Abstract

Background

This joint clinical perspective by the Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) and Obesity Action Coalition (OAC) provides clinicians an overview of the role of advocacy in improving the lives of patients living with the disease of obesity, as well as describes opportunities how to engage in advocacy.

Methods

This joint clinical perspective is based upon scientific evidence, clinical experiences of the authors, and peer review by the OMA leadership. The Obesity Medicine Association is the largest organization of physicians, nurse practitioners, physician associates, and other clinical experts (i.e., over 5000 members at time of print) who are engaged in improving the lives of patients affected by the disease of obesity. The OAC is a national nonprofit organization of more than 80,000 members who are dedicated to serving the needs of individuals living with obesity.

Results

Advocacy involves educational and public policy initiatives that through relationships, networks, and targeted strategies and tactics (e.g., traditional media, social media, petitions, and direct communication with policy makers), promote public awareness and establish public policies that help mitigate bias, stigma, and discrimination, and generally improve the lives of patients living with the disease of obesity.

Conclusions

An objective of advocacy is to foster collective involvement and community engagement, leading to collaborations that help empower patients living with obesity and their clinicians to seek and achieve changes in policy, environment, and societal attitudes. Advocacy may also serve to enhance public awareness, promote prevention, advance clinical research, develop safe and effective evidenced-based therapeutic interventions, and facilitate patient access to comprehensive and compassionate treatment of the complex disease of obesity.

Keywords: Advocacy, Obesity, Obesity Medicine Association, Obesity Action Coalition

Graphical abstract

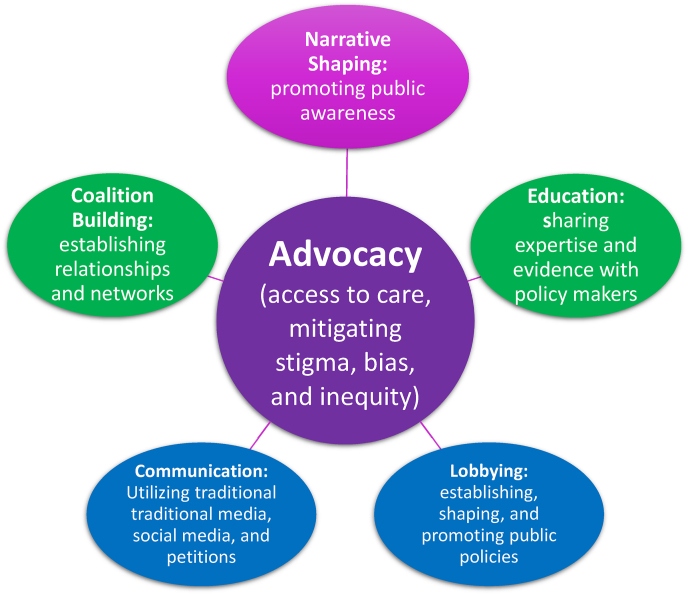

Visual Abstract: The effectiveness of advocacy is enhanced through the integration of multiple levels of advocacy. Self-advocacy is the act of seeking the understanding of an individual's rights and thus empowering individuals to speak up for themselves and make informed decisions about their treatment and management options. Individual advocacy is when the interests and rights of an individual are supported and/or represented by a clinician, friend, family, or through a group. Systems advocacy involves engaging in acts and processes intended to change societal, governmental, organizational, or agency policies, rules, and laws, as might occur when representing the interests of a disenfranchised group or class.

1. What is advocacy and why is it important to obesity management?

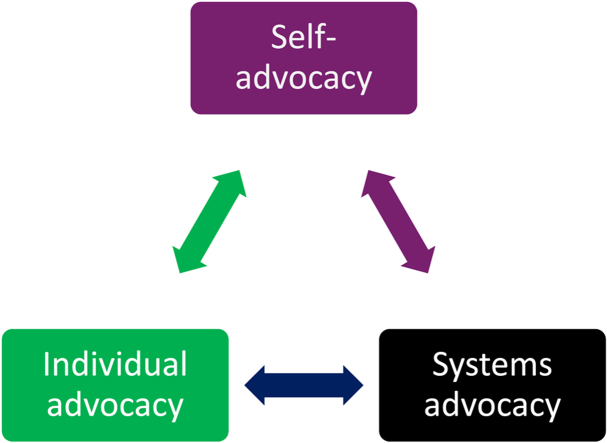

Advocacy is the utilization of educational and public policy initiatives that through relationships, networks, and advocacy tools (e.g., traditional media, social media, petitions, and direct communication with policy makers), promote public awareness and establish public policies that increase access to care, help mitigate bias, stigma, and discrimination, and improve the lives of patients living with the disease of obesity. In public policy, advocacy is viewed as both an act and a process to support or oppose an interest or proposal, which typically involves various strategies and tactics to advance policy priorities. (See Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Components of advocacy. Advocacy is the utilization of educational and public policy initiatives that through relationships, networks, and advocacy tools (e.g., traditional media, social media, petitions, and direct communication with policy makers), promote public awareness and establish public policies that improve access to care, help mitigate bias, stigma, and discrimination, and improve the lives of patients living with the disease of obesity.

An objective of advocacy is to foster collective involvement and community engagement, leading to collaborations that help empower patients living with obesity and their clinicians seek and achieve changes in policy, environment, and societal attitudes. Advocacy can also involve securing funds to enhance public awareness, promote prevention, advance clinical research, develop safe and effective evidenced-based therapeutic interventions, and facilitate patient access to comprehensive and compassionate treatment of the complex disease of obesity [1].

Overall, advocacy involves actions and processes that raise public awareness of a cause for the purpose of inspiring the implementation of solutions. From an operational perspective, health advocacy may be defined as “purposeful actions by health professionals to address determinants of health which negatively impact individuals or communities by either informing those who can enact change or by initiating, mobilizing, and organizing activities to make change happen, with or on behalf of the individuals or communities with whom health professionals work” [2].

2. What are different levels of advocacy?

Fig. 2 describes three integrative levels of advocacy: self-advocacy, individual advocacy, and systems advocacy.

Fig. 2.

Integrative levels of advocacy. The effectiveness of advocacy is enhanced through the integration of multiple levels of advocacy. Self-advocacy is the act of seeking the understanding of an individual's rights and thus empowering individuals to speak up for themselves and make informed decisions about their treatment and management options. Individual advocacy is when the interests and rights of an individual are supported and/or represented by a clinician, friend, family, or through a group. Systems advocacy involves engaging in acts and processes intended to change societal, governmental, organizational, or agency policies, rules, and laws, as might occur when representing the interests of a disenfranchised group or class.

2.1. What is self-advocacy?

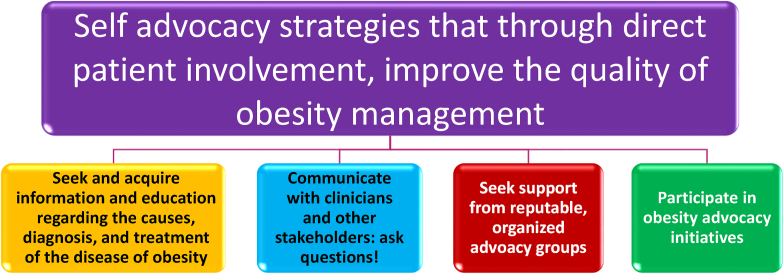

Self-advocacy is gaining and utilizing knowledge in a manner that allows the patient to actively participate in health care decision-making [3]. Patients may attain relevant knowledge via discussions with clinicians, personal research (e.g., via reputable websites, library), patient forums, and support groups. Application of this acquired knowledge can be aided via targeted motivational interviewing and learned behavior modification [4]. Clinical examples of patient self-advocacy may include asking for alternative diagnostic procedures (e.g., body composition analysis instead of body weight) [5] or not to be weighed at all. Self-advocacy may involve expressing preferences for evidenced-based nutrition and physical activity, clinical monitoring (e.g., smartphone applications), treatment options (i.e., including anti-obesity medications and surgical procedure options), and patient-centered goal setting metrics. Perhaps one of the most clinically relevant examples of self-advocacy is the willingness to ask questions (See Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Self-advocacy strategies to improve the quality of care of patients living with the disease of obesity. Self-advocacy involves direct patient involvement in improving their quality of obesity care via evidenced-based education, interactions with clinicians, and other stakeholders such as work colleagues, payers, policymakers, organizations, schools, community, and or family, and participation in obesity advocacy initiatives.

Self-advocacy begins with patient education regarding the spectrum of obesity diagnosis, treatment, and general management options. After acquiring a foundational knowledge base, the next step in self-advocacy is communicating with clinicians and other stakeholders such as work colleagues, payers, policymakers, organizations, schools, and community. Patient care may be optimized when patients seek supportive resources (e.g., through clinicians with training in obesity medicine and empathy towards patients with obesity, as well as potentially joining patient advocacy groups to help navigate the healthcare system). The intent is to empower the patient to become aware of available treatment and management options, ensuring that the individual patients have their voice heard in pursuit of patient-centered and respectful care.

Everyday self-advocacy is the ongoing acquisition of knowledge of current and future treatments for obesity and the active participation in decision-making regarding the most appropriate evidenced based treatment. Everyday self-advocacy may involve communicating with a clinician, colleague, or friend about matters of sensitivity and bias, such as noting that it is not appropriate to judge others based on body size. Everyday advocacy may include patients asking their employer human resource department representatives why obesity treatment is not covered on their health insurance plans. Everyday advocacy may include participating in an advocacy action alert and/or clicking on an Internet link to send a quick letter of encouragement to a legislator who is supportive of policy initiatives to improve access to obesity care. Individually, these may seem like small steps. However, over time, accumulation of many small self-advocacy steps can potentially lead to favorable changes that may extend beyond self.

Beyond everyday self-advocacy involving a clinician, colleague, or friend, self-advocacy also applies to family weight bias and stigma. When individuals with obesity advocate for themselves, they may be better equipped to challenge misconceptions and negative stereotypes held by family members, potentially fostering a more supportive and understanding home environment. Self-advocacy may help empower patients to communicate their needs, feelings, and experiences, potentially providing a different and personal perspective regarding the complexities of obesity. Such communication may help family members better recognize that obesity is not simply a matter of a lack of willpower but a multifactorial health issue involving genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors [6]. By being an advocate for oneself, patients with obesity may be more effective in setting boundaries and establishing respect, both important for mental and emotional well-being. Moreover, self-advocacy may help mitigate harmful behaviors and attitudes from family members, and promote a healthier, more inclusive family dynamic. Ultimately, effective self-advocacy within the family context can significantly improve the support system for individuals with obesity, enhancing their overall quality of life and encouraging healthier lifestyle changes [7].

Clinicians can help foster patient self-advocacy via supporting open communication (e.g., encouraging patients to ask questions), providing access to evidence-based educational resources, setting up an accessible office, training staff to be respectful and responsive, engaging in shared decision-making, implementing patient-centered personalized treatment plans, offering tools like evidence-based health tracking apps, and generally engaging patients in a way that furthers participation in their care plans and personal health goals. Unbiased, effective communication (verbal or nonverbal) may positively affect patient-centered outcomes [8].

2.2. What is individual advocacy?

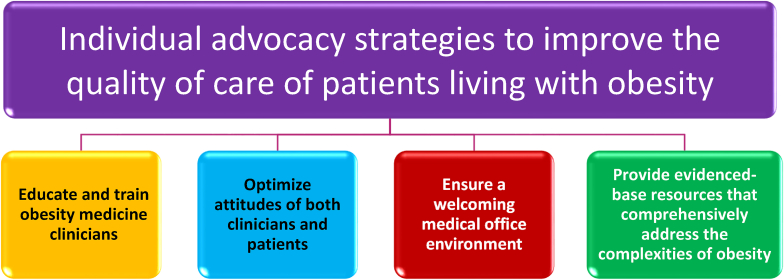

Individual advocacy is when an individual (e.g., clinician) or group furthers the interests of one or more people. An example of individual advocacy is when clinicians invest personal or staff time to petition insurance companies to provide coverage for medications, services, diagnostic tests, and referral to specialists. Examples of practical ways in which clinicians who specialize in obesity medicine demonstrate their advocacy for the individual patient with obesity is by use of people first language, avoidance of staff jokes and phrases offensive to patients with obesity, and availability of obesity-appropriate office environment and equipment [9] (See Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Individual clinician advocacy strategies to improve the quality of care of patients living with the disease of obesity. Individual advocacy involves a person or group advocating for the rights and well-being of the individual, such as resource creation to enhance education applicable to patient care, and address and prevent and/or correct misinformation, discrimination, bias, abuse, and neglect that results in substandard medical care.

Clinician support of individual advocacy may include.

-

•

Writing letters or holding meetings with human resource departments of patient employers to advocate for comprehensive coverage of obesity treatment options. Direct communication may help employers better understand obesity as a disease, the importance of treating obesity as a disease, and potentially improve insurance coverage for individual employees living with obesity.

-

•

Investing in a robust prior authorization and appeal process within the medical practice, which may help facilitate patients receive timely access to the most effective treatment of the disease of obesity. Implementing a prior authorization function in the medical practice involves a thorough understanding and navigation of insurance requirements to effectively advocate for patient needs [10].

-

•

Clinicians can leverage their expertise in obesity management by explaining the scientific basis and medical rationale for treating the disease of obesity, such as during meetings with officials representing health insurance companies, state health plans or Medicare and Medicaid programs. By providing testimony, clinicians can share their patient-encounter experiences and the impact of obesity on health and quality of life. This firsthand knowledge may help influence policy decision-makers to include comprehensive obesity management services in these health programs.

-

•

Clinicians can initiate or join public awareness campaigns to better educate the broader community about issues regarding obesity and its management. Such campaigns can help build public support for policy changes and mitigate the forces of inertia towards a direction wherein decision-makers are more likely to act.

-

•

As suggested before, clinicians also have the option to engage in direct communication with legislators through letters, emails, or meetings to reinforce the importance of comprehensive obesity care. Personalized stories and expert insights can make a compelling case for policy changes. Hearing the lived experience of patients with obesity is often more emotionally powerful and more persuasive in affecting change than citing statistics alone.

Optimal mitigation of weight stigma might best be achieved by integrating differing levels of advocacy, including self-advocacy, individual advocacy, and system advocacy (See Fig. 2). Regarding education, strategies regarding individual advocacy that may improve provider attitudes about patients with obesity include [11].

-

•

Embracing and educating on “people-first language,” with an emphasis on referring to the individual as a person, rather than labeling individuals based upon their disease. “People with obesity,” “patients with obesity,” or “persons living with obesity, are preferred over “obese patient” or especially “morbidly obese patient.” Using people-first language is a standard in chronic disease management; most diabetologists abandoned the term “diabetics” decades ago. The current preference is “patients with diabetes.” The use of people first language may be even more important for those with the disease of obesity due to the stigma associated with the diagnosis of obesity [12].

-

•

Studies suggest that patients with obesity may have reduced perception of bias and less negative attitudes about their body weight when presented with objective consensus feedback, supporting that others (e.gl, family, friends, colleagues, etc.) have favorable attitudes towards patients with obesity [13]. That said, some may find the feasibility and practicality of collecting supporting data challenging in the clinical setting.

-

•

Establish a zero-tolerance policy in the clinical setting (or workplace) for shaming comments or humor that stereotypes or degrades anyone based on body weight, physical appearance, or size.

-

•

Encourage clinicians to assess their beliefs and stereotypes about those with obesity via the online Implicit Association Test at http://www.implicit.harvard.edu).

-

•

Educate clinicians on the breadth of genetic, environmental, biological, psychological, and social contributors to obesity. Greater understanding of the pathophysiology of obesity may foster more positive attitudes about patients with obesity, and less utterances of “eat less, move more,” or “calories in equals calories out.” While the laws of thermodynamics may have applicability in discussions of physics, such oversimplified messages are rarely helpful or effective in working with the complexities of those living with obesity [6].

-

•

In patients with obesity having adiposopathic (e.g., diabetes mellitus [14], hypertension [15], or dyslipidemia [16]) fat mass (e.g., osteoarthritis, thrombosis [17], or sleep disorders [18]), or psychological complications [19], first ensure these complications are not due to causes other than increased adiposity. Then focus on optimal treatments of these complications of obesity, which often include therapeutic choices that best promote metabolic health [[19], [20], [21],21].

-

•

Rather than defeatist, derogatory, shaming, offensive, and oversimplistic statements such as “if you eat too much, you are going to get fat, and then you will have medical problems,” a more productive approach is for the clinicians to engage in a patient-centered evaluation of potential eating behavior disorders, motivations behind eating and physical activity behaviors (including underlying neurophysiology, eating disorders, environmental factors, and personal prioritization), motivational interviewing techniques, and technologies that may assist with pre-obesity/obesity management [4].

-

•

Reduce the stigma of obesity and demonstrate support for the patient living with the disease of obesity, by engaging in all levels of advocacy [22] (See section 2.0).

-

•

Educate clinicians on emotion regulation tools (e.g., meditation or deep breathing) that may help clinicians overcome negative emotions related to high cognitive load and time pressure. At minimum clinicians might benefit from being more aware of frustrations regarding “difficult” or “complex” patients which may require increased personal and staff resource investment (e.g., pre-authorizations for anti-obesity medications; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obpill.2023.100079), and how these frustrations might translate into weight bias.

-

•

Enhance provider empathy through perspective-taking exercises, which may be aided by artificial intelligence [23].

2.3. What is systems advocacy?

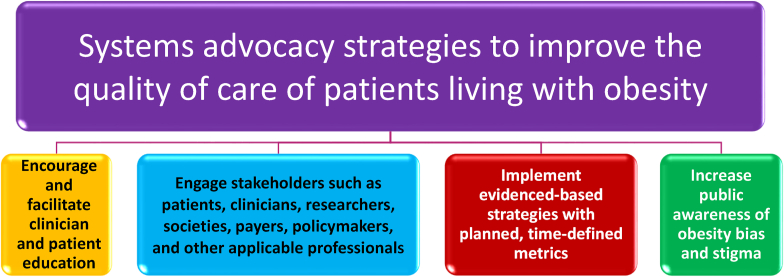

Systems advocacy is the process of changing policies, laws, and rules that affect how patients access and receive quality care. An example of systems advocacy is when clinicians and/or an advocacy organization engages with institutional, local, state, and national regulatory and administrative bodies and personnel to bring about change that promotes health and access to health care for at-risk populations (See Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

System advocacy strategies to improve the quality of care of patients living with the disease of obesity. Systems advocacy is the act of seeking to change structural challenges and promote collective well-being beyond the individual, via global educational initiatives, increased public awareness, and policy changes through engagement with applicable stakeholders, with important objectives of engaging stakeholders being the reform of policies towards the goal of increasing access to obesity care and reducing weight-based discrimination.

2.3.1. What about systems advocacy and clinician education?

Among the priorities of systems advocacy is facilitation of patient and clinician education. From a clinician standpoint, physicians with an interest in obesity management may choose to become a Diplomate of the American Board of Obesity Medicine (DABOM). The DABOM certification process has been extensively detailed previously [24]. Other clinicians such as nurse practitioners and physician associates also have the opportunity to undergo obesity management training and recognition. An illustrative example is the attainment of a Certificate of Advanced Education in Obesity Medicine [25]. An obesity medicine specialist is a clinician trained to help provide comprehensive care to patients living with obesity [1], by assessing factors that contribute to obesity, evaluating the complications of obesity, and recommending patient-centered, evidence-based approaches to obesity management.

2.3.2. What is the importance of obesity bias and stigma in systems advocacy?

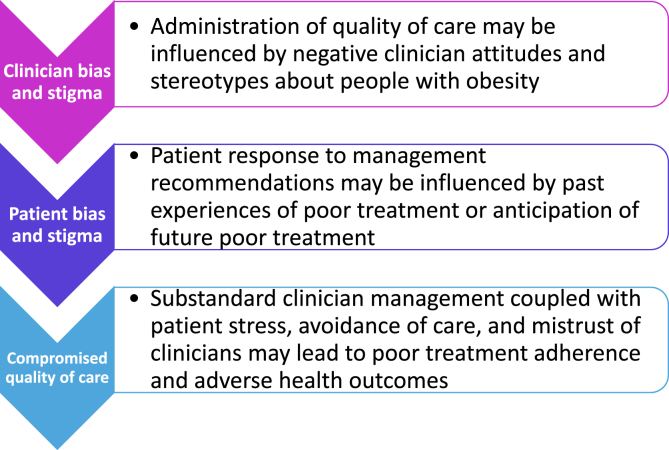

Weight bias is a root cause of many barriers to access quality care for obesity in healthcare. Many healthcare clinicians hold negative attitudes and stereotypes about people with obesity (i.e., weight bias). Such attitudes affect person-perceptions, judgment, interpersonal behavior, decision-making, and may adversely impact the quality-of-care clinicians provide and patients receive (i.e., weight stigma). Past experiences of poor treatment or anticipation of future poor treatment may contribute to patient stress, avoidance of care, mistrust of clinicians, and poor adherence to treatment recommendations among patients with obesity (See Fig. 6) [11,26].

Fig. 6.

Adverse health consequences of clinician weight bias and stigma. Many healthcare clinicians hold negative attitudes and stereotypes about people with obesity. Such attitudes affect person-perceptions, judgment, interpersonal behavior, decision-making, and may adversely impact the quality-of-care clinicians provide and patients receive. Past experiences of poor treatment or anticipation of poor treatment may contribute to patient stress, avoidance of care, mistrust of clinicians, poor adherence, and adverse health outcomes among patients with obesity.

Education and advocacy strategies that may improve the healthcare and lives of patients with obesity include improving provider attitudes about patients with obesity, altering the clinic environment or procedures to create a setting where patients with obesity feel accepted and less threatened, and empowering patients to cope with stigmatizing situations towards the goal of attaining comprehensive care [1,11].

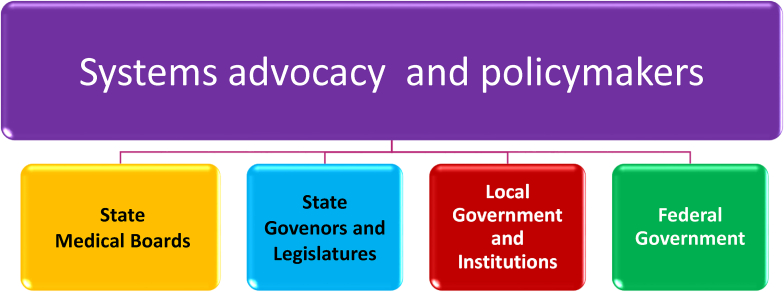

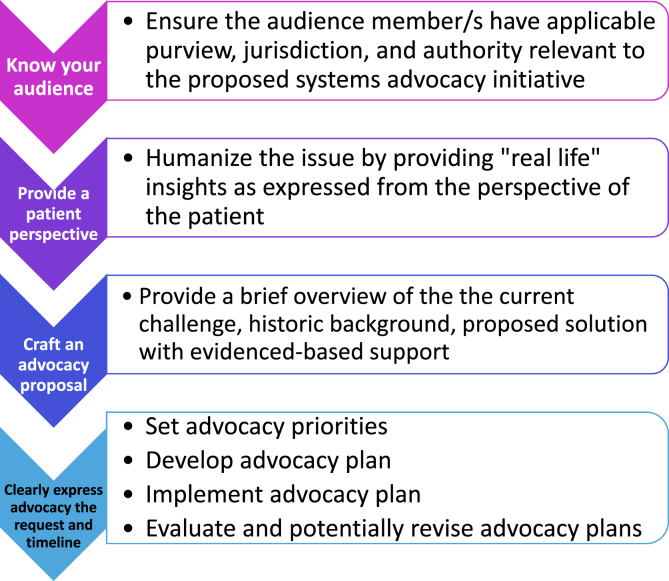

3. What are the logistics of systems advocacy strategies regarding policymakers?

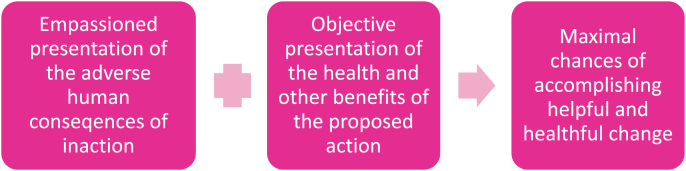

Fig. 7 describes common systems advocacy and policymakers. Fig. 8 describes how best to frame an effective advocacy argument. Tips that may mitigate potential intimidation in speaking with elected representatives and maximize the chances of implementing clinically meaningful change include.

-

•

Personal face-to-face interactive meetings with elected officials may often be more impactful than communication solely via emails and letters.

-

•

Introduce yourself (e.g., name, affiliation, location, credentials, qualification).

-

•

Summarize why the point of advocacy is important to you.

-

•

Provide a “real life” example that illustrates the unmet need (See Fig. 9).

-

•

Be prepared to provide key data relevant to your description of the problem, as well as specific citations to support your proposed solution.

-

•

Avoid basing the advocacy justification solely on emotional arguments.

-

•

Ensure your “ask” pertains to support for a specific proposed bill or policy. If no such proposed bill or policy is yet being proposed, then the ask should focus on how to move forward with such a proposal, in a manner that may achieve the greatest chance of success.

-

•

Provide contact information and express a willingness to address further questions.

-

•

Be respectful, courteous, and open to the views of others.

-

•

Be honest and forthcoming if you do not know an answer to a question.

-

•

Avoid engaging in personal attacks or displays of condescension/frustration, even if you strongly disagree with the governmental official's viewpoint, and even you feel the differing viewpoint reflects a lack of basic understanding of the issues important to you.

Fig. 7.

Illustrative examples of policymakers relevant to systems advocacy. Policymakers who have applicable purview, jurisdiction, and authority relevant to the proposed systems advocacy initiative play a crucial role in shaping and implementing actions that impact entire communities, institutions, and societal structures. Regarding the Federal Government, this may be segmented into US Congress (i.e., House & Senate) and regulatory branches of government [i.e., Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA)].

Fig. 8.

Framing an effective advocacy argument. Framing an argument that ultimately facilitates approval of a systems advocacy initiative, and that benefits the patient with obesity, often requires a strategic approach that highlights the objective and emotional consequences of inaction, integrated with evidenced-based solutions that might best shape perceptions, direct discussions, and increase the likelihood of helpful change. An advocacy argument is more effective when directed at the appropriate audience, with a clear objective and accompanied by a proposal that is understandable, applicable, and accountable. Incorporating the patient perspective helps humanize the issue. In general, advocacy work is often described as being most effective when implemented via principles similar to goal-setting applicable to obesity management [i.e., clear goals and specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound (SMART) [27]. Step-by-step processes of advocacy plans often involve the following: (a) Set priorities (i.e., identify the issue, consider solutions, and understand scientific and political context), (b) Develop advocacy plan (i.e., identify target audience, find opportunities for change, choose strategy and tools), (c) Implement advocacy plan (i.e., implement plan by raising awareness, connecting with allies, and engaging with decision makers, (d) Evaluate and revise advocacy plan (i.e., monitor the processes, implementation, and impact of the plan, with allowance for revised priorities and strategies when necessary [28].

Fig. 9.

Maximizing the chances of accomplishing helpful and healthful change. Achieving the desired systems advocacy outcomes is often facilitated by an audience understanding of the adverse human consequences of inaction coupled with the objective understanding of the benefits of the proposed action. The impact of the human perspective can often be enhanced via a description of “real life” experiences and personal anecdotes.

3.1. What is the importance of the optimal framing of an argument in systems advocacy?

While expressing an argument may increase public awareness, an equally important objective of framing an argument within the context of systems advocacy is to gain support and influence change. Those who engage in advocacy are often passionate and have a clear vision of what they believe needs to be done and when it needs to be done. Personal commitment on the part of advocates is often critical to moving initiatives forward. That said, advocates may often be more effective when they understand the audience, emphasize context, and seek to align shared values. Framing an argument that ultimately results in change most often requires highlighting both the objective and emotional consequences of inaction, integrated with corrective actions. A focus on evidenced-based solutions often has the best chance of shaping perceptions, directing discussions, and improving the quality of care to patients living with the disease of obesity (See Fig. 8).

Another often effective approach in advocacy is highlighting relatable patient stories. Hearing directly from patients adversely affected by the disease of obesity can often translate statistical abstractions into relatable humanization. By connecting with the audience through real-life experiences, patient advocates have the potential to foster empathy and understanding, increasing the likelihood of gaining support and achieving meaningful change. In short, the impact of an advocacy statement is enhanced by pairing personal stories and compelling anecdotes, integrated with evidence and data, to craft an argument that is both emotionally and intellectually compelling (See Fig. 9).

3.2. What about system advocacy and medical societies?

From a national standpoint, the American Medical Association (AMA) provides resources to assist with system advocacy. They include an AMA Federation Directory (https://federationdirectory.ama-assn.org/federations) that leads to medical society contact information such as Executive Director/Chief Executive Officer, important meeting dates, mailing addresses, email addresses, telephone numbers and website Uniform Resource Locator (URLs), that can be filtered by state, county and national medical specialty societies.

On a more local level, state medical societies may play a highly relevant role in systemic advocacy via the availability of communication connections with key stakeholders and coordinate efforts. Through collaboration with policymakers, healthcare professionals, industry, and community organizations, state medical societies often advocate for evidence-based policies and programs aimed at preventing and treating obesity. In total, by serving as educational hubs and amplifying awareness campaigns, medical societies contribute to improving the well-being of individuals affected by obesity via advocacy efforts implemented on local, state, and national levels.

3.3. What about system advocacy and state medical boards?

For system advocacy initiatives that are intended to change medical board policies, most state medical boards require a Petition for Rule-Making. Logistics regarding the specific requirements and timelines can often be found on the state board website. Completion and submission of a Petition for Rule-Making often is followed by a public comment period. It is therefore advisable to engage and elicit support from local healthcare providers, local and state medical societies, and specialty societies to submit testimony for the proposed rule change. The following link leads to an alphabetical listing of state medical boards, key contact information, and direct links to each medical board's home website: https://www.fsmb.org/contact-a-state-medical-board/

3.4. What about system advocacy and state governors?

State Governors are key targets for when engaging in system advocacy. The National Governors Association (NGA) link (https://www.nga.org/) is a forum for bipartisan policy solutions, which endeavors to confront common challenges and shape federal policy through NGA convenings, programs, task forces and bipartisan dialogue. The goal is to foster policy innovation, facilitate information-sharing, advocate bipartisan policy priorities, conduct research and data development, and provide technical assistance. From a practical perspective, the NGA provides the profile of state governors, including biographical information, links to their website and contact information for key staff on both the state and federal level.

Advocacy engagement with Governors and state health agencies often includes identifying areas to improve access and coverage of obesity care. Key focus areas for systems advocacy at the state level include state Medicaid programs, state employee health plans, and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Exchange Marketplace plans. The optimal approach (i.e., regulatory or legislative) to update policies that improve clinical care and coverage of treatments for people living with obesity is dependent on the individual states, which have differing policies, priorities, and processes.

3.5. What about systems advocacy and state legislatures?

State advocacy has the potential to improve access to obesity care and reduce weight-based discrimination. State legislatures are often a key audience for obesity treatment advocacy initiatives. Perhaps most influential would be the Chair or Ranking Member (i.e., most senior member of the majority party) of a state Healthcare Committee or state Health Insurance Committee. Such key decision makers help determine what services and treatments are covered and how the applicable budgets are allocated. Helpful Internet links include https://www.ncsl.org/, which is the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) website. This website maintains a map of the “State Legislative Session Calendar.”

3.6. What about systems advocacy and federal/public resources?

Federal systems advocacy initiatives include involvement with federal obesity programs or advocating for policy change in the United States (US) Congress (House & Senate) or with federal agencies (i.e. CMS, FDA). Examples of federal obesity programs include the public health collaboration of The High Obesity Program: A Collaboration Between Public Health and Cooperative Extension Services to Address Obesity (cdc.gov), which was launched by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity to address obesity in areas of the US with high obesity prevalence. The National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity and Environmental Research (http://nccor.org) is also a public/private organization that has a mission to accelerate progress in reducing childhood obesity for all children, with particular attention to high-risk populations and communities.

One prominent example of systems advocacy at the federal level in US Congress is the Treat and Reduce Obesity Act (TROA), which was first introduced to the 113rd Congressional session in 2013, and which represents a bipartisan (e.g., Democrats and Republicans) effort to improve access to obesity treatment services for Medicare beneficiaries. Introduced in both the US House of Representatives and the Senate, TROA aims to expand Medicare healthcare coverage of obesity care via intensive behavioral counseling through community-based programs and additional types of healthcare providers, including: dietitians, psychologists and specialty physicians, as well as remove the restriction on coverage of FDA-approved anti-obesity medications [29]. By addressing barriers to obesity care within the Medicare program, TROA seeks to enhance the payment and access coverage of evidence-based treatments for individuals living with obesity, thereby contributing to the broader effort to combat the obesity epidemic at a national level. While TROA focuses changes on Medicare coverage, it influences the obesity care access and coverage policies of commercial health insurance companies. This legislative initiative exemplifies how federal policies can be instrumental in advancing broad systemic changes to promote obesity prevention and treatment. Additional information about TROA and other legislative efforts in the US Congress relative to obesity can be found at https://www.congress.gov/.

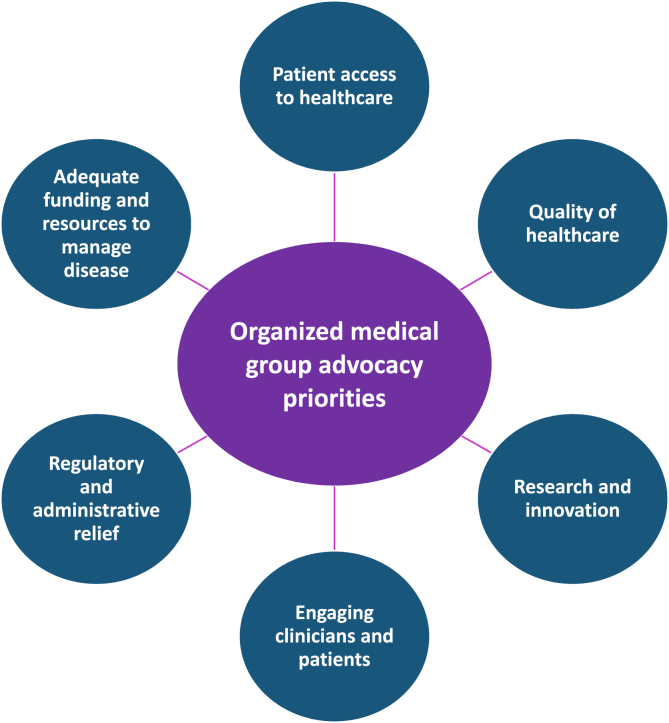

4. What are examples of organized medical groups engaged in advocacy?

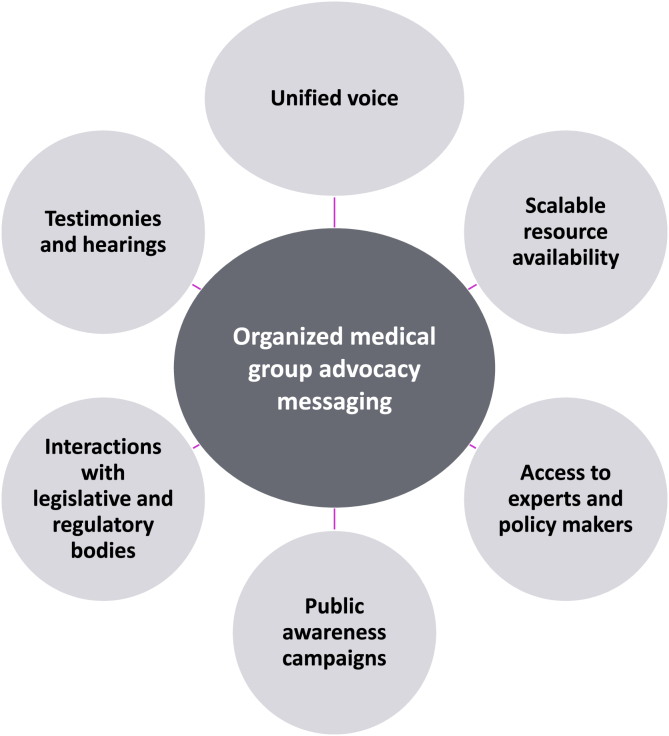

Organized medicine groups are comprised of individuals who often advocate on behalf of patient interests, as it pertains to ensuring access to care, advancing quality healthcare, fostering research and innovation, enacting regulatory relief to remove administrative burdens that impair delivery of quality healthcare, soliciting for adequate funding for medical evaluation and treatment, and engaging clinicians and patients (See Fig. 10). Messaging via a collective group may often be more impactful than messaging by the individual. Organized medical groups that represent a unified voice of many may have greater and more efficient resource allotment regarding advocacy activities, are able to launch larger-scale public awareness campaigns and may have greater access to experts and policymakers which allows for more effective interactions with legislative and regulatory bodies via testimonies and hearings (See Fig. 11).

Fig. 10.

Advocacy priorities of organized medical advocacy groups. Illustrative objectives of medical advocacy groups include ensuring adequate funding and resources to provide quality obesity care access, facilitating research and innovation, engagement of clinicians and patients (e.g., especially regarding recognition and mitigation of bias, stigma, and discrimination), and regulatory and administrative relief.

Fig. 11.

Messaging of organized advocacy medical groups. Illustrative messaging advantages of medical advocacy groups include the ability to speak with a unified voice, availability of scalable resources, access to experts and policy makers, creation of widespread public awareness campaigns, interactions with legislative and regulatory bodies, and scheduling of testimonies.

Organized medicine groups often work collaboratively with other advocacy stakeholders, with advocacy success often non-linear in nature (i.e., alternating times of success and setbacks). The chances of desired outcomes and change can often be maximized by the collective and integrated efforts of multiple organizations, individuals, and other stakeholders. Sometimes advocacy success can be facilitated by fortuitous timing, such as when a high profile issue is already a priority for governmental officials or the public. Conversely years or decades of invested foundational groundwork may become realized and achieve clinically meaningful progress only when public interest suddenly changes, or a new major stakeholder joins the cause. Below is a discussion of specific measures key stakeholders have focused upon towards matters of obesity advocacy.

4.1. What is the Obesity Action Coalition (OAC: https://www.obesityaction.org/)

The OAC is the leading national non-profit dedicated to serving people living with obesity with priorities that include awareness, support, education, and advocacy. OAC's vision is to create a society where all individuals are treated with respect and without discrimination or bias regardless of their size or weight. OAC strives for those affected by the disease of obesity to attain the right to access safe and effective treatment options. OAC has a strong and growing membership of more than 80,000 individuals, family members and providers from across the United States.

OAC advocates for comprehensive evidence-based obesity care, including nutrition counseling, intensive behavioral therapy, FDA-approved obesity medications and devices, and metabolic and bariatric surgery. Access to obesity care should not be limited by a person's size, weight or economic status.

OAC is an organization that participates and trains people to participate in all levels of advocacy (self, individual, and systems). OAC supports individual members living with obesity with education and support on their life and care journey. OAC also dedicates time and resources in systems advocacy at the state and federal levels with the goal of improving access to obesity care and eliminating weight bias and stigma. Readers can learn more about OAC's advocacy efforts and involvement by visiting: https://www.obesityaction.org/action-center/ (Table 1).

Table 1.

Five illustrative advocacy successes of the Obesity Action Coalition.

| Obesity Action Coalition (OAC) Advocacy Initiatives |

|---|

| Advocate for the passage of the federal Treat and Reduce Obesity Act (TROA) |

| Advocate for comprehensive obesity care coverage in state Medicaid programs |

| Advocate for comprehensive obesity care coverage in State Employee Health Plans and Affordable Care Act (ACA) Exchange Marketplace Plans |

| Advocate for state policy to eliminate weight-based discrimination |

| Advocate at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in support of drug and device safety, supply, and patient representation in clinical trials |

4.2. What is the Obesity Medicine Association (OMA; https://obesitymedicine.org/about/)

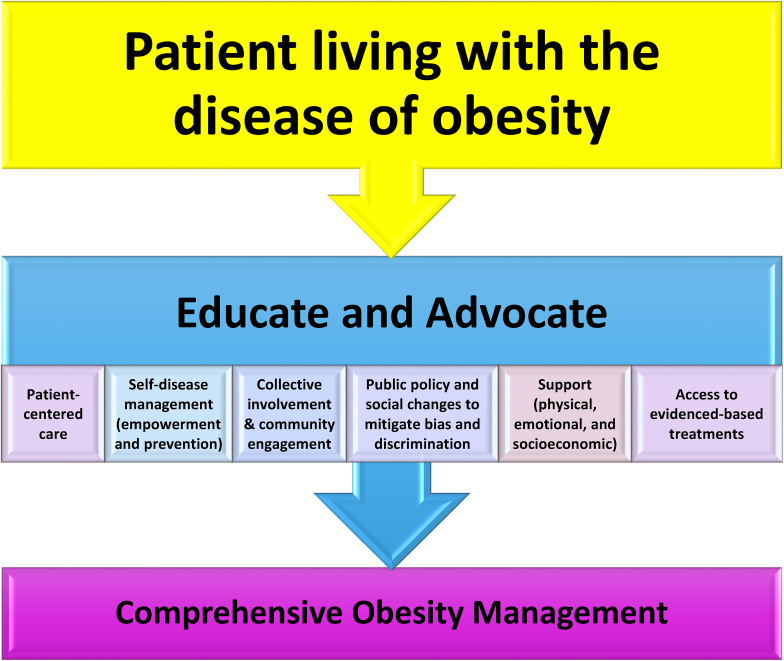

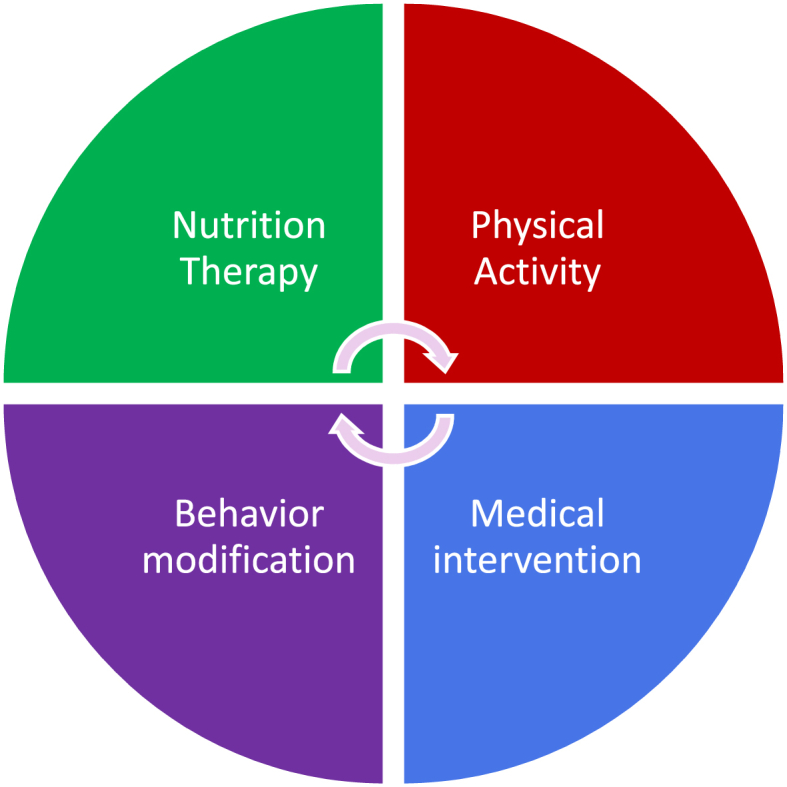

The OMA is the largest organization of physicians, nurse practitioners, physician associates, and other clinical experts (i.e., over 5000 members at time of publication) who are engaged in improving the lives of patients affected by the disease of obesity. The OMA utilizes a 4 pillars approach (https://obesitymedicine.org/about/four-pillars/which includes nutrition therapy, physical activity, behavioral modification, and medical interventions (e.g., medications, bariatric procedures, and complication management) (See Fig. 12). Two essential mechanisms utilized by the OMA to achieve comprehensive obesity management include education and advocacy (See Fig. 13). Table 2 lists some of the historic advocacy initiatives achieved by the OMA.

Fig. 12.

Four Pillars of the Obesity Medicine Association. Optimal management of the multifactorial disease of obesity requires an integrated multifactorial approach regarding (a) nutrition therapy (e.g., avoidance of ultraprocessed, caloric dense foods); (b) physical activity (e.g., routine dynamic and resistance training), behavior modification (e.g., willingness to apply techniques that facilitate healthful change), and medical intervention (e.g., medications, bariatric procedures, and complication management).

Fig. 13.

Targeted outcomes of education and advocacy initiatives. Desired outcomes of education and advocacy initiatives regarding patients living with the disease of obesity include facilitation of patient-centered care where prevention and self-disease management empowerment is integrated with collective involvement of clinicians, family, friends, and community. Concurrent to patient-centered care are efforts to facilitate public policy and social changes to mitigate bias and discrimination, provide physical, emotional, and socioeconomic support, and ensure access to evidenced-based treatment. Collectively, such initiatives all help achieve comprehensive obesity management [1].

Table 2.

Five illustrative advocacy successes of the Obesity Medicine Association [29].

| Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) Advocacy Initiatives |

|---|

| Advocate for comprehensive obesity care monetary and supply coverage of anti-obesity medications, intensive behavior therapy, and surgery, as well as Medicaid coverage at the state level |

| Advocate for evidence-based obesity care with state medical boards |

| Advocate for the passage of the Treat and Reduce Obesity Act (TROA) at the federal level |

| Established strategic partnerships including OAC, OCAN, and AMA to help reduce bias and stigma surrounding patients with obesity and management of obesity |

| Educating and empowering OMA members on matters of advocacy |

OAC: Obesity Action Coalition.

OCAN: Obesity Care Advocacy Network.

AMA: American Medical Association.

4.3. What is the American medical association (AMA; https://www.ama-assn.org/about)

Founded in 1847, the AMA is the largest national association that convenes 190+ state and specialty medical societies and other critical stakeholders. The AMA carries out its mission towards promoting the art and science of medicine and the betterment of public health via representing physician as a unified voice in courts and legislative bodies, removing obstacles that interfere with patient care, helping to prevent chronic disease, confronting public health crises, addressing challenges in health care, and helping train future leaders. The AMA has a system of governance and policy making that includes a board of trustees, House of Delegates, executive vice president, councils and committees, special sections, and AMA senior leadership and staff.

Table 3 lists some of the historic advocacy initiatives achieved by the AMA. In general, the AMA leverages existing channels within AMA to advance the following priorities.

-

•

Promote awareness amongst practicing physicians and trainees that obesity is a treatable chronic disease along with evidence-based treatment options

-

•

Engage in advocacy efforts at the state and federal level to impact the disease of obesity

-

•

Address health disparities, stigma, and bias affecting people with obesity

-

•

Address the lack of insurance coverage for evidence-based treatments including intensive lifestyle intervention, anti-obesity pharmacotherapy, and bariatric and metabolic surgery.

-

•

Acknowledge the increasing obesity rates in children, adolescents, and adults

-

•

Identify drivers of obesity include lack of healthful food choices, over-exposure to obesogenic foods, and food marketing practices

-

•

Specifically, regarding advocacy, the AMA “will conduct a landscape assessment that includes national level obesity prevention and treatment initiatives, and medical education at all levels of training to identify gaps and opportunities where AMA could demonstrate increased impact”

Table 3.

Five illustrative advocacy successes of the American Medical Association.

| Advocacy Initiative | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 2022: AMA advocated to finance a comprehensive national program for the study, prevention, and treatment of obesity. |

|

American Medical Association. Addressing Adult and Pediatric Obesity D-440.954. Interim Meeting; 2022. Modified: Sub. Res. 111, A-14; Modified: Res. 818, I-22; Reaffirmed: A-13; Appended: Res. 201, A-18; BOT Action in response to referred for decision: Res. 415, A-22. https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/Addressing/20Obesity/20D-440.954?uri=/2FAMADoc/2Fdirectives.xml-0-1498.xmlhttps://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder |

| 2018: AMA advocated to identify states that restricted obesity treatments |

|

American Medical Association House of Delegates. Resolution: 224 (A-23). Advocacy Against Obesity-Related Bias by Insurance Providers. Introduced by: American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. Referred to: Reference Committee B; 2023. =https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail//22scope/20of/20practice/22?uri=/2FAMADoc/2FHOD.xml-H-440.801.xmlhttps://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder |

| 2017: AMA advocated for use of person-first language | “Our AMA: (1) encourages the use of person-first language (patients with obesity, patients affected by obesity) in all discussions, resolutions and reports regarding obesity; (2) encourages the use of preferred terms in discussions, resolutions and reports regarding patients affected by obesity including weight and unhealthy weight, and discourage the use of stigmatizing terms including obese, morbidly obese, and fat; and (3) will educate health care providers on the importance of person-first language for treating patients with obesity; equipping their health care facilities with proper sized furniture, medical equipment and gowns for patients with obesity; and having patients weighed respectfully.” | American Medical Association. Person-First Language for Obesity H-440.821. Annual Meeting; 2017. Modified: Speakers Rep., I-17. https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/Person-First/20Language/20for/20Obesity/20H-440.821?uri=/2FAMADoc/2FHOD.xml-H-440.821.xml |

| 2014 (last year modified 2022): AMA advocated for patient access to and physician payment for the full continuum of evidence-based obesity treatment modalities |

|

American Medical Association House of Delegates Resolution: 224 (A-23). https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/a23-224.pdf https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/obesity?uri=%2FAMADoc%2Fdirectives.xml-0-1498.xmlhttps://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder |

| 2013 (modified 2023): AMA advocated the recognition of obesity as a disease | “Our American Medical Association recognizes obesity as a disease state with multiple pathophysiological aspects requiring a range of interventions to advance obesity treatment and prevention.” | Recognition of Obesity as a Disease H-440.842. https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/H-440.842?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-3858.xmlhttps://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder |

5. What are examples of existing advocacy coalition efforts?

5.1. Obesity Care Continuum (OCC) https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/obesity-care-continuum-occ-commends-food-and-drug-administration-fda-for-their-continued-proactive-support-and-approval-of-new-obesity-treatments-162812276.html

In 2011, The Obesity Society (TOS), the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS), Obesity Action Coalition (OAC), and the Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) joined forces with the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) in founding the Obesity Care Continuum (OCC), to form an ad-hoc coalition. With a combined membership of over 150,000 healthcare professionals, researchers, educators, and patient advocates, the OCC is dedicated to promoting access to, and coverage of the continuum of care surrounding the treatment of overweight and obesity.

5.2. Obesity Care Advocacy Network (OCAN) https://obesitycareadvocacynetwork.com/

The OCAN was organized in 2015 with the intent to support advocacy efforts by the OCC and change the perception of obesity and its management in the U.S. As stated on the website: “OCAN works to increase access to evidence-based obesity treatments by uniting key stakeholders and the broader obesity community around significant education, policy and legislative efforts.” The OCAN includes over 30 organizations with the mission to unite and align key obesity stakeholders regarding education, policy, and legislative efforts to elevate obesity on the national agenda.

5.3. STOP Obesity Alliance (https://stop.publichealth.gwu.edu/)

The STOP Obesity Alliance | Milken Institute School of Public Health | The George Washington University is composed of a diverse group of business, consumer, government, advocacy, and health organizations dedicated to reversing the obesity epidemic in the United States via research, policy recommendations, and hands-on tools for providers, advocacy groups, policymakers, and consumers.

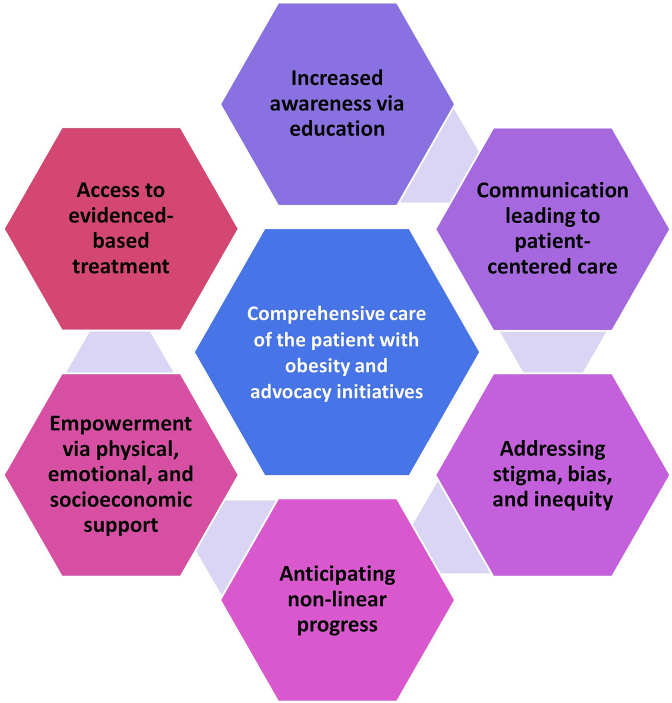

6. What are challenges of patient advocacy?

Regarding patients, obesity management success is maximized when inclusive of education, communication, empowerment, evidenced-based interventions, while addressing stigma, bias, and inequity. Integral to advocacy is the affirmation of the lived experiences of the patient with obesity, which directly impacts the construct of personalized and effective care. Additionally, even with the best of obesity management, progress often has times of success alternating with times of stagnation and perhaps even adverse reversal. It is the anticipation of non-linear patient care success that supports having contingency plans as an important part of any treatment paradigm (See Fig. 14). The same might be said of advocacy initiatives, which often incorporate education, communication, empowerment, evidenced-based interventions, while also addressing stigma, bias, and inequity. Just as with patients, ultimate success may depend on contingency plans, or at least a rational expectation of the speed and nature of success.

Fig. 14.

Analogous challenges exist regarding comprehensive care for the individual patient with obesity and advocacy efforts to help achieve comprehensive care for all patients with obesity. To maximize the potential for success, both require education, communication, empowerment, evidenced-based interventions, and addressing stigma, bias, and inequity. Even when success is achieved, it should be the expectation that the progress and success of both obesity management and advocacy initiatives will have times of success that alternate with times of challenges.

It is often said that: “A goal without a plan is just a wish.” This is why goal-setting criteria and accountability often have advantages in facilitating success. One common approach is illustrated by the components of SMART (See Fig 8), which includes goals that are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound [27]. Just as with patients, advocacy initiatives benefit from the establishment of apriori objectives with defined criteria that help ensure successful and meaningful outcomes if implemented. This is especially so given that the same target audience for advocacy initiatives are often revisited. If a target audience of an advocacy initiative agrees to invest in the initiative, and the initiative ultimately fails because the project was not specific, not measured, not achievable, irrelevant, and without time constraints, then these target audiences may be less likely to agree to invest resources in future advocacy initiatives (See Fig. 8).

7. What is a patient perspective regarding advocacy? (Written by Elizabeth Paul, National Board of Directors, Obesity Action Coalition)

Patients can participate in advocacy in a variety of levels in ways that they are comfortable. Advocacy can take varied forms; thus, patients have options when, how and if they share their story living with obesity. Ultimately, patients are experts in their own experience and it is their stories that hold important context for finding success in advocacy.

For patients, participation in self-advocacy might look like standing up for yourself when someone expresses bias and stigma or advocating for an appropriate standard of care from a physician. Participation in individual advocacy might be participation in a patient panel as a part of educating clinicians on the lived experience of obesity and associated bias and stigma. Participation in systems advocacy might involve sharing your story with state or federal legislators to help further policy changes regarding access to care for comprehensive obesity treatments. These are just a few examples of the ways patients can be advocates. No matter the context of the advocacy, every time patients share their experiences, the represents an opportunity to reduce stigma and bias and further advocacy efforts.

Nevertheless, patients must often face their own experiences of bias, stigma, and trauma to get to a place of empowerment, which in turn, may better equip patients to serve as advocates. Involvement in organizations like the Obesity Action Coalition can help to reframe patient's experience, confront their own internalized bias, and help them learn to share their story.

Having the patient with obesity share experiences can be empowering for advocacy, highlighting the impact of personal stories, while also exposing the patient's vulnerability, which may lead to a better appreciation to the lives of other individuals with obesity. Patients must have access to emotional support to be patient advocates because of the real risks that still come from speaking up against bias and stigma. Patients who choose this course often do so because they wish to see a world where others are treated better than they were, where people living with obesity have access to scientifically based comprehensive and compassionate care, and where weight bias and stigma are eliminated.

8. Conclusion

Advocacy represents steps and actions taken towards the objective to foster collective involvement and community engagement, leading to collaborations that help empower patients living with obesity and their clinicians to seek and achieve changes in policy, environment, and societal attitudes. Advocacy is a multilevel process that integrates self-advocacy, individual advocacy, and systems advocacy. Takeaway priorities in ensuring optimal effectiveness of advocacy include.

-

•

Acknowledging the lack of adequate access to care for many patients living with the disease of obesity

-

•

Recognizing the adverse health consequences of weight bias and stigma

-

•

Understanding the perspective and relevance of audience stakeholders and policymakers

-

•

Communicating and framing effective advocacy arguments accompanied by evidence-based policy solutions

Transparency and group composition [30]

The authors reflect a multidisciplinary and balanced group of experts in obesity science, patient evaluation, and clinical treatment.

Author contributions

HEB created an initial narrative outline and drafted the initial text based upon an organizational video/teleconference with many of the authors. All authors engaged in review, editing and approval of the final draft.

Managing disclosures and dualities of interest

Authors of this joint clinical perspective received no payment for their writing, editing, and publishing work. While Editors of journals who are listed as authors received payment for their roles as Editors, they did not receive payment for their participation as authors.

Individual disclosures

CFB: Speaker Eli Lilly; personal investments in Eli Lilly and NovoNordisk.

TZ: No disclosures.

EP: Advisor to Pfizer and Boehringer Ingelheim.

LG: No disclosures.

CV: reports being an advisor for Eli Lilly.

HEB's research site institution has received research grants from 89Bio, Allergan, Alon Medtech/Epitomee, Aligos, Altimmune, Amgen, Anji Pharma, Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Bionime, Boehringer Ingelheim, Carmot, Chorus/Bioage, Eli Lilly, Esperion, Evidera, Fractyl, GlaxoSmithKline, HighTide, Home Access, Horizon, Ionis, Kallyope, LG-Chem, Madrigal, Merck, Mineralys, New Amsterdam, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Pfizer, Regeneron, Satsuma, Selecta, Shionogi, TIMI, Veru, Viking, and Vivus. HEB has served as a consultant/advisor for 89Bio, Altimmune, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, HighTide, Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

Funding

Preparation of this manuscript received no funding.

Evidence

The content of this manuscript is supported by citations, which are listed in the References section.

Ethics review

This submission did not involve experimentation of human test subjects or volunteers. Authors who concomitantly served as journal Editors for Obesity Pillars or Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) Board or Trustees were not involved in editorial decisions or the peer review process. Journal editorial decisions and peer review management was delegated to non-author OMA members or non-author journal Editors.

Peer review

This joint clinical perspective underwent peer review according to the policies of the participating organizations.

Declaration of artificial intelligence (AI) and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

AI was used for suggestions regarding topic headings and categorizations. Artificial intelligence was not used in the writing of the text nor creation of its figures. The authors accept full responsibility for the final content of this submission.

Conclusions and recommendations

This joint clinical perspective is intended to be an educational tool that helps better facilitate and improve the clinical care and management of patients with obesity. This joint clinical perspective should not be interpreted as “rules” and/or directives regarding the medical care of an individual patient. The decision regarding the optimal care of the patient with pre-obesity and obesity is best reliant upon a patient-centered approach, managed by the clinician tasked with directing an individual treatment plan that is in the best interest of the individual patient.

Updating

This joint clinical perspective may require future updates. The timing of such an update will be determined by the respective societies authoring this document.

Disclaimer and limitations

This joint clinical perspective was developed to assist health care professionals in providing care for patients with pre-obesity and obesity based upon the best available evidence. In areas regarding inconclusive or insufficient scientific evidence, the authors used their professional judgment. This joint clinical perspective is intended to represent the state of obesity medicine at the time of publication. Thus, this joint clinical perspective is not a substitute for maintaining awareness of emerging new science. Finally, decisions by clinicians and healthcare professionals to apply the principles in this joint clinical perspective are best made by considering local resources, individual patient circumstances, patient agreement, and knowledge of federal, state, and local laws and guidance.

Contributor Information

Carolynn Francavilla Brown, Email: doctorfrancavilla@gmail.com.

Tracy Zvenyach, Email: tzvenyach@obesityaction.org.

Elizabeth Paul, Email: morgenstar20@hotmail.com.

Leslie Golden, Email: lgolden@weightingoldwellness.com.

Catherine Varney, Email: cwv9v@uvahealth.org.

Harold Edward Bays, Email: hbaysmd@outlook.com.

References

- 1.Fitch A., Alexander L., Brown C.F., Bays H.E. Comprehensive care for patients with obesity: an obesity medicine association position statement. Obesity Pillars. 2023;7 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oandasan I.F. Health advocacy: bringing clarity to educators through the voices of physician health advocates. Acad Med. 2005;80:S38–S41. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510001-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brashers D.E., Haas S.M., Neidig J.L. The patient self-advocacy scale: measuring patient involvement in health care decision-making interactions. Health Commun. 1999;11:97–121. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1102_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freshwater M., Christensen S., Oshman L., Bays H.E. Behavior, motivational interviewing, eating disorders, and obesity management technologies: an Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) Clinical Practice Statement (CPS) 2022. Obes Pillars. 2022;2 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2022.100014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burridge K., Christensen S.M., Golden A., Ingersoll A.B., Tondt J., Bays H.E. Obesity history, physical exam, laboratory, body composition, and energy expenditure: an Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) Clinical Practice Statement (CPS) 2022. Obes Pillars. 2022;1 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2021.100007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bays H.E., Golden A., Tondt J. Thirty obesity myths, misunderstandings, and/or oversimplifications: an obesity medicine association (OMA) clinical practice statement (CPS) 2022. Obes Pillars. 2022;3 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2022.100034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanagasingam D., Hurd L., Norman M. Integrating person-centred care and social justice: a model for practice with larger-bodied patients. Med Humanit. 2023;49:436–446. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2021-012351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharkiya S.H. Quality communication can improve patient-centred health outcomes among older patients: a rapid review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23:886. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09869-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitch A.K., Bays H.E. Obesity definition, diagnosis, bias, standard operating procedures (SOPs), and telehealth: an Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) Clinical Practice Statement (CPS) 2022. Obes Pillars. 2022;1 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2021.100004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bays H.E., Francavilla Brown C., Fitch A. Universal prior authorization template for glucagon like peptide-1 based anti-obesity medications: an obesity medicine association proposal. Obesity Pillars. 2023;8 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phelan S.M., Burgess D.J., Yeazel M.W., Hellerstedt W.L., Griffin J.M., van Ryn M. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2015;16:319–326. doi: 10.1111/obr.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kyle T.K., Puhl R.M. Putting people first in obesity. Obesity. 2014;22:1211. doi: 10.1002/oby.20727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puhl R.M., Schwartz M.B., Brownell K.D. Impact of perceived consensus on stereotypes about obese people: a new approach for reducing bias. Health Psychol. 2005;24:517–525. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.5.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bays H.E., Bindlish S., Clayton T.L. Obesity, diabetes mellitus, and cardiometabolic risk: an obesity medicine association (OMA) clinical practice statement (CPS) 2023. Obes Pillars. 2023;5 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2023.100056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clayton T.L., Fitch A., Bays H.E. Obesity and hypertension: obesity medicine association (OMA) clinical practice statement (CPS) 2023. Obesity Pillars. 2023;8 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2023.100083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bays H.E., Kirkpatrick C., Maki K.C., Toth P.P., Morgan R.T., Tondt J., et al. Obesity, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease: a joint expert review from the obesity medicine association and the national lipid association 2024. Obes Pillars. 2024;10 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2024.100108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bindlish S., Ng J., Ghusn W., Fitch A., Bays H.E. Obesity, thrombosis, venous disease, lymphatic disease, and lipedema: an obesity medicine association (OMA) clinical practice statement (CPS) 2023. Obesity Pillars. 2023;8 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2023.100092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pennings N., Golden L., Yashi K., Tondt J., Bays H.E. Sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and other obesity-related sleep disorders: an Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) Clinical Practice Statement (CPS) 2022. Obes Pillars. 2022;4 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2022.100043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christensen S.M., Varney C., Gupta V., Wenz L., Bays H.E. Stress, psychiatric disease, and obesity: an obesity medicine association (OMA) clinical practice statement (CPS) 2022. Obes Pillars. 2022;4 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2022.100041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tondt J., Bays H.E. Concomitant medications, functional foods, and supplements: an obesity medicine association (OMA) clinical practice statement (CPS) 2022. Obes Pillars. 2022;2 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2022.100017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghusn W., Bouchard C., Frye M.A., Acosta A. Weight-centric treatment of depression and chronic pain. Obesity Pillars. 2022;3 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2022.100025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubino F., Puhl R.M., Cummings D.E., Eckel R.H., Ryan D.H., Mechanick J.I., et al. Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nat Med. 2020;26:485–497. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0803-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bays H.E., Fitch A., Cuda S., Gonsahn-Bollie S., Rickey E., Hablutzel J., et al. Artificial intelligence and obesity management: an obesity medicine association (OMA) clinical practice statement (CPS) 2023. Obes Pillars. 2023;6 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2023.100065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fitch A., Horn D.B., Still C.D., Alexander L.C., Christensen S., Pennings N., et al. Obesity medicine as a subspecialty and United States certification - a review. Obes Pillars. 2023;6 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2023.100062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christensen S. Obesity Medicine Association (OMA): nurse practitioner & physician assistants update. Obesity Pillars. 2022;1 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puhl R.M., Lessard L.M., Himmelstein M.S., Foster G.D. The roles of experienced and internalized weight stigma in healthcare experiences: perspectives of adults engaged in weight management across six countries. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization . Advocacy step 2: setting goals and objectives. 2008. Cancer Control: knowledge into action: WHO guide for effective programmes: module 6: policy and advocacy.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK195424/ Geneva. Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuehne F., Kalkman L., Joshi S., Tun W., Azeem N., Buowari D.Y., et al. Healthcare provider advocacy for primary health care strengthening: a call for action. J Prim Care Community Health. 2022;13 doi: 10.1177/21501319221078379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Francavilla C., Andrick R. Obesity medicine association (OMA): advocacy update. Obesity Pillars. 2022;1 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham R., Mancher M., Miller Wolman D., Greenfield S., Steinberg E. National Academies Press; Washington (DC): 2011. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]