Abstract

We investigated the underlying mechanism by which the highly conserved N-terminal V3 loop glycan of gp120 conferred resistance to neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). We find that the presence or absence of this V3 glycan on clade A and B viruses accorded various degrees of susceptibility to neutralization by antibodies to the CD4 binding site, CD4-induced epitopes, and chemokine receptors. Our data suggest that this carbohydrate moiety on gp120 blocks access to the binding site for CD4 and modulates the chemokine receptor binding site of phenotypically diverse clade A and clade B isolates. Its presence also contributes to the masking of CD4-induced epitopes on clade B envelopes. These findings reveal a common mechanism by which diverse HIV-1 isolates escape immune recognition. Furthermore, the observation that conserved functional epitopes of HIV-1 are more exposed on V3 glycan-deficient envelope glycoproteins provides a basis for exploring the use of these envelopes as vaccine components.

Despite the early promise of antiviral drug therapy in the treatment of AIDS, the emergence of drug resistance, significant adverse drug side effects, and high cost make it abundantly clear that the development of an efficacious vaccine against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) will ultimately be required to stem the global epidemic. In this regard, recent advances in our understanding of the virus-cell interactions that mediate entry of the virus into target cells (3), as well as the elucidation of structural features of the HIV-1 envelope gp120 (22, 32, 48), provide critical insights into the mechanism(s) by which the virus escapes immune recognition. Collectively, this information should contribute to the rational design of immunogens that will elicit broadly cross-reactive immune protection.

To date, only a few human monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) have been identified that neutralize primary HIV-1 isolates efficiently. Those directed to the gp120 surface envelope glycoprotein recognize discontinuous epitopes overlapping the CD4 binding site (CD4BS) on gp120 (e.g., immunoglobulin G1b12 [IgG1b12] and F105) (6, 29, 30), epitopes that are exposed or induced upon CD4 binding (CD4i) (e.g., 17b and 48d) (42, 49), and a distinctive structure that is dependent on N-linked glycans in the C2, C3, V4, and C4 domains of gp120 (2G12) (5, 45). Of these, the CD4BS antibodies are highly prevalent in patient sera (25) and can neutralize some HIV-1 isolates with strong potency (6, 40, 43). Antibodies to the CD4i epitopes display weaker and more restricted cross-reactive neutralizing ability (42), are relatively rare (20), and need to bind viruses before CD4 binding occurs to achieve neutralization (41). These antibodies are potent inhibitors of the gp120-coreceptor interaction (2, 16, 23, 44, 46). Indeed, structural and mutagenic analyses demonstrate that epitopes recognized by CD4i antibodies are located near the conserved gp120 structure(s) important for interaction with chemokine receptors (22, 32, 48). Although antibodies to the 2G12 epitope have strong neutralizing activity, they are seldom detected in sera from HIV-1-infected individuals (45). The carbohydrate nature of this epitope may account for its apparent poor immunogenicity.

Molecular modeling of the crystal structure of the gp120 core/two-domain CD4/17b Fab fragment complex reveals that the CD4BS epitopes are located in a recessed pocket of gp120 (22, 48). Accessibility to this domain, as well as to the coreceptor binding site, is further hindered by interactions between envelope subunits, the variable V2 and V3 loops, and sugar moieties of gp120 (7, 22, 32, 48, 49). Consistent with this are several studies showing that the deletion of the variable loops, in particular the V2 loop, and removal of specific glycosylation sites of the surface glycoprotein of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) and HIV-1 significantly increase the susceptibility to neutralization of the mutant viruses with seropositive polyclonal sera (1, 8, 9, 31, 33, 37, 39). Thus, attempts to better expose these cross-reactive neutralizing epitopes on gp120-based antigens might improve the immunogenicity as well as vaccine efficacy.

We previously reported that the lack of a highly conserved glycosylation site at amino acid 301 within the N terminus of the V3 loop of the T-cell-tropic SIV-HIV recombinant SHIVSF33 gp120 rendered the virus highly susceptible to neutralization by autologous SHIVSF33 as well as heterologous HIV-1 polyclonal antiserum (9). The latter finding suggests that the epitope that is masked or modulated by this N-linked glycosylation site in the V3 domain is immunogenic both in humans and in macaques. More importantly, this gp120 epitope is shared between the T-cell-line-adapted (TCLA) HIV-1SF33 and primary viruses that establish infections in vivo and should therefore, in principle, elicit broadly cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies. The identification of this epitope and the use of deglycosylated envelope glycoproteins as immunogens might assist in vaccine design and development.

To this end, we herein define the nature of the epitope that is masked or modulated by the presence of the highly conserved N-terminal V3 glycosylation site on the TCLA strain HIV-1SF33. We further assess the effect of this carbohydrate modification on the resistance to neutralization of two primary isolates, the clade B HIV-1SF162 and the clade A HIV-1SF170. Lastly, we investigate the effect of this glycosylation change on envelope-mediated entry. Our findings provide insights into how this carbohydrate moiety modifies gp120 structure and contributes to immune evasion and highlight similarities as well as differences in gp120 structure of phenotypically divergent viruses within and between clades.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and antibodies.

Human osteosarcoma cells (HOS) engineered to express CD4 (T4) and the chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 (HOS T4 CXCR4, HOS T4 CCR5, and HOS T4 pBABE cells) were generously provided by N. Landau (Salk Institute, La Jolla, Calif.). The cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing puromycin (1 μg/ml), 10% fetal bovine serum, and antibiotics. 293T cells were cultured in DMEM without puromycin. The human MAb IgG1b12 was obtained from D. Burton (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, Calif.), and the human IgGCD4 chimera was provided by Genentech (South San Francisco, Calif.). MAbs 17b and 48d are well-characterized MAbs that recognize CD4i epitopes (42, 49), and F425-A1g8 recognizes an epitope that overlaps 17b (Cavacini et al., unpublished observations). The anti-CD4 MAb Leu3a was purchased from Becton Dickinson (Mountain View, Calif.), and the bicyclam AMD3100 was a generous gift from Bahige Baroudy of Schering Plough (36). Anti-CCR5 (clone 2D7) and anti-CXCR4 (clone 12G5) were from Pharmingen Inc., San Diego, Calif. All antibodies and agents were diluted to the indicated concentrations in Hanks' balanced salt solution before use.

Construction of WT and V3 glycosylation mutant envelope expression vectors.

For expression of the envelope glycoproteins of HIV-1SF33, HIV-1SF162, and HIV-1SF170, the Env coding fragment of each virus was subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pCAGGS as described previously (9, 10). HIV-1SF33 is a TCLA subtype B CXCR4 (X4)-using strain that does not contain the highly conserved glycosylation site at amino acid 301 in the V3 loop (NNR, numbered according to the prototype HXBc2 sequence [21, 51]). The V3 mutant virus, in which the V3 glycosylation site was restored by substituting arginine with threonine (NNR to NNT), was constructed on the genomic background of SHIVSF33 (9). A 1.4-kb DraIII-MunI fragment of the Env coding sequence from this SHIVSF33 V3 mutant was then used to replace the corresponding sequences in the pCAGGS/SF33 Env expression vector to generate the HIV-1SF33 V3T envelope expression vector. HIV-1SF162 and HIV-1SF170 are primary, CCR5 (R5)-using viruses belonging to clades B and A, respectively (10, 11). Similar to the majority of primary HIV-1 isolates, these viruses contain the potential V3 loop glycosylation site. To construct the V3 deglycosylated counterparts of HIV-1SF162 and HIV-1SF170, site-directed mutagenesis was employed to change amino acids NNT in the wild-type (WT) Env expression plasmids to NNA according to the manufacturer's instructions (QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit; Stratagene, San Diego, Calif.). The presence of the mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing, and the constructs were designated HIV-1SF162 V3A and HIV-1SF170 V3A. Two clones of each mutated envelope expression vector were obtained and characterized to ensure that spontaneous mutations distant from the desired mutation were not responsible for the observed phenotype. Figure 1 summarizes the partial V3 loop sequence, coreceptor usage, the state of V3 loop glycosylation, and the names used for the various envelope glycoproteins.

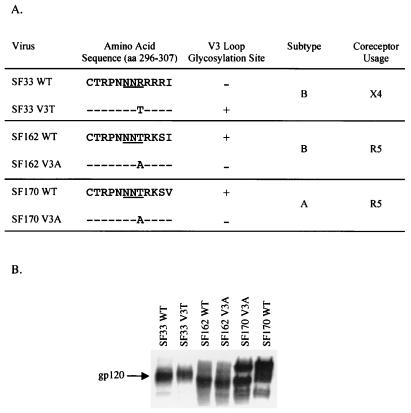

FIG. 1.

(A) Partial V3 loop sequence, coreceptor use, classification, and state of V3 glycosylation of the viruses used. X4, CXCR4 using; R5, CCR5 using; + and −, presence and absence, respectively, of the N-linked glycan at amino acid 301 of envelope gp120 (numbered according to the prototype HXBc2 sequence [21]). (B) Immunoblot analyses of envelope-transfected cell lysates. The position of migration of the gp120 glycoprotein is shown.

Generation of luciferase reporter virus.

A previously described envelope trans-complementation assay was used to generate luciferase reporter viruses capable of only a single round of replication (13). Briefly, 2 μg each of the pCAGGS Env expression plasmid and the NL-Luc-E−R− vector were cotransfected by lipofection into 293T cells (3 × 105 per well) plated in six-well plates (DMRIE-C reagent; Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). Cell culture supernatants were harvested 72 h posttransfection, filtered through 0.45-μm filters, and stored at −70°C in 1-ml aliquots. Viruses were quantitated by a p24gag enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, Ill.).

Immunoblot analyses of envelope proteins.

293T cells transfected with envelope expression plasmids were harvested at 72 h posttransfection and lysed in a solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, and 1% Triton X-100. Cell lysates were denatured by heating to 90°C in sample buffer, and proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–6% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted onto Hybond C-extra membranes (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.). Membranes were blocked with 5% milk–0.2% Tween 20 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in phosphate-buffered saline for 1 h at room temperature. Blocked membranes were reacted with goat-anti-gp120 antibody (provided by Chiron Corp., Emeryville, Calif.), and bands were visualized with horseradish peroxidase-coupled protein G (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) in conjunction with the ECL Western blotting kit (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.).

Neutralization assay.

Neutralization was performed using HOS T4 pBABE, HOS T4 X4, and HOS T4 R5 cells in 96-well plates. Briefly, cells were plated at 7 × 103 per well in a 96-well flat-bottomed culture plate and treated with Polybrene (2 μg/ml; Sigma) for 30 min at 37°C before use. Then 0.5 ng of p24 equivalent from each pseudotyped reporter virus was preincubated, in duplicate, with serial dilutions of antibodies for 1 h at 37°C and then added to cells for an additional 4 h at 37°C. The virus-antibody mixture was then removed, and the cells were fed with DMEM and cultured for 72 h at 37°C. At the end of the culture period, cells were collected, lysed, and processed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Luciferase activity associated with the cell lysate was detected with a Dynex MLX microtiter plate luminometer (Dynex Technologies, Inc., Chantilly, Va.). Infection of coreceptor-bearing cells with NL4-3 virus generated in the absence of Env and infection of HOS T4 pBABE cells lacking coreceptor served as negative controls.

Entry-blocking assay.

For these studies, cells seeded in 96-well plates were preincubated, in duplicate, with serial dilutions of Leu3a, anti-CCR5 MAb 2D7, anti-CXCR4 MAb 12G5, or AMD3100 for 30 min at room temperature. Then 0.5 to 1.0 ng of p24gag equivalent of each virus was added and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. At the end of the incubation period, the antibody-virus mixture was removed, and the cells were fed and cultured for an additional 72 h at 37°C. Luminescence associated with cell lysates was then determined as described above. Cells infected in the absence of antibodies served as positive controls.

RESULTS

V3 loop glycan confers resistance of HIV-1SF33 to neutralization with antibodies directed against the CD4BS and CD4i epitopes.

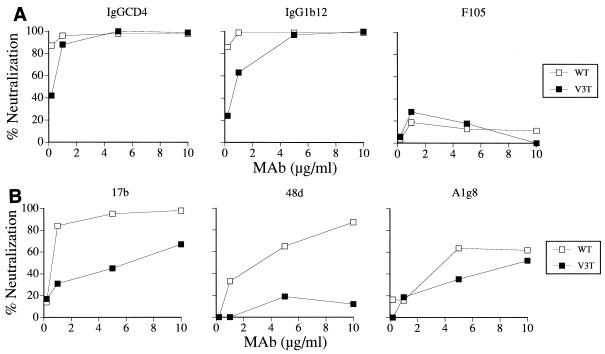

The observation that the absence of glycan at amino acid 301 of the V3 loop of HIV-1SF33 gp120 conferred neutralization sensitivity of the virus to a pool of sera from HIV-1-infected individuals (9) suggested that the epitope(s) modified or exposed by this N-linked carbohydrate is conserved. Biochemical analyses of lysates prepared from cells transfected with HIV-1SF33 WT and V3T envelope expression plasmids showed that V3T gp120 migrated with a slower apparent molecular mass than WT gp120, indicating that the genetic changes introduced in the V3 domain resulted in the anticipated carbohydrate modification (Fig. 1B). In an attempt to identify this epitope modified by V3 glycosylation, we tested the ability of broadly cross-reactive CD4BS and CD4i antibodies to neutralize viruses pseudotyped with WT and V3T mutant glycoproteins of HIV-1SF33. IgGCD4 together with two MAbs directed against the CD4BS, the well-characterized IgG1b12 and F105 MAbs (6, 30), were used. We found that IgGCD4 efficiently neutralized both the WT and V3T virus, with 90% neutralization achieved at 1 and 3 μg/ml, respectively (Fig. 2A). IgG1b12 also potently neutralized the viruses. However, similar to findings with IgGCD4, the WT virus appeared to be more susceptible. Whereas complete neutralization of the glycan-containing V3T virus required 5 μg of the MAb per ml, a fivefold-lower concentration was sufficient for the WT virus. F105, however, was unable to neutralize either virus. The findings with IgGCD4 and IgG1b12 indicate that the N-terminal V3 glycan exerts a modest effect on the CD4 binding site, either by altering or by exposing this site.

FIG. 2.

Neutralization of viruses with the HIV-1SF33 WT and V3T envelope glycoproteins. Recombinant viruses encoding the luciferase gene and bearing either the WT (open symbols) or V3T (solid symbols) envelopes of HIV-1SF33 were incubated with different concentrations of (A) IgGCD4 and CD4BS antibodies IgG1b12 and F105 and (B) CD4i site antibodies 17b, 48d, and A1g8. The virus-antibody mixtures were then inoculated onto HOS T4 X4 cells. Luciferase activity in infected cell lysates was assessed 3 days later and is expressed as the percent inhibition of activity seen in the absence of antibodies. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Upon interaction with CD4, the envelope undergoes a conformational change, causing exposure of the region on gp120 referred to as the CD4i site. This site overlaps the coreceptor binding site, and antibodies directed against it exhibit some cross-neutralizing ability, but mainly for TCLA viruses (35, 42). We tested the ability of three CD4i antibodies, 17b, 48d, and F425-A1g8 (hereafter referred to as A1g8), to neutralize HIV-1SF33 WT and V3T viruses. We observed that >90% neutralization of the WT virus could be achieved with 5 to 10 μg of 17b and 48d per ml (Fig. 2B). The addition of the V3 glycan in the V3T mutant virus, however, altered its susceptibility to neutralization with CD4i antibodies. Only 50% neutralization of the mutant virus was achieved with 17b at 5 μg/ml, and 90% neutralization was not seen at the highest MAb concentration tested (10 μg/ml) (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the mutant virus was resistant to neutralization with 48d. Although the epitope recognized by MAb A1g8 overlapped that of 17b, 90% neutralization of either virus by this MAb was not obtained. Nevertheless, a two- to threefold difference in 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was noted, with the WT virus again being more susceptible than the mutant. These observations suggest that in addition to the CD4BS, the V3 glycan also modulates or obstructs the CD4i site.

V3 loop glycan modulates the CD4BS and CD4i epitopes of a primary clade B isolate.

To extend our observations made with the TCLA HIV-1SF33 strain and to determine whether the effect of the V3 loop carbohydrate on gp120 structure was a feature shared among phenotypic variants of HIV-1, a similar mutation was generated in the background of HIV-1SF162. HIV-1SF162 is a primary, clade B, R5 (for CCR5-using) isolate that naturally possesses the highly conserved V3 loop glycosylation site (Fig. 1A) (11). The mutant envelope glycoprotein that lacks this site, designated HIV-1SF162 V3A, was constructed. Immunoblot analyses of WT and V3A gp120s indicated that this site was also utilized by HIV-1SF162, since there was a difference in the apparent molecular mass of the two proteins (Fig. 1B). The neutralization sensitivity of the HIV-1SF162 envelope-based pseudotyped viruses to the CD4BS and CD4i antibodies was examined and compared to that of HIV-1SF33.

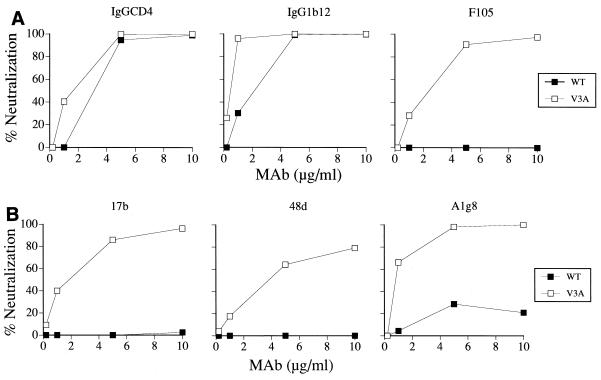

Consistent with reports of a difference in neutralization susceptibility of TCLA and primary viruses with soluble CD4 (14), HIV-1SF162 was found to be more resistant to neutralization with IgGCD4 compared to the TCLA HIV-1SF33 strain (Fig. 2A and 3A). IgGCD4 at 10 μg/ml was required to neutralize the HIV-1SF162 WT virus by >90%. This concentration of IgGCD4 also neutralized the HIV-1SF162 V3A mutant virus to the same extent. However, a modest (approximately twofold) difference in IC50 was consistently observed, with the mutant virus lacking the V3 glycan being more sensitive than WT (Fig. 3A). The IgG1b12 MAb was more potent, achieving 90% neutralization of the glycan-deficient V3T virus at 1 μg/ml, with a fivefold increase in 90% inhibitory concentration (IC90) for the WT virus. The greatest impact of the V3 glycan on the CD4 binding structure, however, was revealed by F105. Whereas the HIV-1SF162 WT virus was resistant, removal of the V3 carbohydrate in V3A conferred a high degree of susceptibility to neutralization of the virus with this antibody (IC90 of 5 μg/ml). These findings again support an effect of the V3 loop glycan on the CD4 binding site of gp120. Furthermore, the observation that the patterns of IgGCD4 and IgG1b12 neutralization of HIV-1SF162 are similar to that seen for HIV-1SF33 suggests a common mechanism by which this V3 glycan modulates the CD4BS on TCLA and primary viruses.

FIG. 3.

Neutralization of viruses with the HIV-1SF162 WT and V3A envelope glycoproteins. The ability of (A) IgGCD4 and CD4BS antibodies IgG1b12 and F105 and (B) CD4i antibodies 17b, 48d, and A1g8 to neutralize infection of HOS T4 R5 cells with luciferase reporter viruses carrying the HIV-1SF162 WT (solid symbols) and V3A (open symbols) envelopes were determined as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The results shown are representative of those obtained in three independent experiments.

A dramatic difference in the susceptibility of HIV-1SF162 WT and the glycan-deficient V3A viruses to neutralization with the CD4i antibodies was observed. We found that the WT virus was resistant (<50% neutralization) to neutralization by all three CD4i MAbs at the highest concentration tested (10 μg/ml), while the mutant V3A virus was sensitive (Fig. 3B). A >90% neutralization of the mutant virus was achieved with the 17b and A1g8 MAbs at 5 μg/ml. Similar concentrations of 48d neutralized the mutant virus by approximately 80%. Thus, although there are quantitative differences, the V3 glycan appears to exert a similar effect on the CD4i site of TCLA and primary isolates in spite of their differences in coreceptor utilization. Furthermore, the observation that the glycan-containing HIV-1SF33 V3T is partially sensitive to CD4i antibodies (Fig. 2B) while HIV-1SF162 WT is resistant (Fig. 3B) is in agreement with the notion that the CD4i sites are more accessible on the surface of TCLA viruses (35, 42). It has been suggested that repositioning of the V1/V2 and V3 loops upon CD4 binding is required to expose the CD4i epitopes (7, 44, 46, 49). Conceivably, a greater movement of the variable loops, in this case the V3 loop of gp120 of TCLA viruses, in the absence of CD4 binding could be responsible for differences in exposure of these epitopes on surface of TCLA compared to primary virions. In this scenario, the role of the V3 loop glycan would be to block rather than to alter the CD4i binding site.

Effect of the V3 loop glycan is partially conserved across clades.

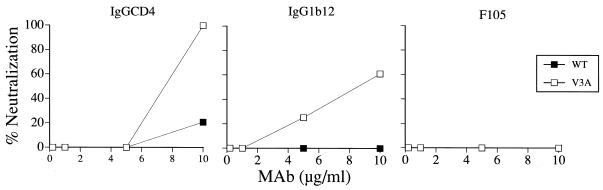

To determine whether the effects of the V3 loop on gp120 structure extended across clades, the clade A R5 HIV-1SF170 strain was selected for comparison. HIV-1SF170 naturally possesses the V3 loop glycan. Therefore, a mutant was constructed which lacked this glycosylation site, in the same manner as for HIV-1SF162 (Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig. 1B, this site also appeared to be utilized in HIV-1SF170. In general, we found the primary clade A HIV-1SF170 WT pseudotyped virus to be more resistant to neutralization by IgGCD4 and CD4BS antibodies (Fig. 4) than the primary clade B HIV-1SF162 (Fig. 3A). However, removal of the V3 loop glycan on HIV-1SF170 did significantly increase the susceptibility of the virus to neutralization by IgGCD4. With IgGCD4 at 10 μg/ml, 90% neutralization of HIV-1SF170 V3A was achieved, whereas the WT virus was resistant. Similarly, although IgG1b12 was unable to neutralize the WT virus, it showed a modest degree of neutralization of the mutant virus (IC50, ∼8 μg/ml). Both HIV-1SF170 WT and V3A viruses, however, were resistant to neutralization with F105. The comparable effect exerted by the V3 loop glycan on neutralization sensitivity of clade B and A viruses with IgGCD4 and IgG1b12 indicates that the function of this carbohydrate moiety in occluding the CD4BS is conserved across clades.

FIG. 4.

Neutralization of HIV-1SF170 WT and V3A reporter viruses by IgGCD4 and CD4BS antibodies IgG1b12 and F105. Neutralization with the CD4BS MAbs was performed as described above using HOS T4 R5 cells. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

All three CD4i antibodies tested failed to neutralize the HIV-1SF170 WT and V3A viruses (data not shown). The inability of these antibodies to neutralize the glycan-possessing HIV-1SF170 is similar to that seen for HIV-1SF162, but differs from the HIV-1SF33 V3T virus. Although the removal of the V3 loop glycan did increase susceptibility of HIV-1SF162 to neutralization by the CD4i antibodies, this was not translated across to clade A, at least in the context of HIV-1SF170. The 17b MAb binds to both HIV-1SF170 WT and V3A monomeric gp120s, indicating that this epitope is present (data not shown). Collectively, the data suggest that accessibility to the CD4i epitopes is restricted on oligomeric gp120 of HIV-1SF170, and this is not relieved by removal of the V3 loop glycan. A more limited movement of the V3 loop of HIV-1SF170 compared to the clade B viruses could potentially explain the differences observed. Thus, removal of the V3 glycan in the absence of V3 loop movement may be insufficient to expose the CD4i epitopes.

V3 loop glycan-deficient viruses are not CD4 independent even though CD4i epitopes are exposed.

The observation that V3 glycan-deficient clade B viruses are more susceptible to neutralization with CD4i MAbs, coupled with the finding that these antibodies need to bind to virus before CD4 binding to achieve neutralization (41), indicates that the CD4i epitopes are more exposed in the absence of this carbohydrate moiety. Since CD4i epitope exposure has been associated with better entry efficiency and gain of CD4 independence (17, 41), the ability of WT and mutant viruses to enter cells in the presence and absence of CD4 was investigated. We found that the V3 glycan-deficient viruses HIV-1SF33 WT, HIV-1SF162 V3A, and HIV-1SF170 V3A entered CD4-positive cells with higher efficiency (two- to fourfold) than their glycosylated counterparts (Fig. 5). Enhanced entry of the HIV-1SF33 WT and HIV-1SF162 V3A viruses therefore correlated with increased exposure of the CD4i epitope (Fig. 2B and 3B) and is consistent with their envelopes being in a more fusion-ready state. Nevertheless, the observation that HIV-1SF170 V3A also exhibited enhanced entry, in the apparent absence of CD4i epitope exposure, suggested that another mechanism(s) may be involved. The V3 glycan-deficient viruses, however, are still dependent on CD4 for entry. Blocking of the CD4 receptor on target cells with MAb Leu3A prevented entry of WT and mutant viruses of all three strains in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6). A similar pattern was observed when Leu3A was added at the same time as the viruses (data not shown).

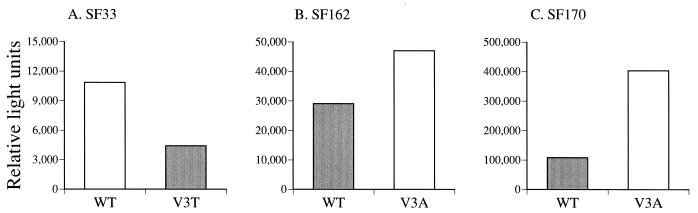

FIG. 5.

Entry into target cells of (A) HIV-1SF33, (B) HIV-1SF162, and (C) HIV-1SF170 pseudotyped viruses with and without V3 loop glycan. The ability of recombinant viruses carrying the various envelope glycoproteins to enter target cells (HOS T4 X4 cells for HIV-1SF33 and HOS T4 R5 cells for HIV-1SF162 and HIV-1SF170) was determined by assessing the luciferase activity of infected cell lysates. Open bars represent luciferase activity associated with viruses lacking the V3 loop glycosylation site, and solid bars represent viruses that have the glycosylation site. Results from a representative of at least five independent experiments are shown.

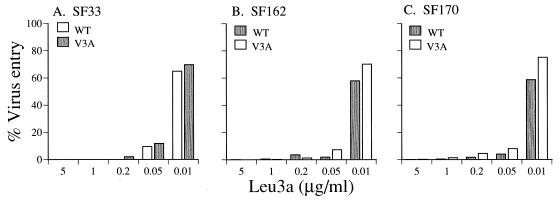

FIG. 6.

Blocking of virus entry with the anti-CD4 antibody Leu3A. The ability of viruses carrying the various envelope glycoproteins to enter target cells that had been preincubated with increasing concentrations of the anti-CD4 antibody Leu3A was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the percentage of luciferase activity seen in the absence of the MAb and are representative of at least three independent experiments.

V3 loop glycan alters the coreceptor binding site of gp120.

The effects exerted by the V3 loop glycan on epitopes that overlapped the coreceptor binding site and studies showing that amino acid changes in the V3 loop influenced coreceptor binding (15, 18, 38) prompted us to examine the interaction of the various envelope glycoproteins with chemokine receptors. Increasing concentrations of the anti-CXCR4 MAb 12G5 and compound AMD3100 or the anti-CCR5 MAb 2D7 were used to block the corresponding chemokine receptors on target cells. The susceptibility of these cells to infection with V3 glycosylated and deglycosylated viruses was then determined. We observed that all viruses maintained their coreceptor specificity. That is, the HIV-1SF33 envelope-based viruses use CXCR4, whereas the HIV-1SF162 and HIV-1SF170 viruses use CCR5. The anti-CXCR4 MAb 12G5 inhibited entry of the V3 glycan-possessing HIV-1SF33 V3T virus in a dose-dependent manner, but the WT virus was resistant at all concentrations of MAb tested (Fig. 7). The anti-CXCR4 compound AMD3100, however, blocked infection of both viruses, with the WT virus again being more resistant than V3T. For the primary clade B and A isolates, entry of both WT and V3 deglycosylated viruses was inhibited by the anti-CR5 MAb 2D7, but different concentrations were required. In contrast to the results for the X4 viruses, the R5 deglycosylated viruses appeared to be more susceptible to blocking with 2D7. Whereas 50% inhibition of entry for the WT (V3 glycan possessing) virus required 5 μg of the 2D7 MAb per ml, the same inhibition for the corresponding V3 deglycosylated virus could be achieved with only 0.2 μg/ml. A similar pattern was observed for the HIV-1SF162 and HIV-1SF170 viruses. Thus, a model in which exposure of the coreceptor binding site in the V3 loop glycan-deficient virus increases the efficiency of coreceptor usage and therefore confers resistance to blocking with anticoreceptor antibodies or agent is supported by findings with the clade B X4 but not R5 viruses. It is conceivable that in addition to or instead of influencing the exposure and hence the affinity of gp120-coreceptor interaction, this V3 glycan modulates the structure of the V3 loop and in turn the site on chemokine receptors with which gp120 interacts. Indeed, the observation that this V3 glycan altered the susceptibility to neutralization of TCLA viruses with anti-V3 MAbs suggested that its presence or absence modified the structure of the V3 loop (1, 37). Similarly, we observed differences in susceptibility to neutralization with the anti-V3 loop MAb F425 B4a1 of the HIV-1SF162 WT and V3A viruses (data not shown).

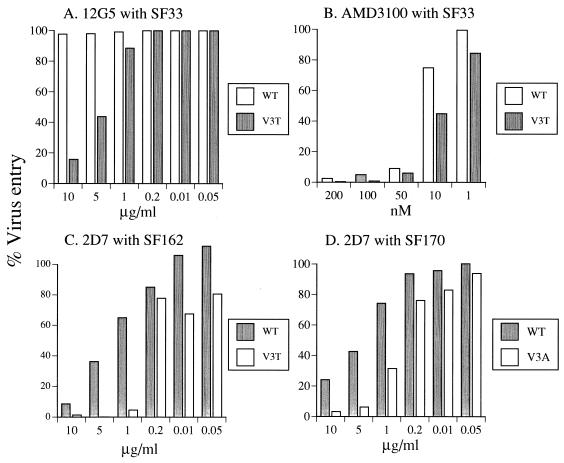

FIG. 7.

Blocking of virus entry with anticoreceptor molecules. The ability of (A) anti-CXCR4 MAb 12G5 and (B) the bicyclam AMD3100 (36) to block entry of HIV-1SF33 WT (open symbols) and V3T (solid symbols) viruses or (C and D) anti-CCR5 MAb 2D7 to block HIV-1SF162 (C) and HIV-1SF170 (D) WT (solid symbols) and V3 loop glycosylation variants (open symbols) was determined as described in the text. Virus entry is expressed as the percentage of luciferase activity seen in the absence of MAbs or compound. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Our studies show that the presence or absence of a highly conserved N-linked glycosylation site in the V3 loop modifies the structure and function of envelope gp120 of both TCLA and primary subtype B viruses as well as a subtype A isolate. We found that removal of the N-terminal glycosylation site in the V3 loop conferred various degrees of enhanced sensitivity to neutralization by MAbs directed against the CD4 binding site (Fig. 2A, 3A, and 4). All V3 deglycosylated viruses exhibited increased sensitivity to neutralization with IgGCD4 and IgG1b12, but only the primary clade B HIV-1SF162 V3 glycan-deficient virus was neutralized by F105. These differences in neutralization susceptibility of the viruses by some CD4BS MAbs likely reflect the moderate degree of sequence variation that is tolerated in the regions adjacent to and surrounding the CD4 binding pocket of gp120 (48).

Structural and functional interactions between the V3 loop and the CD4 binding site have been reported (1, 19, 27, 28, 32, 50), leading to the suggestion that elements of these two regions are in close proximity and that the V3 loop serves to partially mask the CD4 binding site. Consistent with this are recent crystal structure analyses of gp120 showing that the CD4 binding site is recessed, flanked by variable regions that exhibit considerable glycosylation (22, 48). Collectively, our findings are in support of a model in which the presence of sugar moieties at the N terminus of the V3 of gp120 either directly or indirectly, through modulation of the structure of the V3 loop, blocks access by antibodies to some elements of the CD4 binding site. Modification at this particular V3 glycan site exerted similar effects on neutralization susceptibility of TCLA (HIV-1SF33) and primary clade B (HIV-1SF162) HIV-1 isolates, as well as for the clade A isolate HIV-1SF170 by IgGCD4 and IgG1b12. Interestingly, IgG1b12 is a particularly potent CD4BS antibody whose epitope might contain residues that directly contact CD4 (22, 48). These findings therefore suggest that the conservation of the carbohydrate side chain of the V3 loop serves to block access to the gp120 structure that directly interacts with CD4.

Further support for a conserved function of the V3 N-terminal glycan comes from the observation that removal of this site renders the clade B viruses highly susceptible to neutralization with antibodies that are directed to the CD4i epitopes (17b, 48d, and A1g8) (Fig. 2B and 3B). The CD4i epitopes lie near or within the bridging sheet recently described in the gp120 crystal structure (22, 48). This bridging sheet spans the outer and inner domains of gp120 and is expected to face the target cell after binding of the envelope glycoprotein to CD4. Although the V3 loop is not part of the 17b epitope, residues of the V3 loop may contact or block elements of the 17b epitope (7, 22, 26, 32, 44, 46, 48, 49). Taken together, our observations are consistent with a role of this N-terminal V3 carbohydrate side chain in the masking of CD4i epitopes as well as the CD4 binding site. An overlap between the CD4BS epitopes and the CD4i epitope has previously been suggested by antibody competition studies (26, 42). Since a bigger effect is seen for the CD4i epitopes than the CD4BS epitopes, greater restriction on access to the CD4i region appears to be exerted by the presence of this V3 sugar moiety. This is consistent with the crystal structure of gp120, which shows that the CD4i region lies in spatial proximity to the base of the V3 loop, in contrast to the CD4BS, which is farther away (22, 48). The neutralization sensitivity of both the TCLA and primary subtype B isolates by CD4i antibodies was influenced by changes in this V3 glycosylation site (Fig. 2B and 3B). This is in support of a similarity in the gp120 structures that are involved in exposure of CD4i epitopes of phenotypic variants of HIV-1 (41).

The WT and V3 deglycosylation mutant of the clade A HIV-1SF170 strain, however, resisted neutralization by the CD4i antibodies tested. The 17b/48d epitope is conserved among genetically diverse HIV-1 isolates (34) and is present on monomeric gp120 of HIV-1SF170 (data not shown). Movement of the V1/V2 and V3 loops upon CD4 binding has been suggested to be necessary for the exposure of the CD4i epitopes (7, 42, 49). The movement of the V3 loop, in the absence of CD4, of the oligomeric gp120 of HIV-1SF170 may be more restrained than that of HIV-1SF162 and HIV-1SF33. For HIV-1SF170, removal of the V3 glycan is not sufficient to unmask the CD4i epitopes in the absence of V3 loop movement, rendering HIV-1SF170 V3A resistant to neutralization with antibodies directed against this site. Whether the lack of an effect of V3 deglycosylation on CD4i epitope exposure of HIV-1SF170 reflects a structural difference in gp120 that is unique for this particular virus or represents a common structural difference between clade A and B viruses is presently unknown. Analysis of additional envelope glycoproteins from both clades will be necessary to address this question.

Concomitant with an increase in CD4i epitope exposure, alleviation of the V3 glycosylation site resulted in increased entry efficiency of the clade B viruses tested (Fig. 5). However, these viruses were still dependent on CD4 for entry (Fig. 6A and B). The subtype A HIV-1SF170 V3 glycosylation mutant also entered more efficiently (Fig. 5), but in the apparent absence of an increase in CD4i epitope exposure (data not shown). These observations suggest that in addition to the CD4i epitopes, V3 glycosylation affects another gp120 structure(s) that is required for virus entry. This structure could be the CD4 binding site. The creation and/or exposure of the CD4BS as a result of removal of this V3 glycan in HIV-1SF170, as discussed above, could facilitate gp120-CD4 interaction, leading to better entry of the V3-deglycosylated virus. Indeed, the effect of V3 glycosylation on neutralization with IgGCD4 is greater for HIV-1SF170 than for the other two viruses (Fig. 2A, 3A, and 4), and in accord with this, the HIV-1SF170 V3-deglycosylated virus entered with significantly better efficiency (fourfold) than the other deglycosylation mutants compared to their glycosylated counterparts (approximately twofold). However, these entry assays were conducted with cells expressing high levels of CD4, and it is questionable whether any effects mediated by modest differences in CD4 binding caused by the state of V3 glycosylation would be revealed. Furthermore, we do not find any difference in the ability of HIV-1SF170 WT and V3-deglycosylated viruses to compete with the anti-CD4 MAb Leu3A for binding to CD4 (data not shown). Thus, the possibility exists that this V3 glycan affects gp120 structures other than the CD4BS and CD4i epitopes in facilitating virus entry. Since gp120 crystal structural and mutational analyses, together with antibody competition studies, show that the CCR5 binding site is composed of elements near or within the bridging sheet and residues of the V3 loop (12, 15, 18, 22, 26, 32, 38, 46, 48), this structure could be the chemokine receptor binding site.

Support for participation of the V3 glycan in coreceptor binding is illustrated in the blocking studies with antibodies and compounds directed against chemokine coreceptors. Whereas the anti-CXCR4 antibody 12G5 blocked entry of the glycan-possessing V3T virus of the TCLA HIV-1SF33 in a dose-dependent manner, the WT virus was resistant (Fig. 7). The anti-CXCR4 compound, however, inhibited entry of both viruses, but higher concentrations are also required to block the WT virus than V3T. In contrast, for both the R5-using HIV-1SF162 and HIV-1SF170 viruses, the presence of the V3 glycan (in this case, the WT viruses) conferred higher resistance to blocking with the anti-CCR5 MAb 2D7. The anti-chemokine receptor MAbs and compounds used are believed to block entry by competing for the gp120 binding site on chemokine receptors (24, 36, 47). In this regard, resistance of WT HIV-1SF33 to blocking with 12G5 suggests that this virus enters target cells via interaction with a site on CXCR4 that is different from the epitope recognized by 12G5. Susceptibility of WT virus to inhibition with AMD3100 suggests that this site partially overlaps that targeted by this compound. Addition of the V3 glycan to HIV-1SF33 now allows the mutant virus to function with the 12G5 epitope on CXCR4 for entry. Indeed, differential utilization of the CXCR4 receptor by HIV-1 has been reported previously (24). For HIV-1SF162 and HIV-1SF170, the viruses lacking the V3 glycan interact with a site on CCR5 that overlaps to a greater degree the 2D7 epitope on CCR5. Thus, the V3-deglycosylated viruses are more sensitive to blocking with MAb 2D7 than the WT virus (Fig. 7C and D). Whether the V3 loop glycan also modified the binding affinity of the envelopes to chemokine receptors, however, requires further investigation. Regardless, the observation that a similar effect on entry of HIV-1SF162 and HIV-1SF170 viruses is exerted by the anti-CCR5 MAb 2D7 is interesting. This indicates that the clade A and B R5-Env interaction is similar and is consistent with the coreceptor binding structure of gp120 being highly conserved. The V3 carbohydrate side chain could be part of the coreceptor binding site or might cause conformational changes in the V3 loop that alter coreceptor binding. Lastly, the finding that this V3 glycan affected the ways in which the virus utilizes both the CXCR4 and CCR5 coreceptors is in support of a similarity in the gp120 binding site for the CXCR4 and CCR5 coreceptors (32).

In summary, our studies define a gp120 structural feature, the N-terminal V3 loop glycan, that appears to serve a common function for genetically diverse HIV-1 viruses. Our data suggest that the V3 loop glycan occludes a region on the ridge at the intersection of the two receptor-binding gp120 surfaces, allowing escape from immune recognition. In addition to CD4BS and CD4i epitope exposure, V3 deglycosylation influences the coreceptor binding site. Although the V3 glycan-deficient viruses enter target cells more efficiently, they are more susceptible to antibody-mediated neutralization. In this regard, it is interesting to note that in vivo, viruses trade a potential advantage in entry for the benefits of immune evasion. Our findings that the V3 loop glycan unmasks, either directly or indirectly, gp120 structures that are principally involved in virus entry of divergent isolates raise the possibility that the use of V3-deglycosylated envelope glycoproteins as immunogens may elicit broadly cross-reactive neutralizing activity. Indeed, deglycosylated Envs have been reported to modulate immune responses (4, 31). Whether the V3 glycan-deficient envelope glycoproteins will be immunogenic and elicit antibodies that are of sufficient titers and potency to overcome the block to their epitopes on primary viruses remains to be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants AI41945 and CA72822 (C.C.-M.), AI24030 (J.R.), AI45321 (L.C.), and AI26926 (M.P.).

We thank Lisa Chakrabarti and Leonidas Stamatatos for helpful discussions and Wendy Chen for help with the graphics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Back N K, Smit L, De Jong J J, Keulen W, Schutten M, Goudsmit J, Tersmette M. An N-glycan within the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 V3 loop affects virus neutralization. Virology. 1994;199:431–438. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandres J C, Wang Q F, O'Leary J, Baleaux F, Amara A, Hoxie J A, Zolla-Pazner S, Gorny M K. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) envelope binds to CXCR4 independently of CD4, and binding can be enhanced by interaction with soluble CD4 or by HIV envelope deglycosylation. J Virol. 1998;72:2500–2504. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2500-2504.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger E A, Murphy P M, Farber J M. Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism, and disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:657–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolmstedt A, Olofsson S, Sjogren-Jansson E, Jeansson S, Sjoblom I, Akerblom L, Hansen J E, Hu S L. Carbohydrate determinant NeuAc-Gal beta (1-4) of N-linked glycans modulates the antigenic activity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp120. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:3099–3105. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-12-3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchacher A, Predl R, Strutzenberger K, Steinfellner W, Trkola A, Purtscher M, Gruber G, Tauer C, Steindl F, Jungbauer A, et al. Generation of human monoclonal antibodies against HIV-1 proteins; electrofusion and Epstein-Barr virus transformation for peripheral blood lymphocyte immortalization. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:359–369. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton D R, Pyati J, Koduri R, Sharp S J, Thornton G B, Parren P W, Sawyer L S, Hendry R M, Dunlop N, Nara P L, et al. Efficient neutralization of primary isolates of HIV-1 by a recombinant human monoclonal antibody. Science. 1994;266:1024–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.7973652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao J, Sullivan N, Desjardin E, Parolin C, Robinson J, Wyatt R, Sodroski J. Replication and neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 lacking the V1 and V2 variable loops of the gp120 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1997;71:9808–9812. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9808-9812.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chackerian B, Rudensey L M, Overbaugh J. Specific N-linked and O-linked glycosylation modifications in the envelope V1 domain of simian immunodeficiency virus variants that evolve in the host alter recognition by neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 1997;71:7719–7727. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7719-7727.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng-Mayer C, Brown A, Harouse J, Luciw P A, Mayer A J. Selection for neutralization resistance of the simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIVSF33A variant in vivo by virtue of sequence changes in the extracellular envelope glycoprotein that modify N-linked glycosylation. J Virol. 1999;73:5294–5300. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5294-5300.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng-Mayer C, Liu R, Landau N R, Stamatatos L. Macrophage tropism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and utilization of the CC-CKR5 coreceptor. J Virol. 1997;71:1657–1661. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1657-1661.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng-Mayer C, Quiroga M, Tung J W, Dina D, Levy J A. Viral determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 T-cell or macrophage tropism, cytopathogenicity, and CD4 antigen modulation. J Virol. 1990;64:4390–4398. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4390-4398.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cocchi F, DeVico A L, Garzino-Demo A, Cara A, Gallo R C, Lusso P. The V3 domain of the HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein is critical for chemokine-mediated blockade of infection. Nat Med. 1996;2:1244–1247. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connor R I, Chen B K, Choe S, Landau N R. Vpr is required for efficient replication of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 in mononuclear phagocytes. Virology. 1995;206:935–944. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daar E S, Li X L, Moudgil T, Ho D D. High concentrations of recombinant soluble CD4 are required to neutralize primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6574–6578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Etemad-Moghadam B, Sun Y, Nicholson E K, Fernandes M, Liou K, Gomila R, Lee J, Sodroski J. Envelope glycoprotein determinants of increased fusogenicity in a pathogenic simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV-KB9) passaged in vivo. J Virol. 2000;74:4433–4440. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4433-4440.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill C M, Deng H, Unutmaz D, Kewalramani V N, Bastiani L, Gorny M K, Zolla-Pazner S, Littman D R. Envelope glycoproteins from human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 and simian immunodeficiency virus can use human CCR5 as a coreceptor for viral entry and make direct CD4-dependent interactions with this chemokine receptor. J Virol. 1997;71:6296–6304. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6296-6304.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman T L, LaBranche C C, Zhang W, Canziani G, Robinson J, Chaiken I, Hoxie J A, Doms R W. Stable exposure of the coreceptor-binding site in a CD4-independent HIV-1 envelope protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6359–6364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hung C S, Vander Heyden N, Ratner L. Analysis of the critical domain in the V3 loop of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 involved in CCR5 utilization. J Virol. 1999;73:8216–8226. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8216-8226.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwang S S, Boyle T J, Lyerly H K, Cullen B R. Identification of envelope V3 loop as the major determinant of CD4 neutralization sensitivity of HIV-1. Science. 1992;257:535–537. doi: 10.1126/science.1636088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang C Y, Hariharan K, Posner M R, Nara P. Identification of a new neutralizing epitope conformationally affected by the attachment of CD4 to gp120. J Immunol. 1993;151:449–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korber B, Foley B, Kuiken C, Pillai S, Sodroski J. Numbering positions in HIV relative to HXB2, p. IV-27–IV-35. In: Korber B, Brander C, Haynes B, Koup R, Moore J, Walker B, editors. Human retroviruses and AIDS 1998. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwong P D, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet R W, Sodroski J, Hendrickson W A. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lapham C K, Ouyang J, Chandrasekhar B, Nguyen N Y, Dimitrov D S, Golding H. Evidence for cell-surface association between fusin and the CD4-gp120 complex in human cell lines. Science. 1996;274:602–605. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKnight A, Wilkinson D, Simmons G, Talbot S, Picard L, Ahuja M, Marsh M, Hoxie J A, Clapham P R. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus fusion by a monoclonal antibody to a coreceptor (CXCR4) is both cell type and virus strain dependent. J Virol. 1997;71:1692–1696. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1692-1696.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore J P, Ho D D. Antibodies to discontinuous or conformationally sensitive epitopes on the gp120 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 are highly prevalent in sera of infected humans. J Virol. 1993;67:863–875. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.863-875.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore J P, Sodroski J. Antibody cross-competition analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 exterior envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1996;70:1863–1872. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1863-1872.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore J P, Thali M, Jameson B A, Vignaux F, Lewis G K, Poon S W, Charles M, Fung M S, Sun B, Durda P J, et al. Immunochemical analysis of the gp120 surface glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: probing the structure of the C4 and V4 domains and the interaction of the C4 domain with the V3 loop. J Virol. 1993;67:4785–4796. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4785-4796.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Brien W A, Chen I S, Ho D D, Daar E S. Mapping genetic determinants for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to soluble CD4. J Virol. 1992;66:3125–3130. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.3125-3130.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Posner M R, Cavacini L A, Emes C L, Power J, Byrn R. Neutralization of HIV-1 by F105, a human monoclonal antibody to the CD4 binding site of gp120. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Posner M R, Hideshima T, Cannon T, Mukherjee M, Mayer K H, Byrn R A. An IgG human monoclonal antibody that reacts with HIV-1/GP120, inhibits virus binding to cells, and neutralizes infection. J Immunol. 1991;146:4325–4332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reitter J N, Means R E, Desrosiers R C. A role for carbohydrates in immune evasion in AIDS. Nat Med. 1998;4:679–684. doi: 10.1038/nm0698-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rizzuto C D, Wyatt R, Hernandez-Ramos N, Sun Y, Kwong P D, Hendrickson W A, Sodroski J. A conserved HIV gp120 glycoprotein structure involved in chemokine receptor binding. Science. 1998;280:1949–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudensey L M, Kimata J T, Long E M, Chackerian B, Overbaugh J. Changes in the extracellular envelope glycoprotein of variants that evolve during the course of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVMne infection affect neutralizing antibody recognition, syncytium formation, and macrophage tropism but not replication, cytopathicity, or CCR-5 coreceptor recognition. J Virol. 1998;72:209–217. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.209-217.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salzwedel K, Smith E D, Dey B, Berger E A. Sequential CD4-coreceptor interactions in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env function: soluble CD4 activates Env for coreceptor-dependent fusion and reveals blocking activities of antibodies against cryptic conserved epitopes on gp120. J Virol. 2000;74:326–333. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.326-333.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sattentau Q J, Moore J P. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neutralization is determined by epitope exposure on the gp120 oligomer. J Exp Med. 1995;182:185–196. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schols D, Este J A, Henson G, De Clercq E. Bicyclams, a class of potent anti-HIV agents, are targeted at the HIV coreceptor fusin/CXCR-4. Antiviral Res. 1997;35:147–156. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(97)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schonning K, Jansson B, Olofsson S, Nielsen J O, Hansen J S. Resistance to V3-directed neutralization caused by an N-linked oligosaccharide depends on the quaternary structure of the HIV-1 envelope oligomer. Virology. 1996;218:134–140. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Speck R F, Wehrly K, Platt E J, Atchison R E, Charo I F, Kabat D, Chesebro B, Goldsmith M A. Selective employment of chemokine receptors as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptors determined by individual amino acids within the envelope V3 loop. J Virol. 1997;71:7136–7139. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.7136-7139.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stamatatos L, Cheng-Mayer C. An envelope modification that renders a primary, neutralization-resistant clade B human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate highly susceptible to neutralization by sera from other clades. J Virol. 1998;72:7840–7845. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7840-7845.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steimer K S, Scandella C J, Skiles P V, Haigwood N L. Neutralization of divergent HIV-1 isolates by conformation-dependent human antibodies to Gp120. Science. 1991;254:105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.1718036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sullivan N, Sun Y, Sattentau Q, Thali M, Wu D, Denisova G, Gershoni J, Robinson J, Moore J, Sodroski J. CD4-induced conformational changes in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 glycoprotein: consequences for virus entry and neutralization. J Virol. 1998;72:4694–4703. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4694-4703.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thali M, Moore J P, Furman C, Charles M, Ho D D, Robinson J, Sodroski J. Characterization of conserved human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 neutralization epitopes exposed upon gp120-CD4 binding. J Virol. 1993;67:3978–3988. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3978-3988.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tilley S A, Honnen W J, Racho M E, Hilgartner M, Pinter A. A human monoclonal antibody against the CD4-binding site of HIV1 gp120 exhibits potent, broadly neutralizing activity. Res Virol. 1991;142:247–259. doi: 10.1016/0923-2516(91)90010-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trkola A, Dragic T, Arthos J, Binley J M, Olson W C, Allaway G P, Cheng-Mayer C, Robinson J, Maddon P J, Moore J P. CD4-dependent, antibody-sensitive interactions between HIV-1 and its co-receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384:184–187. doi: 10.1038/384184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trkola A, Purtscher M, Muster T, Ballaun C, Buchacher A, Sullivan N, Srinivasan K, Sodroski J, Moore J P, Katinger H. Human monoclonal antibody 2G12 defines a distinctive neutralization epitope on the gp120 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1996;70:1100–1108. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1100-1108.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu L, Gerard N P, Wyatt R, Choe H, Parolin C, Ruffing N, Borsetti A, Cardoso A A, Desjardin E, Newman W, Gerard C, Sodroski J. CD4-induced interaction of primary HIV-1 gp120 glycoproteins with the chemokine receptor CCR-5 [see comments] Nature. 1996;384:179–183. doi: 10.1038/384179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu L, LaRosa G, Kassam N, Gordon C J, Heath H, Ruffing N, Chen H, Humblias J, Samson M, Parmentier M, Moore J P, Mackay C R. Interaction of chemokine receptor CCR5 with its ligands: multiple domains for HIV-1 gp120 binding and a single domain for chemokine binding. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1373–1381. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wyatt R, Kwong P D, Desjardins E, Sweet R W, Robinson J, Hendrickson W A, Sodroski J G. The antigenic structure of the HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Nature. 1998;393:705–711. doi: 10.1038/31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wyatt R, Moore J, Accola M, Desjardin E, Robinson J, Sodroski J. Involvement of the V1/V2 variable loop structure in the exposure of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 epitopes induced by receptor binding. J Virol. 1995;69:5723–5733. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5723-5733.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wyatt R, Thali M, Tilley S, Pinter A, Posner M, Ho D, Robinson J, Sodroski J. Relationship of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 third variable loop to a component of the CD4 binding site in the fourth conserved region. J Virol. 1992;66:6997–7004. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.6997-7004.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.York-Higgins D, Cheng-Mayer C, Bauer D, Levy J A, Dina D. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cellular host range, replication, and cytopathicity are linked to the envelope region of the viral genome. J Virol. 1990;64:4016–4020. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.8.4016-4020.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]