ABSTRACT

Facultative endosymbiotic bacteria, such as Wolbachia and Spiroplasma species, are commonly found in association with insects and can dramatically alter their host physiology. Many endosymbionts are defensive and protect their hosts against parasites or pathogens. Despite the widespread nature of defensive insect symbioses and their importance for the ecology and evolution of insects, the mechanisms of symbiont-mediated host protection remain poorly characterized. Here, we utilized the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster and its facultative endosymbiont Spiroplasma poulsonii to characterize the mechanisms underlying symbiont-mediated host protection against bacterial and fungal pathogens. Our results indicate a variable effect of S. poulsonii on infection outcome, with endosymbiont-harboring flies being more resistant to Rhyzopus oryzae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Providencia alcalifaciens but more sensitive or as sensitive as endosymbiont-free flies to the infections with Pseudomonas species. Further focusing on the protective effect, we identified Transferrin-mediated iron sequestration induced by Spiroplasma as being crucial for the defense against R. oryzae and P. alcalifaciens. In the case of S. aureus, enhanced melanization in Spiroplasma-harboring flies plays a major role in protection. Both iron sequestration and melanization induced by Spiroplasma require the host immune sensor protease Persephone, suggesting a role of proteases secreted by the symbiont in the activation of host defense reactions. Hence, our work reveals a broader defensive range of Spiroplasma than previously appreciated and adds nutritional immunity and melanization to the defensive arsenal of symbionts.

IMPORTANCE

Defensive endosymbiotic bacteria conferring protection to their hosts against parasites and pathogens are widespread in insect populations. However, the mechanisms by which most symbionts confer protection are not fully understood. Here, we studied the mechanisms of protection against bacterial and fungal pathogens mediated by the Drosophila melanogaster endosymbiont Spiroplasma poulsonii. We demonstrate that besides the previously described protection against wasps and nematodes, Spiroplasma also confers increased resistance to pathogenic bacteria and fungi. We identified Spiroplasma-induced iron sequestration and melanization as key defense mechanisms. Our work broadens the known defense spectrum of Spiroplasma and reveals a previously unappreciated role of melanization and iron sequestration in endosymbiont-mediated host protection. We propose that the mechanisms we have identified here may be of broader significance and could apply to other endosymbionts, particularly to Wolbachia, and potentially explain their protective properties.

KEYWORDS: Spiroplasma poulsonii, endosymbionts, Drosophila, immune priming, host defense, pathogens

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial endosymbionts that live inside the host are commonly observed in insects (1). These endosymbionts are vertically transmitted from the mothers to their offspring, often in the egg cytoplasm. Some endosymbionts are obligate as they are essential for host development and survival by providing essential vitamins or amino acids, for example. Other endosymbionts are facultative as they are not necessary for host survival. While obligate endosymbionts reach 100% prevalence in the host insect populations, facultative endosymbionts are usually found at variable prevalence but still remain widespread in insect populations (2–4). This is because facultative endosymbionts likely have established additional approaches to increase their transmission, such as manipulating host reproduction (e.g., male killing, parthenogenesis induction, or cytoplasmic incompatibility) (5). Some facultative endosymbionts also bring ecological advantages to their hosts, such as tolerance to heat (6) or protection against natural enemies (7–9), which also contributes to the maintenance and spread of symbionts in insect populations (10–12). Symbiont-mediated defense has been confirmed in diverse insects, protecting them against a variety of antagonists, like RNA viruses, nematodes, parasitic wasps, and pathogenic fungi (9, 10, 13–19). The fact that taxonomically different symbionts can provide protection against various parasites suggests that the defensive nature of insect-microbe symbiosis is a common, if not predominant, aspect of insect symbioses.

Despite the widespread nature of defensive insect symbioses and their potential use in controlling human diseases that are vectored by insects (1, 14, 20), the mechanisms of symbiont-mediated host protection remain poorly characterized. However, the following mechanisms have been proposed. First, symbionts can improve the overall fitness of their host, for example, by providing vitamins or amino acids, thereby increasing the amount of resources the host can allocate to defense (21, 22). Second, defensive microbes can produce toxins and bioactive compounds that directly target the parasites and pathogens infecting the host. For example, the aphid symbiont Hamiltonella defensa protects the host from parasitoid wasps by toxins produced by a bacteriophage associated with Hamiltonella (23). Similarly, ribosome-inactivating-protein (RIP) toxins produced by the bacterial endosymbiont Spiroplasma are involved in the protection of Drosophila against parasitic nematodes and parasitoid wasps (19, 24, 25). Many of the symbiont-produced toxins affect essential eukaryotic processes; therefore, it is not fully understood how these toxins specifically target parasites and lack toxicity to the insect host (26). Third, microbial symbionts can competitively exclude pathogens and parasites, thereby protecting their host. This is often mediated by competition for a shared and limited resource within a host, thus limiting parasite growth. For example, Wolbachia’s defense against viruses in Drosophila may be due to the competition for cholesterol (27). Additionally, competition for host lipids has been suggested to play a role in the Spiroplasma-mediated protection against parasitoid wasps in Drosophila (28). Finally, symbiotic microorganisms can enhance host resistance against pathogens and parasites by stimulating or priming the host’s immune system (29). This mechanism has been suggested to mediate the host protection by Wolbachia against viruses and certain bacteria (18, 30) and potentially against fungi (17). Some studies indicated that Spiroplasma may also induce immune responses in fruit flies, particularly the Toll pathway (19, 31). However, the significance of this immune upregulation for host defense has not been tested.

In this study, we investigated whether the endosymbiont Spiroplasma protects fruit flies from bacterial and fungal infections and the mechanisms that might play a role in this protection.

Along with Wolbachia, diverse Spiroplasma species are the only facultative inherited endosymbionts naturally infecting Drosophila flies (2, 32). Particularly, Spiroplasma poulsonii MSRO (melanogaster sex ratio organism) has been the focus of recent studies. It is a helical-shaped bacterium without a cell wall that lives in the hemolymph of flies, where it relies on lipids for proliferation (33, 34). S. poulsonii is inherited vertically through transovarial transfer (35) and causes reproductive manipulation (male killing), whereby the sons of S. poulsonii -infected females are selectively killed during development. The secreted toxin SpAID (36, 37), which targets the dosage compensation machinery on the male X chromosome leading to apoptosis, was identified as the major male-killing factor. The genome of S. poulsonii MSRO was sequenced and provided the first insights into the endosymbiotic lifestyle of the bacterium (38). However, since S. poulsonii has been considered not cultivable in vitro and genetically intractable, bacterial determinants involved in host interactions remain mostly unknown. The recent development of a culture medium for Spiroplasma in vitro growth (39) along with the first successful transformation (40) opens the potential for genetic manipulation and functional studies of the symbiont. S. poulsonii is also known to protect Drosophila from nematodes and parasitoid wasps (15, 24, 25). This protection is achieved by metabolic competition with wasps (28) and by producing RIP toxins active against wasps and nematodes (24, 25). Previous studies, however, have not observed any protective effect of S. poulsonii against bacterial or fungal pathogens (41, 42). Yet, considering the limited range of previously tested pathogens, the full defensive potential of Spiroplasma remains to be explored. Moreover, recent findings that Spiroplasma induces several defense reactions in flies, such as the activation of the Toll immune pathway and iron sequestration (31, 43), led us to revise the defensive role of this symbiont.

In this study, we showed variable effects of S. poulsonii on infection outcomes, ranging from protective and neutral to detrimental, depending on the pathogen. Further focusing on the protective effect, we identified that iron sequestration induced by Spiroplasma is crucial for the defense against Rhyzopus oryzae and Providencia alcalifaciens. In the case of Staphylococcus aureus, enhanced melanization in Spiroplasma-harboring flies plays a major role in protection. Both iron sequestration and melanization induced by Spiroplasma require the immune sensor protease Persephone, implying the role of proteases secreted by the symbiont in the activation of defense reactions. Altogether, our work adds immune priming to the previously known defense mechanisms conferred by Spiroplasma.

RESULTS

Spiroplasma poulsonii confers increased resistance against some pathogens

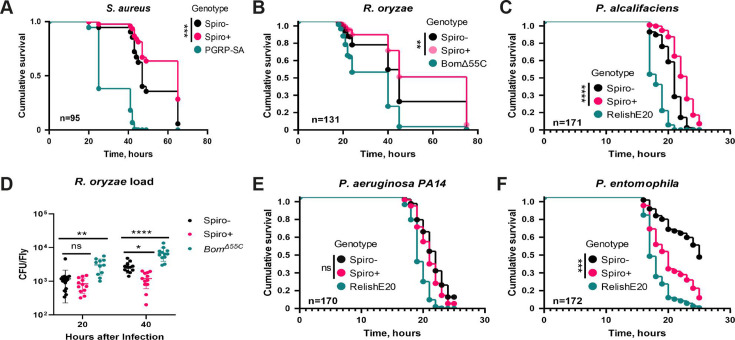

Given the lack of knowledge on the protective effect of Spiroplasma against bacterial and fungal pathogens, we wanted to investigate whether Spiroplasma affects infection outcomes with these pathogens in D. melanogaster. To do this, we used a wild-type (Oregon R) stock harboring the Spiroplasma poulsonii MSRO strain (Spiro+) and Oregon R flies without the symbiont (Spiro−) as a control (42). We infected 10-day-old, mated Spiro+ and Spiro− females with a variety of pathogens and monitored their survival. Spiroplasma-harboring flies survived significantly longer after infections with S. aureus (Fig. 1A), R. oryzae (Fig. 1B), and P. alcalifaciens (Fig. 1C) compared to control flies without Spiroplasma, demonstrating that Spiroplasma provides protection to flies against different groups of pathogens, including Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and fungi. To explore whether this protection is mediated by resistance or tolerance mechanisms, we quantified the within-host burden for R. oryzae and S. aureus. Figure 1D shows that while there was no difference in R. oryzae load between Spiro+ and Spiro− flies at 20 h post-infection, the pathogen load was significantly reduced in Spiro+ flies compared to Spiro− flies at 40 h post-infection. The bomanins-deficient mutant, used as an immunocompromised control with known susceptibility to fungal infections (44), contained the highest R. oryzae burden among the tested flies at both time points after infection (Fig. 1D). Similarly, S. aureus burden was significantly lower in Spiro+ flies compared to Spiro− flies at 20 h post-infection (Fig. S1). These results suggest that Spiro+ are better than Spiro− flies at controlling pathogen growth, consistent with increased resistance rather than tolerance. Infections with the additional pathogens demonstrated that Spiroplasma-harboring flies are not generally more resistant to all pathogens. For example, Spiroplasma had no effect on the susceptibility of the flies to the versatile pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Fig. 1E), and the presence of the endosymbiont was even detrimental in the case of natural fly pathogen Pseudomonas entomophila (Fig. 1F). Overall, these results demonstrate that the effect of Spiroplasma on infection outcome is variable and could be protective, neutral, or detrimental depending on the pathogen.

Fig 1.

Spiroplasma has varied impact on infection outcome. (A–C) Survival rates of Spiroplasma-free (Spiro−) and Spiroplasma-harboring (Spiro+) Oregon R flies after infection with S. aureus (A), R. oryzae (B), and P. alcalifaciens (C). Toll pathway (PGRP-SASeml and Bom∆55C) and Imd pathway (RelishE20) mutants were used as immunocompromised controls. (D) Measurement of R. oryzae burden at 20 and 40 h post-infection in Spiro−, Spiro+, and Bom∆55C flies. For CFU counts, each dot represents CFU from a pool of five animals, calculated per fly. The mean and SD are shown. (E and F) Survival rates of Spiro−, Spiro+, and RelishE20 flies after infection with P. aeruginosa (E) and P. entomophila (F). n = total number of flies in experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; and ns, nonsignificant, P > 0.05.

We decided to further explore the bases of the protective mechanism of Spiroplasma. Specifically, we tested how fly age and mating status, two parameters with a known link to immunity, affect the Spiroplasma-conferred protection against S. aureus. First, we checked the effect of mating status by comparing virgin and mated 10-day-old females. Since Spiroplasma-harboring flies were previously shown to produce more eggs compared to symbiont-free flies (34), we hypothesized that high investment in reproduction of Spiro+ flies could reduce their ability to fight infection, consistent with the reproduction-immunity trade-off hypothesis (45). As expected, virgin flies both Spiro+ and Spiro− were more resistant to S. aureus infection (Fig. S2A). Spiroplasma-harboring flies, both mated and virgin, survived significantly longer compared to control flies without Spiroplasma. However, the protective effect of Spiroplasma in mated flies was not as strong as in virgins as illustrated by the differences in survival curves (Fig. S2A). Hence, mating reduces the protective effect of Spiroplasma.

When we tested the effect of age by comparing the survival of mated flies of different ages, we observed the presence of Spiroplasma-conferred protection in all age groups (3-, 10-, and 20-day old) that we tested (Fig. S2B). While 20-day-old flies were more susceptible to infection compared to young flies independently of endosymbiont presence, Spiroplasma still conferred protection to old flies, albeit to a lesser extent compared to young flies (Fig. S2B). Next, we estimated the effect of age and mating on Spiroplasma abundance which could affect the degree of protection. Spiroplasma load increased with fly age, and virgin flies harbored significantly lower symbiont quantities compared to mated flies of the same age (Fig. S2C). Despite lower Spiroplasma load, virgin flies survived significantly longer after S. aureus infection compared to mated flies. Also, while 10-day-old flies had significantly more Spiroplasma compared to 3-day-old flies, there was no significant difference between the two groups in the survival after S. aureus infection. Likewise, while 20-day-old flies had the highest Spiroplasma load, they were the most susceptible to S. aureus infection. Overall, these results indicate that the degree of protection does not correlate with Spiroplasma abundance. To avoid detrimental effects of aging in old flies and immaturity of young flies, we used mated 10-day-old flies for all subsequent experiments.

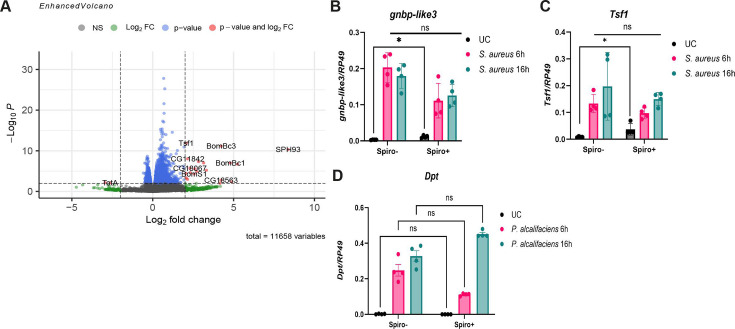

Spiroplasma induces a basal level of Toll pathway activation

To gain more insights into the mechanisms underlying the Spiroplasma-mediated protection against pathogens, we compared differences in gene expression between 10-day-old uninfected Spiro+ and Spiro− females using RNA sequencing. We identified 22 genes with statistically significant differences in expression between Spiro+ and Spiro− flies (Fig. 2A; Table S1). Among these 22 genes, 20 were expressed at a higher level and 2 were repressed in Spiroplasma-harboring flies. Among induced transcripts, we noticed multiple genes linked to the Toll pathway, including serine proteases (SPH93 and CG33462), gnbp-like 3, and several effectors of the Toll pathway (Bomanins, Daishos, and Bombardier) (Fig. 2A; Table S1), suggesting that Spiroplasma induces an immune response and specifically the Toll pathway in flies. In agreement with this, gene ontology (GO) analysis of the genes upregulated in Spiro+ flies showed enrichment of GO terms related to the defense response and the humoral immune response (Fig. S3). Similarly, serine-type endopeptidase molecular function (Fig. S3) was another identified GO term with a link to the Toll pathway due to the known role of serine proteases in the regulation of the Toll pathway. Transferrin 1 (tsf1), an iron transporter with an important immune role (46, 47), was also upregulated in Spiro+ flies (Fig. 2A). Next, we tested whether infection-induced Toll pathway activation in Spiro+ flies is also stronger similarly to the basal uninfected condition. Using RT-qPCR, we confirmed a higher expression of two Toll pathway-controlled genes, gnbp-like3 and tsf1, in uninfected Spiro+ compared to Spiro− flies (Fig. 2B and C). Both genes were potently induced 6 and 16 h after infection with S. aureus with no significant difference between Spiro+ and Spiro− flies. These results illustrate that Spiroplasma elicits mild (as compared to infection) Toll pathway activation under basal conditions and has no effect on the infection-induced level of Toll pathway activity. Importantly, Imd pathway activation, as measured by dpt expression, both at basal level and after infection with P. alcalifaciens was not affected by Spiroplasma (Fig. 2D), suggesting that the increased resistance of Spiro+ flies to infections is not due to increased Imd pathway activity.

Fig 2.

Spiroplasma induces mild Toll pathway activation. (A) Enhanced volcano plot of differentially expressed genes. The log2 fold change indicates the differential expression of genes in the Spiroplasma-harboring (Spiro+) versus Spiroplasma-free (Spiro−) samples. Red dots indicate significance as defined by an absolute fold change value over 2 or under −2 and a P-value below 0.05. (B–D) RT-qPCR showing gnbp-like3 (B) and tsf1 (C) expression in uninfected (UC) and S. aureus-infected Spiro− and Spiro+ flies. (D) Diptericin A expression in uninfected and P. alcalifaciens-infected Spiro– and Spiro+ flies measured by RT-qPCR. The mean and SD of four independent experiments are shown.

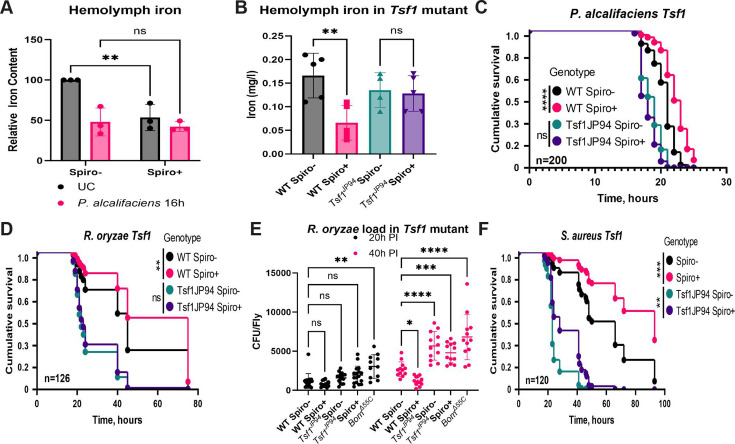

Spiroplasma-induced iron sequestration via Tsf1 contributes to the protective effect

Given a previously described role of Tsf1-mediated iron sequestration in the Drosophila defense against pathogens (46), we hypothesized that increased tsf1 expression and iron sequestration in Spiro+ flies might be part of the defense mechanism provided by Spiroplasma. To test this hypothesis, we first compared the iron sequestration ability in Spiro− and Spiro+ flies by measuring iron levels in the hemolymph using a ferrozine assay. Consistent with a previous report (43), we observed significantly lower iron levels in the hemolymph of Spiroplasma-harboring flies relative to symbiont-free controls under basal conditions (without infection) (Fig. 3A). We confirmed this result with an additional method—inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES). Importantly, while P. alcalifaciens infection triggered a significant drop in the hemolymph iron levels in Spiro− flies compared to uninfected controls, there was no further decrease in the amount of iron after infection in Spiro+ flies (Fig. 3A). We observed a similar result with a non-lethal pathogen Ecc15 and with P. entomophila, a pathogen against which Spiroplasma does not provide protection (Fig. S4). These results demonstrate that Spiroplasma induces iron sequestration from the hemolymph already under basal conditions. This hypoferremic response is comparable to the one induced by pathogens but is not further enhanced by the pathogens, suggesting that Spiroplasma and pathogens trigger iron sequestration via the same mechanism. To confirm that this mechanism involves Tsf1, we measured iron in the hemolymph of Tsf1-deficient flies colonized or not with Spiroplasma. Indeed, in contrast to wild-type flies, Tsf1 mutants harboring Spiroplasma contained the same quantity of iron in the hemolymph as the mutant without the symbiont, indicating that Spiroplasma-induced sequestration is dependent on Tsf1 (Fig. 3B). Next, we investigated whether Tsf1 is also required for Spiroplasma-mediated protection against pathogens. As expected from previous studies (46, 48), Tsf1 mutant flies were more susceptible to pathogens and had a higher pathogen load (Fig. 3C through E). While wild-type Spiro+ flies survived significantly longer compared to Spiro− flies after infections with P. alcalifaciens (Fig. 3C) and R. oryzae (Fig. 3D), we did not detect any significant effect of Spiroplasma on the survival of Tsf1 mutants after infections with these pathogens. Consistent with survival, the R. oryzae burden was significantly higher in Tsf1 mutants compared to wild-type flies 40 h post-infection, and Spiroplasma presence had no effect on the pathogen load in the Tsf1 mutant in contrast to the inhibitory effect observed in wild-type flies (Fig. 3E). Hence, functional Tsf1 is required for Spiroplasma to increase the resistance of flies to pathogens. Interestingly, when we tested the role of Tsf1 in Spiroplasma-mediated protection against S. aureus, we observed that the protective effect in the Tsf1 mutant was still present (Fig. 3F) since the Spiroplasma-harboring Tsf1 mutant survived longer after infection compared to the Spiro− Tsf1 mutant, although the degree of protection was not as strong as in wild-type flies. This result suggests that while Tsf1 is partially required for Spiroplasma-mediated protection against S. aureus, it is likely that there are additional mechanisms involved.

Fig 3.

Spiroplasma-induced iron sequestration increases Drosophila resistance to infection. (A) Iron content of hemolymph in Spiro− and Spiro+ uninfected flies and 16 h after P. alcalifaciens infection measured by the ferrozine assay. Iron content in uninfected Spiro− flies was set to 100 and all other values were expressed as a percentage of this value. The mean and SD of three independent experiments are shown. (B) Hemolymph iron content in uninfected Spiroplasma-free (Spiro−) and Spiroplasma-harboring (Spiro+) wild-type (w1118 iso) and Tsf1JP94 iso mutant flies measured by ICP-OES. The mean and SD of four independent experiments are shown. (C and D) Survival rates of Spiroplasma-free (Spiro−) and Spiroplasma-harboring (Spiro+) wild-type (w1118 iso) and Tsf1JP94 iso mutant flies after infection with P. alcalifaciens (C) and R. oryzae (D). (E) Measurement of R. oryzae burden at 20 and 40 h post-infection in Spiroplasma-free (Spiro–) and Spiroplasma-harboring (Spiro+) wild-type (w1118 iso) and Tsf1JP94 iso mutant flies. For CFU counts, each dot represents CFU from a pool of five animals, calculated per fly. The mean and SD are shown. (F) Survival rates of Spiroplasma-free (Spiro−) and Spiroplasma-harboring (Spiro+) wild-type (w1118 iso) and Tsf1JP94 iso mutant flies after infection with S. aureus. n = total number of flies in experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; and ns, nonsignificant, P > 0.05.

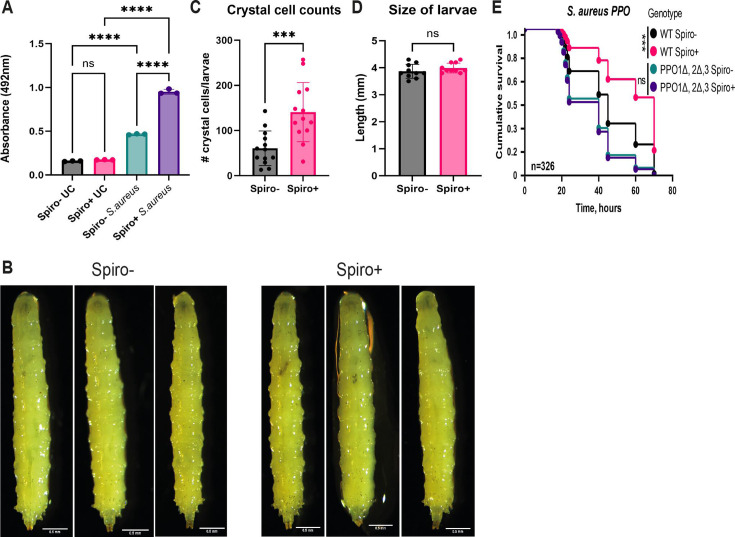

Spiroplasma-induced melanization is required for protection against S. aureus

Next, we attempted to identify the additional mechanisms elicited by Spiroplasma that could contribute to the better survival of endosymbiont-harboring flies after S. aureus infection. Being motivated by a previous study (31) that identified an enrichment of melanization-related proteins in the hemolymph of Spiro+ flies, we decided to test whether Spiroplasma had an effect on the melanization response, which is a key defense reaction against S. aureus (49). We measured enzymatic phenoloxidase (PO) activity with an L-DOPA assay in adult hemolymph samples from wild-type Spiro− and Spiro+ flies. Under unchallenged conditions, these flies did not differ in PO activity, which was very low (Fig. 4A). S. aureus infection increased PO activity as expected. Spiro+ compared to Spiro− flies exhibited significantly higher PO activity after infection (Fig. 4A). This phenotype was not specific to S. aureus as we detected similarly elevated PO activity in Spiro+ flies after infections with P. alcalifaciens and R. oryzae regardless of the time of measurement (Fig. S5A and B). Additionally, we quantified crystal cells that store PPOs using a larva cooking assay. Given that all Spiro+ larvae are females, while the Spiro− population contains both sexes, we selected only female larvae for crystal cell quantification to account for potential sex bias in crystal cell numbers. As apparent from the representative images (Fig. 4B) and quantification analysis (Fig. 4C), Spiro+ larvae contained significantly more crystal cells compared to Spiro− larvae, which might also contribute to the elevated melanization response of Spiro+ animals. Notably, Spiro+ and Spiro− larvae are of a similar length (Fig. 4D), suggesting that the higher number of crystal cells in Spiro+ larvae is not just a consequence of a bigger size. To test whether enhanced melanization constitutes part of the Spiroplasma-mediated protection, we introduced Spiroplasma into the melanization-deficient PPO1∆,2∆,31 mutant and scored its survival after S. aureus infection. As expected, PPO1∆,2∆,31 mutant flies were more susceptible to S. aureus infection compared to wild-type flies (Fig. 4E). However, there was no significant difference in the survival between the Spiro+ and the Spiro− PPO1∆,2∆,31 mutant in contrast to improved survival of wild-type Spiro+ flies (Fig. 4E). These results suggest that a functional melanization reaction is required for Spiroplasma to confer protection against S. aureus.

Fig 4.

Spiroplasma-induced melanization increases Drosophila resistance to S. aureus infection. (A) Hemolymph phenoloxidase activity in uninfected flies and 3 h after S. aureus infection in Spiro− and Spiro+ flies measured by the L-DOPA assay. The mean and SD of three independent experiments are shown. (B) Representative images of Spiro− and Spiro+ Oregon R larvae after heat treatment (cooking assay). Scale bar is 0.5 mm. (C) Crystal cell counts in Spiro− and Spiro+ Oregon R L3 stage larvae after heat treatment (cooking assay). The mean and SD are shown. (D) Length of Spiro− and Spiro+ larvae. (E) Survival rates of Spiroplasma-free (Spiro−) and Spiroplasma-harboring (Spiro+) wild-type (w1118 iso) and PPO1Δ,2Δ,31 iso mutant flies after infection with S. aureus. n = total number of flies in experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; and ns, nonsignificant, P > 0.05.

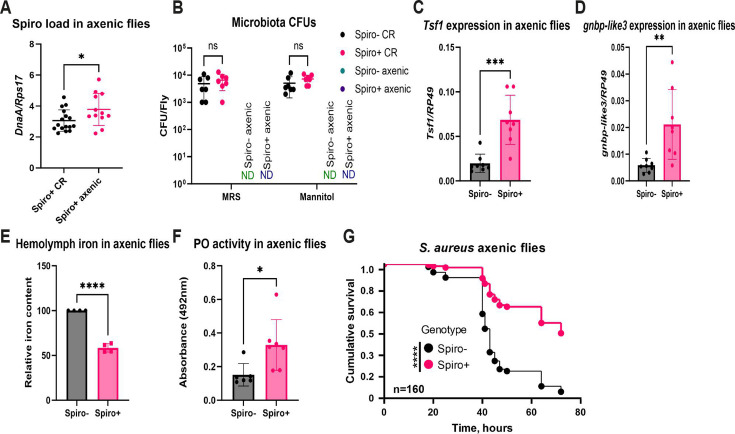

Spiroplasma-mediated protection is independent of microbiota

Considering that symbionts might affect the host physiology by modulating the microbiome (50), we decided to explore whether the phenotypes of Spiro+ flies could be attributed to altered gut microbial communities. For this purpose, we generated axenic Spiro− and Spiro+ flies using a standard egg bleaching protocol, which eliminates surface microbes but preserves endosymbionts. To prove that bleaching did not eliminate Spiroplasma, we quantified endosymbiont load, which was even slightly higher in axenic as compared to conventional flies (Fig. 5A). To confirm germ-free state of our flies, we plated fly homogenates on de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) and mannitol agar—media that support the growth of the majority of Drosophila commensals. We did not recover any bacterial colonies from axenic flies, while conventional flies, independently of Spiroplasma status, harbored up to 104 CFU per fly (Fig. 5B). Thus, Spiroplasma showed no effect on cultivable microbiota load, and we could successfully generate microbiota-free flies colonized with Spiroplasma. Next, we checked whether the phenotypes observed in conventional flies could be reproduced in axenic flies. Spiroplasma induced higher basal activity of the Toll pathway, as measured by tsf1 and gnbp-like 3 expression (Fig. 5C and D) in axenic flies. We also observed a hypoferremic response in axenic flies characterized by significantly lower iron levels in the hemolymph of Spiroplasma-harboring flies relative to symbiont-free controls (Fig. 5E). Elevated PO activity after S. aureus infection was also preserved in Spiro+ flies under axenic conditions (Fig. 5F). Finally, Spiroplasma conferred protection against S. aureus infection (Fig. 5G) under axenic conditions too. These results illustrate that Spiroplasma conferred all the phenotypes under study independently of microbiota, and potential changes in the microbiome caused by the endosymbiont are unlikely to have a major contribution to the protective effect.

Fig 5.

Spiroplasma confers protection independently of microbiota. (A) Quantification of Spiroplasma titer by RT-qPCR in axenic and conventional flies. (B) Quantification of microbiota cultivable on MRS and mannitol agar in conventional (CR) and axenic flies. Each dot represents CFU from a pool of five animals, calculated per fly. ND, not detected. The mean and SD are shown. (C and D) RT-qPCR showing tsf1 (C) and gnbp-like3 (D) expression in axenic Spiro− and Spiro+ flies. (E) Iron content of hemolymph in axenic Spiro− and Spiro+ flies measured by the ferrozine assay. Iron content in Spiro− flies was set to 100, and all other values were expressed as a percentage of this value. The mean and SD of four independent experiments are shown. (F) Hemolymph phenoloxidase activity measured by the L-DOPA assay in axenic Spiro− and Spiro+ flies 3 h after S. aureus infection. The mean and SD are shown. (G) Survival rates of Spiroplasma-free (Spiro−) and Spiroplasma-harboring (Spiro+) axenic flies after infection with S. aureus. n = total number of flies in experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; and ns, nonsignificant, P > 0.05.

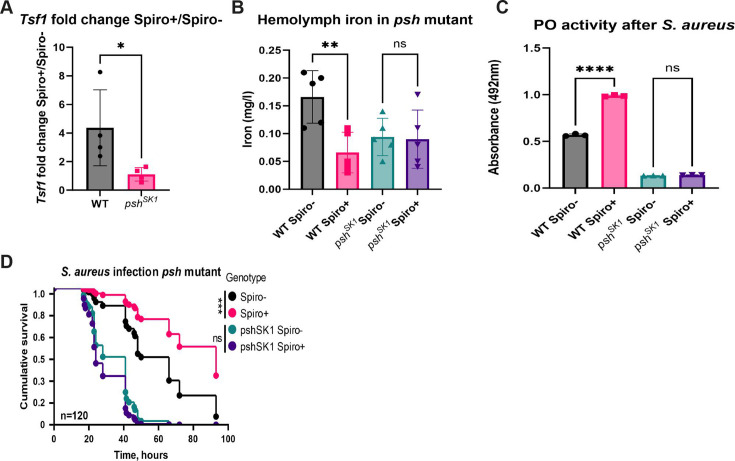

Spiroplasma induces iron sequestration and melanization via Persephone

Finally, we wondered how Spiroplasma induces iron sequestration and melanization. Since both of these processes are linked to the Toll pathway, we hypothesized that their activation is a consequence of mild Toll pathway stimulation by Spiroplasma as supported by our RNA-seq analysis. The Toll pathway can be activated either by peptidoglycan (PGN) sensed by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) or by secreted proteases detected by the sensor serine protease Persephone (51). Since Spiroplasma lacks a cell wall and PGN, detection by PRRs is unlikely. Still, to test the involvement of PRRs in the Toll pathway activation by Spiroplasma, we introduced the symbiont into ModSP mutant, which can sense proteases but is deficient in signal transmission from PRRs to the extracellular signaling cascade upstream of the Toll receptor (52). We found that the expression of the tsf1 gene was induced by Spiroplasma in ModSP mutant as efficiently as in wild-type flies (Fig. S6A). Also, despite increased susceptibility to S. aureus infection as compared to wild-type flies, ModSP mutant-harboring Spiroplasma survived significantly longer compared to symbiont-free control (Fig. S6B). These results indicate that PRRs’ branch of the Toll pathway is not required for Spiroplasma-mediated protection and Toll pathway activation. Hence, we tested the role of protease sensing by Persephone by introducing Spiroplasma into a psh mutant and its wild-type control (yw). First, we measured tsf1 gene expression by RT-qPCR in wild-type and psh mutant flies. While Spiroplasma induced on average a fourfold induction of tsf1 in wild-type flies, in the psh mutant, the fold induction was close to one, indicating similar levels of tsf1 expression in psh mutant flies with and without symbionts (Fig. 6A). Consistent with the lack of inducible tsf1 expression, hemolymph iron levels were not significantly affected by Spiroplasma in psh mutant flies (Fig. 6B). Hence, psh is required for Spiroplasma to induce tsf1 expression and iron sequestration in Drosophila. Similarly, in contrast to wild-type flies that exhibited increased PO activity after S. aureus infection in the presence of Spiroplasma, psh mutants showed only basal PO activity regardless of Spiroplasma status (Fig. 6C). Finally, the increased resistance to S. aureus infection observed in wild-type Spiro+ flies was not detected in psh mutants harboring Spiroplasma (Fig. 6D). Thus, Persephone is necessary for the Spiroplasma-mediated increased resistance to S. aureus.

Fig 6.

Persephone is required for Spiroplasma-induced increased resistance to pathogens. (A) RT-qPCR showing differences in the fold change of tsf1 gene expression induced by Spiroplasma in wild-type and pshSK1 mutant flies. The mean and SD of four independent experiments are shown. (B) Hemolymph iron content in uninfected Spiroplasma-free (Spiro−) and Spiroplasma-harboring (Spiro+) wild-type and pshSK1 mutant flies measured by ICP-OES. The mean and SD of four independent experiments are shown. (C) Hemolymph phenoloxidase activity 3 h after S. aureus infection in Spiroplasma-free (Spiro−) and Spiroplasma-harboring (Spiro+) wild-type and pshSK1 mutant flies measured by the L-DOPA assay. The mean and SD of three independent experiments are shown. (D) Survival rates of Spiroplasma-free (Spiro−) and Spiroplasma-harboring (Spiro+) wild-type and pshSK1 mutant flies after infection with S. aureus. n = total number of flies in experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; and ns, nonsignificant, P > 0.05.

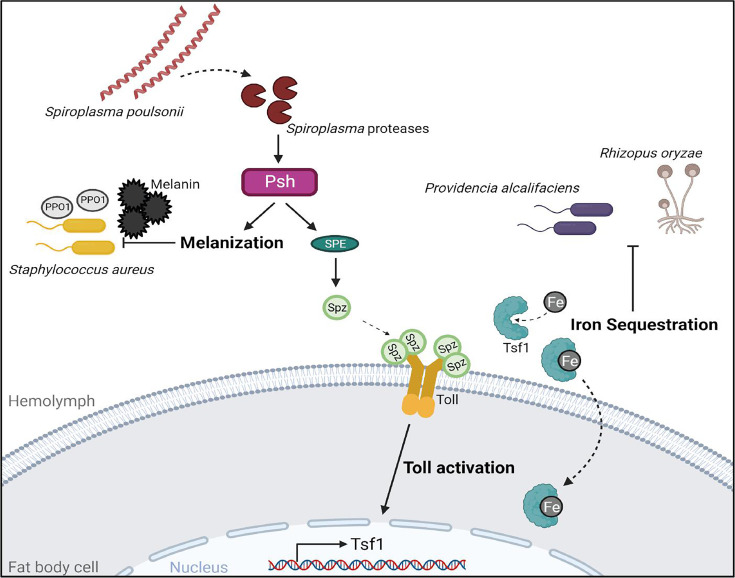

DISCUSSION

The endosymbiont Spiroplasma has been previously shown to protect flies against wasps and nematodes (15, 25). However, Spiroplasma’s defensive properties against other pathogens either have not been studied or were not conclusive, although there are indications that Spiroplasma protects aphids against fungal infections (16). Our work broadens the known defense spectrum of Spiroplasma and reveals a previously unappreciated role of this endosymbiont in increasing Drosophila resistance to bacterial and fungal pathogens. Mechanistically, this increased resistance is realized by Spiroplasma-induced iron sequestration and melanization. Specifically, our results support a model (Fig. 7) where proteases secreted by Spiroplasma are sensed by the circulating immune sensor protease Persephone, leading to the activation of the Toll pathway and the expression of tsf1 among other effectors. Tsf1 in turn executes the iron sequestration reaction by relocating iron from the hemolymph into storage tissues, thus creating hypoferremic conditions unfavorable for pathogen growth. This iron restriction is particularly important in the defense against P. alcalifaciens and R. oryzae and only partially contributes to the defense against S. aureus. Additionally, Spiroplasma-harboring flies exhibit a Persephone-dependent excessive melanization response during infection, which is crucial for increased resistance to S. aureus. Thus, our work adds nutritional immunity and melanization to the defensive arsenal of symbionts. Activation of the Toll pathway by Spiroplasma induces other immune-responsive genes in addition to tsf1, including antimicrobial effectors such as Bomanins, which could also potentially increase the fly’s resistance to fungi and Gram-positive pathogens. However, the expression of Toll pathway effectors induced by Spiroplasma is very low compared to infection and is therefore unlikely to be a major contributor to increased resistance. Iron sequestration on the other hand was very potently induced by Spiroplasma to the same level as that triggered by pathogens. In a way, Spiroplasma-harboring flies have a primed iron sequestration prior to infection. Thus, pathogens invading Spiro+ flies are immediately exposed to iron-restricted conditions, while in Spiro− flies, this hypoferremic response needs time to be initiated, consequently allowing the pathogens to benefit from the iron, proliferate more, and kill the host faster. While Spiroplasma-induced iron sequestration clearly improves the resistance of flies to pathogens, it is not known whether this chronic alteration in iron storage may have detrimental effects in the long term. For example, iron overload is known to cause tissue and organ damage (53). Therefore, we cannot exclude that the increased iron load in storage tissues (fat body) of Spiro+ flies contributes to the reduced lifespan of these flies (43). Chronic hypoferremia observed in the hemolymph of Spiro+ flies might similarly adversely affect the physiology of flies.

Fig 7.

Graphical model illustrating the mechanisms of Spiroplasma-mediated host defense. See Discussion for details.

Previous studies that looked into gene expression changes induced by Spiroplasma in flies reported conflicting results. For example, RT-qPCR did not reveal a significant impact of Spiroplasma on the Imd and Toll pathway activation in flies (42). Studies that used RNA-seq either did not detect any upregulated genes in Spiro+ flies (54) or identified few immune genes, including PPO1 and several serine proteases induced in Spiroplasma-harboring flies (19). While the nature of these discrepancies is not clear, differences in the age of flies used by various studies might be part of the explanation. Consistent with Hamilton et al. (19), our transcriptomic analysis revealed that serine proteases and several Toll pathway-regulated immune genes are induced by Spiroplasma. Importantly, the transcriptional changes that we detected translate into alterations at the protein level, as the corresponding proteins were enriched in the hemolymph of Spiroplasma-harboring flies (31). Thus, our work and the work of Masson et al. (31) challenge the assumption that Spiroplasma is undetectable by the immune system due to the lack of peptidoglycan, a main elicitor of the fly immune response. Instead, our results support a hypothesis that Spiroplasma activates the Toll pathway via the soluble sensor protease Persephone, which detects proteases released by the endosymbiont. The genome of Spiroplasma (38, 55) encodes at least 12 putative proteases, and 4 of them (ATP-dependent zinc metalloprotease FtsH, ATP-dependent Clp protease ATP-binding subunit ClpC, Lon protease 1, and RIP metalloprotease RseP) were detected in the fly hemolymph by proteomic analysis (31). Hence, at least some of the proteases are secreted by Spiroplasma into the hemolymph. Whether and which of these proteases can cleave and activate Persephone remains to be demonstrated.

In addition to iron sequestration induced by Spiroplasma, we observed an increased Persephone-dependent melanization response in endosymbiont-harboring flies. The fact that Spiroplasma could not increase the resistance of melanization-deficient flies to S. aureus infection illustrates the crucial role of the melanization response in the endosymbiont-mediated defense. However, the question of how Spiroplasma enhances the melanization response remains open. Considering the essential function of Persephone in the melanization response, one possibility could be that the activation of Persephone by Spiroplasma-secreted proteases triggers the melanization reaction in addition to the Toll pathway activation. However, in this scenario, we would expect constitutively higher melanization in Spiro+ flies. Our PO activity measurements illustrate that this is not the case, and Spiro+ flies have higher PO activity only after infection. This suggests that proteases secreted by Spiroplasma are either not sufficient to initiate the melanization reaction or that the PPOs are not accessible to proteases in the absence of injury. An alternative possibility could be that the higher number of crystal cells in Spiro+ animals results in higher PO activity. Given that crystal cells store PPOs and release them in the hemolymph only after injury, this would explain why Spiro+ flies have enhanced PO activity only after infection and not constitutively. Since the Toll pathway regulates the expression of many genes involved in melanization (56), it is very likely that basal activity of this pathway in Spiro+ flies is sufficient to promote crystal cell differentiation. Although our results differ from those reported by Paredes et al. (28), who found no effect of Spiroplasma on crystal cell counts after wasp infection, they raise the need for a more detailed investigation of the impact of Spiroplasma on the cellular immune response.

Several prior studies that explored a potential defensive role of Spiroplasma against bacterial pathogens found either no effect of the endosymbiont on infection outcome or an increased susceptibility of Spiro+ flies to certain Gram-negative pathogens (41, 42). Although we used different pathogens, we also had cases with no or negative effects of Spiroplasma on the resistance to pathogens. What determines whether or not Spiroplasma is protective against a specific pathogen remains to be investigated. However, considering that Spiroplasma affects several processes in flies, it is possible that synergistic or antagonistic interactions between these processes and their importance in the defense against a particular pathogen play a decisive role in the infection outcome. For example, we have previously shown that melanization and the Toll pathway do not play a role in the defense against P. alcalifaciens, while iron sequestration is very important (48). Thus, it is very likely that the iron sequestration induced by Spiroplasma is a sole or very prominent defense mechanism. In the case of S. aureus, both melanization and iron sequestration likely contribute, but since the protection was still present in Tsf1 but not in PPO1∆,2∆,31 mutants, this suggests that melanization is more important in the case of S. aureus. However, how these two reactions interact with each other and with the other defense responses, and whether this has consequences for resistance to specific pathogens, remains to be investigated. Given the prominent role of iron sequestration in the defense against Pseudomonas sp. (46), it was surprising to see no increased resistance of Spiro+ flies against P. aeruginosa and P. entomophila. This result suggests that probably Spiroplasma affects additional processes in flies that override the protective effect of iron sequestration. For example, our RNA-seq analysis identified two JAK-STAT pathway-regulated genes, totA and totM, being repressed in Spiro+ flies. This raises the possibility that reduced JAK-STAT pathway signaling in Spiro+ flies might make them more susceptible to P. entomophila infection. Alternatively, reduced hemolymph iron levels in Spiroplasma-harboring flies might reduce the production of reactive oxygen species, which are also important immune effectors. We also cannot exclude the possibility that although melanization is an important defense reaction against S. aureus, it might be detrimental during P. entomophila infection.

Taken together, our study demonstrates a previously unrecognized defensive role of Spiroplasma against bacterial and fungal pathogens and identifies melanization and iron sequestration as endosymbiont-induced immune reactions mediating the protective effect.

Whether other symbionts, like Wolbachia (57), could similarly activate melanization and iron sequestration in insects, and whether these reactions protect insects not only from bacterial pathogens but also from nematodes and wasps, would be an interesting avenue to explore for future studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila stocks and rearing

Spiroplasma poulsonii MSRO Uganda-1 strain was used in all fly stocks harboring Spiroplasma. Oregon R stocks uninfected and infected with S. poulsonii MSRO Uganda-1 were established several years prior to the current study as previously described (42). To establish additional fly stocks infected with Spiroplasma, 9 nL of MSRO-infected hemolymph was injected into the thorax of mated females of the stock to be infected. The progeny of these flies was collected after 5–7 days using male killing as a proxy to assess the infection (100% female progeny). The newly established Spiroplasma-harboring fly stocks were maintained by adding uninfected males of the same genetic background that were maintained in parallel as control stocks. Given that Spiroplasma-infected stocks due to male killing produce only females (around half of the total fly population), this introduces a bias in the rearing density. To correct such bias, we put 1.5 times more Spiroplasma-infected than Spiroplasma-free females per vial, which combined with the higher amount of eggs laid by Spiroplasma-infected females resulted in a comparable rearing density. The following stocks used in this study were kindly provided by Bruno Lemaitre: BomΔ55C; ywDD, PGRP-SASeml, RelishE20 iso; DrosDel w1118 iso; Tsf1JP94 iso; PPO1Δ,2Δ,31 iso; yw; yw pshSK1; ModSP1 (43, 44, 48, 49, 52, 58, 59). Female flies were used in all experiments.

Drosophila stocks were kept at 25°C on a standard cornmeal-agar medium (3.72 g agar, 35.28 g cornmeal, 35.28 g inactivated dried yeast, 16 mL of a 10% solution of methyl-paraben in 85% ethanol, 36 mL fruit juice, and 2.9 mL 99% propionic acid for 600 mL). Flies were flipped to new vials with fresh food every 3–4 days to grow new generations. Axenic flies were generated by egg bleaching as previously described (59) with the exception that antibiotics were omitted from the food. Microbiota-free status of axenic flies and microbiota estimation in conventional flies were performed by plating serial dilutions of fly homogenates on MRS and mannitol agar.

Pathogen strains and survival experiments

The bacterial strains used and their respective optical densities (OD) at 600 nm were Gram-negative bacteria Pectobacterium carotovorum (Ecc15, OD200), P. entomophila (OD1), P. aeruginosa (PA14, OD1), and P. alcalifaciens (OD2); Gram-positive bacteria S. aureus (OD1); and the fungi R. oryzae. Microbes were cultured in Luria broth (LB) at 29°C (Ecc15 and P. entomophila) or 37°C (all others). Spores of the R. oryzae were grown on malt agar plates at 29°C for ∼3 weeks until sporulation.

Systemic infections (septic injury) were performed by pricking adult flies in the thorax with a thin needle previously dipped into the bacterial culture or in a suspension of fungal spores. Infected flies were subsequently maintained at 25°C overnight and changed to 29°C the next morning and surviving flies were counted at regular intervals. Two or three vials of 15–20 flies were used for survival experiments, and survivals were repeated a minimum of two times.

Quantification of pathogen load

Flies were systemically infected with bacteria at the above-indicated OD and allowed to recover. At the indicated time points post-infection, flies were anesthetized using CO2 and surface sterilized by washing them in 70% ethanol. Flies were homogenized using a Precellys Evolution Homogenizer at 7,200 rpm, 1 cycle for 30 s in 500 µL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for sets of five flies. These homogenates were serially diluted and plated on LB agar in 10 µL triplicates. Bacterial plates were incubated at the corresponding bacterial culture temperature overnight, and colony-forming units were counted manually.

For R. oryzae, PBS with 0.01% tween-20 was used instead of PBS. Serial 50 µL dilutions were spread evenly on malt agar plates and left at room temperature overnight.

The equation used to calculate CFU/fly is as follows:

CFU/mL = (no. of colonies × total dilution factor)/volume of culture plated in milliliters

CFU/fly = (CFU/mL) × total volume/total flies

RT-qPCR

For the quantification of messenger RNA, whole flies (n = 10) were collected at indicated time points. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent and dissolved in RNase-free water. A total of 500 ng of total RNA was then reverse transcribed in 10 µL reactions using PrimeScript RT (TAKARA) and random hexamer primers. The qPCR was performed on a LightCycler 480 (Roche) in 96-well plates using the SYBR Select Master Mix from Applied Biosystems. RP49 was used as a housekeeping gene for normalization. Relative expression of target transcripts was calculated following the ∆∆CT method (60). Primer sequences were published previously (31, 46).

Spiroplasma quantification

Spiroplasma quantification was performed by qPCR as previously described (42). Briefly, the DNA was extracted from pools of five whole flies, and the copy number of a single-copy bacterial gene (dnaA) was quantified and normalized by that of the host gene rsp17. Primer sequences were published previously (42).

RNA-seq and GO analysis

Total RNA was extracted from 10 whole flies per sample using TRIzol reagent. Total RNA was dissolved in nuclease-free water, and RNA concentration was measured using a Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific). RNA integrity and quality were estimated using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Separate libraries for the two experimental conditions belonging to three independent experiments were prepared with the TruSeq RNA Sample Prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The DNA was purified between enzymatic reactions, and the size selection of the library was performed with AMPure XT beads (Beckman Coulter Genomics, Danvers, MA, USA). The libraries were pooled and sequenced using Illumina HiSeq 3000 instrument (75 bp paired-end sequencing) at the Max Planck-Genome-Centre Cologne, Germany (https://mpgc.mpipz.mpg.de/home/).

The RNA-seq data from this study (PRJNA1051545) were analyzed using CLG Genomics Workbench (version 12.0 and CLC Genomics Server Version 11.0). The analysis involved employing the “Trim Reads” function (61) and the “RNA-Seq Analysis” tool. Mapping and read counting were performed using the BDGP6.28 Ensembl genome as the reference.

Differential expression analysis was executed through DESeq2 (62). Gene ontology analysis and GO term enrichment on gene group lists were carried out using FlyMine (63), with a background list comprising 11,659 reproducibly measured genes. The obtained results were filtered using a corrected P-value threshold of <0.05 (Holm-Bonferroni). To visualize the data, the R packages ggplot2, dplyr, org.Dm.eg.db, and EnhancedVolcano were employed.

Hemolymph extraction and colorimetric iron measurement

To extract hemolymph, 100 female flies that were infected for 24 h were anesthetized and placed on a 10 µm filter inside an empty Mobicol spin column (MoBiTec). Glass beads were added on top of the flies, and columns were centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C, 5,000 rpm. The collected hemolymph was used for different assays. To measure iron levels, 5–8 µL of hemolymph was collected in 50 µL of Protease Inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, Catalog #11697498001). Then, each sample was diluted in a 1:10 ratio and measured by the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Iron concentration in each sample was normalized to the total protein amount to standardize sample size differences, whereby 120 µg was used as the sample in each assay. Protein samples (made up to 50 µL) were hydrolyzed with 11 µL of 32% hydrochloric acid under heating conditions (95°C) for 20 min and centrifuged for 10 min at 20°C, 16,000 g. A volume of 18 µL of 75 mM ascorbate was added to 45 µL of supernatant followed by 18 µL of 10 mM ferrozine and 36 µL of ammonium acetate. Absorbance was measured at 562 nm using an Infinite 200 Pro plate reader (Tecan). Quantification was performed using a standard curve generated with serial dilutions of a 10 mM FAC stock dilution.

Iron measurement using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry

Hemolymph extraction was performed as described above. Then, 20 µL of hemolymph per sample was digested with 0.5 mL of 32% ultrapure hydrochloric acid (VWR Chemicals) under heating conditions (60°C) for 2 h; 9.5 mL of nitric acid was added to each sample, and the iron quantification was performed on an ICP-OES iCAP 6300 Duo MFC (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at Humboldt University Berlin.

Crystal cell count

Third instar (L3) larvae were collected in a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube with PBS and placed in a heat block at 67°C for 20 min. Larvae were placed on slides and melanization spots were counted manually under ZEISS Stemi 305 stereomicroscope. Pictures of melanized larvae were captured with a Leica M 210 F microscope, a Leica DMC4500 camera, and the Leica Application Suite.

PO activity

Hemolymph extraction was performed as described above. A volume of 5 µL of hemolymph was diluted in a 1:10 ratio in 45 µL of Protease Inhibitor cocktail. The protein concentration was adjusted after Pierce BCA Assay. Sample volumes were adjusted in 200 µL of 5 mM CaCl2 solution. After the addition of 800 µL L-DOPA solution (20 mM, pH 6.6), the samples were incubated at 29°C for 20–23 h in the dark, and the OD at 492 nm was measured every 20 min. Each experiment was run in technical duplicates and repeated three times.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Data representation and statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism 10 software. Each experiment was repeated independently a minimum of three times (unless otherwise indicated), and error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) of replicate experiments. The survival graphs show cumulative survival. At least two replicate survival experiments were performed for each infection, with 15–20 female flies per vial on standard fly medium without yeast. Survival results were statistically analyzed using the Cox-proportional hazard model. The normal distribution of data was checked using D’Agostino-Pearson test. Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the data in Fig. 1D, 2B through D, 3A, B, E, 4A, and 5B; unpaired t-test was used to analyze the data in Fig. 4C and D, 5A and C through F. Where multiple comparisons were necessary, appropriate Tukey, Dunnett, or Sidak post hoc tests were applied. Other details on statistical analysis can be found in figure legends. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001; and ns, non-significant, P > 0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Bruno Lemaitre for the fly stocks. We thank Dr. Kirsten Weiss (Humboldt University Berlin) for technical help with the ICP-OES analysis of the iron content. We thank the Max Planck-Genome-Centre Cologne (http://mpgc.mpipz.mpg.de/home/) for performing the RNA-seq in this study.

I.I. acknowledges funding from the Max Planck Society and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) grant IA 81/2-1.

Contributor Information

Igor Iatsenko, Email: iatsenko@mpiib-berlin.mpg.de.

Martin Kaltenpoth, Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, Jena, Germany.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All raw RNA sequencing data files are available from the SRA database (accession number PRJNA1051545).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.00936-24.

Fig. S1-S6.

Genes differentially expressed between Spiroplasma-harboring and Spiroplasma-free 10-day-old Oregon R female flies.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kikuchi Y. 2009. Endosymbiotic bacteria in insects: their diversity and culturability. Microbes Environ 24:195–204. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.me09140s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mateos M, Castrezana SJ, Nankivell BJ, Estes AM, Markow TA, Moran NA. 2006. Heritable endosymbionts of Drosophila. Genetics 174:363–376. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.058818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Masson F, Lemaitre B. 2020. Growing ungrowable bacteria: overview and perspectives on insect symbiont culturability. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 84:e00089-20. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00089-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eleftherianos I, Atri J, Accetta J, Castillo JC. 2013. Endosymbiotic bacteria in insects: guardians of the immune system? Front Physiol 4:46. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Engelstädter J, Hurst GDD. 2009. The ecology and evolution of microbes that manipulate host reproduction. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 40:127–149. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Montllor CB, Maxmen A, Purcell AH. 2002. Facultative bacterial endosymbionts benefit pea aphids Acyrthosiphon pisum under heat stress. Ecol Entomol 27:189–195. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2311.2002.00393.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vorburger C, Perlman SJ. 2018. The role of defensive symbionts in host–parasite coevolution. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 93:1747–1764. doi: 10.1111/brv.12417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Flórez LV, Biedermann PHW, Engl T, Kaltenpoth M. 2015. Defensive symbioses of animals with prokaryotic and eukaryotic microorganisms. Nat Prod Rep 32:904–936. doi: 10.1039/c5np00010f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oliver KM, Russell JA, Moran NA, Hunter MS. 2003. Facultative bacterial symbionts in aphids confer resistance to parasitic wasps. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:1803–1807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0335320100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jaenike J, Unckless R, Cockburn SN, Boelio LM, Perlman SJ. 2010. Adaptation via symbiosis: recent spread of a Drosophila defensive symbiont. Science 329:212–215. doi: 10.1126/science.1188235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haine ER. 2008. Symbiont-mediated protection. Proc Biol Sci 275:353–361. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhao D, Zhang Z, Niu H, Guo H. 2023. Pathogens are an important driving force for the rapid spread of symbionts in an insect host. Nat Ecol Evol 7:1667–1681. doi: 10.1038/s41559-023-02160-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Teixeira L, Ferreira A, Ashburner M. 2008. The bacterial symbiont Wolbachia induces resistance to RNA viral infections in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol 6:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jeffery JA, Lu G, Pyke AT, Hedges LM, Rocha BC, Hall-Mendelin S, Day A, Riegler M, Hugo LE, Johnson KN, Kay BH, McGraw EA, van den Hurk AF, Ryan PA, O’Neill SL. 2009. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell 139:1268–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xie J, Tiner B, Vilchez I, Mateos M. 2011. Effect of the Drosophila endosymbiont Spiroplasma on parasitoid wasp development and on the reproductive fitness of wasp-attacked fly survivors. Evol Ecol 53:1065–1079. doi: 10.1007/s10682-010-9453-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Łukasik P, van Asch M, Guo H, Ferrari J, Godfray HCJ. 2013. Unrelated facultative endosymbionts protect aphids against a fungal pathogen. Ecol Lett 16:214–218. doi: 10.1111/ele.12031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Perlmutter JI, Atadurdyyeva A, Schedl ME, Unckless RL. 2023. Wolbachia enhances the survival of Drosophila infected with fungal pathogens. bioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2023.09.30.560320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gupta V, Vasanthakrishnan RB, Siva-Jothy J, Monteith KM, Brown SP, Vale PF. 2017. The route of infection determines Wolbachia antibacterial protection in Drosophila. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 284. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.0809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hamilton PT, Leong JS, Koop BF, Perlman SJ. 2014. Transcriptional responses in a Drosophila defensive symbiosis. Mol Ecol 23:1558–1570. doi: 10.1111/mec.12603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hughes GL, Koga R, Xue P, Fukatsu T, Rasgon JL. 2011. Wolbachia infections are virulent and inhibit the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in Anopheles gambiae. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002043. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kanyile SN, Engl T, Kaltenpoth M. 2022. Nutritional symbionts enhance structural defence against predation and fungal infection in a grain pest beetle. J Exp Biol 225:jeb243593. doi: 10.1242/jeb.243593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cornwallis CK, van ’t Padje A, Ellers J, Klein M, Jackson R, Kiers ET, West SA, Henry LM. 2023. Symbioses shape feeding niches and diversification across insects. Nat Ecol Evol 7:1022–1044. doi: 10.1038/s41559-023-02058-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oliver KM, Degnan PH, Hunter MS, Moran NA. 2009. Bacteriophages encode factors required for protection in a symbiotic mutualism. Science 325:992–994. doi: 10.1126/science.1174463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ballinger MJ, Perlman SJ. 2017. Generality of toxins in defensive symbiosis: ribosome-inactivating proteins and defense against parasitic wasps in Drosophila. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006431. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hamilton PT, Peng F, Boulanger MJ, Perlman SJ. 2016. A ribosome-inactivating protein in a Drosophila defensive symbiont. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:350–355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518648113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garcia-Arraez MG, Masson F, Escobar JCP, Lemaitre B. 2019. Functional analysis of RIP toxins from the Drosophila endosymbiont Spiroplasma poulsonii. BMC Microbiol 19:46. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1410-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Caragata EP, Rancès E, Hedges LM, Gofton AW, Johnson KN, O’Neill SL, McGraw EA. 2013. Dietary cholesterol modulates pathogen blocking by Wolbachia. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003459. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Paredes JC, Herren JK, Schüpfer F, Lemaitre B. 2016. The role of lipid competition for endosymbiont-mediated protection against parasitoid wasps in Drosophila. mBio 7:e01006-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01006-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hoang KL, King KC. 2022. Symbiont-mediated immune priming in animals through an evolutionary lens. Microbiology (Reading) 168:001181. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.001181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kambris Z, Blagborough AM, Pinto SB, Blagrove MSC, Godfray HCJ, Sinden RE, Sinkins SP. 2010. Wolbachia stimulates immune gene expression and inhibits Plasmodium development in Anopheles gambiae. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001143. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Masson F, Rommelaere S, Marra A, Schüpfer F, Lemaitre B. 2021. Dual proteomics of Drosophila melanogaster hemolymph infected with the heritable endosymbiont Spiroplasma poulsonii. PLoS One 16:e0250524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Haselkorn TS, Markow TA, Moran NA. 2009. Multiple introductions of the Spiroplasma bacterial endosymbiont into Drosophila. Mol Ecol 18:1294–1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04085.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ramond E, Maclachlan C, Clerc-Rosset S, Knott GW, Lemaitre B. 2016. Cell division by longitudinal scission in the insect endosymbiont Spiroplasma poulsonii. mBio 7:e00881-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00881-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Herren JK, Paredes JC, Schüpfer F, Arafah K, Bulet P, Lemaitre B. 2014. Insect endosymbiont proliferation is limited by lipid availability. Elife 3:e02964. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Herren JK, Paredes JC, Schüpfer F, Lemaitre B. 2013. Vertical transmission of a Drosophila endosymbiont via cooption of the yolk transport and internalization machinery. mBio 4:e00532-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00532-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Harumoto T, Lemaitre B. 2018. Male-killing toxin in a bacterial symbiont of Drosophila. Nature 557:252–255. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0086-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harumoto T. 2023. Self-stabilization mechanism encoded by a bacterial toxin facilitates reproductive parasitism. Curr Biol 33:4021–4029. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Paredes JC, Herren JK, Schüpfer F, Marin R, Claverol S, Kuo CH, Lemaitre B, Béven L. 2015. Genome sequence of the Drosophila melanogaster male-killing Spiroplasma strain MSRO endosymbiont. mBio 6:e02437-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02437-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Masson F, Calderon Copete S, Schüpfer F, Garcia-Arraez G, Lemaitre B. 2018. In vitro culture of the insect endosymbiont Spiroplasma poulsonii highlights bacterial genes involved in host-symbiont interaction. mBio 9:e00024-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00024-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Masson F, Schüpfer F, Jollivet C, Lemaitre B. 2020. Transformation of the Drosophila sex-manipulative endosymbiont Spiroplasma poulsonii and persisting hurdles for functional genetic studies. Appl Environ Microbiol 86:e00835-20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00835-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shokal U, Yadav S, Atri J, Accetta J, Kenney E, Banks K, Katakam A, Jaenike J, Eleftherianos I. 2016. Effects of co-occurring Wolbachia and Spiroplasma endosymbionts on the Drosophila immune response against insect pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria. BMC Microbiol 16:16. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0634-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Herren JK, Lemaitre B. 2011. Spiroplasma and host immunity: activation of humoral immune responses increases endosymbiont load and susceptibility to certain gram-negative bacterial pathogens in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Microbiol 13:1385–1396. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01627.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Marra A, Masson F, Lemaitre B. 2021. The iron transporter Transferrin 1 mediates homeostasis of the endosymbiotic relationship between Drosophila melanogaster and Spiroplasma poulsonii. Microlife 2:uqab008. doi: 10.1093/femsml/uqab008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Clemmons AW, Lindsay SA, Wasserman SA. 2015. An effector peptide family required for Drosophila toll-mediated immunity. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004876. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schwenke RA, Lazzaro BP, Wolfner MF. 2016. Reproduction–immunity trade-offs in insects. Annu Rev Entomol 61:239–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-010715-023924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Iatsenko I, Marra A, Boquete JP, Peña J, Lemaitre B. 2020. Iron sequestration by transferrin 1 mediates nutritional immunity in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117:7317–7325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1914830117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hrdina A, Iatsenko I. 2022. The roles of metals in insect–microbe interactions and immunity. Curr Opin Insect Sci 49:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2021.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shaka M, Arias-Rojas A, Hrdina A, Frahm D, Iatsenko I. 2022. Lipopolysaccharide -mediated resistance to host antimicrobial peptides and hemocytederived reactive-oxygen species are the major Providencia alcalifaciens virulence factors in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Pathog 18:e1010825. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dudzic JP, Hanson MA, Iatsenko I, Kondo S, Lemaitre B. 2019. More than black or white: melanization and toll share regulatory serine proteases in Drosophila. Cell Rep 27:1050–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Simhadri RK, Fast EM, Guo R, Schultz MJ, Vaisman N, Ortiz L, Bybee J, Slatko BE, Frydman HM. 2017. The gut commensal microbiome of Drosophila melanogaster is modified by the endosymbiont Wolbachia. mSphere 2:e00287-17. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00287-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Issa N, Guillaumot N, Lauret E, Matt N, Schaeffer-Reiss C, Van Dorsselaer A, Reichhart J-M, Veillard F. 2018. The circulating protease persephone is an immune sensor for microbial proteolytic activities upstream of the Drosophila toll pathway. Mol Cell 69:539–550. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.01.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Buchon N, Poidevin M, Kwon H-M, Guillou A, Sottas V, Lee B-L, Lemaitre B. 2009. A single modular serine protease integrates signals from pattern-recognition receptors upstream of the Drosophila toll pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:12442–12447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901924106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Allen KJ, Gurrin LC, Constantine CC, Osborne NJ, Delatycki MB, Nicoll AJ, McLaren CE, Bahlo M, Nisselle AE, Vulpe CD, Anderson GJ, Southey MC, Giles GG, English DR, Hopper JL, Olynyk JK, Powell LW, Gertig DM. 2008. Iron-overload-related disease in HFE hereditary hemochromatosis. N Engl J Med 358:221–230. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Alvear VMH, Mateos M, Cortez D, Tamborindeguy C, Martinez-Romero E. 2021. Differential gene expression in a tripartite interaction: Drosophila, Spiroplasma and parasitic wasps. PeerJ 9:e11020. doi: 10.7717/peerj.11020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gerth M, Martinez-Montoya H, Ramirez P, Masson F, Griffin JS, Aramayo R, Siozios S, Lemaitre B, Mateos M, Hurst GDD. 2021. Rapid molecular evolution of Spiroplasma symbionts of Drosophila. Microb Genom 7:1–15. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. De Gregorio E, Spellman PT, Rubin GM, Lemaitre B. 2001. Genome-wide analysis of the Drosophila immune response by using oligonucleotide microarrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:12590–12595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221458698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kremer N, Voronin D, Charif D, Mavingui P, Mollereau B, Vavre F. 2009. Wolbachia interferes with ferritin expression and iron metabolism in insects. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000630. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Arias-Rojas A, Frahm D, Hurwitz R, Brinkmann V, Iatsenko I. 2023. Resistance to host antimicrobial peptides mediates resilience of gut commensals during infection and aging in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 120:e2305649120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2305649120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Iatsenko I, Boquete J-P, Lemaitre B. 2018. Microbiota-derived lactate activates production of reactive oxygen species by the intestinal NADPH oxidase Nox and shortens Drosophila LifeSpan. Immunity 49:929–942. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pfaffl MW. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Robinson MD, Oshlack A. 2010. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol 11:1–9. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-Seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lyne R, Smith R, Rutherford K, Wakeling M, Varley A, Guillier F, Janssens H, Ji W, Mclaren P, North P, Rana D, Riley T, Sullivan J, Watkins X, Woodbridge M, Lilley K, Russell S, Ashburner M, Mizuguchi K, Micklem G. 2007. FlyMine: an integrated database for Drosophila and Anopheles genomics. Genome Biol 8:1–16. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1-S6.

Genes differentially expressed between Spiroplasma-harboring and Spiroplasma-free 10-day-old Oregon R female flies.

Data Availability Statement

All raw RNA sequencing data files are available from the SRA database (accession number PRJNA1051545).