Abstract

Infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV) is a Novirhabdovirus and is the causative agent of a devastating acute, lethal disease in wild and farmed rainbow trout. The virus is enzootic throughout western North America and has spread to Asia and Europe. A full-length cDNA of the IHNV antigenome (pIHNV-Pst) was assembled from subgenomic overlapping cDNA fragments and cloned in a transcription plasmid between the T7 RNA polymerase promoter and the autocatalytic hepatitis delta virus ribozyme. Recombinant IHNV (rIHNV) was recovered from fish cells at 14°C, following infection with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the T7 RNA polymerase (vTF7-3) and cotransfection of pIHNV-Pst together with plasmids encoding the nucleoprotein N (pT7-N), the phosphoprotein P (pT7-P), the RNA polymerase L (pT7-L), and the nonvirion protein NV (pT7-NV). When pT7-N and pT7-NV were omitted, rIHNV was also recovered, although less efficiently. Incidental mutations introduced in pIHNV-Pst were all present in the rIHNV genome; however, a targeted mutation located in the L gene was eliminated from the recombinant genome by homologous recombination with the added pT7-L expression plasmid. To investigate the role of NV protein in virus replication, the pIHNV-Pst construct was engineered such that the entire NV open reading frame was deleted and replaced by the genes encoding green fluorescent protein or chloramphenicol acetyltransferase. The successful recovery of recombinant virus expressing foreign genes instead of the NV gene demonstrated that the NV protein was not absolutely required for viral replication in cell cultures, although its presence greatly improves virus growth. The ability to generate rIHNV from cDNA provides the basis to manipulate the genome in order to engineer new live viral vaccine strains.

In the field of aquaculture, diseases related to the presence of almost endemic pathogenic agents account for a large proportion of economic loss. Farmed rainbow trout especially are one of the examples of viral diseases posing a serious threat to European salmonid output. Two nonrelated rhabdoviruses predominantly affect farmed salmonids worldwide: viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) and infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV). Vaccination is, generally speaking, the most efficient way to protect animals against viral disease. However, for fish, the route for vaccine administration is ideally by bath immersion, since the delivery of a vaccine by injection is time-consuming and has the disadvantage of requiring individual administration to yearling fishes. Furthermore, the waterborne route implies the use of a replicating vaccine, such as attenuated viral strains generated by successive passages in tissue culture or escaped mutants selected with specific neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) (2, 22). Other strategies, like the use of protective recombinant proteins, have been set aside, mainly due to the low cost-effectiveness and restraints on individual injection of young fish (15). DNA immunization has also proven to be efficient in fish, but again vaccination must be by injection (4).

Similar to mammalian rhabdoviruses, the IHNV virion structure is composed of a roughly 12-kb negative single-stranded RNA tightly associated with a nucleoprotein, N; a polymerase-associated protein, P; an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, L; a matrix protein, M; and a glycoprotein, G, which induces the synthesis of neutralizing antibodies in infected fish (14). An additional gene, located between the G and L cistrons, codes for a nonstructural NV protein (1, 12) whose role is unknown; the genus name Novirhabdovirus is derived from the NV gene. The entire nucleotide sequences of the IHNV genomes of two virus strains have been determined: the American WRAC strain isolated in southern Idaho, which is 11,131 nucleotides (nt) long (16); and the European 32/87 strain, isolated in France, which is 11,137 nt long (20). Both sequences shared 98.2% identity, with the major differences between both sequences being a short deletion (8 nt) in the intergenic N-P region for the WRAC sequence and a deletion of the proximal A-C dinucleotides at the 5′ end (genomic sense) for the 32/87 strain.

Reverse genetics applied to the negative-strand RNA virus, as first described for the rabies virus (19) and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) (13, 21), has opened the way to new perspectives for the generation of safe vaccines. The ability to generate infectious virus derived from cDNA is a very powerful approach, since the viral genome can be manipulated to generate attenuated vaccine strains and also makes the introduction of genetic tags feasible, allowing discrimination between field and the vaccine strains. Moreover, an extra gene can be stably introduced into the viral genome, and thus negative-strand RNA virus could be used as a gene vector (5, 17).

To evaluate the feasibility of generating a live attenuated viral vaccine strain to prevent IHNV in the field, we have developed a reverse genetic system for IHNV allowing recovery of genetically tagged infectious virus through cDNA transfection into fish cells. We show that the recombinant virus replicates in cell culture and in fish as well as the wild-type virus. Moreover, recombinant viruses lacking the NV gene were generated, and the role of the NV protein in the viral replication cycle was investigated. This is the first report of reverse genetics of a nonmammalian rhabdovirus replicating at low temperatures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cell cultures.

The IHNV 32/87 strain, a French strain isolated in our laboratory in 1987 from rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss, was propagated in monolayer cultures of EPC cells at 14°C as previously described (6). Recombinant vaccinia virus expressing T7 RNA polymerase, vTF7-3 (7), was kindly provided by B. Moss.

Viral RNA preparation.

EPC cells were infected with IHNV and incubated at 14°C. When the cytopathic effect was total, the supernatant was collected and then clarified by low-speed centrifugation, and virions were pelleted at 60,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C in a Beckman TL 100 ultracentrifuge. The pellet was resuspended in TEN buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 0.5 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl), and the viral RNA was recovered with the QIAamp viral RNA purification kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Construction of full-length antigenomic copies of the IHNV genome.

A full-length cDNA copy of the IHNV RNA genome was constructed by assembling four overlapping cDNA clones generated through reverse transcription (RT)-PCR with specific primers (Table 1) as depicted in Fig. 1. Purified RNA (2 μg) was mixed with 50 pmol of T7IHN primer and incubated for 5 min at 70°C, 25 min at 60°C, and then 5 min at 37°C for denaturing and annealing steps. Then 5 μl of 5× first-strand buffer II, 1 μl of 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 2 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol, 1 μl of RNasin (40 U/ml; Promega), and 2 μl of Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Gibco/BRL) were added to the RNA. Synthesis of cDNA was conducted at 44°C for 1 h and 30 min at 51°C to minimize the formation of RNA secondary structures. The reaction mixture was then diluted with H2O to 100 μl. For the amplification reactions, 1 μl of the cDNA and 1 μl of specific primers (50 pmol each) were added to 15 μl of 3.3 × XL buffer, 2 μl of 25 mM Mg(OAc)2, 1 μl of 10 mM dNTP mixture, 1 μl of rTth DNA polymerase (XL PCR kit; Perkin-Elmer) in a total volume of 50 μl. The PCRs were conducted on a GeneAmp PCR System 2400 (Perkin-Elmer) as follows: 1 min at 94°C and then 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 4 min at 72°C for 35 cycles and a final extension reaction for 7 min at 72°C. The pairs of primers used (Table 1) were T7IHN/T7IHNR for fragment 1, EaIHN/EaIHNR for fragment 2, PsIHN/PsIHNR for fragment 3, and KpIHN/KpIHNR for fragment 4. KpIHNR contained the two additional A and C nucleotides missing in the published sequence (20).

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a | Location | Restriction site |

|---|---|---|---|

| T7IHN | tccccgcggtaatacgactcactatagGTATAAGAAAAGTAACTTGACTAAGC | 1–26 | SacII |

| T7IHNR | ggcCGGCCGGATGGATGGGTGAGTGAGAGACGGCC | 2853–2883 | EagI |

| EaIHN | ggcCGGCCGGACCCAACCCTCCTCCATCCCCAGAG | 2878–2908 | EagI |

| EaIHNR | gcCTGCAGACAGTGAGTAATTTAGGGGTGAGTTG | 5078–5109 | PstI |

| PsIHN | gcCTGCAGAACTGACAGACCGCATGACCCCCAG | 5104–5134 | PstI |

| PsIHNR | gcGGTACCATCCCGATGTATTTCCACTGGTACG | 7097–7127 | KpnI |

| KpIHN | gcGGTACCATTCCAGAACAAGAGTCCCGTCGTATC | 7122–7154 | KpnI |

| KpIHNR | gcgccggctacGTATAAAAAAAGTAACAGAAGGGTTC | 11106–11131 | NaeI-SnaBI |

| IHN N5 | ctcgaggctagcGATCACGAACGATGACAAGCG | 164–184 | NheI |

| IHN N3 | ggatccgctgagcGTGTTCAGTGGAATGAGTCGG | 1334–1354 | Bpu1102I |

| IHN P5 | ctcgagtctagaCAACAATGTCGAATGGAGAAG | 1461–1481 | XbaI |

| IHN P3 | ggatccgctgagcGCCTATTGACCTTGCTTCATG | 2140–2160 | Bpu1102I |

| IHN Nv5 | ggtctagaATGGACCACCGCGACATAAACACG | 4595–4618 | XbaI |

| IHN Nv3 | gggctgagcCCTATCTGGGATAAGCAAGAAAGTC | 4907–4930 | Bpu1102I |

| IHN L5 | ctcgaggctagcGAAAGATGGACTTCTTCGATC | 5011–5031 | NheI |

| IHN L3 | ggatcccgggGTGTACCTATTGTTCGCCTAGTG | 10960–10982 | SmaI |

Italicized letters indicate restriction site enzymes, capital letters indicate the IHNV sequence, and boldface letters indicate the T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence.

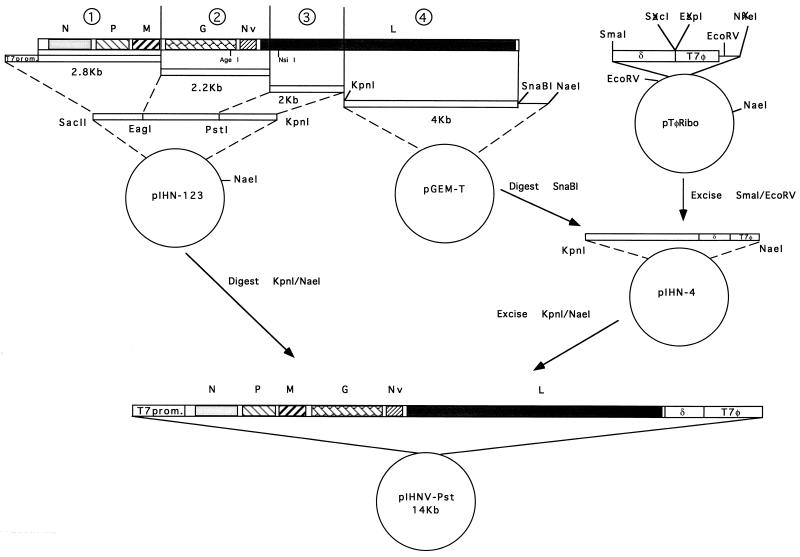

FIG. 1.

Construction of the full-length infectious pIHNV clone. Four overlapping cDNA fragments (numbered 1 to 4) covering the full-length IHNV RNA genome were generated by RT-PCR with primers described in Table 1 and assembled in a pBlueScript plasmid backbone as described in Materials and Methods. Restriction enzyme sites used for the construct were all present in the original sequence (20), with the exception of the PstI site. The pTφRibo plasmid which served for the insertion of fragment 4 has been described previously (3). T7prom., T7 RNA polymerase transcription promoter; T7φ, T7 RNA polymerase transcription terminator; δ, antigenome hepatitis delta virus ribozyme sequence.

PCR products were gel purified and inserted step by step in pBlueScript SK following appropriate restriction enzyme digestion (Fig. 1) following the fragment order 1, 2, and 3, leading to pIHN-123. PCR fragment 4 was first inserted into the pGEM-T vector (Promega) and fused to the hepatitis delta ribozyme (δ) and T7 transcription termination (φ) sequences following SnaBI digestion and ligation to the SmaI-EcoRV insert derived from the pTφRibo plasmid (3). Fragment 4 was then inserted into the pIHN-123 construct, following KpnI-NaeI restriction enzyme digestion (which removed the T7 promoter sequence from the pBlueScript backbone) and ligation, leading to the final pIHNV-Pst construct. An additional pIHNV construct was engineered in which the PstI site is removed. That was done by exchanging the AgeI-NsiI fragment (covering the PstI site [Fig. 1]) with a AgeI-NsiI fragment generated by RT-PCR from the IHNV RNA genome.

Construction of T7 expression plasmids encoding N, P, NV, and L proteins.

The open reading frames (ORFs) of the IHNV genes encoding nucleoprotein N (1,176 bp long), phosphoprotein P (693 bp long), nonstructural NV protein (336 bp long), and RNA polymerase L (5,958 bp long) were recovered by PCR from the pIHNV plasmid by using their specific respective primers (Table 1). PCR products were digested with either XbaI-Bpu1102I, NheI-Bpu1102I, or NheI-SmaI, gel purified, and inserted into the pET-14b vector (Novagen) digested with XbaI and Bpu1102I restriction enzymes, leading to the pT7-N, pT7-P, pT7-NV, and pT7-L plasmids. In these constructs, the IHNV coding regions were inserted between the T7 promoter and T7 terminator sequences. Expression of the corresponding IHNV proteins was checked by analysis of in vitro-translated products (TNT-T7-coupled system; Promega) by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10% polyacrylamide).

DNA transfection and IHNV recovery.

EPC cell monolayers in six-well plates (4 × 106 cells/well) were infected with the recombinant vaccinia virus (7) vTF7-3 (multiplicity of infection of 5) for 1 h at 37°C. Cell monolayers were washed twice and transfected with a mixture of pIHNV-Pst or pIHNV (0.5 μg), pT7-N (0.5 μg), pT7-P (0.2 μg), pT7-L (0.2 μg), and pT7-NV (0.125 μg) by using the Lipofectamine reagent (Gibco-BRL) according to the supplier's instructions. In some experiments, pT7-N and pT7-NV were omitted (see Results). Cells were incubated for 7 h at 37°C and then shifted to 14°C for 6 days. Cells were suspended in the supernatant by scratching with a rubber policeman and then submitted to two cycles of freezing and thawing. Supernatant P0 was clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 × g in a microcentrifuge and used to inoculate fresh cell monolayers in 12-well plates at 14°C. Three or 4 days after infection, the supernatant P1 from cultures exhibiting visible foci of infected cells either by visual examination or through immunofluorescence staining with an anti-G MAb, were collected and passaged once more. Supernatant P2 was then used to produce a high-titer stock of recombinant IHNV (rIHNV).

RT-PCR.

RNA of rIHNV was directly extracted from the P2 supernatant by using the QIAamp viral RNA purification kit (QIAGEN) and analyzed by RT-PCR to demonstrate the presence of the targeted mutations in the N, M, and L genes. A similar experiment was done in parallel with RNA extracted from the wild-type IHNV (wtIHNV). PCR products were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel with or without restriction enzyme digestion and were also subjected to nucleotide sequencing.

Construction of pIHNV-ΔNV, pIHNV-CAT, and pIHNV-GFP plasmids.

The IHNV cDNA fragment 2 (EagI-PstI) in the pBlueScript plasmid (see Fig. 3) was used to create, by site-directed mutagenesis with the QuickChange kit (Stratagene), unique SpeI and SmaI restriction enzyme sites surrounding the NV ORF. Thus, the entire NV ORF was deleted by SpeI-SmaI digestion and replaced with chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) or green fluorescent protein (GFP) ORFs, which were recovered by PCR from the pCAT (Promega) or peGFP-C1 (Clontech) plasmids. The AgeI-PstI fragment was removed from the full-length pIHNV-Pst construct by restriction enzyme digestion and replaced by the modified AgeI-PstI counterparts from fragment 2.

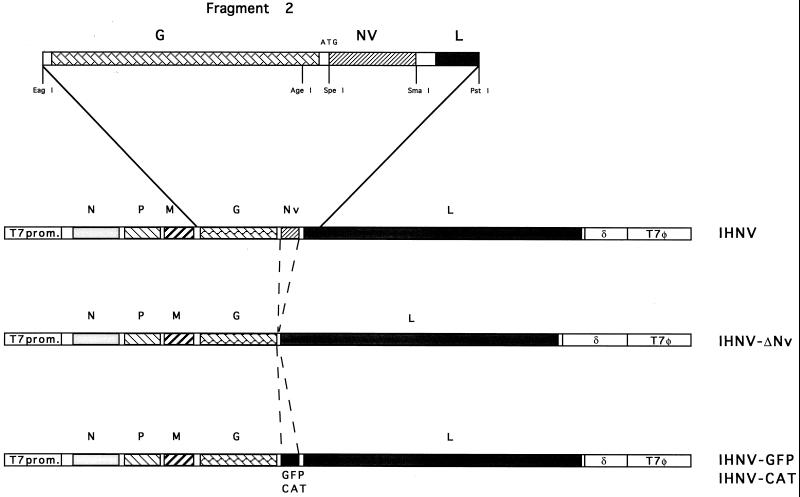

FIG. 3.

Construction of the pIHNV-ΔNV, pIHNV-CAT, and pIHNV-GFP plasmids. Fragment 2 (EagI-PstI) was engineered by site-directed mutagenesis to introduce SpeI and SmaI restriction enzyme sites and inserted in the pIHNV. The NV ORF was either deleted (pIHNV-ΔNV) or replaced by the CAT ORF (pIHNV-CAT) or the GFP ORF (pIHNV-GFP). T7 prom., T7 RNA polymerase transcription promoter; T7φ, T7 RNA polymerase transcription terminator.

Experimental fish infection.

Ten 3-month-old rainbow trout (Oncorhynccus mykiss) were injected intraperitoneally with 0.1 ml of rIHNV suspension per fish (approximately 106 PFU). The spleens and the kidneys of dead fish were homogenized in a mortar with a pestle and sea sand in 9 volumes of Eagle's solution containing penicillin (200 IU/ml), streptomycin (0.2 mg/ml), and kanamycin (0.2 mg/ml). After centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, the supernatant was passed through a membrane filter (0.45-μm pore diameter) and was used to inoculate EPC cells.

CAT assays.

A 100-μl lysate was prepared from cells (in 24-well plates) infected with IHNV-CAT after one and two passages of the viral supernatant, and 80 μl of each sample, adjusted to contain equal amounts of proteins, was assayed for CAT activity with [14C]chloramphenicol as the substrate (9). The reaction mixtures were incubated for 90 min, and products were analyzed by ascending thin-layer chromatography.

Immunostaining.

rIHNV- or IHNV-GFP-infected cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at 4°C and permeabilized for 30 min at room temperature in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. Intracellular eGFP was then immunodetected by incubation with a rabbit GFP-specific antiserum diluted in PBS for 30 min, washed, and incubated with a fluorescein-conjugated antirabbit immunoglobulin (Biosys, Compiègne, France). After washing, the cells were examined for staining with a UV-light microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, N.Y.).

Nucleotide sequencing.

All sequences of the plasmid constructs used in this study were checked by nucleotide sequencing reactions carried out on an ABI 373A DNA automatic sequencer by using a DyeDeoxy Terminator Prism kit (Applied Biosystems, Perkin-Elmer) and specific primers.

RESULTS

Construction of a plasmid encoding the full-length antigenomic IHNV RNA.

A cDNA pIHNV-Pst clone encoding the complete antigenome of IHNV was constructed as described in Materials and Methods. In the final construct, the T7 promoter was placed adjacent to the 3′ leader of the IHNV genome, and the hepatitis delta ribozyme (18) was fused to the 5′ trailer so that cleavage of the ribozyme would generate the precise IHNV antigenomic end. The nucleotide sequencing of the entire pIHNV-Pst construct confirmed the presence of the targeted mutation in position 5109 (C to G), creating a new unique PstI restriction site used for the construct, and an amino acid change (Q to E) in the L protein in position 32. A plasmid, pIHNV, in which the PstI site had been removed and replaced with the original sequence, was also engineered (see below). Several other incidental mutations, generated during the RT-PCRs, were identified, and some of them were either corrected by replacing the regions containing mutations by those derived from another full-length IHNV cDNA clone generated through a long RT-PCR (3) or corrected through site-directed mutagenesis. Thus, the pIHNV-Pst nucleotide sequences differed from the published sequence (20) at a total of 6 nt positions and were left unchanged to serve as additional markers for viruses recovered from cDNA.

Recovery of infectious rIHNV.

Transfection experiments were carried out on EPC cell monolayers in 6- or 12-well plates at 37°C following vTF7-3 infection, under the experimental conditions established previously for the rescue of IHNV-derived synthetic minigenomes (3). Cells were transfected with a mixture of pIHNV-Pst (0.5 μg), pT7-N (0.5 μg), pT7-P (0.2 μg), pT7-L (0.2 μg), and pT7-NV (0.125 μg) and then shifted to 14°C, the usual temperature for IHNV growth. At that temperature, we observed that recombinant vaccinia virus does not replicate, and the cytopathic effect induced by vTF7-3 was restricted to the appearance of some rounded cells (data not shown). The lack of vTF7-3 replication at 14°C allowed us to keep the infected and transfected EPC cells for 1 week posttransfection before passing the cell supernatant, thus potentially optimizing the recovery of rIHNV. As early as the first passage of the supernatant, typical IHNV-infected cell foci were visible, but the titer was very low (Table 2), and several additional passages on fresh cells were needed to amplify the recovered rIHNV.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of the efficiencies of recovery of recombinant virus from cDNAs

| Plasmid transfected

|

Virus titer (PFU/ml)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pIHNV-Pst | pIHNV | pT7-N | pT7-P | pT7-NV | pT7-L | |

| + | − | + | + | + | − | 0 |

| + | − | + | + | + | + | <103 |

| − | + | + | + | + | − | 0 |

| − | + | − | + | + | + | 8.7 × 103 |

| − | + | − | + | − | + | 8 × 103 |

| − | + | + | + | − | + | 1.4 × 104 |

| − | + | + | + | + | + | 2.2 × 104 |

Virus titer is the mean of six experiments.

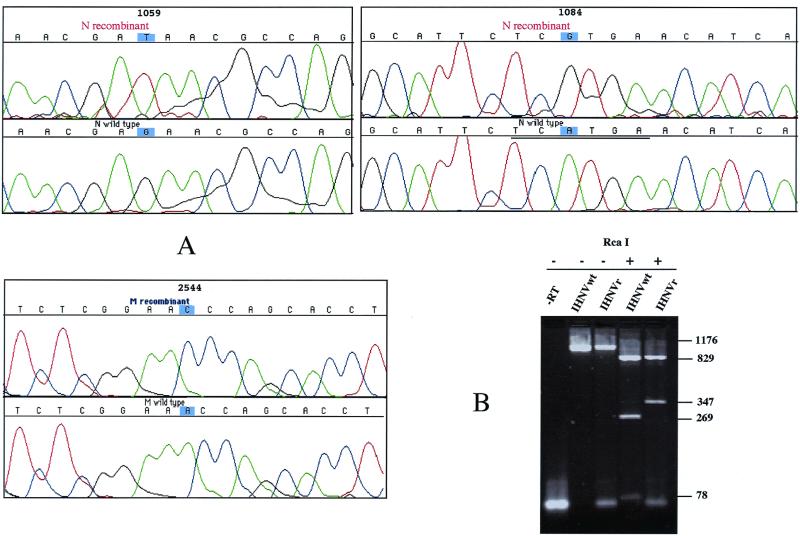

From the viral supernatant (passage P2), viral genomic RNA was extracted and used as a template for an RT-PCR using primers surrounding the PstI restriction enzyme site. The expected 800-nt PCR product was observed in the rIHNV and the wild-type IHNV (wtIHNV) as well and not when RT was omitted. However, through PstI restriction enzyme digestion, none of the products were cut (data not shown). The nucleotide sequencing of the 800-nt RT-PCR products generated from the rIHNV and wtIHNV RNA genomes gave similar sequences and confirmed the absence of a PstI restriction enzyme site. This unexpected result encouraged us to find another way to confirm that rIHNV was indeed recovered through cDNA transfection. Among the incidental mutations detected through the nucleotide sequencing of the pIHNV-Pst construct, two mutations were detected in the gene encoding the nucleoprotein N: the conversions of the nucleotides G to T (position 1059 from the genome numbering) and A to G (position 1084) leading to amino acid residue changes E to D and M to V, respectively. The latter change also destroyed an RcaI (TCATGA) restriction site. Another mutation was located in the gene encoding the M protein, a conversion of A to C (position 2544) inducing the change of the K residue to an N residue. Thus, the entire N and M coding regions were amplified through RT-PCR as described above, and DNA products were sequenced and also subjected to RcaI digestion (for the N PCR product). As shown in Fig. 2, the expected mutations are present, confirming the successful recovery of authentic rIHNV.

FIG. 2.

Genetic tags in rIHNV. (A) Electropherograms showing nucleotide sequence of part of the N and M PCR products. RT-PCR products generated from the wtIHNV and rIHNV genomes were sequenced across each of the three selected tags (blue boxes). The RcaI restriction enzyme site in the wild-type sequence is underlined. (B) Gel analysis of the RT-PCR product used to identify rIHNV. Total RNA extracted from cells infected with wtIHNV or rIHNV was amplified by RT-PCR with specific N-derived primers. PCR products were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel with (+) or without (−) restriction enzyme digestion. A control without reverse transcriptase (−RT) was added to ensure that no contaminating plasmids were present in rIHNV-infected cell supernatants. The sizes of the fragments in nucleotides are indicated on the right.

In another series of experiments, a full-length IHNV cDNA clone (pIHNV), in which the PstI site has been replaced by the original IHNV sequence, was used to recover rIHNV. As shown in Table 2, the titer of rIHNV at passage P1 was much higher than when the pIHNV-Pst construct was used. Interestingly, when pT7-N and/or pT7-NV was omitted in the transfection mix, rIHNV was also produced, although less efficiently and only when the amount of pIHNV was increased to 1 μg (when pT7-N is omitted [Table 2]). A similar observation had been made previously for the recovery of human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV-3), for which the plasmid encoding the nucleoprotein NP could be omitted (10). As for HPIV-3, the IHNV nucleoprotein was directly expressed from the pIHNV construct, since the pIHNV antigenomic transcript contains no AUG codons before the N initiating codon.

To ascertain that rIHNV was still pathogenic for fish, juvenile rainbow trout were intraperitoneally injected with rIHNV inoculum as described in Materials and Methods. Two weeks later, rIHNV was recovered from the organs of dead fish, and the titer of the virus was roughly 108 PFU/ml, demonstrating that rIHNV was as virulent as the wtIHNV. RT-PCR experiments with the virus recovered from fish revealed the presence, as described above, of the selected mutations (data not shown).

Recovery of rIHNV lacking the NV gene.

The full-length IHNV cDNA antigenome (pIHNV-Pst) was engineered so that the entire NV coding region was deleted and either self-ligated or replaced with reporter genes encoding GFP or CAT as depicted in Fig. 3. Fragment 2 (EagI-PstI), covering the G and NV genes and the beginning of the L gene was first modified to introduce, by site-directed mutagenesis, two unique SpeI and SmaI restriction enzyme sites bordering the NV ORF. Then fragment 2 was modified by removing the NV gene and inserting the reporter genes, before exchange with the counterpart fragment 2 in the pIHNV-Pst construct, leading to pIHNV-GFP and pIHNV-CAT. Following transfection, as described above, of each construct altogether with pT7-N, pT7-P, and pT7-L, expression of the reporter genes was monitored after one and two passages of the viral supernatant.

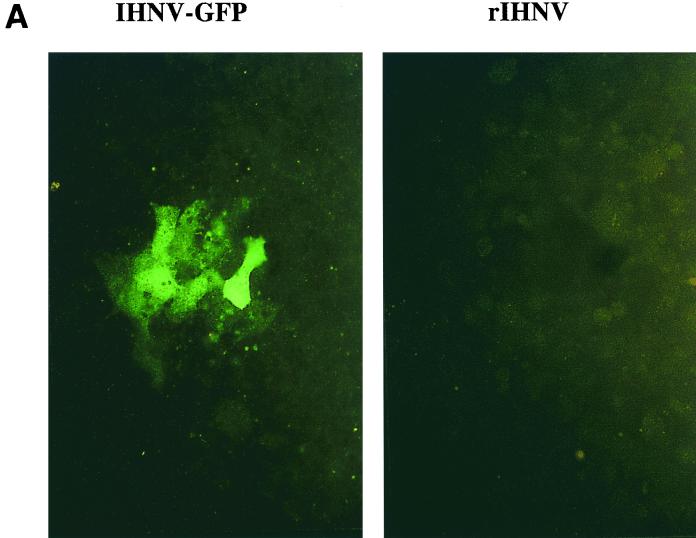

Direct UV-light microscope observations of cells infected with IHNV-GFP allowed the detection of only very weak GFP expression in IHNV-infected cell foci. Thus, the GFP expression in IHNV-GFP-infected cells was confirmed by an indirect immunofluorescence assay using a rabbit anti-GFP polyclonal antibody (Fig. 4A).

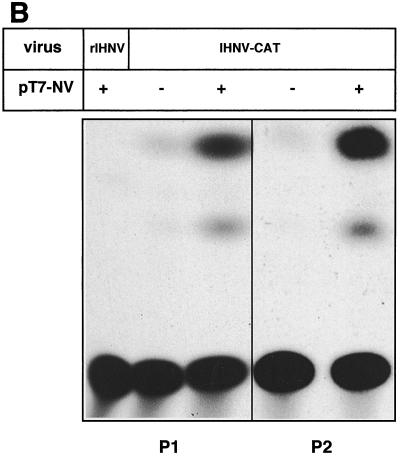

FIG. 4.

Expression of the reporter genes in cells infected with IHNV-GFP and IHNV-CAT. (A) EPC cells infected with rIHNV (right) or IHNV-GFP (left) were stained with an anti-GFP antibody and examined with a UV-light microscope. Infected cells expressing GFP appear in green. (B) Expression of the CAT gene was analyzed in lysates of cells infected with rIHNV (negative control) or IHNV-CAT after one (P1) or two (P2) passages of the viral inoculum P0. Inoculum P0 was obtained through transfection of vTF7-3-infected EPC cells with pIHNV-Pst or pIHNV-CAT, together with pT7-N, pT7-P, and pT7-L with (+) or without (−) pT7-NV.

A more sensitive assay, based on CAT activity detection, was developed with cells infected with the IHNV-CAT virus. Lysates of cells infected with IHNV-CAT after one or two passages of the viral supernatant PO were prepared 5 days postinfection. As shown in Fig. 4B, CAT activity was detected in lysates of infected cells after one passage of the viral supernatant and was increased after two passages. The addition of the pT7-NV plasmid in the transfection mix greatly increased the recovery of the IHNV-CAT at P0, since when it is omitted, only a very low level of CAT activity was detected at P1. Similar observations had been made previously with an IHNV-derived minigenome system (3).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have shown that infectious IHNV was successfully recovered from fish cells following infection with the vTF7-3 recombinant vaccinia virus and cotransfection with T7-driven expression plasmids containing a positive-sense copy of the IHNV genome and the three genes encoding the nucleocapsid proteins N, P, and L, following a strategy first developed for mammalian rhabdoviruses, like the rabies virus and VSV (13, 19, 21). The main obstacle to elaborating a reverse genetic system for IHNV, based on the use of vTF7-3, was to find temperature conditions compatible with vTF7-3 replication (>30°C) and IHNV growth (14°C). This problem was overcome when fish cells were infected with vTF7-3 and transfected with the expression plasmids at 37°C for 7 h before shifting the temperature to 14°C. Under these conditions, we observed that during the few hours at 37°C, the vTF7-3-infected cells expressed the majority of T7 RNA polymerase, allowing the transcription of the transfected expression plasmids. Moreover, since vTF7-3 does not replicate in fish cells at 14°C (3, 11), the cells could be kept for at least 1 week postinfection and posttransfection before passage of the viral supernatant, to optimize the recovery of rIHNV.

The targeted mutation introduced in the L gene to create a PstI restriction enzyme site and changing a Q to a E amino acid residue was shown to be deleterious for viral replication, since (i) it was eliminated from the recovered viruses in all of the experiments and (ii) the efficiency of the rIHNV recovery was drastically increased when a pIHNV construct was transfected instead of the pIHNV-Pst construct bearing the PstI site (Table 2). This phenomenon was previously observed and described in detail for the recovery of the Sendai virus (8), for which it has been shown that deleterious mutations are removed following vaccinia virus infection by homologous recombination between the T7-promoted plasmids. Thus the Q amino acid residue (position 32) in the L protein seems to be crucial for the transcriptase or replicase activities.

The rIHNV was not surprisingly morphologically indistinguishable from the wild-type virus by electron microscopy observations (data not shown) and rIHNV replicates in cell culture and was pathogenic in juvenile rainbow trout like the wtIHNV was. The addition of a plasmid encoding the nonstructural NV protein to the transfection mix slightly increased the efficiency of IHNV recovery in terms of the number of infected-cell foci after one passage of the viral supernatant (Table 2). However, the role of the NV protein in IHNV replication in cell culture is not yet clear, since rIHNV lacking that gene was also recovered, although the growth was much slower than for rIHNV or wtIHNV (not shown). Recently, another Novirhabdovirus which replicates at an elevated temperature of 31°C, the snakehead rhabdovirus (SHRV), was recovered from cDNA (11). Contrasting with our observations, in the SHRV model, when the NV gene was mutated to introduce a premature stop codon in the coding region, no differences in the viral titer were observed compared to the wild-type SHRV. The observation that the NV protein is not absolutely required for the replication of IHNV in cell culture allowed us to use the NV gene as a cassette for the insertion of reporter genes. Due to the location of the reporter genes in the recombinant viral genomes, we anticipated that their expression in the infected cells should be low, according to the transcription gradient observed during the replication of the viruses belonging to Mononegavirales. That was confirmed by the very low level of GFP expression detected in IHNV-GFP-infected cells, through direct UV-light microscope observations, and really accurately detectable through indirect immunofluorescence assays or CAT assays when IHNV-CAT was used to infect cells.

The recovery of NV knockout IHNV and the expression of reporter genes, instead of NV, in infected cells seem to indicate that NV is a dispensable protein in cell culture. However, it must be pointed out that the viruses lacking the NV gene grow much slower than the other rIHNVs studied and that, in some cases, the virus-induced cytopathic effect on the infected-cell monolayers appeared to decrease over the time, and even the cell monolayers seemed to heal. We do not yet know whether that observation reflects a biological role for NV. Since experimental disease and infections in fish are well established with IHNV, the potential role of NV in the virulence and/or the tissue tropism in fish infected with NV knockout IHNV is now under investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work has been carried out with financial support from the Commission of the European Communities, Agriculture and Fisheries (FAIR) specific RDT program (CT98-4398).

We thank Michel Dorson (INRA) for access to the fish facilities, Cynthia Jaeger (INRA) for the sequencing reactions, Mohamed Nedjmidine (INRA) for the gift of the rabbit anti-GFP antisera, and Wendy Brand-Williams (INRA) for carefully reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basurco B, Benmansour A. Distant strains of the fish rhabdovirus VHSV maintain a sixth functional cistron which codes for a nonstructural protein of unknown function. Virology. 1995;212:741–745. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benmansour A, de Kinkelin P. Live fish vaccines: history and perspectives. Dev Biol Stand. 1997;90:279–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biacchesi S, Yu Y X, Béarzotti M, Tafalla C, Fernandez-Alonso M, Brémont M. Rescue of synthetic salmonid rhabdovirus minigenomes. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:1941–1945. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-8-1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boudinot P, Blanco M, de Kinkelin P, Benmansour A. Combined DNA immunization with the glycoprotein gene of viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus and infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus induces double-specific protective immunity and nonspecific response in rainbow trout. Virology. 1998;249:297–306. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conzelmann K K. Nonsegmented negative-strand RNA viruses: genetics and manipulation of viral genomes. Annu Rev Genet. 1998;132:123–162. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fijan N, Sulimanovic M, Béarzotti M, Muzinic D, Zwillenberg L O, Chilmonczyk S, Vautherot J F, de Kinkelin P. Some properties of the Epithelioma papulosum cyprini EPC cell line from carp Cyprinus carpio. Ann Inst Pasteur Virol. 1983;134E:207–220. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuerst T R, Niles E G, Studier F W, Moss B. Eucaryotic transient expression system based on recombinant vaccinia virus that synthesizes bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8122–8126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcin D, Pelet T, Calain P, Roux L, Curran J, Kolakofsky D. A highly recombinogenic system for the recovery of infectious Sendai paramyxovirus from cDNA: generation of a novel copy-back nondefective interfering virus. EMBO J. 1995;14:6087–6094. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorman C M, Moffat L F, Howard B H. Recombinant genomes which express chloramphenicol acetyltransferase in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:1044–1051. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.9.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffman M A, Banerjee A K. An infectious clone of human parainfluenza virus type 3. J Virol. 1997;71:4272–4277. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4272-4277.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson M C, Simon B E, Kim C H, Leong J C. Production of recombinant snakehead rhabdovirus: the NV protein is not required for viral replication. J Virol. 2000;74:2343–2350. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2343-2350.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurath G, Leong J C. Characterization of infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus mRNA species reveals a nonvirion rhabdovirus protein. J Virol. 1985;53:462–468. doi: 10.1128/jvi.53.2.462-468.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawson N D, Stillman E A, Whitt M A, Rose J K. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis viruses from DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4477–4481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorenzen N, Olesen N J, Jorgensen P E. Neutralization of Egtved virus pathogenicity to cell cultures and fish by monoclonal antibodies to the viral G protein. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:561–567. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-3-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lorenzen N, Olesen N J. Immunization with viral antigens: viral haemorrhagic septicaemia. Dev Biol Stand. 1997;90:201–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morzunov S P, Winton J R, Nichol S T. The complete genome structure and phylogenetic relationship of infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus. Virus Res. 1995;38:175–192. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00056-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pekosz A, He B, Lamb R A. Reverse genetics of negative-strand RNA viruses: closing the circle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8804–8806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perrota A T, Been M D. A pseudoknot-like structure required for efficient self-cleavage of hepatitis delta virus RNA. Nature. 1991;350:434–436. doi: 10.1038/350434a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnell M J, Mebastsion T, Conzelmann K K. Infectious rabies viruses from cloned cDNA. EMBO J. 1994;13:4195–4203. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06739.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schutze H, Enzmann P J, Kuchling R, Mundt E, Niemann H, Mettenleiter T C. Complete genomic sequence of the fish rhabdovirus infectious haematopoietic necrosis virus. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2519–2527. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-10-2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whelan S P J, Ball L A, Barr J N, Wertz G T W. Efficient recovery of infectious vesicular stomatitis virus entirely from cDNA clones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8388–8392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winton J R. Immunization with viral antigens: haematopoietic necrosis. Dev Biol Stand. 1997;90:211–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]