Abstract

Psychedelics paired with new applications of computational tools might help bypass the imprecision of psychiatric diagnosis and connect measures of behavior to specific physiologic targets.

Psychedelics are having their moment—in terms of both financial investment and rigorous empirical study. Controversial drugs with a long and colorful cultural history, psychedelic compounds have only recently experienced what some call a renaissance, driven, in part, by investor enthusiasm to tap an estimated $10.75 billion market (1). As psychiatrists, we think the expectation that a series of centuries-old drugs might sweep in and tap a $10.75 billion market reflects how poorly investors believe that psychiatrists are meeting the needs of our patients (1).

They are not wrong: Only a third of patients respond to first-line antidepressant treatment, while another third has a partial response and a final third does not respond at all (2). The problem is not the drug—drugs are just molecular tools—but rather, not pairing the right tool with the right patient. The task facing the companies and researchers developing psychedelic compounds is to identify which specific compounds alleviate which specific types of human suffering. In other words, they know which compounds to study and who may benefit from them and the magnitude of the benefit.

One of the reasons why Big Pharma has largely withdrawn from psychiatric drug development is that identifying which people a drug can benefit is highly complex. In psychiatry, we treat patients who might look alike but are biologically quite different. The precision of DSM-V checklists and symptom questionnaires—our primary method for diagnosing and assessing psychiatric disease severity—is insufficient to guide drug development. The language of psychiatric illness is symptoms, the language of pharmacology is molecules, and right now, we have no Rosetta stone that translates symptoms to molecules and can help us match the right drug to the right patient.

Consider how a new drug to treat sore throat is tested: Drug companies gather people who have sore throats, culture their throats to identify the cause (i.e., Streptococcus, influenza, or HIV), and then enroll patients in a trial based on whether the causative agent was susceptible to the candidate drug. The trial relies on the throat culture to translate an otherwise ambiguous “sore throat” into a molecular target, thereby identifying which patients the candidate drug is most likely to benefit. (Imagine what would happen if researchers tested a new antibiotic on sore throats caused by influenza. Nothing, of course.)

Psychiatry needs a Rosetta stone to translate a patient’s psychiatric symptoms into molecular treatment targets. In this issue of Science Advances, Ballentine et al. (3) report a new technique that offers promising first steps toward such a tool. Their method provides a way to bypass the imprecision of symptom-based assessments, like the DSM-V and standardized questionnaires, allowing researchers to quantitatively marry real-world reports about psychedelic drug experiences, drug receptor binding affinities, gene transcription profiles, and the human brain.

Psilocin—the active metabolite of psilocybin, the psychedelic compound in “magic mushrooms”—was one of the 27 drugs evaluated in Ballentine et al.’s study. Using a method that quantifies language structure, the researchers looked across 6850 written reports of real-world drug experiences with various psychedelic drugs and computed which experiential themes were most associated with psilocin. These themes were, in turn, associated with the neurotransmitter receptors that psilocin is known to engage in the brain. Because the genetic expression of these neurotransmitter receptors has been mapped within the brain’s structure, Ballentine et al. connected psilocybin’s “receptor-experience profiles” to the brain’s genetic and functional network architecture. Overall, Ballentine’s method quantitatively translates a person’s experience into the molecular profiles responsible for that experience.

Ballentine et al. provide the foundation to quantitatively link drug-induced changes in consciousness to the location in the brain where these changes take place: In essence, they allow us to interpret changes in behavior based on the specific physiologic action of each drug. This opens the door to translating real-time behavioral changes into molecular treatment targets, and (one might hope) to measuring how individual variance in behavior relates to individual variance in physiology. In essence, this method could help us understand how a given molecular tool might improve or even fix a clinically relevant behavioral problem.

In a truly remarkable way, the study was performed at essentially no additional cost. Ballentine et al. (3) made use of existent, openly available resources: the Erowid psychedelic “experience vault,” the pharmacokinetic profiles of each psychedelic, the Allen Human Brain gene transcription profiles, and the Schafer-Yeo brain atlas that mapped gene transcript to brain structure. The computational tools—primarily python toolboxes—that Ballentine et al. deployed were also available at no cost. So in the same way that the psychedelics industry is repurposing old drugs, Ballentine et al. repurposed old data and tools to define a new framework.

In this context, Ballentine’s work is even more impressive. Future work could shed light on important questions related to clinical utility. For example, looking through the Erowid database, one realizes that rich as these psychedelic reports are, many were recorded years after the actual psychedelic event; clearly, real-time experiences would be preferred. As the authors noted, there is further reason to suspect significant variability in, e.g., the amount of psilocin in a magic mushroom, because it is well known that chemical composition and potency depend on the growth substrate, harvest date, and storage environment. Controlled administration of isolated, research-grade compounds would be a logical next step.

Future studies might include other forms of data that psychiatrists believe are relevant to mental illness. Activity, mood, and sociability are routinely evaluated in clinical care, whether with questionnaires or diagnostic scales. Just as Ballentine et al. (3) bypassed symptom questionnaires and captured individual-level real-world behavior, we can readily measure activity, mood, and sociability with digital tools, suggesting additional data streams that their framework might translate to molecular targets.

The challenge facing drug companies developing psychedelic compounds is to not prematurely discard a controversial compound that may have a yet-unproven promise—testing an antibiotic on a sore throat caused by a virus. The basis for treatment must be rigorous data—not biased opinion or uninformed enthusiasm. Ballentine’s method might help us progress toward this goal. Bypassing the imprecision of psychiatric symptoms by connecting behavior directly to physiology very well could help identify which specific psychedelic compounds could benefit which specific patients.

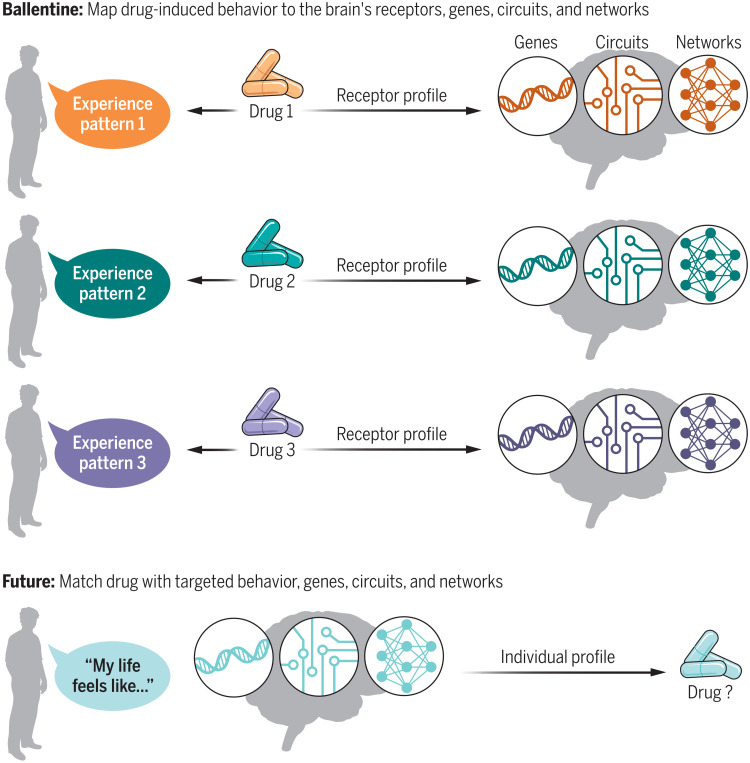

If proven to be helpful, such a translational Rosetta stone could entice the drug industry back into psychiatric drug research and development Fig. 1. Instead of proposing that a given compound improves the severity of “depression,” Ballentine et al.’s framework offers a more pragmatic approach to testing what a drug might reasonably accomplish: adjusting specific behaviors that reflect a compound’s specific physiologic effect.

Overall, as clinicians, we remain optimistic. We certainly hope that the financial investment in psychedelics translates into real-world changes that can help us better diagnose and treat our patients. But for us to even consider using psychedelics in our clinical practice, we need solid proof of their safety and efficacy and that these compounds yield measurable improvements in our patients’ lives.

Fig. 1. Translating behavior to drug physiology.

In a clever application of openly available data and tools, Ballentine et al. connect receptor-experience profiles to the genes, circuits, and networks in the brain that are engaged by a drug. To do this, they translate a person’s written experience with a psychedelic drug to the neurotransmitter receptors underlying that experience. In the future, such a tool might help identify which drug could benefit a given patient based on their individual behavior, genetic profile, and brain function. Credit: Kellie Holoski/Science Advances.

REFERENCES

- 1.Phelps J., Shah R. N., Lieberman J. A., The rapid rise in investment in psychedelics—Cart before the horse. JAMA Psychiat. 79, 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.3972, (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaynes B. N., Warden D., Trivedi M. H., Wisniewski S. R., Fava M., Rush A. J., What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Psychiatr. Serv. 60, 1439–1445 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballentine G., Friedman S. F., Bzdok D., Trips and neurotransmitters: Discovering principled patterns across 6850 hallucinogenic experiences. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl6989 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]