Abstract

This study involved designing, synthesizing, and evaluating the protective potential of compounds on microglial cells (BV-2 cells) and neurons (SH-SY5Y cells) against cell death induced by Aβ1–42. It aimed to identify biologically specific activities associated with anti-Aβ aggregation and understand their role in oxidative stress initiation and modulation of proinflammatory cytokine expression. Actively designed compounds CE5, CA5, PE5, and PA5 showed protective effects on BV-2 and SH-SY5Y cells, with cell viability ranging from 60.78 ± 2.32% to 75.38 ± 2.75% for BV-2 cells and 87.21% ± 1.76% to 91.55% ± 1.78% for SH-SY5Y cells. The transformation from ester in CE5 to amide in CA5 resulted in significant antioxidant properties. Molecular docking studies revealed strong binding of CE5 to critical Aβ aggregation regions, disrupting both intra- and intermolecular formations. TEM assessment supported CE5's anti-Aβ aggregation efficacy. Structural variations in PE5 and PA5 had diverse effects on IL-1β and IL-6, suggesting further specificity studies for Alzheimer's disease. Log P values suggested potential blood–brain barrier permeation for CE5 and CA5, indicating suitability for CNS drug development. In silico ADMET and toxicological screening revealed that CE5, PA5, and PE5 have favorable safety profiles, while CA5 shows a propensity for hepatotoxicity. According to this prediction, coumarin triazolyl derivatives are likely to exhibit mutagenicity. Nevertheless, CE5 and CA5 emerge as promising lead compounds for Alzheimer's therapeutic intervention, with further insights expected from subsequent in vivo studies.

CE5, a promising lead compound for Alzheimer's therapy, targets anti-amyloid beta aggregation, oxidative stress reduction, and inflammation modulation mechanisms.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is not only a significant cause of dementia in elderly adults, but it also has a profound impact on the lives of individuals, their families, and society.1 This degenerative neurological disorder progressively impairs the patient's memory system, leading to cognitive decline and memory loss.2,3 AD is defined by two specific neuropathological characteristics: the development of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau proteins and insoluble amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques, which accumulate abundantly outside brain cells.4 Aβ plaques and tangles disrupt the normal functioning of neurons, leading to the cognitive decline and memory loss seen in AD patients.5

The Aβ plaques arise from the aggregation of Aβ peptides, consisting of 40 or 42 amino acid residues.6 Aβ peptides are derived from a transmembrane protein called amyloid-β precursor protein (APP). APP can undergo proteolysis through two distinct mechanisms, namely the amyloidogenic and non-amyloidogenic pathways.4 In the non-amyloidogenic process, α-secretase first cleaves APP, which is then further cleaved by γ-secretase to produce P3 peptides. Alternatively, APP can undergo the amyloidogenic proteolysis route, where it is sequentially cleaved by β-secretase and γ-secretase enzymes, resulting in the formation of Aβ peptides.7,8

After the generation of Aβ peptides, they continue to aggregate and form several types of assemblies, ranging from small oligomers such as dimers, trimers, tetramers, and pentamers to intermediate-sized oligomers like hexamers and dodecamers, and finally to protofibrils and amyloid fibrils.9,10 The insoluble Aβ fibrils undergo further aggregation to create Aβ plaques. These plaques are one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease and are believed to play a significant role in the pathogenesis of the disease. They accumulate in the brain and disrupt normal neuronal function, leading to cognitive decline and other symptoms associated with Alzheimer's.9 Additionally, the accumulation of Aβ assemblies has been linked to chronic inflammation and oxidative stress in the brain, further exacerbating the neurodegenerative process.11

Oxidative stress, characterized by an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and the cellular antioxidant defense system, has been closely linked to Aβ aggregation.12 The process of Aβ aggregation can induce oxidative stress, as toxic oligomers generated during this aggregation process contribute to the production of ROS. In turn, the heightened oxidative stress environment further promotes the aggregation of Aβ, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that augments the neurodegenerative cascade.13 Additionally, the association between Aβ aggregation and neuroinflammation further highlights the complexity of neurodegenerative processes. Microglia, the resident immune cells in the brain, become activated in response to Aβ accumulation.3,14 This activation triggers the release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, amplifying the neuroinflammatory response.15–17 The persistent nature of neuroinflammation continues Aβ aggregation and strengthens oxidative stress, forming a self-sustaining cycle that drives neurodegeneration. Searching for Aβ-based therapeutics for AD is a substantial and arduous challenge.18 Several research teams have developed compounds designed to impede critical stages of the amyloidogenic pathway. One specific approach involves targeting the inhibition of Aβ aggregation using small molecules.19–21

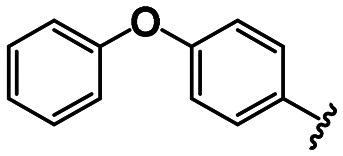

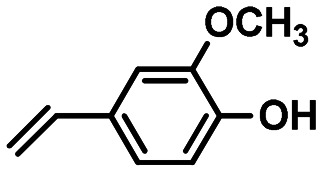

A notable small molecule featuring the coumarin ring has been designed to address various targets contributing to AD. They involve the inhibition of cholinesterase enzymes,22,23 disruption of different types of Aβ during the aggregation process,24 or perturbing both of those targets.25,26 Coumarin is a naturally occurring bioactive neoflavonoid with a broad spectrum of activities, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.27 Several developed coumarin derivatives have demonstrated neuroprotective potential through the inhibition of MAO-B and cholinesterase enzymes as well as the inhibition of Aβ assemblies during the aggregation process.28–33 Furthermore, evidence indicates that coumarin-associated derivatives can permeate the blood–brain barrier (BBB).34 Hence, it is an interesting scaffold for anti-neurodegenerative agent development. Recently, another class of compounds known as phenoxyindole derivatives has been identified for their potent abilities to inhibit Aβ aggregation, demonstrate strong antioxidant properties, and exhibit neuroprotective effects.35,36 Additionally, the NSAID drug fenoprofen, which contains a phenoxyphenyl group, has been found to decrease the formation of Aβ1–42via γ-secretase inhibition.37 Building on this rationale, we have designed two novel derivatives using a similar approach. These derivatives incorporate either a coumarin or a phenoxyphenyl group derived from phenoxyindole, connected to similarly substituted aromatic compounds through a triazolyl moiety. Fig. 1 illustrates our designed compounds.

Fig. 1. The designed structures of coumarin and phenoxyphenyl derivatives.

BV-2 cells will be utilized to examine the inflammatory reactions induced by Aβ aggregation to comprehend the designed compounds' mechanism of action. BV-2 cells are commonly employed to represent native microglia and in vitro models for neurological diseases.38,39 They provide a valuable tool for studying the cellular and molecular responses to Aβ aggregation, as they exhibit similar characteristics and responses to native microglia. Employing BV-2 cells will enable us to understand the inflammatory mechanisms triggered by Aβ aggregation and potentially identify novel therapeutic targets for AD.40 In this study, we aim to design and synthesize derivatives involving coumarin triazolyl and phenoxyphenyl triazolyl. Our investigation focuses on their neuroprotective properties, particularly their ability to inhibit the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and proinflammatory cytokines induced by Aβ aggregation.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Synthesis

Copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition, commonly known as click chemistry,41,42 synthesizes novel triazolyl compounds. This reaction facilitates covalent connections between diverse aromatic derivatives and coumarin/phenoxyphenyl moieties. Twenty novel triazolyl-based structures were successfully generated from two distinct series: 3-triazolyl coumarin derivatives (CA1–5, CE1–5) and 4-triazolyl phenoxyphenyl derivatives (PA1–5, PE1–5). The synthesis of these compounds involved coupling azide precursors, specifically 3-coumarin azide and 4-phenoxyphenyl azide, with different amide and ester derivatives of terminal alkynyl aromatic precursors. The synthesis yields ranged from 13% to 94%, as demonstrated in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1. Reagents and conditions: (a) tert BuOH : H2O = 3 : 1, sodium ascorbate 2 M, Cu(ii) sulfate 1 M, stir overnight. (A) 3-Triazolyl coumarin derivatives, (B) 4-triazolyl phenoxyphenyl derivatives.

The spectroscopic data of 20 synthesized compounds were matched successfully with their corresponding triazolyl products. The absence of azide peaks in the IR spectra at around 2100 cm−1 and the presence of a singlet peak in the 1H NMR spectrum at approximately 8.0–8.8 ppm, which corresponds to the methine proton of the triazole ring, confirmed the formation of triazolyl products.

To synthesize 3-coumarin azide,43 a two-step process (shown in Scheme 2A) was used, which was adapted from Antonijević.44 The first step involved microwave-assisted synthesis to form 3-acetaminocoumarin (1) conveniently. The cyclization of salicylaldehyde and N-acetylglycine was performed in the presence of sodium acetate and acetic anhydride under microwave conditions, producing compound 1. This approach proved to be time-efficient compared to conventional heating methods (Table 1). Next, intermediate 1 was subjected to hydrolysis to yield an amine, which was then transformed into a diazonium salt and subsequently converted to an azide by reaction with NaN3, forming 3-coumarin azide (2). 4-Phenoxyphenyl azide (3) was synthesized by converting 4-phenoxyaniline through a diazonium salt intermediate using NaNO2/HCl and NaN3 as reagents (Scheme 2B). In contrast to the click product, an azide peak at 2100 cm−1 in the IR spectra confirmed the formation of azide precursors 2 and 3.

Scheme 2. Reagents and conditions: (a) acetic anhydride, CH3COONa, microwave 140 °C 45 min; (b) HCl, NaNO2, NaN3. (A) 3-Coumarin azide, (B) 4-phenoxyphenyl azide.

Synthesis of 3-acetaminocoumarin.

| Method | T (°C) | Time (min) | Substrate (mmol) | Product (mg) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reflux | 140 | 240 | 5 | 280 | 27.5 |

| Microwave | 140 | 45 | 4 | 225 | 27.6 |

A coupling reaction prepared two terminal alkynyl precursors, amides, and esters. Propargyl amine or propargyl alcohol was coupled with various aromatic acid derivatives in the presence of EDCI HCl and DMAP, resulting in the formation of terminal alkynyl derivatives.4–13 These derivatives were generally characterized by a singlet or triplet peak in the 1H NMR spectrum, appearing at approximately 2.3 ppm, corresponding to the methine proton of the terminal alkyne group (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Reagents and conditions: (a) EDCI HCl, DMAP, dry CH2Cl2, stir 14 h.

2.2. Biological evaluations

2.2.1. In vitro Aβ aggregation inhibition study

The inhibition of Aβ aggregation by 3-triazolyl-coumarin and 4-triazolyl-phenoxyphenyl derivatives was assessed using a ThT fluorometric assay,45 with curcumin as a reference compound. In the presence of Aβ fibrils, the ThT fluorescence intensity and wavelength increase.46 To determine the optimal duration for Aβ fibril formation, a solution containing 25 μM Aβ1–42 in Tris buffer (pH 7.4) was incubated at 37 °C for 12, 24, 48, and 72 h. The maximum fluorescence emission intensity was observed after 48 h of incubation (data not displayed). Hence, a 48 h incubation time was selected for the investigation. All compounds, including curcumin, were examined for their ability to inhibit Aβ aggregation at a concentration of 100 μM. Compounds revealing an inhibitory activity exceeding 50% underwent IC50 study, and the results are summarized in Table 2. To perform IC50 calculations, we utilized the normalized data and relied on the advanced capabilities of Prism, a software package developed by the reputable GraphPad Inc. in San Diego, CA, USA.

Aβ aggregation inhibitory activities of coumarin triazolyl and phenoxyphenyl triazolyl derivatives.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R1 | X | R2 | IC50 (μM) ±SD |

| CA1 |

|

–NH– |

|

a |

| CA2 |

|

–NH– |

|

a |

| CA3 |

|

–NH– |

|

11.58 ± 1.26 |

| CA4 |

|

–NH– |

|

a |

| CA5 |

|

–NH– |

|

a |

| CE1 |

|

–O– |

|

a |

| CE2 |

|

–O– |

|

a |

| CE3 |

|

–O– |

|

17.66 ± 5.12 |

| CE4 |

|

–O– |

|

a |

| CE5 |

|

–O– |

|

0.008 ± 5.91 |

| PA1 |

|

–NH– |

|

a |

| PA2 |

|

–NH– |

|

a |

| PA3 |

|

–NH– |

|

69.20 ± 0.99 |

| PA4 |

|

–NH– |

|

1.15 ± 1.24 |

| PA5 |

|

–NH– |

|

0.04 ± 1.61 |

| PE1 |

|

–O– |

|

4.73 ± 2.53 |

| PE2 |

|

–O– |

|

a |

| PE3 |

|

–O– |

|

36.66 ± 0.89 |

| PE4 |

|

–O– |

|

0.003 ± 0.66 |

| PE5 |

|

–O– |

|

14.13 ± 6.11 |

| Curcumin | 20.34 ± 1.87 | |||

Exhibiting inhibitory activity below 50%.

As displayed in Table 2, among all compounds, PE4 and CE5 were the most effective inhibitors of Aβ aggregation with IC50 at 0.003 ± 0.66 and 0.008 ± 5.91 μM, respectively. Furthermore, CA3, CE3, PA4, PA5, PE1, and PE5 exhibited significant efficacy in inhibiting Aβ aggregation, with IC50 values ranging from 0.041 to 17.664 μM. Remarkably, these compounds had greater inhibitory effects on Aβ aggregation than the reference standard, curcumin (IC50 = 20.34 ± 1.87 μM). The data indicate that the ester linker had a stronger inhibitory effect against Aβ aggregation than the amide linker, as seen by the significant potency observed in CE5 and PE4. The presence of a double bond between the carbonyl and the terminal aromatic moiety of the ester linkage in the coumarin series led to an increase in the anti-aggregation activity. Hydroxy substitution affected the inhibitory activity, particularly in the phenoxyphenyl series. Significantly, the presence of a hydroxy group at the ortho position decreased the inhibition of Aβ aggregation compared to the absence of substitution at the terminal aromatic position. In contrast, shifting the hydroxy group to the para position and introducing the methoxy group at the meta position resulted in enhanced inhibition of Aβ aggregation. Furthermore, the ortho nitro substitution in all compounds exhibited mild anti-Aβ aggregation activity. Based on these results, pairs of compounds with distinct ester and amide linkages were selected, including CA5/CE5, PA1/PE1, PA4/PE4, and PA5/PE5, for further experiments aimed at evaluating their effectiveness against reactive oxygen species (ROS) and neuroinflammatory activities triggered by Aβ1–42.

2.2.2. In vitro anti-oxidative stress and anti-neuroinflammatory activities study

As mentioned earlier, the aggregated form of Aβ has been identified as a contributor to AD development. In the past decade, researchers have extensively investigated potential mechanisms through which this aggregated protein may stimulate harmful processes associated with AD, including the promotion of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production47 and the triggering of proinflammatory cytokine release from microglia,48 the brain's immune cells. Thus, the in vitro investigation of the tested compounds for their ability to inhibit ROS production and protect microglial cells from toxicity induced by Aβ1–42 was assessed in this assay. Furthermore, the expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 was evaluated.49

2.2.2.1. Determining the optimal concentration of Aβ1–42 for evaluating the survival rate of microglial BV-2 cells

BV-2 cells were exposed to three concentrations of Aβ1–42 (0.1, 1, and 10 μM) for 24 h, and the cell survival rate was assessed using the MTT assay (Fig. 2). Analysis of the data through one-way ANOVA followed by the LSD post hoc test revealed a significant distinction in the cell survival rates of each concentration compared to the control, indicating a dose-dependent toxic effect (F(3,11) = 674.096, P < 0.001). The survival rate of BV-2 cells depended on the concentration of Aβ1–42. At a concentration of 0.1 μM, the cell survival rate reached its highest at 54.96 ± 1.12%. Subsequently, at 1 μM, the cell survival decreased to 45.44 ± 1.42%, and at 10 μM, the cells exhibited the lowest survival rate at 37.82 ± 1.15%. Based on these findings, the 0.1 μM concentration of Aβ1–42 was selected for subsequent experiments since it resulted in 50% cell survival compared to normal cells.

Fig. 2. The survival rate of BV-2 cells was evaluated after exposure to Aβ1–42 at concentrations of 0.1, 1, and 10 μM for 24 h using the MTT assay. The presented data represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3, triplicate). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group.

2.2.2.2. Determining the nontoxic concentration of tested compounds on BV-2 cells through MTT assay

The cell viability percentage of each tested compound was evaluated at concentrations of 0, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 150, and 200 μM on BV-2 cells over 24 h. The concentrations considered non-toxic to the cells were chosen for subsequent experiments. Additional concentrations were included if the lowest concentration remained toxic to the cells. Based on the findings, all concentrations of PE4 were found to be toxic to BV-2 cells and were consequently excluded from the study. The concentration range of CE5 and PE5 was expanded, considering the possibility of cell survival at lower concentrations. The concentrations of the tested compounds, CA5/CE5, PA1/PE1, PA4, and PA5/PE5, which exhibited non-toxicity, were determined to be 40/2.5, 150/20, 20, and 40/10 μM, respectively. These concentrations were selected for further experiments.

2.2.2.3. Evaluation of tested compounds for their ability to protect BV-2 cells from toxicity induced by Aβ1–42

The MTT assay50 was employed to evaluate the protective effects of the tested compounds on BV-2 cells induced with toxicity by Aβ1–42. Fig. 3 illustrates the protective efficacy, presented as the percentage of cell viability exhibited by the tested compounds on BV-2 cells after 24 h compared to the control (#p < 0.05). It was found that CA5 and CE5 exhibited a notable ability to protect the cells with corresponding cell viabilities of 75.38 ± 2.75% and 71.28 ± 3.60%. In addition, PA5 and PE5 demonstrated a slightly lowering protective effect, yielding cell viabilities of 60.78 ± 2.32% and 62.94 ± 0.56%, respectively. Conversely, PE1 failed to alleviate cellular damage, showing cell viability of 54.10 ± 0.58%. Unfortunately, PA1 and PA4 exhibited no protective capabilities and significantly increased cytotoxicity, yielding cell viabilities of 31.60 ± 2.29% and 34.51 ± 3.76%, respectively. The results of this experiment indicate that the coumarin triazolyl scaffold exhibited an enhanced ability to protect BV-2 cells without inducing toxicities. This observation may confirm its effectiveness against Aβ aggregation, particularly in the case of CE5.

Fig. 3. The percentage of cell viability in BV-2 cells when exposed to tested compounds along with being induced with toxicity by Aβ1–42 over 24 h (n = 3, triplicate). Statistical significance was denoted as *p < 0.05 compared to the control group and #p < 0.05 compared to the Aβ1–42 group.

2.2.2.4. Inhibiting the generation of ROS in BV-2 cells triggered by Aβ1–42

To explain the survival mechanisms of BV-2 cells following toxicity induced by Aβ1–42 and subsequent exposure to CA5, CE5, PA5, and PE5 for 24 h, the capability of these compounds to inhibit the formation of reactive oxygen species was assessed using the dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) assay.51 Due to their insufficient protective efficacy, including the observed cytotoxic effects, PA1, PE1, and PA4 have been excluded from the study. Notably, the initiation of oxidative stress through the aggregation of Aβ in the neuronal system is a harmful mechanism to neuronal cells and can contribute to the development of AD.12 Evaluating ROS triggered by Aβ is an experiment to demonstrate the anti-oxidative capabilities of tested compounds, mainly through anti-Aβ aggregation. Before the assay, the tested compounds CA5, CE5, PA5, and PE5 were examined for their ability to stimulate the generation of ROS in BV-2 cells. The obtained data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA followed by LSD post hoc test. The results revealed that none of the compounds significantly stimulated BV-2 cells to produce more ROS compared to the control [F(4,14) = 1.467, P = 0.283] (Fig. 4A). The inhibitory activity of the tested compounds on ROS production in Aβ1–42-stimulated BV-2 cells is illustrated in Fig. 4B. All compounds exhibited a significant inhibition of ROS production compared to the Aβ1–42-treated group [F(5,17) = 101.748, P < 0.001]. The group of BV-2 cells that received only Aβ1–42 exhibited a significantly elevated intracellular ROS production of 150.91 ± 0.49%. In contrast, the group that received Aβ1–42 and treated with CA5 demonstrated the most effective inhibition of ROS generation, showing a reduced amount of intracellular ROS at 76.83 ± 2.11%. The additional derivatives, PE5, CE5, and PA5, also exhibit comparable potential in inhibiting ROS generation, demonstrating decreased intracellular ROS levels at 105.68 ± 1.80%, 107.04 ± 5.44%, and 137.18 ± 2.19%, respectively. The results suggest that both coumarin triazolyl and phenoxyphenyl triazolyl derivatives, linked with a segment of the ferulic acid structure (4-hydroxy-3-methoxy alkene derivative) via ester or amide linkers, exhibited outstanding anti-oxidative activities, particularly CA5. The potential mechanism of action for these tested compounds appears to involve radical scavenging, as they demonstrate the ability to generate stable radicals on the ferulic acid moiety.52

Fig. 4. The intracellular ROS generation percentage in BV-2 cells: (A) exposure to the tested compounds and (B) exposure to the tested compounds combined with induction of toxicity by Aβ1–42, both measured over 24 h (n = 3, triplicate). Statistical significance was denoted as *p < 0.05 compared to the control group, and #p < 0.05 compared to the Aβ1–42 group.

2.2.2.5. Evaluation of tested compounds for neuroinflammatory inhibition in BV-2 cells exposed to Aβ1–42-induced toxicity

An investigation was conducted utilizing ELISA to assess the efficacy of CA5, CE5, PA5, and PE5 in preventing the release of proinflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6) in BV-2 cells exposed to Aβ1–42. Cytokine expression was assessed using real-time PCR, and data analysis involved one-way ANOVA followed by an LSD post hoc test. The expression of TNFα mRNA noticeably increased in BV-2 cells exposed to Aβ1–42 (1.73 ± 0.22%). This expression decreased significantly after treatment with the tested compounds, CE5 (1.09 ± 0.09%), CA5 (0.64 ± 0.14%), and PE5 (1.19 ± 0.14%), compared to the Aβ1–42-treated group [F(5,17) = 5.522, P = 0.007] (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5. Inhibition activities of compounds CE5, CA5, PE5, and PA5 on (A) expression of TNFα mRNA, (B) IL-1β mRNA, and (C) IL-6 mRNA in BV-2 cells exposed to Aβ1–42-induced toxicity, measured over 24 h (n = 3, triplicate). Statistical significance was indicated as *p < 0.05 compared to the control group, and #p < 0.05 compared to the Aβ1–42 group.

Considering the expression of IL-1β mRNA, a notable reduction was observed following treatment with CE5, CA5, and PA5 in comparison to the Aβ1–42-treated group (0.71 ± 0.14%, 0.47 ± 0.07%, and 0.05 ± 0.01%, respectively) [F(5,17) = 41.345, P = 0.001]. Remarkably, PE5 exhibited a significant increase in IL-1β expression (8.29 ± 1.89%) compared to the Aβ1–42-treated group (1.53 ± 0.13%) (Fig. 5B).

Additionally, in terms of IL-6 mRNA expression, a notable increase was observed after treatment with PA5 (2.04 ± 0.19%) [F(5,17) = 15.114, P < 0.001]. Meanwhile, the Aβ1–42-induced toxicity led to a non-significant increase compared to the control. Similarly, the other derivatives, CE5, CA5, and PE5, showed insignificant changes in the expression of IL-6 mRNA compared to the Aβ1–42-treated group (Fig. 5C).

The findings indicate that coumarin triazolyl derivatives (CA5 and CE5) may lower the expression of TNFα and IL-1β without affecting IL-6 expression. Conversely, phenoxyphenyl triazolyl derivatives exhibit diverse effects on proinflammatory cytokine expression. Specifically, PE5 decreases TNFα generation while promoting IL-1β expression without impacting IL-6 expression. Meanwhile, PA5 significantly diminished IL-1β expression but enhanced IL-6 generation, with no observable effect on TNFα expression.

2.2.3. Re-evaluation of tested compounds for their inhibitory effect on Aβ aggregation

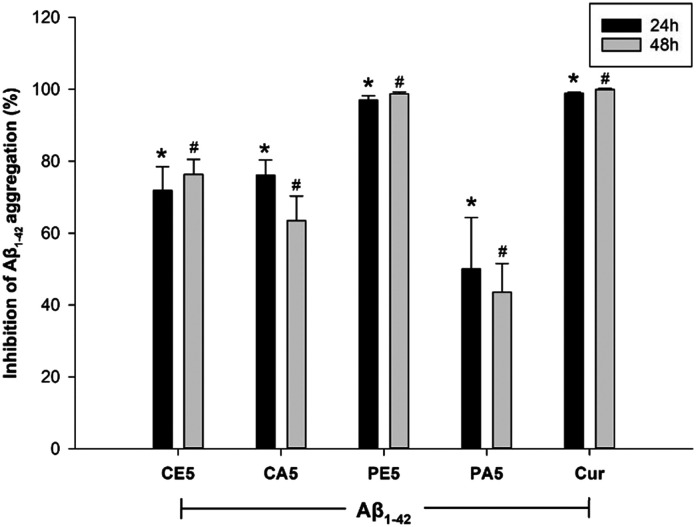

In order to confirm the anti-Aβ aggregation effect of the tested compounds, CE5, CA5, PE5, and PA5, their effect at non-toxic concentrations was re-investigated in the combination constituted of medium and other diluents, excluding BV-2 cells, under conditions similar to the previous BV-2 cell experiment. The mixture was exposed to Aβ1–42 at a concentration of 0.1 mM and the tested compounds for 24 and 48 h, with curcumin as a positive control. This evaluation was performed using the thioflavin assay. The collected data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA, followed by the LSD post hoc test. The results revealed that only the compounds significantly influenced the process of Aβ aggregation (group effect: F(5,36) = 37.835, P = 0.000). Additionally, the distinction in incubation periods between 24 and 48 h did not have a significant impact on the process of Aβ aggregation (time effect: F(1,36) = 2.888, P = 0.102; group × time effect: F(5,36) = 0.410, P = 0.837) (Fig. 6). As illustrated in Fig. 6, all tested compounds exhibit a noticeable trend, indicating their potential to inhibit the aggregation of Aβ. Notably, PE5 demonstrates the most potent activity in this regard.

Fig. 6. Anti-Aβ aggregation of compounds CE5, CA5, PE5, and PA5 in BV-2 cells exposed to Aβ1–42 over 24 and 48 h, as measured by the thioflavin assay. Curcumin served as a positive control. The data, presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3, triplicate), indicate statistical significance denoted as *p < 0.05 compared to the Aβ1–42-treated group at 24 h, and #p < 0.05 compared to the Aβ1–42-treated group at 48 h.

The morphology of BV-2 cells was investigated under different conditions: normal conditions, toxic conditions induced by Aβ1–42, and conditions in which cells were treated with the examined compounds after Aβ1–42-induced toxicity. The results presented in Fig. 7 illustrate distinct characteristics of BV-2 cell morphology. Under normal conditions, BV-2 cells exhibit a specific shape, small size, and branching characteristics (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7. Morphology of BV-2 cells under various conditions: (A) under normal (control) conditions, (B) under toxic conditions exposed to Aβ1–42, and (C) CE5 treatment under toxic conditions exposed to Aβ1–42, (D) PA4 treatment under toxic conditions exposed to Aβ1–42.

There is a noticeable transformation in toxic conditions, with cells adopting a larger circular shape and displaying reduced or absent branching features (Fig. 7B). However, when cells are treated with CE5 under toxic conditions, a significant portion of the cells regain a healthy appearance, characterized by a specific small shape and the presence of branching (Fig. 7C). Notably, the morphology of cells treated with PA4, identified as toxic, also exhibits observable changes (Fig. 7D).

2.2.4. Evaluation of tested compounds for their ability to protect SH-SY5Y cells after treatment with the supernatant from BV-2 cells exposed to Aβ1–42 and the tested compounds

Indeed, the communication between neuronal and microglial cells is essential for maintaining the proper functioning and homeostasis of the central nervous system (CNS).53 The interaction between microglia and neuronal cells plays varied roles in typical physiological and pathological conditions. When microglia become dysregulated or injured due to various stimuli, they may release proinflammatory cytokines that can impact neuronal cells, potentially contributing to the development of neurodegenerative disorders. Hence, this study verified the anti-Aβ aggregation effect of the tested compounds. These compounds demonstrated the ability to protect BV-2 cells from damage, thereby inhibiting the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, especially TNFα and IL-1β. Consequently, achieving protection for SH-SY5Y cells is expected. Following a 24 h treatment of Aβ1–42 and the tested compounds in BV-2 cells, the resulting supernatant was transferred to differentiated SH-SY5Y cells and incubated for 24 h. The survival of SH-SY5Y cells was then evaluated using the MTT assay. The collected data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA followed by the LSD post hoc test. The results depicted in Fig. 8 reveal that differentiated SH-SY5Y cells treated with the supernatant from BV-2 cells in the presence of Aβ1–42 and the tested compounds exhibit a significantly higher survival rate compared to the supernatant from BV-2 cells treated with only Aβ1–42 (F(5,35) = 19.647, P < 0.001). Among them, CE5 exhibited the most substantial potential for protecting the SH-SY5Y cells with a cell viability of 91.55 ± 1.78%, compared to the Aβ1–42-treated group (80.62 ± 0.86%). The other compounds, CA5, PE5, and PA5, also showed % cell viability higher than that of the Aβ1–42-treated group with cell viability of 88.34 ± 2.02%, 87.23 ± 1.17%, and 87.21 ± 1.76%, respectively. The elevated cell viability observed, even in the Aβ1–42-treated group, may be associated with the potential engagement of microglia actively phagocytosing abnormal protein aggregates, including Aβ plaques observed in AD.54

Fig. 8. The percentage of cell viability in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells when exposed to the supernatant from BV-2 in the presence of Aβ1–42 and the combination of Aβ1–42 with the tested compounds over 24 h. The data, presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3, triplicate), indicate statistical significance denoted as *p < 0.05 compared to the control group and #p < 0.05 compared to the Aβ1–42-treated group at 48 h.

Based on the structural features of the tested compounds that were evaluated for their biological activities, it suggests that coumarin triazolyl derivatives, specifically CE5, consistently demonstrate biological effects that indicate their potential as a new lead compound for treating neurodegenerative disorders, such as AD. As previously discussed in the section on in vitro anti-Aβ aggregation, the structure of CE5 consisting of the connection between coumarin and triazolyl rings, linked with a part of ferulic acid via an ester linkage, demonstrates significant activity in inhibiting the aggregation of Aβ. Moreover, it can inhibit Aβ aggregation in microglia cells, protecting them and subsequently reducing TNFα and IL-1β expression. This mechanism, in turn, ultimately leads to the protection of neuronal cells. Notably, numerous research studies have reported the capacity of ferulic acid and its derivatives to demonstrate antioxidant capabilities and inhibit Aβ aggregation.55,56 These findings emphasize the potential therapeutic significance of ferulic acid and its derivatives in addressing neurodegenerative disorders. The subsequent section on molecular modelling investigates the binding mechanism of CE5 with Aβ fibrils. It is significant that substituting amide with an ester bond in the case of CA5 results in a notable and extraordinary anti-oxidative stress effect. The ability of CA5 to counteract oxidative stress can be linked to its structural features, which promote the formation of stable radicals. Hence, in addition to its ability to counteract Aβ aggregation, CA5 serves as a potent radical scavenger, significantly reducing the formation of ROS.

The phenoxyphenyl triazolyl derivatives (PE5 and PA5) also demonstrated in vitro anti-Aβ aggregation. The structures within this group consist of the linkage between the phenoxyphenyl moiety and the triazole ring connected to the part of ferulic acid through either an ester (PE5) or an amide (PA5) linkage. PE5 and PA5 exhibit significant efficacy in protecting SH-SY5Y cells; however, their potency is moderately effective in protecting BV-2 cells. It is crucial to highlight that altering the linkage from ester to amide results in differing roles in promoting and suppressing proinflammatory cytokine expression. The presence of an ester linkage (PE5) induces an increase in IL-1β expression and a concurrent suppression of TNFα expression. In contrast, the amide linkage (PA5) suppresses IL-1β expression while promoting the expression of IL-6. Fig. 9 presents a schematic diagram proposing the specific mechanisms for protecting microglial and neuronal functions associated with CE5, CA5, PE5, and PA5 in this study. Therefore, further exploration is needed to investigate additional molecular mechanisms linked to PE5 and PA5.

Fig. 9. Proposed specific mechanisms of anti-amyloid beta aggregation involved microglial and neuronal protection associated with CE5, CA5, PE5, and PA5. Dotted rectangles and arrows represent non-significant effects.

2.3. Molecular modelling study

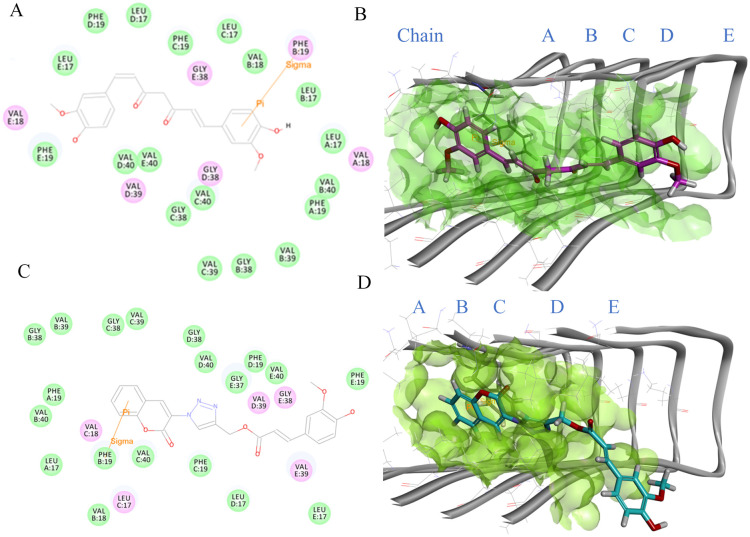

To better understand the potential interactions between CE5 and fibril, we conducted docking studies to examine the binding modes of this compound and compare it to curcumin. CE5 and curcumin were subjected to docking simulations within the active site of the Aβ17–42 pentamer's coordinates (PDB 2BEG). The binding interactions of curcumin and CE5 are presented in Fig. 10. Comparing the binding energies, CE5 exhibited a good binding energy of −73.701 kcal mol−1, better than the binding energy of curcumin (−62.065 kcal mol−1). The resulting binding energies suggest a more favorable binding affinity of CE5 to Aβ fibrils. The docking study results were found to be consistent with those obtained from in vitro studies, indicating a correlation between the computational predictions and actual biological observations.

Fig. 10. Binding mode of curcumin in the active site: (A) 2D interaction diagram within a 4 Å radius representing charge or polar interacting residues (magenta-colored circles) and van der Waals interacting residues (green circles). Sigma–π interactions represented by orange line, (B) 3D interaction of 2BEG–curcumin complex in the binding pocket. The structure is represented by a grey solid and line ribbon (2BEG), green surface (binding pocket), and pink stick (curcumin). Binding mode of CE5 in the active site: (C) 2D interaction diagram within a 4 Å radius representing charge or polar interacting residues (magenta-colored circles) and van der Waals interacting residues (green circles). Sigma–π interactions represented by orange line: (D) 3D interaction of 2BEG–CE5 complex in the binding pocket. The structure represents a grey solid and line ribbon (2BEG), green surface (binding pocket), and cyan stick (CE5).

In a previous study conducted by Ahmed et al., it was reported that the aggregation of Aβ peptides is characterized by intramolecular interactions involving Phe19/Leu34 and Gln15/Gly37 as well as intermolecular contacts between Gln15/Gly37.9 The docking study depicted in Fig. 10A and B demonstrates that the aromatic ring of curcumin engaged in a σ–π interaction with the methylene hydrogen atom adjacent to the aromatic ring of Phe19 (chain B) within the Aβ fibril. This interaction suggests that curcumin can potentially disrupt the intramolecular contacts involved in forming Phe19/Leu34 within the Aβ fibril. Like curcumin, the aromatic moiety of the coumarin ring in CE5 established a σ–π interaction with the methylene hydrogen atom adjacent to the aromatic of Phe19 (chain B). Moreover, the ferulic segment of CE5 exhibited the potential to interact with Gly37 (chain E) through van der Waals forces within the Aβ fibril (Fig. 10C and D). Interestingly, CE5 could interact with not only Phe19 but also Gly37. Considering the identified binding interactions of CE5 with Phe19 and Gly37, it can be inferred that CE5 can potentially interfere with intra- and intermolecular processes involved in forming Aβ aggregation. Furthermore, Rodríguez-Rodríguez and colleagues57 reported the binding region of ThT on Aβ fibrils, indicating that ThT occupies external crevices defined by amino acid residues 33–35 or 35–37. Consequently, CE5, through its interaction with Gly37, disrupted the interaction between ThT and Gly37, resulting in a decrease in the fluorescence intensity of ThT. The docking results are consistent with the findings of the in vitro study.

2.4. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

In addition to examining the anti-Aβ aggregation, this study provides insights into the characteristics of Aβ fibril, including fibril density, length, morphology, and quantity. Following the identification of protofibril-to-fibril transition seeding through atomic force microscopy,58 transmission electron microscopy (TEM) is a valuable instrument for evaluating these characteristics in the presence or absence of the tested compounds. This study used TEM to investigate the characteristics and quantity of Aβ fibril following incubation with curcumin and CE5. As shown in Fig. 11, the control sample (Aβ1–42 alone) displayed a high density of long linear amyloid fibrils, consistent with prior studies59 (Fig. 11A). Conversely, incubating Aβ1–42 with curcumin resulted in a reduction in Aβ fibrils (Fig. 11B). Furthermore, Aβ1–42 incubated with CE5 exhibited a collapsed Aβ fibril morphology and contained smaller amounts of Aβ fibrils than curcumin (Fig. 11C).

Fig. 11. TEM of the Aβ1–42 fibrils under different conditions: (A) Aβ1–42 alone (control), (B) in the presence of curcumin, (C) in the presence of CE5. Black arrows indicate Aβ fibrils, with the scale bars in the left and right figures representing 200 nm and 100 nm, respectively.

2.5. Physicochemical parameter-based prediction of central nervous system (CNS) penetration

Physicochemical parameters are pivotal in anticipating the pharmacokinetic properties of drugs, particularly in assessing their central nervous system (CNS) penetration. Key physicochemical parameters influencing CNS penetration prediction include molecular weight, the count of hydrogen bonds, the absence of carboxylic acid in the molecule, log P, and the polar surface area (PSA). Log P is a crucial physicochemical property that plays a significant role in predicting and understanding the pharmacokinetic behaviors of compounds for drug development. This value is directly linked to a molecule's lipophilicity or hydrophobicity, which, in turn, influences its absorption, distribution, and ability to penetrate biological barriers like the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Compounds with higher log P values tend to be more lipophilic, potentially impacting their bioavailability, cellular uptake, and overall pharmacological activity. Hence, to explore the efficacy of newly developed compounds for treating brain diseases, log P values were determined for the 20 synthesized compounds using a modified shake-flask procedure.60Table 3 details the log P results and other relevant parameters computed using SwissADME.61

Log P values and other calculated physicochemical parameters using SwissADME for the synthesized compounds.

| Compounds | Log P (mean ± % rsd) | H-bonds | PSA (Å2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA1 (MW = 346 g mol−1) | 2.25 ± 0.03 | H-donors = 1 | 90.02 |

| H-acceptors = 5 | |||

| CA2 (MW = 362.34 g mol−1) | 2.02 ± 0.08 | H-donors = 2 | 110.25 |

| H-acceptors = 6 | |||

| CA3 (MW = 405.36 g mol−1) | 1.90 ± 0.04 | H-donors = 1 | 135.84 |

| H-acceptors = 7 | |||

| CA4 (MW = 392.36 g mol−1) | 1.95 ± 0.03 | H-donors = 2 | 119.48 |

| H-acceptors = 7 | |||

| CA5 (MW = 418.40 g mol−1) | 2.65 ± 0.03 | H-donors = 2 | 119.48 |

| H-acceptors = 7 | |||

| CE1 (MW = 347.32 g mol−1) | 2.38 ± 0.05 | H-donors = 0 | 87.22 |

| H-acceptors = 6 | |||

| CE2 (MW = 363.32 g mol−1) | 2.65 ± 0.07 | H-donors = 1 | 107.45 |

| H-acceptors = 7 | |||

| CE3 (MW = 406.35 g mol−1) | 2.41 ± 0.06 | H-donors = 0 | 133.04 |

| H-acceptors = 8 | |||

| CE4 (MW = 393.35 g mol−1) | 2.61 ± 0.06 | H-donors = 1 | 116.68 |

| H-acceptors = 8 | |||

| CE5 (MW = 419.39 g mol−1) | 2.64 ± 0.10 | H-donors = 1 | 116.68 |

| H-acceptors = 8 | |||

| PA1 (MW = 370.40 g mol−1) | 4.21 ± 0.06 | H-donors = 1 | 69.04 |

| H-acceptors = 4 | |||

| PA2 (MW = 386.40 g mol−1) | NDa | H-donors = 2 | 89.27 |

| H-acceptors = 5 | |||

| PA3 (MW = 420.43 g mol−1) | 3.76 ± 0.25 | H-donors = 1 | 114.86 |

| H-acceptors = 6 | |||

| PA4 (MW = 416.43 g mol−1) | 4.26 ± 0.07 | H-donors = 2 | 98.50 |

| H-acceptors = 6 | |||

| PA5 (MW = 442.47 g mol−1) | 4.44 ± 0.08 | H-donors = 2 | 98.5 |

| H-acceptors = 6 | |||

| PE1 (MW = 371.39 g mol−1) | 5.19 ± 0.25 | H-donors = 0 | 66.24 |

| H-acceptors = 5 | |||

| PE2 (MW = 387.39 g mol−1) | 5.18 ± 0.29 | H-donors = 1 | 86.47 |

| H-acceptors = 6 | |||

| PE3 (MW = 430.41 g mol−1) | 4.29 ± 1.35 | H-donors = 0 | 112.06 |

| H-acceptors = 7 | |||

| PE4 (MW = 417.41 g mol−1) | 4.47 ± 0.16 | H-donors = 1 | 95.70 |

| H-acceptors = 7 | |||

| PE5 (MW = 443.45 g mol−1) | 4.92 ± 0.12 | H-donors = 1 | 95.70 |

| H-acceptors = 7 |

Not determined.

The recommended criteria for assessing CNS drug penetration include log P values ranging from 1 to 3, molecular weight below 450, no more than two hydrogen bond donors, fewer than six hydrogen bond acceptors, and PSA less than 60–70 Å2.62 These indicate favorable structural properties for effective pharmacological activity. None of our designed compounds contain the carboxylic group. The findings presented in Table 3 suggest that the coumarin triazolyl derivatives exhibit favorable characteristics for development as CNS drugs, particularly considering their log P values falling within the range of 1.90 ± 0.04 to 2.61 ± 0.06. Conversely, the phenoxyphenyl triazolyl derivatives demonstrate highly lipophilic properties, as indicated by their log P values exceeding 3 (ranging from 3.76 ± 0.25 to 5.19 ± 0.25). This indicates that they are inappropriate for development as CNS drugs. However, exploring specific structural adjustments designed to fulfill the criteria for hydrogen bonds and polar surface area (PSA) characteristics in CE5 and CA5 is crucial. For PA2, the log P value could not be determined due to its limited solubility in both octanol and water partitions. This study concludes that CE5 and CA5 exhibit potential for development as CNS drugs.

2.6. In silico ADMET analysis and toxicological screening

The pharmacokinetic properties of the 20 synthesized compounds were evaluated using ADMET and TOPKAT modules in Biovia Discovery Studio 2022 (Accelrys, San Diego, CA, USA), including assessments of CYP2D6 binding, hepatotoxicity, Ames mutagenicity, skin and ocular irritation, and the rat oral LD50 (lethal dose 50%).63 The results of this analysis are presented in Table 4. The predicted data suggest that none of the compounds inhibit CYP2D6 and that all are non-irritant to the skin and eyes. However, the coumarin triazolyl derivatives are possibly mutagenic. Among the four promising compounds—CA5, CE5, PA5, and PE5—only CA5 tended towards hepatotoxicity, while the remaining compounds were not toxic. Similarly, CA5 showed a rat oral LD50 of 6.8 g kg−1, indicating higher toxicity compared to CE5, PA5, and PE5, which have an LD50 of 10 g kg−1. These findings highlight CE5, PA5, and PE5 as promising new compounds for inhibiting amyloid beta aggregation, supporting the advancement of novel drugs for treating Alzheimer's disease. However, further validation through experimental laboratory studies is necessary to confirm these findings.

ADMET analysis and toxicological screening of 20 synthesized compounds using Discovery Studio.

| Compounds | ADMET analysis | Toxicological screening | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | HT | AM | SI | OI | Oral toxicity | |

| CA1 | F | T | M | NI | NI | 6 |

| CA2 | F | T | M | NI | NI | 4.6 |

| CA3 | F | T | M | NI | NI | 1 |

| CA4 | F | T | M | NI | NI | 3.2 |

| CA5 | F | T | M | NI | NI | 6.8 |

| CE1 | F | F | M | NI | NI | 10 |

| CE2 | F | T | M | NI | NI | 10 |

| CE3 | F | T | M | NI | NI | 5.6 |

| CE4 | F | F | M | NI | NI | 10 |

| CE5 | F | F | M | NI | NI | 10 |

| PA1 | F | T | NM | NI | NI | 7.8 |

| PA2 | F | T | NM | NI | NI | 10 |

| PA3 | F | T | NM | NI | NI | 2.8 |

| PA4 | F | T | NM | NI | NI | 7.9 |

| PA5 | F | F | NM | NI | NI | 10 |

| PE1 | F | F | NM | NI | NI | 10 |

| PE2 | F | T | NM | NI | NI | 10 |

| PE3 | F | T | NM | NI | NI | 10 |

| PE4 | F | F | NM | NI | NI | 10 |

| PE5 | F | F | NM | NI | NI | 10 |

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, this research involved developing and synthesizing novel derivatives incorporating coumarin triazolyl and phenoxyphenyl triazolyl scaffolds. Specific derivatives, CE5, CA5, PE5, and PA5, displayed promising anti-Aβ aggregation characteristics and demonstrated anti-oxidative stress effects, leading to the inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine expressions such as TNFα and IL-1β. This mechanism contributed to the observed neuroprotective abilities, particularly evident in the potential protection of BV-2 and SH-SY5Y cells when exposed to Aβ1–42. Among the derivatives, CE5 emerged as the most potent in protecting neuronal cells by effectively inhibiting Aβ aggregation. Molecular modelling studies revealed its binding mechanism to Aβ fibrils. This binding interaction enables CE5 to hinder intra- and intermolecular processes crucial for forming Aβ aggregation. As assessed through TEM, the features of Aβ fibril, including fibril density, length, morphology, and quantity, support the anti-Aβ aggregation efficacy of CE5. Interestingly, structural modification only from ester in CE5 to amide in CA5 resulted in remarkable anti-oxidative stress properties. Furthermore, the structural features of PE5 and PA5 that differ only in their ester and amide linkers exhibit diverse effects on IL-1β and IL-6. PA5 reduces the expression of IL-1β and increases the expression of IL-6, while PE5 enhances the expression of IL-1β. Therefore, more biologically specific mechanisms related to AD of these two compounds should be further studied. The obtained log P values for CE5, CA5, and other derivatives within this group confirm their potential for BBB permeation, suggesting they could be further developed as CNS drugs. The in silico ADMET study and toxicological screening revealed the safety profiles of CE5, PA5, and PE5; only CA5 exhibited a propensity toward hepatotoxicity. Furthermore, based on this prediction, coumarin triazolyl derivatives are likely to demonstrate mutagenicity. Nevertheless, both CA5 and CE5 have shown promise as new compounds for inhibiting amyloid beta aggregation, thus supporting the advancement of novel potential lead compounds for therapeutic intervention against AD. Subsequent in vivo studies will provide additional insights in due course.

4. Experimental section

All reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used as received. All synthesized compounds were purified by column chromatography using silica gel (Merck: 70–230 mesh ASTM) and recrystallization. All melting points were recorded by melting point apparatus (Electrothermal, UK) and are uncorrected. IR spectra were obtained as KBr pellet on a Nicolet 6700 (Thermo Scientific, USA) FTIR spectrometer. All 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 or DMSO-d6 on a Bruker (Switzerland) spectrometer at 300 and 75 MHz, respectively. Coupling constants (J values) are in hertz (Hz). Mass spectra using the ESI technique were determined on an LCQ Fleet MS 2.5.0 instrument (Thermo Scientific, USA). High-resolution mass spectra were recorded using micrOTOF Bruker Daltonics Data Analysis 3.3 Bruker, Germany). Microplate readers, UV scan (Tecan, Australia), and fluorescence (S Spectramax Gemini EM, Sunnyvale, USA) were used for the Aβ aggregation inhibitory test, respectively. Final product purity was assessed through high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a YMC-Pack Pro C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm; particle 3 mm) on an Agilent liquid chromatography system. Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Gibco (Grand Island, NY, USA). Aβ1–42 powder was obtained from Abcam and dissolved in sodium hydroxide (NaOH). Chemical structure drawings were generated using PerkinElmer ChemDraw Professional version 22.2.0.3300. Murine BV-2 microglial cells (catalog no. ABC-TC212S, lot no. 01260322) were obtained from AcceGen Biotech (Fairfield, NJ, USA). The human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y (ATCC® no. CRL-2266, lot no. 70047955) was sourced from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA).

4.1. Synthesis

4.1.1. Synthesis of 3-acetaminocoumarin (1)

Salicylaldehyde (0.424 ml, 4 mmol), N-acetylglycine (469.40 mg, 4 mmol) and sodium acetate (984.36 mg, 4 mmol) in 20 ml acetic anhydride were stirred at 140 °C for 45 min with a microwave method (pressure 250, power 200, power max on and stirring high). After the reaction was completed and cooled to room temperature, water (1 L) was added and then the mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (250 ml). The organic layer was washed with water, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and evaporated to give a residue that was purified by column chromatography using EtOAc : hexane/1 : 2 as an eluent to obtain 225 mg (27.6%) of 1 as a yellow solid; m.p. 205–208 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.678 (s, 1H, H-4), 8.114 (br s, 1H, –NH), 7.524–7.271 (m, 4H, H-5, H-6, H-7, H-8), 2.255 (s, 3H, –CH3); FTIR (cm−1): 3331, 3081, 2926, 1682, 1531, 1360, 1249.

4.1.2. Synthesis of 3-coumarin azide (2)

Reflux of 1 (20 mg, 0.1 mmol) in a mixture of concentrated HCl : EtOH/2 : 1 (1.8 ml) was carried out for 2 h. To the reaction mixture which was allowed to cool in an ice bath, cool water (3.5 ml) was slowly added. After stirring at 0 °C for 15 min, sodium nitrite (18.63 mg, 0.27 mmol) was added and after stirring for the next 15 min, sodium azide (23.4 mg, 0.36 ml) was added in portions. The mixture was allowed to stir for 30 min and monitored for the complete reaction by thin layer chromatography (TLC). Then, the mixture was added to water (25 ml) and extracted with ethyl acetate (6 ml). The organic layer was washed with water, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and evaporated to give a residue that was subjected to column chromatography eluting by CHCl3 : MeOH/10 : 1. Compound 2 was obtained as a brown solid (14 mg, 75%); m.p. 120–122 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 7.516–7.429 (m, 2H, H-5, H-7), 7.373–7.282 (m, 2H, H-6, H-8), 7.231 (s, 1H, H-4); FTIR (cm−1): 3045, 2132, 1718, 1616, 1461.

4.1.3. Synthesis of 4-phenoxyphenyl azide (3)

To concentrated HCl (10 ml), 4-phenoxyanilline (185.23 mg, 1 mmol) powder was slowly added for 30 min. After cooling the reaction mixture to 0 °C in an ice bath, 1.25 M sodium nitrite (0.8 ml) was added. The mixture was stirred for 10 min and then 1 M sodium azide (1.2 ml) was added in portions. The mixture was warmed to room temperature and allowed to stir for 2 h. The reaction was worked up by adding water (250 ml) and extracting with ethyl acetate (60 ml). The organic layer was washed with water, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and evaporated to give a residue that was purified by column chromatography using CHCl3 : hexane/1 : 1 as a mobile phase. Compound 3 was obtained as a brown liquid (68.4 mg, 32.40%); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 7.380 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, H-3′, H-5′), 7.150 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H-4′), 7.045–7.02 (m, 6H, H-2, H-2′, H-3, H-5, H-6, H-6′); FTIR (cm−1): 3037, 2125, 1488, 1239.

4.2. General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8

The related carboxylic acid, including benzoic acid, salicylic acid, 2-nitrophenylacetic acid, vanillic acid, or ferulic acid (1 mmol), EDC HCl (191.65 mg, 1 mmol) and DMAP (122.13 mg, 1 mmol) were dissolved in dry dichloromethane (10 ml). Then, propargyl amine (0.064 ml, 1 mmol) was added to the mixture. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 14 h. After completion of the reaction, the mixture was filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure. The product was purified by column chromatography using EtOAc : hexane as an eluting agent.

4.2.1. Propargyl benzamide (4)

White solid; yield = 51%; m.p. 108–109 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 7.82–7.79 (m, 2H, o-Bz), 7.57–7.51 (m, 1H, p-Bz), 7.49–7.43 (m, 2H, m-Bz), 6.41 (br s, 1H, –NH), 4.28 (dd, J = 5.2, 2.4 Hz, 2H, –CH2–), 2.30 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, –CH); FTIR (cm−1): 3294, 3178, 3056, 2926, 2115, 1646, 1540, 1309.

4.2.2. Propargyl 2-hydroxybenzamide (5)

White solid; yield = 52%; m.p. 91–92 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 12.03 (s, 1H, –OH), 7.46–7.38 (m, 2H, H-4, H-6), 7.02 (dd, J = 8.4, 0.9 Hz, 1H, H-3), 6.88 (td, J = 10.2, 7.5, 1.2, 1H, H-5), 6.50 (br s, 1H, –NH–), 4.27 (dd, J = 5.1, 2.4 Hz, 2H, –CH2–), 2.34 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, –CH); FTIR (cm−1): 3367, 3272, 3051, 2937, 2121, 1652, 1532, 1446, 1250.

4.2.3. Propargyl 2-(2-nitrophenyl)acetamide (6)

Yellow solid; yield = 36%; m.p. 152–155 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.07 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.2 Hz, 1H, H-3), 7.63 (dt, J = 7.5, 1.5 Hz, 1H, H-5), 7.53–7.47 (m, 2H, H-4, H-6), 6.08 (br s, 1H, –NH–), 4.07 (dd, J = 5.2, 2.4 Hz, 2H, H-acet), 3.88 (s, 2H, –CH2–), 2.25 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, –CH); FTIR (cm−1): 3291, 3070, 2926, 2121, 1652, 1517, 1415, 1342, 1244.

4.2.4. Propargyl 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzamide (7)

Orange solid; yield = 25%; m.p. 109–110 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 7.46 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, H-2), 7.25 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.1 Hz, 1H, H-6), 6.92 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-5), 6.44 (br s, 1H, –NH–), 4.25 (dd, J = 5.25, 2.4 Hz, 2H, –CH2–), 3.92 (s, 3H, –OCH3), 2.29 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, –CH); FTIR (cm−1): 3290, 2931, 2118, 1707, 1595, 1507, 1287.

4.2.5. Propargyl (E)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)acrylamide (8)

Yellow solid (32.4 mg, 14.00%); m.p. 137–140 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 7.59 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, –CH–C O), 7.08 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.8 Hz, 1H, H-6), 7.00 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H, H-2), 6.92 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-5), 6.28 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, –CH–Ar), 5.95 (s, 1H, –OH), 5.89 (br s, 1H, –NH–), 4.21 (dd, J = 5.2, 2.7 Hz, 2H, –CH2–), 3.92 (s, 3H, –OCH3), 2.28 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, –CH); FTIR (cm−1): 3288, 2934, 2118, 1657, 1514, 1464, 1270.

4.3. General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13

The related carboxylic acid, including benzoic acid, salicylic acid, 2-nitrophenylacetic acid, vanillic acid, or ferulic acid (1 mmol), EDC HCl 191.65 mg (1 mmol) and DMAP 122.13 mg (1 mmol) were dissolved in dry dichloromethane (10 ml). Then, propargyl alcohol (0.060 ml, 1 mmol) was added to the mixture. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 14 h. After completion of the reaction, the mixture was filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure. The product was purified by column chromatography using EtOAc : hexane as an eluting agent.

4.3.1. Propargyl benzoate (9)

Colorless liquid; yield = 39%; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.07 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, o-Bz), 7.44 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, p-Bz), 7.60–7.54 (m, 2H, m-Bz), 4.93 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 2H, –CH2–), 2.56 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, –CH); FTIR (cm−1): 3297, 3062, 2945, 2126, 1726, 1599, 1452, 1268.

4.3.2. Propargyl 2-hydroxybenzoate (10)

White solid; yield = 26%; m.p. 56–57 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 10.53 (s, 1H, –OH), 7.89 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.8 Hz, 1H, H-6), 7.49 (td, J = 10.4, 7.9, 1.8 Hz, 1H, H-4), 7.00 (dd, J = 8.4, 0.9 Hz, 1H, H-3), 6.91 (td, J = 10.2, 8.1, 1.2 Hz, 1H, H-5), 4.96 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H, –CH2–), 2.58 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, –CH); FTIR (cm−1): 3448, 3252, 2925, 2131, 1683, 1506, 1456, 1290.

4.3.3. Propargyl (2-nitrophenyl)acetate (11)

Yellow solid; yield = 26%; m.p. 47–49 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.16 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H-3), 7.63 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H-5), 7.51 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, H-4), 7.39 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H-6), 4.74 (s, 2H, –CH2–), 4.09 (s, 2H, H-acet), 2.51 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H, –CH); FTIR (cm−1): 3278, 2925, 2124, 1735, 1518, 1431, 1249.

4.3.4. Propargyl 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoate (12)

White solid; yield = 15%; m.p. 62–64 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 7.69 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.8 Hz, 1H, H-6), 7.57 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, H-2), 6.96 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-5), 4.91 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 2H, –CH2–), 3.96 (s, 3H, –OCH3), 2.51 (t, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H, –CH); FTIR (cm−1): 3423, 3271, 2948, 2126, 1708, 1599, 1383, 1278.

4.3.5. Propargyl (E)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)acrylate (13)

Yellow solid; yield = 24%; m.p. 81–83 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 7.67 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, –CH–C O), 7.08 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H, H-6), 7.03 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, H-2), 6.92 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H-5), 6.31 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, –CH–Ar), 6.11 (br s, 1H, –OH), 4.81 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H, –CH2–), 3.92 (s, 3H, –OCH3), 2.52 (s, 1H, –CH); FTIR (cm−1): 3434, 3281, 2937, 2124, 1716, 1604, 1433, 1240.

4.4. General procedure for the synthesis of compounds CA, CE, PA, and PE

Alkynyl derivative (1 mmol) and azide derivative (1 mmol) were suspended in a 3 : 1 mixture of water and tert-butyl alcohol (4 ml). 2 M sodium ascorbate (100 μl) was added, followed by 1 M copper(ii) sulfate pentahydrate (50 μl). The heterogeneous mixture was stirred vigorously at room temperature overnight. When the mixture was clear, TLC was performed to indicate complete conversion of the reactants. Precipitation of the resulting product was achieved after adding water (10 ml) to the mixture and allowing it to stir in an ice bath for 30 min. The crude was collected by filtration, dried under vacuum and purified by column chromatography using EtOAc : hexane as an eluting agent.

4.4.1. N-((1-(2-Oxo-2H-chromen-3-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)benzamide (CA1)

Yellow solid; yield = 44%; m.p. 216–218 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.69 (s, 1H, 4-coumarin –CH–), 8.58 (s, 1H, triazole –CH–), 7.84 (dd, J = 6.9,1.8 Hz, 2H, o-benzoyl), 7.71–7.65 (m, 2H, 5,7-coumarin –CH–), 7.56–7.41 (m, 5H, 6,8-coumarin –CH–, m-benzoyl, p-benzoyl), 6.90 (s, 1H, –NH–), 4.86 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H, –CH2–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 144.9, 134.0, 133.5, 132.9, 131.7, 129.0, 128.6, 127.0, 125.6, 123.4, 116.8, 35.4; FTIR (cm−1): 3318, 3187, 2923, 1728, 1642, 1535, 1305; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 347.80 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C19H14N4O3, m/z: 369.0964 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 369.0974. HPLC purity: 100.00%.

4.4.2. 2-Hydroxy-N-((1-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-3-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)benzamide (CA2)

Yellow solid; yield = 53%; m.p. 238–240 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 9.44 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, –NH), 8.70 (s, 1H, H-4), 8.54 (s,1H, triazole), 7.94–7.87 (m, 2H, H-5, o-Bz), 7.72 (dt, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H, p-Bz), 7.54 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-8), 7.49–7.38 (m, 2H, H-7, m-Bz-C-C), 6.93–6.87 (m, 2H, H-6, m-Bz-C-O), 4.67 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H, –CH2–); 13C NMR (DMSO, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 169.2, 160.3, 156.4, 152.9, 145.4, 135.2, 134.3, 133.4, 130.0, 128.5, 125.8, 124.5, 123.7, 119.2, 118.6, 117.9, 116.7, 115.7, 34.9; FTIR (cm−1): 3268, 3181, 2923, 1729, 1609, 1492, 1220; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 363.38 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C19H14N4O4, m/z: 385.0907 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 385.0916. HPLC purity: 100.00%.

4.4.3. 2-(2-Nitrophenyl)-N-((1-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-3-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)acetamide (CA3)

Yellow solid; yield = 49%; m.p. 234–235 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.73–8.70 (m, 2H, –NH, H-4), 8.47 (s, 1H, triazole), 8.02–7.93 (m, 2H, H-5, m-Bz-C-N), 7.76–7.65 (m, 2H, m-Bz-C-C, p-Bz), 7.56–7.45 (m, 4H, H-6, H-7, H-8, o-Bz), 4.43 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H, –CH2–N), 3.93 (s, 2H, –CH2–Ar); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 169.1, 156.3, 152.9, 149.6, 145.7, 135.0, 133.8, 133.3, 131.2, 129.66, 128.7, 125.8, 124.9, 124.2, 123.7, 118.7, 116.7, 34.7; FTIR (cm−1): 3430, 3275, 2923, 1718, 1639, 1520, 1346; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 406.27 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C20H15N5O5, m/z: 428.0965 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 428.0967. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.4.4. 4-Hydroxy-3methoxy-N-((1-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-3-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)benzamide (CA4)

Yellow solid; yield = 59%; m.p. 203–204 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.93 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H, –NH), 8.70 (s, 1H, H-4), 8.48 (m, 1H, triazole), 7.95–7.92 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H, H-5), 7.72 (td, J = 7.9, 1.5 Hz, 1H, H-7), 7.54 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-8), 7.49–7.44 (m, 2H, H-6, o-Bz-C-O), 7.40 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.8 Hz, 1H, o-Bz-C-C), 6.82 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, m-Bz), 4.60 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H, –CH2–), 3.81 (s, 3H, –OCH3–); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 166.4, 156.4, 152.8, 150.1, 147.6, 146.3, 135.0, 133.3, 129.9, 125.8, 125.4, 124.4, 123.8, 121.3, 118.7, 116.7, 115.3, 111.7, 56.1, 35.1; FTIR (cm−1): 3304, 3048, 2937, 1743, 1636, 1509, 1281; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 393.88 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C20H16N4O5, m/z: 415.1013 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 415.1012. HPLC purity: 100.00%.

4.4.5. (E)-3-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-N-((1-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-3-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)acrylamide (CA5)

Yellow solid; yield = 80%; m.p. 208–210 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 9.47 (s, 1H, –OH), 8.73 (s, 1H, H-4), 8.59 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H, –NH), 8.50 (s, 1H, triazole), 7.95 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H-5), 7.73 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, H-7), 7.55 (d, J = 8.4, 1H, H-8), 7.47 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H-6), 7.39 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, –CH–Ar), 7.14 (s, 1H, o-Bz-C-O-), 7.01 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, o-Bz-C-C-), 6.79 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, m-Bz), 6.51 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, –CH–C O), 4.54 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H, –CH2–), 3.80 (s, 3H, –OCH3); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 165.9, 156.4, 152.9, 148.8, 148.3, 145.9, 140.0, 135.0, 133.3, 129.9, 126.8, 125.77, 124.2, 123.75, 122.0, 119.0, 118.7, 116.7, 116.1, 111.3, 56.0, 34.6; FTIR (cm−1): 3200, 3075, 2987, 1726, 1652, 1517, 1250; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 419.63 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C22H18N4O5, m/z: 441.1169 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 441.1169. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.4.6. (1-(2-Oxo-2H-chromen-3-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl benzoate (CE1)

Yellow solid; yield = 84%; m.p. 186–187 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.83 (s, 1H, 4-coumarin –CH–), 8.64 (s, 1H, triazole –CH–), 8.10–8.08 (m, 2H, o-benzoyl), 7.72–7.65 (m, 2H, 5,7-coumarin –CH–), 7.59 (tt, J = 7.5, 1.2, 1.2 Hz, 1H, p-benzoyl), 7.49–7.41 (m, 4H, 6,8-coumarin –CH–, m-benzoyl), 5.59 (s, 2H, –CH2–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 166.3, 152.7, 133.4, 133.2, 132.9, 129.8, 129.7, 129.7, 128.8, 128.4, 125.6, 125.0, 123.0, 118.0, 116.8, 57.9; FTIR (cm−1): 3072, 2923, 1733, 1608, 1469, 1273; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 348.07 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C19H13N3O4, m/z: 370.0804 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 370.0812. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.4.7. (1-(2-Oxo-2H-chromen-3-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl 2-hydroxybenzoate (CE2)

Yellow solid; yield = 70%; m.p. 168–170 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 10.45 (s, 1H, –OH), 8.80 (s, 1H, H-4), 8.77 (s, 1H, triazole), 7.95 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H, o-Bz), 7.79–7.71 (m, 2H, H-5, p-Bz), 7.57–7.45 (m, 3H, H-6, H-7, H-8), 7.00 (dd, J = 8.2, 0.9 Hz, 1H, m-Bz-C-O), 6.942 (dt, J = 7.6, 0.9 Hz, 1H, m-Bz-C-C), 5.57 (s, 2H, –CH2–); 13C NMR (DMSO, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 168.7, 160.5, 156.4, 152.9, 142.4, 136.3, 135.6, 133.5, 130.6, 130.0, 126.5, 125.8, 123.6, 119.9, 118.6, 117.9, 116.8, 113.4, 58.4; FTIR (cm−1): 3425, 3184, 2924, 1733, 1675, 1486, 1252; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 364.76 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C19H13N3O5, m/z: 386.0747 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 386.0765. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.4.8. (1-(2-Oxo-2H-chromen-3-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl 2-(2-nitrophenyl)acetate (CE3)

White solid; yield = 13%; m.p. 164–165 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.76 (s, 1H, –OH), 8.68 (s, 1H, triazole), 8.12 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.5 Hz, 1H, m-Bz-C-N), 7.95 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H, H-5), 7.77–7.72 (m, 2H, H-4, H-7), 7.63–7.54 (m, 3H, H-8, o-Bz, p-Bz), 7.48 (dt, J = 7.5, 0.9, 1H, H-6), 5.30 (s, 2H, –CH2–O), 4.15 (s, 2H, –CH2–Ar); 13C NMR (DMSO, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 170.3, 156.3, 152.9, 148.8, 142.5, 135.4, 134.5, 134.3, 133.4, 130.1, 130.0, 129.4, 126.3, 125.8, 125.4, 123.6, 118.64, 116.8, 57.9, 31.2; FTIR (cm−1): 3201, 2926, 1736, 1611, 1528, 1332, 1214; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 407.07 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C20H14N4O6, m/z: 429.0806 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 429.0807. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.4.9. (1-(2-Oxo-2H-chromen-3-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoate (CE4)

Yellow solid; yield = 49%; m.p. 196–197 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.76 (s, 1H, H-4), 8.75 (s, 1H, triazole), 7.95 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H, o-Bz-C-C), 7.74 (dt, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H, H-5), 7.56 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, o-Bz-C-O), 7.51–7.45 (m, 3H, H-6, H-7, H-8), 6.87 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, m-Bz), 5.47 (s, 1H, –CH2–), 3.82 (s, 3H, –OCH3–); 13C NMR (DMSO, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 165.8, 156.4, 152.9, 152.3, 147.9, 143.0, 135.5, 133.4, 130.0, 126.3, 125.8; FTIR (cm−1): 3433, 3067, 2920, 1728, 1610, 1463, 1276; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 394.28 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C20H15N3O6, m/z: 416.0853 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 416.0860. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.4.10. (1-(2-Oxo-2H-chromen-3-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl (E)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)acrylate (CE5)

Yellow solid; yield = 73%; m.p. 187–189 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 9.65 (br s, 1H, –OH), 8.76 (s, 1H, H-4), 8.72 (s, 1H, triazole), 7.95 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H, H-5), 7.75 (dt, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H, H-7), 7.63–7.55 (m, 2H, H-8, –CH–Ar–), 7.48 (dt, J = 7.5, 0.9 Hz, 1H, H-6), 7.34 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, o-Bz-C-O), 7.14 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.8 Hz, 1H, o-Bz-C-C-), 6.79 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, m-Bz), 6.54 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, –CH–C O), 5.37 (s, 2H, –CH2–), 3.81 (s, 3H, –OCH3); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 166.8, 156.4, 152.9, 150.0, 148.4, 146.2, 142.9, 135.5, 133.4, 130.0, 126.3, 125.9, 125.8, 124.7, 123.8, 118.7, 116.76, 115.9, 114.3, 111.7, 57.2, 56.1; FTIR (cm−1): 3252, 3183, 2962, 1728, 1608, 1519, 1245; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 420.95 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C22H17N3O6, m/z: 442.1010 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 442.1009. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.4.11. N-((1-(4-Phenoxyphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)benzamide (PA1)

Yellow solid; yield = 57%; m.p. 181–183 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.06 (s, 1H, triazole –CH–), 7.84 (d, J = 7.65 Hz, 2H, o-benzoyl), 7.68 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 2H, o-phenyl), 7.52 (tt, J = 7.5, 1.2,1.2 Hz, 1H, p-phenyl), 7.45–7.38 (m, 4H, phenoxy –CH–), 7.22–7.07 (m, 6H, m-phenyl, p-phenyl, m-benzoyl, –NH–), 4.82 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H, –CH2–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 168.0, 158.4, 156.7, 145.8, 134.30, 130.4, 129.0, 127.5, 124.6, 121.5, 119.3; FTIR (cm−1): 3296, 3070, 2937, 1632, 1589, 1490, 1245; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 371.56 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C22H18N4O2, m/z: 371.1508 [M + H]+; found, m/z: 371.1522. HPLC purity: 100.00%.

4.4.12. 2-Hydroxy-N-((1-(4-phenoxyphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)benzamide (PA2)

Yellow solid; yield = 49%; m.p. 133–135 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.06 (s, 1H, triazole), 7.67 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 2H, H-3, H-5), 7.59 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H, –NH), 7.53 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.2 Hz, 1H, o-Bz), 7.44–7.38 (m, 3H, H-3′, H-5′, p-Bz), 7.17–7.07 (m, 5H, H-2, H-2′, H-4′, H-6, H-6′), 7.00 (dd, J = 7.8, 0.6 Hz, 1H, m-Bz-C-O), 6.86 (dt, J = 7.5, 0.9 Hz, 1H, m-Bz-C-C), 4.81 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H, –CH2–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 170.2, 161.6, 158.1, 156.2, 144.8, 134.4, 132.0, 130.1, 125.9, 124.2, 122.4, 121.2, 119.5, 119.3, 118.8, 118.50, 114.0, 34.9; FTIR (cm−1): 3282, 3143, 2934, 1642, 1589, 1489, 1247; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 387.42 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C22H18N4O3, m/z: 409.1274 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 409.1274. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.4.13. 2-(2-Nitrophenyl)-N-((1-(4-phenoxyphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)acetamide (PA3)

Yellow solid; yield = 29%; m.p. 130–132 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.08 (dd, J = 7.5, 1.2 Hz, 3H, m-Bz-C-N), 7.96 (s, 1H, triazole), 7.70–7.60 (m, 3H, o-Bz, m-Bz-C-C, p-Bz), 7.52–7.38 (m, 4H, H-3, H-3′, H-5, H-5′), 7.22–7.07 (m, 5H, H-2, H-2′, H-4, H-6, H-6′), 6.55 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, –NH), 4.62 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H, –CH2–N), 3.94 (s, 2H, –CH2–Ar); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 169.2, 145.4, 133.7, 133.5, 132.2, 130.0, 128.6, 125.3, 124.1, 122.3, 120.9, 119.5, 119.3, 41.1, 35.3; FTIR (cm−1): 3304, 3070, 2923, 1645, 1514, 1490, 1348, 1243; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 430.76 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C23H19N5O4, m/z: 452.1329 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 452.1341. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.4.14. 4-Hydroxy-3-methoxy-N-((1-(4-phenoxyphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)benzamide (PA4)

White solid; yield = 47%; m.p. 168–170 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.05 (s, 1H, triazole), 7.67 (td, J = 9.0, 2.8 Hz, 2H, H-3, H-5), 7.47 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, o-Bz-C-O), 7.44–7.32 (m, 2H, H-3′, H-5′), 7.31 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.8 Hz, 1H, o-Bz-C-C), 7.21–7.06 (m, 6H, H-2, H-2′, H-4′, H-6, H-6′, m-Bz), 6.15, (br s, 1H, –NH), 4.79 (d, J = 5.7, 2H, –CH2–), 3.93 (s, 3H, –OCH3); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 167.2, 158.0, 156.3, 149.0, 146.6, 145.5, 132.1, 130.0, 126.0, 124.2, 122.3, 121.0, 120.3, 119.5, 119.2, 114.1, 110.3, 56.1, 35.3; FTIR (cm−1): 3263, 3150, 2929, 1636, 1609, 1509, 1250; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 417.56 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C23H20N4O4, m/z: 439.1377 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 439.1367. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.4.15. (E)-3-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-N-((1-(4-phenoxyphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)acrylamide (PA5)

Yellow solid; yield = 75%; m.p. 86–87 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.03 (s, 1H, triazole), 7.68–7.65 (m, 2H, H-3, H-5), 7.61–7.38 (m, 4H, H-3′, H-5′, –CH–Ar, o-Bz-C-C), 7.22–7.00 (m, 6H, H-2, H-2′, H-4′, H-6, H-6′, o-Bz-C-O), 7.00 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, m-Bz), 6.74 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H, –NH), 6.35 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, –CH–C O), 5.99 (s, 1H, –OH), 4.74 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H, –CH2–), 3.9 (s, 3H, –OCH3); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 166.4, 158.0, 147.5, 146.7, 145.4, 141.5, 132.1, 130.6, 130.0, 127.2, 124.2, 122.3, 121.0, 120.3, 119.5, 119.2, 117.8, 114.7, 109.5, 55.9, 35.0; FTIR (cm−1): 3268, 3062, 2925, 1656, 1589, 1513, 1271; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 443.70 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C25H22N4O4, m/z: 465.1533 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 465.1543. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.4.16. (1-(4-Phenoxyphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl benzoate (PE1)

Orange solid; yield = 77%; m.p. 94–95 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.10–8.07 (m, 3H, triazole –CH–), 7.70 (td, J = 6.15,6,3.3 Hz (2H, o-phenyl), 7.59 (tt, J = 7.5,1.2,1.2 Hz, 1H, p-benzoyl), 7.48–7.38 (m, 4H, phenoxy –CH–), 7.22–7.00 (m, 5H, m-phenyl, p-phenyl, m-benzoyl), 5.58 (s, 2H, –CH2–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 166.5, 158.1, 156.3, 143.6, 133.3, 132.1, 130.0, 129.8, 128.4, 124.2, 122.4, 119.5, 119.3, 118.6, 58.1; FTIR (cm−1): 3137, 2962, 1717, 1582, 1513, 1244; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 372.44 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C22H17N3O3, m/z: 372.1348 [M + H]+; found, m/z: 372.1364. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.4.17. (1-(4-Phenoxyphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl 2-hydroxybenzoate (PE2)

Brown solid; yield = 90%; m.p. 97–99 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 10.66 (s, 1H, –OH), 8.10 (s, 1H, triazole), 7.89 (dd, J = 7.9, 1.8 Hz, 1H, o-Bz), 7.70 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H, H-3, H-5), 7.51–7.45 (m, 1H, p-Bz), 7.44–7.39 (m, 2H, H-3′, H-5′), 7.22–7.12 (m, 3H, H-2, H-6, m-Bz-C-C), 7.09 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.2 Hz, 2H, H-2′, H-6′), 7.00 (dd, J = 8.4, 0.6 Hz, 1H, m-Bz-C-O), 6.89 (dt, J = 7.6, 1.2 Hz, 1H, H-4′),5.61 (s, 2H, –CH2–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 170.0, 161.8, 158.2, 143.0, 136.1, 131.9, 130.2, 130.1, 128.8, 124.2, 122.6, 122.5, 119.5, 119.3, 119.3, 117.6, 112.0, 58.2; FTIR (cm−1): 3428, 3131, 2923, 1668, 1613, 1516, 1250; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 388.47 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C22H17N3O4, m/z: 410.1111 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 410.1118. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.4.18. (1-(4-Phenoxyphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl 2-(2-nitrophenyl)acetate (PE3)

Yellow solid; yield = 94%; m.p. 109–111 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.14 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.2 Hz, 1H, m-Bz-C-N), 8.02 (s, 1H, triazole), 7.71 (td, J = 9.0, 3.0 Hz, 2H, H-3, H-5), 7.63 (dt, J = 7.5, 1.2 Hz, 1H, m-Bz-C-C), 7.51 (dt, J = 7.9, 1.5 Hz, 1H, p-Bz), 7.44–7.36 (m, 3H, H-3′, H-5′, o-Bz), 7.22–7.09 (m, 5H, H-2, H-2′, H-4, H-6, H-6′), 5.38 (s, 2H, –CH2–O), 4.1 (s, 2H, –CH2–Ar); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 170.1, 158.0, 156.3, 143.3, 133.8, 133.4, 132.1, 130.0, 129.5, 128.8, 125.4, 124.2, 122.4, 122.4, 119.5, 119.3, 58.4, 39.81; FTIR (cm−1): 3140, 2965, 1741, 1585, 1518, 1344, 1259; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 431.35 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C23H18N4O5, m/z: 453.1169 [M + Na]+; found, m/z:453.1188. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.4.19. (1-(4-Phenoxyphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoate (PE4)

White solid; yield = 63%; m.p. 71–73 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.09 (s, 1H, triazole), 7.70–7.67 (m, 3H, H-3, H-5, o-Bz-C-C), 7.57 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, o-Bz-C-O), 7.43–7.37 (m, 2H, H-3′, H-5′), 7.22–7.13 (m, 3H, H-2, H-4′, H-6), 7.09–7.06 (m, 2H, H-2′, H-6′), 6.94 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H, m-Bz), 5.54 (s, 2H, –CH2–), 3.96 (s, 3H, –OCH3); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 158.1, 150.4, 146.2, 143.8, 132.0, 130.0, 124.6, 124.2, 122.5, 122.4, 121.7, 119.5, 119.2, 114.2, 111.8, 57.8, 56.1; FTIR (cm−1): 3400, 3084, 2959, 1710, 1590, 1513, 1283; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 418.79 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C23H19N3O5, m/z: 440.1217 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 440.1215. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.4.20. (1-(4-Phenoxyphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl (E)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)acrylate (PE5)

Yellow solid; yield = 70%; m.p. 82–84 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz, δ ppm): 8.06 (s, 1H, triazole), 7.71–7.65 (m, 3H, H-3, H-5, –CH–Ar), 7.44–7.37 (m, 2H, H-3′, H-5′), 7.22–7.03 (m, 7H, H-2, H-2′, H-4′, H-6, H-6′, o-Bz), 6.93 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, m-Bz), 6.33 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, –CH–C O), 5.45 (s, 2H, –CH2–), 3.93 (s, 1H, –OCH3); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz, δ ppm): 167.1, 158.1, 148.2, 146.8, 145.8, 143.8, 132.1, 130.0, 126.8, 124.2, 123.3, 122.4, 122.3, 119.5, 119.2, 114.8, 114.7, 109.4, 57.5, 55.9; FTIR (cm−1): 3392, 3142, 2956, 1706, 1632, 1513, 1242; LC-MS (ESI) m/z 444.38 [M + H]+; HRMS calcd for C25H21N3O5, m/z: 466.1373 [M + Na]+; found, m/z: 446.1373. HPLC purity: 100%.

4.5. Inhibition of Aβ aggregation assay

All synthesized compounds underwent assessment for the inhibition of Aβ aggregation using the thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence method.45,64 Curcumin served as a positive control. In a 96-well plate, 1 mM of the tested compounds in DMSO (1 μl) and 25 μM Aβ1–42 in Tris buffer pH 7.4 (9 μl) were combined and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h without agitation. Following the incubation period, 5 μM ThT in Tris buffer (200 μl) was introduced to each well. The absorbance was measured on a fluorescence microplate reader, with excitation and emission wavelengths set at 446 nm and 500 nm, respectively. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate, and the recorded results were analyzed by determining the percentage inhibition of Aβ aggregation using the following equation:

A solvent blank was prepared by mixing DMSO (1 μL), Tris buffer (9 μL), and ThT (200 μL). The control was established by combining DMSO (1 μL), Aβ1–42 (9 μL), and ThT (200 μL).

If the sample demonstrated more than 50% inhibition, the concentration-dependent inhibitory activity was determined following a similar procedure. Each compound, including the positive control, was diluted from the stock solution into 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) to achieve concentrations ranging from 10 nM to 100 μM, utilizing five different concentration points, with each point done in triplicate. The percentage inhibition of each concentration point was then used to calculate the IC50 value using the software package Prism (GraphPad Inc, San Diego, CA, USA).

4.6. Cell culture and treatment

Murine microglia cells (BV-2) were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% HEPES, and 1% Glutamax at 37 °C and 5% CO2. All experimental procedures involving BV-2 cells were carried out after overnight seeding. Cell viability and ROS evaluations were conducted using cells cultured in 96-well plates at a seeding density of 1 × 104 cells per well. In the analysis of inflammatory cytokine protein expression and mRNA levels, cells were cultured in six-well plates with a seeding density of 5 × 105 cells per well. For the experiment mentioned above, nine groups were categorized as follows: (1) control BV2 cell; (2) Aβ1–42-treated BV2 cells; (3) Aβ1–42-treated BV2 cells with CA5; (4) Aβ1–42-treated BV2 cells with CE5; (5) Aβ1–42-treated BV2 cells with PA1; (6) Aβ1–42-treated BV2 cells with PE1; (7) Aβ1–42-treated BV2 cells with PA4; (8) Aβ1–42-treated BV2 cells with PA5; (9) Aβ1–42-treated BV2 cells with PE5.

4.7. Cell viability

3-(4,5-Dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2-H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) was used to assess cell viability after treatment of each experiment. Cells were incubated with MTT at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 2 h, followed by replacement of the supernatant with 100 μL DMSO. Absorbance at 570 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

4.8. Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) detection

In the dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) assay, the culture medium was replaced with 100 μl of the DCFH-DA working solution at a final concentration of 20 μM in each well. The cells were then incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 30 minutes. After incubation, the wells were washed once with DMEM and treated with the conditioned medium and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. The cellular production of superoxide was detected, and the fluorescence signals with excitation and emission wavelengths of 535 nm and 635 nm, respectively, were observed.

4.9. Cytotoxicity assay in a co-culture of microglia and neurons