Abstract

Background

Efforts are underway to capitalize on the computational power of the data collected in electronic medical records (EMRs) to achieve a learning health system (LHS). Artificial intelligence (AI) in health care has promised to improve clinical outcomes, and many researchers are developing AI algorithms on retrospective data sets. Integrating these algorithms with real-time EMR data is rare. There is a poor understanding of the current enablers and barriers to empower this shift from data set–based use to real-time implementation of AI in health systems. Exploring these factors holds promise for uncovering actionable insights toward the successful integration of AI into clinical workflows.

Objective

The first objective was to conduct a systematic literature review to identify the evidence of enablers and barriers regarding the real-world implementation of AI in hospital settings. The second objective was to map the identified enablers and barriers to a 3-horizon framework to enable the successful digital health transformation of hospitals to achieve an LHS.

Methods

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines were adhered to. PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and IEEE Xplore were searched for studies published between January 2010 and January 2022. Articles with case studies and guidelines on the implementation of AI analytics in hospital settings using EMR data were included. We excluded studies conducted in primary and community care settings. Quality assessment of the identified papers was conducted using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool and ADAPTE frameworks. We coded evidence from the included studies that related to enablers of and barriers to AI implementation. The findings were mapped to the 3-horizon framework to provide a road map for hospitals to integrate AI analytics.

Results

Of the 1247 studies screened, 26 (2.09%) met the inclusion criteria. In total, 65% (17/26) of the studies implemented AI analytics for enhancing the care of hospitalized patients, whereas the remaining 35% (9/26) provided implementation guidelines. Of the final 26 papers, the quality of 21 (81%) was assessed as poor. A total of 28 enablers was identified; 8 (29%) were new in this study. A total of 18 barriers was identified; 5 (28%) were newly found. Most of these newly identified factors were related to information and technology. Actionable recommendations for the implementation of AI toward achieving an LHS were provided by mapping the findings to a 3-horizon framework.

Conclusions

Significant issues exist in implementing AI in health care. Shifting from validating data sets to working with live data is challenging. This review incorporated the identified enablers and barriers into a 3-horizon framework, offering actionable recommendations for implementing AI analytics to achieve an LHS. The findings of this study can assist hospitals in steering their strategic planning toward successful adoption of AI.

Keywords: life cycle, medical informatics, decision support system, clinical, electronic health records, artificial intelligence, machine learning, routinely collected health data

Introduction

Background

The growing adoption of electronic medical records (EMRs) in many high-income countries has resulted in improvements in health care delivery through the implementation of clinical decision support systems at the point of care [1]. To meet the ever-accelerating demands for clinical care, various innovative models have been developed to harness the potential of EMR data [2-4]. These new care models aim to enable health care organizations to achieve the quadruple aim of care, which includes enhancing patient experience, advancing providers’ experience, improving the health of the population, and reducing health care costs [5].

Artificial intelligence (AI) holds the potential to improve health system outcomes by enhancing clinical decision support systems [6,7]. AI aims to augment human intelligence through complicated and iterative pattern recognition, generally on large data sets that exceed human abilities [8]. While a large body of academic literature has demonstrated the efficacy of AI models in various health domains, most of these models remain as proof of concept and have never been implemented in real-world workflows [9]. This demonstrates the relatively inconsequential endeavors of many AI studies that fail to produce any meaningful impact in the real world. Even with the substantial investments made by the health industry, the implementation of AI analytics in complex clinical practice is still at an early stage [10]. In a limited number of instances, AI has been successfully implemented, largely for nonclinical uses such as service planning or trained on limited static data sets such as chest x-rays or retinal photography [11]. The factors influencing the success or failure of AI implementations in health are poorly investigated [12]. Understanding these barriers and enablers increases the likelihood of successful implementation of AI for the digital transformation of the health system [13,14], ultimately aiding in achieving the quadruple aim of health care [5].

Toward the Digital Transformation of Health Care

A 3-horizon framework has been previously published to help health systems create an iterative pathway for successful digital health transformation (Figure 1 [15]). Horizon 1 aims to optimize the routine collection of patient data during every interaction with the health system. In horizon 2, the data collected during routine care are leveraged in real or near real time to create analytics. Finally, in horizon 3, the insights from data and digital innovations are collated to develop new models of care. A health care system focused on continuous improvement is referred to as a learning health system (LHS) that uses routinely collected data to monitor and enhance health care outcomes consistently [16]. When health care organizations reach the third horizon, they can leverage data in near real time to create ongoing learning iterations and enhance patient care, leading to the establishment of an LHS [17].

Figure 1.

The 3-horizon framework for digital health transformation (adapted from Sullivan et al [15] with permission from CSIRO Publishing).

Regarding the 3-horizon model, EMRs are the foundation of horizon 1 (Figure 1). While many health organizations have successfully adopted EMRs into their existing workflows, the transition to horizons 2 and 3 has been challenging for many of these health care facilities [18]. A critical phase in this transition involves moving beyond the capture of EMR data for delivering analytics, including AI, aiming to improve clinical outcomes. There is little published evidence to assist health systems in making this transition [19,20].

Analysis of Prior Work

Before conducting our review, we performed a manual search on Google Scholar using our Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms along with the “review” keyword to identify previous review papers that aimed at reviewing studies on the implementation of clinical AI in health care settings. We also included review papers known to our research team. Between 2020 and 2022, we identified 4 reviews that were relevant to the implementation of AI in health care systems [21-24]. Overall, these papers reviewed 189 studies between 2010 and 2022. The characteristics of these reviews, outlined in Table 1, were the year of publication, the targeted care settings, the source of data, the predictive algorithm, and whether the predictive algorithm was implemented.

Table 1.

The inclusion criteria for this study and previous work.

| Study | Year | Health care setting | Data source | Predictive algorithm | Implementation state |

| Lee et al [22] | 2020 | Any | EMRa | Any | Implemented |

| Wolff et al [23] | 2021 | Any | Any | AIb and MLc | Implemented |

| Sharma et al [21] | 2022 | Any | Any | AI and ML | Implemented |

| Chomutare et al [24] | 2022 | Any | Any | AI and ML | Implemented or developed |

| Our study | 2023 | Hospitals | EMR | AI and ML | Implemented or guidelines |

aEMR: electronic medical record.

bAI: artificial intelligence.

cML: machine learning.

The prior works identified 20 enablers and 13 barriers to AI implementation in health care across 4 categories: people, process, information, and technology (Multimedia Appendix 1 [21-24]). Overall, the findings derived from these review papers hold significant potential in providing valuable insights for health systems to navigate the path toward digital health transformation. One prevailing shortcoming of these studies is the absence of alignment with evidence-based digital health transformation principles to provide health care organizations with actionable recommendations to enable an LHS [17], therefore limiting their applicability for strategic planning within hospital organizations.

Research Significance and Objectives

Hospitals are intricate hubs within the health care ecosystem, playing a central role in providing comprehensive medical care and acting as crucial pillars supporting the foundations of health care systems worldwide. Understanding the factors influencing the success or failure of AI in hospitals provides valuable insights to optimize the integration of these emerging technologies into hospital facilities. While the previous reviews included all health care settings [21-24], our study only focused on hospital settings. Given the limited instances regarding the implementation of AI in hospital facilities, this study explored the real-world case studies that have practically reported their AI implementation solutions in hospital facilities, aiming to synthesize the evidence of enablers and barriers within their implementation process. In addition to the inclusion of these implementation case studies, we incorporated implementation guidelines as they can potentially assist in the overall understanding of AI implementation in hospitals. This study also focused on aligning the evidence of enablers and barriers within the 3-horizon framework [15], offering a way to establish an empirical infrastructure. As a result, this can enable health care organizations to learn, adapt, and accelerate progress toward an LHS [25].

This review investigated the following research questions (RQs): (1) What enablers and barriers are identified for the successful implementation of AI with EMR data in hospitals? (RQ 1) and (2) How can the identified enablers of and barriers to AI implementation lead to actions that drive the digital transformation of hospitals? (RQ 2).

In addressing these questions, our objectives were to (1) conduct a systematic review of the literature to identify the evidence of enablers of and barriers to the real-world implementation of AI in hospital settings and (2) map the identified enablers and barriers to a 3-horizon framework to enable the successful digital health transformation of hospitals to achieve an LHS.

Methods

Search Strategy

This study followed an extended version of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines to outline the review methodology with comprehensive details [26]. PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and IEEE Xplore were searched on April 13, 2022. We reviewed prior work to determine potential MeSH keywords relevant to our study [21-24]. A research librarian helped with the definition of the MeSH keywords in PubMed and the translation of that search strategy to all platforms searched. The search strategies were applied across the 4 databases (Multimedia Appendix 2). The MeSH keywords used to search PubMed were as follows: product lifecycle management, artificial intelligence, machine learning, deep learning, natural language processing, neural networks, computer, deep learning, big data, hospital, inpatient, medical, clinic, deploy, integrate, monitor, post prediction, data drift, and regulatory. Using the Boolean operator OR, their synonyms were joined to form search phrases. Combining search phrases using the AND operator produced the final search string. We incorporated the term “data drift” to the title and abstract, and full-text search as it is a prominent concept for the continuous integration of AI. The term “regulatory” was also added to our search criteria because it is a relevant term for the implementation of AI in health care within the domain of software as a medical device. The reference lists of the included studies were examined to ensure that all relevant papers were included.

Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria were articles published from January 1, 2010, to April 13, 2022, that included case studies and guidelines on the implementation of AI analytic tools in hospital settings using EMR data. Given the scarcity of real-world AI tools in hospital settings, especially the scarcity of published case studies of unsuccessful implementations of clinical AI tools, we specifically included case studies that successfully implemented AI within hospitals to understand lessons learned and provide use cases that other jurisdictions may learn from. On the basis of a review of frameworks for AI implementation in health care practice, we defined the term implementation as “an intentional effort designed to change or adapt or uptake interventions into routines” [19]. The term “barrier” was defined as “experiences that impeded, slowed, or made implementations difficult in some way” [20]. In contrast, the term enablers was defined as factors, experiences, or processes that facilitated the implementation process. Studies conducted in community or primary care settings were excluded as our main focus was hospital facilities. Studies that did not use AI models were also excluded. We also eliminated non–English-language and conference articles. Studies that focused on regulatory domains and challenges, opportunities, requirements, and recommendations were also excluded as they did not demonstrate real-world AI implementation. The selection of studies was based on the criteria specified in Textbox 1.

Inclusion criteria for this study.

Inclusion criteria

Population: adults (aged ≥18 y); inpatients

Intervention: successfully implemented artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) tools using hospital electronic medical record data

Study design: case studies that implemented AI and ML in the real world; guidelines on the real-world implementation of AI and ML

Publication date: January 2010 to April 2022

Language: English

Exclusion criteria

Population: nonadults (aged <18 y); outpatients

Intervention: traditional statistical methods; rule-based systems; systems without AI and ML

Study design: studies without implementation of AI and ML; studies focused on AI and ML development, regulatory-related domains, challenges, opportunities, and recommendations; conference papers; primary care or community settings

Language: non-English

Screening

For the screening and data extraction procedures, the Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation) systematic review software was used [27]. A 2-stage screening process was performed with the involvement of 2 reviewers (AKR and OP). In the initial stage, the reviewers assessed the relevance of titles and abstracts based on the inclusion criteria. Subsequently, in the second stage, the full texts of the included articles were reviewed by AKR and OP independently. Consensus was reached through discussion between the reviewers whenever necessary.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

AKR and OP conducted the procedure of data extraction. The following study characteristics were extracted from all final included studies: country, clinical setting, study type (case study or guideline), and aim of study. With the adoption of EMR as a prerequisite for AI development, our focus was on extracting evidence of enablers and barriers solely within horizons 2 (implementation) and 3 (creating new models of care). In total, 2 reviewers (AKR and OP) independently extracted evidence regarding enablers and barriers (RQ 1), subsequently reaching consensus through weekly discussions and analysis. The extracted data were disseminated among our research team for review and to gather additional feedback.

To address the second RQ (RQ 2), we mapped the findings from previous reviews along with the found factors in this study across horizons 2 and 3 of the digital transformation framework [15]. Following the data extraction phase, 2 reviewers independently mapped the identified enablers and barriers to 4 categories (people, process, information, and technology). During the mapping of a given enabler or barrier, if it was related to the development of AI analytics, it was mapped to horizon 2 considering its relevance across the 4 domains (people, technology, information, and processes). When an enabler or barrier was associated with the postdevelopment phase focusing on establishing new care models, it was mapped to horizon 3. Consensus was reached between AKR and OP through a meeting to finalize the mapping phase.

Quality Assessment

For the included use case studies, we used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [28] to conduct a quality assessment. The choice of the MMAT was suitable as the included use case studies exhibited a range of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods designs. For evaluating the methodology of guideline studies, we followed the ADAPTE framework [29]. With 9 modules for guideline development, this framework was designed to streamline and enhance the process of creating guidelines within the health domain. The quality assessment was conducted independently by 2 authors (AKR and OP), and any discrepancies were resolved through a meeting.

Results

Study Selection

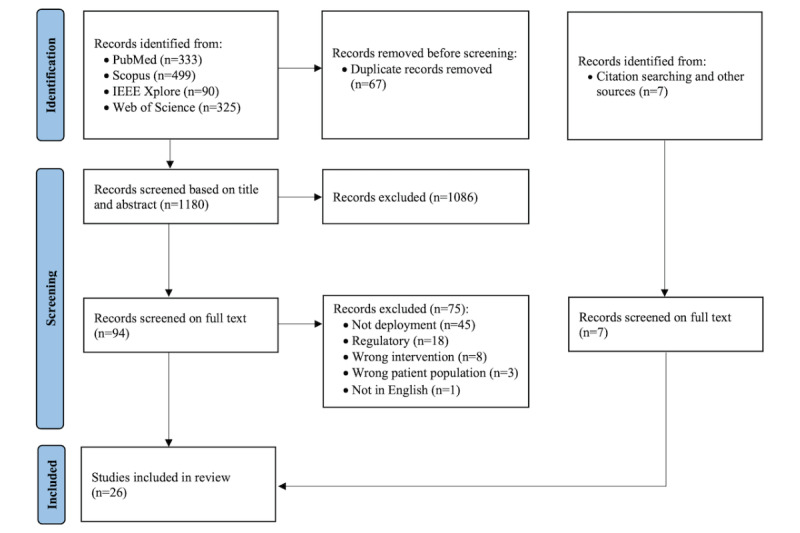

The search strategy retrieved 1247 papers from PubMed, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, and Web of Science for analysis, and 67 (5.37%) duplicates were identified and eliminated using the EndNote (Clarivate Analytics) citation manager. After screening titles and abstracts, 92.03% (1086/1180) of the studies were removed as the inclusion criteria were not satisfied. A total of 7.97% (94/1180) of the papers remained for full-text review following title and abstract screening. In total, 48% (45/94) of papers were excluded because AI models were not implemented in clinical care. A total of 19% (18/94) of the studies were excluded because they focused on regulatory domains. In total, 9% (8/94) of the studies were excluded due to being the wrong intervention (eg, studies that did not develop AI models). A total of 3% (3/94) of the studies were found to have a clinical population that did not align with our inclusion criteria (eg, hospitalized patients). One study was not in English and was excluded. In addition, 7 studies were discovered by scanning the reference lists of the included articles. In total, 26 studies were included in this review, comprising 9 (35%) guideline studies and 17 (65%) papers with successful implementation examples (Table 2). Figure 2 presents the PRISMA flow diagram outlining the outcomes of this review.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies included in this review.

| Study, year | Country | Clinical setting | Study type | Aim of study | Enablers | Barriers |

| Wilson et al [30], 2021 | United Kingdom | General | Guideline |

|

|

|

| Svedberg et al [31], 2022 | Sweden | General | Guideline |

|

|

|

| Subbaswamy and Saria [32], 2019 | United States | General | Guideline |

|

|

|

| Pianykh et al [33], 2020 | United States | Radiology | Guideline |

|

|

|

| Leiner et al [34], 2021 | The Netherlands | Radiology | Guideline |

|

|

|

| Gruendner et al [35], 2019 | Germany | General | Guideline |

|

|

|

| Eche et al [36], 2021 | United States | Radiology | Guideline |

|

|

|

| Allen et al [37], 2021 | United States | Radiology | Guideline |

|

|

|

| Verma et al [38], 2021 | Canada | General | Guideline |

|

|

|

| Wiggins et al [39], 2021 | United States | Radiology | Case study |

|

|

|

| Wang et al [40], 2021 | China | Radiology | Case study |

|

|

|

| Strohm et al [41], 2020 | The Netherlands | Radiology | Case study |

|

|

|

| Soltan et al [42], 2022 | United Kingdom | EDk triage | Case study |

|

|

|

| Sohn et al [43], 2020 | United States | Radiology | Case study |

|

|

|

| Pierce et al [44], 2021 | United States | Radiology | Case study |

|

|

|

| Kanakaraj et al [45], 2022 | United States | Radiology | Case study |

|

|

|

| Jauk et al [46], 2020 | Austria | General | Case study |

|

|

|

| Davis et al [47], 2019 | United States | General | Case study |

|

|

|

| Blezek et al [48], 2021 | United States | Radiology | Case study |

|

|

|

| Pantanowitz et al [49], 2020 | United States | Pathology | Case study |

|

|

|

| Fujimori et al [50], 2022 | Japan | ED | Case study |

|

|

|

| Joshi et al [20], 2022 | United States | General | Case study |

|

|

|

| Pou-Prom et al [51], 2022 | Canada | General | Case study |

|

|

|

| Baxter et al [52], 2020 | United States | General | Case study |

|

|

|

| Sandhu et al [53], 2020 | United States | ED | Case study |

|

|

|

| Sendak et al [54], 2020 | United States | ED | Case study |

|

|

|

aAI: artificial intelligence.

bCST: collaborative science team.

cHCP: health care provider.

dHL7: Health Level 7.

eML: machine learning.

fFHIR: Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources.

gOMOP-CDM: Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership Common Data Model.

hQA: quality assurance.

iSOLE: Standardized Operational Log of Events.

jCT: computerized tomography.

kED: emergency department.

lPACS: picture archiving and communication system.

mREDCap: Research Electronic Data Capture.

nHIPAA: Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

oEHR: electronic health record.

pCDS: clinical decision support.

Figure 2.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart for study selection.

Study Characteristics

Table 2 outlines the characteristics of the included studies in this review. The publication dates of the included studies ranged from 2019 to 2022 [20,30-54]. In total, 65% (17/26) of the studies were case studies on the implementation of AI in hospitals [20,39-54], whereas the remaining 35% (9/26) were implementation guidelines [30-38].

Of the 26 identified studies, 15 (58%) originated from the United States [20,32,33,36,37,39,43-45,47-49,52-54]; 2 (8%) originated from the United Kingdom [30,42]; 2 (8%) originated from the Netherlands [34,41]; and 1 (4%) originated from China [55], Australia [46], Japan [50], Canada [51], Austria [46], Germany [35], and Sweden [31] each.

Radiology was the clinical setting in 46% (12/26) of the studies [33,34,36,37,39-41,43-45,48,49]. A total of 38% (10/26) of the studies were conducted in general inpatient wards [20,30-32,35,38,46,47,51,52], and 15% (4/26) were conducted in emergency departments [42,50,53,54].

Quality Assessment

Regarding the 35% (9/26) of guideline studies, none fully adhered to the ADAPTE framework [29]. Although these included guideline studies had clear scopes and purposes aligned with this review, they all lacked details concerning the assessment of quality, external validation, and aftercare planning procedures. The details of this assessment for all the guideline studies can be found in Multimedia Appendix 3 [20,30-54].

With respect to the 65% (17/26) of case studies, they were classified into 3 groups: quantitative descriptive (12/17, 71%) [39,40,42-49,51,54], qualitative (4/17, 24%) [20,41,52,53], and mixed methods (1/17, 6%) [50]. Overall, 5 of the case studies met the MMAT criteria: all 4 (80%) qualitative studies and the one mixed methods study. The remaining 71% (12/17) of quantitative descriptive studies failed to fully adhere to the MMAT criteria. In all but 17% (2/12) of these quantitative descriptive studies, an appropriate data sampling strategy was not used to represent their target population [40,49]. The statistical analysis of the findings was assessed as appropriate in 58% (7/12) of the quantitative descriptive studies [42,43,46,47,49,51,54]. Overall, our assessment revealed that the quality of 81% (21/26) of the included studies was poor due to insufficient reporting of their methodologies (Multimedia Appendix 3).

RQ Findings

RQ 1A Findings: Enablers of AI Implementation in Hospitals

A total of 28 enablers extracted from both prior work and this study (n=8, 29% were new enablers identified in our study) are presented in Table 3. Most of these newly identified enablers (7/8, 88%) related to the information and technology categories, highlighting the potential opportunities for hospitals regarding data readiness and required technologies for the successful implementation of AI. A total of 54% (15/28) of the enablers were shared findings between the previous reviews and this study.

Table 3.

Consolidated view of research question 1A (enablers to artificial intelligence [AI] implementation; N=26)a.

| Horizon and category | Source | Studies, n (%) | ||||

|

|

Previous studies | This study |

|

|||

| Horizon 2: creating AI analytics | ||||||

|

|

People | 12 (46) | ||||

|

|

|

Enabler 1: multidisciplinary team |

|

|

||

|

|

|

Enabler 2: experienced data scientists | —b |

|

||

|

|

Process | 22 (85) | ||||

|

|

|

Enabler 3: co-design with clinicians |

|

|

||

|

|

|

Enabler 4: robust performance monitoring and evaluation |

|

|||

|

|

|

Enabler 5: seamless integration |

|

|||

|

|

|

Enabler 6: organizational resources |

|

|||

|

|

|

Enabler 7: evidence of clinical and economic AI added value |

|

|||

|

|

|

Enabler 8: addressing data shift |

|

|

||

|

|

|

Enabler 9: improved team communication |

|

— |

|

|

|

|

Information | 9 (35) | ||||

|

|

|

Enabler 10: data quality |

|

|

||

|

|

|

Enabler 11: data security |

|

|

||

|

|

|

Enabler 12: data visualization | — |

|

||

|

|

Technology | 15 (58) | ||||

|

|

|

Enabler 13: continuous learning capability |

|

|

||

|

|

|

Enabler 14: containerization | — |

|

||

|

|

|

Enabler 15: interoperability |

|

|

||

|

|

|

Enabler 16: shared infrastructure | — |

|

||

|

|

|

Enabler 17: customization capability |

|

|||

|

|

|

Enabler 18: vendor-agnostic infrastructure | — |

|

||

|

|

|

Enabler 19: computational and storage resources | — |

|

||

|

|

|

Enabler 20: alert considerations | — |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enabler 21: ease of integration | — |

|

|

|

| Horizon 3: implementation of new models of care | ||||||

|

|

People | 8 (31) | ||||

|

|

|

Enabler 22: skilled end users |

|

|||

|

|

|

Enabler 23: hospital leadership |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enabler 24: innovation champions | — |

|

||

|

|

Process | 9 (35) | ||||

|

|

|

Enabler 25: staff training |

|

|

||

|

|

|

Enabler 26: provide incentives when using AI | — |

|

||

|

|

|

Enabler 27: limiting non-AI solutions |

|

— |

|

|

|

|

Information | 1 (4) | ||||

|

|

|

Enabler 28: usability |

|

|

|

|

aEnablers identified in previous reviews and this review were mapped to 4 categories of the 3-horizon framework [15].

bNot specified.

Within the scope of the 3-horizon framework [15], most included studies in this paper (22/26, 85%) indicated that the process domain facilitated the development of AI analytics within horizon 2 [20,30,31,33-44,47,48,50-54]. Co-design with clinicians was the most commonly reported enabler in 46% (12/26) of the papers in horizon 2 [30,31,33,35,39-41,43,44,52-54]. The process domain was also highlighted as having a facilitative role in the creation of new care models with AI (horizon 3) in 35% (9/26) of the papers [30,34,44,46,48,50,51,53,54]. Training end users to adopt AI solutions and interpret the insights was reported in all these 9 studies as an enabling factor in horizon 3.

Technological factors were highlighted in 58% (15/26) of the studies as enablers within horizon 2 [20,32-35,39,40,43-45,48-51,54], with the most commonly reported factor being continuous learning capability of AI analytics [32,33,40,44,51] and containerization capability by providing separated development environments [34,35,40,43,44] and applying the interoperability techniques ensuring seamless integration of diverse formats of clinical data from different hardware and software sources [34,35,39,45].

Of all the included studies, 46% (12/26) [30,34,35,38-41,43,44,48,51,54] and 31% (8/26) [30,33,35,44,46,48,53,54] identified people-related enablers across horizons 2 and 3, respectively, with multidisciplinary teams in horizon 2 and trained end users in horizon 3 being the 2 most reported enablers.

Enabling factors related to the information domain were discussed in 35% (9/26) of the included studies in this review [32,35,37,39,40,45,49-51], with data quality being the most reported enabler of the successful implementation of AI in hospitals in >50% of these papers (5/9, 56%) [37,39,40,49,51]. The enablers of the AI adoption in hospitals were reported to include factors such as considerations of data security [35,45,51] and data visualization [32,50] in horizon 2 along with AI usability [38] solutions in horizon 3.

RQ 1B Findings: Barriers to AI Implementation in Hospitals

Overall, a total of 18 barriers to AI implementation in hospitals were extracted from both prior work and this study, with 5 (28%) found to be new in this study (Table 4). Most of these newly identified barriers (4/5, 80%) were related to the information and technology categories. A total of 50% (9/18) of the identified barriers were found to be shared findings between the previous work and this study. In our analysis, some factors played dual roles, acting as both enablers and barriers. For instance, “Seamless integration” served as an enabler (enabler 5; Table 3), whereas “Disruptive integration” acted as a barrier (barrier 3; Table 4). We reported both enablers and barriers with such reversed meanings to highlight the real-world complexities due to which such factors can exhibit this duality.

Table 4.

Consolidated view of research question 1B (barriers to artificial intelligence [AI] implementation)a.

| Horizon and category | Source | Studies, n (%) | |||||||

|

|

Previous studies | This study |

|

||||||

| Horizon 2: creating AI analytics | |||||||||

|

|

Process | 15 (58) | |||||||

|

|

|

Barrier 1: insufficient performance assessment |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Barrier 2: lack of standardized guidelines for AI implementation |

|

||||||

|

|

|

Barrier 3: disruptive integration |

|

||||||

|

|

|

Barrier 4: inadequate continuous learning |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Barrier 5: complexity of maintenance |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Barrier 6: lack of clear consensus on alert definitions | —b |

|

|

||||

|

|

|

Barrier 7: insufficient data preprocessing |

|

— |

|

||||

|

|

Information | 8 (31) | |||||||

|

|

|

Barrier 8: poor data quality |

|

||||||

|

|

|

Barrier 9: data heterogeneity | — |

|

|||||

|

|

|

Barrier 10: data privacy | — |

|

|

||||

|

|

|

Barrier 11: challenges with data availability | — |

|

|||||

|

|

Technology | 5 (19) | |||||||

|

|

|

Barrier 12: lack of customization capability | — |

|

|||||

|

|

|

Barrier 13: computational limitations of hardware | — |

|

|||||

| Horizon 3: implementation of new models of care | |||||||||

|

|

People | 5 (19) | |||||||

|

|

|

Barrier 14: inexperienced end users with AI output |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Barrier 15: lack of clinician trust |

|

||||||

|

|

Process | 2 (8) | |||||||

|

|

|

Barrier 16: alert fatigue |

|

||||||

|

|

|

Barrier 17: difficulties with understanding AI outputs |

|

— |

|

||||

|

|

Information | 1 (4) | |||||||

|

|

|

Barrier 18: data shift |

|

|

|

||||

aBarriers identified in previous reviews and this review were mapped to 4 categories of the 3-horizon framework [15].

bNot specified.

Regarding the 3-horizon framework [15], 58% (15/26) of the included studies in this review showed that the process domain hindered the development of AI within horizon 2 [20,31,37,40-43,45-47,50-54]. The lack of sufficient performance assessment within horizon 2 was the most commonly reported barrier in 27% (7/26) of the papers [37,41,42,46,47,50]. The factors related to the process domain were also reported as barriers to the implementation of AI within horizon 3, with 8% (2/26) of the papers reporting alert fatigue as an obstacle to AI adoption for creating new models of care [20,53].

Information-related factors were highlighted in 31% (8/26) of the studies as barriers within horizon 2 [20,35,36,46,51], with the most commonly mentioned one being poor data quality [20,35,36,46,51]. The challenge with data shift was reported as part of the information domain within horizon 3 [32].

Technology-related challenges in horizon 2 were identified in 19% (5/26) of the studies, including issues such as the lack of customization capability and computational limitations of hardware [35,43,48,50,52].

Within horizon 3, a total of 19% (5/26) of the included papers highlighted the barriers related to the people domain [20,30,41,50,53], with lack of trust by clinicians and inexperienced end users in using AI within their routine workflows being 2 barriers reported in these studies.

RQ 2 Findings: Mapping the Findings to the 3-Horizon Framework

The identified enablers and barriers to AI implementation in hospitals (RQ 1) were mapped to the 3-horizon framework [15] across 4 categories: people, process, information, and technology within horizons 2 and 3 (Figure 3 [15]).

Figure 3.

Mapping the identified enablers and barriers to the 3-horizon framework (adapted from Sullivan et al [15] with permission from CSIRO Publishing). *Enablers described in Table 3; **Barriers described in Table 4. AIML: artificial intelligence machine learning; B: barrier; E: enabler; EMR: electronic medical record.

In horizon 2, we identified a total of 21 enablers, with most associated with technology (n=9, 43%) and processes (n=7, 33%). Moving to horizon 3, a total of 7 enablers were identified, spanning the categories of people (n=3, 43%), processes (n=3, 43%), and information (n=1, 14%). Regarding barriers, horizon 2 presented a total of 13 barriers, with >50% (n=7, 54%) falling into the process category. In horizon 3, we identified a total of 5 barriers primarily distributed among the people (n=2, 40%), process (n=2, 40%), and information (n=1, 20%) categories.

Discussion

Principal Findings

The health care industry needs to adopt new models of care to respond to the ever-growing demand for health services. Over the last decade, the academic community has shown considerable interest in the application of AI to explore new innovative models of care. Despite the numerous papers published each year exploring the potential of AI in various health domains, only a few studies have been implemented into routine workflows. Investigating the factors that lead to the success or failure of AI in health care could potentially provide actionable insights for the effective implementation of AI in clinical workflows. In this review, we explored the current state of the literature focusing on the implementation of AI in hospitals. Our review of 26 studies revealed several enablers of and barriers to the implementation of AI in digital hospitals. Although our search for studies dated back to 2010, all 26 case studies and guidelines found in our study were published from 2019 onward. This is not surprising considering the significant progress made in AI implementation across many fields in recent years. Given such substantial advancements, implementation science needs to be further developed to accommodate these new AI innovations in health care [19]. This paper can serve as a road map for decision makers, presenting key actionable items to translate AI into hospital settings and leveraging it for potential new models of care.

While this paper extends the findings of previous reviews by examining the factors associated with AI implementation in health care [22-24], a significant aspect found in both previous reviews and our study underscores the significance of process-related factors for creating AI analytics. A large number of papers identified in this study (22/26, 85%) reported process factors as enablers of their AI implementation, aligning with the factors found in all previous reviews (enablers 3-9; Table 3). This commonality indicates the significant opportunity for hospitals to leverage their existing workflows as a strategic approach to enable AI adoption. In the context of developing innovative care models through AI analytics, obstacles associated with people (barriers 14 and 15; Table 4) were identified in 19% (5/26) of the included studies, consistent with findings in 2 previous reviews [22,24]. This highlights the influence of human factors in facilitating the integration of AI in practice.

Apart from the common findings between this and previous reviews, there are several novel aspects to this study. First, it centered specifically on hospitals, the largest and richest source of clinical data. Second, it incorporated AI implementation guidelines from the included studies, allowing for a broader understanding of AI implementation. Third, our review identified new enablers of AI implementation regarding technology and information that can facilitate AI implementation, including quality of data, shared infrastructure for continuous development, and capabilities regarding hardware resources. Fourth, this paper identified new barriers to AI implementation, with most of them being within the domains of process, information, and technology. These barriers included challenges such as data privacy, dealing with heterogeneous data, limitations with the customization of AI analytics, and ambiguity surrounding the design of alert definitions. Finally, the study findings were mapped to a 3-horizon framework encompassing 4 key categories: people, information, process, and technology. This framework offers a clear and practical road map for health care organizations planning to create new AI analytics.

It is important to note that, while our primary focus was on hospital facilities, the findings of this review may exhibit variations across other health care settings. For example, the incorporation of AI in outpatient care may demand different technological infrastructures to enable AI development. Future research can expand upon this study by investigating the evidence of enablers and barriers associated with AI implementation in wider health care settings, including primary care and outpatient care, as we expect that the outcomes of this study may differ in other health care settings. Moreover, the incorporation of studies related to regulatory aspects can be a crucial component for a more comprehensive understanding of the trajectory of AI adoption within health care systems.

Toward AI Implementation in Hospitals

Actionable Recommendations

In this section, we consolidate the findings of this study and prior work within the scope of a 3-horizon framework [15] and provide recommendations for health care organizations that plan to implement AI analytics in hospitals (Textbox 2). These recommendations are not the ultimate solution but rather a flexible action plan to facilitate AI implementation and mitigate potential challenges regarding the digital transformation of hospitals.

Recommendations for artificial intelligence (AI) adoption in hospitals.

Horizon 1: establishing digital infrastructure

Implement functional electronic medical record system

Focus on improving data quality

Maintain data privacy and security

Facilitate data availability

Horizon 2: create AI analytics

Co-design with multidisciplinary team

Employ experienced data scientists

Adopt interoperability methods

Focus on AI usability

Continuously develop and evaluate AI results

Enhance data security and privacy

Improve computational capabilities

Focus on seamless integration

Enhance customization capability

Demonstrate AI added value

Improve team communication

Define design standards for AI output

Focus on vendor-agnostic architecture

Horizon 3: create new models of care

Restructure the clinical care models using insights from AI analytics

Provide user training

Continuously improve quality to produce reliable AI output and minimize data shift and alert fatigue

Leverage hospital leaders to drive AI adoption

Appoint innovation managers

Provide incentive for using AI

Horizon 1: Establishing Digital Infrastructure

Data form the core of AI development to create clinical analytics. Some information barriers emerging in horizon 2, presented in Table 4, may be associated with challenges regarding EMR data, for example, quality of data (barrier 8), data heterogeneity (barrier 9), and data privacy (barrier 10). In the integration of EMR systems within hospital settings, careful attention must be paid to the functionality of the system to enable routine data collection to support the continuous development of AI analytics. Prioritizing the enhancement of data quality through the implementation of rigorous validation processes is a key factor in producing generalizable, reliable, and effective AI outputs. It is also imperative to ensure strict adherence to data privacy protocols during the EMR implementation, safeguarding sensitive patient information and maintaining ethical standards in handling health care data.

Horizon 2: Creating Analytics

Horizon 2 primarily focuses on data extraction and developing AI analytics. The successful implementation of AI in this horizon will be discussed within the following themes.

Form a Diverse Team of Experts

There is evidence suggesting that building a multidisciplinary team consisting of clinicians, nurses, end users, and data scientists can facilitate the successful design and implementation of AI in hospitals (enabler 1; Table 3). Experienced data scientists can potentially increase the success of AI in health care by ensuring accurate, reliable, and fair AI output in addition to identifying biases, handling complex medical data effectively, and optimizing AI algorithms (enabler 2; Table 3).

Enhance the Existing Processes

While horizon 2 revolves around technical aspects of AI implementation, the evidence indicates that involving clinicians, end users, and technical staff in the design and implementation stages is needed for successful integration (enabler 3; Table 3). The co-design strategy can alleviate challenges such as the lack of consensus on alert definitions (barrier 6; Table 4), leading to usability improvement (enabler 28; Table 3). Enhancing the understanding of AI output through training end users has the potential to alleviate concerns about the usability of AI output, fostering a smoother adoption of AI technologies in hospitals.

The studies recognized that minimizing workflow disruption is key for the successful implementation of AI (enabler 5; Table 3). To minimize workflow disruption and ensure a smooth transition when implementing new AI solutions in hospitals, it is important to engage end users from the early stage of the development process [56], although training and education should be provided to help staff members effectively incorporate the AI solution into their daily routines. For successful implementation of less disruptive technologies such as AI, it is recommended to establish a clear vision and communication by the leadership team (enabler 23; Table 3), have innovation champions (enabler 24; Table 3), and provide incentives (enabler 26; Table 3) to drive long-term adoption and habit formation [57].

Continuous AI development with the use of routinely collected data and clinicians’ feedback ensures that AI results accurately reflect the current clinical situations in hospital settings (enabler 13; Table 3). This can support clinicians in making more accurate diagnoses and treatment decisions by leveraging the latest insights derived from AI analytics. While insufficient assessment of AI performance in hospital settings is considered a prominent obstacle to successful implementation (barrier 1; Table 4), continuous development and monitoring helps avoid “data drift,” a phenomenon in which AI models lose accuracy over time due to changes in the data or environment [32,47].

Strive for Better Data Quality and Security

The studies indicated that the implementation of AI is hindered by data privacy concerns (barrier 10; Table 4). Hospitals can mitigate the risks associated with data handling and storage by adopting standardized data frameworks and interoperability techniques (enabler 15; Table 3). These measures help minimize vulnerabilities and enhance overall data security.

The quality of data in developing AI analytics refers to the accuracy, completeness, consistency, reliability, and relevance of the data used to implement AI analytics and is considered a crucial enabler for successful AI implementation in hospitals [58]. Hospitals are encouraged to improve their data quality by implementing robust data governance protocols [21,23,31,41,42], adopting standardized data protocols to facilitate interoperability [24,34,35,39,45], and actively validating and verifying the accuracy of the data with clinicians and data scientists [30,41,54].

Strengthen Technological Infrastructures

The use of third-party hardware and software in AI solutions can limit control and raise security and privacy concerns [43]. Open-source software can improve transparency and accountability by allowing experts to identify vulnerabilities, but it can also make it easier for malicious actors to exploit them [35]. To mitigate this risk, hospitals can adopt validated open-source software with appropriate security and privacy measures, such as standardized databases and interoperability protocols [24,34,35,39,45].

Horizon 3: New Models of Care

The objective of horizon 3 is to restructure the clinical care model by harnessing the insights generated from AI analytics. While the main focus of this horizon is on clinicians and processes, fewer practical experiences are available for health organizations to help in shaping the implementation strategy.

Training end users to understand AI output is suggested to enhance the adoption of AI in hospitals (enabler 25; Table 3). Hospital leadership plays a pivotal role in facilitating the adoption of AI by providing strategic guidance, allocating necessary resources, and fostering a supportive environment for the implementation of AI initiatives (enabler 23; Table 3). Hospitals are suggested to appoint innovation managers to actively promote and facilitate the applications of AI, fostering uptake and driving the implementation process in health care (enabler 24; Table 3). Resourcing is the crucial enabler of AI integration, in particular adequate skill sets. Experienced clinicians who can interpret AI results are essential for ensuring that AI systems are used effectively and responsibly in health care organizations (enabler 22; Table 3). As a result, this can redefine the traditional models of care by advocating for evidence-based practices, patient-centered care, collaborative care, and continuous quality improvement to enhance patient outcomes and the overall quality of the care provided by health care organizations.

Limitations

Our search strategy identified 26 studies that met the inclusion criteria. All 26 studies were conducted in high-income countries. As a result, the diversity and applicability of the findings to other health care systems were constrained.

By excluding regulatory frameworks from this review in the rapidly evolving regulatory landscape, we may have limited the important implementation guidelines that ensure patient safety and ethical use of AI provided by health care regulatory bodies.

We conducted a thorough examination of the reference lists in the included studies to ensure the inclusion of all relevant papers. Despite a valid research methodology, this approach may introduce publication bias, a factor to consider when appraising the study’s findings.

The methodological reporting of most studies included in this review was assessed as poor, potentially limiting the quality of the findings of this study. While consensus discussions were held after the quality assessment to mitigate potential discrepancies in the final evaluations, it is worth recognizing that this process is subjective and the perspectives of reviewers may evolve over time, resulting in variations when assessed by different individuals.

Although our intention was to identify successful implementations, it is possible that we missed significant enablers or barriers present in failed implementations.

Conclusions

This review incorporated the identified enablers of and barriers to the implementation of AI into a 3-horizon framework to guide future implementations of hospital AI analytics to evolve practice toward an LHS. Successful AI implementation in hospitals requires a shift in conventional resource management to support a new AI implementation and maintenance strategy. Using analytics to enable better decisions in hospitals is critical to enable the ever-increasing need for health care to be met.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable assistance of Mr Lars Eriksson, a research librarian at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Australia, for his expertise and guidance in identifying the search strategy for this study. The authors did not use any generative artificial intelligence tools for this research paper. This study was funded by Digital Health Cooperative Research Centre Limited (DHCRC). DHCRC is funded under the Commonwealth Government’s Cooperative Research Centres program. AKR and OJC are supported by DHCRC (DHCRC-0083). The funder played no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, or writing of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AI

artificial intelligence

- EMR

electronic medical record

- LHS

learning health system

- MeSH

Medical Subject Heading

- MMAT

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RQ

research question

Enablers and barriers identified in previous reviews.

Search strategies across 4 databases for this review.

Quality assessment of the included studies.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: AKR, CS, SS, JDP, and OJC conceptualized this paper. This research was supervised by our senior researchers CS, SS, JDP, MG, and OJC. The development of the search strategy was conducted by AKR, CS, OJC, and JDP. In total, 2 authors (AKR and OP) conducted the screening process and extracted excerpts that were included in the tables of this paper. AKR, CS, SS, JDP, MG, AV, and OJC reviewed the findings. AKR drafted the manuscript with input from CS, SS, JDP, AV, MG, and OJC. AKR prepared all the figures in this manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Williams F, Boren SA. The role of the electronic medical record (EMR) in care delivery development in developing countries: a systematic review. Inform Prim Care. 2008;16(2):139–45. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v16i2.685. http://hijournal.bcs.org/index.php/jhi/article/view/685 .685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa PA, Nov O. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: evidence from the field. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 Jul 01;27(7):1132–5. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa072. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32324855 .5824298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reeves JJ, Hollandsworth HM, Torriani FJ, Taplitz R, Abeles S, Tai-Seale M, Millen M, Clay BJ, Longhurst CA. Rapid response to COVID-19: health informatics support for outbreak management in an academic health system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 Jun 01;27(6):853–9. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa037. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32208481 .5811358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barlow J, Bayer S, Curry R. Implementing complex innovations in fluid multi-stakeholder environments: experiences of ‘telecare’. Technovation. 2006 Mar;26(3):396–406. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2005.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sikka R, Morath JM, Leape L. The Quadruple Aim: care, health, cost and meaning in work. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015 Oct;24(10):608–10. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004160.bmjqs-2015-004160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamel Rahimi A, Canfell OJ, Chan W, Sly B, Pole JD, Sullivan C, Shrapnel S. Machine learning models for diabetes management in acute care using electronic medical records: a systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2022 Apr 02;162:104758. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2022.104758.S1386-5056(22)00072-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu KH, Beam AL, Kohane IS. Artificial intelligence in healthcare. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018 Oct;2(10):719–31. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0305-z.10.1038/s41551-018-0305-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maddox TM, Rumsfeld JS, Payne PR. Questions for artificial intelligence in health care. JAMA. 2019 Jan 01;321(1):31–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.18932.2718456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly CJ, Karthikesalingam A, Suleyman M, Corrado G, King D. Key challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence. BMC Med. 2019 Oct 29;17(1):195. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1426-2. https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-019-1426-2 .10.1186/s12916-019-1426-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aung YY, Wong DC, Ting DS. The promise of artificial intelligence: a review of the opportunities and challenges of artificial intelligence in healthcare. Br Med Bull. 2021 Sep 10;139(1):4–15. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldab016.6353269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin J, Ngiam KY, Teo HH. Role of artificial intelligence applications in real-life clinical practice: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021 Apr 22;23(4):e25759. doi: 10.2196/25759. https://www.jmir.org/2021/4/e25759/ v23i4e25759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015 Apr 21;10:53. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0. https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0 .10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He J, Baxter SL, Xu J, Xu J, Zhou X, Zhang K. The practical implementation of artificial intelligence technologies in medicine. Nat Med. 2019 Jan;25(1):30–6. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0307-0. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/30617336 .10.1038/s41591-018-0307-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo Y, Hao Z, Zhao S, Gong J, Yang F. Artificial intelligence in health care: bibliometric analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Jul 29;22(7):e18228. doi: 10.2196/18228. https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e18228/ v22i7e18228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sullivan C, Staib A, McNeil K, Rosengren D, Johnson I. Queensland Digital Health Clinical Charter: a clinical consensus statement on priorities for digital health in hospitals. Aust Health Rev. 2020 Sep;44(5):661–5. doi: 10.1071/AH19067.AH19067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etheredge LM. A rapid-learning health system. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(2):w107–18. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.w107.hlthaff.26.2.w107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mandl KD, Kohane IS, McFadden D, Weber GM, Natter M, Mandel J, Schneeweiss S, Weiler S, Klann JG, Bickel J, Adams WG, Ge Y, Zhou X, Perkins J, Marsolo K, Bernstam E, Showalter J, Quarshie A, Ofili E, Hripcsak G, Murphy SN. Scalable collaborative infrastructure for a learning healthcare system (SCILHS): architecture. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(4):615–20. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002727. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24821734 .amiajnl-2014-002727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim HC, Austin JA, van der Vegt AH, Rahimi AK, Canfell OJ, Mifsud J, Pole JD, Barras MA, Hodgson T, Shrapnel S, Sullivan CM. Toward a learning health care system: a systematic review and evidence-based conceptual framework for implementation of clinical analytics in a digital hospital. Appl Clin Inform. 2022 Mar;13(2):339–54. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1743243. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/35388447 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gama F, Tyskbo D, Nygren J, Barlow J, Reed J, Svedberg P. Implementation frameworks for artificial intelligence translation into health care practice: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2022 Jan 27;24(1):e32215. doi: 10.2196/32215. https://www.jmir.org/2022/1/e32215/ v24i1e32215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joshi M, Mecklai K, Rozenblum R, Samal L. Implementation approaches and barriers for rule-based and machine learning-based sepsis risk prediction tools: a qualitative study. JAMIA Open. 2022 Apr 18;5(2):ooac022. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooac022. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/35474719 .ooac022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma M, Savage C, Nair M, Larsson I, Svedberg P, Nygren JM. Artificial intelligence applications in health care practice: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2022 Oct 05;24(10):e40238. doi: 10.2196/40238. https://www.jmir.org/2022/10/e40238/ v24i10e40238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee TC, Shah NU, Haack A, Baxter SL. Clinical implementation of predictive models embedded within electronic health record systems: a systematic review. Informatics (MDPI) 2020 Sep;7(3):25. doi: 10.3390/informatics7030025. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33274178 .25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolff J, Pauling J, Keck A, Baumbach J. Success factors of artificial intelligence implementation in healthcare. Front Digit Health. 2021 Jun 16;3:594971. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2021.594971. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34713083 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chomutare T, Tejedor M, Svenning TO, Marco-Ruiz L, Tayefi M, Lind K, Godtliebsen F, Moen A, Ismail L, Makhlysheva A, Ngo PD. Artificial intelligence implementation in healthcare: a theory-based scoping review of barriers and facilitators. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Dec 06;19(23):16359. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192316359. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph192316359 .ijerph192316359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Platt JE, Raj M, Wienroth M. An analysis of the learning health system in its first decade in practice: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Mar 19;22(3):e17026. doi: 10.2196/17026. https://www.jmir.org/2020/3/e17026/ v22i3e17026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Page Matthew J, McKenzie Joanne E, Bossuyt Patrick M, Boutron Isabelle, Hoffmann Tammy C, Mulrow Cynthia D, Shamseer Larissa, Tetzlaff Jennifer M, Akl Elie A, Brennan Sue E, Chou Roger, Glanville Julie, Grimshaw Jeremy M, Hróbjartsson Asbjørn, Lalu Manoj M, Li Tianjing, Loder Elizabeth W, Mayo-Wilson Evan, McDonald Steve, McGuinness Luke A, Stewart Lesley A, Thomas James, Tricco Andrea C, Welch Vivian A, Whiting Penny, Moher David. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021 Mar 29;372(1):n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. http://www.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=33782057 .10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation. [2022-04-13]. https://www.covidence.org/

- 28.Hong QN, Gonzalez-Reyes A, Pluye P. Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) J Eval Clin Pract. 2018 Jun;24(3):459–67. doi: 10.1111/jep.12884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fervers B, Burgers JS, Voellinger R, Brouwers M, Browman GP, Graham ID, Harrison MB, Latreille J, Mlika-Cabane N, Paquet L, Zitzelsberger L, Burnand B. Guideline adaptation: an approach to enhance efficiency in guideline development and improve utilisation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011 Mar;20(3):228–36. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.043257.bmjqs.2010.043257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson A, Saeed H, Pringle C, Eleftheriou I, Bromiley PA, Brass A. Artificial intelligence projects in healthcare: 10 practical tips for success in a clinical environment. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2021 Jul;28(1):e100323. doi: 10.1136/bmjhci-2021-100323. https://informatics.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=34326160 .bmjhci-2021-100323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Svedberg P, Reed J, Nilsen P, Barlow J, Macrae C, Nygren J. Toward successful implementation of artificial intelligence in health care practice: protocol for a research program. JMIR Res Protoc. 2022 Mar 09;11(3):e34920. doi: 10.2196/34920. https://www.researchprotocols.org/2022/3/e34920/ v11i3e34920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Subbaswamy A, Saria S. From development to deployment: dataset shift, causality, and shift-stable models in health AI. Biostatistics. 2020 Apr 01;21(2):345–52. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxz041.5631850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pianykh OS, Langs G, Dewey M, Enzmann DR, Herold CJ, Schoenberg SO, Brink JA. Continuous learning AI in radiology: implementation principles and early applications. Radiology. 2020 Oct;297(1):6–14. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leiner T, Bennink E, Mol CP, Kuijf HJ, Veldhuis WB. Bringing AI to the clinic: blueprint for a vendor-neutral AI deployment infrastructure. Insights Imaging. 2021 Feb 02;12(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s13244-020-00931-1. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33528677 .10.1186/s13244-020-00931-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gruendner J, Schwachhofer T, Sippl P, Wolf N, Erpenbeck M, Gulden C, Kapsner LA, Zierk J, Mate S, Stürzl M, Croner R, Prokosch HU, Toddenroth D. KETOS: clinical decision support and machine learning as a service - a training and deployment platform based on Docker, OMOP-CDM, and FHIR Web Services. PLoS One. 2019 Oct 03;14(10):e0223010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223010. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223010 .PONE-D-19-12555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eche T, Schwartz LH, Mokrane FZ, Dercle L. Toward generalizability in the deployment of artificial intelligence in radiology: role of computation stress testing to overcome underspecification. Radiol Artif Intell. 2021 Oct 27;3(6):e210097. doi: 10.1148/ryai.2021210097. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34870222 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allen B, Dreyer K, Stibolt R Jr, Agarwal S, Coombs L, Treml C, Elkholy M, Brink L, Wald C. Evaluation and real-world performance monitoring of artificial intelligence models in clinical practice: try it, buy it, check it. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 Nov;18(11):1489–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2021.08.022.S1546-1440(21)00740-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verma AA, Murray J, Greiner R, Cohen JP, Shojania KG, Ghassemi M, Straus SE, Pou-Prom C, Mamdani M. Implementing machine learning in medicine. CMAJ. 2021 Aug 30;193(34):E1351–7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.202434. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=35213323 .193/34/E1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiggins WF, Magudia K, Schmidt TM, O'Connor SD, Carr CD, Kohli MD, Andriole KP. Imaging AI in practice: a demonstration of future workflow using integration standards. Radiol Artif Intell. 2021 Oct 27;3(6):e210152. doi: 10.1148/ryai.2021210152. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34870224 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang B, Jin S, Yan Q, Xu H, Luo C, Wei L, Zhao W, Hou X, Ma W, Xu Z, Zheng Z, Sun W, Lan L, Zhang W, Mu X, Shi C, Wang Z, Lee J, Jin Z, Lin M, Jin H, Zhang L, Guo J, Zhao B, Ren Z, Wang S, Xu W, Wang X, Wang J, You Z, Dong J. AI-assisted CT imaging analysis for COVID-19 screening: building and deploying a medical AI system. Appl Soft Comput. 2021 Jan;98:106897. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2020.106897. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33199977 .S1568-4946(20)30835-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strohm L, Hehakaya C, Ranschaert ER, Boon WP, Moors EH. Implementation of artificial intelligence (AI) applications in radiology: hindering and facilitating factors. Eur Radiol. 2020 Oct;30(10):5525–32. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06946-y. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32458173 .10.1007/s00330-020-06946-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soltan AA, Yang J, Pattanshetty R, Novak A, Yang Y, Rohanian O, Beer S, Soltan MA, Thickett DR, Fairhead R, Zhu T, Eyre DW, Clifton DA. Real-world evaluation of rapid and laboratory-free COVID-19 triage for emergency care: external validation and pilot deployment of artificial intelligence driven screening. Lancet Digit Health. 2022 Apr;4(4):e266–78. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00272-7. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2589-7500(21)00272-7 .S2589-7500(21)00272-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sohn JH, Chillakuru YR, Lee S, Lee AY, Kelil T, Hess CP, Seo Y, Vu T, Joe BN. An open-source, vender agnostic hardware and software pipeline for integration of artificial intelligence in radiology workflow. J Digit Imaging. 2020 Aug;33(4):1041–6. doi: 10.1007/s10278-020-00348-8. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32468486 .10.1007/s10278-020-00348-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pierce JD, Rosipko B, Youngblood L, Gilkeson RC, Gupta A, Bittencourt LK. Seamless integration of artificial intelligence into the clinical environment: our experience with a novel pneumothorax detection artificial intelligence algorithm. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 Nov;18(11):1497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2021.08.023.S1546-1440(21)00741-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanakaraj P, Ramadass K, Bao S, Basford M, Jones LM, Lee HH, Xu K, Schilling KG, Carr JJ, Terry JG, Huo Y, Sandler KL, Netwon AT, Landman BA. Workflow integration of research AI tools into a hospital radiology rapid prototyping environment. J Digit Imaging. 2022 Aug;35(4):1023–33. doi: 10.1007/s10278-022-00601-2. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/35266088 .10.1007/s10278-022-00601-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jauk S, Kramer D, Großauer B, Rienmüller S, Avian A, Berghold A, Leodolter W, Schulz S. Risk prediction of delirium in hospitalized patients using machine learning: an implementation and prospective evaluation study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 Jul 01;27(9):1383–92. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa113. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32968811 .5910737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis SE, Greevy RA, Fonnesbeck C, Lasko TA, Walsh CG, Matheny ME. A nonparametric updating method to correct clinical prediction model drift. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019 Dec 01;26(12):1448–57. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz127. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31397478 .5545426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blezek DJ, Olson-Williams L, Missert A, Korfiatis P. AI integration in the clinical workflow. J Digit Imaging. 2021 Dec;34(6):1435–46. doi: 10.1007/s10278-021-00525-3. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34686923 .10.1007/s10278-021-00525-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pantanowitz L, Quiroga-Garza GM, Bien L, Heled R, Laifenfeld D, Linhart C, Sandbank J, Albrecht Shach A, Shalev V, Vecsler M, Michelow P, Hazelhurst S, Dhir R. An artificial intelligence algorithm for prostate cancer diagnosis in whole slide images of core needle biopsies: a blinded clinical validation and deployment study. Lancet Digit Health. 2020 Aug;2(8):e407–16. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30159-X. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2589-7500(20)30159-X .S2589-7500(20)30159-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fujimori R, Liu K, Soeno S, Naraba H, Ogura K, Hara K, Sonoo T, Ogura T, Nakamura K, Goto T. Acceptance, barriers, and facilitators to implementing artificial intelligence-based decision support systems in emergency departments: quantitative and qualitative evaluation. JMIR Form Res. 2022 Jun 13;6(6):e36501. doi: 10.2196/36501. https://formative.jmir.org/2022/6/e36501/ v6i6e36501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pou-Prom C, Murray J, Kuzulugil S, Mamdani M, Verma AA. From compute to care: lessons learned from deploying an early warning system into clinical practice. Front Digit Health. 2022;4:932123. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2022.932123. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/36133802 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baxter SL, Bass JS, Sitapati AM. Barriers to implementing an artificial intelligence model for unplanned readmissions. ACI Open. 2020 Jul;4(2):e108–13. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1716748. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33274314 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sandhu S, Lin AL, Brajer N, Sperling J, Ratliff W, Bedoya AD, Balu S, O'Brien C, Sendak MP. Integrating a machine learning system into clinical workflows: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Nov 19;22(11):e22421. doi: 10.2196/22421. https://www.jmir.org/2020/11/e22421/ v22i11e22421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sendak MP, Ratliff W, Sarro D, Alderton E, Futoma J, Gao M, Nichols M, Revoir M, Yashar F, Miller C, Kester K, Sandhu S, Corey K, Brajer N, Tan C, Lin A, Brown T, Engelbosch S, Anstrom K, Elish MC, Heller K, Donohoe R, Theiling J, Poon E, Balu S, Bedoya A, O'Brien C. Real-world integration of a sepsis deep learning technology into routine clinical care: implementation study. JMIR Med Inform. 2020 Jul 15;8(7):e15182. doi: 10.2196/15182. https://medinform.jmir.org/2020/7/e15182/ v8i7e15182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang F, Preininger A. AI in health: state of the art, challenges, and future directions. Yearb Med Inform. 2019 Aug;28(1):16–26. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1677908. http://www.thieme-connect.com/DOI/DOI?10.1055/s-0039-1677908 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li JP, Liu H, Ting DS, Jeon S, Chan RV, Kim JE, Sim DA, Thomas PB, Lin H, Chen Y, Sakomoto T, Loewenstein A, Lam DS, Pasquale LR, Wong TY, Lam LA, Ting DS. Digital technology, tele-medicine and artificial intelligence in ophthalmology: a global perspective. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2021 May;82:100900. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100900. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32898686 .S1350-9462(20)30072-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sibbald M, Zwaan L, Yilmaz Y, Lal S. Incorporating artificial intelligence in medical diagnosis: a case for an invisible and (un)disruptive approach. J Eval Clin Pract. 2024 Feb;30(1):3–8. doi: 10.1111/jep.13730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ehsani-Moghaddam B, Martin K, Queenan JA. Data quality in healthcare: a report of practical experience with the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network data. Health Inf Manag. 2021;50(1-2):88–92. doi: 10.1177/1833358319887743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Enablers and barriers identified in previous reviews.

Search strategies across 4 databases for this review.

Quality assessment of the included studies.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).