ABSTRACT

Severe COVID-19 has been associated with coinfections with bacterial and fungal pathogens. Notably, patients with COVID-19 who develop Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia exhibit higher rates of mortality than those infected with either pathogen alone. To understand this clinical scenario, we collected and examined S. aureus blood and respiratory isolates from a hospital in New York City during the early phase of the pandemic from both SARS-CoV-2+ and SARS-CoV-2− patients. Whole genome sequencing of these S. aureus isolates revealed broad phylogenetic diversity in both patient groups, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 coinfection was not associated with a particular S. aureus lineage. Phenotypic characterization of the contemporary collection of S. aureus isolates from SARS-CoV-2+ and SARS-CoV-2− patients revealed no notable differences in several virulence traits examined. However, we noted a trend toward overrepresentation of S. aureus bloodstream strains with low cytotoxicity in the SARS-CoV-2+ group. We observed that patients coinfected with SARS-CoV-2 and S. aureus were more likely to die during the acute phase of infection when the coinfecting S. aureus strain exhibited high or low cytotoxicity. To further investigate the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 and S. aureus infections, we developed a murine coinfection model. These studies revealed that infection with SARS-CoV-2 renders mice susceptible to subsequent superinfection with low cytotoxicity S. aureus. Thus, SARS-CoV-2 infection sensitizes the host to coinfections, including S. aureus isolates with low intrinsic virulence.

IMPORTANCE

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an enormous impact on healthcare across the globe. Patients who were severely infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing COVID-19, sometimes became infected with other pathogens, which is termed coinfection. If the coinfecting pathogen is the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, there is an increased risk of patient death. We collected S. aureus strains that coinfected patients with SARS-CoV-2 to study the disease outcome caused by the interaction of these two important pathogens. We found that both in patients and in mice, coinfection with an S. aureus strain lacking toxicity resulted in more severe disease during the early phase of infection, compared with infection with either pathogen alone. Thus, SARS-CoV-2 infection can directly increase the severity of S. aureus infection.

KEYWORDS: COVID, MRSA, coinfection, agr, SARS-CoV-2

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, and the disease it causes, COVID-19, has resulted in an enormous amount of morbidity and mortality globally since late 2019. The clinical course of many viral infections can be complicated by subsequent bacterial or fungal infections, known as coinfections (or superinfections or secondary infections), which can lead to more severe disease (1, 2). This is also true for SARS-CoV-2 infection, in hospitalized patients. While the incidence of coinfections among critically ill COVID-19 patients is often reported to be around 15%, post-mortem studies suggest that the true incidence may be twice as high (3, 4). These discrepancies can be explained by limitations in the sensitivity of culture-based testing and the lack of adjunctive tests with high specificity, which hampers the ability to comprehensively track coinfections.

Nosocomial coinfections during COVID-19 can occur from many different pathogens. Bacterial pulmonary coinfections are mainly caused by Gram-negative bacteria and are associated with an extended duration of mechanical ventilation (5, 6). Pulmonary fungal coinfections have also been reported, particularly aspergillosis (7, 8). Bloodstream infections are reported for Gram-positive species, predominantly Staphylococcal and Enterococcal, as well as various Gram-negative species, albeit less frequently (9, 10). Bloodstream infections with fungal species have also been reported, notably from Candida auris and Candida albicans (11).

The threat of nosocomial S. aureus coinfection in COVID-19 patients has been recognized (12, 13). When compared with other pathogens, bloodstream coinfection with S. aureus has been shown to be associated with increased mortality (9, 14, 15), suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 may predispose patients to more severe S. aureus infection.

S. aureus pathogenesis is complex—the bacterium employs a multitude of virulence factors that can cripple the immune response and facilitate infection (16, 17). An important class of these virulence factors is the beta-barrel pore-forming cytotoxins, which include α-toxin and the bi-component leukocidins (18, 19). These toxins lyse phagocytes and many other cell types by forming pores in host cell membranes and, as such, are necessary for full virulence in several models of disease.

S. aureus is a notorious culprit of nosocomial infections, often with lethal consequences (20, 21). However, S. aureus isolates from nosocomial infections often exhibit low cytotoxic activity in tissue culture models using human neutrophils (22–24), implying lower production of cytotoxins. Inpatients are thought to be more susceptible to low-cytotoxicity strains because they often have medical devices in place and/or compromised immune systems. Underscoring this, isolates from the highly cytotoxic, community-associated lineage USA300, which have infiltrated hospitals (25–27), have been progressively losing their cytotoxic activity over a span of a few years (28).

To study S. aureus coinfections of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients, we collected S. aureus bloodstream and respiratory isolates from a hospital in New York City during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. The S. aureus isolates were collected from both SARS-CoV-2+ and SARS-CoV-2- patients, and genotypic and phenotypic analyses were performed on all isolates. These studies revealed that clinical isolates from both SARS-CoV-2+ and SARS-CoV-2− patients exhibited broad phylogenetic and phenotypic diversity, with no significant phenotypic differences between the two patient groups. However, when focusing on bloodstream-infecting isolates, we found a trend toward lower cytotoxicity in the isolates recovered from SARS-CoV-2+ patients. To model the patient data and explore the SARS-CoV-2/S. aureus dynamic further, we developed a murine SARS-CoV-2/S. aureus coinfection model. Studies in vivo revealed that infection with SARS-CoV-2 worsens S. aureus disease severity and renders mice more susceptible to subsequent systemic infection by low-virulence S. aureus. Thus, SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to increased susceptibility to S. aureus coinfection, which helps shed light on the epidemiological connection between these two deadly pathogens.

RESULTS

Establishment of a biorepository of S. aureus during the early COVID-19 pandemic

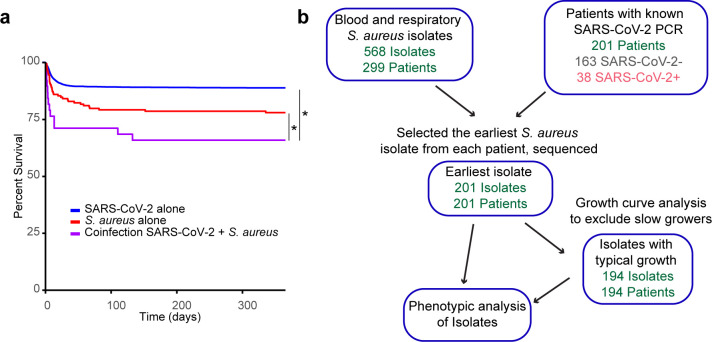

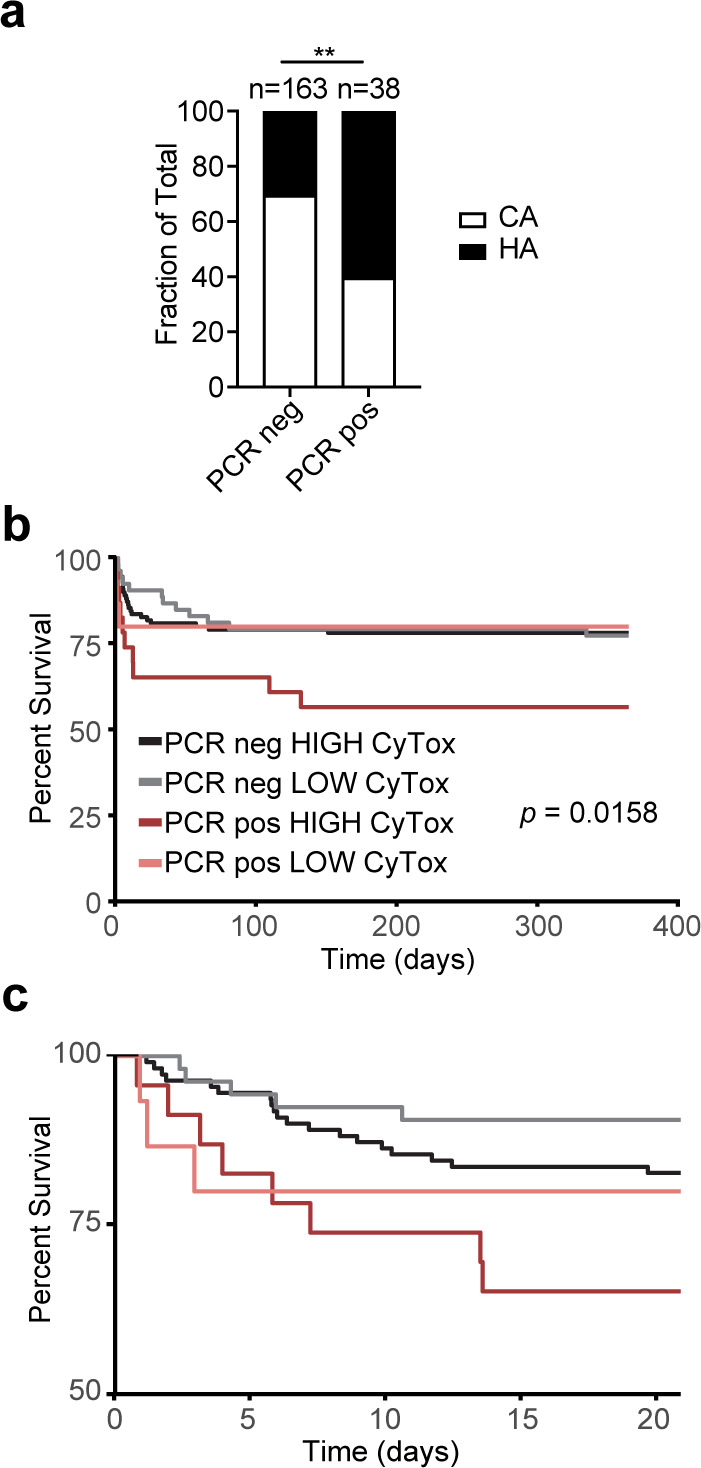

Coinfections can have an impact on patient outcomes in COVID-19, particularly those with S. aureus, which are associated with high mortality. This has been reported (9) and is observed within our cohort analyzed here (Fig. 1a). During the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, we began collecting coinfecting isolates from the NYU Langone Health Tisch Hospital clinical microbiology lab in late March 2020. We collected S. aureus clinical isolates from blood and respiratory cultures of both SARS-CoV-2 PCR+ and PCR− patients, which included isolates from bronchoalveolar lavage and expectorated sputum samples.

Fig 1.

Establishment of a biorepository of S. aureus during the early COVID-19 pandemic (a) Survival curve of patients in our cohort with SARS-CoV-2 confirmed by PCR, with S. aureus blood or respiratory culture or with both infections. Time = 0 on the day of positive S. aureus culture or in the case of SARS-CoV-2 alone, on the day of SARS-CoV-2 PCR positivity. Data were analyzed by Wilcoxon-Breslow test. (b) Generation of the cohort of patients and isolates analyzed in this study. *P < 0.05

We focused on S. aureus isolates from the “first wave” of SARS-CoV-2 infection in New York City, which we defined as ending on August 31st, 2020, based on the subsiding incidence of SARS-CoV-2 in the NYU Langone Health system at that point in time. Bloodstream and respiratory isolates obtained from both sputum and bronchoscopy specimens were included in the analysis. As shown in Fig. 1b, this yielded 568 S. aureus isolates from 299 patients. We confined our in vitro phenotypic analysis to S. aureus isolates that we were able to link to patients with a recent SARS-CoV-2 PCR test and, if there were longitudinal samples, further restricted the analysis to the first S. aureus isolate recovered from each patient. This resulted in 163 patient-isolate pairs from SARS-CoV-2− patients and 38 patient-isolate pairs from SARS-CoV-2+ patients (Fig. 1b).

Patients with SARS-CoV-2 became coinfected with diverse S. aureus strains

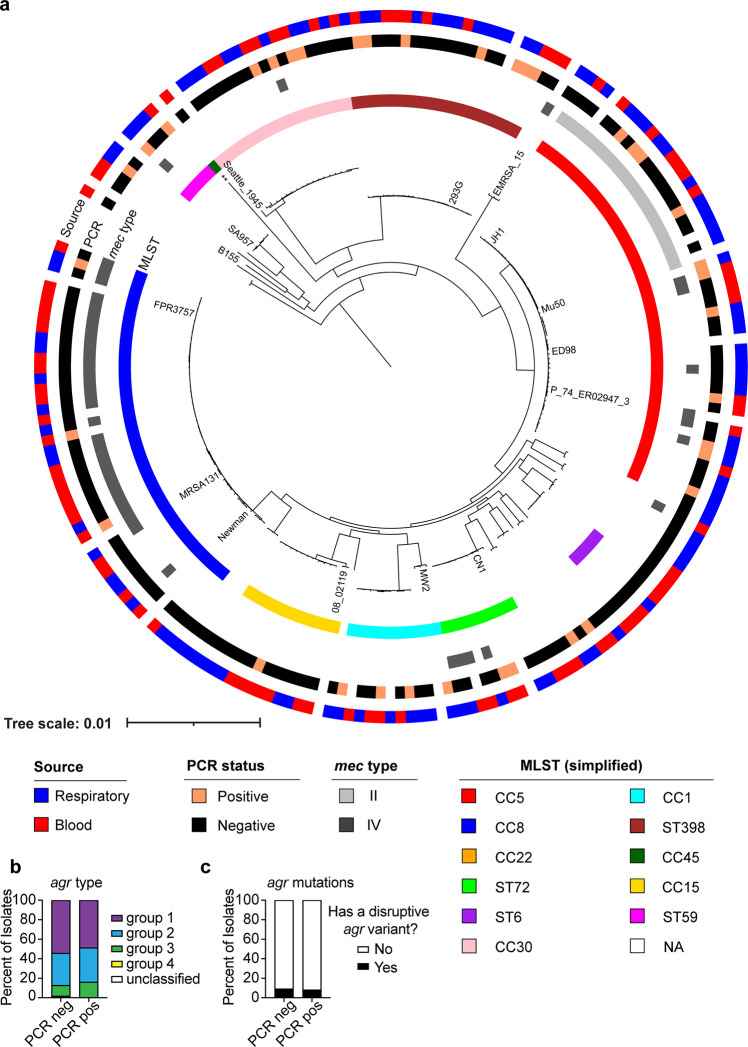

We performed whole-genome sequencing of all the S. aureus strains in our collection and found a wide range of phylogenetic diversity. The data for the constrained analysis on the first S. aureus isolate from each patient with a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 PCR test is depicted in Fig. 2, and the analysis for all the S. aureus isolates in the collection can be found in Fig. S1. The phylogenetic diversity is evident in the isolates from both SARS-CoV-2+ and SARS-CoV-2− patients. Indeed, there were no S. aureus clonal complexes or sequence types that were over-represented in the SARS-CoV-2+ isolate collection relative to the SARS-CoV-2− collection. Both collections had strong representation from the classically healthcare-associated clonal complexes CC5 and CC30, the classically community-associated (but increasingly healthcare-associated) clonal complex CC8, and the classically livestock-associated sequence type ST398 (Fig. 2a). In addition, both blood and respiratory isolates were well-represented throughout the phylogenetic tree for both the SARS-CoV-2+ and the SARS-CoV-2− isolate collections (Fig. 2a). The mec types that were represented for the methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains in this collection were types II and IV, although most isolates were methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA; mec-negative).

Fig 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of S. aureus isolates. (a) The first isolate for each patient in the biorepository is included. Reference strains are labeled. Concentric circles represent CC/ST, mec type (only types II and IV were represented in this collection of isolates; if no mec type is indicated, the strain is mec negative), SARS-CoV-2 PCR result, and isolate source. (b) agr type and (c) agr mutations analyzed by SARS-CoV-2 PCR result. A disruptive agr variant was defined as a frameshift or stop gain. ** = reference strain CA-347. CC = clonal complex, ST = sequence type, “NA” = other or not categorized.

One of the major regulators of virulence in S. aureus is the accessory gene regulator, or Agr, a quorum-sensing system that controls the production of virulence factors, including toxins (29). One or more of the agrBDCA genes are frequently mutated in clinical isolates from the nosocomial setting (30), resulting in lower toxin production and, consequently, lower cytotoxicity to neutrophils and other immune cells (22). As shown in Fig. 2b, several agr types were present in our collection, and the distribution was similar between the SARS-CoV-2+ and SARS-CoV-2− patient isolates. To further analyze the incidence of agr mutations, we counted mutations resulting in frameshifts or premature stop codons as “disruptive” variants. We found that about 10% of the collection harbored disruptive variants in both groups (Fig. 2c). Thus, the overall genetic diversity of the S. aureus isolates is similar between the SARS-CoV-2+ and SARS-CoV-2− isolate collections.

S. aureus strains have comparable growth, hemolysis, and cytotoxicity when isolated from patients with or without SARS-CoV-2 infection

Next, we performed phenotypic characterization of the isolates. We first analyzed their growth in rich medium (Tryptic Soy Broth; TSB) and found that while most of the strains grew at a similar rate to each other, about 3% were deficient in growth, never reaching an OD600 of 1 during overnight culture (Fig. S2a). These isolates were all from SARS-CoV-2− patients. We found that the isolates from patients with or without SARS-CoV-2 infection exhibited comparable maximum growth rate, lag time, and time to reach the stationary phase (Fig. S2b).

The ability to lyse red blood cells is an important virulence trait of S. aureus, since this is the most efficient way for the bacterium to acquire iron during infection (31). Thus, we tested the hemolytic activity of the isolates using blood agar plates. We found a range of alpha and beta hemolysis phenotypes in isolates from both SARS-CoV-2+ and SARS-CoV-2− patients (Fig. S2c). Overall, the hemolytic activity was similar between the two isolate collections, although the percentage of non-hemolytic isolates trended higher with SARS-CoV-2+ isolates compared with SARS-CoV-2− isolates (~35% vs ~20%; Fig. S2c).

S. aureus employs a prototypical yellow pigment to survive oxidative stress (32). Thus, we analyzed the color of the isolates when patched on TSA plates. We found a range of colors, with most isolates displaying a typical light-yellow pigment, whereas some were dark yellow, and some were white. However, there was no noticeable difference in pigment between isolates from SARS-CoV-2+ or SARS-CoV-2− patients (Fig. S2d).

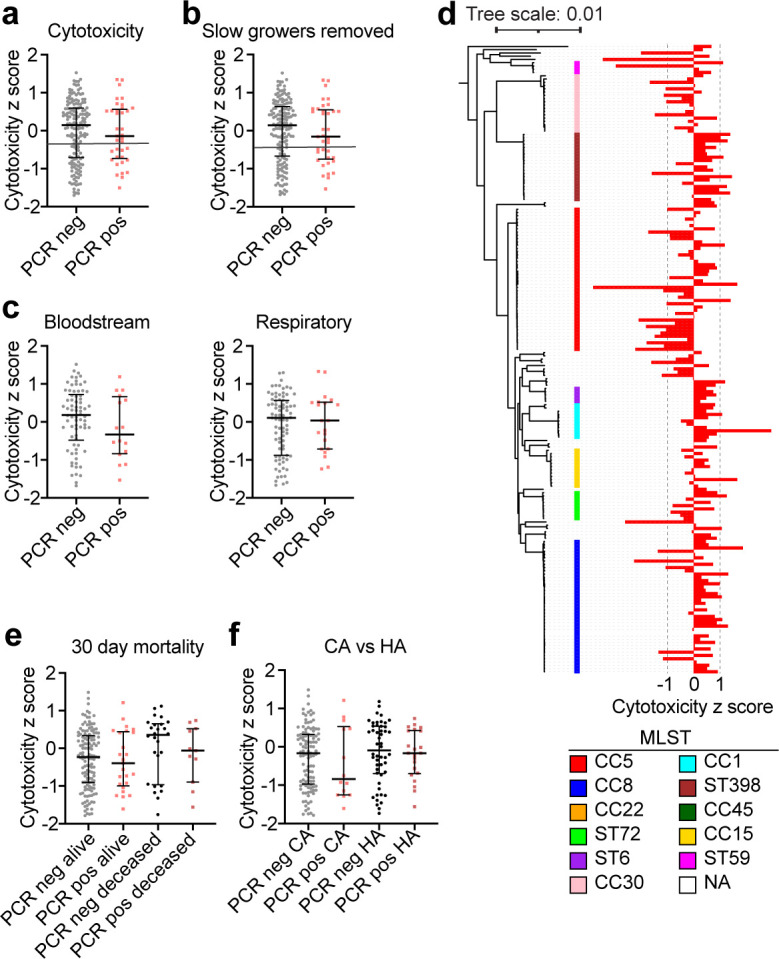

S. aureus is adept at evading the host immune response, and a major virulence strategy that it uses to kill neutrophils and other leukocytes is the secretion of pore-forming leukocidins (19, 33). To evaluate the cytotoxicity of the strains in our collection, we utilized a co-culture assay. In brief, S. aureus was grown overnight to the stationary phase and then used to infect primary human neutrophils for 2 h, after which time cell lysis was measured. Initially, we performed the analysis on all 201 S. aureus isolates in the collection and found that despite the isolates from SARS-CoV-2+ patients trending toward lower cytotoxicity, there was no statistically significant difference in cytotoxicity between isolates from SARS-CoV-2+ and SARS-CoV-2− patients (Fig. 3a). As noted above (Fig. S2a), about 3% of the strains did not reach an OD600 of 1 after overnight culture. Thus, we considered the possibility that these slow-growing strains would not be at a high enough density to produce leukocidins, as these toxins are produced upon quorum sensing (33). As a result, these strains would appear less cytotoxic simply because of their slow growth. To address this possibility, we reanalyzed the data with 194 isolates, having excluded strains that did not reach the cutoff of OD600 = 1 (Fig. 1b). We again found that there was no significant difference between the cytotoxicity of the isolates from SARS-CoV-2+ and SARS-CoV-2− patients (Fig. 3b). We used a Gaussian Mixture Model to define isolates as high or low cytotoxicity. The cutoff that was used based on this model is illustrated as a line in Fig. 3a and b.

Fig 3.

Analysis of cytotoxicity of S. aureus isolates in vitro. (a) Cytotoxicity z-score for each isolate. Cytotoxicity was analyzed by infecting PMNs from human donors and quantifying cell lysis via LDH release. PCR pos are isolates from SARS-CoV-2+ patients, and PCR− are isolates from SARS-CoV-2- patients. (b) As in panel a, but without the isolates that grew slowly and were not able to reach an OD600 of 1 by the end of the overnight growth. The line in a and b indicates the cutoff used to define high and low cytotoxicity strains. (c) Cytotoxicity z-sores separated by the site of isolation. (d) Cytotoxicity visualized across the phylogenetic tree. (e) Cytotoxicity of isolates analyzed by 30-day mortality of the patients. (f) Cytotoxicity of isolates analyzed by community (CA) vs. healthcare (HA) acquisition. Error bars represent median with interquartile range. P > 0.05 for all plots, Mann-Whitney test (a-c), Kurksal-Wallis test (e and f).

To further explore the cytotoxicity data, we compared the isolates from blood cultures with those from respiratory samples. This analysis revealed that overall, both high- and low- cytotoxicity isolates were equally recovered from the blood and respiratory tract (Fig. 3c). We also plotted the cytotoxicity data in the context of phylogeny and found that the CC5 and CC30 strains displayed lower cytotoxicity, whereas the CC8, ST398, and CC1 strains displayed higher cytotoxicity (Fig. 3d), which is consistent with prior reports (23, 34). In addition, we compared the cytotoxicity of isolates from patients who survived at 30 days post-infection versus those who had died and found no significant differences in the cytotoxicity of isolates from these groups (Fig. 3e). Finally, we compared the cytotoxicity of strains acquired in the community with those that were healthcare-acquired (defined as infection after 48 h in the hospital) and found no significant differences in cytotoxicity (Fig. 3f). Overall, we did not find any statistically significant differences in the cytotoxicity of the isolates based on the SARS-CoV-2 status of the patient from whom they were isolated.

Comparing the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients

While we did not find a statistically significant difference in the cytotoxicity of the examined isolates, we nevertheless detected a trend where 50% of isolates from the blood cultures of SARS-CoV-2+ patients exhibited low cytotoxicity, compared with only 35% from SARS-CoV-2− patients (Fig. 3c). These data prompted us to further examine the cytotoxicity data in the context of patient demographics. The characteristics of the patient cohort whose isolates were analyzed here are summarized in Table 1. Since the cytotoxicity of isolates has been shown to correlate with patient outcomes (23), we broke down the cohort by cytotoxicity category—low or high, as well as by SARS-CoV-2 PCR test result. All four patient groups in Table 1 were majority male, consistent with many reports that severe COVID-19 is more common in males (35), but the racial/ethnic spread was similar between groups. For the SARS-CoV-2- patients (PCR neg), about two-thirds of the isolates were community-acquired and one-third were hospital-acquired (Table 1). This was different in the SARS-CoV-2+ group (PCR pos), where the low-cytotoxicity group originated equally from the community and the hospital and the high-cytotoxicity group originated mostly from the hospital (Table 1). Indeed, analyzing the infection origin by SARS-CoV-2 status alone, we observed that the SARS-CoV-2+ patients had more hospital-acquired S. aureus infections than the SARS-CoV-2− patients (Fig. 4a).

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristicsa

| PCR neg high | PCR neg low | PCR pos high | PCR pos low | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CyTox (N = 110) | CyTox (N = 53) | CyTox (N = 23) | CyTox (N = 15) | P value | |

| Sex | 0.986 | ||||

| Female | 36 (32.7%) | 16 (30.2%) | 7 (30.4%) | 5 (33.3%) | |

| Male | 74 (67.3%) | 37 (69.8%) | 16 (69.6%) | 10 (66.7%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.567 | ||||

| Asian | 7 (6.4%) | 3 (5.7%) | 4 (17.4%) | 1 (6.7%) | |

| Black | 14 (12.7%) | 5 (9.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Other/multiracial | 36 (32.7%) | 16 (30.2%) | 9 (39.1%) | 4 (26.7%) | |

| White | 53 (48.2%) | 29 (54.7%) | 10 (43.5%) | 8 (53.3%) | |

| Nosocomial, >48 h | 0.002 | ||||

| Community | 74 (67.3%) | 39 (73.6%) | 7 (30.4%) | 8 (53.3%) | |

| Nosocomial | 36 (32.7%) | 14 (26.4%) | 16 (69.6%) | 7 (46.7%) | |

| Length of stay (days) | 0.122 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 20.56 (47.85) | 13.21 (13.95) | 36.43 (35.79) | 18.60 (16.85) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 10.00 (2.00, 22.00) | 10.00 (2.00, 15.00) | 19.00 (10.00, 57.50) | 11.00 (7.50, 29.00) | |

| Mortality at 7 days | 0.128 | ||||

| Deceased | 13 (11.8%) | 4 (7.5%) | 6 (26.1%) | 3 (20.2%) | |

| Mortality at 30 days | 0.072 | ||||

| Deceased | 21 (19.1%) | 5 (9.4%) | 8 (34.8%) | 3 (20.0%) | |

| Mortality 1 year | 0.159 | ||||

| Deceased | 24 (21.8%) | 12 (22.6%) | 10 (43.5%) | 3 (20.0%) | |

| Source | 0.456 | ||||

| Blood | 54 (49.1%) | 20 (37.7%) | 9 (39.1%) | 8 (53.3%) | |

| Respiratory | 56 (50.9%) | 33 (62.3%) | 14 (60.9%) | 7 (46.7%) | |

| Age, years | 0.319 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 53.51 (25.11) | 57.28 (23.99) | 55.70 (22.84) | 65.33 (17.14) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 60.00 (39.00, 73.00) | 62.00 (46.00, 75.00) | 58.00 (36.50, 72.00) | 70.00 (57.50, 73.00) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 0.325 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.45 (3.34) | 3.72 (3.40) | 2.39 (2.74) | 2.60 (3.33) | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 2.50 (1.00, 5.00) | 3.00 (1.00, 6.00) | 2.00 (0.00, 3.50) | 2.00 (0.00, 3.50) | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Cancer | 27 (24.5%) | 17 (32.1%) | 4 (17.4%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0.357 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 34 (30.9%) | 17 (32.1%) | 6 (26.1%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0.514 |

| Congestive heart failure | 23 (20.9%) | 15 (28.3%) | 1 (4.3%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0.104 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 41 (37.3%) | 31 (58.5%) | 3 (13.0%) | 4 (26.7%) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes no complications | 37 (33.6%) | 21 (39.6%) | 7 (30.4%) | 7 (46.7%) | 0.655 |

| Diabetes with complications | 18 (16.4%) | 12 (22.6%) | 2 (8.7%) | 3 (20.0%) | 0.498 |

| Myocardial infarction | 25 (22.7%) | 13 (24.5%) | 4 (17.4%) | 4 (26.7%) | 0.897 |

| Mild liver disease | 12 (10.9%) | 3 (5.7%) | 5 (21.7%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0.226 |

| Mod/ severe liver disease | 4 (3.6%) | 2 (3.8%) | 3 (13.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.180 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 24 (21.8%) | 13 (24.5%) | 1 (4.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 0.135 |

| Renal disease | 40 (36.4%) | 15 (28.3%) | 3 (13.0%) | 3 (20.0%) | 0.111 |

Patients were divided into four groups: (i) patients with a negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR, with S. aureus isolates that were high cytotoxicity, (ii) patients with a negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR, with S. aureus isolates that were low cytotoxicity, (iii) patients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR, with S. aureus isolates that were high cytotoxicity, and (iv) patients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR, with S. aureus isolates that were low cytotoxicity. CyTox = cytotoxicity. Demographics and clinical characteristics of each group are shown.

Fig 4.

Patient data analysis. (a) Proportions of patients with community-acquired (CA) and healthcare-acquired (HA) S. aureus infection categorized by SARS-CoV-2 PCR result. (b) Survival curve of patients in the four groups described in Table 1. CyTox = cytotoxicity. (c) The same data as in b, focusing on the first 20 days post-S. aureus infection. **P < 0.01, c, Wilcoxon-Breslow test.

The length of hospital stay also trended longer in the SARS-CoV-2+ group (Table 1), consistent with published findings (9), though not statistically significant. Mortality at 30 days and 1 year trended higher in the SARS-CoV-2+ patients coinfected with high cytotoxic strains. Age was similar across the groups, as was the incidence of comorbidities, making these factors unlikely contributors to the observed trend in mortality (Table 1).

We took a deeper look at the mortality in our cohort, which includes both patients with bloodstream and respiratory isolates. We found that patients coinfected by SARS-CoV-2 and highly cytotoxic strains of S. aureus were more likely to die than those in the other three groups (SARS-CoV-2+ with low-cytotoxicity S. aureus, and SARS-CoV-2- with either high- or low-cytotoxicity S. aureus) (Fig. 4b). Interestingly, this cytotoxicity-dependent mortality among coinfected patients reveals itself only after the first week post-S. aureus infection – in the first week, patients coinfected with a low cytotoxicity isolate did not die less than those coinfected with a high cytotoxicity isolate (Fig. 4c; Table 1). One way to interpret these findings is that patient mortality in the first week of SARS-CoV-2 infection was likely driven by the virus and the fact of coinfection, more than by the virulence attributes of the coinfecting S. aureus strain.

SARS-CoV-2 infection sensitizes mice to S. aureus coinfection

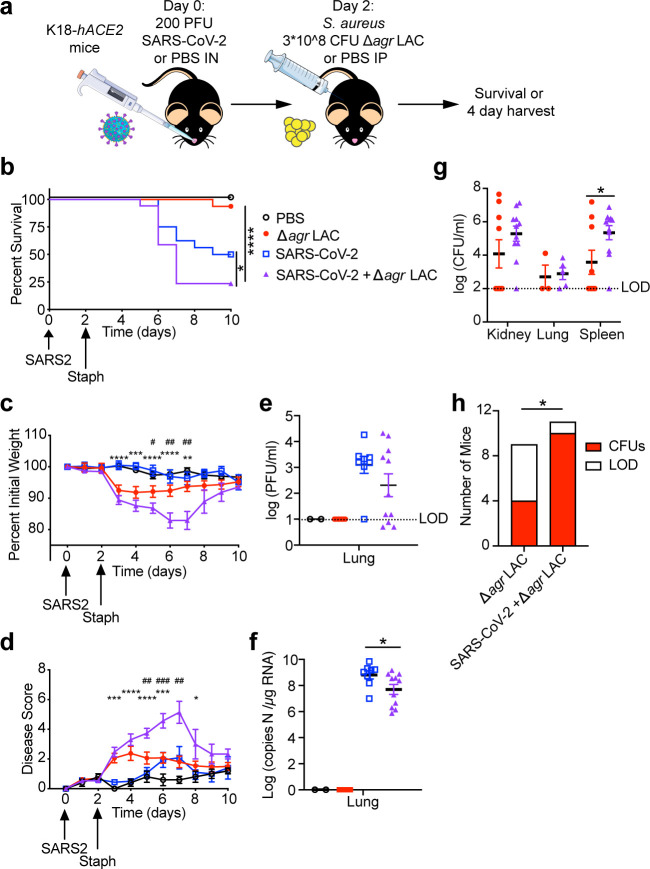

Based on the finding that patients with SARS-CoV-2 and S. aureus coinfections have increased mortality compared to patients with SARS-CoV-2 or S. aureus infection alone (Fig. 1a), we developed a coinfection model in mice to study the dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 and S. aureus in vivo (Fig. 5a). We hypothesized that SARS-CoV-2 infection sensitizes the host to S. aureus and causes what would otherwise be a sublethal infection to become lethal. To test this, we used a Δagr LAC, a USA300 strain of S. aureus (CC8), as agr mutations were observed in our contemporary collection of clinical isolates and agr mutants are associated with nosocomial infections. Moreover, using the Δagr strain facilitated a sublethal infection as Δagr strains produce fewer toxins than WT USA300 and are highly attenuated in mouse models (36). This was necessary to study the impact of SARS-CoV-2/S. aureus coinfection in mice, because it allowed us to develop a model whereby S. aureus on its own was not lethal. We used K18-hACE2 mice as a model, in which the human ACE2 gene is driven by the K18 promoter, rendering the mice susceptible to SARS-CoV-2, including to the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 isolate WA-1 (37), which was the circulating lineage during the time we collected S. aureus isolates.

Fig 5.

SARS-CoV-2 increases susceptibility to S. aureus in mice. (a) Schematic of coinfection experimental design. Survival (b), weight loss (c), and disease score (d) of mice infected with the indicated pathogens (15–17 mice per group, 5 mice in the PBS group). Viral burdens in lungs as determined by plaque assay (e), and qPCR (f) at 4 days post-infection. (g) Bacterial burdens of S. aureus in the indicated organs by CFU at 4 days post-infection. (h) Number of mice that were colonized with S. aureus by 4 days post-infection in any organ (CFUs) or not (LOD) (h). Error bars represent mean +/- SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. b, Mantel-cox test, c, d, Mann-Whitney test, g, Student’s t-test, h, Fisher’s exact test. In panels c and d, * indicates a difference between the SARS-CoV-2 infected group and the coinfected group,and # indicates a difference between the S. aureus infected group and the coinfected group.

The K18-hACE2 mice were infected with a sub-lethal dose of SARS-CoV-2 WA-1 intranasally, and 2 days later, the mice were infected with S. aureus intraperitoneally to model systemic infection (Fig. 5a). In line with our patient data, we found that mice coinfected with S. aureus after SARS-CoV-2 infection exhibited greater morbidity and mortality than mice infected with either SARS-CoV-2 or S. aureus alone (Fig. 5b through d).

We next sought to determine the mechanism for this increased morbidity and mortality. We tested whether coinfection with S. aureus increased viral burden in the lungs but found no increase in either infectious viral particles (measured by plaque-forming units, PFU) or total viral particles (measured by copies of viral RNA) in the coinfected mice. In fact, the opposite trend was observed with less PFU and viral RNA in the lungs of SARS-CoV-2/S. aureus coinfected mice compared with SARS-CoV-2 infection alone (Fig. 5e and f). In contrast, the bacterial burden measured by colony-forming units (CFUs) in coinfected mice was significantly increased in the spleen compared with mice infected with S. aureus alone, and this trend was also observed in the kidneys and lungs of coinfected mice (Fig. 5g). More strikingly, we found that less than half of the mice singly infected with S. aureus had detectable bacterial burden in any of the organs examined 2 days post-S. aureus infection, whereas 90% of the coinfected mice had detectable S. aureus burden at this time point (Fig. 5h). We analyzed the extent of pathology of the lungs by histology and did not find any notable pathology in the sections of lung examined (Fig. S3). We also compared the serum levels of soluble mediators between the groups (Fig. S4). We found that serum cytokine levels were mostly driven by S. aureus infection, without significant differences between the S. aureus-infected and coinfected groups that could explain the survival difference that we observed. In sum, our data established that prior infection with SARS-CoV-2 predisposed mice to infection with low virulence S. aureus, resulting in a more severe bacterial infection and dissemination.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we collected and analyzed S. aureus isolates from SARS-CoV-2+ patients during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in a large metropolitan hospital in New York City. We found broad diversity in the collected isolates, both genetically and phenotypically, which is representative of the molecular epidemiology of S. aureus in the USA. Thus, the acquisition of S. aureus strains among the patients in this cohort did not represent a nosocomial outbreak of a single clone but rather the typical acquisition of S. aureus infections, both in the community and in the hospital.

Our phenotypic analyses did not reveal statistically significant differences between the isolates from SARS-CoV-2+ and SARS-CoV-2− patients. The majority of the isolates displayed high cytotoxicity, with a substantial minority showing low cytotoxicity in our in vitro co-culture system. It should be noted that a major limitation of this study is the imbalance in the number of isolates between the SARS-CoV-2+ and SARS-CoV-2− patient groups—the SARS-CoV-2− isolate collection had about four times the number of isolates of the SARS-CoV-2+ isolate collection. It is possible that a study with an increased number of clinical isolates would have sufficient statistical power to reveal differences between these two groups of isolates. Nevertheless, we observed that more of the bloodstream isolates from SARS-CoV-2+ patients had low cytotoxic and low hemolytic potential in vitro, compared with bloodstream isolates from SARS-CoV-2 negative patients.

We found that patients with SARS-CoV-2 and superinfecting bloodstream or respiratory S. aureus were more likely to die from infection. In the first few days post-infection, patient mortality did not correlate with the cytotoxicity of the infecting S. aureus, but after about a week, the coinfection with high-cytotoxicity S. aureus correlated with a higher risk of mortality. Our murine experiments, which were short-term and conducted with a low-cytotoxicity strain, modeled this initial acute phase of infection, where S. aureus increases patient mortality in a manner that seems to be independent of cytotoxic activity. An interesting direction for future work could be to model longer-term infections with cytotoxic strains. In practice, this would be difficult though, since mice are highly susceptible to cytotoxic strains of S. aureus and typically succumb to infection within the first week. Another important direction for future work is to study coinfection using clinical S. aureus isolates, especially those from SARS-CoV-2+ patients. It would be illuminating to compare naturally occurring low-cytotoxicity isolates with the agr mutant in this experimental system.

There are several possible explanations as to why SARS-CoV-2 predisposes patients to coinfections in general and in particular to severe infections with S. aureus. One possibility is that there is a direct interaction between the virus (and/or the immune response or microbiome disruption caused by the virus) and the coinfecting microbe. There are many potential mechanisms for this. For example, an S. aureus iron-binding protein has been shown to increase SARS-CoV-2 replication by modulating host transcription (38). SARS-CoV-2 infection also can impact the microbiome, promoting gut barrier disruption and translocation of microbes from the gut to the bloodstream (39). Thus, prior SARS-CoV-2 infection could overwhelm the immune system and render the host susceptible to superinfections.

A second possibility is that the treatments given to patients promote coinfection. Indeed, COVID-19 patients are often given corticosteroids, which dampen the immune system, and antibiotics, which promote the growth of fungi and resistant bacteria at mucosal sites (40, 41). Furthermore, early on during the COVID-19 pandemic, IL-6 inhibition was used as an investigational treatment (42), which disrupts the intestinal barrier (43), and has been associated with a higher incidence of coinfections in COVID-19 patients (44). This cocktail of treatments is the perfect recipe to promote bloodstream coinfections.

A third possibility is that the hospital environment during the pandemic promoted coinfections. Patients in hospitals are more frequently malnourished and dehydrated (45, 46), which impacts the immune response (47). It is possible that patients in respiratory isolation may be even more impacted by these factors.

Our in vivo mouse data support, at least partially, the first possibility—that the virus itself, or the host response to it, can directly increase COVID-19 patients’ susceptibility to systemic S. aureus infection. Whether the effect is caused directly by the virus or by the host immune system or microbiome is an important question for future studies. A recent study of pulmonary co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and Streptococcus pneumoniae revealed not only higher bacterial and viral burdens in the coinfected group but also higher inflammatory mediators (48). In our model, we did not measure notable changes in the serum cytokine/chemokine levels (Fig. S4). Important goals for future studies of SARS-CoV-2/S. aureus coinfection should include an in-depth tissue-specific analysis of the inflammatory state during coinfection, including transcriptional analysis and cytokine levels in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Of course, it is likely that a combination of factors promotes S. aureus infection in SARS-CoV-2+ patients. Treatments that COVID-19 patients received, and the hospital environment, could have additive effects upon those driven by the viral infection. Future studies are needed to investigate the combined effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection and antibiotic or steroid treatment or models of poor nutrition and hydration on coinfection with S. aureus.

Virus-S. aureus interactions are much older than the COVID-19 pandemic. Multiple respiratory viruses, including influenza and RSV, predispose patients to S. aureus and other bacterial co-infections (49–51). Several mechanisms have been shown to play roles in this process, including direct interactions between the virus and the bacteria, increased nutrient availability, alteration of immune cell functions and cytokine milieu, and microbiome derangements (2). How many of these mechanisms are at play during coinfection with SARS-CoV-2 and S. aureus is a fascinating topic for future research.

It should be stated here that this study does not argue for broadly applied antibiotic treatment for patients with SARS-CoV-2 without indication. Antibiotics do not improve outcomes in COVID-19 patients without evidence of coinfection (52). Increasing antibiotic resistance is a major healthcare threat, and the COVID-19 pandemic has expanded this problem (53–55). Furthermore, COVID-19 patients treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics upon admission actually had higher rates of coinfections (56). As always, responsible antibiotic stewardship is of paramount importance.

In sum, we have described a cohort of S. aureus isolates recovered from both SARS-CoV-2+ and SARS-CoV-2− patients during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City and uncovered a link between SARS-CoV-2 infection and increased S. aureus pathogenesis when SARS-CoV-2/S. aureus coinfection is modeled in mice. Furthermore, the development of this murine SARS-CoV-2/S. aureus coinfection model should facilitate future studies exploring the mechanisms driving the lethal impact of SARS-CoV-2/S. aureus coinfections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Biorepository banking and bacterial strains

S. aureus clinical isolates were acquired from the NYU clinical microbiology lab. All S. aureus isolated from blood and respiratory samples by the clinical lab between March 29, 2020, and August 31, 2020 were collected. They were streaked on MSA plates, cultured overnight (ON) at 37°C, and a single colony was patched on trypticase soy agar (TSA) plates, grown ON at 37°C, and then frozen at −80°C. Isolates were then streaked again on MSA or TSA with 5% sheep blood (Henry Schein), and three pooled colonies for each isolate were used to seed 96 well plates with TSB for ON growth and freezing. Frozen 96 well plates were stamped on TSA agar for high-throughput assays.

The USA300 AH1263 (WT AH-LAC; VJT # 15.77) (57) and Δagr AH-LAC (VJT # 36.34) (58), and ΔlukΔhla AH-LAC (VJT # 58.79) (59) strains were used as controls for all in vitro assays, and Δagr AH-LAC was used for the coinfection of mice. All experiments involving recombinant S. aureus were performed according to protocols approved by the NYU Grossman School of Medicine Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC21-000096-01, Torres).

Genome sequencing, assembly, and annotation

The isolates were further purified from the frozen stocks by streaking on TSA with 5% sheep blood. Genomic DNA was extracted using the KingFisher Flex automated extraction instrument (Thermo Fisher) and the MagMAX DNA Multi-Sample Ultra 2.0 kit reagents (Applied Biosystems). Genome sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 device at the NYU Genome Technology Core, yielding 150 bp paired-end reads. This yielded a mean of 3.5 million read pairs per isolate (standard deviation: 1.1 million read pairs), corresponding to 1.05 Gbp (standard deviation: 0.37 Gbp) per isolate.

Raw reads were quality-filtered, trimmed, and stripped of adapters using fastp version 0.20.1 (60). The resulting reads were assembled into contigs using Unicycler version 0.4.8 (61) in conservative mode. Filtered, trimmed reads were then mapped to the assemblies using BWA 0.7.17 (62); isolates with mean depth below 100 were excluded from further analysis. Taxonomic classification of assembled genomes was performed using GTDBTK version 1.5.1 (63) using release 202 of the GTDB database (64). Only isolates whose assemblies were classified as S. aureus were further analyzed. Within-species (cross-strain) contamination was assessed using ConFindr version 0.7.4 (65), with isolates having estimated contamination greater than 10% excluded from further analysis. The mecA gene was detected and SCCmec types were determined using staphopia-sccmec (https://github.com/staphopia/staphopia-sccmec), part of the Staphopia pipeline (66).

Filtered and trimmed reads were mapped to a reference genome assembly of S. aureus strain FPR3757 (RefSeq accession number GCF_000013465.1) using Snippy version 4.6.0 (67); a core genome alignment was then generated using the Snippy command snippy-core. A phylogenetic tree was inferred from the resulting alignment using version 8.2.12 of RAxML (68) using the GTRGAMMA of nucleotide substitutions. Phylogenetic trees were visualized using the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL (69)). The software AgrVATE v.1.0.2 (70) was used to detect variants in the agr gene and predict their effects.

Growth curve, hemolysis, and color analysis of S. aureus isolates

Growth curve analysis was performed in TSB media using an Agilent BioTek LogPhase 600 Microbiology Reader. Isolates were each assayed three times and were designated as slow growers if the majority of their runs failed to reach an OD600 of 1.0. The curves of all three growth curves for each isolate are shown in Fig. S2a.

The color of the isolates was analyzed by taking pictures of the isolates stamped on TSA plates. The images were analyzed for % yellow using Photoshop in CMYK color mode, in order to quantify how yellow each isolate was. This was done three times for each isolate, and the % yellow was averaged.

The hemolytic capacity of the isolates was analyzed by patching them onto TSA plates with 5% sheep blood and growing overnight at 37°C. The plates were photographed and then placed a 4°C ON, and photographed again. Alpha-hemolysis was scored based on the original images before cold shock, in comparison to control lab strains AH-LAC, Δagr AH-LAC, and ΔlukΔhla AH-LAC. Beta-hemolysis was scored by comparing the images after cold shock to those before cold shock.

Cytotoxicity analysis of S. aureus isolates

Primary human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (hPMNs) were isolated from LeukoPaks of human blood samples as previously described (71). In order to facilitate most of the isolates reaching a similar OD, hPMNs were infected with S. aureus isolates after overnight culture. Overnight culture was performed in 125 µL TSB in a 96-well round bottom plate, at 37°C in a shaker at 180 rpm. Overnight cultures were washed in PBS, resuspended in 200 µL PBS, and 20 µL was used to infect 200,000 hPMNs in 80 µL RPMI 1640 with 0.1% Human Serum Albumin (HSA) and 0.01M HEPES. This resulted in an MOI of approximately 200 for those strains that were able to reach OD = 1 during overnight culture (Fig. S2a). hPMNs and S. aureus were then synchronized by centrifuging 1,500 rpm for 7 min at RT to bring them into close contact. After a 2 h infection at 37°C and 5% CO2, hPMN viability was determined by LDH release (CytoTox-ONE Homogeneous Membrane Integrity Assay, Promega), measured using the PerkinElmer Envision plate reader.

The hPMN viability was determined for eight blood donors for each S. aureus isolate. Within each donor’s data, the raw fluorescence signals across all isolates were normalized by z scoring. Thus, each assayed isolate received a z score for each of the eight donors; the median of these is referred to as the cytotoxicity z score in the text.

The isolates were grouped into high- and low-cytotoxicity categories. The mixtools R package version 1.2.0 (72) was used to infer a Gaussian mixture model (GMM) with k = 2 components corresponding to high and low cytotoxicity. Specifically, the normalmixEM function was applied to the cytotoxicity z scores, fitting a GMM model and assigning to each isolate a posterior probability of belonging to the high-cytotoxicity group. Isolates were labeled "high cytotoxicity" if this posterior probability was greater than 0.5, and "low cytotoxicity" otherwise.

Patient data analysis

Patients’ demographic and clinical data were extracted from Electronic Health Records (EHR) using structured SQL queries. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR). Discrete variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Infections were classified into nosocomial and community-acquired. Nosocomial infections were those acquired after 48 h of admission, community-acquired infections were those identified within the first 48 h since admission. The study encompassed cases recorded from March 24, 2020, to August 31, 2020. For a comprehensive mortality comparison with all SARS-CoV-2 cases, all patients who tested PCR-positive during the same period were included in the study. Co-infections were identified through a combination of positive PCR tests for SARS-CoV-2 and confirmed cultures for S. aureus. A case was considered a coinfection if the SARS-CoV-2 test was performed 15 days before the positive S. aureus culture or if the virus was detected up to 11 days after the culture. We included patients where SARS-CoV-2 was detected after the S. aureus infection because in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 tests were often delayed.

Viral culture and cell culture

Vero E6 cells (CRL-1586; American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Corning) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologics) and Penicillin/Streptomycin (Corning). SARS-CoV-2 isolate USA-WA1/2020, deposited by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, was obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH (cat. no. NR-52281; GenBank accession number MT233526). The stock was passaged in Vero E6 cells, and pooled medium was used to plaque purify a single virus clone on Vero E6 cells in the presence of 1 µg/mL l-1-tosylamido-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-trypsin to avoid virus adaptation to Vero E6 cells due to the lack of TMPRSS2 expression (65). Purified plaques were whole-genome sequenced to verify the presence of signature clade B amino acid changes, S D614G and NSP12 P323L, and the absence of furin cleavage site mutations, before expanding in the presence of TPCK-trypsin to generate a passage six working stock (5*10^5 PFU/mL) as described here (73). All SARS-CoV-2 stock preparations and subsequent infection assays were performed in

animal biosafety level 3 facility (ABSL3) of NYU Grossman School of Medicine (New York, NY), in accordance with its Biosafety Manual and Standard Operating Procedures. All experiments involving SARS-CoV-2 were performed according to protocols approved by the NYU Grossman School of Medicine Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC IBC22-000088, Dittmann).

Coinfection mouse model

Heterozygous K18-hACE2 C57BL/6 J mice (strain: 2B6.Cg-Tg(K18-ACE2)2Prlmn/J) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory or bred in-house. Animals were housed in groups and fed standard chow diets. All animal studies were performed according to protocols approved by the NYU Grossman School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC IA10-00071, Dittmann). Seventeen-week-old K18-hACE2 females were administered either 200 PFU SARS-CoV-2 diluted in 25 µL PBS (Corning) or mock-infected with 25 µL PBS via intranasal administration under xylazine-ketamine anesthesia (AnaSed AKORN Animal Health, Ketathesia Henry Schein Inc). Viral stocks were thawed, diluted to the working inoculum, and then stored at 4°C the day prior to infection. Viral titer in the inoculum was verified by plaque assay in Vero E6 cells. Two days post-SARS-CoV-2 infection, mice were infected with 3 × 108 CFU Δagr AH-LAC S. aureus or mock-infected with PBS intraperitoneally (IP). The S. aureus infection was performed via IP administration due to the technical difficulties of performing intravenous injections in a biosafety level 3 laboratory setting. Mice were monitored daily for weight loss and signs of disease. Disease score was based on weight loss, and the observation of reduced mobility, hunched posture, and ruffled fur. In some experiments, mice were sacrificed on day 4 post-SARS-CoV-2 infection to harvest their lungs, spleen, and kidneys.

Viral titer and bacterial burdens

Whole organs were collected in Eppendorf tubes containing 500 µL of PBS and a 5 mm stainless steel bead (Qiagen) and homogenized using the Qiagen TissueLyser II. One fraction of the homogenates was serially diluted in PBS and spotted on TSA plates for S. aureus Colony Forming Unit (CFU) enumeration, a second fraction was frozen at −80°C for plaque assay, and a third was diluted 4× in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and then frozen at −80°C for qRT-PCR. In some experiments, a lobe of the lung was fixed in formalin for histology analysis.

For plaque assay, Vero E6 cells were seeded at a density of 4.5 × 105 cells per well in flat-bottom 12-well tissue culture plates. The following day, media was removed and replaced with 100 µL of 10-fold serial dilutions of the virus stock, diluted in the infection medium. Plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Following incubation, cells were overlaid with 0.8% agarose in DMEM containing 2% FBS and incubated at 37°C for 72 h. Cells were then fixed with formalin buffered 10% (Fisher Chemical) for 1 h. Agarose plugs were then removed, and cells were stained for 20 min with crystal violet and then washed with tap water.

For RT-qPCR, RNA was extracted from the TRIzol homogenates using chloroform separation and isopropanol precipitation, followed by additional purification using RNA columns according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Direct-zol, ZYMO research). RNA was reverse-transcribed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). To assess viral titer, qPCR was performed using Applied Biosystems TaqMan RNA-to-CT One-Step Kit (Fisher-Scientific), 500 nM of the primers (Fwd 5′-ATGCTGCAATCGTGCTACAA-3′, Rev 5′-GACTGCCGCCTCTGCTC-3′) and 100 nM of the N probe (5’-/56-FAM/TCAAGGAAC/ZEN/AACATTGCCAA/3IABkFQ/−3’). qPCR reaction conditions were 48°C for 15 min followed by 95°C for 2 min, and by 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, and 60°C for 1 min. Serial dilutions of in vitro-transcribed RNA of the SARS-CoV-2 Nucleoprotein were used to generate a standard curve and calculate copy numbers per mg of RNA in the samples.

Cytokine profiling

Cytokine profiles were determined using the MILLIPLEX Mouse Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead Panel 32 PLEX kit (Millipore Sigma). In brief, sera from SARS-CoV-2-infected mice, S. aureus-infected mice, SARS-CoV-2 and S. aureus coinfected mice, or mock-infected mice were inactivated with UV-C (254 nm) treatment, with a power density of 4,016 μW/cm2, for 15 min at a distance of 3 cm to allow removal of the samples from the ABSL3 facility. Following the kit’s instructions, premixed magnetic beads that bind specific cytokines were incubated with the mouse sera (12.5 µL; 1:2 dilution), standards, background, and quality control samples in a black 96-well plate for 2 h at room temperature with shaking at 650 rpm. The plate was washed three times on a magnet, then incubated with detection antibody for 1 h at room temperature with shaking at 650 rpm. Streptavidin-phycoerythrin was then added to each well and incubated for an additional 30 min at room temperature with shaking at 650 rpm. The plate was washed two times on a magnet. The beads were resuspended in drive fluid and run on a Luminex MAGPIX Multiplexing System with xPONENT software. Calculation of cytokine concentration per milliliter of serum was performed by the software. Data were exported from xPONENT and imported into Graphpad Prism 9 software.

Statistics statement

Statistical significance was determined using Prism 7.0 b, with Mann-Whitney test, Kurksal-Wallis test, log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, or Fisher’s exact test as indicated.

For patient data analyses, The Kaplan-Meier (KM) method was employed to estimate survival curves, with the Wilcoxon-Breslow test being utilized to compare the survival curves amongst different patient groups. P values for the data in Table 1 were determined by the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test for continuous variables χ test for categorical variables.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the tireless healthcare workers at NYU Langone Health who provided care to the patients described herein during the height of the pandemic. We also thank the members of the NYU Langone Health clinical microbiology lab for training and working with the team to enable the collection of the COVID biorepository of superinfecting pathogens, and the knowledgeable members of the NYU Langone’s Genome Technology Center for performing all the S. aureus genome sequencing. We also thank the Office of Science & Research High-Containment Laboratories at NYU Grossman School of Medicine for their support in the completion of this research. Lastly, we thank Dr. Alex Horswill (University of Colorado) for kindly providing us with the AH1263 LAC strain.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants AI137336 (B.S. and V.J.T.), AI140754 (B.S., K.C., and V.J.T.), AI105129 and AI099394 (V.J.T.), and AI143639 (M.D.); NYU Grossman School of Medicine COVID-19 seed research funds (M.D. and V.J.T.); and funds from the NYU Langone Health Antimicrobial-Resistant Pathogens Program (A.P., B.S., and V.J.T.). The NYU Langone’s Genome Technology Center was supported in part by the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center.

A.L. and V.J.T. designed the study. S.D, S.D, C.H, J.K.I., G.L.I., M.P., A.P., S.P., W.E.S., I.S., A.S.J., R.T., X.Z., C.Z., E.E.Z., and A.L. collected and banked isolates from the medical microbiology lab, facilitated by K.I. A.L., L.B.R., A.L.D, A.M.V.J., E.E.Z., M.G.N., A.O, M.P., S.G, K.B., and A.I.P. performed the experiments. A.M.V.J. trained A.L., L.B.R., and A.L.D. in BSL3 experimentation. J.G., G.G.P., O.O., and A.P. performed the bioinformatic analyses and M.D., B.S., K.C., and V.J.T managed the project. L.D., S.H., K.A.S., and L.E.T. contributed materials, biosafety, and scientific feedback. A.L. wrote the first draft of the manuscript and A.L.D., L.B.R., and V.J.T. worked on the final version of the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Footnotes

This article is a direct contribution from Victor J. Torres, a Fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology, who arranged for and secured reviews by James E. Cassat, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and Vineet D. Menachery, The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

Contributor Information

Meike Dittmann, Email: Meike.Dittman@nyulangone.org.

Victor J. Torres, Email: Victor.Torres@stjude.org.

Nancy E. Freitag, University of Illinois Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA

ETHICS APPROVAL

Approval for sample collection and analysis was granted by the NYU Langone Health Institutional Review Board (protocol i19-01037). Blood was obtained from healthy, de-identified, consenting adult donors as buffy coats from the New York Blood Center. All experiments involving animals were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of New York University and were performed according to guidelines from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Animal Welfare Act, and US Federal Law.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The assigned NCBI BioProject accession number for the genome sequences is PRJNA1123240.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.01667-24.

Figures S1-S4.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jakab GJ. 1981. Mechanisms of virus-induced bacterial superinfections of the lung. Clin Chest Med 2:59–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rossi GA, Fanous H, Colin AA. 2020. Viral strategies predisposing to respiratory bacterial superinfections. Pediatr Pulmonol 55:1061–1073. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bassetti M, Kollef MH, Timsit JF. 2020. Bacterial and fungal superinfections in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Intensive Care Med 46:2071–2074. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06219-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clancy CJ, Schwartz IS, Kula B, Nguyen MH. 2021. Bacterial superinfections among persons with coronavirus disease 2019: a comprehensive review of data from postmortem studies. Open Forum Infect Dis 8:ofab065. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chong WH, Saha BK, Ramani A, Chopra A. 2021. State-of-the-art review of secondary pulmonary infections in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Infection 49:591–605. doi: 10.1007/s15010-021-01602-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buehler PK, Zinkernagel AS, Hofmaenner DA, Wendel Garcia PD, Acevedo CT, Gómez-Mejia A, Mairpady Shambat S, Andreoni F, Maibach MA, Bartussek J, Hilty MP, Frey PM, Schuepbach RA, Brugger SD. 2021. Bacterial pulmonary superinfections are associated with longer duration of ventilation in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Cell Rep Med 2:100229. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koehler P, Cornely OA, Böttiger BW, Dusse F, Eichenauer DA, Fuchs F, Hallek M, Jung N, Klein F, Persigehl T, Rybniker J, Kochanek M, Böll B, Shimabukuro‐Vornhagen A. 2020. COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses 63:528–534. doi: 10.1111/myc.13096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Janssen NAF, Nyga R, Vanderbeke L, Jacobs C, Ergün M, Buil JB, van Dijk K, Altenburg J, Bouman CSC, van der Spoel HI, et al. 2021. Multinational observational cohort study of COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis(1). Emerg Infect Dis 27:2892–2898. doi: 10.3201/eid2711.211174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gago J, Filardo TD, Conderino S, Magaziner SJ, Dubrovskaya Y, Inglima K, Iturrate E, Pironti A, Schluter J, Cadwell K, Hochman S, Li H, Torres VJ, Thorpe LE, Shopsin B. 2022. Pathogen species is associated with mortality in nosocomial bloodstream infection in patients with COVID-19. Open Forum Infect Dis 9:fac083. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giacobbe DR, Battaglini D, Ball L, Brunetti I, Bruzzone B, Codda G, Crea F, De Maria A, Dentone C, Di Biagio A, Icardi G, Magnasco L, Marchese A, Mikulska M, Orsi A, Patroniti N, Robba C, Signori A, Taramasso L, Vena A, Pelosi P, Bassetti M. 2020. Bloodstream infections in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Eur J Clin Invest 50:e13319. doi: 10.1111/eci.13319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arastehfar A, Carvalho A, Nguyen MH, Hedayati MT, Netea MG, Perlin DS, Hoenigl M. 2020. COVID-19-associated candidiasis (CAC): an underestimated complication in the absence of immunological predispositions? J Fungi (Basel) 6:211. doi: 10.3390/jof6040211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cusumano JA, Dupper AC, Malik Y, Gavioli EM, Banga J, Berbel Caban A, Nadkarni D, Obla A, Vasa CV, Mazo D, Altman DR. 2020. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in patients infected with COVID-19: a case series. Open Forum Infect Dis 7:faa518. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Adalbert JR, Varshney K, Tobin R, Pajaro R. 2021. Clinical outcomes in patients co-infected with COVID-19 and Staphylococcus aureus: a scoping review. BMC Infect Dis 21:985. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06616-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Falces-Romero I, Bloise I, García-Rodríguez J, Cendejas-Bueno E, Montero-Vega MD, Romero MP, García-Bujalance S, Toro-Rueda C, Ruiz-Carrascoso G, Quiles-Melero I. 2023. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Med Clin (Engl Ed) 160:495–498. doi: 10.1016/j.medcle.2023.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Westblade LF, Simon MS, Satlin MJ. 2021. Bacterial coinfections in coronavirus disease 2019. Trends Microbiol 29:930–941. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2021.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. DeLeo FR, Diep BA, Otto M. 2009. Host defense and pathogenesis in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am 23:17–34. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tam K, Torres VJ. 2019. Staphylococcus aureus secreted toxins and extracellular enzymes. Microbiol Spectr 7. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0039-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seilie ES, Bubeck Wardenburg J. 2017. Staphylococcus aureus pore-forming toxins: the interface of pathogen and host complexity. Semin Cell Dev Biol 72:101–116. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Spaan AN, van Strijp JAG, Torres VJ. 2017. Leukocidins: staphylococcal bi-component pore-forming toxins find their receptors. Nat Rev Microbiol 15:435–447. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cosgrove SE, Sakoulas G, Perencevich EN, Schwaber MJ, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y. 2003. Comparison of mortality associated with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 36:53–59. doi: 10.1086/345476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ho KM, Robinson JO. 2009. Risk factors and outcomes of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in critically ill patients: a case control study. Anaesth Intensive Care 37:457–463. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0903700320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pruneau M, Mitchell G, Moisan H, Dumont-Blanchette E, Jacob CL, Malouin F. 2011. Transcriptional analysis of antibiotic resistance and virulence genes in multiresistant hospital-acquired MRSA. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 63:54–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00830.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rose HR, Holzman RS, Altman DR, Smyth DS, Wasserman GA, Kafer JM, Wible M, Mendes RE, Torres VJ, Shopsin B. 2015. Cytotoxic virulence predicts mortality in nosocomial pneumonia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis 211:1862–1874. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. He L, Meng H, Liu Q, Hu M, Wang Y, Chen X, Liu X, Li M. 2018. Distinct virulent network between healthcare- and community-associated Staphylococcus aureus based on proteomic analysis. Clin Proteomics 15:2. doi: 10.1186/s12014-017-9178-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jenkins TC, McCollister BD, Sharma R, McFann KK, Madinger NE, Barron M, Bessesen M, Price CS, Burman WJ. 2009. Epidemiology of healthcare-associated bloodstream infection caused by USA300 strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in 3 affiliated hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 30:233–241. doi: 10.1086/595963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sherwood J, Park M, Robben P, Whitman T, Ellis MW. 2013. USA300 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus emerging as a cause of bloodstream infections at military medical centers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 34:393–399. doi: 10.1086/669866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thurlow LR, Joshi GS, Richardson AR. 2012. Virulence strategies of the dominant USA300 lineage of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA). FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 65:5–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00937.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dyzenhaus S, Sullivan MJ, Alburquerque B, Boff D, van de Guchte A, Chung M, Fulmer Y, Copin R, Ilmain JK, O’Keefe A, Altman DR, Stubbe F-X, Podkowik M, Dupper AC, Shopsin B, van Bakel H, Torres VJ. 2023. MRSA lineage USA300 isolated from bloodstream infections exhibit altered virulence regulation. Cell Host Microbe 31:228–242. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2022.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jenul C, Horswill AR. 2019. Regulation of Staphylococcus aureus virulence. Microbiol Spectr 7. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0031-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Traber KE, Lee E, Benson S, Corrigan R, Cantera M, Shopsin B, Novick RP. 2008. agr function in clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Microbiology (Reading) 154:2265–2274. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/011874-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Skaar EP, Humayun M, Bae T, DeBord KL, Schneewind O. 2004. Iron-source preference of Staphylococcus aureus infections. Science 305:1626–1628. doi: 10.1126/science.1099930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clauditz A, Resch A, Wieland K-P, Peschel A, Götz F. 2006. Staphyloxanthin plays a role in the fitness of Staphylococcus aureus and its ability to cope with oxidative stress. Infect Immun 74:4950–4953. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00204-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Alonzo F III, Torres VJ. 2014. The bicomponent pore-forming leucocidins of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 78:199–230. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00055-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhao X, Chlebowicz-Flissikowska MA, Wang M, Vera Murguia E, de Jong A, Becher D, Maaß S, Buist G, van Dijl JM. 2020. Exoproteomic profiling uncovers critical determinants for virulence of livestock-associated and human-originated Staphylococcus aureus ST398 strains. Virulence 11:947–963. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2020.1793525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pivonello R, Auriemma RS, Pivonello C, Isidori AM, Corona G, Colao A, Millar RP. 2021. Sex disparities in COVID-19 severity and outcome: are men weaker or women stronger? Neuroendocrinology 111:1066–1085. doi: 10.1159/000513346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Alonzo F, Benson MA, Chen J, Novick RP, Shopsin B, Torres VJ. 2012. Staphylococcus aureus leucocidin ED contributes to systemic infection by targeting neutrophils and promoting bacterial growth in vivo. Mol Microbiol 83:423–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07942.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McCray PB, Pewe L, Wohlford-Lenane C, Hickey M, Manzel L, Shi L, Netland J, Jia HP, Halabi C, Sigmund CD, Meyerholz DK, Kirby P, Look DC, Perlman S. 2007. Lethal infection of K18-hACE2 mice infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol 81:813–821. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02012-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Goncheva MI, Gibson RM, Shouldice AC, Dikeakos JD, Heinrichs DE. 2023. The Staphylococcus aureus protein IsdA increases SARS CoV-2 replication by modulating JAK-STAT signaling. iScience 26:105975. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.105975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bernard-Raichon L, Venzon M, Klein J, Axelrad JE, Zhang C, Sullivan AP, Hussey GA, Casanovas-Massana A, Noval MG, Valero-Jimenez AM, Gago J, Putzel G, Pironti A, Wilder E, Yale IRT, Thorpe LE, Littman DR, Dittmann M, Stapleford KA, Shopsin B, Torres VJ, Ko AI, Iwasaki A, Cadwell K, Schluter J. 2022. Gut microbiome dysbiosis in antibiotic-treated COVID-19 patients is associated with microbial translocation and bacteremia. Nat Commun 13:5926. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33395-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Varghese GM, John R, Manesh A, Karthik R, Abraham OC. 2020. Clinical management of COVID-19. Indian J Med Res 151:401–410. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_957_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yacouba A, Olowo-Okere A, Yunusa I. 2021. Repurposing of antibiotics for clinical management of COVID-19: a narrative review. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 20:37. doi: 10.1186/s12941-021-00444-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nasonov E, Samsonov M. 2020. The role of interleukin 6 inhibitors in therapy of severe COVID-19. Biomed Pharmacother 131:110698. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Suzuki T, Yoshinaga N, Tanabe S. 2011. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) regulates claudin-2 expression and tight junction permeability in intestinal epithelium. J Biol Chem 286:31263–31271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.238147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kimmig LM, Wu D, Gold M, Pettit NN, Pitrak D, Mueller J, Husain AN, Mutlu EA, Mutlu GM. 2020. IL-6 inhibition in critically ill COVID-19 patients is associated with increased secondary infections. Front Med 7:583897. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.583897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Konturek PC, Herrmann HJ, Schink K, Neurath MF, Zopf Y. 2015. Malnutrition in hospitals: it was, is now, and must not remain a problem! Med Sci Monit 21:2969–2975. doi: 10.12659/MSM.894238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shells R, Morrell-Scott N. 2018. Prevention of dehydration in hospital patients. Br J Nurs 27:565–569. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2018.27.10.565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Collins N, Belkaid Y. 2022. Control of immunity via nutritional interventions. Immunity 55:210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2022.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Barman TK, Singh AK, Bonin JL, Nafiz TN, Salmon SL, Metzger DW. 2022. Lethal synergy between SARS-CoV-2 and Streptococcus pneumoniae in hACE2 mice and protective efficacy of vaccination. JCI Insight 7. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.159422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mulcahy ME, McLoughlin RM. 2016. Staphylococcus aureus and influenza A virus: partners in coinfection. mBio 7. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02068-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Deinhardt-Emmer S, Haupt KF, Garcia-Moreno M, Geraci J, Forstner C, Pletz M, Ehrhardt C, Löffler B. 2019. Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia: preceding influenza infection paves the way for low-virulent strains. Toxins 11:734. doi: 10.3390/toxins11120734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stockman LJ, Reed C, Kallen AJ, Finelli L, Anderson LJ. 2010. Respiratory syncytial virus and Staphylococcus aureus coinfection in children hospitalized with pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J 29:1048–1050. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181eb7315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chedid M, Waked R, Haddad E, Chetata N, Saliba G, Choucair J. 2021. Antibiotics in treatment of COVID-19 complications: a review of frequency, indications, and efficacy. J Infect Public Health 14:570–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Clancy CJ, Nguyen MH. 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019, superinfections, and antimicrobial development: what can we expect? Clin Infect Dis 71:2736–2743. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Owoicho O, Tapela K, Djomkam Zune AL, Nghochuzie NN, Isawumi A, Mosi L. 2021. Suboptimal antimicrobial stewardship in the COVID-19 era: is humanity staring at a postantibiotic future? Future Microbiol 16:919–925. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2021-0008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lai CC, Chen SY, Ko WC, Hsueh PR. 2021. Increased antimicrobial resistance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Antimicrob Agents 57:106324. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2021.106324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Grasselli G, Scaravilli V, Mangioni D, Scudeller L, Alagna L, Bartoletti M, Bellani G, Biagioni E, Bonfanti P, Bottino N, et al. 2021. Hospital-acquired infections in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Chest 160:454–465. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Boles BR, Thoendel M, Roth AJ, Horswill AR. 2010. Identification of genes involved in polysaccharide-independent Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. PLoS One 5:e10146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Benson MA, Lilo S, Wasserman GA, Thoendel M, Smith A, Horswill AR, Fraser J, Novick RP, Shopsin B, Torres VJ. 2011. Staphylococcus aureus regulates the expression and production of the staphylococcal superantigen-like secreted proteins in a Rot-dependent manner. Mol Microbiol 81:659–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07720.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Blake KJ, Baral P, Voisin T, Lubkin A, Pinho-Ribeiro FA, Adams KL, Roberson DP, Ma YC, Otto M, Woolf CJ, Torres VJ, Chiu IM. 2018. Staphylococcus aureus produces pain through pore-forming toxins and neuronal TRPV1 that is silenced by QX-314. Nat Commun 9:37. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02448-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J. 2018. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34:i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. 2017. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol 13:e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chaumeil PA, Mussig AJ, Hugenholtz P, Parks DH. 2019. GTDB-TK: a toolkit to classify genomes with the genome taxonomy database. Bioinformatics 36:1925–1927. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Parks DH, Chuvochina M, Rinke C, Mussig AJ, Chaumeil PA, Hugenholtz P. 2022. GTDB: an ongoing census of bacterial and archaeal diversity through a phylogenetically consistent, rank normalized and complete genome-based taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res 50:D785–D794. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Low AJ, Koziol AG, Manninger PA, Blais B, Carrillo CD. 2019. ConFindr: rapid detection of intraspecies and cross-species contamination in bacterial whole-genome sequence data. PeerJ 7:e6995. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Petit RA, Read TD. 2018. Staphylococcus aureus viewed from the perspective of 40,000+ genomes. PeerJ 6:e5261. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Seemann T. 2015. snippy: fast bacterial variant calling from NGS reads. Available from: https://github.com/tseemann/snippy

- 68. Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Letunic I, Bork P. 2021. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 49:W293–W296. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Raghuram V, Alexander AM, Loo HQ, Petit RA III, Goldberg JB, Read TD. 2022. Species-wide phylogenomics of the Staphylococcus aureus AGR operon revealed convergent evolution of frameshift mutations. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0133421. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01334-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. DuMont AL, Yoong P, Surewaard BGJ, Benson MA, Nijland R, van Strijp JAG, Torres VJ. 2013. Staphylococcus aureus elaborates Leukocidin AB to mediate escape from within human neutrophils. Infect Immun 81:1830–1841. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00095-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Benaglia T, Chauveau D, Hunter DR, Young DS. 2009. Mixtools: an R package for analyzing finite mixture models. J Stat Softw 32:1–29. doi: 10.18637/jss.v032.i06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73. de Vries M, Mohamed AS, Prescott RA, Valero-Jimenez AM, Desvignes L, O’Connor R, Steppan C, Devlin JC, Ivanova E, Herrera A, Schinlever A, Loose P, Ruggles K, Koralov SB, Anderson AS, Binder J, Dittmann M. 2021. A comparative analysis of SARS-CoV-2 antivirals characterizes 3CLpro inhibitor PF-00835231 as a potential new treatment for COVID-19. J Virol 95:e01819-20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01819-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1-S4.

Data Availability Statement

The assigned NCBI BioProject accession number for the genome sequences is PRJNA1123240.