Abstract

Purpose

Evaluation of survival rates for three space maintainers (SMs) of different designs compared to the standard one.

Materials and methods

A total of 52 extraction sites in children aged 4–7 years with prematurely lost primary molars were selected for this study. The whole sample was divided into four groups of 13 each. In group I, Band and Loop (B&L); group II, single-sided Band and Loop (Ss B&L); group III, Direct Bonded Wire (DBW); and group IV, Tube and Loop (T&L). Children were recalled at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 months. Cumulative survival rates of SMs were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method with a logrank test.

Results

Although there was a nonsignificant difference in the number of failed cases among all groups, the overall survival rate for group I was 69.2%, group II was 53.8%, group III was 38.5%, and group IV was 30.8% at the end of the study. The failure types for B&L were solder breakage (75% of the total failure rate) and cement dissolution (25%); for Ss B&L, they were solder breakage with lost loop (50%), soft tissue impingement (33%), and dislodgment (17%); for DBW, they were composite-wire interface debonding (75%) and enamel-composite interface debonding (25%); and finally, for T&L, they were lost T&L (56%), soft tissue impingement (22%), and total loss (22%).

Conclusion

Banded SMs survived for a longer time than bonded ones, with superior performance for B&L compared to Ss B&L. In addition, bonded SMs required strict isolation conditions. DBW could be used in the maxilla rather than the mandible and was preferable for older children.

How to cite this article

Hemdan ME, H El Kalla IHH, El Agamy RA. Clinical Evaluation of Different Designs of Fixed Space Maintainer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent 2024;17(4):442-450.

Keywords: Band and Loop, Fixed space maintainer, Space maintainer, Tube and Loop

Introduction

The stage of primary dentition development is a crucial element in the child's growth process. It plays various roles in mastication, speech maintenance, guiding the eruption of permanent teeth, appearance, and prevention of unfavorable oral habits.1

This process may be disrupted because of the premature loss of one or more deciduous teeth. Loss of arch length may occur because of the migration of adjacent teeth. Clinically, arch length loss further develops malocclusion in mixed or permanent dentition in terms of crowding, permanent teeth impaction or rotation, and supraeruption of opposing teeth.

To maintain the integrity of the arch, numerous types of space maintainers (SMs) have been designed.2,3 The most popular fixed space maintainer to date is the Band and Loop (B&L) space maintainer. Although it is simple to build, affordable and requires less chairside time, it has many limitations. These include the need for a minimum of two visits, the requirement for an alginate impression, the risk of plaque accumulation causing gingival inflammation and early carious lesions, and the need for significant laboratory work and time during fabrication,4 and the possibility of metal allergies. These limitations pose a challenge for clinicians when using this method.4–6

The first published clinical guidelines on the extraction of primary teeth and the use of SMs by the Clinical Effectiveness Committee of the Faculty of Dental Surgery of the Royal College of Surgeons of England [RCS (England)] were in 2001 and updated in 2006. The decisions to use SMs should be guided by balancing the occlusal disturbance that may result if they are not used against the potential plaque accumulation and caries that the appliance may cause.7

According to inclusion criteria determined in a review8 to assess the evidence related to SMs, Ovid Medline, Medline, and a hand-search of nonlisted peer-reviewed papers were scanned to retrieve a total of 16 relevant papers (published between 1987 and 2007). It was concluded that limited evidence was found to recommend either for or against the usage of SMs to prevent or reduce the degree of malocclusion in permanent dentition.

A review was conducted by Achmad et al.,9 from electronic databases, including PubMed, Elsevier, and Google Scholar, aimed to retrieve articles concerning space maintainers. Eligibility criteria considered articles in the English language published between 2013 and 2020, encompassing all study designs and publication types. After screening 50 articles, only 15 full-text articles met the eligibility criteria regarding the use of space maintainers in pediatric dentistry. The review recommends that space maintainers are necessary for preserving the space left after primary teeth extraction.

Simsek et al.10 in 2004 evaluated the clinical performance of a simple fixed space maintainer, which consisted of a rectangular stainless-steel wire bonded with flowable composite (tetric flow) placed on the primary canine and second primary molar. The study followed up on these maintainers for 12–18 months, assessing survival rate, their ability to prevent space loss, and whether there was any damage to the abutment teeth. At the end of the study, 5% of the appliances were deemed unsuccessful. During this period, the loss of space among the abutment teeth was found to be statistically insignificant. The study concluded that operator experience and proper case selection were the main determinants of successful simple fixed space maintainers.

Ramakrishnan et al.11 conducted a review aimed at assessing evidence concerning the survival rate of fixed space maintainers (SMs). An online search was conducted up to October 2017 using PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane databases with keywords ”primary dentition” and ”fixed SMs.” Clinical studies involving children younger than 12 who required a unilateral or bilateral fixed space maintainer met the inclusion criteria. Out of 39 retrieved studies, 23 papers did not satisfy the inclusion criteria, leaving 16 articles for review. Ultimately, 11 papers were selected and systematically reviewed. Most of the clinical trials were assessed as having moderate and low risk of bias. The review concluded that there was inadequate evidence and wide variation in the survival rate of metal-based and resin-based space maintainers, as well as variability within the metal-based space maintainers themselves.

The design of conventional B&L was modified into tube and loop (T&L) “Nikhil Appliance” in a case report, 2016.12 The abutments bounding the edentulous area were banded, and a tube was spot-welded at the buccal aspect of each band. Using a 0.032-inch (21-gauge) stainless steel (SS) wire, a “V”-shaped loop with a midway helix was formed at an angle of 30–45°. Subsequently, the prepared loop was inserted into the buccal tubes after trimming the wire to fit precisely between both tubes. This design eliminated the need to take impressions and do laboratory work. The simplicity of this appliance allows the clinician to easily rotate the loop for routine cleaning underneath, activate the coil, uncoil the helix, or even remove the loop if necessary without disturbing the bands. However, further studies are still required to evaluate this appliance better.

Materials And Methods

This randomized controlled clinical trial was conducted on 52 extraction sites of first primary molars in children aged 4–8 years who visited the pediatric department of Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt.

The research protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Research, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt (Code No: A27080120). Parental consent was obtained from all participants after providing detailed information about the study. The study adhered to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 guidelines (Fig. 1).13 It was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov PRS (ID: NCT05693870).

Fig. 1:

Participant CONSORT statement flow diagram

Sample Size

The total sample size was calculated using the SampSize application with an anticipated success rate of 86% for treatment with conventional Band and Loop (B&L),14 anticipated response rate for treatment with SS direct bonded wire (DBW) was 33%,15 at 80% power, and significant level 0.05.

Patient Selection

The children were selected from the dental clinic of the Faculty of Dentistry, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt, with an allocation ratio of 1:1 using block randomization. A total of 52 extraction sites of the first primary molar were selected according to the following inclusion criteria:

Inclusion Criteria

The children should have a freshly extracted first primary molar with the presence of the primary canine and second primary molar on the mesial and distal sides of the extraction site.

The children have Angle's class I occlusion without any para-functional habits or abnormal occlusion conditions such as crossbite, open bite, or deep bite.

Children should be free from any systemic disease.

Children and their parents should have a high degree of cooperation and compliance.

Presence of permanent successor with no evidence of any pathological lesion.

Clinical Procedures

All children received complete oral prophylaxis and any necessary restorative procedures for the abutments before the start of the study. Restorative procedures ranged from class I to II cavity preparations to pulp therapy and/or stainless steel crowns as extracoronal restorations. Oral hygiene instructions were carefully taught to both parents and children.

Only the buccal surface of abutments that received bonded space maintainers should be free from any restoration or caries.

A total of 52 extraction sites of the first primary molar were randomly allocated into four groups, with 13 sites in each group:

Group I: Conventional B&L.

Group II: Single-sided B&L (Ss B&L).

Group III: Stainless steel DBW.

Group IV: T&L.

Clinical Procedures of Conventional Band and Loop (Group I)

Fabrication of conventional B&L was done using the standard clinical procedure given by Graber16 and Finn.17 A ready-made, tubeless, plain band of estimated size was selected from a kit and tried to ensure proper fit around the second primary molar. A trial-and-error method was used during band selection. The occlusal border of the band was pushed against the abutment using a band pusher to achieve a snug fit. After seating the band on the abutment, an overall pickup alginate impression was taken for the working side.

The band was then transferred to its exact position in the impression and secured with pink wax before pouring the cast. Subsequently, a loop was fabricated from a 0.7 mm SS wire and adapted to extend from the buccal surface of the band to passively touch the distal surface of the primary canine, then return to the lingual surface of the band, where it was secured with plaster. The loop was soldered using Nobel-Metal LV 15 solder with incorporated flux at both the buccal and lingual sites of the band. After finishing and polishing, the appliance was cemented with glass ionomer luting cement.

Clinical Procedures of Single-sided Band and Loop (Group II)

The construction of this appliance closely resembled the conventional Band and Loop (B&L) method. It involved selecting a suitable band for the second primary molar, followed by taking an alginate impression, transferring the band into the impression, and cementing it in place before pouring the cast.

This design differed in the shape of the loop itself—the free end of the loop started from the distolingual line-angle of the primary canine and wrapped around the distal surface of the canine, covering the distal third of the labial surface (resembling the letter ”C”). The loop then turned back distally, crossing the extraction site on its buccal side, and ended at the buccal surface of the band on the second primary molar, where it was soldered.18 Finally, the appliance was cemented with glass ionomer luting cement (Kromoglass 3, LASCOD S.p.A., Via L. Longo, Italy).

Clinical Procedures of Direct Bonded Wire (Group III)

A stainless steel (st-st) rounded 0.018-gauge wire was bent and adjusted intraorally to be at least 1 mm away from the gingiva and extending along the buccal surface of each abutment. A shallow ”U” shaped loop was created as an adjunct aid to enhance the tooth-wire bonding interface. After initial fixation of the wire, a self-etch adhesive (Single Bond Universal Adhesive, 3M™) was applied, and the entire wire-to-tooth interface was incrementally covered with packable composite (Filtek Z350 XT, 3M ESPE) and light cured (Monitex BlueLEX LD-10, Taiwan).

Clinical Procedures of Tube and Loop (Group IV)

A rubber dam was applied, and an orthodontic tube and canine bracket were selected to be bonded on the buccal surface of the lower second primary molar and canine, respectively, using the same adhesive and composite type used in group III. The tube was positioned slightly gingival to the middle area of the buccal surface to minimize occlusal stress. A loop was constructed from orthodontic stainless steel wire. A “V”-shaped bend was made intraorally at an angle of 30–45° with the occlusal plane, followed by a coil bend at nearly the midway point between the tube and bracket. The prepared loop was then inserted passively into the slot of the buccal tube and bracket after trimming the wire to the exact distance. Finally, the loop was secured to the bracket with ligature wire and an O-tie to ensure relative long-term loop stability.

Ability of SMs to Prevent the Loss of Space

The ability of SMs to preserve space during this study was assessed by evaluating the linear relationship between the two abutment teeth using a modified method based on Swaine and Wright's approach.14,15 The measurements were calculated on initial study models before and at the end of the study.

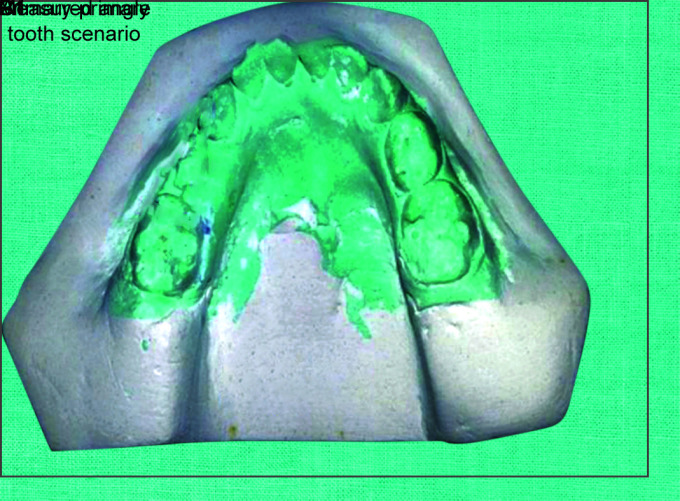

Modified Swaine and Wright Method of Calculation

In the absence of the first primary molar, the mesiobuccal and mesiolingual cusp tips of the second primary molar, and the cusp tip of the primary canine formed three points. These points were joined to form a triangle with corresponding sides labeled A1, B1, and C1 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2:

Modified Swaine and Wright method of calculation

The line connecting the mesiobuccal and mesiolingual cusp tips of the second primary molar constituted the base side (A1) of the triangle. The line connecting the mesiobuccal cusp tip of the second primary molar and the cusp tip of the canine formed the second side (B1) of the triangle.

The line connecting the mesiolingual cusp tip of the second primary molar and the cusp tip of the canine formed the third side (C1) of the triangle. Measurements recorded under these criteria were applied in a square root formula:

Thus, linear changes were obtained (Fig. 2).

Statistical Analysis and Data Interpretation

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, United States of America), with the significance level (p-value) set at 0.05.

Results

Each appliance had a separate chart in an Excel sheet with 13 rows representing 13 appliances. Follow-up occurred every 3 months until either failure occurred, which was recorded with the cause of failure and the total survival time in weeks, or the appliance was censored at the final follow-up at 15 months. In case of failure, appliance repair was performed until the end of the study.

Cumulative survival rates of space maintainers (SMs) were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method (Tables 1 and 2). Survival rates were also compared among each group using the logrank test, which showed a nonsignificant difference (p = 0.357) (Table 3). Medians for survival times were estimated by recording the lower and upper bounds for each group (Table 4). Study covariates such as age and sex were analyzed using the Cox regression test.

Table 1:

Kaplan–Meier detailed analysis

| Group | No. | Status F = failed | Cumulative proportion survived at the time | Time per week | Number of remaining cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate ± standard deviation (SD) | |||||

| Group I | 1 | F | 0.923 ± 0.074 | 21 | 12 |

| 2 | F | 0.846 ± 0.1 | 25 | 11 | |

| 3 | F | 0.769 ± 0.117 | 37 | 10 | |

| 4 | F | 0.692 ± 0.128 | 38 | 9 | |

| Group II | 1 | F | 0.923 ± 0.074 | 21 | 12 |

| 2 | F | 0.846 ± 0.1 | 27 | 11 | |

| 3 | F | 0.769 ± 0.117 | 34 | 10 | |

| 4 | F | 0.692 ± 0.128 | 37 | 9 | |

| 5 | F | 0.615 ± 0.135 | 40 | 8 | |

| 6 | F | 0.538 ± 0.138 | 52 | 7 | |

| Group III | 1 | F | 0.923 ± 0.074 | 12 | 12 |

| 2 | F | 0.846 ± 0.1 | 12 | 11 | |

| 3 | F | 0.769 ± 0.117 | 26 | 10 | |

| 4 | F | 0.692 ± 0.128 | 28 | 9 | |

| 5 | F | 0.615 ± 0.135 | 32 | 8 | |

| 6 | F | 0.538 ± 0.138 | 38 | 7 | |

| 7 | F | 0.462 ± 0.138 | 38 | 6 | |

| 8 | F | 0.385 ± 0.135 | 38 | 5 | |

| Group IV | 1 | F | 0.923 ± 0.074 | 12 | 12 |

| 2 | F | 0.846 ± 0.1 | 12 | 11 | |

| 3 | F | 0.769 ± 0.117 | 17 | 10 | |

| 4 | F | 0.692 ± 0.128 | 21 | 9 | |

| 5 | F | 0.615 ± 0.135 | 25 | 8 | |

| 6 | F | 0.538 ± 0.138 | 32 | 7 | |

| 7 | F | 0.462 ± 0.138 | 38 | 6 | |

| 8 | F | 0.385 ± 0.135 | 38 | 5 | |

| 9 | F | 0.308 ± 0.128 | 52 | 4 | |

Table 2:

Kaplan–Meier (case processing summary)

| Groups | Total N | N of failures | N | Success rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | 13 | 4 | 9 | 69.2% |

| Group II | 13 | 6 | 7 | 53.8% |

| Group III | 13 | 8 | 5 | 38.5% |

| Group IV | 13 | 9 | 4 | 30.8% |

Table 3:

Test of equality of survival distributions for the different levels of groups

| Chi-square | Df | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logrank (Mantel–Cox) | 3.237 | 3 | 0.357 |

Df, Difference; Sig., significance

Table 4:

Median survival time for each

| Groups | Median | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (by weeks) | SD | 95% confidence level | ||

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||

| Group I (B&L) | 53.42 | 5.451 | 43.49 | 63 |

| Group II (Ss B&L) | 51.23 | 4.521 | 42.37 | 60.09 |

| Group III (DBW) | 41.23 | 5.681 | 31 | 51.47 |

| Group IV (T&L) | 35.92 | 5.645 | 26.29 | 45.56 |

Conventional Band and Loop Result (Group I)

Out of the 13 space maintainers (SMs), nine appliances were censored by the end of the 15-month follow-up period. The success rate achieved was 69.2% (Table 2). The first failure occurred at the 6-month follow-up visit, primarily due to cement dissolution. Three of the failed appliances experienced solder breakage on one side with or without loop distortion, accounting for 75% of the total failure types. One appliance failed due to a combination of cement dissolution and dislodgment (Fig. 3). Median survival time for this group was 53.42 weeks (Table 4).

Fig. 3:

Pie chart demonstrating failure types percentage for group I (B&L)

Single-sided Band and Loop Result (Group II)

Out of the 13 space maintainers (SMs), only seven appliances were censored by the end of the 15-month follow-up period (Fig. 4). Success rate scored was 53.8% (Table 2). The first failure occurred at approximately 21 weeks due to solder breakage. Two appliances failed due to solder breakage and a lost loop, and another appliance failed due to loop fracture immediately after the solder joint, reportedly by the child (Fig. 5); one appliance failed due to a combination of cement dissolution and dislodgment. Two appliances caused severe gingival traumatization and ulceration due to loop-soft tissue impingement (Figs 5 and 6). The median survival time for this group was 51.23 weeks (Table 4).

Fig. 4:

Censored Ss B&L

Figs 5A and B:

(A) Loop fracture in Ss B&L by the child himself; (B) Soft tissue impingement from the loop of Ss B&L

Fig. 6:

Pie chart demonstrating failure types percentage for group II (single-sided band)

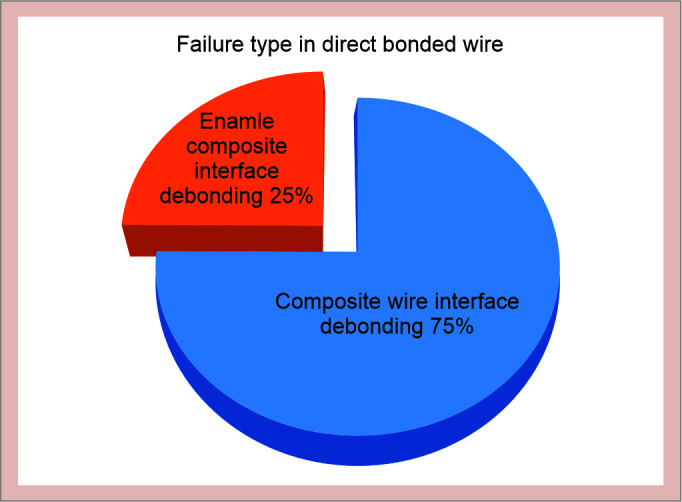

Direct Bonded Wire Result (Group III)

Out of the 13 space maintainers (six in the mandible and seven in the maxilla), only five appliances were censored by the end of the 15-month follow-up period (Fig. 7). Success rate scored was 38.5% (Table 2). There were a total of eight failures (five in the mandible and three in the maxilla), with the first two failures occurring at approximately 12 weeks (at the 3-month follow-up visit) due to enamel-composite interface debonding. This type of failure was recorded in only two cases, accounting for 25% of the failures, while the majority of failures (six appliances) were due to composite-wire interface debonding, totaling 75% (Figs 8 and 9). The median survival time for this group was 41.23 weeks (Table 4).

Figs 7A and B:

Censored DBW in the maxilla; (A) After bonding; (B) After 15 months and successor eruption

Fig. 8:

Direct bonded wire in mandible after 12 months and successor eruption (note wire composite interface debonding)

Fig. 9:

Pie chart demonstrating failure types percentage for group III (DBW)

Tube and Loop Result (Group IV)

Out of the 13 space maintainers (SMs), only four appliances were censored by the end of the 15-month follow-up period (Fig. 10). Success rate scored was 30.8% (Table 2). The first failure occurred at approximately 12 weeks with a lost loop. Two appliances failed due to severe gingival traumatization and ulceration resulting from loop-soft tissue impingement (Fig. 11). Seven appliances failed due to either the loss of one component (Loop or Tube) or the total loss of the whole appliance, which represented 77.8% of the total failure types (Fig. 12). Median survival time for this group was 35.92 weeks (Table 4).

Figs 10A and B:

Censored T&L; (A) After cementation; (B) 6-month follow-up

Figs 11A and B:

Tube and Loop; (A) T&L just after cementation; (B) Gingival ulceration due to loop impingement after 3 months

Fig. 12:

Pie chart demonstrating failure types percentage for group IV (T&L)

Ability of SMs to Prevent the Loss of Space Result

There was no significant difference observed within each group when comparing pre- and poststudy linear measurements, indicating sustained space maintaining efficacy for all space maintainer designs in this study (Table 5).

Table 5:

Comparing pre- and poststudy linear measurements difference per each group

| Group I n = 13 (%) | Group II n = 13 (%) | Group III n = 13 (%) | Group IV n = 13 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | 119.77 ± 25.49 | 143.88 ± 39.92 | 162.89 ± 50.34 | 123.21 ± 24.49 |

| Post | 119.48 ± 25.50 | 142.52 ± 38.88 | 162.56 ± 50.11 | 122.85 ± 24.39 |

| Paired t-test |

t = 1.08 p = 0.304 |

t = 2.01 p = 0.07 |

t = 1.94 p = 0.07 |

t = 2.09 p = 0.06 |

p ≥ 0.05 is not significant at a confidence level of 95%; n, number; t, paired t-test

Study Covariates Analysis

After matching for age and sex at the start of the study (mean age p-value = 0.754, mean sex p-value = 0.06) (Table 6), there was no significant difference regarding jaw (p = 0.461) and sex (p = 0.183). However, there was a significant difference (p < 0.001) in survival rate between children older than 6 years (59.55 weeks) and those younger (33.73 weeks), indicating that appliances survived longer in older children (Table 7).

Table 6:

Matching covariates (age, sex) between all groups at the start of the study

| Group I | Group II | Group III | Group IV | Comparison between studied groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/years mean ± SD | 6.15 ± 0.519 | 6.0 ± 1.08 | 6.31 ± 0.75 | 5.92 ± 0.95 |

F = 0.40 p = 0.754 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 3 (23.1) | 9 (69.2) | 3 (23.1) | 5 (38.5) | MC = 7.8 p = 0.06 |

| Female | 10 (76.9) | 4 (30.8) | 10 (76.9) | 8 (61.5) | |

Table 7:

Effect of study covariates (age, sex, jaw) on median overall survival time

| Median overall survival time per week (95% CI) | Logrank χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age/years | |||

| <6 years | 33.73 (28.05–39.42) | 23.68 | <0.001* |

| ≥6 years | 59.55 (54.47–64.62) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 48.95 (40.68–57.22) | 1.77 | 0.183 |

| Female | 41.96 (35.38–48.56) | ||

| Upper jaw | 43.67 (38.02–49.33) | 0.544 | 0.461 |

| Lower jaw | 52.17 (40.49–63.85) | ||

| Group I | 53.42 (43.84–63) | 6.44 | 0.092 |

| Group II | 51.23 (42.37–60.09) | ||

| Group III | 41.23 (31–51.47) | ||

| Group IV | 35.92 (26.29–45.56) | ||

*, p-value < 0.05 (significant difference)

Discussion

Early loss of primary teeth disrupts the natural cycle of exfoliation and subsequent eruption of permanent teeth. This disruption can lead to malocclusion as a final outcome.19 As a result, various types of SMs have been developed, and clinicians choose the model that best suits each patient based on the circumstances. The B&L design has been the most popular fixed space maintainer up to the present time8,9 since it has a high success rate.20–22

However, this design has been found to have drawbacks such as cement dissolution, tipping and/or rotation of abutment and neighboring teeth, loop gingival impingement, the need for impressions, increased laboratory and chairside time, and requiring two visits.23

As the marker dot placement on the wire was done intraorally rather than on a study model, the T&L appliance necessitated a cooperative child to effectively allow field isolation and comfortable wire bending to form the loop with its midway coil.

Rubber dam isolation was crucial to ensure dry field conditions that would enhance retention quality. However, in both directly bonded groups III and IV, checking for occlusal interferences was challenging due to the presence of a rubber dam clamp, which prevented proper occlusion of the teeth. After removing the rubber dam, any occlusal interferences were examined.

In this study, the outer prismless enamel layer on abutments was not removed. Instead, a lengthy etching process lasting up to 40 seconds was conducted before bonding. Therefore, further research is needed to investigate methods for enhancing bonding to primary dentition enamel, potentially through prebonding removal of the prismless zone.

In group III (DBW), appliances bonded to the functional buccal surface of the lower jaw were more prone to debonding failures compared to those bonded to the nonfunctional buccal surface of the upper jaw. This susceptibility was exacerbated by the limited surface area available for bonding, especially in cases with deep bites. Despite this, there was no significant difference in success rates between the upper and lower jaw locations in the direct-bonded wire group, which may be attributed to the relatively small size of each group.

Although the bonded groups (groups III and IV) required only a single visit compared to the banded groups (groups I and II), which necessitated a minimum of two visits, the time per visit was significantly longer in the bonded groups. This increased time demand often required a more cooperative child during the procedure.

In the T&L appliance design, a molar tube was utilized instead of a band, as described in the Nikhil appliance,14 to simplify and shorten the clinical procedure. Additionally, bonding a tube is generally less cumbersome for children compared to the process of selecting and seating bands. However, properly-sized cemented bands may exhibit greater resistance to dislodgement compared to bonded tubes.

Although Ss B&L is simpler in design compared to conventional B&L, the free end of the loop makes the appliance more susceptible to damage caused by the child. This vulnerability often results from repeated attempts by the child to dislodge the appliance, leading to solder breakage or loop fracture just after the soldered area. Such failures were recorded, even when the loop was constructed from 0.9-gauge wire.

After Kaplan–Meier analysis, group I showed the highest survival rate (69.2%), followed by group II (53.8%), group III (38.5%), and group IV (30.8%), respectively. Although the logrank test showed a nonsignificant value (0.357) and the Chi-squared test for the number of failed cases was not significant (p = 0.514), these results could be attributed to the relatively small sample sizes in each group. Therefore, further studies with larger sample sizes may be beneficial in this context to provide more conclusive findings.

Conventional B&L or crown and loop SMs were frequently used in premature loss of posterior primary teeth with such failure occurrence average at 12.5–14 months in addition to a failure rate of 10 and 11%, respectively, as reported by Baroni et al.21 In this study, B&L survival rate result (69.2%) was found to be relatively close to Setia et al.24 results (73.3%) after 9 months follow-up period and 15 appliances total group number.

In the Güleç study,25 Ez-space maintainers, which employs a similar concept of direct bonding metal to enamel using composite, experienced six failures compared to five failures observed in the T&L group during the 6-month appointment in this study. By the 12-month visit, both designs recorded an additional four failed appliances.

It was obvious that the design of group IV “T&L” was inspired by Nikhil's appliance in his case report14 with some modifications as replacement of bands used by Nikhil, with a direct-bonded tube on the second primary molar and bracket on the primary canine. Keeping in mind the relatively short period (8 months) in his report till successful “uneventfully,” as he put it, successor eruption and thus recommending routine use of his appliance, on the contrary, group IV in this study recorded the worst survival performance (30.8%) and the majority of failures were due to lost tube (56%). Thus, future studies may be meaningful in prolonging the life of this appliance by replacing tubes with bands.

After analyzing the study covariates (age, sex, and jaw), no significant differences were found in relation to jaw and sex. However, there was a significant difference in the median overall survival time between children older than 6 years (59.55 weeks) and those younger than 6 years (33.73 weeks). This could be attributed to older children being more mature and capable of maintaining their space maintainers without as much interference compared to younger children (Tables 6 and 7). On the level of pre- and postlinear measurement changes between primary canine cusp tip and second molar mesial cusps, there were nonsignificant differences in all study groups, proving the space-maintaining ability for all designs in this study (Table 5).

Conclusion

Banded SMs demonstrated longer survival without issues compared to bonded SMs, with conventional B&L showing superior performance over single-sided designs. Bonded SMs required strict isolation conditions and were preferably used in the maxilla compared to the mandible, particularly in children older than 6 years.

Why is this Paper Important to Pediatric Dentists?

Space maintainer designs like DBW in group III and T&L in group IV can be constructed in a single chairside visit, making them suitable options for children undergoing treatment under general anesthesia.

Elimination of laboratory and impression-taking procedures, especially with children having severe gag reflexes.

Space maintainer designs in group II (Ss B&L) are simpler compared to conventional B&L designs to the extent that they allow for the eruption of succedaneous teeth without interference from the loop.

Ethical Approval

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Research at Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt, with approval code A27080120.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Dr Ahmed ElSebaai (Lecturer of Pediatric Dentistry at Delta University, Egypt) for his help in the study.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.Barbería E, Lucavechi T, Cárdenas D, et al. Free-end space maintainers: design, utilization and advantages. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2006;31(1):5–8. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.31.1.p87112173240x80m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirzioglu Z, Ozay MSZ, Ozay MS. Success of reinforced fiber material space maintainers. J Dent Child. 2004;71(2):158–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright CZ, Kennedy DB. Space control in the primary and mixed dentitions. Dent Clin North Am. 1978;22:579–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quadeimat MA, Fayle SA. The longevity of space maintainers: a retrospective study. Pediatr Dent. 1998;20(4):267–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nayak UA, Loius J, Sajeev R, et al. Band and loop space maintainer—made easy. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2004;22:134–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caroll TP. Prevention of gingival submergence of fixed unilateral space maintainers. J Dent Child. 1982;49:48–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Clinical Effectiveness Committee of The Faculty of Dental Surgery of The Royal College of Surgeons of England Extraction of Primary Teeth—Balance and Compensation. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laing E, Ashley P, Naini FB, et al. Space maintenance. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2009;19(3):155–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2008.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Achmad H, Taya The use of space maintainer in pediatric dentistry: a systematic review. European J Mol Clin Med. 2021;8(2):1532–1545. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simsek R, Yilmaz Y, Gurbuz T. Clinical evaluation of simple fixed space maintainers bonded with flow composite resin. J Dent Child. 2004;71:163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramakrishnan M, Dhanalakshmi R, Subramanian EMG. Survival rate of different fixed posterior space maintainers used in paediatric dentistry—A systematic review. Saudi Dent J. 2019;31(2):165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2019.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srivastava N, Grover J, Panthri P. Space maintenance with an innovative “tube and loop” space maintainer (Nikhil Appliance) Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2016;9(1):86–89. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CONSORT 2010. Lancet. 2010;375(9721):1136. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60456-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mittal S, Sharma A, Sharma AK, et al. Banded versus single–sided bonded space maintainers: a comparative study. Indian J Dent Sci. 2018;10:29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swaine TJ, Wright GZ. Direct bonding applied to space maintenance. ASDC J Dent Child. 1976;43(6):401–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graber TM. Orthodontics: Principles and Practice. 3rd edition. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1992. p. 572. p. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finn SB. Clinical Pedodontics. 4th edition. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1998. p. 354. p. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moses J, Sekar PK, Raj SS, et al. Modified band and loop space maintainer: Mayne's space maintainer. Int J Pedod Rehabil. 2018;3:84–86. doi: 10.4103/ijpr.ijpr_4_18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao AK, Sarkar S. Changes in the arch length following premature loss of deciduous molars. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 1999;17(1):29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fathian M, Kennedy DB, Nouri MR. Laboratory-made space maintainers: a 7-year retrospective study from private pediatric dental practice. Pediatr Dent. 2007;29(6):500–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baroni C, Franchini A, Rimondini L. Survival of different types of space maintainers. Pediatr Dent. 1993;16:360–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajab LD. Clinical performance and survival of space maintainers: evaluation over a period of 5 years. ASDC J Dent Child. 2002;69(2):156–160, 124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subramaniam P, Babu GKL, Sunny R. Glass fiber-reinforced composite resin as a space maintainer: a clinical study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2008;26(Suppl 3):S98–S103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Setia V, Pandit IK, Srivastava N, et al. Banded vs bonded space maintainers: finding better way out. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2014;7(2):97–104. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Güleç S, Doğan MC, Seydaoğlu G. Clinical evaluation of a new bonded space maintainer. J Clin Orthod. 2014;48(12):784–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]