Abstract

Objective

Positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) may occur in the setting of interstitial lung disease (ILD), with or without ANCA‐associated vasculitis (AAV). We aim to compare the characteristics and clinical course of patients with ILD and positive ANCA (ANCA‐ILD) to those with negative ANCA.

Methods

We performed a single‐center retrospective cohort study from 2018 to 2021. All patients with ILD and ANCA testing were included. Patient characteristics (symptoms, dyspnea scale, and systemic AAV), test results (pulmonary high‐resolution computed tomography and pulmonary function tests), and adverse events were collected from electronic medical records. Descriptive statistics and the Fisher exact test were used to compare the outcomes of patients with ANCA‐ILD to those with ILD and negative ANCA.

Results

A total of 265 patients with ILD were included. The mean follow‐up duration was 69.3 months, 26 patients (9.8%) were ANCA positive, and 69.2% of those with ANCA‐ILD had another autoantibody. AAV occurred in 17 patients (65.4%) with ANCA‐ILD. In 29.4% of patients, AAV developed following ILD diagnosis. Usual interstitial pneumonia was the most common radiologic pattern in patients with ANCA‐ILD. There was no association between ANCA status and the evolution of dyspnea, diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide, and lung imaging. Forced vital capacity improved over time in 42% of patients with ANCA‐ILD and in 17% of patients with negative ANCA (P = 0.006). Hospitalization occurred in 46.2% of patients with ANCA‐ILD and in 21.8% of patients with negative ANCA (P = 0.006). Both groups had similar mortality rates.

Conclusion

Routine ANCA testing should be considered in patients with ILD. Patients with ANCA‐ILD are at risk for AAV. More research is required to better understand and manage patients with ANCA‐ILD.

INTRODUCTION

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) are a heterogeneous group of diseases that cause inflammation and/or fibrosis of the lung parenchyma. 1 , 2 They are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. 3 , 4 A key aspect in the management of ILD is early and accurate identification of possible treatable causes. 5 Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–associated vasculitis (AAV), namely granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic GPA, are an increasingly recognized cause of ILD. 6 , 7

ANCAs can have a potentially important pathogenic role in the development of ILD. Neutrophil‐releasing proteolytic enzymes (such as elastase) and neutrophil extracellular traps may contribute to the development of pulmonary fibrosis in patients with ANCA‐ILD. 8 On the other hand, pulmonary fibrosis itself can induce myeloperoxidase (MPO)‐ANCA production and the subsequent development of MPA through neutrophil activation and inflammatory response. 9 , 10 Despite evidence of a potential pathogenic association, ANCA testing is not routinely done in the workup for ILD and is not included in the serologic domain of the latest European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society research statement for interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features. 11 , 12

There is currently a knowledge gap on the role of routine ANCA testing in the workup for ILD. The proportion of ANCA positivity in ILD is not well described but ranges between 4% and 36% for MPO‐ANCA and 2% and 4% for proteinase‐3(PR3)‐ANCA, respectively. 13 , 14 ILD can occur early in the course of AAV and may be its first manifestation. 15 The prevalence rates of ILD in patients with AAV have been reported in up to 23% in GPA and up to 45% in MPA. 13 , 16 , 17 Therefore, a positive result could warrant clinical surveillance for other signs of AAV and referral to a vasculitis expert. However, some patients with ILD and positive ANCA may never develop overt vasculitis after many years of follow‐up. 16 , 18 , 19 There are sparse data regarding the clinical evolution and management of such patients. Therefore, the objective of this study is to compare the characteristics and clinical course of patients with ILD and positive ANCA with those with negative ANCA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records in our tertiary academic center. Charts from patients assessed at the outpatient ILD clinic and vasculitis clinic from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2021 were screened for inclusion. All patients were assessed by a vasculitis expert regardless of ANCA positivity.

Study population

Patients were included if all of the following criteria were met: (1) patient's age ≥18 years at diagnosis of ILD, (2) confirmation of ILD by an expert respirologist, (3) available ANCA results, and (4) completion of at least 6 months of follow‐up, with at least two visits during the study period. A lookback period was allowed; if the eligible visits occurred during the study period, charts were included even if the diagnosis of ILD was made before the study start date. For these patients, the first study visit corresponded to the first consultation for ILD outside the study period.

The study factor of interest was ANCA positivity. ANCA positivity was defined as positive ANCA by either enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (either PR3 or MPO) or by indirect immunofluorescence (IIF; either cytoplasmic‐ANCA or perinuclear‐ANCA). Atypical ANCAs by IIF were also considered positive.

The diagnosis of ILD was made by an experienced clinician based on a combination of symptoms, physical examination findings, pulmonary high‐resolution computed tomography (HRCT), and pulmonary function tests (PFTs). The classification and diagnosis of the ILD subtype was ascertained during a multidisciplinary meeting and confirmed by an expert respirologist at the last clinical visit recorded during the study period. The ILD subtypes included idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, connective tissue disease (CTD)‐ILD, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, sarcoidosis, and other ILDs. 3

Data collection

Data were collected for each patient visit at 6‐month intervals. Observations reflected all test results and events occurring in the previous 6 months. If >6 months elapsed between two visits, all results and events occurring since the previous visit were recorded.

Baseline characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity, past medical history, smoking history, recreational drugs, and environmental exposure), clinical features (ILD diagnosis, presence of systemic vasculitis, symptoms, hospitalizations, and mortality), laboratory investigations (ANCA results by IIF and/or enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay, and CTD autoantibodies), pulmonary HRCT results, and PFT results were collected from electronic health records. A diagnosis of AAV was made by a vasculitis expert in the presence of other systemic symptoms and signs of vasculitis, distinguished from ILD with ANCA positivity but without systemic symptoms. Pulmonary HRCT radiologic patterns were based on the consensus opinion of the pulmonary radiologist and the expert ILD respirologist.

Outcome measures

We assessed changes in (1) dyspnea, (2) the percentage of forced vital capacity (%FVC), (3) the percentage of the diffusion capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (%DLco), and (4) the radiographic appearance on pulmonary HRCT between the first and last study visit. Outcomes categories were created to reflect clinical significance. Improvement, deterioration, or stability in dyspnea was based on changes in the Medical Council Research dyspnea scale. 20 Improvement or deterioration of %FVC was defined as an increase or decrease ≥10% in its predicted value. Improvement or deterioration of %DLco was defined as an increase or decrease ≥15% in its predicted value. Stability was defined as variations in both %FVC <10% and %DLco <15% between the first and last clinic visit. Pulmonary HRCT evolution between the first and last visit was based on the consensus opinion of the pulmonary radiologist and treating ILD respirologist. The radiologist was blinded to clinical information, whereas the ILD respirologist was not. Secondary outcomes of interest included the proportion of patients with at least one hospitalization after ILD diagnosis (for any reason) and the proportion of all‐cause mortality.

Statistical analysis

Patients were divided in two strata: those with ILD and positive ANCA (ANCA‐ILD) and those with ILD and negative ANCA. Descriptive statistics were performed for baseline characteristics with means and SDs or medians and interquartile ranges when appropriate.

The Fisher‐Freeman‐Halton exact test was used to assess the crude association between ANCA status and the following categorical outcome variables: (1) changes in dyspnea, (2) changes in %FVC, (3) changes in %DLco, (4) changes on the HRCT of the lungs, (5) all‐cause hospitalization, and (6) all‐cause mortality. Multiple variable logistic regression models were not planned or conducted because of the small number of patients in the ANCA‐ILD strata.

A conservative adjusted two‐sided significance level of 0.008 (Bonferroni correction, n = 6, α = 0.05) was used to account for multiplicity in hypothesis testing. Missing data were recorded and reported, and a complete case analysis method was used to carry hypothesis testing. Statistical analysis was conducted with IBM SPSS version 27. This study was approved by the research ethics board of the Centre Intégré Universitaire de santé et de services sociaux du Nord‐de‐l’Île de Montréal (certificate number 2020‐1968). Participants’ informed and signed consent was waived for this retrospective chart review.

RESULTS

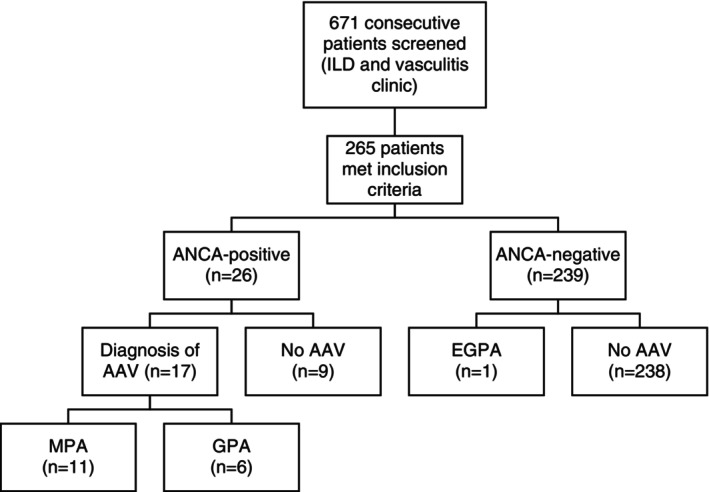

A total of 265 patients with ILD were included (Figure 1). The mean age of diagnosis of ILD was 69.3 (SD 10.6) years and 56.6% of patients were male. The mean duration of follow‐up was 69.3 (SD 10.6) months. Baseline characteristics and the final ILD and vasculitis diagnoses are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the 265 participants included in the retrospective cohort study. ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody; AAV, antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody–associated vasculitis; EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis; ILD, interstitial lung disease; MPA, microscopic polyangiitis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 265 patients with ILD according to ANCA status*

| Characteristics | Total (N = 265) | ANCA positive (n = 26) | ANCA negative (n = 239) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 69.3 (10.6) | 66.5 (9.7) | 69.6 (10.7) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 150 (56.6) | 13 (50.0) | 137 (57.3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 211 (79.6) | 19 (73.1) | 192 (80.3) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 6 (2.3) | 1 (3.8) | 5 (2.1) |

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 8 (3.0) | 3 (11.5) | 5 (2.1) |

| Black or African American | 9 (3.4) | 0 | 9 (3.8) |

| Asian | 29 (10.9) | 3 (11.5) | 26 (10.9) |

| Other | 2 (0.8) | 0 | 2 (0.8) |

| Any smoking history, n (%) | 179 (67.5) | 16 (61.5) | 163 (68.2) |

| Multiple autoantibodies, n (%) | 70 (26.4) | 18 (69.2) | 52 (21.8) |

| Rheumatoid factor | 50 (18.9) | 11 (42.3) | 39 (14.7) |

| Antinuclear autoantibodies | 51 (19.2) | 5 (19.2) | 46 (19.2) |

| Anti–Scl‐70 | 9 (3.4) | 2 (7.7) | 7 (2.9) |

| Anti‐SSA/Ro‐52 and/or anti‐SSB | 32 (12.1) | 2 (7.7) | 30 (12.6) |

| Myositis autoantibodies | 57 (21.5) | 4 (15.4) | 53 (22.2) |

| Previous autoimmune disease, n (%) | 77 (29.1) | 20 (76.9) | 57 (23.4) |

| Final ILD clinical diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| IPF | 88 (33.2) | 3 (11.5) | 85 (35.6) |

| iNSIP | 26 (9.8) | 2 (7.7) | 26 (10.9) |

| RB‐ILD | 8 (3.0) | 0 | 8 (3.3) |

| DIP | 12 (4.5) | 0 | 12 (5.0) |

| COP | 10 (3.8) | 3 (11.5) | 7 (2.9) |

| LIP | 3 (1.1) | 0 | 3 (1.3) |

| IPPFE | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Unclassifiable ILD | 63 (23.8) | 2 (7.7) | 61 (25.5) |

| SRIF | 5 (1.9) | 0 | 5 (2.1) |

| CTD‐ILD | 38 (14.3) | 6 (23.1) | 32 (13.4) |

| Others | 11 (4.2) | 10 (38.5) | 1 (0.4) |

| Vasculitis, n (%) | |||

| None | 247 (93.2) | 9 (34.6) | 238 (99.6) |

| MPA | 11 (4.2) | 11 (42.3) | 0 |

| GPA | 6 (2.3) | 6 (23.1) | 0 |

| EGPA | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

Myositis autoantibodies include anti‐SRP, anti‐PmScl75/100, anti‐Ku, anti‐Jo1, anti‐PL7, anti‐PL12, anti‐EJ, anti‐OJ, anti‐Ro52, anti‐MDA‐5, anti‐TIF1‐γ, anti‐Mi2a/b, anti‐NXP2, and anti‐SAE. ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody; COP, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia; CTD‐ILD, connective tissue disease–associated interstitial lung disease; DIP, desquamative interstitial pneumonia; EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis; ILD, interstitial lung disease; iNSIP, idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; IPPFE, idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis; LIP, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia; MPA, microscopic polyangiitis; RB‐ILD, respiratory bronchiolitis–interstitial lung disease; SRIF, smoking‐related interstitial fibrosis.

ANCA status

ANCAs were positive in 26 patients (9.8%) with ILD (Table 1). Among them, 14 patients (54%) were MPO‐ANCA positive, 9 patients (35%) were PR3‐ANCA positive, and 3 patients (11%) were positive for both MPO and PR3‐ANCA. MPO‐ANCA was positive at ILD diagnosis in 12 of 14 patients, and 2 became positive during follow‐up. PR3‐ANCA was positive in eight of nine patients at ILD diagnosis, and one became positive during follow‐up. In patients who were both MPO and PR3‐ANCA positive, two of three patients were positive at ILD diagnosis, and one became positive during follow‐up. ANCA assessed by IIF was positive in only one patient with a diagnosis of MPA.

Diagnosis of clinical vasculitis

Seventeen patients with ANCA‐ILD (65.4%) had a clinical diagnosis of AAV: MPA occurred in 11 patients (42.3%) and GPA in 6 patients (23.1%). All patients with ILD and AAV had a positive ANCA diagnosis except for one patient with eosinophilic GPA. In patients with a diagnosis of clinical vasculitis, nine (50.0%) had constitutional symptoms, four (22.2%) had otorhinolaryngeal manifestations, two (11.1%) had renal manifestations, and two (11.1%) had skin manifestations. In 12 patients (70.6%), the diagnosis of AAV and ILD was simultaneous, whereas 5 patients (29.4%) developed vasculitis after the onset of ILD. For these patients, the median time from ILD diagnosis to clinical vasculitis was 24 months (interquartile range 12–65 months).

Clinical diagnosis of ILD and ancillary tests results

The most frequent clinical ILD diagnosis was idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, followed by CTD‐ILD and idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia in 33.2%, 14.3%, and 9.8% of patients, respectively. Baseline ancillary tests, results, and therapies are reported in Table 2. There was no clinically significant difference in baseline PFTs between patients with ANCA‐ILD and patients negative for ANCA. The most reported HRCT result was usual interstitial pneumonia in the ANCA‐ILD group (38.5%) and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia in the ANCA‐negative group (43.1%). None of the patients with ANCA‐ILD had pulmonary hypertension on transthoracic echocardiogram or received home oxygen therapy, as compared to 12.6% and 15.6%, respectively, in the ANCA‐negative group.

Table 2.

Comparison of ancillary test results and therapies based on ANCA results in 265 patients with ILD*

| Ancillary test results and therapies | ANCA positive (n = 26) | ANCA negative (n = 239) |

|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary function test, mean (SD) | ||

| Mean % predicted FVC at baseline a | 90.5 (20.5) | 82.9 (20.4) |

| Mean % predicted FEV1 at baseline a | 91.2 (22.7) | 86.6 (22.5) |

| Mean FEV1/FVC (%) at baseline a | 77.3 (11.8) | 78.9 (10.8) |

| Mean % predicted DLco at baseline b | 56.7 (15.3) | 61.0 (17.5) |

| Pulmonary hypertension on TTE, n (%) c | 0 | 19 (15.6) |

| Pattern on pulmonary HRCT, n (%) | ||

| UIP | 10 (38.5) | 75 (31.4) |

| NSIP | 7 (26.9) | 103 (43.1) |

| RB‐ILD | 0 | 5 (2.1) |

| DIP | 0 | 14 (5.9) |

| COP | 3 (11.5) | 10 (4.2) |

| Other/not specified | 6 (23.1) | 32 (13.4) |

| Treatments, n (%) | ||

| Glucocorticoids | 15 (57.7) | 42 (17.6) |

| Immunosuppressants | 18 (69.2) | 48 (20.1) |

| Antifibrotics | 2 (7.7) | 41 (17.2) |

| Pirfenidone | 1 (3.8) | 22 (9.2) |

| Nintedanib | 1 (3.8) | 19 (7.9) |

| Home oxygen therapy | 0 | 30 (12.6) |

| All‐cause hospitalization, n (%) | 12 (46.2) | 52 (21.8) |

| All‐cause mortality, n (%) | 4 (15.4) | 48 (20.1) |

ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody; COP, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia; DIP, desquamative interstitial pneumonia; DLco, diffusion capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume during first second; FVC, forced vital capacity; HRCT, high‐resolution computed tomography; NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; RB‐ILD, respiratory bronchiolitis–interstitial lung disease; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

Missing or unavailable in two patients positive for ANCA patients and 28 patients negative for ANCA.

Missing or unavailable in three patients positive for ANCA and 40 patients negative for ANCA.

Missing or not performed in 10 patients positive for ANCA and 17 patients negative for ANCA.

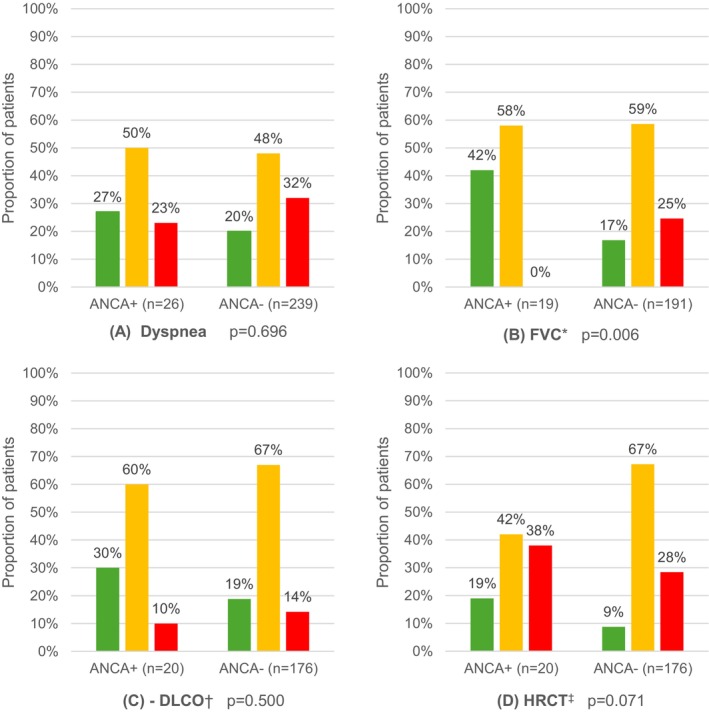

Clinical evolution over time

The clinical course of patients between the first and last visits is presented in Figure 2. There was no evidence of an association between ANCA status and dyspnea severity, predicted %DLco, and HRCT evolution over time. A higher proportion of patients with ANCA‐ILD (42%) showed improvement in the predicted %FVC compared to patients negative for ANCA (17%; P = 0.006). The proportion of all‐cause hospitalization was 46.2% in the ANCA‐ILD group and 21.8% in ANCA‐negative group (P = 0.006). Death occurred in 15.4% of patients with ANCA‐ILD versus 20.1% of patients negative for ANCA (P = 0.795).

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients with improvement, stability, or deterioration of dyspnea, %FVC, %DLco, and radiologic imaging between the first and last clinic visits according to the ANCA results. (A) Dyspnea severity evolution as per the Medical Research Council dyspnea scale. (B) Evolution of the percentage of the predicted FVC. (C) Evolution of the percentage of the predicted DLco. (D) Evolution of interstitial lung disease on pulmonary HRCT. Improvement is shown in green, stability in orange, and deterioration in red. aImprovement or deterioration of %FVC was defined as an increase or decrease of ≥10% in its predicted value. bThe improvement or deterioration of %DLco was defined as an increase or decrease of ≥15% in its predicted value. Stability was defined as variations in both %FVC <10% and %DLco <15% between the first and last clinic visit. cThe evolution of HRCT was based on the opinion of a pulmonary radiologist with an interstitial lung disease specialist. ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody; DLco, diffusion capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide; FVC, functional vital capacity; HRCT, high‐resolution computer tomography.

Other CTD‐ILDs and autoantibodies

A total of 63 patients with ILD (23.8%) had a history of autoimmune disease other than AAV: 6 patients (23.1%) in the ANCA‐ILD group and 57 patients (23.8%) in the ANCA‐negative group. The most common autoimmune diseases were systemic sclerosis, inflammatory myopathies, rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren syndrome. Moreover, 69.2% of patients with ANCA‐ILD had at least one other positive autoantibody. These included rheumatoid factor, anti–cyclic citrullinated peptides, CTD autoantibodies (anti‐Ro52/60, anti‐La, anti‐Scl70, and anti‐PM‐Scl75/100), and myositis autoantibodies (anti‐SRP, anti‐PmScl75/100, anti‐Ku, anti‐Jo1, anti‐PL7, anti‐PL12, anti‐EJ, anti‐OJ, anti‐Ro52, anti‐MDA‐5, anti‐TIF1‐γ, anti‐Mi2a/b, anti‐NXP2, and anti‐SAE).

DISCUSSION

In our study, ANCAs were positive in 26 patients (9.8%) with ILD. Clinical data from these patients will contribute to the sparse body of evidence available and inform areas of uncertainty where more research is required.

In patients with ANCA‐ILD, 65.4% had a concomitant diagnosis of AAV and ILD. However, in patients with ILD before clinical vasculitis, we cannot be sure of the exact timing of the ILD with respect to the clinical vasculitis. This is because lung imaging in healthy individuals is not routinely recommended. In our study, the most common AAV associated with ILD was MPA. This is consistent with previous reports. 9 , 21 , 22 In fact, the 5‐year incidence of MPA in patients with MPO‐ANCA‐ILD can be as high as 24.3%. 10

Previous studies have suggested the possible pathogenic roles of ANCA in the development of ILD. 8 In addition to the release of proteolytic enzymes and neutrophil extracellular traps, MPO‐ANCAs can also activate MPO, leading to the production of reactive oxygen species that cause direct pulmonary damage. 23 Finally, repeated subclinical, asymptomatic, micro‐alveolar hemorrhage caused by vasculitis can lead to fibrosis over time. 24

Routine testing of ANCAs in the evaluation of patients with ILD has potential prognostic and therapeutic implications. In patients with ANCA‐ILD, markers of inflammation should be monitored because elevated levels are associated with a worse prognosis. 25 Moreover, elevated markers of inflammation can also inform impending vasculitis. 19 , 26

We did not find an association between ANCA status and all‐cause mortality in patients with ILD. This is possibly because of improvements in therapies for AAV over the last decades. 27 , 28 , 29 We found that patients with ANCA‐ILD were more likely to be hospitalized, mostly because of the underlying AAV or immunosuppression‐related adverse events. In patients with ANCA‐ILD, improvement in %FVC over time was achieved in a higher proportion than in patients negative for ANCA. Although this difference was statistically significant, this result could be biased because of missing data and the small sample size.

More than half of the patients with ANCA‐ILD had at least one other concomitant autoantibody, such as rheumatoid factor, anti–cyclic citrullinated peptides, CTD, or myositis autoantibodies. Whether there is a synergetic role between ANCAs and the other concomitant autoantibodies in the development of ILD is unknown. The presence of multiple positive autoantibodies has been described in 18% to 66% of patients with AAV. 30 , 31 In our practice, patients with AAV without ILD rarely get an extensive workup to look for multiple positive autoantibodies. Thus, it is difficult to determine if the frequency of multiple positive autoantibodies in patients with ANCA‐ILD differs from patients with AAV without ILD.

Our study has several strengths. The study period and patient population were carefully chosen to reduce selection bias by including patients with ILD for whom ANCA testing was routinely performed. Clinical outcomes, such as clinical vasculitis, ILD clinical type, and ILD radiologic interpretation, were ascertained by a vasculitis expert, specialized ILD respirologist, and pulmonary radiologist. This multidisciplinary specialized ascertainment approach aimed to reduce outcome measurement error.

Our study had limitations. Information bias was likely present because of the retrospective study design and missing data. However, a retrospective design was required because of the rare occurrence of ANCA‐ILD. Because our center is a specialized tertiary vasculitis and ILD center, potential referral bias may limit the generalizability of our results to the general population with ILD.

In conclusion, AAV should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with ILD. We also advocate that ANCA testing should be included in the workup of ILD independently of clinical suspicion of AAV. Prospective, longitudinal studies are required to better understand the prognosis of patients with ANCA‐ILD and to determine optimal therapeutic strategies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr Shen had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design

Makhzoum.

Acquisition of data

Bui, Richard, Toban.

Analysis and interpretation of data

Shen, Lévesque, Meunier, Ross, Makhzoum.

Supporting information

Disclosure form

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Mrs. Guylaine Marcotte (research coordinator), Dr. Ariane Drouin (collaborator), and Dr. Alexandra Mereniuk (collaborator).

Author disclosures are available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr2.11679.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ryerson CJ, Collard HR. Update on the diagnosis and classification of ILD. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2013;19(5):453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;188(6):733–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cottin V, Hirani NA, Hotchkin DL, et al. Presentation, diagnosis and clinical course of the spectrum of progressive‐fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir Rev 2018;27(150):180076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Makhzoum JP, Grayson PC, Ponte C, et al. Pulmonary involvement in primary systemic vasculitides. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;61(1):319–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meyer KC. Diagnosis and management of interstitial lung disease. Transl Respir Med 2014;2:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jennette JC. Overview of the 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Clin Exp Nephrol 2013;17(5):603–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sacoto G, Boukhlal S, Specks U, et al. Lung involvement in ANCA‐associated vasculitis. Presse Med 2020;49(3):104039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Negreros M, Flores‐Suarez LF. A proposed role of neutrophil extracellular traps and their interplay with fibroblasts in ANCA‐associated vasculitis lung fibrosis. Autoimmun Rev 2021;20(4):102781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Katsumata Y, Kawaguchi Y, Yamanaka H. Interstitial lung disease with ANCA‐associated vasculitis. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med 2015;9(Suppl 1):51–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hozumi H, Oyama Y, Yasui H, et al. Clinical significance of myeloperoxidase‐anti‐neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. PLoS One 2018;13(6):e0199659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fischer A, Antoniou KM, Brown KK, et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society research statement: interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features. Eur Respir J 2015;46(4):976–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Raghu G, Remy‐Jardin M, Myers JL, et al; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society; Japanese Respiratory Society; Latin American Thoracic Society. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;198(5):e44–e68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jeganathan N, Sathananthan M. The prevalence and burden of interstitial lung diseases in the USA. ERJ Open Res 2022;8(1):00630–2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang H, Wang YX, Jiang CG, et al. A retrospective study of microscopic polyangiitis patients presenting with pulmonary fibrosis in China. BMC Pulm Med 2014;14:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sambataro D, Sambataro G, Pignataro F, et al. Patients with interstitial lung disease secondary to autoimmune diseases: how to recognize them? Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10(4):208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kadura S, Raghu G. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody‐associated interstitial lung disease: a review. Eur Respir Rev 2021;30(162):210123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arulkumaran N, Periselneris N, Gaskin G, et al. Interstitial lung disease and ANCA‐associated vasculitis: a retrospective observational cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50(11):2035–2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alba MA, Flores‐Suarez LF, Henderson AG, et al. Interstital lung disease in ANCA vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev 2017;16(7):722–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moiseev S, Cohen Tervaert JW, Arimura Y, et al. 2020 international consensus on ANCA testing beyond systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev 2020;19(9):102618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mahler DA, Wells CK. Evaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspnea. Chest 1988;93(3):580–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maillet T, Goletto T, Beltramo G, et al. Usual interstitial pneumonia in ANCA‐associated vasculitis: a poor prognostic factor. J Autoimmun 2020;106:102338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sun K, Fisher JH, Pagnoux C. Interstitial lung disease in ANCA‐associated vasculitis: pathogenic considerations and impact for patients' outcomes. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2022;24(8):259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guilpain P, Chereau C, Goulvestre C, et al. The oxidation induced by antimyeloperoxidase antibodies triggers fibrosis in microscopic polyangiitis. Eur Respir J 2011;37(6):1503–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schnabel A, Reuter M, Csernok E, et al. Subclinical alveolar bleeding in pulmonary vasculitides: correlation with indices of disease activity. Eur Respir J 1999;14(1):118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sun X, Peng M, Zhang T, et al. Clinical features and long‐term outcomes of interstitial lung disease with anti‐neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. BMC Pulm Med 2021;21(1):88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sreih AG, Cronin K, Shaw DG, et al. Diagnostic delays in vasculitis and factors associated with time to diagnosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2021;16(1):184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ando M, Miyazaki E, Ishii T, et al. Incidence of myeloperoxidase anti‐neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positivity and microscopic polyangitis in the course of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med 2013;107(4):608–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hosoda C, Baba T, Hagiwara E, et al. Clinical features of usual interstitial pneumonia with anti‐neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody in comparison with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2016;21(5):920–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nozu T, Kondo M, Suzuki K, et al. A comparison of the clinical features of ANCA‐positive and ANCA‐negative idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. Respiration 2009;77(4):407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Savige JA, Chang L, Wilson D, et al. Autoantibodies and target antigens in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)‐associated vasculitides. Rheumatol Int 1996;16(3):109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhao X, Wen Q, Qiu Y, et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of ANA/anti‐dsDNA positive patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody‐associated vasculitis. Rheumatol Int 2021;41(2):455–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Disclosure form