Abstract

Background

Central neuropathic pain after foramen magnum decompression (FMD) for Chiari malformation type 1 (CM-1) with syringomyelia can be residual and refractory. Here we present a case of refractory central neuropathic pain after FMD in a CM-1 patient with syringomyelia who achieved improvements in pain following spinal cord stimulation (SCS) using fast-acting sub-perception therapy (FAST™).

Case presentation

A 76-year-old woman presented with a history of several years of bilateral upper extremity and chest-back pain. CM-1 and syringomyelia were diagnosed. The pain proved drug resistant, so FMD was performed for pain relief. After FMD, magnetic resonance imaging showed shrinkage of the syrinx. Pain was relieved, but bilateral finger, upper arm and thoracic back pain flared-up 10 months later. Due to pharmacotherapy resistance, SCS was planned for the purpose of improving pain. A percutaneous trial of SCS showed no improvement of pain with conventional SCS alone or in combination with Contour™, but the combination of FAST™ and Contour™ did improve pain. Three years after FMD, percutaneous leads and an implantable pulse generator were implanted. The program was set to FAST™ and Contour™. After implantation, pain as assessed using the McGill Pain Questionnaire and visual analog scale was relieved even after reducing dosages of analgesic. No adverse events were encountered.

Conclusion

Percutaneously implanted SCS using FAST™ may be effective for refractory pain after FMD for CM-1 with syringomyelia.

Keywords: Electric stimulation, Local anesthesia, Neuromodulation, Paresthesia-free, Refractory pain

Background

Chiari malformation type 1 (CM-1) can impair the flow of cerebrospinal fluid when the cerebellar tonsils drop into the foramen magnum, resulting in syringomyelia in 60–80% of patients [1]. Central neuropathic pain is reported in 40% of patients with CM-1 and syringomyelia [2]. Despite shrinkage of the syrinx after foramen magnum decompression (FMD), pain may not necessarily be relieved [3, 4]. Residual pain is typically treated with analgesics, but if the pain proves resistant to pharmacotherapy, other options for pain relief must be considered.

Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) is a treatment aimed at alleviating refractory pain by applying electrical stimulation to the dorsal column using electrodes implanted in the spinal epidural space. In addition to conventional SCS based on paresthesia, paresthesia-free SCS such as fast-acting sub-perception thqerapy (FAST™) (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) and Contour™ (Boston Scientific) and combinations of these stimulations have recently become available. In particular, FAST™ is useful in that pain relief can be achieved in only minutes, unlike other paresthesia-free SCS that requires a few days to be effective. FAST™ can provide relief from central poststroke pain in which sufficient effects are not obtained with conventional SCS [5]. SCS using FAST™ may also be effective for relieving refractory pain after FMD for CM-1 with syringomyelia. Here we present a case of refractory central neuropathic pain after FMD in a CM-1 patient with syringomyelia who achieved improvement of pain with SCS using FAST™.

Case presentation

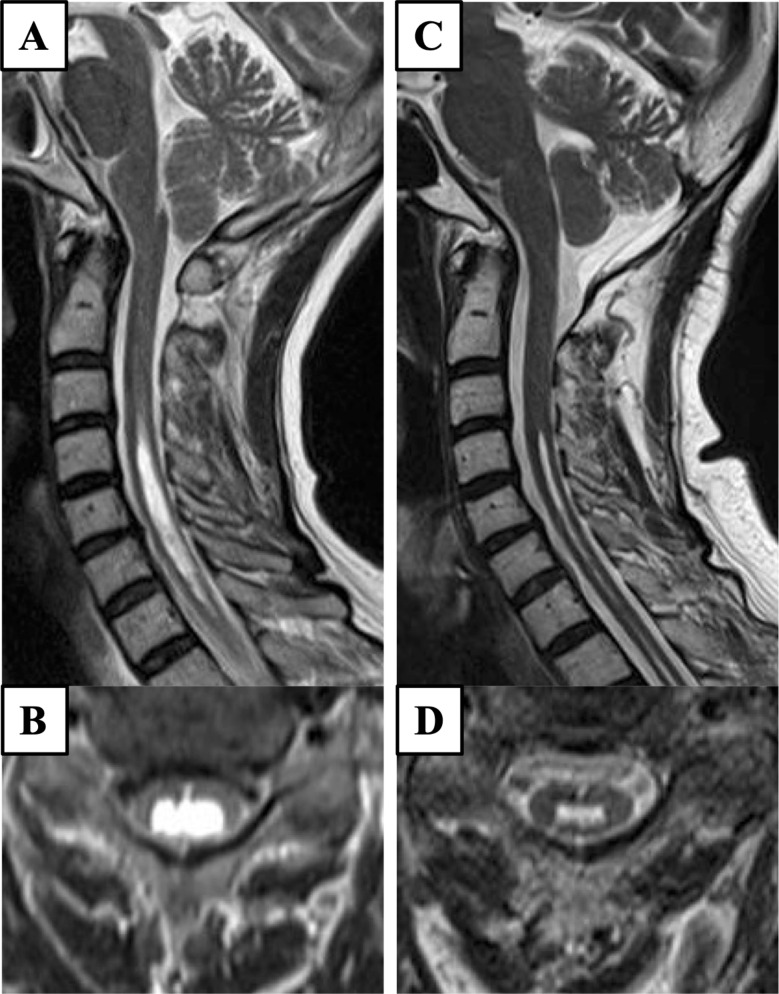

A 76-year-old woman with a history of limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (lcSSc) and asthma came to our hospital diagnosed with CM-1 and syringomyelia. She had a history of several years of bilateral upper extremity and chest-back pain. Experts of dermatology and rheumatology were involved in the diagnosis and treatment of lcSSc, which was very well controlled with small doses of steroids during the entire observation period. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated the dropping of cerebellar tonsil and the syrinx extending from the C4 level of the cervical spine to the thoracic spine. No structures were found in the spinal canal that externally compressed the spinal cord. The pain proved resistant to pharmacotherapy, so FMD was performed to achieve pain relief. After FMD, MRI showed shrinkage of the syrinx and pain relief was obtained (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pre- and postoperative magnetic resonance imaging. Preoperatively, sagittal (A) and axial (B) T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical spine showing Chiari malformation type 1 with syringomyelia. Two years after foramen magnum decompression, sagittal (C) and axial (D) T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging shows shrinkage of the syrinx

Ten months after FMD, bilateral finger, upper arm, and chest-back pain flared-up again. MRI demonstrated that the syrinx remained shrunk, but symmetrical degeneration of dorsal horn due to the syrinx extended from the C4 level of the cervical spine to the thoracic spine was observed. No spinal canal stenosis was pointed out. The brachial plexus block was performed by pain clinicians, but the pain did not improve. Based on these findings, the cause of the pain was diagnosed as central neuropathic pain due to syringomyelia, not neuropathic pain due to lcSSc.

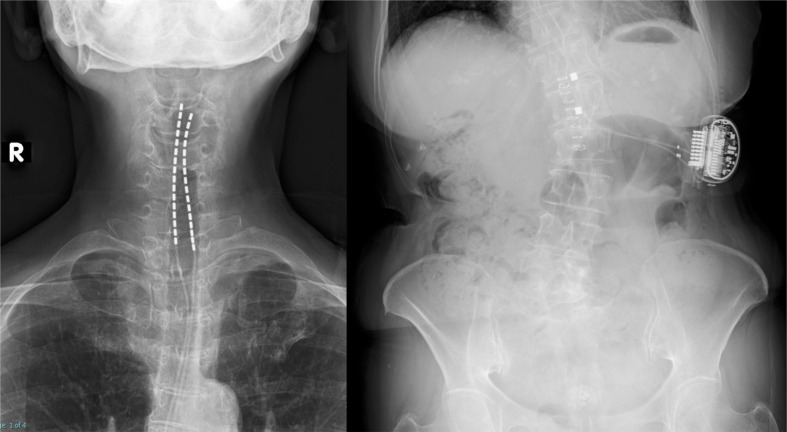

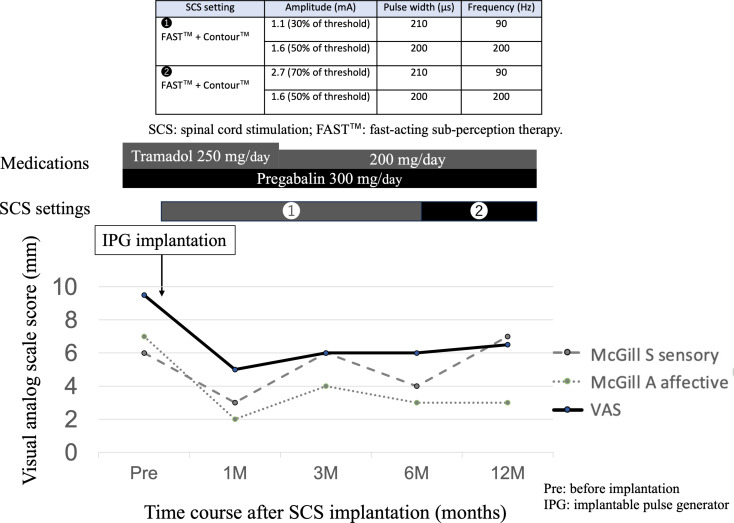

Due to pharmacotherapy resistance, SCS was planned for the purpose of improving pain. As a percutaneous trial of SCS, two 16-electrode leads (Infinion™; Boston Scientific) were inserted from the epidural space between T12 and L1 lamina. The most cephalad side of the leads was placed at the C5 vertebral level through intraoperative testing by paresthesia. Neither conventional SCS alone nor SCS with Contour™ improved any pain scores. However, SCS using FAST™ and Contour™ did improve pain. Subsequently, the implantable pulse generator (IPG) (Wavewriter Alpha™; Boston Scientific) with percutaneous leads was implanted, targeting the same site as in the trial (Fig. 2). Improvement of pain was observed. The main settings of SCS after IPG implantation are summarized in Fig. 3. Visual analogue scale score had been 9.5 preoperatively, improving to a maximum of 5 postoperatively. Affective pain on the McGill Pain Questionnaire was 7 preoperatively, improving to a maximum of 3 postoperatively. On the other hand, sensory pain on the McGill Pain Questionnaire remained unchanged. No adverse events were observed.

Fig. 2.

X-ray. X-ray showing leads were placed through intraoperative testing with paresthesia and positioning of the implantable pulse generator on the left flank

Fig. 3.

Clinical course. Visual analogue scale (VAS) score, McGill’s score (sensory and affective), settings for spinal cord stimulation (SCS) and medications after implantation of the implantable pulse generator (IPG). SCS settings mainly used a combination of fast-acting sub-perception therapy (FAST™) and Contour™. VAS and affective pain on the McGill Pain Questionnaire improved and medication dosages decreased after IPG implantation compared with preoperatively. On the other hand, sensory pain on the McGill Pain Questionnaire was unchanged

Discussion

The present case is the first to suggest that FAST™ based on a novel mechanism differing from conventional SCS can be effective in treating refractory pain in an adult patient with CM-1 and syringomyelia, in whom pain worsened despite syrinx shrinkage after FMD. Nakamura et al. reported that 11 of 17 patients who underwent FMD for CM-1 with syringomyelia achieved inadequate improvement of pain [4]. The present report demonstrated that SCS using FAST™ was effective against postoperative neuropathic pain after FMD for CM-1 with syringomyelia, and described the first clinical application of FAST™ for that pathology.

The mechanism underlying conventional SCS is based on the inhibition of excitatory synaptic transmission in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord by Aβ fiber stimulation [6] and the suppression of secondary neurons by releasing inhibitory neurotransmitters such as GABA and acetylcholine [7]. Conventional SCS can be effective for chronic neuropathic pain such as that related to failed back surgery syndrome [8], acute/subacute zoster-related pain [9], and complex regional pain syndrome [10]. On the other hand, the efficacy of conventional SCS against refractory pain in CM-1 with syringomyelia after FMD has not been elucidated.

According to the review of the literature, including the present study (Table 1), only six cases of SCS for syringomyelia had been reported previously [11–14]. All patients were female, with a median age of 48 years (range: 14–76 years); the patient in the present report was the oldest. Only two patients, including the present, suffered from syringomyelia secondary to CM-1. Schatmeyer et al. treated a pediatric patient in whom SCS proved effective against refractory pain, which was defined as complex regional pain syndrome type 1 after FMD for CM-1 with syringomyelia [14]. However, because children and adults have differing degrees of neuroplasticity, whether SCS was as effective against refractory pain in adults as in children after FMD for CM-1 with syringomyelia remained unclear. The present report suggests that SCS may be as effective in adults as in pediatric patients for refractory pain after FMD for CM-1 with syringomyelia. Most patients underwent percutaneous lead implantation, and only one patient underwent lead implantation with laminectomy. Surgical intervention for syringomyelia had been performed in three patients, and SCS was applied within a few years after the surgical procedure due to poor pain improvement. The median time from onset of pain to SCS application was 4 years (range: several months–16 years), with the present patient suffering from pain for the longest period. In all patients, pain was relieved by SCS and no adverse events were observed. No recurrence of pain after SCS treatment was noted by the end of follow-up (median, 12 months; range, 6–32 months).

Table 1.

Literature review of patients with syringomyelia treated by spinal cord stimulation. The table presents all cases of spinal cord stimulation in Syringomyelia

| Case | Authors | Age/sex | Cause of syrinx | Range of syrinx | Range of pain | Procedure for lead implantation | Time from surgical intervention to SCS application | Time from onset of pain to SCS application | Improvement of pain | Adverse events | Post-SCS follow-up | Recurrence of pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Campos et al. [11] (2013) | 46/F | N/A | C1 ~ T1 | Left cervical area from occipital region down to shoulder | Percutaneous | No surgical intervention | 4 years | Yes | None | 32 months | No |

| 2 | Beyaz et al. [12] (2017) | 50/F | Congenital (not in detail) | Thoracic to sacral region | From trunk to bilateral lower extremities | Percutaneous | 4 previous surgical interventions, 2 years since last surgical intervention | N/A | Yes | None | 6 months | No |

| 3 |

Lu et al. [13] (2022) |

68/F | N/A | T1 ~ T8 | Left chest, back and upper arm | N/A | No surgical intervention | 3 years | Yes | None | N/A | No |

| 4 | Lu et al. [12] (2022) | 41/F | N/A | Medulla oblongata ~ T3 | Headache and back pain accompanied by numbness of right upper limb | N/A | Few years | 5 years | Yes | None | 12 months | No |

| 5 | Schatmeyer et al. [14] (2022) | 14/F | Chiari malformation type 1 with syringomyelia | Cervicothoracic region | Left arm | Surgical implantation with laminectomy | N/A | Several months | Yes | None | 8 months | No |

| 6 | Present case | 76/F | Chiari malformation type 1 with syringomyelia | C4 ~ T4 | Bilateral finger, upper arm, and chest-back | Percutaneous | 3 years | 16 years | Yes | None | 12 months | No |

FAST™ is a novel SCS mechanism that suppresses the electric field around wide dynamic range neurons in the dorsal horn, thereby preventing ascending pain conduction [15]. Recently, SCS using FAST™ has been reported to successfully relieve pain such as central poststroke pain, in which conventional SCS was not sufficiently effective [5]. The present case demonstrated that conventional SCS alone or in combination with Contour™ did not improve pain, but that SCS using FAST™ can improve refractory pain after FMD for CM-1 with syringomyelia. As a possible mechanism by treatment proved effective in the present case, if the dorsal horn was impaired by syringomyelia but the dorsal column was relatively preserved [16], FAST™ may have acted on the dorsal column. As this was a report of a single case, the efficacy of SCS using FAST™ in more patients with refractory pain after FMD for CM-1 with syringomyelia needs to be validated in the future. In addition, efficacy should also be evaluated for different locations and degrees of preoperative neuropathy.

Conclusion

Percutaneously implanted SCS using FAST™ may be effective for refractory pain after FMD for CM-1 with syringomyelia.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CM-1

Chiari malformation type 1

- FAST

Fast-acting sub-perception therapy

- FMD

Foramen magnum decompression

- GABA

Gamma-aminobutyric acid

- IPG

Implantable pulse generator

- lcSSc

Limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- SCS

Spinal cord stimulation

Author contributions

SY, AO, RN, MF, DK, TS, YM and HO contributed to the study concept and design. SY, AO, RN, MF and YN contributed to clinical data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. SY, AO, RN, MF, HO contributed to drafting the manuscript and figures. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present report complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review board at our institution waived the need to obtain informed consent because of the retrospective design (approval no. 31–060 (9559)).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the present report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Arnautovic A, Splavski B, Boop FA, Arnautovic KI. Pediatric and adult Chiari malformation type I surgical series 1965–2013: a review of demographics, operative treatment, and outcomes. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;15(2):161–77. 10.3171/2014.10.PEDS14295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ducreux D, Attal N, Parker F, Bouhassira D. Mechanisms of central neuropathic pain: a combined psychophysical and fMRI study in Syringomyelia. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 4):963–76. 10.1093/brain/awl016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Vlieger J, Dejaegher J, Van Calenbergh F. Posterior fossa decompression for Chiari malformation type I: clinical and radiological presentation, outcome and complications in a retrospective series of 105 procedures. Acta Neurol Belg. 2019;119(2):245–52. 10.1007/s13760-019-01086-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura M, Chiba K, Nishizawa T, Maruiwa H, Matsumoto M, Toyama Y. Retrospective study of surgery-related outcomes in patients with syringomyelia associated with Chiari I malformation: clinical significance of changes in the size and localization of syrinx on pain relief. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(3 Suppl Spine):241–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanei T, Maesawa S, Nishimura Y, Nagashima Y, Ishizaki T, Mutoh M, Ito Y, Saito R. Relief of Central Poststroke Pain affecting both the Arm and Leg on one side by double-independent dual-lead spinal cord stimulation using fast-acting Subperception Therapy Stimulation: a Case Report. NMC Case Rep J. 2023;10:15–20. 10.2176/jns-nmc.2022-0336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linderoth B, Foreman RD. Physiology of spinal cord stimulation: review and update. Neuromodulation. 1999;2(3):150–64. 10.1046/j.1525-1403.1999.00150.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schechtmann G, Song Z, Ultenius C, Meyerson BA, Linderoth B. Cholinergic mechanisms involved in the pain relieving effect of spinal cord stimulation in a model of neuropathy. Pain. 2008;139(1):136–45. 10.1016/j.pain.2008.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar K, Taylor RS, Jacques L, Eldabe S, Meglio M, Molet J, Thomson S, O’Callaghan J, Eisenberg E, Milbouw G, et al. Spinal cord stimulation versus conventional medical management for neuropathic pain: a multicentre randomised controlled trial in patients with failed back surgery syndrome. Pain. 2007;132(1–2):179–88. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wan CF, Song T. Efficacy of Pulsed Radiofrequency or short-term spinal cord stimulation for Acute/Subacute Zoster-Related Pain: a Randomized, Double-Blinded, controlled trial. Pain Physician. 2021;24(3):215–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kemler MA, Barendse GA, van Kleef M, de Vet HC, Rijks CP, Furnée CA, van den Wildenberg FA. Spinal cord stimulation in patients with chronic reflex sympathetic dystrophy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(9):618–24. 10.1056/NEJM200008313430904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campos WK, Almeida de Oliveira YS, Ciampi de Andrade D, Teixeira MJ, Fonoff ET. Spinal cord stimulation for the treatment of neuropathic pain related to Syringomyelia. Pain Med. 2013;14(5):767–8. 10.1111/pme.12064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beyaz SG, Bal N. Spinal cord stimulation for a patient with neuropathic pain related to congenital syringomyelia. Korean J Pain. 2017;30(3):229–30. 10.3344/kjp.2017.30.3.229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu Z, Fu L, Fan X. Spinal cord stimulation for the treatment of neuropathic pain associated with syringomyelia. Asian J Surg. 2022;45(12):2936–7. 10.1016/j.asjsur.2022.06.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schatmeyer BA, Dodin R, Kinsman M, Garcia D. Spinal cord stimulator for the treatment of central neuropathic pain secondary to cervical syringomyelia: illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons 2022, 4(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Metzger CS, Hammond MB, Paz-Solis JF, Newton WJ, Thomson SJ, Pei Y, Jain R, Moffitt M, Annecchino L, Doan Q. A novel fast-acting sub-perception spinal cord stimulation therapy enables rapid onset of analgesia in patients with chronic pain. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2021;18(3):299–306. 10.1080/17434440.2021.1890580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakigi R, Shibasaki H, Kuroda Y, Neshige R, Endo C, Tabuchi K, Kishikawa T. Pain-related somatosensory evoked potentials in syringomyelia. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 4):1871–89. 10.1093/brain/114.4.1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.