Abstract

Ventricular arrhythmias associated with mitral valve prolapse (MVP) and the capacity to cause sudden cardiac death (SCD), referred to as ‘malignant MVP’, are an increasingly recognised, albeit rare, phenomenon. SCD can occur without significant mitral regurgitation, implying an interaction between mechanical derangements affecting the mitral valve apparatus and left ventricle. Risk stratification of these arrhythmias is an important clinical and public health issue to provide precise and targeted management. Evaluation requires patient and family history, physical examination and electrophysiological and imaging-based modalities. We provide a review of arrhythmogenic MVP, exploring its epidemiology, demographics, clinical presentation, mechanisms linking MVP to SCD, markers of disease severity, testing modalities and management, and discuss the importance of risk stratification. Even with recently improved understanding, it remains challenging how best to weight the prognostic importance of clinical, imaging and electrophysiological data to determine a clear high-risk arrhythmogenic profile in which an ICD should be used for the primary prevention of SCD.

Keywords: Mitral valve prolapse, sudden cardiac death, ventricular arrhythmia, mitral annular disjunction, implantable cardioverter defibrillator

Malignant (arrhythmogenic) mitral valve (MV) prolapse (MVP), a syndrome referring to arrhythmias associated with a prolapsing MV apparatus with the capacity to cause sudden cardiac death (SCD), is an increasingly recognised, albeit rare, phenomenon. Highlighted by Nishimura et al. in 1985, the concept of a specific subset of MVP patients being at risk of developing a malignant arrhythmia and subsequent SCD has since been the subject of several autopsy and observational studies.[1–11]

MVP is best diagnosed using echocardiography in the parasternal (or apical) long-axis window, defined as a >2 mm systolic displacement of either mitral leaflet into the left atrium (LA) relative to the mitral annular plane.[12] In addition to complex ventricular arrhythmias (VAs) and SCD, complications of MVP include mitral regurgitation (MR), congestive heart failure, infective endocarditis and cerebral embolic events. The prevalence of MVP in the general population is approximately 2–3%, occurring most commonly due to fibromyxomatous changes in one or both leaflets.[13,14]

The early identification and treatment of malignant MVP is made difficult due to the limited data available and a lack of evidence-based guidelines. There is renewed interest regarding the spatially and/or time-altered myocardial electrical conductions that cause malignant VAs secondary to a prolapsing MV, with a view to a greater understanding of its epidemiology, mechanism, diagnosis and link to public health in the broader context of SCD.[15] What also remains unknown is how best to identify and stratify MVP patients who may be at risk of arrhythmia in order to prevent SCD and provide appropriate and timely management. Risk stratification remains a significant challenge, and optimal treatment has not yet been achieved.

The yearly incidence of SCD, generally defined as death due to a cardiovascular cause occurring within 1 h of the onset of symptoms, ranges from 15 to 159 per 100,000 and is attributed to coronary artery disease in approximately 80% of cases.[16] Our recent 2018 and 2019 systematic reviews and meta-analyses reported a yearly SCD incidence of 0.14% in the overall MVP population, with MVP in 11.7% of cases of SCD where the cause remained undetermined.[8,10]

Accurate risk stratification of MVP with a likelihood of malignant VA is an important clinical and public health issue, which would allow for more precise and targeted management and the consideration of appropriate ICD therapy for the primary and secondary prevention of SCD in this cohort.

Epidemiology

The clinical signs of MVP first described by Cuffer and Barbillon in the 19th century on the basis of a midsystolic click were erroneously attributed as being of pericardial or extracardiac origin.[17] Clinical descriptions by Barlow and Pocock, and subsequently Criley et al., in the mid-20th century gave rise to its current nomenclature.[18,19] More recently, the diagnosis of MVP has been firmly based on imaging findings using 2D (and previously M-mode) echocardiography.[20,21]

The reported prevalence of MVP in the general population has varied in different studies due to varying diagnostic criteria and study demographics. In the late 1980s, Levine et al. redefined the understanding of the dynamic saddle-shaped MV anatomy and the need to correct the previously defined diagnostic criteria that had incorrectly assumed the MV to be in a Euclidian plane during the entire cardiac cycle.[20,22]

The initially reported 5% prevalence of MVP diagnosed using M-mode echocardiography criteria in the 1983 Framingham Heart Study (with a recognised limitation of a White-only population) was later revised to 2.4% based on current definitions.[23,24] A 2004 Canadian study of three different ethnic groups reported an overall prevalence of 2.7% (not significantly different between groups).[24] A large 2021 Taiwanese study reported an MVP prevalence of 3.3% in their young adult population.[13] Many studies have reported an evenly distributed prevalence of MVP across gender and age groups.[23,25,26]

MVP is a heterogeneous disease classified according to its aetiology and pathology, and can present as an isolated abnormality or secondary to other conditions, such as connective tissue disorders, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or polycystic kidney disease.[27–29] Primary MVP (disease of the MV apparatus) can be sporadic or familial, with autosomal dominance the most common mode of inheritance.[30] Multiple loci have been identified in genetic linkage analysis for familial MVP, including 16p11.2-p12.1 in myxomatous mitral valve prolapse 1 (MMVP1), 11p15.4 in myxomatous mitral valve prolapse 2 (MMVP2) and 13q31.3-32.1 in myxomatous mitral valve prolapse 3 (MMVP3).[31,32] Pathologically, classic MVP (Barlow’s disease phenotype) presents with markedly thickened leaflets (≥5 mm) secondary to degeneration and myxoid infiltration, which, in turn, causes leaflet redundancy with chordal elongation. This contrasts with the non-classic fibroelastic deficiency (FED) variant, whereby deficiency of connective tissue causes chordal thinning and eventual rupture.[33–35]

Complications including infective endocarditis, progression to severe MR and the need for valvular intervention are significantly higher in patients with classic MVP.[36,37] High-risk features for cardiac mortality and morbidity include older age, depressed left ventricular (LV) function, dilated LA, flail leaflet, MR and AF.[38]

Arrhythmogenic Mitral Valve Prolapse Causing Sudden Cardiac Death

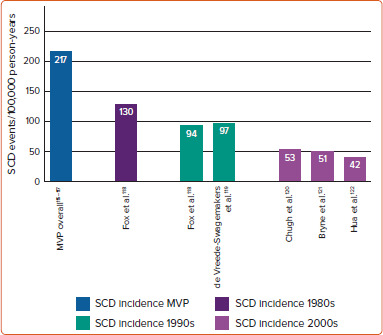

The incidence of SCD in the MVP population remains uncertain. In 1985, Nishimura et al. reported an SCD incidence of 16–40 per 10,000 (0.2– 0.4%)/year in 237 minimally symptomatic or asymptomatic patients with MVP.[1] The 2001 review by Basso et al. of major causes of SCD in patients aged <40 years (six studies; 1960–99) reported MVP in 12% (the third most common finding) of autopsy-diagnosed cases.[2] A prospective study in 2018 of 356 patients with primary MR (177 with MVP diagnosed using cardiac magnetic resonance [CMR]) without other significant cardiac disease described a 1.2% annual event rate of SCD or malignant VA associated with MVP.[39] More recently, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of cases and studies reporting SCD events in patients with MVP, which estimated 217 SCD events per 100,000 person-years and a yearly SCD incidence of 0.14% (Figure 1).[8,10]

Figure 1: Sudden Cardiac Death Incidence in Mitral Valve Prolapse Versus Population Studies.

MVP = mitral valve prolapse; SCD = sudden cardiac death. Source: Han et al. 2018.[8] Reproduced under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC 4.0 licence.

Using these aforementioned event rates (MVP prevalence 2.4% and a yearly SCD incidence of 0.14%), assuming a 2023 global population of 8.1 billion, 421,848 of the 194.4 million people estimated to have MVP would be at risk of SCD per year.[10,23,24] Proportionately, this is in keeping with the 2020 calculations of Muthukumar et al. using the 2019 population of the US (328 million), which estimated that between 13,000 and 26,000 of the estimated 6.5 million MVP cohort was at risk of SCD per year.[40] The review of Muthukumar et al. highlights that although MVP’s SCD event rate may be less than that of other non-ischaemic arrhythmogenic syndromes such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, its relative contribution towards SCD in the general adult population is the same, if not greater, due to its significantly higher prevalence.[40]

However, it remains difficult to accurately quantify the number of annual SCD events occurring in the global MVP cohort attributable solely to isolated arrhythmogenic MVP (aMVP). Compounded by the relatively low incidence of events and associated difficulty of conducting randomised or large observational studies, the cause ofdeath also remains undetermined in up to 22.1% of cases of SCD, with MVP found in up to 12% of autopsy- diagnosed SCD cases.[2,10]

Demographics, Clinical Presentation and Predictors of Arrhythmic Events

SCD secondary to isolated MVP (iMVP) induced VA has been classically considered a syndrome predominantly affecting young women with bileaflet prolapse; associated with biphasic or inverted T waves in the inferior ECG leads, complex or pleomorphic premature ventricular contractions (PVC) and PVC-triggered ventricular fibrillation (VF).[41,42]

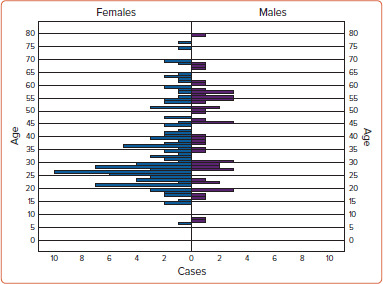

In a systematic review of 79 articles describing 161 cases of MVP (123 with iMVP) with SCD or cardiac arrest, we found the median age of presentation was 30 years (range 6–79 years), with 69% female (Figure 2).[8] Similarly, from the Australian National Coronial Information System database between 2000 and 2018, in a large series of cases of autopsy-determined iMVP and sudden death with documented cardiac arrest rhythms, we identified 71 cases of iMVP with a mean (±SD) age of 49 ± 18 years from an overall 77,221 cardiovascular deaths; however, notably, only 51% were female (Supplementary Table 1).[11]

Figure 2: Age at Time of Death or Cardiac Arrest in Mitral Valve Prolapse According to Sex.

Source: Han et al. 2018.[8] Reproduced under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC 4.0 licence.

Interestingly, a 2020 prospective analysis of 595 patients with MVP with a mean (±SD) age of 65 ± 16 years also reported that male sex was associated with the presence of arrhythmia (61%; p=0.0008), as were bileaflet prolapse (BiMVP), leaflet redundancy, mitral annular disjunction (MAD), increased LA size and LV end-systolic diameter and T wave inversion/ST-segment depression.[6] Further, those with arrhythmia in this cohort were older than those without (mean [±SD] age 68 ± 15 years versus 63 ± 17 years, respectively).[6] The findings of these larger cohort studies certainly bring in to question the relevance of the historically reported young and female predominance based on prior case reports and autopsy studies. These newer and larger studies may be more reflective of the contemporary general population, and possibly less subject to previous inherent publication and referral bias.[9]

It is important to highlight the wide spectrum of preceding symptoms and clinical presentations that make risk stratification of malignant MVP difficult. Supplementary Table 2, adapted from our previous systematic review, details baseline characteristics in cases of iMVP and SCD or cardiac arrest.[8] Eighty-six per cent of affected individuals had no family history of SCD, 21% had no prior symptoms and 46% of cases occurred during normal daily activity (home, non-physical work or during commute).

Mitral Annular Disjunction and Its Association with Arrhythmias and Sudden Cardiac Death

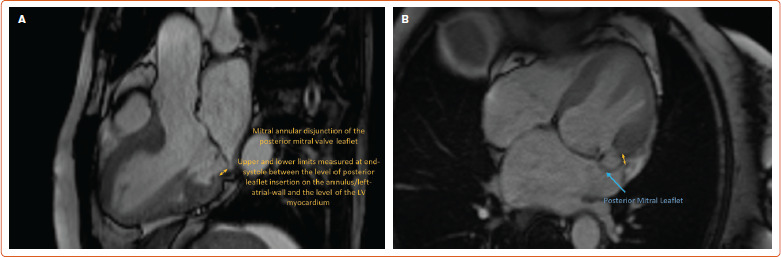

VA occurrence correlates with the severity of MAD (Table 1); an abnormal atrial displacement of the MV leaflet hinge point observed only at the insertion of the posterior mitral leaflet (limited anteriorly by the mitro- aortic fibrous continuity and therefore not involving the anterior leaflet), causing systolic separation between the ventricular myocardium and the mitral annulus, with upper and lower limits measured (CMR or echocardiography in the parasternal long-axis view during end-systole) respectively between the level of posterior leaflet insertion on the annulus/left-atrial-wall and the level of the LV myocardium (Figure 3).[43–46] In contrast to the normal mitral annulus attached simultaneously both to the atrial and ventricular myocardium, in MAD the ventricular myocardium (having lost its basal attachment) forms the margin of the ‘MAD trench’.[47]

Table 1: Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Findings in Patients with Mitral Annular Disjunction Stratified by the Presence of Ventricular Arrhythmias and Sudden Cardiac Death.

| MAD Associated with VA | MAD Associated with SCD |

|---|---|

|

MAD = mitral annular disjunction; NSVT = non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; SCD = sudden cardiac death; VA = ventricular arrhythmias.

Figure 3: Cardiac MRI Long-axis Views Displaying Mitral Annular Disjunction in End Systole.

A: Three-chamber imaging plane. Inferolateral atrioventricular junction being assessed for disjunction. Yellow double-headed arrow: Longitudinal mitral annular disjunction distance in the posterolateral wall, illustrating the abnormal atrial displacement of the mitral valve leaflet hinge point observed at the insertion of the posterior mitral leaflet, causing systolic separation between the ventricular myocardium and the mitral annulus. B: Four-chamber imaging plane. Illustrating the lateral extension of mitral annular disjunction, comparison of these two planes (A and B) highlights the ability for disjunction to occur circumferentially around parts of the annulus. Yellow double-headed arrow: The site of the mitral annular disjunction and the upper and lower limits used in measuring the systolic separation between the ventricular myocardium and the mitral annulus.

A 2019 systematic review of 19 studies found that a pooled rate of 32.6% (95 of 291 patients in three studies) and 50.8% (66 of 130 patients in three studies) of patients with MVP and myxomatous MV, respectively, had concurrent MAD.[48]

Faletra et al. describe two morphologically distinct MAD entities: ‘pseudo’ (or ‘systolic’) MAD and ‘true’ MAD.[43] In pseudo (or systolic) MAD, the posterior mitral leaflet, despite being inserted normally in diastole at the ventricular–atrial junction, gives an illusion of apparent but not true separation between the leaflet–atrial junction and ventricular crest during systole. A phenomenon only possible with MVP and excessive posterior MV leaflet tissue, this is due to the billowing posterior leaflet being indiscernible from adjacent LA wall against which it is forced and juxtaposed. This contrasts with true MAD, whereby displacement of the LA–MV leaflet junction is clearly present regardless of diastole or systole. This highlights the importance of dynamic examination of all imaging modalities (i.e. frame-by-frame analysis centred on the MV). The varied morphology and position of the highly dynamic mitral annulus throughout systole (from which both MVP and MAD are defined) requires careful image-based analysis and interpretation by individuals with knowledge of the disease to clearly distinguish between these two entities and avoid MAD’s under- or over-reporting.

Interestingly, in a cohort of 116 patients with MAD (90 with concurrent MVP), of whom 14 had severe arrhythmic events, Dejgaard et al. reported that MVP was not associated with VA and proposed MAD alone is an arrhythmogenic entity.[44] MAD was detected circumferentially around a large part of the mitral annulus (median 150°; interquartile range 90°– 210°) and exclusively along the posterior mitral valve leaflet hinge point, interspersed with normal tissue in 33 (52%) of the patients in whom these circumferential measurements were obtained (no significant difference between MAD patients with and without MVP). The clinical significance of this 3D circumferential characterisation of MAD and its relationship with interspersed regions of apparently normal annular tissue remains unknown.

Carmo et al. reported that the severity of MAD (in 21 of 38 patients with myxomatous MV disease) was significantly correlated with the occurrence of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) on Holter monitoring, MAD >8.5 mm being a strong predictor.[49]

Further, the 2020 prospective analysis of 595 patients with MVP reported MAD was associated with a sevenfold (OR 6.97) more likely occurrence of severe VA (ventricular tachycardia [VT] ≥180 BPM and/or proven history of VT/VF, indicating a need for an ICD) and a threefold (OR 3.27) more likely occurrence of mild/moderate VA.[6] The presence of T wave inversion or ST-segment depression was associated with a greater than twofold (OR 2.30) increased risk of mild/moderate VA, with severe VA having an eightfold increased risk (OR 8.04) and being independently associated with excess mortality. The presence of redundant leaflets was fourfold (OR 3.85) more likely to cause severe VA.[6] Overall mortality after arrhythmia diagnosis was strongly associated with arrhythmia severity. Whether a minimum number of beats was required ≥ 180 BPM to satisfy their definition of severe VA is unclear, highlighting the importance of future studies to explore whether longer durations or other thresholds, including complexity of NSVT rather than just rate, may be more specific.

The available studies clearly question whether MAD arrhythmic syndrome and malignant MVP are mutually exclusive therapeutic targets or may, indeed, combine to form a clinical spectrum.[7] Whether the annular structural integrity and potential disappearance of MAD achieved by MV surgery (MVS) may reduce VA burden further, due to the suturing of the ring and prosthesis and the joining of the annulus to the LV myocardium, can at this stage only be hypothesised.[50,51] Similarly, whether additive therapy for MAD and stabilisation of the mitral annulus might further reduce VA burden in those MVP patients who undergo percutaneous edge-to-edge mitral valve repair warrants clarification.[52]

Bileaflet Valve Prolapse and Mitral Regurgitation Severity

Multiple studies have shown BiMVP to be a more malignant subtype than single-leaflet MVP (SiMVP). In a cohort of 1200 patients observed between 2000 and 2009, Sririam et al. reported BiMVP in 10 of 24 (42%) patients (16 women; median age 33.5 years) who died from idiopathic out-of- hospital cardiac arrest, all of whom had ICDs.[53] Review of appropriate ICD therapies during follow-up (median 1.8 years) reported that 8 of 13 (62%) involved BiMVP patients and, importantly, only BiMVP was associated with VF recurrences requiring ICD therapy. Compared with SiMVP, BiMVP was more common in women (9/10 [90%] versus 7/14 [50%]; p=0.04), was associated with biphasic or inverted T waves (7/9 [77.8%] versus 4/14 [29%]; p=0.04) and had a higher prevalence of ventricular bigeminy (9/9 [100%] versus 1/10 [10%]; p<0.0001), VT (7/9 [78%] versus 1/10 [10%]; p=0.006) and PVCs originating from the outflow tract alternating with papillary muscle (PM) or fascicular region (7/9 [78%] versus 2/10 [20%]; p=0.02).[53]

A 2016 retrospective and matched cohort study of 18,786 BiMVP, SiMVP and control patients reported that BiMVP was associated with the highest rates of VT, albeit with no statistically significant differences reported in the rates of VF/cardiac arrest or ICD deployment between groups.[54] However, that study also reported paradoxical findings of BiMVP being associated with a lower rate of all-cause mortality compared with the SiMVP and control groups.

Primary MR is most commonly caused by a prolapsing degenerative MV (Carpentier type II classification), with MR being the second most common valvular disorder worldwide.[34,55] Although primary MVP causes mild, trivial or no MR in most patients, it remains the most common cause of moderate or severe MR requiring intervention in resource-abundant countries.[56–58] In a cohort of 833 patients first diagnosed with asymptomatic MVP using current echocardiographic criteria, 38% and 46% of patients had no or only mild MR, respectively.[38]

Among 610 MVP (FED or Barlow’s disease) patients with significant primary (moderate-to-severe) MR referred for MVS, van Wijngaarden et al. reported that patients who experienced symptomatic VA were significantly younger, more often female, more often showed T wave inversions, were more likely to have MAD and mitral annual dilatation and had lower global longitudinal strain and prolonged mechanical dispersion.[59]

Table 2 lists the proportions of BiMVP and MR severities in cases of MVP and SCD or cardiac arrest based on our 2018 systematic review.[8] Of 57 cases of SCD or cardiac arrest with iMVP, BiMVP was present in 40 (70%) and, importantly, 83% of cases were associated with non-severe MR.

Table 2: Imaging Findings in Cases of Mitral Valve Prolapse and Sudden Cardiac Death or Cardiac Arrest.

| Imaging Findings | All Cases | iMVP | Non-iMVP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leaflet involvement* | n=83 | n=57 | n=26 |

| Bileaflet | 57 (69) | 40 (70) | 17 (65) |

| Posterior leaflet | 23 (28) | 15 (26) | 8 (30) |

| Anterior leaflet | 3 (4) | 2 (4) | 1 (4) |

| MR severity† | n=38 | n=23 | n=15 |

| Nil/trivial | 9 (24) | 6 (26) | 3 (20) |

| Mild | 12 (32) | 9 (39) | 3 (20) |

| Moderate | 8 (21) | 4 (17) | 4 (27) |

| Severe | 9 (24) | 4 (17) | 5 (33) |

Unless indicated otherwise, values are expressed number (percentage). *Determined using echocardiography and/or autopsy information. †Diagnosed on angiography or echocardiography. iMVP = isolated mitral valve prolapse; MR = mitral regurgitation. Source: Han et al. 2018.[8] Reproduced under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC 4.0 licence.

Similarly, in a cohort of 56 MVP patients (15 of whom had iMVP), it was reported based on clinical and autopsy findings those with MVP dying suddenly without another recognised condition were more likely to be young women with a lower frequency of MR (7% versus 38%; p=0.02).[60] This finding is also supported by the 2020 prospective analysis of 595 patients with MVP, which reported severe VA was not independently associated with MR severity or LV ejection fraction (LVEF).[6]

These studies highlight that VA and SCD in the MVP cohort do occur even in the absence of severe MR, highlighting perhaps a distinct pathophysiology, and hence an invariably more difficult risk stratification challenge compared with those MVP patients with significant MR. Although combinations of BiMVP and MR severities are found throughout the entire risk spectrum profile and perhaps fail to offer clear clinical risk stratification in everyday clinical practice, these findings highlight the importance of performing more thorough investigations in high-risk phenotype/symptomatic patients even in the absence of severe MR.

Autopsy and Histopathological Findings

In 2015, Basso et al. investigated from a histological perspective, the structural basis of ventricular electrical instability in 43 cases of MVP deemed the only cause of SCD.[4] Patchy fibrosis in the LV myocardium was closely linked to the MV, along with LV scarring at the level of the PM and adjacent free wall in all and of the inferobasal wall in 88% of cases. Supporting these findings was significant late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) found on contrast-enhanced CMR in their cohort of living MVP patients with complex VA (70% bileaflet) at the equivalent level of the PM and inferobasal LV wall compared with minor-arrhythmic controls (93% versus 14%; p<0.001).[4] That multiple studies have shown PVCs to be mostly of PM origin and the most characterised cause of VF in MVP, in addition to arrhythmias being shown to originate from the inferobasal LV wall, highlights the likely arrhythmogenic role and instability of these focal substrates.[4,53,61,62]

Han et al. described the histopathological findings of iMVP compared with non-iMVP in cases of SCD from an Australian national cohort over an 18- year period; patients with another possible cause of death or a combination of MVP and other cardiac illness were excluded from the iMVP group.[11] Individuals with iMVP and sudden death had increased cardiac mass compared with matched individuals (matched for age, sex, height and weight) with non-cardiac death, but similar cardiac mass compared with matched individuals with cardiac death. Further, LV fibrosis in cases of iMVP and sudden death predominantly (85%) involved the subendocardial–midmural aspect of the ventricle.[11]

We also reported non-uniform LV remodelling with both localised and generalised LV fibrosis in 17 cases of iMVP SCD (with other potential causes of death excluded) identified from the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine (Australia).[63] Compared with a non-cardiac death control group matched for age, sex and body mass index, LV (anterior, lateral and posterior) and interventricular septum fibrosis was increased in the iMVP SCD group (all p<0.001), with similar amounts of right ventricular fibrosis between groups (p=0.62).[63] In addition, within the iMVP SCD group, lateral and posterior wall LV fibrosis was significantly greater than in the anterior wall and interventricular septum (p<0.001).[63] Although there were certain limitations given the nature of that autopsy- based study, including the absence of specific clinical characteristics, electrocardiography, Holter monitoring and being unable to categorically exclude conditions that may cause sudden arrhythmic death, the study’s findings encourage future similar histopathological studies using entire heart specimens for complete microscopic analysis.

In a 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis, Nalliah et al. evaluated 14 autopsy studies of MVP in sudden death and SCD (5,235 cases; mean [±SD] age 35.8±12.4 years; 21.5% female).[10] The overall prevalence of MVP in SCD was 1.9% (95% CI [0.8–3.4]), with MVP observed in 11.7% (95% CI [5.9–19.1]) of SCD cases where the cause of death remained undetermined.

Barlow’s Disease Versus Fibroelastic Deficiency

Barlow’s disease and FED are the two main causes of MVP. Myxomatous MVP (Barlow’s disease) is characterised grossly by leaflet thickening and redundancy with interchordal hooding, chordal elongation/thickening and annular dilatation with calcification.[64] FED is more classically associated with leaflet and chordal thinning with a higher probability of rupture and subsequent prolapse with varying degrees of MR.[35]

MAD is more prevalent in the Barlow’s disease phenotype than in FED and has been shown to occur more frequently in cases of BiMVP.[45,49,65] However, the maximum MAD distance was shown not to differ significantly between the two phenotypes in one study.[65]

Postulated Mechanisms of Arrhythmia Linking Mitral Valve Prolapse to Sudden Cardiac Death

The most widely supported and substantiated mechanistic link between MVP and VA (malignant MVP) is considered to be an interaction between an acute abnormal mechanical stretch of the PM during systolic leaflet prolapse causing afterdepolarisation-triggered PVCs, and progressive hypertrophy with fibrosis most often localised in the basal/mid-inferolateral LV or PM secondary to repeated traction of the prolapsing leaflets.[2,66,67] PVCs originating from the PM or fascicular regions, and alternating with the LV outflow tract, are associated with the highest risk of SCD fuelled by stretch-induced abnormal automatism in the Purkinje fibres and a fibrotic substrate that increases susceptibility to trigger activities and re-entry pathways.[4,39–42,47,53,61,68,69]

Autonomic tone has also been shown to affect rates of VA. Significantly higher daily adrenaline excretion has been reported in patients with severe VA, with stretch-activated membrane channels in the compliant ventricular myocardium and changes in [Ca2+]i during stretch also having the capacity to induce more frequent PVCs.[70–72]

Regarding the pathophysiology of VA in MVP patients with MAD, Basso et al. formulated their hypothesis of a cascade of morphofunctional abnormalities of the mitral annulus in which MAD and a systolic curling (slippage of annulus) motion form the basis of a mechanical trigger and abnormal substrate.[3] Having previously shown more pronounced MAD and larger end-systolic and end-diastolic mitral annular diameters in MVP patients with arrhythmias and LGE than in those without, Basso et al. hypothesise that the excessive mobility of the leaflets with posterior systolic curling is responsible for a paradoxical increase in annulus diameter during systole and myxomatous leaflet degeneration, with mechanical stretch of the inferobasal wall and PM resulting in myocardial hypertrophy with replacement-type fibrosis and scarring.[73]

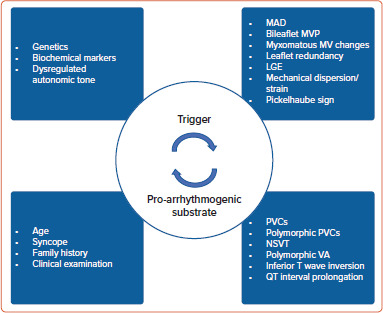

Whether VA in patients with MVP occurs in both the presence and absence of fibrosis as identified by LGE on CMR remains unknown. Although several of the aforementioned studies[4,39,53,61,73] have identified the presence of myocardial fibrosis and its likely association with VA, fibrosis in certain cases may, in fact, represent a delayed catalytic substrate fuelling an already arrhythmogenic disease process. That is, malignant MVP may best be interpreted as a function reliant on both a trigger and a substrate; a combination of mechanically induced PVCs, altered MV annulus as seen in MAD, bileaflet prolapse with or without MR, susceptible fibrosis and dysregulated autonomic tone working in unison to produce a sustained VA (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Schematic Interpretation of Malignant Mitral Valve Prolapse.

MVP may best be interpreted as a function reliant on both a trigger and proarrhythmogenic substrate in a genetically susceptible phenotype with various markers of high-risk disease. LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; MAD = mitral annular disjunction; MV = mitral valve; MVP = mitral valve prolapse; NSVT = non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; PVCs = premature ventricular contractions; VA = ventricular arrhythmia.

Risk Stratification and Testing

Diagnosis of aMVP requires the presence of MVP (with or without MAD), VA that is frequent (currently defined as ≥5% PVC burden, albeit based on limited evidence) or complex (NSVT, VT, VF) and the absence of any other well-defined arrhythmic substrate.[47] Two main arrhythmic MVP phenotypes are recognised in the 2022 European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) consensus statement: MVP with severe degenerative MR and severe myxomatous MVP independent of MR severity (Table 3).[47]

Table 3: Arrhythmic Mitral Valve Prolapse Phenotypes.

| MVP with Severe Degenerative MR | Severe Myxomatous MVP Independent of MR Severity |

|---|---|

|

LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; MAD = mitral annular disjunction; MR = mitral regurgitation; MVP = mitral valve prolapse; SCD = sudden cardiac death; VA = ventricular arrhythmias. Source: Sabbag et al. 2020.[47]

Screening MVP patients for high-risk arrhythmogenic profiles, who are at risk of SCD, remains a significant clinical challenge. How to identify which patients with MVP should undergo a structured risk stratification, and when this should be done, remains mostly unknown. More importantly, in those patients found to have risk factors but no syncope, sustained VA or previous cardiac arrest, there is no clear consensus regarding what further investigations and monitoring are warranted. However, although it indeed remains a clinical conundrum what to do once these higher-risk patients are identified, the following clinical, imaging and electrophysiological subsections highlight the importance of performing further investigations in patients once diagnosed with aMVP, providing both context and influence in clinicians’ intensities of detecting severe VAs in these patients.

Device-based therapy for VA to prevent SCD is available, and its appropriate application is lifesaving. Preventing inappropriate or unnecessary use is essential based on clinical risk, patient psychological health and health economic grounds. It is therefore important that workable risk stratification approaches to determine treatment are developed. Improved knowledge of malignant VA and SCD related to MVP, either untreated or treated, is important to ensure that choice of patient for a given therapy is made appropriately using the best available evidence. Even with improved knowledge and awareness of various risk markers, it is still relatively unknown how best to weight prognostic importance and at what threshold an ICD should be implanted for the primary prevention of SCD.

Clinical History and Examination

FED is typically diagnosed in patients presenting with acute symptoms of chordal rupture aged >60 years, compared with the identification of generally asymptomatic Barlow’s disease patients found to have a murmur during examination at a younger age, usually between 40 and 60 years.[35] The Barlow’s disease murmur is a high-pitched, late systolic murmur associated with a mid-to-late systolic click compared with the harsh and holosystolic murmur heard in FED patients.[35,64] Despite careful physical examination, the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosing MVP clinically with auscultation compared with the gold standard echocardiography has varied significantly between different clinical series.[74]

Although the incidence of chest pain, palpitations, dyspnoea on exercise and syncope has been reported as similar between those with and without MVP, a systematic review by Han et al. shows the importance of eliciting any history of previous syncope, which was reported in 35% of MVP patients with malignant arrhythmias or SCD, with syncope also shown to be more frequently reported in MVP patients with documented severe VA.[6,8,23,75,76]

Documented 12-Lead ECG Recordings

ECG recordings of MVP out-of-hospital cardiac arrests show a high prevalence of NSVT and PVCs. PVCs of PM and fascicular origin are the most commonly cited and most thoroughly characterised triggers of VF in MVP.[42,77] The reported incidence of PVCs using Holter monitoring in the adult MVP population has been shown to vary. Savage et al. investigated dysrhythmias associated with MVP in the general population, reporting that 54 of 61 (89%) subjects with MVP had one or more PVCs (range 1–1,834) during 24-h ECG monitoring, with complex or frequent PVCs (Lown Grade 2 or higher) detected in >50% of those with MVP.[78]

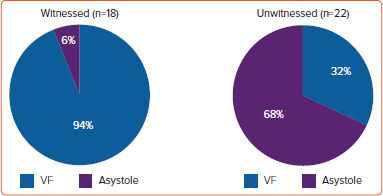

In a comprehensive review of 71 cases of autopsy-proven iMVP and SCD from the Australian National Coronial Information System database, VF was found to be the primary arrhythmia (94%) in patients with iMVP who experienced a witnessed cardiac arrest (Figure 5).[11]

Figure 5: Initial Cardiac Rhythm in Cases of Autopsy- determined Isolated Mitral Valve Prolapse.

Source: Han et al. 2020.[11] Reproduced under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC 4.0 licence.

ECG abnormalities in this cohort include T wave inversion most commonly in the inferolateral leads, as well as QT interval prolongation in some, but not all, studies.[4,6,41,59,79–82] Interestingly, QT interval prolongation has been independently associated with VAs among MVP patients and shown to correlate with more severe leaflet prolapse and thickening of the anterior leaflet, and is of potential relevance when considering the concept of MVP being best interpreted a function reliant on both a trigger and substrate.[3,6,83]

The hypothesised stretch-induced shortening of action potential duration, decrease in resting diastolic potential and subsequent development of afterdepolarisations (thought secondary to diastolic contact of the prolapsing leaflets with the ventricular myocardium or stretch of the PM or valve itself) may have the capacity to trigger VA in the QT-prolonged proarrhythmogenic substrate.[84–89] However, whether QT prolongation is associated with mortality in the setting of malignant MVP remains unknown.

Electrophysiological Studies

The role of electrophysiological studies (EPS) using programmed ventricular stimulation (PVS) to identify (predict) patients with MVP at risk of SCD events remains unclear, as highlighted by a systematic review that reported on the outcome of 22 patients with iMVP and documented SCD who had undergone EPS with PVS.[8,47] Of those reported cases, PVS yielded findings of sustained monomorphic VT (5%), NSVT (23%), VF (18%) and non-inducibility of VAs (55%).[8] Although the induction of monomorphic VT is considered more specific, these findings mechanistically support a PVC-triggered arrhythmia hypothesis in most cases as opposed to a re- entrant scar-mediated process.

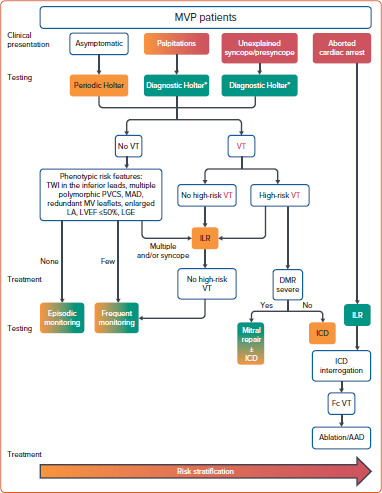

Although EPS have not been specifically included in the EHRA consensus statement risk stratification scheme due to lack of conclusive evidence, there may be a role for a nuanced electrophysiological approach in highly specialised centres with experience managing this cohort of patients (Figure 6).[47] The ability to assess for complexity of PVC/NSVT and whether it remains sustained, as well as whether monomorphic or polymorphic VT can be induced with minimal stimulus, may be additional factors used in decision making at specialised centres.

Figure 6: Risk Stratification Scheme.

Risk stratification aiming at assessing the risk of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in patients with MVP, involving two phases based on the clinical and imaging context and the uncovered arrhythmia. In the absence of VT, phenotypic risk features will trigger the intensity of screening for arrhythmia. Green boxes indicate green heart consensus statements (recommended/ indicated treatment strongly supported by authors’ consensus or scientific evidence), and yellow boxes indicate yellow heart consensus statements (treatment may be used or recommended). ‘High-risk’ indicates sustained VT, polymorphic non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NVST), fast (>180 BPM) NSVT, VT/NSVT resulting in syncope. *Additional ECG monitoring method may be used, such as loop recorders. AAD = antiarrhythmic drug therapy; DMR = degenerative mitral regurgitation; Fc = Focal; ILR = implantable loop recorder; LA = left atrium; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; MAD = mitral annular disjunction; MV = mitral valve; MVP = mitral valve prolapse; PVCs = premature ventricular contractions; TWI = T wave inversion; VT = ventricular tachycardia. Source: Sabbag et al. 2020.[47] Reproduced with permission from Oxford University Press.

Multimodality Imaging: Echocardiography and Cardiac Magnetic Resonance

Various imaging modalities can be used to identify markers associated with increased risk of SCD and VA in patients with MVP; however, many need further validation in larger cohorts. Conventional and speckle- tracking transthoracic echocardiography are non-invasive, easily accessible and able to detect and quantify parameters, including MAD, annular tissue velocity, mechanical strain, dispersion and myocardial work index.[40] The high spatial resolution offered by CMR is best suited to detecting focal or diffuse tissue alterations, such as fibrosis.

Echocardiogram

Severe myxomatous changes, MAD and BiMVP found on echocardiography are associated with an increased risk of VA.[8,44,47,53] Thickened redundant leaflets of ≥5 mm was the only variable associated with sudden death on multivariate analysis in a series of MVP patients reported by Nishimura et al.[1]

Myocardial velocities have been used as imaging markers of stretch- mediated triggered activity. Miller et al. reported patients with myxomatous BiMVP and lateral mitral annular velocities ≥16 cm/s were more likely to have had a malignant VA (67% versus 22%; p<0.08).[41]

Muthukumar et al. reported the observation of a spiked tissue Doppler velocity profile, termed the Pickelhaube sign, in keeping with a hypercontractile state of the basal to mid-lateral myocardium.[90] Further, LGE was not present in any patients without the Pickelhaube sign (versus 33% with).[90] These systolic velocities are generally much greater in patients with aMVP than in those with non-aMVP or the control population and are thought to represent myocardial stretch secondary to the sharp tugging of prolapsing leaflets.[91]

The distribution of mechanical strain within the myocardium, a measure of tissue deformation and a surrogate of cardiac function, can help delineate underlying pathological substrates. Supranormal strain (>24%) within the posterolateral LV (basal, mid-posterior and lateral wall segments) is common in patients with MVP, along with subnormal strain (<18%) in the corresponding opposite basal septal wall segments.[40]

Mechanical dyssynchrony describes the pathologically varied timings of contraction and relaxation between myocardial segments and can be quantified using mechanical dispersion analysis with speckle-tracking echocardiography. Previously associated with VA in patients with cardiomyopathies, dyssynchrony has been shown to cause regional alterations in protein expression that may increase arrhythmia susceptibility.[92–94] More recently, mechanical dispersion among patients with MVP was reported to be significantly higher in the presence of VA and a significant predictor of arrhythmic risk on multivariate analysis.[81]

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance

Using CMR, Han et al. showed in 2008 that 10 of 16 MVP patients (versus none of 10 controls) had focal regions of LGE in the PM suggestive of fibrosis, findings that are consistent with the previously discussed 2015 histological and CMR findings of Basso et al.[4,61] Eight of the 10 MVP patients with PM fibrosis had complex VA (couplets or non-sustained VT).[61] Three other patients with Holter monitor data had either no VA or a few isolated ventricular ectopic (VE) beats with no LGE on PM.[61]

A prospective cohort analysis by Kitkungvan et al. in 2018, which followed 356 primary MR patients (177 MVP, 179 non-MVP; median follow-up 1,354 days) reported that: LV fibrosis on CMR was a major associate of arrhythmic events and most prevalent in the MVP group (36.7% versus 6.7% in non- MVP patients; p<0.001); fibrosis increased with MR severity; and fibrosis occurred in specific areas of the LV, indicative of a mechanistic pathology.[39] Eight MVP patients had either VT or aborted SCD and, of these, five had mid-wall or patchy myocardial fibrosis in the inferobasal region of the LV.[39] Hence, CMR is a useful imaging modality to detect localised fibrosis (LGE) in the papillary muscle and inferolateral LV region, indicative of substrate for VA.

Groeneveld et al. recently reported in their 2022 retrospective multicentre cohort study that MAD in the inferolateral wall was more prevalent in 72 patients with idiopathic VF than in 72 healthy controls (7 [11%] versus 1 [1%], p=0.024).[95] With MAD observed almost equally in patients both with and without MVP, these CMR imaging findings support MAD at the inferolateral region being a distinctive imaging data point able to identify patients predisposed to idiopathic VF.

Biochemical and Genetic Factors

Although a validated molecular pathophysiology of mechanical stress- induced fibrosis remains elusive and potential clinical application remains uncertain, some data are available.

Scheirlynck et al. reported patients with MAD and VA had increased levels of soluble suppression of tumourigenicity-2 (sST2), reduced LVEF and a higher proportion of fibrosis on LGE compared with arrhythmia-free patients.[96] Further, Blomme et al., in 2019, hypothesised that abnormal perception and responsiveness of MV interstitial cells to mechanical stress may induce an inappropriate adaptive remodelling progressively leading to myxomatous disease.[97] Cyclical stretch induced an early and transient overexpression of transforming growth factor-beta 2 and caused lengthened expression of connective tissue growth factor, considered a hallmark of fibrotic diseases.[97]

Management

To date, there are limited data and a lack of evidence-based guidelines regarding the treatment of malignant MVP. Management for those considered at risk of VA and SCD involves medical therapy with or without electrophysiological or device-based treatment. Current treatment options include traditional antiarrhythmic medications, cardiac ablation and ICD placement, with a proposed testing and treatment algorithm offered in the EHRA consensus statement (Figure 6).[47]

Medical

Medical management is non-specific and includes β-blockers, calcium channel blockers and other antiarrhythmic agents focused primarily on reducing PVC burden and improving symptoms. The recent EHRA consensus statement suggests that for patients with aMVP: symptomatic severe MR not eligible for surgery should be treated with optimal heart failure medication; β-blockers, sotalol and amiodarone are reasonable treatment options for PVC-induced cardiomyopathy; and the need for an ICD should be assessed in all cases of aMVP with the aid of a risk stratification algorithm (Figure 6).[47]

Electrophysiological: Ablation and ICD Implantation

Electrophysiological management includes catheter-based ablation as well as implantation of ICDs for primary or secondary prevention of SCD. Indications for ablations of PVCs or VAs, regardless of underlying arrhythmogenic substrate and relating not only to an aMVP cohort, include patients with symptoms refractory to medical therapy, when medical therapy is not tolerated, when ablation is preferred over long-term pharmacotherapy or when there is associated impairment of LV function.[47,98,99]

In a cohort of 152 patients who underwent 170 consecutive procedures for ablation of focal VA, 25 of whom had MVP diagnosed by echocardiography, the association between LV papillary muscle VA and reported MVP did not adversely affect the acute or medium-term outcomes of ablation.[100] MVP was present in 9 of 23 (39%) patients who underwent ablation of the LV PM, compared with none of 129 (0%) patients at other sites (p<0.001), with median LVEF improving from 40% to 54% following ablation in those with cardiomyopathy (p=0.007).[100]

In a cohort of 14 patients with BiMVP and symptomatic VA refractory to medical management, catheter-based ablation of VE originating from fascicular and PM foci improved symptoms and reduced the number of appropriate ICD shocks, with VE burden reduced in those without previous cardiac arrest.[42] Importantly, these reductions occurred even in the absence of LGE on CMR (performed before index ablation in five patients), supportive of a lack of fixed scar-related substrate and in keeping with the observation that SCD in patients with MVP generally results from pleomorphic or polymorphic rather than monomorphic VT.[40]

The role of ICDs for the primary prevention of SCD has been established by several clinical trials reporting a mortality reduction, with implantation indicated: in patients with LVEF ≤35% despite 3 months of optimal medical therapy; for secondary prevention of SCD (with documented VF or sustained VT) occurring in the absence of reversible causes; and for arrhythmic cardiomyopathies in the presence of a combination of risk markers.[98]

Given a lack of data relating specifically to the MVP cohort, the need for an ICD should be continually assessed for each patient. In addition to previously indicated ICD guidelines (i.e. LVEF ≤35%, secondary prevention for documented VF, sustained VT or haemodynamically unstable VT), the EHRA consensus statement suggests primary prevention ICDs should be strongly considered in patients presenting with unexplained syncope and documented high-risk VA (sustained VT not originating from the right ventricular (RV) or LV outflow tract, spontaneous polymorphic NSVT and rapid monomorphic NSVT >180 BPM).[47] Further, ICDs may be reasonable based on expert consensus (Table 11 in the EHRA consensus statement) in those with a combination of two phenotypic risk factors (T wave inversion in the inferior leads, repetitive documented polymorphic PVCs, MAD phenotype, redundant MV leaflets, enlarged LA, LVEF ≤50% or mitral apparatus LGE) and one high-risk feature (haemodynamically tolerated sustained VT, NSVT or unexplained syncope).[47]

Although extremes of the clinical spectrum (asymptomatic with no high- risk phenotypic features versus aborted cardiac arrest) offer relatively straightforward decision making, it remains unknown at what combined threshold of risk markers an ICD is most warranted in the intermediary grey zone of this cohort.

Implantable Loop Recorders

Implantable loop recorders may offer a useful alternative for detecting arrhythmias in those patients not initially fulfilling primary prevention ICD criteria but with high-risk features of aMVP and previously inconclusive shorter-duration Holter monitoring, and for those with intermediate risk factors and phenotypic features including LGE on CMR.[47] The important role of implantable loop recorder monitoring in this subset of patients has been emphasised in the EHRA consensus statement’s graphical abstract (Figure 6).[47] Patients with multiple phenotypic risk features and/or syncope, and found subsequently to have high-risk VT on implantable loop recorders, are recommended for ICD insertion.

Mitral Valve Surgery

Current US (2020) and European (2021) surgical guidelines do not consider arrhythmia burden when managing patients with valvular heart disease.[101,102] Instead, algorithms based on the severity of MR, symptoms, LV dynamics, new-onset AF, pulmonary artery pressure and level of operability risk are used. MV surgery for MR improves survival benefit regardless of symptom status or preoperative LVEF and/or RV ejection fraction.[103–105] Reduction in MR and a pathologically elevated preload should, in principle, decrease congestive symptoms and myocardial wall stress and improve haemodynamic performance.

Data on the efficacy of MV surgery in treating VA burden in patients with MVP and degenerative MR remain limited, with risk stratification remaining difficult and the indication for surgery not absolute.[6,106,107] The timing of the operation (e.g. prior to malignant substrate formation), the technique used (repair, replacement, annuloplasty, cryoablation) and whether the degree of MR before and after surgery impact the risk of SCD are questions that remain unanswered.

There is very limited evidence from case reports regarding the efficacy of surgical cryoablation during MVS in patients with a history of complex VA, with long-term outcomes and recommendations not yet defined.[108–110]

Vohra et al. recently reported three malignant-MVP patients (refractory to medical therapy) who underwent surgical cryoablation at the time of MV surgery and remained free of VA during follow-up, with no detrimental effect on valve function secondary to the cryoablation lesions.[110]

Conclusion

Despite limited data, there have been many recent advances in our understanding of this complex aMVP disease. Our rapidly improving knowledge of the underlying mechanisms for VA and SCD associated with MVP, the associated clinical risk factors, and electrophysiological and imaging risk markers, continues to make identifying the subset of MVP patients at highest risk of SCD less challenging. However, the prognostic importance and relative contribution of each individual factor regarding overall risk of developing VA and SCD remains unknown and warrants further study.

There is a clearly demonstrated need for large prospective studies specifically addressing this issue, with appropriate level of rhythm monitoring, multimodality imaging (including echocardiography and CMR) and further research at the genetic and molecular levels. Continued translational and clinical research is essential to develop a workable, evidence-based risk stratification system that more clearly defines in whom and at what level intervention (including ICD) should be considered.

Clinical Perspective

Risk stratification of VAs and SCD associated with MVP is an important clinical and public health issue allowing for more precise and targeted management.

Risk stratification involves a combination of clinical history, rhythm monitoring, electrophysiological and cardiac imaging investigations.

Management includes medical therapy and consideration of electrophysiological, device-based or surgical treatment.

Further research is essential to develop an evidence-based risk stratification system, particularly for when primary prevention ICD should be considered.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Nishimura RA, McGoon MD, Shub C et al. Echocardiographically documented mitral-valve prolapse. Long-term follow-up of 237 patients. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1305–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198511213132101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basso C, Calabrese F, Corrado D, Thiene G. Postmortem diagnosis in sudden cardiac death victims: macroscopic, microscopic and molecular findings. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;50:290–300. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00261-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basso C, Iliceto S, Thiene G, Perazzolo Marra M. Mitral valve prolapse, ventricular arrhythmias, and sudden death. Circulation. 2019;140:952–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basso C, Perazzolo Marra M, Rizzo S et al. Arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse and sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 2015;132:556–66. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Essayagh B, Sabbag A, Antoine C et al. The mitral annular disjunction of mitral valve prolapse: presentation and outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol Imaging. 2021;14:2073–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2021.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Essayagh B, Sabbag A, Antoine C et al. Presentation and outcome of arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:637–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han HC, Calafiore P, Teh AW et al. Arrhythmic mitral annulus disjunction and mitral valve prolapse: components of the same clinical spectrum? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:739. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han HC, Ha FJ, Teh AW et al. Mitral valve prolapse and sudden cardiac death: a systematic review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e010584. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han HC, Teh AW, Hare DL et al. The clinical demographics of arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2689–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nalliah CJ, Mahajan R, Elliott AD et al. Mitral valve prolapse and sudden cardiac death: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Heart. 2019;105:144–51. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han HC, Parsons SA, Teh AW et al. Characteristic histopathological findings and cardiac arrest rhythm in isolated mitral valve prolapse and sudden cardiac death. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015587. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.015587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zoghbi WA, Adams D, Bonow RO et al. Recommendations for noninvasive evaluation of native valvular regurgitation: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography developed in collaboration with the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017;30:303–71. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu PY, Tsai KZ, Lin YP et al. Prevalence and characteristics of mitral valve prolapse in military young adults in Taiwan of the CHIEF Heart study. Sci Rep. 2021;11:2719. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81648-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devereux RB, Jones EC, Roman MJ et al. Prevalence and correlates of mitral valve prolapse in a population-based sample of American Indians: the Strong Heart Study. Am J Med. 2001;111:679–85. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00981-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korovesis TG, Koutrolou-Sotiropoulou P, Katritsis DG. Arrhythmogenic mitral valve prolapse. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2022;11:e16. doi: 10.15420/aer.2021.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stiles MK, Wilde AAM, Abrams DJ et al. 2020 APHRS/HRS expert consensus statement on the investigation of decedents with sudden unexplained death and patients with sudden cardiac arrest, and of their families. Heart Rhythm. 2021;18:e1–50. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuffer M, Barbillion M. New research into the galloping heart sound. Arch Gen Med. 1887;19:129–49. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barlow JB, Pocock WA. The significance of late systolic murmurs and mid-late systolic clicks. Md State Med J. 1963;12:76–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Criley JM, Lewis KB, Humphries JO, Ross RS. Prolapse of the mitral valve: clinical and cine-angiocardiographic findings. Br Heart J. 1966;28:488–96. doi: 10.1136/hrt.28.4.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine RA, Handschumacher MD, Sanfilippo AJ et al. Three- dimensional echocardiographic reconstruction of the mitral valve, with implications for the diagnosis of mitral valve prolapse. Circulation. 1989;80:589–98. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.3.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine RA, Stathogiannis E, Newell JB et al. Reconsideration of echocardiographic standards for mitral valve prolapse: lack of association between leaflet displacement isolated to the apical four chamber view and independent echocardiographic evidence of abnormality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11:1010–9. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(98)90059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levine RA, Triulzi MO, Harrigan P, Weyman AE. The relationship of mitral annular shape to the diagnosis of mitral valve prolapse. Circulation. 1987;75:756–67. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.4.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freed LA, Levy D, Levine RA et al. Prevalence and clinical outcome of mitral-valve prolapse. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907013410101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theal M, Sleik K, Anand S et al. Prevalence of mitral valve prolapse in ethnic groups. Can J Cardiol. 2004;20:511–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bryhn M, Persson S. The prevalence of mitral valve prolapse in healthy men and women in Sweden: an echocardiographic study. Acta Med Scand. 1984;215:157–60. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1984.tb04986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flack JM, Kvasnicka JH, Gardin JM et al. Anthropometric and physiologic correlates of mitral valve prolapse in a biethnic cohort of young adults: the CARDIA study. Am Heart J. 1999;138:486–92. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(99)70151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowen J, Boudoulas H, Wooley CF. Cardiovascular disease of connective tissue origin. Am J Med. 1987;82:481–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petrone RK, Klues HG, Panza JA et al. Coexistence of mitral valve prolapse in a consecutive group of 528 patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy assessed with echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:55–61. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90137-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hossack KF, Leddy CL, Johnson AM et al. Echocardiographic findings in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:907–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810063191404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delling FN, Rong J, Larson MG et al. Familial clustering of mitral valve prolapse in the community. Circulation. 2015;131:263–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Tourneau T, Mérot J, Rimbert A et al. Genetics of syndromic and non-syndromic mitral valve prolapse. Heart. 2018;104:978–84. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grau JB, Pirelli L, Yu PJ et al. The genetics of mitral valve prolapse. Clin Genet. 2007;72:288–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anyanwu ACMD, Adams DHMD. Etiologic classification of degenerative mitral valve disease: Barlow’s disease and fibroelastic deficiency. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;19:90–6. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delling FN, Vasan RS. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of mitral valve prolapse: new insights into disease progression, genetics, and molecular basis. Circulation. 2014;129:2158–70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Wijngaarden AL, Kruithof BPT, Vinella T et al. Characterization of degenerative mitral valve disease: differences between fibroelastic deficiency and Barlow’s disease. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2021;8:23. doi: 10.3390/jcdd8020023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delling FN, Rong J, Larson MG et al. Evolution of mitral valve prolapse: insights from the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2016;133:1688–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marks AR, Choong CY, Sanfilippo AJ et al. Identification of high-risk and low-risk subgroups of patients with mitral- valve prolapse. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1031–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198904203201602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Avierinos JF, Gersh BJ, Melton LJ 3rd et al. Natural history of asymptomatic mitral valve prolapse in the community. Circulation. 2002;106:1355–61. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000028933.34260.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitkungvan D, Nabi F, Kim RJ et al. Myocardial fibrosis in patients with primary mitral regurgitation with and without prolapse. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:823–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muthukumar L, Jahangir A, Jan MF et al. Association between malignant mitral valve prolapse and sudden cardiac death: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1053–61. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller MA, Dukkipati SR, Turagam M et al. Arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2904–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Syed FF, Ackerman MJ, McLeod CJ et al. Sites of successful ventricular fibrillation ablation in bileaflet mitral valve prolapse syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016;9:e004005. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.116.004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faletra FF, Leo LA, Paiocchi VL et al. Morphology of mitral annular disjunction in mitral valve prolapse. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2022;35:176–86. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2021.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dejgaard LA, Skjølsvik ET, Lie Ø et al. The mitral annulus disjunction arrhythmic syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1600–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Essayagh B, Iacuzio L, Civaia F et al. Usefulness of 3-tesla cardiac magnetic resonance to detect mitral annular disjunction in patients with mitral valve prolapse. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124:1725–30. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mantegazza V, Volpato V, Gripari P et al. Multimodality imaging assessment of mitral annular disjunction in mitral valve prolapse. Heart. 2021;107:25–32. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sabbag A, Essayagh B, Barrera JDR et al. EHRA expert consensus statement on arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse and mitral annular disjunction complex in collaboration with the ESC Council on valvular heart disease and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society, by the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society, and by the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society. Europace. 2022;24:1981–2003. doi: 10.1093/europace/euac125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bennett S, Thamman R, Griffiths T et al. Mitral annular disjunction: a systematic review of the literature. Echocardiography. 2019;36:1549–58. doi: 10.1111/echo.14437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carmo P, Andrade MJ, Aguiar C et al. Mitral annular disjunction in myxomatous mitral valve disease: a relevant abnormality recognizable by transthoracic echocardiography. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2010;8:53. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-8-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eriksson MJ, Bitkover CY, Omran AS et al. Mitral annular disjunction in advanced myxomatous mitral valve disease: echocardiographic detection and surgical correction. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1014–22. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Essayagh B, Mantovani F, Benfari G et al. Mitral annular disjunction of degenerative mitral regurgitation: three- dimensional evaluation and implications for mitral repair. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2021;32:165–75. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2021.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wunderlich NC, Ho SY, Flint N, Siegel RJ. Myxomatous mitral valve disease with mitral valve prolapse and mitral annular disjunction: clinical and functional significance of the coincidence. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2021;8:9. doi: 10.3390/jcdd8020009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sriram CS, Syed FF, Ferguson ME et al. Malignant bileaflet mitral valve prolapse syndrome in patients with otherwise idiopathic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:222–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nordhues BD, Siontis KC, Scott CG et al. Bileaflet mitral valve prolapse and risk of ventricular dysrhythmias and death. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27:463–8. doi: 10.1111/jce.12914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lung B, Delgado V, Rosenhek R et al. Contemporary presentation and management of valvular heart disease: the EURObservational research programme valvular heart disease II survey. Circulation. 2019;140:1156–69. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luxereau P, Dorent R, De Gevigney G et al. Aetiology of surgically treated mitral regurgitation. Eur Heart J. 1991;12((Suppl B)):2–4. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/12.suppl_b.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dziadzko V, Dziadzko M, Medina-Inojosa JR et al. Causes and mechanisms of isolated mitral regurgitation in the community: clinical context and outcome. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:2194–202. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Freed LA, Benjamin EJ, Levy D et al. Mitral valve prolapse in the general population: the benign nature of echocardiographic features in the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1298–304. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Wijngaarden AL, de Riva M, Hiemstra YL et al. Parameters associated with ventricular arrhythmias in mitral valve prolapse with significant regurgitation. Heart. 2021;107:411–8. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dollar AL, Roberts WC. Morphologic comparison of patients with mitral valve prolapse who died suddenly with patients who died from severe valvular dysfunction or other conditions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:921–31. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90875-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Han Y, Peters DC, Salton CJ et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance characterization of mitral valve prolapse. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lichstein E. Site of origin of ventricular premature beats in patients with mitral valve prolapse. Am Heart J. 1980;100:450–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(80)90656-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Han HC, Parsons SA, Curl CL et al. Systematic quantification of histologic ventricular fibrosis in isolated mitral valve prolapse and sudden cardiac death. Heart Rhythm. 2021;18:570–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hayek E, Gring CN, Griffin BP. Mitral valve prolapse. Lancet. 2005;365:507–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17869-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mantegazza V, Tamborini G, Muratori M et al. Mitral annular disjunction in a large cohort of patients with mitral valve prolapse and significant regurgitation. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:2278–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Franz MR. Mechano-electrical feedback in ventricular myocardium. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32:15–24. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(96)00074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang Z, Taylor LK, Denney WD, Hansen DE. Initiation of ventricular extrasystoles by myocardial stretch in chronically dilated and failing canine left ventricle. Circulation. 1994;90:2022–31. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.4.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Palumbo P, Cannizzaro E, Di Cesare A et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance in arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathies. Radiol Med. 2020;125:1087–101. doi: 10.1007/s11547-020-01289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bui AH, Roujol S, Foppa M et al. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis in patients with mitral valve prolapse and ventricular arrhythmia. Heart. 2017;103:204–9. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sniezek-Maciejewska M, Dubiel JP, Piwowarska W et al. Ventricular arrhythmias and the autonomic tone in patients with mitral valve prolapse. Clin Cardiol. 1992;15:720–4. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960151029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Franz MR, Cima R, Wang D et al. Electrophysiological effects of myocardial stretch and mechanical determinants of stretch-activated arrhythmias. Circulation. 1992;86:968–78. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.3.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tavi P, Han C, Weckström M. Mechanisms of stretch-induced changes in [Ca2+]i in rat atrial myocytes: role of increased troponin C affinity and stretch-activated ion channels. Circ Res. 1998;83:1165–77. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.11.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Perazzolo Marra M, Basso C, De Lazzari M et al. Morphofunctional abnormalities of mitral annulus and arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:e005030. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Olive KE, Grassman ED. Mitral valve prolapse: comparison of diagnosis by physical examination and echocardiography. South Med J. 1990;83:1266–9. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199011000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Devereux RB, Kramer-Fox R, Kligfield P. Mitral valve prolapse: causes, clinical manifestations, and management. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:305–17. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-4-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Savage DD, Devereux RB, Garrison RJ et al. Mitral valve prolapse in the general population. 2. Clinical features: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1983;106:577–81. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(83)90705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Enriquez A, Shirai Y, Huang J et al. Papillary muscle ventricular arrhythmias in patients with arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse: electrophysiologic substrate and catheter ablation outcomes. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2019;30:827–35. doi: 10.1111/jce.13900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Savage DD, Levy D, Garrison RJ et al. Mitral valve prolapse in the general population. 3. Dysrhythmias: the Framingham study. Am Heart J. 1983;106:582–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(83)90706-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barlow JB, Bosman CK. Aneurysmal protrusion of the posterior leaflet of the mitral valve. An auscultatory– electrocardiographic syndrome. Am Heart J. 1966;71:166–78. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(66)90179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bekheit SG, Ali AA, Deglin SM, Jain AC. Analysis of QT interval in patients with idiopathic mitral valve prolapse. Chest. 1982;81:620–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.81.5.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ermakov S, Gulhar R, Lim L et al. Left ventricular mechanical dispersion predicts arrhythmic risk in mitral valve prolapse. Heart. 2019;105:1063–9. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Levy D, Savage D. Prevalence and clinical features of mitral valve prolapse. Am Heart J. 1987;113:1281–90. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90956-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zouridakis EG, Parthenakis FI, Kochiadakis GE et al. QT dispersion in patients with mitral valve prolapse is related to the echocardiographic degree of the prolapse and mitral leaflet thickness. Europace. 2001;3:292–8. doi: 10.1053/eupc.2001.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Franz MR. Mechano-electrical feedback. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;45:263–6. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00390-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lab MJ. Mechanoelectric feedback (transduction) in heart: concepts and implications. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32:3–14. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(96)00088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Criley JM, Zeilenga DW, Morgan MT. Mitral dysfunction: a possible cause of arrhythmias in the prolapsing mitral leaflet syndrome. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1974;85:44–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Algra A, Tijssen JG, Roelandt JR et al. QTc prolongation measured by standard 12-lead electrocardiography is an independent risk factor for sudden death due to cardiac arrest. Circulation. 1991;83:1888–94. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.6.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gornick CC, Tobler HG, Pritzker MC et al. Electrophysiologic effects of papillary muscle traction in the intact heart. Circulation. 1986;73:1013–21. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.73.5.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.O’Neal WT, Singleton MJ, Roberts JD et al. Association between QT-interval components and sudden cardiac death: the ARIC study (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities). Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017;10 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.117.005485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Muthukumar L, Rahman F, Jan MF et al. The Pickelhaube sign: novel echocardiographic risk marker for malignant mitral valve prolapse syndrome. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:1078–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chahal NS, Lim TK, Jain P et al. Normative reference values for the tissue Doppler imaging parameters of left ventricular function: a population-based study. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010;11:51–6. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jep164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Haugaa KH, Smedsrud MK, Steen T et al. Mechanical dispersion assessed by myocardial strain in patients after myocardial infarction for risk prediction of ventricular arrhythmia. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:247–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tayal B, Gorcsan J 3rd, Delgado-Montero A et al. Mechanical dyssynchrony by tissue Doppler cross- correlation is associated with risk for complex ventricular arrhythmias after cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1474–81. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2015.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Spragg DD, Leclercq C, Loghmani M et al. Regional alterations in protein expression in the dyssynchronous failing heart. Circulation. 2003;108:929–32. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000088782.99568.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Groeneveld SA, Kirkels FP, Cramer MJ et al. Prevalence of mitral annulus disjunction and mitral valve prolapse in patients with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e025364. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.025364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Scheirlynck E, Dejgaard LA, Skjølsvik E et al. Increased levels of sST2 in patients with mitral annulus disjunction and ventricular arrhythmias. Open Heart. 2019;6:e001016. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2019-001016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Blomme B, Deroanne C, Hulin A et al. Mechanical strain induces a pro-fibrotic phenotype in human mitral valvular interstitial cells through RhoC/ROCK/MRTF-A and ERK1/2 signaling pathways. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2019;135:149–59. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2019.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zeppenfeld K, Tfelt-Hansen J, de Riva M et al. 2022 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: developed by the task force for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) endorsed by the Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J. 2022;43:3997–4126. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cronin EM, Bogun FM, Maury P et al. 2019 HRS/EHRA/ APHRS/LAHRS expert consensus statement on catheter ablation of ventricular arrhythmias. Europace. 2019;21:1143–4. doi: 10.1093/europace/euz132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lee A, Hamilton-Craig C, Denman R, Haqqani HM. Catheter ablation of papillary muscle arrhythmias: implications of mitral valve prolapse and systolic dysfunction. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;41:750–8. doi: 10.1111/pace.13363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143:e35–71. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:561–632. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Enriquez-Sarano M, Tajik AJ, Schaff HV et al. Echocardiographic prediction of survival after surgical correction of organic mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 1994;90:830–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.2.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]