Abstract

Public health agencies’ ability to protect health in the wake of COVID-19 largely depends on public trust. In February 2022 we conducted a first-of-its-kind nationally representative survey of 4,208 US adults to learn the public’s reported reasons for trust in federal, state, and local public health agencies. Among respondents who expressed a “great deal” of trust, that trust was not related primarily to agencies’ ability to control the spread of COVID-19 but, rather, to beliefs that those agencies made clear, science-based recommendations and provided protective resources. Scientific expertise was a more commonly reported reason for “a great deal” of trust at the federal level, whereas perceptions of hard work, compassionate policy, and direct services were emphasized more at the state and local levels. Although trust in public health agencies was not especially high, few respondents indicated that they had no trust. Lower trust was related primarily to respondents’ beliefs that health recommendations were politically influenced and inconsistent. The least trusting respondents also endorsed concerns about private-sector influence and excessive restrictions and had low trust in government overall. Our findings suggest the need to support a robust federal, state, and local public health communications infrastructure; ensure agencies’ authority to make science-based recommendations; and develop strategies for engaging different segments of the public.

As federal, state, and local public health agencies aim to protect and promote the public’s health in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond, their ability to succeed largely depends on the public’s trust. This entails the public believing that these agencies provide accurate information and are well intentioned.1 Such trust is central to the public’s willingness to listen to information and to adopt protective measures that limit disease transmission and mitigate negative health impacts.2–7 However, public trust in government and other major institutions across US society has been declining for decades, and the pandemic has raised concerns about trust in public health agencies in particular.8–10 Opportunities for misinformation to take root in the current social and traditional media environments raise concerns that trust will decline further.11,12

Most research on public trust during COVID-19 has focused either on tracking levels of trust in government entities over time or on individual, demographic predictors of trust.2,5,13 However, an underexamined, yet critical, area to explore is the reasons that people have higher and lower levels of trust. Without better understanding of these reasons, it is difficult to mobilize support for needed response policies or to develop strategies that help foster trust. Moreover, the vast majority of inquiry into trust focuses on federal institutions, with hardly any information about trust in public health agencies at the state or local level.14 Understanding reasons for trust and lack of trust across all levels of government would advance important dialogue about policy and communication approaches that can help public health leaders grow trust and bolster against declines during extended waves of COVID-19 and future crises.

The purpose of this study was to examine public trust in federal, state, and local public health agencies during the COVID-19 pandemic. We sought to examine how much US adults trust public health agencies and other sources of information for health recommendations; what major reasons those who trust these agencies a great deal report having for their trust, specifically for information about the COVID-19 outbreak; and among those with lower trust in these agencies, what major reasons they report for their lack of trust. Given that some segments of the US public are more entrenched in their views than others are, we analyzed reasons according to degree of trust so that results can guide tailored approaches for addressing trust in each segment.

Study Data And Methods

STUDY POPULATION AND SURVEY DESIGN

Data used in this study came from a cross-sectional, nationally representative, online and telephone survey we conducted in February 2022 among 4,208 US adults ages eighteen and older. The survey was designed and analyzed by researchers at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health (Boston, Massachusetts), in collaboration with staff at the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (Arlington, Virginia) and the National Public Health Information Coalition (Canton, Georgia). The study was determined to be exempt by the Institutional Review Board of the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

DATA COLLECTION

Data were collected during February 1–22, 2022, by SSRS (Glen Mills, Pennsylvania). Adults were contacted through two nationally representative, high-quality, probability-based web panels: the SSRS Opinion Panel and the Ipsos KnowledgePanel. Panel members were recruited by mail, using address-based sampling, and by random-digit dialing. Most respondents completed the survey online; 222 interviews were completed by telephone among adults who do not regularly use the internet, to ensure a fully representative sample. Surveys were administered in English and Spanish, according to respondents’ preferences. Among adults invited to participate, 44 percent completed the survey.

SURVEY INSTRUMENT AND MEASURES

The questionnaire was developed using American Association of Public Opinion Research best practices for survey research.15 The content and wording of questions, response options, and flow were developed after reviews of prior surveys16–18 and with input from public health department staff. The questionnaire was reviewed for bias, balance, and comprehension, and it was pretested in telephone interviews to improve clarity. Pretests included open-ended questions to articulate key concepts, including reasons for higher and lower trust levels.

The survey instrument included questions examining three areas analyzed in this study (see the online appendix for full question wording).19 First, we asked about the degree to which respondents trusted different groups for health recommendations. All respondents were asked about trust in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), their state public health department, and their local public health department, as well as trust in ten additional groups. To provide information about a wide range of groups while minimizing respondent fatigue, the additional ten groups were selected randomly from a list of fourteen other groups. Trust was measured on a four-point Likert scale (“a great deal,” “somewhat,” “not very much,” or “not at all”).

For subsequent questions, each respondent was randomly assigned to one of three tracks focused on a single agency: the CDC, their state public health department, or their local public health department. Those on each track were asked how much they trusted that agency to provide accurate information about the COVID-19 outbreak specifically. We then asked a follow-up question among those trusting “a great deal” about their reasons for high levels of trust. They were asked whether each of ten potential reasons was a major reason, minor reason, or not a reason at all that they trusted the agency a great deal. Again, to reduce respondent fatigue while assessing a wide range of possible reasons, participants were each asked about a random set of ten from among fourteen possible reasons.

We also asked a follow-up question among those who trusted their assigned agency less than a great deal (somewhat, not very much, or not at all) about the reasons for their lower levels of trust. They were asked whether each of ten potential reasons was a major reason, a minor reason, or not a reason at all for their lower trust. Reasons asked about among those who trusted a great deal and among those who were less trusting were drawn from the literature about which considerations were most likely to motivate or detract from trust in institutions broadly, and were therefore not necessarily parallel.

The perspective of those who answered at the top end of the trust scale (a great deal) was examined separately from the perspective of those in all other groups because the single category of “a great deal” has been shown to better predict behaviors such as vaccination than other response combinations (that is, when combined with those who trusted somewhat).5,20–22 Therefore, this allowed us to ask even those who trusted somewhat why they lacked greater trust. Understanding their reasoning may provide insights needed to adapt tailored approaches for encouraging protective behaviors among this group, instead of assuming that they trusted enough to adopt recommended behaviors consistently.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The sample was weighted through a multistage design to account for recruitment methods into the panels and related differential probabilities of selection. Data also were weighted by sex, race and ethnicity, education, age, nativity, metropolitan status, internet access, census region, and civic engagement, using population parameters drawn from several Census Bureau sources: the 2021 Current Population Survey, the 2020 Planning Database, the 2019 American Community Survey, and the 2017 Current Population Survey Volunteering and Civic Life Supplement. After weighting, there was less than a 1-percentage-point difference between the survey sample and national sources for all demographic characteristics (see appendix sections B and C).19

After calculating univariate estimates for responses, we calculated estimates for reported reasons for higher or lower trust among each group with higher or lower trust in federal, state, or local public health agencies. Using Stata, version 15.0, we examined differences between lower-trusting groups (for example, those who trusted somewhat and those who trusted not very much) in the percentages citing each reason, using two-tailed t-tests. All analyses used weighted data. Statistically significant differences below the 0.05 level are shown in exhibits, although only differences that were also at least 10 percentage points were deemed to have practical implications for policy or communications and are therefore considered as such in the text.23

LIMITATIONS

Notable limitations in this study include those common in probability-based surveys. First, it had a cross-sectional design rather than an experimental design, which means that causal interpretation is limited. Second, there is the risk for nonresponse bias beyond what could be addressed with multistage weighting. Third, there were limitations related to the use of self-reported data. Results did not address reasons for trusting agencies beyond those recognized by respondents, although in actuality, other factors may have been at play. There is also the risk for social desirability bias. To reduce this risk, respondents were not informed about public health agencies’ involvement in the survey. In addition, assessed reasons for trusting a great deal and reasons for not having a great deal of trust were not fully parallel. This reflects past work suggesting that the reasons for gaining trust and losing trust are not identical, as well as the practical need to keep the survey short; however, it limited comparisons across the whole population, and statistical comparisons were made only between subsegments that were less trusting (trust somewhat versus not very much versus not at all). Finally, we did not analyze political affiliation because its relationship with trust has been well studied elsewhere.3,9,13

Study Results

RATING TRUST IN SOURCES OF HEALTH INFORMATION

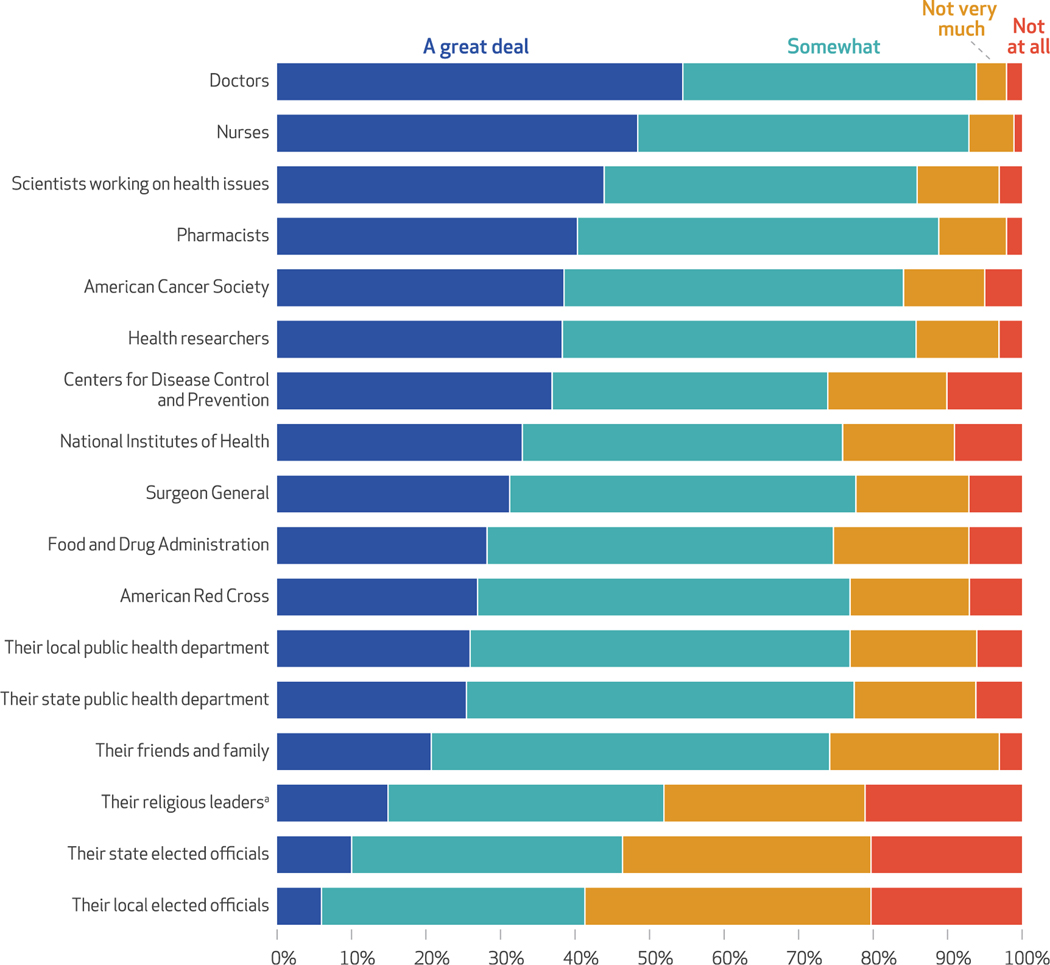

When it comes to trust in different sources of information for health recommendations, doctors and nurses received the highest ratings, with about half of the public saying that they trusted them a great deal (54 percent and 48 percent, respectively) (exhibit 1). Other health professionals, such as scientists working on health issues and pharmacists, also received high ratings, with about four in ten adults saying that they trusted them a great deal (44 percent and 40 percent, respectively). National and federal institutions had the next-highest levels of trust, with a third or more of the public saying that they trusted each of them a great deal: the American Cancer Society (39 percent), the CDC (37 percent), and the National Institutes of Health (33 percent). About a quarter of the public said that they trusted their local and state public health departments a great deal (26 percent and 25 percent, respectively), whereas state and local elected officials and religious leaders were among the least trusted groups. In addition, all sources had a sizable fraction of the public saying that they trusted them somewhat and very low percentages saying that they trusted them not very much or not at all. See appendix exhibit A2 for detailed percentages.19

EXHIBIT 1. Public trust in sources of health information among US adults, by degree of trust, 2022.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from a February 2022 nationally representative online and telephone survey of 4,208 US adults. NOTES Weighted percentages are displayed. Survey question: “In terms of recommendations made to improve health in general, how much do you trust the recommendations of each of the following groups? A great deal, somewhat, not very much, or not at all?” All respondents were asked about trust in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and in their state and local health departments. In addition, respondents were asked about trust in 10 additional groups, selected randomly from a list of 14 (n = 2,026–2,168). Appendix exhibit A2 presents a detailed version of exhibit 1 containing the percentage values (see note 19 in text). an = 1,606, excluding respondents who reported that religious leaders are not relevant to them.

REPORTED REASONS FOR TRUST IN PUBLIC HEALTH AGENCIES

When it comes to providing accurate information about the COVID-19 outbreak, public trust in the CDC and state and local health departments was similar to or slightly higher than public trust in these organizations for general health recommendations (see appendix exhibit A3).19 About fourin tenadults (42 percent) reported a great deal of trust in the CDC, and about a third said the same for their state (31 percent) or local (34 percent) public health department.

Among adults with high trust in the CDC (trusted them a great deal), top reported reasons for this trust included those related to scientific expertise, such as the idea that they followed scientifically valid research (94 percent) and have the experts (92 percent) (exhibit 2). In addition, more than three-quarters endorsed the CDC’s actions of having made vaccines and testing widely available (83 percent), as well as agreeing that they have given clear recommendations for people to protect themselves (79 percent). Further, more than two-thirds of respondents cited other communications-related reasons, including the idea that the information from the CDC matched other trusted sources (71 percent), the CDC provided detailed information (70 percent), and the CDC provided information frequently (68 percent).

EXHIBIT 2.

Major reasons for trust in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and state and local public health departments to provide accurate information about COVID-19, among US adults with high trust, 2022

| Public health departments |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Major reasons for trust | CDC (n = 418–452) | State (n = 339–357) | Local (n = 345–372) |

| Followed scientifically valid research | 94%b,c | 87% | 85% |

| Have the experts | 92b,c | 75 | 67 |

| Made vaccines and testing widely available | 83 | 86 | 88 |

| Have given clear recommendations for people to protect themselves | 79 | 81 | 87a |

| Information matched other sources I trust | 71 | 80a | 82a |

| Provided detailed information | 70 | 64 | 63 |

| Provided information frequently | 68 | 67 | 68 |

| Staff worked hard under difficult circumstances | 65 | 73a | 79a |

| Seemed to care about people | 64 | 69 | 73a |

| Steered clear of private-sector influence | 56 | 54 | 51 |

| Steered clear of a lot of politics | 56 | 50 | 54 |

| Provided good care at public health clinics | 49 | 58a | 71a,b |

| Have done a good job at controlling COVID-19 spread | 49 | 53 | 55 |

| I trust the government generally | 24 | 34a | 29 |

SOURCEA uthors’ analysis of data from a February 2022 nationally representative online and telephone survey of 4,208 US adults. NOTES Weighted percentages are displayed, and items are rank-ordered according to major reasons for trust in the CDC. Survey question: “What are the reasons you trust [entity] a great deal to provide accurate information about the COVID-19 outbreak? Are each of the following a major reason, a minor reason, or not a reason at all that you trust them a great deal for accurate information?” Results are shown for adults who reported trusting each agency “a great deal” to provide accurate information about COVID-19, who were asked to select their major reasons for trust from a randomly selected list of 10 reasons (among 14 total reasons). Sample sizes for each agency are shown as ranges because of variation in the number of respondents asked each reason due to randomization.

Percentage is significantly greater than for the CDC (p < 0:05).

Percentage is significantly greater than for the state public health department (p < 0:05).

Percentage is significantly greater than for the local public health department (p < 0:05).

Top reported reasons for trust among those with high trust in state and local public health departments include several of the same reasons. For example, nearly 90 percent cited the idea that their state or local public health department followed scientifically valid research (87 percent and 85 percent, respectively), made vaccines and testing widely available (86 percent and 88 percent, respectively), and have given clear recommendations for people to protect themselves (81 percent and 87 percent, respectively).

There were key differences in reported reasons for trust in federal, state, and local public health agencies. One reason related to scientific expertise was cited more often for the CDC: Although 92 percent of those with high trust in the CDC said that it was because they have the experts, only 75 percent and 67 percent of those with high trust in state and local public health departments, respectively, cited this reason. Conversely, three reasons relating to a more compassionate or hands-on approach were cited more commonly for trust in state or local public health departments than in the CDC: that staff worked hard under difficult circumstances (65 percent CDC versus 73 percent state and 79 percent local), that staff seemed to care about people (64 percent CDC versus 69 percent state and 73 percent local), and that the agency provided good care at public health clinics (49 percent CDC versus 58 percent state and 71 percent local).

Performance was one of the least referenced reasons the public said that they had high trust in any of these agencies, as only about half of adults identified doing a good job controlling the spread of COVID-19 as a major reason for their high trust in the CDC (49 percent) or in their state (53 percent) or local (55 percent) public health department. The smallest fraction, roughly one-third or fewer, said that a major reason for their trust was that they trusted the government generally.

REPORTED REASONS FOR LOWER TRUST ACROSS AGENCIES

Reported reasons for lower trust were largely similar across federal, state, and local public health agencies. For example, the top major reason reported for lower trust across agencies was political influence on their recommendations and policies, cited by roughly three-quarters of those with lower trust in each agency (those who trusted them only somewhat, not too much, or not at all: 74 percent CDC, 72 percent state, and 70 percent local) (exhibit 3). Similarly, about half or more of respondents reported private-sector influence on recommendations and policies made by public health agencies, although this was cited more frequently for the CDC than for the other agencies (60 percent CDC versus 53 percent state and 48 percent local). The idea that an agency had given too many conflicting recommendations was also cited by more than half of respondents for each agency but more commonly for the CDC (73 percent CDC versus 61 percent state and 58 percent local).

EXHIBIT 3.

Major reasons for lacking trust in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and state and local public health departments to provide accurate information about COVID-19, among US adults with lower levels of trust, 2022

| Public health departments |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Major reasons for lacking trust | CDC (n = 803) | State (n = 915) | Local (n = 898) |

| Political influence on recommendations and policies | 74% | 72% | 70% |

| Have given too many conflicting recommendations | 73a,b | 61 | 58 |

| Private-sector influence on recommendations and policies | 60a,b | 53 | 48 |

| Inconsistency in following scientifically valid research | 51b | 48 | 43 |

| Restrictive recommendations go too far | 44 | 38 | 42 |

| I don’t trust the government generally | 39 | 39 | 42 |

| Lack of action to stop the spread of COVID-19 | 35 | 34 | 31 |

| Not respected religious beliefs | 28 | 25 | 23 |

| Lack of fair treatment for rural communities | 21 | 21 | 22 |

| Lack of fair treatment for racial and ethnic minority communities | 19 | 25 | 20 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from a February 2022 nationally representative online and telephone survey of 4,208 US adults. NOTES Weighted percentages are displayed, and items are rank-ordered according to major reasons for lacking trust in the CDC. Adults who reported lower trust (“somewhat,” “not very much,” or “not at all”) in each institution to provide accurate information about the COVID-19 outbreak were given a list of 10 potential reasons to choose from. Survey question: “Why don’t you trust [entity] to provide accurate information about the coronavirus outbreak? Are each of the following a major reason, a minor reason, or not a reason at all that you personally don’t trust them a great deal for accurate information?”

Percentage is significantly greater than for the state public health department (p < 0:05).

Percentage is significantly greater than for the local public health department (p < 0:05).

The least reported reasons for lower trust were also similar across agencies. For example, for each agency, one-quarter or fewer of respondents reported that a major reason for lower trust was that the agency had not treated rural communities fairly (21 percent CDC, 21 percent state, and 22 percent local) or had not treated racial and ethnic minority communities fairly (19 percent CDC, 25 percent state, and 20 percent local). Further, not doing enough to stop the spread of COVID-19 was mentioned only by about a third of respondents for any agency (35 percent CDC, 34 percent state, and 31 percent local).

REASONS FOR LOWER TRUST BY DIFFERENT DEGREES OF TRUST

Among each subsegment of the population with a lower degree of trust (those who trusted somewhat, not very much, or not at all), there were differences in reported reasons for lacking trust in each agency (exhibit 4). For example, among adults who trusted these agencies somewhat for accurate COVID-19 information, only two reasons for lacking trust were cited as a major reason by a majority: concerns about political influence on policies and recommendations (61 percent CDC, 62 percent state, and 57 percent local); and concerns that each agency had given too many conflicting recommendations (60 percent CDC, 52 percent state, and 48 percent local). The only other reason that came close was concern that agency recommendations and policies were influenced by the private sector (48 percent CDC, 45 percent state, and 40 percent local).

EXHIBIT 4.

Major reasons for lacking trust in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and state and local public health departments to provide accurate information about COVID-19, among US adults with lower levels of trust, segmented by degrees of trust, 2022

| Public health departments |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDC |

State |

Local |

|||||||

| Major reasons for lacking trust | Somewhat (n = 401) | Not very much (n = 211) | Not at all (n = 191) | Somewhat (n = 545) | Not very much (n = 218) | Not at all (n = 152) | Somewhat (n = 567) | Not very much (n = 193) | Not at all (n = 138) |

| Political influence on recommendations and policies | 61% | 84%a | 91%a | 62% | 83%a | 92%a | 57% | 88%a | 93%a |

| Have given too many conflicting recommendations | 60 | 87a | 86a | 52 | 73a | 79a | 48 | 69a | 84a,b |

| Private-sector influence on recommendations and policies | 48 | 62a | 81a,b | 45a | 65a | 66a | 40 | 58a | 71a |

| Inconsistency in following scientifically valid research | 32 | 65a | 76a | 33 | 64a | 79a,b | 29 | 60a | 76a,b |

| Restrictive recommendations go too far | 24 | 51a | 76a,b | 24 | 50a | 68a,b | 29 | 58a | 71a |

| I don’t trust the government generally | 27 | 45a | 57a | 31 | 45 | 55a | 34 | 55a | 57a |

| Lack of action to stop the spread of COVID-19 | 31 | 43a | 33 | 35 | 29 | 33 | 27 | 36 | 38a |

| Not respected religious beliefs | 16 | 32a | 49a,b | 15 | 33a | 45a | 15 | 28a | 52a |

| Lack of fair treatment for rural communities | 14 | 24a | 30a | 22 | 15 | 25 | 19 | 20 | 32a |

| Lack of fair treatment for racial and ethnic minority communities | 21 | 17 | 18 | 27b | 19 | 23 | 19 | 20 | 27 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from a February 2022 nationally representative online and telephone survey of 4,208 US adults. NOTES Weighted percentages are displayed, and items are rank-ordered according to major reasons for lacking trust in the CDC across all three levels of trust. Adults who reported lower trust (“somewhat,” “not very much,” or “not at all”) in each institution to provide accurate information about the COVID-19 outbreak were given a list of 10 potential reasons to choose from. Survey question: “Why don’t you trust [entity] to provide accurate information about the coronavirus outbreak? Are each of the following a major reason, a minor reason, or not a reason at all that you personally don’t trust them a great deal for accurate information?” Statistically significant differences should be interpreted with caution, as some analyses were conducted among fewer than 200 respondents.

Percentage is significantly greater than for those who “somewhat” trust each entity (p < 0.05).

Percentage is significantly greater than for those who trust each entity “not very much” (p < 0.05).

In contrast, those who were less trusting (not very much or not at all) endorsed all of those reasons to a greater degree across all levels of government, and more than half of these adults endorsed additional reasons across all levels of government. For example, nearly three-quarters of adults with no trust at all cited inconsistency in following scientifically valid research for each agency (76 percent CDC, 79 percent state, and 76 percent local), more than two-thirds reported that agencies’ restrictive recommendations went too far (76 percent CDC, 68 percent state, and 71 percent local), and more than half said that they didn’t trust the government generally (57 percent CDC, 55 percent state, and 57 percent local). About half of those with no trust also reported that each agency had not respected people’s religious beliefs enough (49 percent CDC, 45 percent, state, and 52 percent local).

Discussion

This was the first national survey of US adults on reported reasons for higher and lower trust in federal, state, and local public health agencies’ information during a global public health crisis. It built on a large body of evidence demonstrating the importance of high trust in key institutions, people, and information, and the centrality of trust for the public’s willingness to adopt protective behaviors such as vaccinations and masking.1–7,9 Results include five key takeaways that can inform public health leaders for COVID-19 and future public health emergencies.

ROLES OF SCIENTIFIC CREDIBILITY AND PROTECTIVE RESOURCES

Crucially, results first suggest that in a crisis of this scale, the US public’s trust in public health agencies for information is not strongly related to organizations’ ability to eliminate the outbreak, despite what may seem a natural assumption. Rather, public trust in agencies is related to beliefs that agencies follow scientific evidence in developing policies; have made appropriate resources, such as tests or vaccines, available; and give clear recommendations about how people can protect themselves. Thus, our results provide a critical reminder that public health leaders need not be perfect in crises and need not contain outbreaks immediately to maintain public trust. Instead, they must provide resources to the public, along with clear and consistent recommendations for personal action.6–8 Thus, policies to secure appropriate stocks of key resources (for example, personal protective equipment and vaccines) through better funding and monitoring of the Strategic National Stockpile must be prioritized even outside of emergencies to ensure their immediate availability at the start of outbreaks.24

Moreover, findings reinforce the centrality of emergency communication, which must reasonably explain how agency decisions are anchored to scientific discovery, so that changes in policy or recommendations are seen not as conflicting but rather as responsive evolutions of agency approaches. Further, greater support for conversation about communication efforts between levels of government are needed, so that policies are adapted locally as relevant while still adhering to coherent national efforts. Although communication guidelines have suggested as much, the evidence base for these approaches has been lacking, and communication programs have been historically underfunded, even in emergencies.25,26

VARYING LEVELS OF TRUST ACROSS AGENCIES

Second, there are important differences in reasons why the public trusts federal, state, and local public health agencies. Trust in federal agencies is related primarily to beliefs in scientific expertise, whereas trust in state and local public health agencies is related primarily to their providing direct, compassionate care. Agencies may be able to tailor their communication approaches on the basis of these results. For example, state and local health departments may showcase actions, such as expanding services to improve accessibility for people living with disabilities, in their public communications, whereas the CDC may focus more on its scientific credibility as a means of enhancing trust.

ROLES OF CONSISTENCY AND INFLUENCE

Third, the public’s reported reasons for lower trust in agencies are primarily related to perceptions that agency decisions are inconsistent, influenced by politics, and not based on science. These findings are consistent with prior research documenting public concern about the influence of politics on public health agencies’ scientific decision making and show directly how they connect to trust.3,9,13 Although such findings reinforce the importance of consistent communication during crises, they highlight risks that public perceptions of political influence can undermine agencies’ efforts. It may be important to consider the instances during the COVID-19 pandemic in which agencies’ legal authority to prevent and control the spread of COVID-19 has been shifted to elected officials, and new consideration of approaches to protect their authority may be needed.13,27 In particular, agencies should be given clear lanes of influence as the purveyors of scientific information to elected officials and the public. Moreover, although the private sector is important to developing resources such as vaccines and participating in discourse about the possible impact of recommendations on businesses, agencies may consider processes with more systematic means for input and transparency in how private-sector perspectives are integrated into final recommendations.

NEED FOR TAILORED MESSAGING BY TRUST LEVEL

Fourth, specifically considering members of the public with lesser trust, there are key differences in the primary reasons that each subsegment (those with some, little, or no trust in agencies) reports lacking trust, and tailored communication approaches for each may be needed. Among the subsegment that has some trust in public health agencies, concerns are focused on conflicting recommendations and the perception of political influence. Therefore, to stabilize trust for this subsegment, public health leaders need to prioritize clarity and consistency in messaging and processes, where possible. Results among the least trusting subsegment are very different; this subsegment raises many more concerns, including agencies’ recommendations going too far, limited trust in government generally, and lack of respect for religious beliefs. Building trust with the least trusting members of the US public is a separate, substantial challenge that will require longer-term, bipartisan effort and a focus on communications with trusted messengers who reflect local communities and values.6–9 Such results extend research on risk communications in public health and environmental research broadly, where audience segmentation has been central for meeting audiences’ different communication needs.6,28

MAINTAINING AND BUILDING TRUST

Fifth, and somewhat contrary to some media reports,10 most US adults maintain at least some trust in public health agencies far into the COVID-19 pandemic. This may leave room for agencies to gain trust among those who are somewhat or not very trusting, particularly by working with more trusted partners. Findings here reinforce other surveys showing that health professionals, including doctors and nurses, are more highly trusted sources of information than institutions, and thus they may be particularly effective partners to share and endorse recommendations in both public and clinical settings.7,9,13,29 Payment strategies should be developed to incentivize health professionals to amplify relevant public health information in public as well as privately with patients. Consistent with other surveys, religious leaders and elected officials are not highly trusted for health recommendations,29,30 but these two sources of information are different in important ways. Religious leaders may be highly trusted for nonscientific information and perceived as caring about the community, so they are still credible partners to amplify messages, particularly in highly religious communities.31 However, local politicians are not highly trusted for health recommendations, nor are they seen necessarily as having the community’s interests at heart, so they may be much less likely to be credible partners, and caution is needed for joint communication efforts.

Future research may seek to expand these analyses by examining variation in attitudes about trust across demographic subgroups of the population, particularly historically marginalized communities, to guide more tailored communication approaches going forward.

Conclusion

The results of this national survey provide critical insights on reasons why the US public has higher and lower levels of trust in federal, state, and local public health agencies. Our findings suggest not only a need to enhance policies around stockpiles of protective resources, such as masks, but also a need to support a robust communication infrastructure in which public health agencies are given clear authority to disseminate science-based recommendations. Public health agencies can then develop strategies, both directly and with trusted partners, for effectively engaging different segments of the public who have varying levels of trust. It may be especially helpful to identify opportunities for creating complementary communication strategies at the federal, state and local levels, with more emphasis on scientific expertise at the federal level and more emphasis on compassionate direct services at the state and local levels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study was conducted through a cooperative agreement between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, who subcontracted to the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. Gillian SteelFisher received funding from the CDC; National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health; the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation; and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Her husband is a minority owner of a business that has performed consulting for various pharmaceutical companies. Kathleen Melville is also an adjunct associate professor at Tulane University. Thomas Schafer is also a consultant and editor for and received funding from the Illinois Department of Public Health. Alyssa Boyea and Hannah Caporello received funding from the CDC. The authors are grateful for the contributions of Jazmyne Sutton of SSRS. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC, any other portion of the government of the United States, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, the National Public Health Information Coalition, the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, or SSRS.

Contributor Information

Gillian K. SteelFisher, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts.

Mary G. Findling, Harvard University.

Hannah L. Caporello, Harvard University.

Keri M. Lubell, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

Kathleen G. Vidoloff Melville, General Dynamics Information Technology, Falls Church, Virginia..

Lindsay Lane, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention..

Alyssa A. Boyea, Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, Arlington, Virginia.

Thomas J. Schafer, National Public Health Information Coalition, Niles, Michigan.

Eran N. Ben-Porath, SSRS, Glen Mills, Pennsylvania.

NOTES

- 1.Quinn SC, Jamison AM, An J, Hancock GR, Freimuth VS. Measuring vaccine hesitancy, confidence, trust, and flu vaccine uptake: results of a national survey of White and African American adults. Vaccine. 2019;37(9):1168–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.COVID-19 National Preparedness Collaborators. Pandemic preparedness and COVID-19: an exploratory analysis of infection and fatality rates, and contextual factors associated with preparedness in 177 countries, from Jan 1, 2020, to Sept 30, 2021. Lancet. 2022;399(10334):1489–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry CL, Anderson KE, Han H, Presskreischer R, McGinty EE. Change over time in public support for social distancing, mask wearing, and contact tracing to combat the COVID-19 pandemic among US adults, April to November 2020. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(5):937–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegrist M, Zingg A. The role of public trust during pandemics. Eur Psychol. 2014;19(1):23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moucheraud C, Guo H, Macinko J. Trust in governments and health workers low globally, influencing attitudes toward health information, vaccines. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(8):1215–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson J, Ward PR, Tonkin E, Meyer SB, Pillen H, McCullum D, et al. Developing and maintaining public trust during and post-COVID-19: can we apply a model developed for responding to food scares? Front Public Health. 2020;8:369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Building trust in public health emergency preparedness and response (PHEPR) science: proceedings of a workshop–in brief. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gollust SE, Nagler RH, Fowler EF. The emergence of COVID-19 in the US: a public health and political communication crisis. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2020;45(6):967–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blendon JR, Benson JM. Trust in medicine, the health system, and public health. Daedalus. 2022; 151(4):67–82. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamblin J. Can public health be saved? New York Times [serial on the Internet]. 2022. Mar 12 [cited 2023 Jan 20]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/12/opinion/public-health-trust.html [Google Scholar]

- 11.Limaye RJ, Sauer M, Ali J, Bernstein J, Wahl B, Barnhill A, et al. Building trust while influencing online COVID-19 content in the social media world. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2(6):e277–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agley J, Xiao Y. Misinformation about COVID-19: evidence for differential latent profiles and a strong association with trust in science. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Findling MG, Blendon RJ, Benson JM. Polarized public opinion about public health during the Covid-19 pandemic: political divides and future implications. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(3):e220016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blendon RJ, Benson JM, SteelFisher GK, Connolly JM. Americans’ conflicting views about the public health system, and how to shore up support. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010; 29(11):2033–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Association for Public Opinion Research. AAPOR standards best practices [Internet]. Washington (DC): AAPOR; 2022. Mar [cited 2023 Feb 2]. Available from: https://aapor.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/AAPOR-Standards-best-practices_March-2022.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The public’s perspective on the United States public health system [Internet]. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University; 2021. May [cited 2023 Jan 20]. Available from: https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/94/2021/05/RWJF-Harvard-Report_FINAL-051321.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. KFF Health Tracking Poll–October 2020 [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): KFF; 2020. Oct [cited 2023 Jan 20]. Available from: https://files.kff.org/attachment/Topline-KFF-Health-Tracking-Poll-October-2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holroyd TA, Limaye RJ, Gerber JE, Rimal RN, Musci RJ, Brewer J, et al. Development of a scale to measure trust in public health authorities: prevalence of trust and association with vaccination. J Health Commun. 2021;26(4):272–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 20.Dennison J. A review of public issue salience: concepts, determinants, and effects on voting. Polit Stud Rev. 2019;17(4):436–46. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Visser PS, Krosnick JA, Norris CJ. Attitude importance and attitude-relevant knowledge: motivator and enabler. In: Krosnick JA, Chiang I-CA, Stark TH, editors. Political psychology: new explorations. New York (NY): Psychology Press; 2017. p. 203–45. [Google Scholar]

- 22.SteelFisher GK, Blendon RJ, Bekheit MM, Mitchell EW, Williams J, Lubell K, et al. Novel pandemic A (H1N1) influenza vaccination among pregnant women: motivators and barriers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 204(6)S:S116–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SteelFisher GK, Caporello H, Blendon RJ, Ben-Porath EN, Lubell K, Friedman AL, et al. Views and experiences of travelers from US states to Zika-affected areas. Health Secur. 2019;17(4):307–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The nation’s medical countermeasure stockpile: opportunities to improve the efficiency, effectiveness, and sustainability of the CDC Strategic National Stockpile: workshop summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Emergency preparedness and response: resources for health professionals: crisis and emergency risk communication: training [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2018. Jan 23 [cited 2023 Jan 20]. Available from: https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/training/index.asp [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson CR, Watson M, Sell TK. Public health preparedness funding: key programs and trends from 2001 to 2017. Am J Public Health. 2017; 107(S2):S165–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Legislative prospectus: maintaining public health’s legal authority to prevent disease spread [Internet]. Arlington (VA): ASTHO; 2022. Jan 19 [cited 2023 Jan 20]. Available from: https://www.astho.org/advocacy/state-health-policy/legislative-prospectus-series/2022/public-health-authority/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chryst B, Marlon J, van der Linden S, Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renouf C. Global warming’s “Six Americas Short Survey”: audience segmentation of climate change views using a four question instrument. Environ Commun. 2018; 12(8):1109–22. [Google Scholar]

- 29.SteelFisher GK, Blendon RJ, Caporello H. An uncertain public–encouraging acceptance of Covid-19 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384(16):1483–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wheldon CW, Carroll KT, Moser RP. Trust in health information sources among underserved and vulnerable populations in the U.S. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;31(3):1471–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viskupič F, Wiltse DL. The messenger matters: religious leaders and overcoming COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. PS Polit Sci Polit. 2022; 55(3):504–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.