Abstract

Background

Since influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) carry significant burden in older adults with overlapping seasonality, vaccines for both pathogens would ideally be coadministered in this population. Here we evaluate the immunogenicity and safety of concomitant administration of Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein and high-dose seasonal influenza vaccine (Fluzone-HD) in adults ≥65 years old.

Methods

Participants were randomized 1:1 to the Coadministration or Control group. The Coadministration group received concomitant Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein and Fluzone-HD on day 1 and placebo on day 29, while the Control group received Fluzone-HD and placebo on day 1 and Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein on day 29. Influenza hemagglutination-inhibiting and RSV preF–binding antibody titers were measured postvaccination and tested for noninferiority between both groups. Safety data were collected throughout the study and analyzed descriptively.

Results

Coadministered Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein and Fluzone-HD vaccines induced noninferior immune responses compared to each vaccine administered alone. Seroconversion and seroprotection rates against influenza were similar between groups. Both vaccines remained well tolerated upon concomitant administration.

Conclusions

Coadministration of Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein and Fluzone-HD showed an acceptable safety profile and did not hamper the immunogenicity of either vaccine, thus supporting that both vaccines can be concomitantly administered in adults ≥65 years old.

Keywords: respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein, Fluzone-HD, noninferiority

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza vaccines would ideally be coadministered in adults ≥65 years. Coadministration of an RSV vaccine candidate (Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein) and Fluzone-HD had an acceptable safety profile and did not hamper the immunogenicity of either vaccine.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza are known to cause significant burden among older adults [1–3]. In 2019, approximately 5.2 million cases, 470 000 hospitalizations, and 33 000 in-hospital RSV-associated deaths occurred among adults ≥60 years in high-income countries [1]. Other meta-analyses have reported similar RSV infection and fatality rates in developed countries [2, 3], whereas data from low-income countries are lacking [1–3].

In 2016, influenza was estimated to cause 16 million lower respiratory tract infections and 2.8 million hospitalizations globally among adults aged ≥65 years [4, 5]. Thus, older adults would benefit from effective therapeutic and preventive measures against both pathogens.

Since the seasonality of influenza and RSV frequently overlap in a geographic region [6], vaccines for both pathogens could be coadministered to ease implementation of RSV vaccination. A seasonal influenza vaccine (Fluzone High Dose Quadrivalent® [Fluzone-HD]) containing a dose 4 times higher than the standard influenza vaccine has been recommended for adults aged ≥65 years in several countries [7–9]. This study evaluated the immunogenicity, reactogenicity, and safety of coadministration of Fluzone-HD and Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein, an adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) vector–based RSV candidate vaccine encoding a pre-fusion conformation-stabilized RSV fusion protein (preF), in adults aged ≥65 years. Noninferiority was tested to ensure that immunogenicity of either vaccine was not compromised with coadministration.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, phase 3 study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT05071313; registered 8 October 2021) to evaluate immunogenicity and safety of Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein coadministered with Fluzone-HD (CoAd group) compared with each vaccine administered separately 28 days apart (Control group) in adults aged ≥65 years (Figure 1). The CoAd group received Fluzone-HD in the right arm on day 1, Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein in the left arm on day 1, and placebo in the left arm on day 29. The Control group received Fluzone-HD in the right arm on day 1, placebo in the left arm on day 1, and Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein in the left arm on day 29. The arms receiving Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein are subsequently called the RSV arm, those receiving Fluzone-HD the Flu arm, and those receiving placebo the placebo arm. Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein and placebo were administered in a blinded manner, while Fluzone-HD was administered open-label. Vaccinations were administered intramuscularly in the deltoid muscle.

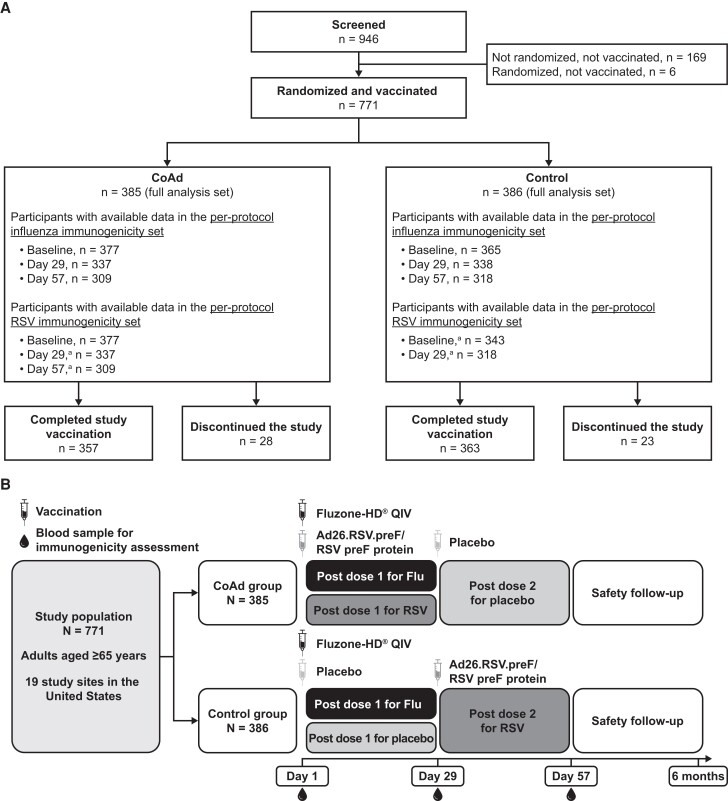

Figure 1.

Participant disposition (A) and study design (B). The 2 most common causes of study discontinuation were withdrawal of subject consent and loss to follow-up. Immunogenicity assessments were performed on the per-protocol influenza immunogenicity (PPII) and per-protocol respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) immunogenicity (PPRI) sets (A). PPII consisted of all randomized participants who received at least the first study vaccination, while PPRI encompassed those in the Coadministration (CoAd) group who received the first study vaccination and those in the Control group who received the second study vaccination. Participants included in the PPII and PPRI sets did not experience any major protocol deviations expected to impact immunogenicity outcomes, including out-of-window sample collection. Participants in the PPII and PPRI sets had data available for ≥1 of the influenza vaccine strains or RSV immunogenicity, respectively. Day 1, 29, and 57 visits were on-site visits, while month 6 follow-up was performed by phone. Besides these visits, there were also phone calls performed 7 days after each vaccination as a part of safety follow-up (B). Abbreviations: Ad26, adenovector 26; Flu, Fluzone-HD vaccine; HD, high-dose; preF, prefusion conformation-stabilized RSV F protein; QIV, quadrivalent influenza vaccine. aTiming relative to vaccination with Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein.

The planned total sample size was approximately 750 participants, randomized 1:1 in parallel. The study was composed of screening on day 1, vaccination for each participant on days 1 and 29 with a 28-day follow-up period after each vaccination, and a safety follow-up for serious adverse events (SAEs) and potential adverse events of special interest (AESIs) for 6 months after the second vaccination. The primary objectives were to demonstrate noninferiority of the antibody response against RSV and against the 4 influenza vaccine strains between the CoAd and Control groups. Safety and reactogenicity of Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein and Fluzone-HD in both CoAd and Control groups, as well as seroconversion and seroprotection rates for the 4 influenza vaccine strains, were analyzed descriptively as secondary objectives.

The study was approved by an institutional review board and performed in compliance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki, and national regulatory requirements. Potential safety issues were escalated to an independent data monitoring committee. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participating.

Study Population

This study enrolled adults aged ≥65 years who were in stable health according to the investigator's judgment and had not received a seasonal influenza vaccine for the 2021–2022 influenza season in the Northern Hemisphere. Participants could have underlying illnesses, such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipoproteinemia, or hypothyroidism, if their signs/symptoms were stable at the time of vaccination.

Study Vaccines

The Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccine contained 2 active components: Ad26.RSV.preF (1 × 1011 viral particles) and RSV preF protein (150 µg), both manufactured by Janssen Vaccines and Prevention B.V. Components were provided to sites in 2 separate vials and mixed into a single 1.0-mL injection prior to administration. Placebo was 0.9% saline (1.0 mL). Fluzone-HD, formulated for the 2021–2022 influenza season, was supplied in a 0.7-mL single-dose prefilled syringe. Each Fluzone-HD dose contained 240 µg of hemagglutinin, with 60 µg each from 4 influenza vaccine strains (2 influenza A strains [A/Victoria/2570/2019 IVR-215 and A/Tasmania/503/2020 IVR-221] and 2 influenza B strains [B/Washington/02/2019 and B/Phuket/3073/2013]). For quadrivalent vaccines, A/Cambodia/e0826360/2020 (H3N2)-like virus was recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for use in the 2021–2022 Northern Hemisphere influenza season [10], but use of a similar strain, A/Tasmania/503/2020 IVR-221, was considered acceptable according to European Medicines Agency recommendations [11].

Randomization

All participants were randomly assigned 1:1 to the CoAd or Control group using an interactive web response system prepared under sponsor supervision. Randomization was balanced using randomly permuted blocks and stratified by age (65–74 years, 75–84 years, and ≥85 years).

Immunogenicity Assessments

Blood samples were collected prevaccination and at 28 days after each study vaccination. Vaccine-induced immune responses against influenza vaccine strains (ie, A/Victoria, A/Tasmania, B/Washington, and B/Phuket) were evaluated using a validated hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assay [12] per WHO guidelines using turkey red blood cells and formalin-inactivated influenza viral antigen 21/116 as the target [13, 14]. A titer of 10 was used as the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) for each of the HI assays for each influenza vaccine strain. Reported values were calculated as geometric mean of 2 replicates. Seroconversion was defined for each of the 4 influenza vaccine strains as an HI antibody titer at day 29 ≥1:40 in participants with a prevaccination HI titer of <1:10 or a ≥4-fold HI titer increase in participants with a prevaccination HI titer of ≥1:10. Seroprotection was defined as an HI antibody titer at day 29 ≥1:40. Vaccine-induced immune responses against RSV were assessed using a validated RSV preF A immunoglobulin G (IgG) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay that measures binding antibody concentrations against the preF protein of RSV subtype A [15]. The LLOQ for this assay was 3.4 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay units per liter.

Safety Assessments

Participants were monitored for acute reactions for ≥15 minutes after each vaccination. Adverse events (AEs), vital signs, and any abnormal physical examination findings were documented and evaluated according to US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines [16]. Solicited AEs were reported for 7 days following each vaccination. Unsolicited AEs were recorded up to 28 days postvaccination. SAEs, AESIs, and potential AESIs were evaluated and followed up throughout the course of the study (ie, 6 months postvaccination). Thrombosis and thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS), also known as vaccine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT), was considered an AESI.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size was calculated assuming the following: coadministration of Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein and Fluzone-HD would have no effect on the immune response against both vaccines; the standard deviation for day 29 HI antibody titers against each of the influenza vaccine strains was 2.1 at the log2 scale [17]; the standard deviation for RSV preF A IgG 28 days after RSV administration was 1.1 at the log2 scale [18]; a noninferiority margin of 1.5 (based on US FDA guidance for influenza vaccines) [19]; and a 2-sided type I error of 5%. A total of 330 evaluable participants per group would result in an overall power of ≥80% to show (1) noninferiority in HI antibody titers against each of the influenza vaccine strains at 28 days after coadministration of Fluzone-HD and Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein relative to the administration of Fluzone-HD alone as well as (2) noninferiority in RSV preF A IgG titers at 28 days after coadministration of Fluzone-HD and Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein relative to administration of Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein alone. An additional 45 participants were added per group to account for data exclusions, dropouts, and missing samples, for a total sample size target of 750 participants. Immunogenicity assessments were performed on the per-protocol influenza immunogenicity (PPII) and per-protocol RSV immunogenicity (PPRI) sets as defined in Figure 1. Safety assessments were performed on the full analysis set (ie, all participants receiving ≥1 study vaccination, regardless of the occurrence of protocol deviations and study vaccinations [Fluzone-HD, Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein, or placebo]).

Noninferiority was tested by calculating 2-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for (1) the difference in log-transformed HI antibody titers for each of the influenza vaccine strains between the 2 groups, CoAd and Control; and (2) the difference in log-transformed RSV preF A IgG titers between CoAd and Control. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) model was fitted with the respective log-transformed HI or RSV preF A IgG titers as a dependent variable and group (CoAd and Control) and age category as independent variables. Based on these ANOVA models, CIs around the difference were calculated and subsequently back-transformed to CIs around a geometric mean titer (GMT) ratio (GMT Control group/GMT CoAd group) and compared to the noninferiority margin of 1.5. If the upper bound of the 2-sided 95% CI for the GMT ratio was <1.5 for each of the 4 influenza vaccine strains’ HI and for RSV preF–binding antibodies, noninferiority between CoAd and Control groups could be concluded for both vaccines. Three sensitivity analyses were performed: an analysis adjusting for baseline titers with log2-transformed baseline HI antibody titers added as independent variables to the model, an analysis with Welch's ANOVA (allowing unequal variances between groups), and an evaluation using the full analysis set. Proportions of participants seroconverted and seroprotected against influenza in the CoAd and Control groups were analyzed descriptively.

AEs were coded according to Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 24.1, and analyzed descriptively. No formal statistical testing of safety assessments was performed.

RESULTS

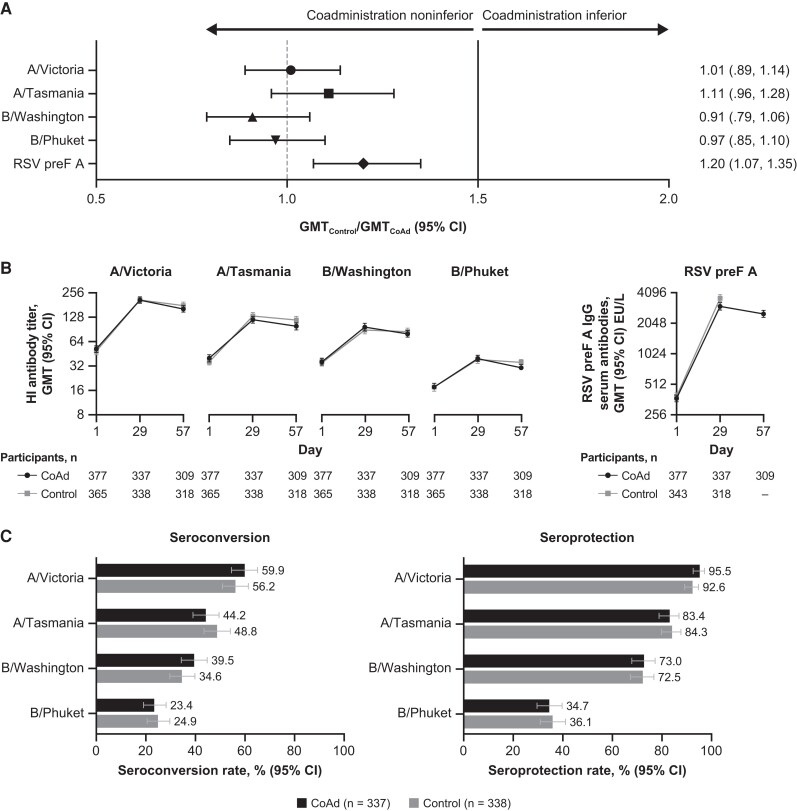

Altogether, 771 participants were randomized and received ≥1 dose of study vaccine (385 participants in the CoAd group; 386 in the Control group; Figure 1). Demographic and baseline characteristics of the participants were generally balanced between groups (Supplementary Table 1). Overall, 55.9% were female, 80.9% were 65–74 years of age, 79.5% were overweight or obese (body mass index ≥25 kg/m2), and 18.7% were at increased risk of acquiring severe RSV disease. Conditions known to increase one's risk of severe RSV disease (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition) included congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease (eg, angina pectoris, ischemic cardiomyopathy, history of myocardial infarct, or history of coronary artery bypass graft or coronary artery stent), and chronic lung disease (eg, asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) [20]. Noninferiority analyses were performed on the PPII set for HI antibody titers and on the PPRI set for RSV preF A IgG (Figure 1). HI titers from 9.9% of participants collected 28 days post–Fluzone-HD vaccination and RSV preF A IgG titers from 10.3% of participants collected 28 days post–Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccination were excluded from the PPII and PPRI sets, respectively, either due to out-of-window collection or other major protocol deviations. The 95% CI upper limits of the GMT ratios of HI antibody titers and RSV preF A IgG titers were below the predefined 1.5 noninferiority margin, demonstrating a noninferior vaccine-induced immune response between those receiving coadministration of Fluzone-HD and Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein compared with those receiving each vaccine separately (Figure 2A, Supplementary Table 2). Sensitivity analyses also supported noninferiority (Supplementary Table 3). Day 29 HI antibody titers against each influenza vaccine strain and RSV preF A IgG titers 28 days after RSV vaccination showed comparable increases in both groups (Figure 2B, Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). Seroconversion and seroprotection rates against the influenza vaccine strains were similar between those receiving Fluzone-HD and Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein concomitantly and those receiving Fluzone-HD alone (Figure 2C). Seroconversion rates ranged between 23.4% and 59.9%, and seroprotection rates ranged between 34.7% and 95.5%, with the lowest titers observed against the B/Phuket strain and the highest titers observed against the A/Victoria strain.

Figure 2.

Noninferiority analyses for hemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibody responses and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) preF A immunoglobulin G (IgG) (A), geometric mean titer (GMT) of HI and RSV preF A IgG antibodies (B), and percentage of seroconversion and seroprotection rates in the Coadministration (CoAd) and Control groups (C). An analysis of HI antibody titers was conducted using the per-protocol influenza immunogenicity set, while that on RSV preF A IgG was using the per-protocol RSV immunogenicity set. Noninferiority was achieved as the 95% confidence interval (CI) upper limits of the geometric mean ratio of the HI antibody titers, and the RSV preF A IgG titers were below the predefined 1.5 margin (A). GMTs of HI and RSV preF A IgG antibodies at baseline, day 29, and day 57 were plotted. It is important to note that, in the Control group, the participants received Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccine at day 29; thus, the day 29 samples of this participant were plotted at day 1 (baseline), and the day 57 samples were plotted at day 29 to allow comparison with the CoAd group. Following the study design, no samples were collected 56 days post–Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccination in the Control group (B). Seroconversion is defined as an HI antibody titer at 28 days postvaccination ≥1:40 in participants with a prevaccination HI titer of <1:10 or a ≥4-fold HI titer increase in participants with a prevaccination HI titer of ≥1:10. Seroprotection was defined as HI antibody titer at 28 days postvaccination ≥1:40 (C). Abbreviations: Ad26, adenovector 26; EU, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay units; preF, prefusion conformation-stabilized RSV F protein.

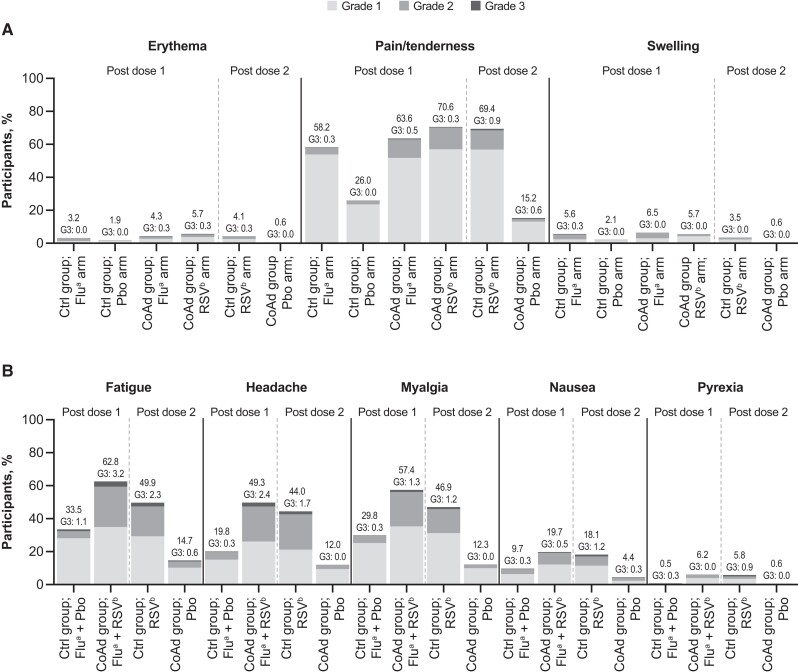

Both Fluzone-HD and Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein induced solicited local AEs, with injection-site pain being the most frequent (Figure 3A, Table 1). The frequency of solicited local AEs in the RSV arm was similar between the CoAd (70.9%) and Control (70.3%) groups. Solicited local AEs were less common in the Flu arm (CoAd: 63.9%; Control: 58.7%). Solicited local AEs occurred with the least frequency in placebo arms, though these were more frequent when administered together with Fluzone-HD (26.3%) than when administered alone (15.5%). The median duration of local AEs in the RSV arm was 2–3 days in the CoAd group and 2–4 days in the Control group, while in the Flu arm, it was 1–2 days in both groups. Grade 3 solicited local AEs were minimal (0.5%–1.21%) in all arms. Three participants in the CoAd group reported injection-site pain lasting >10 days: 1 participant in the RSV arm had a grade 3 event, 1 participant in the RSV arm had a grade 1 event, and 1 participant in the RSV and Flu arms had two grade 1 events. No grade 4 solicited local AEs were reported.

Figure 3.

The percentage of solicited local (A) and systemic (B) adverse events (AEs) reported during the 7-day postvaccination period by worst severity grade. The analysis was performed using the full analysis set (ie, all participants who received ≥1 study vaccination, regardless of protocol deviations). No grade 4 solicited local or systemic AEs were recorded. Post dose 1 represented the period after receiving the first study vaccination, while post dose 2 represented the period after receiving the second dose. Abbreviations: Ad26, adenovector 26; CoAd, Coadministration group; Ctrl, Control group; Flu, Fluzone-HD vaccine; G3, grade 3; HD, high-dose; Pbo, placebo; preF, prefusion conformation-stabilized RSV F protein; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus. aDenotes participants who received the Fluzone-HD vaccine. bDenotes participants who received the Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccine.

Table 1.

Summary of AEsa in the Full Analysis Set

| CoAd Group | Control Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Vaccination: Flub + RSVc | 2nd Vaccination: Placebo | 1st Vaccination: Flub + Placebo | 2nd Vaccination: RSVc | |

| Participants receiving ≥1 dose, No. | 385 | 357 | 386 | 363 |

| Participants receiving ≥1 dose with solicited AE data available, No. | 371 | 341 | 373 | 343 |

| Grade 3 solicited local AEsd, No. (%) | Flua arm: 3 (0.8) RSVc arm: 2 (0.5) |

2 (0.6) | Flua arm: 2 (0.5) Placebo arm: 0 |

4 (1.2) |

| Grade 3 solicited systemic AEsd, No. (%) | 17 (4.6) | 3 (0.9) | 5 (1.3) | 14 (4.1) |

| Unsolicited AEse, No. (%) | 58 (15.1) | 33 (9.2) | 60 (15.5) | 35 (9.6) |

| Related to study vaccine | 17 (4.4) | 3 (0.8) | 6 (1.6) | 15 (4.1) |

| Grade ≥3 | 8 (2.1) | 2 (0.6) | 11 (2.8) | 2 (0.6) |

| SAEse,f,g, No. (%) | 13 (3.4) | 11 (2.8) | ||

| Related to study vaccine | 0 | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Potential AESIs (programmed search)e,f, No. (%) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.5) | ||

| Related to study vaccine | 0 | 0 | ||

| AESIs | 0 | 0 | ||

Abbreviations: Ad26, adenovector 26; AE, adverse event; AESI, adverse event of special interest; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CoAd, Coadministration; Flu, Fluzone-HD vaccine; HD, high-dose; preF, prefusion conformation-stabilized RSV F protein; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; QIV, quadrivalent influenza vaccine; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SAE, serious adverse event; TTS, thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome.

aParticipants were counted only once for any given event, regardless of the number of times they experienced the event. For participants with multiple instances of the same event, the event with the worst toxicity grading was reported.

bFluzone-HD QIV vaccine.

cAd26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccine.

dFor solicited local and systemic AEs, the number of participants with solicited AE data available was used as the denominator.

eFor unsolicited AEs, SAEs, and potential AESIs, the number of participants receiving ≥1 dose of study vaccine was used as the denominator.

fFor SAEs and potential AESIs, the number of participants receiving the first dose of study vaccine in the full analysis set was used as the denominator.

gAny thrombotic AEs and/or thrombocytopenia were considered potential AESIs. Potential AESIs were identified through 2 distinct processes: prospective reporting by the investigator and regular retrospective screening of AEs meeting the definition of potential AESIs using Standardized MedDRA Queries. Cases with concurrent thrombocytopenia and thrombosis were considered “qualified for assessment.” The cases were further classified by a TTS adjudication committee consisting of internal and external experts by level of certainty for TTS according to Brighton Collaboration [21], Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee, and CDC case definitions [22], and were assessed for relatedness to the vaccine.

Solicited systemic AEs were more frequently reported in participants receiving concomitant Fluzone-HD and Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein (76.8%) compared with those receiving Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein (63.6%), Fluzone-HD (48.5%), or placebo alone (23.5%) (Figure 3). This trend was observed in each solicited systemic AE (ie, fatigue, headache, myalgia, nausea, and fever). The use of analgesics and antipyretics was similar between those receiving both vaccines concomitantly (29.9%) and those receiving Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein (26.2%) alone, and lower in those receiving Fluzone-HD (9.8%) or placebo alone (4.5%). Solicited systemic AEs were mostly grades 1 and 2. Fatigue was the most common solicited systemic AE, reported in 62.8% of those receiving both vaccines concomitantly (CoAd group), 49.9% of those receiving Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccine alone (Control group), 33.5% of those receiving Fluzone-HD vaccine alone (Control group), and 14.7% of those receiving placebo alone (CoAd). The majority of solicited systemic AEs were deemed related to study vaccine by the investigators. The median duration of systemic AEs was 1–2 days after receiving both vaccines concomitantly (CoAd group), 1–2 days after receiving Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccine alone (Control group), 1–1.5 days after receiving Fluzone-HD vaccine alone (Control group), and 1–1.5 days after receiving placebo alone (CoAd group). Grade 3 solicited systemic AEs were comparably reported among those receiving both vaccines concomitantly (4.6%) and Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein alone (4.1%), with fatigue being the most frequent. Grade 3 solicited systemic AEs were less commonly reported among those who only received Fluzone-HD (1.3%) or placebo (0.9%). Two participants reported solicited systemic AEs that lasted >10 days (ie, 1 participant in the Control group reported grade 2 myalgia post–Fluzone-HD administration and grade 1 fatigue and grade 1 myalgia post–Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein administration; another participant in the CoAd group reported grade 2 headache and grade 1 myalgia after receiving both vaccines concomitantly). No grade 4 solicited systemic AEs were reported.

Unsolicited AEs were equally reported between those receiving Fluzone-HD and Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein concomitantly (15.1%) and those receiving Fluzone-HD alone (15.5%), and less frequently reported in those receiving Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein alone (9.6%) or placebo (9.2%) (Table 1). Most unsolicited AEs were either grade 1 or 2 in severity and were not considered related to study vaccine by the investigator. Among the unsolicited AEs considered to be related to study vaccine, chills were the most frequently reported (2.9% after receiving both vaccines concomitantly [CoAd group]; 2.2% after receiving Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccine alone [Control group]; 1.0% after receiving Fluzone-HD vaccine alone [Control group]; and 0.3% after receiving placebo alone [CoAd group]). Unsolicited AEs of grade ≥3 were mostly reported in those receiving both vaccines concomitantly (2.1%) and those receiving Fluzone-HD alone (2.8%), and were less common in those receiving Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein (0.6%) and placebo alone (0.6%). Hypertension (systolic or diastolic) was the most frequent unsolicited AE of grade ≥3, reported in 1.0% of those receiving both vaccines concomitantly (CoAd group), 0.3% of those receiving Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccine alone (Control group), 1.6% of those receiving Fluzone-HD vaccine alone (Control group), and 0.6% of those receiving placebo alone (CoAd group); none of these events were deemed related to study vaccine by the investigators. Two participants had grade 4 unsolicited AEs: 1 had myocardial infarction 11 days after coadministration of Fluzone-HD and Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccines, and 1 had angina pectoris 27 days after receiving Fluzone-HD. Both events were considered by the investigator to be serious and not related to study vaccine.

One (0.3%) participant died due to cardiac arrest 119 days after concomitant Fluzone-HD and Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccine administration. This event was considered not related to study vaccine by the investigator. SAEs were reported in 13 (3.4%) participants in the CoAd group and 11 (2.8%) in the Control group. One SAE in the Control group, grade 3 rhabdomyolysis, was considered related to study vaccine by the investigator. This event was diagnosed together with grade 2 urinary tract infection (UTI) 6 days after Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccine administration and resolved after 3 days of hospitalization. An independent data monitoring committee reviewed this case and recommended that the participant continue the study without modification. Other SAEs were considered not related to study vaccine by the investigator. AEs that led to the second study vaccination not being administered were reported in 6 (1.6%) participants in the CoAd group (5 hypertension and 1 atrial fibrillation) and 4 (1.0%) participants in the Control group (1 hypertension, 1 congestive heart failure, and 2 coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19]). None were considered related to study vaccine by the investigator. There were no AEs leading to study discontinuation. No potential AESIs were considered related to study vaccine by investigators, nor did they meet the clinical characteristics of VITT/TTS due to the onset, thrombosis location, accompanying comorbidities, or absence of thrombocytopenia as assessed by the TTS adjudication committee.

DISCUSSION

RSV vaccines are likely to be coadministered with an influenza vaccine as both would be indicated for older adults and the seasonality of RSV and influenza typically overlap [6]. Such coadministration could improve public health outcomes by promoting convenience, reducing barriers to vaccination, and increasing vaccine uptake in a vulnerable older adult population. Here, we assessed the safety and immunogenicity of Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein and Fluzone-HD vaccines when administered concomitantly or separately. Noninferiority analysis showed that the coadministered and individually administered vaccines induced comparable immune responses, results that were confirmed with sensitivity analyses. Seroconversion and seroprotection rates were also similar when the vaccines were concomitantly administered. Altogether, these results showed that, upon coadministration, the immunogenicity of Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein and Fluzone-HD vaccines was not compromised, suggesting that efficacy would not be impacted.

Solicited local and systemic AE data indicated that Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein was more reactogenic than Fluzone-HD. Upon coadministration, the frequency of solicited local AEs remained comparable to single-vaccine administration, while solicited systemic AEs were more frequent with coadministration. This trend was driven by grade 1 and 2 AEs, as grade 3 systemic AEs were equal between those receiving both vaccines concomitantly and Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccine alone. Thus, these findings suggest that both vaccines remain well tolerated upon coadministration. One SAE, rhabdomyolysis, was considered treatment-related as it was diagnosed 6 days post–Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccination. The rhabdomyolysis was accompanied by a UTI. Previous studies have shown that COVID-19 and influenza vaccinations, as well as bacterial and viral infections, could trigger rhabdomyolysis [23–26]. Thus, in this participant, both UTI and Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccination could not be discounted as a plausible cause. Rhabdomyolysis has not been observed in other Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccine recipients in other trials [15, 18]. No other SAEs or AEs leading to study discontinuation were considered related to study vaccine. VITT/TTS was considered as an AESI in this study since it has been very rarely observed among those receiving Janssen's Ad26.COV2.S COVID-19 vaccine (JCOVDEN®), which shares its platform technology with Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein [27]. None of the study participants developed VITT/TTS postvaccination. To date, no cases of VITT have been identified in clinical trials of Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein or in other Ad26-based vaccines besides JCOVDEN®. Collectively, these data demonstrated that Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein and Fluzone-HD vaccines were generally well tolerated and did not show any safety concern when administered concomitantly.

This study complements previous findings showing the efficacy of Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein in preventing RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection in older adults and its capacity to induce robust humoral and cellular immune responses [15, 18]. A previous coadministration study of the Ad26.RSV.preF vaccine (without RSV preF protein) and standard-dose seasonal influenza vaccine (Fluarix®) showed no safety concerns and no evidence of interference in vaccine-induced immune responses [27]. It is important to acknowledge that correlates of protection for RSV are less defined than those for influenza, where HI titers ≥40 have been shown to be protective [28]. The lack of established correlates of protection makes clinical interpretation of any immunogenicity studies on RSV vaccines challenging. This includes whether the noninferiority margins that are commonly used in coadministration studies properly represent clinical significance [19, 29]. Despite this limitation, we showed that coadministration of Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein and Fluzone-HD was generally well tolerated and had a limited effect on vaccine-induced immune responses. While a trend was observed in which immune responses to the Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein vaccine were slightly impacted when coadministered with the Fluzone-HD vaccine, differences were not statistically significant and did not exceed the noninferiority margin. Altogether, these results support the coadministration of Ad26.RSV.preF/RSV preF protein and Fluzone-HD vaccines.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Widagdo Widagdo, Janssen Vaccines and Prevention B.V., Leiden, The Netherlands.

Arangassery Rosemary Bastian, Janssen Vaccines and Prevention B.V., Leiden, The Netherlands.

Archana M Jastorff, Janssen Research and Development.

Ilse Scheys, Janssen Research and Development.

Els De Paepe, Janssen Infectious Diseases, Beerse, Belgium.

Christy A Comeaux, Janssen Vaccines and Prevention B.V., Leiden, The Netherlands.

Nynke Ligtenberg, Janssen Vaccines and Prevention B.V., Leiden, The Netherlands.

Benoit Callendret, Janssen Vaccines and Prevention B.V., Leiden, The Netherlands.

Esther Heijnen, Janssen Vaccines and Prevention B.V., Leiden, The Netherlands.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Karin Weber for her contributions to the manuscript. Editorial support was provided by Laura Watts, PhD, of Lumanity Communications Inc., and was funded by Janssen Vaccines and Prevention B.V.

Author contributions. W. W. contributed to study design, data acquisition, data interpretation, and manuscript writing and review. A. R. B. contributed to study design, assay selection, data interpretation, and manuscript review. A. M. J. contributed to conception and design of the study and data collection and acquistion. I. S. contributed to data analysis and interpretation and drafting of the manuscript. E. D. P. contributed to study design, data analysis and interpretation, and drafting the manuscript. C. A. C. contributed to study design and protocol development, data interpretation, and drafting the manuscript. N. L. contributed to data acquisition, data interpretation, and manuscript review. B. C. and E. H. contributed to study design, data interpretation, and manuscript review. All authors were involved in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data. The authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and analyses and for the fidelity of the study to the protocol.

Data availability. The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency. As noted on this site, requests for access to the study data can be submitted through the Yale Open Data Access (YODA) project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.

Disclaimer. This study was sponsored and designed by Janssen Vaccines and Prevention B.V. The sponsor was responsible for study management and the data analysis.

Financial support. This work was supported by Janssen Vaccines and Prevention B.V. during all stages of the trial and its analysis and during the development and publishing of the manuscript, including scientific writing assistance and statistical analyses. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Janssen Vaccines and Prevention B.V.

References

- 1. Savic M, Penders Y, Shi T, Branche A, Pirçon JY. Respiratory syncytial virus disease burden in adults aged 60 years and older in high-income countries: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2023; 17:e13031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, O’Leary M, Martin ET, et al. Burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in older and high-risk adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence from developed countries. Eur Respir Rev 2022; 31:220105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shi T, Denouel A, Tietjen AK, et al. Global disease burden estimates of respiratory syncytial virus–associated acute respiratory infection in older adults in 2015: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Dis 2020; 222:S577–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. GBD 2017 Influenza Collaborators . Mortality, morbidity, and hospitalisations due to influenza lower respiratory tract infections, 2017: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir Med 2019; 7:69–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lafond KE, Porter RM, Whaley MJ, et al. Global burden of influenza-associated lower respiratory tract infections and hospitalizations among adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2021; 18:e1003550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li Y, Reeves RM, Wang X, et al. Global patterns in monthly activity of influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, and metapneumovirus: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2019; 7:e1031–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee JKH, Lam GKL, Shin T, Samson SI, Greenberg DP, Chit A. Efficacy and effectiveness of high-dose influenza vaccine in older adults by circulating strain and antigenic match: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 2021; 39:A24–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. DiazGranados CA, Dunning AJ, Kimmel M, et al. Efficacy of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:635–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sanofi . Fluzone high-dose quadrivalent. 2023. https://www.sanofiflu.com/fluzone-high-dose-influenza-vaccine/. Accessed 16 May 2023. 2023.

- 10. World Health Organization . Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2021–2022 Northern Hemisphere influenza season. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/recommended-composition-of-influenza-virus-vaccines-for-use-in-the-2021-2022-northern-hemisphere-influenza-season. Accessed 7 November 2023.

- 11. European Medicines Agency . Amended BWP Ad hoc Influenza Working Group: EU recommendations for the seasonal influenza vaccine composition for the season 2021/2022. 2021. https://www.ema.europa.eu/system/files/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/2022-amended_en.pdf. Accessed 16 January 2024.

- 12. Rowe T, Abernathy RA, Hu-Primmer J, et al. Detection of antibody to avian influenza A (H5N1) virus in human serum by using a combination of serologic assays. J Clin Microbiol 1999; 37:937–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organization . Manual for the laboratory diagnosis and virological surveillance of influenza. 2011. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/manual-for-the-laboratory-diagnosis-and-virological-surveillance-of-influenza. Accessed 7 November 2023.

- 14. National Institute for Biological Standards and Control . Influenza reagent: influenza antigen A/Tasmania/503/2020 (IVR-221) (H3N2) NIBSC code: 21/116 instructions for use. 2021. https://www.nibsc.org/documents/ifu/21-116.pdf. Accessed 8 November 2023.

- 15. Falsey AR, Williams K, Gymnopoulou E, et al. Efficacy and safety of an Ad26.RSV.preF-RSV preF protein vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med 2023; 388:609–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. US Food and Drug Administration . Guidance for industry. Toxicity grading scale for healthy adult and adolescent volunteers enrolled in preventative vaccine clinical trials. 2007. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/toxicity-grading-scale-healthy-adult-and-adolescent-volunteers-enrolled-preventive-vaccine-clinical. Accessed 16 May 2023.

- 17. Chang LJ, Meng Y, Janosczyk H, Landolfi V, Talbot HK; QHD00013 Study Group . Safety and immunogenicity of high-dose quadrivalent influenza vaccine in adults ≥65 years of age: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. Vaccine 2019; 37:5825–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Williams K, Bastian AR, Feldman RA, et al. Phase 1 safety and immunogenicity study of a respiratory syncytial virus vaccine with an adenovirus 26 vector encoding prefusion F (Ad26.RSV.preF) in adults aged ≥60 years. J Infect Dis 2020; 222:979–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. US Food and Drug Administration . Guidance for industry. Clinical data needed to support the licensure of seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine. 2007. https://www.fda.gov/files/vaccines%2C%20blood%20%26%20biologics/published/Guidance-for-Industry--Clinical-Data-Needed-to-Support-the-Licensure-of-Seasonal-Inactivated-Influenza-Vaccines.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2023.

- 20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . RSV in older adults and adults with chronic medical conditions. 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/high-risk/older-adults.html. Accessed 8 December 2021.

- 21. Brighton Collaboration . Interim case definition of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome. 2021. https://brightoncollaboration.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/TTS-Updated-Brighton-Collaboration-Case-Defintion-Draft-Nov-11-2021.pdf. Accessed 17 January 2024.

- 22. Oliver SE, Wallace M, See I, et al. Use of the Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) COVID-19 vaccine: updated interim recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, December 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022; 71:90–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cao PD, Menard JR. Rhabdomyolysis secondary to urinary tract infection with E coli. Patient care. 2013. https://www.patientcareonline.com/view/rhabdomyolysis-secondary-urinary-tract-infection-e-coli. Accessed 16 May 2023.

- 24. Singh U, Scheld WM. Infectious etiologies of rhabdomyolysis: three case reports and review. Clin Infect Dis 1996; 22:642–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liozon E, Filloux M, Parreau S, et al. Immune-mediated diseases following COVID-19 vaccination: report of a teaching hospital-based case-series. J Clin Med 2022; 11:7484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Callado RB, Carneiro TG, Parahyba CC, Lima Nde A, da Silva Junior GB, de Francesco Daher E. Rhabdomyolysis secondary to influenza A H1N1 vaccine resulting in acute kidney injury. Travel Med Infect Dis 2013; 11:130–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sadoff J, De Paepe E, Haazen W, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the Ad26.RSV.preF investigational vaccine coadministered with an influenza vaccine in older adults. J Infect Dis 2021; 223:699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cox RJ. Correlates of protection to influenza virus, where do we go from here? Hum Vaccin Immunother 2013; 9:405–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. US Food and Drug Administration . AREXVY (respiratory syncytial virus vaccine, adjuvanted)—summary basis for regulatory action. 2023. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/arexvy. Accessed 2 November 2023.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.