Abstract

Background:

Social media has become an integral part of adolescent life in Indonesia, particularly in tourism regions. It serves as a platform for disseminating information, including about HIV/AIDS. However, it also has the potential to spread misinformation and harmful content, which can increase stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA).

Aim:

The aim of this study was to determine the relationships between social media use, knowledge, and attitudes towards PLWHA among high school students in an Indonesian tourism region.

Methods:

This research utilized a school-based cross-sectional study design in several high schools located in Bukittinggi City, a renowned tourist destination in West Sumatra Province, Indonesia. The study sample comprised high school students aged 15-18 years, with a total of 118 respondents selected. The sample was chosen using a multistage stratified clustered sampling method. The variables measured in this study included social media usage, HIV/AIDS knowledge, and attitudes towards PLWHA. To test the research hypotheses, data analysis was conducted using structural equation modeling techniques. P<0.05 is considered significant.

Results:

There were relationships between social media use and knowledge of HIV/AIDS (β=0.614, t-value=9.327, p-value=<0.001), knowledge of HIV/AIDS and attitudes towards PLWHA (β=0.601, t-value=8.344, p-value=0.014) and social media use and attitudes towards PLWHA (β=0.218, t-value=2.469, p-value=<0.001).

Conclusion:

This study confirmed significant relationships were found between social media use, knowledge, and attitudes towards PLWHA. The results highlight the necessity for comprehensive interventions and ongoing support to promote the well-being of students amid the dynamic changes in global tourism.

Keywords: Social media, Knowledge, Attitudes, HIV/AIDS, Students, Tourism regions

Introduction

HIV/AIDS has become a significant global health concern, and Indonesia has seen an increase in new cases. Adolescents are especially at risk of contracting HIV/AIDS (Mahendradhata et al., 2019; Magnani et al., 2022; Nindrea et al., 2023). In Indonesia, as of 2020, there were 540,000 people living with HIV, with a prevalence rate of 0.4% among adults aged 15–49. Among those affected, the largest proportion of HIV/AIDS cases (59.1%) were high school graduates (Jocelyn et al., 2024).

Social media has become an integral part of adolescent life in Indonesia, particularly in tourism regions. It serves as a platform for disseminating information, including about HIV/AIDS (Ibrahim et al., 2024). However, it also has the potential to spread misinformation and harmful content, which can increase stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) (Iribarren et al., 2018). Adolescents’ knowledge and attitudes towards HIV/AIDS are crucial in preventing its spread (Cao et al., 2017). Those who are well-informed about HIV/AIDS and hold positive attitudes towards people living with the disease are more likely to avoid risky behaviors and offer support to those affected (Elghazaly et al., 2023; Mahat, 2019).

Tourism regions in Indonesia have significant potential for the spread of HIV/AIDS due to high sexual activity in these busy areas (Jocelyn et al., 2024; Mahendradhata et al., 2019). This study aims to explore the role of social media, and the knowledge and attitudes of adolescents towards HIV/AIDS in these regions. Therefore, this research can contribute to efforts to prevent HIV/AIDS among adolescents and raise public awareness of the importance of HIV/AIDS education and campaigns through social media.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

The study employed a cross-sectional design conducted in September 2023 at several high schools in Bukittinggi City. This city is renowned as a tourist destination in West Sumatra Province, Indonesia.

Study sample

The study sample comprised high school students aged 15-18 years, whose names were included in the education office registry. The sample size of 118 respondents was determined using the proportion sample formula. Inclusion criteria included being aged 15-18 years, able to read and write in Bahasa Indonesia, while exclusion criteria included being absent or not enrolled in high school at the time of the study. Sample selection utilized multistage stratified clustered sampling.

Measures

The constructs in this study were defined and measured using dependable and validated scales that were previously introduced in well-regarded peer-reviewed journals. Social media use was assessed through two questions: whether individuals delivered messages related to HIV prevention, and if their posts indicated risk behaviors related to overdose and being in an HIV risk group (such as injection drug use, history of drug overdose, inconsistent condom use, number of sexual partners, and engaging in sex in exchange for drugs) (Ibrahim et al., 2024). Knowledge about HIV refers to an individual’s understanding of basic facts related to HIV/AIDS, including information about transmission, symptoms, prevention, and management of the disease (Elghazaly et al., 2023). Attitudes towards PLWHA were assessed based on students’ attitudes towards facts, stigma, discrimination against vulnerable individuals who have been infected with HIV/AIDS, and their willingness to be active agents in fighting HIV/AIDS (Maehara et al., 2019).

Data collection

The study involved conducting interviews using a research questionnaire. Prior to the interviews, informed consent was obtained, and students were assured that they could decline participation without facing any consequences within or outside the school. To ensure confidentiality, respondents’ names were not disclosed, and the school’s name was kept anonymous to prevent any potential repercussions.

Ethical approval

This research had obtained approval from the research ethics committee, Dr. M. Djamil General Hospital, Padang, Indonesia (No. DP.04.03/D.XVI.XI/537/2023).

Data analysis

In this study, descriptive data were displayed using frequencies, percentages, and median values, analyzed with SPSS version 25.0. SmartPLS was employed to assess the reliability and validity of the measures, including Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). Furthermore, structural equation modeling (SEM) techniques were utilized to test the research hypotheses, with significance set at p<0.05.

Results

Characteristics of respondents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents

| Variables | Value (n=118) |

|---|---|

| Sex, f(%) | |

| Male | 46 (39.0) |

| Female | 72 (61.0) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 17 (14-18) |

| Family income, f(%) | |

| < regional minimum wage | 86 (72.8) |

| ≥ regional minimum wage | 32 (27.2) |

| Number of family members, median (IQR) | 5 (2-9) |

| Father’s education, f(%) | |

| Low (< Senior high school) | 44 (37.3) |

| Moderate (Senior high school) | 53 (44.9) |

| High (University) | 21 (17.8) |

| Mother’s education, f(%) | |

| Low (< Senior high school) | 29 (24.6) |

| Moderate (Senior high school) | 51 (43.2) |

| High (University) | 38 (32.2) |

| Father’s occupation, f(%) | |

| Government employee | 9 (7.6) |

| Private sector employee | 6 (5.1) |

| Entrepreneur | 38 (32.2) |

| Small-scale merchant | 17 (14.4) |

| Farmer | 12 (10.2) |

| Others | 36 (30.5) |

| Mother’s occupation, f(%) | |

| Government employee | 18 (15.3) |

| Private sector employee | 6 (5.1) |

| Entrepreneur | 15 (12.7) |

| Small-scale merchant | 5 (4.2) |

| Farmer | 2 (1.7) |

| Housewife | 72 (61.0) |

Table 1 shows that the majority of respondents were female (61.0%) and male (39.0%). The median age of the respondents was 17 years. More than half of the respondents had a family income less than the regional minimum wage (72.8%). The median number of family members was 5. The most common education level for both fathers and mothers was moderate. The most common occupation for fathers was entrepreneur (32.2%), and for mothers, it was housewife (61.0%).

Results of confirmatory factor analysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis

| Constructs/ factors | Standardized factor loadings |

|---|---|

| Social media use (α =0.845; CR=0.856; AVE=0.662) | |

| SM1 - Deliver messages related to HIV prevention | 0.742 |

| SM2 - Posts indicated risk behaviors related to overdose and being in an HIV risk group (such as injection drug use, history of drug overdose, inconsistent condom use, number of sexual partners, and engaging in sex in exchange for drugs) | 0.731 |

| Knowledge of HIV/AIDS (α =0.872; CR=0.832; AVE=0.676) | |

| K1- HIV is contagious | 0.812 |

| K2 - HIV does not get transmitted through daily contact and using public bathrooms | 0.853 |

| K3 - HIV does not transmit by contacting saliva, tears, and sweat | 0.871 |

| K4 - HIV does not transmit through coughing and sneezing | 0.778 |

| K5 - HIV is transmitted by blood transfusion | 0.780 |

| K6 - HIV is sexually transmitted | 0.801 |

| K7 - HIV-infected person may look healthy and feel healthy | 0.880 |

| K8 - HIV-infected individuals develop signs of the infection quickly | 0.778 |

| K9 - HIV patients can transmit the virus at any disease stage | 0.866 |

| K10 - HIV is not curable | 0.823 |

| Attitudes towards PLWHA (α =0.889; CR=0.853; AVE=0.678) | |

| A1 - I do not want to give salaam when greeting someone who is HIV/AIDS positive | 0.774 |

| A2 - Adolescents who are HIV-positive should be banned from attending schools with HIV-negative students | 0.784 |

| A3 - Adolescents who are HIV-positive should not swim in a pool with HIVnegative students | 0.811 |

α = Cronbach’s alpha; CR, composite reliability; AVE, average variance extracted

Table 2 indicated that all standardized factor loadings were > 0.60 and statistically significant (p<0.05). The reliability of the variables was assessed using Cronbach’s α values, all of which exceeded ≥ 0.70, indicating that the variables were reliable. To gauge the convergent validity of the scales, we considered three criteria. Firstly, all indicator loadings were > 0.70. Secondly, the composite reliabilities (CR) surpassed 0.8. Thirdly, the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct ≥ 0.5. These results confirmed satisfactory convergent validity for the research constructs.

Results of discriminant validity (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of discriminant validity

| No | Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Social media use | 0.723 | ||

| 2 | Knowledge of HIV/AIDS | 0.261 | 0.736 | |

| 3 | Attitudes towards PLWHA | 0.322 | 0.295 | 0.742 |

Italicized values on the diagonal indicate the AVE, while the remaining values represent the squared interconstruct correlations.

Table 3 assessed discriminant validity, which measures the extent to which measures of three variables were empirically distinct. The AVE of each latent construct had to be greater than the squared correlations between that construct and the rest of the latent constructs. This analysis demonstrated that these conditions for discriminant validity were fulfilled.

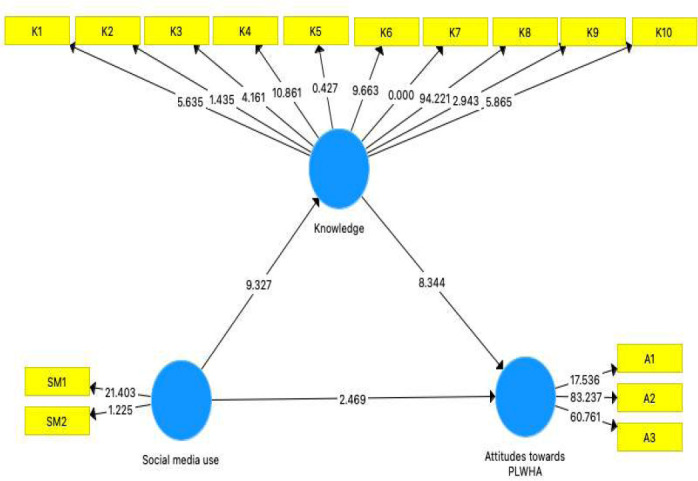

Findings regarding the hypothesized relationships (Table 4 and Figure 1).

Table 4.

Results of the relationships of social media use, knowledge, and attitudes towards PLWHA among high school students in an Indonesian tourism region

| Path specified | Coefficient (β) | t-value | p-value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social media use -> Knowledge of HIV/AIDS | 0.614 | 9.327 | <0.001 | Accepted |

| Knowledge of HIV/AIDS -> Attitudes towards PLWHA | 0.601 | 8.344 | 0.014 | Accepted |

| Social media use -> Attitudes towards PLWHA | 0.218 | 2.469 | <0.001 | Accepted |

Figure 1.

Findings regarding the hypothesized relationships

Table 4 and Figure 1 illustrate that there were relationships between social media use and knowledge of HIV/AIDS (β=0.614, t-value=9.327, p-value=<0.001), knowledge of HIV/AIDS and attitudes towards PLWHA (β=0.601, t-value=8.344, p-value=0.014) and social media use and attitudes towards PLWHA (β=0.218, t-value=2.469, p-value=<0.001).

Discussion

The results of this study showed a significant relationship between social media use, knowledge about HIV/AIDS, and attitudes towards PLWHA among high school students in the tourist area of Bukittinggi. This reflected how social media could function as an effective educational tool in enhancing understanding of HIV/AIDS (Aghaei et al., 2023). On the other hand, this phenomenon also underscored the importance of quality control over the information disseminated through social media platforms to ensure that the information received by teenagers was accurate and did not add to the stigma against PLWHA (Yu et al., 2023).

Previous study had shown that social media use could influence teenagers’ knowledge and attitudes towards HIV/AIDS (Ibrahim et al., 2024). Several studies found that social media could be a significant source of health information, including about HIV/AIDS (Magnani et al., 2022; Lipoeto et al., 2020; Nindrea et al., 2018). Good knowledge about HIV/AIDS was crucial for forming positive attitudes and reducing stigma towards PLWHA (Iribarren et al., 2018; Harahap et al., 2017). However, previous research also indicated that misinformation or stigma spread on social media could influence negative attitudes towards PLWHA (Cao et al., 2017).

The strength of this study was that it was the first to investigate social media use, knowledge, and attitudes towards PLWHA among high school students in an Indonesian tourism region. However, this study had several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limited the ability to draw causal conclusions. Second, the study was conducted in only one tourist city in Indonesia, so the results might not be generalizable to other areas with different characteristics. Third, the measurement of variables was based on self-reports, which could be prone to respondent bias. Lastly, social media use was measured in general terms without considering the specific types or content consumed by the respondents.

Based on the findings of this study, it is recommended to develop health education programs that utilize social media more effectively to deliver accurate information about HIV/AIDS. Additionally, further research with a longitudinal design is needed to confirm the causal relationships between social media use, knowledge, and attitudes towards PLWHA. Studies conducted in various regions with different demographic and social characteristics are also necessary to broaden the generalizability of the findings. Finally, it is important to develop strategies to minimize bias in self-reports by integrating additional measurement methods such as observations or in-depth interviews.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into the relationships among social media use, knowledge, and attitudes towards PLWHA among high school students in an Indonesian tourism region. The findings underscore the need for holistic interventions and continuous support to ensure the well-being of students in the evolving landscape of global tourism.

Acknowledgments

The authors thanked all the respondents who participated in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared that there is no conflict of interest associated with this study.

List of Abbreviations:

- AVE:

Average variance extracted:

- BMI:

Body mass index:

- CI:

Confidence interval;

- CR:

Composite reliability;

- PLWHA:

People living with HIV/AIDS

References

- 1.Aghaei A, Sakhaei A, Khalilimeybodi A, Qiao S, Li X. Impact of Mass Media on HIV/AIDS Stigma Reduction:A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 2023;27(10):3414–3429. doi: 10.1007/s10461-023-04057-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao B, Gupta S, Wang J, Hightow-Weidman L.B, Muessig K.E, Tang W. Social Media Interventions to Promote HIV Testing, Linkage, Adherence, and Retention:Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2017;19(11):e394. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elghazaly A, AlSaeed N, Islam S, Alsharif I, Alharbi L, Al Ashagr T. Assessing the knowledge and attitude towards HIV/AIDS among the general population and health care professionals in MENA region. PLoS One. 2023;18(7):e0288838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0288838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harahap W.A, Ramadhan R, Khambri D, Haryono S, Dana Nindrea R. Outcomes of trastuzumab therapy for 6 and 12 months in Indonesian national health insurance system clients with operable HER2-positive breast cancer. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2017;18(4):1151–1156. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.4.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ibrahim K, Kahle E.M, Christiani Y, Suryani S. Utilization of Social Media for the Prevention and Control of HIV/AIDS:A Scoping Review. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2024. 2024;17:2443–2458. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S465905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iribarren S.J, Ghazzawi A, Sheinfil A.Z, Frasca T, Brown W, Lopez-Rios J. Mixed-Method Evaluation of Social Media-Based Tools and Traditional Strategies to Recruit High-Risk and Hard-to-Reach Populations into an HIV Prevention Intervention Study. AIDS and Behavior. 2018;22(1):347–357. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1956-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jocelyn J, Nasution F.M, Nasution N.A, Asshiddiqi M.H, Kimura N. H, Siburian M.H.T. HIV/AIDS in Indonesia:current treatment landscape, future therapeutic horizons, and herbal approaches. Frontiers in Public Health. 2024;12:1298297. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1298297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipoeto N.I, Masrul M, Nindrea R.D. Nutritional contributors to maternal anemia in Indonesia:Chronic energy deficiency and micronutrients. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2020;29(Suppl 1):S9–S17. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.202012_29(S1).02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maehara M, Rah J, Roshita A, Suryantan J, Rachmadewi A, Izwardy D. Patterns and risk factors of double burden of malnutrition among adolescent girls and boys in Indonesia. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0221273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahat G. Relationships Between Adolescents'Knowledge, Attitudes, and Fears Related to HIV/AIDS. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2019;33(3):292–301. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.33.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahendradhata Y. Proceed with caution:Potential challenges and risks of developing healthcare tourism in Indonesia. Global Public Health. 2019;14(3):340–350. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2018.1504224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magnani R.J, Wirawan D.N, Sawitri A.A.S, Mahendra I.G.A.A, Susanti D, Utami N.K.A.D. The short-term effects of COVID-19 on HIV and AIDS control efforts among female sex workers in Indonesia. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01583-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nindrea R.D. Impact of Telehealth on the Environment During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2023;35(2-3):227. doi: 10.1177/10105395231152580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nindrea R.D, Harahap W.A, Aryandono T, Lazuardi L. Association of BRCA1 promoter methylation with breast cancer in Asia:a meta- analysis. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2018;19(4):885–889. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.4.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu F, Hsiao Y.H, Park S, Kambara K, Allan B, Brough G. The Influence of Anticipated HIV Stigma on Health-related Behaviors, Self-rated Health, and Treatment Preferences Among People Living with HIV in East Asia. AIDS and Behavior. 2023;27(4):1287–1303. doi: 10.1007/s10461-022-03865-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]