Abstract

Background

Weight gain is common for people with schizophrenia and this has serious implications for a patient's health and well being. Switching strategies have been recommended as a management option.

Objectives

To determine the effects of antipsychotic medication switching as a strategy for reducing or preventing weight gain and metabolic problems in people with schizophrenia.

Search methods

We searched key databases and the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's trials register (January 2005 and June 2007), reference sections within relevant papers and contacted the first author of each relevant study and other experts to collect further information.

We updated this search November 2012 and added 167 new trials to the awaiting classification section.

Selection criteria

All clinical randomised controlled trials comparing switching of antipsychotic medication as an intervention for antipsychotic induced weight gain and metabolic problems with continuation of medication and/or other weight loss treatments (pharmacological and non pharmacological) in people with schizophrenia or schizophrenia‐like illnesses.

Data collection and analysis

Studies were reliably selected, quality assessed and data extracted. For dichotomous data we calculated risk ratio (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) on an intention‐to‐treat basis, based on a fixed‐effect model. The primary outcome measures were weight loss, metabolic syndrome, relapse and general mental state.

Main results

We included four studies for the review with a total of 636 participants. All except one study had a duration of 26 weeks or less. There was a mean weight loss of 1.94 kg (2 RCT, n = 287, CI ‐3.9 to 0.08) when switched to aripiprazole or quetiapine from olanzapine. BMI also decreased when switched to quetiapine (1 RCT, n = 129, MD ‐0.52 CI ‐1.26 to 0.22) and aripiprazole (1 RCT, n = 173, RR 0.28 CI 0.13 to 0.57) from olanzapine.

Fasting blood glucose showed a significant decrease when switched to aripiprazole or quetiapine from olanzapine. (2 RCT, MD ‐2.53 n = 280 CI ‐2.94 to ‐2.11). One RCT also showed a favourable lipid profile when switched to aripiprazole but these measures were reported as percentage changes, rather than means with standard deviation.

People are less likely to leave the study early if they remain on olanzapine compared to switching to quetiapine or aripiprazole.

There was no significant difference in outcomes of mental state, global state, and adverse events between groups which switched medications and those that remained on previous medication. Three different switching strategies were compared and no strategy was found to be superior to the others for outcomes of weight gain, mental state and global state.

Authors' conclusions

Evidence from this review suggests that switching antipsychotic medication to one with lesser potential for causing weight gain or metabolic problems could be an effective way to manage these side effects, but the data were weak due to the limited number of trials in this area and small sample sizes. Poor reporting of data also hindered using some trials and outcomes. There was no difference in mental state, global state and other treatment related adverse events between switching to another medication and continuing on the previous one. When the three switching strategies were compared none of them had an advantage over the others in their effects on the primary outcomes considered in this review. Better designed trials with adequate power would provide more convincing evidence for using medication switching as an intervention strategy.

Note: the 167 citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.

Keywords: Humans, Drug Substitution, Antipsychotic Agents, Antipsychotic Agents/adverse effects, Antipsychotic Agents/therapeutic use, Aripiprazole, Benzodiazepines, Benzodiazepines/adverse effects, Benzodiazepines/therapeutic use, Blood Glucose, Blood Glucose/metabolism, Body Mass Index, Body Weight, Body Weight/drug effects, Dibenzothiazepines, Dibenzothiazepines/therapeutic use, Fasting, Fasting/blood, Olanzapine, Piperazines, Piperazines/therapeutic use, Quetiapine Fumarate, Quinolones, Quinolones/therapeutic use, Schizophrenia, Schizophrenia/blood, Schizophrenia/drug therapy, Weight Gain, Weight Gain/drug effects

Plain language summary

Can changing antipsychotic medication improve side effects like increases in weight, blood sugar and cholesterol?

Weight gain is common among people with schizophrenia. The medication commonly used to treat schizophrenia may cause substantial weight gain. This weight gain could be treated through lifestyle interventions that increase physical activity or change diet; or through using other forms of medication that might help with weight loss. However, an easier alternative might be changing the antipsychotic medication to one that causes less weight gain. This review examines evidence for this possibility. Switching antipsychotic medication did show some reduction in weight and also contributed broader health benefits such as reducing fasting blood glucose. Notably, there were no significant difference in outcomes of mental state, global state and adverse events between groups which switched medications and those that remained on previous medication.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. SWITCHING ‐ NEW ANTIPSYCHOTIC REGIMEN compared to CONTINUATION ON PREVIOUS REGIMEN: 1a. DIFFERENT DEPOT from DEPOT‐medium term (3‐12 months) for people with schizophrenia who have neuroleptic‐induced weight or metabolic problems.

| SWITCHING ‐ NEW ANTIPSYCHOTIC REGIMEN compared to CONTINUATION ON PREVIOUS REGIMEN: 1a. DIFFERENT DEPOT from DEPOT‐medium term (3‐12 months) for people with schizophrenia who have neuroleptic‐induced weight or metabolic problems | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with people with schizophrenia who have neuroleptic‐induced weight or metabolic problems Settings: in community Intervention: SWITCHING ‐ NEW ANTIPSYCHOTIC REGIMEN Comparison: CONTINUATION ON PREVIOUS REGIMEN: 1a. DIFFERENT DEPOT from DEPOT‐medium term (3‐12 months) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| CONTINUATION ON PREVIOUS REGIMEN: 1a. DIFFERENT DEPOT from DEPOT‐medium term (3‐12 months) | SWITCHING ‐ NEW ANTIPSYCHOTIC REGIMEN | |||||

| Weight: Body weight (kg) ‐ switching to haloperidol decanoate from fluphenazine decanoate Follow‐up: 12 months | The mean Weight: Body weight (kg) ‐ switching to haloperidol decanoate from fluphenazine decanoate in the intervention groups was 2.8 lower (7.04 lower to 1.44 higher) | 19 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Relevant trial but small study. SD estimated rather than reported directly. | ||

| Weight: BMI not improved | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (03) | See comment | Outcome of interest ‐ but no study reported this outcome. |

| Physiological measure: Metabolic syndrome | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (03) | See comment | Outcome of interest ‐ but no study reported this outcome. |

| Global state: Changing dose because of deterioration ‐ switching to haloperidol decanoate from fluphenazine decanoate Follow‐up: 12 months | 222 per 1000 | 40 per 1000 (2 to 744) | RR 0.18 (0.01 to 3.35) | 19 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Stated specific scales were to be used ‐ but no direct data reported form these measures. Criteria for 'deterioration' not explicit |

| Mental state: Deteriorated ‐ switching to haloperidol decanoate from fluphenazine decanoate Follow‐up: 12 months | 222 per 1000 | 40 per 1000 (2 to 744) | RR 0.18 (0.01 to 3.35) | 19 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Stated specific scales were to be used ‐ but no direct data reported form these measures. Criteria for 'deterioration' not explicit |

| Adverse effects: serious | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (03) | See comment | Outcome of interest ‐ but no study reported this outcome. |

| Satisfaction with care: Loss to follow up ‐ switching to haloperidol decanoate from fluphenazine decanoate Follow‐up: 12 months | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | RR 4.55 (0.25 to 83.7) | 19 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,4,5 | Small trial. Unclear if loss to follow up really reflects 'satisfaction'. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Randomisation not well described 2 Small study, likely that others are not identified 3 No study reported this finding 4 Loss to follow up not simply measure of satisfaction 5 Wide confidence intervals

Summary of findings 2. SWITCHING ‐ NEW ANTIPSYCHOTIC REGIMEN compared to CONTINUATION ON PREVIOUS REGIMEN: 1b. NEW ATYPICAL from OLANZAPINE ‐ medium term (3‐12 months) for people with schizophrenia who have neuroleptic‐induced weight or metabolic problems.

| SWITCHING ‐ NEW ANTIPSYCHOTIC REGIMEN compared to CONTINUATION ON PREVIOUS REGIMEN: 1b. NEW ATYPICAL from OLANZAPINE ‐ medium term (3‐12 months) for people with schizophrenia who have neuroleptic‐induced weight or metabolic problems | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with people with schizophrenia who have neuroleptic‐induced weight or metabolic problems Settings: community Intervention: SWITCHING ‐ NEW ANTIPSYCHOTIC REGIMEN Comparison: CONTINUATION ON PREVIOUS REGIMEN: 1b. NEW ATYPICAL from OLANZAPINE ‐ medium term (3‐12 months) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| CONTINUATION ON PREVIOUS REGIMEN: 1b. NEW ATYPICAL from OLANZAPINE ‐ medium term (3‐12 months) | SWITCHING ‐ NEW ANTIPSYCHOTIC REGIMEN | |||||

| Weight: 1. Body weight (kg) | The mean Weight: 1. Body weight (kg) in the intervention groups was 1.94 lower (3.97 lower to 0.08 higher) | 287 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3 | |||

| Weight: 1. Body weight (kg) ‐ switching to aripiprazole | The mean Weight: 1. Body weight (kg) ‐ switching to aripiprazole in the intervention groups was 3.21 lower (9.03 lower to 2.61 higher) | 158 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | |||

| Weight: 2a. BMI ‐ Increase | Study population | RR 0.28 (0.13 to 0.57) | 173 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,4 | ||

| 329 per 1000 | 92 per 1000 (43 to 188) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 329 per 1000 | 92 per 1000 (43 to 188) | |||||

| Physiological measures: 1c. Average fasting glucose change ‐ switching to aripiprazole and quetiapine | The mean Physiological measures: 1c. Average fasting glucose change ‐ switching to aripiprazole and quetiapine in the intervention groups was 2.53 lower (2.94 to 2.11 lower) | 280 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | |||

| Global state: Relapse | Study population | RR 1.31 (0.55 to 3.11) | 133 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | ||

| 118 per 1000 | 155 per 1000 (65 to 367) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 118 per 1000 | 155 per 1000 (65 to 367) | |||||

| Adverse events: 1a. Serious adverse event ‐ switching to aripiprazole | Study population | RR 0.64 (0.24 to 1.71) | 172 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | ||

| 107 per 1000 | 68 per 1000 (26 to 183) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 107 per 1000 | 68 per 1000 (26 to 183) | |||||

| Satisfaction with care: Loss to follow up ‐ switching to aripiprazole | Study population | RR 1.4 (0.89 to 2.21) | 173 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3,5 | ||

| 259 per 1000 | 363 per 1000 (231 to 572) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 259 per 1000 | 363 per 1000 (231 to 572) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Randomisation process not described. 2 In one study there were no results from the various scales mentioned in the methods section . This study was terminated early as only 33% of the enrolment target was achieved. 3 Sponsored by interested industry. 4 The study was not published but found in the drug industry's trial register so likely that there are other similar trials which may have been missed. 5 Satisfaction with care alone may not account for all loss to follow up.

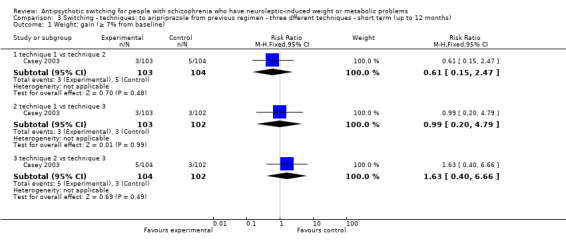

Summary of findings 3. SWITCHING ‐ TECHNIQUES: TO ARIPIPRAZOLE from PREVIOUS REGIMEN ‐ THREE DIFFERENT TECHNIQUES ‐short term (up to 12 months) for people with schizophrenia who have neuroleptic‐induced weight or metabolic problems.

| SWITCHING ‐ TECHNIQUES: TO ARIPIPRAZOLE from PREVIOUS REGIMEN ‐ THREE DIFFERENT TECHNIQUES ‐short term (up to 12 months) for people with schizophrenia who have neuroleptic‐induced weight or metabolic problems | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with people with schizophrenia who have neuroleptic‐induced weight or metabolic problems Settings: Intervention: SWITCHING ‐ TECHNIQUES: TO ARIPIPRAZOLE from PREVIOUS REGIMEN ‐ THREE DIFFERENT TECHNIQUES ‐short term (up to 12 months) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | SWITCHING ‐ TECHNIQUES: TO ARIPIPRAZOLE from PREVIOUS REGIMEN ‐ THREE DIFFERENT TECHNIQUES ‐short term (up to 12 months) | |||||

| Weight: Gain‐more than or equal to 7% from baseline | Study population | RR 0.61 (0.15 to 2.47) | 207 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | Switching of treatment in this study may not have been for weight control therefore this client group may differ from those in the other trials in this review | |

| 48 per 1000 | 29 per 1000 (7 to 119) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 48 per 1000 | 29 per 1000 (7 to 119) | |||||

| Weight: BMI not improved | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | Outcome of interest‐but the study did not report this outcome |

| Physiological measure: Metabolic syndrome | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | Outcome of interest‐but the study did not report this outcome |

| Global state: Average change (CGI‐I, high=good) | The mean Global state: Average change (CGI‐I, high=good) in the intervention groups was 0.14 lower (0.49 lower to 0.21 higher) | 203 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |||

| Mental state: Average change (PANSS, high decline=good) | The mean Mental state: Average change (PANSS, high decline=good) in the intervention groups was 2.52 higher (2.39 lower to 7.43 higher) | 198 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |||

| Adverse events: Any event | Study population | RR 1 (0.91 to 1.1) | 207 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 894 per 1000 | 894 per 1000 (814 to 983) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 894 per 1000 | 894 per 1000 (814 to 983) | |||||

| Satisfaction with care: Loss to follow up ‐ non‐compliance | Study population | RR 4 (0.45 to 35.19) | 208 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 40 per 1000 (4 to 352) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 10 per 1000 | 40 per 1000 (4 to 352) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Sponsored by interested industry. 2 Wide confidence intervals. 3 Satisfaction with care alone may not account for all loss to follow ups.

Background

Description of the condition

Obesity is a common problem in people with schizophrenia. Weight gain and metabolic disturbance are recognised side effects of many second‐generation antipsychotic drugs, which is the mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia (Allison 1999; Casey 2004; Homel 2002). The prevalence of obesity in people with schizophrenia has been reported to be 1.5 to 4 times higher than the general population (ADA/APA 2004; Coodin 2001; Silverstone 1988). People with schizophrenia have a marked increase in standardised mortality ratio for both natural and unnatural causes of death .The rise in mortality may be attributed to the increased risk of coronary heart disease (Cohn 2004; Goff 2005; Henderson 2005; Mackin 2005; Saari 2005), and increased prevalence of obesity in this population (Coodin 2001; Daumit 2003; Susce 2005). Obesity doubles the risk of all‐cause mortality, coronary heart disease, stroke and Type II diabetes. It also increases the risk of some cancers, musculoskeletal problems and loss of function, and carries negative psychological consequences (DoH 2004).

Many factors such as genetics, adverse effects of medications, poor diet and inactive lifestyle may contribute to the prevalence of obesity in schizophrenia. In a meta‐analysis, every antipsychotic medication except ziprasidone and molindone was found to be associated with some degree of weight gain after just 10 weeks of treatment (Allison 1999). The effects were greatest with olanzapine and clozapine, which swiftly increased body weight by 4‐4.5 kilograms. There is no consensus on exactly how the newer antipsychotic drugs cause weight gain.

Quality of life is further reduced for people with schizophrenia with high body mass index (Kurzthaler 2001; Strassnig 2003) and those gaining weight (Allison 2003). Furthermore, Weiden 2004 reported a significant positive association between obesity, subjective distress from weight gain and medication non‐compliance in a sample of people with schizophrenia. People suffering from schizophrenia also face the combined challenges of living with schizophrenia, and for many, obesity and related illnesses. This combination is a major public health problem (Wirshing 2004) and carries considerable human cost.

Second‐generation antipsychotic drugs, in spite of their benefits, have been associated with the so‐called metabolic syndrome, the triad of weight gain, diabetes and dyslipidaemia. The International Diabetes Federation published a consensus statement on the definition of metabolic syndrome in 2006 (IDF). The criteria for the syndrome includes central obesity (defined as waist circumference of more than 94cm for Europoid* men and 80 cm for Europoid women with ethnic specific values for other groups), as well as any two from the following four factors: ‐ raised triglyceride levels or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality; ‐ reduced HDL cholesterol; ‐ raised blood pressure or treatment of previously diagnosed hypertension; ‐ raised plasma glucose or previously diagnosed Type II diabetes. (* Europoid: a technical term used to describe a physical type like one of the phenotypes, or genotypes types found today in Europe (Wikipedia 2007)).

Description of the intervention

Recognition of the metabolic syndromes in people who are on second‐generation antipsychotic medication and the resulting increase in morbidity and mortality has led to discussions on effective intervention strategies (Birt 2003; Catapana 2004; Green 2000; Le Fevre 2001; Osborn 2001) and consensus statements on its management (e.g., ADA/APA 2004; De Nayer 2005). Treatment of obesity in this population involves non‐pharmacological and pharmacological interventions. Existing evidence suggests that even effective treatments for adult obesity only produce modest weight loss (approximately 2 kg to 5 kg) compared to no treatment or usual care (Faulkner 2007). Switching to a drug with less potential for weight gain and metabolic problems can also lead to weight loss and metabolic improvement.

How the intervention might work

Studies have shown that when one atypical antipsychotic is switched to another, changes in weight occur. In Ried 2003, when people were switched from olanzapine to risperidone and risperidone to olanzapine, the group switched to olanzapine gained weight while those changed to risperidone lost. Hester 2005 found that for people who had gained weight on olanzapine, switching to another antipsychotic drug was an effective option to reduce weight in some patients. The consensus statement on the management of metabolic syndrome associated with atypical antipsychotic use also recommends that if a stable patient on a second‐generation antipsychotic gains 5% of his or her initial weight at any time during therapy, one should consider switching the medication (ADA/APA 2004).

Four different switch strategies can be used: ‐ the cross‐taper strategy (gradually titrating up the new medication while tapering off the older medication); ‐ starting new medication at the therapeutic dose while tapering off the older one; ‐ stopping older antipsychotic drugs abruptly while gradually increasing the new one; or ‐ starting the new drug at therapeutic dose and stopping the old one abruptly. The cross‐taper strategy is considered to be the safest approach.

A recent review looked at four randomised controlled trials on switching strategies and suggested that available evidence does not yet support the clinical superiority of switching antipsychotic drugs on various outcome measures, including weight gain (Remington 2005).

Why it is important to do this review

Anyone might have difficulties undergoing available pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions for weight gain due to lack of motivation or other lifestyle factors. For people with schizophrenia these problems may be particularly acute; hence switching to an antipsychotic medication which is less likely to cause weight gain seems to be a practical alternative. Using an antipsychotic which is less likely to cause weight gain initially may also be critical for preventing or reducing weight gain. A recent Cochrane review (Faulkner 2007) looked at pharmacological (anti‐obesity agents) and non‐pharmacological (diet/exercise) interventions for reducing or preventing weight gain in people with schizophrenia but specifically excluded medication switching as an intervention strategy. This sister review extends the investigation by focusing on randomised trials in which switching antipsychotic medication is used as an intervention for people with schizophrenia who have antipsychotic induced weight or metabolic problems.

Objectives

To determine the effects of antipsychotic medication switching as a strategy for reducing or preventing weight gain in people with schizophrenia who have neuroleptic induced weight or metabolic problems.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised controlled trials. Where a trial was described as 'double‐blind', but it was only implied that the study was randomised, we have included these trials in a sensitivity analysis. If there was no substantive difference within primary outcomes (see Types of outcome measures) when these 'implied randomisation' studies were added, then we included those in the final analysis. If there was a substantive difference, we used only clearly randomised trials and described the results of the sensitivity analysis in the text. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

People diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizophrenia‐like illnesses, using any criteria, with weight or metabolic problems. We included trials where it was implied that the majority (more than 50%) of participants had a severe mental illness likely to be schizophrenia.

For purposes of this review we use two definitions of weight or metabolic problems ‐ a grade 'A' definition and a less stringent grade 'B'. A ‐ Everyone starting had weight or metabolic problems as defined by the trialists and there was, at least, a suggestion that this problem had been caused by use of antipsychotic medication. B ‐ Everyone participating had measures relevant to weight or metabolic problems recorded, whether or not they fell into the category of obese or metabolic syndrome.

We did not exclude participants on the basis of age, nationality, sex or setting of treatment.

Types of interventions

A. COMPARISON 01: Absolute effect of switching. 1. Any antipsychotic medication switching; versus 2. continuation of medication as before.

B. COMPARISON 02: Comparative effect of switching versus other weight management techniques. 1. Any antipsychotic medication switching; versus 2. continuation of antipsychotic plus adjunctive pharmacological interventions (used for weight or metabolic benefit such as orlistat, nizatidine); or 3. continuation of antipsychotic plus non‐pharmacological interventions (e.g. diet, exercise, counselling); or 4. discontinuation of antipsychotic plus pharmacological interventions (used for weight or metabolic benefit such as orlistat, nizatidine); or 5. discontinuation of antipsychotic plus non‐pharmacological interventions (e.g. diet, exercise, counselling).

C. COMPARISON 03: Comparative effect of different techniques of switching. 1. Abrupt discontinuation + abrupt replacement; versus 2. abrupt discontinuation + gradual replacement; or 3. gradual discontinuation + abrupt replacement; or 4. gradual discontinuation + gradual replacement.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

1. Weight and physiological measures 1.1 No clinically important change in body weight (as defined by individual studies) 1.2 Presence of metabolic syndrome

2. Global state 2.1 Relapse

3. Mental state (with particular reference to the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia) 3.1 No clinically important change in general mental state

Secondary outcomes

1. Weight and physiological measures 1.1 Total body weight (lbs/kg) 1.2 Change in body weight 1.3 No clinically important change in body mass index (BMI) (as defined by individual studies) 1.4 Total BMI 1.5 Change in BMI 1.6 No clinically important change in waist circumference (as defined by individual studies) 1.7 Total waist circumference 1.8 Change in waist circumference 1.9 No clinically important change in waist‐to‐hip circumference ratio (as defined by individual studies) 1.10 Total waist‐to‐hip circumference ratio 1.11 Change in waist‐to‐hip circumference ratio 1.12 No clinically important change in total percent body fat (as defined by individual studies) 1.13 Total percent body fat 1.14 Change in percent body fat 1.15 Serum cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglyceride profile

2. Global state 2.1 No clinically important change in global state (as defined by individual studies) 2.2 Average endpoint global state score 2.3 Average change in global state scores

3. Mental state (with particular reference to the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia) 3.1 Average endpoint general mental state score 3.2 Average change in general mental state scores 3.3 No clinically important change in specific symptoms (positive symptoms of schizophrenia, negative symptoms of schizophrenia, depression, mania) 3.4 Average endpoint specific symptom score 3.5 Average change in specific symptom scores

4. Service outcomes 4.1 Hospitalisation 4.2 Time to hospitalisation

5. General functioning 5.1 No clinically important change in general functioning 5.2 Average endpoint general functioning score 5.3 Average change in general functioning scores 5.4 No clinically important change in specific aspects of functioning, such as social or life skills 5.5 Average endpoint specific aspects of functioning, such as social or life skills 5.6 Average change in specific aspects of functioning, such as social or life skills

6. Behaviour 6.1 No clinically important change in general behaviour 6.2 Average endpoint general behaviour score 6.3 Average change in general behaviour scores 6.4 No clinically important change in specific aspects of behaviour 6.5 Average endpoint specific aspects of behaviour 6.6 Average change in specific aspects of behaviour

7. Adverse effects ‐ general and specific 7.1 Clinically important general adverse effects 7.2 Average endpoint general adverse effect score 7.3 Average change in general adverse effect scores 7.4 Clinically important specific adverse effects 7.5 Average endpoint specific adverse effects 7.6 Average change in specific adverse effects 7.7 Death ‐ suicide and natural causes

8. Engagement with services

9. Satisfaction with treatment 9.1 Leaving the studies early 9.2 Recipient of care not satisfied with treatment 9.3 Recipient of care average satisfaction score 9.4 Recipient of care average change in satisfaction scores 9.5 Carer not satisfied with treatment 9.6 Carer average satisfaction score 9.7 Carer average change in satisfaction scores

10. Quality of life 10.1 No clinically important change in quality of life 10.2 Average endpoint quality of life score 10.3 Average change in quality of life scores 10.4 No clinically important change in specific aspects of quality of life 10.5 Average endpoint specific aspects of quality of life 10.6 Average change in specific aspects of quality of life

11. Economic outcomes 11.1 Direct costs 11.2 Indirect costs

We planned to divide outcome periods into short‐term (less than three months), medium‐term (3‐12 months) and long‐term follow‐up (longer than one year).

Search methods for identification of studies

We followed recommendations of the Schizophrenia Review Group search strategy and the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook in developing our search strategy (Higgins 2005).

Electronic searches

The studies included in this review are from three separate searches: (a) all the references that came up in the 2005 search for the review looking at the interventions other than switching antipsychotics for reducing or preventing weight gain (Faulkner 2007); (b) additional references that came up in the update search in 2007 and (c) other relevant articles identified by the authors as the review progressed through searching registers of ongoing clinical trials, inspecting reference list of all identified studies, including existing reviews for relevant citations and asking representatives from major pharmaceutical companies (Eli Lilly, Astra Zeneca, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb) if they have conducted or were currently undertaking any weight‐related interventions in relation to schizophrenia. This was done along with the update search.

1. Update search (2007)

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register was searched (June 2007) using the phrase:

[ (weight* or body mass* or bmi* or diet* or * eat* or waist* or obes* or * fat* or metaboli* in title, abstract, index terms of REFERENCE) or ( (switch* in intervention field) and (weight* or body mass* or diet* or eat* or waist* or obes* or metaboli* in outcome field) of study)].

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, hand searches and conference proceedings (see Group Module).

2. Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register register (November 2012)

The Trials Search Co‐ordinator, Samantha Roberts, searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register register (November 2012) using the phrase:

[ (weight* or body mass* or bmi* or diet* or * eat* or waist* or obes* or * fat* or metaboli* in title, abstract, index terms of REFERENCE) or ( (switch* in intervention field) and (weight* or body mass* or diet* or eat* or waist* or obes* or metaboli* in health care conditions field of study)].

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, handsearches of relevant journals and conference proceedings (see Group Module). Incoming trials are assigned to relevant existing or new review titles.

2. Previous search strategy (2005)

See Appendix 1

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected the reference lists of all identified studies, including existing reviews, for relevant citations.

2. Personal contact

We contacted the first author of each relevant study for information on unpublished trials. We also consulted experts in the area of schizophrenia and weight gain. We contacted authors and experts by email or post to establish missing details in the methods and results sections of the written reports and to determine their knowledge of or involvement in any current work in the area. We also asked contacts at major pharmaceutical companies if they have conducted or were currently undertaking any weight‐related interventions in relation to schizophrenia (including representatives from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer Inc, Eli Lilly and Company, Astra Zeneca, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Four review authors (AM, GF, TC, GR) independently assessed the abstracts of the studies returned by the searches for relevance. When the authors disagreed or the abstract was unclear, we obtained the full report, repeated the assessment process and reached a decision on inclusion by consensus.

Data extraction and management

AM independently extracted data from selected trials. When disputes arose we attempted to resolve these by discussion. When this was not possible and further information was necessary to resolve the dilemma, we did not enter data and added the trial to the list of those awaiting assessment.

1. Extraction

AM independently extracted data from included studies. Again, we discussed any disagreement, documented decisions and, if necessary, contacted authors of studies for clarification. When this was not possible and further information was necessary to resolve the dilemma, we did not enter data and added the trial to the list of those awaiting assessment.

2. Management

We extracted the data onto standard, simple forms. Where possible, we entered data into Review Manager (RevMan) (RevMan 2008) in such a way that the area to the left of the 'line of no effect' indicates a 'favourable' outcome for the experimental treatment. Where this was not possible (e.g. scales that calculate higher scores = improvement) we have labelled the graphs in RevMan analyses accordingly so that the direction of effects was clear.

3. Scale‐derived data

A wide range of instruments are available to measure outcomes in mental health studies. These instruments vary in quality and many are not validated, or are even ad hoc. It is accepted generally that measuring instruments should have the properties of reliability (the extent to which a test effectively measures anything at all) and validity (the extent to which a test measures that which it is supposed to measure). Unpublished scales are known to be subject to bias in trials of treatments for schizophrenia (Marshall 2000). Therefore we included continuous data from rating scales only if the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal. In addition, we set the following minimum standards for instruments: the instrument should either be (a) a self‐report or (b) completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist) and (c) the instrument should be a global assessment of an area of functioning. Whenever possible we took the opportunity to make direct comparisons between trials that used the same measurement instrument to quantify specific outcomes. Where continuous data were presented from different scales rating the same effect, we presented both sets of data and inspected the general direction of effect.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias using the tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2009). This tool encourages consideration of how the sequence was generated, how allocation was concealed, the integrity of blinding at outcome, the completeness of outcome data, selective reporting and other biases. We would not have included studies where sequence generation was at high risk of bias or where allocation was clearly not concealed. The categories are defined below. YES ‐ low risk of bias. NO ‐ high risk of bias. UNCLEAR ‐ uncertain risk of bias.

If disputes arose as to which category a trial has to be allocated, again, we resolved these by discussion, after working with a third reviewer.

In addition, we completed the 'Risk of bias' table for each included trial. In this we recorded our opinions of where each of the studies was vulnerable to bias.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

We carried out an intention‐to‐treat analysis. On the condition that more than 60% of people completed the study, we counted everyone allocated to the intervention, whether they completed the follow‐up or not. We assumed that those who dropped out had the negative outcome, with the exception of death. Where possible, we made efforts to convert outcome measures to binary data. This can be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into "clinically improved" or "not clinically improved". If the authors of a study had used a predefined cut‐off point for determining clinical effectiveness, we used this where appropriate. Otherwise we generally assumed that if there had been a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score, this could be considered as a clinically significant response. Similarly, we considered a rating of "at least much improved" according to the Clinical Global Impression Scale (Guy 1976) as a clinically significant response.

For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the fixed‐effect risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios (ORs) and that ORs tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). This misinterpretation then leads to an overestimate of the impression of the effect. When the overall results were significant we calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) and the number needed to harm (NNH) as the inverse of the risk difference.

2. Continuous data

2.1 Summary statistic

For continuous outcomes we estimated a mean difference (MD) between groups, based on the fixed‐effect model.

2.2 Endpoint versus change data

Where both final endpoint data and change data were available for the same outcome category, we have presented only final endpoint data. We acknowledge that by doing this much of the published change data may be excluded, but argue that endpoint data are more clinically relevant and that if change data were to be presented along with endpoint data, it would be given undeserved equal prominence. Where studies reported only change data, we contacted authors for endpoint figures, but if endpoint data were unavailable, we reported change data.

2.3 Skewed data

Normally distributed data: continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we applied the following standards to all data before inclusion:

(a) standard deviations and means were reported in the paper or were obtainable from the authors;

(b) when a scale started from the finite number zero, the standard deviation, when multiplied by two, was less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution, (Altman 1996);

(c) if a scale started from a positive value (such as PANSS which can have values from 30 to 210) we modified the calculation described above to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2SD> (S‐Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score. Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and end point and these rules can be applied to them. When continuous data are presented on a scale which includes a possibility of negative values (such as change on a scale), it is difficult to tell whether data are non‐normally distributed (skewed) or not.

We would have entered skewed data from studies of fewer than 200 participants in additional tables rather than into an analysis. Skewed data poses less of a problem when looking at means if the sample size is large and we would have entered them into a synthesis.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999). Where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we presented the data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation co‐efficients of their clustered data and to adjust for this using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will also present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect. We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that binary data presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intra‐class correlation co‐efficient (ICC) (Design effect = 1+ (m‐1)*ICC) (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported we have assumed it to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999). If cluster studies had been appropriately analysed taking into account ICC and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would have been possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we have presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we have not reproduced these data.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to include all people who had been randomised to either switching of medication or continuing on their previous antipsychotic. Where possible, we gave cases lost to follow‐up at the end of the study the worst outcome. For example, those lost to follow‐up for the outcome of relapse were treated in the analysis as having relapsed. Suicide was treated as relapse. We agreed these rules before knowing the studies included. The effects of inclusion of this assumption were tested with sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies without any comparison to judge clinical heterogeneity.

2. Statistical

2.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

2.2 Employing the I2 statistic

This provided an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance. We interpreted I2 estimates greater than or equal to 50% as evidence of high levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. These are described in section 10.1 of the Handbook (Higgins 2009). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects (Egger 1997). We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes. In other cases, where funnel plots were possible, we sought statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

Where possible we employed a fixed‐effect model for analyses. We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This does seem true to us; however, random‐effects does put added weight onto the smaller of the studies ‐ those trials that are most vulnerable to bias. For this reason we favour using the fixed‐effect model.

In this review, in the three instances where meta‐analysis was possible, the l2 statistic was substantially less than 50%. When true inter‐trial variability is low as denoted by low values of l2 statistics, the fixed‐effect model may give better precision estimate of a common effect.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

When we found heterogeneous results , we investigated the reasons for this. Where heterogeneous data substantially altered the results and we identified the reasons for the heterogeneity, we have not summated these studies in the meta‐analysis, but presented them separately and discussed them in the text.

Sensitivity analysis

We wished to investigate the sensitivity of the results of the primary outcomes to grouping drugs into broad families such as 'typical' and 'atypical'. This proved impossible as each comparison compared medications within the same broad families of drugs or did not give details of prior treatment.

Results

Description of studies

For description of the studies see: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

The original search identified 814 references from 83 studies. We conducted an update search in 2007 and identified an additional 266 studies and 625 new references. We searched the ISI citation index for each selected trial in order to identify further studies, and inspected the reference sections of selected studies for additional trials. We also identified five additional studies possibly relevant to this review (in addition to the above search methods, we also searched registers of ongoing clinical trials, and contacted representatives from major pharmaceutical companies) from which we have included two in the review. In total we selected 32 relevant trials, but we were able to include only four studies which were directly relevant for the review.

Included studies

We identified four studies which we could include. All were described as randomised. In one study, the participants were randomised to three switching strategies (Casey 2003). Only three were double blind (Cookson 1986; Eli Lilly 2004; Newcomer 2008).

1. Length of trials

One study (Casey 2003) reported data on short‐term follow‐up (up to 12 weeks).Two studies had follow‐up of 13 to 26 weeks (Eli Lilly 2004; Newcomer 2008). Only one study had follow‐up of one year's duration (Cookson 1986) .The ongoing study has an intended duration of one year (Tang 2003).

2. Participants

All but one study used clear operationalised criteria for diagnosis (Cookson 1986). The rest included participants with either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (DSM IV). The majority of participants in all studies except one (Cookson 1986) were male, and had a mean age in their mid to late thirties to early to mid forties.Two studies excluded participants with other axis 1 DSM IV diagnoses, suicide risk and substance dependence (Casey 2003; Newcomer 2008). One study excluded patients who had been on any other antipsychotic except olanzapine, which was the control antipsychotic (Eli Lilly 2004).

Being overweight or obese and/or having metabolic complications were an inclusion criteria in only three studies (Cookson 1986; Eli Lilly 2004; Newcomer 2008). In the other study it was difficult to make out if the participants were obese or overweight at entry, as they had provided only a mean body weight and no BMI (Casey 2003).

All the studies required patients to be stable mentally or be on a stable dose of medication. In the Casey 2003 study, there needed to be a reason for switching, like poor tolerability or inadequate response to previous medication.

3. Setting

Two studies were described as occurring in out‐patient settings (Casey 2003; Eli Lilly 2004). One study was done in a depot injection clinic (Cookson 1986). The setting was not mentioned in Newcomer 2008, but it could be inferred that this was conducted in an out‐patient setting as it had as one of its exclusion criteria an increase in symptoms requiring hospitalisation.

4. Study size

The study by Casey 2003 had the maximum participants (311). Two studies had between 100 and 200 participants (Eli Lilly 2004; Newcomer 2008). In the study by Eli Lilly 2004 the enrolment target was 340 but the study was terminated with only 33% of the original target enrolled. The fewest number of participants were enrolled in Cookson 1986 (19).

5. Interventions

Although all studies looked at the absolute effect of switching, only three studies (Cookson 1986; Eli Lilly 2004; Newcomer 2008) compared the effect of switching of antipsychotic medication with continuation of previous medication. In the study by Casey 2003, which looked at switching from previous antipsychotic medications to another, there was no comparative group continuing on the original medication. In this study baseline measures were compared to before and after switching of medication. For the purposes of this review we have called the different ways of switching 'Technique 1, 2 and 3'.

Technique 1 ‐ immediate initiation + immediate discontinuation of current antipsychotic.

Technique 2 ‐ immediate initiation + tapering of current antipsychotic.

Technique 3 ‐ titrating switch medication upwards + tapering of current antipsychotic .

In all studies except one, oral antipsychotics were used. In one study (Cookson 1986) depot antipsychotics were used.

6. Outcomes

Mean weight changes with measures of dispersion are reported in three studies (Cookson 1986; Eli Lilly 2004; Newcomer 2008). The percentage of people who experienced clinically significant weight gain or weight loss was reported in Casey 2003; mean weight change was also reported but it was not possible to use this as there were no measures of dispersion.

Changes in BMI are reported in Eli Lilly 2004 (mean and standard deviation) and Newcomer 2008 (number of people experiencing clinically relevant BMI increase).

The percentage of people with high waist circumference is reported in Newcomer 2008 but no other studies reported this outcome. Body fat and waist to hip circumference ratio was not an outcome measure in any of the studies.

Laboratory measures for Metabolic Syndrome were measured in two studies. Serum cholesterol, triglycerides HDL, LDL and blood glucose levels were measured in Eli Lilly 2004 and Newcomer 2008.

Time to relapse was the primary outcome measure in the study by Eli Lilly 2004. None of the other studies looked at relapse. Global state was assessed using the CGI I and CGI S scales in 2 studies (Casey 2003; Newcomer 2008).

Hospitalisation as one of the criteria for relapse was looked at in Eli Lilly 2004.

General functioning and behaviour were not an outcome measure in any of the studies.

Number of deaths was an outcome measure in only two studies; no deaths reported (Eli Lilly 2004; Newcomer 2008). Number of people discontinuing treatment was considered in three studies (Cookson 1986; Eli Lilly 2004; Newcomer 2008).

None of the studies looked at quality of life measures, economic outcomes or engagement with services.

All the studies looked at dropouts, but only three studies stated the reasons for discontinuation of treatment (Cookson 1986; Eli Lilly 2004; Newcomer 2008).

6.1 Outcome scales

Details of scales that provided usable data are shown below. Reasons for exclusions of data are given under 'Outcomes' in the 'Included studies' section.

6.1.1 Global state ‐ Clinical Global Impression Scale ‐ CGI Scale (Guy 1976). This is used to assess both severity of illness and clinical improvement, by comparing the conditions of the person standardised against other people with the same diagnosis. The review has looked at the two components of the scale, CGI ‐I (clinical improvement) and CGI‐S (severity of illness). A seven‐point scoring system is usually used, with low scores showing decreased severity and/or overall improvement. This scale was used in two studies (Casey 2003; Newcomer 2008).

6.1.2 Mental state ‐ Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale ‐ PANSS (Kay 1986) This schizophrenia scale has 30 items, each of which can be defined on a seven‐point scoring system varying from 1 ‐ absent to 7 ‐ extreme. This scale can be divided into three sub‐scales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms (PANSS‐P), and negative symptoms (PANSS‐N). A low score indicates lesser severity. PANSS was used in two studies (Casey 2003; Eli Lilly 2004).

6.2 Redundant data

We were unable to use some data on a number of outcomes (vital signs, concomitant medications and laboratory measures) used as there were no numerical data (Casey 2003; Newcomer 2008).Though specific scales were used to measure mental state and side effects, the results provided no usable data (Casey 2003; Cookson 1986; Eli Lilly 2004; Newcomer 2008).

6.3 Missing outcome

Primary outcome measures in the review were weight and metabolic measures, global state and mental state. In the four studies which we have included in the review, there were inconsistencies in reporting outcomes. All the primary outcomes were considered in three studies (Casey 2003; Cookson 1986; Eli Lilly 2004). In Casey 2003 and Cookson 1986, other measures of weight like BMI, waist circumference and metabolic syndrome were not considered. In the study by Eli Lilly 2004 relapse was used as an outcome to measure global state, but no other scales were used to measure global state. In this study a number of outcomes (waist circumference, health outcomes and resource utilisation) discussed in the methods section were not reported, probably due to the early termination of the study. Newcomer 2008 did not measure mental state.

Excluded studies

We excluded 28 studies from the review. One was a presentation on guidelines for the prescription of long‐acting atypical depot antipsychotics (Kane 2004). Another study (Ducate 2003) was excluded as there was no comparative group.

We excluded eight studies because there was no switching after randomisation (Alvarez 2006; Chrzanowski 2006; Brar 2005; Emsley 2005; CATIE ‐ Phase I ‐ 2006; Nasrallah 2001; STAR trials 2006; Wang 2006). We excluded six studies as they involved no switching of medications (CATIE ‐ Phase II ‐ 2006; Covell 1999; Kane 2005; Kane 2007; Newcomer 2006; Zhang 2004). Four studies were not randomised (Kim 2007; O'Halloran 2003; Robinson 2000; Su 2005). Weight and metabolic parameters were not measured as outcomes in one study (Irwin 2003,). We excluded another four studies because the primary aim of the switch was not as an intervention for weight gain or metabolic problems. This aim was difficult to consider as inferred as the switch was to olanzapine which is known to cause both weight gain and metabolic problems (Godleski 2003; Kinon 2000; Kinon 2004; Lee 2002). As this review was specifically looking at switching of medication as an intervention, we had to exclude one crossover trial (Kelly 2003). The first half of this study (eight weeks) was a comparison between high dose olanzapine and clozapine on various outcome measures including weight. The second half of the study involved crossover (switching). As data for weight and metabolic problems were not provided after the crossover (switching), we had to exclude the study. One study (Horacek 2004) provided no measure of dispersions for weight (the primary outcome for the review) and so it had to be excluded. We excluded Weiden Daniel 2003 because there were no data as per the original randomised groups (randomised to three switching strategies, from three different antipsychotic groups to ziprasidone). The data given were the pooled data from the three switching strategies for the three groups as per the original antipsychotic they were on prior to the switch to ziprasidone.

2. Awaiting assessment One hundred and sixty seven studies are awaiting assessment.

3. Ongoing studies One study (Tang 2003) is still ongoing. E‐mail (04/03/2008) contact from one of the authors stated that the study is ongoing and they have 50 patients recruited. However, they were planning to terminate the study soon due to funding issues. We have received no reply to further e‐mails requesting updates.

Risk of bias in included studies

For graphical representation of risk of bias please see Figure 1 and Figure 2.

1.

2.

Allocation

All included studies were reported as randomised. Only two studies attempted to describe the method of randomisation. In Casey 2003, randomisation was via a centralised telephone call‐in system, and Cookson 1986 used randomisation sequences (separate for males and females).The rest of the studies did not describe the randomisation or allocation concealment methods used. Concealment of allocation has repeatedly been shown to be of key importance in excluding selection biases (Jüni 2001).

Blinding

Three studies were double blind (Cookson 1986; Eli Lilly 2004; Newcomer 2008). Newcomer 2008 had a two‐week open‐label observation period where participants continued to receive their prior medication. Casey 2003 was open label. None of the double‐blind studies reported any tests for blinding, which is important to test minimisation of observation bias. Lack of blinding for objective outcomes like weight, BMI and metabolic syndrome (major primary objectives in this review) is less likely to cause bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Most studies used last observation carried forward (LOCF) or observed case data set. Reasons for discontinuation were stated in most studies.

In Newcomer 2008 in the LOCF and observed case data set there was 32% dropout.

In Eli Lilly 2004 the protocol was terminated early, with only a fraction of the intended enrolment. The drop‐out percentage was 33% percent. In Casey 2003, the drop‐out rate was 28%. In the Cookson 1986 study, only two people dropped out (11%).

All studies used LOCF and Newcomer 2008 conducted observed case analysis (observed cases, defined as those completing the trial) as well.

The drop‐out rates were different among the three groups in Casey 2003 with one group having more drop‐outs than the other.This was because more people withdrew consent in this group. Also all the randomised participants were not considered in reporting of some data. It is not clear what happened to the rest.

In the Cookson 1986 study, the only drop‐outs were in the intervention group who were weighed before withdrawal; one person gaining weight (2.9 kg) and the other losing it (0.9 kg).

There were more drop‐outs in the intervention group compared to control group in Eli Lilly 2004 and Newcomer 2008. The reasons for discontinuation were different in the two groups. It is therefore likely that these studies could be affected by attrition bias.

There were no numerical data on vital signs and concomitant medications in the Casey 2003 study. In Newcomer 2008 there was no data on vital signs, ECG and routine laboratory tests. In the Cookson 1986 study, even though methodology stated use of scales to measure mental state and side effects, there were no data reported in the results.

Selective reporting

We were unable to identify any intentional underreporting of outcomes in the trials with the possible exception of the Eli Lilly 2004 study. Here a number of outcomes stated in the protocol were not reported or analysed. Authors state that this was because the protocol was terminated early as only 33% of the target enrolment was reached.

Other potential sources of bias

Our judgement on the risk of bias in the different studies is shown in Figure 1

All but one trial (Cookson 1986) were supported by interested drug industries. In the Eli Lilly 2004 trial, protocol was terminated early prior to breaking the blind.This would not cause bias for the primary outcome (time to relapse) but could affect some outcomes of interest like weight, BMI and metabolic syndrome. We estimated the risk of bias to be unclear or high in the studies, and this is likely to overestimate positive effects.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

1. Switching ‐ new antipsychotic regimen versus continuation on previous regimen: 1a. different depot from depot – medium term (1 year)

(Table 1)

There was only one trial included in this group (Cookson 1986, n = 19).

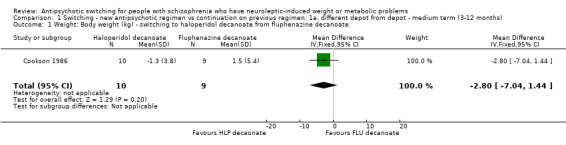

1.1 Weight: body weight

There was no clear difference between groups with an average loss of 2.80 kg by the end of the year in those allocated to haloperidol decanoate but the trial was small (n = 19) and confidence intervals wide (‐7.04 to 1.44).

1.2 Global state

We only found one proxy outcome for global state. Based on dose change (the need for extra medication) there was no clear difference between groups (1 RCT, n = 19, RR 0.18 CI 0.01 to 3.35). This finding was based on only two events.

1.3 Mental state

Two people were reported to have had a deterioration in mental state in the fluphenazine group but no significant difference between the two groups (1 RCT, n = 19, RR 0.18 CI 0.01 to 3.35).

1.4 Loss to follow‐up

Two people left from the group switched to haloperidol decanoate (1 RCT, n = 19, RR 4.55 CI 0.25 to 83.70) and again there was no clear difference between the groups.

2. Switching antipsychotic regimen versus continuation on previous regimen: 2. New atypical from olanzapine

(Table 2)

2.1 Weight: 1. Body weight (kg)

There was a statistically non‐significant mean weight loss of 1.94 kg in people who were switched from olanzapine to other medications compared to those who remained on it (2 RCTs, n = 287, CI ‐3.97 to 0.08). The average weight loss when switched to aripiprazole was 3.21 kg but the confidence intervals were very wide (‐9.03 to 2.61). The weight loss was 1.77 kg when switched to quetiapine (CI ‐3.93 to 0.39).

2.2 Weight: 2a. BMI increase

There was a significant difference in the number of patients who had clinically relevant BMI increase (more than 1 kg/m2) between aripiprazole (8 out of 88) and olanzapine (28 out of 85). This was based on 1 RCT (n = 173, RR 0.28, CI 0.13 to 0.57).

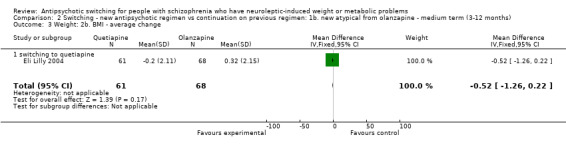

2.3 Weight: 2b. BMI average change

The average BMI was lower in the group switched to quetiapine compared to those who remained on olanzapine (1 RCT, n = 129 MD ‐0.52 CI ‐1.26 to 0.22), though this was not statistically significant.

2.4 Waist circumference increase

Even though fewer people who switched to aripiprazole had an increase in waist circumference compared to those remaining on olanzapine at the end of 16 weeks; the difference between the groups was not significant (1 RCT, n = 173, RR 0.92 CI 0.76 to 1.11).

2.5 Physiological measures: 1a. Average changes

2.5.1 Change in cholesterol

There was no difference in change in cholesterol levels in the two groups (1 RCT, n = 130, MD 0.02 CI ‐0.23 to 0.27).

2.5.2 LDL levels

There was no difference in LDL levels between the two groups. This was based on one RCT (n = 130, MD ‐0.02 CI ‐0.24 to 0.20).

2.5.3 HDL levels

With HDL levels as well there was no difference between the groups. There were no changes to the HDL levels in patients switched to quetiapine but HDL levels increased by 0.03 mmol/l in those remaining on olanzapine (1 RCT, n = 130 CI ‐0.05 to 0.11).

2.5.4 Triglyceride levels

No difference were observed between groups in triglyceride levels (1 RCT, n = 130, MD 0.13 CI‐0.18 to 0.44).

2.6 Physiological measures: 1b. Percentage changes

Only percentage changes were reported in one RCT which looked at switching to aripiprazole and continuing on olanzapine.

2.6.1 Cholesterol

There was a decrease in cholesterol by 9.5 % (n = 80 SE 1.5) in those switched to aripiprazole and 3.3% (n = 76 SE1.6) in those who remained on the olanzapine. The reported P value for this difference was 0.005.

2.6.2 Triglycerides

The triglycerides decreased by 14.46 % in those switched to aripiprazole (n = 54 SE 4.5 which was estimated from a graph) and increased by 5.3% in the group continuing on olanzapine (n = 61 SE 5.6‐ estimate from graph). The P value was 0.002.

2.6.3 LDL levels

The percentage decrease for low density lipoproteins was 11.2% (n = 80 SE 2.5) in the group switched to aripiprazole and it was 4.7% (n = 76 SE 2.7) in the group which stayed on olanzapine.The P value was 0.072.

2.6.4 HDL levels

The high density lipoproteins increased by 1.7% (n = 80 SE 1.8) in the aripiprazole group and decreased by 5.9% (n = 76 SE1.7) in the olanzapine group. The P value was 0.002.

2.7 Physiological measures: 1c. Average changes ‐ sugar

2.7.1 Fasting insulin level

There were no difference between the two groups in the fasting insulin level. A very small decrease of 0.3 μU/ml was noted in the aripiprazole group (1 RCT, n = 155 CI ‐4.04 to 3.44).

2.7.2 Insulin levels

No clear difference between groups in insulin levels. There was an average increase in insulin of 8.63 in the quetiapine group but the confidence intervals were wide (1 RCT, n = 125 CI‐8.82 to 26.08).

2.7.3 c‐peptide levels

There was no difference between the two groups in the c‐peptide levels. The aripiprazole group had a very small increase of 0.36ng/ml (1 RCT, n = 153 CI ‐0.19 to 0.91).

2.7.4 Fasting blood glucose

There was a significant difference between the groups in fasting blood glucose.The glucose levels decreased by an average of 2.53 mg/dL in the groups switched to aripiprazole and quetiapine from olanzapine (2 RCTs, n = 280 CI ‐2.94 to ‐2.11). Both the studies had used different units of measurement for glucose. Millimoles per litre were converted to milligrams per decilitre for analysis.

2.8 Global state: 1a. Relapse

There was no difference in the number of relapses in the group switched to quetiapine and in those continuing on olanzapine (1 RCT, n = 133 RR1.31 CI 0.55 to 3.11).

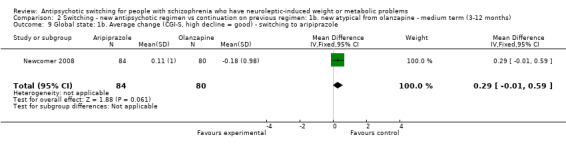

2.9 Global state: 1b. Average change

There was no difference between groups in the average changes to the CGI S scores at the end point of treatment in those switched to aripiprazole or those who stayed on olanzapine (1 RCT, n = 164, MD 0.29 CI ‐0.01 to 0.59).

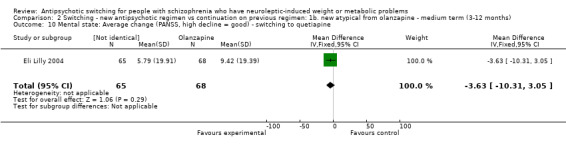

2.10 Mental state

There was no difference between the groups in the average PANSS scores. The group switched to quetiapine had decreased by 3.63 in the PANSS score but the confidence intervals were wide (‐10.31 to 3.05). The mean change in the PANSS scores were reported but the standard deviation had to be calculated from the reported P values.

2.11 Loss to follow‐up

Data from the two studies in this group indicate that people are less likely to leave the study early if they are on olanzapine (RR 1.65 CI 1.21‐2.25). In the study by Newcomer 2008, 36% dropped out in the aripiprazole group compared to 25% in the olanzapine group. In the Eli Lilly 2004 study, the drop‐out was 56% in those switched to quetiapine and only 20% in those continuing on olanzapine. Leaving the study early data may be used as a proxy measure for the acceptability of treatment.

2.12 Adverse events: 1. Serious adverse events

There was no difference between the groups which switched medication (aripiprazole, quetiapine) and those who remained on olanzapine (2 RCTs, n = 305 RR 0.99 CI 0.48 to 2.07).

2.13 Adverse events: 2. Treatment emergent adverse events

There was no difference in the treatment‐induced side effects between the groups which switched medication (aripiprazole, quetiapine) and those who remained on olanzapine (2 RCTs, n = 302 RR1.07 CI 0.92 to 1.24).The data were heterogenous (I2 statistic 51%).

3. Switching ‐ techniques: to aripiprazole from previous regimen

(Table 3) Technique 1 = Immediate initiation + immediate discontinuation of current antipsychotic.

Technique 2 = immediate initiation + tapering of current antipsychotic.

Technique 3 = titrating switch medication upwards + tapering of current antipsychotic.

3.1 Weight: Gain (≥7% from baseline)

There was no clear difference between any different technique for antipsychotic switching on the outcome of weight gain (technique 1 versus 2: 1 RCT, n = 207, RR 0.61 CI 0.15 to 2.47; technique 1 versus 3: 1 RCT, n = 205, RR 0.99 CI 0.20 to 4.79; technique 2 versus 3: 1 RCT, n = 206, RR1.63 CI 0.40 to 6.66).

3.2 Global state: 1a. Average change (CGI‐I, high = good)

3.2.1 Technique 1 versus technique 2

There was no significant difference in the CGI I scores between the groups. The CGI I scores showed a decline of 0.14 in the group switched to aripiprazole immediately compared to the group where the dose of previous medication was gradually tapered (1 RCT, n = 203 CI ‐0.49 to 0.21).

3.2.2 Technique 1 versus technique 3

There was no significant difference in the CGI I scores between the groups. The CGI I scores showed a mean difference of 0.01 (1 RCT, n = 203 CI ‐0.34 to 0.36).

3.2.3 Technique 2 versus technique 3

We found no significant difference between groups with the CGI I scores. There was a very small increase of 0.15 in these scores in the first group (1 RCT, n = 204 CI ‐0.20 to 0.50).

3.3 Global state: 1b. Average change (CGI‐S decline = good)

3.3.1 Technique 1 versus technique 2

We found no significant difference between groups with the CGI S scores. The immediate initiation and the immediate discontinuation group had a decrease of 0.06 compared to the second group (1 RCT, n = 203 CI‐0.27 to 0.15).

3.3.2 Technique 1 versus technique 3

We found no significant difference between groups with the CGI S scores. There was a mean decrease of 0.04 in the immediate initiation and immediate discontinuation group (1 RCT, n = 203 CI ‐0.24 to 0.16).

3.3.3 Technique 2 versus technique 3

We found no significant difference between groups with the CGI S scores (mean difference 0.02, 1 RCT, n = 204 CI ‐0.20 to 0.24).

3.4 Mental state: average change (PANSS, high decline = good)

3.4.1 Technique 1 versus technique 2

We found no clear difference between the groups but the PANSS score was higher by 0.59 in the group where aripiprazole was initiated immediately and the current antipsychotic was discontinued without tapering (1 RCT, n = 197 CI ‐4.51 to 5.69).

3.4.2 Technique 1 versus technique 3

We found no difference between groups but the PANSS score showed an increase of 2.52 in the immediate initiation + immediate discontinuation group (1 RCT, n = 198 CI ‐2.39 to 7.43).

3.4.3 Technique 2 versus technique 3

There was no difference between the two groups. The group where the medication was initiated immediately and the current antipsychotic tapered and stopped indicated a small increase in the PANSS score by 1.93 (1 RCT, n = 201 CI ‐2.63 to 6.49).

3.5 Loss to follow‐up: 1a. Any reason

Fewer people were lost to follow‐up in the group comparing technique 2 to technique 3 compared to the other groups (1 RCT, n = 207 RR 0.82 CI 0.70 to 0.97).There was no difference between the other groups for this outcome (technique 1 vs 2 1 RCT, n = 208 RR 1.04 CI 0.87 to 1.26; technique1 vs 3 n = 207 RR 0.86 CI 0.73 to1.01).

3.6 Loss to follow‐up: 1b. Various specific reasons

3.6.1 to 3.6.5: Technique 1 versus technique 2

We found no difference between the groups in the numbers lost to follow‐up for different reasons including adverse events (1 RCT, n = 208, RR 0.60 CI 0.23 to 1.59), worsening of illness (1 RCT, n = 208, RR1.00 CI 0.43 to 2.30), withdrawal of consent (1 RCT, n = 208, RR 0.58 CI 0.24 to 1.42) non‐compliance (1 RCT, n = 208, RR 4.00 CI 0.45 to 35.19) and other causes (1 RCT, n = 208, RR 2.50 CI 0.50 to 12.60).

3.6.6 to 3.6.10: Technique 1 versus technique 3

We found no difference between the groups in the numbers lost to follow‐up for different reasons including adverse events (1 RCT, n = 207, RR 0.99 CI 0.33 to 2.97), worsening of illness (1 RCT, n = 207 RR 1.24 CI 0.51 to 3.01), withdrawal of consent (1 RCT, n = 207 RR 6.93 CI 0.87 to 55.35) non‐compliance (1 RCT, n = 207 RR 3.96 CI 0.45 to 34.85) and other causes (1 RCT, n = 207, RR1.24 CI 0.34 to 4.48).

3.6.11 to 3.6.15: Technique 2 versus technique 3

The number that was lost to follow‐up through withdrawing of consent was more in the immediate initiation + tapering of current antipsychotics group compared to the titrating switch medication upwards and tapering current antipsychotic group favouring the second group (1 RCT, n = 207, RR 11.88 CI 1.57 to 89.74). There was no difference between the groups for other reasons like adverse events (1 RCT, n = 207, RR 1.65 CI 0.62 to 4.38), worsening of illness (1 RCT, n = 207, RR 1.24 CI 0.51 to 3.01), non‐compliance (1 RCT, n = 207, RR 0.99 CI 0.06 to 15.62) and other causes (1 RCT, n = 207, RR 0.50 CI 0.09 to 2.64).

3.7 Adverse events: any event

3.7.1 Technique 1 versus technique 2

There was no difference between groups (1 RCT, n = 207, RR 1.00 CI 0.91 to 1.10).

3.7.2 Technique 1 versus technique 3

There was no clear difference between the groups (1 RCT, n = 205, RR1.10 CI 0.98 to1.23).

3.7.3 Technique 2 versus technique 3

There was no clear difference between the groups (1 RCT, n = 208, RR 1.12 CI 1.00 to 1.26).

Discussion

Summary of main results

1. Switching ‐ new antipsychotic regimen versus continuation on previous regimen: 1a. different depot from depot – medium term (1 year)

Weight gain whilst taking depot medication is a real problem (Silverstone 1988) and we were surprised to only find one very small trial (Cookson 1986, n = 19). From such a tiny trial no clear effects would be expected but this study shows that such studies are possible and, if larger, could be informative.

1.1 Body weight

There was a mean weight loss of 1.3 kg in the switch group (S.D 3.8).The fluphenazine group showed a mean increase in weight by 1.5 kg (S.D 5.4) thereby favouring the intervention group (switch to haloperidol decanoate). Here the authors had not given measures of dispersion for the mean weight change. So the standard deviation had to be calculated using the individual weights from the graph provided.

1.2 Global state

No scales were used to assess global state in this study. Two out of nine patients in the control group (continuation on fluphenazine decanoate) deteriorated and needed extra medication. Using measurable scales would have made this finding more robust.

1.3 Mental state

No valid scales were used to assess mental state, but two people among the fluphenazine group were found to have a slight deterioration in their mental state. This may suggest that patients on haloperidol had a better outcome.

1.4 Loss to follow‐up

Two people left the study early in the group switched to haloperidol decanoate, but there were no dropouts in the group continuing on fluphenazine decanoate. The reasons for drop‐out were unclear. As drop‐outs could be a proxy indicator of tolerability, this may indicate that people tolerate fluphenazine better than haloperidol. However, such a conclusion should be treated with caution given that the study group was very small.

2 Switching antipsychotic regimen versus continuation on previous regimen: 2. new atypical from olanzapine

2.1 Weight: 1. Body weight (kg)

Weight gain is a well‐recognised side effect, particularly with the newer antipsychotics (Allison 1999; Casey 2004; Homel 2002). Two studies in this group showed a mean weight loss of 1.95 kg when switched to aripiprazole and quetiapine from olanzapine. The individual studies showed an average weight loss of 3.21 kg when switched to aripiprazole and 1.77 kg when switched to quetiapine. The sample size was small in both studies and they were medium term in duration.

2.2 Weight: 2a. BMI increase

2.3 Weight: 2b. BMI average change