Abstract

Background

Left-sided mechanical prosthetic heart valve thrombosis (PVT) occurs because of suboptimal anticoagulation and is common in low-resource settings. Urgent surgery and fibrinolytic therapy (FT) are the two treatment options available for this condition. Urgent surgery is a high-risk procedure but results in successful restoration of valve function more often and is the treatment of choice in developed countries. In low-resource countries, FT is used as the default treatment strategy, though it is associated with lower success rates and a higher rate of bleeding and embolic complications. There are no randomized trials comparing the two modalities.

Methods

We performed a single center randomized controlled trial comparing urgent surgery (valve replacement or thrombectomy) with FT (low-dose, slow infusion tissue plasminogen activator, tPA) in patients with symptomatic left-sided PVT. The primary outcome was the occurrence of a complete clinical response, defined as discharge from hospital with completely restored valve function, in the absence of stroke, major bleeding or non-CNS systemic embolism. Outcome assessment was done by investigators blinded to treatment allocation. The principal safety outcome was the occurrence of a composite of in-hospital death, non-fatal stroke, non-fatal major bleed or non-CNS systemic embolism. Outcomes will be assessed both in the intention-to-treat, and in the as-treated population. We will also report outcomes at one year of follow-up. The trial has completed recruitment.

Conclusion

This is the first randomized trial to compare urgent surgery with FT for the treatment of left-sided PVT. The results will provide evidence to help clinicians make treatment choices for these patients.

(Clinical trial registration: CTRI/2017/10/010159).

Keywords: Prosthetic heart valve thrombosis, Fibrinolytic therapy, Redo valve surgery, Throbectomy, Valve replacement surgery

1. Background

Left-sided mechanical prosthetic valve thrombosis (PVT) is a rare but devastating complication seen mainly in low- and middle-income countries, where there are significant barriers to maintaining a high quality of anticoagulation.1, 2, 3 Two modalities are currently available for the treatment of symptomatic left-sided prosthetic valve thrombosis namely fibrinolytic therapy (FT), and urgent surgery (valve replacement or thrombectomy). There are no randomized comparisons between these interventions, and therefore guidelines differ in their recommendations regarding the choice of treatment.3, 4, 5

In general, because of the limited availability and high cost of surgery, fibrinolytic therapy has become the first-line treatment in much of the developing world.1,2,6,7 This is despite data suggesting that FT has poor efficacy (successful approximately 60 % of the time)2 and is associated with a high and unpredictable rate of major complications (nearly 17 %) such as death, stroke and major bleeding.2,8 More recently however, observational data suggest that slow, low-dose infusion of tissue-plasminogen activator (t-PA), may be associated with higher success rates and a low risk of complications.9,10

Urgent surgery is less often performed for the treatment of PVT in developing countries. This is mainly because of the high cost and limited availability of surgical teams round the clock. Physicians are also less enthusiastic about surgery because of the perception that surgery is associated with high perioperative mortality, though this is largely confined to patients in NYHA class IV.11, 12, 13, 14 Perioperative mortality among patients in NYHA class I-III is in the range of 4–5%, which is comparable to FT for similar patients.11,14 More importantly, unlike FT, surgery invariably restores valve function with a very low risk of embolic stroke or intracranial hemorrhage (<1 %).11,14 Patients who undergo urgent surgery are also less likely to have recurrent PVT or die during longer term follow-up.13 In a systematic review of observational studies, urgent surgery was associated with large reductions in thromboembolism, major bleeding and recurrent PVT compared to FT.15 The effect of these interventions on mortality was uncertain. We therefore designed a randomized controlled trial to quantify the risk benefit trade-offs involved in treating patients with urgent surgery rather than FT.

2. Methods

2.1. Trial design and objectives

This is an investigator-initiated, single-centre, open-label, two-arm, parallel-group 1:1 randomized active controlled trial investigating effectiveness of urgent surgery (valve replacement or thrombectomy) compared to fibrinolytic therapy for restoration of valve function in symptomatic patients with left-sided PVT. The trial is registered with the clinical trial registry of India www.ctri.in (CTRI/2017/10/010159) and funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research. The study was conducted at a large, tertiary-care, academic medical centre with large valve surgery volumes and experience in treating patients with PVT.1,2,16 The trial protocol and other trial related documents were approved by the institutional ethics review board, and all patients provided written informed consent.

2.2. Eligibility and recruitment

Symptomatic patients presenting to the out-patient clinics of the cardiology and cardiovascular surgery departments, valve clinics or to the emergency department, with mechanical heart valves were eligible to participate if they met the following criteria, (1) Age 18 years and above (2) Recent onset of symptoms (≤2 weeks) and (3) NYHA class II-IV (4) objectively documented left-sided PVT.

The diagnosis of PVT was suspected in patients presenting with symptoms attributable to valve dysfunction (dyspnea, angina, congestive failure) of less than 2 weeks duration, with or without muffled valve sounds on auscultation. Definitive diagnosis required the documentation of new onset of hypomobile or immobile valve leaflets on fluoroscopy with or without elevated transvalvular gradients on Doppler echocardiography.17

Exclusion criteria: Participants were excluded if there were absolute contraindications to FT such as past history of intracranial hemorrhage, active bleeding from any site, ischemic stroke in the preceding 3 months, left atrial thrombus on transthoracic echocardiography. Asymptomatic patients (incidentally detected valve dysfunction on routine fluoroscopy) were excluded as our policy is to optimise anticoagulation in these patients rather than offer fibrinolytic therapy. Patients were excluded if their treating surgeon was unwilling to operate. Pregnant patients and those who were unable to provide informed consent were also excluded.

Potential patients were screened for eligibility by the cardiologist and randomised to either of the treatments after obtaining informed consent.

2.3. Randomization

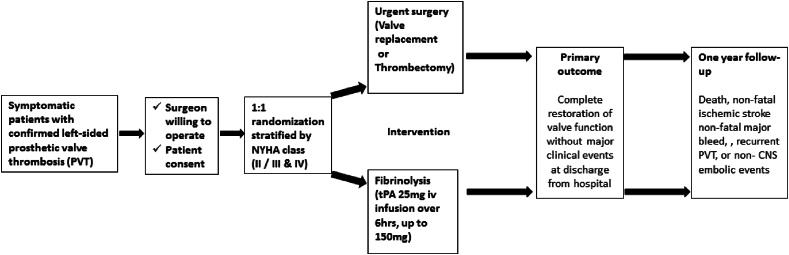

The allocation sequence was generated using Stata 12 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC) by an independent statistician not involved in the recruitment of patients, using permuted blocks of varying sizes. Randomization was stratified by symptom status (NYHA class II or class III/IV) (Fig. 1). Sequentially numbered, opaque sealed envelopes containing the treatment allocation, were prepared by the study statistician, and handed over to the study coordinator, who was also not involved in patient recruitment or treatment. The envelope was opened by the study coordinator upon request of the treating cardiologist after patient eligibility was confirmed and informed consent was obtained. The allocation document was signed with date and time and emailed to the study statistician on the day of randomization. Patients randomised to receive FT were given FT in the coronary care unit by the treating cardiologist. Those randomised to surgery were operated upon by the on-duty cardiac surgeon at the next available operating theatre slot.

Fig. 1.

Trial overview

*Data source: Karthikeyan et al, Eur Heart J 2013; 34:1557–66.

2.4. Trial interventions

Patients randomized to urgent surgery were scheduled to undergo the procedure within 48 h of randomization. The choice of performing valve replacement or thrombectomy, and the need for any additional procedures was at the discretion of the operating surgeon.

At the time of designing the study in 2015, the standard FT regimen was intravenous streptokinase. However, before the initiation of the trial, standard practice at our hospital had evolved to low-dose, slow infusion tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA). Consequently, all patients assigned to FT received t-PA in the following dosing schedule: 25 mg iv infusion over 6 h, and repeated (up to a total dose of 150 mg) until restoration of valve function or the occurrence of major complication. The use of slower or more rapid infusion rates (25 mg over 25 h, or 100 mg over 2 h, was left to physician discretion, depending on patient characteristics (Fig. 1).

2.5. Blinding

Due to the nature of the intervention, neither participant nor the research staff were blinded. However, clinicians adjudicating the primary outcome were unaware of treatment allocation. Echocardiograms and fluoroscopy runs were recorded at discharge by the treating physician and reviewed and interpreted by a clinician unaware of treatment assignment. Participants in both study arms were followed up by a study physician, and uniform, guideline-recommended oral anticoagulation regimens and targets were adhered to. Other treatments (such as for heart failure or arrhythmia) were instituted as warranted by the patients’ clinical condition.

2.6. Outcome measures

Primary outcome: The primary outcome was the occurrence of a complete clinical response, defined as discharge from hospital with completely restored valve function, in the absence of stroke, major bleeding or non-CNS systemic embolism. Complete restoration of valve function was defined as (1) restoration of normal leaflet motion on fluoroscopy, and (2) normalization of transvalvular pressure gradients on Doppler echocardiography (mitral MDG<6 mmHg and EDG<2 mmHg, and aortic peak gradient<30 mmHg).

Secondary outcomes: The first secondary outcome was the occurrence of a composite of in-hospital death, non-fatal stroke, non-fatal major bleed or non-CNS systemic embolism. This was the principal safety outcome. We also determined the occurrence of a composite of death, recurrent PVT, non-fatal stroke or non-CNS systemic embolism, non-fatal major bleed, and persistent abnormal valve function (or re-do surgery for persistent valve dysfunction), at one-year follow-up from the time of randomization. Stroke was defined as any focal neurologic deficit lasting 24 h with or without brain imaging suggestive of a primary ischemic or haemorrhagic origin leading to tissue infarction. Systemic embolism was defined as abrupt vascular insufficiency associated with clinical and radiological evidence of arterial occlusion in the absence of other likely mechanisms. Major bleeding was diagnosed as per the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) criteria. The expected rate of adverse events with each treatment are listed in the box.

2.7. Sample size considerations

We anticipated that about 90 % of patients undergoing urgent surgery and about 60 % of patients treated with FT will have a complete clinical response (the primary outcome). We assumed a lower success rate with FT, because our definition of success requires the absence of major complications unlike the definition of success used in previous studies in the literature. This is arguably the more meaningful definition. This is borne out by prospectively collected data from our centre.2 We anticipate a success rate of 90 % for patients undergoing surgery based on that observed in the largest series from a centre with experience comparable to ours.14 The high mortality seen with surgery was largely restricted to patients in NYHA class IV, with less symptomatic patients having a lower mortality (4–5%).13,14 Only 12 % of our patients were expected to present in NYHA class IV,2 and we anticipated that fewer than 10 % of our surgical patients would die, have a stroke or a major bleed. With 80 patients, we will be able to detect a difference of this magnitude with 80 % power with two-sided type 1 error set at 0.05. For 90 % power, the sample size required would be 105. These sample sizes allow for a 5 % noncompliance with surgery and 5 % crossover to fibrinolytic therapy.

2.8. Measurement of outcomes and follow-up

In-hospital monitoring Response to FT was monitored by TTE and fluoroscopy performed at 8–12-h intervals. Patients were also clinically evaluated by treating physicians for the occurrence of adverse outcomes. In the event of clinical suspicion of adverse events, they underwent appropriate testing to confirm or rule out these events. All patients underwent pre-discharge echocardiography and fluoroscopy. Recordings of a representative fluoroscopy run showing valve leaflet mobility and an echocardiogram at the time of discharge were obtained. These were analysed off-line by a cardiologist unaware of treatment allocation.

Follow-up After discharge, patients were seen in hospital as per requirement by the treating surgeon and cardiologist. At each visit fluoroscopy and echocardiography were routinely performed. In addition, the study coordinator maintained contact with study patients over phone to address any health-related queries, and to document the occurrence of adverse events.

2.9. Data collection and management

Before randomisation and following consent baseline characteristics such as rhythm, left ventricular function, EuroSCOREII, and coagulation status were collected by the cardiologist involved in screening. Details of FT and surgical procedure were documented from medical records (Table 1).

Table 1.

Trial procedures and data collection.

| At randomization | In hospital | One year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline data | |||

| Demographics | X | ||

| Transthoracic echocardiography | X | ||

| Cine fluoroscopy | X | ||

| ECG | X | X | |

| Coagulation status | X | ||

| EuroSCORE II | X | ||

| Trial interventions | |||

| Fibrinolytic therapy | X | ||

| Urgent surgery | X | ||

| Outcome assessment | |||

| Valve function | X | ||

| Adverse clinical events | X | X | |

The trial data were collected on electronic case record forms using a validated clinical data management system (OpenClinica, community version 3.12) with an inbuilt query management system. Data quality was reviewed periodically by the data manager for completeness. Source data checks were done in the event of any discrepancy or missing vital information. The medical information collected from the participant and from the medical records for study purposes were de-identified (i.e. items such as name, address, phone number, hospital unique identifying number, family physician's name) and labelled using an unique patient identification number. Only the clinical investigators and study coordinator, had access to participant identifying information.

2.10. Statistical methods

The primary analysis will be a comparison of the proportion of patients who have complete clinical response at the time of discharge, adjusted for baseline NYHA stratum, using logistic regression. Analysis will be by the intention-to-treat principle wherein all trial participants will be included in the randomised treatment group irrespective of cross-over, or receipt of either intervention within 48 h s of randomisation. We will adjust our effect estimate for any imbalances in strong baseline predictors of the outcome between the two groups. These will include age, sex, presence of atrial fibrillation (AF), early PVT (thrombosis occurring ≤12 months after valve replacement) and mitral PVT. The effect size will be expressed as an odds ratio (OR) along with 95 % confidence interval (CI). Testing for any assumptions and model fit will be reported. P values less than 0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

The principal safety outcome i.e. occurrence of a composite of in-hospital death, non-fatal stroke, major bleeding or non-CNS systemic embolism, at the time of discharge will be analysed using the win-ratio method.18 If any participant did not receive any of the two treatments, they will be excluded from this analysis. We will determine the difference in the proportion of the composite of death, non-fatal stroke, major bleeding, recurrent PVT, or non-CNS systemic embolism, at one year using the win-ratio method. The hierarchy for the win-ratio analysis will be the following: death, non-fatal stroke, major bleeding, recurrent PVT, and non-CNS systemic embolism. We will also determine the difference in the composite of death, non-fatal stroke, major bleeding, recurrent PVT, or non-CNS systemic embolism, and persistent abnormal valve function (or re-do surgery for persistent valve dysfunction) from the time of randomisation until the last follow up, using a chi-squared test.

Any sub-group analyses will be considered exploratory. No statistical adjustment for multiplicity will be done. We do not expect missing data for the primary outcome and secondary safety outcome since they are in-hospital clinical events. All analyses will be performed using Stata 18 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

2.11. Trial oversight

A 3-member data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) consisting of a statistician, cardiologist, and a clinician with extensive experience in clinical trial methodology oversaw the conduct of the trial. Given the small sample size, interim analyses of the data may not provide effect estimates reliable enough to dictate stopping the trial for benefit or harm. Therefore, we did not pre-specify any trial stopping rules. However, the DSMB monitored patient safety, recruitment rates, and overall event rates and provided advice to the trial principal investigator. The DSMB met in person once after enrolment of 63 patients, at about 24 months following trial initiation. After review of the data, despite the slow progress in recruitment, the DSMB recommended continuing the trial.

2.12. Conflicts of interest

None of the investigators have financial or other conflicts of interest related to this study. The trial is funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research and the funders do not have any role in conduct, analysis, and reporting of this trial.

2.13. Recruitment and trial progress

Between October 2017 and May 2023, 79 patients with symptomatic left-sided PVT were enrolled, of whom 39 were randomized to urgent surgery and 40 to FT with t-PA. The trial was anticipated to complete recruitment of 105 patients (for 90 % power) in about three years. However, during the 2 years of the intervening Covid-19 pandemic, no patients could be enrolled. Recruitment rates remained slow following the pandemic as well. Therefore, in view of the cost overruns, and slow recruitment, a decision was made to terminate enrolment at about 80 patients (for 80 % power).

Patients were young (mean age 36 years) and most often had a thrombosed mitral prosthesis (72 %). The median time from the index valve surgery was 37 months. A third of patients had a history of prior valve thrombosis. About a quarter of the patients were in atrial fibrillation and 43 % were in NYHA class III or IV at presentation (Table 2). All patients assigned to FT received the treatment, and 5 patients randomized to surgery crossed over to the FT arm.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of enrolled patients.

| Patient characteristics | Overall n = 79 |

|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 36.1 (9.5) |

| Female | 40 (50.6) |

| Valve replaced (n) | 46 (58.2) 10 (12.7) 23 (29.1) |

| Mitral | |

| Aortic | |

| Mitral and Aortic | |

| Median time in months since valve replacement (inter quartile range) | 37 (9, 86) |

| Previous history of valve thrombosis | |

| None | 52 (65.8) |

| Mitral | 19 (24.1) |

| Aortic | 7 (8.8) |

| Mitral and Aortic | 1 (1.3) |

| Median time in months since last PVT (Interquartile range) | 9 (5, 36) |

| History of ischemic stroke | 5 (6.3) |

| Currently affected valve | |

| Mitral | 57 (72.2) |

| Aortic | 18 (22.8) |

| Mitral and Aortic | 4 (5) |

| Rhythm | |

| Sinus rhythm | 54 (68.4) |

| Atrial flutter/Atrial fibrillation | 23 (29.1) |

| Not available | 2 (2.5) |

| NYHA | |

| II | 45 (57) |

| III | 22 (27.8) |

| IV | 12 (15.2) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 10 (12.7) |

| Left ventricular dysfunction | 9 (11.4) |

| Inotropic support | 5 (6.3) |

| INR at presentation (mean, SD) | 1.7 (0.8) |

| EUROSCORE II (mean, SD) | 2.4 (1.6) |

3. Discussion

The SAFE-PVT trial is the first randomized comparison between urgent surgery and FT for the treatment of symptomatic patients with left-sided PVT. The risk-benefit trade-offs of performing urgent surgery compared to FT with t-PA are currently unknown, as all previous comparisons between the two modalities of treatment are based on observational data. The existing evidence strongly suggests that surgery is associated with large reductions in the risk of ischemic stroke, major bleeding, and the risk of recurrent PVT.15 However, there is uncertainty regarding the difference in the risk of death associated with surgery.15 Moreover, patients with left-sided PVT seen in developing countries are young (average age about 32 years),2 compared to those seen in developed countries,13 and peri-operative mortality may consequently be even lower than reported in the latter studies. This may result in a risk-benefit trade-off favouring surgery.

Left-sided PVT is emblematic of the general paucity of evidence from randomized-controlled trials for the management of disease conditions seen in low-resource countries. Despite the high morbidity and mortality associated with the condition, there has been just one randomized trial addressing its treatment,2 and none have systematically addressed its prevention. Management is generally based on observational data, and the local availability of treatment options. Once practices are ingrained, conducting randomized trials becomes challenging, resulting in slow recruitment. In SAFE-PVT, for example, the single most important impediment to enrolment was surgeon reluctance to perform urgent surgery. Though we were unable to recruit patients for 2 years during the Covid-19 pandemic, surgeon unwillingness to operate contributed significantly to the delay in reaching the planned sample size.

In addition, it is well known that management practices based on observational data and physician experience may not result in optimal patient outcomes, and may also not represent the best use of the scarce available resources. Recent experience with other diseases affecting low-resource settings suggests that formal testing in randomized trials may yield unexpected results,19 indicating the need for investment in the manpower and infrastructure required to conduct randomized trials in low-resource countries. Relatively uncommon disease conditions such as left-sided PVT also highlight the need for establishment of formal or informal collaborations within and between low-resource countries in order to facilitate the rapid recruitment of sufficient patient numbers into trials so that they are adequately powered and yield meaningful results.

The main strength of SAFE-PVT is that we compared urgent surgery performed by expert valve surgery teams with contemporary FT using t-PA as advocated by the most recent practice guidelines.4,5 Therefore this trial is ideally poised to provide evidence for the relative efficacy of the two approaches. Nevertheless, there are a few limitations. First, being a single-centre study conducted at a tertiary academic medical centre with extensive experience in managing left-sided PVT and access to expert surgical care, the results may not be widely generalizable. Second, because of a reluctance to randomize, several of our cardiac surgeons declined participation in the study, and we were able to enrol just about 25 % of patients with left-sided PVT presenting to our hospital during the recruitment period. Finally, we did not use transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) routinely in determining eligibility for the trial. Though some investigators advocate the routine use of TEE for determining thrombus size,20 we believe that the evidence for this is not strong. The association between thrombus size and outcomes with FT21 are almost completely explained by NYHA class. We therefore stratified patients by NYHA class to account for differences in thrombus size and degree of obstruction.

In summary, SAFE-PVT is the first randomized trial to compare urgent surgery with FT for the treatment of left-sided PVT. The results will provide evidence to help clinicians make treatment choices for these patients.

Funding

Indian Council of Medical Research (Grant reference: 5/4/1-13/14-NCD-II).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:Correspndoing author is a member of editorial board (epidemiology & trials) in this journal (Indian Heart Journal) If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Gupta D., Kothari S.S., Bahl V.K., et al. Thrombolytic therapy for prosthetic valve thrombosis: short- and long-term results. Am Heart J. 2000;140(6):906–916. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.111109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karthikeyan G., Math R.S., Mathew N., et al. Accelerated infusion of streptokinase for the treatment of left-sided prosthetic valve thrombosis: a randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 2009;120(12):1108–1114. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.876706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soria Jimenez C.E., Papolos A.I., Kenigsberg B.B., et al. Management of mechanical prosthetic heart valve thrombosis: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81(21):2115–2127. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.03.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otto C.M., Nishimura R.A., Bonow R.O., et al. ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2020;143(5):e72–e227. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vahanian A., Beyersdorf F., Praz F., et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(7):561–632. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caceres-Loriga F.M., Perez-Lopez H., Morlans-Hernandez K., et al. Thrombolysis as first choice therapy in prosthetic heart valve thrombosis. A study of 68 patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006;21(2):185–190. doi: 10.1007/s11239-006-4969-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddy N.K., Padmanabhan T.N., Singh S., et al. Thrombolysis in left-sided prosthetic valve occlusion: immediate and follow-up results. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58(2):462–470. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)92229-2. ; discussion 470-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karthikeyan G., Mathew N., Math R.S., Devasenapathy N., Kothari S.S., Bahl V.K. Timing of adverse events during fibrinolytic therapy with streptokinase for left-sided prosthetic valve thrombosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2011;32(2):146–149. doi: 10.1007/s11239-011-0579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozkan M., Cakal B., Karakoyun S., et al. Thrombolytic therapy for the treatment of prosthetic heart valve thrombosis in pregnancy with low-dose, slow infusion of tissue-type plasminogen activator. Circulation. 2013;128(5):532–540. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozkan M., Gunduz S., Guner A., et al. Thrombolysis or surgery in patients with obstructive mechanical valve thrombosis: the multicenter HATTUSHA study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(10):977–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deviri E., Sareli P., Wisenbaugh T., Cronje S.L. Obstruction of mechanical heart valve prostheses: clinical aspects and surgical management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17(3):646–650. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renzulli A., Onorati F., De Feo M., et al. Mechanical valve thrombosis: a tailored approach for a multiplex disease. J Heart Valve Dis. 2004;13(Suppl 1):S37–S42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roudaut R., Lafitte S., Roudaut M.F., et al. Management of prosthetic heart valve obstruction: fibrinolysis versus surgery. Early results and long-term follow-up in a single-centre study of 263 cases. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;102(4):269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roudaut R., Roques X., Lafitte S., et al. Surgery for prosthetic valve obstruction. A single center study of 136 patients. Eur J Cardio Thorac Surg. 2003;24(6):868–872. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karthikeyan G., Senguttuvan N.B., Joseph J., Devasenapathy N., Bahl V.K., Airan B. Urgent surgery compared with fibrinolytic therapy for the treatment of left-sided prosthetic heart valve thrombosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(21):1557–1566. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balasundaram R.P., Karthikeyan G., Kothari S.S., Talwar K.K., Venugopal P. Fibrinolytic treatment for recurrent left sided prosthetic valve thrombosis. Heart. 2005;91(6):821–822. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.044123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montorsi P., De Bernardi F., Muratori M., Cavoretto D., Pepi M. Role of cine-fluoroscopy, transthoracic, and transesophageal echocardiography in patients with suspected prosthetic heart valve thrombosis. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85(1):58–64. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00607-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pocock S.J., Ariti C.A., Collier T.J., Wang D. The win ratio: a new approach to the analysis of composite endpoints in clinical trials based on clinical priorities. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(2):176–182. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connolly S.J., Karthikeyan G., Ntsekhe M., et al. Rivaroxaban in rheumatic heart disease-associated atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(11):978–988. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2209051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Özkan M., Kaymaz C., Kirma C., et al. Intravenous thrombolytic treatment of mechanical prosthetic valve thrombosis: a study using serial transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(7):1881–1889. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00654-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong A.T., Roudaut R., Ozkan M., et al. Transesophageal echocardiography improves risk assessment of thrombolysis of prosthetic valve thrombosis: results of the international PRO-TEE registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]