Abstract

Chronic itch often clinically coexists with anxiety symptoms, creating a vicious cycle of itch-anxiety comorbidities that are difficult to treat. However, the neuronal circuit mechanisms underlying the comorbidity of anxiety in chronic itch remain elusive. Here, we report anxiety-like behaviors in mouse models of chronic itch and identify γ-aminobutyric acid–releasing (GABAergic) neurons in the lateral septum (LS) as the key player in chronic itch–induced anxiety. In addition, chronic itch is accompanied with enhanced activity and synaptic plasticity of excitatory projections from the thalamic nucleus reuniens (Re) onto LS GABAergic neurons. Selective chemogenetic inhibition of the Re → LS circuit notably alleviated chronic itch–induced anxiety, with no impact on anxiety induced by restraint stress. Last, GABAergic neurons in lateral hypothalamus (LH) receive monosynaptic inhibition from LS GABAergic neurons to mediate chronic itch–induced anxiety. These findings underscore the potential significance of the Re → LS → LH pathway in regulating anxiety-like comorbid symptoms associated with chronic itch.

The ReGlu-LSGABA-LHGABA circuit mediates chronic itch–evoked comorbid anxiety–like behaviors.

INTRODUCTION

Itch is a complex phenomenon that encompasses sensory discriminative, cognitive, motivational, and affective components (1–3). When acute itch becomes chronic and persistent, it often induces negative affective states, such as anhedonia, anxiety, and depression (4–7). Anxiety is one of the most common comorbidities in cases of chronic itch. Growing evidence from human and preclinical studies indicates a higher prevalence of anxiety in patients with various types of chronic itch, including dermatological disorders, systemic conditions with pruritus, and psychogenic itch (4, 8–10). Conversely, anxiety and stress tend to exacerbate the sensory aspect of itch (11–15), prolonging its duration and intensifying its sensation, thus creating a vicious circle of repeated scratching and anxiety. A key to effectively treating comorbid itch and anxiety lies in gaining a deeper understanding of the neurological basis of this comorbidity. However, only few basic animal studies have been conducted to interrogate the neuronal mechanisms underlying the reciprocal interactions between itch and anxiety (16–18). The specific neural circuits implicated in chronic itch–induced anxiety are still not fully understood, which hinders the development of appropriate therapeutic strategies.

The lateral septum (LS) is a large septal region of the rodent brain that is primarily composed of γ-aminobutyric acid–releasing (GABAergic) spiny neurons (19–21). It is recognized as a hub that integrates neural activities from various neocortical and neuromodulatory inputs to regulate distinct emotional states and behavioral responses (22–25). Substantial evidence supports the notion that the LS is critical in the regulation of anxiety (26–28). Although early classical lesion and stimulation experiments produced controversial conclusions regarding whether the LS has an anxiogenic or anxiolytic role in anxiety (29–31), more recent studies identified an increasing number of LS-centered input and output circuits in controlling anxiety-like behaviors in mice. For example, a subset of type 2 corticotropin-releasing factor receptor–marked LS neurons promotes stress-induced behavioral and endocrinological dimensions of persistent anxiety states by sending GABAergic projections to the anterior hypothalamic area (32). In addition, whereas chemogenetic activation of LS-projecting ventral hippocampus cells decreases anxiety (33), optogenetic activation of the infralimbic cortex → LS projections results in enhanced anxiety-like behaviors (34). However, it still remains elusive whether and how LS contribute to chronic itch–induced anxiety.

In this study, we report that chronic itch–evoked anxiety-like behavior is associated with increased excitability and activity of LS GABAergic neurons. This heightened excitability is accompanied by an augmented excitatory drive from the thalamic nucleus reuniens (Re)–glutamatergic afferents. Chemogenetic inhibition of LS GABAergic neurons or the Re → LS circuitry significantly attenuated chronic itch–induced anxiety but without any effect on restraint stress–induced anxiety. Furthermore, we identify the lateral hypothalamus (LH), known to play a critical role in orchestrating and coordinating emotional and motivated behaviors (35, 36), as one of the key downstream regions that receive projections from the LS neurons to convey chronic itch–induced anxiety. These findings represent a major advancement in understanding the neural circuit mechanisms underlying the emotional component of chronic intractable itch, shedding light on promising targets for the treatment of itch-induced negative affect.

RESULTS

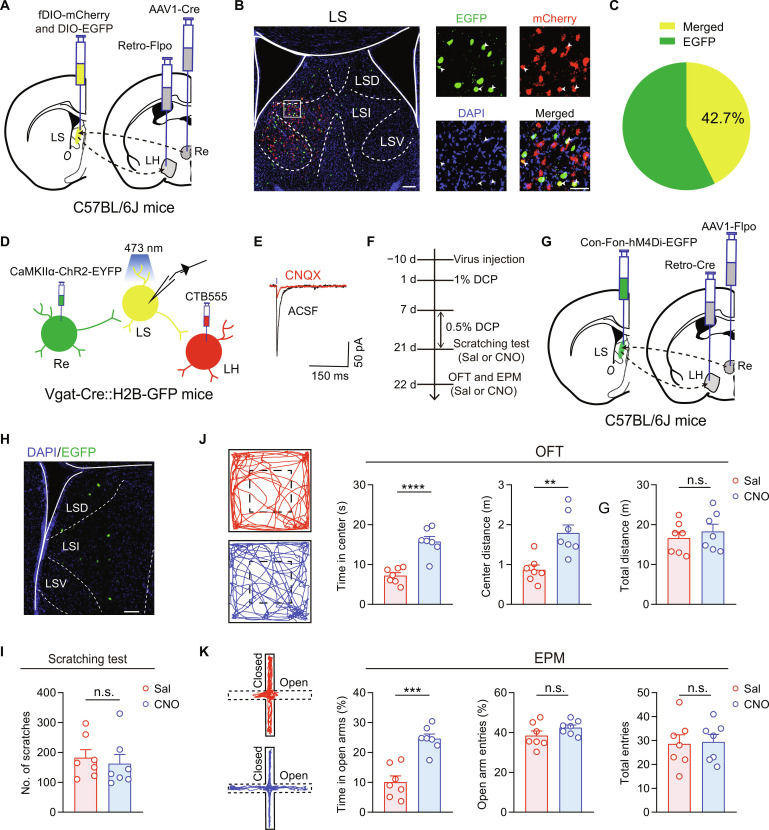

Chronic itch induces anxiety-like behavior in a time-dependent manner

We first examined the effects of chronic itch on anxiety-like behaviors using a mouse model of diphenylcyclopropenone (DCP)–evoked atopic dermatitis as previously described (37–39). After repeated painting of 0.5% DCP for 1 week following an initial sensitization with 1% DCP, the mice exhibited repetitive scratching behaviors, confirming the induction of chronic itch (Fig. 1, A and B). We assessed the anxiety-like behaviors using the open field test (OFT) and elevated plus maze (EPM) test. For OFT, the time spent in the center area was significantly lower in the DCP-treated mice than control mice treated with distilled water (DW) (Fig. 1C), suggesting the occurrence of anxiety-like behavior. For EPM, however, the time spent in open arms showed a trend to decrease in the DCP-treated mice compared with controls, but it did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 1D).

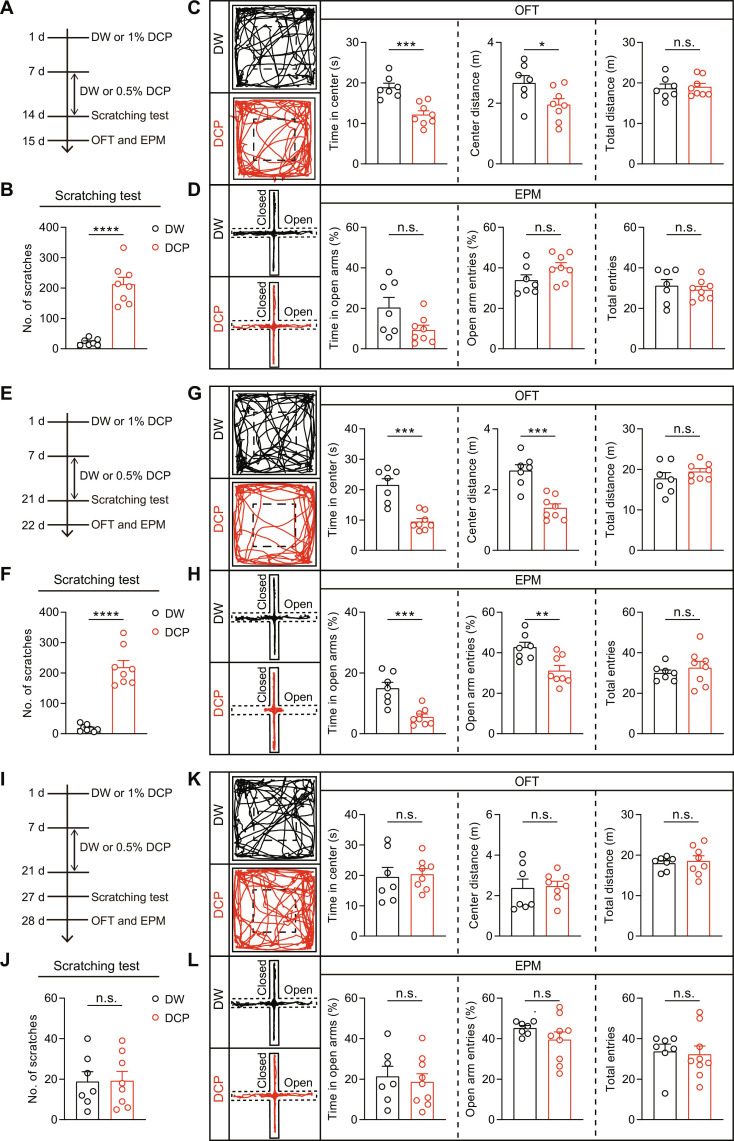

Fig. 1. Time dependence of chronic itch–induced anxiety–like behaviors.

(A, E, and I) Timelines for establishing DCP-induced animal model of chronic itch and the behavioral tests by OFT and EPM. (A) DCP painting for 1 week; (E) DCP painting for 2 weeks; (I) DCP painting for 2 weeks but with the behavioral tests performed at 1 week after the last DCP painting. (B, F, and J) DCP-evoked repetitive scratching bouts for animals subjected to the treatment regime as illustrated in (A), (E), and (I). (B) DW, n = 7 mice; DCP, n = 8 mice. (F) DW, n = 8 mice; DCP, n = 8 mice. (J) DW, n = 7 mice; DCP, n = 8 mice. ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. (C, G, and K) Left: Example trajectories of DW- and DCP-treated mice in OFT. Dashed boxes indicate the center area. Middle and right: Time spent in the center zone, distance traveled in the center zone, and total distance traveled in the open arena. (C) DW, n = 7 mice; DCP, n = 8 mice. (G) DW, n = 7 mice; DCP, n = 8 mice. (K) DW, n = 7 mice; DCP, n = 8 mice. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001, unpaired t test. (D, H, and L) Left: Example trajectories of DW- and DCP-treated mice in EPM. Middle and right: Percentage of time spent in the open arms, percentage of open arm entries, and total number of arm entries. (D) DW, n = 7 mice; DCP, n = 8 mice. (H) DW, n = 7 mice; DCP, n = 8 mice. (L) DW, n = 7 mice; DCP, n = 9 mice. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, unpaired t test. n.s., no significant difference. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Notably, continuation of the DCP treatment for an additional week (Fig. 1, E and F) resulted in anxiety-like behaviors detectable using both the OFT and EPM tests (Fig. 1, G and H). In OFT, both the time spent and distance traveled in the center area were significantly reduced in the DCP-treated mice compared with the DW-treated ones (Fig. 1G). In EPM test, the DCP-treated mice displayed significant reductions in the time spent in open arms and the number of open arm entries compared with the DW-treated control mice (Fig. 1H). Therefore, the chronic itch–induced anxiety–like behavior exhibits time dependence.

No motor deficits could be detected after either 1 or 2 weeks of DCP painting as shown by the lack of difference between DCP- and DW-treated mice in total distance traveled in OFT and total numbers of arm entries in EPM test (Fig. 1, C, D, G, and H). Both the increase in scratching bouts and decreases in OFT/EPM parameters disappeared at 1 week after the end of the 2-week DCP challenge (Fig. 1, I to L), indicating that both the DCP-evoked itch and its comorbid anxiety are reversible within at most 1 week. Thus, unless otherwise indicated, for subsequent experiments, we examined chronic itch–induced anxiety–like behaviors 1 day after the 2-week repeated DCP painting (as shown in Fig. 1E).

To ascertain that DCP-induced anxiety–like behavior was due to chronic itch but not other confounding factors, we performed experiments after ablating spinal itch-specific neurons expressing the gastrin-releasing peptide receptor by intrathecal injection of bombesin-saporin (fig. S1A) (39, 40). As expected, bombesin-saporin significantly reduced not only DCP-induced scratching bouts but also the anxiety-like behavior when compared with the blank-saporin (fig. S1, B to D). These results confirm that the enhanced anxiety-like behavior in response to DCP challenge is caused by the presence of chronic itch.

LS is involved in chronic itch–induced anxiety–like behavior

Because of its dense and widespread input-output circuit connections throughout the brain, the LS is often considered as a nexus for mood and motivation (22). To determine the overall contribution of LS to chronic itch processing, we first examined the expression of c-Fos, a marker of enhanced neural activity, in the LS after mice were subjected to DCP-induced chronic itch modeling. We observed a marked increase in the number of c-Fos–positive neurons across several bregma segments of LS (fig. S2, A to C). Consistent with these findings, pharmacological inactivation of rostral LS [antero-posterior (AP), +0.70 mm; medial-lateral (ML), ±0.40 mm; dorsal-ventral (DV), −3.20 mm] by local injection of muscimol (0.3 nmol, 300 nl per side) led to a marked attenuation of DCP-evoked anxiety–like behavior in either OFT or EPM test without affecting the scratching output (fig. S2, D to H).

To test whether rostral LS is equally important for comorbid anxiety–like behaviors under other chronic itch conditions, we applied the chemogenetic methods of designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADDs) to inhibit LS in the dry skin chronic itch model created by repeated painting of AEW (acetone, diethylether, and water) onto the shaved neck to mimic the dry skin symptom (38, 41, 42). Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors carrying neuron-specific inhibitory DREADDs fused with mCherry [AAV–human Synapsin (hSyn)–hM4Di-mCherry] were microinjected bilaterally into rostral LS 10 days before AEW modeling (fig. S3, A and B). Chemogenetic inactivation of rostral LS neurons by intraperitoneal administration of clozapine N-oxide (CNO; 2 mg/kg), validated by electrophysiological recordings of action potential firings (fig. S3C), significantly increased the time spent in the open area in OFT and the time spent in the open arms in EPM when compared with saline, without affecting the AEW-induced scratching behaviors or locomotion (fig. S3, D to F). These results suggest that neuronal activity in the rostral LS is crucial for the anxiety-like behavior associated with chronic itch, independent of the animal models used.

Next, to determine whether there is any subregional specificity for the involvement of LS in chronic itch–evoked anxiety, we chemogenetically silenced the neuronal activity of caudal LS (AP, +0.00 mm; ML, ±0.40 mm; DV, −2.50 mm) before establishing the DCP model of chronic itch (fig. S4, A and B). CNO-evoked neuronal inhibition had no effect on DCP-induced anxiety–like behaviors (fig. S4, C and D). These results indicate that rostral, but not caudal, LS neurons contribute importantly to chronic itch–evoked anxiogenic comorbidities.

LS GABAergic neurons mediate chronic itch–induced anxiety–like behavior

As introduced earlier, LS comprises mostly GABAergic neurons, with a much less percentage of glutamatergic neurons (20, 21, 43). By performing RNAscope experiments, we confirmed that the vast majority of LS neurons (99.1 ± 0.2%, n = 4 mice) expressed vesicular γ-aminobutyric acid transporter (Vgat) (fig. S5, A and B). Double fluorescence in situ hybridization between c-fos and Vgat revealed that 92.7 ± 1.0% of the activated LS neurons were Vgat positive (fig. S5, C to E). To investigate the changes in LS GABAergic neuronal activity associated with chronic itch, we used whole-cell slice electrophysiology. By injecting a series of depolarizing currents, we found that LS neurons from the DCP-treated mice exhibited increased firing rates compared with neurons from control mice (Fig. 2, A to C). Moreover, the amplitude (but not frequency) of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) was significantly increased in LS neurons from the DCP-treated mice compared with controls (Fig. 2, D to F). However, we detected no significant changes in other action potential properties and resting membrane potential (fig. S6). These data indicate that LS GABAergic neurons become hyperactive in response to chronic itch, probably involving a postsynaptic mechanism.

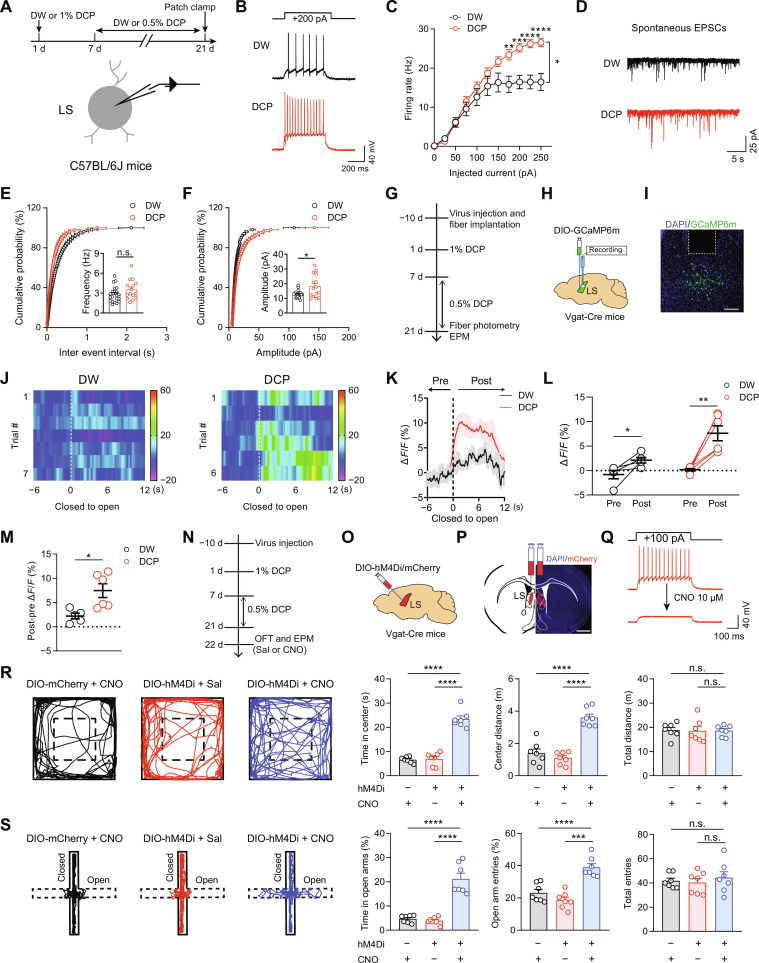

Fig. 2. LS GABAergic neurons contribute to chronic itch–induced anxiety–like behaviors.

(A) Schematics showing the experimental timeline and configuration of whole-cell patch-clamp recording of LS GABAergic neurons. (B and C) Representative traces (B) and statistical data (C) for action potential firing of LS neurons. DW, n = 13 cells from 5 mice; DCP, n = 17 cells from 6 mice. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001, two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by least significant difference (LSD) multiple comparisons test. (D to F) Representative traces (D) and quantitative analysis of sEPSC frequency (E) and amplitude (F). DW, n = 21 cells from 5 mice; DCP, n = 15 cells from 5 mice. *P < 0.05, unpaired t test. (G to I) Schematics of experimental timeline (G), viral strategy (H), and histological verification (I) for fiber photometry recordings of LS GABAergic neurons. Scale bar, 250 μm. (J) Heatmap illustration of Ca2+ signals aligned to the onset of close-to-open transition in EPM (dashed lines) for a representative mouse (left, DW; right, DCP). (K) Average Ca2+ transients (n = 5 or 6 mice per group). Thick lines indicate mean, and shaded areas indicate SEM. (L) Average ΔF/F for pre- and postperiod as shown in (K). DW, n = 5 mice; DCP, n = 6 mice. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, paired t test. (M) Analysis of post-pre ΔF/F for both DW and DCP groups. *P < 0.05, unpaired t test. (N to Q) Experimental timeline (N), viral strategy (O), histological (P), and functional validation (Q) for chemogenetic silencing of LS GABAergic neurons. Sal, saline. Scale bar, 1 mm (P). (R and S) Representative locomotion traces and quantitative analysis of the OFT (R) and EPM (S) data. n = 7 mice for each group. ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA followed by LSD multiple comparisons test. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

To further monitor the real-time activity of LS GABAergic neurons in live animals, we injected AAVs encoding Cre-inducible calmodulin-based genetically encoded GFP calcium indicators (GCaMP6m) into LS of Vgat-Cre mice and implanted an optic fiber above the injection site (Fig. 2, G to I). Using fiber photometry, we recorded the population activity of LS GABAergic neurons during DCP-induced scratching and anxiety-like behaviors. For the latter, we monitored the activities of LS GABAergic neurons in mice during exploration of the EPM, where avoidance of the open arm indicates a higher level of anxiety (44–46). In general, we found a significant increase in Ca2+ signal, indicative of neuronal activity, when the DCP-treated mouse moved from a closed arm to an open arm (Fig. 2, J to M). The elevated LS GABAergic neuronal activity could be seen from representative heatmap (Fig. 2J), averaged traces of Ca2+ signals (Fig. 2K), or quantification of the average GCaMP6m signal for all mice (Fig. 2, L and M). As a control for the fluorescent signal, no change was observed in DCP-treated mice that expressed enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) in LS GABAergic neurons (fig. S7), indicating that the changes in GCaMP6m signals were unlikely caused by motion artifacts. Notably, LS GABAergic neurons in DW-treated control mice exhibited a significantly lower increase in Ca2+ signal than the DCP-treated animals when exploring the open arms (Fig. 2, J to M).

If the increased excitability of LS GABAergic neurons mediates chronic itch–induced anxiety, then it may be possible to rescue this comorbid symptom by inhibiting the LS GABAergic neuronal activity. To test this possibility, we injected AAV–double-floxed inverse orientation (DIO)–hM4Di-mCherry or AAV-DIO-mCherry into the LS of Vgat-Cre mice (Fig. 2, N to P). Post hoc observation of mCherry fluorescence confirmed the transgene expression in the rostral LS (Fig. 2P). Recording neuronal activity in brain slices, we functionally validated the efficiency of silencing LS neurons with DREADDs by showing that bath application of CNO (10 μM) markedly suppressed the spiking activity of hM4Di-expressing LS GABAergic neurons (Fig. 2Q). Behaviorally, chemogenetic inhibition of LS GABAergic neurons with CNO rescued the excessive avoidance behavior of the DCP-treated mice expressing hM4Di-mCherry in both OFT (time spent in the center and center distance) and EPM test (open arm time and entries), while CNO had no effect on mice that expressed mCherry only (Fig. 2, R and S). As a control, chemogenetic inhibition of LS GABAergic neurons failed to affect the performance of naïve animals in either OFT or EPM test (fig. S8). Together, these results suggest that hyperexcited LS GABAergic neurons critically contribute to anxiety-like behaviors associated with chronic itch.

By contrast, fiber photometry recordings revealed no clear change in neuronal activity when aligning the Ca2+ signal to the onset of individual scratching trains (fig. S9, A to D). Behavioral results also demonstrated no significant alteration in DCP-induced scratching behaviors following chemogenetic silencing of LS GABAergic neurons (fig. S9E). In addition, chemogenetic inhibition of LS GABAergic neurons affected neither histamine-dependent nor histamine-independent acute itch (fig. S9, F and G). These findings suggest a distinct role of LS neurons in chronic itch–evoked comorbid anxiety.

Re is an upstream thalamic region conveying chronic itch signal to LS

Given the limited understanding of the LS neurocircuitry involved in chronic itch–induced anxiety, we sought to elucidate the upstream networks that drive and regulate the activity of LS GABAergic neurons. To this end, we performed retrograde labeling by microinjection of AAV-retro-hSyn-EGFP into the LS (fig. S10, A and B) and found retrogradely labeled EGFP+ cells in many upstream brain regions (fig. S10C). Quantification of the labeled upstream neurons revealed that LS received inputs from the ventral hippocampus and thalamus, particularly the Re, as well as the basolateral amygdala, prefrontal cortex (PFC), subiculum, and supramammillary nucleus (fig. S10D).

To identify which of the upstream projections might contribute to chronic itch processing, we performed c-Fos immunostaining to label DCP-activated neurons across the brain in wild-type mice. An acute restraint stress model was included as a control. Compared with naïve mice, those challenged for 2 weeks with DCP showed increased c-Fos labeling in many brain areas (fig. S10, E and F). A comparative analysis of the retrogradely labeled upstream neurons and Fos-positive cells revealed that Re exhibited selective activation under conditions of DCP-induced chronic itch (fig. S10F). In addition, Re is a midline thalamic nucleus well positioned to receive peripheral ascending sensory signals (47, 48). Therefore, we postulate that peripherally derived itch signals arrive in the Re and are then conveyed to the downstream emotional centers, such as the LS, to produce an anxiety state. In accordance with the above speculation, fiber photometry recordings demonstrated a remarkable increase in Ca2+ signal in Re excitatory neurons at the onset of the DCP-evoked scratching (Fig. 3, A to F). However, no significant activation was detected when the DCP-treated mice traveled from a closed arm to an open arm during EPM test (Fig. 3, G to I). Correspondingly, pharmacogenetic silencing of Re excitatory neurons effectively attenuated the DCP-evoked scratching but had no effect on the anxiety-like behaviors (Fig. 3, J to O).

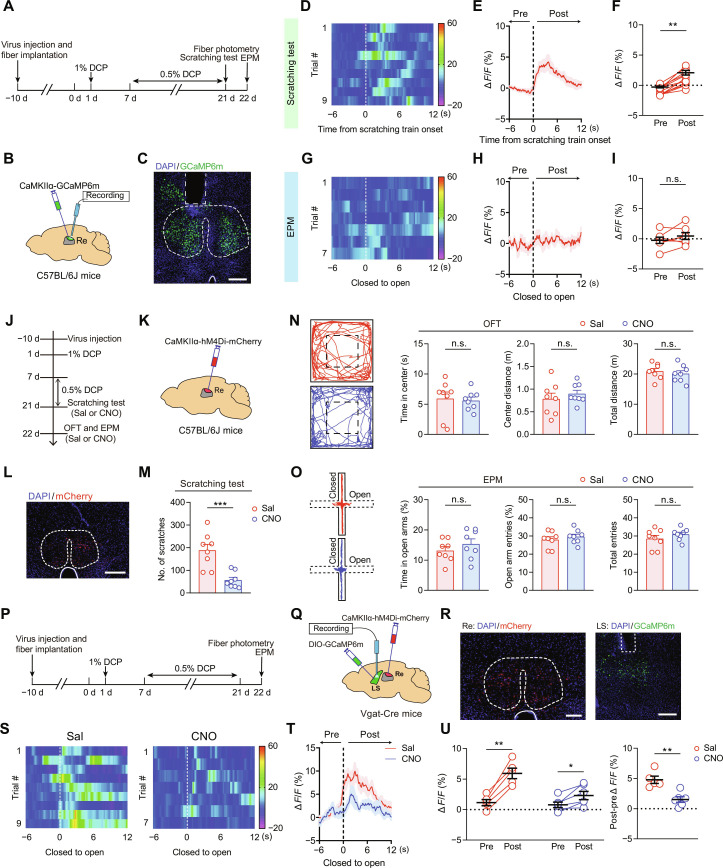

Fig. 3. Involvement of Re in chronic itch–induced scratching behaviors and LS GABAergic neuronal activation.

(A to C) Schematics of experimental timeline (A), viral strategy (B), and histological verification (C) for fiber photometry recordings of Re glutamatergic neurons. Scale bar, 250 μm. (D) Heatmap illustration of Ca2+ signals aligned to the onset of scratching train (dashed line) for a representative mouse. (E and F) Average Ca2+ signals (E) and ΔF/F for pre- and postperiod (F) relative to the onset of DCP-induced scratching train. n = 6 mice. **P < 0.01, paired t test. (G) Heatmap illustration of Ca2+ signals aligned to the onset of close-to-open transition in EPM (dashed line) for a representative mouse. (H and I) Average Ca2+ transients (H) and ΔF/F for pre- and postperiod (I) relative to the transition from closed to open arms. n = 7 mice. (J to L) Schematics of experimental timeline (J), viral strategy (K), and histological verification (L) for chemogenetic silencing of Re glutamatergic neurons. Scale bar, 200 μm. (M) Number of scratching bouts for either saline- or CNO-treated animals. n = 8 mice. ***P < 0.001, unpaired t test. (N and O) Representative locomotion traces and quantitative analysis of the OFT (N) and EPM (O) data. n = 8 mice for each group. (P to R) Experimental timeline (P), viral strategy (Q), and histological verification (R) for fiber photometry recordings of LS neurons with chemogenetic inhibition of Re neurons. Scale bars, 100 μm (left) and 250 μm (right). (S to U) Heatmaps (S), average traces (T), and quantification (U) of GCaMP6m signal. Saline, n = 5 mice; CNO, n = 6 mice. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, paired t test (U, left) or unpaired t test (U, right). Data are presented as means ± SEM.

To test the engagement of the Re → LS projection in the enhanced neuronal activity of LS GABAergic neurons under chronic itch–induced anxiety state, we injected AAV–calcium- and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIα (CaMKIIα)–hM4Di–mCherry into the Re and Cre-dependent GCaMP6m (AAV-DIO-GCaMP6m) into the LS of Vgat-Cre mice (Fig. 3, P to R). In vivo fiber photometry recordings revealed that chemogenetic silencing of Re neurons with CNO significantly attenuated the rise in Ca2+ signal when the DCP-treated mice moved from a closed arm to an open arm during EPM test (Fig. 3, S to U). These results suggest that the upstream input from the Re is important for the hyperactivation of LS neurons under chronic itch conditions.

Chronic itch induces plastic changes in the Re → LS projection

Chronic itch, unlike acute itch, may produce long-lasting synaptic plasticity–like changes in particular neural circuits, leading to sustained sensory and emotional behavioral alterations (49). To explore this possibility, we next investigated the plastic changes in synaptic transmission of the Re → LS pathway under conditions of chronic itch comorbid with anxiety. First, we characterized the nature of this Re → LS projection using virus-mediated retrograde tracing. Specifically, we injected AAV-retro-hSyn-mCherry into the LS of Vglut2-Cre::histone 2B (H2B)–GFP mice and counted the number of GFP+/mCherry+ neurons in the Re (fig. S11A). Notably, nearly all mCherry+ neurons (99.2 ± 0.9%, n = 4 mice), marking the thalamic neurons projecting to the LS, were found to colocalize with EGFP, denoting the excitatory glutamatergic neurons (fig. S11, B and C). Thus, Re neurons that innervate the LS are predominantly excitatory glutamatergic neurons.

Second, to further confirm the monosynaptic connectivity of the Re → LS projection, we injected AAV–CaMKIIα–channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2)–mCherry unilaterally into the Re and then performed whole-cell patch-clamp recordings in acute brain slices containing the LS (fig. S11D). When the axon terminals of ChR2-expressing Re neurons were activated by a single pulse of 5-ms blue light stimulation, EPSCs were detected in 32 of 37 LS GABAergic neurons. The evoked EPSCs were inhibited by bath application of the ionotropic glutamate receptor blockers 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) (10 μM) and DL-2-Amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP5) (50 μM) (fig. S11, E and F), verifying the glutamatergic nature of this synaptic transmission. In addition, the blue light–evoked EPSCs were blocked by the sodium channel blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX; 0.5 μM), which was rescued by the potassium channel blocker 4-aminopyridine (4AP; 100 μM) (fig. S11, G and H). Together, these results demonstrate that Re neurons form monosynaptic excitatory synapses with LS neurons.

Third, to address whether the Re → LS projection is activated by chronic itch, we retrogradely labeled Re neurons by injecting AAV-retro-hSyn-mCherry into the LS before subjecting the mice to DCP modeling. Then, electrophysiological recordings were performed on mCherry+ LS-projecting Re neurons in brain slices (Fig. 4A). mCherry+ Re neurons from the DCP-treated mice displayed higher firing rates than those from the DW-treated controls (Fig. 4, B and C), indicative of a significant increase in excitability of LS-projecting Re neurons during chronic itch.

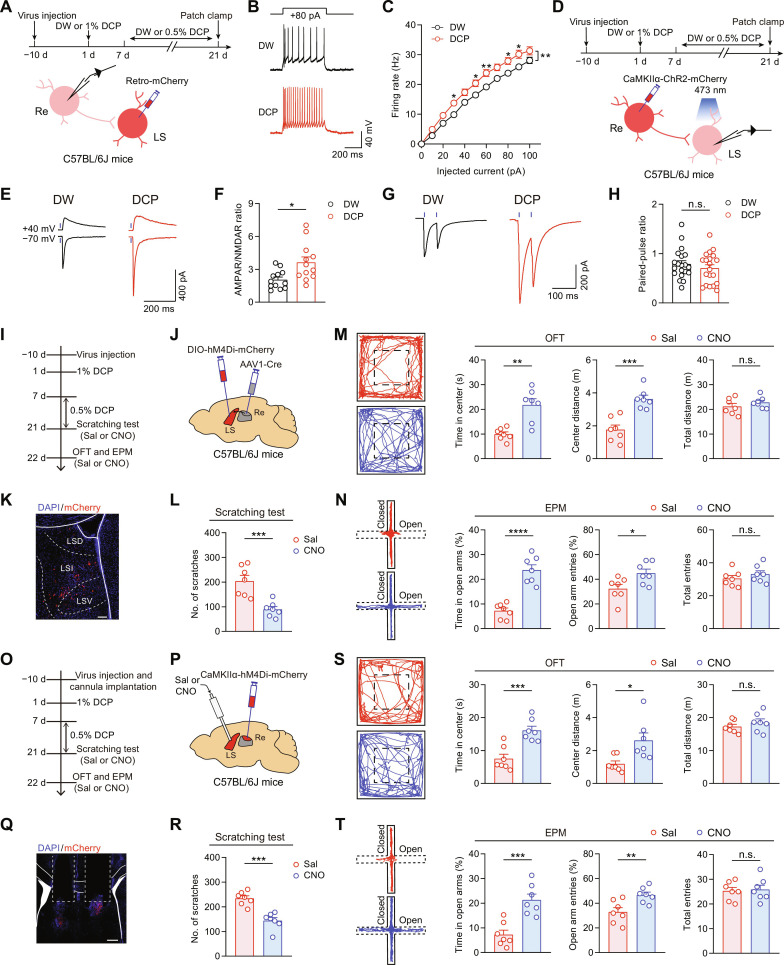

Fig. 4. The Re → LS projection mediates chronic itch–evoked anxiety–like behaviors.

(A) Schematics showing the timeline and configuration of whole-cell patch-clamp recording of LS-projecting Re neurons in DW- or DCP-treated animals. (B and C) Representative traces (B) and statistical data (C) for action potential firing. DW, n = 27 cells from 5 mice; DCP, n = 25 cells from 5 mice. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by LSD multiple comparisons test. (D) Schematics showing the timeline and configuration of electrophysiological recording of Re → LS synaptic transmission. (E and F) Sample traces (E) and summary data of AMPAR/NMDAR ratio (F). DW, n = 12 cells from 5 mice; DCP, n = 12 cells from 5 mice. *P < 0.05, unpaired t test. (G and H) Sample traces (G) and summary data (H) of paired-pulse ratio (PPR) of light-evoked EPSCs. DW, n = 20 cells from 7 mice; DCP, n = 20 cells from 6 mice. (I to K) Schematics of experimental timeline (I), viral strategy (J), and histological verification (K) for chemogenetic silencing of Re-innervated LS neurons. Scale bar, 100 μm. LSD, lateral septum, dorsal part; LSI, lateral septum, intermediate part; LSV, lateral septum, ventral part. (L) Number of scratching bouts for either saline- or CNO-treated animals. n = 7 mice. ***P < 0.001, unpaired t test. (M and N) Representative locomotion traces and quantitative analysis of the OFT (M) and EPM (N) data. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. (O to Q) Schematics of experimental timeline (O), viral strategy (P), and histological verification (Q) for chemogenetic inhibition of Re → LS projection. Scale bar, 250 μm. (R) Number of scratching bouts. n = 7 mice. ***P < 0.001, unpaired t test. (S and T) Representative locomotion traces and quantitative analysis of the OFT (S) and EPM (T) data. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, unpaired t test. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Fourth, to assess any changes in synaptic transmission of the Re → LS pathway, we injected AAV-CaMKIIɑ-ChR2-mCherry into the Re before subjecting the animals to DCP modeling. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed on Re-innervated LS neurons in brain slices (Fig. 4D). By holding the cell at either +40 or −70 mV, we assessed light-evoked EPSCs mediated by N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionicacid receptor (AMPAR), respectively, as described previously (50, 51). The AMPAR/NMDAR ratio, an indicator of the strength of excitatory synaptic transmission (52, 53), was found to be significantly increased in LS neurons from the DCP-treated mice relative to the DW-treated controls (Fig. 4, E and F), suggesting an enhanced synaptic efficacy of the Re → LS projection under chronic itch conditions. However, the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) between the second and first EPSCs evoked by a pair of blue light pulses (5 ms, 50-ms interval) showed no significant alteration (Fig. 4, G and H). Collectively, these data demonstrate that chronic itch enhances the transmission efficacy of the Re → LS synapses mainly through postsynaptic mechanisms.

Inhibiting the Re → LS projection alleviates chronic itch–induced anxiety–like behaviors

In view of our finding that DCP-evoked chronic itch triggers a clear activation and plastic change of the Re → LS pathway, we next examined the influence of inhibiting this circuit on chronic itch–induced anxiety–like behaviors. A dual-virus intersectional strategy was adopted to express inhibitory DREADD into LS postsynaptic neurons innervated by the Re. Specifically, we injected the monosynaptic anterograde transport virus AAV1-hSyn-Cre into the Re and then infected the LS neurons with AAV-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry (Fig. 4, I to K). The LS neurons that received direct innervations from Re were inhibited via intraperitoneal injection of CNO 30 min before the behavioral test at the 21st day after initiation of the DCP modeling. The results showed that chemogenetic inhibition of postsynaptic LS neurons innervated by the Re not only significantly decreased the DCP-induced scratching behaviors but also reversed the comorbid anxiety–like behaviors without affecting the animals’locomotion (Fig. 4, L to N).

To further confirm the contribution of the Re → LS pathway to chronic itch–associated anxiety, we delivered AAV-CaMKIIα-hM4Di-mCherry into the Re and implanted a cannula in the LS (Fig. 4, O to Q). Chemogenetic inhibition of the Re projection terminals in the LS through local infusion of CNO (0.1 mg/ml, 0.3 μl per side) significantly reversed the DCP-induced anxiety–like behaviors in both OFT and EPM test (Fig. 4, S and T). In parallel, this chemogenetic manipulation also substantially reduced the number of scratching bouts in the DCP-treated mice (Fig. 4R), supporting a critical involvement of the Re → LS projection in both chronic itch and the comorbid anxiety.

Re → LS circuit does not contribute to restraint stress–induced anxiety–like behaviors

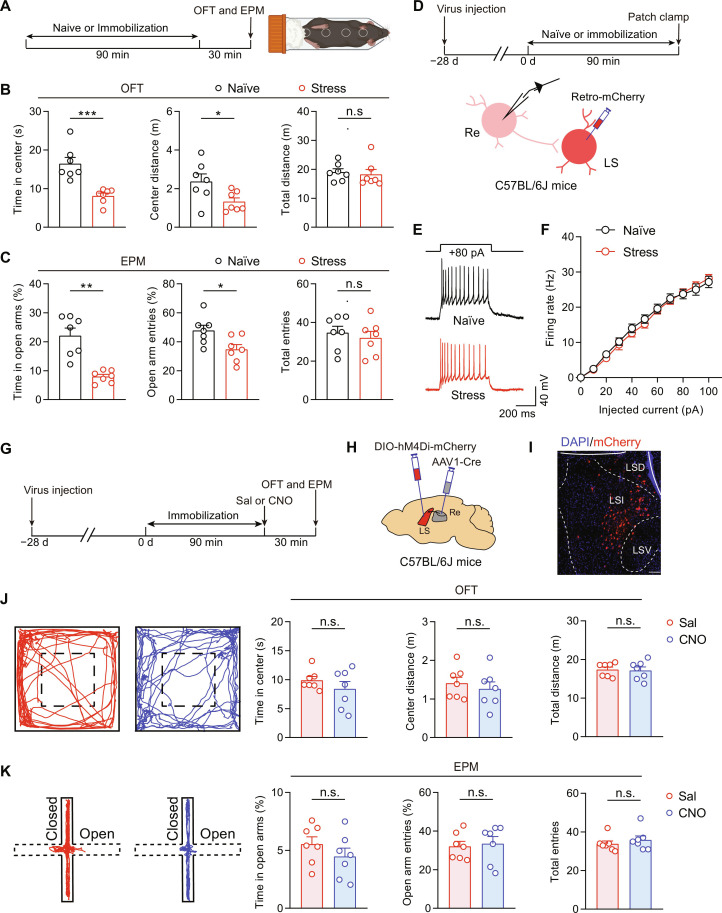

To distinguish whether the Re → LS pathway is generally involved in anxiety behaviors or specific for the chronic itch–induced avoidance, we used a different animal model of anxiety induced by acute restraint stress following the protocol as previously described (32, 54). At 30 min after being subjected to a 90-min restraint stress, the mice reliably exhibited anxiety-like behaviors as assessed by both OFT and EPM test (Fig. 5, A to C). However, contrary to the chronic itch model, the excitability of LS-projecting Re neurons showed no change in the restraint stress–treated mice compared with control mice (Fig. 5, D to F). Moreover, chemogenetic silencing of Re → LS projection, using the same viral strategy as in Fig. 4J, failed to abolish the acute restraint stress–induced anxiety–like behaviors (Fig. 5, G to K).

Fig. 5. The Re → LS circuit is not involved in acute restraint stress–induced anxiety–like behaviors.

(A) Schematic of timeline for behavioral experiments on mice subjected to acute restraint stress. (B and C) Performance of naïve mice and those subject to restraint stress in OFT (B) or EPM (C). n = 7 mice for each group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, unpaired t test. (D) Schematics showing timeline and configuration of electrophysiological recording on LS-projecting Re neurons in naïve and restraint stress–treated animals. (E and F) Sample traces (E) and statistical data (F) for action potential firing. Naïve, n = 25 cells from 5 mice; stress, n = 31 cells from 4 mice. (G to I) Schematics of experimental timeline (G), viral strategy (H), and histological verification (I) for chemogenetic silencing of Re-innervated LS neurons. Scale bar, 100 μm. (J and K) Representative locomotion traces and quantitative analysis of the OFT (J) and EPM (K) data. n = 7 mice for each group. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Considering the temporal disparity between acute restraint stress (90 min) and DCP-evoked chronic itch (2-week challenge), we next adopted a prolonged stress protocol (90 min of restraint/day, 14 days) to see whether the Re → LS circuit has any role in chronic restraint stress–induced anxiety. We found that the repeated restraint stress over 2 weeks did not enhance the activity of the LS-projecting Re neurons, as illustrated by the whole-cell patch-clamp recordings of the action potential firings (fig. S12, A to C). Moreover, chemogenetic silencing of the Re → LS circuit failed to affect the chronic restraint stress–induced anxiety–like behaviors in either OFT or EPM test (fig. S12, D to G). These results support the assertion that the Re → LS projection selectively mediates chronic itch–induced comorbid anxiety, without any significant role in anxiety triggered by either acute or chronic restraint stress.

Given the significant innervation of LS by inputs from the PFC (fig. S10), along with the previous evidence implicating the role of this circuit in controlling anxiety (34), we also tested the possible engagement of the PFC → LS pathway in chronic itch–induced comorbid anxiety. The AAV-CaMKIIα-hM4Di-mCherry was injected into the PFC, and a guide cannula for drug administration was implanted into the LS. The DCP model was established after the animals recovered from the surgery. CNO was microinjected into the LS after 2 weeks of the DCP challenging (fig. S13, A and B). Bilateral chemogenetic silencing of the PFC → LS projection had no effect on DCP-induced repetitive scratching and anxiety-like behaviors (fig. S13, C to E). In contrast, chemogenetic inhibition of the PFC-innervated LS neurons resulted in a significant blockade of acute restraint stress–induced anxiogenic avoidance (fig. S14), in line with the strong activation of PFC by stress (fig. S10). These results suggest a circuit-specific mechanistic distinction for different forms of anxiety.

The LS → LH pathway contributes to chronic itch–induced anxiety–like behaviors

To further explore the circuit mechanisms underlying the LS involvement in chronic itch–induced anxiety, we mapped the downstream targets of LS GABAergic neurons. To this end, we injected AAV-DIO-mCherry into the LS of Vgat-Cre mice and imaged mCherry+ axon terminals throughout the brain (fig. S15, A and B). The identified regions encompassed many areas, such as bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, LH, medial preoptic area, medial septum, supramammillary nucleus, periaqueductal gray, and ventral tegmental area (fig. S15, C and D). Among them, LH is known to be essential for orchestrating the complex repertoire of adaptive motivated behaviors to environmental challenge (35, 36). Moreover, emerging evidence has demonstrated the modulatory role of LH in anxiety (55–57). Therefore, we focused on the LS → LH projection and examined its potential engagement in chronic itch–induced anxiety.

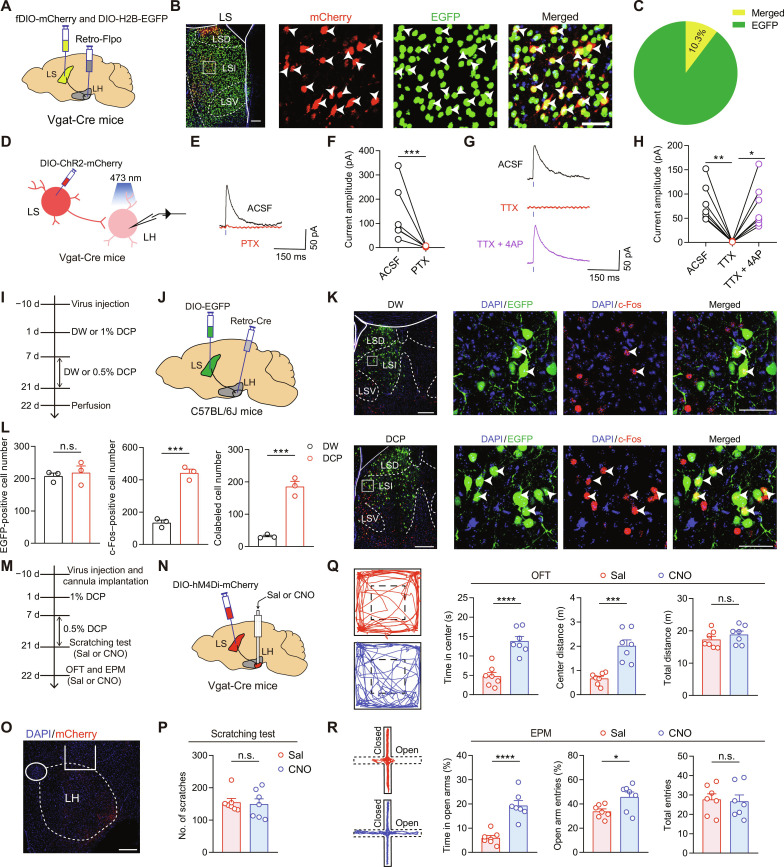

First, we anatomically characterize this projection through retrograde tracing of the LH-projecting LS neurons. We injected AAV-retro–Flippase (Flpo) into the LH together with AAV-fDIO-mCherry and AAV-DIO-H2B-EGFP into the LS of Vgat-Cre mice (Fig. 6A). In this way, LS GABAergic neurons projecting to LH would be both mCherry- and EGFP-positive (merged), while all LS GABAergic neurons would be labeled with EGFP (Fig. 6B). We found that 10.3 ± 1.3% of LS GABAergic neurons project to the LH (Fig. 6C). Next, we used ChR2-assisted circuit mapping to validate the functional connectivity of this pathway. AAV-DIO-ChR2-mCherry was injected into the LS of Vgat-Cre mice, and whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed 4 weeks later on LH neurons in brain slices (Fig. 6D). Brief light stimulations of ChR2-expressing LS GABAergic terminals elicited inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) in 73% (46 of 63) of postsynaptic LH neurons. The optically evoked IPSCs were eliminated by the γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor antagonist picrotoxin (PTX) (100 μM; Fig. 6, E and F). Furthermore, the light-evoked IPSCs were completely blocked by TTX but rescued by 4AP, suggesting that LS GABAergic neurons form monosynaptic inhibitory synapses with the LH neurons (Fig. 6, G and H).

Fig. 6. The LS → LH projection mediates chronic itch–evoked anxiety–like behaviors.

(A) Schematic showing the viral strategy for retrograde tracing of LS → LH projection. (B) Representative images for EGFP (GABAergic neurons), mCherry (LH-projecting LS neurons), and merge (yellow and white arrowheads). Scale bars, 150 μm (left) and 50 μm (right). (C) Pie chart showing the percentage of EGFP+/mCherry+ cells among all EGFP+ cells. n = 5 mice. (D) Schematic showing the configuration for electrophysiological recording of the LS → LH projection. (E and F) Sample traces (E) and statistical data (F) of blue light–induced IPSCs in LH neurons in the absence and presence of PTX. n = 6 cells from 3 mice. ***P < 0.001, ratio paired t test. (G and H) Sample traces (G) and statistical data (H) of blue light–induced IPSCs in the absence and presence of TTX or TTX plus 4AP. n = 7 cells from 3 mice. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by LSD multiple comparisons test. (I and J) Schematics of experimental timeline (I) and viral strategy (J) for examining the activation of LS → LH circuit by chronic itch. (K) Representative images for EGFP, c-Fos, and merge. Scale bars, 250 μm (left) and 50 μm (right). (L) Quantitative analysis of numbers of EGFP+, c-Fos+, and EGFP+/c-Fos+ cells. n = 3 mice. ***P < 0.001, unpaired t test. (M to O) Experimental timeline (M), viral strategy (N), and histological verification (O) for chemogenetic inhibition of LS → LH projection. Scale bar, 250 μm. (P) Number of scratching bouts. n = 7 mice. (Q and R) Representative locomotion traces and quantitative analysis of the OFT (Q) and EPM (R) data. n = 7 mice for each group. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Then, to explore the contribution of the LS → LH projection to chronic itch–induced anxiety–like behavior, we examined the activation of this pathway with circuit-specific c-Fos staining (Fig. 6, I and J). LH-projecting LS neurons were labeled by injecting AAV-retro-hSyn-Cre into the LH and AAV-DIO-EGFP into the LS. We found a robust increase in the number of c-fos+/EGFP+ cells in the DCP-treated mice compared with the DW-treated controls (Fig. 6, K and L), implicating a strong activation of the LS → LH projection by chronic itch. In line with these data, chemogenetic inhibition the LS → LH projection (Fig. 6, M to O) significantly alleviated DCP-induced anxiety–like behaviors, as shown by the increased time spent and distance traveled at the center area in OFT and the increased time spent and number of entries into the open arms in EPM (Fig. 6, Q and R). No alterations in DCP-induced scratching bouts were detected following the LS → LH inhibition (Fig. 6P), demonstrating the selective role of this pathway in chronic itch–induced anxiety–like behaviors but not scratching behaviors.

To precisely characterize this circuit, we injected the anterograde monosynaptic virus, namely, AAV1-hSyn-Flpo, into the LS along with AAV-fDIO-mCherry into the LH of Vgat-Cre::H2B-GFP mice (Fig. 7A). After 3 weeks, we observed many mCherry-expressing neurons in the LH, a large fraction of which were colocalized with GFP (59.3% ± 5.8%, n = 5 mice), indicating widespread innervation of the LS into LH GABAergic neurons (Fig. 7, B and C). To further confirm this notion, we injected Cre-dependent ChR2-mCherry into the LS of Vgat-Cre::H2B-GFP mice. Three or 4 weeks later, we performed patch-clamp recording on putative GABAergic (GFP+ and therefore Vgat+) and non-GABAergic (GFP− and thus Vgat−) cells in the LH from the same slice while delivering brief 470-nm light pulses to activate LS-derived GABAergic terminals (Fig. 7D). Stimulating the GABAergic input from the LS evoked IPSCs in 86.2% (25 of 29) Vgat+ cells and 47.8% (11 of 23) Vgat− cells in the LH, although the IPSC amplitude was not significantly different between Vgat+ and Vgat− neurons (Fig. 7, E to G). Together, these findings confirm that LS GABAergic neurons send afferents that mainly synapse onto GABAergic neurons in the LH.

Fig. 7. LS projects to LH GABAergic neurons to mediate chronic itch–induced anxiety–like behaviors.

(A) Schematic showing the viral strategy for identifying the predominant LH cell type that receives innervations from LS. (B) Representative images of immunofluorescent signals for GFP (GABAergic neurons), mCherry (LS-innervated LH cells), and merge (yellow and white arrowheads). Scale bars, 250 μm (left) and 50 μm (right). (C) Pie chart showing the percentage of GFP+/mCherry+ cells among all mCherry+ cells in the LH. n = 5 mice. (D) Schematic showing the configuration for electrophysiological identification of the postsynaptic LH cell types receiving innervation from LS GABAergic neurons. (E and F) Sample traces (E) and summary graph (F) showing percentage of LH Vgat+ (GFP+) and Vgat− (GFP−) neurons that responded to light stimulation with IPSCs. (G) Statistical data of the amplitude of optogenetically-evoked IPSCs (oIPSCs) recorded in Vgat+ (25 cells from seven mice) and Vgat− (11 cells from seven mice) LH neurons. (H to K) Schematics of experimental timeline (H), viral strategy (I), histological (J), and functional verification (K) for chemogenetic activation of LS-innervated LH GABAergic neurons. Scale bar, 200 μm (J). (L) Number of scratching bouts. n = 7 mice; t12 = 0.1814, P = 0.859, unpaired t test. (M and N) Representative locomotion traces and quantitative analysis of the OFT (M) and EPM (N) data. n = 7 mice for each group. ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Next, we tested the effect of selectively manipulating the LS-innervated LH GABAergic neurons on DCP-evoked comorbid anxiety–like behaviors. Considering the inhibitory nature of this pathway, we injected AAV1-DIO-Flpo into the LS in combination with AAV-fDIO-hM3Dq-mCherry into the LH of Vgat-Cre mice (Fig. 7, H to J). This strategy allows selective activation of LH GABAergic neurons receiving inhibitory inputs from the LS (Fig. 7K). Consistent with the critical role of this pathway, chemogenetic activation of the LH GABAergic neurons that received projections from the LS ameliorated DCP-induced anxiety–like behaviors, as assessed by either OFT or EPM test (Fig. 7, M and N), without affecting the scratching bout numbers (Fig. 7L). These results suggest that LS neurons mediate chronic itch–evoked comorbid anxiety through sending inhibitory projections to GABAergic neurons in the LH.

The Re → LS → LH pathway mediates chronic itch–induced anxiety–like behaviors

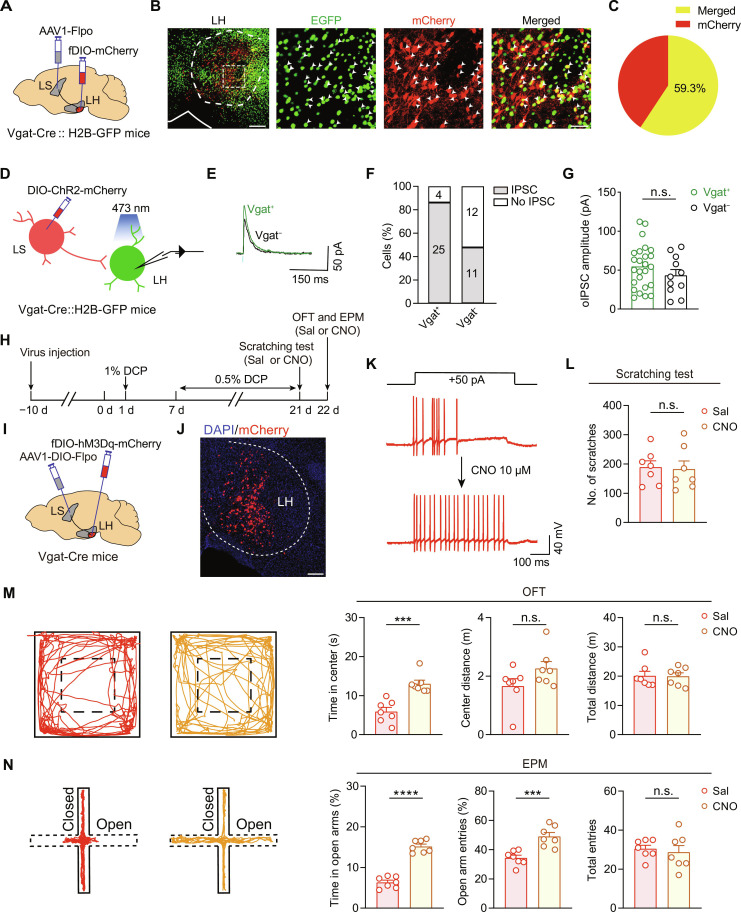

To characterize the connectivity of the Re → LS → LH circuit, we injected the anterograde virus AAV1-hSyn-Cre into the Re and the retrograde virus AAV-retro-Flpo into the LH, together with AAV-fDIO-mCherry and AAV-DIO-EGFP into the LS of C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 8A). Thus, LS GABAergic neurons receiving inputs from Re neurons would be labeled with EGFP, while LS neurons projecting to LH would be labeled with mCherry (Fig. 8B). We found that 42.7 ± 6.8% of Re-innervated LS GABAergic neurons project to LH (Fig. 8C). Then, to functionally validate this disynaptic connection, we injected CTB555 into the LH to label LH-projecting LS neurons and AAV–CaMKIIɑ–ChR2–enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) into the Re of Vgat-Cre::H2B-GFP mice (Fig. 8D). This combinatorial strategy allows the LH-projecting LS GABAergic neurons to be colabeled with CTB555 and GFP, showing yellow color in brain slices to be selected for whole-cell patch-clamp recordings. Blue light stimulation of the ChR2-expressing Re terminals in the LS elicited a CNQX-sensitive EPSC in CTB555+/H2B-GFP+ neurons in the LS (Fig. 8E), demonstrating a direct functional connectivity of the Re → LS → LH circuit.

Fig. 8. Connectivity and function of the Re → LS → LH pathway.

(A) Schematic showing the combinational viral strategy for characterizing the connectivity of the Re → LS → LH circuit. (B) Representative images of immunofluorescent signals for EGFP (Re-innervated LS neurons), mCherry (LH-projecting LS cells), DAPI, and merge (yellow and white arrowheads). Scale bars, 150 μm (left) and 50 μm (right). (C) Pie chart showing the percentage of EGFP+/mCherry+ cells among all EGFP+ cells in the LS. n = 5 mice. (D) Schematic of viral and CTB555 injection and whole-cell recording configuration in the LS slices from Vgat-Cre:H2B-GFP mice. (E) Representative EPSC traces, in the absence and presence CNQX, evoked in CTB555+/GFP+ neurons by blue light stimulation of Re projection terminals. (F to H) Schematics of experimental timeline (F), viral strategy (G), and histological verification (H) for chemogenetic inhibition of LH-projecting LS neurons that receive innervation from Re. Scale bar, 100 μm. (I) Number of scratching bouts. n = 7 mice; t12 = 0.4991, P = 0.6268, unpaired t test. (J and K) Representative locomotion traces and quantitative analysis of the OFT (J) and EPM (K) data. n = 7 mice for each group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

To determine whether this pathway modulates chronic itch–induced anxiety–like behaviors, we exclusively expressed hM4Di in LS neurons receiving input from Re and sending output to LH, using an intersectional strategy combining AAV-mediated anterograde transsynaptic tagging and retrograde infection from axonal terminals (58). Specifically, we injected the anterograde transsynaptic AAV1-hSyn-Flpo into the Re, retrograde AAV-retro-hSyn-Cre into the LH, and Cre- and Flpo-dependent AAV-Con-Fon-hM4Di-EGFP in the LS (Fig. 8, F and G). This allows selective expression of hM4Di-EGFP only in LH-projecting LS neurons that are also innervated by the Re (Fig. 8H). In these animals, intraperitoneal administration of CNO had no effect on DCP-induced scratching but significantly attenuated DCP-induced behavioral avoidance in both OFT and EPM test (Fig. 8, I to K), supporting the selective contribution of the Re → LS → LH pathway to chronic itch–induced anxiogenic comorbidity.

DISCUSSION

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that anxiety is highly prevalent in patients suffering from chronic itch. Chronic itch and anxiety not only are common comorbidities but also contribute to each other’s development and aggravation (4). Thus, uncovering the neuronal circuitry mediating chronic itch–induced anxiety may provide opportunities for development of safer therapies for severe itch and comorbid disorders. In this study, we selectively monitored and manipulated the activity of GABAergic neurons in the LS to reveal their pivotal role in chronic itch–evoked anxiety. Then, we determined that the excitatory projection from Re to LS represents the neural circuit that undergoes synaptic adaptation to mediate the development of anxiety states in response to chronic itch. Moreover, we identified the LH as a critical downstream target area responsible for the LS-mediated chronic itch–induced anxiety. Together, our data offer important insights into the neural circuit substrate of anxiety induced by chronic itch (fig. S16).

Chronic itch and anxiety symptoms are frequently encountered clinically, which exacerbate each other, creating a vicious circle that not only causes much suffering to the patients but is also difficult to treat (4, 5, 8, 59). However, little is known about the neural circuit mechanisms underlying the comorbid anxiety symptoms in the context of chronic itch. In the current study, we established the behavioral paradigm for assessing chronic itch–induced anxiety (Fig. 1) and provided multiple pieces of evidence to show the crucial importance of LS neurons, specifically the GABAergic neurons, in the itch-anxiety comorbidity. First, c-Fos immunostaining, in situ hybridization, and whole-cell patch-clamp recording demonstrated a significant increase in the activity of LS GABAergic neurons by DCP-induced chronic itch (Fig. 2, A to F, and figs. S2 and S5). Second, cell type–specific fiber photometry revealed an elevated neuronal activity of LS neurons when the DCP-challenged animals moved from a closed arm into an open arm in EPM (Fig. 2, G to M), a trait state of high anxiety levels. Third, chemogenetic inhibition of LS GABAergic neurons alleviated DCP-evoked anxiety–like behaviors (Fig. 2, N to S). This rescuing effect may be generalized to other animal models of chronic itch with comorbid anxiety, since chemogenetic inhibition of rostral LS neurons also ameliorated the anxiety-like behaviors associated with the dry skin model (fig. S3). Fourth, the contribution of LS to chronic itch–induced anxiety is subregion dependent, with the rostral LS playing a more important role than the caudal LS (fig. S4). Collectively, these results demonstrate that LS is a key node of the circuitry involved in linking chronic itch to anxiety processing.

Notably, previous literature has documented the involvement of LS in other forms of anxiety, such as baseline anxiety (28, 33, 34), restraint or social stress-induced anxiety (32, 60), and pain-related anxiety (61). It would be interesting in future studies to sort out whether distinct subgroups of LS neurons with heterogeneous molecular identity or projection profiles are involved in different forms of anxiety. The LS predominantly comprises GABAergic neurons, which can be divided into many subgroups expressing characteristic molecular markers (20, 21, 62, 63). It would be necessary to further determine which subtype of the LS GABAergic neurons is more relevant to chronic itch–induced anxiety.

To search for the upstream circuit responsible for the LS regulation of chronic itch–induced anxiety, we combined virus-mediated anatomical tracing, ChR2-assisted circuit mapping, pathway-specific chemogenetic manipulations, and anxiety-like behavioral tests. A monosynaptic and excitatory circuit between Re glutamatergic neurons and LS GABAergic neurons was identified (figs. S10 and S11), which was strongly activated under conditions of chronic itch comorbid with anxiety (Fig. 4, A to C). We further demonstrated that the DCP treatment resulted in an augmentation of glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the Re → LS pathway, as shown by the enhanced AMPAR/NMDAR ratio (Fig. 4, D to H). These synaptic adaptations along the Re → LS pathway may constitute an important plastic mechanism mediating the chronicity of itch and the resultant comorbid anxiety–like state. In line with this prediction, chemogenetic inhibition of LS-projecting Re neurons or the Re → LS projection terminals markedly alleviated DCP-evoked anxiogenic phenotypes in OFT and EPM assays (Fig. 4, I to T). Silencing the Re neurons or Re → LS projection also clearly decreased DCP-induced scratching bout numbers (Figs. 3M and 4, L and R), while nonspecifically inhibiting all LS neurons failed to affect the scratching response (fig. S9). Therefore, Re neurons serve a critical role in transmitting the chronic pruriceptive signal into the LS, a well-recognized hub for emotional control, to produce the anxiety-like phenotype. Supporting this interpretation, chemogenetic blockade of Re activity attenuated responses of LS GABAergic neurons to chronic itch–related anxiogenic stimulation (Fig. 3, S to U). Future work is required to further dissect the exact route through which the spinally ascending itch signals are conveyed either directly or indirectly into the Re. Our data on retrograde tracing of Re neurons suggest the possibility of a parabrachial nucleus → Re connection, with the functional connectivity and exact role of this circuit still requiring further examination. In addition, the potential involvement of other upstream regions in linking itch and anxiety could not be fully ruled out, although the PFC → LS pathway was excluded in the present study (fig. S13). Amygdala was previously demonstrated to be important in itch-evoked anxiety (18), and our present data revealed a moderate innervation from basolateral amygdala to the LS. The possible involvement of this pathway in chronic itch–induced anxiety remains an interesting question to be clarified in future studies.

The LH is a critical neuroanatomical hub for controlling motivated behaviors and emotional states (36, 55, 56, 64–66). Using viral tracing and whole-cell recording, we found that LS GABAergic neurons project densely to the LH, particularly the GABAergic neurons in this area (Figs. 6, A to H, and 7, A to G; and fig. S15). This means that GABAergic input from the LS likely suppresses inhibitory neurons in the LH, thus resulting in disinhibition of LH glutamatergic neurons, a notion that agrees with previous publications investigating this connection (67, 68). Previous work has revealed a critical role of LH glutamatergic neurons in mediating the aversion and/or anxiety state (55–57, 69). Consistently, chemogenetic inhibition of the LS → LH projection significantly alleviated DCP-induced anxiety–like behaviors (Figs. 6, M to R, and 7, H to N) without affecting the scratching response (Figs. 6P and 7L). These results suggest that LS promotes the anxiety state under chronic itch conditions through sending projections to the LH, although potential involvement of other downstream targets cannot be fully excluded. However, the LS → LH circuit has no effect on the sensory component of chronic itch. It was also recently reported that the LS → LH GABAergic projection plays an important role in the development of pain and anxiety comorbidities (61). Therefore, we suspect that context-specific regulation of the LS → LH circuit may be one of the common mechanisms underlying development of treatment-resistant anxiety, including the comorbid anxiogenic symptoms associated with both chronic pain and chronic itch.

Pathological anxiety could be induced by several etiologies. In this study, we found that chemogenetic silencing of the Re → LS → LH circuit had no effect on restraint stress–induced anxiety–like behaviors (Fig. 5 and fig. S12), although DCP-evoked anxiogenic behaviors were markedly attenuated (Figs. 4 and 8). By contrast, inhibition of the PFC → LS pathway markedly attenuated restraint stress–evoked anxiety without affecting chronic itch–related anxiety (figs. S13 and S14). These findings raise the interesting possibility that different etiologies of anxiety, such as chronic itch and restraint stress, likely engage distinct LS circuits. This contention agrees with the recently proposed theory explaining the functional heterogeneity of LS based on its diverse input and output connections (23, 70).

In conclusion, our findings reveal the essential role of LS GABAergic neurons in the regulation of chronic itch–induced comorbid anxiety and establish the importance of the Re → LS → LH circuit in controlling this process. With a high prevalence of anxiety symptoms seen in patients with chronic itch, our results provide a framework for understanding the circuit mechanisms underlying this devastating comorbidity. Since silencing the Re → LS → LH circuit significantly relieved chronic itch–evoked anxiety–like state, the present work also sheds light on developing promising therapies for these debilitating conditions through targeting the abnormal circuits with neuromodulatory approaches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animal studies and experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees at Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (policy number: DLAS-MP-ANIM, 01-05). Adult (8 to 12 weeks old) male C57BL/6J mice (Slac Laboratory Animal, Shanghai), Vgat-Cre transgenic mice [Slc32a1tm2(Cre)Lowl/J, RRID: 028862, the Jackson Laboratory, ME, USA], Vglut2-Cre transgenic mice [Slc17a6tm2(cre)Lowl/J, RRID: 016963, the Jackson Laboratory] and H2B-GFP mice (Rosa26-loxp-STOP-loxp-H2B-GFP, gift of M. He, Fudan University) were used in this study. All mice were group housed (four to five per cage) in specific pathogen–free laboratory animal facilities under standard conditions with temperatures of 21° to 23°C, 40 to 70% humidity, and a 12-hour light/dark cycle (light on from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.). Rodent chow and water were provided ad libitum. All behavioral experiments were performed during the light phase. All mice were handled and acclimatized to the test room for 3 to 5 days before any behavioral assays. Efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals used.

Viral vectors and stereotaxic surgery

The following viruses were purchased from BrainVTA Co. Ltd. (Wuhan, China): AAV-hSyn-hM4Di-mCherry [serotype, 2/9; titer, 5.16 × 1012 vector genomes (vg)/ml], AAV-CaMKIIα-hM4Di-mCherry (serotype, 2/9; titer, 5.33 × 1012 vg/ml), AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry (serotype, 2/9; titer, 5.25 × 1012 vg/ml), AAV-hSyn-DIO-mCherry (serotype, 2/9; titer, 5.27 × 1012 vg/ml), AAV-hSyn-DIO-EGFP (serotype, 2/9; titer, 5.04 × 1012 vg/ml), AAV-CaMKIIα-ChR2-mCherry (serotype, 2/9; titer, 4.58 × 1012 vg/ml), AAV-CaMKIIα-ChR2-EYFP (serotype, 2/9; titer, 5.32 × 1012 vg/ml), AAV-EF1α-DIO-ChR2-mCherry (serotype, 2/9; titer, 4.98 × 1012 vg/ml), AAV-retro-hSyn-EGFP (serotype, 2/retro; titer, 5.24 × 1012 vg/ml), AAV-retro-hSyn-mCherry (serotype, 2/retro; titer, 5.32 × 1012 vg/ml), AAV-retro-hSyn-Cre (serotype, 2/retro; titer, 5.13 × 1012 vg/ml), AAV-hSyn-Cre (serotype, 2/1; titer, 1.11 × 1013 vg/ml), AAV-hSyn-Flpo (serotype, 2/1; titer, 1.03 × 1013 vg/ml), AAV-EF1ɑ-DIO-Flpo (serotype, 2/1; titer, 1.03× 1013 vg/ml), AAV2/9-EF1α-fDIO-mCherry (serotype, 2/9; titer, 5.54 × 1012 vg/ml), AAV-hSyn-fDIO-hM3Dq-mCherry (serotype, 2/9; titer, 5.53 × 1012 vg/ml), and AAV-Con-Fon-hM4Di-EGFP (serotype, 2/9; titer, 5.94 × 1012 vg/ml). AAV2-retro-hSyn-Flpo (serotype, 2; titer, 1.51 × 1013 vg/ml) was purchased from Obio Technology (Shanghai, China). AAV2/9-hSyn-FLEX-H2B-EGFP (serotype, 2/9; titer, 1.16 × 1013 vg/ml), AAV-hSyn-DIO-GCaMP6m (serotype, 2/9; titer, 1.04 × 1013 vg/ml), and AAV-CaMKII-GCaMP6m (serotype, 2/9; titer, 2.06 × 1013 vg/ml) were produced by Shanghai Taitool Bioscience Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All viral vectors were stored in small aliquots at −80°C until use.

Stereotaxic surgeries were performed as previously described (39, 71). Mice were anesthetized with 1% sodium pentobarbital [100 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)] and placed on the stereotaxic frame (RWD Life Science Co. Ltd., Shenzhen, China) with a heating pad to maintain the body temperature. Ophthalmic ointment was administered to prevent drying of the eyes. After making an incision to the midline of the scalp, small bilateral craniotomies were performed under a surgical microscope using a microdrill. Glass pipettes (tip diameter, 10 to 20 μm) were made with a P-97 micropipette puller (Sutter glass pipettes, Sutter Instrument Company, USA) for viral microinjections. Viral injections were targeted into the following coordinates: Re (AP, −0.80 mm; ML, 0.00 mm; DV, −4.50 mm), LS (rostral: AP, 0.70 mm; ML, ±0.40 mm; DV, −3.20 mm; caudal: AP -0.00 mm; ML, ±0.40 mm; DV, −2.50 mm), LH (AP, −0.8 mm; ML, ±1.30 mm; DV, −5.00 mm), and PFC (AP, 1.90 mm; ML, ±0.30 mm; DV, −2.50 mm). For each side, 200 to 300 nl of virus was injected at a rate of 50 nl/min using a hydraulic pump (RWD Apparatus). After the injection, the glass pipette was left in place for 10 min to allow the injectant to diffuse adequately. The animals were allowed to recover from anesthesia on a heating blanket. Experiments were performed 4 to 6 weeks after virus injection. Optical fiber implants [200 μm in diameter, numerical aperture (NA) = 0.37] (Inper, Hangzhou, China) were placed 200 μm above the injection site for fiber photometry and were fixed to the skull with dental cement. Viral injection sites and the position of fiber implants in each mouse were confirmed histologically after the termination of the experiments. Only those animals with correct virus expression or fiber implantation were included for further analysis.

DCP-induced chronic itch

A contact dermatitis model of chronic itch was developed by applying DCP to the neck skin as described previously (38, 39, 72, 73). The back of the mouse was shaved and painted with 0.2 ml of DCP (1% dissolved in acetone; Sigma-Aldrich). Seven days after the sensitization, 0.2 ml of 0.5% DCP was repeatedly painted on the neck skin once a day for 2 weeks. To determine the time course of DCP-evoked anxiety–like behaviors, we also tried to paint DCP for 1 week. Anxiety-like behaviors were examined the next day after the last DCP treatment. For some animals, DCP was painted for 2 weeks, but the scratching and anxiety-like behaviors were tested 1 week after the end of DCP painting. Scratching behaviors were video-recorded for 60 min at the indicated time points. The numbers of scratching bouts were counted blindly. A scratch was defined as lifting of the hind paw toward the injection site and placing it back to the ground or to the mouth.

Dry skin-induced chronic itch

The dry skin model of chronic itch was established as described previously (38, 41, 74, 75). Briefly, the nape of mouse was shaved, and a mixture of acetone and diethylether (1:1) was painted on the neck skin for 15 s, followed by a 30-s DW application (AEW). This regiment was administrated twice (10 a.m. and 6 p.m.) daily for 3 weeks. The littermate control mice received water only on the same schedule. Spontaneous scratches were videotaped and counted for 60 min on the last day of the AEW treatment. Anxiety-like behaviors were examined the next day.

Acute restraint stress

To induce acute restraint stress, the test mouse was immobilized in a modified centrifuge tube once for 90 min (54). Holes were drilled in the body of the tube to allow the animal to breathe. During the restraint period, the control mice were allowed to freely move in the cage. Anxiety-like behavioral assays were done at 30 min after the restraint stress.

Open field test

The open field chamber was made of transparent plastic (40 cm by 40 cm by 40 cm) and divided into a central field (20 cm by 20 cm) and a peripheral field. Mice were placed in the center of the chamber and allowed to move freely for 5 min. The animal movement was tracked by an overhead mounted camera interfaced to a computer running the Noldus (Ethovision 15.0) software. The open field was cleaned with 75% ethanol between each trial. Total distance moved in the field was measured to assess the locomotor activities of the animal. For probing the anxiety state, we analyzed the amount of time spent and the distance traveled in the center field as described previously (52, 61).

Elevated plus maze test

The EPM consists of two open arms (30 cm by 5 cm) and two closed arms (30 cm by 5 cm by 15 cm) intersecting at 90° in the form of a plus, connected with a central platform (5 cm by 5 cm). The maze was elevated 50 cm above the floor. Mice were individually placed in the central platform, with their face pointing toward an open arm and allowed to explore freely for 5 min. Animal behaviors were recorded and analyzed with the Noldus (Ethovision 15.0) software. The percentage of time spent in the open arms and the percentage of open arm entries were extracted as a measure of the anxiety levels, and the total number of entries into four arms was taken as locomotor activities (61). Between each trial, the maze was cleaned with 75% ethanol.

Acute itch behavior test

Acute itch behavior test was performed as described previously (71, 76, 77). Briefly, mice were shaved on the nape of the neck. On the next 2 days, the animals were placed individually in clear Plexiglass observation boxes on an elevated transparent glass floor and allowed to habituate for at least 1 hour for each day. Before testing, mice were acclimated to the testing chamber for at least 30 min. Pruritogen (histamine, 500 μg/50 μl; chloroquine, 200 μg/50 μl; both purchased from Sigma-Aldrich) was then injected intradermally into the back of the neck, and scratching behavior was video-recorded for 30 min. The videos were played back on a computer, and the total numbers of scratching bouts were manually counted by trained experimenters who were blind to the treatment groups.

Bombesin-saporin treatment

To ablate the spinal neurons expressing gastrin-releasing peptide receptor, mice were intrathecally injected with bombesin-saporin (400 ng/5 μl; Advanced Targeting Systems) as described previously (39–41), 10 days before the DCP modeling. Blank-saporin (400 ng/5 μl) was administered in a similar fashion as a control. Behavioral tests were conducted 3 weeks after the initial day of DCP sensitization.

Chemogenetic manipulations

To chemogenetically inactivate all LS neurons, AAV-hSyn-hM4Di-mCherry was bilaterally injected into the rostral or causal LS of C57BL/6J mice. AAV-CaMKIIα-hM4Di-mCherry was used to selectively inhibit excitatory neurons in the Re. For chemogenetic inhibition of LS GABAergic neurons, AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry was injected into the LS of Vgat-Cre mice. To selectively inhibit LS neurons innervated by Re or PFC, C57BL/6J mice were injected with AAV1-hSyn-Cre in the Re or PFC and AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry bilaterally in the LS. To selectively inhibit Re → LS or PFC → LS projection terminals, C57BL/6J mice were injected with AAV-CaMKIIα-hM4Di-mCherry in the Re or PFC, and a guide cannula was implanted into the LS for local CNO (Sigma-Aldrich) infusion. To selectively inhibit LS → LH projection terminals, Vgat-Cre mice received injection of AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry in the LS, and a guide cannula was implanted into the LH. For chemogenetic activation of LS-innervated LH GABAergic neurons, AAV1-EF1α-DIO-Flpo was injected into the LS, and AAV-fDIO-hM3Dq-mCherry was infused into LH of Vgat-Cre mice. For chemogenetic inhibition of the Re → LS → LH disynaptic pathway, AAV-retro-hSyn-Cre was injected into LH, AAV1-hSyn-Flpo was injected into Re, and AAV-hSyn-Con-Fon-hM4Di-EGFP was injected into the LS. For all in vivo chemogenetic manipulations, mice were randomized to receive injection of CNO (intraperitoneally, 2 mg/kg; local, 0.1 mg/ml, 0.3 μl per side) or saline of the equivalent volume. Behavioral tests were performed 30 min after injection.

Cannulation and intracerebral drug microinjection

Cannulation and microinjection were performed as described previously (51, 53, 78). Animals were anesthetized and placed in a stereotaxic frame (RWD Life Science, Shenzhen, China). Stainless steel guide cannulas (26 gauge; RWD Life Science) were implanted bilaterally into LS (AP, 0.70 mm; ML, ±0.40 mm; DV, −2.7 mm) or LH (AP, −0.80 mm; ML, ±1.30 mm; DV, −4.50 mm). The cannulas were fixed to the skull with acrylic dental cement and secured with skull screws. Following surgery, a stylus was inserted into the guide cannula to prevent clogging, Animals were allowed to recover from surgery for at least 1 week before experimental manipulations. Mice were handled and habituated to the infusion procedure several days before drug injections. During the drug microinfusion, the stylus was removed, and an injection tube (0.5 mm lower than the guide) was inserted into the guide cannula. The infusion cannula was connected via a PE20 tube to a motorized microsyringe infusion pump (KDS 310, KD Scientific). To pharmacologically inactivate the LS neurons, muscimol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was administered (0.3 nmol, 300 nl per side, 100 nl/min) 30 min before behavioral assay of anxiety. To chemogenetically manipulate the Re → LS, LS → LH, or PFC → LS projection terminals, CNO (0.1 mg/ml, 0.3 μl per side, 100 nl/min) was microinjected into LS or LH through the implanted cannula to activate DREADD, and the same volume of saline was used as control. After the microfusion, the injector was left in place for 10 min for the drug to fully diffuse. The animal behaviors were tested 30 min after intracerebral drug infusion. All drug injection sites were post hoc verified histologically, and those animals with incorrect diffusion scope were excluded from the data analysis.

Fiber photometry

Fiber photometry recordings were carried out according to the procedures published previously (44–46, 61, 71). Before the recording, the implanted optic fiber was connected to the recording device (ThinkerTech, Nanjing, China) through an external optic fiber. Fluorescence signals produced by an excitation laser beam from a 488-nm laser (OBIS 488LS, Coherent) were reflected through a dichroic mirror (MD498, Thorlabs), focused by a 10× objective lens (NA = 0.3; Olympus) and coupled to an optical commutator (Doric Lenses). An optical fiber (200-mm optical density, NA = 0.37, 1 m in length) guided the light between the commutator and the implanted fiber. The laser power was adjusted at the tip of optical fiber to the low level of 20 to 40 μW to minimize bleaching of the GCaMP6m probes. The excited GCaMP6m signals were passed through a bandpass filter (MF525-39, Thorlabs) and collected in a photomultiplier tube (R3896, Hamamatsu). An amplifier (C7319, Hamamatsu) was used to convert the current output of the photomultiplier tube to voltage signals, which were further filtered through a low-pass filter (40-Hz cutoff; Brownlee 440). The analog voltage signals were digitalized at 100 Hz using a Power 1401 digitizer and Spike2 software (CED, Cambridge, UK).

Activity responses of Re and LS neurons during DCP-induced scratching behaviors or anxiety-like behavioral avoidance in EPM were monitored. To assess scratching-induced changes in neuronal activity, Ca2+ signals around each scratching train (18-s time window) were measured as described previously (71). To probe anxiety-induced changes in neuronal activity, Ca2+ signals were recorded when the mouse moved from a closed arm to an open arm in EPM (18-s time window), following examples in previous studies using fiber photometry recording during the anxiety-like behavioral test (44–46).

For data analysis, fluorescent signals were analyzed with custom-written MATLAB code as described previously (58, 71). Photometry data were exported to MATLAB mat files from Spike2 for further analysis. Fluorescence signal changes (ΔF/F) were calculated as (F − F0)/F0, where F represents the signal value at any given moment and F0 refers to the median of the fluorescence values during the baseline period (from 6 s preceding the scratching train onset or 6 s before the animal moved from a closed arm into an open arm in EPM). To calculate the ΔF/F signal during either scratching or behavioral avoidance, we averaged the ΔF/F values for each 18-s window around the stimulus onset (6 s before and 12 s after). To align ΔF/F signals with the behavior, all fiber photometry data were segmented on the basis of behavior events within individual trials and averaged first across different trials in one animal and then across different animals for each group. All ΔF/F values are presented with heatmaps or per-event plots with shaded areas indicating the SEM. For statistical analysis of changes in fluorescence values, the average ΔF/F values were quantified for both pre- and postperiod around the aligned behavioral events.

Slice electrophysiology

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed in acute brain slices from behaviorally modeled mice or those that had been stereotaxically injected with AAVs, as indicated in different figures. Procedures for slice preparation and electrophysiological recordings followed the previous publications (20, 21, 32, 48, 51). Mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused transcardially with ice-cold oxygenated (saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2) cutting solution containing the following: 93 mM N-methyl-d-glucamine, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, 30 mM NaHCO3, 20 mM Hepes, 25 mM glucose, 5 mM sodium ascorbate, 2 mM thiourea, 3 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM MgSO4, 11.9 mM N-acetyl-l-cysteine, 1 mM CaCl2, and 72 mM HCl. After decapitation, the whole brain was rapidly dissected. Coronal brain slices (300 μm in thickness) containing the LS, LH, or Re were sectioned using a vibratome (VT1000S, Leica) in the cutting solution and then incubated in oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing the following: 125 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 12.5 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, and 25 mM NaHCO3 (pH 7.35); osmolarity, 280 to 300 mosM. Slices were allowed to recover at 31°C for at least 1 hour before use. Then, the brain slice was transferred to a submerging recording chamber and continuously perfused with ACSF (2 to 3 ml/min, bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2) at 32° ± 1°C. Cells were visualized with an upright microscope (BX51WI, Olympus, Japan) equipped with differential interference contrast optics and an optiMOS camera (QImaging, Teledyne Imaging Group, Canada). Patch electrodes (3 to 5 megohm) were pulled by a micropipette puller (Sutter P-2000) from borosilicate glass (Sutter Instrument) and backfilled with internal solution containing the following: 132.5 mM Cs-gluconate, 17.5 mM CsCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10 mM Hepes, 4 mM Mg–adenosine 5′-triphosphate, and 5 mM QX-314, with pH adjusted to 7.3 by CsOH, and the osmolarity being 280 to 290 mosM. Whole-cell patch-clamp signals were acquired with an Axon 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), a Digidata 1440A analog-to-digital converter, and pClamp10.5 software (Molecular Devices). Series resistance and input resistance were monitored throughout the experiments. Recordings were discarded if a substantial change in series resistance (>20%) was detected.

sEPSCs were recorded under the voltage-clamp mode at −70 mV. The baseline sEPSCs of LS neurons were recorded for 5 min and were analyzed from 100 to 200 s after the establishment and stabilization of the recording. Amplitude and frequency of sEPSCs were analyzed with MiniAnalysis software v.6.03 (Synaptosoft Inc., Fort Lee, NJ, USA). For optogenetic stimulation of ChR2 channels, blue light was delivered to the slice through a 40× water-immersion objective lens with a collimated light-emitting diode light source (Lumen Dynamics Group Inc., USA). Repetitive single pulses of blue light (473 nm, 15 s, 0.66 Hz, 5-ms pulse) were delivered, while the light-evoked EPSCs or IPSCs were recorded. The intensity of photostimulation was directly controlled by the stimulator (2 to 18 mW/mm2), while the duration was set through pClamp 10.5 software. Cells were clamped at 0 mV for recording IPSCs (in the presence of 10 μM CNQX, Sigma-Aldrich) and at −70 mV for recording EPSCs (in the presence of 100 μM PTX, Sigma-Aldrich). To verify glutamatergic or GABAergic connections, CNQX (10 μM) with or without activating protein 5 (50 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) or PTX (100 μM) was bath-applied. To validate the monosynaptic connections, TTX (0.5 μM; Tocris) and 4AP (100 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) were sequentially added into the bath solution. To determine the PPR, neurons were voltage clamped at −70 mV. The AMPAR-mediated EPSCs were evoked by paired photostimulation (50-ms interval and 5-ms duration) of ChR2-expressing axons, and the PPR was calculated as the peak amplitude ratio of the second to the first EPSC. To determine AMPAR/NMDAR ratio, the peak amplitude of EPSCs at −70 mV in the presence of PTX (100 μM) was measured as AMPAR-mediated currents, and the peak amplitude of EPSCs at +40 mV in the presence of PTX (100 μM) and CNQX (10 μM) was measured as NMDAR-mediated currents.

To assess the excitability of LS GABAergic neurons under different experimental conditions, firing activities following current injections (2500-ms duration and 0 to 250-pA intensity with a 25-pA increment) were recorded under the current-clamp mode with an internal solution containing the following: 145 mM potassium gluconate, 5 mM NaCl, 10 mM Hepes, 2 mM Mg–adenosine 5′-triphosphate, 0.1 mM Na3–guanosine 5′-triphosphate, 0.2 mM EGTA, and 1 mM MgCl2 (280 to 300 mosM, pH 7.2 with KOH). The threshold current for firing (rheobase) was defined as the minimum current required to elicit at least one or two spikes. Other properties of action potentials were also obtained as previously described (77), including threshold, amplitude, and the kinetics. For examining the excitability of LS-projecting Re neurons, AAV-retro-hSyn-mCherry was injected into the LS, and mCherry+ Re neurons were recorded under current-clamp mode. The action potential firing rate was determined following current injections at different intensities (0 to 100 pA with a 10-pA increment).

To confirm the functionality of expressed hM3Dq and hM4Di, mCherry-labeled LS or LH neurons were recorded under the whole-cell current-clamp mode. An appropriate current (50, 100, or 125 pA, 2500 ms) was injected into the patched neurons, and the numbers of action potentials were counted before and after bath application of CNO (10 μM, 3 to 5 min). Offline data analysis was performed with Clampfit software v. 10.4 (Molecular Devices).

Retrograde and anterograde tracing

For retrograde tracing of the inputs that innervate the LS (fig. S10), AAV-retro-hSyn-EGFP was injected into the LS at the coordinates as described above. For the brain-wide imaging, the coronal brain sections (every third section, 40 μm in thickness) were cut using a vibratome (VT1000S, Leica, Germany). The collected brain sections were stained for 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Thermo Fisher Scientific), mounted on Superfrost slides (12-550-15, Thermo Fisher Scientific, or MAS-03, Matsunami) and covered by coverslips. The EGFP-labeled upstream brain regions were visualized with an Olympus VS200 epifluorescence microscope and analyzed with ImageJ and GraphPad Prism 9.5. For data analysis, we counted the number of EGFP+ cells in each brain structure. Brain regions were identified on the basis of anatomical landmarks and Allen Brain Atlas.