Abstract

An efficient metal-free, triflic acid-promoted intramolecular Friedel–Crafts-type carbocyclization of alkenylated biphenyl derivatives is discussed. This method provides an elegant route for the construction of 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes of biological significance in good to excellent yields. The carbocyclization reaction is likely to proceeds via activation of terminal C C bond of alkenylated biphenyl derivatives followed by subsequent aromatic electrophilic substitution to give desired carbocyclic products. Single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis of compound 10d revealed that the crystals are packed in AB-AB layer packing, where the molecules are aligned in anti-parallel fashion. Notably, all of the synthesized 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes exhibited blue to greenish yellow fluorescence with λmax = 418–481 nm range. The stokes shift, quantum yield and optical band gap of tricyclic products were computed using their absorption and emission spectra. A significant positive solvatochromic effect was observed for 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene derivative 10l, which is a characteristic of ICT interactions.

Keywords: Friedel–Crafts carbocyclization; Alkenylated biphenyl derivatives; Triflic-acid; 9,10-Dihydrophenanthrenes; Electrophilic substitution; Photophysical properties

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Synthesis of fluorescent 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes in good yields.

-

•

The synthesized compounds were characterized by their spectroscopic analysis.

-

•

The photophysical behaviour of the synthesized compounds was studied by using UV–vis and fluorescence spectroscopy.

1. Introduction

The frameworks of 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene compounds are widely found in biologically active natural products and synthetic compounds with interesting biological activities [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5]]. Some representative examples of bioactive naturally occurring compounds are shown in Fig. 1. 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene derivative 1 isolated from Dendrobium officinale exhibits cytotoxic activities against HI-60 and THP-1 cancer cell lines (Fig. 1) [6]. Moreover, phenanthrenes 2–8 isolated from Juncus compressus plant showed remarkable antiproliferative activity while derivative 6 exhibits antiviral activity against the herpes simplex 2 virus (HSV-2) [7]. Additionally, 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene compounds with useful optical properties have been explored for the fabrication of light-emitting devices [8]. Therefore, there has been a great interest for the development of new synthetic methodologies for these class of molecules. Various intermolecular [[9], [10], [11]] and intramolecular protocols [[12], [13], [14]] including transition metal-catalyzed C–H functionalization reactions [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19]] have been well explored to prepare various 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene scaffolds. However, these methods have noticeable drawbacks such as limited availability of precursors, requirement of harsh operating conditions, lower yields, lesser substrates scope, multistep synthesis, and lack of regioselectivity.

Fig. 1.

Representative examples of naturally occurring 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene compounds 1–8.

Friedel–Crafts reaction is one of the fundamental methods for the synthesis of carbocyclic and heterocyclic compounds via C–C bond formation by aromatic electrophilic substitution [[20], [21], [22], [23]]. Most of these reactions are mediated by Brønsted and Lewis acids [24,25]. In this context, superacid has been identified as an attractive reaction medium to generate reactive super electrophilic species for the construction of cyclic systems following the Olah's work [26]. Noticeable work from the research group of Klumpp involves synthesis of polycyclic aromatic compounds via triflic acid-promoted superelectrophilic cyclization of olefinic substrates [27,28]. Further Ichikawa and co-workers accomplished acid-promoted domino Friedel–Crafts-Type cyclization of 1,1-difluoroalk-1-enes and 1,1-difluoroalka-1,3-dienes, providing direct access to angular polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [29,30]. Meanwhile, Satyanarayana's group prepared 3-substituted indan-1-one derivatives following TfOH-mediated intermolecular Friedel–Crafts alkylation and intramolecular acylation of ethyl cinnamates [31,32]. Later, Lee employed catalytic amount of Brønsted acid such as TfOH for the cyclization of diaryl- and alkyl aryl-1,3-dienes to yield corresponding indene derivatives.[33]. Very recently, Oestreich and co-workers performed intramolecular Friedel–Crafts-type cyclization of aryl-tethered 1,1-difluoroalkenes via sequential electrophilic silylation, cyclization and hydrodefluorination strategy [34]. With this precedent in mind and aiming for a metal-free protocol for 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes, we envisioned a super-acid promoted intramolecular Friedel–Crafts-type carbocyclization of alkenylated biphenyl derivatives under mild reaction conditions. The present method is quite simple, time-efficient, exhibits excellent functional group compatibility, free from expensive metal-catalysts and sensitive reaction conditions.

2. Result and discussion

The precursors alkenylated biphenyl derivatives 9 were prepared through the ring transformation of 2H-pyran-2-ones with 5-hexen-2-one as carbanion source under basic conditions [35]. In order to find the optimized condition for the intramolecular Friedel–Crafts-type carbocyclization, we chose electron-rich 2-allyl-4′-methoxy-3-methyl-5-(piperidin-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile 9d as the model substrate. Various Brønsted and Lewis acids were screened and the results are summarized in Table 1. To begin with, the Friedel–Crafts cyclization of alkenylated biphenyl derivative 9d was performed with trifluoroacetic acid as promoting agent and dichloromethane as the reaction medium at room temperature (Table 1, entry 2). However, no formation of cyclized product 10d was observed. Further we were pleased to find that the reaction with superacid (triflic acid) in DCM at room temperature successfully afforded the desired substituted 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene 10d albeit in lower yield (38 %) along with the recovery of unreacted starting material (Table 1, entry 2). Interestingly, the yield of carbocyclic product 10d improved significantly when the acid loading was increased to 5 equivalences (Table 1, entries 2–5). The isolated product was characterized as the tricyclic compound 10d using NMR spectroscopy. Reaction also worked well with concentrated H2SO4 and the desired product 10d was isolated in 72 % yield (Table 1, entry 6). Subsequent studies revealed that other acids such as HNO3, HCl and HClO4 were less effective for the formation of carbocyclic product 10d compared to TfOH (Table 1, entries 7–9) while reaction with camphor sulfonic acid and AcOH lead to the complete recovery of the precursor 9d (Table 1, entries 10–11). On the other hand, other Lewis acids such as BF3·Et2O and FeCl3 did not activate the olefinic double bond efficiently and no product formation was observed (Table 1, entries 12–13).

Table 1.

Screening of Acids and Solvents for the Friedel–Crafts-type carbocyclization reaction.

| Entry | Acids (equiv) | Solvent | Time (h) | Yield 10d (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TFA (5) | DCM | 24 | – |

| 2 | TfOH (2) | DCM | 5 | 38 |

| 3 | TfOH (3) | DCM | 5 | 72 |

| 4 | TfOH (4) | DCM | 2 | 81 |

| 5 | TfOH (5) | DCM | 1 | 92 |

| 6 | H2SO4 (5) | DCM | 10 | 72 |

| 7 | HNO3 (5) | DCM | 24 | – |

| 8 | HCl (5) | DCM | 24 | 65 |

| 9 | HClO4 (5) | DCM | 24 | 45 |

| 10 | CSA (5) | DCM | 24 | – |

| 11 | AcOH (5) | DCM | 24 | – |

| 12 | BF3·Et2O (5) | DCM | 24 | – |

| 13 | FeCl3 (5) | DCM | 24 | – |

| 15 | TfOH (5) | Benzene | 24 | – |

| 16 | TfOH (5) | THF | 24 | – |

| 17 | TfOH (5) | MeOH | 24 | – |

| 18 | TfOH (5) | MeCN | 24 | – |

| 19 | TfOH (5) | DMSO | 24 | – |

In addition, various polar and non-polar solvents were used for the carbocyclization of 9d using TfOH as the promoter (Table 1, entries 1, 15–19). The carbocyclization reaction proceeded well in polar and aprotic solvent dichloromethane (Table 1, entry 5). The screening of series of solvents showed that benzene, THF, MeCN and DMSO were found unsuitable for the carbocyclization reaction (Table 1, entry 5 vs 15–19). Finally, the optimized reaction condition for the TfOH-promoted Friedel–Crafts-type carbocyclization of alkenylated biphenyl derivative 9d to furnish dihydrophenanthrene derivative 10d were identified as follows: 5 equiv. TfOH as the acid promoter and DCM as the solvent media at room temperature.

Having established the optimal reaction conditions, we next evaluated the synthetic scope of this intramolecular Friedel–Crafts-type cyclization reaction. As shown in Table 2, a variety of substrates 9 incorporated with electron-rich or electron-deficient aryl groups at the ortho position smoothly reacted to furnish corresponding 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene derivatives 10a–o in 60–92 % yields. Interestingly, reaction was compatible with simple phenyl-substituted substrates 9a-c and the desired products 10a-c were obtained in good yields. It is worthwhile to mention that the carbocyclic products 10d–g were obtained in excellent yields with substrates 9 bearing electron-donating substituents like OMe, Me groups in the phenyl ring. On the other hand, carbocyclization of substrates 9i–n having electron-withdrawing groups in the phenyl ring were found to be slow and the anticipated products 10i–n were isolated in relatively lower yields. Thus, it was concluded that the reaction rate depends on the nature of the aromatic ring, particularly electron-rich aryl groups yielded higher yields in shorter reaction time as compared to its counterpart. Halogens such as F, Cl and Br were well tolerated, which could be utilized for further synthetic manipulations.

Table 2.

Synthesis of 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes 10 via TfOH-promoted Friedel–Crafts-type carbocyclization of alkenylated biphenyl derivatives 9.a

All the reactions were performed using 9 (0.4 mmol) and triflic acid (5.0 equiv) in DCM (3.0 mL) at room temperature.

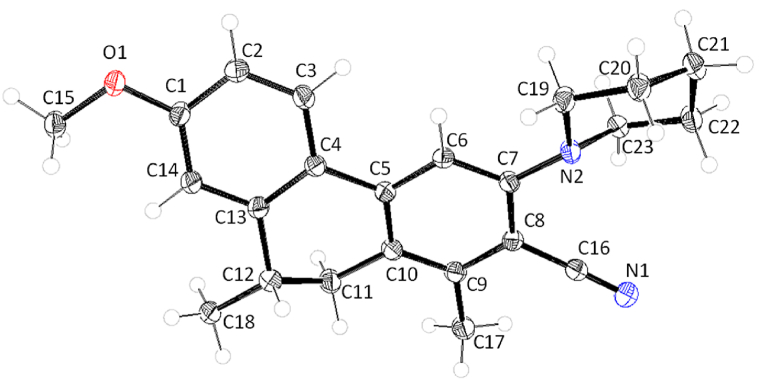

The structure of 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene 10d was unambiguously confirmed through the X-ray diffraction pattern as shown in Fig. 2. The related CIF data of 10d are indicated in the Supporting Information. Interestingly, compound 10d crystals pack in AB-AB layer packing, where the molecules are aligned in anti-parallel fashion (Fig. 3). The molecules in the adjacent layers display weak non-covalent interactions.

Fig. 2.

ORTEP diagram of 10d.

Fig. 3.

Packing diagram of crystal compound 10d along the b axis with carbon (grey), nitrogen (blue) and oxygen (red). Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Based on the literature [36], we proposed mechanism for this Friedel–Crafts-type carbocyclization process as depicted in Scheme 1. Reaction may initiate through the electrophilic addition of olefinic double bond with triflic acid to form carbocation 10 via Markovnikov's addition. The formation of Markovnikov intermediate is favoured as the neighbouring alkyl substituents significantly stabilize the carbocation 11. Subsequently, intramolecular cyclization via electrophilic aromatic substitution gives tricyclic intermediate 12. Finally, deprotonation of intermediate 12 furnishes the desired carbocyclic products 10.

Scheme 1.

The proposed mechanism for the TfOH-promoted Friedel–Crafts-type carbocyclization of alkenylated biphenyl derivatives.

2.1. Photophysical properties of 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes 10a–o

Synthesized 9,10-Dihydrophenanthrenes 10a–o with donor-acceptor push-pull system embedded in the aromatic skeleton showed interesting photophysical properties. Our research group have reported the photophysical behaviour of different aromatic scaffolds cored with electron withdrawing and donating functionalities [[37], [38], [39], [40]]. Systematic UV–visible and fluorescence spectral studies of 9,10-Dihydrophenanthrenes compounds 10a–o were carried out to understand the optical properties. The absorption and emission maxima were recorded in CHCl3 (10 μM) as depicted in Fig. 4 and the detailed photophysical characteristics are summarized in Table 3. The UV–visible spectra showed presence of strong absorption bands at λmax = 244–276 nm, assigned to the localized π–π* transition and weak absorption bands at λmax = 341–359 attributed to n–π* transition (Fig. 4a and b). The emission spectra of compounds 10a–o with appropriate substituents emitted strong fluorescence in the blue-yellow region when excited at 330 nm due to the internal charge transfer mechanism (ICT) (Fig. 4c and d).

Fig. 4.

(a) UV–Vis spectra of 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes 10a–g in CHCl3; (b) UV–Vis spectra of 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes 10h–o in CHCl3; (c) Fluorescence spectra of 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes 10a–g in CHCl3 and (d) Fluorescence spectra of 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes 10h–o in CHCl3 (10 μM, λex = 330 nm).

Table 3.

Photophysical parameters of 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes 10a–o.

| Sr. No. | 10 | λmax (abs) (nm) | λmax (em) (nm) | Δῡ (cm−1) | Φf | Eop (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10a | 257, 299, 353 | 431 | 5127 | 0.27 | 3.22 |

| 2 | 10b | 267, 292, 342 | 425 | 5710 | 0.25 | 3.25 |

| 3 | 10c | 261, 291, 342 | 470 | 7963 | 0.19 | 3.57 |

| 4 | 10d | 244, 312, 344 | 423 | 5429 | 0.07 | 3.19 |

| 5 | 10e | 244, 314, 341 | 418 | 5402 | 0.20 | 3.32 |

| 6 | 10f | 255, 325, 352 | 428 | 5045 | 0.14 | 3.30 |

| 7 | 10g | 273, 295 349 | 428 | 5289 | 0.21 | 3.11 |

| 8 | 10h | 270, 291, 350 | 430 | 5316 | 0.18 | 3.24 |

| 9 | 10i | 274, 295, 353 | 434 | 5287 | 0.16 | 3.22 |

| 10 | 10j | 268, 296, 345 | 428 | 5621 | 0.18 | 3.31 |

| 11 | 10k | 262, 294, 345 | 478 | 8065 | 0.18 | 3.23 |

| 12 | 10l | 263, 293, 352 | 481 | 7619 | 0.46 | 3.02 |

| 13 | 10m | 276, 296, 353 | 434 | 5287 | 0.22 | 3.25 |

| 14 | 10n | 262, 295, 344 | 458 | 7235 | 0.14 | 3.35 |

| 15 | 10o | 273, 291, 359 | 435 | 4867 | 0.13 | 3.23 |

All the compounds 10a–o were found to be highly fluorescent and the emission maxima was observed in the range of λmax = 418–481 nm (Table 3, entries 1–15). From Tables 3, it is clear that the nature of the secondary amine on the central aromatic ring significantly tuned the emission wavelength of these compounds. For example, the emission maxima of morpholine substituted compound 10b (λmax = 425 nm) was blue shifted by 6 nm in relation to piperidine substituted compound 10a having λmax = 431 nm (Table 3, entries 1 and 2). Similarly, N-phenylpiperazine incorporated compound 10c (λmax = 470 nm) showed remarkable red shift of 45 nm with respect to 10a (Table 3, entry 3). Further similar trend was observed for compounds 10i (λmax = 434 nm), 10j (λmax = 428 nm) and 10k (λmax = 478 nm) (Table 3, entries 9–11). Emission spectrum of dichloro-substituted compound 10l having N-phenylpiperazine amine was quite broad and was trailing over 600 nm (Table 3, entry 12). Also, methoxy-incorporated 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene 10d (λmax = 423 nm) showed blue shift with respect to parent compound 10a (λmax = 431 nm) while chloro-substituted compound 10i (λmax = 434 nm) displayed slight red shift. This also indicates that presence of electron-withdrawing group in the aromatic ring too influences the emission wavelength of these molecules.

Furthermore, we calculated the Stokes shift (Δss) in wavenumber for all the fluorescence active molecules 10a–o. The Stokes shift obtained from the lowest energy absorption maximum to the highest energy emission maximum was found in the range of 4867–8065 cm−1 (Table 3, entries 1–15) [41]. A larger Stokes shift removes spectrum overlap between absorption and emission, allowing fluorescence detection while lowering interference. The fluorescence quantum yields (ΦF) of the derivatives were determined using quinine sulphate as reference (ΦR = 0.54) in H2SO4 (0.1 M) and it is clear from Table 3 that all the compounds exhibit low to moderate quantum yields [42]. Similarly, the optical band gap of all compounds was found to be in the range of 3.02–3.57 eV (Table 3, entries 1–15).

In order to understand the possibility of the intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) interactions of these compounds, fluorescence spectra were recorded in solvents of different polarity (Fig. 5). The fluorescence spectra of 10l showed solvent polarity induced, red-shifted emission spectrum which is a characteristic of ICT interactions [43] (Table 4) (Ajantha et al., 2016). In this case, the secondary amine and benzene moieties are expected to act as electron-donor and electron-acceptor components respectively. The emission spectra of 10l showed large solvatochromic shift of 67 nm on increasing the solvent polarity from non-polar n-Hexane (λmax = 438 nm) to the polar ethyl acetate (λmax = 505 nm). Further, the Stokes shift values were increase significantly from n-Hexane (Δῡ = 5740 cm−1) to ethyl acetate (Δῡ = 8688 cm−1). Owing to the interesting photophysical properties of the studied compounds and their simple and high-yielding synthesis, they represent excellent candidates for various material and biological applications.

Fig. 5.

Fluorescence spectra of 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene 10l in different solvents (10 μM, λex = 330 nm).

Table 4.

Optical data of 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene 10l measured in different solvents.

| Sr. No. | Solvent | λmax (abs) (nm) | λmax (em) (nm) | Δῡ (cm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | n-Hexane | 289, 299, 350 | 438 | 5740 |

| 2 | Cyclohexane | 281, 302, 351 | 440 | 5763 |

| 3 | Toluene | 292, 303, 354 | 473 | 7107 |

| 4 | CHCl3 | 263, 293, 352 | 481 | 7619 |

| 5 | Dioxane | 275, 303, 352 | 493 | 8125 |

| 6 | Ethyl acetate | 276, 303, 351 | 505 | 8688 |

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have developed a simple and efficient methodology for the synthesis of 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes by the superacid-promoted Friedel–Crafts-type carbocyclization of alkenylated biphenyl derivatives under mild conditions. Single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis of 10d revealed that crystal belongs to triclinic system with P-1 space group with twisted phenyl ring. The present cyclization reaction exhibits notable advantages such as broad substrates scope, operationally simple, excellent functional group compatibility and free from expensive metal-catalyst. The synthesized 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes showed interesting fluorescence properties with λmax in the range of 418–481 nm. Various photophysical parameters such as stokes shift, quantum yield and optical band gap of 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes embedded with donor-acceptor push-pull system were computed using their absorption and emission spectra. A significant positive solvatochromic effect was observed for 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene derivative 10l, which is a characteristic of ICT interactions. Further studies to extend the scope of synthetic utility are in progress in our laboratory.

4. Experimental

4.1. Materials

1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on an AV-400 Bruker spectrometer at 400 MHz and 100 MHz respectively. Deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) was used as the solvent and tetramethylsilane (Me4Si) as an internal standard. IR spectra were recorded on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet Nexus 470FT-IR spectrophotometer and band positions are reported in cm−1. Mass spectra (m/z) were taken on a Shimadzu GC-mass spectrometer-QP2020. REMI DDMS 2545 apparatus was used to measure the melting points. DCM and other solvents were purchased from Avra Synthesis Pvt. Ltd. All other purchased chemicals were used without further purification. All reactions were monitored by TLC performed on Merck KGaA pre-coated sheets of silica gel 60. Column chromatography was carried out on silica gel (Avra synthesis, 100–125 mesh). Eluting solvents are indicated in the text.

4.2. General procedure for the synthesis of functionalized 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes 10a–o

2-arylallylarenes 9 (0.4 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), triflic acid (5.0 equiv.) and DCM (1.0 mL) were charged into a round-bottomed flask and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 0.5–5 h. The progress of reaction was monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC). After the completion of the reaction, reaction mixture was partitioned between chloroform and water. The organic layer was dried (Na2SO4), filtered and concentrated in vacuo. The residue obtained was purified by silica-gel column chromatography (EtOAc/hexane, 1:4) to afford the desired 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes 10a–o.

4.2.1. 1,9-Dimethyl-3-(piperidin-1-yl)-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-carbonitrile 10a

White solid; yield: 89 % (0.112 g, 0.355 mmol); mp: 102–104 °C; IR (ATR): 2944, 2209 (CN), 1588 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.13 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.47–1.59 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.66–1.82 (m, 4H, 2CH2), 2.45 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.56 (dd, J1 = 6.8 Hz, J2 = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.78 (dd, J1 = 5.2 Hz, J2 = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.89–2.98 (m, 1H, CH), 3.03–3.14 (m, 4H, 2NCH2), 7.12–7.32 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.59–7.68 (m, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.3, 19.8, 24.2, 26.3, 32.1, 32.5, 53.8, 107.2, 111.9, 118.3, 124.8, 126.5, 126.9, 128.3, 128.9, 133.0, 138.6, 140.9, 142.6, 156.2 ppm; GC-MS (EI): m/z = 316 (M+).

4.2.2. 1,9-Dimethyl-3-morpholino-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-carbonitrile 10b

White solid; yield 85 % (0.108 g, 0.340 mmol); mp: 157–159 °C; IR (ATR): 2963, 2213 (CN), 1586 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.14 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3), 2.46 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.58 (dd, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.79 (dd, J1 = 5.2 Hz, J2 = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.91–2.99 (m, 1H, CH), 3.08–3.22 (m 4H, 2NCH2), 3.80–3.91 (m, 4H, 2OCH2), 7.15–7.33 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.59–7.71 (m, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.3, 19.8, 32.1, 32.4, 52.4, 67.2, 107.1, 111.7, 118.1, 124.8, 126.6, 127.0, 129.1, 129.3, 132.7, 138.9, 141.3, 142.6, 154.6 ppm; HR-MS (ESI+): m/z = 319.1820 (M+ + 1), Theoretical mass: 319.1732 (M+ + 1).

4.2.3. 1,9-Dimethyl-3-(4-phenylpiperazin-1-yl)-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-carbonitrile 10c

White solid; yield: 86 % (0.135 g, 0.344 mmol); mp: 178–180 °C; IR (ATR): 2961, 2210 (CN), 1586 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.15 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3), 2.47 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.59 (dd, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.80 (dd, J1 = 5.2 Hz, J2 = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.92–3.00 (m, 1H, CH), 3.25–3.41 (m 8H, 4NCH2), 6.82 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.93 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, ArH) ppm, 7.21–7.28 (m, 6H, ArH), 7.62–7.69 (m, 1H, ArH); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.3, 19.8, 32.2, 32.5, 49.6, 52.1, 107.2, 111.9, 116.4, 118.1, 120.0, 124.8, 126.6, 127.0, 129.1, 129.2, 132.8, 138.8, 141.3, 142.6, 151.3, 154.7 ppm; GC-MS (EI): m/z = 393 (M+).

4.2.4. 7-Methoxy-1,9-dimethyl-3-(piperidin-1-yl)-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-carbonitrile 10d

White solid; yield: 92 % (0.127 g, 0.367 mmol); mp: 141–143 °C; IR (ATR): 2961, 2207 (CN), 1586 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.12 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.43–1.55 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.64–1.81 (m, 4H, 2CH2), 2.42 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.53 (dd, J1 = 7.0 Hz, J2 = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.75 (dd, J1 = 5.2 Hz, J2 = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.84–2.95 (m, 1H, CH), 2.99–3.12 (m, 4H, 2NCH2), 3.78 (s, 3H, OCH3), 6.71–6.82 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.11 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.57 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.2, 19.7, 24.2, 26.3, 32.2, 32.9, 53.7, 55.3, 106.3, 111.2, 112.0, 112.1, 118.5, 125.9, 126.2, 127.4, 138.6, 140.8, 144.5, 156.2, 160.2 ppm; HR-MS (ESI+): m/z = 347.2129 (M+ + 1), Theoretical mass: 347.2045 (M+ + 1).

4.2.5. 7-Methoxy-1,9-dimethyl-3-morpholino-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-carbonitrile 10e

White solid; yield: 95 % (0.132 g, 0.380 mmol); mp: 176–178 °C; IR (ATR): 2962, 2211 (CN), 1584 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.13 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3), 2.44 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.56 (dd, J1 = 6.8 Hz, J2 = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.78 (dd, J1 = 5.2 Hz, J2 = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.86–2.97 (m, 1H, CH), 3.08–3.18 (m, 4H, 2NCH2), 3.79 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.82–3.91 (m, 4H, 2OCH2), 6.72–6.83 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.12 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.57 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.3, 19.7, 32.1, 32.8, 52.4, 55.4, 67.2, 106.2, 111.0, 112.1, 112.2, 118.2, 125.6, 126.3, 128.4, 138.9, 141.2, 144.5, 154.6, 160.4 ppm; GC-MS (EI): m/z = 348 (M+).

4.2.5.1. 6,7-Dimethoxy-1,9-dimethyl-3-(piperidin-1-yl)-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-carbonitrile 10f

White solid; yield: 88 % (0.132 g, 0.350 mmol); mp: 141–143 °C; IR (ATR): 2962, 2208 (CN), 1586 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.10 (d, J = 6.f8 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.48–1.60 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.66–1.83 (m, 4H, 2CH2), 2.44 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.57 (dd, J1 = 6.4 Hz, J2 = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.75 (dd, J1 = 5.2 Hz, J2 = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.83–2.92 (m, 1H, CH), 2.99–3.19 (m, 4H, 2NCH2), 3.87 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.89 (s, 3H, OCH3), 6.72 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.06 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.12 (s, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.3, 19.9, 24.2, 26.3, 32.2, 32.3, 53.7, 56.0, 56.4, 106.4, 108.5, 109.8, 111.1, 118.4, 125.4, 127.5, 136.2, 138.5, 140.8, 147.9, 149.9, 156.3 ppm; HR-MS (ESI+): m/z = 377.2235 (M+ + 1), Theoretical mass: 377.2150 (M+ + 1).

4.2.6. 1,7,9-Trimethyl-3-(piperidin-1-yl)-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-carbonitrile 10g

White solid; yield: 86 % (0.113 g, 0.344 mmol); mp: 133–135 °C; IR (ATR): 2958, 2207 (CN), 1588 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.12 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.52–1.60 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.68–1.80 (m, 4H, 2CH2), 2.32 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.44 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.55 (dd, J1 = 6.8 Hz, J2 = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.76 (dd, J1 = 5.2 Hz, J2 = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.86–2.94 (m, 1H, CH), 3.02–3.14 (m, 4H, 2NCH2), 6.99–7.09 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.17 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.53 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.2, 19.8, 21.4, 24.2, 26.3, 32.2, 32.5, 53.8, 106.8, 111.6, 118.4, 124.7, 127.3, 127.6, 127.9, 130.3, 138.6, 138.9, 140.8, 142.5, 156.2 ppm; GC-MS (EI): m/z = 330 (M+).

4.2.7. 7-Fluoro-1,9-dimethyl-3-(piperidin-1-yl)-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-carbonitrile 10h

White solid; yield: 75 % (0.100 g, 0.300 mmol); mp: 127–129 °C; IR (ATR): 2927, 2206 (CN), 1590 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.14 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.48–1.59 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.66–1.80 (m, 4H, 2CH2), 2.44 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.52 (dd, J1 = 7.8 Hz, J2 = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.77 (dd, J1 = 5.2 Hz, J2 = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.85–2.93 (m, 1H, CH), 3.02–3.14 (m, 4H, 2NCH2), 6.86–6.98 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.12 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.53 (dd, J1 = 5.4 Hz, J1 = 9.4 Hz, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 17.2, 18.4, 23.1, 25.3, 31.0, 31.6, 52.7, 106.1, 110.7, 112.3 (d, J = 21.5 Hz), 112.7 (d, J = 21.5 Hz), 117.2, 125.6 (d, J = 33.6 Hz), 126.7, 128.3, 136.8, 139.9, 144.1 (d, J = 7.3 Hz), 155.3, 162.1 (d, J = 247.1 Hz) ppm; HR-MS (ESI+): m/z = 335.1928 (M+ + 1); Theoretical mass: 335.1845 (M+ + 1).

4.2.8. 7-Chloro-1,9-dimethyl-3-(piperidin-1-yl)-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-carbonitrile 10i

White solid; yield: 83 % (0.116 g, 0.332 mmol); mp: 127–129 °C; IR (ATR): 2936, 2209 (CN), 1588 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.14 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.54–1.59 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.73–1.80 (m, 4H, 2CH2), 2.44 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.54 (dd, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.77 (dd, J1 = 5.2 Hz, J2 = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.86–2.95 (m, 1H, CH), 3.03–3.13 (m, 4H, 2NCH2), 7.13 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.20–7.24 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.55 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.3, 19.5, 24.2, 26.3, 31.9, 32.5, 53.7, 107.5, 111.8, 118.2, 126.2, 126.6, 126.9, 127.9, 131.6, 134.6, 137.6, 141.1, 144.3, 156.3 ppm; HR-MS (ESI+): m/z = 352.1677 (M+ + 2), Theoretical mass: 352.1549 (M+ + 2).

4.2.9. 7-Chloro-1,9-dimethyl-3-morpholino-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-carbonitrile 10j

White solid; yield: 84 % (0.118 g 0.336 mmol); mp: 180–183 °C; IR (ATR): 2936, 2208 (CN), 1587 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.14 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH3), 2.46 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.56 (dd, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.79 (dd, J1 = 5.2 Hz, J2 = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.87–2.96 (m, 1H, CH), 3.08–3.18 (m, 4H, 2NCH2), 3.80–3.92 (m 4H, 2OCH2), 7.14 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.19–7.27 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.55 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.3, 19.5, 31.9, 32.4, 52.4, 67.1, 107.4, 111.6, 117.9, 126.2, 126.7, 127.1, 129.0, 131.4, 134.8, 137.9, 141.5, 144.3, 154.7 ppm; GC-MS (EI): m/z = 352 (M+), 354 (M+ + 2).

4.2.9.1. 7-chloro-1,9-dimethyl-3-(4-phenylpiperazin-1-yl)-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-carbonitrile 10k

White solid; yield: 80 % (0.137 g 0.320 mmol); mp: 192–194 °C; IR (ATR): 2962, 2208 (CN), 1583 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.15 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH3), 2.47 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.57 (dd, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.80 (dd, J1 = 5.2 Hz, J2 = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.87–2.96 (m, 1H, CH), 3.24–3.40 (m, 8H, 4NCH2), 6.82 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.93 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.19–7.25 (m, 5H, ArH), 7.57 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.4, 19.5, 32.0, 32.4, 49.6, 52.1, 107.5, 111.7, 116.4, 117.9, 120.1, 126.2, 126.7, 127.1, 128.9, 129.2, 131.4, 134.8, 137.9, 141.4, 144.3, 151.2, 154.8 ppm; GC-MS (EI): m/z = 427 (M+), 429 (M+ + 2).

4.2.10. 5,7-Dichloro-1,9-dimethyl-3-(4-phenylpiperazin-1-yl)-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-carbonitrile 10l

White solid; yield: 68 % (0.126 g, 0.273 mmol); mp: 197–199 °C; IR (ATR): 2209 cm−1 (CN); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.09 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3), 2.48 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.51 (dd, J1 = 7.6 Hz, J2 = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.71 (dd, J1 = 4.4 Hz, J2 = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.79–2.88 (m, 1H, CH), 3.21–3.42 (m, 8H, 4NCH2), 6.82 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.89–6.96 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.15 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.20–7.24 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.34 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.75 (s, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.4, 18.5, 32.0, 34.0, 49.6, 52.1, 107.5, 116.4, 117.1, 117.8, 120.1, 125.2, 129.2, 129.6, 130.1, 130.7, 132.5, 134.2, 135.7, 140.2, 147.7, 151.3, 153.5 ppm; GC-MS (EI): m/z = 461 (M+), 463 (M+ + 2).

4.2.11. 7-Bromo-1,9-dimethyl-3-(piperidin-1-yl)-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-carbonitrile 10m

White solid; yield: 72 % (0.114 g, 0.289 mmol); mp: 164–165 °C; IR (ATR): 2923, 2207 (CN), 1587 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.14 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.47–1.57 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.67–1.79 (m, 4H, 2CH2), 2.44 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.54 (dd, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.76 (dd, J1 = 5.2 Hz, J2 = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.86–2.94 (m, 1H, CH), 3.03–3.14 (m, 4H, 2NCH2), 7.13 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.30–7.40 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.48 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.3, 19.5, 24.1, 26.3, 31.9, 32.4, 53.7, 107.6, 111.7, 118.1, 122.9, 126.4, 127.9, 129.6, 129.9, 132.1, 137.6, 141.1, 144.6, 156.3 ppm; HR-MS (ESI+): m/z = 395.1126 (M+), Theoretical mass: 395.1044 (M+).

4.2.12. 7-Bromo-1,9-dimethyl-3-(4-phenylpiperazin-1-yl)-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-carbonitrile 10n

White solid; yield: 70 % (0.132 g 0.280 mmol); mp: 168–170 °C; IR (ATR): 2944, 2208 (CN), 1588 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.15 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH3), 2.47 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.56 (dd, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.79 (dd, J1 = 5.2 Hz, J2 = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.86–2.96 (m, 1H, CH), 3.24–3.42 (m, 8H, 4NCH2), 6.82 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.93 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.14–7.28 (m, 3H, ArH), 7.33–7.43 (m, 2H, ArH) 7.50 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 17.3, 18.5, 30.9, 31.3, 48.6, 51.0, 106.5, 110.6, 115.4, 116.9, 122.1, 125.4, 127.9, 128.2, 128.6, 129.0, 130.8, 136.8, 140.4, 143.5, 150.2, 153.7 ppm; GC-MS (EI): m/z = 472 (M+), 474 (M+ + 2).

4.2.13. 1,4,9-Trimethyl-3-(piperidin-1-yl)-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-carbonitrile 10o

White solid; yield: 74 % (0.099 g, 0.300 mmol); mp: 126–128 °C; IR (ATR): 2961, 2209 (CN), 1584 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.18 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.52–1.78 (m, 6H, 3CH2), 2.31–2.45 (m, 7H, 2CH3 + CH), 2.70 (dd, J1 = 4.4 Hz, J2 = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.74–2.83 (m, 1H, CH), 3.07–3.45 (m 4H, 2NCH2), 7.20–7.29 (m, 3H, ArH), 7.42–7.50 (m, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 16.7, 17.4, 17.9, 23.3, 25.9, 31.6, 33.0, 51.1, 108.0, 117.9, 124.0, 124.4, 127.0, 128.6, 129.4, 131.9, 132.8, 135.9, 139.8, 142.9, 153.4 ppm; GC-MS (EI): m/z = 330 (M+).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Samata E. Shetgaonkar: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Himanshu Aggarwal: Formal analysis, Data curation. Toshitaka Shoji: Formal analysis. Toshifumi Dohi: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Fateh V. Singh: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Fateh V. Singh is thankful to CSIR New Delhi [Grant No.: 02/(0330)/17-EMR-II] for the financial support. Samata E. Shetgaonkar is thankful to VIT Chennai for providing her fellowship and financial support. We thank the SAIF department, VIT Vellore for spectrometric data. T.D. and T.S acknowledge support from the Ritsumeikan Global Innovation Research Organization (R-GIRO) project and Ritsumeikan NEXT Student Fellow program.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35064.

Contributor Information

Samata E. Shetgaonkar, Email: samatashetgaonkar@unoigoa.ac.in.

Toshifumi Dohi, Email: td1203@ph.ritsumei.ac.jp.

Fateh V. Singh, Email: fatehveer.singh@vit.ac.in.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Kovacs A., Vasas A., Hohmann J. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:1084. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao N., Yang G., Zhang Y., Chen L., Chen Y. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015;30:174. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2015.1046379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuster R., Zeindl L., Holzer W., Khumpirapang N., Okonogi S., Viernstein H., Mueller M. Phytomedicine. 2017;15:157. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boudjada A., Touil A., Bensouici C., Bendif H., Rhouati S. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018;33:3278. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2018.1468328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou D., Chen G., Ma Y.-P., Wang C.-G., Lin B., Yang Y.-Q., Li W., Koike K., Hou Y., Li N. J. Nat. Prod. 2019;82:2238. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao G.-Y., Deng B.-W., Zhang C.-Y., Cui Y.-D., Bi J.-Y., Zhang G.-G. J. Nat. Med. 2018;72:246. doi: 10.1007/s11418-017-1141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bus C., Kusz N., Jakab G., Tahaei S.A.S., Zupko I., Endresz V., Bogdanov A., Burian K., Csupor-Löffler B., Hohmann J., Vasas A. Molecules. 2018;23:2085. doi: 10.3390/molecules23082085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goel A., Sharma A., Rawat M., Anand R.S., Kant R.J. Org. Chem. 2014;79 doi: 10.1021/jo501891w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pratap R., Ram V.J.J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:7402. doi: 10.1021/jo0711079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faidallah H.M., Al-Shaikh K.M.A., Sobahi T.R., Khan K.A., Asiri A.M. Molecules. 2013;18 doi: 10.3390/molecules181215704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhojgude S.S., Bhunia A., Gonnade R.G., Biju A.T. Org. Lett. 2014;16:676. doi: 10.1021/ol4033094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu C., Shi Y., Xu M.-H., Lin G.-Q. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1243. doi: 10.1021/ol800122x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roman D.S., Takahashi Y., Charette A.B. Org. Lett. 2011;13:3242. doi: 10.1021/ol201160s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corrie T.J.A., Ball L.T., Russell C.A., Lloyd-Jones G.C.J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:245. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campeau L.-C., Parisien M., Leblanc M., Fagnou K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9186. doi: 10.1021/ja049017y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jana R., Chatterjee I., Samanta S., Ray K.J. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4795. doi: 10.1021/ol801882t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y., Yepremyan A., Ghorai S., Todd R., Aue D.H., Zhang L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:7795. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki Y., Nemoto T., Kakugawa K., Hamajima A., Hamada Y. Org. Lett. 2012;14:2350. doi: 10.1021/ol300770w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu Y., Sun X., Wan B., Lu Z., Zhang Y. Chem. Commun. 2020;56 doi: 10.1039/d0cc04602g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rueping M., Nachtsheim B.J. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2010;6:6. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.6.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heravi M.M., Zadsirjan V., Saedia P., Momeni T. RSC Adv. 2018;8 doi: 10.1039/c8ra07325b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sumita A., Ohwada T. Molecules. 2022;27:5984. doi: 10.3390/molecules27185984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh S., Hazra C.K. Synthesis. 2024;56:368. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Womack G.B., Angeles J.G., Fanelli V.E., Heyer C. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:7046. doi: 10.1021/jo070952o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prakash G.K.S., Paknia F., Vaghoo H., Rasul G., Mathew T., Olah G.A. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:2219. doi: 10.1021/jo9026275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olah G.A., Germain A., Lin H.C., Forsyth D.J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:2928. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li A., Gilbert T.M., Klumpp D.A. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:3654. doi: 10.1021/jo8003474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li A., DeSchepper D.J., Klumpp D.A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:1924. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ichikawa J., Jyono H., Kudo T., Fujiwara M., Yokota M. Synthesis. 2005;1:39. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuchibe K., Jyono H., Fujiwara M., Kudo T., Yokota M., Ichikawa J. Domino Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17 doi: 10.1002/chem.201100618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramulu B.V., Reddy A.G.K., Satyanarayana G. Synlett. 2013;24:868. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramulu B.V., Kumar D.R., Satyanarayana G. Synlett. 2017;28:2179. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eom D., Park S., Park Y., Ryu T., Lee P.H. Org. Lett. 2012;14:5392. doi: 10.1021/ol302271w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roy A., Gao H., Klare H.F.T., Oestreich M. Synthesis. 2023;55:1602. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shetgaonkar S.E., Singh F.V. Synth. Commun. 2020;50:2511. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao H.-S., Dou F., Zhang A.-L., Sun R., Zhao L.-M. Synthesis. 2017;49:1597. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krishnan M., Singh F.V. J. Mol. Struct. 2022;1256 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Subashini C., Singh F.V. ChemistrySelect. 2020;5:7452. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanimoxhi R., Singh F.V. J. Mol. Struct. 2020;1219 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subashini C., Kennedy L.J., Singh F.V. J. Mol. Struct. 2021;1226 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balijapalli U., Udayadasan S., Shanmugam E., Iyer S.K. Dyes Pigm. 2016;130:233. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palashuddin S.K., Chattopadhyay A. RSC Adv. 2014;4 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ajantha J., Varathan E., Bharti V., Subramanian V., Easwaramoorthi S., Chand S. RSC Adv. 2016;6:786. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.