Abstract

Biomaterials are substances that can be injected, implanted, or applied to the surface of tissues in biomedical applications and have the ability to interact with biological systems to initiate therapeutic responses. Biomaterial-based vaccine delivery systems possess robust packaging capabilities, enabling sustained and localized drug release at the target site. Throughout the vaccine delivery process, they can contribute to protecting, stabilizing, and guiding the immunogen while also serving as adjuvants to enhance vaccine efficacy. In this article, we provide a comprehensive review of the contributions of biomaterials to the advancement of vaccine development. We begin by categorizing biomaterial types and properties, detailing their reprocessing strategies, and exploring several common delivery systems, such as polymeric nanoparticles, lipid nanoparticles, hydrogels, and microneedles. Additionally, we investigated how the physicochemical properties and delivery routes of biomaterials influence immune responses. Notably, we delve into the design considerations of biomaterials as vaccine adjuvants, showcasing their application in vaccine development for cancer, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, influenza, corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19), tuberculosis, malaria, and hepatitis B. Throughout this review, we highlight successful instances where biomaterials have enhanced vaccine efficacy and discuss the limitations and future directions of biomaterials in vaccine delivery and immunotherapy. This review aims to offer researchers a comprehensive understanding of the application of biomaterials in vaccine development and stimulate further progress in related fields.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Biomaterials, Vaccine delivery, Drug delivery, Vaccine adjuvant

Introduction

Vaccines are an important means of preventing and controlling infectious diseases, and effective vaccine systems are essential for vaccine protection. However, the application of conventional vaccines in the medical field is limited by numerous long-standing problems, such as susceptibility to breakdown by the body, poor immunogenicity, weak targeting, and difficulties in storage and delivery. Innovative approaches for vaccine development are urgently required to meet the growing demand for high-quality vaccines. To address this issue, a new class of biomimetic materials has been extensively explored for use in vaccines. These biomaterials offer targeted and sustained release of multiple immunotherapeutics while protecting them from enzymatic degradation and harsh pH conditions [1], thereby improving vaccine efficacy. This biomaterial-based vaccine delivery system has attracted considerable research attention because it focuses on enhancing the immune response of the body by delivering antigens and adjuvants together. In recent years, biomaterials have been extensively studied and utilized in various fields, such as drug delivery, vaccine development, gene therapy, stem cell therapy, and tissue regeneration, owing to their excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability [2–7]. Biomaterials are currently widely utilized as carriers for vaccine delivery, leading to improved vaccine efficacy for the treatment of diverse diseases. For instance, biomaterials have the ability to transport drugs through physical barriers, such as mucous membranes, and shield antigens from premature degradation, while also targeting lymphoid tissues and effectively presenting antigens and adjuvants to the appropriate immune cells, eliciting a robust immune response. Furthermore, certain biomaterials with immunomodulatory properties and controlled antigen release capabilities demonstrate a sufficient capacity for sustained drug release at the desired location [8, 9].

Certain biomaterials possess inherent immunogenicity and can serve as effective immunoadjuvants. Vaccine adjuvants play a pivotal role in augmenting the immune response to antigens, thereby bolstering the capacity to prevent infections. Consequently, they are indispensable for the development of safe and efficacious vaccines against a broad spectrum of infectious diseases. Recently, several vaccine adjuvants have been developed and approved for human use, including MF59, AS03, AF03, and other emulsion adjuvants [10]. Among these, MF59 nanoemulsion has been approved as an influenza vaccine adjuvant in the United States, with an excellent vaccination record [11, 12].

The exceptional potential of biomaterials positions them with extensive developmental prospects in the realm of biomedical engineering. However, the current challenges pertaining to vaccine transportation and storage conditions, delivery efficiency, cell targeting, and material safety remain significant hurdles that biomaterials must surmount in the field of vaccine delivery. Consequently, a systematic review of recent advancements in biomaterials for vaccine development to guide and inspire further innovation is imperative. This review summarizes the types of biomaterials and strategies used for their reprocessing, including polymer-based nanoparticles (PNPs), liposome-based nanoparticles (LNPs), hydrogels, and microneedles (MNs). Second, we discuss the physicochemical properties of biomaterials that affect immune reactions. These properties include morphology and structure, particle size, and surface properties. Third, we describe the routes of administration of the biomaterials used for vaccine delivery, such as injectable vaccination, transdermal immunization, intranasal administration, and oral administration. Subsequently, we summarize the design considerations for biomaterials as vaccine adjuvants and introduce the application of biomaterials in vaccine development. Finally, we provide an overview of some biomaterial deficiencies in vaccine development and immunotherapy, while highlighting avenues for future research. Ultimately, this review summarizes the advancements in biomaterial research for vaccines, aiming to enhance the understanding among researchers in related fields and facilitate the rational design and application of diverse biomaterials in vaccine development.

Types of biomaterials

Biomaterials can be injected, implanted, or applied to the surface of tissues in biomedical applications to interact with biological systems and trigger therapeutic responses [13]. The selection of biomaterials is critical in vaccine preparation because different materials can perform different functions. Biomaterials are typically categorized based on their origin as organic, inorganic, or biologically derived materials [2].

Organic nanomaterials

Nanomaterials are a class of materials with dimensions on the nanometer scale that are easily degradable, noncytotoxic, highly controllable, and versatile. They can serve as vaccine delivery systems to protect vaccine antigens from degradation by encapsulating them, improving their stability and biological activity, and enabling targeted delivery to specific cells or tissues through surface modification. Common organic nanomaterials include poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), polyethyleneimine (PEI), chitosan (CS), self-assembled peptides (SAPs), liposomes, and immunostimulatory complexes (ISCOM). Their application in vaccine delivery can enhance the stability of immunogens, improve antigen presentation, and enhance the immune response.

Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)

The biodegradable polymer PLGA has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for vaccine delivery [14]. It has been extensively studied for its potential application in vaccine delivery because of its exceptional biocompatibility, biodegradability, and safety in the human body [15]. PLGA nanoparticles offer two distinct advantages for vaccine applications. First, PLGA polymers demonstrate a suitable drug encapsulation effect because they are usually relatively robust, can form large pores, and can be used for bulk-loading drugs and proteins [16]. Second, they demonstrate a slow-release effect, such that drug encapsulation within PLGA nanoparticles can improve their loading capacity and facilitate controlled release [17]. The internalization of PLGA nanoparticles in cells typically occurs through lattice protein-mediated endocytosis; however, vaccine delivery is hindered as hydrophobic particles are cleared from the bloodstream or taken up by the reticuloendothelial system (RES) in the liver [18, 19]. Several surface modifications have been developed to address these limitations and protect nanoparticles from RES, such as coating the nanoparticle surface with polyethylene glycol (PEG) to conceal the hydrophobicity of PLGA owing to its hydrophilic properties [20, 21].

Notably, PLGA polymers have recently garnered increasing attention in the field of cancer therapy [22]. PLGA polymers undergo hydrolysis in vivo to produce metabolizable lactic acid and glycolic acid. Since both by-products are endogenous and can be converted within the tricarboxylic acid cycle in the body, the potential toxicity resulting from their use in drug delivery can be considered negligible [23]. From another perspective, current research indicates a close relationship between the metabolic environment and the formation of an immunosuppressive microenvironment within tumors [24]. In acidic conditions with lactic acid present, regulatory T cell populations may proliferate and differentiate, thereby playing a multifaceted role in maintaining the immunosuppressive microenvironment within the tumor. Moreover, a significant proportion of commercially available PLGA-based formulations currently approved for clinical use are employed in treating malignant tumors [25]. These findings may offer valuable insights for inspiring future cancer vaccine development and accelerating its pace. However, the accumulation of lactic acid and glycolic acid produced by the hydrolysis of PLGA can also lead to inflammation, thereby raising safety concerns [26].

Polyethyleneimine

PEI is a hydrophilic cationic polymer that aggregates negatively charged DNA and antigens in vivo. The amorphous mesh structure of PEI acts as a “proton sponge” in the lysosome, which is unique and remarkable, giving it a high transfection efficiency [27, 28]. PEIs are also rich in reactive amines, such as secondary and tertiary amines, which provide various structural modification possibilities, expanding their applications in targeting reagents and mitigating toxicity [29] and enabling them to bind strongly to nucleic acids. Therefore, they have been widely used for nucleic acid delivery for several decades. PEI-based nanoparticles can be used as adjuvants to improve the efficacy of conventional infectious and tumor vaccines [30–34].

Nanoparticles (NPs) offer a promising platform for vaccine delivery; however, NP-based vaccines often entail intricate synthetic and post-modification procedures, which present technical and manufacturing challenges in vaccine production. Facile modification of PEI can effectively address this issue. Nam et al. [35] combined the straightforward coupling chemistry of PEI with neoantigens, followed by electrostatic assembly with a cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) adjuvant, thereby achieving self-assembly of PEI NPs. The engineered PEI NPs exhibited non-toxicity, possessed a particle size below 50 nm, and demonstrated a remarkable capability in promoting antigen-presenting cell activation and antigen cross-presentation. This method shows significant potential for streamlining the manufacturing of individualized cancer vaccines. However, it is crucial to emphasize that stringent control measures should be implemented to minimize its residue in pharmaceutical preparations owing to the limited biodegradability of PEI within the body.

Chitosan

CS is a naturally occurring polymer derived from the alkaline deacetylation of chitin and is commonly found in the exoskeletons of crustaceans and insects. It is a linear polysaccharide with a cationic charge, composed of D-glucosamine and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine [36]. These molecules contain reactive hydroxyl and amino groups. When dissolved in acidic media, the amino group of CS becomes highly protonated, allowing electrostatic interactions between CS and mucins, resulting in strong adhesion properties for CS. The adhesive properties of chitosan and its capacity to enhance the transport of macromolecules across mucosal surfaces are key factors contributing to its immunomodulatory properties [37, 38]. In addition, the presence of hydroxyl and amino groups in the CS molecule enables the incorporation of various functional groups through molecular or chemical modifications. This addresses the issue of reduced solubility in neutral and alkaline solutions, which allows for stability within a specific pH range. CS derivatives obtained after modification are mainly improved in terms of permeation enhancement and adhesion properties, and various CS derivatives, such as glycosylated or trimethyl CS, have been widely explored for vaccine delivery [39–42]. Recent studies have primarily focused on the application of CS-based nanovaccines in nasal mucosal delivery systems, capitalizing on the ability of CS to traverse tight junctions and its adhesive properties. These properties enhance mucosal adhesion and antigen uptake, while demonstrating intrinsic immunostimulatory capabilities [43].

For a considerable duration, the challenges of ensuring the safety and efficacy of live virus vaccines have posed significant obstacles to vaccine development. In light of this, Hao et al. [44] ingeniously encapsulated wild-type Zika virus within a chitosan gel matrix, aptly named Vax. This composite gel effectively confines the virus and orchestrates the recruitment of immune cells for viral eradication and antibody production throughout the organism. Remarkably, mice immunized with Vax in the animal trials were entirely shielded from the lethal effect of Zika virus. This groundbreaking discovery offers immense convenience for the expeditious preparation of safe and efficacious vaccines, as well as fortification against large-scale epidemics in future scenarios. Unfortunately, the intricate manufacturing and extraction processes associated with CS pose complexities that impede its purity enhancement, thus limiting its effectiveness in certain applications.

Self-assembling peptides

Peptide materials have unique properties and are made from simple amino acids under physiological conditions. They can self-assemble into nanostructures at various levels through non-covalent interactions to form functional materials with outstanding properties. The self-assembled morphology of peptide supramolecular structures and their diverse applications have been extensively investigated, showing significant potential for vaccine delivery and vaccine design owing to their excellent biocompatibility, facile preparation, and tunable functionality [45]. Zhu et al. [46] developed a peptide hydrogel nanoparticle containing functional peptide chains at the core and a framework of SAP, which exhibits significant biological functions, such as effective inhibition of local inflammation and elimination of non-resistant cells. It can independently induce immune activation without adjuvants and has a longer duration than simple peptides.

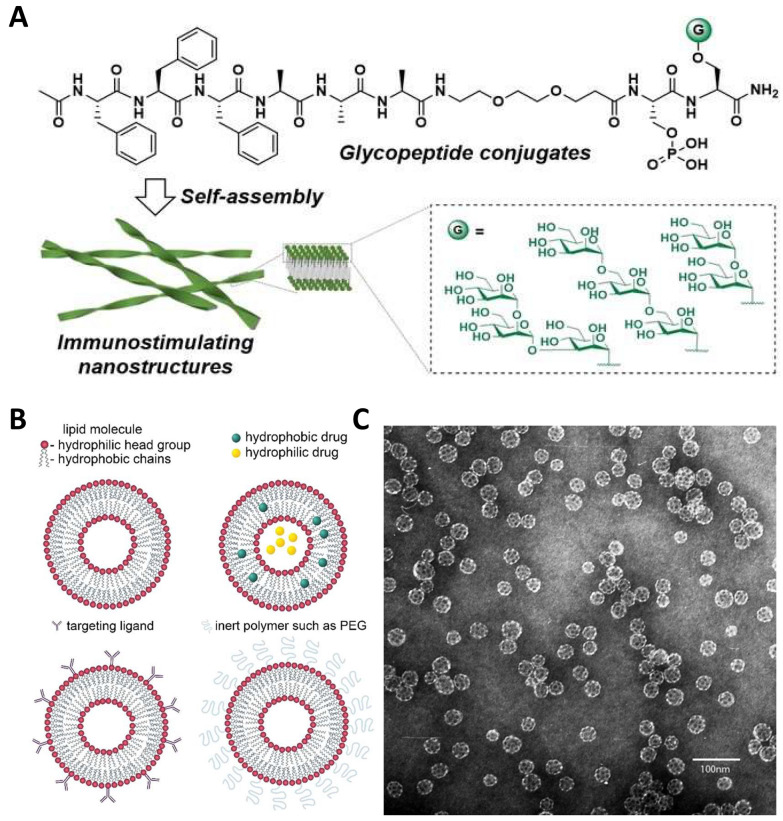

Wang et al. [47] developed a glycopeptide conjugate (GPC) (Fig. 1A), designed to effectively carry various mannan-oligosaccharides and self-assemble into stable nanoribbons, taking advantage of the immunostimulatory ability of high-mannose-type N-glycans. These GPCs exhibited varying affinities for C-type lectin receptor (CLR) proteins in in vitro binding assays, with some mannosylated peptides demonstrating strong immunostimulatory effects in vivo, highlighting their potential as vaccine adjuvants.

Fig. 1.

Structure of some biological materials. A Self-assembling GPCs systems. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [47], Copyright 2024, Angewandte Chemie International Edition. B Schematic representation of liposome, liposome encapsulating hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs, immunoliposome functionalized with targeting ligands, and sterically stabilized (“stealth”) liposome functionalized with inert polymers such as PEG. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [49], Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society Nano. C The immunostimulatory complex ISCOMATRIX was observed by electron microscopy after negative staining (Bar = 100 nm.) Reproduced with permission from Ref. [50], Copyright 1995, In Vaccine Design: The Subunit and Adjuvant Approach

In conclusion, SAPs offer numerous advantages for drug delivery; however, there have been no documented instances of vaccines based on self-assembling peptides reaching the market. The intricate composition, challenges in large-scale production, and unpredictable modulation of the immune system present ongoing obstacles to the clinical application of self-assembling peptides [48]. It is anticipated that advancements in medical informatics and continual innovation in vaccine delivery systems will effectively address these issues.

Liposomes

Liposomes have been widely studied as nanodrug carriers for vaccine delivery systems. They are closed vesicles composed of lipid bilayers of phospholipids and cholesterol, with a biofilm-like structure that encapsulates water-soluble and lipid-soluble drugs (Fig. 1B) [49]. Liposomes have been extensively researched for their potential as vaccine delivery systems because of their biocompatibility, biodegradability, and non-toxic nature. They are commonly utilized as drug carriers and offer numerous advantages, such as high targeting specificity, effective protection of the encapsulated drug, controlled and gradual release of the drug, improved therapeutic index, and reduced side effects [51]. A key advantage of liposomes is their capacity to simultaneously deliver antigens and adjuvants to the same antigen-presenting cells (APCs), which is crucial for eliciting an effective immune response. Additionally, liposomes prevent antigen degradation, enhance APC uptake, facilitate cytoplasmic release, and possess immunostimulatory properties [52].

Liposomes can be classified as neutral, cationic, or anionic based on their composition [53, 54]. Cationic liposomes, which are composed of a stable complex of synthetic cationic lipids and anionic nucleic acids, are the most commonly utilized non-viral delivery systems for nucleic acid drugs [55]. Maria et al. recently reported a cationic liposome vaccine designed to co-deliver antigens and adjuvants capable of inducing a robust antigen-specific adaptive immune response [56]. Cationic liposomes consisting of dimethyl dioctadecylammonium bromide (DDAB), cholesterol (CHAL), and oleic acid (OA) with an imiquimod (IMQ) adjuvant were validated using mouse immunization as an effective delivery platform for protein antigens capable of targeting and inducing maturation via dendritic cells (DCs). Furthermore, Farrhana et al. [57] utilized standard peptide synthesis to couple the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16 E7 protein peptide (8Qm) to polyleucine, and then, self-assembled nanoparticles or incorporated the peptide into liposomes for cancer research. Following a single immunization, liposomal delivery of the 8Qm-coupling significantly enhanced survival, reduced tumor growth in mice, and eradicated mature tumors growing for seven days in mice. This experimental breakthrough illustrates that fully defined natural hydrophobic amino acid-based polymers coupled with peptide antigens can function as effective vaccine delivery systems. Given the demand for vaccine therapies targeting intracellular infectious diseases and malignant tumors, it is anticipated that the vaccine delivery systems presented herein will be utilized in future applications. However, liposomal formulations of anticancer drugs lack cancer-cell targeting abilities when administered intravenously, leading to numerous adverse reactions. Therefore, appropriate delivery modalities are required to maximize their effectiveness.

Immunostimulatory complexes

ISCOMs are cage-structured nanoparticles, approximately 40 nm in size, initially reported in 1984 as antigen delivery systems that possess strong immunostimulatory properties [58]. They can be formulated by mixing antigens, saponins, phospholipids, and cholesterol, using lecithin-assisted hydrophobic modulation. Therefore, they have the potential to serve as reliable vaccine delivery systems and enhancers. For example, when antigen 85 composite is incorporated into ISCOMs, it can boost both humoral and cellular immune responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis following pulmonary immunization [59]. However, a major drawback of traditional ISCOM synthesis is the need to add antigenic proteins, which limits the variety of antigens that can be used, making the process complex and difficult to control. To address these challenges, the ISCOMATRIX® solution was developed, which is a prefabricated particle resembling a cage (Fig. 1C) [50] with a diameter typically ranging from 40 to 50 nm. It consists of purified saponins (ISCOPREP® saponin), phospholipids, and cholesterol [60]. This potent immunomodulatory agent can affect both innate and adaptive immune responses. ISCOMATRIX vaccines have demonstrated a broad spectrum of antibody- and antigen-specific T-cell responses in cancer immunotherapy and infectious disease treatment [61]. The utilization of ISCOM in vaccine preparation has been extensively researched for numerous years and has significantly contributed to the advancement of veterinary and human vaccine development.

Inorganic nanomaterials

Inorganic nanomaterials are usually structurally stable but not biodegradable, and their physicochemical properties must be modified to enhance their biocompatibility for better use in nanovaccines. However, inorganic nanomaterials are inexpensive to produce and safe for various applications, and their controlled synthesis and rigid structure are two of their primary advantages. A variety of metals and their oxides, inorganic salts, and non-metallic oxides have potential as nanomaterials for vaccines, such as gold, carbon, and silicon dioxide, which are already widely used [62–64]. Nanomaterials are composed of nanoparticles whose synthesis can result in a range of shapes, sizes, and surface modifications.

Metals and their oxide nanoparticles

Metallic nanoparticles, including gold nanoparticles (GNPs) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), are widely used in vaccine delivery systems owing to their distinct optical and electrical characteristics. These nanoparticles are typically smaller than 1 µm, which allows them to interfere with viral replication in the host cells. This provides an advantage over other non-nanomaterials [65]. Surface-modified or functionalized metallic nanoparticles can enhance the stability and delivery efficiency of vaccine antigens as well as boost the immune response by activating immune cells or altering the immune environment. GNPs have low toxicity and good biocompatibility and are more colloidally stable than AgNPs; thus, they have been extensively studied [66]. GNPs have demonstrated remarkable immunomodulatory and adjuvant properties. Moreover, intradermal injection of GNPs containing glucagon peptidogens C3-A1 leads to the recruitment and retention of immune cells in the skin of patients with type 1 diabetes [67].

In the last two years, GNPs have been increasingly developed for various viral assays and diagnostics [68, 69]. Notably, GNPs can cause cytotoxicity and activate inflammatory responses at high doses (> 8 mg/kg) [70]. Additionally, several types of metal-based nanoparticles are potent antiviral drugs with significant antiviral effects when used bare or after surface modification, including nanoparticles composed of metals such as silver or metal oxides such as zinc oxide, titanium dioxide, and iron dioxide [71, 72].

Carbon nanoparticles

Carbon nanoparticles (CNPs) with sizable mesopores and macropores demonstrate exceptional capabilities as antigen carriers. When utilized as adjuvants for oral vaccines, they can elicit robust immune responses mediated by immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin A (IgA), Th1, or Th2 [63]. Furthermore, CNPs can synthesize nanotubes that can simultaneously load tumor testicular antigens and adjuvants to build effective tumor vaccines [73]. Carbon nanotubes show promise as a method for delivering vaccines; however, their potential toxicity in living organisms is still uncertain owing to their irregular shape and strong pro-inflammatory effects [2].

Non-metallic oxide nanoparticles

Silicon dioxide nanoparticles (SiNPs) are prominent non-metallic oxide nanoparticles. They are excellent vaccine carriers with small particle sizes, stable physicochemical properties, good biocompatibility, and high drug-carrying capacity. They have been widely used as feed additives, veterinary drugs, and new animal vaccines because they can encapsulate drugs, providing protective and controlled release. They can also cross the blood–brain barrier and biofilms and can target other transport pathways [74]. SiNPs are also candidates for transdermal vaccines and gene therapy through controlled and sustained drug release into the skin and enhanced skin penetration by encapsulating drug components [75]. SiNPs can induce Th1- and Th2-mediated immune reactions, making them powerful vaccine adjuvants [76, 77].

Mesoporous silica has a unique molecular sieve structure and strong adsorption properties, and injecting mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) into mice effectively enhances the immune response [78]. Furthermore, mesoporous silica microrods can adsorb PEI and tumor antigens through electrostatic action and can promote the secretion of inflammatory cytokines when synergistic with PEI, showing broad prospects in anti-tumor therapy [79]. It is widely acknowledged that vaccines typically rely on cryopreservation and cold chain transport, rendering them highly susceptible to inactivation at non-optimal temperatures. In light of this, scientists have successfully preserved the vaccine's efficacy for up to three years at room temperature by encapsulating the protein with a layer of silica coating, thereby safeguarding its structural integrity while preserving immunogenicity [80, 81]. As an advanced material, SiNPs have immense potential for various applications; however, appropriate processes and additives must be employed during preparation to maintain their stable dispersion state and prevent any adverse impact on the performance or application effectiveness owing to their tendency to agglomerate and precipitate in water-based dispersion systems.

Biologically derived materials

Unlike the organic and inorganic nanomaterials mentioned earlier, biologically derived materials are primarily sourced from cells, bacteria, and viruses. This category includes virus-like particles (VLPs) and outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) [82].

Virus-like particles

VLPs are self-assembled multiprotein nanoparticles. They consist of biocompatible envelope proteins without a viral genome [83]. They resemble viruses in appearance and structure, and their lack of viral nucleic acids prevents their replication in vitro. They are biodegradable nanoparticles of approximately 20–100 nm in size, which are optimal for DCs and other APC-recognizing particles. They can rapidly pass through tissue barriers to reach draining lymph nodes and effectively activate an immune response [84]. Innate and adaptive immune responses can be activated in the absence of viral replication through the presentation of pathogenic structural proteins. Furthermore, VLPs have a highly repetitive and rigid structure, allowing them to display multivalent antigenic epitopes on their surface and form extensive cross-links with B cell receptors, thereby stimulating B cells and eliciting a strong and long-lasting antibody response [85].

VLPs have been extensively utilized in vaccine development because of their favorable safety profiles and strong immunogenicity. Recently, several VLP-based vaccines have been introduced, including those targeting HPV (Cervarix®, Gardasil®, and Gardasil9®) and hepatitis B (Engerix®, Sci-B-Vac™, RTS®, and S VLP®) [86]. VLPs have the potential to transport both native viral antigens and modified foreign antigens attached to VLPs through chemical bonding or gene fusion. For example, a VLP vaccine designed for breast cancer incorporates human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2) epitopes linked to cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV), demonstrating efficacy in stimulating specific immune responses and offering protection against tumors in a mouse model [87]. Several VLP vaccines are currently undergoing clinical trials, including those targeting chikungunya virus, neocoronavirus, influenza, cancer, and encephalitis [88]. However, the application of VLPs is somewhat limited owing to the challenges associated with their low expression yield and complex preparation.

Outer membrane vesicles

OMVs are naturally derived from gram-negative bacteria and range in size from 20 to 250 nm. They possess a bilayer lipemic membrane nanostructure containing lipopolysaccharides, membrane proteins, phospholipids, toxins, enzymes, periplasmic proteins, RNA, DNA, and peptidoglycans [89]. OMVs are generally stable under various treatments and temperatures, making them highly versatile for engineering the expression of a wide range of antigens [90, 91]. Furthermore, OMVs are appealing as adjuvants for delivering vaccines because they contain immunogenic components from the host bacterium that can stimulate both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses to antigens [92]. They offer many advantages in terms of drug loading and delivery. Hong et al. [93] investigated a senescent cancer cell-derived nanovesicle (SCCNV), which contains interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α expressed during cell senescence. The presence of these endogenous factors confers immunogenicity to the vaccine without the need for exogenous adjuvants. Furthermore, the delivery system based on red blood cell membrane (RBCm) offers the advantage of prolonging anti-tumor therapy and overcoming accelerated blood clearance; however, its limited application is attributed to low drug-loading capacity and lack of tumor-targeting ability. To tackle this challenge, Zhang et al. [94] engineered a versatile delivery system by employing hyaluronic acid (HA)–hybridized RBCm (HA&RBCm) as a coating to surmount the endothelial barrier of the reticuloendothelial system. Meanwhile, the honeycomb architecture within the system expanded the encapsulation capacity, thereby establishing a secure and efficacious anti-tumor therapeutic carrier. At present, Several OMV-based vaccines have shown promising results in clinical trials, including the OMV Meningitis B (MenB) vaccine [95].

Application of exosomes

In recent years, exosomes and cell-derived nanovesicles (CDNs) have received much attention due to their potential therapeutic applications in a variety of diseases. Exosomes are nanoscale vesicles secreted by cells which are endogenous natural drug carriers that are stable, biosecure, and less immunogenic than exogenous carriers [2]. They are able to effectively penetrate biofilms and remain stable in the blood, thereby enhancing vaccine targeting and preventing premature antigen leakage. In the field of targeted drug delivery, bioinspired simulated exosome nanovesicles have been developed with higher yields compared to natural exosomes to deliver chemotherapy drugs to tumor tissues [96]. Recently, exosomal noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) have shown potential for treating bacterial infections, such as tuberculosis (TB. Exosomal ncRNAs play a pivotal role in modulating the immune response to M. tuberculosis infection by activating specific signaling pathways that regulate the infection process [97]. Progress in sequencing technologies has increasingly revealed the role of exosomal ncRNAs in regulating the transcriptional and post-transcriptional expression of host genes, thereby influencing M. tuberculosis to the host environment and its pathogenicity [98]. Additionally, their role in delivering vaccine components across different infectious diseases offers promising prospects to develop more effective vaccine strategies against M. tuberculosis in the future [99].

Synergies between exosomes and cell-derived nanovesicles

In addition, exosomes can be used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases in synergy with CDNs. A nanotherapeutic drug delivery strategy has been developed using fused nanovesicles derived from plant and animal cells with high clinical potential. Up to now, the existing therapeutic methods for autoimmune diseases still have problems such as low efficacy, serious side effects and difficulty in reaching target tissues [100]. A multifunctional fusion nanovesicle that can target lesions is designed for the treatment of autoimmune skin diseases. By utilizing centrifugal force and micropores, CDNs can be generated on a large scale, which provides a cost-effective method for producing these vesicles for a variety of applications [101]. In addition, in the context of regenerative medicine, stem cell-derived exosomes and cell-engineered nanovesicles have shown promise in promoting cell proliferation, migration, and anti-aging, and can be used to treat wound injuries and skin aging [102]. These extracellular vesicles contain biomolecules that promote intercellular communication and tissue regeneration, making them attractive candidates for therapeutic interventions. Overall, the literature on exosomes and CDNs demonstrates their different roles in immune response, targeted drug delivery, cancer progression, and regenerative medicine. Further studies are needed to fully understand the mechanisms of its therapeutic effects and to optimize its use in clinical Settings [103].

This section provides a detailed introduction to the classification and properties of biological materials, along with a summary of their advantages and disadvantages in vaccine applications (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification, properties, and advantages and disadvantages of biological materials

| Types | Classification | Properties | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic nanomaterials | Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) | Biocompatible, biodegradable, safe, and particle size controllability | Bioactive molecules can be encapsulated, with accurately targeted delivery, and long-term slow release | Phagocytosis may accelerate degradation. It is hydrophobic and poorly encapsulated for hydrophilic drugs | [104, 105] |

| Polyethyleneimine | Hydrophilic, easily modified structurally, and low toxicity | Has a “proton sponge” effect, a high transfection efficiency, and strongly binds nucleic acids | It is not biodegradable and may contain drug residues | [27, 28] | |

| Chitosan | Adhesive, biocompatible, biodegradable, low toxicity, and easy to obtain and modify | Enhances the adhesion and absorption of antigen by mucosa and prolongs the time of drug action | Relatively high cost, poor stability, purity issues | [37, 38] | |

| Self-assembling peptide | Biocompatible and controllable | Can self-assemble into various layered nanostructures; preparation is simple, and function can be controlled | The composition is complex, not easy to mass produce, and the stability is poor at low pH | [45] | |

| Liposomes | Biocompatible, biodegradable, and non-toxic | Can encapsulate water-soluble and fat-soluble drugs and offers targeted delivery and slow drug release | High production costs, oxidation and fusion problems, structural instability, RES clearance | [49] | |

| Immunostimulatory complexes | Safe | It serves the dual purpose of presenting antigens and acting as an immune adjuvant, leading to a comprehensive, long-lasting, and robust immune response | Preparation is complex and difficult to control | [58, 106] | |

| Inorganic nanomaterials | Metals and their oxide nanoparticles | Biocompatible, has low toxicity, and has optical and electrical properties | Interferes with viral replication in host cells, is easy to synthesize various shapes, and is easy to surface modify or functionalize | Surface ligands and charges may cause toxicity | [65, 107] |

| Carbon nanoparticles | Biocompatibility, stability, controllability, easy modification | The specific surface area is extensive, with diverse sizes and shapes, allowing for selective adsorption and potential functionalization | Impurities or surface ligands may cause toxicity | [63, 107] | |

| Non-metallic oxide nanoparticles | Biocompatibility, particle size control, large specific surface area, easy modification, thermal stability | Strong drug loading capacity, easy synthesis and functionalization, and is conducive to long-term preservation of vaccines as coatings | Agglomeration and precipitation are easy to occur, and there is a certain toxicity | [80, 81, 108] | |

| Biologically derived materials | Virus-like particles | Biodegradable, small particle size, safety, easy to design | Uses the advantages of its own viral structure to enhance the immune response while avoiding viral replication | The expression yield is low, the preparation is complex, and there are stability problems | [84, 85, 109] |

| Outer membrane vesicles | Biocompatible and has low immunogenicity | The immunogenic components derived from its parent bacteria elicit both humoral and cell-mediated antigenic immune responses | The lipopolysaccharide component of the surface may cause an inflammatory response | [110–112] |

Reprocessing strategies for biomaterials in delivery systems

Biomaterials that allow the spatial and temporal control of loaded reagents have evolved into powerful tools for vaccine delivery and localization [113, 114]. Current biomaterial platforms encompass a variety of dynamic systems including PNPs, LNPs, hydrogels, and MN arrays. Each strategy has been used in various synergistic therapies. The characteristics and design considerations of the delivery system are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics and design considerations of several delivery systems

| Delivery systems | Formation | Functional characteristics | Design considerations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer-based nanoparticles | Composed of natural/synthetic high polymer | The loaded active compounds can be embedded in the polymer core or adsorbed onto the polymer core surface | Controlled delivery of vaccines is achieved by controlling size, shape, and surface characteristics | [115, 116] |

| Liposome-based nanoparticles | The composition includes lipids that can be ionized, cholesterol, phospholipids, and lipids modified with polyethylene glycol | Can encapsulate water-soluble and fat-soluble drugs, has a high degree of targeting, can effectively protect the encapsulated drugs, and can control and slowly release drugs | Its formulation composition, size, and surface charge affect its efficacy and pharmacokinetics, and these factors can be controlled to optimize vaccine delivery | [117, 118] |

| Hydrogels | High hydrophilic polymers form three-dimensional network structures by cross-linking in water | High doses of non-specific drug distribution can be accurately delivered to specific sites while achieving continuous controlled release of drug molecules | Generally, drug-containing hydrogels are mainly diffused and released by controlling the degradation, swelling, and mechanical deformation of the hydrogel mesh, ultimately leading to controlled drug release | [119–121] |

| Microneedles | Consists of a plurality of micrometer small needle tips connected in an array on the base | Can be directed through the stratum corneum, avoiding blood vessels and nerves to deliver the drug precisely and effectively below the stratum corneum; allows the active ingredient to be released in a continuous or controlled manner | The length, size, and shape of the microneedles determine their mechanical properties, insertion capacity, drug-loading capacity, and drug-delivery efficiency and can be individually designed according to therapeutic needs | [122, 123] |

Vaccine delivery systems

Polymer-based nanoparticles

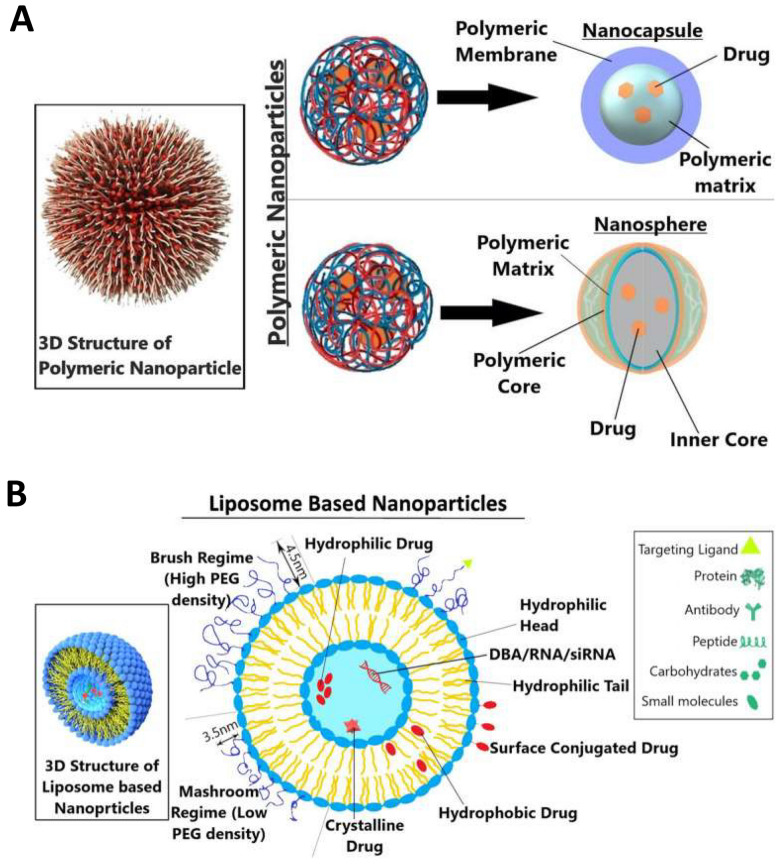

PNPs are a class of nanomaterials composed of synthetic polymers capable of loading active compounds and encapsulating them within the polymer core or adsorbing them onto the surface, typically in the form of nanocapsules and nanospheres (Fig. 2A) [115]. Nanospheres have a matrix with a physical and uniform dispersion of the active ingredient, whereas nano-capsules have a vesicular structure, with the active ingredient enclosed within a cavity surrounded by a polymer membrane. Polymeric micelles are another type of PNP. Amphiphilic polymer molecules self-assemble in aqueous solutions to form colloids with a hydrophobic core and hydrophilic shell. The distinctive architecture of polymeric micelles offers significant advantages in vaccine delivery. The hydrophobic core can encapsulate a large amount of the hydrophobic drug, which markedly improves its solubility in water. Additionally, the structure allows for interactions with proteins, cells, and other biological components, influencing pharmacokinetic behavior and drug distribution [116].

Fig. 2.

Vaccine delivery system. A Types of polymeric nanocarriers—nanosphere and nanocapsule—are depicted in the diagram. A polymeric shell that regulates the drug’s release profile from the core of the nanocapsule surrounds an oily core, typically where the medication dissolves. Using a continuous polymeric network as its foundation, nanospheres allow the medicine to either be maintained inside or adsorbed onto its surface. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [115], Copyright 2023, Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment. B Vesicle structure of nanoparticles based on liposomes. The polymer of the mashroom regime (low PEG density) consists of independent random coils of number Flory radius RF3 on the surface of the member. The polymer chain of the brush regime more mutually interacts and is densely packed. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [115], Copyright 2023, Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment

Over the past decade, PNPs have achieved significant advancements in vaccine development because of their substantial potential for precise drug and vaccine delivery [124–127]. Owing to their exceptional customizability, biocompatibility, and biodegradability, lipid nanoparticles have been extensively utilized in the development of particulate vaccines for emerging infectious diseases [128–130]. They can be formed from a range of materials, including natural polymers commonly occurring in nature, and synthetic polymers manufactured artificially [131, 132]. Their rich chemistry and multifunctional combinatorial structures provide a new platform for the development of vaccines with high efficiency and efficacy and can modulate vaccine delivery and immune activation effects by changing the chemical structure and physical properties of polymers. Additionally, they have controllable size, morphology, and surface properties that enable controlled delivery of vaccines and increase immunogen stability and immune responses by controlling the delivery rate.

Liposome-based nanoparticles

LNPs are lipid vesicle delivery systems that are non-viral and multifunctional, comprising ionizable lipids as the primary components, cholesterol, phospholipids for structural integrity, and PEG-modified lipids to aid in maintaining stability (Fig. 2B) [117]. Following extensive research, LNPs have been utilized for the administration of various vaccines and have significantly enhanced both humoral and cellular immune responses. LNPs can stimulate robust follicular Th cells, durable plasma cells, B cells in germinal centers, and memory B cells, resulting in enhanced humoral immune reactions after vaccination [133]. Recently, LNPs have been extensively studied as potential carriers for mRNA vaccines in clinical trials of COVID-19, tumor vaccines, and influenza vaccines. For example, emergency marketing authorizations were granted in 2020 for Pfizer’s BNT162b2 vaccine (Comirnaty) and Moderna’s mRNA-1273 vaccine (Spikevax), both of which utilize LNPs for mRNA antigen delivery [134, 135]. The successful use of these two mRNA vaccines has yielded exciting results and made significant contributions to the fight against COVID-19. LNPs have accelerated the utilization of mRNAs in humans, and their promising prospects in vaccine development are highly anticipated.

Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) are a type of lipid-based nanocarrier comprising active pharmaceutical ingredients and solid lipids, along with surfactants and/or co-surfactants. They serve as vaccine delivery systems that entrap drugs within natural or synthetic solid lipids, such as lecithin, acting as carriers [136]. Their internal oil phase was replaced with a solid lipid to reduce the limitations associated with conventional lipid formulations, avoid the use of organic solvents during preparation, provide better stability, reduce drug degradation, and maintain relative stability during storage. SLNs play a pivotal role in various applications in nanotechnology, such as vaccine delivery and cancer treatment, owing to their capacity to encapsulate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds, biocompatibility, and ease with which their surface can be modified [118].

Over the past few years, SLNs have been widely studied as a means of delivering anticancer drugs for breast cancer treatment [137, 138]. For example, ultrasound technology has been used to prepare radiolabeled trastuzumab (TRZ)-loaded SLNs [139]. In vitro studies have shown that TRZ-SLNs are biocompatible and effective for inducing apoptosis in human MCF-7 adenocarcinoma cells. Moreover, parenteral injection of TRZ-SLNs into rats showed promising results in terms of SLNs serving as cancer diagnostic agents. Additionally, SLNs possess the dual properties of liposomes and nanoparticles, offering the advantages of low toxicity, good biocompatibility, and biodegradability. However, issues such as low drug loading and poor stability can arise owing to the complex internal structure of SLNs, which consists of multiple phases. Problems such as excessive drug loading leading to gelation, particle size growth, and drug degradation during storage limit their widespread application.

Hydrogels

Introduction to hydrogels

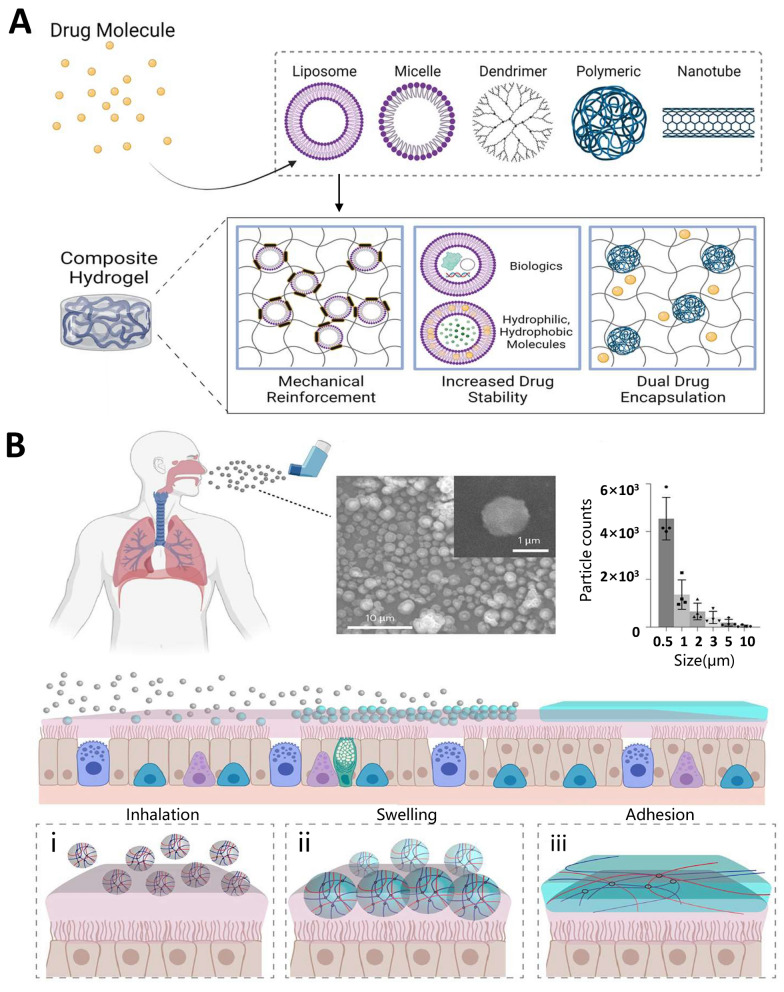

Hydrogels are formed by polymers, creating a three-dimensional network in water through cross-linking and possessing the ability to rapidly absorb a significant amount of water while maintaining their volume without dissolution [140]. The capacity of the hydrogel to absorb water is attributed to the hydrophilic functional groups on its polymer backbone. Additionally, its insolubility in water is a result of cross-linking of the network chains. Hydrogels have garnered significant attention in the fields of immunomodulation and vaccine development owing to their unique physicochemical properties. These properties include high water content, drug-carrying capacity, biodegradability, biocompatibility, and ease of construction and manipulation (Fig. 3A) [119]. The physical properties of hydrogels are conducive to vaccine delivery, which allows the precise delivery of high doses of non-specifically distributed drugs to specific sites while achieving the sustained and controlled release of drug molecules [120, 121].

Fig. 3.

Hydrogel. A Nanocarrier-hydrogel composites for vaccine delivery. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [119], Copyright 2019, Applied Materials Today. B Changes in the contact process of the inhalable bioadhesive hydrogel with the mucus surface. Dry SHIELD particles (grey spheres) are inhaled and they become swollen (blue spheres) once they are in contact with the mucus layer (pink layer). Finally, it forms a layer of hydrogel (blue layer) and adheres to the mucus layer. The process includes inhalation (i), swelling (ii) and adhesion (iii). The representative SEM image showing the morphology of SHIELD particles before swelling. The inset shows a zoomed-in view of one particle. Aerodynamic diameter of SHIELD particles. Data are mean ± s.d.; n = 4 independent experiments. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [143], Copyright 2023, Nature Materials

Types and applications of hydrogels

Reformulated hydrogels, which are composed of a blend of natural and synthetic materials, have demonstrated efficacy as carriers for vaccine delivery. Recent advancements in artificial modifications have resulted in improved hydrogel compositions and extended-release cycles for vaccines. Furthermore, the antiviral ability of hydrogels can be enhanced by combining antiviral components. Additionally, hydrogels can be designed as gel microspheres, injectable hydrogels, and gel films to cater to various applications [141, 142]. For example, mucous membranes are the first line of defense of the immune system and often rely on the mucus barrier to provide protection when viruses invade the body through the respiratory tract. To enhance the mucus barrier, an inhalable bioadhesive hydrogel against SARS-CoV-2 infection was prepared, which was made of food-grade materials and could be conveniently delivered through a dry powder inhaler. This resulted in a dense hydrogel network that covered the respiratory tract and interacted with mucus, which ultimately enhanced its diffusion barrier properties and reduced viral penetration, which in turn enhanced lung protection (Fig. 3B) [143]. Some protein nanoparticles degrade very easily in the body and require multiple doses to ensure long-lasting immunity. The slow-release properties of hydrogels can solve this problem. Injectable hydrogels were prepared from CS and glycerophosphate, which were compounded with CPMV nanoparticles for slow release and prolonged immune stimulation [144]. Receptor binding domain (RBD) retention can be enhanced by utilizing injectable hydrogel scaffolds; the hydrogel acts as a persistent RBD reservoir and a localized inflammatory ecological niche for innate immune cell activation [145]. Until now, most vaccines have relied on cold chains for distribution and storage. To address this issue, a reversible PEG-based hydrogel platform was designed for the encapsulation, thermal stabilization, and on-demand release of biologics by borate cross-linking using novel hydrogel encapsulation technology, which can stabilize multiple types of biologics up to a high temperature of 65 °C to maintain their vaccine activity [146]. This advancement signifies a significant milestone in the efforts to mitigate the financial burden and potential risks associated with cold chains.

Hydrogel systems hold significant promise for vaccine delivery in light of their favorable biocompatibility, efficient loading of nucleic acid drugs, and capacity to target and regulate the release of antigens at a local level. The recent development of various stimulus-responsive hydrogels has enabled precise spatial and temporal control over vaccine delivery to disease sites or disease-related tissues, rendering it a prominent area of research [147]. Furthermore, hydrogels can be integrated with other delivery technologies such as nanoparticles and microneedles for diverse clinical applications. It is anticipated that the integration of new technologies and platforms will lead to the development of novel hydrogel drug delivery systems in the near future.

Microneedles

Introduction to microneedles

MNs consist of small tips connected to a base and typically have a body measuring 10–2000 µm in height and 10–50 µm in width. Their length, size, and shape can be customized based on the specific treatment requirements. MNs allow for puncturing of the skin and can be guided through the outermost layer to create tiny channels for vaccine delivery, enabling drugs to reach the underlying skin layers in a minimally invasive manner without causing damage to blood vessels and nerves in the dermis [148, 149]. When MNs are used for vaccine delivery, the drug is loaded into an array of MNs. These MNs induce a driving force by establishing a concentration gradient between the medication and subcutaneous tissue fluid. Consequently, the drug can be released in a sustained or controlled manner [122]. MNs offer stabilized transdermal absorption rates, convenient delivery, and the potential for more precise and rapid drug administration at stable dosages. They have considerable advantages in vaccine delivery applications owing to their minimally invasive, convenient, precise, and effective modes of action. In recent years, they have been widely used for pharmaceutical delivery and immunization [150].

Types and characteristics of microneedles

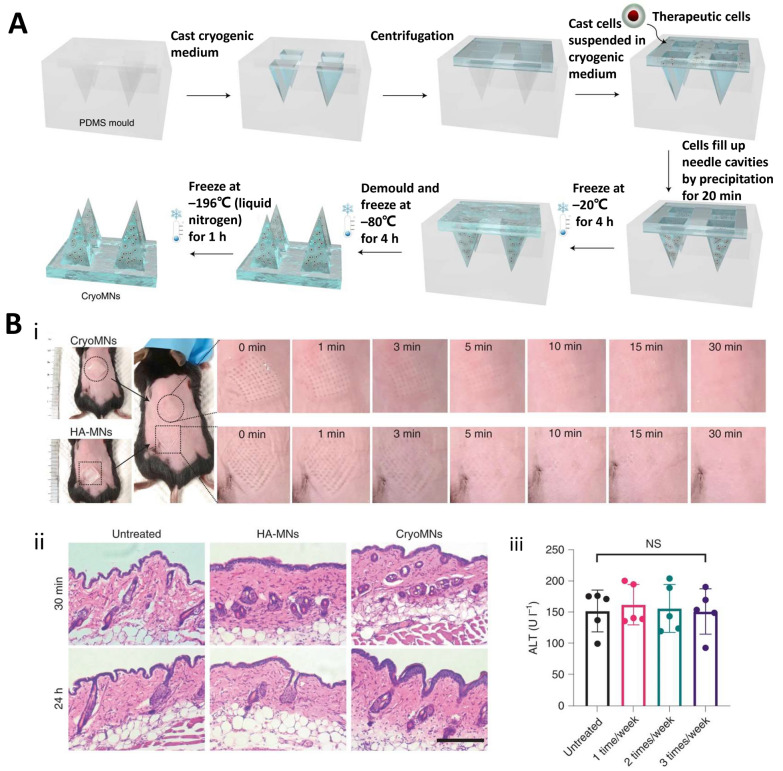

According to their transdermal mode of action, MNs can be categorized into many types, such as solid, encapsulated, dissolved, hollow, hydrogel, and frozen MNs [122, 123]. Solid MNs have high mechanical strength; after penetrating the skin stratum corneum to form microscopic pores, drugs are coated on the skin surface, which is conducive to promoting the local or systemic administration of drugs. In encapsulated MNs, drugs are encapsulated on the surface, and the drug enters the skin when the microneedles penetrate the stratum corneum. Dissolved MNs are made by microprocessing biodegradable polymers, which can be dissolved in the skin tissue after penetrating the skin, releasing the encapsulated drugs. Hollow MNs have hollow channels that act on the skin to provide dermal channels for vaccine delivery and tissue fluid extraction. Hydrogel MNs are composed of drug-loaded hydrogels; the hydrogel enters the skin and mixes with the tissue fluid to dissolve and release the loaded drug, with MN removal following drug administration. Frozen MNs (also known as cryomicroneedles [cryoMNs]) are a new concept of microneedling technology developed in the last two years. They were made using pre-designed MN molds optimized for cryogenic media with pre-suspended cells and further processed using a stepwise cryogenic micromolding method (Fig. 4A) [151]. CryoMNs have a high mechanical strength and can easily penetrate the skin and promote the proliferation of loaded live cells within the skin. CryoMN-delivered cells in mice maintained their viability and proliferative capacity, indicating their biocompatibility and safety (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Frozen microneedles. A Preparation of frozen microneedles. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [151], Copyright 2021, Nature Biomedical Engineering. B Evaluation of in vivo compatibility and safety of cryoMNs. (i) Assessment of skin recovery following application of frozen MN; (ii) Displaying skin H&E staining images at 30 min and 24 h post MN application, Scale bar, 200 μm; (iii) Showing images of skin stained with TUNEL (green) and Hoechst (blue) after MN application. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [151], Copyright 2021, Nature Biomedical Engineering

These MNs offer several advantages but also have some limitations [122]. For instance, while solid and encapsulated MNs demonstrate superior performance, the former are susceptible to needle breakage owing to their high mechanical strength, posing potential safety hazards. Additionally, the latter may not be suitable for drugs that require large dosages. Dissolved MNs and hydrogel MNs are simple to use and enable precise control over the release kinetics of drugs or biologics. However, the manufacturing materials of these two MNs have high requirements, including good biocompatibility. In addition, while hollow MNs can release drugs in a controlled manner and facilitate the delivery of large doses, their production cost is high, and the manufacturing process is challenging. Conversely, cryoMNs can be stored for several months under conventional storage conditions, making them easily transportable and usable, highlighting their clinical potential. The greatest clinical potential is the intradermal delivery of DC vaccines. However, many issues regarding the materials, production conditions, and drug-loading capacity need to be addressed.

Physicochemical properties of biomaterials affecting the immune response

Biomaterial-based vaccine delivery systems, particularly NPs, have been widely employed in vaccine research and development. The physicochemical properties of nanoparticles (including morphology and structure, particle size, surface charge, and antigen loading pattern) significantly influence vaccine adjuvancy and immune response [152].

Morphology and structure

The shape of a biomaterial affects its interaction with APCs or other immune cells, which in turn affects its adjuvant activity and immunization effects. Ellipsoidal particles can induce cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) more efficiently with greater antigen specificity and stronger in vivo stimulation of immune cells than spherical particles under the same synthesis conditions [153, 154]. Nanoparticles with artificial APCs have been developed for cancer immunotherapy. Non-spherical particles have a larger surface area and flatter T cell-engaging surfaces than spherical particles [155]. This property may enhance interactions with T cells and stimulate antigen-specific T cells more effectively, leading to antitumor efficacy in a murine melanoma model, which could not be achieved with spherical particles. However, such interactions between nanoparticles and immune cells cannot be generalized and may vary depending on the cell type, as demonstrated by studies showing that macrophages prefer the uptake of rigid and spherical nanoparticles over soft and cylindrical nanoparticles [156]. Additionally, spherical and larger particles are relatively easy to marginalize, whereas rod particles are more prone to extravasation in blood circulation (Fig. 5A) [157].

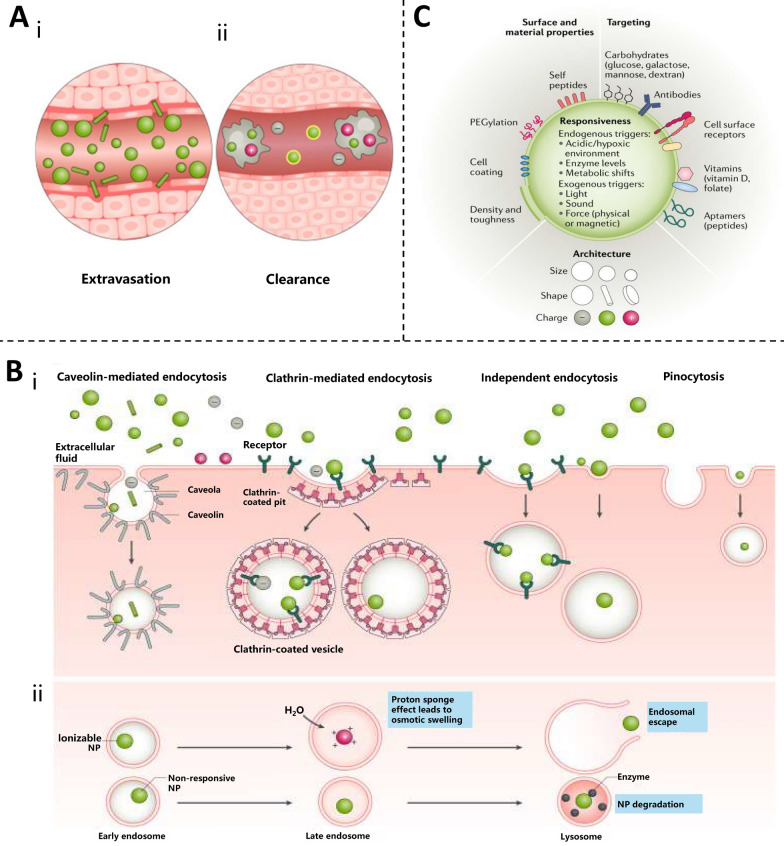

Fig. 5.

Physicochemical properties of biomaterials affecting immune response. A The influence distribution of NP characteristics. (i) Spherical and larger NPs marginate more easily during circulation, whereas rod-shaped NPs extravasate more readily; (ii) Uncoated or positively charged NPs are cleared more quickly by macrophages. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [158], Copyright 2021, Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. B Pathway and fate of NP uptake. (i) endocytosis of NP: upon interaction with the cell surface, NPs—depending on their surface, size, shape and charge—are taken up by various types of endocytosis or pinocytosis via non-specific interactions, such as membrane wrapping, or specific interactions, such as with cell surface receptors; (ii) Ionizable NPs contribute to endosome escape: responsive NPs—such as ionizable NPs that become charged in low-pH environments-aid in endosomal escape and allow for intracellular delivery whereas unresponsive NPs often remain trapped and are destroyed by lysosome acidity and proteolytic enzymes [158]. C NP surface characteristic design for enhanced delivery. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [158], Copyright 2021, Nature Reviews Drug Discovery

Particle size

The particle size of biomaterials varies from nanometers to micrometers or larger particles [1]. Although nanoparticles can reach hundreds of nanometers in size, biomaterial nanoparticles with particle sizes ≤ 25 nm are more likely to target antigen delivery to the lymph nodes, whereas larger particles are trapped at the injection site and internalized before being delivered to the lymph nodes by these APCs [159, 160]. The efficiency and rate of uptake of 50 nm polystyrene (PS) by macrophages and dendritic cells is much higher than that of 500 nm PS [161]. At the same time, APCs ingesting 50 nm PS particles expressed more co-stimulatory markers than those ingesting 500 nm particles. In additional reports employing antigen-coated PS rods and spheres of various sizes, smaller spherical particles promoted adjuvant Th1 immune responses [162]. In contrast, longer rod-shaped particles tended to promote Th2 immune responses rather than thicker particles. This may be because longer particles present denser antigens and a larger surface area, which are conducive to attachment or internalization by cells. These results indicate that particle size is a key factor in the immune system, such as transport, uptake, and activation of APCs, and affects the clinical application of drugs.

Surface property effect

The surface charge of nanoparticles is crucial for determining their interaction with and uptake by immune cells. Immune cells showed a greater tendency to internalize positively charged NPs. Additionally, they appear to have the ability to escape lysosomes after internalization and localize to the perinuclear region. Meanwhile, nanoparticles with negative and neutral charges tend to colocalize within lysosomes [163]. For example, PS particles with diameters of ≤ 0.5 μm were most readily absorbed by DCs using an in vitro model [164]; however, the uptake of larger particles (such as those with a diameter of 1 μm) by DCs was greatly enhanced by transforming the surface of the particles into a positively charged one. In the presence of macrophages, positively charged and uncoated particles tend to be eliminated the fastest [165]. In addition to charge, the antigen loading pattern also affects the immune response [166]. Three PLGA nanoparticles were synthesized, each with unique surface charges and antigen loading patterns, and were loaded with ovalbumin (OVA). Two of the nanoparticles encapsulated antigens using Angelica polysaccharides and PEI, whereas the remaining nanoparticles were designed to adsorb antigens onto the PEI-coated surface. Antigen-encapsulated nanoparticles induced a stronger and longer-lasting antigen-specific antibody response than nanoparticles with adsorbed antigens in vivo [156].

In summary, the physicochemical properties of NPs (including morphology, structure, particle size, and surface properties) have an impact on vaccine delivery and immunization effects, which may not be caused by a single factor alone; other factors need to be considered. Nanoparticles can be absorbed by cells in various ways, but their fate is not the same. During endocytosis, the stability of nanoparticles is extremely easily destroyed by the low pH environment of endosomes, and the design of ionizable materials can effectively prevent the degradation of NP by acidic conditions and facilitate the escape of endosomes (Fig. 5B) [158]. For example, negatively charged PLGA nanoparticles can be transformed into neutral or positively charged NPs by means of surface modifications such as polyethylene glycolization or CS coating to break through the RES biological barrier and facilitate vaccine delivery [15]. Therefore, the physicochemical properties of NPs can be altered to improve their suitability for vaccine development, and intelligent design is of great significance for enhancing delivery capabilities and immune effects (Fig. 5C).

Vaccine delivery routes related to biomaterials

Receiving a vaccine via different administration routes can significantly impact its effectiveness owing to variations in the local environment, antigen distribution and presentation, and the resulting immune response. Therefore, it is crucial to understand and plan vaccination routes, especially with the emergence of new diseases and the lack of effective vaccines against many untreatable pathogens, which urgently necessitates the development of innovative vaccination strategies.

Injections

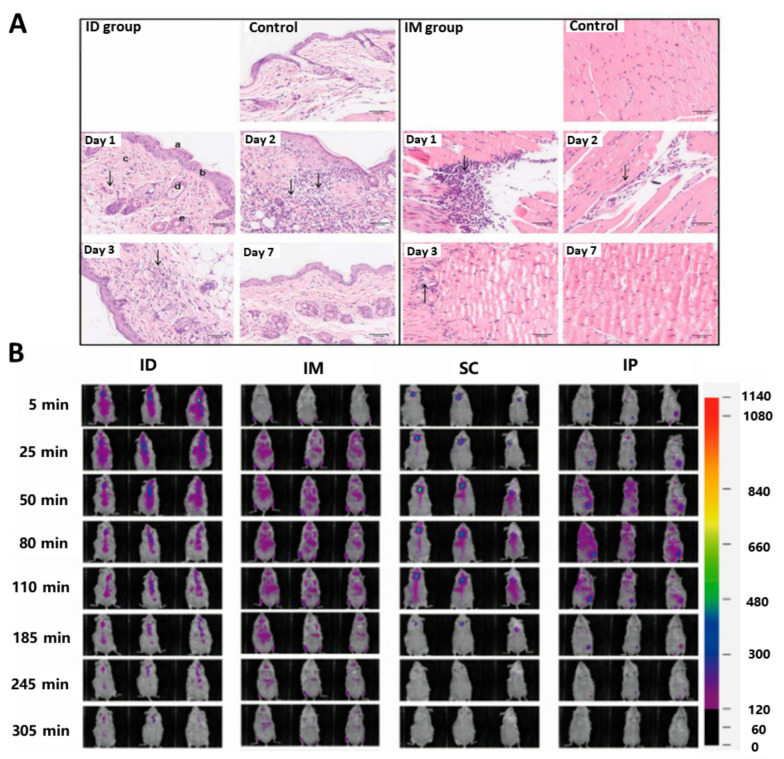

Injections are the most common form of vaccination and are generally categorized as intradermal, subcutaneous, intramuscular, intravenous, or intraperitoneal. Injections usually require puncturing of the skin surface to deposit the drug deep into the subcutaneous or muscle tissue; therefore, this injection method can be cumbersome and painful. Moreover, injections can easily cause local infections and adverse reactions; nevertheless, this type of vaccine delivery is accurate and direct and provides rapid systemic action and absorption [167]. As such, injections have been widely used in various drug therapies, including those used to deliver sedatives, antiemetics, hormones, analgesics, and immunizations [168]. Currently, intramuscular and subcutaneous injections are used clinically for vaccinations. It is important to note that intramuscular injection (IM) has been shown to be more effective than needle-free injection technology-based intradermal injection (ID) in stimulating antibody production (Fig. 6A) [169]. This phenomenon may be attributed to the more pronounced tissue damage caused by intramuscular injection, resulting in accelerated blood circulation within the muscle and recruitment of a greater number of inflammatory cells. The study also found that the longer the antigen is deposited at the site, the more favorably it enhances the uptake of antigens by APCs. Both intramuscular and intradermal injections have a great advantage in this regard (Fig. 6B) [169]. Recently, researchers have uncovered that intravenous injection nanocrystals (INCs) possess inherent potential in anti-tumor applications due to their high drug loading, low toxicity, and controllable size. This discovery holds promise for addressing the current challenges of dissolution, bioavailability, and toxicity in vaccine delivery [170].

Fig. 6.

Inoculation by injection. A In order to investigate the local inflammatory response that occurred in skin and muscle following ID and IM administration routes, hematoxylin and eosin staining was conducted on days 1, 2, 3 and 7 after inoculation. Analysis of histological changes in skin tissue and muscle tissue at different time points following administration. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [169], Copyright 2023, International Journal of Molecular Sciences. B Investigation into the local retention and diffusion dynamics of the model antigen Cy7-OVA after injection into ICR mice via different routes. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [169], Copyright 2023, International Journal of Molecular Sciences

Pain associated with vaccination has always been one of the reasons why many patients are afraid of receiving vaccinations. To alleviate the pain and fear of needles, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended that vaccination be promoted more effectively by introducing as many pain-modifying or pain-reducing regimens as possible [171]. As such, future research efforts should focus on evaluating the efficacy and feasibility of these regimens associated with injections to improve patient experience and vaccination rates.

Transdermal immunization

Transdermal vaccination involves the application of antigens to the skin to facilitate efficient transportation to immune cells in the skin for a rapid and effective immune response. However, it is challenging to penetrate the outermost layer of the skin known as the stratum corneum. Additionally, poor uptake of free antigens and chemokines by cells further limits the efficacy of transdermal immunization. Various adjuvants and delivery systems have been developed using different physical and chemical methods to enhance immune response without the need for needles. The previously mentioned MN patch is an increasingly popular technique for transdermal vaccine delivery within the medical field, as it effectively delivers antigens to APCs in the epidermal and mucocutaneous compartments [172].

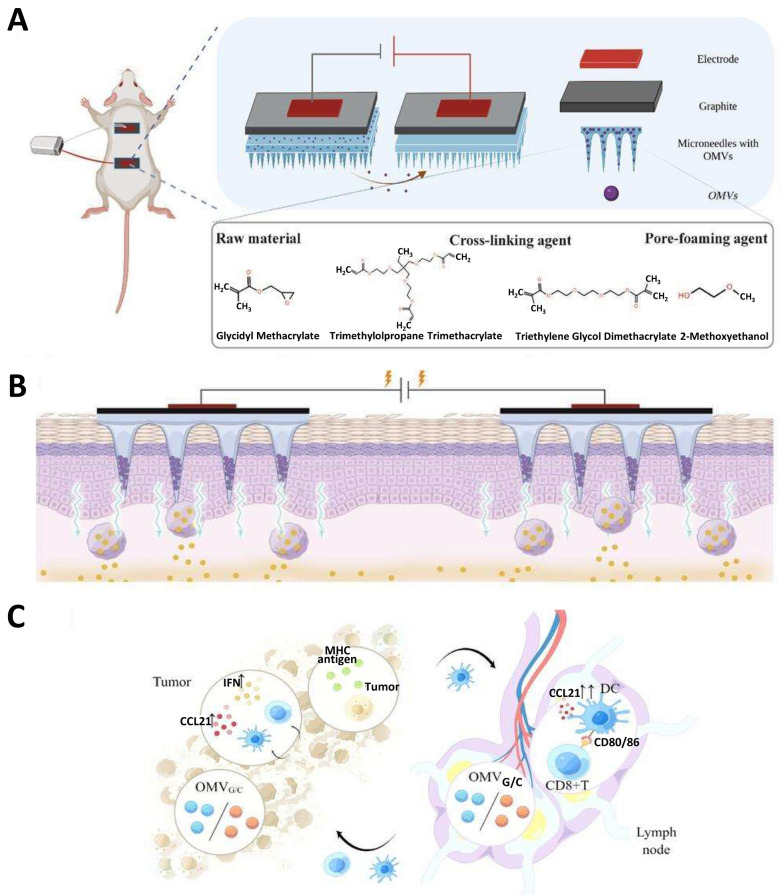

In recent years, iontophoresis therapy in combination with MNs has further increased transdermal drug penetration [173]. This was used to construct a triple platform of IPMN-GC electrons-MN-exosomes for the transdermal delivery of antigens and chemokine proteins for the painless inoculation of skin tumors and cancer vaccines [174] (Fig. 7A). A pair of MN patches were combined by iontophoresis using electrical currents to introduce ionic medicinal compounds into the body. A secure voltage can be applied to MN patches to facilitate the penetration of negatively charged vesicles into the dermis. This can be achieved by incorporating a graphite layer into the patches, rendering them electrically conductive (Fig. 7B). The MN patch vaccination elicited a robust immune response in mice, leading to the activation of numerous T cells, suggesting that IPMN-GC significantly augmented the T cell-mediated immune response for cancer suppression (Fig. 7C). Overall, transdermal immunization has a promising future as an excellent vaccination route. Compared with oral administration, transdermal immunization can bypass the metabolism of drugs in the digestive system and allow for sustained drug release. Compared with intramuscular injection, it reduces pain and improves adherence in elderly and infant patients.

Fig. 7.

Percutaneous immunization. A Composition and structure of MN. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [174], Copyright 2023, Small Science. B IPMN-G or IPMN-C facilitates transdermal delivery of gp100 and CCL21. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [174], Copyright 2023, Small Science. C Schematic of Anti-tumor mechanism of IPMN-GC in vivo. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [174], Copyright 2023, Small Science

Intranasal administration

Administering vaccines through nasal tissues is a highly effective method because it enables lower injection doses and prevents the drug from being exposed to extreme pH or digestive enzymes, offering distinct advantages. The mucosal layer is the human immune system's first barrier of defense, and intranasal antigens can block infection and transmission of respiratory pathogens at the point of entry by inducing the production of IgA antibodies and the initiation of T cells in nasal tissues, which in turn induces local mucosal immunity and systemic humoral responses [175, 176].

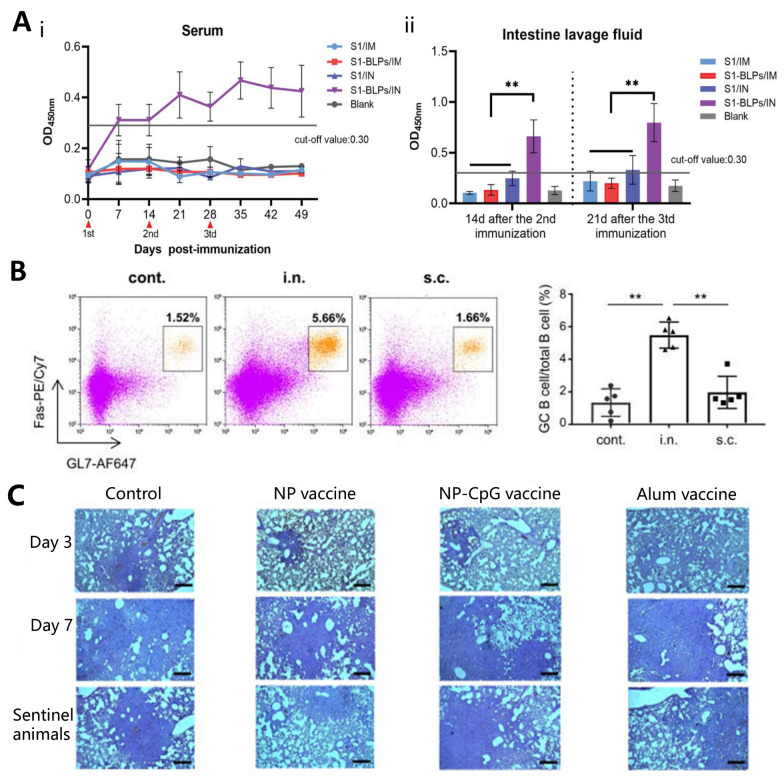

Recently, specific IgA antibodies were detected in the serum and lavage fluid of mice that were inoculated by intranasal administration of bacterial-like particles (S1-BLPs) but were not injected intramuscularly to develop a mucosal vaccine against porcine epidemic diarrhea virus [177]. This demonstrates that intranasal administration of S1-BLPs is effective in stimulating a specific secretory IgA response in the intestinal mucosa (Fig. 8A). Nagisa et al. [178] immunized mice subcutaneously or intranasally with SARS-CoV-2 inactivated whole-virion (WV) as an antigen and assessed the percentage of germinal center B cells in the nasal passages out of the total B cells by flow cytometry (Fig. 8B). Intranasal administration of inactivated WV triggers strong production of S protein-specific IgA in the nasal mucosa.

Fig. 8.

Intranasal administration. A IgA levels in serum and the quantity of IgA secreted in lavage solution were evaluated using ELISA. (i) The temporal changes of specific IgA in serum; (ii) Specific secretory IgA in small intestinal lavage fluid were analyzed. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [177], Copyright 2023, Frontiers in Immunology. B The proportion of germinal center (GC) B cells within nasal B cells was assessed using flow cytometry. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [178], Copyright 2023, Frontiers in Immunology. C Histological examination showed pathological changes in the lung tissue of the animals on days 3 and 7 post-attack. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [181], Copyright 2023, Scientific Reports

In conclusion, intranasal administration represents a needle-free method for vaccine delivery that circumvents the blood–brain barrier and mitigates systemic adverse reactions. For instance, Ruan et al. [179] developed a nasal-to-brain delivery system capable of swiftly detaching microneedles from their base, thereby reducing administration time and enhancing drug transport to the brain. Intranasal administration also offers practical advantages in terms of cost and ease of management; however, notably, its efficacy may vary depending on the duration of drug retention. This issue can be mitigated by employing chitosan, which offers advantages in adhesion to mucous membranes, or by utilizing lectins [180]. Mice challenged with wild-type SARS-CoV-2 were effectively protected by an intranasal vaccine containing SARS-CoV-2 spiny receptor-binding domain protein encapsulated in mannose-conjugated CS nanoparticles, as demonstrated by significant reductions in body weight loss, lung viral load, and lung pathology (Fig. 8C) [181]. Enhanced binding of CS to the nasal epithelial surface extends its retention, resulting in increased drug availability for absorption.

Oral administration

Oral administration is a standard needleless technique specifically used to treat influenza, polio, rotavirus, typhoid, cholera, and other diseases [182]. Compared with injections, oral administration is milder, cheaper, and less likely to cause damage to the skin or mucous membranes. Furthermore, oral administration can provide local or systemic delivery of a broad range of drug molecules (from small molecules to biomolecules) and is frequently considered the preferred delivery route.

Despite the obvious advantages of the oral route of administration, only a few vaccines are currently available in oral formulations because oral administration remains challenging owing to the complex environment of the human gastrointestinal tract. These challenges include poor drug stability, poor solubility, and low drug permeability across the mucosal barrier. For example, antigens should propagate intact into the intestinal lumen without degradation by the acidic stomach environment [183, 184]. Damage to the digestive system can reduce the immune response generated by vaccines and their ability to protect themselves against pathogens. Therefore, it is crucial to develop new vaccine carriers that can withstand the acidic conditions of the stomach, remain in the small intestine, and be released effectively. Simultaneously, the adjuvant capacity of the delivery vector should be further optimized [185]. To address these concerns, a safe genetically modified rice vaccine has been developed that can withstand the acidic environment of the stomach [186]. In addition, there have been advancements in the development of oral rice-based vaccines for allergies, cholera, and diarrhea [187–189]. In a separate study, Oliveira et al. [190] utilized CS nanoparticles to deliver a plasmid DNA vaccine encoding the Rho1 GTP protein of Schistosoma mansoni. In vivo experiments demonstrated that oral administration could potentially alleviate liver pathology by upregulating the expression of regulatory IL-10. Yagnik et al. [191] engineered a recombinant form of Lactococcus lactis to express Shigella dysenteriae type 1 protein A in the outer membrane. The immune response elicited by oral administration was significantly stronger than that induced by intranasal administration. Overall, these findings suggest that oral vaccines have a promising potential for the prevention of various diseases.

This section mainly discusses the different vaccination methods, and their application, advantages and disadvantages are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Application, advantages and disadvantages of different vaccination routes

| Vaccination routes | Application | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injections | Sedatives, antiemetics, hormone therapy, analgesics and vaccinations | Administration is accurate and direct, providing rapid systemic action and absorption | It is more troublesome and makes patients feel stronger pain, and it is easy to cause local infection and adverse reactions | [167, 168] |

| Transdermal immunization | Cosmetic skin, vaccination, disease chemotherapy, biological therapy, immunotherapy, and gene therapy | Avoid first pass effect, eliminate adverse reactions, improve vaccine stability, increase patient compliance | The stratum corneum of the skin is difficult to penetrate | [172, 173] |

| Intranasal administration | Central nervous system diseases, pain management, hormone replacement therapy, vaccinations, and treatment of special diseases | Reduce injection dose, activate mucosal immunity and bypass blood–brain barrier | The effect is often different due to the length of residence of the drug | [175, 176] |

| Oral administration | Vaccines for influenza, polio, rotavirus, typhoid, cholera and other diseases | Convenient administration, stronger immune response, high compliance | The stability and solubility of the drug were poor, and the permeability of the drug through the mucosal barrier was low | [182–184] |

Design considerations for biomaterials used in vaccine adjuvants

Autoimmune diseases, inflammatory disorders, and organ and tissue graft rejection are underpinned by adverse immune responses at the cellular, tissue, and systemic levels, and biomaterials offer powerful opportunities to control interactions at these levels to promote immune tolerance for selective control of inflammation [192]. A highly important aspect of immune system regulation is ensuring that proper signals reach the appropriate immune cells at the right time, dosage, and location. The varied utilization of biomaterials can effectively stimulate the immune system and prevent uncontrolled systemic immune reactions, thereby addressing these challenges [13]. Biomaterials are currently extensively utilized as adjuvants in vaccines to improve the efficacy, quality, and longevity of vaccine responses. The better the design of these biomaterials, the greater their potential to extend and improve the functionality of the vaccine.

Prerequisites for biomaterials as adjuvants

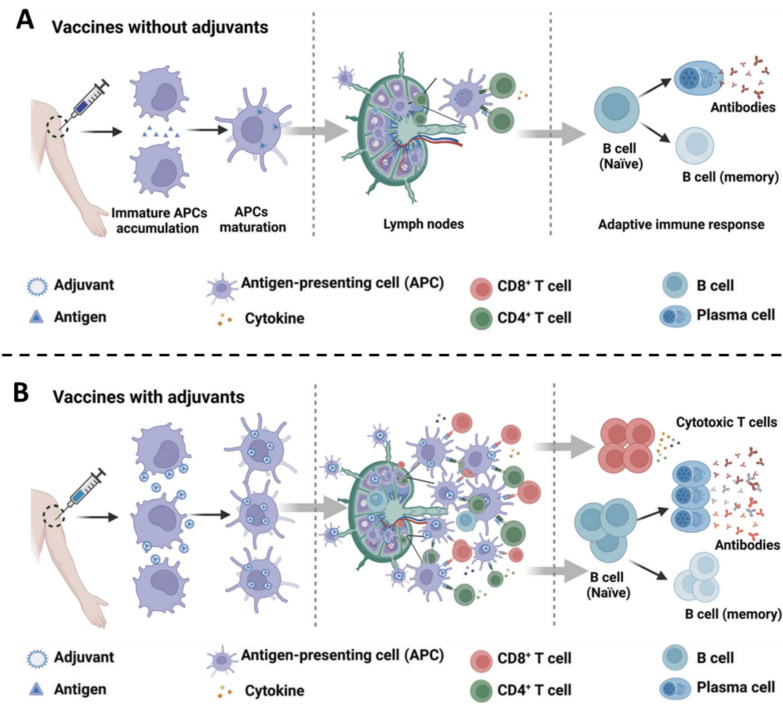

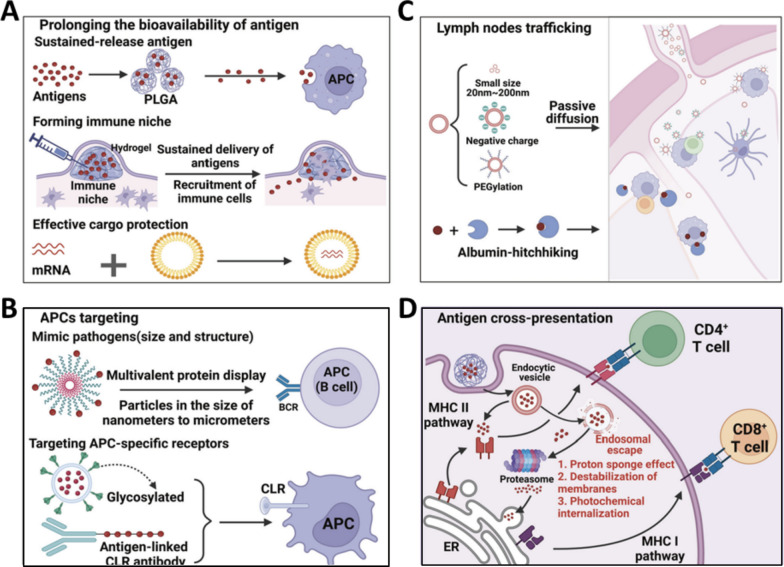

Reinforcing adjuvants have the potential to boost the adaptive immune response of vaccines by promoting the activation of cells in the innate immune system [193]. Some prerequisites must be met for DCs to effectively activate the innate immunity. First, the adjuvant must effectively deliver antigenic targeting to DCs, and second, DCs must be activated to release antigens for further antigen processing and presentation [194]. The particulate biomaterial itself is readily phagocytosed by DCs; however, it is also readily phagocytosed by surrounding macrophages, a situation that would result in ineffective activation of naïve T cells. Therefore, we can expect improved efficacy by preferentially targeting biomaterial adjuvants to DCs in vivo. For instance, nanoscale particles can migrate and concentrate in DC-rich lymph nodes [195]. Additionally, they can release chemokines or cytokines to recruit DCs to the injection site and stimulate a specific immune response [196, 197]. Furthermore, the use of liposome-encapsulated antigens and immunomodulatory factors to target antigens and maturation signals directly to DCs in vivo improves DC uptake and generates immunity [198, 199].