Abstract

Background

More than 30 years into the global HIV/AIDS epidemic, infection rates remain alarmingly high, with over 2.7 million people becoming infected every year. There is a need for HIV prevention strategies that are more effective. Oral antiretroviral pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in high‐risk individuals may be a reliable tool in preventing the transmission of HIV.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of oral antiretroviral chemoprophylaxis in preventing HIV infection in HIV‐uninfected high‐risk individuals.

Search methods

We revised the search strategy from the previous version of the review and conducted an updated search of MEDLINE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and EMBASE in April 2012. We also searched the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and ClinicalTrials.gov for ongoing trials.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials that evaluated the effects of any antiretroviral agent or combination of antiretroviral agents in preventing HIV infection in high‐risk individuals

Data collection and analysis

Data concerning outcomes, details of the interventions, and other study characteristics were extracted by two independent authors using a standardized data extraction form. Relative risk with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was used as the measure of effect.

Main results

We identified 12 randomised controlled trials that meet the criteria for the review. Six were ongoing trials, four had been completed and two had been terminated early. Six studies with a total of 9849 participants provided data for this review. The trials evaluated the following: daily oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) plus emtricitabine (FTC) versus placebo; TDF versus placebo and daily TDF‐FTC versus intermittent TDF‐FTC. One of the trials had three study arms: TDF, TDF‐FTC and placebo arm. The studies were carried out amongst different risk groups, including HIV‐uninfected men who have sex with men, serodiscordant couples and other high risk men and women.

Overall results from the four trials that compared TDF‐FTC versus placebo showed a reduction in the risk of acquiring HIV infection (RR 0.49; 95% CI 0.28 to 0.85; 8918 participants). Similarly, the overall results of the studies that compared TDF only versus placebo showed a significant reduction in the risk of acquiring HIV infection (RR 0.33; 95% CI 0.20 to 0.55, 4027 participants). There were no significant differences in the risk of adverse events across all the studies that reported on adverse events. Also, adherence and sexual behaviours were similar in both the intervention and control groups.

Authors' conclusions

Finding from this review suggests that pre‐exposure prophylaxis with TDF alone or TDF‐FTC reduces the risk of acquiring HIV in high‐risk individuals including people in serodiscordant relationships, men who have sex with men and other high risk men and women.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Male; Premedication; Adenine; Adenine/administration & dosage; Adenine/analogs & derivatives; Adenine/therapeutic use; Administration, Oral; Anti‐HIV Agents; Anti‐HIV Agents/administration & dosage; Anti‐HIV Agents/therapeutic use; Deoxycytidine; Deoxycytidine/administration & dosage; Deoxycytidine/analogs & derivatives; Deoxycytidine/therapeutic use; Drug Therapy, Combination; Drug Therapy, Combination/methods; Emtricitabine; HIV Infections; HIV Infections/prevention & control; Organophosphonates; Organophosphonates/administration & dosage; Organophosphonates/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Risk; Risk‐Taking; Tenofovir; Unsafe Sex

Plain language summary

Antiretroviral pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for preventing HIV in high‐risk individuals

This review evaluated the effects of giving people at high risk for HIV infection drugs to prevent infection (called antiretroviral pre‐exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP). We found six randomised controlled trials that assessed the effects of oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) plus emtricitabine (FTC) versus placebo; TDF versus placebo, and daily TDF‐FTC versus intermittent TDF‐FTC. One of the trials had three study arms (TDF, TDF‐FTC and placebo arm). The trials were carried out amongst different risk groups, including HIV‐uninfected men who have sex with men, people in serodiscordant sexual relationships where one partner is infected and the other is not, and other high risk men and women. The findings suggests that the use of TDF alone or TDF+FTC reduces the risk of becoming infected with HIV. However, further studies are need to evaluate the method of administration (daily versus intermittent dosing), long‐term safety and cost effectiveness of PrEP in different risk groups and settings.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. TDF+ FTC compared to placebo for preventing HIV in high‐risk individuals.

| Tenofovir + Emtricitabine compared to placebo for preventing HIV in high‐risk individuals | ||||||

| Patient or population: High‐risk HIV‐uninfected individuals (including serodiscordant couples, men who have sex with men and sex workers) Settings: High, middle and low income settings Intervention: Oral Tenofovir + Emtricitabine Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | TDF+ FTC | |||||

| HIV infection | Study population | RR 0.49 (0.28 to 0.85) | 8813 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | ||

| 39 per 1000 | 19 per 1000 (11 to 33) | |||||

| Serious adverse events | Study population |

RR 1 (0.83 to 1.19) |

6862 (3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | ||

| 65 per 1000 | 65 per 1000 (54 to 77) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level on account of instability of results since there are fewer than 200 events per arm.

Summary of findings 2. TDF compared to placebo for preventing HIV in high‐risk individuals.

| Tenofovir compared to placebo for preventing HIV in high‐risk individuals | ||||||

| Patient or population: High‐risk individuals (including serodiscordant couples, men who have sex with men and sex workers) Settings: High, middle and low income settings Intervention: Oral Tenofovir Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | TDF | |||||

| HIV infection | Study population | RR 0.33 (0.20 to 0.55) | 4027 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | ||

| 29 per 1000 | 9 per 1000 (6 to 16) | |||||

| Serious adverse events | Study population | RR 1.03 (0.79 to 1.33) | 3168 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Moderate1 | ||

| 66 per 1000 | 68 per 1000 (52 to 88) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level on account of instability of results since there are fewer than 200 events per arm.

Background

The global incidence of HIV infection has been declining in many countries, with a total of 2.7 million infections in 2010 compared to 3.1 million in 2001 (WHO 2011). However, incidence still remains high, and Sub‐Saharan Africa continues to bear much of the global HIV burden. In 2010, about 68% of all people living with HIV in the world resided in the sub‐Saharan Africa (WHO 2011). To stem the high infection rate, safe and effective approaches to HIV prevention are needed. Behaviour change programmes have contributed to reductions in the number of new infections in many countries, but too many people remain at high risk.

Biomedical tools in combination with effective behavioral interventions are required to adequately curb the spread of the virus (Derdelinckx 2006). Antiretroviral drugs also are currently used to prevent HIV transmission in various settings. In a double blind microbicide trial conducted in South Africa, a vaginal gel containing tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) plus emtricitabine (FTC) preparation was found to be 39% per cent effective in reducing HIV transmission among women considered to be at high risk of HIV infection (Abdool Karim 2010). There is substantial evidence that timely administration of antiretroviral drugs reduces the risk of HIV transmission from HIV‐infected mothers to their infants in the prenatal and perinatal periods (Guay 1999; Siegfried 2011). Antiretroviral drugs are currently the cornerstone of prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV. Early initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been shown to reduce the rate of sexual transmission of HIV‐1 and clinical events in couples in serodiscordant couples (Anglemyer 2011; Cohen 2011; Donnell 2010). Also, post‐exposure prophylaxis (PEP) has been shown to reduce the risk of HIV infection after occupational percutaneous or mucous membrane exposure to HIV because of a needlestick injury or after unprotected sexual intercourse if administered shortly after exposure (Smith 2005; Young 2007).

Description of the intervention

PrEP is a new approach in which antiretroviral drugs are taken by an HIV‐uninfected individual prior to HIV exposure to reduce the likelihood of infection. It should be distinguished from PEP, in which an uninfected individual takes antiretroviral drugs soon after a potential HIV exposure, with the aim of reducing the likelihood of infection (Sharifi‐Azad 2011). Two promising drugs that are currently being considered for use in HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis are TDF and the combination TDF‐FTC. TDF and FTC are both nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors. These medications have been chosen as agents for PrEP because of their excellent safety record, a favourable resistance profile and limited side effects (Derdelinckx 2006). These drugs stop HIV from multiplying by preventing the reverse transcriptase enzyme from transcribing HIV genetic material (RNA) into DNA before the virus's genetic code is inserted into an infected cell's genome.

How the intervention might work

Chemoprophylaxis currently is used to protect people from many other infections such as malaria and influenza. Also, current chemoprophylaxis for HIV‐infected patients with advanced immunodeficiency is recommended for the prevention of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, Toxoplasma encephalitis and Mycobacterium avium complex infections. Research has demonstrated the ability of antiretrovirals to reduce the risk of transmission in monkeys of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), a virus commonly used in primate research to model HIV infection in humans (García‐Lerma 2008; Subbarao 2006). Antiretrovirals have also been shown to be effective preventing HIV infection when used in mice that are susceptible to intravaginal infection with HIV (Denton 2008). Theoretically, if replication can be stopped when HIV first enters the body, the virus will not be able to establish a permanent infection (Haase 2010). It is reasonable to assume that PrEP might offer some degree of protection. HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis could be a viable prevention strategy for certain people at high risk of HIV infection, such as commercial sex workers, people in serodiscordant relationships and members of high‐risk groups who choose not to use condoms or for whom consistent condom use has proven difficult (Youle 2003).

Why it is important to do this review

Research into PrEP has stirred international controversy due to various issues of concern (AIDS 2005). One concern is the long‐term side effects of antiretroviral drugs used over many years by uninfected individuals. With TDF, the potential risks include kidney toxicity, loss of bone density, and liver inflammation "flares" in people with hepatitis B (Highleyman 2006). Other concerns regarding PrEP are drug adherence and resistance. Any resistance developed to antiretroviral drugs such as TDF when used first for HIV prevention could limit the usefulness of the drugs later for HIV treatment (Bahuguna 2006). There also are concerns that PrEP will lead to an increase in high‐risk behaviour (AFAO 2005). If PrEP is not completely effective, even a partial reduction in use of safer sex could lead to an increased rate of HIV transmission (Highleyman 2006). Intensive risk reduction counselling could prevent such behavioural disinhibition. This review aims to summarise all the available evidence on the efficacy and safety of oral antiretroviral PrEP for HIV prevention.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of oral antiretroviral chemoprophylaxis in preventing HIV infection in HIV‐uninfected high‐risk individuals.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials that evaluated the effects of antiretroviral chemoprophylaxis in preventing HIV infection in high‐risk individuals.

Types of participants

HIV‐uninfected:

Commercial sex workers

Individuals in serodiscordant relationships

Injection drug users

Men who have sex with men (MSM)

Sexually active young adults

We did not include studies involving pregnant women and the prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission.

Types of interventions

We investigated trials comparing various types of oral PrEP regimen:

TDF only versus placebo or no treatment

TDF + FTC versus placebo or no treatment

TDF only versus TDF + FTC

Any other oral PrEP regimen

We did not include studies involving topical application of antiretrovirals (e.g., vaginal gels).

Types of outcome measures

Primary HIV incidence

Secondary Adherence to PrEP (as measured by the primary studies).

Adverse effects Frequency and type of adverse effects or complications.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

See: HIV/AIDS Cochrane Review Group search strategy.

Identification of studies was done with the assistance of the HIV/AIDS Review Group Trials Search coordinator. We revised the search strategy from the previous version of the review and conducted a comprehensive search to identify all relevant studies regardless of language or publication status (i.e. published, unpublished, in press, and in progress).

We conducted an updated search of the following electronic databases on 20 April 2012:

MEDLINE via PubMed, 1980 to 20 April 2012

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

EMBASE, 1980 to 20 April 2012

The detailed search strategies for each of the databases are documented in Table 3, Table 4, and Table 5, respectively.

1. Search Strategy: PubMed.

| Search | Most Recent Queries |

| #7 | Search #6 NOT pregnan* |

| #6 | Search #1 AND #2 AND #5 |

| #5 | Search #3 OR #4 |

| #4 | Search tenofovir OR TNF OR TDF OR PMPA OR viread OR emtricitabine OR EMC OR truvada OR emtriva OR coviracil |

| #3 | Search pre‐exposure prophylaxis[tiab] OR preexposure prophylaxis[tiab] OR PREP[tiab] OR anti‐retroviral chemoprophylaxis[tiab] OR antiretroviral chemoprophylaxis[tiab] OR chemoprevention[mh] OR chemoprevention[tiab] OR HIV prophylaxis[tiab] |

| #2 | Search (randomised controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomised [tiab] OR placebo [tiab] OR drug therapy [sh] OR randomly [tiab] OR trial [tiab] OR groups [tiab]) NOT (animals [mh] NOT humans [mh]) |

| #1 | Search HIV Infections[MeSH] OR HIV[MeSH] OR HIV[tw] OR hiv‐1*[tw] OR hiv‐2*[tw] OR hiv1[tw] OR hiv2[tw] OR HIV infect*[tw] OR human immunodeficiency virus[tw] OR human immunedeficiency virus[tw] OR human immuno‐deficiency virus[tw] OR human immune‐deficiency virus[tw] OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus[tw])) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immunedeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR ((acquired immun*) AND (deficiency syndrome[tw])) OR "sexually transmitted diseases, viral"[MESH:NoExp] |

2. Search strategy: Cochrane Central register.

| ID | Search |

| #1 | MeSH descriptor HIV Infections explode all trees |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor HIV explode all trees |

| #3 | hiv OR hiv‐1* OR hiv‐2* OR hiv1 OR hiv2 OR HIV INFECT* OR HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS OR HUMAN IMMUNEDEFICIENCY VIRUS OR HUMAN IMMUNE‐DEFICIENCY VIRUS OR HUMAN IMMUNO‐DEFICIENCY VIRUS OR HUMAN IMMUN* DEFICIENCY VIRUS OR ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME |

| #4 | MeSH descriptor Lymphoma, AIDS‐Related, this term only |

| #5 | MeSH descriptor Sexually Transmitted Diseases, Viral, this term only |

| #6 | (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5) |

| #7 | MeSH descriptor Chemoprevention explode all trees |

| #8 | pre‐exposure prophylaxis:ti,ab,kw OR preexposure prophylaxis:ti,ab,w OR PREP:ti,ab,kw OR anti‐retroviral chemoprophylaxis:ti,ab,kw OR antiretroviral chemoprophylaxis:ti,ab,kw OR hiv prophylaxis:ti,ab,kw |

| #9 | (#7 OR #8) |

| #10 | tenofovir OR TNF OR TDF OR PMPA OR viread OR emtricitabine OR EMC OR truvada OR emtriva OR coviracil |

| #11 | (#9 OR #10) |

| #12 | (#6 AND #11) |

3. EMBASE Search strategy.

| No. | Query |

| #8 | #6 NOT pregnan* |

| #7 | #6 NOT pregnan* |

| #6 | #1 AND #2 AND #5 |

| #5 | #3 OR #4 |

| #4 | 'tenofovir'/syn OR tnf OR tdf OR 'pmpa'/syn OR 'viread'/syn OR 'emtricitabine'/syn OR emc OR 'truvada'/syn OR 'emtriva'/syn OR 'coviracil'/syn |

| #3 | 'pre‐exposure prophylaxis' OR 'preexposure prophylaxis' OR prep OR 'anti‐retroviral chemoprophylaxis' OR 'antiretroviral chemoprophylaxis' OR 'chemoprevention'/syn OR 'hiv prophylaxis' OR 'chemoprophylaxis'/syn |

| #2 | random*:ti OR random*:ab OR factorial*:ti OR factorial*:ab OR cross?over*:ti OR cross?over:ab OR crossover*:ti OR crossover*:ab OR placebo*:ti OR placebo*:ab OR (doubl*:ti AND blind*:ti) OR (doubl*:ab AND blind*:ab) OR (singl*:ti AND blind*:ti) OR (singl*:ab AND blind*:ab) OR assign*:ti OR assign*:ab OR volunteer*:ti OR volunteer*:ab OR 'crossover procedure'/de OR 'crossover procedure' OR 'double‐blind procedure'/de OR 'double‐blind procedure' OR 'single‐blind procedure'/de OR 'single‐blind procedure' OR 'randomised controlled trial'/de OR 'randomised controlled trial' OR allocat*:ti OR allocat*:ab |

| #1 | 'human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus infection'/de OR 'human immunodeficiency virus infection' OR 'human immunodeficiency virus'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus'/de OR 'human immunodeficiency virus' OR hiv:ti OR hiv:ab OR 'hiv‐1':ti OR 'hiv‐1':ab OR 'hiv‐2':ti OR 'hiv‐2':ab OR 'human immunodeficiency virus':ti OR 'human immunodeficiency virus':ab OR 'human immuno‐deficiency virus':ti OR 'human immuno‐deficiency virus':ab OR 'human immunedeficiency virus':ti OR 'human immunedeficiency virus':ab OR 'human immune‐deficiency virus':ti OR 'human immune‐deficiency virus':ab OR 'acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome':ab OR 'acquired immunedeficiency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immunedeficiency syndrome':ab OR 'acquired immunodeficiency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immunodeficiency syndrome':ab OR 'acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome':ab |

We also searched the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and ClinicalTrials.gov for ongoing or prospective trials.

Searching other resources

Hand searches of the reference lists of all included studies was performed. We searched for any the on‐going or prospective studies in the WHO Clinical Trials Registry platform and ClinicalTrials.gov. We also searched AEGIS for conference abstracts.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors (CO and OU) independently read the titles, abstracts, and descriptor terms of the search output from the different databases to identify potentially eligible studies. Full text articles were obtained for all citations identified as potentially eligible. Both authors (CO and OU) independently inspected these to establish the relevance of the articles according to the pre‐specified criteria. Studies were reviewed for relevance based on study design, types of participants, interventions, and outcome measures. We gave reasons for excluding potentially relevant studies in an excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data independently using the form we designed and agreed upon. Both authors verified the extracted data. Extracted information included the following.

Study details: citation, study design and setting, time period and source of funding.

Participant details: study population demographics, risk characteristics, population size and attrition rate.

Intervention details: type of drug, comparator, dose, duration and route of administration.

Outcome details: incidence of HIV infection (including type of laboratory tests used to confirm HIV diagnosis before and after administering PrEP), degree of adherence to PrEP and adverse effects.

We summarised the eligible study using the RevMan software.The authors independently extracted the data and entered them into RevMan; all entries were rechecked by both authors, and all disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

CO and OU independently examined the components of each included trial for risk of bias using a standard form. This included information on the sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (participants, personnel and outcome assessor), incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias. The methodological components of the studies were assessed and classified as adequate, inadequate or unclear as per the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Where differences arose, they were resolved by discussions with the third reviewer.

Sequence generation

Adequate: investigators described a random component in the sequence generation process such as the use of random number table, coin tossing, cards or envelope shuffling, etc.

Inadequate: investigators described a non‐random component in the sequence generation process such as the use of odd or even date of birth, algorithm based on the day/date of birth, hospital or clinic record number.

Unclear: insufficient information to permit judgement of the sequence generation process.

Allocation concealment

Adequate: participants and the investigators enrolling participants cannot foresee assignment (e.g. central allocation; or sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes).

Inadequate: participants and investigators enrolling participants can foresee upcoming assignment (e.g. an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); or envelopes were unsealed or nonopaque or not sequentially numbered).

Unclear: insufficient information to permit judgement of the allocation concealment or the method not described.

Blinding

Adequate: blinding of the participants, key study personnel and outcome assessor, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. Or lack of blinding unlikely to introduce bias. No blinding in the situation where non‐blinding is not likely to introduce bias.

Inadequate: no blinding, incomplete blinding and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Unclear: insufficient information to permit judgement of adequacy or otherwise of the blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Adequate: no missing outcome data, reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome, or missing outcome data balanced in number across groups.

Inadequate: reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in number across groups or reasons for missing data.

Unclear: insufficient reporting of attrition or exclusions.

Selective Reporting

Adequate: a protocol is available which clearly states the primary outcome as the same as in the final trial report.

Inadequate: the primary outcome differs between the protocol and final trial report.

Unclear: no trial protocol is available or there is insufficient reporting to determine if selective reporting is present.

Other forms of bias

Adequate: there is no evidence of bias from other sources.

Inadequate: there is potential bias present from other sources (e.g. early stopping of trial, fraudulent activity, extreme baseline imbalance or bias related to specific study design).

Unclear: insufficient information to permit judgement of adequacy or otherwise of other forms of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Outcome measures for dichotomous data (e.g., HIV infection) were calculated as a relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the study authors to provide further information on the results of some of the studies.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In the meta‐analysis, we assessed statistical heterogeneity using the chi square and I square statistics.

Data synthesis

CO and OU independently extracted data from the included studies. The data was were summarised in RevMan 5.1. All of the entries were rechecked by both authors. Where possible, we pooled the results from the included studies in a random effects meta‐analysis, using the Mantel‐Haenzel odds ratio. We performed a subgroup analysis by stratifying our analysis by the type of antiretroviral (TDF versus placebo and TDF‐FTC versus placebo) and also by risk group (heterosexual versus men who have sex with men).

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Results of the search

We identified 12 relevant studies from a total of 2684 titles and abstracts from the search Figure 1. Of the 12 studies, six were ongoing, and six studies provided data for this review (Baeten 2012; Van Damme 2012; Grant 2010; Mutua 2010; Peterson 2007; Thigpen 2012). Two of the studies (Peterson 2007; Van Damme 2012) that provided data for this review were terminated early. We contacted the study authors where necessary for additional information.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Types of participants and settings

The studies involved HIV‐uninfected participants from different risk groups: 2499 men who have sex with men aged 18 years and above (Grant 2010), 936 high risk women age 18 to 35 years (Peterson 2007), 144 high‐risk men and women (67 men who have sex with men, 5 female sex workers and 72 serodiscordant couples: 36 men and 36 women) aged 18 to 49 years (Mutua 2010), 4758 serodiscordant couples (men and women aged 18 to 65 years) (Baeten 2012), 1200 heterosexual men and women aged 18‐39 (Thigpen 2012) and 2120 high‐risk women aged of 18 to 35 years (Van Damme 2012). The participants in Peterson 2007 trial lived in areas within each city that were considered to be at high risk for HIV transmission and were also at high risk of acquiring HIV infection by virtue of having three or more coital acts per week and four or more sexual partners per month.

Mutua 2010 was conducted in Kenya, and Thigpen 2012 was conducted in Botswana. Four of the studies (Baeten 2012 ; Grant 2010; Van Damme 2012 and Peterson 2007) were multinational trials. Baeten 2012 study was conducted in Kenya and Uganda; Grant 2010 study was conducted in Peru, Ecuador, South Africa, Brazil, Thailand and the United States of America; Peterson 2007 study was conducted in Cameroon, Ghana and Nigeria; and Van Damme 2012 study was conducted in Kenya, South Africa, Tanzania and Zimbabwe.

Types of intervention

The interventions tested in the studies were daily oral TDF vs placebo (Peterson 2007), daily oral TDF‐FTC vs placebo (Grant 2010; Van Damme 2012), daily oral TDF‐FTC vs. intermittent oral TDF‐FTC (Mutua 2010), and daily oral TDF‐FTC vs placebo (Thigpen 2012). One of the studies had three arms: TDF, TDF‐FTC and placebo (Baeten 2012).

Types of outcome measures

The outcomes reported in the studies were HIV incidence, safety end points, adverse events, sexual behaviour and adherence.

Risk of bias in included studies

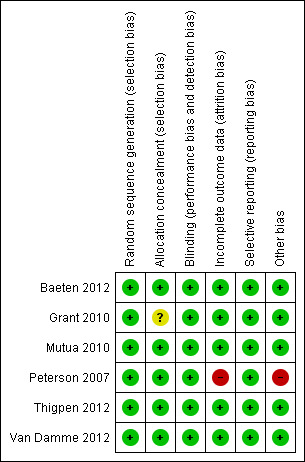

See Risk of Bias graph and Risk of Bias summary tables for the included studies Figure 2; Figure 3. In general, the overall methodological quality of the studies was acceptable. We obtained additional information from conference presentations and by contacting the study authors to be able to make assessments where necessary.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The method of sequence generation was adequate in all the studies. Allocation concealment was also adequate in all the studies except in the Grant 2010 study where we did not find information on allocation concealment.

Blinding

Allocation to the intervention or placebo was blinded to study participants and investigators in all the included studies. However, in Mutua 2010, allocation to daily or intermittent dosing was not blinded.

Incomplete outcome data

There were similar rates of attrition in both the placebo and treatment arms in the studies (Baeten 2012; Van Damme 2012; Grant 2010; Thigpen 2012). In Mutua 2010 there was no loss to follow‐up in any of the study arms. In Peterson 2007 because of irregularities in the performance of the laboratory in Nigeria, data from that site were excluded from the primary safety analyses.

Selective reporting

We compared the reports with the entries into the clinical trial registries and did not find any evidence of selective outcome reporting in any of the studies.

Other potential sources of bias

One of the trial sites for the Peterson 2007 study was closed early because of repeated noncompliance with the trial protocol. We did not explore the potential for publication bias because of the small number of included studies.

Effects of interventions

HIV Incidence

Four studies that compared TDF‐FTC with placebo reported HIV incidence (Baeten 2012; Van Damme 2012; Grant 2010; Thigpen 2012). The meta‐analysis revealed significantly lower HIV incidence in participants who received TDF‐FTC compared to those who received placebo (Mantel‐Haenzael random effects RR (RRMHRE) 0.49; 95% CI 0.28 to 0.85; 8918 participants). There was substantial statistical heterogeneity (I2 =77%, p=0.005) (Figure 4; Analysis 1.1). Two RCTs that compared TDF with placebo reported HIV incidence. The meta‐analysis of these two RCTs (Peterson 2007; Baeten 2012) demonstrated that high‐risk individuals treated with TDF showed lower HIV incidence than those on placebo (RRMHRE 0.33; 95% 0.20 to 0.55; 4027 participants). There was no significant statistical heterogeneity (I2 =0%, p=0.97) (Figure 5; Analysis 2.1).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 TDF+ FTC vs placebo, outcome: 1.1 HIV infection (by risk group).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TDF+ FTC vs placebo, Outcome 1 HIV infection (by risk group).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 TDF vs placebo, outcome: 2.1 HIV infection.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 TDF vs placebo, Outcome 1 HIV infection.

In gender pre‐specified subgroup meta‐analysis (Baeten 2012; Thigpen 2012), TDF‐FTC was statistically significantly more efficacious than placebo in reducing HIV infection in both men and women. However, TDF‐FTC was more efficacious in men (RRMHRE 0.17; 95% CI 0.07 to 0.41) than in women (RRMHRE 0.40; 95% CI 0.20 to 0.71) (Figure 6). However, this gender differential in effectiveness of TDF‐FTC did not reach statistical significant level (p‐value for interaction = 0.10).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 TDF+ FTC vs placebo, outcome: 1.2 HIV infection (by gender).

A comparison of TDF‐FTC versus TDF alone did not show any statistically significant difference in the incidence of HIV infection (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.36 to 1.47).

Adherence

In Baeten 2012, adherence, which was measured by monthly pill count of unused study product, was similar (97%) in all the study arms. In Van Damme 2012, reported adherence was 95% in both study arms; adherence based on pills count was 86% in the TDF‐FTC group and 89% in the placebo group. However, measurements of drug levels in study volunteers’ blood was significantly lower. Among participants in the TDF‐FTC group who remained uninfected, 38% had detectable drug levels in their blood. Among those who were infected, detectable drug levels was found in only 21%. The reported adherence in Grant 2010 was found to be similar between the FTC‐TDF and placebo arm. However, the exposure to TDF‐FTC measured objectively in the intervention arm was substantially lower than reported. TDF‐FTC was detected in 51% of participants who remained HIV negative and only in 9% of those who became infected. There was a similar pattern of adherence in the group receiving a daily regimen of TDF‐FTC and those receiving TDF‐FTC intermittently in Mutua 2010. Thigpen 2012, also reported similar levels of adherence between the TDF‐FTC and placebo group (84.1% and 83.7 percent respectively). Peterson 2007 did not provide details on the rates of adherence in each of the two study arms

Sexual behaviour (post hoc)

Baeten 2012 and Grant 2010 reported similar sexual practices across the groups. There were no significant differences in the number of subjects with syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia, genital warts or genital ulcers (Grant 2010). In Peterson 2007 during screening, participants reported an average of 12 coital acts per week with an average of 21 sexual partners in the previous 30 days. During follow‐up, participants reported an average of 15 coital acts per week, with an average of 14 sexual partners in the previous 30 days. Self‐reported condom use increased from 52% at screening to an average of 92% at the follow‐up period. The authors did not provide details on the sexual behaviour in each of the study arms.

Adverse Events

Baeten 2012; Grant 2010; and Thigpen 2012 reported similar rates of serious adverse events between the TDF‐FTC group and placebo group (RRMHRE 1.00; 95% CI 0.83 to 1.19; 6862 participants) Figure 7; Analysis 1.3. Also, Baeten 2012 did not find any significant difference in the rates of adverse events between the TDF group and placebo group (RRMHRE 1.03; 95% CI 0.79 to 1.33; 3168 participants ) (Figure 8; Analysis 2.2). A comparison of TDF‐FTC versus TDF alone did not show any statistically significant difference in the incidence of severe adverse events (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.77 to 1.29).

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 TDF‐FTC vs placebo, outcome: 2.2 Adverse events.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TDF+ FTC vs placebo, Outcome 3 Serious adverse events.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 TDF vs placebo, outcome: 1.2 Adverse events.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 TDF vs placebo, Outcome 2 Serious adverse events.

In Grant 2010 a small number of participants in the TDF‐FTC group developed renal insufficiency which was reversible on discontinuation of the drug. Van Damme 2012 found mild‐to‐moderate increases in alanine amino transferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were more common in the TDF‐FTC group. However, only the difference in ALT measurements was statistically significant. There were no differences in creatinine or phosphorous levels were seen between the two study groups.

Peterson 2007 reported 22 serious adverse events (9 in the TDF group and 13 in the placebo group) in 17 participants. None of the serious adverse events were considered related to study drug.

Mutua 2010 did not find any drug‐related severe adverse events and no significant renal dysfunction. Among those on the daily regimen, there was a total of 203 adverse events out of which 76% are judged to be unrelated to the study medication. A similar pattern was observed among those on the intermittent regimen with a total of 152 adverse events out of which 84% are unrelated to the study medication.

All the studies reported significantly higher rates of nausea and vomiting in the TDF‐FTC group compared to placebo.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Overall, results from four trials (Baeten 2012; Van Damme 2012; Grant 2010; Thigpen 2012) that compared TDF‐FTC versus placebo shows a reduction in the risk of acquiring HIV infection by about 51%. Of these 4 trials, Van Damme 2012 failed to demonstrate a reduction in the risk of HIV infection with the use of TDF‐FTC, possibly due to inadequate adherence to the trial medications by the participants. In the other two trials (Peterson 2007; Baeten 2012) that compared TDF only versus placebo, there was a significant reduction in the risk of acquiring HIV infection by about 67%.

The rate of adherence was found to be similar between the TDF‐FTC vs. placebo arm and TDF vs. placebo. However, measurements of drug levels in some study volunteers suggested that the level of adherence was lower that reported by the participants. Sexual behaviour was similar across the study arms, and there was no evidence of potential risk compensation or behavioural disinhibition.The studies also reported similar rates of serious adverse events. However, a small number of participants in the TDF‐FTC group were found to have developed renal insufficiency which was reversible on discontinuation of the drug. This raises some long term safety concerns.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We included all studies that met the inclusion criteria for this review. The trials included participants from different risk groups (men who have sex with men, serodiscordant couples, female sex workers and other high‐risk men and women). None of the completed studies included injection drug users. The studies were conducted in different settings: including high, middle and low‐income countries. Therefore the findings from this review are applicable to various settings.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE methodology, and the basis for the judgements is presented in two 'Summary of findings' tables (Table 1; Table 2). The overall quality of evidence on the effectiveness of PrEP for preventing HIV in high‐risk individuals can be described as moderate quality. We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level on account of instability of results since there are fewer than 200 events per arm.

Potential biases in the review process

We conducted a comprehensive search to ensure that all relevant completed or ongoing studies were identified. There was no language restriction. We also reduced potential bias in the conduct of this review by having two of the authors independently scan through the search output, extract data, and assess the methodological quality of each study.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Findings from this review suggests that the use of oral TDF alone or a combination of TDF and FTC reduces the risk of acquiring HIV in high risk individuals. The use of PrEP with other existing HIV prevention strategies will provide the greatest protection to individuals at risk.

Many studies have examined the cost–effectiveness of PrEP. A mathematical modelling study on the cost‐effectiveness of PrEP concluded that PrEP could prevent a significant number of infections among high‐risk men who have sex with men and be cost effective (Desai 2008). Another mathematical modelling study that evaluated the cost‐effectiveness of PrEP in South Africa showed that the cost–effectiveness of PrEP relative to ART decreases rapidly as ART coverage increases beyond three times its coverage in 2010 (Pretorius 2010).

Implications for research.

In the search for highly reliable HIV prevention strategies, it is important to determine how PrEP can best be combined with existing programs, as no strategy is likely to be 100% effective. The efficacy of PrEP for prevention of HIV in high‐risk individual has been demonstrated, but additional research is needed to answer the following questions: What would be the best method for administering PrEP: daily versus intermittent dosing? How would adherence affect the efficacy of PrEP, and what are the determinants of PrEP adherence in people at high risk of infection? What will be the effect of PrEP on resistance in individuals who become infected and the possible transmission of drug‐resistant virus? What are the long term effects of using PrEP? There is also a need for research on the feasibility of implementing PrEP into different contexts, including resource‐constrained settings where ART treatment coverage is inadequate. Another important issue that will need to be addressed will be the long‐term cost effectiveness of PrEP.

Feedback

Feedback on risk of bias assessment, 22 October 2012

Summary

Name: Kenneth F. Schulz, PhD, MBA; Lut Van Damme, MD, PhD; Douglas J. Taylor, PhD Email Address: KSchulz@FHI360.org

Affiliation: FHI 360

Role: Distinguished Scientist; Senior Scientist; Senior Scientist

Comment: In this review of “Antiretroviral pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for preventing HIV in high‐risk individuals,” we disagree with the review authors’ risk of bias judgment on one item for the Van Damme 2011 trial. Please note, the trial report has now been published in the New England Journal of Medicine.[1] As for our background, Dr. Schulz is a coauthor of The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials,[2] Dr. Van Damme is the first author and scientific leader of Van Damme 2011, and Dr. Taylor is the lead statistician of Van Damme 2011.

In figure 3 of the Cochrane Review, the review authors judged the Van Damme 2011 trial to be at “High risk of bias” in the “Other bias” category presumably because it “. . . was stopped early after an interim analysis showed that the trial was unlikely to demonstrate a protective effect of oral TDF‐FTC.” We do not understand how such a judgment could ever be made on a well‐designed and well‐conducted randomized trial simply because it was stopped early by a data monitoring committee, even before the recent update to the Cochrane Handbook in 2011. However, that update squelched any doubt. The 2011 version clearly states under “Reconsideration of eligible issues for ‘other bias’, including early stopping of a trial” that “The guidance for the ‘other bias’ domain has been edited to strengthen the guidance that additional items should be used only exceptionally, and that these items should relate to issues that may lead directly to bias. In particular, the mention of early stopping of a trial has been removed, because (i) simulation evidence suggests that inclusion of stopped early trials in meta‐analyses will not lead to substantial bias, and (ii) exclusion of stopped early trials has the potential to bias meta‐analyses towards the null (as well as leading to loss of precision).”

Clearly, we believe the Van Damme 2011 trial should not be judged as “high risk of bias” on this item. We suggest the reviewers correct this oversight and update the review.

The review authors also noted that only two studies were terminated early, Peterson 2007 and Van Damme 2011. However, at least two other trials in their review terminated early, in whole or in part, and the authors did not note those terminations. In Thigpen 2011, the investigators decided to proceed to orderly closure based on low retention. In Baeten 2011, the investigators changed its design after the July 2011 meeting of their DSMB because their board recommended that the results of the study be publicly reported and the placebo treatment discontinued, because predetermined stopping rules were met with the demonstration of HIV‐1 protection from PrEP. These results were published in the same 2012 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine as the Van Damme 2011 trial.

Kenneth F. Schulz, PhD, MBA; Distinguished Scientist, FHI 360

Lut Van Damme, MD, PhD; Senior Scientist, FHI 360

Douglas J. Taylor, PhD; Senior Scientist, FHI 360

References

1. Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. The New England journal of medicine 2012;367:411‐22.

2. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928.

I have modified the conflict of interest statement below to declare my interests:

I certify that I have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with a financial interest in the subject matter of my feedback, except that all three of the authors of this comment are employed by FHI 360, the organization that conducted and published the research paper discussed in this Comment.

Reply

Dear Dr. Schulz, Dr. Van Damme and Dr. Taylor,

Thank you very much for bringing this to our attention. We used the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (in the current version of the printed Cochrane Handbook) which mentions early stoppage of trials as other sources of bias (Cochrane Handbook Chapter 8, page 201). However, you are correct that there is a revised version of Chapter 8 in the online version of the Handbook, and that the mention of early stopping of a trial has been removed. We agree with your comments and have made the necessary changes in the risk of bias assessment. Thank you.

Charles Okwundu

Contributors

Charles I. Okwundu, Olalekan Uthman

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 November 2012 | Feedback has been incorporated | Added feedback, and response to feedback. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2008 Review first published: Issue 1, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 June 2012 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | New citation; conclusions changed. |

| 15 June 2012 | New search has been performed | New searches; review completely updated. |

Acknowledgements

Charles I. Okwundu was awarded a Reviews for Africa Programme Fellowship (www.mrc.ac.za/cochrane/rap.htm) funded by the Nuffield Commonwealth Programme through The Nuffield Foundation.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. TDF+ FTC vs placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 HIV infection (by risk group) | 4 | 8918 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.28, 0.85] |

| 1.1 Heterosexual group | 3 | 6419 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.19, 1.10] |

| 1.2 MSM group | 1 | 2499 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.38, 0.84] |

| 2 HIV infection (by gender) | 2 | 4354 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.19, 0.50] |

| 2.1 Women | 2 | 1729 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.23, 0.71] |

| 2.2 Men | 2 | 2625 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.17 [0.07, 0.41] |

| 3 Serious adverse events | 3 | 6862 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.83, 1.19] |

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TDF+ FTC vs placebo, Outcome 2 HIV infection (by gender).

Comparison 2. TDF vs placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 HIV infection | 2 | 4027 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.20, 0.55] |

| 2 Serious adverse events | 1 | 3168 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.79, 1.33] |

Comparison 3. TDF‐FTC vs TDF alone.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 HIV infection | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Serious adverse events | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 TDF‐FTC vs TDF alone, Outcome 1 HIV infection.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 TDF‐FTC vs TDF alone, Outcome 2 Serious adverse events.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Baeten 2012.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | HIV‐1 uninfected individuals within HIV‐1 discordant partnerships (men and women age 18 Years to 69 Years) Inclusion Criteria for HIV‐1 uninfected partner:

Exclusion Criteria for HIV‐1 uninfected partner:

Inclusion Criteria for HIV‐1 infected partner:

Exclusion Criteria for HIV‐1 infected partner:

|

|

| Interventions | Daily Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate 300 mg vs. placebo Daily Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate 300 mg + Emtricitabine 200 mg vs. placebo | |

| Outcomes |

Primary Outcome Measures:

Secondary Outcome Measures:

|

|

| Notes | The study was conducted in Kenya and Uganda | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | HIV‐1 uninfected partners were assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to one of three study arms: once‐daily TDF, TDF‐FTC, or placebo, using a fixed‐size block randomisation, stratified by site. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A telephonic interactive voice response system was used to assign study drug kits. The investigators, except for statistical staff at the central coordinating center, remained unaware of the randomisation assignments |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | There was blinding of participants and investigators. Active and placebo TDF were indistinguishable, as were active and placebo TDF‐FTC |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Retention rates were similar in the different study arms |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective outcome reporting |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other potential sources of bias identified |

Grant 2010.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | Men who have sex with men Inclusion Criteria:

Inclusion Criteria for Open‐Label Extension:

Exclusion Criteria:

Exclusion Criteria for Open‐Label Extension: ‐ Site leadership believes participant will have difficulty completing requirements |

|

| Interventions | Daily Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate 300 mg + Emtricitabine 200 mg vs. placebo | |

| Outcomes |

Primary Outcome:

Secondary Outcome Measures:

|

|

| Notes | This is a multinational trial conducted in Peru, Ecuador, South Africa, Brazil, Thailand and the United States | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Subject codes were randomly assigned in blocks of 10, stratified according to site |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | The method used for allocation concealment is not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | There was blinding of participants and investigators |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Incomplete outcome data were properly addressed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective outcome reporting |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other potential sources of bias identified |

Mutua 2010.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | HIV negative men and women aged 18 to 49 Years Inclusion Criteria:

Exclusion Criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Daily vs intermittent Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate plus Emtricitabine (FTC/TDF) | |

| Outcomes |

Primary Outcome Measures:

Secondary Outcome Measures:

|

|

| Notes | The study was conducted in Kenya | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | A random allocation sequence was generated by an external data coordinating centre. Investigators at the study sites enrolled participants via an electronic enrolment system where allocation codes were assigned consecutively to eligible volunteers at the time of first dispensation of study drug. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation was done by an external centre. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | There was blinding of participants and investigators to the study medications. However, the allocation to daily or intermittent dosing was not blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | There was no loss to follow up. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective outcome reporting |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other potential source of bias |

Peterson 2007.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | Women aged 18 to 35 years Inclusion Criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Daily 300 mg tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus placebo | |

| Outcomes | Primary Outcome Measures:

|

|

| Notes | This is a multinational study conducted in Ghana, Cameroon and Nigeria | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | A random allocation sequence was generated using a computer random number generator. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation was concealed by the use of sealed opaque envelopes. The randomisation envelopes were maintained in a secure office. They were not available to the study counsellors until the immediate moment of randomisation. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Placebo tablets were made to match the TDF tablets, and contained denatonium benzoate to provide a bitter taste to resemble the active tablets. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Some data were discarded (Nigeria‐safety data) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective outcome reporting |

| Other bias | High risk | There was premature stoppage of the trial at the Cameroon and Nigeria sites. |

Thigpen 2012.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | 1200 HIV uninfected, sexually active healthy male and female volunteers Inclusion Criteria:

Exclusion Criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate 300 mg + Emtricitabine 200 mg daily | |

| Outcomes |

Primary Outcome Measures:

Secondary Outcome Measures:

|

|

| Notes | The study was conducted in Botswana | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants were randomised in a 1:1 ratio using random, permuted blocks of six, stratified by site and gender |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | The randomisation was done randomly centrally |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Neither researchers nor participants knew an individual’s group assignment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Similar rates of attrition in both groups and all participants were accounted for |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective outcome reporting |

| Other bias | Low risk | We did not identify any other potential source of bias |

Van Damme 2012.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | HIV‐antibody‐negative women between the ages of 18‐35 who were at risk of HIV acquisition through sexual intercourse Inclusion Criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Daily Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate 300 mg + Emtricitabine 200 mg vs placebo | |

| Outcomes |

Primary Outcome Measures:

Secondary Outcome Measures:

|

|

| Notes | The study was conducted in Kenya, South Africa, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | The authors described the use of block randomization |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Envelopes were used to conceal the assignment of participants |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | There was blinding of participants and investigators |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Similar rates of attrition in both groups and all participants were accounted for |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective outcome reporting |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other potential sources of bias identified |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Brooks 2003 | Phase І trial with no control group |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Chirenje 2012.

| Trial name or title | Safety and Effectiveness of Tenofovir 1% Gel, Tenofovir Disproxil Fumarate, and Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate Tablets in Preventing HIV in Women. MTN‐003 (VOICE). |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Sexually active women in South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe Inclusion Criteria:

Exclusion Criteria:

|

| Interventions | 200 mg/300 mg tablet TDF‐FTC versus placebo 300 mg tablet TDF versus placebo |

| Outcomes | Primary Outcome Measures:

Secondary Outcome Measures:

|

| Starting date | September 2009 |

| Contact information | Zvavahera M. Chirenje, MD, FRCOG. UZ‐UCSF Collaborative Research Programme. Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH. University of Washington, Division of Allergy and Infectious Disease |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: |

Choopanya 2010.

| Trial name or title | Bangkok Tenofovir Study |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Injection drug users aged between 20 and 60 (both gender) Inclusion Criteria:

Exclusion Criteria:

|

| Interventions | Oral tenofovir 300 mg versus placebo |

| Outcomes |

Primary Outcome Measures:

Secondary Outcome Measures:

|

| Starting date | June 2005 |

| Contact information | Principal Investigator: Kachit Choopanya, Bangkok Tenofovir Study Group. Study director: Michael T Martin, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| Notes | Study location: Bangkok |

Grant 2012.

| Trial name or title | Use of Emtricitabine and Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate for Pre‐Exposure Prophylaxis (ADAPT) |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial (open label) |

| Participants | Men and women aged 18 years and older Inclusion Criteria:

Inclusion Criteria for Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM):

Inclusion Criteria for Women Who Have Sex With Men (WSM):

Exclusion Criteria:

|

| Interventions | Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (FTC/TDF): daily, time‐based, and event‐based dosing |

| Outcomes |

Primary Outcome Measures:

Secondary Outcome Measures:

|

| Starting date | September 2012 |

| Contact information | Study chair: Robert M. Grant, MD, MPH. University of California, San Francisco |

| Notes | Study location: South Africa and Thailand |

Molina 2012.

| Trial name or title | On Demand Antiretroviral Pre‐exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection in Men Who Have Sex With Men (IPERGAY) |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Men who have sex with men aged 18 years and older Inclusion Criteria:

Exclusion Criteria:

|

| Interventions | TDF‐FTC versus placebo (taken at the time of intercourse) |

| Outcomes | Primary Outcome Measures:

Secondary Outcome Measures:

|

| Starting date | January 2012 |

| Contact information | Jean‐Michel MOLINA, Hôpital Saint‐Louis Paris FRANCE |

| Notes | Study location: France |

NIAID 2012.

| Trial name or title | Evaluating the Safety and Tolerability of Antiretroviral Drug Regimens Used as Pre‐Exposure Prophylaxis to Prevent HIV Infection in Men Who Have Sex With Men (HPTN 069) |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Men who have sex with men, 18 years and older Inclusion Criteria:

Exclusion Criteria:

|

| Interventions | Four ARV regimens: maraviroc (MVC), MVC plus emtricitabine, MVC plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), and TDF plus FTC. |

| Outcomes |

Primary Outcome Measures:

Secondary Outcome Measures:

|

| Starting date | 2012 |

| Contact information | National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) |

| Notes | Study location: USA |

Paxton 2007.

| Trial name or title | Botswana TDF/FTC Oral HIV Prophylaxis Trial |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Sexually‐active men and women aged 18 to 29 years Inclusion Criteria:

Exclusion Criteria:

|

| Interventions | Daily Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate 300 mg + Emtricitabine 200 mg daily versus placebo |

| Outcomes |

Primary Outcome Measures:

Secondary Outcome Measures:Secondary:

|

| Starting date | March 2007 |

| Contact information | Lynn A Paxton, MD, MPH. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| Notes | Study location: Botswana |

Differences between protocol and review

The following aspects of the review were not in the protocol: abstract, plain language summary, risk of bias table, results, characteristics of included studies, search strategies, discussion, and authors' conclusion.

Contributions of authors

Charles Okwundu conceptualised the protocol. Charles Okwundu and Olalekan Uthman reviewed search outputs, selected studies for inclusion, located copies of study reports, and extracted data. Charles Okwundu wrote the review. Olalekan Uthman and Christy Okoromah provided input into the draft review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Centre for Evidence‐Based Health Care, Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

External sources

-

Review for Africa Programme, South Africa.

Charles I. Okwundu and Olalekan Uthman were awarded a Reviews for Africa Programme Fellowship (www.mrc.ac.za/cochrane/rap.htm), funded by a grant from the Nuffield Commonwealth Programme, through the Nuffield Foundation

The Nuffield Commonwealth Foundation, UK.

The South African Cochrane Center, South Africa.

Declarations of interest

None known

Edited (no change to conclusions), comment added to review

References

References to studies included in this review

Baeten 2012 {published and unpublished data}

- Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. The New England Journal of Medicine July 2012;367(5):399‐410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Grant 2010 {published data only}

- Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al . Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. The New England Journal of Medicine December 2010;363(27):2587‐99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mutua 2010 {published and unpublished data}

- Mutua G, Sanders EJ, Kamali E, Kibengo F, Mugo P, Anzala O et a. Safety and adherence to intermittent Emtricitabine/Tenofovirfor HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in Kenya and Uganda. AIDS 2010: XVIII International AIDS Conference, Vienna, Austria. 2010:Abstract no. MOPE0369 .

Peterson 2007 {published data only}

- Peterson L, Taylor D, Roddy R, Belai G, Phillips P, Nanda K, et al. Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate for Preventionof HIV Infection in Women: A Phase 2, Double‐Blind, randomized, Placebo‐Controlled Trial. Plos CLINICAL TRIALS May 25, 2007;2 (5):e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thigpen 2012 {published and unpublished data}

- Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. The New England Journal of Medicine July 2012;367(5):423‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Van Damme 2012 {published and unpublished data}

- Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Kapiga S, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. The New England Journal of Medicine July 2012;367(5):411‐22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Brooks 2003 {published data only}

- Brooks JJ, Scott B, Estelle P, Linda A, Charles R, Craig H, et al. A phase I/II study of nevirapine for pre‐exposure prophylaxis of HIV‐1 transmission in uninfected subjects at high risk. AIDS March 2003;17(4):547‐553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

Chirenje 2012 {unpublished data only}

- Chirenje ZM, Marrazzo J. Safety and Effectiveness of Tenofovir 1% Gel, Tenofovir Disproxil Fumarate, and Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate Tablets in Preventing HIV in Women. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00705679.

Choopanya 2010 {unpublished data only}

- Choopanya K, Martin MT, Paxton Lynn. Bangkok Tenofovir Study. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00119106 (Accessed 20 April 2012).

Grant 2012 {unpublished data only}

- Grant RM. Use of Emtricitabine and Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate for Pre‐Exposure Prophylaxis (ADAPT). http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01327651 (Accessed 20 April 2012).

Molina 2012 {published data only}

- Molina J. On Demand Antiretroviral Pre‐exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection in Men Who Have Sex With Men (IPERGAY). http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01473472 (Accessed 20 April 2012). [NCT01473472]

NIAID 2012 {unpublished data only}

- NIAID. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01505114?term=HPTN+069&rank=1 [Evaluating the Safety and Tolerability of Antiretroviral Drug Regimens Used as Pre‐Exposure Prophylaxis to Prevent HIV Infection in Men Who Have Sex With Men (HPTN 069)]. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01505114 (Accessed 20 April 2012).

Paxton 2007 {unpublished data only}

- Paxton LA. Botswana TDF/FTC Oral HIV Prophylaxis Trial. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00448669 (Accessed 20 April 2012).

Additional references

Abdool Karim 2010

- Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science Sep. 2010;3:1168‐74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

AFAO 2005

- Australian federation of AIDS organization Inc. AFAO National forumon Prepexposure prophylaxis for HIV(PrEP): final report. A summary of the outcomes of the National forum held at Dockside, Cockle Bay on the 16th June, 2005.

AIDS 2005

- AIDS News Release. Prevention in a tablet. www.ippf.org/NR/rdonlyres/80E7C1E6‐2A56‐4E18‐ACEE‐2ED784FD1FE5/0/Issue4_11_05.pdf (accessed 14 September 2007).

Anglemyer 2011

- Anglemyer A, Rutherford GW, Baggaley RC, Egger M, Siegfried N. Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of HIV transmission in HIV‐discordant couples. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, (8):CD009153. [PUBMED: 21833973] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bahuguna 2006

- Bahuguna NJ. Putting women in charge. www.boloji.com/wfs5/wfs672.htm (accessed 14 September 2007).

Cohen 2011

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N. Prevention of HIV‐1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England Journal of Medicine August 2011;365(6):493‐505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Denton 2008

- Denton PW, Estes JD, Sun Z, Othieno FA, Wei BL, Wege AK, et al. Antiretroviral pre‐exposure prophylaxis prevents vaginal transmission of HIV‐1 in humanized BLT mice. PLoS Medicine January 2008;5(1):e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Derdelinckx 2006

- Derdelinckx I, Wainberg MA, Lange JM, Hill A, Halima Y, Boucher CA. Criteria for drugs used in pre‐exposure prophylaxis trials against HIV infection. PLoS Medicine November 2006;3(11):e454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Desai 2008

- Desai K, Sansom SL, Ackers ML, Stewart SR, Hall HI, Hu DJ, et al. Modeling the impact of HIV chemoprophylaxis strategies among men who have sex with men in the United States: HIV infections prevented and cost‐effectiveness. AIDS September 2008;22(14):1829‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Donnell 2010

- Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, Thomas KK, Stevens W, Cohen CR, et al. Heterosexual HIV‐1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. The Lancet June 2010;375(9731):2092‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

García‐Lerma 2008

- García‐Lerma JG, Otten RA, Qari SH, Jackson E, Cong ME, Masciotra S, Luo W, et al. Prevention of rectal SHIV transmission in macaques by daily or intermittent prophylaxis withemtricitabine and tenofovir. PLoS Medicine February 2008;5(2):e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guay 1999

- Guay L, Musoke P, Fleming T, Bagenda D, Allen M, Nakabiito C, et al. Intrapartum and neonatal single‐dose nevirapine compared with zidovudine for prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV‐1 in Kampala, Uganda: HIVNET 012 randomized trial. Lancet 1999;354:795‐802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Haase 2010

- Haase AT. Targeting early infection to prevent HIV‐1mucosal transmission. Nature March 2010;11(464(7286)):217‐23.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Highleyman 2006

- Highleyman L. Pre‐exposure prophylaxis: a new focus for HIV prevention. AIDS 2006 16th International AIDS Conference; 2006 Aug 13‐18; Toronto,Canada. 2006.

Pretorius 2010

- Pretorius C, Stover J, Bollinger L, Bacaer N, Williams B. Evaluating the cost‐effectiveness of pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and its impact on HIV‐1 transmission in South Africa. PloS One5 2010;5(11):E13646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sharifi‐Azad 2011

- Sharifi‐Azad J, Rizzolo D. Postexposure prophylaxis for HIV: pivotal intervention for those at risk. JAAPA August 2011;24(8):22‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Siegfried 2011

- Siegfried N, Merwe L, Brocklehurst P, Sint TT. Antiretrovirals for reducing the risk of mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, (7):CD003510. [PUBMED: 21735394] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Smith 2005

- Smith DK, Grohskopf LA, Black RJ. US Department of Health and Human Services. Antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection‐drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV in the United States: recommendations from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. . MMWR Recomm Rep 2005;54(RR‐2):1‐20.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Subbarao 2006

- Subbarao S, Otten RA, Ramos A, Kim C, Jackson E, Monsour M, et al. Chemoprophylaxis with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate provided partial protection against infection with simian human immunodeficiency virus in macaques given multiple virus challenges. Journal of Infectious Diseases October 2006;194(7):874‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 2011

- WHO. GLOBAL HIV/AIDS RESPONSE, Epidemic update and health sector progress towards Universal Access. Progress Report 2011.

Youle 2003

- Youle M, Wainberg M. Pre‐exposure chemoprophylaxis (PREP) as an HIV prevention strategy. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care 2003;2(3):102‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Young 2007

- Young TN, Arens FJ, Kennedy GE, Laurie JW, Rutherford G. Antiretroviral post‐exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for occupational HIV exposure. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, (1):CD002835. [PUBMED: 17253483] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]