Abstract

An imidazole-containing polyamide trimer, f-ImImIm, where f is a formamido group, was recently found using NMR methods to recognize T·G mismatched base pairs. In order to characterize in detail the T·G recognition affinity and specificity of imidazole-containing polyamides, f-ImIm, f-ImImIm and f-PyImIm were synthesized. The kinetics and thermodynamics for the polyamides binding to Watson–Crick and mismatched (containing one or two T·G, A·G or G·G mismatched base pairs) hairpin oligonucleotides were determined by surface plasmon resonance and circular dichroism (CD) methods. f-ImImIm binds significantly more strongly to the T·G mismatch-containing oligonucleotides than to the sequences with other mismatched or with Watson–Crick base pairs. Compared with the Watson–Crick CCGG sequence, f-ImImIm associates more slowly with DNAs containing T·G mismatches in place of one or two C·G base pairs and, more importantly, the dissociation rate from the T·G oligonucleotides is very slow (small kd). These results clearly demonstrate the binding selectivity and enhanced affinity of side-by-side imidazole/imidazole pairings for T·G mismatches and show that the affinity and specificity increase arise from much lower kd values with the T·G mismatched duplexes. CD titration studies of f-ImImIm complexes with T·G mismatched sequences produce strong induced bands at ∼330 nm with clear isodichroic points, in support of a single minor groove complex. CD DNA bands suggest that the complexes remain in the B conformation.

INTRODUCTION

Mismatched DNA base pairs, including T·G mismatches, play an important role in the formation of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the human genome (1). SNPs, which occur approximately every 1000 bp, are among the most common genetic variation. They are being investigated for many applications, including population genetics and pharmacogenomics, where a small set of SNPs could serve as a diagnostic tool to ensure prescription of ‘the right medicine to the right patient’ (2,3). These SNPs could be identified as mismatched base pairs upon hybridization of the patient’s DNA with standard DNA sequences. As a result, there is currently significant interest in developing small molecules that are capable of specifically recognizing mismatched base pairs (4–6). For example, it was shown using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) that dimers of naphthyridine immobilized on gold chips were capable of detecting G·G mismatches existing in PCR amplification products of a 652 nt sequence of the HSP70-2 gene (6).

T·G mismatched base pairs in DNA are responsible for most of the common mutations leading to formation of tumors in humans. For example, in human bladder carcinoma a G·C→A·T transition at the 3′-G of the GG doublet in codon 12 of the Ha-ras and Ki-ras proto-oncogenes converts them to oncogenes (7–9). A C→T transition to give a T·G mismatch is often introduced by spontaneous deamination of 5-methylcytosine and can arise from errors in replication (10). Although ∼3% of cytosine residues in the human genome are methylated, mutations in 5-methylcytosine account for about one-third of the single base mutations that have been observed in inherited human diseases (10). While specific T·G mismatch repair systems exist in cells, some T·G sequences escape from being repaired (11). Structural analysis of DNAs containing symmetrical T·G mismatches indicates that the mismatches adopt a wobble conformation and structural perturbations are mainly in the vicinity of the mismatch and the nearest neighbor (12,13). Thermodynamic studies indicate that the stability of T·G mismatches depends on their nearest neighbors, with 5′-C and 3′-C neighbors of the G in the mismatch being the most stable (14).

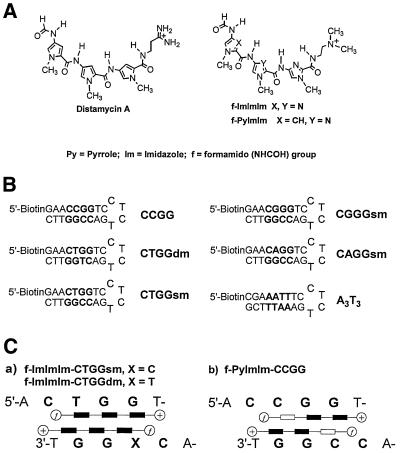

Lee and co-workers demonstrated with NMR spectroscopy that a triimidazole analog of distamycin, f-ImImIm (Fig. 1A), bound cooperatively in a 2:1 complex to a decadeoxyribonucleotide that contained two adjacent T·G mismatched base pairs and to a GC-rich Watson–Crick DNA sequence (15,16). In these complexes the polyamide formed an antiparallel dimer that bound within the minor groove of the oligonucleotides in a staggered manner, as shown in Figure 1C. In the mismatched DNA complex the guanine NH2 group of the wobble T·G base pair formed two specific hydrogen bonds to the side-by-side imidazole/imidazole pair (15). The guanine NH2 group has also been observed to be necessary for optimal binding of Vsr mismatch endonuclease during recognition of the G·T mismatch (17). The results of the NMR studies suggested that a side-by-side imidazole/imidazole pair could recognize T·G or G·T, thus adding to the pairing rules reported by Dervan and collaborators (18,19). However, the molecular specificity for discrimination of T·G mismatches from canonical sequences or other mismatches by the imidazole/imidazole pair has not been investigated. Thermodynamics and kinetics studies could provide the basis for the definition of new recognition rules for polyamides, in this case extended to mismatches in DNA.

Figure 1.

(A) Chemical structures of trimer polyamides (f-ImIm is similar to f-ImImIm but with only two heterocycles). (B) DNA hairpins used in this study. CCGG and A3T3 are canonical sequences; CTGGdm contains two T·G mismatches; CTGGsm, CGGGsm and CAGGsm contain a T·G, a G·G and an A·G mismatch, respectively. (C) Proposed models of the complexes formed between the polyamides in (A) and their target sequences in (B). The ligands are stacked in a staggered antiparallel and side-by-side fashion. The imidazole units are represented by filled rectangles, pyrroles by open rectangles, the peptide bonds by horizontal lines, (CH2)2NMe2H+ units by positive signs in circles and formamido groups (NHCOH) by ¶ in circles.

In this paper we report the ability of f-ImImIm to specifically discriminate T·G from Watson–Crick as well as from other mismatched base pairs. The related polyamide f-PyImIm was predicted to bind more strongly to a CCGG matched sequence (Fig. 1B) than to the mismatched sequence and was included as a control. In addition, f-ImIm was included to test the effect of the number of heterocycles on binding. The predicted models of the complexes that could form between the ligands and the hairpin oligonucleotides are shown in Figure 1C. The DNA-binding properties of the compounds shown in Figure 1A were determined using a combination of SPR with DNA immobilized on a biosensor surface, thermal melting (Tm) and circular dichroism (CD) titration studies. The use of SPR to study the interactions of polyamides with DNA is advantageous because the interactions are studied in real time and both thermodynamics and kinetics can be determined from each experiment.

The hairpin sequences depicted in Figure 1B were selected to satisfy several criteria. Upon folding they contain a GC-rich core of 4 bp that will be recognized by the Im/Im, Py/Im or Im/Py pairs. A T base was placed at the 3′ end of each recognition sequence for favorable interactions with the cationic tails of the polyamides. Studies with oligomers that contain a single mismatch were designed to answer the question of whether f-ImImIm is able to recognize a single T·G mismatch. Finally, sequences with A·G and G·G mismatches were selected to determine if the Im/Im pair was able to distinguish T·G from other G-containing mismatches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and biochemicals

Buffers. The 0.01 M 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer, pH 6.25, contained 0.001 M EDTA and either 0.2 M NaCl (MES20) or no NaCl (MES00). The buffer used in SPR experiments contained 0.001% surfactant P20 (BIAcore AB) to reduce the possibilities of non-specific binding to the fluidics and the chip surface. The 0.01 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, contained 0.05 M NaCl and 0.00025 M EDTA. The 5× TBE used for polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was prepared containing 0.5 M Tris base (Trizma), 0.5 M boric acid and 20 ml of 0.5 M EDTA solution, pH 8.0, in 1 l. 1× TBE was prepared by diluting this solution five times.

Compounds (ligands). Distamycin A was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. and used without further purification. N-[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]-1-methyl-4-{1-methyl-4-[4-formamido-1-methylimidazole-2-carboxamide]imidazole-2-carboxamido}imidazole-2-carboxamide (f-ImImIm) and N-[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]-1-methyl-4-[4-formamido-1-methylimidazole-2-carboxamide]imidazole-2-carboxamide (f-ImIm) were synthesized as described previously (20). The synthesis and characterization of N-[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]-1-methyl-4-{1-methyl-4-[4-formamido-1-methylpyrrole-2-carboxamido]imidazole-2-carboxamido}imidazole-2-carboxamide (f-PyImIm) was as described previously (21).

DNA hairpins. The DNA hairpins were obtained as anion exchange, HPLC-purified or as gel filtration grade products (Midland Certified Reagent Co.). The gel filtration products were purified by PAGE as described in Supplementary Material.

SPR experiments

Biosensor analysis. Real-time interaction analysis was performed using SPR with a BIAcore 2000 instrument (BIAcore AB, Uppsala, Sweden) as previously described (21). In general, 2 × 10–3 M stock solutions of the polyamides were prepared by dissolving the solid in MES20 buffer. This buffer contained the amount of HCl necessary to provide ∼1 equiv. HCl per mol compound. These stock solutions were divided in different portions and kept frozen. The samples for the SPR experiments were prepared by dilution of the stock solutions using MES20. The 5′-biotinylated DNA sequences (Fig. 1B) were immobilized on SA sensor chips (streptavidin-coated chips). The DNA solution was continuously injected until an SPR signal increase of ∼300 resonance units (RU) was reached. This RU value for DNA was used to convert the compound binding response in RU to moles bound (see Processing the SPR data below). 300 RU of DNA are equivalent to ∼0.3 ng DNA mm–2 on the surface of the chip.

SPR experiments. The experiments were performed in MES20 at 25°C. To generate the binding data variable volumes of samples at different concentrations were injected through DNA-containing cells and a reference cell (streptavidin-coated surface with no DNA) simultaneously. The SPR signal in RU is proportional to the amount of polyamide bound to the DNA immobilized on the surface. For compounds with fast kinetics the volume injected was constant and that necessary to reach steady-state. For compounds with slow kinetics the volume injected was between 250 µl for the lowest concentrations and 35 µl for the highest concentrations. Injection of the compound was followed by injection of running buffer to follow complex dissociation. At the end of the experiment a regeneration buffer (10 mM Gly, pH 2, or MES buffer with 400 mM NaCl) was used to remove any remaining polyamide from the surface. The SPR signal in RU is proportional to the amount of polyamide bound to the DNA immobilized on the surface.

Data processing. Sensorgrams were obtained for each flow cell and responses from the reference cell were used to correct for bulk refractive index changes (22). Double reference subtraction was used to eliminate any difference in response between buffer with the reference and the other flow cells. Average fitting of the sensorgrams at the steady-state level was performed with the BIAevaluation software. To obtain the affinity constants the data generated were fitted to different interaction models using Kaleidagraph for non-linear least squares optimization of the binding parameters using the following equation:

r = [K1 × Cfree + 2 × K1 × K2 × (Cfree)2 + 3 × K1 × K2 × K3 × (Cfree)3]/ 1 + K1 × Cfree + K1 × K2 × (Cfree)2 + K1 × K2 × K3 × (Cfree)3

where K2 and K3 = 0 for one binding site, K3 = 0 for two binding sites and K1, K2 and K3 are the macroscopic binding constants and Cfree is the concentration of the compound in solution, which is the same as the concentration at which the solution is injected. r = RUeq/RUmax and represents mol compound bound per mol DNA hairpin, where RUeq is the SPR response at the steady-state level, RUmax is the maximum response for binding one molecule of compound per binding site and is predicted as previously described (23).

Kinetics parameters in general were obtained by global fitting of the kinetic data using the BIAevaluation program. The sensorgrams were fitted with the following model:

dB/dt = –(ka1 × A × B – kd1 × AB)

dAB/dt = (ka1 × A × B – kd1 × AB) – (ka2 × A × AB – kd2 × A2B)

dA2B/dt = (ka2 × A × AB – kd2 × A2B)

where A is the molar concentration of the polyamides, B, AB and A2B are quantities corresponding to the amount of DNA and 1:1 or 2:1 complexes and ka and kd are the corresponding association and dissociation rate constants and are defined according to the following model:

ka1 ka2

polyamide + DNA ↔ polyamide:DNA + polyamide ↔ polyamide2:DNA

kd1 kd2

CD spectroscopy

A 1 mm path length cell was used and all experiments were done at 25°C. Specific aliquots of the matched (5′-GAACCGGTTCTTTTTGAACCGGTTC-3′) and T·G mismatch-containing (5′-GAACTGGTTCTTTTTGAACTGGTTC-3′) hairpin duplexes (0.003 µmol (bp) µl–1), from Operon Technologies, were titrated to a fixed 2 µmol solution of f-ImImIm (100 µl). The resulting ratios were between 0.12 and 3.3 (mol ligand to mol DNA bp). The experiments were performed in phosphate buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.2, 50 mM NaCl, 0.25 mM EDTA). The sensitivity was set at 1 mdeg and the scan speed was set at 200 nm min–1. Three scans were accumulated and averaged by the computer.

Thermal melting experiments with UV-VIS spectroscopy

Thermal melting experiments were conducted in MES00. The concentration of the DNA was ∼1 × 10–6 M in hairpin and the concentration of the compounds was that to obtain ratios of compound per DNA hairpin equal to 1 and 2. The experiments were done using a Cary spectrophotometer in the multicell/multiramp temperature mode. To obtain absorbance versus temperature profiles the absorbance of the solutions were measured at 260 nm as the solutions were heated or cooled at a ramp rate of 0.5°C min–1 in a temperature range between 10 and 95°C.

RESULTS

SPR experiments: stoichiometry and binding constants

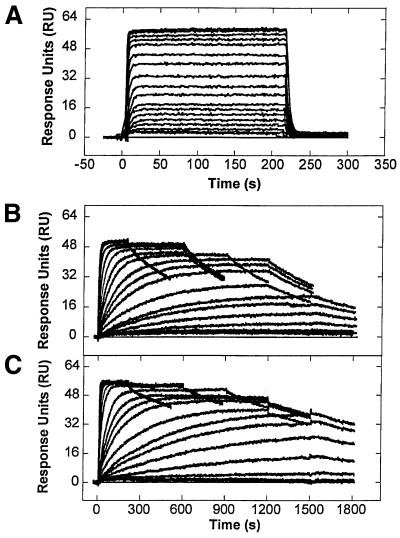

Typical SPR sensorgrams for the interaction of f-ImImIm at different concentrations with hairpin oligonucleotides that contain the core sequences CCGG, CTGGsm and CTGGdm (Fig. 1B) are shown in Figure 2. With all three DNAs the maximum instrument response (RUmax) obtained in the steady-state region corresponds to approximately twice the predicted response for binding of one molecule of the compound and indicates a 2:1 stoichiometry (2 mol compound per mol DNA hairpin). The SPR method is thus a sensitive indicator of stoichiometry in systems of this type. As can be seen in Figure 2, the kinetics of the interactions differ markedly for the same polyamide binding to different DNA sequences. Figure S1 (Supplementary Material) shows sensorgrams for the interaction of f-ImImIm at a fixed concentration (5 µM) with several of the hairpin oligonucleotides. With comparable amounts of DNA on the surface the intensity of the sensorgram responses demonstrate a significant preference of f-ImImIm for binding to T·G mismatch-containing DNAs over the canonical CCGG or the A·G and G·G mismatch-containing sequences.

Figure 2.

SPR sensorgrams for the interaction of f-ImImIm with (A) CCGG, (B) CTGGsm and (C) CTGGdm. The concentration of the unbound polyamide varies from 7.5 × 10–7 to 2.6 × 10–5 M in (A), from 1.0 × 10–9 to 2.0 × 10–6 M in (B) and 4.0 × 10–6 M in (C). All the experiments were done in MES20 at 25°C.

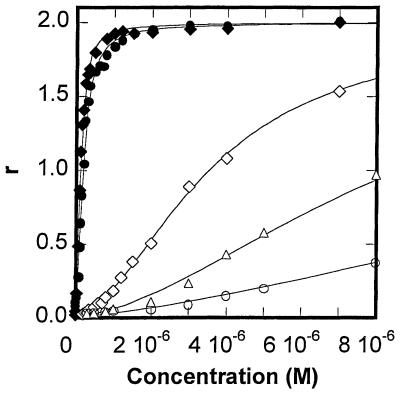

Results such as those in Figure 2 were used to construct binding curves for the interaction of f-ImImIm with several DNA sequences (Fig. 3). Since the stoichiometry was defined as 2:1, all curves were fitted with a model that has a 2:1 polyamide:DNA stoichiometry (Materials and Methods). Even in cases of relatively weak binding a 2:1 stoichiometry is approached at high concentration, as shown for f-ImImIm with CCGG, CGGGsm and CAGGsm in Supplementary Material (Fig. S2). For all Im-containing polyamides K1 is significantly less than K2, indicating positive cooperativity in binding. Because of the correlation between K1 and K2, the error in fitting individual values of K1 and K2 is larger than for the product, K1 × K2, for dimer binding. For the most accurate comparison of binding of polyamides to DNA in this work K values (K = [K1 × K2]1/2) are reported in Table 1. By reporting the square root all results are reported on a per bound molecule basis and direct comparison between binding of monomers and dimers, as well as with literature results, is possible.

Figure 3.

Best fit of r (mol compound per mol DNA hairpin) versus the concentration of unbound f-ImImIm in the interaction with CTGGsm (filled circles), CTGGdm (filled diamonds), CCGG (open diamonds), CAGGsm (open triangles) and CGGGsm (open circles). r corresponds to the ratio of steady-state RU values (obtained from results such as those in Fig. 2) to the maximum response (RUmax) expected for one molecule of compound. All the experiments were done in MES20 at 25°C. A graph at high f-ImImIm concentration is shown in Supplementary Material (Fig. S2).

Table 1. Equilibrium association constantsa, K (M–1), for binding of polyamides to the DNA sequences shown in Figure 1.

| Compound | CCGG | CTGGdm | CTGGsm | CAGGsm | CGGGsm | A3T3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f-ImImIm | 2.1 × 105 | 1.2 × 107 | 6.5 × 106 | 1.9 × 105 | 7.8 × 104 | 5.9 × 103 |

| f-ImIm | 6.0 × 103 | 6.9 × 103 | 1.0 × 104 | 3.4 × 103 | 2.3 × 103 | 3.1 × 103 |

| f-PyImIm | 8.3 × 105 | 2.5 × 104 | 2.3 × 105 | 2.4 × 105 | 6.1 × 104 | 2.5 × 104 |

| Distamycin | 4.1 × 104 | 4.7 × 103 | 1.2 × 104 | 1.5 × 104 | 1.2 × 104 | 1.7 × 107 |

aThe equilibrium constants reported here are defined as the square root of the product of equilibrium association constants, K = (K1 × K2)1/2. K1 and K2 were obtained by fitting the SPR binding curves at the steady-state level versus concentration of polyamide as discussed in Materials and Methods. The errors for the constants in this table are <10% for constants >1 × 105, 20% for those from 1 × 105 to 3 × 104 and 20–40% for those <3 × 104.

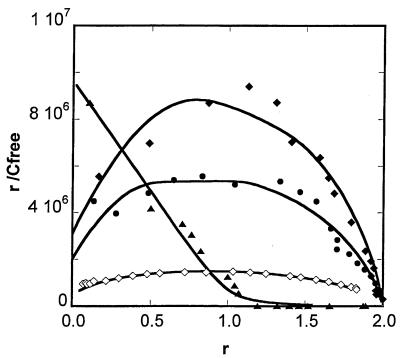

Distamycin was also investigated as a well-characterized reference polyamide (24–27). It binds to the A3T3 sequence in a 2:1 complex but, unlike the Im-containing polyamides, it binds with negative cooperativity. K2 is 16 times greater than K1 for the binding of f-ImImIm to CTGGdm, for example, but in the binding of distamycin to A3T3, K2 is ∼390 times lower than K1. This behavior difference is better visualized in a Scatchard plot (Fig. 4). Distamycin has a typical Scatchard plot for binding of a first molecule with a large association constant followed by a second with a lower K, but f-ImImIm has curves typical of positive cooperativity in binding. The Im-containing polyamide f-PyImIm (Fig. 1A) was also investigated since it is predicted to bind preferentially to the same CCGG Watson–Crick sequences as f-ImImIm (Fig. 1C). The results in Table 1 show that f-PyImIm binds to the CCGG duplex about four times more strongly than f-ImImIm, but it binds to the mismatch sequence CTGGdm about 500 times worse than f-ImImIm. It binds about 30 times more weakly to the single T·G mismatch sequence (Table 1). The f-ImImIm polyamide is thus unique in its ability to selectively recognize T·G mismatched base pairs.

Figure 4.

Scatchard plot (r/Cfree versus r) for the interaction of f-ImImIm with CTGGsm (filled circles), CTGGdm (filled diamonds) and CCGG (open diamonds) and the interaction of distamycin with A3T3 (solid triangles). r values correspond to mol compound per mol DNA hairpin and were calculated based on SPR data (sensorgrams in Figs 2 and S3). Cfree corresponds to the concentration of compound injected through the sensor chip flow cells. Values of r/Cfree for the distamycin–A3T3 and f-ImImIm–CCGG complexes were multiplied by a factor of 0.05 and 20, respectively. The smooth curves correspond to the data simulated based on the equilibrium constants obtained by direct fitting.

In summary, the imidazole-containing polyamides bind to DNA in a 2:1 complex with significant positive cooperativity. It is also clear from the results in Table 1 that f-ImImIm binds strongly and with good specificity to DNA duplex sequences that contain T·G mismatched base pairs. This polyamide binds to its recognition sequence, CTGGdm, with similar affinity to distamycin binding to A3T3. f-ImImIm still binds more than 30 times more strongly to the single T·G mismatch-containing sequence, CTGGsm, than to any of the other sequences, including the recognition Watson–Crick sequence CCGG. On the other hand, the binding constants for the diimidazole f-ImIm reveal that this compound binds with low affinity and specificity to all of the sequences studied. This suggests that polyamides must contain more than two heterocycles in order to show significant affinity for DNA recognition sequences. Finally, the polyamide f-PyImIm shows significant affinity for CCGG, but shows little specificity for T·G mismatched base pairs relative to f-ImImIm.

Kinetics studies

The sensorgrams given in Figure 2 show large and easily visualized differences in kinetic behavior and they can be used to determine kinetic constants as described in Materials and Methods. f-ImImIm associates and dissociates rapidly from CCGG (Fig. 2A), but it associates and dissociates much more slowly from CTGGsm and CTGGdm (Fig. 2B and C and Table 2). In binding to the T·G mismatched sequences, even after injection of the compound has been stopped and the flow of buffer had been initiated for 400 s, ∼70% of f-ImImIm remains bound. The rates for dissociation of the second molecule (kd1) of f-ImImIm from the complexes with the mismatched DNAs CTGGdm and CTGGsm are 0.59 and 0.70 s–1, respectively (see Materials and Methods for definition of the rate constants). On the other hand, the first molecule to dissociate does so at the considerably lower rates (kd2) of 6 × 10–4 and 1.3 × 10–3 s–1 and this results in an overall very stable complex. The association and dissociation processes in the interaction of f-ImImIm with all matched oligonucleotides are much faster and the kinetic parameters cannot be determined by the SPR technique. In general, in <10 s the complexes are totally formed or dissociated. Therefore, the half-life should be <5 s. Based on this and on the largest dissociation rate constant obtained for the interactions with slower kinetics we report this dissociation rate constant as >0.7 s–1 (Table 2).

Table 2. Kinetics of association and dissociation rate constantsa for the interaction of polyamides with DNA.

| Compound | DNA sequence | ka1 (M–1 s–1) | kd1 (s–1) | ka2 (M–1 s–1) | kd2 (s–1) | Keq (M–1)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f-ImImIm | CCGGc | >0.7 | >0.7 | |||

| CTGGdm | 8.1 × 104 | 0.59 | 2.6 × 105 | 0.0006 | 7.7 × 106 | |

| CTGGsm | 8.2 × 104 | 0.70 | 3.5 × 105 | 0.0013 | 5.6 × 106 | |

| f-PyImIm | CCGG | 7.0 × 104 | 0.58 | 2.3 × 105 | 0.030 | 9.9 × 105 |

| Distamycin | A3T3d | 2.3 × 105 | 0.002 | ∼3.5 × 104e | 0.020 |

aSee model in Materials and Methods for formation of the complexes and definition of the kinetics rate constants reported in this table.

bEqual to the square root of the product of equilibrium association constants, (K1 × K2)1/2, calculated from the kinetic parameters (ka and kd).

cBy ∼10 s or less the complex is totally formed /dissociated and the process is too fast to be determined by this technique.

dkd obtained by fitting the dissociation phase of the sensorgrams with the 1:1 (Langmuir) binding model predefined in the BIAevaluation program. ka was calculated from the slope of kobs (observed association rate) versus concentration. kobs was calculated by fitting the association phase to the same model.

eEstimated as the product of K2 (macroscopic association constant for the second molecule) from steady-state measurements and kd2.

As shown in Table 2, the association and dissociation rates for distamycin with A3T3 are quite different than for f-ImImIm with the T·G mismatched sequences. The association of the first molecule of distamycin with A3T3 is faster than the binding of f-ImImIm to CTGGdm or CTGGsm, while dissociation of the second molecule of distamycin is slower than the dissociation of f-ImImIm. A set of sensorgrams corresponding to the interaction of distamycin with A3T3 is shown in Supplementary Material (Fig. S3).

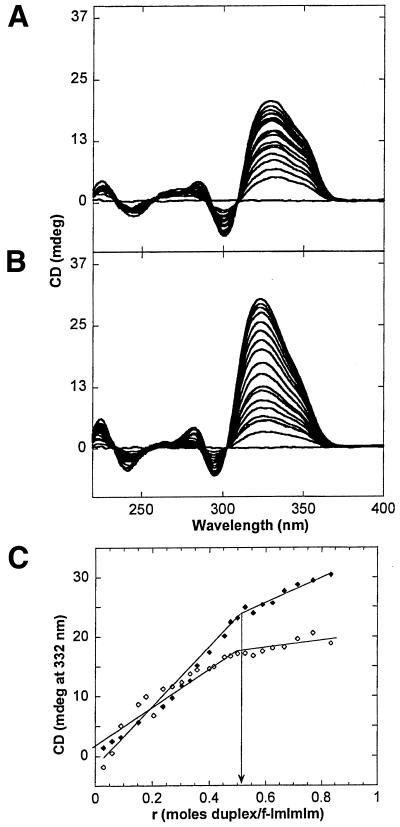

Circular dichroism titration experiments

Figure 5 shows the CD spectra for the interaction of f-ImImIm with CCGG (Fig. 5A) and CTGGdm (Fig. 5B) at fixed polyamide concentrations and variable amounts of DNA. The polyamide does not show any CD signal in the region studied. CD spectra for the free DNAs are shown for reference in Supplementary Material (Fig. S4). Addition of the DNA hairpins to the ligand solution produced strong induced CD signals above 300 nm. The appearance of the induced CD signal is consistent with the binding of ligands to the minor groove (16,20,26). Distinct isodichroic points are apparent in the overlaid CD titration curves, suggesting a single mechanism of binding of the ligands, presumably by binding of f-ImImIm as a side-by-side dimer to the minor groove. The DNA bands remained in the B form, indicating that binding of the ligand did not cause any significant perturbations to the DNA conformation. Figure 5C shows the titration curve generated by plotting the induced CD signal at 332 nm after each addition of DNA. The inflection points observed at a ratio of duplex to compound of about 0.5 are indicative of stoichiometries of binding of 2:1 (2 mol compound per mol DNA hairpin) for both the CCGG and the CTGGdm sequences, in agreement with the SPR results.

Figure 5.

CD spectra for the titration of f-ImImIm with (A) CCGG and (B) CTGGdm. The curves correspond to 0.12 to 3.33 mol ligand to mol DNA bp. The line that passes through zero corresponds to the free ligand. CD spectra for the free DNA are in Supplementary Material (Fig. S4). (C) Titration curves for CCGG (open diamonds) and CTGGdm (filled diamonds), generated by plotting the induced CD signal in (A) and (B) at 332 nm after each addition of DNA. The inflection points observed at a ratio of duplex to compound of ∼0.5 is indicative of stoichiometries of binding of 2 mol compound per mol DNA hairpin.

UV-VIS thermal melting experiments

The results from thermal melting experiments for a ratio of 2 mol polyamide per mol DNA hairpin are in qualitative agreement with the SPR results. In general an appreciable increase in the melting temperature of the DNA is observed for the DNA–polyamide complexes for which the square root of the combined binding constant is >5 × 105 M–1. f-ImImIm produces an increase in the melting temperature (ΔTm) of CTGGdm and CTGGsm of ∼13 and 5.6°C, respectively, while no significant Tm increase was observed with other DNA sequences. For the free duplexes and 2:1 complexes that showed significant increases in Tm, monophasic transitions were obtained. Tm curves at a 1:1 ratio are biphasic, as expected for a 2:1 complex (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5).

DISCUSSION

Stoichiometry of complexes

Lee and co-workers found by NMR methods that f-ImImIm binds as a dimer to the DNA minor groove and spans 6 bp (15,16). Our SPR and CD studies confirm that the stoichiometry of complex formation is 2:1 for Im-containing polyamides at the much lower concentrations of these experiments relative to NMR studies. Binding affinities for different DNA sequences vary widely, however, and saturation was not reached for some complexes until a high concentration (Fig. S2). Thermal melting experiments provide qualitative agreement with a 2:1 complex (Fig. S5). Distamycin was used as a control and formed a 2:1 complex with A3T3, in agreement with previous reports (27). It is thus clear that all polyamides investigated in this study bind to their DNA recognition sites in a 2:1 complex (Fig. 1).

Binding constants and cooperativity

The binding constants for the compounds with six different DNA hairpin oligonucleotides (Table 1) were determined by fitting SPR results. The use of SPR has advantages in comparison with the traditionally used techniques for the study of DNA–small molecule interactions. With this technique strong absorbance or fluorescence of the sample and radiolabeling are not necessary and the concentrations used can be very low, so that association kinetics can be monitored. In most cases kinetic and steady-state information can be obtained in a single experiment. The comparisons with the SPR binding results in Table 1 are striking and they show that f-ImImIm interacts with strong affinity and high specificity for the T·G mismatch-containing sequences. The binding constants for these interactions are comparable with the binding of distamycin to the canonical A3T3 sequence. The binding of f-ImImIm is highly cooperative, with K1 over 10 times lower than K2 for CTGGdm and CTGGsm. f-ImImIm binds over 30-fold more strongly to CTGGdm and CTGGsm than to the target canonical sequence CCGG. It also binds much more tightly to CTGGdm than to the A·G and the G·G mismatch-containing sequences (Table 1). Finally, f-ImImIm binds more than 1000-fold tighter to the T·G mismatch-containing DNAs than to A3T3. These combined results define the strong preference of the side-by-side Im/Im pair for a T·G mismatch over C·G, G·C, T·A or A·T base pairs and over A·G or G·G mismatches. The pyrrole polyamide distamycin, on the other hand, binds over 3000-fold weaker to CTGGdm than to A3T3.

A diimidazole compound, f-ImIm, binds very weakly to all DNA sequences (Table 1), with only slightly higher affinity for CTGGsm than for other DNAs. These results show that at least three imidazole rings per monomer are necessary to bind strongly to T·G mismatch-containing sequences. On the other hand, f-PyImIm has very low affinity for any of the mismatches, but has better affinity for the CCGG Watson–Crick sequence. The results show that f-PyImIm prefers to stack in a staggered mode that matches CCGG (Fig. 1). It should be noted that f-PyImIm could stack in a completely overlapped mode (21) to form Im/Im pairs and thereby gain some binding affinity for the CTGGsm sequence. However, this mode of DNA interaction must be less thermodynamically favorable for f-PyImIm binding to CTGGsm because the binding constants are about 3.5 times weaker than those of f-PyImIm binding to CCGG.

The preferential binding of the side-by-side dimer of f-ImImIm with T·G mismatch-containing oligomers is corroborated by the CD titration and UV-VIS melting experiments. Under identical conditions, and at a ratio of two molecules of compound per molecule of DNA hairpin, the induced CD signal is larger for the complex with CTGGdm (Fig. 5B) than for the complex with CCGG (Fig. 5A). In the ΔTm studies f-ImImIm enhances the melting temperature of the double T·G mismatch-containing CTGGdm oligomer to a significantly larger value than those for its binding to the other DNAs and for the binding of f-PyImIm to its cognate DNA sequence.

Kinetic studies

It is evident from the SPR experiments that the enhanced binding affinity of f-ImImIm to T·G mismatches is a result of slow dissociation of the ligands from the oligomers (see Fig. 2 as an example). This highly stable complex is presumably due to an optimum fit with favorable hydrogen bonding interactions between the exocyclic guanine 2 NH2 and the imidazole moieties. f-ImImIm shows similar slow dissociation behavior with CTGGdm and CTGGsm. Fast association and dissociation rates are observed in the interaction of f-ImImIm with all other sequences, including the A·G and G·G mismatch-containing sequences (Fig. S1). f-PyImIm and distamycin associate and dissociate rapidly with CTGGdm and CTGGsm and in general from all the other sequences, with the exception of f-PyImIm with CCGG and distamycin with A3T3.

Our results show that distamycin binds as a dimer to A3T3 with negative cooperativity while f-ImImIm binds with positive cooperativity to CTGGdm, CTGGsm and even CCGG, as shown by the Scatchard plots (Fig. 4), by comparison of the binding constants (K1 and K2) and finally by comparison of the rate constants (Table 2). The positive cooperativity observed for f-ImImIm can be explained in terms of sequence-dependent minor groove width. It has been shown that AT-rich sequences of DNA have a narrower minor grove than GC-rich sequences (28–31). When the first molecule of f-ImImIm binds to any of the GC-rich sequences the molecule is not thick enough to make optimum van der Waals contacts with the walls of the groove. Upon binding of the second molecule of f-ImImIm the contacts are maximized, forming a very tight cooperative complex with a very slow dissociation rate for the first molecule of the bound dimer. In contrast, the first molecule of distamycin binds well to the narrower minor groove of A3T3, the dimer forms with negative cooperativity and the first molecule of the dimer dissociates more rapidly than the second.

Recognition of DNA mismatches

Two recent publications describe the development of molecules capable of recognizing DNA mismatches (5,6). One compound is a cleaving agent that recognizes destabilized regions on the DNA (5) and was able to recognize a single mismatch in a 2725 bp linear plasmid. Another new agent is capable of specifically recognizing G·G mismatches and has low affinity for other known mismatches (6). The results presented here show that a side-by-side Im/Im pair can specifically recognize T·G mismatched base pairs in DNA, thus adding to the recognition rules of the polyamides and adding a powerful new agent for specific recognition of the most common DNA mismatch (32). When one Im/Im pair is formed during the stacking of polyamides, the stacked dimer can recognize a T·G mismatched base pair and can distinguish it from Watson–Crick base pairs, as well as from other mismatches (Table 1). Results with f-ImIm, however, suggest that the compound should have at least three heterocycles in order to show satisfactory affinity for DNA sequences. Compounds such as f-PyImIm that do not form an Im/Im pair in the staggered stacking mode (Fig. 1) are not able to recognize T·G mismatches and their preference is for Watson–Crick base pairs in DNA. The results presented here provide the basis for the development of a linked triimidazole agent that, when covalently attached to a sensor chip, could be used in the detection of T·G mismatch-containing DNA. The synthesis of such compounds and development of such chips are underway.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at NAR Online. Purification of CTGGsm; additional SPR sensorgrams and fitting curves for binding of f-ImImIm to different sequences; SPR sensorgrams for distamycin binding to A3T3; CD spectra of CCGG and CTGGdm hairpin duplexes; thermal melting curve for the CTGGdm and its complex with f-ImImIm.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Financial support through NIH grant GM-61587 and from the Georgia Research Alliance (to W.D.W.) and from the NSF-REU and Research Corporation (to M.L.) is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sachidanandam R., Weissman,D., Schmidt,S.C., Kakol,J.M., Stein,L.D., Marth,G., Sherry,S., Mullikin,J.C., Mortimore,B.J., Willey,D.L., Hunt,S,E. et al. (The International SNP Map Working Group) (2001) A map of human genome sequence variation containing 1.4 million single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nature, 409, 928–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans W.E. and Relling,M.V. (1999) Pharmacogenomics: translating functional genomics into rational therapeutics. Science, 286, 487–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ligget S.B. (2001) Pharmacogenetic applications of the human genome project. Nature Med., 7, 281–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trotta E. and Paci,M. (1998) Solution structure of DAPI selectively bound in the minor groove of a DNA T.T mismatch-containing site: NMR and molecular dynamics studies. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 4706–4713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson B.A., Alekseyev,V.Y. and Barton,J.K. (1999) A versatile mismatch recognition agent: specific cleavage of a plasmid DNA at a single base mispair. Biochemistry, 38, 4655–4662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakatani K., Sando,S. and Saito,I. (2001) Scanning of guanine-guanine mismatches in DNA by synthetic ligands using surface plasmon resonance. Nat. Biotechnol., 19, 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Land H., Parada,L.F. and Weinberg,R.A. (1983) Cellular oncogenes and multistep carcinogenesis. Science, 222, 771–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almoguera C., Shibata,D., Forrester,K., Martin,J., Arnheim,N. and Perucho,M. (1988) Most human carcinomas of the exocrine pancreas contain mutant c-K-ras genes. Cell, 53, 549–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe H., Ha,A., Hu,Y.X., Ohtsubo,K., Yamaguchi,Y., Motoo,Y., Okai,T., Toya,D., Tanaka,N. and Sawabu,N. (1999) K-ras mutations in duodenal aspirate without secretin stimulation for screening of pancreatic and biliary tract carcinoma. Cancer, 86, 1441–1448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lall L. and Davidson,R.L. (1998) Sequence-directed base mispairing in human oncogenes. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 4659–4669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toft N.J. and Arends,M.J. (1998) DNA mismatch repair and colorectal cancer. J. Pathol., 185, 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hare D., Shapiro,L. and Patel,D.J. (1986) Wobble dG.dT pairing in the right-handed DNA: solution conformation of the d(C-G-T-G-A-A-T-T-C-G-C-G) duplex deduced from distance geometry analysis of nuclear Overhauser effect spectra. Biochemistry, 25, 7445–7456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunter W.N., Brown,T., Kneale,G., Anand,N.N., Rabinovitch,D. and Kennard,O. (1987) The structure of guanosine-thymidine mismatches in B-DNA at 2.5 Å resolution. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 9962–9970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allawi H.T. and SantaLucia,J.,Jr (1997) Thermodynamics and NMR of internal G·T mismatches in DNA. Biochemistry, 36, 10581–10594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang X.-L., Hubbard,R.B., Lee,M., Tao,Z.-F., Sugiyama,H. and Wang,A.H.-J. (1999) Imidazole-imidazole pair as a minor groove recognition motif for T:G mismatched base pairs. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 4183–4190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang X.-L., Kaenzig,C., Lee,M. and Wang,A.H.-J. (1999) Binding of AR-1-144, a tri-imidazole DNA minor groove binder, to CCGG sequence analyzed by NMR spectroscopy. Eur. J. Biochem., 263, 646–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox K.R., Allinson,S.L., Sahagun-Krause,H. and Brown,T. (2000) Recognition of GT mismatches by Vsr mismatch endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 2535–2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dervan P.B. and Burlii,R.W. (1999) Sequence-specific DNA recognition by polyamides. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol., 3, 688–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellervik U., Wang,C.C.C. and Dervan,P.B. (2000) Hydroxybenzamide/pyrrole pair distinguishes T.A from A.T base pairs in the minor groove of DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 122, 9354–9360. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee M., Rhodes,A.L., Wyatt,M.D., Forrow,S. and Hartley,J.A. (1993) base sequence recognition by oligo(imidazolecarboxamide) and terminus-modified analogues of distamycin deduced from circular dichroism, proton nuclear magnetic resonance and methidiumpropylethylenediaminetetraacetate-iron(II) footprinting studies. Biochemistry, 32, 4237–4245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lacy E.R. Le,N.M., Price,C.A., Lee,M. and Wilson,W.D. (2002) Influence of a terminal formamido group on the sequence recognition of DNA by polyamides. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 124, 2153–2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myszka D.G. (1999) Improving biosensor analysis. J. Mol. Recognit., 12, 279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis T.M. and Wilson,W.D. (2000) Determination of the refractive index increments of small molecules for correction of surface plasmon resonance data. Anal. Biochem., 284, 348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pelton J.G. and Wemmer,D.E. (1989) Structural characterization of a 2:1 distamycin A.d(CGCAAATTGCG) complex by two dimensional NMR. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 5723–5727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wemmer D.E., Geierstanger,B.H., Fagan,P.A., Dwyer,T.J., Jacobsen,J.P., Pelton,J.G., Ball,G.E., Leheny,A.R., Chang,W.-H., Bathini,Y., Lown,J.W., Rentzeperis,D., Marky,L.A., Singh,S. and Kollman,P. (1994) Minor groove recognition of DNA by distamycin and its analogs. In Sarma,R.H. and Sarma,M.H. (eds), Structural Biology: The State of the Art. Adenine Press, New York, NY, Vol. II, pp. 301–323.

- 26.Rentzeperis D., Marky,L.A., Dwyer,T.J., Geierstanger,B.H., Pelton,J.G. and Wemmer,D.E. (1995) Interaction of minor groove ligands to an AAATT/AATTT site: correlation of thermodynamic characterization and solution structure. Biochemistry, 34, 2937–2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelton J.G. and Wemmer,D.E. (1990) Binding modes of distamycin a with d(CGCAAATTTGCG)2 determined by two-dimensional NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 112, 1393–1399. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamelberg D., Williams,L.D. and Wilson,W.D. (2001) Influence of the dynamic positions of cations on the structure of the DNA minor groove: sequence dependent effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 123, 7745–7755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tjandra N., Tate,S., Ono,A., Kainosho,M. and Bax, Ad. (2000) The NMR structure of a DNA dodecamer in an aqueous dilute liquid crystalline phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 122, 6190–6200. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duan Y., Wilkosz,P., Crowley,M. and Rosenberg,J.M. (1997) Molecular dynamics simulation study of DNA dodecamer d(CGCGAATTCGCG) in solution: conformation and hydration. J. Mol. Biol., 272, 553–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young M.A., Ravishanker,G. and Beveridge,D.L. (1997) A 5-nanosecond molecular dynamic trajectory for B-DNA: analysis of structure, motions and solvation. Biophys. J., 73, 2313–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allawi H.T. and SantaLucia,J.,Jr (1998) NMR solution of a DNA dodecamer containing single G·T mismatches. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 4925–4934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.