Abstract

Currently, clinical practice and scientific research mostly revolve around a single disease or system, but the single disease-oriented diagnostic and therapeutic paradigm needs to be revised. This review describes how transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS), a novel non-invasive neuromodulation approach, connects the central and peripheral systems of the body. Through stimulation of the widely distributed vagus nerve from the head to the abdominal cavity, this therapy can improve and treat central system disorders, peripheral system disorders, and central-peripheral comorbidities caused by autonomic dysfunction. In the past, research on taVNS has focused on the treatment of central system disorders by modulating this brain nerve. As the vagus nerve innervates the heart, lungs, liver, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, spleen and other peripheral organs, taVNS could have an overall modulatory effect on the region of the body where the vagus nerve is widespread. Based on this physiological basis, the authors summarize the existing evidence of the taVNS ability to regulate cardiac function, adiposity, glucose levels, gastrointestinal function, and immune function, among others, to treat peripheral system diseases, and complex diseases with central and peripheral comorbidities. This review shows the successful examples and research progress of taVNS using peripheral neuromodulation mechanisms from more perspectives, demonstrating the expanded scope and value of taVNS to provide new ideas and approaches for holistic therapy from both central and peripheral perspectives.

Keywords: a novel therapy, central and peripheral systems, holistic neuromodulation, transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation

Introduction

Highlights

Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) is a novel neuromodulation therapy that has shown a similar function to invasive VNS, with the advantages of non-invasive, easy operation, excellent therapeutic efficacy and minimal side effects.

This review focuses on the application of taVNS in treating disorders of peripheral organs and the communication between central and peripheral regulations.

The application of taVNS in the field of central-peripheral comorbidities will be worth exploring in depth.

Using physics approaches, neuromodulation is known as a novel therapeutic method that is used to maintain nervous system function. The vagus nerve is a major component of the parasympathetic nervous system and plays an important role in maintaining an autonomic tone throughout the brain, thorax and abdomen1. Electrodes can be implanted and connected to the left vagus nerve trunk within the neck, which then send electrical signals to the brain for vagus nerve stimulation (VNS)2. As VNS affects the brain’s neurotransmitter system and microenvironment, and induces and enhances brain plasticity3, it has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of refractory epilepsy and depression. However, in clinical practice, this approach is limited by potential side effects, including surgical complications, dyspnoea, pharyngitis, pain and tightening of the larynx and vocal strain4. Owing to the possibility of infection and the high cost of stimulator implantation surgery, new, non-invasive, VNS techniques, such as transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS), have been developed.

taVNS promotes the coordination of the body’s physiological functions and the balance of autonomic nervous system through the vagus nerve. The auricular region is the only area where the vagus nerve is distributed on the body surface5,6, and the auricular branch of the vagus nerve (ABVN) projects to nerve centres such as the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and dorsal motor nucleus (DMN) of the vagus, comprising an important part of the aurico-vagal reflex7. Through surface electrodes on the ear concha that target the ABVN, taVNS delivers electrical currents to activate the vagus nerve circuit and to regulate the activity in the brainstem, thalamus, cerebral cortex, and other areas, further modulating related peripheral organs8–10. Accordingly, taVNS can be used to treat various systemic disorders by targeting central and peripheral organs, offering therapeutic benefits similar to those of VNS. Moreover, taVNS is widely favoured by the public because of its non-invasive nature, easy of use, excellent therapeutic efficacy and minimal side effects.

Recently, taVNS therapy has been widely applied to regulate disorders of the central nervous system (CNS), including epilepsy, depression, insomnia, migraine, anxiety, fear, cognitive impairment, posttrauma stress disorder, Parkinson’s disease, disorders of consciousness, and cognitive decline10–12. Additionally, there has been an increasing amount of research on the modulatory effects on the peripheral nervous system since the vagus nerve may improve the function of the peripheral nervous system through neuroendocrine pathways. The vagus nerve innervates peripheral organs such as the heart, lungs, liver, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract and spleen in addition to the brain network, therefore taVNS therapy could be effective in treating disorders caused by autonomic dysfunction of both the central and peripheral systems. Complex central-peripheral comorbidities often occur in humans as a whole, and such conditions could also be ameliorated with vagal neuromodulation therapy. As the role of the vagus nerve becomes increasingly recognized and appreciated in clinical practice and surgical interventions13, although the application of taVNS in the CNS has been extensively studied, a comprehensive review of its effects and mechanisms of action in the peripheral nervous system is lacking.

We aimed to provide insights into taVNS effects on key physiological processes in the cardiovascular, endocrine, gastrointestinal and immune systems, as well as beneficial therapeutic effects on peripheral disorders and central-peripheral comorbidities, and how these effects are achieved through interactions between the central and peripheral systems. We expect that this review will provide a new therapeutic approach to address central and peripheral system diseases.

Relationship between taVNS and central and peripheral organs

The vagus nerve consists of 20% motor efferent and 80% sensory afferent fibres14. The functions of both the autonomic and CNS can be modified by auricular vagal stimulation via projections from the ABVN to the NTS15. Our previous study reported that after injecting horseradish peroxidase into the subcutaneous part of the auricular concha region, it mainly distributed in the ABVN, whose projection fibres lead to the NTS and DMN7, providing the morphological basis for the ‘auricular vagus association theory’15,16. Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies have also demonstrated that vagal afferent fibres project to the NTS, which has direct or indirect connections to other brain regions17.

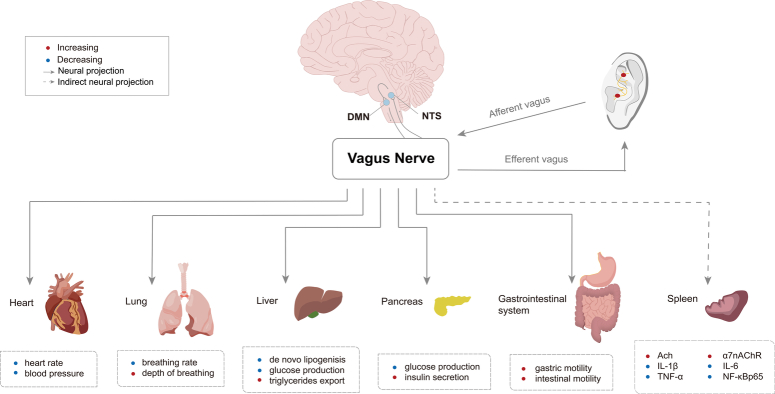

Currently, the generally accepted hypothesis regarding taVNS is that external somatosensory inputs interact with internal organ responses and central neural networks18. The NTS is the terminal nucleus of general visceral sensory nerve fibres, integrating taVNS afferent information and visceral autonomic afferent information, while the DMN is the final output site for central regulation of visceral parasympathetic nerve activity19,20. The vagus nerve runs from the brainstem through the neck to many peripheral organs, including the heart, lung, liver, pancreas, stomach, intestines and spleen. The efferent fibres in the vagus nerve are distributed to these internal organs, and the local vagus nerve in peripheral organs mainly originates from the NTS and DMN; therefore, the ABVN reflex is considered to be a somatic and visceral reflex.

Therefore, taVNS can directly project signals to the NTS and further to the DMN through neural synaptic connections, causing neuronal excitation in the DMN and finally transmitting the centrally integrated signals to the vicinity of peripheral organs innervated by the vagus nerve, releasing neurotransmitters and affecting the functional activities of multiple organs. In particular, these functional activities include regulating the heart rate and blood glucose levels, promoting digestion, and balancing the immune response. The effects of taVNS on peripheral organs are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Peripheral organs innervated by the vagus nerve and related functions. Ach, acetylcholine; α7nAChR, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 subunit; DMN, dorsal motor nucleus; IL, interleukin; NF-κB nuclear factor-kappa B; NTS, nucleus tractus solitaries; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

Effects of taVNS on peripheral organs

Study design

The search of PubMed was conducted on 10 April 2024 since 1 January 2004, and included the broad terms ‘taVNS [Title/Abstract]’, ‘transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation [Title/Abstract]’, ‘vagus nerve stimulation [Title/Abstract]’, and ‘auricular vagus nerve stimulation [Title/Abstract]’. Only peer-reviewed English language publications were considered.

The inclusion criteria included: a clinical randomized controlled trial (RCT) or animal experiment study; subjects with disorders associated with the peripheral nervous system or healthy participants; taVNS as the main therapy. The exclusion criteria included: non-RCT, case analyses, literature reviews, retrospective analyses, meta-analyses and guidelines. According to the above criteria, we summarized the RCT and animal experiment studies about taVNS therapy in the peripheral nervous system in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the studies of taVNS on peripheral systems.

| Subjects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Category | State | Parameters | Duration | Targeted organ/system | Outcomes |

| Dalgleish et al. 21 | Adults | Healthy | 10 Hz, 300 µs | 15 min for 1 session | Heart | The lengthening of the PQ-interval (P<0.05) was accompanied by an increase in the root mean square of successive differences (P<0.05) |

| Austelle et al. 22 | Adults | Healthy | 25 Hz, 500 μs | 2 min for 1 session | Heart | Initial increases in heart rate during the first 40 s in response to the cold pressor test were attenuated (P<0.05) |

| Yu et al. 23 | Dogs | AF | 20 Hz, 1 ms | 2 sessions 3 h per session |

Heart | Rapid atrial pacing-induced atrial remodelling was reversed (P<0.05) and AF inducibility was inhibited (P<0.05) |

| Wang et al. 24 | Dogs | MI | 16–24 V, 20 Hz, 1 ms (5 s on/ 5 s off) | 90 days 4 h per day |

Heart | Left ventricular dilatation was significantly reduced (P<0.05), left ventricular contractile and diastolic function were improved (P<0.05) and infarct size was reduced by ≈50% (P<0.01). Cardiac fibrosis was alleviated and protein expression level of collagen I, collagen III, transforming growth factor β1, and matrix metallopeptidase 9 in left ventricular tissues was significantly decreased (all P<0.01). The plasma level of high-specific C-reactive protein, norepinephrine, N-terminal pro-B-type-natriuretic peptide was significantly lower (all P<0.05) |

| Wang et al. 25 | Dogs | MI | 16–24 V, 20 Hz, 1 ms (5 s on/ 5 s off) | 6 weeks (42 sessions) 4 h per day |

Heart | Matrix metalloproteinase 9 and transforming growth factor b1 were down-regulated (both P<0.01) to improve cardiac function and prevent cardiac remodelling in the late stages after MI |

| Yu et al. 26 | Dogs | MI | 20 Hz, 1 ms (5 s on/ 5 s off) | 8 weeks (56 sessions) 2 h per session |

Heart | At 2-month follow-up, taVNS was found to significantly reduce ventricular arrhythmia inducibility (arrhythmia score: 1.8±0.8 vs. 3.6±0.7, P<0.01, compared to the MI group), decreased left stellate ganglion activity (frequency: 32±15 vs. 112±29 impulses/s; and amplitude: 0.15±0.12 mV vs. 0.38±0.12 mV, compared to MI group), and attenuated cardiac sympathetic remodelling induced by chronic MI. The nerve growth factor protein was down-regulated, and the small conductance calcium-activated potassium channel type2 protein was up-regulated in the left stellate ganglion by taVNS (both P<0.05) |

| Agarwal et al. 27 | Rats | Cardiac dysfunction | 6 V, 6 Hz, 1.0 ms | 2 weeks (7 sessions) 40 min per session |

Heart | Elevated heart rate was alleviated (P<0.05), vagal tone was improved (P<0.05) and sinus rhythm was altered (P<0.05), and cardiac hypertrophy (P<0.0001) and fibrosis (P<0.05) were improved. Cardiac caspase-3 (P<0.01), inducible nitric oxide synthase (P<0.05), and transforming growth factor expression (P<0.05) in the myocardium and levels of serum cardiac troponin I (P<0.0001) were decreased (P<0.05) |

| Kozorosky et al. 28 | Participants | Healthy | 2.0–2.3 mA, 10 Hz, 300 µs | 30 min for 1 session | Liver | taVNS significantly lowered postprandial plasma ghrelin levels (−115.5±28.3 pg/mL vs. −51.2±30.6 pg/mL, P<0.05) compared to sham-taVNS group |

| Li et al. 29 | Rats | Obesity | 2 mA, 2/15 Hz | 6 weeks (42 sessions) 30 min per session |

Liver | Body weight was reduced (P<0.05) and visceral fat loss was induced (P<0.01). More norepinephrine (P<0.05) was released in the serum and more β3-adrenoceptor (P<0.01) and uncoupling protein gene 1 (P<0.01) expression was found in the brown adipose tissue |

| Yu et al. 30 | Rats | ZDF | 2 mA, 15 Hz, 0.5 ms | 4 weeks (28 sessions) 30 min per session |

Liver | Weight gain was attenuated (P<0.05) without decreasing food intake, and hypothalamic P2Y1R expression was suppressed (P<0.05) |

| Huang et al. 31 | Patients | IGT | 1 mA, 20 Hz, ≤1 ms | 12 weeks (168 sessions) 20 min per session |

Pancreas | taVNS significantly reduced the 2 h glucose tolerance (F=5.79, P=0.004) and systolic blood pressure (F=4.21, P=0.044) over time compared with sham taVNS. taVNS also significantly decreased fasting plasma glucose (F=10.62, P<0.001) and 2 h glucose tolerance (F=25.18, P<0.001) compared with the no-treatment control group |

| Li et al. 32 | Rats | T2D | 2 mA, 2/15 Hz | 34 days (34 sessions) 30 min per session |

Pancreas | HbAlc concentration in taVNS treated rats was significantly reduced (P=0.0019), and the expression of IR in hypothalamus (P<0.01), liver (P<0.05), and skeletal muscle (P<0.01) were increased |

| Wang et al. 33 | Rats | T2D | 2 mA, 2/15 Hz | 5 weeks (35 sessions) 30 min per session |

Pancreas | taVNS would trigger a tidal secretion of melatonin and induce a steep increase followed by a gradual decrease of glycemic. The glucose concentration was reduced to a normal level in seven days and the glycemic and plasma glycosylated HbAlc levels were maintained to normal when applied for five weeks |

| Hou et al. 34 | Rats | FD | Sparse and dense waves, 2 mA, 20/100 Hz | 2 weeks (14 sessions) 30 min per session |

Gastrointestinal system | Compared with sham-taVNS (52.50±5.24%), the gastric emptying rate of taVNS group was higher (P<0.01). The release of corticosterone (P<0.05), adrenocorticotropic hormone (P<0.01) in serum, corticotropin-releasing factor (P<0.05) and its receptor (P<0.01) in the hypothalamus all decreased |

| Hou et al. 35 | Rats | FD | 0.5 mA, 100 Hz, 0.1 s-on / 0.4 s-off | 2 weeks (14 sessions) 30 min per session |

Gastrointestinal system | taVNS improved gastric emptying and increased the horizontal and vertical motion scores of the OFT (both P<0.0001). The sympathovagal ratio was normalized. The serum cytokines TNF-α (P<0.0001), IL-6 (P<0.01), IL-1β (P<0.0001) and NF-kappa B p65 (P<0.01) were decreased. The expression of duodenal desmoglein 2 (P<0.05) and occludin (P<0.01) were all increased |

| Zhu et al. 36 | Patients | FD | 0.5–1.5 mA, 25 Hz, 0.5 s (2s on/3s off) | 2 weeks (28 sessions) 1 h per session |

Gastrointestinal system | In comparison with baseline, taVNS increased maximum tolerable volume (901.2±39.6 vs. 797.1±40.3, P<0.001), reduced fullness score at 20 min (34.7±2.7 vs. 51.9±3.4, P<0.05) and 30 min (19.7±3.5 vs. 30.6±4.5, P<0.05) after the drink, reduced the dyspeptic symptoms score (9.0±1.9 vs. 11.9±1.8, P=0.01) and decreased the score of anxiety (5.8±0.8 vs. 8.4±0.8, P<0.001) and depression (3.1±0.6 vs. 6.4±0.7, P<0.001). In comparison with sham taVNS, taVNS increased the percentage of normal gastric slow waves derived from the electrogastrogram in both fasting (76.3±2.4% vs. 61.5±3.1%, P<0.001) and fed state (66.1±3.6% vs. 55.6±3.5%, P <0.05). taVNS also improved vagal activity assessed from the spectral analysis of heart rate variability derived from the ECG in both fasting (0.42±0.04 vs. 0.27±0.03, P<0.05) and fed (0.35±0.03 vs. 0.22±0.02, P<0.05) state |

| Shi et al. 37 | Patients | IBS-C | 0–2 mA, 25 Hz, 0.5 ms (2s on/3s off) | 4 weeks (56 sessions) 30 min per session |

Gastrointestinal system | taVNS increased complete spontaneous bowel movements per week (P=0.001) and decreased VAS pain score (P=0.001), improved quality of life (P=0.020) and decreased IBS symptom score (P=0.001), improved rectoanal inhibitory reflex (P=0.014) and improved rectal sensation (P<0.04), decreased a number of proinflammatory cytokines and serotonin in circulation; and enhanced vagal activity (P=0.040) compared with sham-taVNS |

| Liu et al. 38 | C57BL/6 mice | IBS-C | 25 Hz, 0.6 ms | 2 weeks (14 sessions) 30 min per session |

Gastrointestinal system | taVNS restored Lactobacillus abundance while increasing Bifidobacterium probiotic abundance at the genus level, and increased the number of c-kit-positive interstitial cells of Cajal in the myenteric plexus region (P=0.003) compared with sham taVNS |

| Hong et al. 39 | Mice | POI and endotoxemia | 1 mA, 5 V, 10 Hz | 10 min for 1 session | Gastrointestinal system | Endotoxemia‐induced IL‐6 (P<0.05) and TNF‐α (P<0.05) release was reduced, while gastrointestinal transit (P<0.05) was improved |

| Rawat et al. 40 | Rats | Colon cancer | 6 V, 6 Hz, 1 ms | 6 weeks 40 min per week |

Gastrointestinal system | The mitochondrial apoptosis was restored. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway was up-regulated through increased expression for α7nAchR and decreased expression for NF-kappa B p65, TNF-α and high mobility group box-1 (all P<0.05) |

| Zhao et al. 41 | Rats | Endotoxemia | <1 mA | 20 min for 1 session | Immune system | The serum proinflammatory cytokines levels, such as TNF-α (P<0.01), IL-1β (P<0.05), and IL-6 (P<0.01) as well as NF-kappa B p65 (P<0.01) expressions of lung tissues were suppressed |

| Wu et al. 42 | Patients | Sepsis | 3 mA, 25 Hz | 5 days (5 sessions) 30 min per session |

Immune system | The sequential organ failure assessment scores and serum TNF-α and IL-1β levels were reduced, IL-4 and IL-10 levels were increased (all P<0.01) |

| Courties et al. 43 | Patients | EHOA | 15 mA, 25 Hz, 50 µs | 4 weeks (20 sessions) 1 h per session |

Immune system | taVNS significantly reduced hand pain VAS, with a median decrease of 23.5 mm [7.7; 37.2] (P=0.001), as well as functional index for hand osteoarthritis, with a median decrease of 2 points [0.75; 5.2] (P=0.01) |

| Aranow et al. 44 | Patients | SLE | 30Hz, 300 μs | 4 d (4 sessions) 5 min per session |

Immune system | Subjects receiving taVNS had a significant decrease in pain and fatigue compared with sham taVNS and were more likely (OR=25, P=0.02) to experience a clinically significant reduction in pain |

| Lv et al. 45 | C57BL/6 mice | SLE | 1 mA, Hz, 330 μs (30 s on/ 4.5 min off) pulse width |

30 min for 1 session | Immune system | taVNS reduced the number of hippocampal microglia (P<0.001), and increased the number of surviving locus coeruleus tyrosine hydroxylase positive neurons (P<0.001). taVNS also retarded the development of lymphadenectasis and splenomegaly (P<0.05), decreased the proportion of double-negative T cells, and alleviated nephritis |

| Ylikoski et al.,46 | Patients | TRMS | 0.3–3.0 mA, 25 Hz, 250 µs | 60–90 min per session 1 year follow-up |

Ear | taVNS shifted mean values of different heart rate variability parameters toward increased parasympathetic activity in about 80% of patients |

| Shim et al. 47 | Patients | Chronic tinnitus | 1–10 mA, 25 Hz, 200 μs | 10 sessions 30 min per session |

Ear | Patients (50%) reported symptom relief in terms of a global improvement questionnaire. The mean tinnitus loudness (10–point scale) and the mean tinnitus awareness score (%) improved significantly from 6.32±2.06 to 5.16±1.52 and from 82.40±24.37% to 65.60±28.15%, respectively (both P<0.05) |

| Lehtimäki et al. 48 | Patients | Tinnitus | 0.8 mA, 25 Hz | 10 days (7 sessions) 45–60 min per session |

Ear | The severity of tinnitus was reduced. The mean scores of subjective loudness and annoyance, the mean scores of the tinnitus handicap inventory and mini-TQ questionnaires decreased significantly |

| Wu et al. 49 | Patients | Meniere disease | 1 mA, 20 Hz, 1 ms | 12 weeks (120 sessions) 30 min per session |

Ear | The Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (– 11.00, 95%CI, – 14.87 to − 7.13; P<0.001), Dizziness Handicap Inventory (− 47.26, 95%CI, − 50.23 to − 44.29; P<0.001), VAS of aural fullness (− 2.22, 95%CI, − 2.95 to − 1.49; P<0.01), and Pure Tone Thresholds (− 7.07, 95%CI, − 9.07 to − 5.06; P<0.001) were significantly decreased. The 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (14.72, 95%CI, 11.06 to 18.39; P<0.001) increased |

| Rufener et al. 50 | Participants | Healthy | 4 mA, 30 Hz, 200 μs | 37 min for 1 session | Ear | Electrophysiological measures remained stable for tones reflecting auditory sensory processing of novel, unpaired control tones |

| Luo et al. 51 | Mice | Vitiligo | 20 Hz | 4 weeks (28 sessions) 30 min per session |

Skin | The depigmented areas were reduced (P<0.05). The malondialdehyde (P<0.05) concentration significantly decreased, superoxide dismutase (P<0.05) and catalase (P<0.05) activities and tyrosinase synthesis (P<0.01) in the skin were restored. The tyrosinase synthesis in the skin increased (P<0.01). The TNF-α (P<0.05), IFN-γ (P<0.05), and IL-6 (P<0.01) concentrations in the serum decreased |

| Yang et al. 52 | Patients | CIPN | 4–6 mA, 20 Hz, 0.2 ms±30% | 30 min per session | Peripheral nervous system | Compared with the sham taVNS group, the numerical rating scale (P<0.05) and Athens Insomnia Scale (P<0.05) in the taVNS group were significantly lower after taVNS. On day 30 after taVNS, the mental component score of the Short-Form-Health Survey-12 was significantly higher (P<0.05) |

| Li et al. 53 | Rats | ZDF | 2 mA, 2/15 Hz | 34 days (34 sessions) 30 min per session |

CNS Pancreas |

taVNS decreased immobility time in forced swimming test (P<0.01)and induced acute melatonin secretion. A low melatonin level is related to the poor forced swimming test performance (R=20.544) |

| Yu et al. 54 | Rats | ZDF | 2 mA, 15 Hz, 0.5 ms | 4 weeks (28 sessions) 30 min per session |

CNS Liver Pancreas |

Body weight was reduced (P<0.05), blood glucose levels (P<0.05)were reduced and stabilized, limbic-regional P2X7R expression (P<0.05) was suppressed and depressive-like behaviours were reversed (P<0.05) |

AF, atrial fibrillation; CIPN, chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy; CNS, central nervous system; DMH, dimethyhydrazine; EHOA, erosive hand osteoarthritis; FD, functional dyspepsia; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; IL, interleukin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MI, myocardial infarction; POI, postoperative ileus; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; T2D, type 2 diabetes; taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; TRMS, tinnitus-related mental stress; VAS, visual analogue scale; VNS, vagus nerve stimulation; ZDF, Zucker diabetic fatty; ZL, Zucker lean.

taVNS regulates cardiac activity

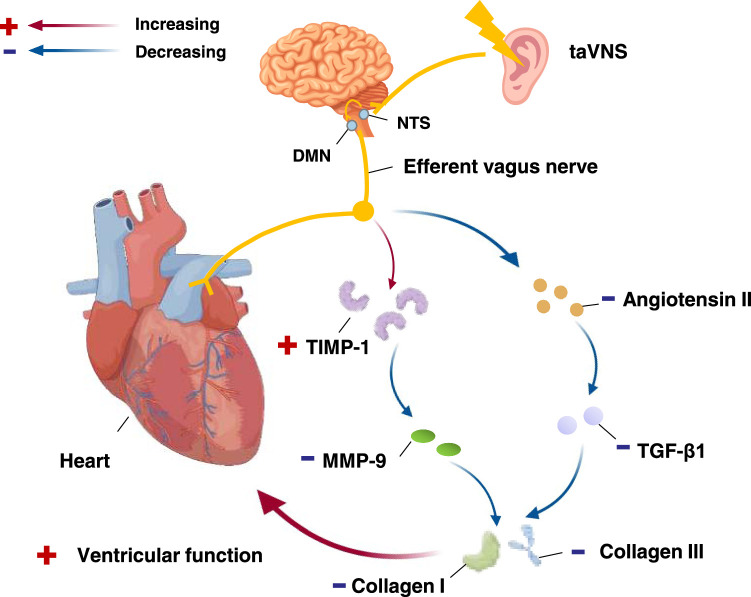

The autonomic nervous system helps maintain cardiovascular variables in a steady state, but the predominance of sympathetic activity in normal ageing or pathological conditions can adversely affect cardiovascular function8. It has been demonstrated that an imbalance of the autonomic nervous system, which is mainly manifested by increased sympathetic activity and relatively decreased vagal activity, is involved in the pathogenesis of hypertension, with sympathetic activation being the key to the pathogenesis of hypertension55. Clinical pharmacological treatments for cardiovascular diseases are associated with a high incidence of adverse side effects, while the replacement of pharmacological treatments with taVNS therapy has been proven to be effective in treating or alleviating cardiovascular diseases. taVNS can regulate the cardiac autonomic nervous system and improve the body’s sympathetic or parasympathetic balance, which then regulates cardiac and vascular functions56, improving symptoms of hypertension, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction (MI) and heart failure. The mechanism flow chart of taVNS in regulating cardiac activity was shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Functional anatomy of taVNS in requlating cardiac activity. After activating the NTS and DMN, through efferent vagus nerve, taVNS reduces the expression of TGF-β1 by regulating the reninangiotensin-aldosterone system, thereby inhibiting the formation of angiotensin II and induce the expression of TIMP-1 and decrease the activation of the MMP-9. Collagen I and III synthesis are reduced, preventing distal heart fibrosis and glial deposition to protect heart function. DMN, dorsal motor nucleus; MMP-9, matrix metallopeptidase 9; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarius; taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor β1; TIMP-1, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase 1.

Stimulation of the distribution area of the ABVN could activate cardiac-related neurons in the NTS to evoke cardiovascular inhibition, and the inferior concha produced the greatest inhibitory effect57,58. taVNS regulates cardiac and vascular functions, exerting significant cardiac inhibitory effects in healthy individuals with high heart rates under various conditions21,22,59. Direct neural recordings indicate that these antiarrhythmic effects of taVNS are mediated by suppressing the activity of the intrinsic cardiac autonomic nervous system23. Low-level taVNS can reverse rapid atrial pacing-induced atrial remodelling and inhibit the inducibility of atrial fibrillation (AF), suggesting a potential non-invasive treatment for AF60.

In patients with MI, taVNS could improve myocardial function and prevent cardiac remodelling in the late stages after myocardial infarction by downregulating the expression of matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9) and transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1)24,25. Previous studies have demonstrated that the activation and remodelling of the left stellate ganglion (LSG), induced by myocardial infarction, may be the immediate triggering mechanisms of ventricular arrhythmia61,62. Additionally, chronic low-level taVNS could reduce the inducibility of ventricular arrhythmia, LSG neural activity and sympathetic neural remodelling in a postinfarction canine model26.

The improvement in heart rate variability shows that taVNS improves autonomic homoeostasis, a beneficial effect in patients with heart failure63. In addition, taVNS treatment can help alleviate symptoms caused by chronic unpredictable stress-induced cardiac insufficiency, which provides additional evidence that taVNS is an effective complementary nonpharmacological therapy for improving cardiac function and treating cardiovascular diseases27.

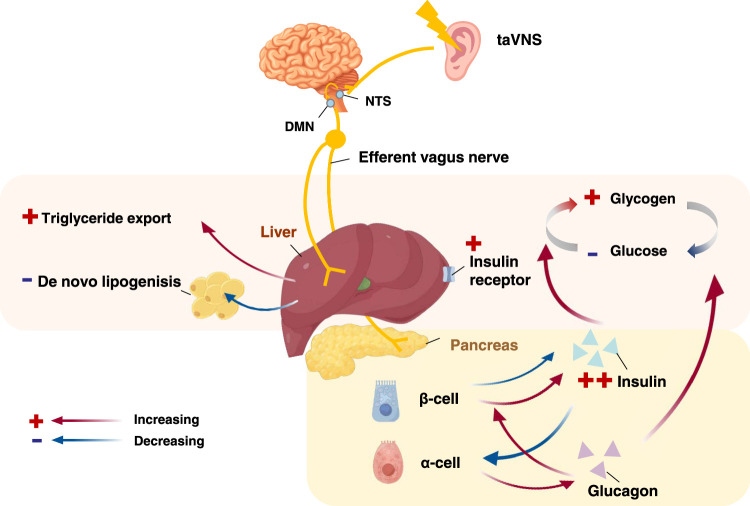

taVNS achieves lipomodulatory effects

The liver is a critical organ for lipid and glucose metabolism. Similar to other visceral organs, the liver is subject to both sympathetic and vagal innervation from the coeliac and superior mesenteric ganglia, which are involved in the modulation of hepatic function in conjunction with humoral regulation64. The hepatic vagus nerve is not only involved in normal hepatic glucose metabolism, but also plays a role in the regulation of insulin secretion, and the effect of brain leptin on hepatic triglyceride output is mediated by the vagus nerve65. The flow chart of the mechanism of taVNS regulation of glycolipid metabolism is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Functional anatomy of taVNS in regulating glucolipid metabolism. After taVNS activates the. NTS and DMN, vagal efferents reach the liver and pancreas. In the pancreas, insulin release is increased, promoting the conversion of glucose to glycogen in the liver and a decrease in blood glucose. Triglyceride output increases in the liver and de novo fat decreases. DMN, dorsal motor nucleus; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarius; taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation.

Regulating food intake and promoting fat metabolism are two important options for treating obesity. A number of studies have demonstrated that electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve can induce multiple physiological functions related to food intake, energy metabolism, and glycaemic control, which can result in appreciable weight loss66–68. In addition VNS was reported to help produce weight loss by reducing ghrelin and leptin levels69–71. It is therefore likely that taVNS could have an effect on obesity, given the antiobesity effectiveness of invasive VNS.

A previous clinical trial of taVNS in individuals with obesity demonstrated that the weight loss could temporarily decrease appetite and increase the basal metabolic rate72. Regarding appetite, taVNS significantly reduced postprandial plasma ghrelin levels, suggesting that the chronic use of taVNS may reduce food intake by inhibiting ghrelin production28. Regarding energy metabolism, a basic research study showed that taVNS was effective in reducing body weight and causing visceral fat loss. More norepinephrine was released in the serum, and the expression of b3-adrenoceptors and uncoupling protein gene 1 increased in brown adipose tissue, suggesting that energy expenditure may play an important role in the management of obesity by using taVNS29. In addition, taVNS inhibited P2Y1R expression in the hypothalamus of Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rats, which could significantly affect triacylglycerol accumulation and attenuate weight gain without decreasing food intake in ZDF rats. However, it remains to be determined whether this inhibitory effect on P2Y1R expression is mechanistically linked to the attenuation of the weight gain effect of taVNS via the acceleration of energy expenditure30.

taVNS alleviates glucose metabolism dysfunction

Islet cells in the pancreas produce insulin when blood glucose levels rise, and prolonged spikes in blood glucose levels can lead to insulin resistance and, ultimately, to diabetes. These conditions involve the dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system, resulting from either overactivation of sympathetic activity or a decrease in parasympathetic activity73–75. Adjusting the autonomic balance can be effective in lowering hyperglycaemia, and the vagus nerve, when it is activated, controls blood glucose levels by regulating the production and release of insulin by the pancreas. In recent years, taVNS has shown excellent efficacy in lowering blood glucose levels and improving glucose tolerance.

taVNS was found to reduce blood glucose levels in type 2 diabetic (T2D) rats by enhancing vagal efferent activity and glucagon-like peptide-1 release76. Moreover, a clinical study demonstrated the effectiveness of taVNS in lowering blood glucose levels and improving glucose tolerance in patients with impaired glucose tolerance patients31. taVNS also prevented the development of hyperglycaemia in ZDF rats, supporting its great potential in the treatment of diabetes and related metabolic disorders32. A basic research study showed that taVNS could increase insulin receptor expression in various tissues, including the liver and skeletal muscle, which has a long-term regulatory effect on glucose metabolism32.

Preclinical studies have been carried out to understand how taVNS exerts its glucose-lowering effects. It has been reported that taVNS has the potential to trigger melatonin release77, while melatonin plays a protective role against T2D by regulating glucose metabolism through changes in insulin secretion and leptin production78. This study showed that taVNS could induce the rhythmic secretion of melatonin, which regulates glucose metabolism and thus exerts a hypoglycaemic effect. Once-daily taVNS sessions eventually reduced the glucose concentration to a normal level in seven days and effectively maintained the normal glycaemicand plasma glycosylated haemoglobin levels when applied for five consecutive weeks. These beneficial effects were also observed in pinealectomized rats, suggesting that cycles times of taVNS could inhibit T2D by triggering the tidal secretion of melatonin, which helps produce an antidiabetic effect in patients with T2D33.

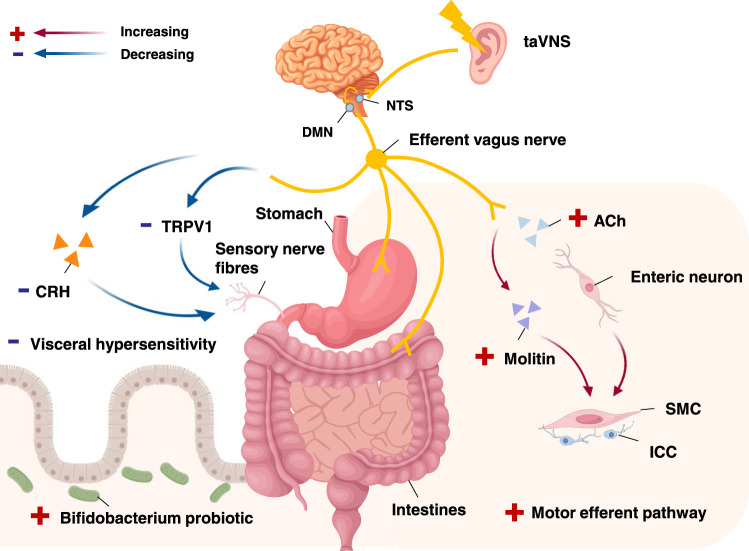

taVNS enables gastrointestinal regulation

taVNS regulates the gastrointestinal tract by activating the vagus nerve to regulate the motility and secretions of the digestive system in vivo and is involved in the regulation of gastrointestinal diseases, such as functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), postoperative ileus and colon cancer79,80.

Electrostimulation of the auricular inferior concha can cause gastric contractions57, demonstrating the effect of the vagus nerve on gastic regulation. Basic research experiments showed that taVNS significantly increased the gastric emptying rate and improved gastric motility, reduced gastric sensitivity, and alleviated low-grade inflammation in rats with functional dyspepsia (FD)34. The flow chart of the mechanism by which taVNS regulates the gastrointestinal system is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Functional anatomy of taVNS in regulating gastrointestinal system. After activating the NTS. and DMN, through efferent vagus nerve, taVNS plays a role in the gastrointestinal system to regulate gastrointestinal motility, improve intestinal flora and reduce visceral pain. ACh, acetylcholine; CRH, corticotropin-releasing factor; DMN, dorsal motor nucleus; ICC, interstitial cells of Cajal; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarius; SMC, smooth muscle cells; taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation; TRPV1, transient receptor potential vanilloid-1.

FD is closely related to the activation of inflammation, while taVNS involves the regulation of the humoral endocrine hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (adrenocorticotropic hormone and corticosterone) axis, an anti-inflammatory mechanism mediated via the vago-vagal pathway35. A clinical study showed that taVNS could improve gastric accommodation, increase the percentage of normal gastric slow waves and vagal activity, and reduce dyspeptic symptoms in patients with FD, demonstrating the potential of taVNS for the treatment of nonsevere FD36. In clinical trials of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C), taVNS could improve constipation and abdominal pain in patients with IBS-C, which might be related to the combined effects of taVNS on bowel function mediated by autoimmune mechanisms37. A recent animal experiment indicated that taVNS ameliorated IBS-C symptoms through restoring Lactobacillus abundance, increasing Bifidobacterium probiotic abundance and increasing the number of c-kit-positive interstitial cells of Cajal in the myenteric plexus region38.

In addition to treating FGIDs, taVNS has shown promising results in preventing intestinal and systemic inflammation by reducing the release of inflammatory factors, demonstrating the potential for the treatment of postoperative ileus39. A basic research study investigating the effects of taVNS on 1, 2-dimethylhydrazine (DMH)-induced colon cancer showed that taVNS restored autonomic function and cellular morphology and attenuated oxidative damage, confirming the efficacy of taVNS in the treatment of DMH-induced colon cancer and its potential to be established as a novel, non-invasive method for treating colon cancer40.

taVNS regulates immune function

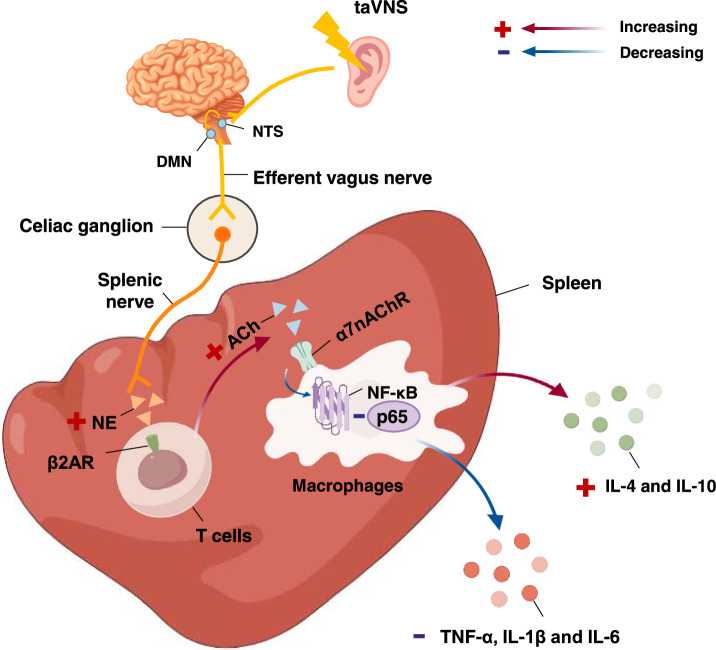

Activation of the vagus nerve reduces systemic inflammation by decreasing splanchnic and peripheral responses to inflammatory stress, and this effect involves the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (CAP)81,82. Although the spleen is not directly innervated by the vagus nerve, the vagus nerve exerts its anti-inflammatory effects through multiple intermediaries (splenic nerves and splenic T cells)83,84. Stimulation of vagal afferents reduces the release of proinflammatory cytokines by splenic macrophages through the binding of acetylcholine (Ach) to the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha-7 subunit (α7nAChR)85,86. Therefore, taVNS could be applied to treat inflammatory diseases such as endotoxaemia, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and even IBD by regulating the body’s immune function through the CAP, which reduces inflammation. The flow chart of the mechanism by which taVNS regulates the immune system is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Functional anatomy of taVNS in regulating immunity. After activation of NTS and DMN by taVNS, vagal efferent nerves modulate splanchnic nerves via the coeliac ganglion. The splanchnic nerve endings release norepinephrine, which prompts T cells to secrete acetylcholine, which then binds to α7nAChR on macrophages, inhibiting the NF-κB pathway and exerting anti-inflammatory effects. α7nAChR, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 subunit; β2AR, β2-adrenergic receptor; ACh, acetylcholine; DMN, dorsal motor nucleus; IL, interleukin; NE, norepinephrine; NF-κB: nuclear factor-κB; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarius; taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

Basic research experiments revealed that the levels of inflammatory factors, such as tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6, in the serum of endotoxaemia model rats were significantly reduced after 20 min of taVNS, and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) p65 expression was significantly down-regulated in lung tissue. These effects were reversed after the application of vagotomy or the injection of an α7nAChR antagonist, demonstrating that taVNS exerts anti-inflammatory effects by activating the CAP41. A clinical study showed that after taVNS treatment, the serum TNF-α and IL-1β levels significantly decreased and the IL-4 and IL-10 levels increased in sepsis patients, which proves that taVNS can significantly reduce the serum proinflammatory cytokine levels and increase the serum anti-inflammatory cytokine levels in sepsis patients42.

Activation of the vagus nerve inhibits inflammation and reduces pain signals. RA is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by synovial inflammation in the musculoskeletal joints, resulting in cartilage and bone damage and disability87. Clinical research has shown that taVNS significantly improves joint inflammation and clinical symptoms in patients with erosive hand osteoarthritis43. Another clinical research study showed that taVNS treatment significantly reduced pain and fatigue, and improved joint scores in systemic lupus erythematosus patients44. In addition, the ability of taVNS to retard the development of peripheral and central symptoms of SLE was proven to be mediated by an increase in the number of locus coeruleus tyrosine hydroxylase positive neurons45.

Effects of taVNS on other peripheral organs

Studies have shown that taVNS can improve the clinical symptoms of tinnitus in patients. Clinical trials46–48 have also shown symptom improvement in tinnitus patients after taVNS combined with sound therapy. Meniere’s disease (MD) is characterized by hearing loss, tinnitus and ear swelling, and there is currently no specific drugs for treating MD. A clinical trial showed that treatment with taVNS, combined with betahistine mesylate, significantly improved hearing, tinnitus symptoms and quality of life in MD patients, suggesting that taVNS could be considered an adjunctive therapy for the treatment of MD49. Another study investigated the mechanisms by which taVNS improves tinnitus symptoms and revealed that taVNS could modulate sensory-perceptual efficacy in the auditory cortex and enhance and restore sensory processing, while its combination with sensory stimulation might compensate for deficits in sensory processing by modulating neuroplasticity and related changes in the cortical structure50.

In terms of vitiligo, taVNS significantly reduced depigmented areas through its effect on melanocyte granules51. In addition, taVNS can relieve chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain in the short term, further improving the quality of life52. Thus, expanding the range of applications for taVNS merits further research.

taVNS intervention in central-peripheral comorbidities

As the command centre of the body, the brain can regulate internal organs and glands through the autonomic nervous system and the neuroendocrine system. For example, the peripheral metabolic systems are largely regulated by the mind (brain), and anxiety and depression greatly affect the functioning of these systems. Additionally, many peripheral signals contribute to the regulation of brain functions. The gastrointestinal hormones insulin and leptin are transported to the brain where they regulate innate behaviours, such as eating, and are also involved in emotional and cognitive functions. The brain can recognize peripheral inflammatory cytokines and induce a transient syndrome of fatigue, which reduces physical and social activities and causes cognitive impairment88. Based on the regulatory mechanisms of the vagus nerve in central-peripheral interactions, central-peripheral comorbidities are common in the clinic.

taVNS use for diabetes/depression comorbidity

The incidence of depression is 2–3 times greater in diabetic people than in nondiabetic people89,90. There are currently no specific drugs available for treatment. A previous study showed that long-term chronic high-fat feeding induced significant depression-like behaviours in diabetic rats, as manifested by a significant reduction in horizontal and vertical locomotor activities in an absenteeism experiment and a prolonged forced swim immobility time. These above depression-like behaviours developed concurrently with the manifestation of type 2 diabetes mellitus, and the forced swim immobility time was strongly and positively correlated with the serum glycated haemoglobin concentration. After successive taVNS interventions, the depression-like behaviour of the model rats and the progression of hyperglycaemia were simultaneously significantly alleviated32,53. The hypoglycaemic-antidepressant effect of taVNS was further demonstrated in a study that involved the purinergic 2×7 receptor (P2X7R), a target closely related to inflammation and depression, and revealed that taVNS could inhibit limbic-regional P2X7R expression and reverse depressive-like behaviour in ZDF rats54.

taVNS use for functional gastrointestinal disease/depression comorbidity

In addition to causing digestive symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and constipation, functional gastrointestinal disorders are considered a group of physical and mental disorders caused by abnormal gut–brain interactions, such as abnormal regulation of gut signals by the CNS and even concurrent clinical comorbidities, such as anxiety or depression. Basic esearch experiments revealed that taVNS intervention improved gastric motility and ameliorated depressive-like behaviour in FD rats, probably via inhibition of the corticotropin-releasing hormone pathway34. These findings provide additional evidence that taVNS can be used to treat central and peripheral comorbidities.

Discussion

Current evidence suggests that the mere overlay of traditional monotherapy approaches falls short in addressing the intricate cumulative effects resulting from the interaction of multiple diseases within the human body91. Notably, compared to implanted vagus nerve stimulation, non-invasive taVNS therapy has emerged as a promising candidate for the management of diverse systemic diseases associated with central and peripheral organs, exhibiting remarkable application potential. taVNS regulates multiple systems in the brain and body in a non-invasive manner, able to act on multiple levels to improve the disease state, including certain central-peripheral comorbidities, as a whole32,34,53,54.

Potential significance of taVNS research results

The numerous studies presented in this review not only yields substantial data regarding the utilization of taVNS in treating a range of peripheral system diseases and central-peripheral comorbidities, but also delves into the underlying mechanisms of its therapeutic action. Prior investigations have made strides in validating the therapeutic effectiveness of taVNS in peripheral diseases and central-peripheral comorbidities, including the cardiovascular, metabolic, gastrointestinal, and immune systems. Its potential as a novel therapeutic alternative to traditional medications might significantly reduce patients’ drug dependency and associated side effects, providing robust support for its utilization in peripheral disease treatment. In addition, researchers have achieved significant breakthroughs in elucidating the mechanistic basis of taVNS. By stimulating the vagus nerve in the ear concha, taVNS is capable of modulating the function of the peripheral nervous system and organs, thereby influencing physiological processes. The clarification of relevant mechanisms offers a theoretical framework for a deeper comprehension of the therapeutic impacts of taVNS.

Limitations of taVNS researches

Prior to the intervention with taVNS, for the subjects, reasonable inclusion criteria were implemented in each study. The fixed site of irritation of taVNS was also taken into account, and patients with ear infections or inflammation, broken skin or allergies in the ear were excluded. The patients with presence of pacemakers or other implanted devices in the body, pregnant women, severe cognitive impairment, or those unable to cooperate with treatment were also not suitable for the use of taVNS.

Despite the exclusion of contraindications to taVNS and taking into account the possibility of minor adverse reactions, there are still limitations in study of taVNS. Significant variations in stimulation parameters across different experimental methods are evident. Inconsistent choices of taVNS intervention parameters (intensity, frequency, duration) hinder a unified assessment of its efficacy across diseases. While only a small minority of patients43 experienced minor side effects during taVNS treatment, like skin itchiness or stinging, this may be attributed to inappropriate parameter selection.

Furthermore, the long-term efficacy of taVNS remains to be conclusively established. While some trials with follow-up periods up to 90 days showed its sustained effects24,52 others reported shorter durations. Although these trials are not directly comparable due to varying disease contexts, future studies exploring the durability of taVNS effects should emphasize rigorous follow-up assessments.

Future directions for taVNS researches

With the advancement of neuromodulation techniques, the potential of taVNS demands further exploration. Future research endeavours on taVNS should prioritize the following aspects.

Deep investigating of taVNS mechanism can guide the clinical applications more accurately. Current research suggests that taVNS achieves hypoglycaemic effects by modulating the balance of the autonomic nervous system, thereby regulating insulin secretion and glucose metabolism. It is hypothesized that taVNS triggers the release of melatonin, which in turn modulates insulin and leptin secretion, leading to improved insulin resistance. Although preliminary experiments32,33 have demonstrated that taVNS can increase plasma melatonin levels and upregulate insulin receptor expression in tissues in rats, the specific mechanisms and effects remain to be further explored and validated.

Further conducting multi-centre, large-sample RCTs is crucial to robustly validate the efficacy and safety of taVNS across various diseases. For example, taVNS demonstrated significant anti-inflammatory and anti-injury effects through the CAP pathway was validated in pilot trials of severe diseases triggered by abnormal immune system responses such as sepsis, osteoarthritis and SLE42–44. Multi-centre, large-sample RCTs are needed to further evaluate the potential of taVNS in the treatment of these inflammatory diseases. Besides, the long-term effects still require in-depth research.

More exploring of the taVNS parameters, establishing disease-specific standard parameters for various conditions, enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing side effect are imperative to optimize. They not only help achieve personalized clinical diagnosis and treatment but also enable dynamic optimization of stimulation parameters by monitoring patients’ real-time responses, thereby achieving precision medicine. Producing multifunctional medical devices of taVNS can enhance its commercial value, also promoting the development of the industrial chain for artificial intelligence algorithms and smart wearable medical devices.

Conclusions

taVNS, as a non-invasiveness, simplicity and few side effects novel therapy connecting the central and peripheral nervous systems, shows potential applications in the cardiovascular, metabolic, gastrointestinal, immune systems and comorbidities. Although there are still some shortcomings, with further research and improvements in technology, we believe that taVNS will benefit more patients in the future.

Ethical approval

Not available.

Consent

Not available.

Sources of funding

The work is supported by the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST (2021-2023ZGZJXH-QNRC003), Traditional Chinese Medicine Inheritance and Innovation ‘Hundred-Thousand-Ten Thousand’ Talent Project (Qihuang Scholars) of National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine-National Traditional Chinese Medicine Leading Talent Support Program ([2021]203), the Science and Technology Innovation Project of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (CI2021A03405, ZZ15-YQ-048), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82004181), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Public Welfare Research Institutes (ZZ-YQ2023006) and Beijing TCM Science and Technology Development Fund Project (BJZYON-2023-05).

Author contribution

N.Z., G.G., S.L. and were involved in the review concept, data research, drafting of the manuscript, and editing of the manuscript. N.Z., Q.Z. and Y.Z. prepared figures of the manuscript. C.X., Y.W., P.R., C.M.R. and G.G. were involved in drafting and editing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and approved the final submitted version

Conflicts of interest disclosure

Not available.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Not available.

Guarantor

Shaoyuan Li, Guojian Gao

Data availability statement

The data in this review are not sensitive in nature and is accessible in the public domain. The data are therefore available and not of a confidential nature.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Published online 9 May 2024

Contributor Information

Ningyi Zou, Email: zouningyi1004@163.com.

Qing Zhou, Email: 17712023991@163.com.

Yuzhengheng Zhang, Email: zyzh0102@163.com.

Chen Xin, Email: 18052168935@163.com.

Yifei Wang, Email: 565405223@qq.com.

Rangon Claire-Marie, Email: cmrangon@gmail.com.

Peijing Rong, Email: drrongpj@163.com.

Guojian Gao, Email: gaoguojian880326@163.com.

Shaoyuan Li, Email: 704488328@qq.com.

References

- 1. Kim AY, Marduy A, de Melo PS, et al. Safety of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2022;12:22055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. George MS, Nahas Z, Bohning DE, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation: a new form of therapeutic brain stimulation. CNS Spectr 2000;5:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Childs JE, DeLeon J, Nickel E, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation reduces cocaine seeking and alters plasticity in the extinction network. Learn Mem 2017;24:35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ben-Menachem E, Revesz D, Simon BJ, et al. Surgically implanted and non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation: a review of efficacy, safety and tolerability. Eur J Neurol 2015;22:1260–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peuker ET, Filler TJ. The nerve supply of the human auricle. Clin Anat 2002;15:35–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Trevizol A, Barros MD, Liquidato B, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation in neuropsychiatry: Targeting anatomy-based stimulation sites. Epilepsy Behav 2015;51:18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. He W, Jing X-H, Zhu B, et al. The auriculo-vagal afferent pathway and its role in seizure suppression in rats. BMC Neurosci 2013;14:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang Y, Li S-Y, Wang D, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation: from concept to application. Neurosci Bull 2021;37:853–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mercante B, Deriu F, Rangon C-M. Auricular neuromodulation: the emerging concept beyond the stimulation of vagus and trigeminal nerves. Medicines (Basel) 2018;5:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang L, Wang Y, Wang Y, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulators: a review of past, present, and future devices. Expert Rev Med Devices 2022;19:43–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rong P, Liu J, Wang L, et al. Effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on major depressive disorder: a nonrandomized controlled pilot study. J Affect Disord 2016;195:172–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rong P, Liu A, Zhang J, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation for refractory epilepsy: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Sci (Lond) 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dionigi G, Donatini G, Boni L, et al. Continuous monitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerve in thyroid surgery: a critical appraisal. Int J Surg 2013;11(suppl 1):S44–S46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yu ZJ, Weller RA, Sandidge K, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation: can it be used in adolescents or children with treatment-resistant depression? Curr Psychiatry Rep 2008;10:116–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. He W, Wang X, Shi H, et al. Auricular acupuncture and vagal regulation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012;2012:786839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oleson T. Auriculotherapy stimulation for neuro-rehabilitation. NeuroRehabilitation 2002;17:49–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fang J, Rong P, Hong Y, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation modulates default mode network in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2016;79:266–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kavoussi B, Ross BE. The neuroimmune basis of anti-inflammatory acupuncture. Integr Cancer Ther 2007;6:251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Andrews PLR, Sanger GJ. Abdominal vagal afferent neurones: an important target for the treatment of gastrointestinal dysfunction. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2002;2:650–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tsukamoto K, Hayakawa T, Maeda S, et al. Projections to the alimentary canal from the dopaminergic neurons in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus of the rat. Auton Neurosci 2005;123:12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dalgleish AS, Kania AM, Stauss HM, et al. Occipitoatlantal decompression and noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation slow conduction velocity through the atrioventricular node in healthy participants. J Osteopath Med 2021;121:349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Austelle CW, Sege CT, Kahn AT, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation attenuates early increases in heart rate associated with the cold pressor test. Neuromodulation 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.neurom.2023.07.012. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yu L, Scherlag BJ, Sha Y, et al. Interactions between atrial electrical remodeling and autonomic remodeling: how to break the vicious cycle. Heart Rhythm 2012;9:804–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang Z, Yu L, Wang S, et al. Chronic intermittent low-level transcutaneous electrical stimulation of auricular branch of vagus nerve improves left ventricular remodeling in conscious dogs with healed myocardial infarction. Circ Heart Fail 2014;7:1014–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang Z, Yu L, Huang B, et al. Low-level transcutaneous electrical stimulation of the auricular branch of vagus nerve ameliorates left ventricular remodeling and dysfunction by downregulation of matrix metalloproteinase 9 and transforming growth factor β1. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2015;65:342–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yu L, Wang S, Zhou X, et al. Chronic intermittent low-level stimulation of tragus reduces cardiac autonomic remodeling and ventricular arrhythmia inducibility in a post-infarction canine model. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2016;2:330–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Agarwal V, Kaushik AS, Chaudhary R, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation ameliorates cardiac abnormalities in chronically stressed rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2024;397:281–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kozorosky EM, Lee CH, Lee JG, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation augments postprandial inhibition of ghrelin. Physiol Rep 2022;10:e15253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li H, Zhang J-B, Xu C, et al. Effects and mechanisms of auricular vagus nerve stimulation on high-fat-diet--induced obese rats.. Nutrition 2015;31:1416–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yu Y, He X, Zhang J, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation inhibits hypothalamic P2Y1R expression and attenuates weight gain without decreasing food intake in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Sci Prog 2021;104:368504211009669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang F, Dong J, Kong J, et al. Effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on impaired glucose tolerance: a pilot randomized study. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li S, Zhai X, Rong P, et al. Therapeutic effect of vagus nerve stimulation on depressive-like behavior, hyperglycemia and insulin receptor expression in Zucker fatty rats. PLoS One 2014;9:e112066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang S, Zhai X, Li S, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation induces tidal melatonin secretion and has an antidiabetic effect in Zucker fatty rats. PLoS One 2015;10:e0124195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hou L-W, Fang J-L, Zhang J-L, et al. Auricular vagus nerve stimulation ameliorates functional dyspepsia with depressive-like behavior and inhibits the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis in a rat model. Dig Dis Sci 2022;67:4719–4731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hou L, Rong P, Yang Y, et al. Auricular vagus nerve stimulation improves visceral hypersensitivity and gastric motility and depression-like behaviors via vago-vagal pathway in a rat model of functional dyspepsia. Brain Sci 2023;13:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhu Y, Xu F, Lu D, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation improves functional dyspepsia by enhancing vagal efferent activity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2021;320:G700–G711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shi X, Hu Y, Zhang B, et al. Ameliorating effects and mechanisms of transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation on abdominal pain and constipation. JCI Insight 2021;6:e150052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu J, Dai Q, Qu T, et al. Ameliorating effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on a mouse model of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Neurobiol Dis 2024;193:106440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hong G-S, Zillekens A, Schneiker B, et al. Non-invasive transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation prevents postoperative ileus and endotoxemia in mice. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2019;31:e13501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rawat JK, Roy S, Singh M, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation regulates the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway to counteract 1, 2-dimethylhydrazine induced colon carcinogenesis in albino wistar rats. Front Pharmacol 2019;10:353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhao YX, He W, Jing XH, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation protects endotoxemic rat from lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012;2012:627023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu Z, Zhang X, Cai T, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation reduces cytokine production in sepsis: an open double-blind, sham-controlled, pilot study. Brain Stimul 2023;16:507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Courties A, Deprouw C, Maheu E, et al. Effect of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation in erosive hand osteoarthritis: results from a pilot trial. J Clin Med 2022;11:1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Aranow C, Atish-Fregoso Y, Lesser M, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation reduces pain and fatigue in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, double-blind, sham-controlled pilot trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lv H, Yu X, Wang P, et al. Locus coeruleus tyrosine hydroxylase positive neurons mediated the peripheral and central therapeutic effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) in MRL/lpr mice. Brain Stimul 2024;17:49–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ylikoski J, Markkanen M, Pirvola U, et al. Stress and tinnitus; transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation attenuates tinnitus-triggered stress reaction. Front Psychol 2020;11:570196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shim HJ, Kwak MY, An Y-H, et al. Feasibility and safety of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation paired with notched music therapy for the treatment of chronic tinnitus. J Audiol Otol 2015;19:159–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lehtimäki J, Hyvärinen P, Ylikoski M, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation in tinnitus: a pilot study. Acta Otolaryngol 2013;133:378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wu D, Liu B, Wu Y, et al. Meniere Disease treated with transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation combined with betahistine Mesylate: a randomized controlled trial. Brain Stimul 2023;16:1576–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rufener KS, Wienke C, Salanje A, et al. Effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation paired with tones on electrophysiological markers of auditory perception. Brain Stimul 2023;16:982–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Luo S, Meng X, Ai J, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation alleviates monobenzone-induced vitiligo in mice. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25:3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yang Y, Zhang R, Zhong Z, et al. Efficacy of transauricular vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: a randomized controlled exploratory study. Neurol Sci 2023;45:2289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Li S, Zhai X, Rong P, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation triggers melatonin secretion and is antidepressive in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. PLoS One 2014;9:e111100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yu Y, He X, Wang Y, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation inhibits limbic-regional P2X7R expression and reverses depressive-like behaviors in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Neurosci Lett 2022;775:136562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. DeLalio LJ, Sved AF, Stocker SD. Sympathetic nervous system contributions to hypertension: updates and therapeutic relevance. Can J Cardiol 2020;36:712–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Clancy JA, Mary DA, Witte KK, et al. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation in healthy humans reduces sympathetic nerve activity. Brain Stimul 2014;7:871–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gao X-Y, Zhang S-P, Zhu B, et al. Investigation of specificity of auricular acupuncture points in regulation of autonomic function in anesthetized rats. Auton Neurosci 2008;138:50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gao XY, Li YH, Liu K, et al. Acupuncture-like stimulation at auricular point Heart evokes cardiovascular inhibition via activating the cardiac-related neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius. Brain Res 2011;1397:19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Paleczny B, Seredyński R, Ponikowska B. Inspiratory- and expiratory-gated transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation have different effects on heart rate in healthy subjects: preliminary results. Clin Auton Res 2021;31:205–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yu L, Scherlag BJ, Li S, et al. Low-level transcutaneous electrical stimulation of the auricular branch of the vagus nerve: a noninvasive approach to treat the initial phase of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2013;10:428–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ajijola OA, Shivkumar K. Neural remodeling and myocardial infarction: the stellate ganglion as a double agent. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:962–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Han S, Kobayashi K, Joung B, et al. Electroanatomic remodeling of the left stellate ganglion after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:954–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Couceiro SM, Sant’Anna LB, Sant’Anna MB, et al. Auricular vagal neuromodulation and its application in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Arq Bras Cardiol 2023;120:e20220581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. McCuskey RS. Anatomy of efferent hepatic nerves. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 2004;280:821–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Metz M, Beghini M, Wolf P, et al. Leptin increases hepatic triglyceride export via a vagal mechanism in humans. Cell Metab 2022;34:1719–1731.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ikramuddin S, Blackstone RP, Brancatisano A, et al. Effect of reversible intermittent intra-abdominal vagal nerve blockade on morbid obesity: the ReCharge randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:915–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Apovian CM, Shah SN, Wolfe BM, et al. Two-year outcomes of vagal nerve blocking (vBloc) for the treatment of obesity in the ReCharge trial. Obes Surg 2017;27:169–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Val-Laillet D, Biraben A, Randuineau G, et al. Chronic vagus nerve stimulation decreased weight gain, food consumption and sweet craving in adult obese minipigs. Appetite 2010;55:245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Camilleri M, Toouli J, Herrera MF, et al. Intra-abdominal vagal blocking (VBLOC therapy): clinical results with a new implantable medical device. Surgery 2008;143:723–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Camilleri M, Toouli J, Herrera MF, et al. Selection of electrical algorithms to treat obesity with intermittent vagal block using an implantable medical device. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2009;5:224–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Gil K, Bugajski A, Thor P. Electrical vagus nerve stimulation decreases food consumption and weight gain in rats fed a high-fat diet. J Physiol Pharmacol 2011;62:637–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Shen E-Y, Hsieh C-L, Chang Y-H, et al. Observation of sympathomimetic effect of ear acupuncture stimulation for body weight reduction. Am J Chin Med 2009;37:1023–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Canale MP, Manca di Villahermosa S, Martino G, et al. Obesity-related metabolic syndrome: mechanisms of sympathetic overactivity. Int J Endocrinol 2013;2013:865965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lindmark S, Lönn L, Wiklund U, et al. Dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system can be a link between visceral adiposity and insulin resistance. Obes Res 2005;13:717–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Rodríguez-Colón SM, Li X, Shaffer ML, et al. Insulin resistance and circadian rhythm of cardiac autonomic modulation. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2010;9:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Yin J, Ji F, Gharibani P, et al. Vagal nerve stimulation for glycemic control in a rodent model of type 2 diabetes. Obes Surg 2019;29:2869–2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Liu R-P, Fang J-L, Rong P-J, et al. Effects of electroacupuncture at auricular concha region on the depressive status of unpredictable chronic mild stress rat models. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:789674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Smyth S, Heron A. Diabetes and obesity: the twin epidemics. Nat Med 2006;12:75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Han J, Wang HC, Rong PJ, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the therapeutic effect on functional dyspepsia treated with acupuncture and electroacupuncture. World J Acupuncture - Moxibustion 2020;31:44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ouyang H, Chen JDZ. Review article: therapeutic roles of acupuncture in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20:831–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Borovikova LV, Ivanova S, Zhang M, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nature 2000;405:458–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Koopman FA, Chavan SS, Miljko S, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation inhibits cytokine production and attenuates disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:8284–8289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Rosas-Ballina M, Ochani M, Parrish WR, et al. Splenic nerve is required for cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway control of TNF in endotoxemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:11008–11013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Rosas-Ballina M, Olofsson PS, Ochani M, et al. Acetylcholine-synthesizing T cells relay neural signals in a vagus nerve circuit. Science 2011;334:98–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Berthoud HR, Powley TL. Characterization of vagal innervation to the rat celiac, suprarenal and mesenteric ganglia. J Auton Nerv Syst 1993;42:153–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature 2003;421:384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2016;388:2023–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Zeng W, Yang F, Shen WL, et al. Interactions between central nervous system and peripheral metabolic organs. Sci China Life Sci 2022;65:1929–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Demir S, Nawroth PP, Herzig S, et al. Emerging Targets in Type 2 Diabetes and Diabetic Complications. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2021;8:e2100275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Mendenhall E, Kohrt BA, Norris SA, et al. Non-communicable disease syndemics: poverty, depression, and diabetes among low-income populations. Lancet 2017;389:951–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Whitty CJM, Watt FM. Map clusters of diseases to tackle multimorbidity. Nature 2020;579:494–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this review are not sensitive in nature and is accessible in the public domain. The data are therefore available and not of a confidential nature.