Abstract

This study explores the microstructural characteristics of gadolinium (Gd)-rich phases in titanium (Ti) alloys through comprehensive electron microscopy analysis. The Ti alloys were produced using plasma arc melting and subsequently hot-forged. Elaborate material characterization, including scanning electron microscopy, electron backscatter diffraction, and energy dispersive spectroscopy, revealed the formation of round or angular Gd oxides and elongated Gd-rich grains within the alloy. High-magnification transmission electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction confirmed the presence of the FCC-type γ-Gd phase, influenced by the oxygen intake during casting, coexisting with Gd2O3 due to their similar crystal structures. The study also observed internal twins in the Gd grains, potentially delaying the transformation to the stable α-Gd phase. The significant mechanical property differences between the Gd-rich phases and the Ti matrix caused defects at phase interfaces during hot processing, weakening the Gd phase. This work enhances the understanding of Gd phase formation and its implications on the mechanical properties of Ti–Gd alloys.

Keywords: Neutron absorbing material, Gadolinium, Electron backscattered diffraction, Titanium alloy, Focused ion beam, Transmission electron microscopy

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Certain elements, such as B, Gd, and Hf, serve as neutron-absorbing species that can control the capacity of nuclear fission [1]. These elements are included in the control rod material of an operating reactor to govern the operation rate of the reactor or to ensure its emergency shutdown. Neutron absorbers, such as boron-added aluminum alloys or stainless steel, have been used to prevent neutron reactions between adjacent fuel assemblies and maintain the subcritical state of nuclear fuel in structures that store spent nuclear fuel (SNF) [2,3].

Aluminum alloys containing boron are widely used in nuclear fission control [2]; however, most of them exhibit neutron absorption performance without a structural function. Several attempts have been made to manufacture materials with both properties by adding boron to structural steels [4,5] to supplement the structural performance of neutron-absorbing materials. Concerns regarding severe brittleness should be considered when boron is added to iron-based alloys because several intermetallic compounds are inherently formed [[6], [7], [8]]. Boron-added stainless-steel alloys solidify as primary austenite with a terminal eutectic constituent, which forms a typical intermetallic compound (Fe, Cr)2B, with the exact composition dependent on the initial boron level [6]. The matrix in boron-added austenitic stainless steel is a ductile phase, and the dispersed secondary intermetallic phase is a comparatively brittle compound. The mechanical properties deteriorate with the increasing boron content, decreasing the workability of the material. Therefore, a disadvantage of Fe alloys is that only a certain amount of boron can be added. Gd and Hf are highly effective for neutron absorption due to their high neutron capture cross section, good alloying behavior with metals, and excellent thermal stability. However, Hf, despite its advantages, is prohibitively expensive for widespread use in neutron-absorbing materials.

The possibility of developing a neutron-absorbing material with high performance by adding Gd, a robust neutron-absorbing material, to Fe alloys [[9], [10], [11], [12], [13]], Ni alloys [[14], [15], [16], [17]], and Ti alloys [18] has been progressively researched. Adding Gd to stainless steels for neutron absorber applications has attracted attention since the early 2000s [9]. However, application research on austenitic stainless steel-based Gd absorbers was temporarily discontinued owing to the challenges with hot workability. Recently, certain research groups have reinitiated the investigations on Gd by adding stainless steels, such as duplex stainless steel and austenitic stainless steel. They considered that controlling the precipitation behavior of the brittle intermetallic phase can overcome poor hot workability. In addition to Fe-based alloys, a method for improving the mechanical properties of an alloy by adding Gd to Ni-based alloys resulted in the development of an advanced neutron absorber. This alloy has been determined a suitable material for storing SNF in terms of its performance and weldability. Developing a unique alloy system capable of minimizing the formation of an intermediate phase has been considered necessary to develop a neutron-absorbing material with valid structural performance.

This study considers Ti-rich alloy systems as a base matrix material for an advanced high-performance neutron absorber. Since Ti weighs less per volume, it significantly reduces weight when used as a neutron absorber. Alloying in Ti can also adjust various physical properties, which is advantageous for optimizing the material properties for specific applications. Specifically, titanium-iron-chromium alloy is a high-strength, corrosion-resistant material commonly used in aerospace and biomedical applications due to its high strength-to-weight ratio [19]. Adding iron and chromium to titanium increases the strength and hardness of the alloy while improving its corrosion and wear resistance. Another experimental alloy in this study is the β Ti alloy, which exhibits a significantly low modulus and retains a single-phase microstructure on rapid cooling from high temperatures [20].

Based on the information [21] known so far, it is expected that the Gd phase is precipitated inside the Ti matrix, and the Gd-rich phase, which is not a typical intermetallic phase type, is assumed to be a pure Gd phase with hexagonal close-packed (HCP) or body-centered crystal (BCC) structure. However, little basic information exists on the phase change phenomenon caused by adding Gd to Ti alloy. Therefore, this study aims to accumulate the results of electron microscopy analysis of the Gd phase structure in Ti alloys.

We performed simultaneous scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis to characterize the morphology and chemical composition of the phases present in this alloy. A transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with diffraction and chemical composition analyses was also conducted for high spatial resolution microstructure analysis on the thin lamellar sample extracted from the Ti alloys containing Gd. A focused ion beam (FIB) system was primarily used to obtain the qualitative and quantitative microstructural information of various Gd-rich phases. Furthermore, based on the mechanical property information of each phase obtained using the nanohardness measurement method, we attempted to expand the initial research results on Gd-added Ti-based alloys.

2. Experimental

Experimental Ti alloys with a mass of 500 g were fabricated using the plasma arc melting technique based on six trials to reduce impurity level in the initial ingot. This study primarily used the hot-forged alloy designated TiGd01-HF for analytical studies.

The ingot was manufactured as a button-shaped ingot with a diameter of 70 mm and a thickness of approximately 25 mm. Subsequently, it was cut so that the bottom and top surfaces were parallel to facilitate the subsequent forging process. The hot forging process was subjected to be done post-heat treatment at 1150 °C for 2 h to eliminate the solidification of the microstructure. The final forged material was free-forged at a thickness reduction rate of approximately 70 % in a 3000-ton press. The hot forging reduced the thickness of the ingot from 25 to 7 mm and increased the diameter to 120 mm. Consequently, the sample contained alloy elements of Fe, Cr, and Gd ranging from 1.6 to 1.7 wt%, 5.5 to 6.0 wt%, and 4.5 to 6.3 wt%, respectively. Another experimental sample designated as TiGd02-AM was also utilized to confirm the nature of Gd-rich phase in a Gd containing Ti alloy without hot deformation. Information on the chemical composition and post-treatment process of the experimental samples is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the experiment samples prepared from the Ti–Gd alloys.

| (wt%) | Cr | Fe | Mo | Gd | Ti | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiGd01-HF | 5.67 | 1.66 | – | 6.24 | Balance | Hot forming (rolling) at 1150 °C after plasma arc melting (Casting) |

| TiGd02-AM | – | – | 12 | 10 | Balance | After plasma arc melting (Casting) |

Mechanical polishing was performed using SiC papers and diamond suspensions with sizes of 3 and 0.25 μm, respectively. Fine polishing was performed with a colloidal silica suspension of 0.025 μm. The overall mechanical polishing was performed using a semi-auto polisher (Tegarmin-60, Struers, Denmark).

Typical microstructural observations were examined using an SEM module in a FIB system. The Scios2 dual-beam FIB system in the scanning electron beam mode was used for the SEM analysis. To analyze the crystal orientation and chemical element distribution on various microstructures in the alloy, an Oxford Instruments Symmetry EBSD and an UltimMax 65 EDS detector installed on the FEI® Scios2™ dual-beam FIB scanning electron microscope were used. The EBSD analysis was performed to distinguish the developmental microstructure, and the compositional analysis of each phase was simultaneously performed using EDS analysis.

During the preparation of the analytical specimens for electron microscopy, the oxidation of the residual phase on the surface was considered. The residual phase in the vacuum mode of the FIB chamber was analyzed after cross-sectional milling. The analyzed area was not exposed to air after FIB milling.

The matrix phase was primarily analyzed using TEM. Diffraction patterns were obtained for various index poles. We used JEMS software to obtain electron diffraction patterns and high-resolution electron microscopy (HREM) images [22]. The JEM-2100 F TEM by JEOL was used for the analysis. The EDS system from Oxford Instruments was used for the chemical analysis and identification. Phase analysis was performed based on the diffraction patterns, and the compositional changes in the Gd phase were analyzed using EDS. The Thermo-Calc/TiTC3 software was used to identify the stable phase in the alloy [23].

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed to macroscopically analyze the phases of the Gd-containing Ti–Cr–Fe experimental alloy. The XRD analysis equipment was Smartlab by Rikagu, and the analysis was performed at a speed of 2°min−1 using a Cu Kα beam source.

The mechanical properties of each phase were compared using nanoindentation analysis. The FT-NMT04 nanoindenter by Femtotools was used in the FIB for this analysis; the load was approximately 20 mN. The measurements were conducted in the continuous stiffness measurement mode.

3. Results

Fig. 1 depicts the results of the SEM analysis of the TiGd01-HF sample after the final mechanical polishing. Numerous stretched pit marks and bulky particles were observed on the surface, represented by the white and black arrows in Fig. 1(a). Fig. 1(c) and (d) illustrate the enlarged SEM images of the bulky particles in the black dotted box and the elongated pit in the white dotted box (Fig. 1(a)), respectively. The EBSD results in Fig. 1(b) indicate that α-Ti (titanium-HCP) and β-Ti (titanium-BCC) grains were mixed in the matrix. The bulky particles displayed in Fig. 1(a) and (c) were also classified as β-Ti crystal structures.

Fig. 1.

(a) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image exhibiting the surface morphology of the TiGd01-HF sample after fine polishing. (b) Electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD) phase map on the same area indicated in (a). Enlarged SEM images of the (c) black and (d) white dashed boxes depicted in (a).

The EDS analysis results of the surface (Fig. 2) indicate that Gd accumulated on the elongated pits and bulky particles. Additionally, a large amount of oxygen was detected. The coarse Gd-rich particles were analyzed as β-Ti, a BCC phase, which seems to be misinterpreted because appropriate Gd phase information had not been applied during the EBSD analysis. Hence, the occurrence of elongated pits (Fig. 1(d)) implied that certain Gd-rich phases were preferentially polished rather than the matrix being equally polished during the mechanical polishing process, resulting in pit marks. A specific Gd-rich phase (Fig. 1(c)) was cross-sectioned using energetic FIB milling. The EDS and EBSD analyses of the inner region were simultaneously performed to identify the bulky particles, which had been misinterpreted as β-Ti grains. Furthermore, a quantitative EDS analysis with high spatial resolution was realized when the sample was treated as a TEM specimen.

Fig. 2.

Elemental distribution maps of (a) Ti, (b) Cr, (c) Gd, and (d) O elements on the surface of the experimental sample TiGd01-HF.

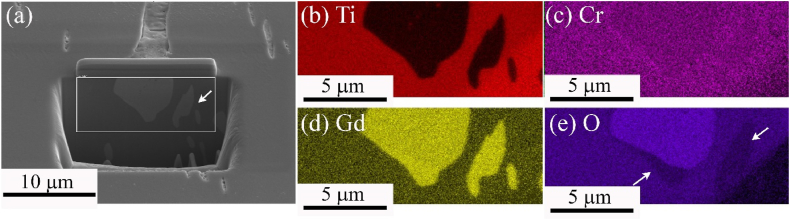

Fig. 3(a) illustrates the SEM image of the Gd-rich phase exposed on the surface after cross-sectional FIB processing. The other Gd-rich phase within the matrix was exposed via cross-sectional processing performed using high-energy Ga ions, as indicated by the white arrow in Fig. 3(a). In this case, EBSD analysis for the crystal structure identification was not applicable because of interference with the surface; therefore, only EDS chemical composition analysis was performed. The EDS composition analysis results of the large Gd phase exposed on the surface differed slightly from the composition analysis results shown in Fig. 2; the difference was that the oxygen element did not exist in the outer region of the particle. The particle inside, indicated by the white arrow in Fig. 3(e), was determined to be a Gd-rich phase with low oxygen content. Conversely, the bulky Gd-rich phase had a high oxygen content. The other type of Gd-rich phase was observed to have an elongated shape with a low oxygen content, as indicated in Fig. 3(e).

Fig. 3.

(a) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image and elemental distribution maps of (b) Ti, (c) Cr, (d) Gd, and (e) O elements near large particles depicted in Fig. 1(c) measured during the cross-sectional analysis performed based on energetic focused ion beam (FIB) milling.

A TEM analysis was performed to comprehensively understand the type of the various phases in the sample. Fig. 4(a) and (b) depict the TEM-EDS map data for each element, which indicates the result of the TEM-EDS analysis measured in the region, including the Gd-rich phase and matrix.

Fig. 4.

(a) Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image and elemental distribution maps of Ti, Cr, Gd, and O elements after the large particle depicted in Fig. 1(c) is subjected to TEM sampling. (b) STEM image and elemental distribution maps of Ti, Cr, Gd, and O elements considering the region within the white box indicated in (a).

The Ti-rich matrix phase region was primarily divided into Cr-enriched and Cr-depleted areas. Additionally, the Cr-depleted grains were interlocked in a needle-like form; the width and length of the Ti grains were approximately 0.1 μm and 1 μm, respectively. The chemical composition results measured in each phase (Table 2) indicated that the solid solubility of Gd in all Ti matrix phases and low solubility of the alloying elements in the needle-shaped Ti alpha grains were nearly absent. Therefore, matrix grains with a high content of alloying elements can be classified as β-Ti grains, which are recognized as a stable phase at high temperatures.

Table 2.

Quantitative chemical composition results of each phase evaluated in Fig. 4 using TEM and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS).

| Ti | Cr | Fe | Gd | O | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Ti | at% | 93.40 | 0.57 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 5.63 | Cr free |

| wt% | 96.46 | 0.65 | 0.24 | 0.67 | 1.99 | ||

| β-Ti | at% | 83.00 | 6.68 | 1.63 | 0.11 | 8.59 | Cr rich |

| wt% | 86.93 | 7.63 | 1.99 | 0.37 | 3.08 | ||

| Gd oxide | at% | 0.72 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 43.05 | 55.97 | Gd, O rich |

| wt% | 0.47 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 87.64 | 11.70 | ||

| Gd | at% | 2.23 | 0.50 | 0.32 | 83.08 | 13.87 | Gd rich (Fig. 4) |

| wt% | 0.79 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 97.22 | 1.66 | ||

| Gd | at% | 4.24 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 83.34 | 11.72 | Gd rich (Fig. 5) |

| wt% | 1.51 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 96.82 | 1.39 | ||

As indicated in the TEM image, the Gd-rich region was divided into a central part, which appeared to be an oxide, and an outer part, where the oxygen content was gradually reduced. The composition ratio was measured to be 56 at% O and 43 at% Gd in the region with high oxygen content. Furthermore, the oxygen content gradually decreased as the distance from the oxide surface increased.

Fig. 5 shows the Gd-rich phase observed below the surface. The oxygen content of the exposed Gd phase during cross-sectioning was measured to be more than ten at%, slightly higher than the value calculated for the Ti matrix based on TEM-EDS analysis (Table 2). Despite the low oxygen solubility in Gd at typical temperatures, it is found that the Gd phase is supersaturated with oxygen. According to the Ti–Gd phase diagram [21], upon cooling after casting, the solidification of Ti begins first, and the Gd-rich liquid phase is pushed to the edge of the Ti solidification phase. At this time, the Gd-rich liquid probably contains relatively high oxygen concentrations. Gd-rich liquid must solidify at low temperatures sequentially and release oxygen to the nearby Ti matrix. Still, rapid cooling is expected to allow relatively high dissolved oxygen within the solidified Gd. In non-equilibrium conditions, such as rapid cooling or quenching, it might be possible to temporarily entrap more oxygen in the Gd lattice than the equilibrium solubility limit allows. When the oxygen concentration exceeds the solubility limit of Gd, the excess oxygen initiates precipitation into Gd oxide (Gd2O3). The oxides precipitate in localized regions of the Gd phase due to the high oxygen dissolution.

Fig. 5.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image indicating the Gd-rich phase observed below the surface depicted in Fig. 3(a).

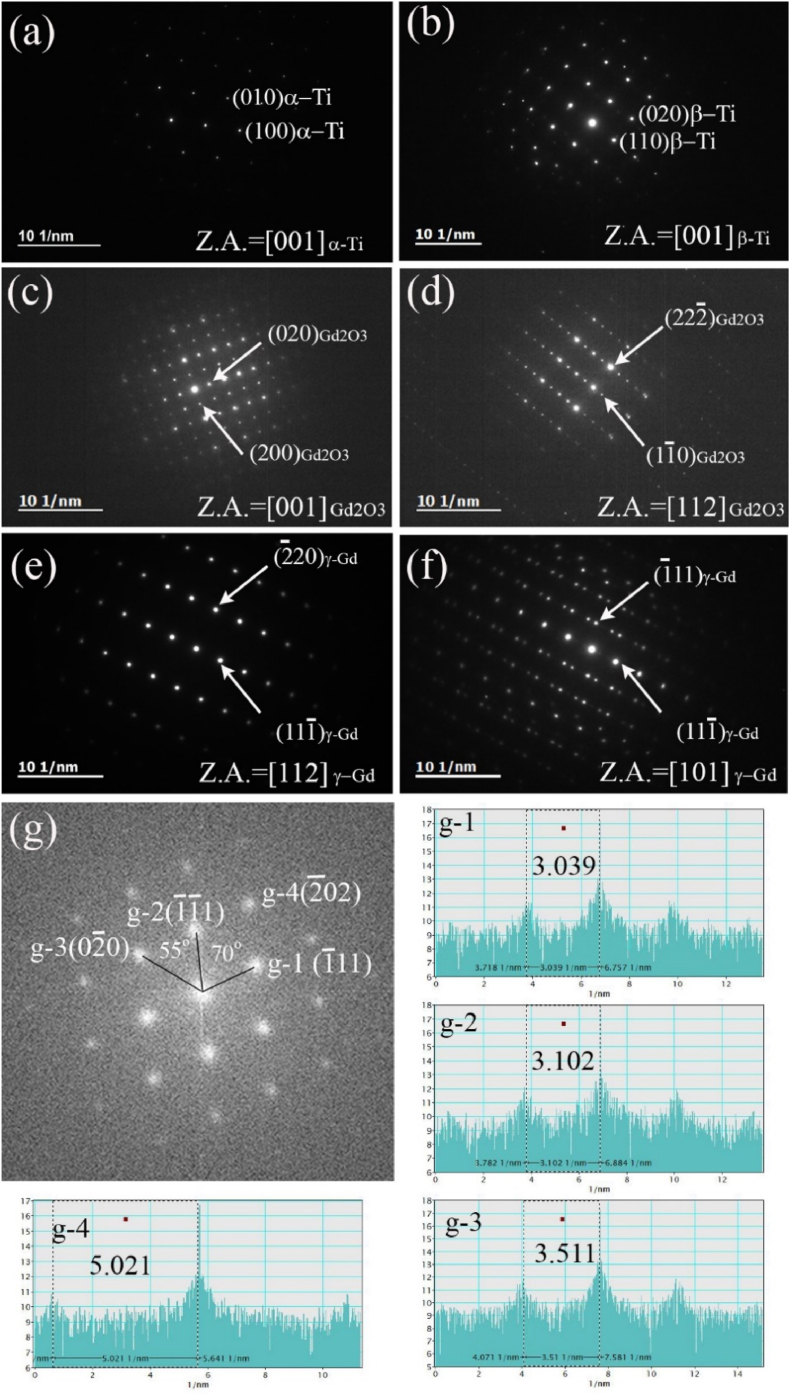

Electron diffraction analysis using TEM was used to identify the residual phases, including Gd and Ti. Fig. 6 illustrates the electron diffraction pattern results for the various phases observed in the experimental sample. The patterns obtained in the matrix region indicated that the Ti matrix comprised two typical phases. These phases comprised the HCP structured α-Ti grains and BCC structured β-Ti grains. The α phase in Ti alloys is the most common Ti-rich phase comprising an HCP crystal structure. In general, the α-Ti phase is a stable form of titanium at room temperature and exhibits adequate strength, ductility, and corrosion resistance. In this study, the lattice parameters were 2.95 Å and 4.68 Å for the a- and c-axis, respectively. The electron diffraction pattern in Fig. 6(a) matches the [0001] zone-axis pattern of the α-Ti particles with an HCP structure. By contrast, the β-Ti phase of titanium alloys has a BCC crystal structure, also referred to as the A2 crystal structure. The β-Ti phase is a high-temperature phase that is stable above the beta-transus temperature, depending on the specific alloy composition. Typically, the values for the lattice parameters are 3.2–3.4 Å; in this study, the value was set to 3.31 Å. The electron diffraction pattern in Fig. 6(b) matches the [001] zone-axis pattern of the β-Ti particles with a BCC structure. According to the Thermo-Calc calculation based on the chemical composition of the Ti alloy (TiGd01-HF), the β-Ti phase was determined to be stable at the forging temperature of 1150 °C. After casting, the experimental sample gradually cooled after hot forging at 1150 °C. According to the Thermo-Calc calculations, the complete transformation temperature at which all β-Ti phases disappear upon cooling is estimated to be nearly 550 °C. The beta-transus temperature for complete transformation from the α+β two-phase to β is also calculated to be approximately 750 °C. It is noted that this temperature is only a thermal equilibrium temperature and does not consider kinetic effects. The beta-transus temperature of the commercial Ti–6Al–4V alloy is approximately within the range of 980 °C–1030 °C. The β-Ti phase of the experimental sample, which was stable at 1150 °C, gradually transformed into the α-Ti phase during cooling but was not wholly converted since the alloying elements Cr and Fe in this sample are considered beta-phase stabilizers. Therefore, slow cooling after the hot-forging process could develop a two-phase complex microstructure containing α-Ti and β-Ti grains. In addition, it is thought that only the beta single-phase structure will be developed when heat-treated above the beta-transus temperature and then quenched.

Fig. 6.

Electron diffraction patterns captured in the (a, b) Ti matrix regions, (c, d) Gd oxide regions, and (e, f) Gd-rich phase regions. (g) Analysis results in terms of electron diffraction patterns obtained via fast Fourier transformation of a high-resolution electron micrograph image indicating the face-centered crystal (FCC) structure of the γ-Gd phase.

The electron diffraction patterns extracted from the Gd oxide region in Fig. 4(a) indicate that the Gd phase was gadolinium oxide (Gd2O3) with a cubic crystal structure and a lattice constant of 10.8 Å. The electron diffraction patterns in Fig. 6(c) and (d) match the [001] and [112] zone-axis patterns of cubic (la-3) Gd2O3, respectively.

Interpreting the diffraction patterns obtained from the Gd-rich region outside the coarse Gd2O3 was challenging. According to the Ti–Gd phase diagram [21], the low oxygen-contained Gd-rich phase was expected to be HCP-structured α-Gd or BCC-structured β-Gd. Typically, the lattice parameters of the α-Gd are 3.6 Å and 5.7 Å for the a- and c-axis, respectively. The lattice parameter of the β-Gd is known to be approximately 4 Å. However, the low oxygen-contained Gd phase was determined to be another Gd phase, which is γ-Gd with a face-centered crystal (FCC) structure and a lattice constant of 5.4 Å; this was half the lattice constant of the oxide obtained through the diffraction pattern analysis results simulated using the JEMS program. The diffraction patterns in Fig. 6(e) and (f) match those measured at the zone axes of the [112] and [110] planes in the γ-Gd phase, respectively. Particularly, the [110] diffraction pattern indicated that the Gd particles exhibited typical twinning characteristics in the FCC structure. According to the electron diffraction pattern obtained by fast Fourier transformation of the high-resolution electron micrograph image of γ-Gd in Fig. 6(g), the g-1 and g-2 spots match the {111} diffraction spots of γ-Gd. The measured reciprocal distance for the g-1 and g-2 spots was approximately 3 [1/nm], consistent with the theoretical value of {111}γ-Gd. The g-3 and g-4 spots were measured to be approximately 3.5 [1/nm] and 5 [1/nm], which were also compatible with the values of {200}γ-Gd and {220}γ-Gd, respectively. However, electron diffraction patterns associated with the α- or β-Gd phase, which was estimated to be stable in Ti–Gd phase alloys, could not be acquired from this experimental specimen.

Additional XRD analysis was performed to overcome the limitation of the small TEM analysis volume. According to the XRD analysis profile results in Fig. 7, the most substantial peaks were analyzed to originate from the dual complex microstructure of α-Ti and β-Ti phases, consistent with the TEM analysis results. The XRD peaks related to the Gd phases corresponded to those of the Gd2O3 and γ-Gd, which was also consistent with the TEM analysis results. If the Gd phase of the HCP structure, considered a stable phase, exists in this experimental sample, the distinctive peak at approximately 32°, originating from the {101} plane of α-Gd, would be observed. However, since it was not observed in the XRD profile, it was determined that α-Gd does not exist in this sample.

Fig. 7.

X-ray diffraction profile of TiGd01-HF sample.

4. Discussion

The experiments revealed that the pure Gd phase of the Ti–Gd alloy exhibited an FCC structure after high-temperature deformation processing or rapid solidification. However, according to the phase diagram [21], the stable phase in Gd is expected to comprise an HCP structure.

Therefore, we considered converting the crystal structure of Gd from HCP to FCC via high-temperature deformation or cooling to ensure the feasibility of forming the FCC γ-Gd phase. The crystal structure change from HCP to FCC by deformation has been reported for other alloy systems [[24], [25], [26], [27]].

In general, the formation of multiple twin interfaces indicates that the Gd phase is exposed to severe deformation during rapid cooling after plasma arc melting and/or following the hot forming process. The γ-Gd phase was expected to be transformed from the initial HCP-Gd phase, which is the stable phase in typical Gd-containing metal-based alloys.

Microstructural analysis was performed on another Ti–Gd alloy after casting without high-temperature treatment to investigate this hypothesis. First, an analysis of TiGd02-AM was conducted to examine the Gd phase structure after casting and subsequent cooling without the hot forming process. The TiGd02-AM is a test alloy in which Gd with 10 wt% is added to a Ti–Mo binary alloy. The results of electron microscopy analysis for the TiGd02 sample cooled after casting are shown in Fig. 8. The matrix was analyzed as β-Ti, and the Gd-rich phase was the γ-Gd, which is the same as the TiGd01-HT sample. The α-Gd phase with HCP structure, considered a stable phase, did not exist. From the SEM EBSD analysis of the Gd-rich phase, as shown in Fig. 8, it is found that the Gd phase formed within the matrix is analyzed as γ-Gd with an FCC structure and that the interior had a high fraction of twin interfaces. This means a stable α-Gd phase does not exist even in the Ti–Gd alloy after casting without hot working. It is also noted that this observation is the same for the TiGdO2 sample after the high-temperature heat treatment at 1200 °C. As for why the stable α-Gd phase with HCP structure characteristic has not been transformed after the high-temperature treatment, it is suspected to be the delay into the stable phase due to the presence of a high-density twin structure. According to the research on other alloy systems [28,29], a twin microstructure plays a vital role in suppressing or delaying phase transformation; as twins are formed, they control the temperature and stress at which phase transformation occurs or increase the internal structure's deformation resistance. A twin structure could suppress phase transformation by forming an energy barrier within the crystal structure. For transformation to a specific phase to occur, the crystal structure must be rearranged; however, the presence of twins makes this rearrangement challenging and is thought to act as a resistance to transformation. Nevertheless, this could be explained when more research data is accumulated.

Fig. 8.

(a) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image showing the surface morphology of TiGd02-AM sample after FIB milling. (b) Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) phase map indicating that the sample is composed of β-Ti and γ-Gd. (c) Coincidence site lattice boundary map revealing the presence of high-density twin boundaries within γ-Gd. (d) EDS map showing Gd composition distribution. (e) HREM image inside the Gd phase. FFT image analysis in the white rectangular box region in (e) reveals the coexistence of Gd2O3 and γ-Gd.

A remarkable feature is the TEM HREM image analysis result in Fig. 8. We confirmed the typical diffraction pattern characteristic of γ-Gd from the FFT interpretation of the HREM image in Fig. 8. Moreover, there is a periodic array with faint spots corresponding to material with significant lattice parameters in the FFT image. This array is similar to the electron pattern constructed by a Gd oxide presumed to be Gd2O3.

This observation means that Gd2O3 oxide coexists in a localized region and reveals the development of the crystal orientation relationship between the two structures. The overall results indicate that the γ-Gd phase (cubic structure with half lattice parameter), similar to Gd2O3 oxide in the view of crystal structure, could initiate as a stable phase, which might be due to the oxygen intake during the high-temperature manufacturing process, such as casting or hot forming. According to the TEM-EDS analysis results summarized in Tables 2 and it can be seen that the oxygen content inside the Gd phase is higher than that of the Ti phases. Thus, oxygen likely plays a specific role in forming and maintaining the γ-Gd phase.

In this work, the Gd-rich phase of the fabricated Ti–Gd alloy was confirmed to comprise γ-Gd and Gd2O3 after casting and hot forging. The EDS analysis results after surface polishing (Fig. 2) led us to erroneously conclude that the Gd phase of the alloy consisted exclusively of Gd-rich oxides. The EDS analysis result, in which a significant amount of oxygen was detected near the Gd-phase region that was partially removed after surface polishing, was considered to be the cause of this misidentification. Oxidation may proceed via exposure to air after surface polishing. Therefore, further analysis was performed using the Ti–Gd experimental sample after FIB treatment to elucidate the possibility of the formation of Gd oxide during air exposure. The as-FIB-milled samples were exposed to air for one month, and the EDS measurements were repeated. We determined that the oxygen content of the exposed Gd phase after FIB treatment was similar to that of the matrix, unlike mechanical polishing using diamond and colloidal silica suspensions. According to the EDS measurements after air exposure, no significant change occurred in the Gd oxygen composition map before and after air exposure. In other words, the possibility of forming Gd oxide owing to air exposure after surface polishing can be eliminated.

Fig. 9 depicts a magnified view of the SEM-EDS results measured within the dotted yellow box area indicated in Fig. 1. A close comparison of the Gd and O chemical composition maps revealed that the area in which O was highly detected was the area lost during the polishing process and the bulk oxide area. However, as indicated by the black arrow (Fig. 9), the unclogged Gd phase region contained low oxygen content. It is clear that the weak region is part of the pure Gd phase rather than Gd oxide.

Fig. 9.

Magnified scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image and the elemental distribution maps of O and Gd near large particles depicted in Fig. 2(a).

Next, we analyzed the reason for the occurrence of preferential erosion of the Gd phase during surface polishing. The diverse behavior of erosion may be closely related to the difference in wear resistance between the Gd phases and Ti matrix. Nanohardness measurements were used to evaluate wear resistance, as it is generally associated with hardness.

Fig. 10(a) depicts the SEM image of the nanohardness measurement area. The nanohardness measurements performed on the Gd phases and matrices are illustrated in Fig. 10(b) and Table 3. In the case of the Gd oxide located at the center of the Gd-rich region, the measured nanohardness was approximately 10 GPa. The mechanical properties of the Ti matrix and γ-Gd phase measured by the nanohardness test were similar. The hardness of the matrix in which α-Ti and β-Ti phases coexisted was estimated to be 5.1 GPa, whereas that of the γ-Gd phase was approximately 4.7 GPa. Although the nanohardness value of the γ-Gd phase was low, a minor difference was detected between this value and the hardness value of the matrix phase. The wear rates of the γ-Gd phase and Ti matrix were expected to be similar owing to their identical hardness values. Therefore, it is unreasonable for the Gd phase to be preferentially removed via selective abrasion during surface polishing. Due to the difference in hardness between the Gd oxide and Gd phases, mechanical processing, such as hot working, can cause stress to concentrate at the interface of the two phases, potentially weakening the phase boundary of Gd.

Fig. 10.

(a) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image after nanoindentation of the surface area including Gd phases. (b) Distribution of the nanohardness values in each phase.

Table 3.

Quantitative nanohardness results of each phase in Fig. 10 measured using nanohardness measurements.

| Nanohardness (GPa) | Number | |

|---|---|---|

| Gd oxide | 18 | |

| γ-Gd | 15 | |

| Ti matrix | 20 |

The TEM images in Fig. 4(a) and (b) indicate that defects, such as numerous voids, exist in the Gd phase and at the boundary between the oxide and matrix. Fig. 11 depicts the high-magnification TEM image of the interface between the Gd-rich and the matrix phases, wherein a sharp cleavage was observed at the interface between the Gd oxide and the Ti matrix. Additionally, several voids were observed along the interfaces (Fig. 11(b)). Numerous defects were observed in the internal structure of the Gd phase owing to severe deformation. Particularly, because dense void defects and sharp cracks existed at and inside the interface, only the Gd phase region appeared to erode preferentially during the mechanical polishing process.

Fig. 11.

(a, b) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images indicating various defects along the interface between the Gd-rich phase and the Ti matrix.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a pioneering investigation into the microstructures formed when the neutron absorber Gd is added to Ti alloys. We obtained comprehensive experimental results based on electron microscopy analysis of Gd-added Ti alloy fabricated by plasma arc melting technique.

The SEM-EBSD/EDS analysis showed that the matrix of Ti–Gd alloy containing Cr and Fe was composed of a unique microstructure with HCP α-phase primarily containing Ti and BCC β-phase with dissolved Cr and Fe after hot forging. The Gd-containing composite phase was composed of round-shaped Gd oxides, while the pure Gd phase was formed in an elongated shape near the oxides or alone. The HREM and XRD analyses indicated that the Gd phase exhibited an FCC structure. In particular, the FCC γ-Gd phase as a potential metastable phase was primarily observed in Ti–Gd alloys. Based on the result of electron microscopy analysis, it is demonstrated that the formation of the γ-Gd phase, which is not recognized as a stable phase, may be due to the effect of oxygen intake into the alloy during fabrication. After hot forming, the γ-Gd phase was fragile, which was believed to be due to the significant differences in mechanical properties between the internal constituents, resulting in the formation of defects near the Gd phase during deformation. The following research will be needed to improve the fragility of the Gd phase by enhancing the manufacturing method or controlling the alloying elements. Future research should focus on improving the fabrication method or controlling the alloying elements to improve the mechanical robustness of the Gd phase.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hyung-Ha Jin: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Sangeun Kim: Investigation. I Seul Ryu: Investigation. Junhyun Kwon: Investigation. Seungmun Jung: Investigation. Young-Bum Chun: Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute R&D program with a contract number of 524480–23 and 524590–24. The authors also thank KARA (KAIST Analysis center for Research Advancement) for their support in conducting the XRD analysis.

References

- 1.Sears V.F. Neutron scattering lengths and cross sections. Neutron News. 1992;3(3):26–37. doi: 10.1080/10448639208218770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Handbook of Neutron Absorber Materials for Spent Nuclear Fuel Transportation and Storage Applications. 2009 Edition. 2009. EPRI, Palo Alto, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen G.M., Carlsen B.W. Idaho National Laboratory Idaho Falls; 2019. Neutron Absorber Considerations for the DOE Standardized Canister. INL/CON-18-52108. Idaho 83415. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soliman S.E., Youchison D.L., Baratta A.J., Balliett T.A. Neutron effects on borated stainless steel. Nucl. Technol. 1991;96(3):346–352. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung M.Y., Baik Y., Choi Y., Sohn D.S. Corrosion and mechanical properties of hot-rolled 0.5%Gd - 0.8%B-stainless steels in a simulated nuclear waste treatment solution (Open Access) Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2019;51(1):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.net.2018.08.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldschmidt H.J. Effect of boron additions to austenitic stainless steels Part II, solubility of boron in 18% Cr, 15% Ni austenitic steel. J. Iron Steel Inst. (London) 1971;209(11):910–912. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin J.W. Proceedings Symposium Waste Management. University of Arizona; AZ: 1989. Effects of processing and microstructure on the mechanical properties of boron-containing austenitic stainless steels; pp. 293–302. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith R.J., Loomis G.W., Deltete C.P. Electric Power Research inst; Palo Alto, CA (United States): 1992. Borate Stainless Steel Application in Spent Fuel Storage Racks, EPRI TR-1000784. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizia R.E., Pinhero P.J., DuPont J.N., Robino C.V., Lister T.E. NACE; Houston, Texas, USA: 2001. Corrosion Performance of a Gadolinium Containing Stainless Steel CORROSION 2001. Paper No. 01138. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahn J.H., Jung H.D., Im J.H., Jung K.H., B.M. Moon Influence of the addition of gadolinium on the microstructure and mechanical properties of duplex stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng., A. 2016;658:255–262. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jang J.H., Kang J.Y., Kim S.-D. Development of GD-containing austenitic stainless steel. J. Nucl. Mater. 2023;574 doi: 10.1016/j.jnucmat.2022.154197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qi Z.-D., Yang Z., Yang X.-G., Wang L.-Y., Li C.-Y., Dai Y. Performance study and optimal design of Gd/316L neutron absorbing material for Spent Nuclear Fuel transportation and storage. Mater. Today Commun. 2023;34 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizia R.E., Michael J.R., Williams D.B., Dupont J.N., Robino C.V. SAND2004-2619J, Sandia National Laboratories (SNL) 2004. Physical and welding metallurgy of Gd-enriched austenitic alloys for spent nuclear fuel applications-Part II: nickel-based alloys”. Albuquerque, NM, and Livermore, CA (United States) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lister T.E., Mizia R.E., Pinhero P.J., Trowbridge T.L., Delezene-Briggs K.B. Studies of the corrosion properties of Ni-Cr-Mo-Gd neutron-absorbing alloys. Corrosion. 2005;61:706–717. doi: 10.5006/1.3278205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mizia R.E., Lister T.E., Pinhero P.J., Trowbridge T.L., Hurt W.L., Robino C.V. Development and testing of an advanced neutron-absorbing gadolinium alloy for spent nuclear fuel storage. Nucl. Technol. 2006;155(2):133–148. doi: 10.13182/NT06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robino C., Mizia R., DuPont J., McConnell P. Nickel-based gadolinium alloy for neutron absorption application in RAM packages. Packag. Transp. Storage Secur. Radioact. Material. 2005;16(1):49–54. doi: 10.1179/174650905775295512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang C., Pan J., Wang Z., Wu Z., Mei Q., Ding Q., Gao J., Xiao X. Gd effect on microstructure and properties of the Modified-690 alloy for function structure integrated thermal neutron shielding. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2023;55(5):1541–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.net.2023.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hur D.H., Jeon S.-H., Han J., Park S.-Y., Chun Y.-B. Effect of gadolinium addition on the corrosion behavior and oxide properties of titanium in boric acid solution at 50 °C. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022;21:3051–3061. doi: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.10.136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho W.F., Pan C.H., Wu S.-C., Hsu H.-C. Mechanical properties and deformation behavior of Ti–5Cr–xFe alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2009;472(1–2):546–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2008.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho W.F., Ju C.P., Chern Lin J.H. Structure and properties of cast binary Ti–Mo alloys. Biomaterials. 1999;20(22):2115–2122. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(99)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okamoto H. Gd-Ti (Gadolinium-Titanium) J. Phase Equilibria Diffus. 2012;33:422. doi: 10.1007/s11669-012-0080-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stadelmann P. Ems – a software package for electron diffraction analysis and HREM image simulation in materials science. Ultramicroscopy. 1987;21:131–145. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thermo-calc software TCTI3/Ti-alloys database version 3. https://thermocalc.com/products/databases/Titanium-andtitanium-and-aluminide-based-alloys

- 24.Hong D.H., Lee T.W., Lim S.H., Kim W.Y., Hwang S.K. Stress-induced hexagonal close-packed to face-centered cubic phase transformation in commercial-purity titanium under cryogenic plane-strain compression. Scripta Mater. 2013;69(5):405–408. doi: 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2013.05.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu H.C., Kumar A., Wang J., Bi X.F., Tomé C.N., Zhang Z., Mao S.X. Rolling-induced face centered cubic titanium in hexagonal close packed titanium at room temperature. Sci. Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep24370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edalati K., Toh S., Arita M., Watanabe M., Horita Z. High-pressure torsion of pure cobalt: hcp-fcc phase transformations and twinning during severe plastic deformation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013;102(18) doi: 10.1063/1.4804273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Z., Li M., Guo D., Shi Y., Zhang X., Schaefer H.-E. Enhancement of TiZr ductility by hcp–fcc martensitic transformation after severe plastic deformation. Mater. Sci. Eng., A. 2014;594:321–323. doi: 10.1016/j.msea.2013.11.085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasan M.M., Srinivasan S.G., Choudhuri D. Transformation- and twinning-induced plasticity in phase-separated bcc Nb-Zr alloys: an atomistic study. J. Mater. Sci. 2024;59:4728–4747. doi: 10.1007/s10853-023-09078-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim H.Y., Ikehara Y., Kim J.I., Hosoda H., Miyazaki S. Martensitic transformation, shape memory effect and superelasticity of Ti–Nb binary alloys. Acta Mater. 2006;54(9):2419–2429. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2006.01.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.