Abstract

Purpose

Fueled by the prescription opioid overdose crisis and increased influx of illicitly manufactured fentanyl, fentanyl overdoses continue to be a public health crisis that has cost the US economy over $1 trillion in reduced productivity, health care, family assistance, criminal justice, and accounted for over 74,000 deaths in 2023. A recent demographic shift in the opioid crisis has led to a rise in overdose deaths among the Latinx population. Harm reduction interventions, including the use of naloxone and fentanyl test strips, have been shown to be effective measures at reducing the number of opioid overdose deaths. The aim of this scoping review is to summarize naloxone and fentanyl test strip interventions and public health policies targeted to Latinx communities.

Methods

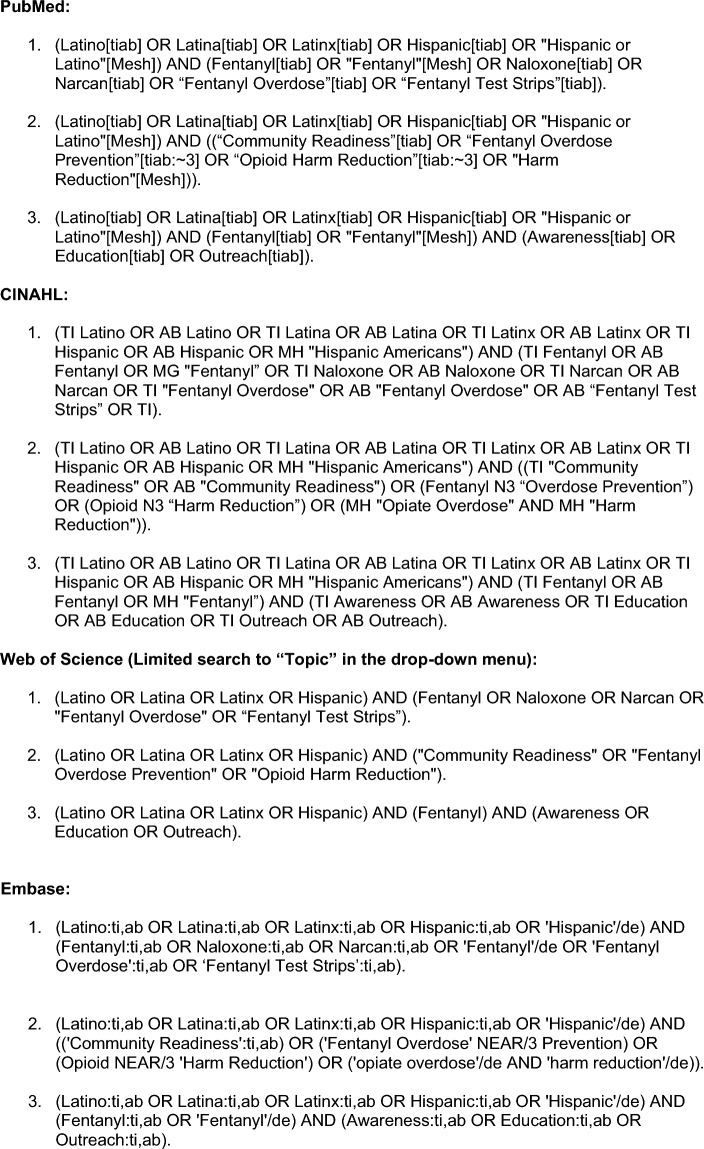

PubMed, CINHAL, Web of Science, Embase, and PsycINFO research databases using the keywords “fentanyl,” “Latinx,” “Harm Reduction,” “Naloxone,” and “Fentanyl Test Strips'' to identify studies published between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2023. Endnote and Covidence software were used to catalog and manage citations for review of studies. Subsequently, studies that met inclusion criteria were then summarized using resulting themes.

Results

Twenty-seven articles met the inclusion criteria and were further abstracted for the scoping review. Of these articles, 77.7% (n = 21) included a naloxone intervention, while only 11.1% (n = 3) included a fentanyl test strip intervention. Furthermore, 30.1% (n = 8) of these studies were Latinx targeted, and 7.7% (n = 2) of the studies were adapted for Latinx populations. Four themes, including an overall lack of knowledge and awareness, a lack of access to harm reduction or opioid overdose prevention resources, an overall lack of culturally adapted and/or targeted interventions, and restrictive and punitive policies that limit the effectiveness of protective factors were highlighted in this scoping review.

Conclusion

Limited published research exists on the use of emerging harm reduction behaviors, such as the use of naloxone and fentanyl test strips as community intervention strategies to prevent opioid overdose deaths. Even fewer publications exist on the targeting and cultural adaptation of harm reduction interventions responsive to Latinx communities, especially those using theoretical approaches or frameworks to support these interventions. Future research is needed to assess the unique needs of Latinx populations and to develop culturally responsive programs to prevent opioid-related overdose deaths among this population.

Keywords: Fentanyl, Overdose, Naloxone, Fentanyl test strips, Latinx, Harm reduction

Introduction

Over the last decade, fentanyl overdoses in the United States have climbed to staggering proportions. In 2021, more people between the ages of 15–54 died from an opioid-related overdose than from COVID-19 [1]. In 2022, fentanyl, also known as “Dance Fever,” “Dragon’s Breath,” or “Tango and Cash,” resulted in the deaths of over 100,000 individuals in the United States [2]. The loss of life resulting from fentanyl and its analogs has reached such a devastating level that fentanyl-related overdoses have been propelled into a public health emergency and garnered prominence on the national political stage [3–5]. In the United States, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) classifies fentanyl as a schedule II narcotic under the United States Controlled Substances Act of 1970. This classification is reserved for drugs that are considered high risk for both physical and psychological dependence and have a high capacity for both use disorder and misuse [6]. Due to the increased influx of illicitly manufactured fentanyl, the DEA has also identified China and Mexico as significant producers of illicitly manufactured fentanyl found in the United States [7–9]. As the opioid crisis in the United States continues, the need for increasing the effectiveness of overdose interventions, such as naloxone and fentanyl test strips (FTS) distribution and educational interventions will become critical in curtailing the effects of illicitly manufactured fentanyl.

Nationally, more than ten million people over the age of 12 are estimated to have engaged in opioid misuse over the past year [10–13]. Of these, over two million of those who misused opioids identify as Latinx/Hispanic (Here, Latinx is used as a gender-neutral term for self-identifying Latin individuals [13]. Overall, opioid overdose deaths have steadily increased throughout the nation, with the death rates among the Latinx population doubling between 1999 and 2017 [14, 15]. More specifically, the greatest increase in opioid-related deaths among this population is due to synthetic opioids, most notably fentanyl. Fentanyl is the most commonly involved opioid in unintentional overdose deaths among the Latinx population at 40.2% [16]. These fentanyl-related opioid overdose deaths have increased 617% over the past ten years [16].

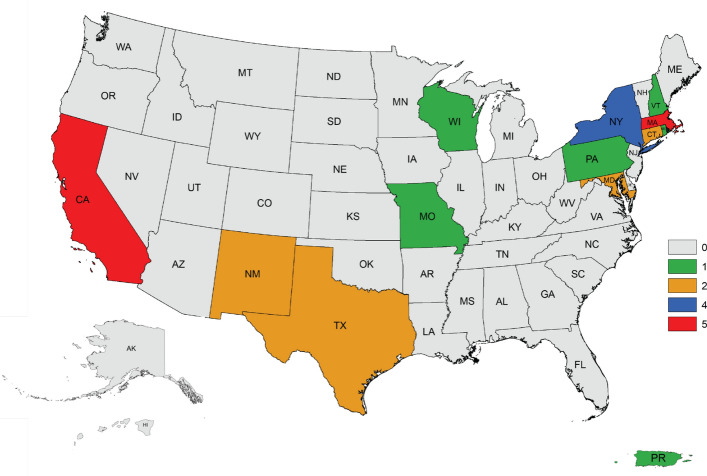

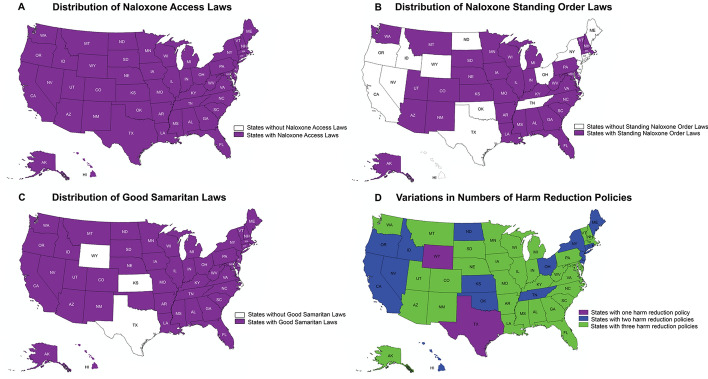

Naloxone and FTS are considered effective overdose prevention interventions, resulting in their widespread use in public health and social service programs in states with supportive policies [13, 17]. Indeed, public health policies that aim to strengthen data collection, safer prescribing practices, stigma and harm reduction, treatment expansion, and criminal justice reform are critical areas of the public health spectrum that may serve to improve the effectiveness of interventions involving naloxone and FTS [18]. While policies such as Naloxone Access Laws, Naloxone Standing Orders, and Good Samaritan Laws have been developed and enacted to increase access to Naloxone and offer legal protection to bystanders who intervene in an overdose situation, not all states have enacted these harm reduction policies [19]. Harm reduction policies are currently composed of one or a combination of three major policies. These policies are Naloxone Access Laws, Naloxone Standing Order Laws, and Good Samaritan Laws. Naloxone Access Laws provide legal immunity provisions for individuals who prescribe, dispense, or administer naloxone [20]. Naloxone Standing Order Statutes authorize pharmacists to dispense naloxone under a standing prescription, eliminating the need for a patient-prescriber encounter [21]. Lastly, Good Samaritan Laws provide legal protection to bystanders in the event that they may need to intervene in an overdose incident. The purpose of this approach is to encourage people to help those experiencing an overdose without fear of legal liability [22]. While these statutes aim to expand access to naloxone and offer legal protections, some states, such as Texas, have yet to enact the Naloxone Standing Order or Good Samaritan statutes [23]. Limiting protections for and access to Latinx communities further decreases the likelihood of successfully reducing fentanyl-related overdose rates, especially among minority populations. Furthermore, as of 2020, all states have enacted Naloxone Access laws. However, only 33 states enacted Naloxone Access, Naloxone Standing Order, and Good Samaritan laws. Conversely, two states, Texas and Wyoming, have enacted only Naloxone Access Laws.

Understanding the planning, implementation, and evaluation of opioid-related harm reduction interventions responsive to the unique needs of the Latinx/Hispanic population in the United States is an area of emerging priority. The Latinx population is experiencing a time of significant population growth in the United States [24]. The US Latinx community grew to over 62.5 million people in 2021, representing a twenty-four percent increase in just eleven years [24]. This significant growth accounts for more than 52% of the population growth of the entire United States [24]. This population continues to face numerous health challenges due to a variety of structural, cultural, and social barriers to health services, as well as significant disparities in health outcomes ranging from HIV infections to type 2 diabetes, to opioid overdose deaths [25, 26]. These disparities are further exacerbated by social factors such as limited health insurance access and utilization, higher rates of medical distrust, and lower rates of medical adherence [27]. Cultural barriers to seeking care, including language barriers, legal status, stigma, and discrimination, are pervasive, significant, and impactful to these communities. Despite these barriers, there are opportunities for continued improvement in health outcomes due to facilitating and protective factors such as more positive attitudes and improving levels of trust towards health interventions [28–32].

Specifically related to opioid misuse, many fentanyl transportation routes traverse Latin America to the United States. This observation, in concert with cultural, economic, and social barriers, may contribute to an environment for the off-label use and sharing of both prescribed and illicit medications [16, 17]. These are only a few of the issues that result in the ongoing increases in unintentional opioid-related overdose deaths among Latinx populations [16]. As Latinx populations in the United States continue to grow, it is important to meet this population’s health and social needs.

Harm reduction strategies are proven to mitigate the number of unintentional opioid-related overdose deaths [33]. The harm reduction approach acknowledges abstinence as the ideal outcome but takes a person-centered strategy that seeks to mitigate risks through the provision of safer choice options [34]. Harm reduction approaches to mitigate the impact of opioid misuse and its associated health effects can include but are not limited to, the use of naloxone and the use of FTS [17, 35–37]. It is estimated that approximately 70% of unintentional opioid overdose deaths could be avoided through known harm reduction strategies [13]. Therefore, with the sharp increase in opioid-related deaths among Latinx populations, more understanding is needed to assess the viability of the implementation of harm reduction strategies and supportive policies for this at-risk population [13]. To this end, a literature review was conducted to describe interventions and policies used with Latinx populations.

Methods

Five established research databases (PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science) were used to search and compile available publications. The established inclusion criteria for the review were studies published between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2023, studies published in the English language, and studies based in the United States or its territories. Both qualitative and quantitative studies that met the inclusion criteria were included for review. The scoping review was conducted utilizing the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [38]. The University of Texas at Austin and University of Nevada, Reno library portals allowed for the electronic search of the databases for analysis. The search included a range of terms, including text words and amended vocabulary words, to elicit maximum results. The search terms included Latin*, Hispanic, fentanyl, naloxone, fentanyl overdose, fentanyl test strips, community readiness, overdose prevention, community readiness, opioid harm reduction, harm reduction, education, and outreach. These terms were combined with Boolean operators such as AND and OR for additional results.

Planned searches were queried using independent and sequential searches of the established strategy. The results were gathered as Research Information System (.ris) files, and these files were subsequently imported into the Covidence software system (Melbourne, Australia) for title, abstract screening, full-text screening, and data extraction. Covidence software was used to eliminate duplicate articles gathered from queries. Upon deduplication in Covidence, amended files were also imported into the Zotero or Endnote reference management software for ease of gathering full texts of included studies that were not automatically uploaded into Covidence and to create memos and notes of the reviewed articles.

Five established criteria were used to determine inclusion in the scoping review: (1) discussion of harm reduction strategies, such as distribution of naloxone or use of FTS; (2) inclusion of Latinx/Hispanic populations in the study; (3) health context of opioid use/misuse; (4) study published in English; (5) study occurred in the United States or its territories. Articles were excluded if they did not explicitly mention opioids or include reference to Latinx/Hispanic populations. A study must have met all five inclusion criteria in order for it to be considered for review.

Screening of titles and abstracts of de-duplicated results were conducted independently for each article by two authors (GL and GD) with initial discussion on operational definitions and inclusion criteria established prior to coding. Articles meeting initial screening criteria were moved to the second stage of full-text screening prior to data extraction. Any article accepted from the initial title and abstract screening from either coder (GL and GD) was included for a full-text screening. Following a full-text screening by the two authors, independent decisions by each author were discussed during a meeting that included the further refinement of operational definitions and inclusion criteria. Initial matched decisions after full-text review were moved into the data extraction phase. Those articles with unmatched decisions were discussed and reconciliation of coding decisions was established through a reassessment of the inclusion criteria. Resolved matches that met inclusion criteria were also moved to the data extraction phase. The authors took detailed notes of discussions and decision-making throughout the process.

Additional quality assessment was ensured through inter-rater reliability (IRR) calculations of the percentage of agreement and Cohen’s kappa prior to unmatched decision reconciliation and data extraction. The percentage of agreement was calculated at 97.3% (393/404), showing strong levels of agreement. As an additional measurement of reliability, Cohen’s kappa was calculated to assess the degree of IRR between the two coders that also account for chance. The Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated with a value of 0.761, indicating a substantial level of agreement.

A standard data extraction template was created using Covidence for those articles that met the abstract and full-text review phases of analysis. Within the data extraction template, several fields were collected, including (1) article details (authors, year of publication, title, journal); (2) study details (aim, study design, participant/sample characteristics); (3) Latinx/Hispanic details, such as percentage/total number of Latinx/Hispanic participants; whether the research was “Latinx/Hispanic targeted” which was defined as resources specifically designed to address the needs of Latinx and Hispanic communities who are disproportionately affected by fentanyl overdoses and/or “Latinx/Hispanic intervention adapted” that was defined as existing evidence-based interventions that were modified to better suit the needs and cultural context of the Latinx and Hispanic communities; (4) intervention characteristics (phase in intervention: coded as planning/assessment, implementation, or evaluation; type of intervention: coded as Narcan/naloxone and/or FTS or neither; theory/framework utilized: open-ended or coded as NA if none were applied); (6) study results (outcomes, recommendations, limitations). Using axial and open coding techniques, an iterative process was used to establish and stratify themes of outcomes and recommendations listed within the studies.

Results

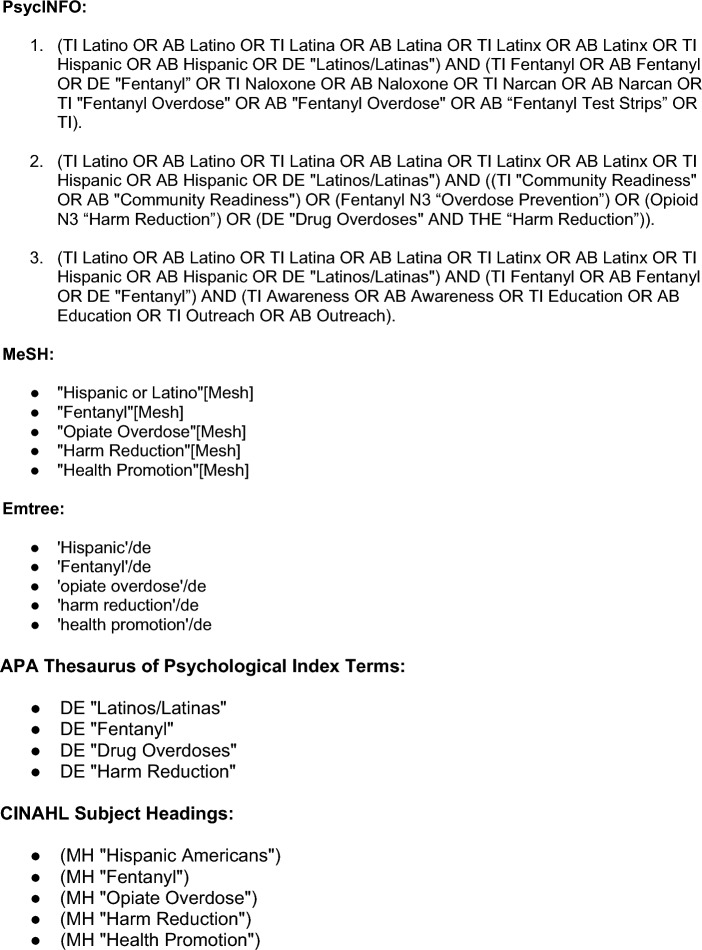

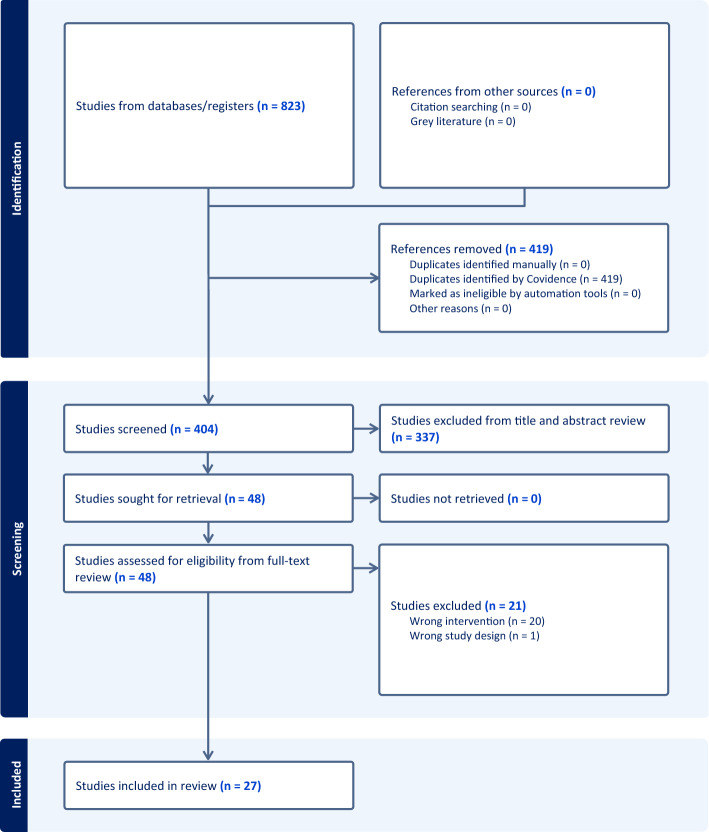

The screening was conducted in a four-stage process using a documented search strategy (Fig. 1). The scoping review yielded a total of 823 studies that were imported for screening (Fig. 2). In stage 1 of the review process, 419 duplicates were identified by Covidence and were removed from further analysis, leaving 404 studies for review. In stage 2, 404 studies were screened through an abstract review process by the authors (GL and GD), matching the study abstracts to the inclusion criteria. Any studies that were unclear in meeting inclusion criteria were also included for full-text review to determine inclusion. In total, 337 studies were excluded from the stage 2 evaluation process review. In stage 3, 48 studies were subject to a full-text review. Twenty-one of the studies were excluded after a full-text review due to having an intervention or study design that did not meet the inclusion criteria. In total, 27 studies from 11 states and Puerto Rico were included for data abstraction (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Documented search strategy used in each of the five established research databases

Fig. 2.

PRISMA diagram visualization of the identification, screening, and included studies using the documented search strategy

Fig. 3.

Individual states and Puerto Rico with the number of studies that met the inclusion criteria for review

All 27 studies were empirical and met the inclusion criteria for data abstraction. Of the 27 studies, 73% (n = 19) explicitly included Narcan/naloxone, such as prescribed naloxone interventions, community-distributed interventions, peer-distributed interventions, or take-home naloxone interventions. Conversely, only 11.5% (n = 3) of studies focused on fentanyl test strip strategies that included both fentanyl strip interventions or a discussion of fentanyl test strips and drug checking services (DCS) more broadly. These results highlight the apparent underutilization of FTS compared to the more reactive interventions involving Narcan/naloxone among Latinx communities. A total of 30.1% (n = 8) of these studies explicitly studied or targeted the Latinx/Hispanic population through oversampling, researching an area with a large Latinx/Hispanic demographic, or including racial/ethnic comparisons with adequate sample sizes. Finally, 7.7% (n = 2) of the studies were adapted interventions for Latinx populations where the interventions included cultural adaptation, language adaptation, or the study design focused on assessments unique to the Latinx/Hispanic community (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study ID | Title | Author | Journal | Aim of Study | Study design | Participation | Total number/ percentage of Hispanic/Latinx participants | Hispanic/Latinx | State/Territory | Phase in Intervention Life Cycle | Type of intervention | Theory/Framework Utilized |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abadie 2023 | I don't want to die: a qualitative study of coping strategies to prevent fentanyl-related overdose deaths among people who inject drugs and its implications for harm reduction policies | Abadie | Harm Reduction Journal | Interviews to document participants’ experiences of injection drug use after the arrival of fentanyl and the strategies they implemented to manage overdose death risks | Qualitative research | 38 PWID in rural Puerto Rico | 100% (n = 38) | Hispanic/Latinx community targeted | Puerto Rico | Planning/Assessment | Neither | NA |

| Abdelal et al., 2022 | Real-world study of multiple naloxone administration for opioid overdose reversal among bystanders | Abdelal, R., Raja Banerjee, A., Carlberg-Racich, S. et al | Harm Reduction Journal | To determine the patterns of naloxone use, including multiple naloxone administrations (MNA) and preferences among bystanders who have used naloxone for opioid overdose reversal | Cross sectional survey | 125 adult US residents who administered 4 mg Narcan® Nasal Spray during an opioid overdose in the past year | 2% (n = 3) | N/A | N/A | Planning/Assessment | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

| Ashford et al., 2018 | Peer-delivered harm reduction and recovery support services: initial evaluation from a hybrid recovery community drop-in center and syringe exchange program | Ashford, R. D., Curtis, B., & Brown, A. M | Harm Reduction Journal | To conduct an initial evaluation of a hybrid recovery community organization providing peer recovery support services (PRSS) as well as peer-based harm reduction services | Cross sectional survey | 417 participants participating in peer recovery support services in MO | 2.4% (n = 10) | N/A | Missouri | Evaluation | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

| Bagley et al., 2018 | Expanding access to naloxone for family members: The Massachusetts experience | Bagley, S. M., Forman, L. S., Ruiz, S., Cranston, K., & Walley, A. Y | Drug and Alcohol Review | Using Massachusetts Department of Public Health data, the aims are to: (i) describe characteristics of family members who receive naloxone; (ii) identify where family members obtain naloxone; and (iii) describe characteristics of rescues by family members | Retrospective review | Enrollees from MA Naloxone Distribution Program from 2008 to 2015 (n = 40,801). Compares family members to non-family member enrollees | 12% (n = 4893) | N/A | Massachusetts | Evaluation | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

| Bailey et al., 2023 | Drug checking in the fentanyl era: Utilization and interest among people who inject drugs in San Diego, California | Bailey, K., Abramovitz, D., Artamonova, I., Davidson, P., Stamos-Buesig, T., Vera, C. F., Patterson, T. L., Arredondo, J., Kattan, J., Bergmann, L., Thihalolipavan, S., Strathdee, S. A., & Borquez, A | International Journal of Drug Policy | To collect information about drug use trends, the drug market, service utilization, overdose, and infectious diseases from PWID along the US-Mexico border. This study specifically explored drug checking services (DCS) | Longitudinal cohort study | 426 PWID San Diego resident participants who had completed DCS survey questions | 60% (n = 252) | Hispanic/Latinx community targeted | California/Tijuana, Mexico | Planning/Assessment | Fentanyl Test Strips | NA |

| Barboza and Angulski. 2020 | A descriptive study of racial and ethnic differences of drug overdoses and naloxone administration in Pennsylvania | Barboza, G, E., Angulski, K | International Journal of Drug Policy | To investigate the spatio-temporal distribution of drug overdoses in Pennsylvania by race/ethnicity, describe differences in naloxone administration, response, survivorship and revival according to race/ethnicity of the individual receiving an overdose response | Retrospective cohort | 10,290 drug overdose incidents from the Pennsylvania Overdose Information Network (ODID) | 6.9%(n = 8,586) | N/A | Pennsylvania | Evaluation | Narcan/ Naloxone | N/A |

| Bennett et al., 2022 | Naloxone protection, social support, network characteristics, and overdose experiences among a cohort of people who use illicit opioids in New York City | Bennett, A. S., Scheidell, J., Bowles, J. M., Khan, M., Roth, A., Hoff, L., Marini, C., & Elliott, L | Harm Reduction Journal | To begin to explore the relationship between different types of social network supports and naloxone availability during overdose events | Prospective cohort study | 575 NYC adults who reported non-medical opioid use in the last 3 days | 39.8% (n = 229) | N/A | New York | Planning/Assessment | Narcan/ Naloxone | Social Network Theory (centered in) |

| Boeri and Lamonica.2021 | Naloxone perspectives from people who use opioids: Findings from an ethnographic study in three states | Boeri, M., & Lamonica, A. K | Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners | To better understand naloxone experiences among active users of opioids living in suburban communities | Ethnographic study | 106 active opioid users from suburban areas of three states | 21% (n = 22) | N/A | Connecticut | Planning/Assessment | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

| Chatterjee et al., 2022 | Broadening Access to Naloxone: Community Predictors of Standing Order Naloxone Distribution in Massachusetts | Chatterjee, A., Yan, S., Xuan, Z., Waye, K. M., Lambert, A, M., Green, T, C., Stopka, T, J., Pollini, R, A., Morgan, J, R., Walley, A, Y | Drug and Alcohol Dependence | To examine the associations of Zip Code level sociodemographic exposures with dispensing events under naloxone standing orders in Massachusetts | Retrospective cohort | 281 of 538 Massachusetts Zip Codes | N/A | N/A | Massachusetts | Evaluation | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

| Coffin et al., 2017 | Behavioral intervention to reduce opioid overdose among high-risk persons with opioid use disorder: A pilot randomized controlled trial | Coffin, P. O., Santos, G. M., Matheson T., Behar, E., Rowe, C., Rubin, T., Silvis., Vittinghoff, E | PLoS One | To pilot test a behavioral intervention to reduce opioid overdose among opioid dependent persons | Randomized controlled trial | 63 adults (18 – 65) who had opioid use disorder, active opioid use, an opioid overdose within 5 years, and prior receipt of naloxone kits | 14% (n = 9) | N/A | California | Implementation | Narcan/ Naloxone | Information-motivation-behavior skills model of behavior change |

| Dwyer et al., 2014 | Opioid Education and Nasal Naloxone Rescue Kits in the Emergency Department | Dwyer, K, D., Walley, A, Y., Langlois, B, K., Mitchell, P, M., Nelson, K, P., Cromwell, J., Bernstein, E | Western Journal of Emergency Medicine | To evaluate the feasibility of an ED-based overdose prevention and intervention program, and describe the overdose risk knowledge, opioid use, overdose, and overdose response among ED patients who received overdose education only or opioid education and naloxone | Observational study | 415 patients | 18% (n = 415) | N/A | Massachusetts | Implementation | Narcan/ Naloxone | N/A |

| Gandara et al., 2023 | Reducing opioid use disorder health inequities within Latino communities in South Texas | Gandara, E., Recto, P., Zapata, J., Moreno-Vasquez, A., Idar, A. Z., Castilla, M., Hernández, L., Flores, M., Escareño, J., Castillo, C., Morales, V., Medellin, H., Vega, B., Hoffman, B., González, M., & Lesser, J | Public Health Nursing | Adaptation and implementation of a CHW-OUD Project ECHO intervention curriculum | Intervention Report | 26 Community Health Workers | 100% (n = 26) |

Hispanic/Latinx community targeted Hispanic/Latinx intervention adaptation |

Texas | Implementation | Neither | NA |

| Gazzola et al., 2023 | Emergency Department Fentanyl Test Strip Distribution in a Large Urban Health System | Gazzola, M. G., Hayman, C., Stansky, D., Genes, N., Wittman, I., Doran, K. M., & Boatright, D. H | Academic Emergency Medicine | To determine feasibility of an emergency department fentanyl test strip distribution program | Observational study | 23 ED patients with opioid related ED visit | Unknown | N/A | New York | Implementation | Fentanyl Test Strips | NA |

| Nolen et al., 2023 | Racial/Ethnic differences in receipt of naloxone distributed by opioid overdose prevention programs in New York City | Nolen, S., Trinidad, J, T., Jordan, A. E., Green, C. T., Jalali, A., Murphy, S, M., Zang, X., Mashall, D.L. B., & Schakman, R. B | Harm Reduction Journal | To evaluate the effectiveness of opioid overdose prevention programs at reaching racial/ethnic minorities in a city whose strategy prioritizes naloxone distribution and assess differences in naloxone access within racial/ethnic groups | Retrospective cohort | 79,555 naloxone kits distributed across 42 neighborhoods | 34.3% (n = 79,555) | N/A | New York | Evaluation | Narcan/ Naloxone | N/A |

| Katzman et al., 2019 | Characteristics of Patients With Opioid Use Disorder Associated With Performing Overdose Reversals in the Community: An Opioid Treatment Program Analysis | Katzman, J. G., Greenberg, N. H., Takeda, M. Y., & Moya Balasch, M | Journal of Addiction Medicine | To identify characteristics of study participants in a large opioid treatment program (OTP) for opioid use disorder (OUD) who used take-home naloxone to perform 1 or more opioid overdose (OD) reversal(s) in the community | Prospective cohort study | 287 participants with OUD in New Mexico | 62% (n = 155) | Hispanic/Latinx community targeted | New Mexico | Evaluation | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

| Katzman et al., 2020 | Association of Take-Home Naloxone and Opioid Overdose Reversals Performed by Patients in an Opioid Treatment Program | Katzman, J. G., Takeda, M. Y., Greenberg, N., Moya Balasch, M., Alchbli, A., Katzman, W. G., Salvador, J. G., & Bhatt, S. R | JAMA Network Open | To measure use of take-home naloxone for overdose reversals performed by study participants with opioid use disorder receiving treatment at an opioid treatment program | Prospective cohort study | 395 participants who are receiving treatment for OUD | 65.8% (n = 260) | Hispanic/Latinx community targeted | New Mexico | Evaluation | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

| Khan et al., 2023 | Racial/ethnic disparities in opioid overdose prevention: comparison of the naloxone care cascade in White, Latinx, and Black people who use opioids in New York City | Khan, M. R., Hoff, L., Elliott, L., Scheidell, J. D., Pamplin, J. R., Townsend, T. N., Irvine, N. M., & Bennett, A. S | Harm Reduction Journal | To improve understanding of access to harm reduction interventions, including naloxone, across racial/ethnic groups | Prospective cohort study | 575 people who use illicit opioids in New York City | 39.8% (n = 229) | Hispanic/Latinx community targeted | New York | Planning/Assessment | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

| Kinnard et al., 2021 | The naloxone delivery cascade: Identifying disparities in access to naloxone among people who inject drugs in Los Angeles and San Francisco, CA | Kinnard, E. N., Bluthenthal, R. N., Kral, A. H., Wenger, L. D., & Lambdin, B. H | Drug and Alcohol Dependence | To identify disparities in access to naloxone among people who inject drugs in Los Angeles and San Francisco, CA | Qualitative research | 536 PWID in San Francisco and Los Angeles, California from 2017 to 2018 | 22% (n = 116) | N/A | California | Planning/Assessment | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

| Lopez et al., 2022 | Understanding Racial Inequities in the Implementation of Harm Reduction Initiatives | Lopez, A. M., Thomann, M., Dhatt, Z., Ferrera, J., Al-Nassir, M., Ambrose, M., & Sullivan, S | American Journal of Public Health | To elucidate a structurally oriented theoretical framework that considers legacies of racism, trauma, and social exclusion and to interrogate the “unmet obligations” of the institutionalization of the harm reduction infrastructure to provide equitable protections to Black and Latinx people who use drugs (PWUD) in Maryland | Qualitative research: Prospective cohort | PWUD (n = 72) and stakeholders (n = 85) in 5 Maryland counties | 2% (n = 2) | N/A | Maryland | Planning/Assessment | NA | New Proposed Framework: "Unmet Obligations" |

| Madden and Qeadan 2020 | Racial inequities in US naloxone prescriptions | Madden, E. F., & Qeadan, F | Substance Abuse | To determine whether the likelihood of receiving a prescription for opioids or a co-prescription for opioids and naloxone differ by patient race/ethnicity | Retrospective cohort | Patients diagnosed with bone fracture (n = 551,103) or chronic pain syndrome [CPS] (n = 173,341) | 1% (n = 7027) | N/A | N/A | Planning/Assessment | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

| Mathias et al., 2023 | Opioid overdose prevention education in Texas during the COVID-19 pandemic | Mathias, C. W., Cavazos, D. M., McGlothen-Bell, K., Crawford, A. D., Flowers-Joseph, B., Wang, Z., & Cleveland, L. M | Harm Reduction Journal | To describe the transitions of an online naloxone training conducted across Texas as part of a statewide targeted opioid response program | Prospective cohort: Case report | 1982 participants attending virtual training | 30.4% (n = 601) | Hispanic/Latinx community targeted; Hispanic/Latinx intervention adaptation | Texas | Implementation | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

| Rosales et al., 2022 | Persons from racial and ethnic minority groups receiving medication for opioid use disorder experienced increased difficulty accessing harm reduction services during COVID-19 | Rosales, R., Janssen, T., Yermash, J., Yap, K. R., Ball, E. L., Hartzler, B., Garner, B. R., & Becker, S. J | Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment | To determine if persons receiving medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) who self-identify as from racial/ethnic minority groups would experience more disruptions in access to harm reduction services than persons identifying as non-Hispanic White | Cluster randomized trial | 133 patients from opioid treatment programs | 10% (n = 13) | N/A | Rhode Island | Implementation | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

| Rouhani et al., 2019 | Harm reduction measures employed by people using opioids with suspected fentanyl exposure in Boston, Baltimore, and Providence | Rouhani, S., Park, J. N., Morales, K. B., Green, T. C., & Sherman, S. G | Harm Reduction Journal | To better understand what behaviors used among PWUD of suspected fentanyl exposure and associated characteristics of engaging in harm reduction behaviors during a time of legal restrictions | Cross sectional survey | PWUD (N = 334) were recruited in three cities in MA through FORECAST study | 20.9% (n = 40) | N/A | Massachusetts, Maryland, & Connecticut | Planning/Assessment | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

| Rowe et al., 2015 | Predictors of participant engagement and naloxone utilization in a community-based naloxone distribution program | Rowe, C., Santos, G., Vittinghoff, E., Wheeler, E., Davidson, P., & Coffin, P. O | Addiction | To describe characteristics of participants and overdose reversals associated with a community-based naloxone distribution program and identify predictors of obtaining naloxone refills and using naloxone for overdose reversal | Prospective cohort | 2500 participants from 2010 to 2013 | 9% (n = 224) | N/A | California | Evaluation | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

| Tilhou et al., 2022 | Characteristics and context of fentanyl test strip use among syringe service clients in southern Wisconsin | Tilhou, A. S., Birstler, J., Baltes, A., Salisbury-Afshar, E., Malicki, J., Chen, G. H., & Brown, R | Harm Reduction Journal | To better understand factors that influence fentanyl test strip use among people who use drugs | Mixed methods: semi-structured interviews and cross-sectional survey | 29 interviews from SSP in WI; 341 survey respondents from SSP in WI | 6.2% (n = 21) for survey | N/A | Wisconsin | Planning/Assessment | Fentanyl Test Strips | NA |

| Unger et al., 2021 | Opioid knowledge and perceptions among Hispanic/Latino residents in Los Angeles | Unger, J. B., Molina, G. B., & Baron, M. F | Substance Abuse | To assess opioid-related knowledge, perceptions, and preventive behaviors among Hispanic residents | Qualitative research: Prospective cohort | 45 Hispanic individuals in Southern California | 100% (n = 45) | Hispanic/Latinx community targeted | California | Planning/Assessment | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

| Weiner et al., 2022 | Evaluating Disparities in Prescribing of Naloxone After Treatment of Opioid Overdose | Weiner, S. G., Carroll, A. D., Brisbon, N. M., Rodriguez, C. P., Covahey, C., Stringfellow, E. J., DiGennaro, C., Jalali. M. S., & Wakeman, S. E | Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment | To evaluate the presence of disparities in prescribing naloxone following opioid overdose | Retrospective cohort study | 1348 unique patients presenting at ED for opioid overdoses | 13% (n = 175) | N/A | Massachusetts & New Hampshire | Evaluation | Narcan/ Naloxone | NA |

When considering the phase of intervention in the lifecycle, 53.8% (n = 14) of the studies existed in the planning and assessment phase, which sometimes included a discussion of lived experiences with harm reduction interventions or an assessment of attitudes, norms, or beliefs related to harm reduction or opioid use in general. 19.2% (n = 5) of the included studies were in the intervention implementation phase, often through a pilot study or a description of a program enacted. Finally, 26.9% (n = 7) of the studies existed in the evaluation phase of the intervention lifecycle, which included an assessment of outcomes or program effectiveness.

In total, 11.5% (n = 3) of studies included some reference to a theory, framework, or behavior change model. One study was grounded in social networks theory [10]. Another used the information-motivation-behavior skills model of behavior change [11]. The third proposed a new theoretical framework of “unmet obligations” that was situated at the intersection of structural injustice, policy change, and critical race understandings [10, 11, 39].

Thematic analysis

Based on the analysis, four themes emerged from the studies: (1) an overall lack of knowledge and awareness of opioid use in general, Narcan/naloxone, FTS, and/or harm reduction strategies; (2) an overall lack of access to harm reduction or opioid overdose prevention resources; (3) an overall lack of culturally adapted and/or targeted interventions; (4) restrictive and punitive policies that limit protective factors (Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcomes, recommendations, and limitations of included studies

| Study ID | Outcomes | Recommendations | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abadie 2023 |

Shared experiences of fear of overdose Harm reduction strategies used such as "hit tests", avoid injecting alone, use of naloxone, and employing fentanyl test strips |

Policy change to allow for harm reduction interventions such as ease of access and use of naloxone and fentanyl test strips More studies needed to understand intersection of health disparities and overdose risks for minority populations |

Small sample of PWID in rural Puerto Rico |

| Abdelal 2022 |

Naloxone use has been effective in preventing overdoses However, a single dose may not be enough Two or more doses were administered in 78% of overdose events, while 3 or more doses were administered in 30% of events |

Need and desire for a higher dose naloxone nasal spray formulation option Continued access to Naloxone |

Small, homogenous sample Small representation of Hispanic/Latinx populations (2%) |

| Ashford et al., 2018 |

Housing status, criminal justice status, and previous health diagnosis significantly related to having multiple engagements Latinx populations least likely to have multiple engagements with program |

Relatable peers with culturally specific knowledge should be used to increase culturally congruent services, especially for Latinx populations Recovery community organizations are well situated and staffed to also provide harm reduction services Recommendations for service delivery include additional, education and outreach for homeless, justice involved, Latinx, and LGBTQ+ identifying individuals |

Self-report measures from case files may be inaccurate Limited variables collected due to secondary analysis of case files Small Latinx representation |

| Bagley et al., 2018 |

Of family members who reported substance use, 75.6% had witnessed an overdose, and they obtained naloxone most frequently at HIV prevention programs Of family members who did not report substance use, 35.3% had witnessed an overdose, and they obtained naloxone most frequently at community meetings Family members were responsible for 20% (n = 860/4373) of the total rescue attempts |

Family members are important contributors to overdose response Targeted intervention strategies of education and naloxone distribution for families is needed |

Self-reported data Social desirability Data from a single program in a single state Limited Latinx representation |

| Bailey et al., 2023 |

One third had heard of DCS; 57% had used DCS Of the last experience with DCS, 98% reported using fentanyl test strips (FTS) Those identifying as Latinx were significantly less likely to have used DCS (adjusted risk ratio: 0.22; 95% CI: 0.10, 0.47), compared to Whites |

Policy changes to provide more access to DCS SSPs can provide access points to DCS Expand awareness and utilization of DCS, especially for Latinx populations |

Convenience sample of PWID in San Diego Self-report and social desirability Purposive sampling of those unvaccinated for COVID-19 |

| Barboza and Angulski. 2020 |

Dosage amounts and rates of survivorship when naloxone was administered did not differ by race/ethnicity Rates of surviving and overdose were lower for whites than Latinos when naloxone was not administered |

Establishing best practices for transitioning overdose victims from the hospital to appropriate longitudinal services while understanding that most of these individuals are not seeking treatment | Data does not include all fatal unintentional drug overdoses. Should not be used as a measure of overdose response and naloxone administration incidents among all first responders |

| Bennett et al., 2022 |

66% had been trained to administer naloxone During most recent opioid use event, 64% reported not having naloxone and a person to administer present More vulnerable and historically disadvantaged populations less likely to be protected from overdose |

Opportunity to harness protective aspects of social networks calls for targeted outreach to non-users More community distribution of naloxone needed More research needed on interventions for solitary users: "test shots", FTS, using smaller amounts |

Limited to NYC with more progressive harm reduction policies Self-report Possible under-reporting of overdose experiences |

| Boeri and Lamonica. 2021 |

60% had experienced an opioid overdose in their lifetime (n = 106) 50% received naloxone to combat an overdose (n = 106) 46% had administered naloxone to others (n = 106) 77% had access to naloxone (n = 106) |

More education and training are needed in overdose prevention and harm-reduction interventions to peers and clinicians More naloxone distribution is needed in communities Need a mix of community and clinical distribution points for naloxone |

Suburban convenience sample Only considered naloxone in harm reduction assessment |

| Chatterjee et al., 2022 |

Communities with a higher proportion of individuals of Hispanic ethnicity had lower odds of any standing order naloxone dispensed at all Communities with higher percentages of people with income greater than $75,000 were less likely to have any naloxone dispensed under NSO at all |

Future studies using causal inference methods that can control confounding by indication should examine how naloxone can reduce overdose deaths | Pharmacy data used in this study from Massachusetts lacked 30% of pharmacies and their dispensing data |

| Coffin et al., 2017 |

33.3% had experienced an overdose in the past four months, similar in both arms (p = 0.95) Those assigned to REBOOT intervention were less likely to experience any overdose (incidence rate ratio [IRR] 0.62 95%CI 0.41†“0.92, p = 0.019) and experienced fewer overdose events (IRR 0.46, 95%CI 0.24†“0.90, p = 0.023) Intervention did not decrease days of no opioid use, sexual risk behaviours, whether or not they sought drug treatment, or whether they carried or administered naloxone |

Interventions to reduce the risk of an overdose event, not just of subsequent death, are warranted More community-based naloxone is needed Efficacy of this intervention in a full trial is needed |

Pilot study with few participants Overdose events collected by self-report: social desirability and recall bias Study in San Francisco may be unique and not generalizable |

| Dwyer et al., 2014 |

No significant differences in behavior in a witnessed overdose between the overdose education and naloxone rescue kits and overdose education-only groups |

This study provides useful information for planning larger studies and programs to further evaluate implementation, benefits, and harms of overdose education and naloxone rescue kits in E.Ds |

Patients may have received overdose education elsewhere Providing nasal naloxone was not randomized; therefore, there was selection bias, and thus may not be generalizable Because this was a survey study, it may have been subjected to recall bias |

| Gandara et al., 2023 | Culturally adapted curriculum implemented for CHWs |

More culturally adapted interventions are needed to reach Latinx populations Interventions are needed that focus on root causes Supportive harm reduction policies that are cultural-responsive to the needs of diverse groups are needed |

Small intervention cohort of 26 CHWs No evaluation of program |

| Gazzola et al., 2023 |

69.5% had heard of fentanyl; 8.7% had prior experience using fentanyl test strips 78.2% accepted the fentanyl test strips Of the 3 respondents reached for follow-up, all reported using the test strips with a positive test result. Two discarded the substance, and 1 reduced the amount used and kept naloxone nearby |

Patients can benefit from FTS distribution in ED settings More studies needed to assess follow-up use of FTS Policies are needed to allow access without criminalizing harm reduction strategies to prevent overdose |

Small sample A single ED intervention Most participants were lost to follow-up |

| Nolen et al., 2023 |

Latino and Non-Latino Other residents had lower rates of receiving naloxone than White residents Black residents continued to have the highest naloxone receipt rate across all racial/ethnic groups |

Identify opportunities for naloxone distribution approaches that could assess and then address reasons for geographic and population variation in naloxone receipt and the geographic and structural barriers |

Only able to include overall fatal overdose rates (as opposed to race/ethnicity-specific rates) at the neighborhood level Implemented larger time periods (quarters) within a one-year study period which may have masked temporal trends in naloxone receipt over time |

| Katzman et al., 2019 |

Participants who had greater odds of using the take-home naloxone to perform OD reversal Received emergency room care themselves for OD (OR = 4.89, 95% CI 1.54†“15.52, P = 0.007) Previously witnessed someone else OD (OR = 5.67, 95% CI 1.24†“25.87, P = 0.025) Tested positive for 2 or more illicit substances at their 6-month urine analysis (OR = 5.26, 95% CI 1.58†“17.54, P = 0.007) Being less than 30 years old (OR = 2.80, 95% CI 1.02†“7.66, P = 0.045) Identifying as Hispanic (OR = 3.98, 95% CI 1.41†“11.21, P = 0.009) |

Harm reduction efforts should use targeted characteristics to identify those most likely to use naloxone Opportunities for harm reduction exist within Hispanic communities and among young adults Social connectedness is an important entry point for take-home naloxone use |

Study unique to NM and may not be generalizable 13% participants were lost to follow-up |

| Katzman et al., 2020 |

18% of participants given naloxone performed 114 overdose reversals in the community 86.9% of participants stated that the person they performed an overdose reversal was a friend, relative, acquaintance, or significant other Prior to study enrolment, only 4.5% of participants had been prescribed naloxone |

Take home naloxone for those in opioid treatment programs are effective and can be scaled up Policies to mandate overdose education and naloxone distribution in opioid treatment facilities are warranted |

Study unique to population of New Mexico Could be open to respondent bias |

| Khan et al., 2023 |

Whites had the highest naloxone coverage across the cascade of training, current possession, and daily access during using and non-using days Blacks had the lowest naloxone coverage across the cascade of training, current possession, and daily access during using and non-using days |

More outreach and training are needed to increase naloxone access and use among Black and Latinx populations People of color are needed in leadership roles for research and harm reduction policy/program development to meet the needs of diverse populations More interventions are needed to address the double stigma of minority status and substance use |

Small sample size Limited generalizability Limits in self-reporting |

| Kinnard et al., 2021 |

72% of PWID have ever received naloxone 35% of PWID currently possess naloxone White participants are more likely to receive naloxone than Black and Latinx populations Housed participants are more likely to possess naloxone than unhoused participants |

More naloxone interventions are needed to engage populations people of colour and those experiencing homelessness |

Self-report Social desirability Limitation in only assessing naloxone experiences in the last six months An urban California sample may not be generalizable |

| Lopez et al., 2022 |

Three unmet obligations were identified through in-depth analysis: Intense enforcement and punitive governance regarding harm reduction materials Historic racialization, social exclusion, and legacies of trauma among PWUD of color `The differential implications of harm reduction policies for populations who experience racialized criminalization |

Implementation of harm reduction policies Assessment of structural dynamics and root causes of social problems for diverse populations Additional resources to uplift communities of colour for access and protections afforded by harm reduction strategies |

Purposeful and targeting sampling that is not fully representative Small sample Limited Latinx representation |

| Madden and Qeadan. 2020 |

Patients of colour with bone fracture or CPS are largely less likely to receive prescriptions for outpatient opioid analgesics than their non-Hispanic White counterparts Native American and Hispanic CPS patients prescribed opioids are more likely to get naloxone prescriptions despite being less likely to get opioid prescriptions |

Need for efforts to assure equitable diffusion of harm reduction intervention of naloxone |

Small Hispanic sample (1%) Specification of Health Facts database is limited |

| Mathias et al., 2023 |

Virtual training reached more learners from a broader geographic region Virtual training reached rural areas and those areas with health worker shortages Virtual and culturally responsive training met the unique needs of Latinx populations |

More online harm reduction trainings are needed More Spanish language and culturally adapted harm reduction trainings are needed Virtual trainings reduce barriers of transportation, childcare and time off work |

Lacked controls to be a formal research study Did not collect data on naloxone outcomes (i.e.: overdose reversals, naloxone administration) Did not collect data on trainees’ substance use behaviour Context of Texas and during a pandemic is not generalizable |

| Rosales et al., 2022 |

Disproportionate impacts were experienced by racial/ethnic minority groups It was 10 harder for racial/ethnic minority groups to access naloxone It was 8× harder for racial/ethnic minority groups to access sterile needles |

Additional outreach strategies needed to ensure equitable access to naloxone and other harm reduction services Supportive policies needed to ensure equitable access to naloxone and other harm reduction services |

Voluntary responses could result in some bias for those that opted in Small sample Analysis grouped White vs. non-White. Diverse groups not independently considered |

| Rouhani et al., 2019 |

84% expressed concern about fentanyl Among those who suspected fentanyl exposure: 12% used less of the drug 10% did not use the drug 5% used more slowly 5% used a “tester shot ” In adjusted logistic regression models, the odds (aOR) of practicing HRB after suspecting fentanyl exposure were increased among PWUD who were non-White (aOR 2.1; p = 0.004) and older (aOR 1.52 per decade of age; p < 0.001) |

Need to identify early adopters of drug checking services Need for peer outreach and support for harm reduction, especially targeted to at risk populations Need for legal and accessible drug checking services |

Self-report Geographically limited study Assumption of causality in harm reduction behaviours |

| Rowe et al., 2015 |

Participants who had witnessed an overdose [AOR = 2.02(1.53–2.66); AOR = 2.73(1.73–4.30)] or used heroin [AOR = 1.85(1.44–2.37); AOR = 2.19(1.54–3.13)], or methamphetamine [AOR = 1.71(1.37–2.15); AOR = 1.61(1.18–2.19)] had higher odds of obtaining a refill and reporting a reversal African American [Adjusted Odds Ratio = 0.63(95%CI = 0.45–0.88)] and Latino [AOR = 0.65(0.43–1.00)] participants had lower odds of obtaining a naloxone refill Latino participants who obtained at least one refill reported a higher number of refills [Incidence Rate Ratio = 1.33(1.05–1.69)] |

More community naloxone distribution programs are diverse populations Need to improve systems for ease in obtaining a naloxone refill Need for further research, including the use of qualitative methods, to better understand the underlying causes of these racial/ethnic differences |

All information is self-reported by participants and may be subject to social desirability and/or recall bias Behavioural characteristics of participants, many of which are subject to changes over time, are only collected during initial registration |

| Tilhou et al., 2022 |

Race and ethnicity, drug of choice, and seeking fentanyl were associated with test strip use Among test strip users, 36.5% use them most of the time or more 80.6% get positive results half the time or more FTS use is influenced by information from suppliers, regular transportation, diverse distribution locations, recommendations from harm reduction staff, and having a safe or private place to use |

Need to promote increase FTS use for stimulants Need FTS outreach to diverse populations Need to increase diversity of distributing locations Need education to correct misperceptions about drug wasting Need to emphasize pre-consumption testing |

Sample of only SSP clients Sample only of southern WI Collected no identifying data so participants could have responded more than once |

| Unger et al., 2021 |

Most participants aware of dangers of opioids and the importance of keeping them out of the reach of children Participants reported stockpiling, sharing, and borrowing prescription medications for financial reasons They perceived marijuana use as a larger problem in the community than opioids They were unaware of the availability of naloxone to reverse overdoses |

Due to knowledge gaps, more outreach and education targeted to the Latinx community is needed Culturally accessible health education is needed in Latinx communities More information on naloxone to prevent overdoses is needed in Latinx communities |

All parents and caregivers of elementary school children (limited sample) All from a single neighbourhood in Los Angeles area (non-generalizable) Sample primarily female and may limited applicability to males |

| Weiner et al., 2022 |

Hispanic/Latinx patients were more likely to receive a prescription when compared to Non-Hispanic White patients (aOR 1.72, 95% CI 1.22†“2.44) No difference occurred between Non-Hispanic Black compared to Non-Hispanic White patients Less than half of patients with an overdose diagnosis code received naloxone |

More widespread use and distribution of naloxone needed for high-risk patients More robust procedures in EDs needed to prescribe naloxone for those who experience an opioid-related overdose Equity-informed implementation of interventions needed |

Retrospective study: some diagnostic codes may not have been fully captured Limited understanding of whether naloxone was prescribed or dispensed Did not examine characteristics of providers |

The most prominent theme was that many members of the Latinx/Hispanic community are unaware of interventions, such as naloxone to prevent opioid overdose deaths, fentanyl test kits to test drugs, or harm reduction strategies in general [40]. Despite lower levels of health literacy related to harm reduction and opioid overdose awareness among all populations, Latinx audiences often demonstrated the least amount of knowledge [17]. The studies clearly showed a lack of outreach to Latinx communities for community education efforts [17].

Latinx individuals also had less access to harm reduction or opioid prevention resources when compared to White, non-Hispanics [41, 42]. Although closely related to a lack of knowledge and awareness, Latinx individuals were less likely to be prescribed naloxone by a medical provider [43, 44] and are also less likely to have access to drug-checking services and FTS than their White, non-Hispanic counterparts [37, 45]. When having access to opioid overdose prevention resources, Latinx populations had greater odds of using the naloxone they bring home [28, 46–48] and were more likely to refill the prescription for naloxone [49, 50]. Finally, after a known fentanyl exposure, Latinx community members are more likely to adopt harm-reduction behaviors [51].

Another theme that emerged is an overall lack of culturally responsive education and intervention programs specifically targeted to Latinx communities. Although interventions exist, the lack of cultural adaptation prevents their overall uptake [52, 53]. Latinx communities are responsive to harm reduction strategies adapted to their culture and language and have shown a willingness to receive education and resources in various formats, including virtually or through the utilization of community health workers [49, 54–56]. However, cultural factors, experiences, restrictive policies, including the war on drugs, and drug paraphernalia laws, impede the inability to distribute naloxone or FTS legally, restrictions on pharmacist-led standing orders on naloxone, and restrictions on peer-based naloxone distribution, further marginalize Latinx communities (Fig. 4). Due to interactions with immigration, discrimination, or stigma, Latinx communities can be more cautious in adopting opioid overdose prevention strategies when residing in communities with restrictive policies [28, 36, 54, 56–58].

Fig. 4.

States with and without Naloxone Access Laws, Naloxone Standing Order Laws, and Good Samaritan Laws

Punitive and restrictive policies related to naloxone and FTS was also a prominent theme throughout this scoping review. Indeed, in Pennsylvania, a lack of supportive policies showed that Latinos were shown to be more likely to be arrested in cases where naloxone was administered compared to Whites and Blacks [59]. Harm reduction studies also advocated for policy changes to allow for increasing the ease of access to naloxone, FTS, and other drug-checking services [36, 56]. In order to advance overdose prevention interventions, one study suggested increasing the inclusion of Black and Latinx individuals in positions of policy leadership to better meet the needs of diverse populations [58]. While major legislative policies aim to increase ease of access to harm reduction strategies, additional work is needed to improve upon the underutilization of these interventions.

Discussion

This scoping review displays the ongoing need for the planning, assessment, implementation, and evaluation of key opioid overdose prevention strategies such as naloxone distribution and the widespread use of FTS, especially among Latinx populations. Overall, the results indicate that more education and outreach are needed on harm reduction strategies, especially strategies that provide choice, options, and innovative solutions. Expanding education efforts related to harm reduction policies among Latinx communities about naloxone and FTS distribution sites, use, and legal protections may present areas of opportunity to increase the utilization of harm reduction measures among the Latinx population. The scoping review highlights a few innovative interventions, such as virtual, culturally responsive training and peer outreach through the use of trained community health workers [43, 54]. Latinx individuals are more open to harm reduction interventions than non-Hispanic Whites but less likely to receive the opioid overdose prevention resources they need to protect themselves and their communities [36, 43].

The needs and resources of the Latinx community present a unique opportunity for intervention. While sources of naloxone distribution encompass a wide array of sites such as emergency departments [60, 61], syringe service programs [62], pharmacies [63], community peer-based interventions [64], opioid agonist treatment services, among others, these distribution methods often lack a cultural framework amenable to acceptance with the Latinx community. Additionally, the distribution of rapid FTS in these settings may provide an added measure of protection, as FTS has been shown to be a more acceptable form of harm reduction, especially among young adults [65, 66]. Culturally, barriers such as cultural norms to buy medication outside of a medical setting or to share medications can put Latinx community members at undue risk of potential opioid overdose death [17]. Socially, restrictive policies preventing access to harm reduction resources, coupled with structural and systemic barriers of past discrimination and stigma within the healthcare system and among law enforcement, created an ongoing threat to optimal health and safety [35, 36, 56]. Restrictive and punitive policy implications may result in limiting the utilization of evidence-based harm reduction measures, increasing fentanyl-related overdose deaths, or increasing stigma, leading at-risk individuals away from seeking help, especially among Latinx individuals. Punitive policies that classify drug checking material, such as FTS, as paraphernalia may serve to further deter members of the Latinx community from utilizing these harm reduction measures. Indeed, efforts in many states’ legislative bodies are underway to remove FTS from being classified as drug paraphernalia. Currently, 32 states still consider “testing equipment for the use in identifying, or in analyzing the strength, effectiveness or purity of controlled substances'' as drug paraphernalia and are therefore outlawed [19].

Yet, culturally relevant opportunities for change also exist, including core Latinx norms of a collectivist culture, a focus on the family, and extended social networks that can serve as protective factors associated with increased use of opioid overdose prevention resources and decreased deaths among this population [10, 47, 55]. More targeted, culturally responsive, and adapted interventions are needed that directly meet the needs of Latinx populations. Examples of such interventions may include increasing language accessibility, incorporating family-centered approaches, religious or spiritual integration, or reducing stigma. Overall, the scoping review elucidated the need for additional interventions in all stages of the intervention lifecycle that are grounded in proven theories and frameworks that may be increasingly impactful to Latinx populations in reducing unintentional opioid overdose deaths.

Conclusion

While reactive interventions involving naloxone continue to expand overall, prophylactic measures such as FTS remain underutilized among Latinx communities. Increasing awareness and access while addressing barriers to accessing FTS may contribute to reducing the number of unintentional fentanyl-related overdose deaths. The Latinx population may also be subjected to additional barriers in accessing FTS. These may include a lack of knowledge, fear of deportation, language barriers, cultural stigma, and financial considerations [17]. Furthermore, many Latinx individuals are unaware of the existence of FTS or do not know how to use them. This may be particularly relevant in rural areas or communities with historically limited access to healthcare resources. Surprisingly, researchers have highlighted a paradoxical phenomenon among Latinx communities, indicating that Latinx individuals may be protected from the prescription opioid crisis as a result of their inability to access care, but this observation does not appear to confer protective effects with respect to obtaining illegal drugs [67].

This scoping review of opioid overdose prevention interventions to promote the use of naloxone and FTS highlights the willingness of Latinx community members to adopt harm reduction strategies. However, limited opportunities for education, outreach, and the provision of resources are available. Interventions that are culturally adapted and responsive are limited, lack theoretical foundations, and are not implemented at scale. Although threats related to the cultural norms of the Latinx community exist, there are also unique opportunities to build upon these cultural norms that can serve as protective factors to achieve optimal health. Moreover, this scoping review highlights the need for future research in the development, implementation, and evaluation of evidence-based, culturally responsive programs to meet the needs of Latinx populations in combating opioid overdose deaths within their communities.

Author contributions

GL designed the study, conducted data extraction, analysis, review and wrote the manscript. GD conducted data extraction, analysis, and review. JU reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no that they have competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Volkow ND, Califf RM, Sokolowska M, Tabak LA, Compton WM. Testing for fentanyl - urgent need for practice-relevant and public health research. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(24):2214–7. 10.1056/NEJMp2302857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kariisa M, O’Donnell J, Kumar S, Mattson CL, Goldberger BA. Illicitly manufactured fentanyl-involved overdose deaths with detected xylazine - United States, January 2019-June 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(26):721–7. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7226a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Donnell JK, Halpin J, Mattson CL, Goldberger BA, Gladden RM. Deaths involving fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and u-47700 - 10 states, July-december 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(43):1197–202. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6643e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths - 27 states, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(33):837–43. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6533a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai Z, Abate MA, Smith GS, Kraner JC, Mock AR. Fentanyl and fentanyl-analog involvement in drug-related deaths. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;196:1–8. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preuss CV, Kalava A, King KC. Prescription of controlled substances: benefits and risks. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls; 2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang C, Lassi N, Zhang X, Sharma V. The evolving regulatory landscape for fentanyl: China, India, and global drug governance. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022. 10.3390/ijerph19042074. 10.3390/ijerph19042074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman J, Hansen H, Bluthenthal RN, Harawa N, Jordan A, Beletsky L. Growing racial/ethnic disparities in overdose mortality before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in California. Prev Med. 2021;153: 106845. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barocas JA, Wang J, Marshall BDL, LaRochelle MR, Bettano A, Bernson D, et al. Sociodemographic factors and social determinants associated with toxicology confirmed polysubstance opioid-related deaths. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;200:59–63. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett AS, Scheidell J, Bowles JM, Khan M, Roth A, Hoff L, et al. Naloxone protection, social support, network characteristics, and overdose experiences among a cohort of people who use illicit opioids in New York City. Harm Reduct J. 2022;19(1):20. 10.1186/s12954-022-00604-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coffin PO, Santos GM, Matheson T, Behar E, Rowe C, Rubin T, et al. Behavioral intervention to reduce opioid overdose among high-risk persons with opioid use disorder: a pilot randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(10): e0183354. 10.1371/journal.pone.0183354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.López CI, Richards DK, Field CA. Perceived discrimination and alcohol-related problems among Hispanic college students: the protective role of serious harm reduction behaviors. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2022;21(1):272–83. 10.1080/15332640.2020.1747040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit. Rockville, MD: 2018 Contract No.: HHS Publication No. (SMA) 18-4742. https://ldh.la.gov/assets/docs/BehavioralHealth/SAMHSA_Opioid_Overdose_Prevention_Toolkit_revised_2018.pdf.

- 14.Valdez A, Cepeda A, Frankeberger J, Nowotny KM. The opioid epidemic among the Latino population in California. Drug Alcohol Depend Rep. 2022;2: 100029. 10.1016/j.dadr.2022.100029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cano M. Drug overdose deaths among us hispanics: trends (2000–2017) and recent patterns. Subst Use Misuse. 2020;55(13):2138–47. 10.1080/10826084.2020.1793367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The Opioid Crisis and the Hispanic/Latino Population: An Urgent Issue. 2020 Contract No.: Publication No. PEP20-05-02-002. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep20-05-02-002.pdf.

- 17.Unger JB, Molina GB, Baron MF. Opioid knowledge and perceptions among Hispanic/Latino residents in Los Angeles. Subst Abus. 2021;42(4):603–9. 10.1080/08897077.2020.1806185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saloner B, McGinty EE, Beletsky L, Bluthenthal R, Beyrer C, Botticelli M, et al. A public health strategy for the opioid crisis. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(1_Suppl):24s–34s. 10.1177/0033354918793627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association. Fentanyl Test Strips. 2021. https://legislativeanalysis.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Fentanyl-Teststrips-FINAL-1.pdf.

- 20.Smart R, Pardo B, Davis CS. Systematic review of the emerging literature on the effectiveness of naloxone access laws in the United States. Addiction. 2021;116(1):6–17. 10.1111/add.15163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gravlee E, Ramachandran S, Cafer A, Holmes E, McGregor J, Jordan T, et al. Naloxone accessibility under the state standing order across mississippi. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7): e2321939. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.21939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atkins DN, Durrance CP, Kim Y. Good Samaritan harm reduction policy and drug overdose deaths. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(2):407–16. 10.1111/1475-6773.13119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.United States Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Texas. Census Bureau QuickFacts. n.d. Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/TX/RHI725222#RHI725222.

- 24.Krogstad JM, Passel JS, Moslimani M, Noe-Bustamante L. Key facts about U.S. Latinos for National Hispanic Heritage Month. Pew Research Center. 2023.

- 25.Pinedo M, Zemore S, Rogers S. Understanding barriers to specialty substance abuse treatment among Latinos. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;94:1–8. 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aguayo-Mazzucato C, Diaque P, Hernandez S, Rosas S, Kostic A, Caballero AE. Understanding the growing epidemic of type 2 diabetes in the Hispanic population living in the United States. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2019;35(2): e3097. 10.1002/dmrr.3097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y, Ngo V, Park SY. Caring for caregivers: designing for integrality. In: Proceedings of the 2013 conference on computer supported cooperative work; San Antonio, Texas, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2013; pp. 91–102.

- 28.Katzman JG, Takeda MY, Greenberg N, Moya Balasch M, Alchbli A, Katzman WG, et al. Association of take-home naloxone and opioid overdose reversals performed by patients in an opioid treatment program. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2): e200117. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heo M, Beachler T, Sivaraj LB, Tsai HL, Chea A, Patel A, et al. Harm reduction and recovery services support (HRRSS) to mitigate the opioid overdose epidemic in a rural community. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2023;18(1):23. 10.1186/s13011-023-00532-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee Y-H, Woods C, Shelley M, Arndt S, Liu C-T, Chang Y-C. Racial and ethnic disparities and prevalence in prescription drug misuse, illicit drug use, and combination of both behaviors in the united states. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2023. 10.1007/s11469-023-01084-0. 10.1007/s11469-023-01084-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fogel J, Adnan M. Trust for online social media direct-to-consumer prescription medication advertisements. Health Policy Technol. 2019;8(4):322–8. 10.1016/j.hlpt.2019.08.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delorme DE, Huh J, Reid LN. Evaluation, use, and usefulness of prescription drug information sources among Anglo and Hispanic Americans. J Health Commun. 2010;15(1):18–38. 10.1080/10810730903460526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldman JE, Waye KM, Periera KA, Krieger MS, Yedinak JL, Marshall BDL. Perspectives on rapid fentanyl test strips as a harm reduction practice among young adults who use drugs: a qualitative study. Harm Reduct J. 2019;16(1):3. 10.1186/s12954-018-0276-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marlatt GA. Harm reduction: come as you are. Addict Behav. 1996;21(6):779–88. 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00042-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gazzola MG, Hayman C, Stansky D, Genes N, Wittman I, Doran KM, et al. Emergency department fentanyl test strip distribution in a large urban health system. Acad Emerg Med. 2023;30:161. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailey K, Abramovitz D, Artamonova I, Davidson P, Stamos-Buesig T, Vera CF, et al. Drug checking in the fentanyl era: Utilization and interest among people who inject drugs in San Diego. California Int J Drug Policy. 2023;118: 104086. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.104086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abdelal R, Raja Banerjee A, Carlberg-Racich S, Darwaza N, Ito D, Shoaff J, et al. Real-world study of multiple naloxone administration for opioid overdose reversal among bystanders. Harm Reduct J. 2022. 10.1186/s12954-022-00627-3. 10.1186/s12954-022-00627-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopez AM, Thomann M, Dhatt Z, Ferrera J, Al-Nassir M, Ambrose M, et al. Understanding racial inequities in the implementation of harm reduction initiatives. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(S2):S173–81. 10.2105/AJPH.2022.306767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boeri M, Lamonica AK. Naloxone perspectives from people who use opioids: findings from an ethnographic study in three states. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2020;33(4):294–303. 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nolen S, Trinidad AJ, Jordan AE, Green TC, Jalali A, Murphy SM, et al. Racial/Ethnic differences in receipt of naloxone distributed by opioid overdose prevention programs in New York City. Res Sq. 2023;68(1):967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosales R, Janssen T, Yermash J, Yap KR, Ball EL, Hartzler B, et al. Persons from racial and ethnic minority groups receiving medication for opioid use disorder experienced increased difficulty accessing harm reduction services during COVID-19. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022;132: 108648. 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Madden EF, Qeadan F. Racial inequities in U.S naloxone prescriptions. Subst Abus. 2020;41(2):232–44. 10.1080/08897077.2019.1686721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kinnard EN, Bluthenthal RN, Kral AH, Wenger LD, Lambdin BH. The naloxone delivery cascade: identifying disparities in access to naloxone among people who inject drugs in Los Angeles and San Francisco, CA. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;225: 108759. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tilhou AS, Birstler J, Baltes A, Salisbury-Afshar E, Malicki J, Chen G, et al. Characteristics and context of fentanyl test strip use among syringe service clients in southern Wisconsin. Harm Reduct J. 2022;19(1):142. 10.1186/s12954-022-00720-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weiner SG, Carroll AD, Brisbon NM, Rodriguez CP, Covahey C, Stringfellow EJ, et al. Evaluating disparities in prescribing of naloxone after emergency department treatment of opioid overdose. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022;139:1–6. 10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katzman JG, Greenberg NH, Takeda MY, Moya BM. Characteristics of patients with opioid use disorder associated with performing overdose reversals in the community: an opioid treatment program analysis. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):131–8. 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dwyer K, Walley AY, Langlois BK, Mitchell PM, Nelson KP, Cromwell J, et al. Opioid education and nasal naloxone rescue kits in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(3):381–4. 10.5811/westjem.2015.2.24909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Madden EF, Qeadan F. Racial inequities in U.S. naloxone prescriptions. Subst Abuse. 2020;41(2):232–44. 10.1080/08897077.2019.1686721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]