Abstract

Background

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have become the preferred drugs for the treatment of chronic phase (CP) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). This study aims to compare the safety and efficacy of different TKIs as first-line treatments for CML using network meta-analysis (NMA), providing a basis for the precise clinical use of TKIs.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted on PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, China National knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang, Chinese Science and Technology Periodical Databases (VIP), SinoMed and ClinicalTrials.gov to include RCTs that compared the different TKIs as first line treatment for CML. The search timeline was from inception to 21 July 2023. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and the frequentist NMA methods, the efficacy and safety of different TKIs were compared, including the rates of major molecular response (MMR), complete cytogenetic response (CCyR), all grade adverse events, grade 3 or higher hematologic adverse events and liver toxicity.

Results

A total of 25 RCTs involving 6,823 patients with CML and 6 types of TKIs were included. In terms of efficacy, second-generation TKIs such as dasatinib, nilotinib, and radotinib showed certain advantages in improving patients’ MMR and CCyR compared to imatinib. Additionally, imatinib 800 mg provided better MMRs and CCyRs than imatinib 400 mg. As far as safety was concerned, there was no significant difference in the incidence of all grade adverse events among the different TKIs. All TKIs can cause serious grade 3–4 hematologic adverse events, including anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia. Dasatinib more likely caused anemia, bosutinib thrombocytopenia, and imatinib neutropenia, whereas nilotinib and flumatinib might have better safety profiles in terms of severe hematologic adverse events. For liver toxicity, radotinib 400 mg and imatinib 800 mg, respectively, had the highest likelihood of ranking first in incidence rates of all grade ALT and AST elevation.

Conclusions

In CML, second-generation TKIs are more clinically effective than imatinib even if this last drug has a relatively better safety profile. Thus, as each second-generation TKI has a distinct clinical efficacy and safety, and is associated with different economic factors, its choice should be dictated by the specific patient clinical conditions (patient’s specific disease characteristics, comorbid conditions, potential drug interactions, as well as their adherence). Nevertheless, due to the limited number of original research, additional high-quality studies are needed to achieve any firm conclusion on which second-generation TKI is the best choice for that peculiar patient.

Keywords: Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), network meta-analysis (NMA)

Highlight box.

Key findings

• In patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), current evidence suggests that second-generation Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are more clinically effective than first-generation imatinib despite the fact that this drug has relatively better safety profile.

• Among second-generation TKIs, the surface under the cumulative ranking (SUCRA) value suggested that the nilotinib 300 mg is the most likely to result in the highest for major molecular response (MMR) and complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) at 12 months.

• Different TKIs have different advantages with distinct types and rates of adverse reactions.

What is known and what is new?

• Currently most randomized control trials (RCTs) with second-generation TKIs use imatinib as a term of comparison instead of direct comparisons between second-generation TKIs.

• In this study, network meta-analysis (NMA) was used to indirectly compare the efficacy and safety of different TKIs.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• The findings advocated for a more tailored approach to selecting first-line TKI therapy for CML, moving beyond the conventional comparison against imatinib alone. Clinicians should consider the specific efficacy and safety profiles of second-generation TKIs as revealed by this analysis to optimize patient outcomes.

• Given the nuanced differences among second-generation TKIs, decision-making should incorporate patient-specific considerations, including potential for adverse reactions, underlying health conditions, and treatment goals.

• Further direct comparative research is needed to validate these findings and refine treatment guidelines, ensuring that CML management is informed by the most current and comprehensive evidence.

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a malignant hematopoietic stem cell disorder predominantly characterized by a myeloid proliferation, marked by the presence of the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph) and/or the BCR-ABL fusion gene (1). Accounting for 15–20% of all adult leukemia cases, CML has a global annual incidence rate of 1–2 per 100,000 individuals (2). The diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for CML outline clear criteria for its diagnosis, clinical features, and natural progression (3). Typically, the disease progresses through 3 stages: the chronic phase (CP), the accelerated phase (AP), and the blast phase (BP). Over 80% of patients are diagnosed during the CP without any symptoms. Due to its prolonged asymptomatic phase, CML is most commonly diagnosed during CP rather than AP (4). The introduction of the first-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), imatinib, revolutionized the life expectancy of patients with CML (5,6). Imatinib was approved in 2001 in Europe and the United States for all stages of CML, significantly extending patient survival (7). However, some patients with CML had to discontinue imatinib or switch to other therapies due to disease progression, resistance, or adverse events, as indicated by a phase III clinical trial (IRIS). These events underscored the need for new TKIs in CML treatment.

Second-generation TKIs, dasatinib and nilotinib, were approved in 2006 and 2007 in the US and Europe, respectively, for patients with CML resistant or intolerant to imatinib (8). Dasatinib was approved for all CML stages, whereas nilotinib was approved for CP patients (9,10). With time and technological advancements, both drugs were approved as first-line treatments for newly diagnosed Ph-positive (Ph+) adult CML in 2010 and 2011 (9). Another second-generation TKI, bosutinib, was authorized in 2012 and 2013 in the US and Europe for patients with CP, AP, or BP CML resistant or intolerant to 1 or more TKIs. In December 2017, bosutinib indication in the US expanded to include first-line treatment for newly diagnosed adult Ph+ CP-CML (10). Flumatinib, a novel oral BCR-ABL1 TKI, demonstrated better efficacy than imatinib in treating newly diagnosed CP-CML, characterized by faster and higher response rates, translating to better survival outcomes (11). Additionally, a phase II trial indicated that radotinib is effective and well-tolerated in patients with CP-CML unresponsive to previous TKI treatments, with a dose-dependent trend (12). Based on this study, radotinib was initially approved in South Korea for patients with CML unresponsive to prior TKI therapy and was approved as a first-line treatment in 2015 (13).

Most randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of second-generation TKIs currently use imatinib as a comparator, lacking direct comparisons between second-generation TKIs. Therefore, using network meta-analysis (NMA) enables indirect comparison of the efficacy and safety of different TKIs. Although previous NMA have been conducted, none have included studies on flumatinib. Hence, this study aimed to provide a comprehensive comparison of the efficacy and safety of various TKIs in treating patients with CML worldwide, offering clinical guidance for medication selection. We present this article in accordance with the PRISMA-NMA reporting checklist (available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-24-747/rc).

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

The present analysis includes adult CML patients with ≥18 years of age (CML diagnosis was confirmed by typical clinical presentations and the presence of the Ph+ and/or BCR-ABL fusion gene in cytogenetic or molecular biology tests) enrolled in RCT or cohort studies who received first-line treatments with imatinib, nilotinib, dasatinib, radotinib, bosutinib, and flumatinib at standard clinical dosages for CP, AP and BP; single cohort studies or studies comparing 2nd TKIs versus imatinib; studies describing the incidence of all grade adverse events and grade 3 or above hematologic adverse events (anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia); studies describing the incidence of extra-hematologic adverse events; studies describing the incidence of major molecular response (MMR) at 3, 6, 12 months, complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) rate at 6, 12 months, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS); studies from which relevant data can be extracted (i.e., time of TKI treatment); English or Chinese publications.

Exclusion criteria

Studies published twice.

Literature search

Systematic searches were conducted in PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang, Chinese Science and Technology Periodical Databases (VIP), SinoMed, and ClinicalTrials.gov from inception to 21 July 2023. By using Medical Subjects Headings (MeSH), a combination of subject terms and free words was used, adjusted for each specific database. Search terms included “imatinib”, “dasatinib”, “nilotinib”, “flumatinib”, “bosutinib”, “radotinib”, and “chronic myelocytic leukemia”. The specific search strategy is detailed in Appendix 1. Additionally, references from the included literature and related meta-analyses were tracked.

Literature screening, data extraction, and assessment of literature bias

Two researchers independently screened the literature, extracted data, and assessed bias risks according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third researcher. After reading titles and abstracts for initial screening, full texts were reviewed in detail, and studies meeting the inclusion criteria were finally included. Data extraction mainly included basic study information (author, year of publication, country, etc.), baseline characteristics of participants (age, sample size), interventions and control measures, outcome measures and effect values, and key elements for bias risk evaluation. The bias risk of included RCTs was evaluated using the tool recommended by the Cochrane Handbook (14).

Statistical analysis

Pairwise meta-analyses were first performed for 2 interventions with head-to-head comparisons using RevMan 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). For dichotomous variables, risk ratios (RR) were used as effect measures, and for continuous variables, mean differences (MD) were used. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of each effect size were calculated. Results were considered statistically significant if the RR value’s 95% confidence interval did not include 1.0. Heterogeneity was measured using I2; if present (I2>50%, P<0.05), a random-effects model was used, otherwise a fixed-effects model was employed.

For NMA, a frequentist framework model was used to calculate the RR values and 95% CI between different interventions. Stata 15 software’s (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) network meta command was employed for NMA, and a network evidence plot was created. Inconsistency was tested using loop inconsistency and node-splitting methods; a consistency model was used when P>0.05. The surface under the cumulative ranking (SUCRA) curve was used to evaluate the relative ranking of each intervention across outcomes. SUCRA reflects the probability of an intervention being the best option for efficacy; the higher the value, the more likely it is to be the best intervention. Funnel plots were created for outcome measures included in 10 or more studies to analyze publication bias.

Results

Literature screening process and outcomes

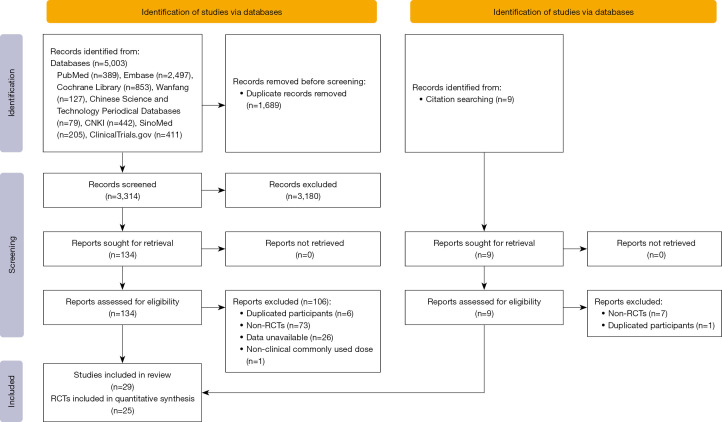

A total of 5,003 articles were initially identified through our search. Following a rigorous screening process based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, which involved reviewing titles, abstracts, and full texts, 29 articles were ultimately included. These comprised 25 RCTs encompassing 6,823 patients. The literature screening process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flowchart. RCTs, randomized controlled trials.

Characteristics of the studies included

The basic characteristics of the included articles are summarized in Table 1. The 29 articles were published over a period spanning from 2009 to 2022, involving 6 types of TKIs. These included imatinib in 23 studies, dasatinib in 11, nilotinib in 5, bosutinib in 2, flumatinib in 2 studies, and radotinib in 1 study. The interventions were further classified based on drug dosage, encompassing a total of 14 treatment strategies.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies.

| Author, year | Country | Intervention | Sample size | Gender (male/female) | Age (years) | Outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 1 | Group 2 | ||||||

| Han, 2022 (15) | China | NIL 300 mg BID | IM 400 mg QD | 34 | 34 | 20/14 | 19/15 | 20–55a | 18–66a | ① ② ③ ④ ⑤ | |||

| Brümmendorf, 2022 (16); Cortes, 2018 (17) | Global, multicenter | BOS 400 mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 268 | 268 | 156/112 | 155/113 | 52 [18–84]b | 53 [19–84]b | ① ② ③ ⑤ ⑦ (5 years) ⑧ ⑨ ⑩ ⑪ ⑫ ⑬ | |||

| NCT00481247 (18); Jabbour, 2014 (19); Kantarjian, 2012 (20); Kantarjian, 2010 (21) | Global, multicenter | DAS 100 mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 259 | 260 | 141/115 | 163/97 | 46 [18–84]b | 49 [18–78]b | ③ ⑤ ⑥ (2, 3, 5 years) ⑦ (2, 3, 5 years) ⑨ ⑩ ⑪ | |||

| Li, 2021 (22) | China | NIL 300–400 mg BID | IM 400 mg QD | 39 | 39 | 22/17 | 23/16 | 48.25±6.71c | 47.03±6.42c | ⑤ ⑥ (3 years) ⑦ (3 years) | |||

| Yu, 2021 (23) | China | DAS 70 mg QD | DAS 100 mg QD | 29 | 22 | 13/16 | 15/7 | 47.13±15.15c | 43.59±14.36c | ② ③ ④ ⑤ ⑫ | |||

| Wang, 2020 (24) | China | NIL 400 mg BID | DAS 100 mg QD | 12 | 13 | 7/5 | 7/6 | 35–65a | 35–65a | ③ ⑤ ⑧ | |||

| Cortes, 2020 (25) | Global, multicenter | IM ≥400 mg OD or BID | DAS 100mg QD | 86 | 174 | 70/16 | 133/41 | 40 [18–73]b | 35 [18–82]b | ③ ⑥ (2 years) ⑦ (2 years) ⑧ ⑨ ⑩ ⑪ | |||

| Zhang, 2021 (11) | China | FLU 600 mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 196 | 197 | 126/70 | 119/78 | 45 [20–70]b | 45 [18–73]b | ② ③ ④ ⑤ ⑨ ⑩ ⑪ ⑫ ⑬ | |||

| Geng, 2018 (26) | China | DAS 100 mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 44 | 43 | 28/16 | 26/17 | 42.8±6.5c | 43.1±6.8c | ⑤ ⑧ ⑫ | |||

| Wang, 2017 (27) | China | DAS 100 mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 10 | 10 | 7/3 | 6/4 | 40.25±10.13c | 41.15±10.21c | ⑤ ⑧ ⑫ | |||

| Kwak, 2017 (28) | Global, multicenter | IM 400 mg QD; RAD 400 mg BID | RAD 300 mg BID | 81; 81 | 79 | 50/31; 47/34 | 52/27 | 45 [18–83]b; 43 [18–84]b | 45 [20–75]b | ① ② ③ ④ ⑤ ⑨ ⑩ ⑪ ⑫ ⑬ | |||

| Hehlmann, 2017 (29) | Germany, Switzerland | IM 800 mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 420 | 400 | 248/172 | 244/156 | 51 [18–85]b | 53 [16–88]b | ③ | |||

| Lu, 2016 (30) | China | DAS 100 mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 20 | 20 | 11/9 | 10/10 | 20–61a | 20–60a | ⑤ ⑧ ⑫ | |||

| Liu, 2016 (31) | China | FLU 400 mg QD; FLU 600 mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 8; 9 | 7 | 15/9 | 38d | ③ | |||||

| Wang, 2016 (32) | China | NIL 300 mg BID; DAS 100 mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 32; 32 | 32 | 17/15; 18/14 | 16/16 | 41.53±3.81c; 40.14±4.23c | 39.81±3.25c | ① ② ③ ④ ⑤ ⑧ | |||

| Hjorth-Hansen, 2015 (33) | Finland, Norway, Sweden | DAS 100 mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 22 | 24 | 7/15 | 15/9 | 53 [29–71]b | 58 [38–78]b | ④ ⑤ ⑨ ⑩ ⑪ | |||

| Zheng, 2013 (34) | China | DAS 100mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 13 | 12 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ⑤ | |||

| Radich, 2012 (35) | United States, Canada | IM 400 mg QD | DAS 100 mg QD | 123 | 123 | 72/51 | 74/49 | 50 [19–89]b | 47 [18–90]b | ⑤ ⑪ | |||

| Cortes, 2012 (36) | Global, multicenter | BOS 500 mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 250 | 252 | 149/101 | 135/117 | 48 [19–91]b | 47 [18–89]b | ⑨ ⑩ ⑪ ⑫ ⑬ | |||

| Hehlmann, 2011 (37) | Global, multicenter | IM 800 mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 338 | 325 | 199/139 | 195/130 | 52 [18–86]b | 54 [16–88]b | ② ③ ④ ⑤ ⑨ ⑩ ⑪ | |||

| Saglio, 2010 (38) | Global, multicenter | IM 400 mg QD; NIL 400 mg BID | NIL 300 mg BID | 283; 281 | 282 | 158/125; 175/106 | 158/124 | 46 [18–80]b; 47 [18–81]b | 47 [18–85]b | ① ② ③ ④ ⑤ ⑧ ⑫ ⑬ | |||

| Preudhomme, 2010 (39) | France | IM 400 mg QD | IM 600 mg QD | 159 | 160 | 109/50 | 89/71 | 50d | 51d | ③ ④ ⑤ | |||

| Petzer, 2010 (40) | Austria | IM 800 mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 113 | 113 | 53/58 | 48/63 | 46.5±12.3c | 45.5±13.4c | ④ | |||

| Cortes, 2010 (41) | Global, multicenter | IM 800 mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 319 | 157 | 183/136 | 84/73 | 48 [18–75]b | 45 [18–75]b | ① ② ③ ④ ⑤ | |||

| Baccarani, 2009 (42) | Italy | IM 800 mg QD | IM 400 mg QD | 108 | 108 | 60/48 | 62/46 | 51 [18–84]b | 56 [18–81]b | ① ② ③ ④ ⑤ | |||

a, minimum-maximum; b, median [Q1–Q3]; c, mean ± SD; d, mean. ① MMR rate at 3 months; ② MMR rate at 6 months; ③ MMR rate at 12 months; ④ CCyR rate at 6 months; ⑤ CCyR rate at 12 months; ⑥ PFS rate; ⑦ OS rate; ⑧ overall incidence of adverse events; ⑨ incidence of grade 3 or above anemia; ⑩ incidence of grade 3 or above thrombocytopenia; ⑪ incidence of grade 3 or above neutropenia; ⑫ incidence of ALT elevation of all grade; ⑬ incidence of AST elevation of all grade. IM, imatinib; QD, quaque die; BID, bid twice a day; DAS, dasatinib; NIL, nilotinib; BOS, bosutinib; FLU, flumatinib; RAD, radotinib; MMR, major molecular response; CCyR, complete cytogenic response; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

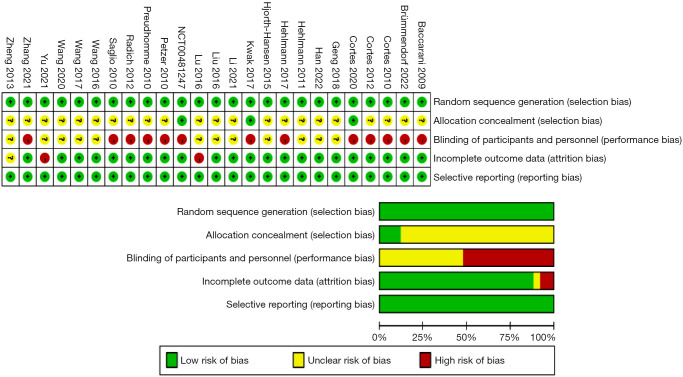

Risk of bias: assessment results

We employed the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for assessing the 25 included RCTs (Figure 2). Among these studies, 3 reported concealments of the randomization sequence. A total of 13 studies were conducted in an open-label manner, meaning that blinding was not implemented for the participants; 3 studies demonstrated a risk of incomplete outcome data, and the remaining studies did not report relevant information.

Figure 2.

Bias assessment of the RCTs included for analysis. RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Results of the direct comparison meta-analysis

Our meta-analysis of head-to-head comparative studies, detailed in the forest plots of pairwise meta-analysis (Figure S1), revealed significant findings. Compared to imatinib 400 mg, nilotinib 300 mg showed superior efficacy in terms of MMR at 3 months (RR =5.58, 95% CI: 2.55–12.24), MMR at 6 months (RR =2.63, 95% CI: 1.93–3.58), MMR at 12 months (RR =1.98, 95% CI: 1.64–2.38), CCyR at 6 months (RR =1.38, 95% CI: 1.14–1.68), and CCyR at 12 months (RR =1.23, 95% CI: 1.13–1.35), with all differences being statistically significant. In comparison with imatinib 400 mg, imatinib 800 mg was more effective in achieving MMR at 3 months (RR =2.45, 95% CI: 1.04–5.79), MMR at 6 months (RR =1.74, 95% CI: 1.28–2.37), MMR at 12 months (RR =1.42, 95% CI: 1.17–1.73), CCyR at 6 months (RR =1.34, 95% CI: 1.10–1.62), and CCyR at 12 months (RR =1.15, 95% CI: 1.02–1.29), with all these differences being statistically significant. Dasatinib 100 mg outperformed imatinib 400 mg in MMR at 12 months (RR =1.78, 95% CI: 1.44–2.20) and CCyR at 12 months (RR =1.28, 95% CI: 1.11–1.47), with these differences also being statistically significant.

Regarding safety, compared to imatinib 400 mg, imatinib 800 mg had a higher risk of grade 3–4 thrombocytopenia (RR =1.76, 95% CI: 1.10–2.81) and neutropenia (RR =1.53, 95% CI: 1.06–2.20). Dasatinib 100 mg also showed a significantly higher rate of grade 3–4 thrombocytopenia compared to imatinib 400 mg (RR =1.65, 95% CI: 1.14–2.39). Compared to dasatinib 100 mg, imatinib 400 mg exhibited a greater risk of all-grade ALT elevation (RR =6.33, 95% CI: 1.17–34.20) and all-grade AST elevation (RR =5.49, 95% CI: 3.82–7.89). Furthermore, imatinib’s risk of all-grade AST elevation was also higher than that associated with bosutinib 400 mg (RR =3.67, 95% CI: 2.58–5.23).

NMA

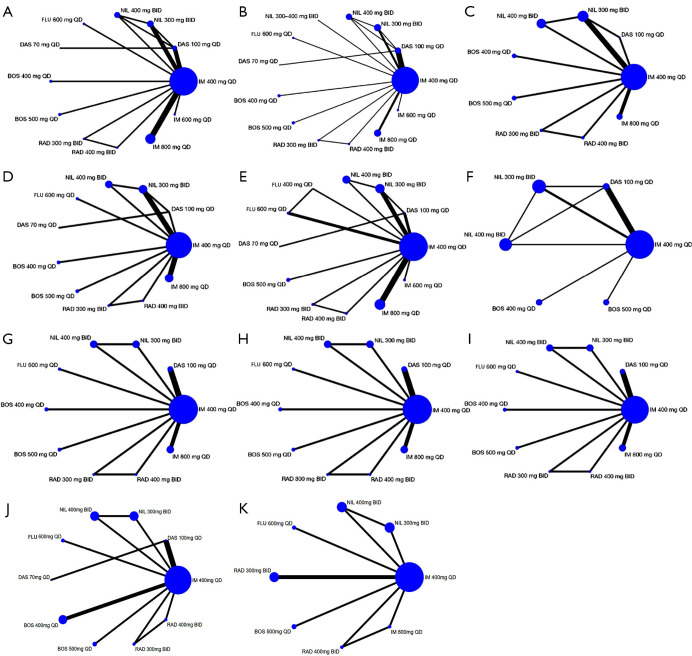

Network evidence map

The network relationship diagram among various intervention measures is shown in Figure 3. The size of the nodes represents the sample size of the corresponding intervention measures, and the width of the lines indicates the number of studies between 2 interventions. Network diagrams were drawn for each outcome indicator, with a total of 11 outcome indicators of interest in this study. As can be seen, imatinib 400 mg had the largest sample size.

Figure 3.

Network graphs of eligible trials assessing tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia for nine outcomes. (A) MMR 3; (B) MMR 6; (C) MMR 12; (D) CCyR 6; (E) CCyR 12; (F) all grades adverse events; (G) anemia of grade 3 or 4; (H) thrombocytopenia of grade 3 or 4; (I) neutropenia of grade 3 or 4; (J) ALT elevation of all grades; (K) AST elevation of all grades. MMR, major molecular response; CCyR, complete cytogenic response; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; IM, imatinib; DAS, dasatinib; NIL, nilotinib; BOS, bosutinib; RAD, radotinib; FLU, flumatinib; QD, quaque die; BID, bis in die.

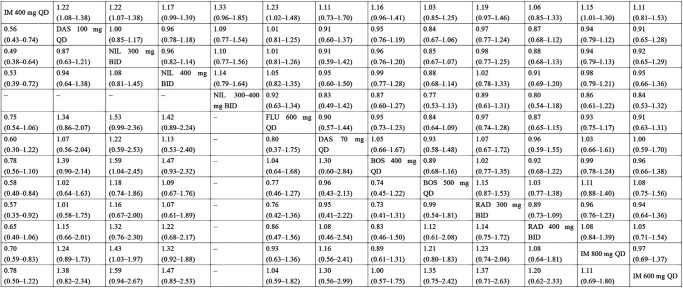

Results of NMA

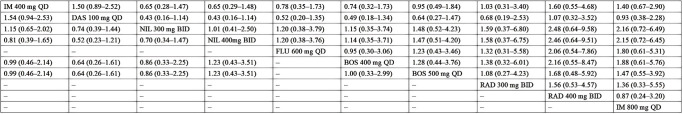

The results revealed that compared to imatinib 400 mg, dasatinib 100 mg, nilotinib 300 mg, and imatinib 800 mg groups had significantly higher MMR rates at 3 months. There were 9 intervention measures (dasatinib 100 mg, nilotinib 300 mg, nilotinib 400 mg, flumatinib 600 mg, dasatinib 70 mg, bosutinib 400 mg, bosutinib 500 mg, radotinib 300 mg, and imatinib 800 mg) that showed significantly higher MMR rates at 6 months compared to imatinib 400 mg; dasatinib 100 mg demonstrated significantly better efficacy than imatinib 800 mg in MMR at 6 months. There were 6 intervention measures (dasatinib 100 mg, nilotinib 300 mg, nilotinib 400 mg, bosutinib 500 mg, radotinib 300 mg, and imatinib 800 mg) that had significantly higher MMR rates at 12 months compared to imatinib 400 mg; nilotinib 300 mg had a significantly higher MMR rate at 12 months compared to bosutinib 400 mg and imatinib 800 mg. For CCyR, 3 interventions (nilotinib 300 mg, flumatinib 600 mg, and imatinib 800 mg) showed significantly higher rates than imatinib 400 mg at 6 months. Compared to imatinib 400 mg, 4 interventions (dasatinib 100 mg, nilotinib 300 mg, flumatinib 600 mg, and imatinib 800 mg) had significantly higher CCyR rates at 12 months. The results of MMR and CCyR at 12 months are shown in Figure 4, and the remaining effectiveness results are shown in Table S1 and Figure S2.

Figure 4.

Pooled estimates of the network meta-analysis for MMR 12 and CCyR 12. Pooled risk ratio (95% confidence intervals) for CCyR 12 (upper triangle) and MMR 12 (lower triangle). MMR, major molecular response; CCyR, complete cytogenic response; IM, imatinib; DAS, dasatinib; NIL, nilotinib; BOS, bosutinib; RAD, radotinib; FLU, flumatinib; QD, quaque die; BID, bis in die.

Regarding the endpoint outcomes of PFS and OS, only 5 studies reported PFS rates at 2, 3, and 5 years, and 6 studies reported OS rates at 2, 3, and 5 years (Table 2). Due to the limited number of studies, no network could be formed, thus only descriptive analyses were conducted. The included studies showed no significant differences in 2-, 3-, and 5-year PFS and OS rates between dasatinib 100 mg and imatinib 400 mg; there was no significant difference in 3-year PFS and OS rates between nilotinib 300–400 mg and imatinib 400 mg; and there was no significant difference in 5-year OS rates between bosutinib 400 mg and imatinib 400 mg.

Table 2. Summary of PFS and OS rate.

| Author, year | Outcomes | Intervention 1 | Intervention 2 | RR (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regimen | Rate, % | Total patients | Regimen | Rate, % | Total patients | ||||

| NCT00481247 (18) | 5-year PFS rate | DAS 100 mg | 88.80 | 259 | IM 400 mg | 89.23 | 260 | 1.00 (0.94–1.06) | |

| Li, 2021 (22) | 3-year PFS rate | NIL 300–400 mg | 87.18 | 39 | IM 400 mg | 66.64 | 39 | 1.31 (1.02–1.68) | |

| Jabbour, 2014 (19) | 3-year PFS rate | DAS 100 mg | 91.11 | 259 | IM 400 mg | 90.77 | 260 | 1.00 (0.95–1.06) | |

| Kantarjian, 2012 (20) | 2-year PFS rate | DAS 100 mg | 93.82 | 259 | IM 400 mg | 91.92 | 260 | 1.02 (0.98–1.05)a | |

| Cortes, 2020 (25) | 2-year PFS rate | DAS 100 mg | 95.98 | 174 | IM 400 mg | 95.35 | 86 | ||

| Brümmendorf, 2022 (16) | 5-year OS rate | BOS 400 mg | 94.31 | 246 | IM 400 mg | 94.61 | 241 | 1.00 (0.95–1.04) | |

| NCT00481247 (18) | 5-year OS rate | DAS 100 mg | 90.73 | 259 | IM 400 mg | 89.61 | 260 | 1.01 (0.96–1.07) | |

| Li, 2021 (22) | 3-year OS rate | NIL 300–400 mg | 92.31 | 39 | IM 400 mg | 79.49 | 39 | 1.16 (0.97–1.40) | |

| Jabbour, 2014 (19) | 3-year OS rate | DAS 100 mg | 93.82 | 259 | IM 400 mg | 93.08 | 260 | 1.01 (0.96–1.05) | |

| Kantarjian, 2012 (20) | 2-year OS rate | DAS 100 mg | 95.37 | 259 | IM 400 mg | 95.38 | 260 | 1.00 (0.97–1.03)a | |

| Cortes, 2020 (25) | 2-year OS rate | DAS 100 mg | 97.70 | 174 | IM 400 mg | 96.51 | 86 | ||

a, RR reflects the pooled effect size through the meta-analysis. PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; RR, risk ratios; IM, imatinib; DAS, dasatinib; NIL, nilotinib; BOS, bosutinib.

For safety outcome indicators, we evaluated hematologic adverse reactions (anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia) associated with TKIs, which are of clinical concern. There were no statistically significant differences in overall incidence of adverse events and incidence of grade 3–4 anemia events among various intervention measures. Considering the incidence of grade 3–4 thrombocytopenia, it was significantly lower with imatinib 400 mg than with dasatinib 100 mg, bosutinib 400 mg, and imatinib 800 mg. In addition, the incidence of grade 3–4 thrombocytopenia with dasatinib 100 mg was significantly higher than with radotinib 400 mg, significantly lower with flumatinib 600 mg than with bosutinib 400 mg. Moreover, the incidence of grade 3–4 thrombocytopenia was significantly lower with radotinib 400 mg than with imatinib 800 mg. The rate of grade 3–4 neutropenia was significantly higher with imatinib 400 mg than with nilotinib 300 mg, nilotinib 400 mg, bosutinib 500 mg, and bosutinib 400 mg and significantly higher with imatinib 800 mg than with other intervention measures. The analysis of all grade adverse events including grade 3–4 anemia is shown in Figure 5, and other safety results are shown in Table S1 and Figure S2.

Figure 5.

Pooled estimates of the network meta-analysis for all grades adverse events and anemia of grades 3 or 4. Pooled risk ratio (95% confidence intervals) for anemia of grade 3 or 4 (upper triangle) and all grades adverse events (lower triangle). IM, imatinib; DAS, dasatinib; NIL, nilotinib; BOS, bosutinib; RAD, radotinib; FLU, flumatinib; QD, quaque die; BID, bis in die.

In our examination of extra-hematological toxicities, we specifically assessed liver toxicity as indicated by alterations in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels associated with various TKIs. The incidence of all-grade ALT elevation revealed a notable variance among the different TKIs. Imatinib 400 mg demonstrated a significantly lower incidence of ALT elevation when compared to the other TKIs, except for dasatinib, which also exhibited a reduced incidence of ALT elevation relative to its counterparts. Noteworthy is the observation that radotinib 400 mg was associated with a significantly higher incidence of ALT elevation in comparison to bosutinib 500 mg, flumatinib 600 mg, dasatinib 100 mg, and imatinib 400 mg. Similarly, with respect to AST levels, radotinib 400 mg demonstrated a significantly higher incidence of elevation than imatinib 400 mg, nilotinib, and flumatinib. Imatinib 800 mg had a significantly higher incidence of AST elevation when compared to the other TKIs, except for radotinib 400 mg.

Intervention measure rankings

The cumulative probability ranking diagrams for different outcome indicators are presented in Table S1. The results indicated that for MMR at 3 months, radotinib 400 mg had the highest SUCRA value. For MMR at 6 months, dasatinib 100 mg and dasatinib 70 mg demonstrated the highest SUCRA values, whereas for MMR at 12 months, this datum occurred for nilotinib 300 mg. As far as CCyR at 6 months, flumatinib 600 mg ranked first whereas for CCyR at 12 months, nilotinib 300–400 mg showed the highest SUCRA values, revealing the highest probability of being the most effective drug. Regarding the overall incidence of adverse events, dasatinib 100 mg had the smallest SUCRA value, suggesting that it is the safest option. For grade 3–4 anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia, dasatinib 100 mg, bosutinib 400 mg, and imatinib 800 mg, respectively, had the highest likelihood of ranking first in incidence rates. For all grade ALT and AST elevation, radotinib 400 mg and imatinib 800 mg, respectively, had the highest likelihood of ranking first in incidence rates.

Inconsistency test

The node-splitting method and loop inconsistency tests were applied, and no inconsistencies were found. The results of the inconsistency tests are available in Figure S3.

Publication bias

Funnel plots for MMR at 6 months, MMR at 12 months, CCyR at 6 months, CCyR at 12 months and all grade ALT evaluation displayed symmetrical patterns, suggesting no significant publication bias.

Discussion

Since 2000, the advent of the first-generation TKI imatinib heralded the era of targeted therapy in CML (43). Imatinib, by specifically inhibiting the activity of the BCR-ABL kinase, has dramatically improved the survival of patients with CML, allowing 80–90% of them to achieve life expectancies comparable to those of the general population and enhancing their quality of life (44,45). As a first-line treatment, long-term studies have shown that imatinib warrants a 10-year survival rate of 80–90% (46). Subsequently, second-generation TKIs (such as nilotinib, dasatinib, bosutinib, flumatinib, and radotinib) and third-generation TKIs (such as ponatinib) emerged and revealed their ability of accelerating and deepening treatment responses (47-49). These developments effectively overcame most cases of imatinib resistance and offered additional treatment options in patients intolerant to imatinib, transforming the once fatal CML in a manageable chronic condition.

Nowadays, given the plethora of TKI options, to assess which is the best first-line treatment strategy for patients with newly diagnosed Ph+ CP-CML has become a critically important task. A study indicated that bosutinib and imatinib exhibit similar safety profiles in patients with newly diagnosed CP-CML. However, liver function abnormalities have been identified as a common reason for discontinuing/stopping bosutinib treatment (16 considering that the efficacy of bosutinib is comparable to that of nilotinib and dasatinib, nilotinib has been widely used in newly diagnosed Ph+ CP-CML patients as well as in CP- or AP-CML patients who are either resistant or intolerant to imatinib (50), but nilotinib too may cause liver toxicity. This adverse event has also been observed with radotinib, a second-generation TKI which allows to achieve higher CCyR and faster MMR rates. Although direct comparative studies between radotinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib are lacking, research studies indicate that radotinib efficacy is comparable to those of nilotinib and dasatinib (51), while it induces a lower incidence of hematologic side effects than other second-generation BCR-ABL1 TKIs, but a higher incidence of hyperbilirubinemia (52).

In our study, 25 RCTs meeting the criteria for a meta-analysis were included, with one study comparing the efficacy and safety of flumatinib (600 mg/d) with imatinib in the treatment of newly diagnosed CML. This study demonstrated that flumatinib is a safe and effective medication for treating newly diagnosed Ph+ CP-CML patients, with 600 mg/d being an appropriate clinical starting dose. Compared to imatinib, flumatinib showed similar safety in clinical settings (11,53). Moreover, a real-world study also indicated a superior efficacy of flumatinib over imatinib in treating newly diagnosed CP-CML (54). Over a 12-month follow-up, patients treated with flumatinib experienced lower adverse event rates, including edema, limb pain, rash, neutropenia, anemia, and hypophosphatemia. Most adverse events associated with flumatinib were manageable through dose reduction or supportive care (55). Additionally, no Fredericia-corrected QT (QTcF) prolongation was observed in patients not treated with flumatinib. Thus, these data suggest that flumatinib, due to its efficacy and tolerability, may be an alternative therapeutic option in CP-CML patients (11,53). Given that flumatinib is not widely available internationally and the existing literature predominantly includes data from a few Asian countries, the applicability of our findings is limited.

Furthermore, our study found that severe hematologic adverse events, including thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and anemia, are common in TKI treatment. Imatinib 400 mg showed better safety in terms of thrombocytopenia, but its impact on neutropenia warrants further attention. Bosutinib 400 mg may be more prone to cause thrombocytopenia, whereas dasatinib 100 mg and imatinib 800 mg may increase the risk of neutropenia. Nilotinib and flumatinib appeared to have better safety profiles in severe hematologic adverse events.

Overall, our NMA indicated that second-generation TKIs perform better in patients with CML, with imatinib 400 mg being inferior in improving MMR and CCyR than other interventions. Dasatinib 100 mg, nilotinib 300 mg, and radotinib 300 mg may have a role in enhancing MMR and CCyR, whereas flumatinib 600 mg may have certain advantages in improving CCyR.

Considering the efficacy and safety of TKIs, our study suggests that nilotinib 300 mg may present certain advantages. However, the study is limited by the quality of original research, which bears risks in the implementation of random sequence generation and blinding (11,16-18,25,28,29,35-36,38-42). Additionally, the study is constrained by the data reported in the literature, with only a few studies providing PFS and OS data results. This study could not comprehensively analyze the final outcomes, only comparing the effect sizes between 2 interventions. Future research requiring more data is needed to further study the safety and efficacy of different doses of TKI drugs.

Conclusions

This study indicates that second-generation TKIs have certain advantages over first-generation imatinib in treating patients with CML. However, imatinib demonstrates relatively better safety, and different TKIs have different types and rates of adverse reactions and different advantages. Thus, the clinical choice of TKIs should consider efficacy, safety and cost and be based on the patient’s specific clinical conditions. Nonetheless, more high-quality research is needed to validate these findings due to the limited number and quality of original studies.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by Talent Project established by the Chinese Pharmaceutical Association Hospital Pharmacy Department (No. CPA-Z05-ZC-2022-003) and the Drug Clinical Comprehensive Evaluation Project of Jiangsu Provincial Health Commission and Bethune Quest- Pharmaceutical Research Capacity Building Project (No. Z04JKM2021005).

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA-NMA reporting checklist. Available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-24-747/rc

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-24-747/coif). Y.J.G., C.S., K.L.F., and T.L.M. are from Beijing Sentum Health Co., Ltd.; G.G. reports that he serves on the advisory board of SeaGen and Opna Bio. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Ciani O, Grigore B, Taylor RS. Development of a framework and decision tool for the evaluation of health technologies based on surrogate endpoint evidence. Health Econ 2022;31 Suppl 1:44-72. 10.1002/hec.4524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chinese Society of Hematology, Chinese Medical Association . The guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia in China (2020 edition). Chinese Journal of Hematology 2020;41:353-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poort H, Meade CD, Knoop H, et al. Adapting an Evidence-Based Intervention to Address Targeted Therapy-Related Fatigue in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients. Cancer Nurs 2018;41:E28-37. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hehlmann R. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in 2020. Hemasphere 2020;4:e468. 10.1097/HS9.0000000000000468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciftciler R, Haznedaroglu IC. Tailored tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) based on current evidence. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2021;25:7787-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z, Ge X. Clinical Clinical characteristics and treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. China Medicine 2020;15:280-3. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haznedaroğlu İC, Kuzu I, İlhan O. WHO 2016 Definition of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia and Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Turk J Haematol 2020;37:42-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massimino M, Stella S, Tirrò E, et al. ABL1-Directed Inhibitors for CML: Efficacy, Resistance and Future Perspectives. Anticancer Res 2020;40:2457-65. 10.21873/anticanres.14215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rousselot P, Coudé MM, Gokbuget N, et al. Dasatinib and low-intensity chemotherapy in elderly patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL. Blood 2016;128:774-82. 10.1182/blood-2016-02-700153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qian X, Wang J, Cai M, et al. Estradiol Valerate Enhances Cardiac Function via the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway to Protect Against Oxidative Stress by the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in an Ovariectomized Rat Model. Curr Pharm Des 2021;27:4716-25. 10.2174/1381612827666210927162612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Meng L, Liu B, et al. Flumatinib versus Imatinib for Newly Diagnosed Chronic Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: A Phase III, Randomized, Open-label, Multi-center FESTnd Study. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27:70-7. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gleixner KV, Filik Y, Berger D, et al. Asciminib and ponatinib exert synergistic anti-neoplastic effects on CML cells expressing BCR-ABL1 (T315I)-compound mutations. Am J Cancer Res 2021;11:4470-84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson PA, Kantarjian HM, Cortes JE. Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in 2015. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:1440-54. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd Edition. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han Y, Wang S, Wang Z. Effect of Target Therapy with Different Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors on Hematologic and Cytogenetic Remission Rates in Newly Diagnosed Chronic-phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. The Practical Journal of Cancer 2022;37:1726-9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brümmendorf TH, Cortes JE, Milojkovic D, et al. Bosutinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia: final results from the BFORE trial. Leukemia 2022;36:1825-33. 10.1038/s41375-022-01589-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cortes JE, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Deininger MW, et al. Bosutinib Versus Imatinib for Newly Diagnosed Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Results From the Randomized BFORE Trial. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:231-7. 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.7162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.A Phase III Study of Dasatinib vs Imatinib in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Chronic Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (DASISION). NCT00481247.

- 19.Jabbour E, Kantarjian HM, Saglio G, et al. Early response with dasatinib or imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia: 3-year follow-up from a randomized phase 3 trial (DASISION). Blood 2014;123:494-500. 10.1182/blood-2013-06-511592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kantarjian HM, Shah NP, Cortes JE, et al. Dasatinib or imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: 2-year follow-up from a randomized phase 3 trial (DASISION). Blood 2012;119:1123-9. 10.1182/blood-2011-08-376087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kantarjian H, Shah NP, Hochhaus A, et al. Dasatinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2260-70. 10.1056/NEJMoa1002315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li B. Clinical Comparison of Nilotinib and Imatinib in Chronic Granulocytic Leukemia. Medical Diet and Health 2021;19:81-2. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu D, Cheng H, Guo J, et al. Preliminary results of a prospective randomized controlled multicenter clinical trial of dasatinib 70mg/d versus 100 mg/d in the first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase. Journal of Clinical Hematology 2021;34:472-6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L. Comparative Effect of Dasatinib and Nilotinib in Treating Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Resistant or Intolerant to Imatinib. China Health Care & Nutrition 2020;30:266. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cortes JE, Jiang Q, Wang J, et al. Dasatinib vs. imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP) who have not achieved an optimal response to 3 months of imatinib therapy: the DASCERN randomized study. Leukemia 2020;34:2064-73. 10.1038/s41375-020-0805-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geng W, Feng Q. Clinical Efficacy of Dasatinib and Imatinib in the Treatment of Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. China Journal of Pharmaceutical Economics 2018;13:66-8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y. Comparative Effects of Dasatinib and Imatinib in the Treatment of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Contemporary Medicine Forum 2017;15:82-3. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwak JY, Kim SH, Oh SJ, et al. Phase III Clinical Trial (RERISE study) Results of Efficacy and Safety of Radotinib Compared with Imatinib in Newly Diagnosed Chronic Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:7180-8. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hehlmann R, Lauseker M, Saußele S, et al. Assessment of imatinib as first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia: 10-year survival results of the randomized CML study IV and impact of non-CML determinants. Leukemia 2017;31:2398-406. 10.1038/leu.2017.253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu Y. Comparative Study of the Efficacy of Dasatinib and Imatinib in First-line Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Chronic Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Clinical Research 2016;24:31-2. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J, Xie X, Gu W, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety between flumatinib and imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. Journal of Leukemia and Lymphoma 2016;25:526-30. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Q. New diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukemia effect evaluation of chronic phase patients with dasatinib,nilotinib and imatinib treatment. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2016;15:562-4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hjorth-Hansen H, Stenke L, Söderlund S, et al. Dasatinib induces fast and deep responses in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukaemia patients in chronic phase: clinical results from a randomised phase-2 study (NordCML006). Eur J Haematol 2015;94:243-50. 10.1111/ejh.12423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng F, Leng Q, Ji Z, et al. Comparative Study on the Treatment of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia with Dasatinib and Imatinib. Chinese Medical Engineering 2013;21:150. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radich JP, Kopecky KJ, Appelbaum FR, et al. A randomized trial of dasatinib 100 mg versus imatinib 400 mg in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 2012;120:3898-905. 10.1182/blood-2012-02-410688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cortes JE, Kim DW, Kantarjian HM, et al. Bosutinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: results from the BELA trial. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3486-92. 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.7522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hehlmann R, Lauseker M, Jung-Munkwitz S, et al. Tolerability-adapted imatinib 800 mg/d versus 400 mg/d versus 400 mg/d plus interferon-α in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1634-42. 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.0598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saglio G, Kim DW, Issaragrisil S, et al. Nilotinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2251-9. 10.1056/NEJMoa0912614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Preudhomme C, Guilhot J, Nicolini FE, et al. Imatinib plus peginterferon alfa-2a in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2511-21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1004095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petzer AL, Wolf D, Fong D, et al. High-dose imatinib improves cytogenetic and molecular remissions in patients with pretreated Philadelphia-positive, BCR-ABL-positive chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia: first results from the randomized CELSG phase III CML 11 "ISTAHIT" study. Haematologica 2010;95:908-13. 10.3324/haematol.2009.013979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cortes JE, Baccarani M, Guilhot F, et al. Phase III, randomized, open-label study of daily imatinib mesylate 400 mg versus 800 mg in patients with newly diagnosed, previously untreated chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase using molecular end points: tyrosine kinase inhibitor optimization and selectivity study. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:424-30. 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.3724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baccarani M, Rosti G, Castagnetti F, et al. Comparison of imatinib 400 mg and 800 mg daily in the front-line treatment of high-risk, Philadelphia-positive chronic myeloid leukemia: a European LeukemiaNet Study. Blood 2009;113:4497-504. 10.1182/blood-2008-12-191254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adnan-Awad S, Kim D, Hohtari H, et al. Characterization of p190-Bcr-Abl chronic myeloid leukemia reveals specific signaling pathways and therapeutic targets. Leukemia 2021;35:1964-75. 10.1038/s41375-020-01082-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hehlmann R. The New ELN Recommendations for Treating CML. J Clin Med 2020;9:3671. 10.3390/jcm9113671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vener C, Banzi R, Ambrogi F, et al. First-line imatinib vs second- and third-generation TKIs for chronic-phase CML: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Adv 2020;4:2723-35. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kantarjian HM, Hughes TP, Larson RA, et al. Long-term outcomes with frontline nilotinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: ENESTnd 10-year analysis. Leukemia 2021;35:440-53. 10.1038/s41375-020-01111-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cortes JE, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Deininger MW, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in the phase 3 BFORE trial of bosutinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2019;145:1589-99. 10.1007/s00432-019-02894-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gugliotta G, Castagnetti F, Breccia M, et al. Treatment-free remission in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated front-line with nilotinib: 10-year followup of the GIMEMA CML 0307 study. Haematologica 2022;107:2356-64. 10.3324/haematol.2021.280175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson-Ansah H, Maneglier B, Huguet F, et al. Imatinib Optimized Therapy Improves Major Molecular Response Rates in Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Pharmaceutics 2022;14:1676. 10.3390/pharmaceutics14081676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Q, Xu J, Wu J, et al. Analysis of the Curative Effect and Influencing Factors of Nilotinib Second-line and Dasatinib Third-line on Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia Failed First-line and Second-line Treatment. Journal of Experimental Hematology 2022;30:30-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang X, Du X, Wang N, et al. Retrospective clinical analysis of switching nilotinib to patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase with suboptimal response to imatinib. Guangzhou Medical Journal 2020;51:33-7. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hochhaus A, Baccarani M, Silver RT, et al. European LeukemiaNet 2020 recommendations for treating chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2020;34:966-84. 10.1038/s41375-020-0776-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu Y, Qian S. Adverse events of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukemia: a meta-analysis. Chinese Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine 2018;18:1318-28. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang X, Xu N, Yang Y, et al. Comparison of the Efficacy Among Nilotinib, Dasatinib, Flumatinib and Imatinib in Newly Diagnosed Chronic-Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients: A Real-World Multi-Center Retrospective Study. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2024;24:e257-66. 10.1016/j.clml.2024.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gong A, Chen X, Deng P, et al. Metabolism of flumatinib, a novel antineoplastic tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in chronic myelogenous leukemia patients. Drug Metab Dispos 2010;38:1328-40. 10.1124/dmd.110.032326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]