Abstract

Polyploidization presents an unusual challenge for species with sex chromosomes, as it can lead to complex combinations of sex chromosomes that disrupt reproductive development. This is particularly true for allopolyploidization between species with different sex chromosome systems. Here, we assemble haplotype-resolved chromosome-level genomes of a female allotetraploid weeping willow (Salix babylonica) and a male diploid S. dunnii. We show that weeping willow arose from crosses between a female ancestor from the Salix-clade, which has XY sex chromosomes on chromosome 7, and a male ancestor from the Vetrix-clade, which has ancestral XY sex chromosomes on chromosome 15. We find that weeping willow has one pair of sex chromosomes, ZW on chromosome 15, that derived from the ancestral XY sex chromosomes in the male ancestor of the Vetrix-clade. Moreover, the ancestral 7X chromosomes from the female ancestor of the Salix-clade have reverted to autosomal inheritance. Duplicated intact ARR17-like genes on the four homologous chromosomes 19 likely have contributed to the maintenance of dioecy during polyploidization and sex chromosome turnover. Taken together, our results suggest the rapid evolution and reversion of sex chromosomes following allopolyploidization in weeping willow.

Subject terms: Evolutionary genetics, Plant evolution, Polyploidy in plants

How different parental sex chromosome systems affect allopolyploidization is yet unknown. Here, the authors assemble the genomes of a female allotetraploid weeping willow (Salix babylonica) and a male diploid S. dunnii, and explore the transition from XY system to ZW system following allopolyploidization.

Introduction

Polyploidy is an important feature of genome evolution1,2, and although highly degenerate sex chromosomes might act as a barrier to polyploidy3, polyploidy in lineages with less differentiated sex chromosomes has been observed (e.g., diecious plants, amphibians, and fishes, etc.)1,4,5. Polyploidization presents several interesting questions in the context of sex chromosomes3,4,6. For example, how does the polyploid lineage overcome unbalanced sex chromosome dose effects? In autopolyploid lineages, where both genome copies arise from the same species7, polyploid progeny could inherit the sex chromosomes from the diploid ancestor8. However, allopolyploidy, where hybridization between species combines one duplicated copy of each ancestral genome, could lead to diverse sex chromosome combinations when the diploid ancestors carry different sex chromosome types (XX/XY, male heterogametic and ZW/ZZ, female heterogametic), or even the same sex chromosome type but on different chromosomes9,10. The increased sex chromosome complement in polyploids could disrupt the sex-determination process, leading to the loss of dioecy, such as the reversal to monoecy observed in polyploid persimmon11–14. Alternatively, the allopolyploidization from lineages with competing sex chromosome systems could lead to transitions between sex-determining systems, but how this occurs, and how the allele dosage effects of competing sex chromosome systems are overcome, remains an open question.

Allopolyploidization also raises interesting questions about how one of the duplicated sex chromosome pairs reverts to autosomal inheritance. Most cases of polyploidization are followed by rediploidization, sometimes instantaneously from the point of polyploidization, but more often rediploidization is a gradual process15,16. Rediploidization presents peculiar issues for duplicated sex chromosomes, as only one pair is retained as the sex-determining chromosomes4,6, as has been observed in Rumex acetosella17, although see the ZZZW/ZZZZ system in autotetraploid Salix polyclona8. Presumably, the superfluous pair of sex chromosomes transition into autosomes, but the XY or ZW chromosomes of a pair may carry different gene content, and some genes might be lost in the rediploidization process4. For example, doublesex and mab-3 related transcription factor (DMRT1) gene copies, male-related autosomal genes, were pseudogenized multiple times independently in Xenopus following polyploidization in order to balance sex determination18. However, the retention and loss of sex chromosomes during allopolyploidization, and how this affects gene content and sex determination, remains largely unexplored due to the previous lack of haplotype-resolved genome assemblies of polyploid diecious plants.

The weeping willow (Salix babylonica), native to eastern Asia, is a frequently cultivated ornamental tree in the northern hemisphere19,20. The species is tetraploid (2n = 76) and a member of a tetraploid group of Salix21, that likely arose from crosses between species from the Salix- and Vetrix-clade within the genus Salix according to phylogenetic incongruence between the chloroplast and nuclear trees of Salix10,20,22. Diploid species within the Salix-clade have XY sex chromosomes on chromosome 7, whereas species in the Vetrix-clade have XY or ZW sex chromosomes on chromosome 1523, with 15XY inferred as the ancestral sex chromosomes of the clade23–26. The weeping willow is dioecious and produces viable seeds22,27, suggesting that it also has sex chromosomes and has overcome the allele dosage effect of the two different sex chromosome systems of its ancestors. This system provides an opportunity to understand how allopolyploidization resulting from the hybridization of two species with different sex chromosome systems resolves into stable dioecy.

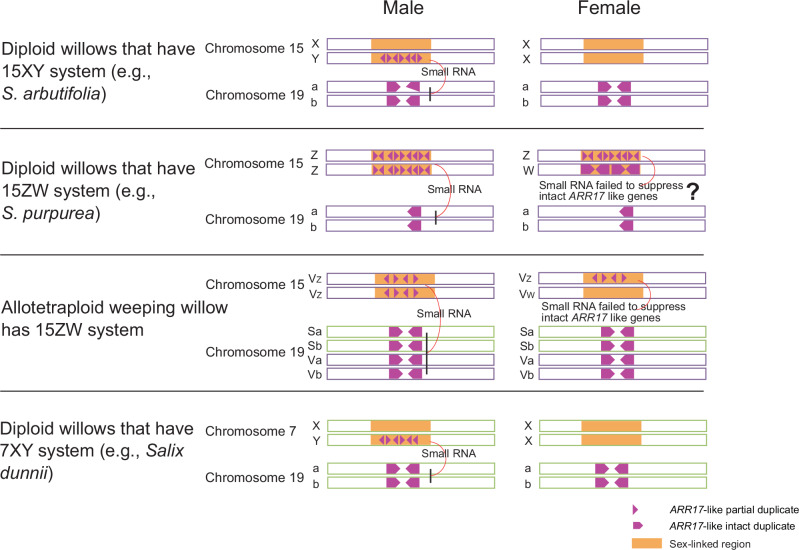

The genetic control of the sexes in the Salicaceae is well known from poplars (Populus), the sister genus of Salix. In the male-specific region of the Y chromosome, duplicates of the partial ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR 17 (ARR17) orthologue produce small RNAs (sRNA) that silence the intact ARR17-like gene of poplar sex chromosome 19, thereby indirectly activating PISTILLATA (PI, required for stamen development) and suppressing female development28–30. Partial ARR17-like duplicates have also been found in the Y-linked regions (7Y in the Salix-clade and 15Y in the Vetrix-clade) of willows, which can produce sRNAs to suppress the expression of intact ARR17-like genes on chromosome 1924. The diploid 15XY and 15ZW species of the Vetrix-clade inherited the sex-linked region (SLR) from their 15XY ancestor, with the W- and X-SLR coming from the ancestral X-SLR, and Z- and Y-SLR from the ancestral Y-SLR. The ancestral Y-linked genes are close to partial ARR17-like duplicates23–25, and two ancestral X-Y homologous gene pairs diverged in the progenitor of the Vetrix-clade25.

To understand how different parental sex chromosome systems affect allopolyploidization, we assemble a haplotype-resolved chromosome-level genome of a female allotetraploid weeping willow and a haplotype-resolved genome of a male diploid S. dunnii of the Salix-clade with an XY system on chromosome 7. We previously assembled a female genome, which includes 7X, of S. dunnii based on Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) long reads31, and the work reported here includes the 7Y chromosome. We show that the weeping willow inherited two alternative sex chromosome systems, 7XX from a female ancestor of the Salix-clade, and most likely 15XY from a male ancestor of the Vetrix-clade. Following allopolyploidization, the Salix-clade 7X sex chromosomes reverted to autosomal inheritance, while the Vetrix-clade 15XY sex chromosome system gave rise to a 15ZW sex chromosome system to form stable dioecy and female heterogamety observed in the weeping willow today.

Results

Genome assembly and annotation

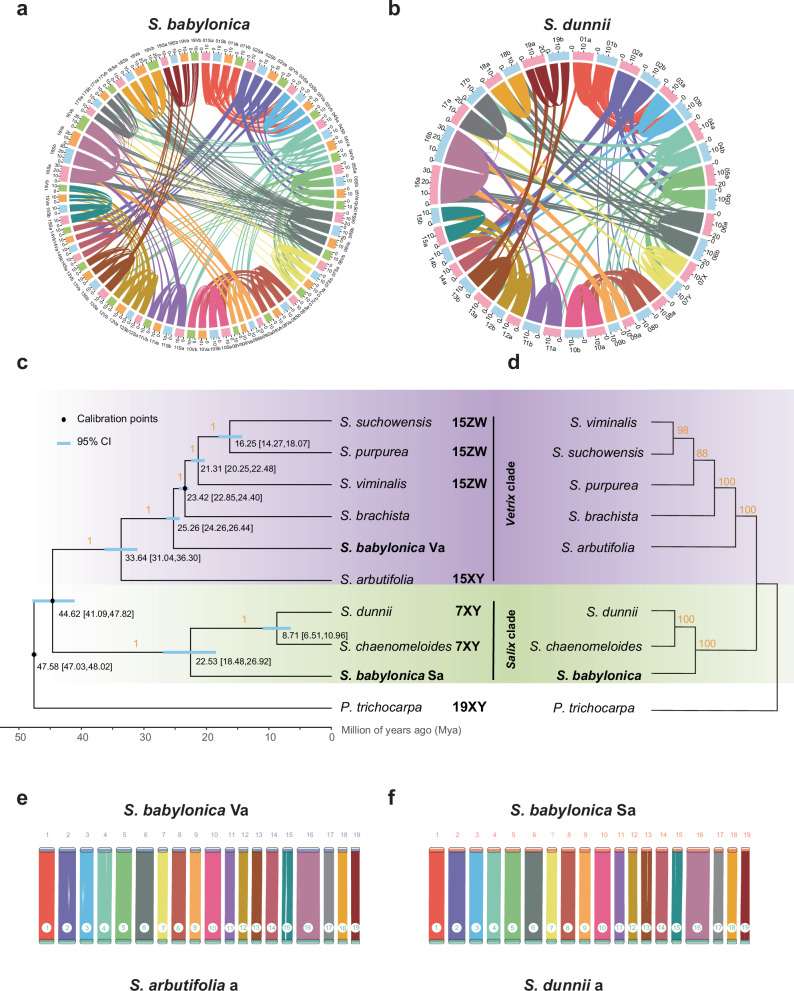

From a single female S. babylonica, we generated 46 Gb (64X) of HiFi reads, 79 Gb (94X) of Illumina reads, and 164 Gb (254X) of Hi-C reads (Supplementary Table 1). From a single male S. dunnii individual (with XY sex chromosomes on chromosome 731), we generated 39 Gb (112X) of HiFi reads, 40 Gb (108X) of Illumina reads, and 37 Gb (107X) of Hi-C reads (Supplementary Table 1). After assembling each species separately with the PacBio HiFi and Hi-C reads, we used Illumina short reads to correct errors for each genome. The S. babylonica assembly was 1286 Mb, comprised of 102 contigs (contig N50 = 16 Mb) (Table 1), with a final chromosome-scale assembly of 76 pseudochromosomes and gap-free sex chromosomes (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1, and Supplementary Table 2). We obtained an S. dunnii assembly of 696 Mb, comprised of 40 contigs (contig N50 = 19 Mb) and a final gap-free chromosome-scale S. dunnii genome with 38 pseudochromosomes (Fig. 1b, Table 1, and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Statistics of the S. babylonica and S. dunnii genome assemblies

| S. babylonica | S. dunnii | |

|---|---|---|

| Total assembly size (Mb) | 1286 | 696 |

| Total number of contigs | 102 | 40 |

| Maximum contig length (Mb) | 32 | 37 |

| Minimum contig length (Kb) | 64 | 156 |

| Contig N50 length (Mb) | 16 | 19 |

| Contig N50 count | 33 | 16 |

| Contig N90 length (Mb) | 10 | 13 |

| Contig N90 count | 70 | 33 |

| Gap number | 24 | 0 |

| GC content (%) | 34 | 33 |

| Gene number | 123,231 | 65,485 |

| Repeat content (%) | 41 | 48 |

Fig. 1. Origin and divergence time estimation of S. babylonica subgenomes.

a Synteny of female S. babylonica genome. b Synteny of male S. dunnii genome. c Inferred phylogenetic tree and divergence times based on nuclear genome sequences of eight willows and the outgroup P. trichocarpa. Blue node bars are 95% confidence intervals, and the black nodes are three fossil calibration points32. Black numbers marked around nodes represent divergence time. Orange numbers marked above branches represent support values. 19XY, 7XY, 15XY and 15ZW on the right represent different sex-determination systems. d Inferred phylogenetic tree based on chloroplast genome sequences of the nine species. Numbers marked on the tree represent bootstrap values (Supplementary Fig. 5). e Synteny between Va haplotype of S. babylonica and a haplotype of S. arbutifolia. f Synteny between Sa haplotype of S. babylonica and a haplotype of S. dunnii. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

For the S. babylonica assembly, about 98.91% of Illumina short reads and 99.43% HiFi reads could be aligned back to the genome assembly, and 99.41 and 95.79% of the assembly was covered by at least 20X reads, respectively. Similarly, about 99.95% of Illumina short reads and 99.86% of HiFi reads were mapped back to the S. dunnii genome assembly, and around 99.18 and 99.86% of the assembly was covered by at least 20X reads, respectively. BUSCO analysis suggested that 1422 (98.8%) highly conserved core proteins were identified in the S. babylonica genome, and 1416 (98.4%) highly conserved core proteins in the S. dunnii genome (Supplementary Table 3).

We recovered 525.5 Mb (40.86%) and 333.7 Mb (47.92%) of repetitive sequences in the S. babylonica and S. dunnii genomes (Supplementary Data 1). Among them, long terminal repeats (LTRs) represented the most common component, accounting for 19.37% of the S. babylonica genome and 24.78% of the S. dunnii genome (Supplementary Data 1). A total of 123,231 genes (116,745 mRNAs excluding alternative splicing, 2428 transfer RNAs (tRNAs), 1528 ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), and 2530 unclassifiable noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs)) were identified in S. babylonica (Supplementary Data 2). We obtained 65,485 genes, (61,872 mRNAs, 1139 tRNAs, 1102 rRNAs, and 1372 ncRNAs) in S. dunnii (Supplementary Data 3). The average S. babylonica protein-coding gene is 3421.6 bp long, with an average of 5.9 exons, and the average S. dunnii protein-coding gene is 3683.4 bp long, with an average of 6.4 exons (Supplementary Table 4). By combining several strategies, we were able to match the vast majority of our predicted genes to predicted proteins in public databases such as GO, KEGG, and Swiss_Prot (Supplementary Data 4), and only 1.77% of S. babylonica protein-coding genes and 2.24% S. dunnii protein-coding genes were not annotated.

Phylogenetic analysis and divergence time estimation

We confirmed that S. babylonica is a tetraploid based on flow cytometry and an allotetraploid according to our k-mer results (Supplementary Figs. 3,4). To determine the ancestry of the two subgenomes (S from Salix-clade and V from Vetrix-clade) within the genus Salix, we obtained 5146 single-copy orthologs from our S. babylonica Salix (Sa) and Vetrix (Va) haplotypes, and a haplotype genome assembly from S. dunnii, as well as from six other willows with available genomes, and from the outgroup Populus trichocarpa (Supplementary Table 5). The resulting species tree is broadly consistent with previous studies and resolves the Salix- and Vetrix-clade24,25,31,32.

Importantly, our results show that the V subgenome of S. babylonica originated from an ancestor in the Vetrix-clade and diverged from the S. brachista-S. viminalis-S. purpurea-S. suchowensis clade about 25.26 Mya (million years ago), while the S subgenome originated from an ancestor in the Salix-clade, diverging from the S. dunnii-S. chaenomeloides about 22.53 Mya (Fig. 1c, e). We also estimated the phylogenetic tree from chloroplast genomes, which suggests that the maternal ancestor of S. babylonica originated from the Salix-clade33 (Fig. 1d, f and Supplementary Fig. 5).

According to the inferred time of transposable elements divergence (see methods) between the subgenomes of S. babylonica, the estimated allotetraploidization time is around 6.2–2.91 Mya (Supplementary Fig. 6), suggesting that S. babylonica may have emerged during this period. Since the genus Salix contains >400 species34 and S. babylonica is nested in a tetraploid group in a plastome tree21, we cannot conclude whether the parental species of weeping willow are extant or extinct based on currently available genomes.

Identification of the sex-determination system

We used 4417.1 million clean Illumina reads from 20 females and 20 males of allotetraploid weeping willow (97−135.8 million reads per individual, mean 110.4, Supplementary Data 5), to identify sex-specific-k-mers, and found a significant enrichment of female-specific k-mers on chromosome 15Va, between 5.32–9.71 Mb (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 7a), consistent with a W chromosome. We did not observe a significant enrichment of male-specific k-mers on any chromosome of S. babylonica, as expected in a female-heterogametic system (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Our results from the chromosome quotient (CQ) method35 are concordant with the k-mer analysis, and we detected the sex-linked region (SLR) between 5.28–9.69 Mb on chromosome 15Va, with mean M:F (male: female) CQ (chromosome quotient) = 0.27, consistent with a W chromosome. The M:F CQ of 2.83–7.88 Mb of chromosome 15Vb had a mean of 2.1, consistent with a Z chromosome. We did not find significant CQ signals or partial ARR17-like duplicates on chromosomes 15Sa and 15Sb (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Data 6). These results suggest that weeping willow has a female heterogametic system on chromosome 15, 15Va and 15Vb are W (15VW) and Z (15VZ) chromosomes, respectively.

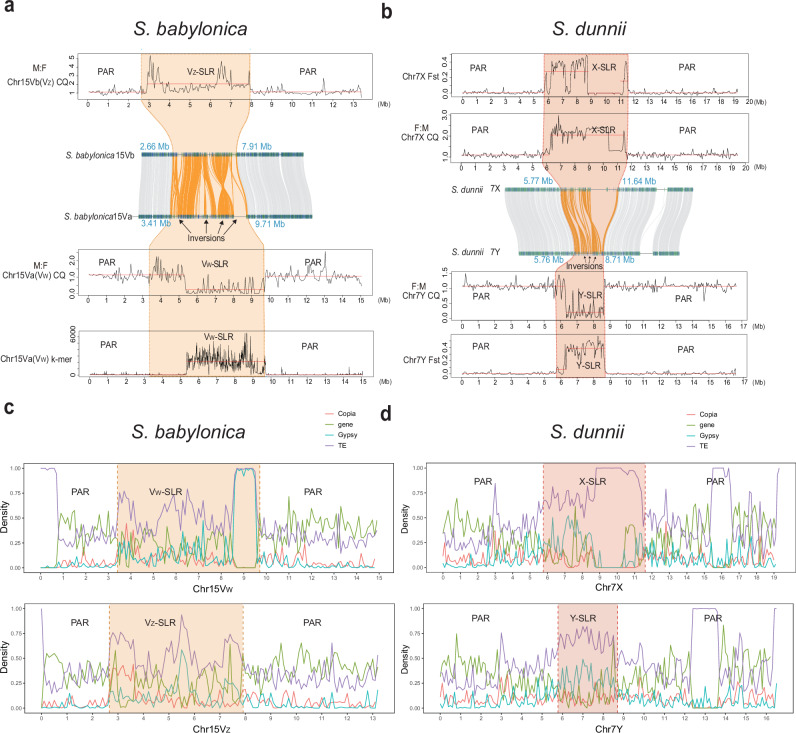

Fig. 2. Sex-linked regions in S. babylonica and S. dunnii.

a CQ (male vs. female alignments), collinearity and female-specific k-mer results for S. babylonica sex chromosomes 15Vb(VZ) and 15Va(VW). Supplementary Fig. 7a shows k-mer results of the whole genome. The collinearity results between two sex chromosomes show four inversions. b Male-female Fst, CQ (female vs. male), and collinearlity results for S. dunnii sex chromosomes 7X and 7Y. The collinearity results between two sex chromosomes show three inversions. c Gene and transposable elements (TEs) landscape of S. babylonica sex chromosomes (100-kb windows). d Gene and TEs landscape of S. dunnii sex chromosomes (100-kb windows). SLR: sex-linked region. PAR: pseudoautosomal region. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Our synteny analysis revealed four inversion events between the 15VW and 15VZ chromosomes of S. babylonica, and further confirmed a 6.3 Mb W sex-linked region (SLR) between 3.41–9.71 Mb on 15Va, with a corresponding 5.25 Mb Z-SLR between 2.66–7.91 Mb on 15Vb (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 9). The other regions of the two chromosomes form pseudoautosomal regions (PARs) with 8.74 Mb in 15Va and 8.13 Mb in 15Vb, respectively.

S. dunnii has a male heterogametic system on chromosome 731. The F:M (female: male) CQ analysis revealed a 5.35 Mb region, spanning 6.15–11.5 Mb on 7X, with mean CQ = 2.03. We also observe a 2.35 Mb region spanning 6.25–8.6 Mb, on 7Y with mean CQ = 0.22 (Fig. 2b). We obtained 6,687,746 and 6,705,953 SNPs for haplotype a (including 7X) and b (including 7Y) of S. dunnii, and used these to calculate the FST values between the 18 male and 20 female genomes. Changepoint analyses detected significantly higher FST values between 5.77–11.64 Mb on chromosome 7X and 5.76–8.71 Mb on chromosome 7Y than in other regions (PARs), which covered the regions identified by CQ. We identified three inversion events between the X and Y in S. dunnii using synteny analysis (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 10), which are all within the region identified as sex-linked by FST analysis. SLRs of both S. babylonica and S. dunnii show low gene density and high repetitive sequence density (Fig. 2c, d and Supplementary Data 7).

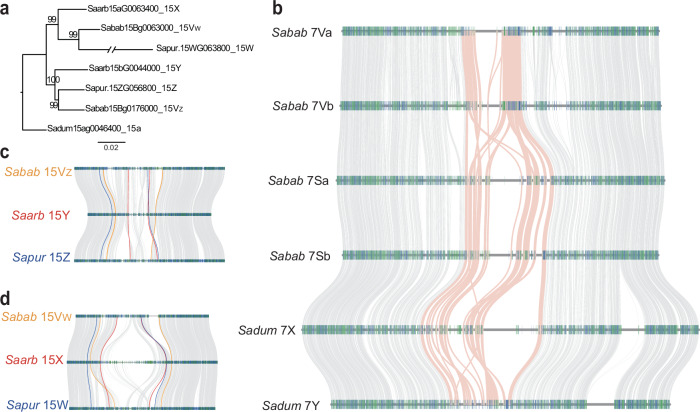

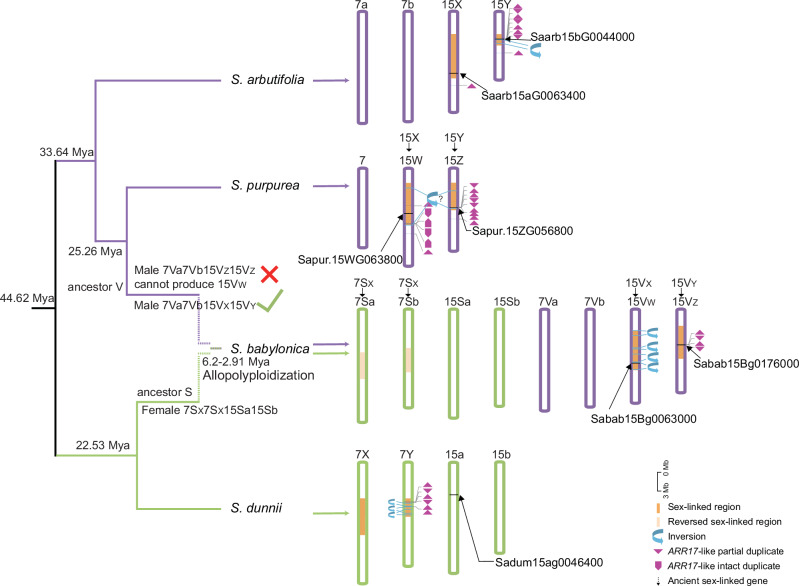

Evolutionary origin of Salix babylonica

The nuclear and chloroplast trees suggest that the female ancestor of S. babylonica arose from the Salix-clade, while the male ancestor most likely came from the Vetrix-clade. The Vetrix-clade contains both 15X15X/15X15Y and 15Z15W/15Z15Z species, however phylogenetic analysis of ancestral sex-linked genes within the Vetrix-clade reveals that alleles cluster by gametologs, with one clade comprising of S. arbutifolia 15X, S. babylonica 15 W and S. purpurea 15 W, and another clade comprising of S. arbutifolia 15Y, S. babylonica 15Z and S. purpurea 15Z (Fig. 3a). This result suggests that S. babylonica inherited 15X and 15Y, which correspond to 15 W and 15Z respectively, or 15 W and 15Z from its Vetrix-clade ancestor. A diploid male (15Z15Z) in a female heterogametic species can only produce 15Z gametes, and cannot produce 15W, which must come from a female, while a diploid male (15X15Y) in male heterogametic species can produce unreduced gametes with 15X and 15Y. This suggests that the 15XY is the most likely sex chromosome system for the male S. babylonica Vetrix-clade ancestor. Therefore, this suggests that the ancestral Vetrix-clade 15Y (hereafter, 15VY) transitioned to 15Z (hereafter, 15VZ) in S. babylonica, and 15X (hereafter, 15VX) transitioned to 15W (hereafter, 15VW) (Figs. 1c, d, 2a, 3a).

Fig. 3. Evolutionary relationships, genomic composition, and collinearity of sex chromosomes in different sex-determination systems.

a The phylogenetic tree is reconstructed from ancestral sex-linked genes proposed by ref. 25. b Collinearity and genomic composition of S. babylonica 7Va, 7Vb, 7Sa, 7Sb and S. dunnii 7X, 7Y. Pink indicates the collinear regions of 7X-SLR, 7Y-SLR, and 7Sa, 7Sb, 7Va, and 7Vb. c Collinearity and genomic composition of the S. babylonica 15VZ-SLR, the S. arbutifolia 15Y-SLR and the S. purpurea 15Z-SLR. Orange, red, and blue represent the sex-linked regions in Sabab, Saarb, and Sapur, respectively. d Collinearity and genomic composition of the S. babylonica 15VW-SLR, the S. arbutifolia 15X-SLR, and S. purpurea 15W-SLR. Orange, red, and blue represent the sex-linked regions in Sabab, Saarb, and Sapur, respectively. Sabab: S. babylonica; Sadum: S. dunnii; Saarb: S. arbutifolia; Sapur: S. purpurea. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To better understand the transition from 15VXVY in the S. babylonica male Vetrix-clade ancestor to the current S. babylonica 15VZVW sex chromosome system, we examined the distribution of ARR17-like genes in S. arbutifolia (15X15X/15X15Y) and S. babylonica, which are involved in sex determination in Salix and Populus24,28. We found ARR17-like partial duplicates on 15Y-SLR of S. arbutifolia and on 15VZ-SLR of S. babylonica (Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Data 6), while they are absent in 15X-SLR and 15VW-SLR of these two species. This further confirmed the transitions (15VX→15VW and 15VY→15VZ) in S. babylonica. The 15 W and 15Z of diploid S. purpurea also arose from ancestral Vetrix-clade 15X and 15Y, respectively, but its 15W has accumulated intact ARR17-like genes25.

We also assessed collinearity between the sex chromosomes (7X and 7Y) of S. dunnii and the homologous autosomes (7Sa, 7Sb, 7Va, and 7Vb) of S. babylonica. Our results suggest that 7X of the female Salix-clade ancestor has reverted to autosomal inheritance in S. babylonica (Figs. 1c, d, 3b). There are inversions between the sex chromosomes of S. dunnii, but the gene order on autosome 7Sa and 7Sb of S. babylonica is most similar to 7X of S. dunnii, again consistent with a female Salix-clade ancestor (Fig. 3b). In addition, the number of genes in the 7Sa&Sb regions syntenic with 7X-SLR is between those in 7X-SLR and 7Va&Vb region (autosome) syntenic with 7X-SLR, supporting that 7Sa&Sb are derived from 7SX (Supplementary Data 7).

Allopolyploidization from these ancestors could have involved diploid unreduced gametes (Supplementary Fig. 12). Alternatively, crosses between two tetraploid ancestors is also possible, though arguably less likely7,36. The first scenario suggests that the unreduced gametes from the male Vetrix-clade ancestor gametes were likely 15X15Y (hereafter, 15VX15VY) (skipping meiosis I), or 15X15X (hereafter, 15VX15VX) or 15Y15Y (hereafter, 15VY15VY) (skipping meiosis II). The unreduced gametes from the female Salix-clade ancestor were likely 7X7X (hereafter, 7SX7SX) (Figs. 1d, 3b). These female and male gametes can produce 7SX7SX15VX15VY (now 7Sa7Sb15VZ15VW) females and 7SX7SX 15VY15VY (now 7Sa7Sb15VZ15VZ) males.

Evolution of the sex-linked region

In S. babylonica, gene counts are similar between the VW-SLR (323 protein-coding genes) and VZ-SLR (306 protein-coding genes), though their total lengths (VW-SLR 6.31 Mb vs. VZ-SLR 5.25 Mb) and repeat lengths (VW-SLR 3.86 Mb vs. VZ-SLR 2.96 Mb) differ (Supplementary Data 7). This suggests that sex chromosome turnover or/and polyploidization inhibited substantial heteromorphy of VZ and VW4. We compared the collinearity and genomic composition in S. babylonica (15VZVW), S. purpurea (15ZW), and S. arbutifolia (15XY) (Fig. 3c, d), and our results indicate that these regions evolved independently in different sex chromosomes despite having the same origin. The S. babylonica 15VZ-SLR, S. purpurea 15Z-SLR, and S. arbutifolia 15Y-SLR, constitute 39.24, 32.77, and 16.48% of their Z or Y chromosome. The S. babylonica 15VW-SLR, S. purpurea 15W-SLR, and S. arbutifolia 15X-SLR, constitute 41.95, 42.95, and 43.66% of their W or X chromosome (Supplementary Data 7). Furthermore, we detected different inversions in the sex chromosomes of the three species (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 9).

Fig. 4. Hypothetical origination of S. babylonica and evolution of sex-linked regions (SLRs) in relevant diploid willows.

Purple represents genomic components of S. babylonica the Vetrix-clade ancestor, that likely has 15XY sex chromosomes, while green represents components from the Salix-clade ancestor with 7XY sex chromosomes. The chromosomes on the right use the scaled real physical length, and dark yellow or light yellow represents sex-linked or reversed sex-linked regions. Purple triangles indicate partial ARR17-like duplicates (the tip is the end of the duplicate), and purple arrows indicate intact ARR17-like duplicates (the tip is the end of the gene). Blue arrows indicate inversions on SLRs. Genes marked by the black arrows are ancestral sex-linked genes that were used in Fig. 3a.

In S. dunnii, the X-SLR (5.87 Mb) is larger than the Y-SLR (2.95 Mb). Similarly, the S. arbutifolia X-SLR is larger (7.06 Mb) than the Y-SLR (1.81 Mb)25. There are 128 and 96 protein-coding genes within X-SLR and Y-SLR in S. dunnii (Supplementary Data 3), and the X-SLR contains a total of 2.72 Mb more repeat sequences than the Y-SLR (Supplementary Data 7). We also identified 31 X-SLR-specific genes, of which 13 are tandem duplicates, and 16 Y-SLR-specific genes, of which three are tandem duplicates (Supplementary Data 8). Therefore, the accumulation of repeat sequences and specific tandem duplications may contribute to the longer X-SLR than Y-SLR in S. dunnii, which is consistent with S. arbutifolia25. This result suggests that the XY sex chromosomes in willows may be somewhat different from other XY plant sex chromosome systems37,38, with a longer Y-SLR compared to the corresponding X-SLR counterpart.

Our analysis reveals ARR17-like partial duplicates near or within the inversions between 7X and 7Y of S. dunnii, the inversions between 15VZ and 15VW of S. babylonica, and the inversion between 15X and 15Y of S. arbutifolia (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Data 9). It is difficult to determine whether the detected inversions are a catalyst or consequence of recombination suppression39, but these results suggest that ARR17-like partial duplicates are associated with sex-linked inversions. This is either because recombination has been selectively suppressed in these regions to maintain sex-specific segregation patterns of the partial ARR17-like duplicates, or alternatively, the inversions may have resulted from the fact that these loci are in areas of the pericentromeric region with low recombination (Supplementary Figs. 13, 14).

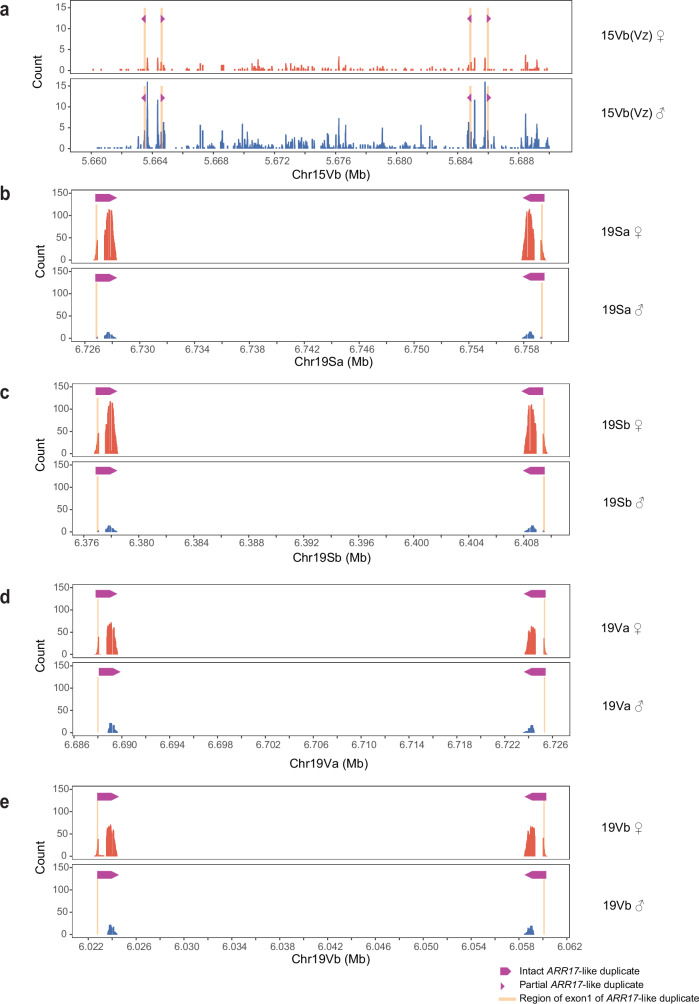

Sex-determination mechanism in S. babylonica

The ARR17-like sequences play an important role in the sex determination of Salicaceae. The partial ARR17-like duplicates on Y-SLRs of diploid S. chaenomeloides (7XY) and S. arbutifolia (15XY) can produce sRNA to silence four intact ARR17-like genes on chromosome 19 to determine maleness24,25. S. dunnii likely shows a similar strategy. Therefore, we used 1181.68 million clean RNA-Seq Illumina reads (56.42–77.76 million reads per individual, mean 65.65) to estimate the expression of intact ARR17-like and PI-like genes, and 43.24 million sRNA reads (1.70–3.52 million reads per individual, mean 2.40) surrounding the partial ARR17-like duplicates of weeping willow flower buds from three stages. We identified more sRNAs in the partial ARR17-like duplicate (exon1) region and its upstream region in male flower buds than in female flower buds of weeping willow (Fig. 5a, stage 2 and Supplementary Fig. 15, stage 1 and 3). Consistent with this, we found that all of exon1 of intact ARR17-like genes were expressed in female flower buds, with significantly lower or no expression in male flower buds of weeping willow (Fig. 5b–e). We also detected the accumulation of sRNAs in intact ARR17-like gene regions on chromosomes 19Va, 19Vb, 19Sa, and 19Sb in males (Supplementary Fig. 16). Furthermore, the PI-like genes were only expressed in male flower buds (Supplementary Fig. 17). This result suggests that sRNAs produced by partial ARR17-like duplicates of two 15VZs alleles may inhibit eight intact ARR17 genes on the four homologs of chromosome 19, activating the PI-like genes and leading to the production of male individuals (Fig. 6). Our results suggest a dose effect related to sex determination, with one 15VZ carrying partial ARR17-like duplicates in females insufficient to inhibit intact ARR17-like genes, similar to the sex-determining mechanism of chicken40. S. babylonica 15VW could also acquire a female factor to inhibit sRNA production of partial ARR17-like duplicates, but more assemblies of allotetraploid willows are needed to detect whether such factor(s) exist.

Fig. 5. Expression patterns of ARR17-like duplicates in female and male flower buds of weeping willow (stage 2).

a Transcript level of partial ARR17-like duplicate sRNA and surrounding regions on sex chromosome 15VZ. The orange area indicates exon1 of ARR17-like copies. b–e Transcript level of intact ARR17-like genes on Chr19Sa, Chr19Sb, Chr19Va and Chr19Vb. Purple triangles indicate partial ARR17-like duplicates (the tip is the end of the duplicate). The purple arrows show the intact ARR17-like duplicates (the tip is the end of the gene). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Fig. 6. Hypothetical model for ARR17-like duplicates and sex determination in willows.

One Z/Y sex chromosome carrying partial ARR17-like duplicates can produce sRNA to inhibit the expression of four intact ARR17-like genes, but six or eight intact ARR17-like genes can overcome the influence of one Z. Purple triangles within sex-linked regions indicate partial ARR17-like duplicates (the tip is the end of the duplicate). Purple arrows show intact ARR17-like duplicates (the tip is the end of the gene). The relevant data can be found in the Supplementary Data 6.

Dosage compensation in different sex chromosomes

We used 854.73 million clean Illumina reads of weeping willow catkins (69.86–73.08 million reads per individual, mean 71.23), 410.10 million clean Illumina reads of S. arbutifolia catkins (33.86–34.52 million reads per individual, mean 34.17), and 380.73 million clean Illumina reads of S. dunnii catkins (30.44–32.89 million reads per individual, mean 31.73) to observe the expression level between SLRs and autosomes. We observed degeneration signals in the SLRs of the 15VZ and 15VW of S. babylonica, the 15X and 15Y of S. arbutifolia, and the 7X and 7Y of S. dunnii. Gene density was lower in all these SLRs compared to the corresponding PARs, while repetitive elements density was higher (Fig. 2c, d and Supplementary Data 7). The W-SLR and Y-SLRs have lost genes compared with their orthologous autosomes, i.e., the S. babylonica 15VW-SLR lost 2.84% genes, the S. arbutifolia 15Y-SLR lost 11.49% genes, and the S. dunnii 7Y-SLR lost 1.22% genes (Supplementary Table 6). We also found evidence of gene loss from Z-SLRs and X-SLRs. The S. babylonica 15VZ-SLR lost 3.9% genes, the S. arbutifolia 15X-SLR lost 9.20% genes, and the S. dunnii 7X-SLR lost 1.22% genes. The VZ-SLR lost more genes than the VW-SLR in S. babylonica, which may be due to the turnover (Y→Z) mentioned above.

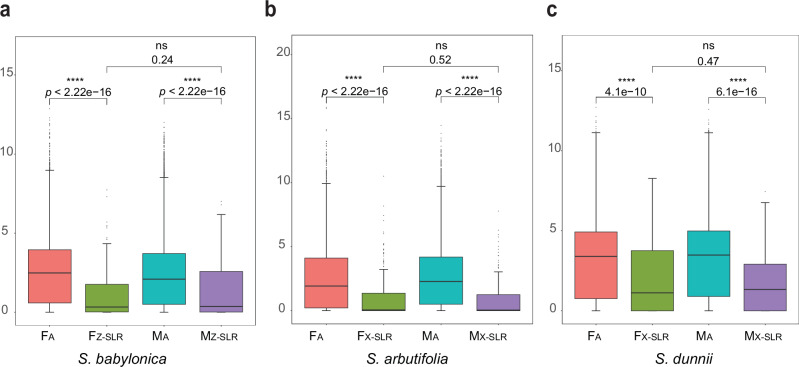

Overall, the expression values between sexes are similar but significantly lower (Wilcox test *: p ≤ 0.05) than in autosomes among 15ZW (male 15Z-SLR15Z-SLR vs female 15Z-SLR), 15XY (female 15X-SLR15X-SLR vs male 15X-SLR), and 7XY (female 7X-SLR7X-SLR vs male 7X-SLR) (Fig. 7). Based on these results, we revealed similar incomplete dosage compensation patterns in S. babylonica, S. arbutifolia, and S. dunnii.

Fig. 7. Dosage compensation pattern in different sex-linked regions of willows.

The expression of SLR and autosomal genes in a S. babylonica (gene number: FA (56063), FZ-SLR (306), MA (56063), MZ-SLR (306)), b S. arbutifolia (gene number: FA (28097), FX-SLR (238), MA (28097), MX-SLR (238)), and c S. dunnii (gene number: FA (29623), FX-SLR (128), MA (29623), MX-SLR (128)). F and M represent females and males. Each sex contained three independent biological replicates. A and -SLR represents autosome and sex-linked region. Significance based on two-sided Wilcox test (ns: p > 0.05, *: p ≤ 0.05, **: p ≤ 0.01, ***: p ≤ 0.001, ****: p ≤ 0.0001). Box edges indicate upper and lower quartiles, centerlines indicate median values, and whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

Although sex chromosomes were once thought to be an obstacle to polyploidization3, it is increasingly clear that polyploidy can arise from diploid ancestors with sex chromosomes in both plants and animals4,9,41. How these polyploid lineages overcome the complex and unbalanced allelic combinations of sex determination alleles to establish stable dioecy is not yet known. Previous studies did not provide direct evidence that diecious plants overcome the polyploidy limit14,42,43. Diospyros kaki and Mercurialis annua, both male heterogametic systems, reverted to non-diecious sex-determination systems after genome doubling14,42, while the diploid and polyploid ancestors of the octoploid diecious Fragaria chiloensis were likely hermaphroditic43. For other polyploids with sex chromosomes, such as Rumex acetosella, a male heterogametic tetraploid, genomic resources are not yet available to investigate sex chromosome evolution and its ancestral species17.

We assembled haplotype-resolved genomes of female allotetraploid S. babylonica and male diploid S. dunnii. Our nuclear and chloroplast genome sequences trees indicate that S. babylonica has a female ancestor from the Salix-clade and a male ancestor from the Vetrix-clade within the Salix genus and that allopolyploidization occurred between 6.2–2.91 Mya, long before plant domestication44. Our results also suggested that sex chromosome turnover (15XY to 15ZW) happened during allopolyploidization.

Similar to its male ancestor, the S. babylonica SLRs are located on chromosome 15Va(15VW) and 15Vb(15VZ) according to k-mer and CQ analysis (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Figs. 7, 8), indicating that only one pair of sex chromosomes was retained6. According to the ancestral sex-linked gene tree, the X-Y homologous gene pair diverged in the ancestor of the Vetrix-clade25, and the genomic distribution and phylogenetic analysis of partial ARR17-like duplicates (Supplementary Fig. 11), the 15VW(15Va) and 15VZ(15Vb) derived from the ancestral 15VX and 15VY chromosomes in the male ancestor, respectively (Figs. 1c, 3a, 4 and Supplementary Figs. 11, 12). The 15W and 15Z chromosomes of diploid S. purpurea were also derived from ancestral 15X and 15Y chromosomes of the Vetrix-clade25, respectively. These results suggest that XY to ZW transitions occurred independently in different willow species.

Early generations of allotetraploid S. babylonica were likely comprised of 7SX7SX15VX15VX and 7SX7SX15VX15VY females (see Sex-determination mechanism in S. babylonica), and 7SX7SX 15VY15VY males. Initially, the two 15VYs in males could potentially undergo homologous recombination, but would only be present together when the maternal gamete contained 15VY, which can only be produced by a female-fertile 7SX7SX15VX15VY genotype (Supplementary Fig. 12). Furthermore, the 7SX7SX15VX15VX genotype can only produce 7SX15VX gametes, which when combined with a male gamete carrying 7SX15VY, would produce 7SX7SX15VX15VY progeny. In this process, recombination was reduced for the 15VX chromosome in females, and ultimately 15VX transitioned to 15VW. Our evidence suggests that the 7SX chromosomes from the female ancestor likely reverted to autosomal inheritance, as evidenced by the similar gene order shared between the resulting autosome and the 7X chromosome of S. dunnii, genomic composition of 7Sa, 7Sb, 7Va, 7Vb, 7X, and 7Y, and the phylogenetic trees (Figs. 1c, 3b and Supplementary Data 7).

The ARR17-like gene (partial and intact) acts as a sex-determination factor in some members of the Salicaceae24,28, and is well known from poplars (Populus), the sister genus of Salix. In the male-specific region of the Y chromosome, partial ARR17-like duplicates ortholog produce sRNAs and silence the intact ARR17-like gene on poplar sex chromosome 19, thereby determining maleness28,29.

Partial ARR17-like duplicates have been found in Y-linked regions in the genus Salix (7Y in the Salix-clade and 15Y in the Vetrix-clade), which can produce sRNAs to suppress the expression of intact ARR17-like genes on chromosome 1923,25 (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Data 6), determining maleness. We observe partial ARR17-like duplicates near or within inversion boundaries in the S. babylonica and S. dunnii sex chromosomes, suggesting that these loci act as sex-determining factors in these species as well. The partial ARR17-like duplicates on the two 15VZ-SLRs of male S. babylonica can produce more sRNA than that on one 15VZ-SLR in females due to dose effects, and likely silenced all the eight intact ARR17-like genes on the four homologs of chromosome 19, thereby determining maleness (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 15). The eight intact ARR17-like genes on chromosome 19 in S. babylonica likely overcame the influence of partial ARR17-like duplicates of one 15VZ-SLR and indirectly suppressed the expression of PI-like genes in females to maintain dioecy (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 17). In diploid S. purpurea (15ZW), the four intact ARR17-like genes on 15W-SLR and two intact copies on chromosome 19 can determine femaleness like in the weeping willow24 (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Data 6). Although it is unclear whether the inversions are the cause of recombination suppression between sex chromosomes or are a consequence of it39, the association with ARR17-like partial duplicates suggests selection to suppress recombination in these regions to maintain sex-specific segregation patterns.

Gene loss from the SLRs of sex chromosomes is common in plants45. Although dioecy is ancestral in willows, and originated at least 47 Mya, sex chromosomes in species within the Vetrix-clade, including S. viminalis (15ZW)46 and S. purpurea (15ZW)47 show low levels of divergence. The results indicate that the 15Y-SLR of S. arbutifolia lost more genes compared with the 15X-SLR (Supplementary Table 6). This signature was also found in other plant sex chromosome systems, including papaya48, Silene latifolia45, and Rumex hastatulus49, and is also a general feature of animal sex chromosomes50. Our results suggest that the 15VW in S. babylonica originated from 15VX, and 15VZ originated from 15VY. It is likely that the gene loss from the 15VZ-SLR in S. babylonica represents the ancestral loss of genes from Vetrix 15VY-SLR.

The loss of genes from W-SLRs and Y-SLRs occurs in many systems following recombination suppression (reviewed by refs. 51–53), and this results in gene dose differences between males and females. Dosage compensation mechanisms have evolved in some species that increase expression levels in the heterogametic sex, potentially restoring expression to levels to the ancestral chromosome pair, and making them equal in both sexes54–57. However, polyploidization complicates dose differences associated with Y and W chromosome degeneration, and it is difficult to predict how polyploidization might affect dosage compensation dynamics. We observe similar patterns of incomplete dosage compensation in S. babylonica (15VZVW), S. dunnii (7XY), and S. arbutifolia (15XY) (Fig. 7), similar to many other plant sex chromosome systems58.

Methods

Plant material

We collected young leaves from a male Salix dunnii (FNU-M-1) and a female S. babylonica (saba01F) plant for genome sequencing. Young leaf, catkin, stem, and root samples for transcriptome sequencing were collected from FNU-M-1 and saba01F, as well as catkins from two other female and three male S. babylonica plants, and one other female S. dunnii plant. In October 2023 (stage 1), December 2023 (stage 2), and February 2024 (stage 3), we collected flower buds from three male and three female individuals of S. babylonica for sRNA sequencing and mRNA sequencing to detect possible sex-determination mechanisms. Samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until total genomic DNA or RNA extraction. We sampled 40 flowering individuals of S. babylonica and dried their leaves in silica-gel for resequencing. Voucher specimens collected for this study are deposited in the herbarium of Shanghai Chenshan Botanical Garden (CSH). Supplementary Data 10 gives detailed information on all the samples. We also downloaded genome sequence data of 38 individuals of S. dunnii published by ref. 31, the genome of S. arbutifolia (with gap-free 15X and 15Y sex chromosomes)25, the genome of S. purpurea (with phased 15Z-SLR and 15W-SLR)47, and other available willows genomes and Populus trichocarpa for relevant analyses (Supplementary Table 5).

Ploidy determination

The ploidy of saba01F was measured by flow cytometry, using diploid Salix dunnii (2x = 2n = 38)31 as an external standard. The assay followed the protocol of ref. 59. The leaf tissue was incubated for 80 min in 1 mL LB01 buffer and chopped with a razor blade. The homogenate was then filtered through a 38-μm nylon mesh and treated with 80 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI) and 80 μg/mL RNase followed by 30 min incubation on ice to stain the nuclei. DNA content measurements were done in a MoFlo-XDP flow cytometer and evaluated using Summit v.5.2 (Beckman Coulter Inc.). The ploidy level was calculated as:

| 1 |

Determination of allo- or autotetraploid origin in weeping willow

We used jellyfish version 2.3.060 to construct k-mer frequency distributions of saba01F based on PCR-free Illumina short reads, with k-mer length set to 21. Genomescope 2.061 was run with 21-mer to distinguish between autotetraploid and allotetraploid origin based on the patterns of nucleotide heterozygosity. Allotetraploids are expected to have a higher proportion of aabb than aaab, while autotetraploids have a higher proportion of aaab8,61.

Genome sequencing

For Illumina PCR-free sequencing of FNU-M-1 and saba01F, and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of all 40 weeping willow individuals, their total genomic DNAs were extracted using the Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). PCR-free sequencing libraries were generated using the Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Library Preparation Kit (Illumina) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Paired-end libraries were constructed for all 40 samples for WGS. These libraries were sequenced on an Illumina platform (NovaSeq 6000) by Beijing Novogene Bioinformatics Technology (hereafter Novogene).

The Hi-C library was prepared following standard procedures62. In brief, the leaves from FNU-M-1 and saba01F were fixed with a 4% formaldehyde solution. Subsequently, cross-linked DNA was isolated from nuclei. The restriction enzyme MboI was then used to digest the DNA, and the digested fragments were labeled with biotin, purified, and ligated before sequencing. Hi-C libraries were controlled for quality and sequenced on NovaSeq 6000 by Novogene.

For PacBio HiFi libraries and sequencing, total genomic DNA was extracted using the CTAB method. PacBio large insert libraries were prepared with SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0. These libraries were sequenced by Novogene using the PacBio Sequel II platform.

RNA extraction and library preparation

Total mRNA was extracted from young leaves, female and male catkins, stems and roots of S. dunnii and weeping willow, and female and male buds (three stages, see Plant material) of weeping willow using the CTAB method. RNA integrity was assessed using the Fragment Analyzer 5400 (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Libraries were generated using NEBNext® UltraTM RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (NEB, USA) following the manufacturer’s recommendations, and sequencing was performed on an Illumina Novaseq 6000 by Novogene.

For sRNA sequencing, total RNA from flower buds (three stages) of S. babylonica was extracted using RNAprep Pure Plant Plus Kit (Tiangen, China). Adapters were ligated to the ends of the sRNA, and then the first strand of cDNA was synthesized after hybridization with reverse transcription primers. PCR enrichment was used to generate the double-stranded cDNA library. Libraries with insertions of 18–40 bp were ready for sequencing after purification and size selection. sRNA sequencing was performed on an Illumina Novaseq 6000 by Novogene.

Genome assembly

Hifiasm63 was used to assemble initial genomes based on PacBio HiFi reads, with the resulting haplotype assemblies used for subsequent analysis. For chromosome-level genome assembly, the Hi-C reads were first aligned to the haplotype contig genome using Juicer64. Subsequently, a preliminary Hi-C-assisted chromosome assembly was carried out using 3d-dna65. This was followed by manual inspection and adjustment using Juicebox66, primarily focused on refining chromosome boundaries, removing incorrect insertions, adjusting orientations, and rectifying assembly errors. To optimize the assembly further, gap filling based on HiFi reads was performed using the LR_Gapcloser67. Additionally, a two-round polishing approach using Nextpolish68 was employed for genome base correction utilizing our short-read data.

We obtained chromosome-scale, haplotype-resolved genome assemblies of S. babylonica and S. dunnii. Although the majority of chromosomes exhibited well-assembled telomeric ends containing the characteristic telomere sequence (TTTAGGG)n, there were a few cases where this sequence was either short or missing. Assuming incomplete assembly or insufficient extension, the HiFi reads were remapped to the genome. Reads aligning near the telomeres were selected, and contig assembly was performed using hifiasm63. The resulting contigs were then aligned back to the chromosomes, allowing for the extension of the chromosomes towards the outer ends to enhance the completeness of the telomere sequence assembly. For the S. babylonica genome assembly, the chromosomes were compiled as chromosome 01 to chromosome 19 (Sa/Aa, Sb/Ab, Va/Ba, and Vb/Bb) according to the homologous relationship with S. dunnii (S, Salix-clade) and S. brachista (V, Vetrix-clade). The chromosome number of our male S. dunnii is consistent with that of the female S. dunnii genome reported previously31.

The chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes were assembled using GetOrganelle69. Afterward, fragmented contigs were mapped to the chromosome-level genome and organelle genome sequences by Redundans70, enabling the identification of redundant segments. Furthermore, low-coverage fragments or haplotigs within the scattered sequences and rDNA fragments were discarded.

Genome annotation

Homology-based prediction, transcript prediction, and de novo prediction approaches were used for genome annotation. For homology-based prediction, we used the publicly available Salicaceae protein sequences (Supplementary Table 5) as homologous protein evidence for gene annotation. For transcript prediction, we used three strategies to assemble transcripts. In addition to using Trinity71 for de novo assembly directly, the reads were also aligned to genomes with HISAT272 before assembly with the Trinity genome-guided model and StingTie73. Then we combined all the transcript sequences and removed redundancy using CD-HIT74 (identity >95%, coverage >95%). Based on transcript evidence, we used the PASA pipeline75 to annotate gene structure, and aligned to the reference protein (Supplementary Table 5) to identify full-length genes. These genes were used for AUGUSTUS76 training, and we performed five rounds of optimization.

MAKER277 was used for genome annotation based on ab initio prediction, transcript and homolog protein evidence. After masking repeat sequences with RepeatMasker, AUGUSTUS78 was used for ab initio predict coding genes. We then aligned transcript and protein sequences to the genomes using BLASTN and TBLASTX. After optimizing the comparison results using Exonerate79, we integrated and predicted gene models with AUGUSTUS78, and expression sequence tag (EST). EvidenceModeler (EVM) gene structure annotation tool80 was further used to integrate MAKER and PASA annotation results. In addition, we performed TEsorter81 and EVM to identify and mask TE protein domains. Then, PASA75 was used to upgrade the EVM annotation, adding untranslated regions (UTRs) and alternative splicing. Finally, missense (internal stop codon or ambiguous base, no start codon or stop codon) annotations, and genes <50 amino acids were removed.

For noncoding RNA (ncRNA) annotation, tRNAs were annotated using tRNAScan-SE82, and RfamScan was used to align and annotate various ncRNAs. We also performed Barrnap (https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap) to remove partial results. Finally, we removed redundancies and integrated all the annotation results.

The functions of protein-coding genes were annotated based on three strategies: (1) Gene functions were identified using eggnog-mapper83, aligning with homologous gene databases; (2) We used DIAMOND to perform sequence similarity searches, and compared protein sequences with protein databases, including Swiss_Prot, TrEMBL, and NR (identity >30%, E-value <1e-5); (3) InterProScan84 was used to search domain similarity. We compared sequences with the PRINTS, Pfam, SMART, PANTHER, and CDD databases and obtained amino acid-conserved sequences, motifs, and domains.

We used EDTA85 to identify transposable elements (--sensive 1, --anno 1), producing a TE library. Then, RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org/RepeatMasker/) was used to determine repetitive regions within our genome assemblies.

Phylogenetic analysis and divergence time estimation

We performed a phylogenetic analysis of the eight willow genomes (S. suchowensis, S. purpurea, S. viminalis, S. brachista, S. babylonica (haplotypes Sa and Va), S. arbutifolia (haplotype a), S. dunnii (haplotype a), S. chaenomeloides), and used P. trichocarpa as the outgroup (Supplementary Table 5). After obtaining the longest mRNA among them, OrthoFinder86 was used to identify single-copy orthologous genes. To avoid the effect of sex chromosomes, we removed genes from chromosomes 7, 15, and 19. Then, these protein sequences were aligned using MAFFT87. We constructed gene trees with IQ-TREE (-m MFP -bb 1000 -bnni -redo)88. Then, ASTRAL was used to infer a species tree based on gene trees’ results89. Finally, MCMCTREE in PAML90 was used to estimate the divergent time (burnin = 400,000, sampfreq = 10, nsample = 100,000) based on two fossils and one inferred time at three nodes: (1) the root node of Salicaceae (48 Mya), (2) the divergence time between Salix- and Vetrix-clade (37.15 Mya to 48.42 Mya), and (3) the ingroup of Vetrix (Chamaetia-Vetrix)-clade (23 Mya)32. The chloroplast genomes of the nine species were obtained from available assemblies or assembled using GetOrganelle69 based on whole-genome sequencing reads (Supplementary Table 5). These chloroplast genome sequences were aligned by HomBlocks.pl with default parameters91, and then IQ-TREE was used to construct a chloroplast phylogenetic tree.

In order to determine the allotetraploidization time of S. babylonica, we calculated TE (transposable element) divergence values from the two subgenomes because TE substitution rates of the subgenomes of allotetraploids differ before and after polyploid formation92. Among the four haplotypes of S. babylonica, we used Sa vs. Va and Sa vs. Vb to perform this analysis, removing chromosomes 7 and 15. First, we used Nucmer93 to identify the matching region between two subgenomes of S. babylonica (alignment length >1000, alignment identity >90), then RepeatModeler (http://www.repeatmasker.org/) was used to create repeat sequences database based on above matching sequences (RMBlast), and RepeatMasker was used to identify TEs in subgenomes. Subsequently, the substitutions of these identified TEs were calculated with calcDivergenceFromAlign.pl (a script in RepeatMasker). Divergence was obtained by comparing TEs between S. babylonica and the repeat sequences database obtained above. Finally, the ggplot294 R package was used to print divergence values using GAM (Generalized Additive Model) to fit the curves. Two time points of divergence and merger between two subgenomes corresponded to TE divergence rates of 18% and 2.5% in Sa vs. Va, as well as 23% and 1.5% in Sa vs. Vb (Supplementary Fig. 6). The divergence time of Salix- and Vetrix-clade was 44.62 Mya according to the result of phylogenetic analysis above. Therefore, the allotetraploidization time was estimated: 44.62 Mya×2.5/18 ≈ 6.2Mya and 44.62 Mya×1.5/23 ≈ 2.91 Mya.

Identification of the sex-linked regions of weeping willow and Salix dunnii

Sequence reads of weeping willow and S. dunnii were filtered and trimmed by fastp95 with parameters “—cut_by_quality3 —cut_by_quality5 —n_base_limit 0 —length_required 60 —correction”. The KMC 3.1.196 was used to count the 31-mer of each clean dataset of the weeping willow. The k-mers with <30% missing and an average count >1 in each sex group were retained. The k-mers in all 40 individuals with minor allele (k-mer absent or present) frequency <0.1 were discarded. The filtered k-mers were mapped to the genome (76 chromosomes) of weeping willow using Bowtie97. K-mers with a coverage of 0 in all 20 female individuals were defined as male-specific k-mers, while k-mers with a coverage of 0 in 20 male individuals were defined as female-specific k-mers. We expect male (male heterogamety, male carrying XY, and female carrying XX) or female (female heterogamety, female carrying ZW, and male carrying ZZ) specific k-mers on a sex-linked region of sex chromosome(s).

We employed the CQ method35 to detect the sex chromosomes of the two willows. We made combined female and male clean read datasets of the two willows, respectively. The cq-calculate.pl software35 was used to calculate the CQ for each 50-kb nonoverlapping window of the genomes. For male heterogamety, the CQ is the normalized ratio of female to male alignments to a given reference sequence, and the CQ value is close to 2 (for XX/XY, 1.33 for XXXX/XXXY) in windows in the X-linked region and zero in windows in the Y-linked region. For female heterogamety, the CQ is the normalized ratio of male to female alignments, and the CQ value is close to 2 (for ZW/ZZ, 1.33 for ZZZW/ZZZZ) in windows in Z-linked region and to zero in windows in the W-linked region.

We aligned clean reads of S. dunnii to each genome (both haplotypes) using the BWA-MEM algorithm from bwa 0.7.1298,99 with default parameters. Samtools 0.1.19100 was used to extract primary alignments, sort, and merge the mapped data. PCR replicates were filtered using sambamba 0.7.1101. The variants were called and filtered using Genome Analysis Toolkit v. 4.1.8.1 and VCFtools 0.1.16102. Hard filtering of the SNP calls was carried out with “QD <2.0, FS >60.0, MQ <40.0, MQRankSum <−12.5, ReadPosRankSum <−8.0, SOR >3.0”. Only biallelic sites were kept for subsequent filtering. The sites with coverage greater than twice the mean depth at all variant sites across all samples were discarded. Genotypes with depth <4 were treated as missing, and sites with >10% missing data or minor allele frequency <0.05 were removed.

We used VCFtools to calculate weighted FST values between 18 male and 20 female genomes of S. dunnii103 with 100-kb windows and 10-kb steps. The Changepoint package104 was used to detect the boundaries of the SLRs based on FST and CQ values between the sexes of S. dunnii and CQ values and sex-specific k-mer counts of weeping willow, respectively. Furthermore, we used the Python version of MCScan105 to analyze chromosome collinearity between the protein-coding sequences detected in 7 and 15 chromosomes of S. dunnii and weeping willow and their homologous autosomes, to detect possible inversions in sex chromosomes. The “—cscore = 0.99” was used to obtain reciprocal best hit (RBH) orthologs for the collinearity analysis. We then combined all the previous analyses to detect the SLRs.

ARR17 and PI identification and phylogeny of ARR17

In order to obtain ARR17-like sequences in target species, we used BLASTN to blast ARR17-like gene (Potri.019G13360028) against the S. purpurea47, S. arbutifolia25, S. dunnii, and S. babylonica genomes with parameters “-evalue 1e-5 -word_size 8”. ARR17-like gene includes five exons, so only the sequences including all the exons were classified as intact ARR17-like genes, while sequences with <5 exons were regarded as partial ARR17-like duplicates24. We also used BLASTN to identify the PI-like genes in the S. babylonica genome using Potri.002G079000 as the query30. We used the exon regions of the identified ARR17-like sequences for phylogenetic reconstruction. These exons were aligned with MAFFT87, then we constructed a phylogenetic tree with IQ-TREE.

Ancestral sex-linked gene identification

We used the OrthoFinder86 to identify single-copy genes in SLRs of W and Z of S. babylonica and S. purpurea, 15X and 15Y of S. arbutifolia, and chromosome 15a of S. dunnii. We then extracted homologous genes, that diverged between ancestral X and Y in ancestors of Vetrix-clade and close to partial ARR17-like gene duplicates, as proposed by ref. 25. We obtained one ancestral single-copy homologous gene, then used MAFFT and IQ-TREE to align and reconstruct the phylogenetic tree using S. dunnii as outgroup.

Sex-linked region features and gene loss

We calculated the content of gene and repeat sequences (total repeat, TE, LTR-Gypsy, LTR-Copia) in the PARs and SLRs for S. babylonica (15VW, 15VZ) and S. dunnii (7X, 7Y). We calculated the difference between the SLRs and the PARs based on 100 kb windows.

We used chromosome 15a of S. dunnii as the reference to identify protein-coding gene loss in 15VW, 15VZ, 15X, and 15Y, and used 7Va in S. babylonica as the reference to identify gene loss in 7X and 7Y. Firstly, we identified shared genes in W-Z and X-Y, and specific genes in W, Z, X, and Y. For specific genes in X-SLR/W-SLR, there is no homologous gene in Y-SLR/Z-SLR. Similarly, there is no homologous gene in X-SLR/W-SLR for specific genes in Y-SLR/Z-SLR. Then we used these specific genes to determine gene loss among them. The degradation rate of W-SLR = W-SLR loss/(W-SLR loss + Z-SLR loss + their shared genes), and the degradation rated of Z-SLR = Z-SLR loss/(W-SLR loss + Z-SLR loss + their shared genes). Similarly, we obtained the degradation rate of X-SLR and Y-SLR. We also obtained the relevant data on PARs.

ARR17-like duplicates and PI expression analyses

Analysis and identification of sRNAs from female and male buds of S. babylonica was performed using sRNAminer v1.1.2106. sRNAs were identified with sRNAanno database107. Adapters, noncoding RNA (rRNA, tRNA, snoRNA, snRNA), and plasmid contamination were removed from the sRNA-Seq datasets. The clean reads were aligned to the reference genome of S. babylonica using sRNAminer and read (per site) coverage estimated using IGV-sRNA (https://gitee.com/CJchen/IGV-sRNA). We calculated the average read (per site) coverage of biological replicates of each partial ARR17-like duplicate and around regions and each intact ARR17-like duplicate.

We calculated the gene expression (excluding non-mRNA) among female and male catkins of S. babylonica, S. arbutifolia, and S. dunnii, respectively. The RNA datasets of S. arbutifolia are from Wang et al25. Each sex and individual contained three independent biological replicates (Supplementary Data 10). After filtering, clean transcript reads from each sample were mapped to their own genome with HISAT2 v2.1.0108. We used a haplotype genome assembly and sex chromosomes (15X and 15Y or 7X and 7Y) as reference genomes in S. arbutifolia and S. dunnii, and Sa and Va haplotypes genome assembly and sex chromosomes (15VW and 15VZ) as reference genomes in S. babylonica. The number of reads mapping to each gene was calculated using featureCounts109. Then we converted these read counts to TPM (transcripts per million reads). After filtering out unexpressed genes (counts = 0 in all samples), then we used the expression levels of the SLRs in males and females and their autosomes to identify the dosage compensation pattern110. The expression level of flower buds from S. babylonica was calculated using HISAT2 and IGV v2.17.1111. We obtained the average read coverage of biological replicates of each ARR17-like and PI-like gene.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 32171813 to L.H.) and the Special Fund for Scientific Research of Shanghai Landscaping & City Appearance Administrative Bureau (grant nos. G232403 and G242417 to L.H.). We are grateful to Si-Wen Zeng for sampling. We are indebted to James H. Leebens-Mack, Suhua Yang, Zhenyang Liao, Zhiqing Xue, Guangnan Gong, and Zhiying Zhu for their kind help during the preparation of our paper. We are grateful to the staff at Urban Horticulture Research and Extension Center of Shanghai Chenshan Botanical Garden for providing their facilities and help.

Author contributions

L.H. conceived the study. L.H., Yuàn W. and Yi W. designed and conceptualized the study. L.H., Yuàn W., Yi W., R.Z. and Yuán W. performed the data analysis. L.H. and Yi W. collected materials. L.H. and Yuàn W. wrote the manuscript. E.H., T.M., Y.M., J.E.M. and R.M. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Kanae Masuda and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The genome assembly sequences generated in this study have been deposited in the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) database under BioProject PRJCA016000 and in the NCBI database under BioProject PRJNA1130083, PRJNA1130084, PRJNA1130085, and PRJNA1130087. The sequencing datasets generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI database under BioProject accession codes PRJNA882493, PRJNA1020583, and PRJNA1020619. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Li He, Yuàn Wang.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-51158-3.

References

- 1.Evans, B. J., Alexander Pyron, R. & Wiens, J. J. Polyploidization and sex chromosome evolution in amphibians. in Polyploidy and genome evolution (eds Pamela S. & Soltis, D. E. S.) 385–410 (Springer, 2012).

- 2.Van de Peer, Yves, Mizrachi, Eshchar & Marchal, K. The evolutionary significance of polyploidy. Nat. Rev. Genet.18, 411–424 (2017). 10.1038/nrg.2017.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muller, H. J. Why polyploidy is rarer in animals than in plants. Am. Nat.59, 346–353 (1925). 10.1086/280047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He, L. & Hörandl, E. Does polyploidy inhibit sex chromosome evolution in angiosperms? Front. Plant Sci.13, 976765 (2022). 10.3389/fpls.2022.976765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mable, B. K., Alexandrou, M. A. & Taylor, M. I. Genome duplication in amphibians and fish: an extended synthesis. J. Zool.284, 151–182 (2011). 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2011.00829.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gates, R. R. Polyploidy and sex chromosomes. Nature117, 234 (1926). 10.1038/117234a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramsey, J. & Schemske, D. W. Pathways, mechanisms, and rates of polyploid formation in flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst.29, 467–501 (1998). 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.29.1.467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He, L. et al. Evolutionary origin and establishment of a dioecious diploid-tetraploid complex. Mol. Ecol.32, 2732–2749 (2023). 10.1111/mec.16902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stöck, M. et al. Sex chromosomes in meiotic, hemiclonal, clonal and polyploid hybrid vertebrates: along the ‘extended speciation continuum. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B376, 20200103 (2021). 10.1098/rstb.2020.0103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gulyaev, S. et al. The phylogeny of Salix revealed by whole genome re-sequencing suggests different sex-determination systems in major groups of the genus. Ann. Bot.129, 485–498 (2022). 10.1093/aob/mcac012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otto, S. P. & Whitton, J. Polyploid incidence and evolution. Annu. Rev. Genet.34, 401–437 (2000). 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott, M. F., Osmond, M. M. & Otto, S. P. Haploid selection, sex ratio bias, and transitions between sex-determining systems. PLoS Biol.16, e2005609 (2018). 10.1371/journal.pbio.2005609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mawaribuchi, S. et al. Sex chromosome differentiation and the W- and Z-specific loci in Xenopus laevis. Dev. Biol.426, 393–400 (2017). 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akagi, T., Henry, I. M., Kawai, T., Comai, L. & Tao, R. Epigenetic regulation of the sex determination gene MeGI in polyploid persimmon. Plant Cell28, 2905–2915 (2016). 10.1105/tpc.16.00532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robertson, F. M. et al. Lineage-specific rediploidization is a mechanism to explain time-lags between genome duplication and evolutionary diversification. Genome Biol.18, 1–14 (2017). 10.1186/s13059-017-1241-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mason, A. S. & Wendel, J. F. Homoeologous exchanges, segmental allopolyploidy, and polyploid genome evolution. Front. Genet.11, 564174 (2020). 10.3389/fgene.2020.01014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunado, N. et al. The evolution of sex chromosomes in the genus Rumex (Polygonaceae): identification of a new species with heteromorphic sex chromosomes. Chromosom. Res.15, 825–833 (2007). 10.1007/s10577-007-1166-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bewick, A. J., Anderson, D. W. & Evans, B. J. Evolution of the closely related, sex-related genes DM-W and DMRT1 in African clawed frogs (Xenopus). Evolution65, 698–712 (2011). 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01163.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newsholme, C. Willows: The GenusSalix (Timber Press, 1992).

- 20.Isebrands, J. G. & Richardson, J. Poplars and Willows: Trees for Society and the Environment (CABI, 2014).

- 21.Wagner, N. D., Volf, M. & Hörandl, E. Highly diverse shrub willows (Salix L.) share highly similar plastomes. Front. Plant Sci.12, 662715 (2021). 10.3389/fpls.2021.662715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang, Z., Zhao, S. D. & Skvortsov, A. K. Salicaceae. Flora China4, 139–274 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, Y. et al. The male-heterogametic sex determination system on chromosome 15 of Salix triandra and Salix arbutifolia reveals ancestral male heterogamety and subsequent turnover events in the genus Salix. Heredity130, 177 (2023). 10.1038/s41437-023-00592-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, D. et al. Repeated turnovers keep sex chromosomes young in willows. Genome Biol.23, 1–23 (2022). 10.1186/s13059-022-02769-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, Y. et al. Gap-free X and Y chromosomes of Salix arbutifolia reveal an evolutionary change from male to female heterogamety in willows, without a change in the sex-determining region. N. Phytol.242, 2872–2887 (2024). 10.1111/nph.19744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xue, Z. Q., Applequist, W. L. & Elvira Hörandl, L. H. Sex chromosome turnover plays an important role in the maintenance of barriers to post-speciation introgression in willows. Evol. Lett. 8, 467–477 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Teng, S. C. & Yu, H. Propagation of weeping willow from seed. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin.2, 131–132 (1948). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Müller, N. A. et al. A single gene underlies the dynamic evolution of poplar sex determination. Nat. Plants6, 630–637 (2020). 10.1038/s41477-020-0672-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xue, L. et al. Evidences for a role of two Y-specific genes in sex determination in Populus deltoides. Nat. Commun.11, 5893 (2020). 10.1038/s41467-020-19559-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leite Montalvão, A. P., Kersten, B., Kim, G., Fladung, M. & Müller, N. A. ARR17 controls dioecy in Populus by repressing B-class MADS-box gene expression. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B377, 20210217 (2022). 10.1098/rstb.2021.0217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He, L. et al. Chromosome-scale assembly of the genome of Salix dunnii reveals a male-heterogametic sex determination system on chromosome 7. Mol. Ecol. Resour.21, 1966–1982 (2021). 10.1111/1755-0998.13362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu, J. et al. Phylogeny of Salix subgenus Salix sl (Salicaceae): delimitation, biogeography, and reticulate evolution. BMC Evol. Biol.15, 1–13 (2015). 10.1186/s12862-015-0311-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang, Q., Liu, Y. & Sodmergen Examination of the cytoplasmic DNA in male reproductive cells to determine the potential for cytoplasmic inheritance in 295 angiosperm species. Plant Cell Physiol.44, 941–951 (2003). 10.1093/pcp/pcg121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He, L., Wagner, N. D. & Hörandl, E. Restriction-site associated DNA sequencing data reveal a radiation of willow species (Salix L., Salicaceae) in the Hengduan mountains and adjacent areas. J. Syst. Evol.59, 44–57 (2021). 10.1111/jse.12593 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall, A. B. et al. Six novel Y chromosome genes in Anophelesmosquitoes discovered by independently sequencing males and females. BMC Genomics14, 1–13 (2013). 10.1186/1471-2164-14-273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harlan, J. R., deWet, J. M. J. & On, Ö. Winge and a prayer: the origins of polyploidy. Bot. Rev.41, 361–390 (1975). 10.1007/BF02860830 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ming, R., Bendahmane, A. & Renner, S. S. Sex chromosomes in land plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol.62, 485–514 (2011). 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prentout, D. et al. An efficient RNA-seq-based segregation analysis identifies the sex chromosomes of Cannabis sativa. Genome Res.30, 164–172 (2020). 10.1101/gr.251207.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wright, A. E., Dean, R., Zimmer, F. & Mank, J. E. How to make a sex chromosome. Nat. Commun.7, 12087 (2016). 10.1038/ncomms12087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beukeboom, L. W. & Perrin, N. The Evolution of Sex Determination (Oxford Univ. Press, 2014).

- 41.Toups, M. A., Vicoso, B. & Pannell, J. R. Dioecy and chromosomal sex determination are maintained through allopolyploid speciation in the plant genus Mercurialis. PLoS Genet.18, e1010226 (2022). 10.1371/journal.pgen.1010226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerchen, J. F., Veltsos, P. & Pannell, J. R. Recurrent allopolyploidization, Y-chromosome introgression and the evolution of sexual systems in the plant genus Mercurialis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B377, 20210224 (2022). 10.1098/rstb.2021.0224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cauret, C. M. S., Mortimer, S. M. E., Roberti, M. C., Ashman, T.-L. & Liston, A. Chromosome-scale assembly with a phased sex-determining region resolves features of early Z and W chromosome differentiation in a wild octoploid strawberry. G312, jkac139 (2022). 10.1093/g3journal/jkac139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hillman, G., Hedges, R., Moore, A., Colledge, S. & Pettitt, P. New evidence of Lateglacial cereal cultivation at Abu Hureyra on the Euphrates. Holocene11, 383–393 (2001). 10.1191/095968301678302823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Papadopulos, A. S. T., Chester, M., Ridout, K. & Filatov, D. A. Rapid Y degeneration and dosage compensation in plant sex chromosomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA112, 13021–13026 (2015). 10.1073/pnas.1508454112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Almeida, P. et al. Genome assembly of the basket willow, Salix viminalis, reveals earliest stages of sex chromosome expansion. BMC Biol.18, 1–18 (2020). 10.1186/s12915-020-00808-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou, R. et al. A willow sex chromosome reveals convergent evolution of complex palindromic repeats. Genome Biol.21, 1–19 (2020). 10.1186/s13059-020-1952-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, J. et al. Sequencing papaya X and Yh chromosomes reveals molecular basis of incipient sex chromosome evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA109, 13710–13715 (2012). 10.1073/pnas.1207833109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hough, J., Hollister, J. D., Wang, W., Barrett, S. C. H. & Wright, S. I. Genetic degeneration of old and young Y chromosomes in the flowering plant Rumex hastatulus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA111, 7713–7718 (2014). 10.1073/pnas.1319227111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bachtrog, D. Y-chromosome evolution: emerging insights into processes of Y-chromosome degeneration. Nat. Rev. Genet.14, 113–124 (2013). 10.1038/nrg3366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Charlesworth, B., Sniegowski, P. & Stephan, W. The evolutionary dynamics of repetitive DNA in eukaryotes. Nature371, 215–220 (1994). 10.1038/371215a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ellegren, H. Sex-chromosome evolution: recent progress and the influence of male and female heterogamety. Nat. Rev. Genet.12, 157–166 (2011). 10.1038/nrg2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muyle, A. et al. Rapid de novo evolution of X chromosome dosage compensation in Silene latifolia, a plant with young sex chromosomes. PLoS Biol.10, e1001308 (2012). 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Charlesworth, B. Model for evolution of Y chromosomes and dosage compensation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA75, 5618–5622 (1978). 10.1073/pnas.75.11.5618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mank, J. E. Sex chromosome dosage compensation: definitely not for everyone. Trends Genet. 29, 677–683 (2013). 10.1016/j.tig.2013.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muyle, A., Shearn, R. & Marais, G. A. B. The evolution of sex chromosomes and dosage compensation in plants. Genome Biol. Evol.9, 627–645 (2017). 10.1093/gbe/evw282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ohno, S. Sex Chromosomes and Sex Linked Genes (Springer, 1967).

- 58.Muyle, A., Marais, G. A. B., Bačovsk’y, V., Hobza, R. & Lenormand, T. Dosage compensation evolution in plants: theories, controversies and mechanisms. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B377, 20210222 (2022). 10.1098/rstb.2021.0222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Doležel, J., Greilhuber, J. & Suda, J. Estimation of nuclear DNA content in plants using flow cytometry. Nat. Protoc.2, 2233–2244 (2007). 10.1038/nprot.2007.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics27, 764–770 (2011). 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ranallo-Benavidez, T. R., Jaron, K. S. & Schatz, M. C. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat. Commun.11, 1–10 (2020). 10.1038/s41467-020-14998-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Belton, J.-M. et al. Hi-C: a comprehensive technique to capture the conformation of genomes. Methods58, 268–276 (2012). 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods18, 170–175 (2021). 10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst.3, 95–98 (2016). 10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science356, 92–95 (2017). 10.1126/science.aal3327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst.3, 99–101 (2016). 10.1016/j.cels.2015.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu, G.-C. et al. LR_Gapcloser: a tiling path-based gap closer that uses long reads to complete genome assembly. Gigascience8, giy157 (2019). 10.1093/gigascience/giy157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hu, J., Fan, J., Sun, Z. & Liu, S. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics36, 2253–2255 (2020). 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jin, J.-J. et al. GetOrganelle: a fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol.21, 1–31 (2020). 10.1186/s13059-020-02154-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pryszcz, L. P. & Gabaldón, T. Redundans: an assembly pipeline for highly heterozygous genomes. Nucleic Acids Res.44, e113–e113 (2016). 10.1093/nar/gkw294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol.29, 644–652 (2011). 10.1038/nbt.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods12, 357–360 (2015). 10.1038/nmeth.3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol.33, 290–295 (2015). 10.1038/nbt.3122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fu, L., Niu, B., Zhu, Z., Wu, S. & Li, W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics28, 3150–3152 (2012). 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res.31, 5654–5666 (2003). 10.1093/nar/gkg770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stanke, M., Diekhans, M., Baertsch, R. & Haussler, D. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics24, 637–644 (2008). 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cantarel, B. L. et al. MAKER: an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Res.18, 188–196 (2008). 10.1101/gr.6743907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]