants re-tested for HIV at the start of open-label extension.

The 793 HIV-negative BTS participants who chose to start open-label tenofovir were followed up for a median of 335 days (IQR 0–364). 220 (28%) participants did not return for any of the follow-up visits. In the multivariable analysis, participants who reported injecting heroin or being in prison during the 3 months before open-label enrolment were more likely to return for at least one follow-up visit than those who did not report injecting heroin or being in prison (table 2).

Table 2:

Logistic regression analysis of behaviours during the 3 months before enrolment in the open-label extension study as predictors of returning for at least one follow-up visit, in HIV-negative participants who chose to start open-label tenofovir

| Total | Returned for at least one visit (n=573)* | Bivariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | |||

| General characteristics (N=793) | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 156 | 108 (69%) | 1 | ・・ | ・・ | ・・ |

| Male | 637 | 465 (73%) | 1・2 (0・8–1・8) | 0・35 | Not included | NA |

| Age at BTS enrolment | ||||||

| 20–29 years | 267 | 184 (69%) | 1 | ・・ | 1・0 | ・・ |

| 30–59 years | 526 | 389 (74%) | 1・3 (0・9–1・8) | 0・13 | 1・3 (0・9–1・8) | 0・18 |

| Education | ||||||

| ≤grade 6 | 397 | 286 (72%) | 1 | ・・・・・・ | ||

| >grade 6 | 396 | 287 (72%) | 1・0 (0・8–1・4) | 0・89 | Not included | NA |

| Behaviours during the 3 months before open-label enrolment (N=780) † | ||||||

| Injected any drugs | ||||||

| No | 627 | 439 (70%) | 1 | ・・ | ・・ | ・・ |

| Yes | 153 | 125 (82%) | 1・9 (1・2–3・0) | 0・004 | Not included‡ | NA |

| Injected heroin | ||||||

| No | 718 | 509 (71%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Yes | 62 | 55 (89%) | 3・2 (1・5–7・2) | 0・003 | 3・0 (1・3–7・3) | 0・01 |

| Injected methamphetamine | ||||||

| No | 733 | 524 (71%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Yes | 47 | 40 (85%) | 2・3 (1・0–5・2) | 0・04 | 1・7 (0・7–4・0) | 0・24 |

| Injected midazolam | ||||||

| No | 689 | 491 (71%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Yes | 91 | 73 (80%) | 1・6 (1・0–2・8) | 0・07 | 1・0 (0・6–1・9) | 0・93 |

| Shared needles | ||||||

| No | 764 | 549 (72%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Yes | 16 | 15 (94%) | 5・9 (0・8–44・7) | 0・05 | 3・2 (0・4–25・6) | 0・27 |

| In prison | ||||||

| No | 636 | 444 (70%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Yes | 144 | 120 (83%) | 2・2 (1・4–3・5) | 0・001 | 2・3 (1・4–3・7) | 0・0007 |

| Sex with a casual partner | ||||||

| No | 616 | 449 (73%) | 1 | ・・ | ・・ | ・・ |

| Yes | 164 | 115 (70%) | 0・9 (0・6–1・3) | 0・48 | Not included | NA |

BTS=Bangkok Tenofovir Study. NA=not applicable.

Returned for at least one of 13 follow-up visits during the open-label extension; proportions in this column are out of the denominator listed in the Total column.

Behaviour data missing for 13 participants.

Not included in the multivariable analysis because it correlated closely with the injection of heroin, methamphetamine, or midazolam.

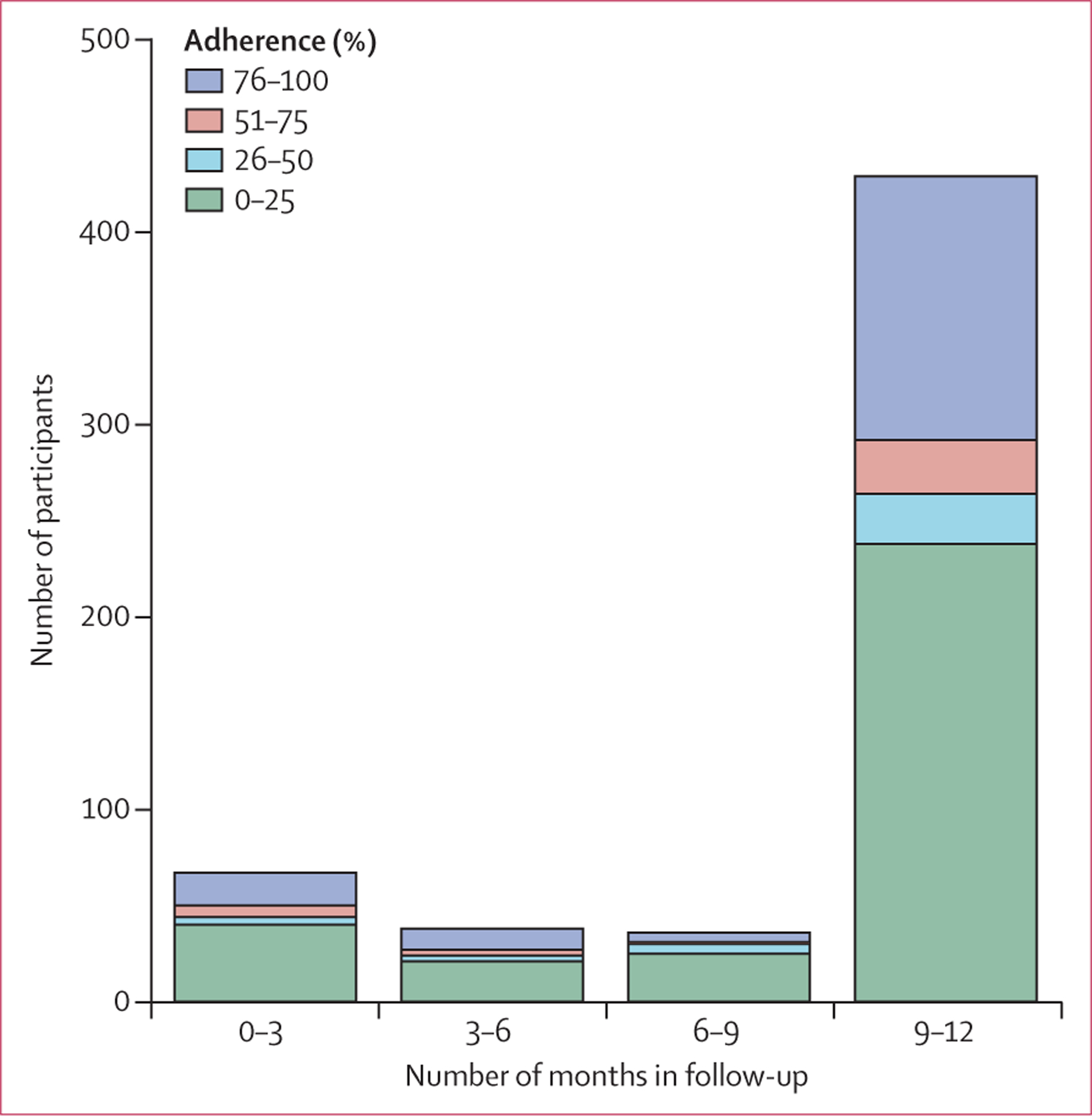

The 573 participants who returned for at least one open-label follow-up visit contributed 474 person-years of follow-up; 67 (12%) completed 3 months of follow-up, 38 (7%) completed 3–6 months, 37 (6%) completed 6–9 months, and 431 (75%) completed 9–12 months (figure). Adherence data from three participants was missing. On the basis of adherence diaries of the remaining 570 participants, participants took tenofovir for a mean of 38·5% (SD 41·3) of the days that they were followed up. 267 (47%) of 570 participants took tenofovir for 10% or less of the days in follow-up, and 143 (25%) took tenofovir for greater than 90% of the days in follow-up; these two groups accounted for 72% (410 of 570) of the participants in follow-up who returned for at least one visit. In the multivariable analysis, tenofovir adherence on more than 90% of the days in follow-up was more likely in male versus female participants, those who injected midazolam versus those who did not, and those who had been (or were) in prison versus those who had (or were) not (table 3). Participants who reported sex with a casual partner were less likely to take tenofovir on more than 90% of follow-up days than those who did not report sex with casual partners (table 3). We did not find a correlation between adherence to study drug during the randomised trial and adherence to tenofovir during the open-label follow-up (Spearman correlation coefficient r=0·03; data not shown).

Figure: Length of follow-up in participants in the open-label extension of the Bangkok Tenofovir Study who returned for at least one visit (n=570)*, according to adherence to open-label tenofovir.

Adherence is number of days participant took open-label tenfovir divided by number of days participant was followed up. *Excludes three patients for whom adherence data were missing.

Table 3:

Logistic regression analysis of behaviours during open-label extension as predictors of >90% adherence to open-label tenofovir, in participants who returned for at least one open-label follow-up visit

| Total | (N=573) | Adherence >90% (n=143)* |

Bivariable analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | |||

| General characteristics | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 108 | 15 (14%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Male | 465 | 128 (28%) | 2・4 (1・3–4・2) | 0・003 | 1・9 (1・0–3・6) | 0・04 |

| Age at BTS enrolment | ||||||

| 20–29 years | 184 | 46 (25%) | 1 | ・・ | ・・ | ・・ |

| 30–59 years | 389 | 97 (25%) | 1・0 (0・7–1・5) | 0・99 | Not included | NA |

| Education | ||||||

| <grade 6 | 286 | 64 (22%) | 1 | ・・ | ・・ | ・・ |

| >grade 6 | 287 | 79 (28%) | 1・3 (0・9–1・9) | 0・16 | Not included NA | |

| Behaviours during open-label extension | ||||||

| Injected any drugs | ||||||

| No | 422 | 104 (25%) | 1 | ・・ | ・・ | ・・ |

| Yes | 151 | 39 (26%) | 1・1 (0・7–1・6) | 0・77 | Not included† | NA |

| Injected heroin | ||||||

| No | 491 | 117 (24%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Yes | 82 | 26 (32%) | 1・5 (0・9–2・5) | 0・13 | 1・2 (0・6–2・5) | 0・56 |

| Injected methamphetamine | ||||||

| No | 514 | 133 (26%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Yes | 59 | 10 (17%) | 0・6 (0・3–1・2) | 0・13 | 0・5 (0・2–1・0) | 0・06 |

| Injected midazolam | ||||||

| No | 480 | 112 (23%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Yes | 93 | 31 (33%) | 1・6 (1・0–2・7) | 0・04 | 2・2 (1・2–4・3) | 0・02 |

| Shared needles | ||||||

| No | 543 | 137 (25%) | 1 | ・・ | ・・ | ・・ |

| Yes | 30 | 6 (20%) | 0・7 (0・3–1・9) | 0.52 | Not included | NA |

| In prison | ||||||

| No | 417 | 70 (17%) | 1 | ・・・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Yes | 156 | 73 (47%) | 4・4 (2・9–6・5) | <0・0001 | 4・7 (3・1–7・2) | <0・0001 |

| Sex with a casual partner | ||||||

| No | 401 | 116 (29%) | 1 | ・・ | 1 | ・・ |

| Yes | 172 | 27 (16%) | 0・5 (0・3–0・7) | 0・0008 | 0・5 (0・3–0・8) | 0・002 |

BTS=Bangkok Tenofovir Study. NA=not applicable.

Proportions in this column are out of the denominator listed in the Total column.

Not included in the multivariable analysis because it correlated closely with the injection of heroin, methamphetamine, or midazolam.

Drug use and risk behaviour data were available for 780 (98%) of the 793 HIV-negative participants who chose to start open-label tenofovir, 153 (20%) of whom reported injecting drugs during the 3 months before open-label extension enrolment (91 [59%] injected midazolam, 62 [41%] injected heroin, and 47 [31%] injected methamphetamine); 16 (10%) of these 153 participants reported sharing needles. Of the 339 participants (43%) who completed the 12 month open-label visit, the number of participants injecting drugs and sharing needles did not change significantly during follow-up (table 4). The proportion of participants who were incarcerated (ie, in jail or in prison) during follow-up significantly declined, as did the proportion who injected methamphetamine, and the proportion reporting sexual activity with more than one sexual partner or sex with a casual partner (table 4).

Table 4:

Behaviours reported by participants in the open-label extension of the Bangkok Tenofovir Study, in participants who completed the 12-month open-label visit

| Open-label extension study visit |

p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolment (n=336) | Month 3 (n=290) | Month 6 (n=287) | Month 9 (n=286) | Month 12 (n=339) | ||

| Injected drugs in previous 3 months | ||||||

| Injected drugs | 78 (23%) | 64 (22%) | 62 (22%) | 64 (22%) | 68 (20%) | 0・16 |

| Shared needles | 7 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 3 (1%) | 8 (2%) | 0・79 |

| Injected daily | 24 (7%) | 22 (8%) | 20 (7%) | 21 (7%) | 27 (8%) | 0・67 |

| Drugs injected in previous 3 months | ||||||

| Heroin | 34 (10%) | 25 (9%) | 28 (10%) | 34 (12%) | 33 (10%) | 0・51 |

| Methamphetamine | 24 (7%) | 15 (5%) | 19 (7%) | 13 (5%) | 15 (4%) | 0・03 |

| Midazolam | 49 (15%) | 34 (12%) | 34 (12%) | 39 (14%) | 37 (11%) | 0・10 |

| Incarceration in previous 3 months | ||||||

| In jail | 60 (18%) | 33 (11%) | 26 (9%) | 22 (8%) | 20 (6%) | <0・0001 |

| In prison | 70 (21%) | 54 (19%) | 41 (14%) | 50 (17%) | 40 (12%) | <0・0001 |

| Sexual activity in previous 3 months | ||||||

| More than one sexual partner | 35 (10%) | 26 (9%) | 20 (7%) | 21 (7%) | 19 (6%) | 0・006 |

| Sex with casual partner | 67 (20%) | 40 (14%) | 42 (15%) | 35 (12%) | 43 (13%) | 0・002 |

| Men reporting sex with male partner | 5/274 (2%) | 2/241 (1%) | 3/238 (1%) | 2/237 (1%) | 3/276 (1%) | 0・57 |

Months were defi ned as 28 days.

One participant tested positive for HIV (at the 4 month visit) during open-label follow-up, yielding an HIV incidence of 2·1 (95% CI 0·05–11·7) per 1000 person-years among the 793 participants. The participant took tenofovir for 30 (23%) of 129 days that they were followed up and had not taken tenofovir during the G0 days before the reactive HIV test.

Six participants died during the open-label extension study: three from respiratory and circulatory failure, one from drug overdose, one from a femoral artery haemorrhage, and one from a skull fracture caused by an assault. Eleven participants were admitted to hospital: four for gastrointestinal issues, two for drug-use related causes, and one each for assault-related injuries, cataract replacement, fatigue, a hernia, and an infection. No serious adverse events related to tenofovir use were reported, and there were no reports of renal or hepatic injury or grade 3 or 4 creatinine results.

Discussion

We offered daily tenofovir as PrEP to participants of the randomised, placebo-controlled BTS3 at drug-treatment clinics and prisons for 1 year after the trial was completed. 798 BTS participants, 35% of all surviving participants and 61% of those who returned and were eligible, chose to start taking daily PrEP. Older participants and participants who had injected heroin or been in prison during BTS were more likely to choose to take PrEP than were younger participants or those who did not report heroin use or incarceration in prison. Similarly, participants who reported injecting heroin or had been in prison during the 3 months before open-label enrolment were more likely to return for at least one open-label follow-up visit than those who did not report heroin use or incarceration in prison. Both injecting drugs and incarceration have been associated with HIV infection in PWID in Bangkok,14–16 suggesting that participants based their decision to take or not take PrEP, at least in part, on their perceived risk of incident HIV infection. Of participants who returned for at least one follow-up visit, 25% were more than 90% adherent to PrEP.

Participants who returned for at least one follow-up visit who reported injecting midazolam during open-label follow-up were more likely to be greater than 90% adherent than those who did not inject midazolam. Why people who injected midazolam would be more adherent than those who did not is unclear. Participants who injected midazolam in the BTS were not more likely to become infected with HIV than those who did not,15 but they were more likely to die.17 Perhaps participants recognised their risk-taking behaviours and chose to take PrEP to prevent HIV infection. Participants who were imprisoned during open-label follow-up were more likely to be more than 90% adherent than those who were not imprisoned. These participants might have perceived themselves to be at risk of HIV and decided to take daily PrEP. Additionally, tenofovir was made available in prison clinics, easing access, which might have encouraged adherence.

Participants who reported sex with casual partners were less adherent than those who did not report casual sex. Reporting sex with a live-in or a casual partner was not associated with HIV infection during the randomised trial,15 and a previous study in PWID in the same clinics as those used in the BTS found that participants who reported having sex were less likely to become HIV infected than those who did not have sex.14 Participants who reported casual sex might have perceived their risk of HIV infection as low; however, PrEP reduces sexual HIV transmission4–6 and HIV prevention counselling to inform PWID of sexual HIV risks, in addition to injecting and needle sharing risks, might be useful.

Overall, daily adherence to tenofovir in this open-label extension of the BTS, even in the 570 participants who returned for at least one follow-up visit and for whom we had adherence data, was low (participants took tenofovir an average of 38·5% of the days that they were followed up) and lower than that observed in the randomised trial that preceded it (ie, based on study drug diaries, participants took the study drug [either tenofovir or placebo] an average of 83·8% of days in the randomised trial). This difference in adherence might be related to compensation that participants received for study visits: participants received 70 baht (US$2) for each day they came to clinic and 350 baht (US$10) for each monthly visit in the randomised trial, and only 350 baht for each 3-monthly visit in the open-label follow-up. Adherence might also have been related to participants’ self-assessed risk of HIV infection. Reports of injecting and sharing needles declined substantially during the randomised trial; 63% of participants reported injecting drugs during the 3 months before enrolment in the randomised trial compared with 17·5% at the end of the study (month 72); 18% reported sharing needles at enrolment compared with 1% at month 72·15 In BTS participants who chose to take tenofovir in the open-label extension (who completed the 12-month open-label visit), reports of injecting drugs and sharing needles did not increase during follow-up; the proportion who were injecting drugs (ranging from 20% at month 12 to 23% at enrolment) and sharing needles (ranging from <1% at month 6 to 2% at month 12) was similar to the proportion injecting and sharing at the end of the randomised trial (ie, at 72 months).15 Of the 570 participants who returned for at least one follow-up visit, the 267 (47%) participants who took tenofovir on 10% or less of the days that they were followed up might have correctly determined that they were not at risk of HIV infection, and the 160 (28%) participants who took daily tenofovir on 11–90% of the days they they were followed up might have opted to stop taking tenofovir during periods when they were not at risk for HIV infection.

One participant who opted to take tenofovir in this open-label extension became infected with HIV, yielding an HIV incidence of 2·1 (95% CI 0·05–11·7) per 1000 person-years, similar to the incidence in tenofovir recipients during the randomised trial (3·5 per 1000 person-years).3 The participant who became infected had not taken a dose of tenofovir for 2 months before testing positive for HIV. An open-label extension study that included participants from the iPrEx study, a PrEP trial in men who have sex with men, also found a low HIV incidence in adherent participants: 5·6 (95% CI 0·0–25·0) per 1000 person-years if drug concentrations were consistent with use of two to three tablets a week, and 0·0 (95% CI 0·0–6·1) per 1000 person-years with four or more tablets per week.18

This study has several limitations. Our assessment of factors associated with PrEP use was limited to factors included in the BTS risk behaviour questionnaire. A more detailed assessment of factors motivating PrEP use and adherence would require additional research. Participants might have under-reported stigmatised and illegal behaviours such as injecting drugs.19 However, the illegality and stigma associated with these activities did not change during follow-up, so rates of under-reporting should have remained constant. Participants were followed up in drug-treatment clinics and prisons and were required to come to the clinics if they wanted to receive tenofovir; a supply of tenofivir was not given to the participants to take home. Adherence might differ if other distribution methods are used. Adherence might also differ if more or less compensation is provided.

Four large randomised, placebo-controlled trials have shown that a daily dose of tenofovir or tenofovir–emtricitabine (ie, HIV PrEP) can reduce sexual and parenteral HIV transmission,3–6 and reports suggest that interest in and use of PrEP might be increasing.20,21 Adherence is a key factor for PrEP effectiveness.12,22 These trials, and our experience with this open-label extension study in PWID, highlight the need for tools to help people using PrEP achieve effective levels of adherence.23–25 Additional work is also needed to understand the appropriate place for PrEP in a package of services to reduce HIV transmission and other harms in PWID.26–28

In this observational, open-label follow-up to a randomised trial, we offered daily oral HIV PrEP with tenofovir to PWID in drug-treatment clinics and prisons in Bangkok. Although overall adherence was low, 25% of participants who returned for at least one open-label follow-up visit were more than 90% adherent and 59% returned for the 12-month visit. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention7 and WHO8 recommend PrEP for people at substantial risk of acquiring HIV. Our results suggest that PWID can assess their risk of HIV infection and appropriately decide whether or not to take PrEP. PrEP should be offered to people who inject drugs as an important part of an HIV prevention package.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

On May 1, 2016, we searched PubMed for studies assessing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in people who inject drugs (PWID). We used the search terms “pre-exposure prophylaxis HIV” and “people who inject drugs”. We did not apply any language restrictions. The Bangkok Tenofovir Study report was the only randomised clinical trial published and we did not find any open-label or implementation science PrEP studies in PWID. The Bangkok Tenofovir Study, a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in PWID during 2005–12, showed that taking tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (tenofovir) daily can reduce the risk of HIV infection by 49%.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, this is the first assessment of the open-label use of HIV PrEP in PWID. More than 60% of eligible participants who returned to the clinics to discuss the trial results chose to start open-label PrEP. Participants who had injected heroin or been in prison were more likely to choose to take PrEP than those who had not, suggesting that participants based their decision, at least in part, on their perceived risk of incident HIV infection. No HIV infections occurred in participants adherent to daily tenofovir.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our results suggest that PWID can assess their risk of HIV infection and appropriately decide whether or not to take PrEP. PrEP should be offered to PWID as an important part of an HIV prevention package.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants, doctors, nurses, counsellors, social workers, research nurses, and staff of the 17 Bangkok Metropolitan Administration drug-treatment clinics who made this work possible. The findings and conclusions in this Article are our own and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Bangkok Tenofovir Study Group

Principal investigator: Kachit Choopanya. Advisory group: Sompob Snidvongs Na Ayudhya, Sithisat Chiamwongpaet, Kraichack Kaewnil, Praphan Kitisin, Malinee Kukavejworakit, Manoj Leethochawalit, Pitinan Natrujirote, Saengchai Simakajorn, Wonchat Subhachaturas. Study clinic coordination team: Suphak Vanichseni (lead), Boonrawd Prasittipol, Udomsak Sangkum, Pravan Suntharasamai. Bangkok Metropolitan Administration: Rapeepan Anekvorapong, Chanchai Khoomphong, Surin Koocharoenprasit, Parnrudee Manomaipiboon, Siriwat Manotham, Pirapong Saicheua, Piyathida Smutraprapoot, Sravudthi Sonthikaew, La-Ong Srisuwanvilai, Samart Tanariyakul, Montira Thongsari, Wantanee Wattana, Kovit Yongvanitjit. Thailand Ministry of Public Health: Sumet Angwandee, Somyot Kittimunkong. Thailand Ministry of Public Health–US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Collaboration: Wichuda Aueaksorn, Baranee Balmongkol, Benjamaporn Chaipung, Nartlada Chantharojwong, Thanyanan Chaowanachan, Thitima Cherdtrakulkiat, Wannee Chonwattana, Rutt Chuachoowong, Marcel Curlin, Pitthaya Disprayoon, Kanjana Kamkong, Chonticha Kittinunvorakoon, Wanna Leelawiwat, Robert Linkins, Michael Martin, Janet McNicholl, Philip Mock, Supawadee Na-Pompet, Tanarak Plipat, Anchala Sa-nguansat, Panurassamee Sittidech, Pairote Tararut, Rungtiva Thongtew, Dararat Worrajittanon, Chariya Utenpitak, Anchalee Warapornmongkholkul, Punneeporn Wasinrapee. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Jennifer Brannon, Monique Baseer, Roman Gvetadze, Lisa Harper, Lynn Paxton, Charles Rose. Johns Hopkins University: Craig Hendrix, Mark Marzinke.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

We declare that we have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Michael Martin, Thailand Ministry of Public Health–US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Collaboration, Nonthaburi, Thailand; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Suphak Vanichseni, Bangkok Tenofovir Study Group, Taksin Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand.

Pravan Suntharasamai, Bangkok Tenofovir Study Group, Taksin Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand.

Udomsak Sangkum, Bangkok Tenofovir Study Group, Taksin Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand.

Philip A Mock, Thailand Ministry of Public Health–US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Collaboration, Nonthaburi, Thailand.

Benjamaporn Chaipung, Thailand Ministry of Public Health–US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Collaboration, Nonthaburi, Thailand.

Dararat Worrajittanon, Thailand Ministry of Public Health–US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Collaboration, Nonthaburi, Thailand.

Manoj Leethochawalit, Bangkok Metropolitan Administration, Bangkok, Thailand.

Sithisat Chiamwongpaet, Bangkok Metropolitan Administration, Bangkok, Thailand.

Somyot Kittimunkong, Department of Disease Control, Thailand Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand.

Roman J Gvetadze, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Janet M McNicholl, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Lynn A Paxton, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Marcel E Curlin, Thailand Ministry of Public Health–US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Collaboration, Nonthaburi, Thailand; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA; Division of Infectious Diseases, Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland, OR, USA.

Timothy H Holtz, Thailand Ministry of Public Health–US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Collaboration, Nonthaburi, Thailand; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Taraz Samandari, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Kachit Choopanya, Bangkok Tenofovir Study Group, Taksin Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand.

References

- 1.Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS. AIDSinfo: world overview. http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/datatools/aidsinfo/ (accessed May 5, 2016).

- 2.WHO. HIV/AIDS: people who inject drugs. http://www.who.int/hiv/topics/idu/en/ (accessed May 5, 2016).

- 3.Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. , for the Bangkok Tenofovir Study Group. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013; 381: 2083–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 2587–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 423–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2014: a clinical practice guideline. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/prepguidelines2014.pdf (accessed May 5, 2016).

- 8.WHO. Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/earlyrelease-arv/en/ (accessed May 5, 2016). [PubMed]

- 9.Thailand Ministry of Public Health. Thailand national guidelines on HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention 2014. Nonthaburi: Thailand Ministry of Public Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armitage P, Berry G, Matthews JNS. Statistical methods in medical research, 4th edn. New York: Blackwell Science, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haberer JE, Baeten JM, Campbell J, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention: a substudy cohort within a clinical trial of serodiscordant couples in East Africa. PLoS Med 2013; 10: e1001511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4: 151ra25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diggle PJ, Liang K, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin M, Vanichseni S, Suntharasamai P, et al. Drug use and the risk of HIV infection amongst injection drug users participating in an HIV vaccine trial in Bangkok, 1999–2003. Int J Drug Policy 2010; 21: 296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin M, Vanichseni S, Suntharasamai P, et al. Risk behaviours and risk factors for HIV infection among participants in the Bangkok Tenofovir Study, an HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis trial among people who inject drugs. PLoS One 2014; 9: e92809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suntharasamai P, Martin M, Vanichseni S, et al. Factors associated with incarceration and incident human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among injection drug users participating in an HIV vaccine trial in Bangkok, Thailand, 1999–2003. Addiction 2009; 104: 235–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanichseni S, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. High mortality among non-HIV-infected people who inject drugs in Bangkok, Thailand, 2005–2012. Am J Public Health 2015; 105: 1136–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14: 820–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konings E, Bantebya G, Carael M, Bagenda D, Mertens T. Validating population surveys for the measurement of HIV/STD prevention indicators. AIDS 1995; 9: 375–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laufer FN, O’Connell DA, Feldman I, Zucker HA. Vital signs: increased medicaid prescriptions for preexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection—New York, 2012–15. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64: 129G–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, et al. No new HIV infections with increasing use of HIV preexposure prophylaxis in a clinical practice setting. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61: 1601–03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin M, Vanichseni S, Suntharasamai P, et al. The impact of adherence to preexposure prophylaxis on the risk of HIV infection among people who inject drugs. AIDS 2015; 29: 819–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcus JL, Buisker T, Horvath T, et al. Helping our patients take HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): a systematic review of adherence interventions. HIV Med 2014; 15: 385–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet 2010; 376: 1838–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pop-Eleches C, Thirumurthy H, Habyarimana JP, et al. Mobile phone technologies improve adherence to antiretroviral treatment in a resource-limited setting: a randomized controlled trial of text message reminders. AIDS 2011; 25: 825–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Escudero D, Kerr T, Wood E, et al. Acceptability of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among people who inject drugs (PWID) in a Canadian setting. AIDS Behav 2015; 19: 752–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eisingerich AB, Wheelock A, Gomez GB, Garnett GP, Dybul MR, Piot PK. Attitudes and acceptance of oral and parenteral HIV preexposure prophylaxis among potential user groups: a multinational study. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e28238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guise A, Albers ER, Strathdee SA. ‘PrEP is not ready for our community, and our community is not ready for PrEP’: pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV for people who inject drugs and limits to the HIV prevention response. Addiction 2016; published online June 8. DOI: 10.1111/add.13437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]