Abstract

Serum response factor (SRF) controls gene transcription in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and regulates VSMC phenotypic switch from a contractile to a synthetic state, which plays a key role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases (CVD). It is not known how post-translational SUMOylation regulates the SRF activity in CVD. Here we show that Senp1 deficiency in VSMCs increased SUMOylated SRF and the SRF-ELK complex, leading to augmented vascular remodeling and neointimal formation in mice. Mechanistically, SENP1 deficiency in VSMCs increases SRF SUMOylation at lysine 143, reducing SRF lysosomal localization concomitant with increased nuclear accumulation and switching a contractile phenotype-responsive SRF-myocardin complex to a synthetic phenotype-responsive SRF-ELK1 complex. SUMOylated SRF and phospho-ELK1 are increased in VSMCs from coronary arteries of CVD patients. Importantly, ELK inhibitor AZD6244 prevents the shift from SRF-myocardin to SRF-ELK complex, attenuating VSMC synthetic phenotypes and neointimal formation in Senp1-deficient mice. Therefore, targeting the SRF complex may have a therapeutic potential for the treatment of CVD.

Subject terms: Experimental models of disease, Mechanisms of disease, Aortic diseases

How post-translational SUMOylation regulates the SRF activity in cardiovascular disease is unclear. Here, the authors report that SRF SUMOylation increased by SENP1 deficiency switches vascular smooth muscle cells from a healthy contractile phenotype to a disease-associated synthetic phenotype.

Introduction

The regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) fate is involved in vascular development and pathological vascular remodeling in human cardiovascular diseases (CVD)1,2. VSMCs reside in the media of the vascular wall in a relatively differentiated state characterized by abundant expression of contractile phenotype-associated genes, including CNN1, α-SMA, SM-22α, and MYH112. In response to vascular injury or platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-BB stimulation, VSMCs undergo phenotypic switching from a contractile phenotype to a dedifferentiated synthetic state. This change is accompanied by decreased contractile phenotype-associated gene expression and increased expression of genes associated with proliferation, migration, and the synthetic phenotype (MYH10 and OPN) that constitute part of the pathological processes of vascular remodeling1–3. Thus, understanding the molecular mechanisms governing VSMC phenotypic switch may provide novel avenues for interventions in vascular remodeling after injury.

VSMC fate is controlled by several transcriptional regulators4. Serum response factor (SRF) is a master switch that regulates VSMC contractility4–6. Under normal conditions, SRF binds to CArG box (CC(A/T)6GG) elements together with its cofactors, myocardin (MYOCD) and myocardin-related transcriptional factor-A (MRTFA), to maintain the VSMC contractile phenotype4–7. However, it is now appreciated that these two SRF cofactors have opposing roles in vivo. Specifically, whereas MYOCD is the gate-keeper for a normal contractile state, upregulated MRTFA in pathogenesis promotes pathological vascular remodeling8,9. Moreover, vascular injury or PDGF-BB stimulation induces MEK-extracellular signal-related kinases (ERK)-dependent phosphorylation of Ets-like transcription factor-1 (ELK1), which displaces phospho-SRF from the myocardin complex to form the SRF-ELK1 complex6,. This complex binds to an adjacent ternary complex element (TCE), resulting in VSMC contractile phenotypic switch to a synthetic state4–7,10. Thus, investigations into the molecular mechanisms underlying SRF-mediated VSMC phenotypic switch would improve our understanding of the intricate mechanisms of vascular remodeling and neointima formation and hopefully inspire new strategies for treating CVD.

SUMOylation is a reversible and dynamic protein post-translational modification by the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) proteins that modulates protein activity, stability, subcellular localization and protein-protein interactions11,12. SUMOylation is involved in a wide variety of cellular processes, such as transcription, DNA repair, trafficking, and signal transduction13. The SUMO family in mammals has three analogs, SUMO1, SUMO2 and SUMO3, that are covalently attached to specific lysine(s) of target proteins. SUMOylation involves a multistep enzymatic cascade, sequentially catalyzed by activating (E1), conjugating (E2), and ligating (E3) enzymes, that facilitates SUMO attachment to its substrates13,14. Being reversible, SUMOylation is readily deconjugated by a six-member family of SUMO-specific proteases (SENPs): SENP 1–3 and 5–712,15. Among these, SENP1 is ubiquitously expressed, localized in the nucleus and other discrete cellular compartments, and largely responsible for deconjugating SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 modifications15.

Previous studies16–19, including our own work20–25, demonstrated that SENP1 deconjugates several SUMOylated proteins and is thus involved in many metabolic stress-, inflammatory response-, vascular disease- and tumor-related cellular processes. Global Senp1 deletion in mice causes perinatal lethality due to defective erythropoiesis20,26. We previously reported delayed vascular formation in Senp1 global knockout mice20. Moreover, SENP1-mediated SUMOylation in vascular endothelial cells (ECs) has been extensively investigated in EC-specific Senp1-deficient mice; under physiological and pathological conditions, SENP1 targets various substrates, including membrane receptors (Notch and VEGFR2) and nuclear transcriptional factors (GATA2 and NF-κB), to regulate angiogenesis and arteriosclerosis22,23. Moreover, we recently reported that Senp1 deficiency in SMCs induces ERα SUMOylation, which augments ERα transcriptional activity and stromal CD34+ KLF4+ stem cell proliferation, thereby promoting endometrial regeneration and repair24. However, the role of SENP1-mediated SUMOylation in VSMCs is unclear.

In this work, we identify a direct association between SENP1-mediated SRF SUMOylation and VSMC fates in vascular remodeling and human CVD. Specifically, SENP1 deficiency in VSMCs increases SRF SUMOylation switches a contractile phenotype-responsive SRF-myocardin complex to a synthetic phenotype-responsive SRF-ELK1 complex.

Results

Senp1 deficiency in VSMCs accelerates injury-induced neointimal formation with enhanced proliferation and migration

Partial loss of SENP1 protein and mRNA expression in carotid arteries of Senp1ECKO mice, and near complete loss in Senp1SMCKO mice, were observed due to abundant VSMCs in the aorta (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). Immunohistochemistry analysis further revealed specific ablation of the SENP1 protein in VSMCs of Senp1SMCKO mice and ECs of Senp1ECKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 1C).

At baseline conditions at 10–12 weeks of age, the external elastic lamina (EEL) circumference, luminal area, and media area of carotid artery did not differ between WT and Senp1SMCKO mice as determined by EVG and HE staining (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B). To determine the role of SENP1 in vascular remodeling, we performed wire injury in the carotid artery, a widely used method to study mechanisms of vascular remodeling27, in WT and Senp1SMCKO mice. Senp1 deficiency in VSMCs significantly aggravated injury-induced neointimal formation 28 days after wire injury, reflected by enlarged intima areas, decreased media areas, and increased intima/media ratios. The EEL circumference did not differ between WT and Senp1SMCKO mice (Fig. 1A with quantifications in B). These results indicate that Senp1 deficiency in VSMCs accelerates injury-induced neointimal formation. This is in sharp contrast to our previous observation in Senp1ECKO mice where EC-specific deletion attenuated vascular remodeling in several models22,23,25, suggesting that SENP1 has distinct regulatory functions in VSMCs and aortic ECs.

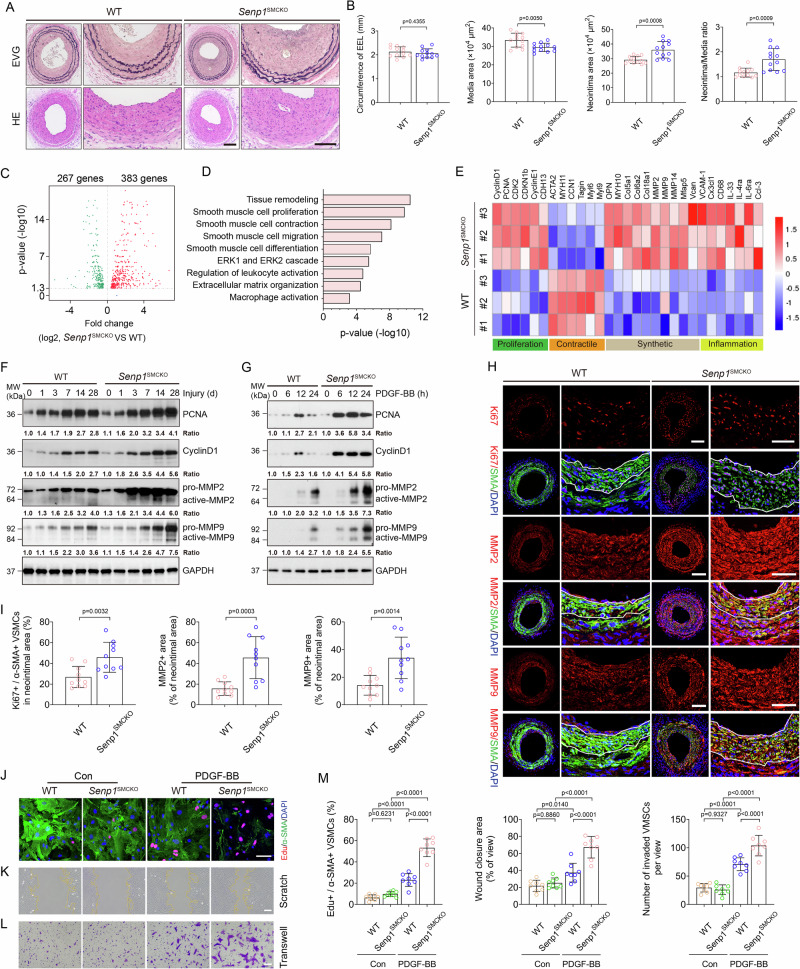

Fig. 1. Senp1 deficiency in VSMCs accelerates injury-induced neointimal formation with enhanced VSMCs proliferation and migration.

Senp1lox/lox (WT) and Senp1SMCKO mice were subjected to wire injury on left carotid arteries. A Representative photomicrographs of EVG staining and HE staining of carotid arteries harvested on day 28 post-injury. B Circumference of EEL, neointimal area, media area, and neointima/media ratio in carotid arteries were measured (n = 12 left carotid arteries per group). C–E RNA-sequencing analyses of carotid arteries on day 14 post-injury (n = 10 per group). C Volcano plot of the differentially expressed genes (two-sided; adjusted p value < 0.05). D GO analysis for the differentially expressed genes by p.adjust function in R. E Heat map showing the gene expressions by the two-sided Wilcoxon Rank Sum test adjusted p value, based on Bonferroni correction using the total number of genes in the dataset, was below 0.05. Western blots for proteins of VSMC proliferation and migration markers in carotid arteries (F) or VSMCs (G) isolated from non-injured WT and Senp1SMCKO mice. Protein fold changes are presented by taking non-injured WT carotid arteries (F) or untreated VSMC from WT (G) as 1.0 (n = 1 in G; additional two experiments were performed with different biological repeats presented in Supplemental Fig. 12). H, I Carotid arteries on day 28 post-injury were subjected to immunofluorescence. Ki67+α-SMA+ VSMCs, and fractional areas of the neointima occupied by MMP2+ or MMP9+ cells were quantified (n = 10 left carotid arteries per group). J–M PDGF-BB-induced proliferation and migration assays. J Co-staining of α-SMA by immunostaining and EdU by a Click-iT assay. K Scratch assay was performed in the absence or presence of PDGF-BB for 24 h before fixation and imaging. L Transwell migration assay was performed in the absence or presence of PDGF-BB for 24 h before fixation and staining with crystal violet. M % Edu+α-SMA+ in (J), % wound closure in (K) and number of invaded VMSCs in (L) were quantified (n = 8). Data are mean ± SEM. Unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test (B, I), one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (M). Scale bars, 50 μm (A, H); 10 μm (J–L). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To elucidate SENP1 regulation of vascular remodeling, we first performed whole-transcriptome analysis by bulk RNA-seq of carotid arteries of Senp1SMCKO and WT mice at baseline and at 14 days after wire injury. RNA-seq analysis revealed that VSMC-specific Senp1 deletion resulted in significant downregulation of 267 genes and upregulation of 383 genes in the carotid artery (Fig. 1C). Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed that Senp1 deletion significantly enriched physiological processes related to tissue remodeling, VSMC proliferation, contraction, migration, differentiation, ERK1/2 cascade, regulation of leukocyte activation, extracellular matrix (ECM) organization, and macrophage activation (Fig. 1D). Further analysis revealed that VSMC-specific Senp1 deletion decreased markers of the contractile phenotype (Acta2, Myh11, Ccn1, Tagln, Myl6, and Myl9) and increased markers of proliferation (Ccnd1, Pcna, Cdk2, Cdkn1b, Ccne1, Cdh13), synthetic phenotype (Opn, Myh10, Col5a1, Col6a2, Col18a1, Mmp2, Mmp9, Mmp14, Mfap5, and Vcan), and inflammation (Vcam1, Cx3cl1, Cd68, Il33, Il4ra, Il6ra, and Ccl3) (Fig. 1E). Despite the fact that carotid artery morphometry at baseline was unaltered by VSMC-specific Senp1 deletion, significant gene expression changes were detected in Senp1SMCKO compared to WT aortas, with reduced contractile marker genes and increased synthetic marker and inflammatory genes (Supplementary Fig. 2C). Collectively, these results indicate a pivotal role of SENP1 in regulating VSMC proliferation, migration, and phenotypic switch.

As VSMC proliferation and migration are key processes in neointimal formation in response to arterial injury or mitogenic factors, we investigated the potential effect of SENP1 on both processes. Western blot analysis revealed upregulated expression of the proliferation-inducing proteins cyclin D1 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in response to injury in a time-dependent manner; higher cyclin D1 and PCNA levels were detected in Senp1SMCKO mice than that in WT mice (Fig. 1F). Similar to the in vivo observations, cultured aortic VSMCs from Senp1SMCKO mice exhibited higher cyclin D1 and PCNA expression after PDGF-BB treatment compared with VSMCs from WT mice (Fig. 1G). Furthermore, immunohistochemical assays for Ki67, a proliferation marker, showed that Senp1 deficiency in VSMCs dramatically enhanced their proliferation, as determined by markedly increased Ki67- and α-SMA-positive VSMCs compared with WT mice, 28 days after wire injury (Fig. 1H). Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-facilitated VSMC migration from the media to the intima is critical for postinjury neointimal formation28. Western blot demonstrated that wire injury or PDGF-BB treatment induced MMP2 and MMP9 protein activity, with higher levels in Senp1SMCKO mice than WT mice (Fig. 1F, G). Consistently, immunohistochemical assays showed dramatically higher MMP2 and MMP9 protein expression levels in carotid arteries of Senp1SMCKO mice compared with WT mice 28 days after wire injury (Fig. 1H, I). Moreover, multiple ECM-related genes required for VSMC migration (Col15a1, Col5a2, Col6a2, and Col1a1), tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1 (Timp1), and Mmp14 were upregulated after wire injury as determined by qRT-PCR. Senp1 deficiency in VSMCs aggravated injury-induced expression of Col15a1, Col5a2, Col6a2, and Timp1 (Supplementary Fig. 3).

We further evaluated VSMC proliferation and migration using in vitro models. To this end, PDGF-BB-stimulated aortic VSMCs from WT and Senp1SMCKO mice were subjected to Edu incorporation assays. Senp1-deficient VSMCs proliferated more than WT VSMCs (Fig. 1J with quantifications in Fig. 1M for Edu+ SMCs). Transwell and scratch assays revealed that Senp1 deletion increased PDGF-BB-induced VSMC migration (Fig. 1K, L with quantifications in Fig. 1M for wound closure area and number of invaded cells).

We further investigated whether Senp1 deficiency-mediated induction of neointima growth in VSMCs is related to decreased apoptotic activity. Western blot analyses found no difference in the expression levels of apoptosis-related genes (caspase-9, Bcl-2, and Bax) in Senp1SMCKO mice compared with WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 4A). Immunohistochemical assay of cleaved caspase-3, another pro-apoptotic marker, showed no difference in Senp1SMCKO mice compared with WT mice 28 days after injury (Supplementary Fig. 4B, C). Taken together, these results indicate that Senp1 deficiency in VSMCs promotes their proliferation and migration, thereby accelerating injury-induced neointimal formation.

Senp1 deficiency in VSMCs results in loss of contractile phenotype in injury-induced neointima

VSMC phenotype switching, from a differentiated contractile state to a dedifferentiated synthetic state, plays a vital role in neointimal formation after vascular injury2,3. Consistent with the bulk RNA-seq data, VSMC-specific Senp1 deletion weakly down-regulated basal levels of VSMC contractile markers, such as CNN1, α-SMA, SM22α, and MYH11, and up-regulated those of VSMC synthetic markers, such as MYH10 and OPN, as detected by immunostaining (Supplementary Fig. 5) and western blot (Fig. 2A). Moreover, wire injury caused further loss of all four contractile markers, while increasing expression of two synthetic markers in a time-dependent manner. Senp1SMCKO mice exhibited a more rapid decrease in the four contractile markers and increase in the two synthetic markers29 compared with WT mice (Fig. 2A). This phenotypic switch within the neointima on day 28 post-injury was more evident in the Senp1SMCKO mice (Fig. 2B, C).

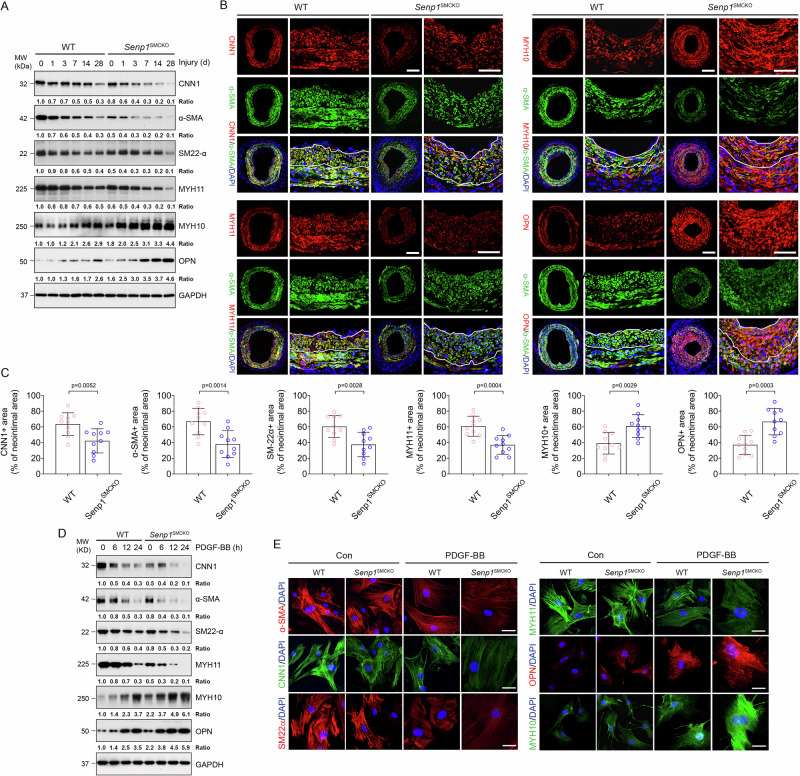

Fig. 2. SENP1 deficiency in VSMCs results in a loss of contractile phenotype in injury-induced neointima.

WT and Senp1SMCKO mice at age of 10–12 weeks were subjected to wire injury on left carotid arteries, and tissues were harvested for analyses on day 3–28 post-injury as indicated. Non-injured mice were used as controls (time 0). A Western blots for proteins of VSMC contractile and synthetic markers on day 0–28 post-injury. Each tissue sample was pooled from three individual aortas and protein bands were quantified by densitometry and fold changes are presented by taking non-injured WT carotid arteries as 1.0. Additional two experiments were performed with different biological repeats presented in Supplemental Fig. 12. B, C Carotid arteries on day 28 post-injury were subjected to immunofluorescence co-staining of various contractile and synthetic markers as indicated with DAPI counterstaining for nuclei (blue) (B). Fractional areas of the neointima occupied by each marker were quantified (n = 10 left carotid arteries per group) (C). D, E VSMCs isolated from non-injured WT and Senp1SMCKO mice treated with PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml) for indicated times. D VSMC contractile and synthetic markers were detected by Western blot (0, 6, 12 and 24 h time points) and (E) immunofluorescence staining (0 and 24 h time point). Protein bands were quantified by densitometry and fold changes are presented by taking untreated VSMC from WT as 1.0 (n = 2). Data are mean ± SEM. Unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test (C). Scale bars, 50 μm (B). 10 μm (E). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To validate these observations in vitro, cultured aortic VSMCs were exposed to PDGF-BB, the most widely accepted approach for initiating VSMC phenotype switch in vitro. Western blots (Fig. 2D) and immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 2E) showed decreased expression of contractile markers (CNN1, α-SMA, SM22α, and MYH11), while markedly increased expression of synthetic markers (MYH10 and OPN) in PDGF-BB-treated cells compared to that in untreated VSMCs. Senp1 deficiency in VSMCs caused repression of CNN1, α-SMA, SM22α, and MYH11, but promotion of MYH10 and OPN (Fig. 2D, E) in a time-dependent manner compared to the VSMCs from WT mice. These results demonstrated that Senp1 in VSMCs is essential for the maintenance of the contractile phenotype of carotid arteries both in physiological and pathological states.

Senp1 deficiency in VSMCs augments the SRF-ELK complex formation during vascular remodeling

MEK1/2-ERK1/2-ELK1 pathway activation in VSMCs after vascular injury is responsible for the ELK1-mediated transcriptional switch from a contractile to synthetic phenotype5. Phosphorylated MEK1/2, ERK1/2, and ELK1 levels were low in normal carotid arteries, but progressively increased after wire injury. Senp1SMCKO mice exhibited a more rapid increase in phosphorylated MEK1/2, ERK1/2, and ELK1 levels compared with WT mice (Fig. 3A). Immunohistochemical staining revealed a significant increase in the percentage of phospho-ELK1-positive, α-SMA-positive VSMCs in the neointima of Senp1SMCKO mice as compared to that of WT mice 28 days after injury. In contrast, no statistical difference was detected in the percentage of phospho-ELK1-positive, CD31-positive ECs in the neointima of Senp1SMCKO mice as compared to that of WT mice 28 days after injury (Fig. 3B with quantifications in Fig. 3C).

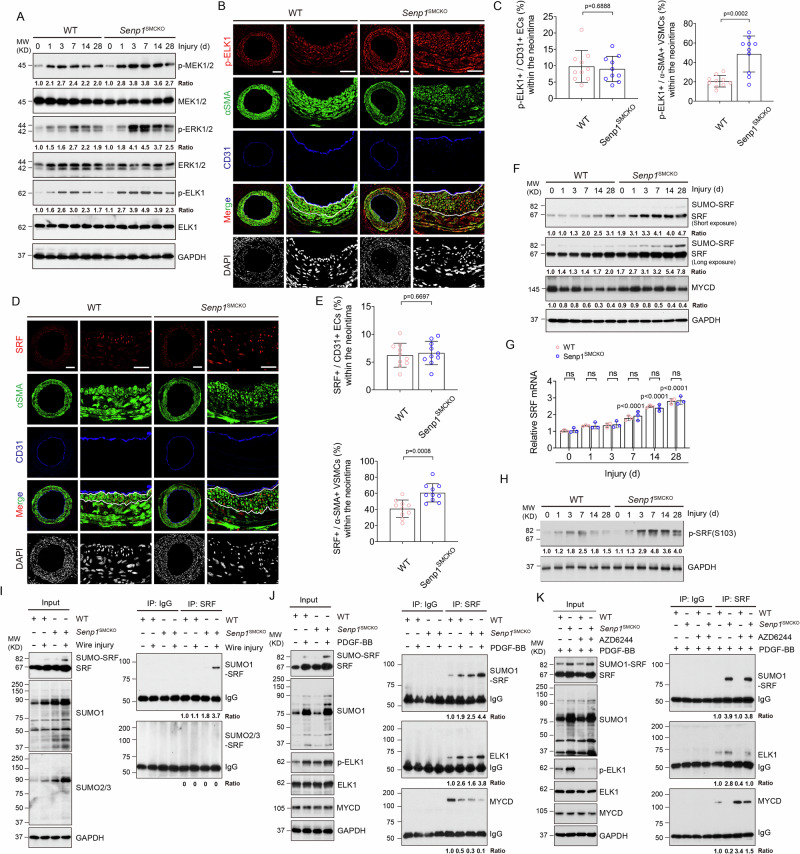

Fig. 3. SENP1 deficiency in VSMCs augments the SRF-ELK complex during vascular remodeling.

Carotid arteries from WT and Senp1SMCKO mice on day 0–28 post-injury. A Western blots for proteins and protein fold changes are presented by taking non-injured WT carotid arteries as 1.0. Additional two experiments were performed with different biological repeats presented in Supplemental Fig. 12. B, C Immunofluorescence staining on day 28 post-injury. C Fractional number of p-ELK+ cells within the neointimal areas or ECs were quantified (n = 10 left carotid arteries per group). D, E Immunofluorescence staining in carotid arteries on day 28 post-injury. D Representative images. E Fractional number of SRF+ cells within the neointimal areas or ECs were quantified (n = 10 left carotid arteries per group). F Western blots for SRF and myocardin. Each tissue sample was pooled from three individual aortas and protein bands were quantified by densitometry and fold changes are presented by taking non-injured WT carotid arteries as 1.0. Additional two experiments were performed with different biological repeats presented in Supplemental Fig. 12. G qRT-PCR for mRNAs in carotid arteries. Relative mRNA levels are presented by taking non-injured WT as 1.0 (n = 3). H Western blots for phospho-SRF. Protein fold changes are presented by taking non-injured WT carotid arteries as 1.0 (n = 1). I SRF SUMOylation in day 7 post-injury carotid arteries. Co-immunoprecipitation assays with anti-SRF or IgG followed by western blot with SUMO1 or SUMO2/3 as indicated. Protein fold changes are presented by taking non-injured WT carotid arteries as 1.0 (n = 2). J SRF-SUMO1, SRF-ELK and SRF-myocardin complexes by co-immunoprecipitation assays in VSMCs. Protein fold changes are presented by taking untreated VSMC as 1.0 (n = 1). K Effects of AZD6244. VSMCs were treated with PGDF-BB in the absence or presence of AZD6244 (0.5 μmol/L) for 60 min. Co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed and protein fold changes are presented by taking untreated VSMC from WT as 1.0 (n = 1). Data are mean ± SEM, compared with WT mice (two-tailed Student’s t test) (C, E) and compared with un-injured or untreated groups (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis) (G). ns no significance. Scale bars, 50 μm (B, D). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

It has been demonstrated that the sustained activation of multiple signal pathways, such as NF-κB, P38-MAPK, AKT and STAT3, regulate injury-induced neointimal formation5,30. Through western blot, we found that the protein levels of Phospho-NF-κB-P65, Phospho-P38, Phospho-AKT and Phospho-STAT3 progressively increased in carotid arteries from 1 day after injury, peaked at 3–7 days, and dropped thereafter (Supplementary Fig. 6). However, no obvious phosphorylated alterations of these proteins were observed between WT and Senp1SMCKO mice.

Since SRF together with its cofactor myocardin maintain the VSMC contractile phenotype4–7,10, we also examined if their expressions were altered by SENP1 deletion. At basal conditions, SRF protein expression was significantly increased in the carotid arteries of Senp1SMCKO mice compared with WT mice, as demonstrated by its high expression in α-SMA-positive VSMCs of the carotid artery from Senp1SMCKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 7A, B). The number of SRF-positive cells was further increased in Senp1SMCKO mice after vascular injury (Fig. 3D, E). SRF was expressed predominantly in α-SMA-positive VSMCs, but not in CD31-positive ECs (Supplementary Fig. 7A, B and Fig. 3). Western blot indicated that injury induced a time-dependent increase of total SRF (Fig. 3F) and phospho-SRF (Fig. 3H) expression in the carotid artery which was augmented by SENP1 deletion. The expression of myocardin was not altered in response to wire injury in both groups (Fig. 3F). Despite the increases of SRF protein levels, Srf mRNA levels in the injured carotid arteries of Senp1SMCKO mice did not differ compared to that in the WT counterparts (Fig. 3G).

The results above prompted us to investigate the post-translational regulation of SRF. We observed increased intensity in the extra band above that for SRF protein (increased by ~15 KD) in injured carotid arteries of Senp1SMCKO mice compared with that in WT mice (see Fig. 3F). A previous report showed that in a Hela cell overexpression system SRF was modified by SUMO-1, chiefly at lysine147 within the DNA-binding domain31. To further investigate if endogenous SRF was modified by SUMOylation in aorta tissues, carotid artery extracts obtained at 7 days after wire injury were subjected to co-immunoprecipitation assay under denaturing condition. Western blot analysis revealed a specific SUMO1-conjugated SRF band that was detected in the co-immunoprecipitated proteins with anti-SRF antibody, but not with control IgG. However, SUMO2/3-conjugated SRF was not observed in the Senp1SMCKO aortic lysates (Fig. 3I). Consistently, immunostaining showed that SUMO1 expression was increased in α-SMA-positive VSMCs of the carotid artery in Senp1SMCKO mice at basal condition (Supplementary Fig. 7C, D), and more dramatically increased in the injured vessels, similar to the SRF expression pattern (Supplementary Fig. 7E, F). Our results indicate that Senp1 deficiency in VSMCs induced SUMO1-mediated SRF SUMOylation. Of note, SUMO-conjugated MYOCD or SUMO-conjugated ELK1 was not detected in the aortic lysate, despite that SUMOylations of both myocardin and ELK1 have been reported previously in cultured cells32–34.

As vascular injury reportedly displaces SRF from the SRF-myocardin complex to form the SRF-ELK1 complex, resulting in VSMC phenotypic switch4–7,10, we investigated whether SRF SUMOylation affected its binding to myocardin and ELK1. To this end, VSMCs from WT and Senp1SMCKO aortas were untreated or treated with PDGF-BB and cell lysates were subjected to co-immunoprecipitation assays under non-denaturing condition. Similar to the in vivo injury, PDGF-BB increased SRF SUMOylation which was increased by the Senp1 deficiency. Moreover, PDGF-BB increased SRF binding to ELK1 but decreased SRF binding to the myocardin in VSMCs, and these PDGF-BB responses were further augmented by the Senp1 deficiency. These results suggest a role of SRF SUMOylation in SRF-ELK complex formation (Fig. 3J).

We also assessed if ELK phosphorylation is required for SRF-ELK complex formation. To this end, we examined the effects of AZD6244, a specific inhibitor of ELK1 activation, on the binding of SRF to myocardin and ELK1 in cultured aortic VSMCs of WT and Senp1SMCKO mice. Indeed, AZD6244 treatment specifically blocked ELK1 phosphorylation without affecting the expression of ELK, SRF or myocardin. Co-immunoprecipitation analyses showed that AZD6244 did not affect SRF SUMOylation. However, AZD6244 drastically disrupted the PDGF-BB-induced SRF-ELK1 complex but enhanced the SRF-Myocardin complex in WT mice and partially restored the association of SRF with myocardin in Senp1SMCKO mice (Fig. 3K). These data indicate that both SRF SUMOylation and ELK1 phosphorylation are required for a switch from the SRF-myocardin complex to the SRF-ELK1 complex in response to PDGF-BB stimulation.

SRF SUMOylation regulates SRF-ELK1 complex formation

To determine how SUMOylation regulates SRF activity and the SRF-ELK complex, we first examined if intracellular localization of SRF was altered by SENP1 deficiency in cultured aortic VSMCs. Immunofluorescence staining showed low SRF levels in normal VSMC nuclei. PDGF-BB stimulation increased SRF expression in both lysosomes and nuclei, where SRF was co-localized with lysosome marker LAMP2 and nuclear marker DAPI, respectively. However, SENP1 deficiency induced SRF accumulation from the lysosomes and nuclei (Fig. 4A). PDGF-BB stimulation also increased nuclear expression of KLF4, another transcription factor regulating VSMC function28,35,36. However, KLF4 expression and localization were not affected by SENP1 deletion (Supplementary Fig. 8). We confirmed the SRF localization in SENP1-deficient VSMCs by a cellular fractionation assay; PDGF-BB stimulation increased total SRF and SUMOylated SRF levels in nuclear and cytoplasm factions, while SENP1 deficiency induced a profound shift of total SRF and SUMOylated SRF from the lysosomes to the nucleus (Fig. 4B). Cycloheximide assays indicated that SENP1 deficiency sustained the levels of both SUMOylated and total SRF proteins in cultured aortic VSMCs (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that SUMOylation promoted the location change of SRF from lysosomes to nuclei, protecting SRF from degradation.

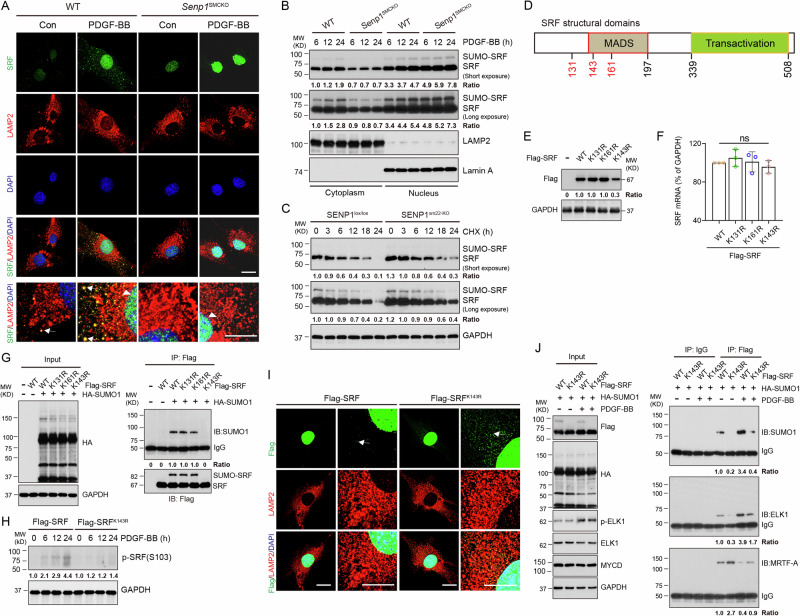

Fig. 4. SRF SUMOylation regulates the SRF-ELK1 complex formation.

A–C VSMCs were isolated from un-injured WT and Senp1SMCKO mice. A Cells were subjected to immunofluorescence co-staining. High magnification of merged images is shown at the bottom of each panel. Lysosomal and nuclear SRF are indicated by arrows and arrowheads, respectively. B Cytoplasm and nuclear fractions were isolated by cellular fractionation followed by western blot for SRF, lysosomal marker LAMP2 and nuclear marker lamin A. n = 1. C VSMCs were treated with CHX (100 ng/ml) for 0–24 h. Protein fold changes are presented by taking untreated VSMC from WT as 1.0 (n = 1). D A diagram for the structural domains of mouse SRF protein. The putative SUMOylation K residues are indicated in red. MOVAS-1 cells were transiently transfected with Flag-tagged SRF without (E, F, H) or with (G, I) HA-SUMO1. E Cell lysates were subjected to western blot with the anti-Flag antibody. F Total RNAs were used for qRT-PCR for Srf mRNA levels. n = 3. G Cells lysates were subjected to co-immunoprecipitation assays under denaturing condition with anti-Flag followed by western blot with anti-HA (SUMO1). H Cell lysates were subjected to western blot for phospho-SRF. I Flag-SRF and Flag-SRFK143R -expressing cells were subjected to immunofluorescence co-staining. J Flag-SRF and Flag-SRFK143R-expressing cells were untreated or treated with PDGF-BB for 24. Cells lysates were subjected to co-immunoprecipitation assays under non-denaturing condition with anti-Flag or IgG control followed by western blot with anti-HA (SUMO1), anti-ELK1 or anti-myocardin antibodies. Protein fold changes are presented by taking Flag-tagged SRF-WT MOVAS-1 cells as 1.0 (n = 1). Data are mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. ns no significance. Scale bars, 20 μm (A, I). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Although SUMO1-mediated SUMOylation has been previously reported for SRF in an overexpression system, its role in SRF regulation remains unclear31. Bioinformatics analyses indicated that the SRF protein contains three putative SUMOylation sites (K131, K143, and K161) in the MADS domain (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Fig. 9). Therefore, we examined effects of KR mutations (K131R, K143R, and K161R) on SRF protein stability. In MOVAS-1 cells transfected with these mutation-carrying plasmids, similar protein levels were detected in SRFK131R, SRFK161R mutants and wild-type SRF, whereas that of the SUMOylation-deficient SRFK143R mutant was approximately one-third that of wild-type SRF (Fig. 4E). Notably, mRNA levels of the wild-type SRF and all three mutants did not differ (Fig. 4F). We further determined SRF SUMOylation by co-immunoprecipitation assays under denaturing condition. Results revealed that the SUMO1-conjugated SRF accumulated in MOVAS-1 cells with co-expression of HA-SUMO1 and Flag-SRF, SRFK131R, or SRFK161R. However, SUMO1-conjugated SRF level was diminished in SRFK143R mutant (Fig. 4G). PDGF-BB stimulation increased phospho-SRF expression. However, SRFK143R mutant decreased phospho-SRF expression (Fig. 4H). Immunofluorescence staining indicated that SRF mutation at K143 (K143R) enhanced the accumulation of SRF in the lysosomes in PDGF-BB-stimulated VSMCs (Fig. 4I), supporting that SRF SUMOylation promoted its phosphorylation and translocation from lysosome to nucleus.

We then determined the effect of SRF SUMOylation on SRF-ELK1 complex formation. Co-immunoprecipitation assays revealed that the non-SUMOylated mutant SRFK143R increased SRF binding to myocardin concomitant with reduced binding to ELK1 in the untreated and PDGF-BB-treated VSMCs (Fig. 4J). These results suggest that SRF SUMOylation at K143 induces its nuclear accumulation and switches its binding preference from myocardin to ELK1 in VSMCs in response to PDGF-BB stimulation.

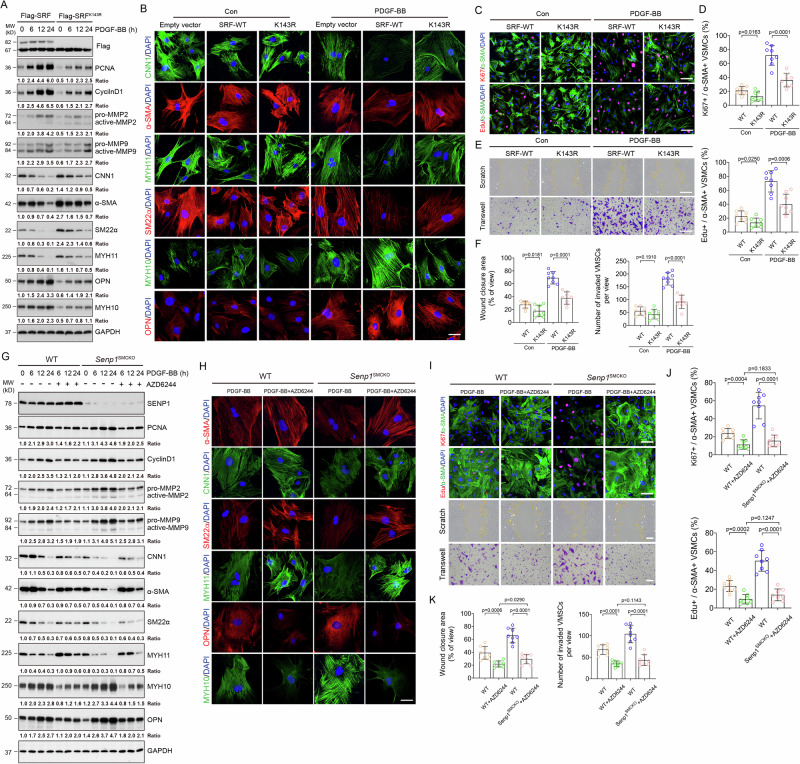

SRF SUMOylation and SRF-ELK complex regulate VSMC proliferation, migration, and phenotypic switch

To determine the functional significance of SRF SUMOylation in VSMCs, we generated stable MOVAS-1 lines overexpressing a Flag-tagged empty vector, SRF-WT, or SRFK143R. Western blotting confirmed that stable transfection of SRFK143R enhanced contractile marker expression (CNN1, α-SMA, SM22α and MYH11) and inhibited synthetic marker expression (MYH10 and OPN) in MOVAS-1 cells with or without PDGF-BB stimulation (Fig. 5A). These observations were confirmed by immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 5B). Moreover, SRFK143R decreased protein levels of PCNA, CyclinD1 MMP2, and MMP9 (Fig. 5A). Consistently, SRFK143R inhibited proliferation and migration of MOVAS-1 cells with or without PDGF-BB stimulation, as shown by the decreased number of Edu+ or Ki67+ cells (Fig. 5C, D), and reduced the percentage of migrating cells in both scratch and Transwell assays (Fig. 5E, F). These data suggest that SRF SUMOylation at K143 plays an important function in controlling proliferation, migration, and the synthetic phenotypic switch of VSMCs.

Fig. 5. SRF SUMOylation and the SRF-ELK complex regulate VSMC proliferation, migration and phenotypic switching.

A–F MOVAS-1 cells were stably transfected with empty vector, Flag-SRF or Flag-SRFK143R and pooled clones were expanded for the designed experiments. A Cells were untreated or treated with PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml) for 0–24 h followed by western blot for VSMC proliferation, migration and phenotypic markers. Protein bands were quantified by densitometry and fold changes are presented by taking Flag-tagged SRF-WT MOVAS-1 cells as 1.0 (n = 1). B Cells were untreated or treated with PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml) for 24 h and were subjected to immunofluorescence co-staining with VSMC contractile/synthetic markers as indicated. C–F Cells were serum-starved for 24 h followed by treatment with PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. C Cells were used for Edu incorporation assay or Ki67 staining with α-SMA. Representative images are presented. D % Ki67+ and Edu+ VMSC were quantified (n = 8 slides per group). E Cells were subjected to scratch and transwell assays in the absence or presence of PDGF-BB for 24 h before fixation and imaging. Representative images are presented. F % wound closure and # of invaded VMSCs were quantified (n = 8 slides per group). G–K Primary aortic VSMCs from WT and Senp1SMCKO mice were treated with PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml) for 0–24 h in the absence or presence of AZD6244 (1 μmol/L). G Cell lysates were subjected to western blot for VSMC proliferation, migration and phenotypic markers. Protein bands were quantified by densitometry and fold changes are presented by taking untreated VSMC from WT as 1.0 (n = 1). H Cells were subjected to immunofluorescence co-staining with VSMC contractile/synthetic markers as indicated. I–K Cells were serum-starved for 24 h and subjected to Edu incorporation, scratch and transwell assays. Representative images are presented in (I). % Ki67+ or Edu+ VMSC (J), % wound closure and # of invaded VMSCs (K) were quantified (n = 8 slides per group). Data are mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Scale bars, 10 μm (B, H); 50 μm (C, E, I). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Because ELK1 phosphorylation is required for the SRF-ELK complex formation, we next determined its role in regulating VSMC functions. Similar to the observations made in K143R-expressing cells, AZD6244 treatment in primary aortic VSMCs from WT and Senp1SMCKO mice attenuated PDGF-BB-induced expression of cell cycle-related proteins (CyclinD1 and PCNA) and migratory proteins (MMP2 and MMP9) (Fig. 5G). Moreover, western blot (Fig. 5G) and immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 5H) revealed that AZD6244 enhanced and suppressed contractile and synthetic marker expression, respectively. AZD6244 significantly inhibited the proliferation of PDGF-BB-stimulated aortic VSMCs from WT and Senp1SMCKO mice, as determined by Ki67 staining and Edu incorporation assays (Fig. 5I, J). Next, scratch and Transwell assays revealed that AZD6244 treatment decreased PDGF-BB-induced in vitro migration of VSMCs from WT and Senp1SMCKO mice (Fig. 5I, K). These findings suggested that inhibition of the SRF-ELK1 axis by AZD6244 attenuated PDGF-BB-induced VSMC proliferation, migration, and synthetic phenotype switch.

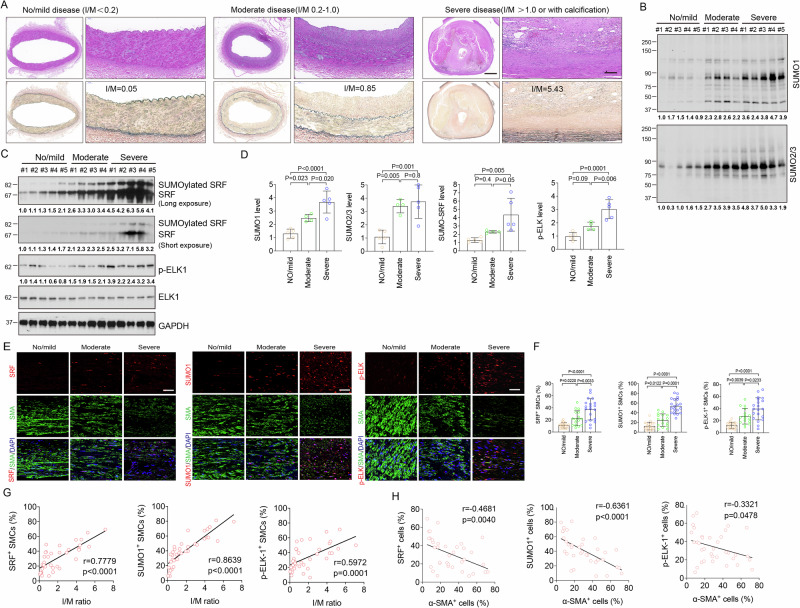

The SRF SUMOylation and phospho-ELK were upregulated in human intimal hyperplasia

To determine whether the role of SRF SUMOylation in VSMC phenotypic switch observed in mouse vascular injury models translates to human CVD, we examined SUMO1, SRF, p-ELK, OPN, and α-SMA in the left main coronary arteries of patients with no/mild (grade I plaque), moderate (grade II plaque), or severe coronary artery disease (CAD) (grade III and IV plaque) (Fig. 6A). Compared with no/mild CAD group, western blot results showed that protein levels of SUMO1, SRF, and p-ELK1 were markedly increased in the moderate CAD group, and further increased in severe CAD group. SUMO2/3 protein levels were markedly increased in all CAD groups, but with no difference between moderate and severe groups. However, compared with no/mild CAD group, there was no increase of total ELK1 protein in moderate and severe CAD group (Fig. 6B, D). In the same samples, immunohistochemical staining showed that the expression of SRF, SUMO1, and p-ELK1 progressively increased with disease severity, and most of these signals were co-localized with α-SMA-positive VSMCs (Fig. 6E, F). A strong positive linear relationship between the intima/media (I/M) ratio and number of VSMCs expressing SRF (r = 0.7779, p < 0.0001), SUMO1 (r = 0.8639, p < 0.0001) or p-ELK1 (r = 0.5972, p = 0.0001) was observed (Fig. 6G). Furthermore, number of cells expressing the contractile marker a-SMA inversely correlated with numbers of cells expressing SRF (r = −0.4681, p = 0.0040), SUMO1 (r = −0.6361, p < 0.0001), p-ELK1 (r = −0.3321, p = 0.0478) (Fig. 6H). We also examined the VSMC synthetic marker OPN expression in this patient cohort. Immunostaining revealed that luminal VSMCs exhibited increasing OPN expression with increase in CAD severity (Supplementary Fig. 10A, B), and that OPN expression positively correlated with I/M ratio (r = 0.6644, p < 0.0001) (Supplementary Fig. 10C). These observations establish an association between the SRF SUMOylation, ELK1 phosphorylation, and CAD severity, as well as VSMC phenotypic switch in human CAD samples.

Fig. 6. The SRF SUMOylation and phospho-ELK were upregulated in human intimal hyperplasia.

Left main coronary arteries of patients with no/mild (n = 5), moderate (n = 4), and severe CAD (n = 5) were collected for this study. A Morphological assessment and classification disease severity in human left main coronary arteries. HE (upper) and EVG staining (lower). Scale bar: 1000 μm (left) and 100 μm (right). B–D The protein levels of SUMO1, SUMO2/3, SRF, p-ELK1 and t-ELK1 were determined by western blot. GAPDH served as the control. Protein bands in (B, C) were quantified by densitometry and fold changes are presented by taking the first no/mild sample as 1.0. Quantification data are presented in (D). One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. E Immunocytochemical analysis of SRF, SUMO1 and p-ELK1. Representative images of immunofluorescence staining for α-SMA (green) and SRF (red), SUMO1 (red), or p-ELK1 (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 20 μm. F Quantitative analysis of SUMO1, SRF or p-ELK1-positive cells to α-SMA-positive VSMCs in the vessel wall. Data are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. G Scatter plots of SRF-, SUMO1- or p-ELK1-positive VSMCs and the I/M ratio. The corresponding Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r) between SRF-, SUMO1- or p-ELK1-positive VSMCs and the I/M ratio, and the p value (two-sided) are shown. H Scatter plots of SRF+ cells (%), SUMO1+ cells (%) and p-ELK-1+ cells (%) with α-SMA+ cells (%). The corresponding Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r) between SRF-, SUMO1- or p-ELK1-positive cells and α-SMA-positive cells, and the p value are shown. Data are mean ± SEM. Correlation analyses between variables were performed using the Pearson rank correlation test. p values were two-tailed. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

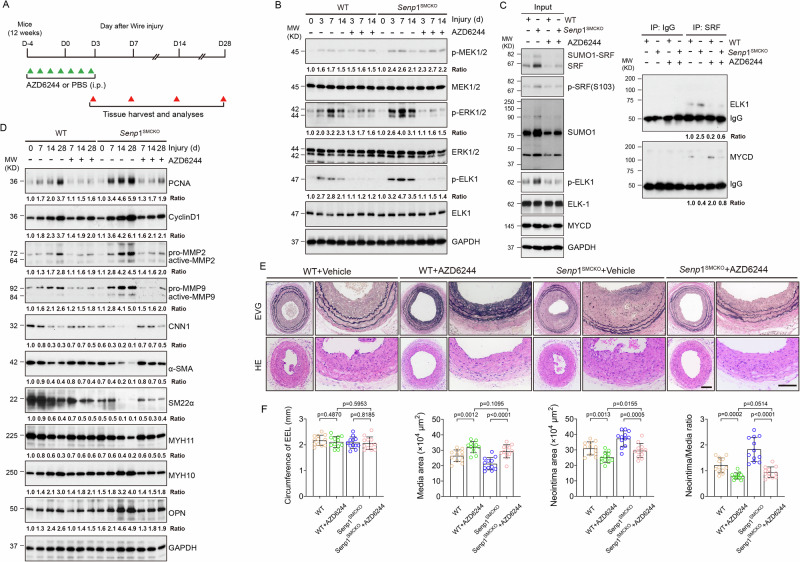

Blocking shift from SRF-myocardin to SRF-ELK complex by AZD6244 inhibits injury-induced neointimal formation

AZD6244 drastically disrupted PDGF-BB-induced SRF-ELK1 complex while partially restoring the association of SRF with myocardin (see Fig. 3C). These observations prompted us to test the therapeutic potential of AZD6244 in vascular remodeling. To this end, 12-week-old WT and Senp1SMCKO mice received injection of AZD6244 (25 mg/kg) or vehicle (PBS) once daily from 4 days prior to carotid artery injury (day 0) to 3 days after injury (D-4 to D3) as indicated (Fig. 7A). We first performed a series of biochemical analyses to determine effects of AZD6244 on the SRF-ELK signaling in these mice. Although AZD6244 had no inhibitory effects on p-MEK1/2 or total ERK1/2, as previously reported37, it markedly reduced phosphorylation of MEK downstream targets ERK1/2 and ELK1 on days 3–14 post-surgery (Fig. 7B). Importantly, phosphorylation levels of ERK1/2 and ELK1 did not differ between WT and Senp1SMCKO mice after AZD6244 treatment, suggesting that AZD6244 abolished the effect of VSMC-specific Senp1 deletion mediated MEK1/2-ERK1/2-ELK1 pathway in injury-induced carotid artery (Fig. 7B). Of note, AZD6244 reduced SRF, phospho-SRF, SUMO1 and SUMOylated SRF at 7 days after wire injury without any effects on expressions of total ELK or myocardin (Fig. 7C). However, AZD6244 dramatically attenuated the injury-induced SRF-ELK1 complex while restoring SRF-myocardin complex formation in Senp1SMCKO mice (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7. Blocking shift from SRF-myocardin to SRF-ELK complex by AZD6244 inhibits injury-induced neointimal formation.

A A diagram for AZD6244 injection protocol. 12-week-old WT and Senp1SMCKO mice were received injection of AZD6244 (25 mg/kg) or vehicle (PBS) once daily from 4 days before carotid artery injury to 3 days after injury (D-4 to D3). Artery tissues were harvested on D3, D7, D14 and D28. B Carotid artery tissues were subjected to western blot for the MEK-ERK-ELK1 signaling. C Carotid artery tissues were subjected to co-immunoprecipitation assays with anti-SRF followed by western blot with anti-ELK1 and anti-myocardin. D Carotid artery tissues were subjected to western blot for the VSMC proliferation, migration and phenotypic markers. Each tissue sample in (B–D) was pooled from three individual aortas and protein bands were quantified by densitometry and fold changes are presented by taking non-injured WT carotid arteries as 1.0. Additional two experiments were performed with different biological repeats presented in Supplementary Fig.12. E Representative photomicrographs of EVG staining and HE staining of carotid arteries harvested on day 28 post-injury from WT and Senp1SMCKO mice. F Circumference of EEL, neointimal area, media area, and neointima/media ratio in carotid arteries were measured (n = 12 left carotid arteries per group). Data are mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. Scale bars, 50 μm (E). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To test whether AZD6244-mediated suppression of the SRF-ELK1 axis in VSMCs results in a corresponding reduction in SRF-ELK1 activity, we detected the transcription levels of their downstream target genes by western blot and qRT-PCR. Consistent with altered phosphorylated ELK1 levels and its binding with SRF, AZD6244 reduced the expression of SRF-ELK1-mediated synthetic markers (MYH10 and OPN) but increased that of SRF/myocardin-mediated contractile markers (CNN1, α-SMA, SM22α, and MYH11) (Fig. 7D). Moreover, AZD6244 treatment suppressed the expression of proliferation markers (PCNA and CyclinD1), and increased the activities of migratory proteins (MMP2 and MMP9), as evident by their cleavage in injured arteries (Fig. 7D). AZD6244 treatment significantly inhibited injury-induced expression of Col15a1, Col5a2, Col6a2, Timp1, and Mmp14 at 28 days after wire injury in either WT or Senp1SMCKO mice as determined by qRT-PCR (Fig. S11).

We then performed a series of morphological and immunohistochemical analyses to determine the effects of AZD6244 on vascular structure, VSMC proliferation, and phenotypic switch by evaluating the carotid arteries of WT and Senp1SMCKO mice on day 28 post-injury. Senp1 deficiency enhanced neointima formation, and AZD6244 treatment significantly decreased the neointima areas and neointima/media ratios. However, aortic parameters between the WT and Senp1SMCKO mice did not differ after AZD6244 treatment (Fig. 7E, F), suggesting that AZD6244 abolished the effects of Senp1 deficiency on vascular remodeling.

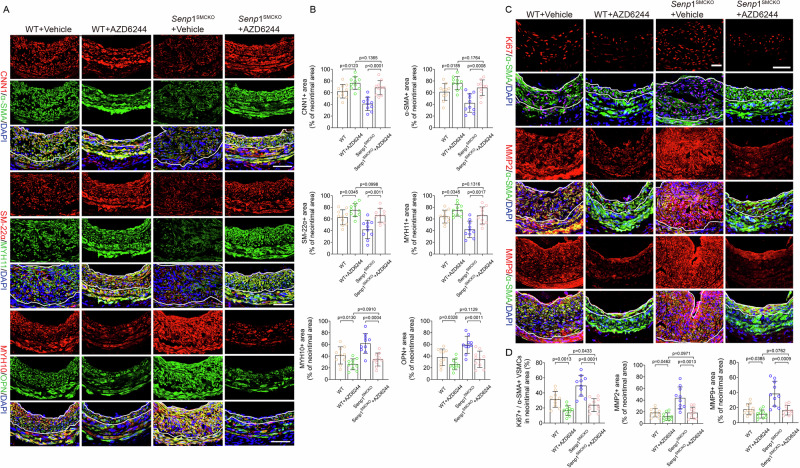

The effects of ADZ6244 on VSMC contractile and synthetic markers were then verified by immunostaining. AZD6244 treatment in Senp1SMCKO mice suppressed the augmented expression of SRF-ELK1 downstream targets MYH10 and OPN but rescued that of the SRF-myocardin targets CNN1, α-SMA, SM22α, and MYH11 (Fig. 8A, B). Moreover, AZD6244 treatment in injured arteries suppressed PCNA and cyclin D1 expression from day 7 to day 28 post-injury, consistent with the sustained inhibition of proliferation in AZD6244-treated mice visualized by Ki67 staining. The proliferative marker levels between WT and Senp1SMCKO mice after AZD6244 treatment did not differ (Fig. 8C, D). Consistent with the decrease in active MMPs detected by western blot, immunohistochemical staining showed a significant decrease in the percent of neointimal area that stained positive for MMP2 or MMP9 in both WT and Senp1SMCKO mice after AZD6244 treatment, but no significant differences in the percent of neointimal area stained positive for MMP2 or MMP9 between WT and Senp1SMCKO mice treated with AZD6244 (Fig. 8C, D). Taken together, these data suggest that AZD6244 inhibits vascular injury-induced VSMC proliferation, migration, phenotype switch, and neointimal formation in Senp1SMCKO mice by blocking the SRF-ELK signaling pathway.

Fig. 8. Blocking shift from SRF-myocardin to SRF-ELK complex by AZD6244 inhibits injury-induced VSMC phenotype switch.

AZD6244 injection protocol in WT and Senp1SMCKO mice were performed as described in Fig. 7. A, B Carotid artery tissues were subjected to immunofluorescence staining with VSMC contractile and synthetic markers. A Representative images are presented. B Fractional areas of the neointima occupied by each marker were quantified (n = 10 left carotid arteries per group). C, D Carotid artery tissues were subjected to immunofluorescence co-staining of α-SMA (green) with Ki67, MMP2 or MMP9 (red) with DAPI counterstaining for nuclei (blue). C Representative images are presented. D Ki67+α-SMA+ VSMCs, and fractional areas of the neointima occupied by MMP2+ or MMP9+ cells were quantified (n = 10 left carotid arteries per group). Data are mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. Scale bars, 50 μm (A, C). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

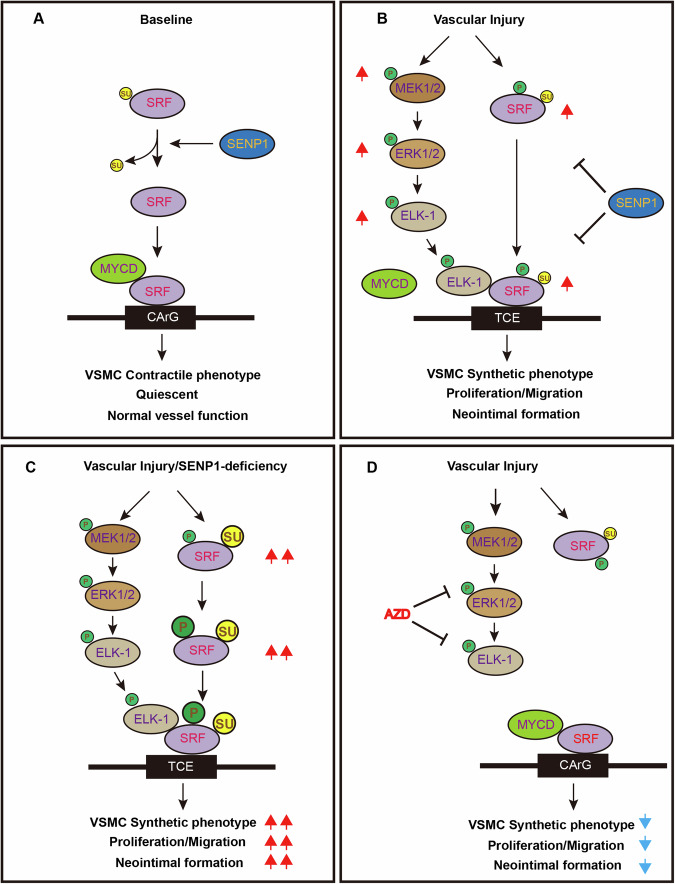

In our present study, we report that SRF SUMOylation modulates the VSMC responses to PDGF-BB in cultured cells and to vascular injury in murine models. We demonstrate that SENP1 deficiency in VSMCs accelerates injury-induced VSMC proliferation, migration, and phenotypic switch, promoting neointimal formation and vascular remodeling. Our analyses of human CAD specimens reveal a striking correlation among SRF expression, SUMO1 level, ELK activation, VSMCs phenotypic switch, and CAD severity. Mechanistically, SENP1 deficiency in VSMCs induces SUMO1-conjugated SUMOylation of SRF at K143 and promotes its phosphorylation and translocation from the lysosomes to nucleus, thereby increasing SRF stability in the nucleus; moreover, SUMO1-modified SRF switches its binding partner from myocardin to ELK1, accelerating VSMC proliferation, migration, and synthetic phenotype switch during vascular remodeling. These findings identify a novel function of SENP1-mediated deSUMOylation in orchestrating the complex process of vascular remodeling. Importantly, pharmacological inhibition of ELK1 activity by AZD6244 prevents the shift from SRF-myocardin to SRF-ELK complex, attenuating VSMC proliferation, migration, and neointimal formation (Fig. 9), thus providing a potential therapeutic target for CVD treatment.

Fig. 9. A model for the SRF SUMOylation and the SRF-ELK1 complex mediated vascular remodeling.

A Under normal condition, SRF is present in a deSUMOylation state and retains its binding with MYOCD to maintain the VSMC contractile phenotype. B In response to vascular injury, activated ELK1 and increased SUMOylated and phosphorylated SRF form a complex and induce VSMC synthetic phenotypic switch, VSMC proliferation and migration, leading to neointimal formation. C SENP1 deficiency in VSMCs dramatically increases SUMO1-mediated SRF SUMOylation at lysine 143, promotes SRF phosphorylation and the SRF-ELK1 complex, which augments VSMC phenotypic switch and neointimal formation. D Pharmacological inhibition of phospho-ELK1 by AZD6244 prevents the SRF-ELK complex and/or restores the SRF-MYOCD complex, attenuating the excessive proliferation, migration, and neointimal formation. AZD AZD6244, CArG CA(A/T)6G box, MYOCD myocardin, TCE ternary complex element, Su SUMO1, P phosphorylation.

Notably, SUMOylation of other protein targets in VSMCs have been reported. SUMOylated KLF4 reportedly plays an important role in PDGF-BB-induced VSMC proliferation by reversing the transactivation of KLF4 on p2138. In our study, KLF4 protein expression and nuclear localization were not altered by SENP1 deficiency. It is unclear if SENP1 regulates KLF4 complex formation in VSMCs. Alternatively, KLF4 SUMOylation is regulated by other SENPs. SUMOylation of PKD2 channels regulates its membrane recycling and is necessary for intravascular pressure-induced arterial contractility39. Similarly, SUMOylation of Runx2 (Runt-related transcription factor) in VSMCs causes Runx2 degradation, thereby preventing atherosclerotic calcification in mouse models40. Further studies are needed to examine whether SENP1-mediated deSUMOylation regulates PKD2 or Runx2 in VSMCs during vascular remodeling. A key finding of the present study is that SUMO1-mediated SRF SUMOylation is increased in PDGF-BB-treated VSMCs and in wire injury-induced mouse carotid arteries, and is further augmented by SENP1 deficiency. Moreover, increased SUMO1 levels and SRF SUMOylation were correlated with VSMC phenotypic switch from contractile to synthetic state. Under SENP1 deficiency, SUMOylation induces high stability of SRF protein and alters its binding partners in VSMCs. In response to vascular injury, VSMCs undergo phenotypic switching from contractile phenotype to a dedifferentiated synthetic state, and then redifferentiation29. Our study suggests that the SRF SUMOylation at K143 controls the SRF-ELK complex formation and VSMC phenotypic switch. SRF, the key mediator of gene transcription and function in VSMCs6,10, functions with two families of signal-regulated cofactors. Of these, three ternary complex factors (TCFs)-ELK1, Net, and SAP1-are regulated by Ras-ERK signaling, while the myocardin/MRTFs are regulated by the Rho-actin pathway4. Our study reveals that SRF SUMOylation plays a critical role in mediating the SRF complex competition and VSMC phenotypic switch. We provide the following evidence: (1) SENP1 deficiency in VSMCs induced SUMO1-mediated SRF SUMOylation, increased SRF protein level, but not mRNA level, in mouse aorta and isolated VSMCs; SRF SUMOylation promoted SRF localization from the lysosomes to the nucleus, protecting SRF against degradation. (2) SENP1 deficiency in VSMCs promoted SRF binding switch from SRF-myocardin to SRF-ELK1 complex, resulting in VSMC conversion from contractile to synthetic state; and (3) Moreover, SUMOylation at K143 of SRF, together with ELK1 phosphorylation, are required for SRF-ELK1 complex formation and subsequent VSMC phenotypic switch. Importantly, preventing the shift from SRF-myocardin to SRF-ELK complex by AZD6244 attenuates neointimal formation in Senp1-deficient mice.

The neointimal formation, a hallmark of vascular remodeling in CVD, is associated with a significant increase in VSMC migration, proliferation, and phenotypic switch41. The clinical significance of our study is that we established abnormal protein SUMOylation and phospho-ELK in human intimal hyperplasia, and demonstrated its correlation with VSMC phenotypic switch and neointimal formation. A few studies have shown that post-translational modification contributes to the initiation and progression of intimal hyperplasia. Notably, protein SUMOylations have been proposed to play a key role in promoting VSMC proliferation and may provide potential targets for treatment and prevention of intimal hyperplasia25,42–44. However, to date, there are no reports showing a direct association between SUMOylation and VSMC fate in human intimal hyperplasia. Our findings in human CAD specimens demonstrated that the SRF SUMOylation and the SRF-ELK1 complex serve as a link between PDGF-BB/vascular injury and neointimal formation. We showed that SRF, SUMO1, and phospho-ELK1 levels increased in VSMCs on PDGF-BB stimulation, and SENP1 deficiency augmented these responses. Moreover, SRF, SUMO1, and phospho-ELK1 levels were higher in luminal VSMCs from CAD groups compared with the normal coronary arteries, progressively increasing with the disease severity. Accordingly, VSMCs in human intimal hyperplasia exhibited phenotypic switches (with gain of synthetic markers and loss of contractile markers) and correlated with the expression of SRF, SUMO1, and phospho-ELK1 and the I/M ratios. It is noteworthy that SUMOylation can keep ELK1 in an inactive state under basal conditions via the binding of a SUMO-histone deacetylase complex and the control of its nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling34. The activation of ERK1/2 triggers a de-SUMOylation of ELK1, promotes the phosphorylation and activation of ELK1, leading to a transcriptionally active state34. In our study, phospho-ELK1 expression were increased in VSMCs after Senp1 deficiency. However, SUMO-conjugated ELK1 was not observed in the aortic lysates with or without Senp1 deficiency. Similarly, SENP1 deficiency in VSMCs had little effect on the SUMOylation of KLF4 or myocardin although they have been previously reported to be themselves SUMO substrates. However, we found that SENP1 deficiency in VSMCs had profound effects on SRF SUMOylation. The SUMOylation of KLF4, myocardin and ELK1 could be regulated by other SENP members such as SENP2 which need more investigations.

An important clinical implication of our study is that we provided a proof-of-concept for CAD treatment with AZD6244 by inhibiting the SRF-ELK1 axis while restoring the SRF-myocardin complex. A pharmacological MEK1/2 inhibitor, U0126, reportedly blocked the phosphorylation of ELK1, prevented PDGF-BB-induced association of ELK1 and SRF, and promoted SRF binding to myocardin, thus attenuating the suppressive effects of PDGF-BB on expression of contractile phenotype-related genes45. Local or systemic administration of another MEK1/2 inhibitor, PD98059, was found to suppress ERK1/2 activation, its target gene expression, and neointima formation in carotid artery injury model46,47. These reports indicate that MEK1/2 inhibition may represent a therapeutic strategy for the prevention of neointima formation. AZD6244 is a highly selective non-ATP-competitive MEK1/2 inhibitor that inhibits ERK1/2 phosphorylation without inhibiting p38α, MKK6, EGFR, ErbB2, or B-Raf48,49. We demonstrate that AZD6244 specifically blocked the ERK1/2-ELK1 pathway. Importantly, AZD6244 disrupted the SRF-ELK1 complex and promoted SRF-myocardin complex formation, corresponding to suppression of VSMC synthetic phenotype and attenuated neointimal formation. Thus, our study demonstrates that the SRF complex switch is an essential mechanism regulating VSMC phenotypic switch and neointimal formation associated with vascular injury and provides an attractive target for pharmacological treatment of CVD.

Methods

Our research complies with all relevant ethical regulations. All procedures involving human samples complied with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of the First People’s Hospital of Changzhou and Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, The Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School. Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects enrolled into this study. Mice were cared for in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines, and all procedures were approved by the Yale University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Clinical specimens

Human coronary arteries were obtained from cardiac transplant recipients (total n = 9; averaged ages are 66.67 ± 4.39) with chronic rejection undergoing no or re-transplantation (n = 3), cardiomyopathy recipients undergoing first-time transplantation (n = 6), and organ donors without cardiac disease (total n = 6; averaged ages 50.20 ± 4.15). Written informed consents were obtained from all surgical recipient patients and a family member of all deceased organ donors. The baseline characteristics of the patients are listed in Supplementary Table 1, including sex, smoking history, hypertension, lipid profiles and diabetes. Our procurement techniques have been described previously50,51. Briefly, for each arterial sample procured in the operating room, disease was macroscopically diagnosed by an experienced cardiac surgeon. Half of each sample was formalin-fixed immediately for paraffin-embedding and the other half was stored at −80 °C. Aortic pathologies were examined for plaque rupture, fibrocalcific plaques and fibroatheroma.

Animal study

Mice were housed in the animal care facility of Yale University under standard pathogen-free conditions (temperature, 20–24 °C; relative humidity, 45–65) with a 12 h light/dark schedule and provided with food (D10001, AIN-76A Rodent Diet; Research Diets, Inc.) and water ad libitum. Both male and female adult mice were used in all experiments without significant differences between male and female within the same group and we presented data primarily from the male mice. We used a previously generated conditional gene knockout mouse model lacking Senp1 specifically in VSMCs (Senp1SMCKO)24. We used EC-specific Senp1 deletion line (Senp1ecKO) as control22–25. The carotid arteries of C57BL/6, Senp1lox/lox (WT) and Senp1SMCKO mice (both having C57BL/6 background for more than six generations) were genotyped by western blot, quantitative RT-PCR, and immunofluorescence staining.

Carotid artery wire injury mouse model

Wire injury was performed in Senp1lox/lox (WT) and Senp1SMCKO mice (10–12-weeks-old) as described previously27. Briefly, mice were anaesthetized by intraperitoneally injecting ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). The left carotid artery was carefully dissected, under a dissecting microscope, through a midline neck incision. The external carotid artery was ligated with an 8-0 suture immediately proximal to the bifurcation point. Vascular clamps were applied to interrupt the internal and common carotid arterial blood flow. A transverse incision was made immediately proximal to the suture around the external carotid artery. A guidewire (0.38 mm diameter; No. C-SF-15-15; Cook, Bloomington, USA) was then introduced into the arterial lumen towards the aortic arch and withdrawn ten times with an angular rotating motion. After carefully removing the guidewire, the vascular clamps were removed and blood flow was restored. Finally, the skin incision was closed. A similar procedure without wire injury on the right common carotid artery was performed to serve as control. The common carotid artery tissues were collected at specific time points after surgery for morphological and biochemical analyses.

AZD6244 treatment

AZD6244 (Selumetinib, Catalog No. S1008, Selleckchem, TX, USA) was dissolved in 0.5% hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose and 0.4% polysorbate (Tween80). WT and Senp1SMCKO mice were intraperitoneally injected with freshly prepared AZD6244 (25 mg/kg) daily for 1 week (4 days before wire injury and 3 days after)52. Aortic VSMCs isolated from WT and Senp1SMCKO mice or MOVAS-1 cells were serum-starved for 24 h and stimulated with human PDGF-BB (10 ng/mL; Catalog #220-BB; R&D Systems, MN, USA) for different periods with or without AZD6244-pretreatment (0.5 μmol/L) for 12 h53. Thereafter, VSMCs or MOVAS-1 cells were harvested for RNA and protein extraction or immunostaining. PBS served as a vehicle control.

Histological and morphometric analyses

Mice were euthanized by an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). Common carotid artery tissues were perfused and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, embedded in paraffin, and 6 μm-thick sections were used for elastic van gieson (EVG) or hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining after deparaffinization and rehydration. Serial cross-sections (6 μm) of the entire region (300 μm) at the bifurcation site of the left carotid artery were obtained. The normal carotid artery thickness was determined based on the circumference of external elastic lamina (EEL), luminal area, and media area. The extent of neointimal formation 28 days after injury was determined based on the circumference of EEL, intima, media, and intima/media ratio. Images were quantified with Image-Pro Plus software (version 6.0, Media Cybernetics, MD, USA) by a single observer who was blinded to the treatment protocols.

Left main coronary artery sections were stained with HE and EVG, and images were obtained from two discontinuous slides per patient at a final magnification of ×40. Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used for morphometric analyses. Intimal (I) and media (M) thickness were measured, and their ratio and plaque stages were used to grade the severity of atherosclerosis. The means of these parameters from four different areas on each slide were calculated. Left main coronary arteries with an I/M ratio <0.2 were considered to have no or mild disease; 0.2–1 were considered to have moderate disease; and >1 or with calcification were considered to have severe disease.

VSMCs isolation and culture

Primary aortic VSMCs were isolated from WT and Senp1SMCKO mice according to elastase/collagenase digestion protocols54 with slight modifications. Briefly, thoracic aortas were carefully isolated and dissected away from connective tissues under a light microscope. Six thoracic aortas were pooled for each group of VSMC isolation. The isolated aortas were digested in HBSS containing 1 mg/mL collagenase A (10103578001, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) for 5 min at 37 °C to promote adventitia removal. The denuded vessels were incubated with 0.5 mL Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Thermo Fisher, MA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Life Technologies, NY, USA), 1.5 mg/mL collagenase A, 0.5 mg/mL elastase (LS006365, Worthington, NJ, USA), and antibiotics at 37 °C for 30 min, while the digest was triturated with a pipette every 15 min. The mixture was centrifuged, then the cells were resuspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (PenStrep, GIBCO-Invitrogen, NY, USA), and cultured in 35-mm dishes in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C. After the primary cells reached 90% confluency, they were digested, and the lysate was used for western blot analysis. Early-passage (passage 3–4) VSMCs were used in all experiments.

MOVAS-1 cell line (Cat: #ATCC®CRL-2797™), derived from aortic smooth muscle cells of male C57BL/6J mice, was purchased from American type culture collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). MOVAS-1 cells were cultured in DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Bulk RNA-sequencing and gene expression analysis

Total RNA extracted from aorta samples of WT and Senp1SMCKO mice at basal or at 14 days after wire injury was subjected to bulk RNA-seq analysis. RNA integrity was assessed using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit on the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent). Sequencing libraries were generated using the rRNA-depleted RNA by NEBNext® Ultra™ Directional RNA Library Prep Kit from Illumina® (NEB, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq 4000 platform, and bp paired-end reads were generated. The raw reads were assessed for quality using FastQC and mapped to the reference genome using HISAT2 (v2.0.4), and gene expression levels were quantified using Cuffdiff (v2.1.1). Differential expression analyses were performed using the DESeq2 R package. Genes with an absolute fold change (FC) > 1.5 and a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 were considered as differentially expressed genes. Volcano plot was generated using the open sources R language. Heat maps were generated by MEV (Multi-Experiment Viewer) program. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was carried out with the DAVID 6.8 online analysis system (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp). The bulk RNA-seq of carotid arteries is publicly available at NCBI site as BioProject: PRJNA1139223.

Examination of proliferative ability

We assessed VSMC proliferation using 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (Edu) incorporation assay and Ki67 staining. For Edu incorporation assay, cells were incubated with 10 µM Edu for 4 h before fixing in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 37 °C. The fixed cells were assayed using the Click-iT Edu kit (C10646, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). For Ki67 staining, Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and subjected to Ki67 staining according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Images were captured by LSM880 laser confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Data are presented as the ratio of Edu-or Ki67-positive cells to total α-SMA-positive VSMCs.

Examination of migratory ability

In vitro migratory activity of VSMCs was measured using a scratch assay. VSMCs (1×105 cells/well) were seeded in six-well plates and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. At 90% confluence, the growth medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 0.2% FBS. After 24-h starvation, a wound was created by scraping the cell monolayer with a 200 μL sterile pipette tip across the center of the well. We further assessed VSMC migratory activity using Transwell migration assay. VSMCs (1.5 × 104 cells/well) were plated in the upper Transwell chamber. The pore size of insert was 8 μm. After 24-h culture, the VSMCs that migrated to the lower chamber were fixed with methanol and stained with 1% crystal violet. These migrated VSMCs were quantified in four randomly selected areas at ×100 magnification using Cellsens Dimension 1.15 software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Plasmids and transfection

HA-SUMO1 was purchased in Addgene (Cambridge, MA, USA). To obtain Flag-SRF, full-length SRF (mouse, Locus ID 20807) was purchased from ORIGENE (CAT#: TL502142) and cloned into p3xFlag-Myc-CMV-24 vector. Various Flag-SRF mutations (K143R, K131R, K161R) were generated using SUMOylation prediction websites (SUMOplot, JASSA, and GPS-SUMO) and primers were listed in Supplementary Table 2. MOVAS-1 cells (~80% confluent) were transfected with the desired plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 following the manufacturer’s instructions. In most experiments, equimolar ratios of plasmids were used for co-transfection experiments, and the total amount of plasmids was adjusted with the empty vector. To ensure that the various plasmids express comparable levels of the proteins, a two-fold amount of Flag-SRFK143R plasmid, as compared to wild-type Flag-SRF, was used for transfection in some experiments.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA from mouse carotid artery tissue or cells was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher). Purified RNA (500 ng) was reverse transcribed using PrimerScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Japan) and 1 μg of cDNA was used to perform quantitative RT-PCR with LightCycler 480 Real-time PCR system (Roche) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Immunofluorescence staining

Cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in glass-bottomed culture dishes, fixed with freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. The paraffin-embedded mouse carotid artery sections (6 μm-thick) and paraffin-embedded human coronary artery sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. After permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, the sections or cells were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Normal isotype IgG was used as negative control. After washing with PBS, the samples were incubated with secondary antibodies for 2 h at 37 °C in the dark. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI, and sections were visualized using an LSM880 laser confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Antibodies used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Quantification of immunofluorescence images

Quantification of Immunofluorescence Images in the aortas were performed as we previously described50,51. Immunofluorescence images were acquired using an LSM880 laser confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany) equipped with a ×40 objective. Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used for quantitative analyses. The neointimal area was determined by subtraction of the lumen area from the area circumscribed by the internal elastic lamina traced on stained sections. The medial area was defined as the area between an external elastic lamina and internal elastic lamina. Measurements were obtained from two discontinuous sections per sample. Two different fields per murine section and four different fields for human samples and cultured VSMCs are analyzed, and the minimum number of cells counted per field was fifty in human and murine samples and thirty in cultured VSMCs. For quantitative analysis of MMP2, MMP9, CNN1, α-SMA, SM22α, MYH11, MYH10 or OPN staining, the positively stained areas were manually measured in a blind fashion. The neointimal area in human left main coronary arteries, carotid artery after wire injury or media area in un-injury carotid artery was shown as 100%. For quantitative analysis of Ki67, p-ELK1, SRF, cleaved caspase-3 or SUMO1 staining, the number of cells with positively stained or each marker was manually calculated in a blind fashion. The α-SMA- positive VSMCs in human left main coronary arteries, neointimal area of carotid artery after wire injury or media area in un-injury carotid artery was shown as 100%. For quantitative analysis of Edu staining, the number of Edu-positive stained VSMCs were manually calculated in a blind fashion. The number of α-SMA- positive VSMCs was shown as 100%.

Protein extraction and western blot analysis

Human or murine arterial tissue or in vitro cell lysates were prepared using 1× cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technologies, MA, USA) containing protease inhibitors (Cat. 04693159001, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). As the protein concentration from a single mouse carotid artery tissue was low, we pooled tissue samples from three individuals for protein extraction. The extracted proteins were electrophoresed on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (0.45 μm, Bio-Rad, CA, USA). Each membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline and 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) for 2 h and then incubated with the primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. The membrane was washed and incubated with the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody in 5% non-fat milk in TBST buffer for 2 h. Antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Proteins were detected using a Chemiluminescence Detection Kit (sc-2048, Santa Cruz, TX, USA) and band intensities were quantified by densitometry with ImageJ software. For data presented in the same figure panel, the samples were derived from the same experiment and that gels/blots were processed in parallel. Uncropped blots and gel images were provided in the Source Data file.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay

The tissues or cells were lysed in lysis buffer A (30 mM Hepes pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and protease inhibitor mixture) on ice for 10 min, centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min at 13,000 rpm, and 500 μg of cell lysate was incubated with 5 μg of the indicated primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. Anti-IgG served as the negative control. The immune complexes were purified with 20 μL protein A/G agarose at 4 °C for 6 h, centrifuged, washed with ice-cold cell lysis buffer, and analyzed by immunoblotting. The antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Uncropped blots and gel images were provided in the Source Data file.

Cycloheximide (CHX) assay

To assess protein stability, cells were seeded into 12-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well, cultured for 24 h, and transfected with indicated plasmids. After treatment with CHX (100 ng/mL) for indicated time periods, cells were harvested and steady-state target protein levels were determined by western blot.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic preparations

Cells were fractionated using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Cat. 78833; Thermo Fisher) according to manufacturer’s instructions to obtain nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS, incubated with cytoplasmic extract reagent I for 10 min, followed by ice-cold cytoplasmic extract reagent II, and centrifuged for 5 min to obtain the cytoplasmic extract. The insoluble fraction was incubated with ice-cold nuclear extract reagent for 40 min and centrifuged for 10 min to obtain the nuclear extract.

Statistical analyses

Group sizes were determined by a priori power analysis for a two-tailed, two-sample Student’s t test with an α of 0.05 and power of 0.8, in order to detect a 10% difference in lesion size at the endpoint. All quantifications (artery morphometrical analyses, immunofluorescent analyses, protein and mRNA levels) were performed in a blind fashion. The data were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism, version 8.0.1 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) and SPSS, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc.). All graphs report mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) values of biological replicates. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check normality, and Bartlett’s test was used to check equal variance. Comparisons between two and more than two groups were performed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test or by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, respectively, using Prism 8.0.1 software (GraphPad). Correlation analyses between variables were performed using the Pearson rank correlation test. Two-tailed p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by NIH grants US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants HL157019 and R01EY033333. We appreciate Al Mennone’s help in acquiring images at the Yale University Center for Cellular and Molecular Imaging (CCMI). We thank Guofeng Xu (the First People’s Hospital of Changzhou, Changzhou, Jiangsu, China) and Dr. Min Zhou’s group for clinical specimens. The sequencing service was conducted at the Yale Stem Cell Center Genomics Core facility and was supported by the Connecticut Regenerative Medicine Research Fund.

Author contributions

Y.X., W.M. and J.H.Z. provided conceptual of the study and designed all the experiments; H.Z. for mouse breeding, genotyping, in vivo Western blotting; Y.C. and M.Z. for the clinical specimens; Y.X., W.M. and J.H.Z. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. J.S.P. for advice and suggestions.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Bin Zheng, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The bulk RNA-seq of carotid arteries is publicly available at NCBI site as BioProject: PRJNA1139223. All data, including data associated with main figures and Supplementary Figs., are available within the article or in the online-only Data Supplement. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Min Zhou, Email: zhouminnju@nju.edu.cn.

Jenny Huanjiao Zhou, Email: Jenny.zhou@yale.edu.

Wang Min, Email: mike.wang388@gmail.com.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-51350-5.

References

- 1.Dzau, V. J., Braun-Dullaeus, R. C. & Sedding, D. G. Vascular proliferation and atherosclerosis: new perspectives and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Med.8, 1249–1256 (2002). 10.1038/nm1102-1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basatemur, G. L., Jorgensen, H. F., Clarke, M. C. H., Bennett, M. R. & Mallat, Z. Vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol.16, 727–744 (2019). 10.1038/s41569-019-0227-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett, M. R., Sinha, S. & Owens, G. K. Vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res.118, 692–702 (2016). 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gualdrini, F. et al. SRF co-factors control the balance between cell proliferation and contractility. Mol. Cell64, 1048–1061 (2016). 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owens, G. K., Kumar, M. S. & Wamhoff, B. R. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol. Rev.84, 767–801 (2004). 10.1152/physrev.00041.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang, Z. et al. Myocardin and ternary complex factors compete for SRF to control smooth muscle gene expression. Nature428, 185–189 (2004). 10.1038/nature02382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park, C. et al. Serum response factor-dependent MicroRNAs regulate gastrointestinal smooth muscle cell phenotypes. Gastroenterology141, 164–175 (2011). 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito, S. et al. MRTF-A promotes angiotensin II-induced inflammatory response and aortic dissection in mice. PLoS ONE15, e0229888 (2020). 10.1371/journal.pone.0229888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minami, T. et al. Reciprocal expression of MRTF-A and myocardin is crucial for pathological vascular remodelling in mice. EMBO J.31, 4428–4440 (2012). 10.1038/emboj.2012.296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]