Abstract

Introduction:

Limited studies exist that describe nonfatal work-related injuries to law enforcement officers (LEOs). The aim of this study is to provide national estimates and trends of nonfatal injuries to LEOs from 2003 through 2014.

Methods:

Nonfatal injuries were obtained from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System - Occupational Supplement (NEISS-Work). Data were obtained for injuries treated in U.S. emergency departments (EDs) from 2003–2014. Nonfatal injury rates were calculated using denominators from the Current Population Survey. Negative binomial regression was used to analyze temporal trends. Data were analyzed in 2016–2017.

Results:

Between 2003 and 2014, an estimated 669,100 LEOs were treated in U.S. EDs for nonfatal injuries. The overall rate of 635 per 10,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) was three times higher than the all other U.S. worker rate (213 per 10,000 FTE). The three leading injury events were assaults & violent acts (35%), bodily reactions & exertion (15%), and transportation incidents (14%). Injury rates were highest for the youngest officers aged 21–24 years. Male and female LEOs had similar nonfatal injury rates. Rates for most injuries remained stable; however, rates for assault-related injuries grew among LEOs between 2003 and 2011.

Conclusions:

NEISS-Work data demonstrate a significant upward trend of nonfatal assaults among U.S. LEOs and this warrants further investigation. Police-citizen interactions are dynamic social encounters and evidence-based policing is vital to the health and safety of both police and civilians. The law enforcement community should energize efforts towards the study of how policing tactics impact both officer and citizen injuries.

Keywords: law enforcement, injury, surveillance

Introduction

Law enforcement officers (LEOs) have had historically high rates of fatal and nonfatal injuries. LEO fatalities are documented in several well-established data systems including the National Law Enforcement Officer Memorial Fund (NLEOMF), the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI’s) Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted (LEOKA) database, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Census of Fatal Occupational Injury (CFOI).1–3 According to 2015 CFOI data, police and sheriffs’ officers had the 18th highest fatality rate behind occupations such as loggers, roofers, and construction laborers.4 While these systems provide a national picture of officer fatalities, much less is known about nonfatal injuries among officers and how these injuries impact officers and their agencies.

A handful of studies on nonfatal LEO injuries have been conducted, but were limited by either size or scope. The FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program collects monthly data on nonfatal assaults of duly sworn university and college, county, state, municipal, and tribal officers who were performing a law enforcement function at the time of the assault.5 However, this program does not track unintentional injuries such as accidental falls or motor vehicle crashes. Also, this program is voluntary and some agencies do not participate.6 These missing data make it difficult to describe national nonfatal injury trends.6 Another effort was the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) Reducing Officer Injuries Final Report which collected self-reported injury data from eighteen law enforcement agencies.7 This report documented nearly 1,300 injuries; 6,000 missed work days; and $2 million in estimated overtime costs in a single year. While the study was a significant undertaking, it used a non-specific injury definition that may have included deaths, simple reports of pain, and off-duty injuries.7 Also, these data may not be generalizable to the law enforcement community as a whole.

Recent events involving LEOs have called attention to a wide range of internal policing issues including use-of-force, discipline of officers, and policing culture. Conversely, these events have also caused law enforcement practitioners, criminologists, and occupational safety and health professionals to consider the impact of police work on the health and safety of officers. The purpose of this article is to extend upon prior work by enumerating and describing nonfatal injuries among on-duty LEOs between 2003 and 2014. To the best of our knowledge, this will be the first study to examine nonfatal injuries among LEOs on a national scale.

Methods

Data Sources

On-duty nonfatal injuries occurring between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2014 to U.S. LEOs were obtained from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System Occupational Injury Supplement (NEISS-Work). The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), in collaboration with the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), collects surveillance data on work-related nonfatal injuries and illnesses treated in U.S. hospitals with a 24 hour emergency department (ED)a The sample of hospitals is a national stratified probability sample of 67 U.S. hospitals divided into strata by hospital size, based on number of annual ED visits.8 An injury is considered work-related if it occurred to a civilian, non-institutionalized worker who was working for pay or other compensation, performing farm-related activities, travelling between locations as part of a job requirement, or volunteering for an organized group. Injuries are identified from ED medical records by trained coders at each participating hospital. To calculate national estimates, each case is assigned a statistical weight based on the inverse probability of selection of the hospital in the sample, and adjustments made for nonresponding hospitals during each calendar year. Injury event characteristics for 2003 through 2011 were coded based on the BLS Occupational Injury and Illness Classification System (OIICS) version 1.01.9–10 Data from 2012 to 2014 were coded using OIICS version 2.01.10 Thus, 2012 is considered a break in series for injury event data. NEISS-Work does not follow a standard coding classification system for the occupation and industry of workers. No review was required by NIOSH’s Institutional Review Board since the analysis was conducted using existing surveillance data.

Case Identification

For this analysis, we defined LEOs as a state or local officer who carried a firearm and had full arrest powers. We excluded law enforcement occupations such as animal control officers, security guards, correctional/detention officers, federal LEOs, parole officers, school safety/resource officers, private investigators, crossing guards, volunteer police, public safety officers serving in a fire capacity, and off-duty officers.

Since NEISS-Work does not include standardized industry and occupation codes, a stepwise process was used to identify LEO cases. We used the inclusion/exclusion criteria noted above to first develop a list of law enforcement key words. These keywords were used to search three variables: ‘business type’, ‘employer name’, and ‘occupation type’. If all three variables included a law enforcement keyword, cases were included without further review. Remaining cases were then manually reviewed if: 1) two of the three variables (‘business type’, ‘employer name’, ‘occupation type’) included a law enforcement key word; 2) ‘occupation type’ included a law enforcement keyword and the other two variables did not include an exclusion term listed above; or 3) ‘occupation type’ was missing and one of the other two variables included a law enforcement keyword. For these remaining cases, the ‘injury incident’ narrative variable was reviewed to determine if the injury could be attributed to police work. We kept cases where the activity was unique to law enforcement such as (1) chasing, running after, or pursuing a suspect; (2) arresting, restraining, or wrestling with a suspect, (3) fighting an assailant/suspect, or (4) participating in police related training. Cases were excluded when the ‘injury incident’ narrative was generic such as ‘fell at work’.

An additional step was taken for remaining cases where the ‘occupation type’ variable was ‘trainee’. Since ‘trainee’ could be interpreted as a cadet (a non-sworn officer) or as a sworn officer participating in physical training or under the supervision of a field training officer, the ‘injury incident’ text was manually reviewed to exclude non-sworn officers from the study. Questionable cases at any stage in this process were reviewed by two additional co-authors to arrive at consensus. After removing officers under the age of 21, the final dataset included 12,270 cases that were identified as LEOs with certainty.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed in 2016–2017 using SAS, version 9.3. Nonfatal, emergency department-treated injury estimates were obtained by summing the statistical weights assigned to each case. Nonfatal injury rates were calculated using denominator data from the BLS’s Current Population Survey (CPS). The CPS is a national household survey, conducted monthly on approximately 60,000 non-institutionalized residents aged 15 years and older.11 Respondents provide information on their occupation, industry, hours of work, and other work-related characteristics.11 The CPS provides information on the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) workers based on the 2002 and 2010 Bureau of Census Occupation (BOC) codes.12 Federal officers and those younger than 21 years of age were removed to match with the numerator data.

Estimated injuries with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using PROC SURVEYMEANS. Nonfatal injury rates were calculated as the estimated number of nonfatal injuries divided by the estimated FTE and expressed as injuries per 10,000 FTE per year. The 95% CIs for rates were calculated by pooling the variances for the NEISS-Work injuries and CPS data. Socio-demographics (sex and age) were compared with rate ratios (RRs) and 95% CIs. Trends over time were analyzed using a negative binomial regression model to correct for overdispersion that occurred when using a Poisson model.

Results

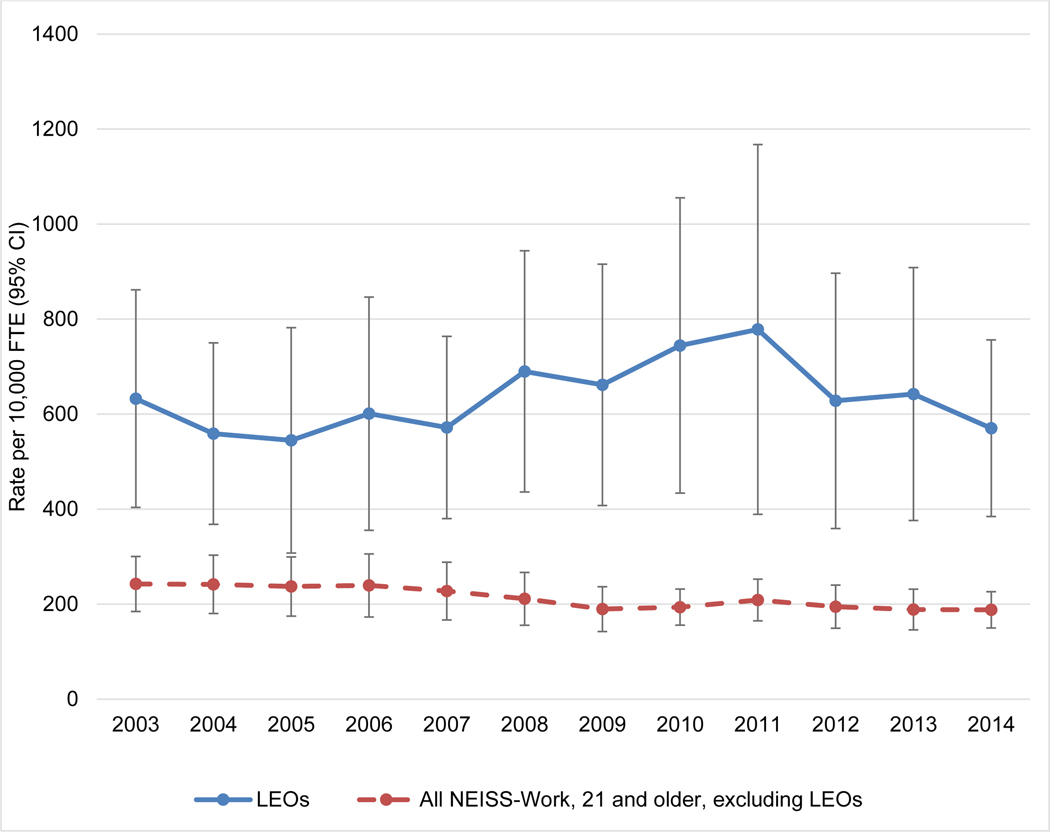

Between 2003 and 2014, the overall nonfatal, emergency department-treated injury rate for LEOs was 635 per 10,000 FTE (95% CI = ±199). The LEO nonfatal injury rate was three times higher than the injury rate of 213 per 10,000 FTE for all other U.S. workers (excluding LEOs). The annual LEO nonfatal injury rate increased from 2007 to 2011 and then decreased until 2014. This resulted in a 1.2 percent (%) annual increase across the 12-year period (p=0.18) (Figure 1). The LEO nonfatal injury trend is in contrast with the injury trend for all other U.S. workers. Between 2003 and 2014, nonfatal injury rates for all other U.S. workers significantly decreased 2.6% annually (p<0.0001).

Figure 1:

Nonfatal Injury Rates per 10,000 FTEs among U.S. LEOs and All Other U.S. Workers: NEISS-Work, 2003–2014

Between 2003 and 2014, an estimated 669,100 (95% CI = ±208,100) officers were treated in EDs for a nonfatal injury (Table 1). While 88% of the injuries occurred to male LEOs, male and female LEOs had relatively similar injury rates (Male=652, Female=535, RR=1.2, 95%CI=0.6–1.8). As age increased, nonfatal injury rates decreased. Officers between 21 and 24 years of age had the highest injury rate (1,230 per 10,000 FTE). Sixty-three percent of nonfatal injuries among LEOs occurred to municipal officers (423,800) and 27% occurred to county level officers (185,600). Most injured LEOs were treated and released from the ED (654,400; 98%).

Table 1.

Number and Rate of Nonfatal Injuries among LEOs by Sex, Age, Disposition, & Agency Type: NEISS-Work, 2003–2014

| Characteristic | Weighted Injury Estimatesa (95% CI) | Percent | Labor Estimate (FTE)c | Rate per 10,000 FTE (95% CI) | Rate Ratio (RR) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 590,400 (±183,700) | 88 | 9,060,500 | 652 (±205) | 1.2 (±0.6) |

| Female | 78,800 (±27,400) | 12 | 1,472,900 | 535 (±211) | 1.0 |

| Age group | |||||

| 21–24 years | 45,300 (±18,000) | 7 | 367,300 | 1,230 (±700) | 7.1 (±5.0) |

| 25–34 years | 301,300 (±98,100) | 45 | 2,941,900 | 1,020 (±358) | 5.9 (±3.2) |

| 35–44 years | 233,700 (±82,300) | 35 | 3,788,800 | 617 (±226) | 3.5 (±1.9) |

| 45–54 years | 71,200 (±21,400) | 11 | 2,426,400 | 293 (±98) | 1.7 (±0.9) |

| 55 years and older | 17,600 (±6,000) | 3 | 1,009,100 | 174 (±72.3) | 1.0 |

| Disposition | |||||

| Treated and released | 654,400 (±206,400) | 98 | 10,533,400 | 620 (±197) | - |

| Treated and admitted | 14,600 (±5,800) | 2 | 10,533,400 | 12.7 (±5) | - |

| Agency Type | |||||

| Municipal | 423,800 (±186,300) | 63 | - | - | - |

| Sheriffb | 185,600 (±148,200) | 27 | - | - | - |

| State | 30,300 (±12,200) | 5 | - | - | - |

| Other | 29,400 (±14,900) | 4 | - | - | - |

| Total | 669,100 (208,100) | 100 | 10,533,400 | 635 (± 199) |

Number may not sum to total due to rounding

Estimate is statistically unreliable with a 40% coefficient of variation

Labor estimates from the Current Population Survey

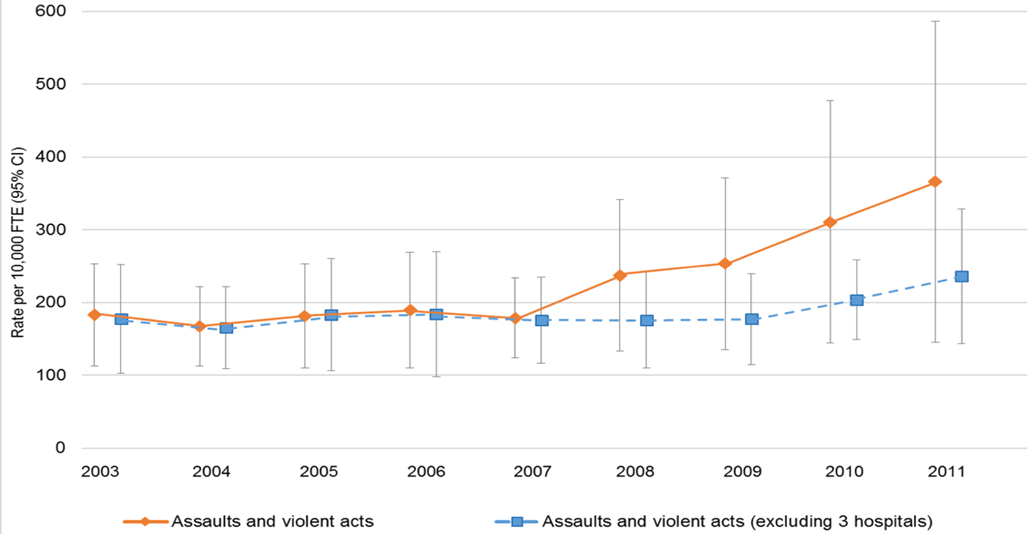

Table 2 describes the body part injured and diagnosis. The two most commonly injured body part categories were hands and fingers (157,600; 24%) and lower extremities (147,100; 22%). The most common injury diagnosis was sprains and strains (199,000; 30%). The three leading nonfatal injury events from 2003 to 2011 were assaults and violent acts (181,100; 95%CI = ± 61,700; 35%), bodily reactions and exertion (74,000, 95%CI = ± 33,900; 15%), and transportation incidents (71,000; 95%CI = ± 24,800; 14%). Nonfatal injury rates for bodily reaction and transportation injuries did not significantly change during the nine-year time period. Rates for assault-related injuries significantly increased 9.6% annually from 2003 to 2011 (p<0.0001) (Figure 2a).

Table 2.

Number and Percentage of Nonfatal Injuries among LEOs by Body Part Injured and Diagnosis: NEISS-Work, 2003–2014

| Body Part Injured | Weighted Injury Estimatesa (95% CI) | Percenta |

|---|---|---|

| Hand & Fingers | 157,600 (±49,100) | 24 |

| Lower Extremities | 147,100 (±43,900) | 22 |

| Trunk and Neck | 108,900 (±35,700) | 16 |

| Head and Face | 90,400 (±33,600) | 14 |

| Upper Extremity | 82,400 (±27,300) | 12 |

| Shoulder | 42,219 (±15,600) | 6 |

| All Other | 29,100 (±11,400) | 4 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Sprain & Strain | 199,000 (±73,100) | 30 |

| All Other | 194,400 (±54,300) | 29 |

| Contusions & Abrasions | 181,200 (±70,700) | 27 |

| Laceration | 50,800 (±14,600) | 8 |

| Fracture & Dislocation | 43,700 (±13,000) | 7 |

| Total | 669,100 (±208,100) | 100 |

Number may not sum to total due to rounding

Figure 2a: Assault Related Injury Rates per 10,000 FTEs among U.S. LEOs: NEISS-Work, 2003–2011.

*Data points for each year are slightly adjusted to the right of the corresponding year to aid visualization

# Assault-related injury trend examined with three hospitals from a single metropolitan area removed.

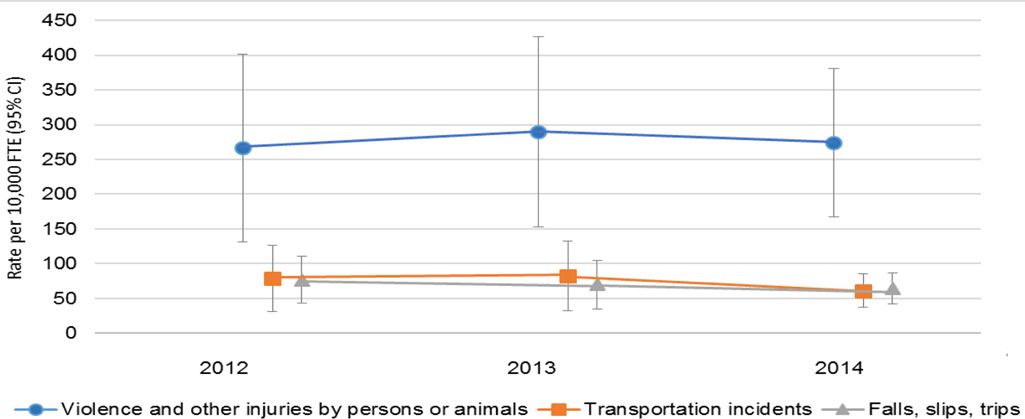

Because data from three hospitals in a single metropolitan area had large increases in assault-related injuries compared to other hospitals, the assault-related injury trend was also examined excluding these hospitals (Figure 2a). This trend analysis was run with adjusted weights due to the removal of three hospitals. This trend also increased significantly 2.9% annually from 2003 to 2011 (p=0.002). Because 2012 represented a break in series for injury event codes, 2012–2014 data were examined separately (Figure 2b). Between 2012 and 2014, the leading nonfatal injury events were violence and other injuries by persons or animals (73,500; 95% CI = ±32,500; 45%); transportation incidents (19,600; 95% CI = ±9,700; 12%); and falls, slips, and trips (18,700; 95% CI = ±6,900; 11%). Injury rates for transportation incidents and falls, slips, and trips decreased significantly during this time period (p=0.04 and p<0.0001, respectively). Comparatively, injury rates due to violence increased 6% annually, though this increase was not statistically significant (p=0.53).

Figure 2b: Nonfatal Injury Rates per 10,000 FTEs among U.S. LEOs for Three Leading Injury Events: NEISS-Work, 2012–2014.

*Data points for each year are slightly adjusted to the right of the corresponding year to aid visualization

Discussion

This research provides a national description of nonfatal, emergency department-treated injuries occurring to U.S. LEOs between 2003 and 2014. Nonfatal injury rates for LEOs remained high compared to all other U.S. workers and these rates increased from 2007 until 2011. This trend was divergent from the trend for all other U.S. workers which significantly decreased from 2003 to 2014. The increase in nonfatal injury rates among LEOs may be driven by the large and significant increase in assault-related injuries that started in 2008 and continued until 2012. Unfortunately, due to the break in injury event coding in 2012, data on the cause of injuries cannot be compared between 2011 and 2012.

This is the first study to demonstrate an upward national trend in assault-related injuries among LEOs. The primary database used to track assaults among LEOs is the FBI’s LEOKA, which is part of the Uniform Crime Report data and has substantial limitations.13 Per a former FBI director, “Because reporting is voluntary, our data is incomplete and therefore, in aggregate, unreliable….”. 14 Yet, studies have used the LEOKA data to describe national patterns and trends and may be reaching erroneous conclusions. For example, Chang et. al. reported the number of police assaulted in the line of duty statistically decreased from 2003 to 2011.15 Using data systems that rely on voluntary reporting could provide misleading results compromising the interpretations concerning police and civilian interactions. The NEISS-Work data may reflect more valid national nonfatal injury rates for LEOs. While the current study improves upon non-reporting and incomplete data biases, it is crucial to consider all possible reasons for increases among assault related injuries. One potential theory is that the increase reflects changing policies across the law enforcement community to better document civilian-officer interactions. For example, one such policy may require officers to visit EDs to document a civilian encounter, regardless of the presence and/or severity of the officer’s injury. A second hypothesis is that the landscape of civilian-officer dynamics is changing.

It is no surprise that assaults are a leading injury event for LEOs. Officers can encounter highly unpredictable and dangerous situations, making it difficult to fully plan prevention strategies and tactics in advance.16 Of the ten risk factors for workplace violence, seven are applicable to the law enforcement profession.17 There is also growing evidence that interactions between police and the public may be changing. The FBI’s Assailant Study interviewed officers and command staff in agencies where an officer had been killed in the line of duty.18 During these interviews, officers expressed concerns over increasing interactions with persons in drug-induced states, an overall justification of violence against police, and a perceived general public distrust in the police.18 Also, a recent Pew Research Center national survey of police officers showed that officers believe police-civilian interactions have become more tense and 93% of police officers are concerned about their safety on the job.19

While the understanding and prevention of fatal shootings of LEOs is imperative, these findings on nonfatal assaults among LEOs identify issues that are equally deserving of further inquiry. Police-citizen interactions are dynamic social encounters where force can occur when an officer seeks to maintain control during resistance.20–21 This resistance can range from passive efforts such as pulling away to direct physical assaults on officers.20–21 The likelihood of injury to officers and citizens depends partially on the level of resistance by the citizen, as well as the force applied by the officer.22 The increase in assault-related injuries reported here may be reflective of an increasing willingness of citizens to resist officers. Conversely, it is possible that officers have become more inclined to use greater force in their encounters with citizens. A complete understanding of the dynamics of police encounters that result in force is critical to effectively reduce assault related injuries to LEOs, as well as associated injuries to citizens.

If violence against LEOs is increasing, many questions remain including how violence impacts the profession of policing in general. Recent data supports the theory that the law enforcement community has begun to engage in “de-policing,” or a reduction in policing duties.23 Seventy-two percent of officers in the Pew study reported they were less willing to stop and question suspicious people, and 76% were reluctant to use force even when it was appropriate to do so.19 Another study of over 100 agencies in a single state found that officers were making significantly fewer vehicle stops and searches in 2015 compared to 2014.23 While available studies have not shown a connection between de-policing strategies and overall crime rates, it is yet to be determined whether de-policing strategies and the severity and frequency of officer injuries are associated.23–24

Limitations

There are limitations to these data. First, NEISS-Work does not use a standardized coding system for occupation or industry; therefore a systematic case-finding methodology was used to identify LEOs. Because this approach erred on sensitivity over specificity, it is possible that some LEOs were missed. Also, the ‘injury incident’ text variable was used to define cases when other employment variables were missing. This may have inflated the number of assault-related cases because cases were included if they involved suspect related activities. Second, LEOs may visit EDs for minor injuries to fully document use-of-force incidents. If so, these results may be overestimates of nonfatal injury rates. On the other hand, because NEISS-Work only collects ED data, it excludes injuries seen in other medical venues; therefore, these results could also underestimate the true rates. Finally, NEISS-Work does not collect standardized information on confounding factors such as work conditions, lifestyle factors, physical or mental co-morbidities, and the use of certain tactics and equipment.

While officer fatalities are fairly well-documented, nonfatal injuries are harder to define, capture, and study from a national perspective. The few efforts to do so have been limited. This study demonstrated that nonfatal injury rates for LEOs remain quite high compared to all other U.S. workers, in spite of a decline in overall worker rates. Additionally, nonfatal injury trends for LEOs increased from 2007 to 2011 and this increase appears to have been driven primarily by assaults. However, we were unable to determine if this significant increase indicates a more dangerous risk environment for officers or other potential reasons such as simply policy changes that required LEOs to visit EDs to document police-civilian encounters. A more thorough analysis is underway to answer these questions. While it may be premature to recommend the implementation of approaches to mitigate assaults occurring to LEOs, it is important to note that studies of how policing tactics impact both officer and civilian injuries are virtually non-existent. Both citizens and LEOs are impacted by violence and evidence-based policing is vital to the health and safety of both.25 A more complete understanding is needed of policing procedures and tactics that are truly evidence-based.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Mention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by NIOSH. In addition, citations to websites external to NIOSH do not constitute endorsement of the sponsoring organizations or their programs or products. Furthermore, NIOSH is not responsible for the content of these websites. All web addresses referenced in this document were accessible as of the publication date.

Footnotes

NIOSH collects NEISS-Work data in collaboration with the CPSC, which operates the base NEISS hospital system for the collection of data on consumer product–related injuries. The CPSC product-related injury estimates exclude work-related injuries, whereas NEISS-Work estimates include all work-related injuries regardless of product involvement (i.e., NEISS and NEISS-Work cases are mutually exclusive).

The authors of this manuscript do not have any conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

Contributor Information

Hope M. Tiesman, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Division of Safety Research, Analysis and Field Evaluations Branch, Morgantown, WV.

Melody Gwilliam, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Division of Safety Research, Analysis and Field Evaluations Branch, Morgantown, WV.

Srinivas Konda, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Division of Safety Research, Analysis and Field Evaluations Branch, Morgantown, WV.

Jeff Rojek, University of Texas at El Paso, Department of Criminal Justice, El Paso, TX.

Suzanne Marsh, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Division of Safety Research, Surveillance and Field Investigations Branch, Morgantown, WV.

References

- 1.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Census of fatal occupational injuries (CFOI) - current and revised data website. https://www.bls.gov/iif/oshcfoi1.htm. Updated March 2, 2017. Accessed March 29 2017.

- 2.U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2015 Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted, 2015. U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Criminal Justice Information Services Division website. https://ucr.fbi.gov/leoka/2015. Accessed March 29 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund. 2016. 2016 Preliminary end-of-year law enforcement officer fatalities report website. http://www.nleomf.org/ytest/facts-figures/fatalities-reports/. Accessed March 29 2017.

- 4.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics . Hours-based fatal injury rates by industry, occupation, and selected demographic characteristics, 2015 website. https://www.bls.gov/iif/oshcfoi1.htm#rates. Updated March 2 2017. Accessed March 29 2017.

- 5.U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2015. 2015 Law enforcement officers killed and assaulted: officer criteria website. https://ucr.fbi.gov/leoka/2015/resource-pages/officer_criteria_−2015. Accessed March 29 2017.

- 6.Kuhns JB, Dolliver D, Bent E, Maguire ER. Understanding firearms assaults against law enforcement officers in the United States. Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. 2016. https://ric-zai-inc.com/Publications/cops-w0797-pub.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Association of Chiefs of Police and United States of America. Reducing officer injuries final report: a summary of data findings and recommendations from a multi-agency injury tracking study. Center for Officer Safety and Wellness and the Bureau of Justice Assistance. http://www.theiacp.org/portals/0/pdfs/IACP_ROI_Final_Report.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed March 29 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marsh SM, Derk SJ, Jackson LL. 2006. Nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses among workers treated in hospital emergency departments—United States, 2003. MMWR. 55:449–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational injury and illness classification manual. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Work-related injury statistics query system. Technical info website. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/wisards/workrisqs/techinfo.aspx Updated April 10 2017. Accessed June 9 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor force statistics from the current population survey website. http://www.bls.gov/cps/home.htm Accessed March 29 2017.

- 12.US Census Bureau. Industry and occupation website. https://www.census.gov/people/io/methodology/ Accessed June 9 2017.

- 13.Banks D, Blanton C, Couzens L, Cribb D. Arrest-Related Deaths Program Assessment: Technical Report. Washington, DC: RTI International; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt MS. FBI director speaks out on race and police bias. New York Times. February 12 2015:A1.

- 15.Chang DC, Williams M, Sangji NF, Britt LD, Rogers SO. Pattern of law enforcement-related injuries in the United States. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80:870–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyons K, Radburn C, Orr R, Pope R. A profile of injuries sustained by law enforcement officers: a critical review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crifasi CK, Pollack KM, Webster DW. Assaults against U.S. law enforcement officer in the line-of-duty: situational context and predictors of lethality. Inj Epidemiol 2016;3(29):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richardson V. FBI report finds officers ‘de-policing’ as anti-cop hostility becomes ‘new norm’ - The Assailant Study-Mindsets and Behaviors. The Washington Times. May 4, 2017. http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2017/may/4/fbi-report-officers-de-policing-anti-cop-hostility/. Accessed June 19, 2017.

- 19.Morin R, Parker K, Stepler R. Mercer A. Behind the badge: Amid protests and calls for reform, how police view their jobs, key issues and recent fatal encounters between blacks and police. Pew Research Center. http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2017/01/06171402/Police-Report_FINAL_web.pdf. Published January 2017. Accessed June 19, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sykes R, Clark J. 1975. A theory of deference exchange in police civilian encounters. Am J Sociol 1975;81(3):584–600. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alpert GP, Dunham RG. Understanding police use of force: Officers, suspects, and reciprocity. New York:NY: Cambridge University Press. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith MR, Kaminski RJ, Rojek J, Alpert GP, Mathis J. The impact of conducted energy devices and other types of force and resistance on officer and suspect injuries. Policing. 2007;30(3):426–446. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shjarback JA, Pyrooz DC, Wolfe SE, Decker SH. De-policing and crime in the wake of Ferguson: Racialized changes in the quantity and quality of policing among Missouri police departments. J Crim Justice. 2017;50:42–52. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan SL, Pally JA (2016). Ferguson, Gray, and Davis: An analysis of recorded crime incidents and arrests in Baltimore City, March 2010 through December 2015. A report written from the 21st Century Cities Initiative at Johns Hopkins University. Available at: http://socweb.soc.jhu.edu/faculty/morgan/papers/MorganPally2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shepard JP, Sumner SA. Policing and public health--Strategies for Collaboration. JAMA. 2017;317(15):1525–1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]