Abstract

The evolutionary expansion of sensory neuron populations detecting important environmental cues is widespread, but functionally enigmatic. We investigated this phenomenon through comparison of homologous olfactory pathways of Drosophila melanogaster and its close relative Drosophila sechellia, an extreme specialist for Morinda citrifolia noni fruit. D. sechellia has evolved species-specific expansions in select, noni-detecting olfactory sensory neuron (OSN) populations, through multigenic changes. Activation and inhibition of defined proportions of neurons demonstrate that OSN number increases contribute to stronger, more persistent, noni-odour tracking behaviour. These expansions result in increased synaptic connections of sensory neurons with their projection neuron (PN) partners, which are conserved in number between species. Surprisingly, having more OSNs does not lead to greater odour-evoked PN sensitivity or reliability. Rather, pathways with increased sensory pooling exhibit reduced PN adaptation, likely through weakened lateral inhibition. Our work reveals an unexpected functional impact of sensory neuron population expansions to explain ecologically-relevant, species-specific behaviour.

Subject terms: Olfactory system, Speciation, Sensory processing

Sensory neuron population expansions are common in evolution but of unclear function. Here, the authors show that, in drosophilid olfactory systems, increased sensory neuron number impacts interneuron dynamics, but not sensitivity, to promote olfactory-guided behaviour.

Introduction

Brains display incredible diversity in neuron number between animal species1–3. Increases in the number of neurons during evolution occur not only through the emergence of new cell types but also through expansion of pre-existing neuronal populations4,5. Of the latter phenomenon, some of the most spectacular examples are found in sensory systems: the snout of the star-nosed mole (Condylura cristata) has ~25,000 mechanosensory organs, several fold more than other mole species6. Male (but not female) moths can have tens of thousands of neurons detecting female pheromones, representing the large majority of sensory neurons in their antennae7. A higher number of sensory neurons is generally assumed to underlie sensitisation to the perceived cues8–11. Surprisingly, however, it remains largely untested if and how such neuronal expansions impact sensory processing and behaviour.

The drosophilid olfactory system is an excellent model to address these questions12,13. The antenna, the main olfactory organ, houses ~1000 olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) that, in Drosophila melanogaster, have been classified into ~50 types based on their expression of one (or occasionally more) Odorant receptors (Ors) or Ionotropic receptors (Irs)13–15. The size of individual OSN populations (ranging from ~10–65 neurons) is stereotyped across individuals, reflecting their genetically hard-wired developmental programmes16,17. By contrast, comparisons of homologous OSN types in ecologically-distinct drosophilid species have identified several examples of expansions in OSN populations. Notably, Drosophila sechellia, an endemic of the Seychelles that specialises on Morinda citrifolia “noni” fruit18–20, has an approximately three-fold increase in the neuron populations expressing Or22a, Or85b and Ir75b compared to both D. melanogaster and a closer relative, Drosophila simulans21–24 (Fig. 1a). All three of these neuron classes are required for long- and/or short-range odour-guided behaviours22,25 and two of these (Or22a and Ir75b) also display increased sensitivity to noni odours through mutations in the corresponding D. sechellia receptor genes21–23. Together, these observations have led to a long-held assumption that these OSN population expansions are important for D. sechellia, but this has never been tested.

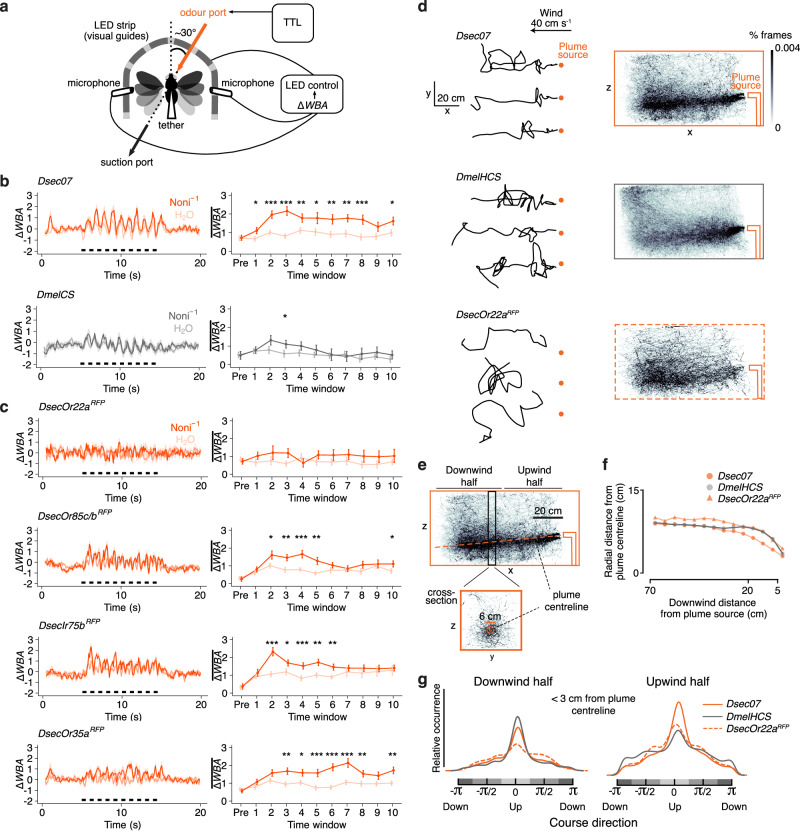

Fig. 1. Selective expansion of noni-sensing olfactory sensory neuron populations is a complex developmental trait.

a Drosophilid phylogeny. Ma, million years ago. b Left top, drosophilid third antennal segment. Left bottom, antennal basiconic 3 (ab3) sensilla house neurons expressing Or22a (and Or22b in D. melanogaster and D. simulans; this paralog is lost in D. sechellia) (hereafter, “Or22a neuron”) and Or85c/b (hereafter, “Or85b neuron”). Right, antennal Or22a/(b) and Or85b expression in D. sechellia (Drosophila Species Stock Centre (DSSC) 14021-0248.07 (Dsec07)) and D. simulans (DSSC 14021-0251.004 (Dsim04)). Scale bar, 25 µm. In addition to ab3 sensilla (within the dashed line), Or85b is expressed in ~ 10 OSNs in ab6 sensilla (Supplementary Fig. 1b). c Sensilla numbers in D. melanogaster (Canton-S, CS), D. simulans (Dsim04) and D. sechellia (Dsec07) determined by RNA FISH using a diagnostic Or probe (grey background) for each sensillum class (ai: antennal intermediate, at: antennal trichoid, ac: antennal coeloconic, sac3: sacculus chamber 3). Ir neuron data are from21; Ir75d neurons common to ac1, ac2 and ac4 sensilla are not shown. For these and all other box plots, the centre line represent the median, the box bounds represent the first and third quartiles, and whiskers depict at maximum 1.5 × the interquartile range; individual data points are overlaid. Wilcoxon signed-rank test (two-sided) with comparison to D. melanogaster: ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; NS, not significant (P > 0.05). Sample sizes are indicated in the figure. d Reciprocal hemizygosity test in D. simulans/D. sechellia hybrids of contributions of Or22a/(b) and Or85c/b to species-specific OSN numbers, using RNA FISH to quantify numbers of Or22a/(b) and Or85b OSNs in the indicated genotypes (“Dsec +” = Dsec07, “Dsim +” = Dsim04, “Dsec -” = DsecOr22aRFP or DsecOr85bGFP, “Dsim -” = DsimOr22a/bRFP or DsimOr85bGFP). See Supplementary Fig. 1f for representative images. Wilcoxon signed-rank test (two-sided) with comparison to wild-type hybrids: ***P < 0.001; NS, P > 0.05. e Quantification of GFP-expressing neurons in antennae of DsecOr85bGFP, DsimOr85bGFP and F1 hybrid males and females, and in F2 progeny of backcrosses of F1 hybrid females to either parental strain. The black line indicates the mean cell number. f Logarithm of odds (LOD) score across all four chromosomes for loci impacting Or85b neuron numbers based on the phenotypic data in e. Solid and dashed horizontal lines mark P = 0.01 and 0.05, respectively. g Effect sizes for the significant QTL intervals on chromosomes 3 and X in the D. simulans backcross. A, D. simulans allele; B, D. sechellia allele. Horizontal lines indicate the mean ± SEM for the cell number count of each allelic combination. A candidate gene, lozenge—encoding a transcription factor involved in sensillar specification87—located directly below the X chromosome peak, did not influence species-specific OSN numbers (Supplementary Fig. 2e–i).

Results

Selective large increases in Or22a and Or85b populations in D. sechellia

The increase in Or22a and Or85b OSN numbers in D. sechellia reflects the housing of these cells in a common sensory hair, the antennal basiconic 3 (ab3) sensillum (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). To determine how unique this increase is within the antenna, we compared the number of the other ~20 morphologically-diverse, olfactory sensillar classes—which each house distinct, stereotyped combinations of 1–4 OSN types—in D. sechellia, D. melanogaster and D. simulans through RNA FISH of a diagnostic Or per sensillum (combined with published data on Ir neurons21) (Fig. 1c). We observed several differences in sensillar number between these species, including reductions in ab5, ab8 and ai1 in D. sechellia, but only ab3, as well as ac3I that house Ir75b neurons, showed a more than two-fold increase (~50 more ab3, 2.6-fold increase; ~15 more ac3I, 3.7-fold increase) in D. sechellia. The total number of antennal sensilla is, however, similar across species (Fig. 1c).

OSN population expansion is a complex genetic trait

We next investigated the mechanism underlying the ab3 OSN population expansion in D. sechellia. The number of ab3 sensilla was not different when these flies were grown in the presence or absence of noni substrate (Supplementary Fig. 1c), arguing against an environmental influence. We first asked whether the ab3 increase could be explained by simple transformation of sensillar fate. Previous electrophysiological analyses reported loss of ab2 sensilla in D. sechellia, which was interpreted as a potential trade-off for the ab3 expansion23,26. However, we readily detected ab2 sensilla histologically in this species (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1d), countering this possibility. Moreover, from an antennal developmental fate map in D. melanogaster27, we did not observe any obvious spatial relationship between the sensory organ precursors for sensillar classes that display increases or decreases in D. sechellia to support a hypothesis of a simple fate switch, although both expanded populations (ab3 and ac3I) originate from peripheral regions of the map (Supplementary Fig. 1e).

We therefore reasoned that genetic changes specifically affecting the development of the ab3 lineage might be involved. We first tested for the existence of species-specific divergence in cis-regulation at the receptor loci. Using mutants for both Or22a/(b) and Or85b in D. simulans and D. sechellia22, we analysed receptor expression in interspecific hybrids and reciprocal hemizygotes (lacking transcripts from one or the other receptor allele) (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Fig. 1f). In all hybrid allelic combinations (except those lacking both alleles) we observed a similar number of Or22a and Or85b OSNs, arguing against a substantial contribution of cis-regulatory evolution at these loci to the expansion of receptor neuronal expression.

As little is known about the developmental programme of ab3 specification, we used an unbiased, whole-genome, quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping strategy to characterise the genetic basis of the expansion in D. sechellia. For high-throughput quantification of ab3 numbers, we generated fluorescent reporters of Or85b neurons in D. sechellia and D. simulans (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). Interspecific F1 hybrids displayed an intermediate number of Or85b neurons to the parental strains (Fig. 1e). We phenotyped >600 F2 individuals (backcrossed to either D. sechellia or D. simulans) (Fig. 1e), which were then genotyped using multiplexed shotgun sequencing28. The resulting QTL map (Fig. 1f) identified two genomic regions linked to variation in Or85b neuron number located on chromosomes 3 and X; these explain a cell number difference of about ~12 and ~7 neurons, respectively, between D. sechellia and D. simulans (Fig. 1g). No significant epistasis was detected between these genomic regions (Methods) and the relatively low effect size (21.0% and 12.3%, respectively) is consistent with a model in which more than two loci contribute to the species difference in Or85b neuron number. Consistent with the QTL map, introgression of fragments of the D. sechellia genomic region spanning the chromosome 3 peak into a D. simulans background led to an increased number of Or85b neurons (Supplementary Fig. 2c, d). However, the phenotypic effect was lost with smaller introgressed regions, indicating that multiple loci influencing Or85b neuron number are located within this QTL region (Supplementary Fig. 2d).

In a separate QTL mapping of the genetic basis for the increase in ac3I (Ir75b) neurons in D. sechellia21 (Fig. 1c), we also observed a complex genetic architecture of this interspecific difference, with no evidence for shared loci with the ab3 population expansion (Supplementary Fig. 2j, k). Thus, in contrast to the evolution of sensory specificity of olfactory pathways—where only one or a few amino acid substitutions in a single receptor can have a phenotypic impact21,22,25, with some evidence for “hotspot” sites in different receptors29—species differences in the number of OSNs have arisen from distinct evolutionary trajectories involving changes at multiple loci.

Expanded OSN populations are required for D. sechellia to track host odour

We next investigated if and how increased OSN population size impacts odour-tracking behaviour. Previously, we showed that both Or22a and Or85b pathways are essential for long-range attraction to noni in a wind tunnel22. To analyse the behavioural responses of individual animals to odours with greater resolution, we developed a tethered fly assay30 with a timed odour-delivery system (Fig. 2a). By measuring the beating amplitude of both wings while presenting a lateralised odour stimulus, we could quantify attractive responses to individual odours, as reflected in an animal’s attempt to turn toward the stimulus source, leading to a positive delta wing beat amplitude (ΔWBA) (see Methods). We first tested responses of wild-type flies to consecutive short pulses of noni odours, which mimic stimulus dynamics in a plume. As expected, multiple strains of D. sechellia exhibited attractive responses that persisted through most or all of the series of odour pulses, while D. melanogaster strains displayed much more variable degrees of attraction (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 3a). The persistent attraction in D. sechellia was specific to noni odour and could not be observed using apple cider vinegar (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

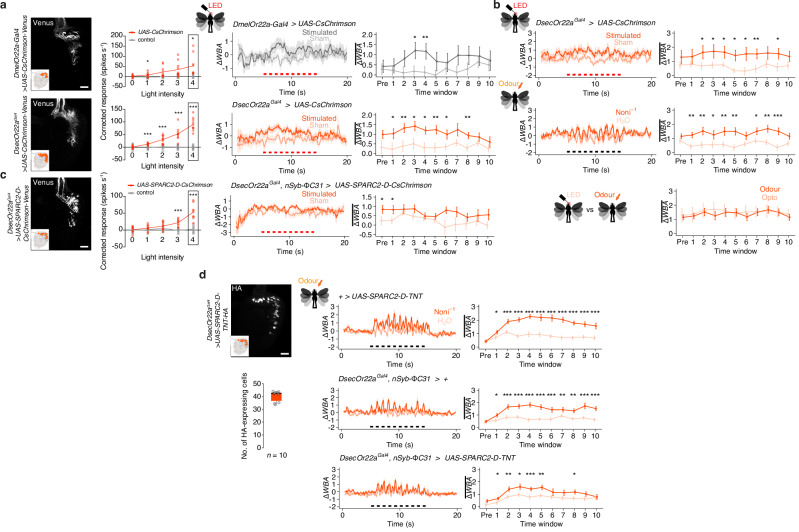

Fig. 2. Persistent behavioural tracking of noni odours in D. sechellia.

a Tethered fly behavioural assay. ΔWBA: left-right difference of standardised wing beat amplitudes, TTL: transistor–transistor logic. b, c Odour-tracking of noni juice and H2O in wild-type D. sechellia and D. melanogaster (b) and D. sechellia Or and Ir mutants (c). Left, time course of ΔWBA (mean ± SEM) where black bars indicate odour stimulation (ten 500 ms pulses with 500 ms intervals). Right, quantification in 1 s time windows immediately prior to stimulus onset (“pre”) and individual stimulus pulses (“1–10”). Mean ± SEM are shown. Paired t test (two-sided): ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05, otherwise P > 0.05. n = 30 animals each. d Left, example flight trajectories in the x-y plane of D. sechellia, D. melanogaster (a hybrid Heisenberg-Canton-S (HCS)) and D. sechellia Or22aRFP mutants in a noni plume. Right, occupancy heat maps of trajectories that came at least once within 10 cm of the plume centreline for Dsec07 (n = 835 trajectories, 7 recording replicates, 105 flies), DmelHCS (n = 1346 trajectories, 4 recording replicates, 60 flies), DsecOr22aRFP (n = 509 trajectories, 6 recording replicates, 90 flies). e Annotated view of the wild-type D. sechellia trajectories (from d) illustrating analyses in f, g. Based upon the trajectory distribution, we inferred that the noni juice plume sank by ~5 cm from the odour nozzle to the end of the tracking zone (Methods and Supplementary Fig. 4d–f). f Mean radial distance of the point cloud from the plume centreline for the trajectories in d. Data were binned into 5 cm y-z plane cross-sections starting 5 cm downwind from the plume origin, and restricted to 10 cm altitude above or below the estimated plume model. Non-parametric bootstrapped comparison (1000 iterations) of medians: P < 0.001. g Kernel density of the course direction distribution of points within a 3 cm radius of the plume centreline (orange circle on cross-section in e), further parsed into the point cloud in the downwind or upwind halves (e). Downwind half kernels: Dsec07 (15,414 points, 367 trajectories), DmelHCS (20,912 points, 511 trajectories), DsecOr22aRFP (3,244 points, 164 trajectories). Upwind half kernels: Dsec07 (136,827 points, 501 trajectories), DmelHCS (80,594 points, 615 trajectories), DsecOr22aRFP (40,560 points, 286 trajectories).

To assess the contribution of distinct olfactory pathways to noni attraction, we tested D. sechellia mutants for Or22a, Or85c/b, Ir75b and, as a control, Or35a, whose OSN population is also enlarged (as it is paired with Ir75b neurons in ac3I) but is dispensable for noni attraction22. Loss of Or22a abolished attraction of flies towards noni. Or85c/b and Ir75b mutants show less persistent attraction but retained some, albeit transient, turning towards this stimulus. Flies lacking Or35a behaved comparably to wild-type strains (Fig. 2c). These results point to Or22a as an important olfactory receptor required for D. sechellia to respond behaviourally to noni odour, with additional contributions of Or85c/b and Ir75b.

To better understand the nature of D. sechellia plume-tracking in a more natural setting, we used a wind-tunnel assay combined with 3D animal tracking31 to record trajectories of freely-flying wild-type D. melanogaster and D. sechellia, as they navigated to the source of a noni juice odour plume (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). Wild-type D. sechellia exhibited similar cast and surge dynamics as D. melanogaster32 (Fig. 2d). However, we observed that D. sechellia maintained flight paths closer to the plume centreline (Fig. 2d–f), a difference that was particularly evident close (<20 cm) to the plume source (Fig. 2d–f). Consistent with the phenotype observed in the tethered fly assay, D. sechellia Or22a mutants lacked strong plume-tracking responses (Fig. 2d–f), while not exhibiting obvious impairment in flight performance (Supplementary Fig. 4c). To extend analysis of these observations we quantified the distribution of flies within a 3 cm radius of the estimated odour plume centreline in the downwind and upwind halves of the wind tunnel (Fig. 2e, g). In the downwind half, wild-type D. sechellia and D. melanogaster had comparable course direction distributions (Fig. 2g). By contrast, in the upwind half, D. sechellia maintained a tighter upwind course distribution suggesting they were more likely to be in an upwind surging state compared to D. melanogaster as they approach the odorant source (Fig. 2g). D. sechellia Or22a mutants did not appear to be strongly oriented into the wind, notably in the downwind half, further indicating the importance of this olfactory pathway in stereotypical plume-tracking behaviours (Fig. 2g).

D. sechellia’s increase in OSN number is important for persistent odour-tracking behaviour

To investigate the importance of Or22a neuron number for odour-tracking behaviour we expressed CsChrimson in Or22a neurons in D. melanogaster and D. sechellia to enable specific stimulation of this pathway with red light. This optogenetic approach had two advantages: first, it allowed us to calibrate light intensity to ensure equivalent Or22a OSN activation between species; second, because only Or22a neurons are activated by light, we could eliminate sensory contributions from other olfactory pathways that have overlapping odour tuning profiles to Or22a.

We first confirmed light-evoked spiking in Or22a neurons in D. melanogaster and D. sechellia and determined the light intensity evoking equivalent spike rates (Fig. 3a). We then performed lateralised optogenetic activation33 of Or22a OSNs in the tethered fly assay, mimicking lateralised odour input by focussing the light beam on one antenna (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 5a). Pulsed optogenetic activation of D. sechellia Or22a OSNs induced attractive behaviour with a similar magnitude as pulsed odour stimuli—though not evoking the same time-locking of responses to individual pulses as for odours—demonstrating the sufficiency of this single olfactory pathway for evoking behaviour (Fig. 3a, b). Notably, the attractive behaviour was more persistent over the series of light pulses in D. sechellia than in D. melanogaster (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 5b–d), consistent with a hypothesis that a higher number of Or22a OSNs supports enduring behavioural attraction to a repeated stimulus.

Fig. 3. Behavioural significance of OSN number.

a Optogenetic stimulation of Or22a OSNs in D. melanogaster and D. sechellia. Left, CsChrimson-Venus expression in the antenna. Scale bar, 20 µm. Middle, single-sensillum recordings of Or22a neuron responses to optogenetic stimulation. Genotypes: D. melanogaster w;UAS-CsChrimson-Venus/+ (control), w;UAS-CsChrimson-Venus/Or22a-Gal4 (experimental), D. sechellia w;;UAS-CsChrimson-Venus/+ (control), w;Or22aGal4/+;UAS-CsChrimson-Venus/+ (experimental). The red line links the mean neuronal response at each light intensity, overlaid with individual data points. Black frames indicate the light intensity used for behavioural experiments. n = 5–10 sensilla (Supplementary Table 1). Right, behavioural responses of the same genotypes in response to optogenetic stimulation (ten 500 ms pulses with 500 ms intervals, indicated by the red bars). Time courses of ΔWBA (mean ± SEM) and quantification in each time window (mean ± SEM) are shown. n = 29 (D. melanogaster) and 30 (D. sechellia) animals. b Behavioural responses of D. sechellia upon optogenetic stimulation of Or22a OSNs and to noni odour stimulation (genotype as in a). Bottom, comparison of ΔWBA between light and odour responses, plotted as in a. n = 27 animals each. c Left, sparser Or22a neuron expression of CsChrimson in D. sechellia; dense packing of soma prevented quantification but is likely ~50% of total OSNs (Supplementary Fig. 6b, d). Scale bar, 20 µm. Middle, single-sensillum recordings of Or22a OSN responses to optogenetic stimulation. ab3 sensilla were first identified by stimulation with diagnostic odours (not shown); responses of CsChrimson-expressing neurons (experimental group) and non-expressing neurons (control, often from the same animal) are shown. n = 8-9 (Supplementary Table 1). Right, D. sechellia behaviour upon optogenetic activation of about half of their Or22a expressing neurons, plotted as in a. n = 26 animals. Genotypes: D. sechellia w;Or22aGal4/UAS-SPARC2-D-CsChrimson-Venus;;nSyb-ΦC31/+. d Left, HA immunofluorescence in a D. sechellia antenna expressing UAS-SPARC2-D-TNT-HA in Or22a neurons. Scale bar, 20 µm. Quantification (below) reveals ~50% of cells express the effector. Right, odour-tracking of noni juice of flies in effector control, driver control and experimental animals with blocked synaptic transmission, plotted as in a. n = 34 animals each. Genotypes: D. sechellia w;UAS-SPARC2-D-TNT-HA-GeCO/+;;+/+ (effector control), D. sechellia w;Or22aGal4/+;;nSyb-ΦC31/+ (driver control), D. sechellia w;Or22aGal4/UAS-SPARC2-D-TNT-HA-GeCO;;nSyb-ΦC31/+ (experimental group). For a–d unpaired Student’s t test (two-sided) (electrophysiology) or paired t test (two-sided) (behaviour): ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; otherwise P > 0.05.

To test this hypothesis, we generated genetic tools to reproducibly manipulate the number of active Or22a OSNs in D. sechellia, using the SPARC technology34 (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Combining a SPARC2-D-CsChrimson transgene with Or22a-Gal4 allowed us to optogenetically stimulate ~50% of Or22a neurons (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 6b). Although we confirmed light-evoked Or22a neuron spiking in these animals, they did not display attractive behaviour towards the light stimulus, in contrast to similar stimulation of all Or22a OSNs (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 6c). This result implies that the number of active OSNs is critical to induce attraction in D. sechellia.

Optogenetic activation of Or22a neurons only partially mimics differences between species because it does not offer the opportunity for any possible plasticity in circuit properties that are commensurate with differences in OSN number (as described below). We therefore took a complementary approach, through neuronal silencing, using a SPARC2-D-Tetanus Toxin (TNT) transgene. With this tool we could silence on average ~50% of Or22a OSNs (Fig. 3d)—likely from mid/late-pupal development (when the Or22a promoter is activated35)—without directly inhibiting other peripheral or central neurons (Supplementary Fig. 6d). Importantly, when tested in our tethered flight assay, these flies showed weaker and more transient attraction towards noni odour, contrasting with the persistent noni attraction of control animals (Fig. 3d). Together these results support the hypothesis that the increased Or22a OSN number observed in D. sechellia is essential for strong and sustained attractive olfactory behaviour.

OSN population expansions lead to increased pooling on cognate projection neurons

To better understand how increased OSN number might enhance odour-guided behaviour, we first characterised the anatomical properties of these pathways. The axons of OSNs expressing the same receptor converge onto a common glomerulus within the antennal lobe in the brain36 (Fig. 4a). Here, they form cholinergic synapses on mostly uniglomerular projection neurons (PNs)—which transmit sensory signals to higher olfactory centres—as well as on broadly-innervating local interneurons (LNs) and a small proportion on other OSNs36,37. To visualise PNs in D. sechellia, we generated specific driver transgenes in this species using constructs previously-characterised in D. melanogaster38,39: VT033006-Gal4, which drives expression in many PN types and VT033008-Gal4 which has sparser PN expression (Fig. 4b). Using these drivers to express photoactivable-GFP, we performed spatially-limited photoactivation of the DM2 and VM5d glomeruli—which receive input from Or22a and Or85b OSNs, respectively (Fig. 4a). We confirmed that DM2 is innervated by 2 PNs in both D. melanogaster and D. sechellia22 and further found that VM5d also has a conserved number of PNs (on average 4) in these species (Fig. 4c). Together with data that the Ir75b glomerulus, DL2d, has the same number of PNs in D. melanogaster, D. simulans and D. sechellia21,40, these observations indicate that D. sechellia’s OSN population expansions are not accompanied by increases in the number of PN partners.

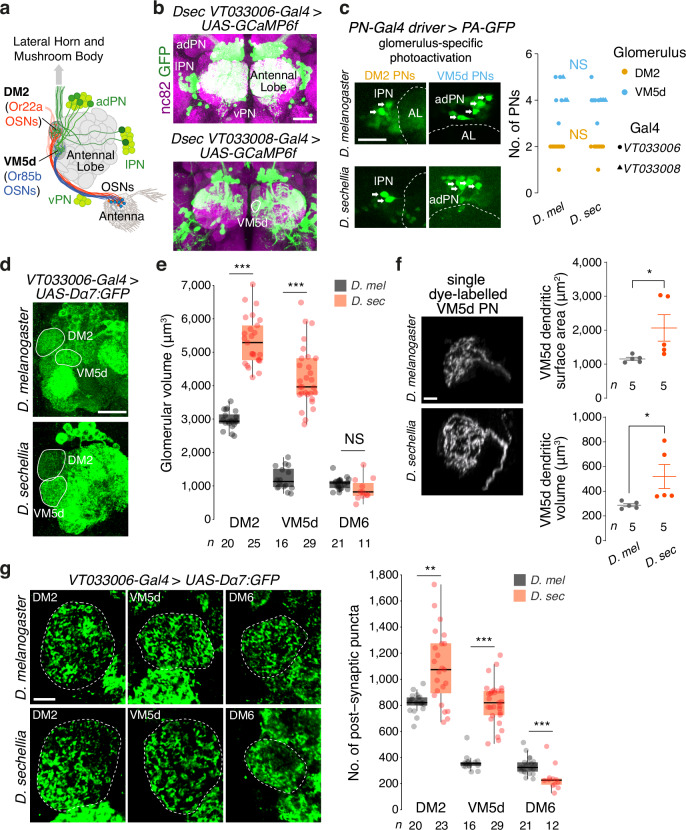

Fig. 4. Increased sensory and synaptic pooling in noni-sensing glomeruli.

a Antennal lobe circuitry. PN soma (green) are located in anterodorsal (ad), lateral (l) and ventral (v) clusters. LNs are not illustrated. b Labelling of PNs in D. sechellia using VT033006-Gal4 or VT033008-Gal4 to express UAS-GCaMP6f (used as a fluorescent reporter) through immunofluorescence for GFP (detecting GCaMP6f) and nc82 (detecting the synaptic protein Bruchpilot88). VM5d is outlined in the bottom image. Scale bar, 25 µm. c Left, representative images of VM5d and DM2 PNs labelled by photo-activatable GFP (PA-GFP) in D. melanogaster and D. sechellia. Genotypes: D. melanogaster w;UAS-C3PA-GFP/+;UAS-C3PA-GFP/VT033008-Gal4 (VM5d PNs) or w;UAS-C3PA-GFP/+;UAS-C3PA-GFP/VT033006-Gal4 (DM2 PNs); D. sechellia w,UAS-C3PA-GFP/w,VT033008-Gal4 (VM5d PNs) or w,UAS-C3PA-GFP/w,VT033006-Gal4 (DM2 PNs). Arrows indicate the PN cell bodies; faint background GFP signal is visible in other soma. Antennal lobe (AL) boundaries are demarcated by dashed lines. Scale bar, 25 µm. Right, quantification of PN numbers. Mann–Whitney U test (two-sided): NS, P > 0.05. d Visualisation of antennal lobe glomeruli by expression of the Dα7-GFP post-synaptic marker in PNs. Genotypes: D. melanogaster w;;VT033006-Gal4/UAS-Dα7-GFP, D. sechellia w,VT033006-Gal4/w;UAS-Dα7-GFP/+. Scale bar, 20 µm. e Quantification of the volumes of DM2, VM5d and a control glomerulus, DM6 (innervated by Or67a neurons) in D. sechellia and D. melanogaster. Wilcoxon signed-rank test (two-sided): ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.005. f Representative images of single dye-labelled VM5d PNs in D. melanogaster and D. sechellia. Mean ± SEM are shown. Genotypes: D. melanogaster w;VM5d-Gal4/UAS-GFP, D. sechellia w;VM5d-Gal4/UAS-myrGFP (GFP fluorescence is not shown). Scale bar, 5 µm. Right, quantification of VM5d PN dendritic surface area and volume. Student’s t test (two-sided): *P < 0.05. g Left, representative images of post-synaptic puncta in VM5d, DM2, and DM6 PNs labelled by Dα7-GFP in D. melanogaster and D. sechellia (genotypes as in d). Scale bar, 5 µm. Right, quantification of the number of post-synaptic puncta in these glomeruli. Wilcoxon signed-rank test (two-sided): ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.005.

Next, we expressed a post-synaptic marker, the GFP-tagged Dα7 acetylcholine receptor subunit, in PNs37,41,42 in D. melanogaster and D. sechellia (Fig. 4d). Quantification of glomerular volume as visualised with this reporter confirmed previous observations, using OSN markers21–24,40, that the DM2 and VM5d glomeruli, but not a control glomerulus (DM6), are specifically increased in D. sechellia compared to D. melanogaster (Fig. 4e). Given the constancy in PN number (Fig. 4c), this observation implied that PN dendrites must exhibit anatomical differences to occupy a larger volume. We examined this possibility through visualisation of single VM5d PNs by dye-labelling (in the course of electrophysiology experiments described below). Reconstruction of dendrite morphologies revealed that D. sechellia VM5d PNs have increased dendritic surface area and volume compared to the homologous neurons in D. melanogaster (Fig. 4f).

Finally, we quantified post-synaptic puncta of Dα7:GFP to estimate the number of excitatory OSN-PN connections in these glomeruli. Both DM2 and VM5d, but not DM6, displayed more puncta in D. sechellia than in D. melanogaster (Fig. 4g). Although quantifications of fluorescent puncta are likely to substantially underestimate the number of synapses (as detectable by electron microscopy)36,37, this reporter should still reflect the relative difference between species. Together these data suggest that an increase in OSN numbers leads to larger glomerular volumes, increased dendritic arborisation in partner PNs and more synaptic connections between OSNs and PNs.

OSN number increases do not lead to sensitisation of PN responses

To investigate the physiological significance of these OSN-PN circuit changes, we generated genetic reagents to visualise and thereby perform targeted electrophysiological recordings from specific PNs. We focused on VM5d PNs due to the availability of an enhancer-Gal4 transgene for sparse genetic labelling of this cell type43. Moreover, the partner Or85b OSNs’ sensitivities to the best-known agonist, 2-heptanone, are indistinguishable between species22. This enabled us to assess the specific impact of OSN population expansion on PN responses (in contrast to the Or22a pathway, which also exhibits receptor tuning differences). Through whole-cell patch clamp recordings from VM5d PNs in D. melanogaster and D. sechellia (Fig. 5a), we first observed that the input resistance of these cells was ~2-fold lower in D. sechellia (Fig. 5b), consistent with their larger dendritic surface area and volume (Fig. 4f). The resting membrane potential (Fig. 5c) and spontaneous activity (Fig. 5d) of these PNs were, however, unchanged between species. Surprisingly, VM5d PNs displayed no obvious increase in odour sensitivity in D. sechellia (Fig. 5e, Supplementary Fig. 7a); if anything, the peak spiking rate (within the first 50 ms after PN response onset) tended to be higher in D. melanogaster. However, we observed that the PN firing during the odour stimulus displayed a starker decay in D. melanogaster than in D. sechellia (Fig. 5f, Supplementary Fig. 7b). These data support a model in which increased synaptic input by more OSNs in D. sechellia is compensated by decreased PN input resistance precluding the sensitisation of responses in this cell type. Instead, OSN increases might impact the temporal dynamics of PN responses (explored further below).

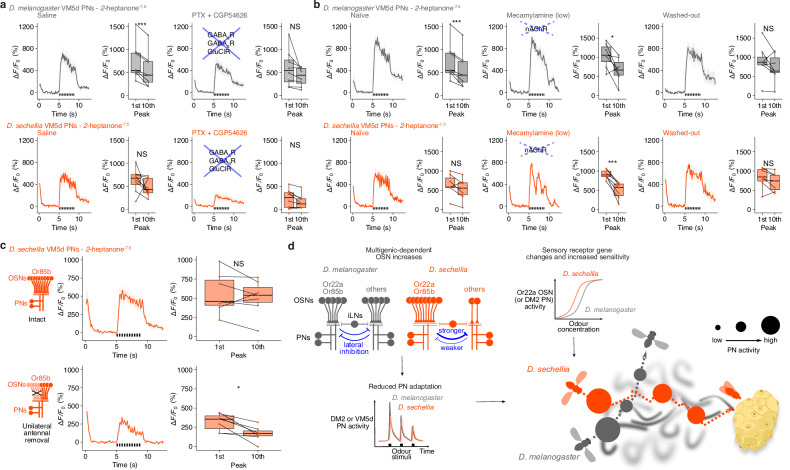

Fig. 5. Sustained representation of noni odour stimuli in PNs of D. sechellia.

a–d Whole-cell patch clamp recording from VM5d PNs in D. melanogaster and D. sechellia; glomerular circuitry is schematised on the left. Genotypes as in Fig. 4f. a Voltage trace of VM5d PNs in response to a pulse of 2-heptanone, and comparison of input resistance (b), resting membrane potential (c), and spontaneous activity (d) between species. b–d mean ± SEM are shown. n = 4 (D. melanogaster) and 5 (D. sechellia) animals. e Dose-response relationship of VM5d PN firing to 2-heptanone stimulation. Quantification of spike frequency was performed in a 50 ms window covering the peak response. Mean ± SEM are shown. n = 2–5 animals (Supplementary Table 1). EC50 values [Log] are as follows: −7.46 (Dmel), −6.87 (Dsec). f VM5d PN spike frequency in response to 10−6 dilution of 2-heptanone. Left, time course of spike frequency. Mean ± SEM are shown. Right, quantification of the decay magnitude (i.e., start (first 50 ms) - end (last 500 ms before odour offset)). n = 5 animals each. g, h Dose-dependent, odour-evoked calcium responses in Or85b/VM5d (g) and Or22a/DM2 (h) OSN axon termini and PN dendrites in the antennal lobe of D. melanogaster and D. sechellia, reported as normalised GCaMP6f fluorescence changes. Plots are based on the data in Supplementary Fig. 8. EC50 values [Log] are as follows: Or85b OSNs: −6.50 (Dmel), −6.51 (Dsec); VM5d PNs: –7.82 (Dmel), −7.87 (Dsec); Or22a OSNs: −7.42 (Dmel), −8.23 (Dsec); DM2 PNs: −7.97 (Dmel), −9.61 (Dsec). Genotypes are as follows. OSN imaging: D. melanogaster w;UAS-GCaMP6f/Orco-Gal4,UAS-GCaMP6f, D. sechellia w,UAS-GCaMP6f/w,UAS-GCaMP6f;;+/DsecOrcoGal4. PN imaging: D. melanogaster w;UAS-GCaMP6f/+;+/VT033008-Gal4 (VM5d PNs), D. melanogaster w;UAS-GCaMP6f/+;+/VT033006-Gal4 (DM2 PNs), D. sechellia w,UAS-GCaMP6f/w,VT033008-Gal4 (VM5d PNs), w,UAS-GCaMP6f/w,VT033006-Gal4 (DM2 PNs). i Responses of Or85b OSNs to pulsed odour stimuli (ten 200 ms pulses, each separated by 200 ms, as indicated by the black bars). For both species, left panels show the time course (mean ± SEM ΔF/F0) and right panels show the quantification of ΔF/F0 peak to the 1st and 10th stimulation. n = 8 animals each. Genotypes as in g. j, k Pulsed odour responses of VM5d PNs (j) and DM2 PNs (k). Mean ± SEM are shown in the time course. n = 8 animals each. Genotypes as in g, h. l, m Pulsed odour responses of DM4 (Or59b) and VA2 (Or92a) PNs (two control pathways where the number of partner OSNs is conserved between species (Fig. 1c)). Mean ± SEM are shown in the time course. n = 6 animals each. See Supplementary Fig. 11 for dose-response data. Genotypes are as for DM2 PN imaging in h. For a–f Student’s t test (two-sided) and for i–m paired t test (two-sided): ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, NS P > 0.05.

To substantiate and extend these observations, we expressed GCaMP6f broadly in OSNs or PNs and measured odour-evoked responses in specific glomeruli using two-photon calcium imaging. When measuring calcium responses to a short pulse of 2-heptanone in Or85b OSN axon termini in the VM5d glomerulus, we observed, as expected22, no sensitivity differences (Fig. 5g, Supplementary Fig. 8a). VM5d PNs also displayed no obvious increase in odour sensitivity in D. sechellia (Fig. 5g, Supplementary Fig. 8b), consistent with our patch clamp recordings (Fig. 5e). Next, we investigated Or22a OSNs and DM2 PNs after stimulation with the noni odour methyl hexanoate23. In this olfactory pathway, D. sechellia OSNs displayed responses at odour concentrations approximately two orders of magnitude lower than in D. melanogaster (Fig. 5h, Supplementary Fig. 8c), concordant with previous electrophysiological analyses22,23,26. D. sechellia DM2 PNs displayed a similar degree of heightened sensitivity compared to those in D. melanogaster, suggesting that an increased Or22a OSN number does not lead to further sensitisation of these PNs (Fig. 5h, Supplementary Fig. 8d). To test the sufficiency of differences in receptor properties22 to explain PN activity differences, we expressed D. melanogaster or D. sechellia Or22a in D. melanogaster Or22a neurons lacking the endogenous receptors, which we previously showed confers a species-specific odour response profile on these OSNs22. Measurement of responses to methyl hexanoate in DM2 PNs revealed higher sensitivity in animals expressing D. sechellia Or22a compared to those expressing D. melanogaster Or22a (Supplementary Fig. 8e); notably, this difference was similar in magnitude to the endogenous sensitivity differences of D. sechellia and D. melanogaster DM2 PNs. Together, the analyses of Or85b and Or22a pathways indicate that a larger OSN population does not contribute to enhanced PN sensitisation.

OSN number increases do not lead to increased reliability of PN responses

Pooling of inputs on interneurons has also been suggested to reduce the noise in central sensory representations, since spontaneous activity of each OSN is uncorrelated and becomes averaged out as OSN activities are summated at PNs44–46. This phenomenon should reduce the variability of PN response magnitude across multiple odour presentations. We therefore examined whether increased OSN number plays a role in reducing trial-to-trial variability in PN responses by comparing odour responses, and their variation, in VM5d PNs to eight trials of 2-heptanone stimulation. These experiments did not reveal any differences in PN response reliability between D. melanogaster and D. sechellia (Supplementary Fig. 9). Consistent with this calcium imaging analyses, the lack of a significant difference in VM5d PN spontaneous spiking frequency between species (Fig. 5d) also argues that increased sensory pooling in D. sechellia does not substantially reduce noise in this circuitry.

Pathways with increased OSN number display reduced decay magnitude of PN responses

Most natural odours exist as turbulent plumes, which stimulate OSNs with complex, pulsatile temporal dynamics32. To test if odour-evoked temporal dynamics in these olfactory pathways are influenced by OSN number, we repeated the calcium imaging experiments using ten consecutive, short pulses of odour. Or85b OSNs displayed a plateaued response to pulses of 2-heptanone in both D. melanogaster and D. sechellia, albeit with a slight decay over time in the latter species (Fig. 5i). D. melanogaster VM5d PNs showed decreasing responses following repeated exposure to short pulses, presumably reflecting adaptation, as observed in multiple PN types47. By contrast, VM5d PNs in D. sechellia displayed responses of similar magnitude throughout the series of odour pulses (Fig. 5j). This species difference in PN responses was also seen with long-lasting odour stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 10) and is consistent with a smaller difference between spiking frequencies at the start and end of odour stimulation in D. sechellia VM5d PNs measured by electrophysiological recordings (Fig. 5f, Supplementary Fig. 7b). Imaging the responses of Or22a OSN partner PNs in DM2 to pulsed odour stimuli (using concentrations of methyl hexanoate that evoked similar activity levels between the species, Fig. 5h) revealed a similar result: D. melanogaster DM2 PN responses decreased over time while D. sechellia DM2 PNs responses were unchanged in magnitude (Fig. 5k). However, for two olfactory pathways where the numbers of cognate OSNs are not increased in D. sechellia (Or59b/DM4 and Or92a/VA2, Fig. 1c), the PNs in both species displayed decreasing responses over the course of stimulations (Fig. 5l, m, Supplementary Fig. 11). Together, our data indicate that OSN number increases in D. sechellia’s noni-sensing pathways might result, directly or indirectly, in reduced decay magnitude of PN responses to dynamic or long-lasting odour stimuli.

Species-specific PN response properties are due, at least in part, to differences in lateral inhibition

More sustained PN responses in D. sechellia could be due to species differences in several aspects of glomerular processing, involving OSNs, PNs and/or LNs. We examined this phenomenon through calcium imaging in VM5d PNs before and after pharmacological inhibition of different synaptic components. Blockage of inhibitory neurotransmission—which is principally mediated by LNs acting broadly across glomeruli48–50—decreased adaptation in D. melanogaster VM5d PNs, as expected. This effect was predominantly due to inhibition of GABAB rather than GABAA/GluCl receptors (Supplementary Fig. 12a, b). By contrast, inhibitory neurotransmitter receptor blockage did not lead to changes in temporal dynamics of responses in D. sechellia (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Fig. 12a, b). These observations suggest that differences in the strength of inhibition between species contribute to differences in PN decay magnitude (see Discussion). We note that D. sechellia PNs displayed apparent decreases in odour response magnitude (as measured by ΔF/F) upon pharmacological treatment (Fig. 6a), but this effect is most likely due to elevated baseline activity (F0) in this species (Supplementary Fig. 12c).

Fig. 6. Mechanisms of sustained PN responses in D. sechellia.

a Odour pulse responses of VM5d PNs in D. melanogaster and D. sechellia following application of GABA receptor antagonists. PN responses in normal AHL saline (left) or containing 100 µM picrotoxin (PTX) + 50 µM CGP54626 (right). Time courses (mean ± SEM ΔF/F0) and quantification of ΔF/F0 peak to the 1st and 10th stimulation are shown. Genotypes as in Fig. 5g. b Odour pulse responses of VM5d PNs in D. melanogaster and D. sechellia following application of low doses (200 µM) of mecamylamine (nAChR antagonist) to weakly block cholinergic inputs. PN responses in normal AHL saline, mecamylamine and AHL saline wash-out are shown. Time courses (mean ± SEM ΔF/F0) and quantification are shown. n = 7 animals each. c Odour pulse responses of D. sechellia VM5d PNs in intact (top) and right antenna-ablated (bottom) animals, which halves the OSN input. Time courses (mean ± SEM ΔF/F0) and quantification are shown. n = 7 animals each. d Model illustrating the complementary effects of OSN sensitisation (due to receptor tuning) and reduced PN adaptation (putatively due to OSN population increases; see Discussion) on odour-evoked sensory representations. The schematised PN activities in the cartoon on the right represent the combination of both processes, which we speculate lead to more sensitive and persistent long-range olfactory attraction toward the noni host fruit by D. sechellia, but not D. melanogaster. For a–c paired t test (two-sided): ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05, NS P > 0.05. n = 8 animals each.

We next pharmacologically impaired cholinergic neurotransmission to diminish excitatory connections of OSNs, which include OSN-PN, as well as OSN-LN and some LN-LN synapses36,47,51,52. As expected, strong blockage essentially abolished odour-evoked PN responses (Supplementary Fig. 12d). More informatively, weak blockage led to enhanced decay in the VM5d PN responses of D. sechellia (Fig. 6b), as seen in untreated D. melanogaster (Fig. 6b). These observations suggest that excitatory neurotransmission from OSNs to PN and/or LNs also contributes to the temporal dynamics of PN responses. Consistent with this possibility, halving the number of OSN inputs in D. sechellia through removal of one antenna (OSN axons project to antennal lobes in both brain hemispheres36) enhanced the decay of this species’ VM5d PN responses (Fig. 6c). These data support the hypothesis that OSN number increases in D. sechellia modulate the response dynamics of partner PNs.

Discussion

Amongst the many ways in which animal brains have diverged during evolution, species-specific increases in the number of a particular neuron type are likely one of the most common. The genetic basis and physiological and behavioural consequences of such apparently simple changes have, however, remained largely unexamined. Here we have exploited an ecologically and phylogenetically well-defined model clade of drosophilids to study this phenomenon. We provide evidence that expansion of host fruit-detecting OSN populations in D. sechellia is a complex trait, involving contributions of multiple loci. Surprisingly, a larger number of OSNs does not result in sensitisation of partner PNs nor in increased reliability of their responses. Rather we observed more sustained responses of PNs upon repetitive or long-lasting odour stimulation. While OSN number alone can influence the strength and persistence of odour-tracking behaviour, this species-specific cellular trait is likely to synergise with increases in peripheral sensory sensitivity conferred by changes in olfactory receptor tuning properties21–23 to enable long-distance localisation of the host fruit by D. sechellia (Fig. 6d).

One important open question is how OSN population increases affect circuit properties and behaviour. For one experimentally-accessible glomerulus, VM5d, we observed that PNs (which are unchanged in number between species) have a larger surface area and form more synapses with OSNs but show lower dendritic input resistance in D. sechellia. This anatomical and physiological compensation results in the voltage responses of PNs being very similar between species despite the increased OSN input in D. sechellia. Such compensation might reflect in-built plasticity in glomerular microcircuitry. Indeed, within D. melanogaster, OSN number differs across glomeruli14 with commensurate differences in the number of OSN synapses with PN and LNs (Supplementary Fig. 13a36). Moreover, a previous study in D. melanogaster characterised the consequence of (random) differences in PN numbers in a glomerulus (DM6): in glomeruli with fewer PNs (i.e. greater sensory convergence per neuron), individual PNs had larger dendrites, formed more synapses with OSNs, and exhibited lower input resistance53, analogous to our observations in D. sechellia VM5d.

Species-specific physiological responses to prolonged or repetitive odour stimuli likely involves multiple neuron classes. In D. melanogaster, adaptation of PNs to long odour stimuli occurs through lateral inhibition by GABAergic LNs48,54, as we confirmed here. However, such inhibition appears to be weaker in D. sechellia in pathways with more OSNs. Given the conserved total number of antennal OSNs between species, more OSNs in one pathway could lead to stronger inhibitory neurotransmission from the correspondingly larger glomerulus to other unchanged (or smaller) glomeruli. Critically, this could result in net weaker lateral inhibition from these glomeruli onto the expanded glomerulus, as seen in D. sechellia (Fig. 6d). Excitatory cholinergic LNs might also contribute to such lateral inhibition by activating GABAergic LNs in response to OSN inputs55. We cannot exclude that LNs display species-specific innervations or connectivity—potentially influenced by shifts in glomerular position due to their volume changes—but testing this idea will require genetic drivers to visualise and manipulate subsets of this highly diverse neuron type56. Finally, we note that it is also possible that differences exist in the intrinsic physiology of PNs due to, for example, differential expression of ion channels between species. Such differences—potentially unrelated to changes in OSN number—might be revealed by mining comparative transcriptomic datasets for these drosophilids57.

Regardless of the precise mechanism, could more sustained PN responses convert to behavioural persistence? The main post-synaptic partners of PNs are lateral horn neurons and Kenyon cells, of which the latter (at least) have a high input threshold58 for sparse coding. Assuming the threshold of these neurons is commensurate with maximum PN firing rate (which is higher in D. melanogaster), the relaxed decay in PN activity in D. sechellia might elongate downstream responses to persistent odours, which could drive valence-specific behaviours59. Sensory habituation is advantageous for the brain to avoid information overload by attenuating constant or repetitive inputs and is a general feature across sensory modalities60. However, this phenomenon might be disadvantageous when navigating through sensory cues for a long period of time, for example, during olfactory plume-tracking. The reduced adaptation selectively in PNs in the expanded sensory pathways in D. sechellia that detect pertinent host odours provides an elegant resolution to this conflict in sensory processing, leaving conserved molecular effectors mediating synaptic neurotransmission and adaptation in other olfactory pathways intact.

Beyond D. sechellia, selective increases in ab3 neuron numbers have been reported in at least two other drosophilid species, which are likely to represent independent evolutionary events9,61 (Supplementary Fig. 13b). Furthermore, Or22a neurons display diversity in their odour specificity across drosophilids61,62. These observations suggest that this sensory pathway is an evolutionary “hotspot” where changes in receptor tuning and OSN population size collectively impact sensory processing, perhaps reflecting the potent behavioural influence of this pathway, as we have found in D. sechellia. More generally, given our demonstration of the important effect of OSN population size on host odour processing in D. sechellia, examination of how cell number increases modify circuit properties in other sensory systems, brain regions and species seems warranted.

Methods

Data reporting

Preliminary experiments were used to assess variance and determine adequate sample sizes in advance of acquisition of the reported data. All experiments (except for Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 2j) were performed with female flies. For electrophysiological recordings, data were collected from multiple flies on several days in randomised order. Within datasets, the same odour dilutions were used for acquisition of the data. The experimenter was blinded to the genotype for quantification of OSN numbers, and SPARC2-CsChrimson and SPARC2-TNT tethered fly assays, but not for other behavioural or physiological experiments.

Drosophila strains

Drosophila stocks were maintained on standard wheat flour/yeast/fruit juice medium or, for those used in PN electrophysiology experiments, semi-defined culture medium63 under a 12 h light:12 h dark cycle at 25 °C. For all D. sechellia strains, a few g of Formula 4-24® Instant Drosophila Medium, Blue (Carolina Biological Supply Company) soaked in noni juice (Raab Vitalfood or Tahiti Trader) were added on top of the standard food. Wild-type, mutant and transgenic Drosophila lines used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

To generate lozenge (lz) trans-heterozygous D. simulans/D. sechellia hybrid flies, we aged 25–35 virgin males of D. simulans (Dsim03 Or85bGFP or Dsim03 lzRFP;Or85bGFP) in groups for 6–7 days before combining them with 20–30 virgin females of D. sechellia (Dsec07 lzRFP;Or85bGFP or Dsec07 Or85bGFP). We lowered the fly food tube cap to restrict space and force interactions between the animals (which otherwise had a very low tendency to mate). Tubes were maintained at 22C with strong light exposure and flipped every 3–4 days into a new tube. Progeny were collected and phenotyped 7–10 days post-eclosion.

Constructs for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome engineering and transgenesis

D. simulans Or85b: for expression of a single sgRNA targeting the D. simulans Or85b locus, an oligonucleotide pair (Supplementary Table 2) was annealed and cloned into BbsI-digested pCFD3-dU6-3gRNA (Addgene #49410) as described64. To generate a donor vector for homologous recombination, homology arms (1–1.6 kb) were amplified from D. simulans (Drosophila Species Stock Centre [DSSC] 14021-0251.195) genomic DNA and inserted into pHD-Stinger-attP22 via restriction cloning. Both constructs were co-injected with a source of Cas9 (as described below) into D. simulans DSSC 14021-0251.003 and DSSC 14021-0251.004.

D. simulans and D. sechellia lz: to express multiple sgRNAs targeting the lz loci from the same vector backbone, oligonucleotide pairs (Supplementary Table 3) were used for PCR and inserted into pCFD5 (Addgene #73914) via Gibson Assembly, as described65. To generate donor vector for homologous recombination, homology arms (1–1.6 kb) were amplified from D. sechellia (DSSC 14021-0248.07) or D. simulans (DSSC 14021-0251.195) genomic DNA and inserted into pHD-DsRed-attP66 via Gibson Assembly. Species-specific constructs were co-injected with a source of Cas9 (as described below) into D. simulans DSSC 14021-0251.004 or D. sechellia nanos-Cas922.

D. sechellia UAS-SPARC2-D-CsChrimson: we digested a SPARC2-backbone vector (Addgene #133562) with SalI and inserted a CsChrimson-Venus cassette after PCR amplification from pBac(UAS-ChR2 CsChrimson,3xP3::dsRed) via Gibson Assembly. The resulting SPARC2-D-CsChrimson cassette was amplified via PCR and inserted via restriction cloning into pHD-3xP3-DsRed DattP-D. sechellia attP40 (this targeting vector for homologous recombination at the D. sechellia attP40-equivalent site will be described in more detail elsewhere).

D. sechellia UAS-SPARC2-D-TNT-HA-GeCO: we first generated a pHD-3xP3-DsRed_DattP-UAS-TNT-GeCO vector by amplifying a TNT-GeCO cassette from pHD-37.1_AttP5_LexAop_90_10_TNT-HA_p2A_jRGeCO1a together with a UAS cassette and insertion into pHD-3xP3-DsRed DattP via Gibson Assembly. Subsequently, we transferred the UAS-TNT-HA-GeCO cassette into pHD-3xP3-DsRed DattP-D. sechellia attP40 before assembling pHD-3xP3-DsRed DattP-D. sechellia attP40 SPARC2-D-TNT-HA-GeCO via Gibson Assembly (the GeCO calcium indicator was not used in the current study). Both SPARC2-D transgenic lines in D. sechellia were generated via CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homologous recombination at the attP40-equivalent site in D. sechellia. To test the functionality of the UAS-TNT-HA-GeCO cassette, we also generated UAS-TNT-HA-GeCO transgenic lines via homologous recombination at the attP40 locus in D. melanogaster and D. sechellia. However, in both species successful transformants did not survive pupariation, which was potentially due to low-level, Gal4-independent expression of the TNT effector.

D. melanogaster VT033006-LexA: to generate a VT033006-LexA construct, pLexA-SV40-attB was digested with NotI. A VT033006 enhancer fragment was PCR-amplified from pVT033006-Gal4-attB38. The insert and the linearised vector were joined by Gibson Assembly. The vector was integrated into D. melanogaster attP2 by BestGene Inc.

D. sechellia VT033006-Gal4, VT033008-Gal4 and VM5d-Gal4: constructs carrying the D. melanogaster enhancer sequences38 were integrated into Dsec-white (attP landing site on the X chromosome22) or Dsec-attP40 (see next section). The Dsec-nSyb-ΦC31 line was generated by integration of nSyb-ΦC31 (Addgene #133868) into Dsec-attP26 (see next section).

D. sechellia UAS-myrGFP: pUAS-myrGFP, QUAS-mtdTomato(3xHA)67 was integrated into Dsec-attP40.

D. sechellia UAS-Dα7:GFP: flies were generated by P-element-mediated transgenesis of p(UAS-Dα7:GFP)42 into D. sechellia DSSC 14021-0248.30 by WellGenetics.

D. sechellia pBac(UAS-CsChrimson-Venus): we first amplified a UAS-CsChrimson-Venus cassette from pUAS-ChR2 CsChrimson68 and a pBac backbone69 and combined both via Gibson Assembly resulting in pBac(UAS-CsChrimson-Venus). Subsequently, we digested pBac(UAS-CsChrimson-Venus) with AscI, amplified a 3xP3-DsRed cassette (derived from gene synthesis, GenetiVision) via PCR and combined both via Gibson Assembly resulting in pBac(UAS-CsChrimson-Venus,3xP3-DsRed). Primer sequences for intermediate cloning steps are listed in Supplementary Table 2. PiggyBac-mediated transgenesis of pBac(UAS-CsChrimson-Venus, 3xP3-DsRed) into D. sechellia DSSC 14021-0248.07 was performed in-house (see below) and the insertion site mapped to the third chromosome using TagMap70. Beyond its use for optogenetic experiments, we took advantage of the visible 3xP3-DsRed marker to use the same line for introgression mapping (Supplementary Fig. 2c, d).

All plasmids were verified via Sanger sequencing before injection. Full details and oligonucleotide sequences are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Drosophila transgenesis

Except for specific constructs described above, mutagenesis/transgenesis of D. sechellia, D. simulans and D. melanogaster was performed in-house following standard protocols22. For piggyBac and P-element transgenesis, we co-injected a piggyBac or P-element vector (300 ng µl−1) and piggyBac71 or P-element helper plasmid72 (300 ng µl−1). For CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homologous recombination, we injected a mix of an sgRNA-encoding construct (150 ng µl−1) and donor vector (500 ng µl−1) into D. sechellia nanos-Cas922 or co-injected with pHsp70-Cas9 (400 ng μl−1) (Addgene #45945) for D. simulans transgenesis73. Site-directed integration into attP sites was achieved by co-injection of an attB-containing vector (400 ng µl−1) and pBS130 (encoding ΦC31 integrase under control of a heat shock promoter (Addgene #26290)74). The Dsec-attP26 site (on chromosome 4) was generated via piggyBac-mediated random integration and Dsec-attP40 via CRISPR-mediated homologous recombination; both will be described in more detail elsewhere. All concentrations are given as final values in the injection mix.

Histology

Fluorescent RNA in situ hybridisation (using digoxigenin- or fluorescein-labelled RNA probes) and immunofluorescence on whole-mount antennae were performed essentially as described75,76. Probes were generated using D. sechellia genomic DNA (Or47a, Or88a) and primers listed in Supplementary Table 2. Other published probes were either targeting D. sechellia (Or42b, Or22a, Or85b, Or13a, Or98a, Or35a22), D. simulans (Or67a77) or D. melanogaster transcripts (Or56a, Or59b, Or9a, Or69aA78; Or19a15; Or83c, Or67d27); all probes were used at a concentration of 1:50. Immunofluorescence on adult brains—with the exception of the visualisation of dye-filled PNs (described below)—was performed as described79.

The following antibodies were used: guinea pig α-Ir75b 1:500 (RRID:AB_263109321), mouse monoclonal antibody nc82 1:10 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), rabbit α-GFP 1:500 (Invitrogen), and rat α-HA 1:500 (Roche). Alexa488-, Cy3- and Cy5-conjugated goat α-guinea pig, goat α-mouse, goat α-rabbit, and goat α-rat IgG secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes; Jackson Immunoresearch) were used at 1:500.

Image acquisition and processing

Except for dye-filled PN imaging and analysis (described below), confocal images of antennae and brains were acquired on an inverted confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 710) with an oil immersion 40× objective (Plan Neofluar 40× Oil immersion DIC objective; 1.3 NA). For quantification of synapse numbers, images were taken using a 63× objective (Plan-Apochromat 63× Oil immersion DIC M27; 1.4 NA) with a zoom of 3×, centring the image on the glomerulus of interest. Images were processed in Fiji80. D. sechellia brains were imaged and registered to a D. sechellia reference brain22 using the Fiji CMTK plugin (https://github.com/jefferis/fiji-cmtk-gui).

Cell number quantification: the number of OSNs expressing a specific Or was quantified using Imaris (Bitplane) or the Cell Counter tool in Fiji. For GFP-expressing Or85b OSNs for the QTL analysis, we imaged GFP and, in the 568 nm channel, cuticular autofluorescence. After subtraction of the cuticular fluorescence signal from the GFP signal using the Subtraction tool in Fiji, we quantified the number of GFP-positive nuclei using the Surface Detection tool in Imaris. For Ir75b neurons, we found that α-Ir75b immunofluorescence resulted in labelled cells having a range of intensities. To ensure that the cell quantifications were reproducible, counting was performed manually by three experimenters. Images resulting in disagreements were re-checked and either resolved or removed from the analyses.

Glomerular and synapse quantification: glomerular volumes were calculated following segmentation with the Segmentation Editor plugin of Fiji using the 3D Manager plugin. The number of post-synaptic sites per glomerulus was quantified in Imaris as described37, setting punctum size to 0.45 μm3 for all images.

Quantitative trait locus mapping

Or85b neuron phenotyping: flies expressing nuclear-localised GFP in Or85b neurons were placed individually into 96-well plates whose bottom was replaced by a metal mesh. Antennae were removed via shock-freezing in liquid nitrogen and collected in 4% paraformaldehyde-3% Triton-PBS as described75. After 3 h of fixation, antennae were washed twice in 3% Triton-PBS and twice in 0.1% Triton-PBS and mounted in Vectashield (Vectorlabs) on 30-well PTFE printed slides (Electron Microscopy Sciences) before imaging on a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope. The fly bodies were transferred (by inversion) into separate 96-well plates and frozen at −20 °C. Genomic DNA of individual flies was extracted using the ZR-96 Quick-gDNA MiniPrep kit (Zymo Research).

Ir75b neuron phenotyping: flies were processed as described above. For antennae, after washing in 0.1% Triton-PBS, Ir75b immunofluorescence was performed. Antennae were mounted in Vectashield (Vectorlabs) on 30-well PTFE printed slides (Electron Microscopy Sciences) before imaging on a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope.

Sequencing and genotyping: genomic DNA of individual flies was tagmented with in-house produced Tn5 as described81. In brief, Tn5 was charged with adaptors and mixed at a concentration of 5 ng μl−1 with 1 μl of genomic DNA. After segmentation, Tn5 was de-activated by the addition of 0.2% sodium dodecyl-sulphate, and sample-specific sequencing adaptors were added by PCR amplification. The resulting PCR amplicons were cleaned up with AMPure XP bead-based reagents (Beckman Coulter Life Science), DNA concentration and fragment distribution quantified on a fragment analyser (Agilent), and single-end sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq sequencer.

Data analysis: to align sequencing reads, the parental genomes dsim r2.02 and dsec r1.3 were used. Introgressed genomic regions were inferred using MSG software (http://www.github.com/JaneliaSciComp/msg). Output of MSG was thinned using the “pull_thin” utility (http://www.github.com/dstern/pull_thin) and read into R (v4.4.1) using the “read_cross_msg” utility (http://www.github.com/dstern/read_cross_msg). QTL mapping was carried out with the “scanone” function in R’s “qtl library” (v1.5) using the Haley-Knott regression method, and significance was determined using 1000 permutation tests (n.perm = 1000). For the Or85b neuron mapping experiment, tests for interactions between the QTL on chromosomes 3 and X were performed using the “fitqtl” function.

Two-photon calcium imaging

Animal preparation: flies of the appropriate genotype (described in the respective figure legends) were collected (females and males co-housed) and reared in standard culture medium, with addition of a noni juice supplement for D. sechellia (see above). Female flies aged 5–8 days after eclosion were used for the experiments.

Sample preparation: flies were anaesthetised by placing them into an empty tube that was cooled on ice for no longer than ~10 min. Further steps were performed under a dissection microscope, adapting a previous protocol82. A small drop of blue light-curing glue (595987WW, Ivoclar Vivadent) was placed on top of the copper grid (G220-5, Agar Scientific). Single flies were introduced into the mounting block, fixing the back of the fly head to the copper grid with the curing glue. The fly head was slightly bowed down with forceps (to achieve antennal lobe imaging from the dorsal side) while the blue-curing light (bluephase C8, Ivovlar Vivadent; placed at least 1 cm from the fly to avoid tissue damage) was focused. We avoided using the wire that was previously used to pull down the antennal plate22,82, as we found that it very frequently damaged the antennal nerves and therefore disrupted central olfactory responses, particularly in D. sechellia; the cactus spine and screw previously used to immobilise the fly head were also no longer necessary. An antennal shield82 was placed over the top of the fly head with the hole positioned centrally, fixed with beeswax to the top of the mounting block. Two-component silicone (Kwik-Sil, World Precision Instruments) was mixed with a toothpick and poured into the hole of the antennal shield to seal the gap between the plate and the fly head, avoiding any leakage onto the antennae. As the silicone was left to harden (during 10–15 min), we used blunt forceps to gently remove silicone on the cuticle on top of the head capsule. A drop of adult haemolymph (AHL) saline (108 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 8.2 mM MgCl2, 4 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM trehalose, 10 mM sucrose, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) was added into the hole of the antennal shield. Using a blade-splitter, a small rectangular hole was cut in the head cuticle between the eyes and above the antennal plate. Tracheae and glands above the brain were removed with fine forceps. Finally, the brain was rinsed with AHL saline at least 3 times until the antennal lobe appeared clear under the dissection microscope.

Odorant preparation: serial dilutions of odours were prepared in a fume hood. The solvents used for odour dilutions were different between glomeruli, as some glomeruli were extremely responsive to particular solvents: Or85b/VM5d (2-heptanone (Sigma-Aldrich, CAS 110-43-0) in dichloromethane (DCM)), Or22a/DM2 (methyl hexanoate (Sigma-Aldrich, CAS 106-70-7) in paraffin oil), Or59b/DM4 (methyl butyrate (Sigma-Aldrich, CAS 623-42-7) in DMSO (for dose-responses) or paraffin oil (for pulsed stimuli)), Or92a/VA2 (2,3-butanedione (Sigma-Aldrich, CAS 431-03-8) in paraffin oil). Or85b/VM5d neurons were especially sensitive to odorant contamination, so we prepared a new set of 2-heptanone dilutions when solvent responses started to become evident (approximately every two weeks). Furthermore, before preparing 2-heptanone and methyl butyrate, we washed the odour-containing vial, lid, and pipetting tips with DCM and DMSO, respectively. As DCM is highly volatile at room temperature, 2-heptanone/DCM odour dilutions were stored at 4 °C.

Image acquisition: images were acquired using a commercial upright two-photon microscope (Zeiss LSM 710 NLO). An upright Zeiss AxioExaminer Z1 was fitted with a Ti:Sapphire Chameleon Ultra II infra-red laser (Coherent) as excitation source. Images were acquired with a 20× water dipping objective (Plan-Apochromat 20× W; NA 1.0), with a resolution of 128 × 128 pixels (0.8926 pixels µm−1) and a scan speed of 6.30 µs pixel−2 (for one-time odour stimulation) or 3.15 µs pixel−2 (for pulse train odour stimulation). The excitation wavelength was set to 930 nm. The output power was modified according to the baseline fluorescence of GCaMP6f, which varied substantially between animals (except for pharmacology experiments, where laser output was fixed to enable comparison of raw fluorescence across animals). The power was set such that the baseline fluorescence was above the detection limit, and that the maximum fluorescence was below saturation, and thereafter unchanged for a given animal. Emitted light was filtered with a 500-550 nm band-pass filter, and photons were collected by an internal detector. Each measurement consisted of 50 images acquired at 4.17 Hz (for one-time odour stimulation) or 8.34 Hz (for pulse train odour stimulation), with stimulation starting ~5 s after the beginning of the acquisition and lasting for 1 s (for one-time odour stimulation) or 200 ms followed by a 200 ms interval repeated ten times (for pulse train odour stimulation).

Olfactory stimulation: antennae were stimulated using a custom-made olfactometer22,82. In brief, antennae were permanently exposed to air flowing at a rate of 1.5 l min−1 by combining a main airstream of humidified room air (0.5 l min−1) and a secondary stream (1 l min−1) of normal room air. Both air streams were generated by vacuum pumps (KNF Neuberger AG) and the flow rate was controlled by two independent rotameters (Analyt). The secondary airstream was guided either through an empty 2 ml syringe or through a 2 ml syringe containing 20 µl of odour or solvent on a small cellulose pad (Kettenbach GmbH) to generate odour pulses. To switch between control air and odour stimulus application, a three-way magnetic valve (The Lee Company, Westbrook, CT) was controlled using MATLAB via a VC6 valve controller unit (Harvard Apparatus). The order of the odour stimuli was always from lower to higher concentrations, preceded by the solvent control. Successive odour stimulations were separated by 1 min intervals.

Pharmacology: for pharmacological experiments, drugs were diluted in AHL saline to the following final concentrations: 100 µM picrotoxin (P1675-1G, Sigma-Aldrich, CAS 124-87-8), 50 µM CGP54626 hydrochloride (1088/10, TOCRIS, CAS 149184-21-4), 200 µM (low dose) or 2 mM (high dose), mecamylamine hydrochloride (M9020-5MG, Sigma-Aldrich, CAS 826-39-1). Drugs were applied to the fly after normal recording (“saline” or “naïve”) by exchanging the AHL saline with drug-diluted saline five times and incubating the preparation for a further 15-40 min before performing further recordings. For mecamylamine application experiments, samples were subsequently washed with AHL saline five times and incubated for 15-40 min, followed by another recording session (“Washed-out”). The lens was meticulously washed with ultrapure water between each session.

Data analyses: data were processed using Fiji and custom-written scripts in R. First, the image stacks were passed through the StackReg plugin83 (transformation: Rigid Body) to correct for movement artefacts. Using Fiji, a circular region of interest (ROI) was set within the glomerulus of interest on the left half of the brain image (except when the signal was weak, in which case the right half of the image was used). The signal intensity averaged across the ROI for each timeframe (hereafter F) was used to calculate the normalised signal ΔF/F0 = . Here, F0 (baseline fluorescence) was calculated as the average F during frames 16–19 (1 s before olfactory stimulus onset). The peak ΔF/F0 value (which represents the odour response intensity) was calculated as the maximum ΔF/F0 value during frames 20–23 (1 s during olfactory stimulation). We noticed that the maximum ΔF/F0 value itself was often very different between species/genotypes, presumably due to different expression levels of GCaMP6f. This should, in theory, not affect the normalised ΔF/F0 value, but we did observe a saturation of neuronal responses above a certain odour concentration, even if the peak ΔF/F0 value was lower than in other species/genotypes. To compare the dose-response effect between species and genotypes, we further introduced a normalisation step. Normalised peak response for each odour dilution () was calculated as follows: . Here, denotes peak ΔF/F0 value of a given dilution (median value across animals), denotes maximum among all the dilutions, and denotes from the minimum response. Thus, the normalised peak response takes a value between 0 and 1, where 0 means absence of odour responses and 1 means saturation. This step allowed us to compare the dose-response curve based on the relative response within species and genotypes, regardless of the absolute ΔF/F0 value. Dynamic ranges were quantified as in each animal rather than taking the median values across animals.

Photoactivation

Animal preparation: flies of the appropriate genotype (see figure legends) were collected, reared and prepared in the same way as for the two-photon calcium imaging. Female flies aged 6-9 days after eclosion were used for the experiments.

Photoconversion and image acquisition: the hardware setup was the same as in two-photon calcium imaging. Glomerular location was identified by a brief 930 nm scan of the entire antennal lobe. An oval ROI was placed inside the glomerulus of interest, where the ROI was made small enough so that the movement during photoconversion did not result in non-specific labelling. Where non-specific labelling was observed after imaging, data were excluded from further analyses. During photoconversion, the resolution was set to 512 × 512 pixels (3.5704 pixels µm−1) and the scan speed to 0.79 µs pixel−2. Excitation wavelength was shifted to 760–780 nm with a power output of 5–15%. Photoconversion was performed by scanning inside the ROI repeatedly (in a single z plane) for ~15 min. Around 5 min after the beginning of the session, a brief 930 nm scan was performed to check the conversion efficacy and specificity. If photoconversion was weak at this point, we increased the power output. The sample was then placed in a humidified chamber for 30–60 min to allow the diffusion of photoconverted C3PA-GFP. Finally, the fly’s body was removed to reduce motion artefacts and the sample placed again under the two-photon microscope. For imaging, the resolution was set to 1024 × 1024 pixels (2.3803 pixels µm−1) and the scan speed to 1.58–3.15 µs pixel−2. The excitation wavelength was shifted back to 930 nm with the power output adjusted to enable visualisation of neurite processes. Z-stack images were obtained with a spacing of 1 µm.

Electrophysiology

Single sensillum recordings: single sensillum electrophysiological recordings were performed essentially as described22,84, using 5-7 day-old female flies, which were grown on standard medium mixed with 0.2 mM all-trans retinal68 and, for D. sechellia, addition of 10% noni juice. Optogenetic stimulation was performed by exposing one antenna with increasing light intensities via an optic fibre as described in the Tethered fly assay section (see below). In SPARC2-D experiments, ab3 sensilla were identified by location and the use of diagnostic odours. For the data shown in Fig. 3c, light-sensitive (experimental group) and non-responding neurons (control) were analysed. Corrected responses were calculated as the number of spikes in a 0.5 s window from the beginning of illumination, subtracting the number of spontaneous spikes in a 0.5 s window 2 s prior to illumination, and multiplying by 2 to obtain spikes s−1. Recordings were performed on a maximum of three sensilla per fly. Exact n values and mean spike counts for all experiments are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings: for in vivo VM5d PN recordings, flies were prepared and dissected as described85. Female flies aged 1–2 days post-eclosion were used for the experiments; one neuron was recorded per brain. The internal patch pipette solution contained 140 mM potassium aspartate, 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, 4 mM MgATP, 0.5 mM Na3GTP, 1 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid, 1 mM KCl and, for cell labelling described below, 13 mM biocytin hydrazide. The pH was adjusted to 7.3, and the osmolarity was adjusted to ~265 mOsm. The external saline contained 103 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 5 mM N-tris(hydroxymethyl) methyl-2-aminoethane-sulphonic acid, 8 mM trehalose, 10 mM glucose, 26 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 1.5 mM CaCl2, and 4 mM MgCl2. The osmolarity was adjusted to 270–273 mOsm, and the saline was bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and reached an equilibrium pH of 7.3. Saline was continuously superfused over the fly during recording. Recordings were acquired with an Axopatch 700B or 200B model amplifier, low-pass filtered at 4 or 5 kHz, and digitised at 10 kHz. Patch pipettes, made from borosilicate glass, were pressure-polished. The estimated final pipette tip opening was less than 1 μm in diameter, and the pipette resistance was 15–45 MΩ.

Olfactory stimulation: serial dilutions of 2-heptanone (in mineral oil) were freshly prepared before each experiment. A custom-made olfactometer was used to deliver odour to flies. Antennae were consistently exposed to a stream of air at 363 ml min−1. Another stream of air (5.3 ml min−1) was directed through a solenoid valve into a 2 ml vial (Thermo Scientific, National C4011-5W) containing either mineral oil alone or an odour solution in mineral oil. Odour delivery, controlled by a custom MATLAB script and a three-way solenoid valve (The Lee Company, Westbrook, CT), lasted 2 s. The series of stimuli always started with the solvent control followed by increasing odour concentrations. Custom-written MATLAB scripts were used to detect spikes based on the first derivative of the voltage trace. A threshold was set for each recording and all spikes were visually inspected to eliminate both false positive and false negative detections. The spike time was defined as the time of the peak of the first derivative of the voltage waveform. An average of three trials was taken for each concentration for each cell. Corrected responses were calculated as the spike rate in a 50 ms (Fig. 5e, Supplementary Fig. 7b) or 500 ms (Supplementary Fig. 7b) window and subtracting the spontaneous spike rate (computed in a 500 ms window 2 s prior to stimulation). Exact n values and mean spike counts for all experiments are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

PN backfilling and reconstruction: each brain was dissected out of the head capsule after the recording and fixed with 4% PFA (w/v) in PBS for 20 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS-T [PBS with 0.2% (v/v) Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, #X-100)], brains were incubated with streptavidin Alexa Fluor 568 (1:1000) (Invitrogen S11226), nc82 (1:50) and 10% Normal Goat Serum in 0.2% PBS-T overnight at RT. The brains were washed and incubated with streptavidin Alexa Fluor 568 (1:1000), anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 633 (1:500) and 10% Normal Goat Serum in 0.2% PBS-T overnight. After the final wash with PBS, brains were mounted in Vectashield H-1000 (Vector Laboratory, Burlingame, CA) anti-fade mounting medium for confocal microscopy. Brains were imaged with a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope. Confocal images displayed Biocytin fills in all recordings, and dendritic surface area was measured using Imaris 10.0.0 (Bitplane) through a semi-automated generation of surfaces for each dendritic arbour.

For one D. melanogaster recording, the biocytin fill revealed two coupled cells: one innervating the VM5d glomerulus and the other innervating a different glomerulus. Correspondingly, two distinct spike waveforms were clearly discernible in the voltage trace. We excluded this recording from membrane voltage and input resistance analyses but included it in spike rate analysis because the VM5d PN spikes could be identified by their clear responses to 2-heptanone. The VM5d arbour in this fill was included in the dendritic morphology analysis.

Tethered fly assay