Abstract

BACKGROUND

Tuberculous peritonitis (TBP) is a chronic, diffuse inflammation of the peritoneum caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The route of infection can be by direct spread of intraperitoneal tuberculosis (TB) or by hematogenous dissemination. The former is more common, such as intestinal TB, mesenteric lymphatic TB, fallopian tube TB, etc., and can be the direct primary lesion of the disease.

CASE SUMMARY

We present an older male patient with TBP complicated by an abdominal mass. The patient's preoperative symptoms, signs and imaging data suggested a possible abdominal tumor. After surgical treatment, the patient's primary diagnosis of TBP complicating an intraperitoneal tuberculous abscess was established by combining past medical history, postoperative pathology, and positive results of TB-related laboratory tests. The patient's symptoms were significantly reduced after surgical treatment, and he was discharged from the hospital with instructions to continue treatment at a TB specialist hospital and to undergo anti-TB treatment if necessary.

CONCLUSION

This case report analyses the management of TBP complicated by intraperitoneal tuberculous abscess and highlights the importance of early definitive diagnosis in the hope of improving the clinical management of this type of disease.

Keywords: Abdominal mass, Tuberculous peritonitis, Intraperitoneal tuberculous abscess, Surgical treatment, Case report

Core Tip: We present an older male patient with tuberculous peritonitis (TBP) complicated by an abdominal mass. The patient's preoperative symptoms, signs and imaging data suggested a possible abdominal tumor. After surgical treatment, the patient's primary diagnosis of TBP complicated by an intraperitoneal tuberculous abscess was established by previous medical history, postoperative pathology and positive results of tuberculosis-related laboratory tests. Our aim is to report and analyze the diagnostic and therapeutic course of the disease and to highlight the importance of an early and definitive diagnosis in the hope of improving the clinical diagnosis and management of this type of disease.

INTRODUCTION

According to World Health Organization, 106 million people will develop tuberculosis (TB) in 2021, and 1.6 million people will die of TB in the same year (including 187000 people living with human immunodeficiency virus), in addition to a 3.6% increase in TB incidence in 2021 compared to 2020, which is a reversal of the downward trend of nearly 2% per year over the past 20 years[1]. Tuberculous peritonitis (TBP), which accounts for 0.10% to 3.50% of all TB cases and 4.0%–10.0% of all extrapulmonary TB, is a chronic, diffuse inflammation of the peritoneum caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis)[2]. The disease is more common in young and middle-aged people, with women slightly outnumbering men by 1.2–2.0, and women outnumbering men probably due to retrograde infection of pelvic TB[3]. Given the lack of specific symptoms of TBP and the need to differentiate it from a variety of abdominal diseases, there is often a lack of timely diagnosis and treatment leading to a high mortality rate of the disease[4].

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 72-year-old man was admitted to the Binzhou Medical University Hospital with abdominal pain and discomfort for > 1 month.

History of present illness

About 1 month ago, the patient had abdominal pain without any obvious cause, which was most obvious in the upper abdomen around the umbilicus. The abdominal pain was intermittent and dull, with no obvious radiating pain in the back and waist. The patient had no fever, nausea or vomiting, and no abdominal distension or diarrhea. Since the onset of the disease, the patient was clear and in good spirits, with normal diet, normal sleep, no significant change in body weight, and normal urination and defecation.

History of past illness

The patient had a history of exposure to TB 30 years ago and developed abdominal effusion. The patient had undergone surgery for heart valve disease and had been taking warfarin orally since the surgery.

Personal and family history

The patient denied any family history of malignant tumors.

Physical examination

On physical examination, the vital signs were as follows: Body temperature, 36.4 °C; blood pressure, 129 mmHg/66 mmHg; heart rate, 85 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 20 breaths per minute. His abdomen was flat, with no scarring, or gastric or intestinal pattern, no peristaltic wave, normal umbilicus, and no abdominal wall varices. His abdomen was soft, but there was a palpable hard abdominal mass on the right side of the umbilicus, about 6 cm 5 cm in size, with tenderness, poor mobility, and no abdominal compression. The liver was not palpable at the subcostal margin, and the gallbladder and spleen were not palpable. Abdominal mobile turbidity was negative, bowel sounds were normal at 4 beats/minute, and no vascular murmurs were heard in the abdomen.

Laboratory examinations

Erythrocyte count 3.5 1012/L (normal reference range: 4.3 1012/L–5.8 1012/L), hemoglobin 98 g/L (normal reference range: 130 g/L–175 g/L), hematocrit 31% (normal reference range: 40%–50%), lymphocyte percentage 15.4% (normal reference range: 20%–50%), neutrophil percentage 77.9% (normal reference range: 40%–75%), eosinophil percentage 0.3% (normal reference range: 0.4%–8%). The white blood cell count, platelet count, monocyte percentage, and eosinophil percentage were normal.

Total protein 60.50 g/L (normal reference range: 65 g/L–85 g/L), albumin 34.30 g/L (normal reference range: 40 g/L–55 g/L), lipoprotein A 55.05 mg/dL (normal reference range: 0 mg/dL–30 mg/dL), lactate dehydrogenase 305.80 U/L (normal reference range: 120 U/L–250 U/L), α-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase 205.70 U/L (normal reference range: 72 U/L–182 U/L), uric acid 183.0 μmol/L (normal reference range: 208 μmol/L–428 μmol/L). Glutamatergic aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, globulin, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, indirect bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, urea nitrogen, creatinine, and electrolytes were normal. Fibrinogen level was 4.4 g/L (normal reference range: 2 g/L–4 g/L). Prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time and D-dimer quantification were normal. Carcinoembryonic antigen was negative.

Imaging examinations

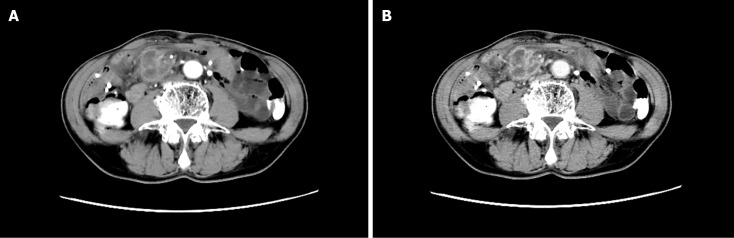

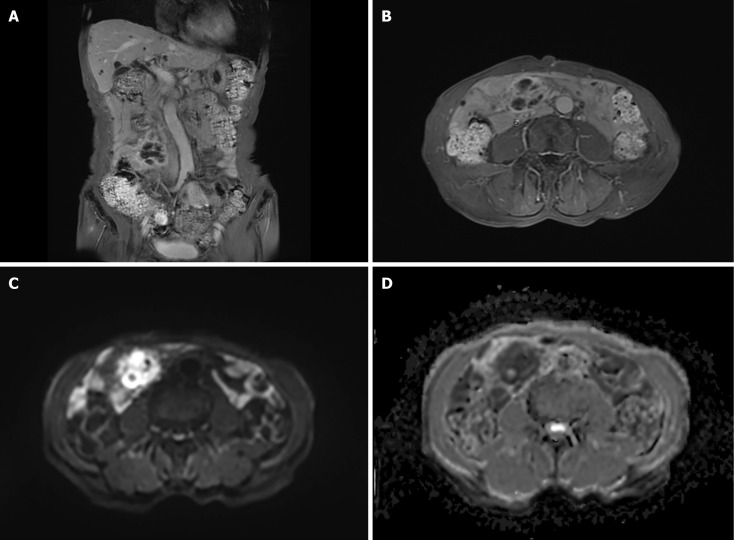

Enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen at the local hospital suggested a right lower abdominal mass, and scattered multiple nodules in the abdominal cavity (Figure 1A and B). Magnetic resonance (MR) dynamic enhancement + diffusion-weighted imaging of the upper abdomen suggested abnormally enhanced foci in the right lower abdominal cavity (Figure 2A–D) and further examination was recommended. An abnormal signal in the liver was indicative of multiple hepatic cysts and further review was recommended. There was a small right renal cyst and bilateral small pleural effusion.

Figure 1.

Enhanced computed tomography. A: Arterial phase; B: Venous phase. They showed a right lower abdominal mass with scattered multiple nodules in the abdominal cavity.

Figure 2.

Different sequences of magnetic resonance dynamic enhancement + diffusion-weighted imaging of the lower abdomen. A: T1_quick3d_cor_fs_bh; B: T1_quick3d_tra_fs_bh; C: Epi_dwi_tra_trig_b800; D: Epi_dwi_tra_trig_ADC. They showed abnormally enhanced foci of the right lower abdominal cavity of an undetermined nature.

FURTHER DIAGNOSTIC WORK-UP

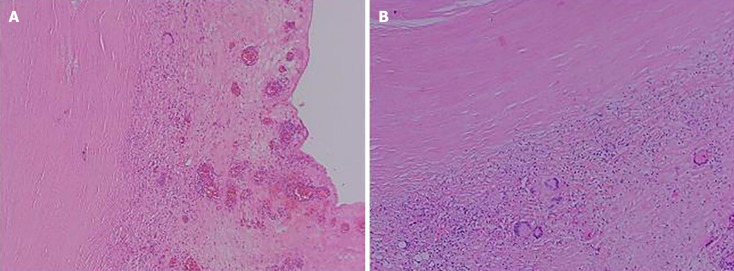

After ruling out contraindications for surgery, the patient underwent laparoscopic exploration on January 1, 2024. During the operation, the mass was incised and drained, and part of the mass tissues and several surrounding nodules were excised and sent for pathological examination. Postoperatively, T-cell test for TB infection, and nucleic acid test for M. tuberculosis (constrained proportional assignment method) were positive, and antacid staining was negative, and no antacid bacilli were seen. Postoperative pathology of the abdominal mass and intra-abdominal nodule suggested peripheral fibrotic tissue proliferation combined with multinucleated giant cell reaction (Figure 3A and B).

Figure 3.

Postoperative pathology. A: Abdominal mass; B: Intra-abdominal nodule. They showed peripheral fibrotic tissue proliferation with multinucleated giant cell reaction (hematoxylin and eosin, 100 ×).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Combined with the past medical history, postoperative pathology and positive results of TB-related laboratory tests, the patient's primary diagnosis was determined to be TBP complicated by intraperitoneal tuberculous abscess.

TREATMENT

Anti-inflammatory, rehydration, dressing change, nutritional support and other treatments were given after the operation. The patient's symptoms were significantly reduced after treatment, and no obvious abnormalities were found in the routine blood tests and biochemistry, so he was discharged with instructions to go to a TB specialist hospital for further treatment and anti-TB therapy if necessary.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

More than 1 month after surgery, the patient is on anti-TB treatment.

DISCUSSION

Patients with TBP often have comorbid TB infection in other organs. TBP is an insidious disease with subacute manifestations and is difficult to diagnose if it is not suspected.

Clinical history has revealed that most patients have a history and present with symptoms of TB, including low afternoon fever, night sweats, malaise, poor appetite, and emaciation[5]. Some studies have reported that the two most common symptoms of TBP are abdominal pain (31%–94%) and fever (45%–100%)[3,6-9]. The average duration of symptoms from onset to consultation extends from weeks to months[3,10]. Physical examination of patients with TBP usually reveals ascites (73%) and abdominal tenderness (47.7%), while a typical "doughy" abdomen is rare (5%–13%)[3,9]. In addition to this, low-grade fever, weight loss, abdominal distension, elevated carbohydrate antigen-125 levels, and abdominal masses are also common clinical manifestations in patients with TBP[11]. The vast majority of reported cases were initially misdiagnosed as tumor or carcinoma, and only confirmed by surgical treatment and postoperative pathology[12-16]. Therefore, it is difficult to make a definitive diagnosis from clinical features alone, and targeted ancillary tests are important for the early diagnosis and treatment of TBP. In this paper, we report the patient had only two clinical manifestations, abdominal pain and abdominal mass. The patient was an older man, which is not consistent with the epidemiology of TBP, and he concealed a history of exposure to TB before surgery, which made it difficult to diagnose the case.

Blood analysis, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and tuberculin test show that some patients have mild to moderate anemia, mostly normocytic normochromic. Leukocyte counts are mostly normal and increased in caseous patients or in those with acute spread of abdominal tuberculous foci. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate is increased in most patients and can be an indicator of active disease. A strong positive tuberculin test helps with the diagnosis of TB infection.

Ascites examination may show straw yellow exudate, a few being pale blood in color, specific gravity is usually more than 1.018, and protein content is more than 30 g/L, mainly lymphocytes. However, sometimes due to hypovitaminosis or combined cirrhosis, the nature of ascites fluid can resemble leakage fluid. If ascites glucose < 3.4 mmol/L and pH < 7.35, it suggests bacterial infection. If ascites adenosine deaminase activity is increased, it suggests TBP.

Ultrasound, CT and magnetic resonance imaging show thickened peritoneum, ascites, intra-abdominal masses and fistula. Scattered calcified shadows of mesenteric lymph nodes can be seen on abdominal ultrasound. Gastrointestinal x-ray barium meal examination can identify intestinal adhesions, intestinal TB, intestinal fistula, mass outside the intestinal lumen, and other signs.

Laparoscopy shows that the visceral surface of the peritoneum and omentum can have seen scattered or aggregated grey–white nodules. Laparoscopic biopsy is valuable in confirming the diagnosis of TBP. This examination is generally applicable to patients with free ascites, but is contraindicated in patients with extensive peritoneal adhesions. Laparoscopy has become the main diagnostic modality for TBP[17-21]. Typical microscopic manifestations include extensive intra-abdominal adhesions; thickening of the peritoneum and omentum with ascites; multiple scattered yellowish-white nodules; and calcified lymph nodes in the retroperitoneum and retro-omentum[3,22,23]. Statistical analysis of data from 402 patients in 11 studies reported high sensitivity (93%) and specificity (98%) of laparoscopy for diagnosis of TBP[3]. Although laparoscopic surgery may lead to complications such as bowel perforation, bleeding, infection and even death, these complications are rare, occurring in < 3% of cases[5]. Laparoscopy allows clear visualization of the shape and volume of the abdominal cavity and acquisition of tissues, such as peritoneum or nodules, for diagnosis. However, in the diagnosis of TBP, laparoscopy is mainly indicated in patients with unknown etiology but high suspicion of TBP. In addition, performing laparoscopy requires consideration of the patient's financial status and the availability of the hospital for the procedure. Therefore, a combination of other noninvasive examination methods should be considered for diagnosis before laparoscopy is performed.

Early diagnosis and treatment of TBP are important to improve the patient's condition, and some studies have noted that delayed anti-TB treatment is associated with high mortality[4]. Current TBP treatment follows that for extrapulmonary TB, with systemic anti-TB drug therapy as the mainstay, supplemented by nutritional support and abdominal local therapy. The principles of treatment are to adhere to early, combined, standardized anti-TB drugs and to strengthen systemic supportive therapy, to achieve complete cure, avoid recurrence and prevent complications. Strengthening supportive therapy includes: Bed rest, high protein, high calorie, high vitamin and easy-to-digest diet, daily supplementation of fresh fruits and milk, intravenous infusion when needed, and regular injection of albumin. Anti-TB drugs: Usually, three or four drugs are used for intensive treatment. Isoniazid 0.3 g–0.4 g, daily morning dose; rifampicin 0.45 g, once a day orally; ethambutol 0.75 g once a day orally. If necessary, streptomycin 0.75 g once daily intramuscularly or pyrazinamide 0.25 g–0.5 g three times daily can be added. Combined treatment with four drugs for 2 months, and then continued treatment with isoniazid and rifampicin for at least 7 months. For those with hematogenously disseminated lesions or significant TB toxemia, short-term treatment with prednisone can be added to anti-TB drugs, with 30 mg/d–40 mg/d, orally in divided doses.

For patients who have obvious exudative type ascites, the fluid can be drained once a week, followed by intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg isoniazid and 0.25 g streptomycin.

Surgical treatment is limited to patients with complete intestinal obstruction, intestinal fistula or complications of intestinal perforation[24,25]. When the disease is difficult to diagnose and cannot be differentiated from intra-abdominal tumor or some causes of acute abdomen, a cesarean section may be considered.

CONCLUSION

The final diagnosis of our case was TBP complicated by intraperitoneal tuberculous abscess. When an abdominal tumor is suspected, we should ask patients whether they have a history of TB or contact with someone else with TB. This will help to diagnose and treat more accurately, avoid missed diagnosis or misdiagnosis, and improve the therapeutic effect and prognosis of the patient.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed consent is obtained from all participants. Written informed consent is obtained from the patient to publish the case report and accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade D

Novelty: Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade C

P-Reviewer: Demetrashvili Z S-Editor: Luo ML L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao YQ

Contributor Information

Wei-Peng Liu, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Binzhou Medical University Hospital, Binzhou 256603, Shandong Province, China.

Feng-Zhen Ma, Department of Gastroenterology, Binzhou Medical University Hospital, Binzhou 256603, Shandong Province, China.

Zhou Zhao, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Binzhou Medical University Hospital, Binzhou 256603, Shandong Province, China.

Zong-Rui Li, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Binzhou Medical University Hospital, Binzhou 256603, Shandong Province, China.

Bao-Guang Hu, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Binzhou Medical University Hospital, Binzhou 256603, Shandong Province, China.

Tao Yang, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Binzhou Medical University Hospital, Binzhou 256603, Shandong Province, China. ytwcwk123@163.com.

References

- 1.Bagcchi S. WHO's Global Tuberculosis Report 2022. Lancet Microbe. 2023;4:e20. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00359-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu N, Xu Z, Huang WF. Tuberculous peritonitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2024;56:367–368. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2023.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanai FM, Bzeizi KI. Systematic review: tuberculous peritonitis--presenting features, diagnostic strategies and treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:685–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow KM, Chow VC, Hung LC, Wong SM, Szeto CC. Tuberculous peritonitis-associated mortality is high among patients waiting for the results of mycobacterial cultures of ascitic fluid samples. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:409–413. doi: 10.1086/341898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaid U, Kane GC. Tuberculous Peritonitis. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5 doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.tnmi7-0006-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan KK, Chen K, Sim R. The spectrum of abdominal tuberculosis in a developed country: a single institution's experience over 7 years. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:142–147. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0669-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen HL, Wu MS, Chang WH, Shih SC, Chi H, Bair MJ. Abdominal tuberculosis in southeastern Taiwan: 20 years of experience. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108:195–201. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muneef MA, Memish Z, Mahmoud SA, Sadoon SA, Bannatyne R, Khan Y. Tuberculosis in the belly: a review of forty-six cases involving the gastrointestinal tract and peritoneum. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:528–532. doi: 10.1080/003655201750153412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demir K, Okten A, Kaymakoglu S, Dincer D, Besisik F, Cevikbas U, Ozdil S, Bostas G, Mungan Z, Cakaloglu Y. Tuberculous peritonitis--reports of 26 cases, detailing diagnostic and therapeutic problems. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:581–585. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200105000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang B, Cui DJ, Ren Y, Han B, Yang P, Zhao X. Comparison between laparoscopy and laboratory tests for the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis. Turk J Med Sci. 2018;48:711–715. doi: 10.3906/sag-1512-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu CH, Changchien CC, Tseng CW, Chang HY, Ou YC, Lin H. Disseminated peritoneal tuberculosis simulating advanced ovarian cancer: a retrospective study of 17 cases. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;50:292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bilgin T, Karabay A, Dolar E, Develioğlu OH. Peritoneal tuberculosis with pelvic abdominal mass, ascites and elevated CA 125 mimicking advanced ovarian carcinoma: a series of 10 cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2001;11:290–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2001.011004290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozalp S, Yalcin OT, Tanir HM, Kabukcuoglu S, Akcay A. Pelvic tuberculosis mimicking signs of abdominopelvic malignancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2001;52:71–72. doi: 10.1159/000052945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahdavi A, Malviya VK, Herschman BR. Peritoneal tuberculosis disguised as ovarian cancer: an emerging clinical challenge. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;84:167–170. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaidi SN, Conner M. Disseminated peritoneal tuberculosis mimicking metastatic ovarian cancer. South Med J. 2001;94:1212–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thakur V, Mukherjee U, Kumar K. Elevated serum cancer antigen 125 levels in advanced abdominal tuberculosis. Med Oncol. 2001;18:289–291. doi: 10.1385/MO:18:4:289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rai S, Thomas WM. Diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis: the importance of laparoscopy. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:586–588. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.12.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu JF, Li HJ, Lee PI, Ni YH, Yu SC, Chang MH. Tuberculous peritonitis mimicking peritonitis carcinomatosis: a case report. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162:853–855. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1319-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lal N, Soto-Wright V. Peritoneal tuberculosis: diagnostic options. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1999;7:244–247. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-0997(1999)7:5<244::AID-IDOG7>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouma BJ, Tytgat KM, Schipper HG, Kager PA. Be aware of abdominal tuberculosis. Neth J Med. 1997;51:119–122. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(97)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Protopapas A, Milingos S, Diakomanolis E, Elsheikh A, Protogerou A, Mavrommatis K, Michalas S. Miliary tuberculous peritonitis mimicking advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2003;56:89–92. doi: 10.1159/000072919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandikçi MU, Colakoglu S, Ergun Y, Unal S, Akkiz H, Sandikçi S, Zorludemir S. Presentation and role of peritoneoscopy in the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1992;7:298–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1992.tb00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chow KM, Chow VC, Szeto CC. Indication for peritoneal biopsy in tuberculous peritonitis. Am J Surg. 2003;185:567–573. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(03)00079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rasheed S, Zinicola R, Watson D, Bajwa A, McDonald PJ. Intra-abdominal and gastrointestinal tuberculosis. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:773–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan AR, Morris LM, Keswani SG, Khan IR, Le L, Lee WC, Hunt JP. Tuberculous peritonitis: a surgical dilemma. South Med J. 2009;102:94–95. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318186e684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]