Abstract

The role of endoscopy in pathologies of the bile duct and gallbladder has seen notable advancements over the past two decades. With advancements in stent technology, such as the development of lumen-apposing metal stents, and adoption of endoscopic ultrasound and electrosurgical principles in therapeutic endoscopy, what was once considered endoscopic failure has transformed into failure of an approach that could be salvaged by a second- or third-line endoscopic strategy. Incorporation of these advancements in routine patient care will require formal training and multidisciplinary acceptance of established techniques and collaboration for advancement of experimental techniques to generate robust evidence that can be utilized to serve patients to the best of our ability.

Keywords: Endoscopic ultrasound, Guided biliary drainage, Gallbladder, Biliary obstruction, Lumen-apposing metal stent

Core Tip: For malignant distal biliary obstruction, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided choledochoduodenostomy is noninferior to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with biliary stent placement, and can be considered as a primary drainage modality instead of a salvage method. In cases with malignant hilar biliary obstruction, combined ERCP with EUS-biliary drainage (CERES), when performed in the appropriate patient, can not only provide bilateral drainage but also establish communication of the right and left intrahepatic biliary systems through bridging intra-hepatic stenting. EUS-guided gallbladder drainage (EUS-GBD) is increasingly being recognized as a feasible and efficacious treatment modality and should be considered in the management of cholecystitis in a multidisciplinary setting. EUS-GBD can also be incorporated in the algorithm of management of distal or hilar biliary obstruction, either as a prophylactic or a therapeutic strategy.

TO THE EDITOR

Biliary interventional endoscopy refers to the ability to treat pathologies of the biliary tract through a non-surgical, endoluminal approach. The availability of fluoroscopy, coupled with endoscopic ability to access the biliary system through the ampulla of Vater, gave rise to the now well-established modality, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)[1]. As expertise with ERCP grew, our ability to treat and palliate expanded to encompass pathologies of the biliary system which were historically managed with surgery. While this opened new avenues, it also unveiled new challenges that highlighted the need to evolve beyond ERCP through technological innovation and novel thought to address unmet needs of patients with limited options for management of their malady. This milieu led to innovations such as endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and development of the lumen-apposing metal stent (LAMS), both major milestones which continue to improve our ability to manage biliary pathologies.

Traditionally, failure of endoscopic biliary drainage meant failure of ERCP, subjecting patients to percutaneous biliary drainage (PTBD). Although PTBD is a valuable treatment option, one could argue that it adversely impacts patients’ quality of life due to its external attachments. In the current era, the availability of EUS and LAMS have served to redefine failure of endoscopic biliary drainage, as has been highlighted by Fugazza et al[2], who shed light on the role of EUS-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) in the management of gallbladder and biliary tree pathologies.

In malignant distal biliary obstruction (MDBO), EUS-choledocoduodenostomy (EUS-CDS) historically served as a salvage modality in the setting of ERCP failure. This stepwise approach allowed expansion of endoscopic techniques available for biliary decompression in patients with MDBO. As experience with EUS-CDS grew, its technical equivalency to ERCP in the setting of MDBO became evident; EUS-CDS has now been shown to be noninferior to ERCP in the ELEMENT and DRA-MBO clinical trials[3,4], and as such one may perform EUS-CDS as a primary drainage modality in appropriately selected patients. The question of cost-effectiveness of EUS-CDS as a primary drainage modality compared to ERCP in MDBO remains to be answered. In countries where LAMS are unavailable, EUS-BD still serves a useful purpose in the setting of MDBO by providing rendezvous access to allow transpapillary biliary drainage, particularly when MDBO leads to ampullary distortion.

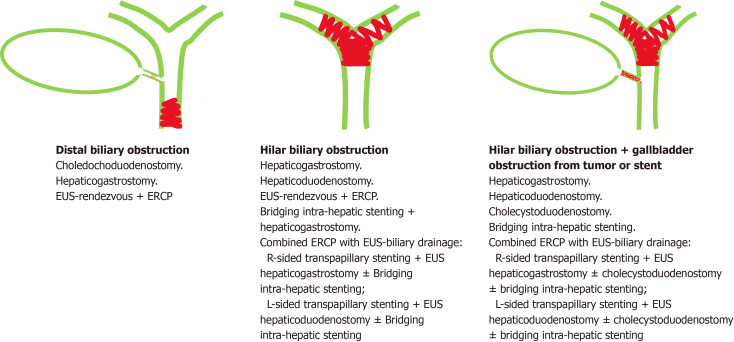

In cases with malignant hilar biliary obstruction (MHBO), EUS-BD can serve as an adjuvant drainage modality that is to be used alongside ERCP; the utility of combined ERCP with EUS-BD (CERES) allows applicability of EUS-BD in multiple configurations (Figure 1)[5,6]. The techniques of EUS-BD studied in the setting of MHBO can serve to prolong the efficacy of endoscopic biliary drainage, potentially delaying PTBD in appropriately selected patients, thereby preserving their quality of life. EUS-BD can also establish bilateral drainage of the liver in cases with high grade MHBO with non-communicating left and right biliary systems by performing bridging intra-hepatic stenting along with a hepaticogastrostomy[7]. Put together, these are promising avenues that warrant further exploration in randomized trials to validate the utility of EUS-BD in MHBO as has been done in the setting of MDBO.

Figure 1.

Role of endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage in various forms of obstruction. EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

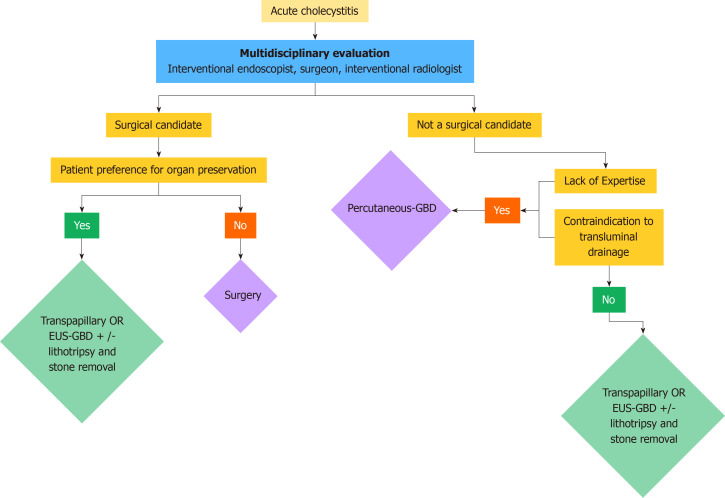

The presence or absence of gallbladder can materially alter the course of management in the setting of biliary obstruction. In the case of both MDBO and MHBO, EUS-guided gallbladder drainage (EUS-GBD) can be performed prophylactically or therapeutically. Preliminary data on EUS-GBD addressed the utility of this technique as a rescue modality, with promising results, as summarized by Fugazza et al[2]. Similar to EUS-BD, the role of EUS-GBD has evolved beyond a rescue technique and carries the potential to be incorporated in the algorithm of biliary drainage in malignant cases as a prophylactic measure. Such an approach may be of utility in cases where biliary stent placement poses the risk of cystic duct obstruction and cholecystitis; in cases with MHBO, incorporating EUS-GBD can be considered an extension of CERES, allowing bilateral drainage of the biliary tree, and maintaining gallbladder outflow. The utility of EUS-GBD has been shown primarily in the setting of cholecystitis, particularly for patients who are unfit for surgery. In the current era, incorporation of a multidisciplinary team consisting of surgeons, interventional radiologists, and interventional endoscopists to drive therapeutic decision-making in the setting of acute cholecystitis should be considered standard practice in resource-rich health systems and tertiary care centers, and will serve to increase adoption of EUS-GBD in appropriately selected patients (Figure 2)[8]. Lithotripsy after EUS-GBD in patients with cholelithiasis is an additional treatment strategy that is currently in its infancy but will undoubtedly be explored in a robust manner in the near future[9]. Above all, long-term safety, reproducibility, and the ability to train proceduralists in these evolving techniques will be paramount in driving progress of therapeutic biliary endoscopy.

Figure 2.

Potential approach to multidisciplinary management of acute cholecystitis. EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; GBD: Gallbladder drainage.

CONCLUSION

As the armamentarium of interventional endoscopy continues to grow, the definition of “failure” as it pertains to the ability to achieve endobiliary drainage will continue to evolve to the point where a majority of patients can be offered one of the many potential therapeutic modalities to achieve adequate biliary drainage, be it through the biliary tree or the gallbladder.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade C

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Nicolae N S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao YQ

Contributor Information

Faisal S Ali, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Huston, TX 77054, United States.

Sushovan Guha, Department of Clinical Sciences, Tilman J. Fertitta Family College of Medicine, University of Houston, Houston, TX 77204, United States. sguha@hrgastro.com.

References

- 1.Fujita R. The History of ERCP and EUS. In: Mine T, Fujita R. Advanced Therapeutic Endoscopy for Pancreatico-Biliary Diseases. Tokyo: Springer, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fugazza A, Khalaf K, Pawlak KM, Spadaccini M, Colombo M, Andreozzi M, Giacchetto M, Carrara S, Ferrari C, Binda C, Mangiavillano B, Anderloni A, Repici A. Use of endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage as a rescue approach in cases of unsuccessful biliary drainage. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:70–78. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen YI, Sahai A, Donatelli G, Lam E, Forbes N, Mosko J, Paquin SC, Donnellan F, Chatterjee A, Telford J, Miller C, Desilets E, Sandha G, Kenshil S, Mohamed R, May G, Gan I, Barkun J, Calo N, Nawawi A, Friedman G, Cohen A, Maniere T, Chaudhury P, Metrakos P, Zogopoulos G, Bessissow A, Khalil JA, Baffis V, Waschke K, Parent J, Soulellis C, Khashab M, Kunda R, Geraci O, Martel M, Schwartzman K, Fiore JF Jr, Rahme E, Barkun A. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Biliary Drainage of First Intent With a Lumen-Apposing Metal Stent vs Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in Malignant Distal Biliary Obstruction: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Study (ELEMENT Trial) Gastroenterology. 2023;165:1249–1261.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teoh AYB, Napoleon B, Kunda R, Arcidiacono PG, Kongkam P, Larghi A, Van der Merwe S, Jacques J, Legros R, Thawee RE, Saxena P, Aerts M, Archibugi L, Chan SM, Fumex F, Kaffes AJ, Ma MTW, Messaoudi N, Rizzatti G, Ng KKC, Ng EKW, Chiu PWY. EUS-Guided Choledocho-duodenostomy Using Lumen Apposing Stent Versus ERCP With Covered Metallic Stents in Patients With Unresectable Malignant Distal Biliary Obstruction: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial (DRA-MBO Trial) Gastroenterology. 2023;165:473–482.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundaram S, Dhir V. EUS-guided biliary drainage for malignant hilar biliary obstruction: A concise review. Endosc Ultrasound. 2021;10:154–160. doi: 10.4103/EUS-D-21-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kongkam P, Tasneem AA, Rerknimitr R. Combination of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage in malignant hilar biliary obstruction. Dig Endosc. 2019;31 Suppl 1:50–54. doi: 10.1111/den.13371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakai Y, Kogure H, Isayama H, Koike K. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Biliary Drainage for Unresectable Hilar Malignant Biliary Obstruction. Clin Endosc. 2019;52:220–225. doi: 10.5946/ce.2018.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irani SS, Sharzehi K, Siddiqui UD. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Role of EUS-Guided Gallbladder Drainage in Acute Cholecystitis: Commentary. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:1141–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quoraishi S, Ahmed J, Ponsford A, Rasheed A. Lessons learnt from a case of extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy for a residual gallbladder stone. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;32:43–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]