Abstract

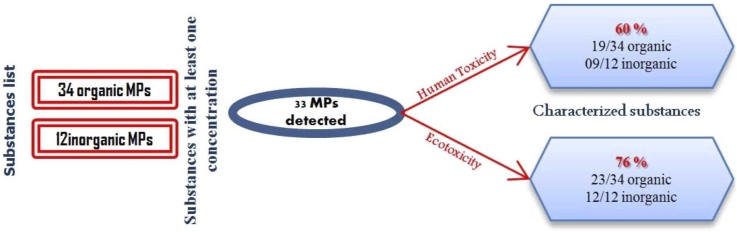

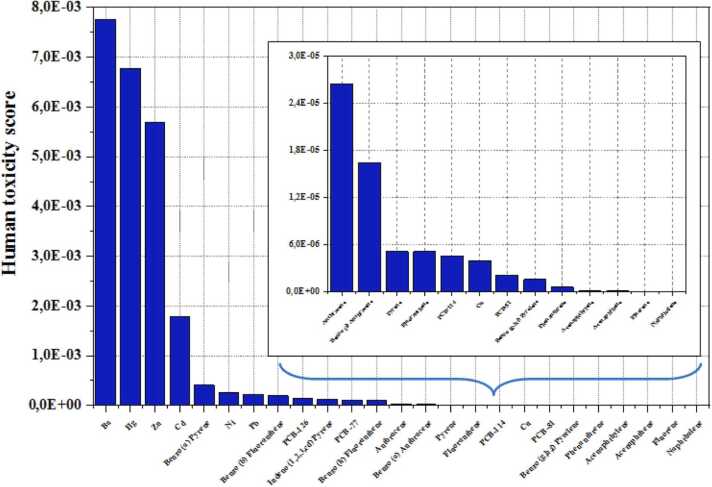

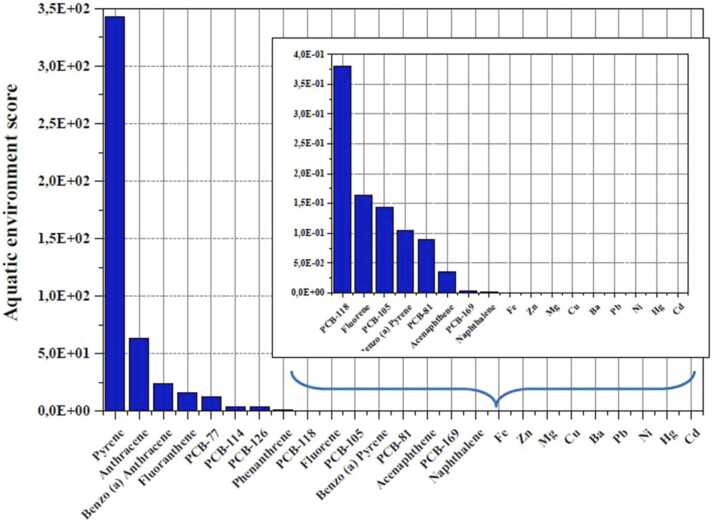

Wastewater contains a variety of compounds qualified as pollutants. These undergo incomplete treatment in wastewater treatment plants. The objective of this study is to determine the potential impacts on humans and aquatic environment of 46 organic and inorganic micropollutants using the USE-tox® model. The concentrations used in this study are obtained by analyzing raw and treated wastewater from the wastewater treatment plant of the city of Al-Hoceima, Morocco. The total human health impact score is 10−2, generally varying between 10−3 and 10−9. Ba, Hg, Zn and Cd had the highest score with a percentage of 92 % of the total score. For the aquatic environment, impact was estimated for 25 compounds. Pyrene, Anthracene, Benzo(a)Anthracene, Fluoranthene and PCB-77 were the major contributors with an impact ranging from 3.43E+02–1.21E+01 PDF.m3.d. With a value of 3.43E+02, Pyrene had the highest impact, contributing 73 % by itself.

Keywords: Aquatic environment, Human health, Impact assessment, Wastewater treatment plant

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Impacts of 46 micropollutants on humans and aquatic environments using the USE-tox® model.

-

•

Analyzed wastewater from Al-Hoceima, Morocco.

-

•

Ba, Hg, Zn, Cd: 92% of total score (10-2).

-

•

Pyrene, Anthracene, Benzo(a)Anthracene, Fluoranthene, PCB-77: major contributors, Pyrene at 73%.

1. Introduction

The release of micropollutants (MPs) from wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) into the environment is a primary issue related to micropollutants in sanitation. These discharges have been for a long considered a pivotal contributor to the introduction into the environment [1], [2], [3], [4]. It has been proven by previous works that micropollutants are present in treated wastewaters, and also contamination of fresh and sea waters [1], [5], [6].

The removal efficiency of micropollutants in WWTP is satisfactory, even if they are not well adapted to remove these compounds [7], [8], [9], [10]. This elimination is essentially done by adsorption on sludge (hydrophobic substances), by biological degradation, or by an abiotic degradation for some substances [11], [12]. However, some substances are only partially or not at all absorbed or degraded. They can be described as "refractory" to biological treatment. As a result, some micropollutants are still present in discharges from conventional wastewater treatment plants at significant concentrations [13], [14].

The diffusion of micropollutants (MPs) into the environment is facilitated by wastewater treatment plants. It is therefore important to evaluate the effects of these compounds. Inorganic micropollutants such as heavy metals (Lead, Mercury, Cadmium, etc.) and arsenic can seriously damage human health by contaminating drinking water and aquatic ecosystems, leading to neurological, cardiovascular and kidney problems, as well as posing risks to aquatic life [15], [16], [17], [18]. Organic micropollutants, including pharmaceuticals, pesticides, industrial compounds (PCBs, PAHs, PFCs) and microplastics, can disrupt aquatic ecosystems and harm human health when consumed in contaminated water or food, contributing to antibiotic resistance, endocrine disruption, cancer risks and environmental damage [19]. Monitoring and treatment of these micropollutants is mandatory to protect humans and aquatic environments from their harmful effects. The ratios Predicted Environmental Concentration with The Predicted No Effect Concentration PEC/PNEC and Measured Environmental Concentration with the Predicted No Effect Concentration MEC/PNEC are generally used to assess the risk of these substances [20]. PNEC takes in consideration the sensitive organisms. MEC shows the concentration in environment. And PEC present the concentration emitted taking in consideration the dilution. The micropollutant is considered harmful when the quotient PEC/PNEC is above one (PEC/PNEC > 1) [21], [22], [23]. In this approaches, molecules are studied one by one. The fact that we cannot estimate the overall risk limits this approach [1], [24], [25], [26].

Another way to assess the effect of micropollutants on humans and the aquatic environment is the life cycle analysis (LCA) of a molecule or group of molecules as it was highlighted in several works [27], [28], [29]. The LCA model focuses primarily on assessing the environmental impacts of substances throughout their life cycle, which includes their production, use and disposal. While LCA can provide valuable insights into the wider environmental consequences of substances, it is not specifically designed to analyze their effects on the human body or the aquatic environment in terms of health or toxicity. To assess the effects on human health or the aquatic environment, more specialized models or methods are generally used, such as risk assessment or toxicological studies. However, LCA is better suited to assessing the overall sustainability and environmental footprint of products, processes or services. Muñoz et al. discovered that 15 out of 98 micropollutants had a high risk on Humans and aquatic environment. While, based on USEtox® characterization factors [30] assessed the ecotoxicological impact of micropollutants in Spain.

Our study focused on assessing the impact of 46 organic and inorganic micropollutants belonging to 3 major families (Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs), Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and Heavy Metals) quantified from the outlet and inlet of the Al-Hoceima city WWTP on Humans and Aquatic environment using LCA model.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Targeted micropollutants

Samples were analyzed in 2022. 33 targeted molecules were found in wastewater. While 13 were quantified occasionally. These compounds, includes 03 heavy metals, 08 PCBs, and 02 PAHs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Micropollutants considered and its distribution.

| Micropollutants | Raw wastewater | Treated wastewater | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAHs | Acenaphthene | + | + |

| Acenaphthylene | + | + | |

| Anthracene | + | + | |

| Benzo (a) anthracene | + | + | |

| Benzo (a) pyrene | + | + | |

| Benzo (b) Fluoranthene | + | + | |

| Benzo (g,h,i) pyrelene | + | + | |

| Benzo (k) Fluoranthene | + | + | |

| Chrysene | - | - | |

| Dibenzo (a,h) Anthracene | - | - | |

| Fluoranthene | + | + | |

| Fluorene | + | + | |

| Indeno (1,2,3,cd) Pyrene | + | + | |

| Naphthalene | + | + | |

| Phenanthrene | + | + | |

| Pyrene | + | + | |

| PCBs | PCB−28 | - | - |

| PCB−52 | - | - | |

| PCB−77 | + | + | |

| PCB−81 | + | + | |

| PCB−101 | - | - | |

| PCB−105 | + | + | |

| PCB−114 | + | + | |

| PCB−118 | + | + | |

| PCB−123 | - | - | |

| PCB−126 | + | + | |

| PCB−138 | - | - | |

| PCB−153 | - | - | |

| PCB−156 | + | + | |

| PCB−157 | - | - | |

| PCB−167 | + | + | |

| PCB−169 | + | + | |

| PCB−180 | - | - | |

| PCB−189 | + | + | |

| HMs | Cu | + | + |

| Zn | + | + | |

| Fe | + | + | |

| Mn | + | + | |

| Cd | + | + | |

| Pb | + | + | |

| As | - | - | |

| Ni | + | + | |

| Ba | + | + | |

| Cr | - | - | |

| Co | - | - | |

| Hg | + | + | |

2.2. Sampling and analysis

The wastewater treatment plant of Al-Hoceima city operates on an activated sludge at low load [31]. It treats a daily flow of 9600 m3 of wastewater from anthropogenic activities [31], [32]. The system is composed of different treatment steps. Classically, the treatment is divided into: pre-treatment, secondary or biological treatment, tertiary treatment and sludge treatment [33], [34]. Overall, three sets of samples were successfully collected. Composite samples were taken continuously at each site, using refrigerated automatic samplers maintained at 4°C. To prevent any risk of contamination of the samples and adsorption of pollutants during the collection process, these samplers were equipped with glass bottles and Teflon® pipes. In addition and in order to preserve the original distribution of pollutants between dissolved phases and suspended particles, samples were filtered as soon as possible through a 0.45 μm filter to remove fine particles. After filtration, the dissolved fraction was analysed within 24 hours of collection, while the particulate fraction was analysed within 48 hours [31], [34], [35], [36], [37]. The levels of PAHs and PCBs in the samples that were gathered were assessed using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), while the concentrations of heavy metals (HMs) were determined through Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) [32].

2.3. Potential impact assessment of wastewater

This work aims, to evaluate the impact of wastewater discharged into sea, as the case in our study, on the aquatic environment and human health using a methodology. USEtox 2.12® was used to calculate the characterization factors (CF) for micropollutants with this equation: CF = XF x EF x FF.

with XF: ecotoxicity exposure factor / EF: the effect factor / FF: the fate factor.

USEtox is a scientifically sound consensus model that has been officially endorsed by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) Life Cycle Initiative. Its main objective is to provide a systematic and comprehensive approach to characterizing the potential human and ecotoxicological impacts of various chemicals used in different industrial processes and products. The cornerstone of the USEtox framework is its vast database, rich in characterization factors. These factors encompass a wide range of essential parameters, including those relating to the fate, exposure and effects of chemicals. By integrating and analyzing this wealth of data, USEtox enables a more accurate and comprehensive assessment of the potential environmental and health risks associated with chemical substances, making it a valuable tool for informed decision-making, sustainable product development and risk management in a variety of sectors.

Characterization factors for humans added the ingestion fraction (IF), which is the value token of MPs from water, air, and food (IF = XF x FF). In this study, we project to assess the impact of each substance as well as the impact of the entire mixture of MPs. Then the potential impacts were calculated using this equation: Impact potential = ∑ Characterization factor x Emitted Mass. The emitted mass was obtained by multiplying the concentrations with the annual volume.

Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) was used to determine the impact on human health. Potentially Disappeared Fraction integrated (PDF.m3.d) was used to express the impact on the aquatic environment. In order to obtain the total score, we summed all the impacts.

2.4. Quantity of wastewater released in a year

To estimate the quantity of wastewater released into the aquatic environment, we considered that the volume entering and leaving the WWTP is stable. The WWTP receives a flow of 9600 m3 daily. After multiplying it by 365 days, we got an estimated annual volume of 3504,000 m3.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Micropollutants concentrations

46 micropollutants (organic and inorganic) were studied, including 12 HMs, 18 PCBs and 16 PAHs. 71.74 % of organic and inorganic micropollutants searched were detected in raw and treated wastewaters (33/46). 13/46 of the rest were quantified occasionally in the three campaigns.

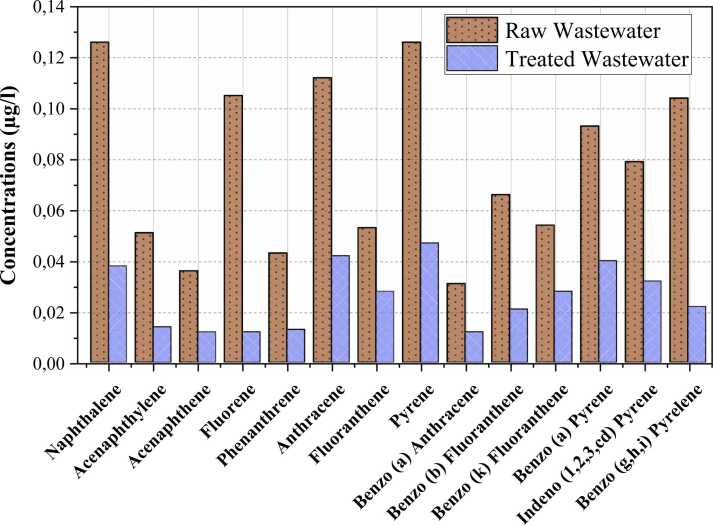

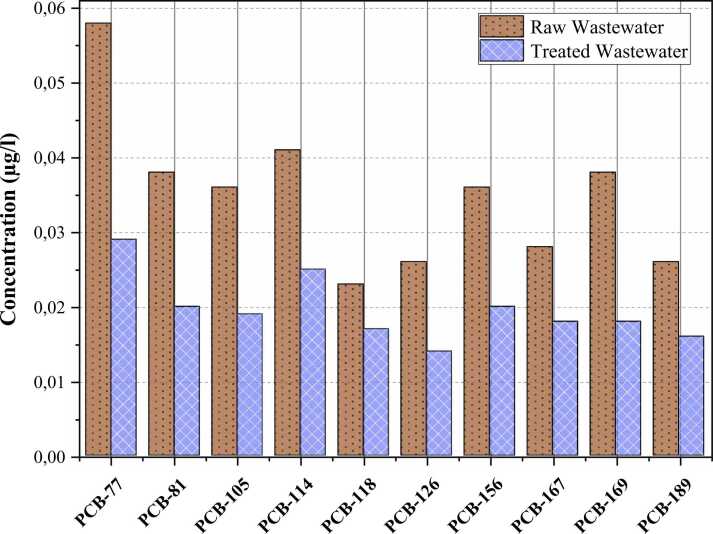

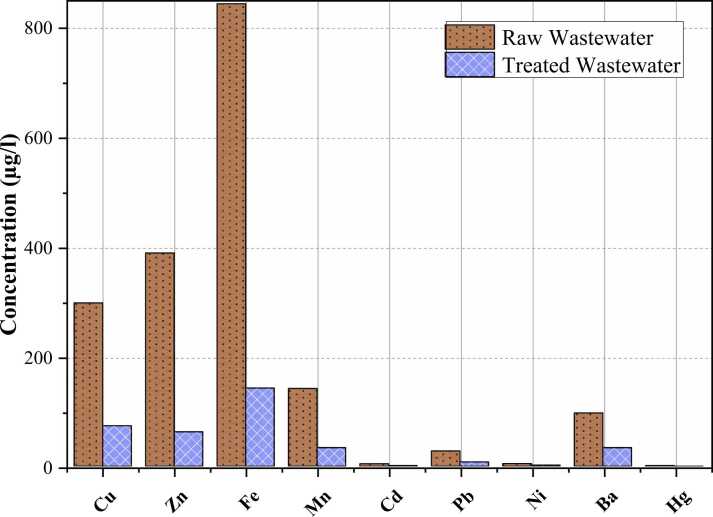

Concentrations in raw wastewater were 0.02–850 μg/L. The highest concentrations, logically, belong to heavy metals with 1.2–845 μg/L. Then, it comes PAHs with high molecular weight (0.09–1 μg/L). At the end, there are the PCBs and rest of PAHs with concentrations ranging between 0.01 and 0.09 μg/L.

The same compounds belonging to same families were detected in the outlet of the WWTP. Concentrations quantified were presented in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3. They ranged between 0.012 and 143 μg/L. Removals efficiencies were the highest for some inorganic micropollutants (more than 80 %), while they ranged between 50 % and 80 % for the rest of the compounds.

Fig. 1.

Concentrations of PAHs in the inlet and outlet of the WWTP.

Fig. 2.

Concentrations of PCBs in the inlet and outlet of the WWTP.

Fig. 3.

Concentrations of HMs in the inlet and outlet of the WWTP.

3.2. Assessing impact of MPs on Human health

The characterization factors along the Emitted masses from the WWTP obtained are presented in Table 2. A high concentration reflects high emitted masses into environment. The potential impact on Human health was assessed for 60 % of micropollutants (28/46), because of the lack of the concentrations or/and characterization factors. Characterization factor was equal to 0 for Chrysene, PCB-28, PCB-55, PCB-101, PCB-105, PCB-118, PCB-123, PCB-138, PCB-153, PCB-156, PCB-157, PCB-167, PCB-169, PCB-180, PCB-189, Fe, Mg and Co.

Table 2.

Human health characterization factor [DALY/kg emitted].

| Substance Name | Estimated annual volume (m3) | Emitted Mass in kg |

Human health characterization factor [DALY/kg emitted] |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cancer | non-canc | total | |||

| Naphthalene | 3504000 | 0.133152 | 3.8815E−08 | 2.4292E−09 | 4.1244E−08 |

| Acenaphthylene | 3504000 | 0.049056 | 2.6216E−06 | n/a | 2.6216E−06 |

| Acenaphthene | 3504000 | 0.042048 | 2.7205E−06 | 2.2595E−08 | 2.7431E−06 |

| Fluorene | 3504000 | 0.042048 | 2.4544E−06 | 2.8539E−08 | 2.483E−06 |

| Phenanthrene | 3504000 | 0.045552 | 1.3969E−05 | n/a | 1.3969E−05 |

| Anthracene | 3504000 | 0.147168 | 0.00018 | 2.6163E−08 | 0.00018003 |

| Fluoranthene | 3504000 | 0.098112 | 5.1867E−05 | 6.0309E−07 | 5.247E−05 |

| Pyrene | 3504000 | 0.164688 | 3.071E−05 | 5.9514E−07 | 3.1305E−05 |

| Benzo (a) Anthracene | 3504000 | 0.042048 | 0.00039097 | n/a | 0.00039097 |

| Chrysene | 3504000 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Benzo (b) Fluoranthene | 3504000 | 0.073584 | 0.00265367 | n/a | 0.00265367 |

| Benzo (k) Fluoranthene | 3504000 | 0.098112 | 0.00110217 | n/a | 0.00110217 |

| Benzo (a) Pyrene | 3504000 | 0.14016 | 0.00291188 | n/a | 0.00291188 |

| Indeno (1.2.3.cd) Pyrene | 3504000 | 0.112128 | 0.00109856 | n/a | 0.00109856 |

| Dibenzo (a.h) Anthracene | 3504000 | n/a | 0.02549973 | n/a | 0.02549973 |

| Benzo (g.h.i) Pyrelene | 3504000 | 0.077088 | 2.0546E−05 | n/a | 2.0546E−05 |

| PCB−28 | 3504000 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| PCB−52 | 3504000 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| PCB−77 | 3504000 | 0.101616 | n/a | 0.00109856 | 0.00109856 |

| PCB−81 | 3504000 | 0.0681 | n/a | 3.1305E−05 | 3.1305E−05 |

| PCB−101 | 3504000 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| PCB−105 | 3504000 | 0.066576 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| PCB−114 | 3504000 | 0.0876 | 5.247E−05 | n/a | 5.247E−05 |

| PCB−118 | 3504000 | 0.059568 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| PCB−123 | 3504000 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| PCB−126 | 3504000 | 0.049056 | n/a | 0.00291188 | 0.00291188 |

| PCB−138 | 3504000 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| PCB−153 | 3504000 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| PCB−156 | 3504000 | 0.07008 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| PCB−157 | 3504000 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| PCB−167 | 3504000 | 0.063072 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| PCB−169 | 3504000 | 0.063072 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| PCB−180 | 3504000 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| PCB−189 | 3504000 | 0.056064 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Cu | 3504000 | 259.296 | n/a | 1.531E−08 | 1.531E−08 |

| Zn | 3504000 | 220.752 | n/a | 2.5792E−05 | 2.5792E−05 |

| Fe | 3504000 | 501.072 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Mg | 3504000 | 119.136 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Cd | 3504000 | 4.5552 | 6.1146E−06 | 0.00038516 | 0.00039128 |

| Pb | 3504000 | 28.032 | 9.6434E−08 | 7.9424E−06 | 8.0389E−06 |

| As | 3504000 | n/a | 0.00013398 | 0.00233006 | 0.00246404 |

| Ni | 3504000 | 7.008 | 3.6625E−05 | 4.8389E−07 | 3.7109E−05 |

| Ba | 3504000 | 119.136 | n/a | 6.5156E−05 | 6.5156E−05 |

| Cr | 3504000 | n/a | n/a | 4.0766E−12 | 4.0766E−12 |

| Co | 3504000 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Hg | 3504000 | 0.7008 | 0.00033553 | 0.00932517 | 0.00966071 |

n/a: Not applicable

Observable effects (e.g., in vivo and in vitro bioassays) have demonstrated that chemicals pose a risk to human health. PCBs, PAHs, and HMs represent one such case.

In this investigation, results obtained for impact assessment ranged between 10 and 3 and 10–9. The total impact score was 10–2 (Fig. 4). The highest impact score belonged to inorganic micropollutants (Ba, Hg, Zn and Cd). These elements represented 92 % of the total impact on Human health score. When deciding on priorities, it is important to consider the toxicity of the elements, not just the mass released. The results of this study prove that the emission of MPs into seawater may affect the Human health directly or indirectly [38]. 3/10 main contributors were PAHs produced by human activities. The compounds with the highest score are considered to be carcinogenic [38].

Fig. 4.

Human toxicity impact score.

Micropollutants, whether organic or inorganic in origin, have significant effects on human health. Heavy metals, such as lead and mercury, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) can cause respiratory problems, such as lung irritation and infections. Some organic micropollutants, such as pesticides and pharmaceuticals, can cause liver and kidney toxicity, affecting metabolic health. In addition, endocrine disruptors among organic micropollutants can disrupt the hormonal system, leading to reproductive problems, developmental abnormalities and diseases such as cancer. Some micropollutants, notably polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and organochlorine compounds, are classified as carcinogenic to humans, increasing the risk of cancer [39], [40], [41], [42]. Heavy metals, such as lead and mercury, can also have harmful effects on the nervous system, leading to neurological and cognitive disorders. Finally, ingesting micropollutants through contaminated water or marine products can cause gastrointestinal problems. It is crucial to reduce exposure to micropollutants and implement preventive measures to minimise the risks to human health associated with these substances.

Aemig et al. assessed the impact on Human health of 286 organic and inorganic micropollutants emitted by WWTPs in France. The impact was estimated for 109/286 mentioning the lack of data on toxicity or concentrations. As, Zn, some PAHs and pesticides had the highest score. While, Muñoz et al. [23] studied the impact of 98 micropollutants. They considered a situation in which treated wastewater was used for agricultural irrigation (discharged into the soil). The characterization factor was calculated using two methods (EDIP97 and USES-LCA). Four substances (two for each method), respectively, had the highest impact: gemfibrozil, nicotine, 2,3,7,8-TCDD and hexachlorobenzene. In our study, these micropollutants were not considered [43].

3.3. Assessing impact of MPs on aquatic environment

Ecotoxicity characterization factors (Ecotox. Charact. Factors) were found for over 76 % of micropollutants in this study (Table 3). For the total organic and inorganic micropollutants, the impact was estimated for 35 compounds. Five key contributors among PAHs and PCBs include Pyrene, Anthracene, Benzo(a)Anthracene, Fluoranthene and PCB-77 with and impact going from 3.43E+02–1.21E+01 PDF.m3.d (Fig. 5). With a value of 3.43E+02, Pyrene had the highest impact contributing by 73 % alone. While Anthracene, Benzo(a)Anthracene, Fluoranthene, and PCB-77 had a respective percentage of 13,5,3 and 2 %. Inorganic micropollutants had the lowest impact ranging from 1.45E-11–6.34E-19 PDF.m3.d. Even if the inorganic micropollutants are present in Aquatic environment, but it is difficult to identify their impact since the Characterization factors afforded by USEtox 2.12® should be interpreted carefully.

Table 3.

Aquatic Environment Characterization factor [PDF.m3.day.kg−1].

| Substance Name | Mean concentration in the outlet (µg/L) | Estimated annual volume (m3) | Emitted Mass in kg | Ecotox. Charact. factor [PDF.m3.day.kg-1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naphthalene | 0.038 | 3504000 | 0.133152 | 0.00813289 |

| Acenaphthylene | 0.014 | 3504000 | 0.049056 | n/a |

| Acenaphthene | 0.012 | 3504000 | 0.042048 | 0.83122894 |

| Fluorene | 0.012 | 3504000 | 0.042048 | 3.87967028 |

| Phenanthrene | 0.013 | 3504000 | 0.045552 | 20.5255943 |

| Anthracene | 0.042 | 3504000 | 0.147168 | 430.785283 |

| Fluoranthene | 0.028 | 3504000 | 0.098112 | 158.923509 |

| Pyrene | 0.047 | 3504000 | 0.164688 | 2084.48231 |

| Benzo (a) Anthracene | 0.012 | 3504000 | 0.042048 | 573.991056 |

| Chrysene | n/a | 3504000 | n/a | n/a |

| Benzo (b) Fluoranthene | 0.021 | 3504000 | 0.073584 | n/a |

| Benzo (k) Fluoranthene | 0.028 | 3504000 | 0.098112 | n/a |

| Benzo (a) Pyrene | 0.04 | 3504000 | 0.14016 | 0.74132405 |

| Indeno (1.2.3.cd) Pyrene | 0.032 | 3504000 | 0.112128 | n/a |

| Dibenzo (a.h) Anthracene | n/a | 3504000 | n/a | 0.14803029 |

| Benzo (g.h.i) Pyrelene | 0.022 | 3504000 | 0.077088 | n/a |

| PCB−28 | n/a | 3504000 | n/a | 1.31444044 |

| PCB−52 | n/a | 3504000 | n/a | 4.01323712 |

| PCB−77 | 0.029 | 3504000 | 0.101616 | 119.2009 |

| PCB−81 | 0.020 | 3504000 | 0.0681 | 1.31444044 |

| PCB−101 | n/a | 3504000 | n/a | 893.593531 |

| PCB−105 | 0.019 | 3504000 | 0.066576 | 2.16128625 |

| PCB−114 | 0.025 | 3504000 | 0.0876 | 43.5183401 |

| PCB−118 | 0.017 | 3504000 | 0.059568 | 6.39610779 |

| PCB−123 | n/a | 3504000 | n/a | 25.6873149 |

| PCB−126 | 0.014 | 3504000 | 0.049056 | 76.1204561 |

| PCB−138 | n/a | 3504000 | n/a | 414.231911 |

| PCB−153 | n/a | 3504000 | n/a | 49.7798592 |

| PCB−156 | 0.020 | 3504000 | 0.07008 | n/a |

| PCB−157 | n/a | 3504000 | n/a | n/a |

| PCB−167 | 0.018 | 3504000 | 0.063072 | n/a |

| PCB−169 | 0.018 | 3504000 | 0.063072 | 0.0552413 |

| PCB−180 | n/a | 3504000 | n/a | n/a |

| PCB−189 | 0.016 | 3504000 | 0.056064 | n/a |

| Cu | 74 | 3504000 | 259.296 | 1.8088E−16 |

| Zn | 63 | 3504000 | 220.752 | 6.8798E−15 |

| Fe | 143 | 3504000 | 501.072 | 2.8965E−14 |

| Mg | 34 | 3504000 | 119.136 | 2.5771E−15 |

| Cd | 1.3 | 3504000 | 4.5552 | 1.3928E−19 |

| Pb | 8 | 3504000 | 28.032 | 2.7356E−17 |

| As | n/a | 3504000 | n/a | 6.0432E−16 |

| Ni | 2 | 3504000 | 7.008 | 8.3624E−17 |

| Ba | 34 | 3504000 | 119.136 | 2.3696E−16 |

| Cr | n/a | 3504000 | n/a | 3.5004E−19 |

| Co | n/a | 3504000 | n/a | 3.6444E−15 |

| Hg | 0.2 | 3504000 | 0.7008 | 1.0164E−18 |

Fig. 5.

Ecotoxicity impact score.

Impact on Aquatic environment of 45 and 88 PPCPs was assessed respectively by [30], [43]. Total impact of the same order of importance was observed. At low concentrations, micropollutants can have a considerable impact on the aquatic environment, in contrast to the risk to human health. Mainly, the difference of impact is due to emitted masses. To identify impacts of micropollutants, [23] used Life Cycle Assessment. Two models were used USES-LCA and EDIP97. The substances with highest impact, respectively, are fluoxetine and ibuprofen. In other study, they paired in vitro impacts of MPs and biotests. The results showed high impact for some substances agreeing with our study [44].

Researchers worked on the impact of changing wastewater treatment process on biodiversity [45]. After adding a tertiary treatment (activated carbon filtration), they noticed no impact on the aquatic environment. This is due to the improvement of oxygen concentrations. However, the substances present in the effluent were negligible.

Other works, such as [25] and [26], confirmed occurrence of organic MPs in aquatic organisms, demonstrating bioaccumulative effect of these substances in aquatic food chains. In each fish, a number of eleven micropollutants were detected, which increases the risk to other fish and especially to humans [46], [47].

Micropollutants, whether organic or inorganic, have substantial effects on the aquatic environment. They can have a series of worrying consequences, including accumulation in ecosystems, disruption of food chains and reduced biodiversity. Organic micropollutants, such as pesticides and pharmaceuticals, can contaminate rivers and oceans, directly affecting the aquatic organism’s life. This contamination can disrupt reproductive cycles, cause genetic mutations and have harmful impacts on aquatic flora and fauna. In addition, inorganic micropollutants, such as heavy metals, can accumulate in river sediments, affecting the quality of aquatic habitats. The effects spread through food chains, affecting fish and other marine species, and ultimately humans consuming seafood. Reduced biodiversity, altered aquatic ecosystems and reduced water quality are major concerns linked to the presence of micropollutants in aquatic environments.

4. Conclusions

This research has been conducted on the impact of the MPs on human health and the aquatic environment. The total score for the impact on human health is 10–2, generally varying between 10 and 3 and 10–9. The inorganic micropollutants (Ba, Hg, Zn and Cd) had the highest score with a percentage of 92 % of the total score. The total impact of micropollutants on the aquatic environment was estimated for 25 compounds. Five key contributors: Pyrene, Anthracene, Benzo(a)Anthracene, Fluoranthene and PCB-77 with an impact ranging from 3.43E+02–1.21E+01 PDF.m3.d. with a value of 3.43E+02, Pyrene had the highest impact, contributing 73 % by itself.

The lack of data on the impact of micropollutants on human health and the aquatic environment is notable. The calculation of the impact score was calculated by a limited number of molecules due to the lack of concentrations or characterization factors.

The discharge of organic matter into aquatic ecosystems can result in eutrophication, oxygen depletion, and habitat disruption, negatively impacting aquatic biodiversity. Additionally, heavy metals, although initially present in water in small quantities, can bioaccumulate and biomagnify in the food chain, leading to human exposure and potential health risks when consuming contaminated fish and seafood. Effective management strategies are crucial to mitigate these impacts and safeguard both aquatic biodiversity and human health.

This study raised the issue of the presence of micropollutants in the environment, and the need to prohibit or reduce at source. Finishing treatments have proven to be effective against micropollutants, but they do not manage to eliminate them completely.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chaimae Haboubi: Visualization, Validation. Hatim Faiz: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Aouatif El Abdouni: Methodology, Investigation. Fouad Dimane: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision. Kawthar El Ahmadi: Methodology, Resources. Imane Dira: Data curation, Investigation. Yahya El hammoudani: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization. Abdelaziz TOUZANI: Methodology, Software. Khadija Haboubi: Writing – original draft, Software, Investigation. Mohamed MOUDOU: Software, Visualization. Abdelhak Bourjila: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology. Mustapha EL BOUDAMMOUSSI: Investigation, Methodology. Iliass Achoukhi: Visualization, Validation, Software. Maryam ESSKIFATI: Investigation, Methodology. Chaimae Benaissa: Software, Methodology, Formal analysis.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Handling Editor: Prof. L.H. Lash

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Luo Y., Guo W., Ngo H.H., Nghiem L.D., Hai F.I., Zhang J., Liang S., Wang X.C. A review on the occurrence of micropollutants in the aquatic environment and their fate and removal during wastewater treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;473:619–641. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abouabdallah A., El Hammoudani Y., Dimane F., Haboubi K., Rhayour K., Benaissa C. Impact of waste on the quality of water resources – case study of Taza City, Morocco. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2023;24:170–182. doi: 10.12912/27197050/173375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouhout S., Haboubi K., El Abdouni A., El Hammoudani Y., Haboubi C., Dimane F., Hanafi I., Elyoubi M.S. Appraisal of groundwater quality status in the ghiss-nekor coastal plain. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023;24 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Touzani A., El Hammoudani Y., Dimane F., Tahiri M., Haboubi K. Characterization of leachate and assessment of the leachate pollution index–a study of the controlled landfill in fez. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2024;25:57–69. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Margot J., Rossi L., Barry D.A., Holliger C. A review of the fate of micropollutants in wastewater treatment plants. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. 2015;2:457–487. doi: 10.1002/wat2.1090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeroundi D., Elmsellem H., Chakroune S., Idouhli R., Elyoussfi A., Dafali A., Hadrami E., Ben-Tama A., Kandri R. Physicochemical study and corrosion inhibition potential of dithiolo [4, 5-b][1,4] dithiepine for mild steel in acidic medium. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2016;7:4024–4035. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elabdouni A., Haboubi K., Merimi I., El Youbi M. Olive mill wastewater (OMW) production in the province of Al-Hoceima (Morocco) and their physico-chemical characterization by mill types. Mater. Today Proc. 2020;27:3145–3150. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Achoukhi I., El Hammoudani Y., Dimane F., Haboubi K., Bourjila A., Haboubi C., Benaissa C., Elabdouni A., Faiz H. Investigating microplastics in the mediterranean coastal areas–case study of Al-Hoceima Bay, Morocco. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023;24:12–31. [Google Scholar]

- 9.El Hammoudani Y., Dimane F., Haboubi K., Benaissa C., Benaabidate L., Bourjila A., Achoukhi I., El Boudammoussi M., Faiz H., Touzani A. Micropollutants in wastewater treatment plants: a bibliometric-bibliographic study. Desalin. Water Treat. 2024 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haboubi K., El Abdouni A., El Hammoudani Y., Dimane F., Haboubi C. Estimating biogas production in the controlled landfill of fez (morocco) using the land-gem model. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2023;22:1813–1820. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin Ruel S., Choubert J.-M., Budzinski H., Miège C., Esperanza M., Coquery M. Occurrence and fate of relevant substances in wastewater treatment plants regarding Water Framework Directive and future legislations. Water Sci. Technol. 2012;65:1179–1189. doi: 10.2166/wst.2012.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hassouni H.E., Elyousfi A., Benhiba F., Setti N., Romane A., Benhadda T., Zarrouk A., Dafali A. Corrosion inhibition, surface adsorption and computational studies of new sustainable and green inhibitor for mild steel in acidic medium. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022;143 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coquery M., Pomies M., Ruel S.M., Budzinski H., Miège C., Esperanza M., Soulier C., Choubert J. Mesurer les micropolluants dans les eaux usées brutes et traitées. Protoc. Et. Résultats pour l′Anal. Des. Conc. Et. Des. flux. Tech. Sci. Methodes. 2011;1:25–43. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elabdouni A., Haboubi K., Bensitel N., Bouhout S., Aberkani K., El Youbi M S. Removal of organic matter and polyphenols in the olive oil mill wastewater by coagulation-flocculation using aluminum sulfate and lime. Moroc. J. Chem. 2022;10:191–202. https://doi.org/10.48317/IMIST.PRSM/morjchem-v10i1.28852. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmad J., Naeem S., Ahmad M., Usman A.R., Al-Wabel M.I. A critical review on organic micropollutants contamination in wastewater and removal through carbon nanotubes. J. Environ. Manag. 2019;246:214–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.05.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Gethami W., Qamar M.A., Shariq M., Alaghaz A.-N.M., Farhan A., Areshi A.A., Alnasir M.H. Emerging environmentally friendly bio-based nanocomposites for the efficient removal of dyes and micropollutants from wastewater by adsorption: a comprehensive review. RSC Adv. 2024;14:2804–2834. doi: 10.1039/d3ra06501d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benstoem F., Becker G., Firk J., Kaless M., Wuest D., Pinnekamp J., Kruse A. Elimination of micropollutants by activated carbon produced from fibers taken from wastewater screenings using hydrothermal carbonization. J. Environ. Manag. 2018;211:278–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bourgin M., Beck B., Boehler M., Borowska E., Fleiner J., Salhi E., Teichler R., von Gunten U., Siegrist H., McArdell C.S. Evaluation of a full-scale wastewater treatment plant upgraded with ozonation and biological post-treatments: abatement of micropollutants, formation of transformation products and oxidation by-products. Water Res. 2018;129:486–498. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.du Plessis M., Fourie C., Stone W., Engelbrecht A.-M.J.B. The impact of endocrine disrupting compounds and carcinogens in wastewater: implications for breast cancer. 2023;209:103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2023.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouaissa M., Gharibi E., Ghalit M., Taupin J.D., Boukich O., El Khattabi J. Groundwater quality evaluation using the pollution index and potential non-carcinogenic risk related to nitrate contamination in the karst aquifers of Bokoya massif, northern Morocco. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2022:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunnarsson L., Snape J.R., Verbruggen B., Owen S.F., Kristiansson E., Margiotta-Casaluci L., Österlund T., Hutchinson K., Leverett D., Marks B. Pharmacology beyond the patient–the environmental risks of human drugs. Environ. Int. 2019;129:320–332. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y., Ok Y.S., Kim K.-H., Kwon E.E., Tsang Y.F. Occurrences and removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in drinking water and water/sewage treatment plants: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;596:303–320. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muñoz I., Gómez M.J., Molina-Díaz A., Huijbregts M.A., Fernández-Alba A.R., García-Calvo E. Ranking potential impacts of priority and emerging pollutants in urban wastewater through life cycle impact assessment. Chemosphere. 2008;74:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan N.A., Singh S., López-Maldonado E.A., Méndez-Herrera Pavithra N., López-López P.F., Baig J.R., Ramamurthy U., Mubarak P.C., Karri N.M. R R. Emerging membrane technology and hybrid treatment systems for the removal of micropollutants from wastewater. Desalination. 2023;565 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim M., Patureau D., Heran M., Lesage G., Kim J. Removal of organic micropollutants in anaerobic membrane bioreactors in wastewater treatment: critical review. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2020;6:1230–1243. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sher F., Hanif K., Rafey A., Khalid U., Zafar A., Ameen M., Lima E.C. Removal of micropollutants from municipal wastewater using different types of activated carbons. J. Environ. Manag. 2021;278 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunhoferova H., Venditti S., Hansen J., Gallagher J.J. Life cycle performance and associated environmental risks of constructed wetlands used for micropollutant removal from municipal wastewater effluent. C. E S. 2024;12 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dogan K., Turkmen B.A., Arslan-Alaton I., Germirli Babuna F.J.W. Life cycle assessment as a decision-making tool for photochemical treatment of iprodione fungicide from wastewater. 2024;16:1183. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melián E.P., Santiago D.E., León E., Reboso J.V., Herrera-Melián J.A.J.J. o E C E. Treatment of laundry wastewater by different processes: optimization and life cycle assessment. 2023;11 [Google Scholar]

- 30.de García S.O., García-Encina P.A., Irusta-Mata R. The potential ecotoxicological impact of pharmaceutical and personal care products on humans and freshwater, based on USEtox™ characterization factors. A Spanish case study of toxicity impact scores. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;609:429–445. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benaissa C., Bouhmadi B., Rossi A., El Hammoudani Y. Hydro-chemical and bacteriological study of some sources of groundwater in the GHIS-NEKOR and the BOKOYA Aquifers (AL HOCEIMA, MOROCCO) Proc. 4th Ed. Int. Conf. Geo IT Water Resour. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benaissa C., Bouhmadi B., Rossi A., El Hammoudani Y., Dimane F. Assessment of water quality using water quality index – case study of bakoya aquifer, Al Hoceima, Northern Morocco. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2022;23:31–44. doi: 10.12912/27197050/149495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dimane F., Haboubi K., Hanafi I., El Himri A. Performance study of the activated sludge wastewater treatment system of Al-Hoceima City, Morocco. Eur. Sci. J. 2016;12:272. doi: 10.19044/esj.2016.v12n17p272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El Hammoudani Y., Dimane F., El Ouarghi H. Springer; 2019. Fate of Selected Heavy Metals in a Biological Wastewater Treatment System. in Euro-Mediterranean Conference for Environmental Integration. [Google Scholar]

- 35.El Hammoudani Y., Dimane F. Assessing behavior and fate of micropollutants during wastewater treatment: statistical analysis. Environ. Eng. Res. 2020 doi: 10.4491/eer.2020.359. 0:0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El Hammoudani Y., Dimane F., El Ouarghi H. Removal efficiency of heavy metals by a biological wastewater treatment plant and their potential risks to human health. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2021;20:995–1002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dimane F., El Hammoudani Y. Assessment of quality and potential reuse of wastewater treated with conventional activated sludge. Mater. Today. Proc. 2021;45:7742–7746. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.03.428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oldenkamp R., Hoeks S., Čengić M., Barbarossa V., Burns E.E., Boxall A.B., Ragas A.M. A high-resolution spatial model to predict exposure to pharmaceuticals in European surface waters: EPiE. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52:12494–12503. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b03862. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b03862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee S., Kim M., Ahn B.J., and Jang Y.J.J. o h m. Odorant-responsive biological receptors and electronic noses for volatile organic compounds with aldehyde for human health and diseases: a perspective review. 2023;455:131555. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Dehghani M.H., Bashardoust P., Zirrahi F., Ajami B., Ghalhari M.R., Noruzzade E., Sheikhi S., Mubarak N.M., Karri R.R., and Ravindran G.J.H.E. o I.A.P.. Environmental and health effects due to volatile organic compounds. 2024;191-221.

- 41.J-j Lv, X-y Li, Y-c Shen, J-x You, M-z Wen, J-b Wang, X-t J F i P H Yang. Assess. volatile Org. Compd. Expo. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. US adults. 2023;11:1210136. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krismanuel H., Hairunisa N.J.P.J.I.K. Eff. Air Pollut. Respir. Probl. A Lit. Rev. 2024;18:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aemig Q., Hélias A., Patureau D. Impact assessment of a large panel of organic and inorganic micropollutants released by wastewater treatment plants at the scale of France. Water Res. 2021;188 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neale P.A., Ait-Aissa S., Brack W., Creusot N., Denison M.S., Deutschmann B. r, Hilscherová K., Hollert H., Krauss M., Novak J. Linking in vitro effects and detected organic micropollutants in surface water using mixture-toxicity modeling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49:14614–14624. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b04083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson A.C., Jürgens M.D., Edwards F.K., Scarlett P.M., Vincent H.M., von der Ohe P. What works? The influence of changing wastewater treatment type, including tertiary granular activated charcoal, on downstream macroinvertebrate biodiversity over time. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2019;38:1820–1832. doi: 10.1002/etc.4460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richmond E.K., Rosi E.J., Walters D.M., Fick J., Hamilton S.K., Brodin T., Sundelin A., Grace M.R. A diverse suite of pharmaceuticals contaminates stream and riparian food webs. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06822-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ojemaye C.Y., Petrik L. Occurrences, levels and risk assessment studies of emerging pollutants (pharmaceuticals, perfluoroalkyl and endocrine disrupting compounds) in fish samples from Kalk Bay harbour, South Africa. Environ. Pollut. 2019;252:562–572. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.