This cohort study uses latent growth curve modeling to analyze associations of personality, social factors, brain functioning, and family history with alcohol misuse over time among adolescents in Europe.

Key Points

Question

Are there differential associations of personality, social factors, brain functioning, and familial risk with alcohol misuse (AM) trajectories in adolescents?

Findings

In this cohort study of 2040 adolescents that investigated alcohol misuse trajectories over the course of 8 years, psychosocial resources (lower frequency of life events realted to family and sexuality and higher socioeconomic status) were initially associated with a lower general risk for alcohol misuse but with an increased risk over the course of 8 years. Personality characteristics (higher impulsivity, risk-taking, and extraversion) were associated with a higher risk of alcohol misuse on average, as well as a higher risk for alcohol misuse development; there was no association with brain functioning.

Meaning

These findings indicate that known risk factors contribute differentially to future AM, which may inform individualized interventions.

Abstract

Importance

The development of an alcohol use disorder in adolescence is associated with increased risk of future alcohol dependence. The differential associations of risk factors with alcohol use over the course of 8 years are important for preventive measures.

Objective

To determine the differential associations of risk-taking aspects of personality, social factors, brain functioning, and familial risk with hazardous alcohol use in adolescents over the course of 8 years.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The IMAGEN multicenter longitudinal cohort study included adolescents recruited from European schools in Germany, the UK, France, and Ireland from January 2008 to January 2019. Eligible participants included those with available neuropsychological, self-report, imaging, and genetic data at baseline. Adolescents who were ineligible for magnetic resonance imaging or had serious medical conditions were excluded. Data analysis was conducted from July 2021 to September 2022.

Exposure

Personality testing, psychosocial factors, brain functioning, and familial risk of alcohol misuse.

Main Outcome and Measures

Hazardous alcohol use as measured with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test scores, a main planned outcome of the IMAGEN study. Alcohol misuse trajectories at ages 14, 16, 19, and 22 years were modeled using latent growth curve models.

Results

A total of 2240 adolescents (1110 female [49.6%] and 1130 male [50.4%]) were included in the study. There was a significant negative association of psychosocial resources (β = −0.29; SE = 0.03; P < .001) with the general risk of alcohol misuse as well as a significant positive association of the risk-taking aspects of personality with the intercept (β = 0.19; SE = 0.04; P < .001). Furthermore, there were significant positive associations of the social domain (β = 0.13; SE = 0.02; P < .001) and the personality domain (β = 0.07; SE = 0.02; P < .001) with trajectories of alcohol misuse development over time (slope). Family history of substance misuse was negatively associated with general risk of alcohol misuse (β = −0.04; SE = 0.02; P = .045) and its development over time (β = −0.03; SE = 0.01; P = .01). Brain functioning showed no significant association with intercept or slope of alcohol misuse in the model.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this cohort study suggest known risk factors of adolescent drinking may contribute differentially to future alcohol misuse. This approach may inform more individualized preventive interventions.

Introduction

The worldwide lifetime prevalence of alcohol use is 80% and 10.7% for alcohol use disorder (AUD),1 suggesting that only a portion of users develop AUD. In young adolescents, rates of weekly alcohol use vary between 9% and 16%,2 and alcohol use in adolescence may result in physical injury, high-risk sexual behavior, long-term adverse neurocognitive effects, and an enhanced risk of developing AUD in adult life.3 Therefore, early identification of risk factors is crucial to develop interventions to prevent AUD. The most relevant risk factors are reward-related brain functioning, genetics, personality, and social factors.4 Personality and social environment factors, including parental drinking and parental provision of alcohol, are associated with alcohol misuse in early adolescence and in the development of adolescent alcohol use.5,6 Peer and parental influences on alcohol misuse seem to decrease in adulthood, whereas environmental factors seem to change over time.7 In a recent study examining markers of binge drinking,8 the neuropsychosocial and the psychosocial model outperformed the neural model for predicting risky drinking behaviors. While functional and structural brain measures are associated with alcohol use,9 these factors demonstrated modest utility, and the development of a neuroimaging risk score to yield targeted interventions is ongoing.9 Still, a comprehensive review on the imaging genetics results of the IMAGEN study by Mascarell Maričić et al10 found various effects of genetics on intermediate phenotypes. Therefore, the aim of the current study is to quantify the risk for alcohol misuse and subsequent dependency with respect to such intermediate phenotypes and associated domains for the first time in a longitudinal design with participants aged 14 to 22 years in the IMAGEN sample.

Methods

In this cohort study, we used baseline data from participants from the longitudinal IMAGEN cohort11 that started with 14-year-old students from 8 sites in Germany, the UK, France, and Ireland. All local ethics research committees approved the study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.12 This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. Verbal or written consent was obtained from the parent or guardian and the participants depending on their age. Participants were recruited in schools with a maximization of ethnic homogeneity of European descent and sample diversity regarding sociodemographic variables and behavioral and emotional functioning. Exclusion criteria were ineligibility for magnetic resonance imaging scans and serious medical conditions. Alcohol misuse trajectories were assessed at 4 consecutive time points (14, 16, 19, and 22 years) with the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; self-report version) and modeled using latent growth curve models (LGCM). Exposure variables were preselected based on publications4,5,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 regarding risk and resilience factors associated with alcohol misuse in adolescents and young adults. We aimed to cover a broad variety of domains, namely personality, social, and brain functioning characteristics, and familial risk for substance misuse. All assessments are listed in Table 1 and described in the eMethods in Supplement 1.

Table 1. Factors Associated With Alcohol Misuse According to Domains Assessed at Baseline and Respective Instruments.

| Domain | Measures | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Personality | Temperament and Character Inventory-Revised (TCI-R; novelty seeking subscale) | Impulsivity |

| Neuroticism-Extraversion-Openness Personality Inventory-Revised (NEO-PI-R) | Extraversion | |

| Cambridge Guessing Task (CGT; from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery [CANTAB]) | Risk taking | |

| Social factors | Parental socioeconomic status | |

| Life Events Questionnaire (LEQ) | Frequencies of life events in family and sexuality domains | |

| Brain functioning | Monetary incentive delay task (MID) | Reward outcome, reward anticipation, ventral striatum, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex |

| Family history | Familial risk for substance misuse | Family history of alcohol misuse and/or drug misuse |

Statistical Analyses

We used LGCM to analyze longitudinal within-participant as well as between-participant changes in alcohol misuse. LGCM analyses were conducted using Ωnyx (von Oertzen et al21) and descriptive analyses were conducted using SPSS version 28 (IBM).

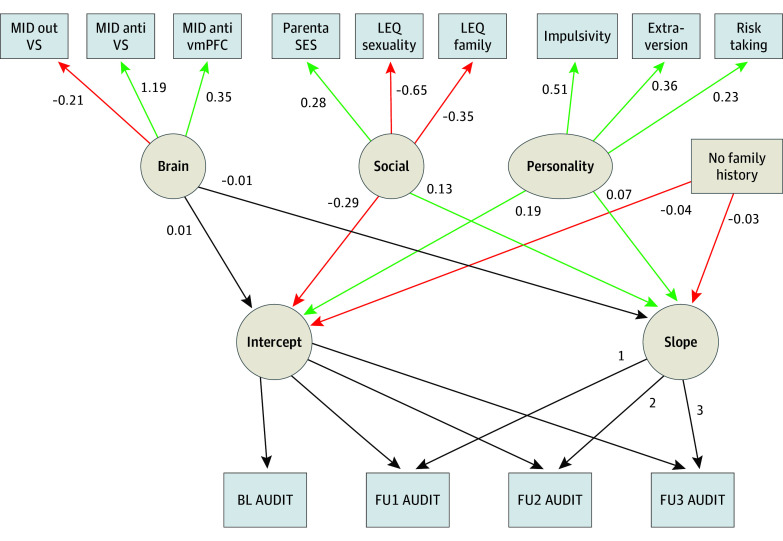

The LGCM (Figure 1) contained individual changes in AUDIT scores (within-person variability) and exposure variables associated with alcohol misuse (between-person variability). The modeled intercepts and slopes represent the individual 8-year trajectory of alcohol misuse, and the exposure variables allow for analysis of interindividual associations of these variables with misuse trajectories.

Figure 1. Latent Growth Curve Model.

Green paths show statistically significant positive associations and red paths show statistically significant negative associations. AUDIT indicates Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; BL, baseline; FU, follow-up; LEQ, Live Events Questionnaire; MID, monetary incentive delay; SES, socioeconomic status; vmPFC, ventromedial prefrontal cortex; VS, ventral striatum.

To address domain-specific dependency of the exposure variables, the brain, social, and personality domains were treated as latent factors in the model. Estimate parameters of the 4 exposure variables (ie, brain, social, personality, and family history) were statistically compared analogously to Clogg and colleagues22 and corrected for multiple testing.

Freely estimated covariances were allowed between all exposure variables (3 latent factors and family history). Maximum likelihood was used to estimate parameters, and a linear trajectory of AUDIT scores was assumed, which was verified by comparing the model fit to an analogous quadratic model and a model without time trend using Akaike information criterion (AIC). Models with higher AIC scores were considered to fit the time trend of observed AUDIT scores better.23 Missing data was handled with full information maximum likelihood. Small effect sizes were defined as an r value greater than 0.10 and less than 0.30.24 A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. For the multiple comparisons of the etsimate parameters, the Bonferroni correction was used to adjust the significance level to P < .004. Data analysis was conducted from July 2021 to September 2022.

Results

Sample characteristics including descriptive statistics on all analyzed variables are displayed in Table 2. The sample comprised 2240 participants (1110 female [49.6%] and 1130 male [50.4%]). Alcohol misuse (AUDIT) was measured in 2209 participants (98.6%) at study baseline (14 years), in 1698 (75.8%) participants at follow-up 1 (16 years; 511 participants [23.1%] dropped out from baseline), in 1511 participants (67.5%) at follow-up 2 (19 years; 729 participants [31.6%] dropped out from baseline) and in 1359 participants (60.7%) at follow-up 3 (22 years; 881 participants [38.5%] dropped out from baseline).

Table 2. Sample Characteristics.

| Characteristics | Observations, No. (%) (N = 2240) | Score, mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1110 (49.6) | NA |

| Male | 1130 (50.4) | NA |

| Family history (cluster with familial risk), No./total No. (%) | 1187/2235 (53.0) | NA |

| Baseline assessments (14 y) | ||

| MID: Outcome phase (ventral striatal activation) | 1892 (84.5) | −0.24 (1.12) |

| MID: Anticipation phase (ventral striatal activation) | 1942 (86.7) | 0.22 (0.34) |

| MID: Anticipation phase (ventromedial prefrontal cortex activation) | 1942 (86.7) | 0.03 (0.62) |

| Parental socioeconomic status | 2240 (100.0) | 17.74 (3.86) |

| LEQ: sexuality domain (frequency score) | 2240 (100.0) | 0.29 (0.18) |

| LEQ: family domain (frequency score) | 2240 (100.0) | 0.26 (0.22) |

| Impulsivity | 2206 (98.5) | 26.79 (4.86) |

| Extraversion | 2240 (100.0) | 2.50 (0.46) |

| Risk taking | 2240 (100.0) | 0.55 (0.13) |

| Alcohol misuse (AUDIT) | 2209 (98.6) | 1.50 (2.67) |

| Follow-up | ||

| 1: AUDIT, 16 y | 1698 (75.8) | 3.72 (3.48) |

| 2: AUDIT, 19 y | 1511 (67.5) | 5.64 (4.19) |

| 3: AUDIT, 22 y | 1359 (60.7) | 6.12 (4.64) |

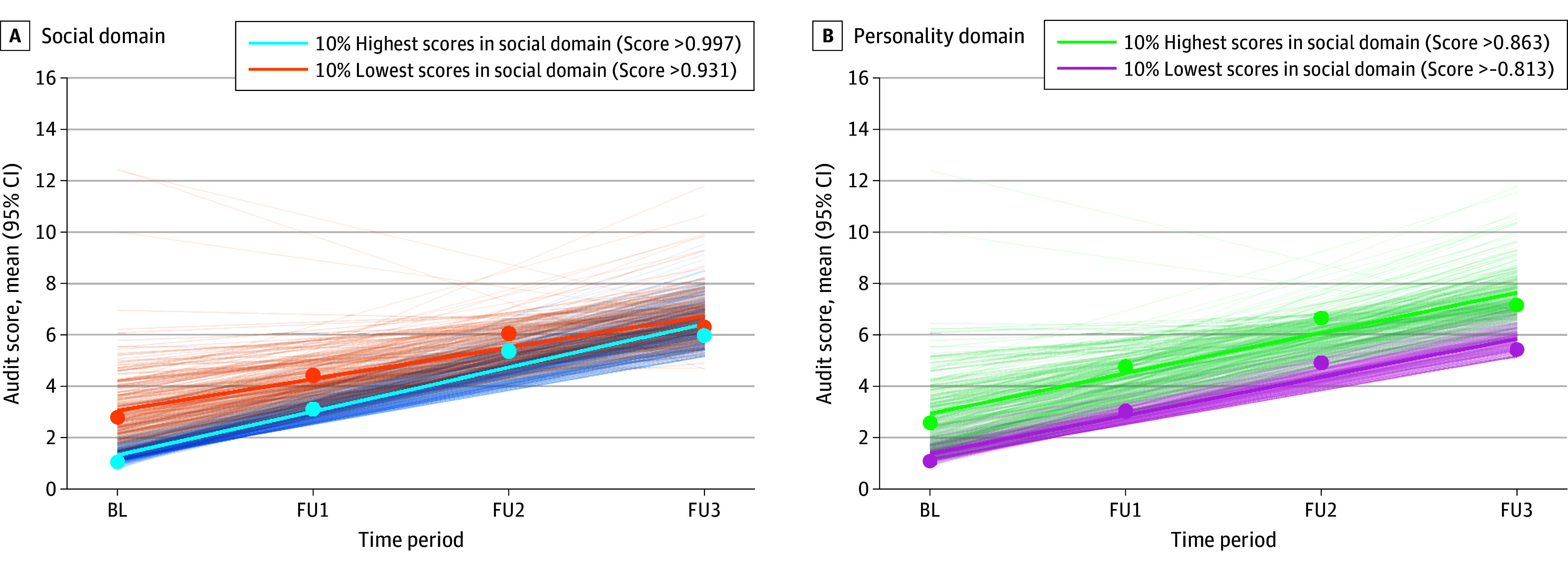

Abbreviations: AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; LEQ, live events questionnaire; MID, monetary incentive delay; NA, not applicable.

The linear model showed an acceptable and better23 model fit in comparison with a quadratic model (−2 log likelihood ratio = 15.85; AIClinear = 77 694.85; AICquadratic = 77 710.70 and a better model fit in comparison with a model with no time trend (−2 log likelihood ratio = 222.73; AIClinear = 77 694.85; AICno-time-trend = 77 917.57) (Table 3). Regarding the factor paths (Table 3 and the eTable in Supplement 1), we found a significant negative association of the social domain with the intercept of alcohol misuse (β = −0.29; SE = 0.03; P < .001) and a significant positive association of the personality domain with the intercept (β = 0.19; SE = 0.03; P < .001), both of which had small effect sizes. Furthermore, there were significant positive associations of the social domain (β = 0.13; SE = 0.02; P < .001) and personality domains (β = 0.07; SE = 0.02; P < .001) with the slope of developmental trajectories of alcohol misuse, although these were small effect sizes. Family history also showed significant negative associations with the alcohol misuse intercept (β = −0.04; SE = 0.02; P = .045) and slope (β = −0.03; SE = 0.01; P = .01), but corresponding r coefficients suggested correlations beneath the threshold for a small effect size (Table 3). The latent factor, brain functioning, showed no association with intercept or slope of alcohol misuse. The 4 intercept estimates as well as the 4 slope estimates differed significantly (also after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing). Thus, social domain scores showed significantly larger-magnitude associations with the intercept and slope of alcohol misuse trajectories compared with the personality domain scores, which showed significantly larger-magnitude associations compared with the brain domain scores and family history of substance abuse. Figure 2A illustrates that higher social scores (higher socioeconomic status and lower frequency of life events related to family and sexuality) were associated with higher scores of alcohol misuse at baseline but were also associated with a greater slope over 8 years. Figure 2B shows that higher risk-taking aspects of personality were associated with higher scores of alcohol misuse at baseline, as well as a greater increase (slope) over 8 years.

Table 3. Intercept and Slope Model Estimates and Effect Sizes for the Brain, Social, Personality, and Family History Domains and Their Association With Alcohol Misuse.

| Domain | Intercept of alcohol misusea | Slope of alcohol misusea | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | Z | P value | r | β (SE) | Z | P value | r | |

| Brain | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.54 | .59 | 0.06 | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.91 | .36 | −0.01 |

| Social | −0.29 (0.03) | −8.72 | <.001 | −0.29b | 0.13 (0.02) | 7.39 | <.001 | 0.18b |

| Personality | 0.19 (0.04) | 4.90 | <.001 | 0.24b | 0.07 (0.02) | 3.61 | <.001 | 0.12b |

| Family history | −0.04 (0.02) | −2.00 | .045 | −0.04 | −0.03 (0.01) | −2.50 | .01 | −0.03 |

Latent growth curve model parameters: model fit: χ265 = 258.74; P < .001; comparative fit index = 0.92; root mean square error of approximation = 0.04; standardized root mean squared residual = 0.03.

Values greater than 0.10 and less than 0.30 indicate a small effect size.

Figure 2. Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) Trajectories Visualized as Linear Regression Lines Based on AUDIT Raw Scores Grouped for Highest and Lowest Domain Scores.

A, The 10% highest and lowest scores in the social domain (socioeconomic status [SES] and life events); higher scores correspond to higher SES and lower frequency of life events related to family and sexuality. B, The 10% highest and lowest scores in the personality domain (impulsivity, extraversion, and risk-taking); higher scores correspond to higher impulsivity, extraversion, and risk-taking. Points indicate AUDIT group mean scores for each time point. Bold lines indicate mean regression lines based on AUDIT raw scores. Thin lines indicate individual regression lines based on AUDIT raw scores. BL indicates baseline; FU, follow-up.

Discussion

In this cohort study, we aimed to investigate the differential association of various domains with alcohol misuse trajectories from adolescence to young adulthood. The results of our final model indicate that psychosocial resources—indexed by lower frequency of life events related to family and sexuality, together with higher socioeconomic status—were initially associated with a lower general risk for alcohol misuse (intercept) but with increased alcohol misuse over the course of 8 years (slope). At the same time, personality characteristics—specifically higher impulsivity, risk-taking and extraversion scores—were associated with a higher risk of alcohol misuse on average, as well as a higher risk for alcohol misuse development over 8 years (slope). This finding suggests an influence of personality features on the general risk regarding alcohol misuse and on the development of alcohol misuse from adolescence to young adulthood. The absence of family history was significantly associated with a lower general risk and a decrease in alcohol misuse over time, with estimates below the threshold for a small effect size, which cannot be interpreted as meaningful. In earlier analyses of IMAGEN data,10,11 we saw a differential association of reward-related brain functioning at baseline with alcohol misuse 2 years later depending on family history of substance abuse.13 This finding suggests that family history of substance abuse and reward-system functioning may influence the course of adolescent alcohol misuse, specifically in certain combinations. Therefore, a possible mediating role of familial risk of the influence of reward processing on the course of alcohol misuse should be further investigated. Overall, the present analysis suggests a comparably large general association of social and personality factors with adolescent alcohol misuse that outweighs reward-system functioning and the individual familial risk. Thus, the risk of developing an alcohol addiction might primarily be influenced by social factors that in large parts are associated with the adolescent’s family as well as personality factors. Also, it has been shown that social and language functional magnetic resonance imaging tasks discriminate well on a neural level, suggesting that a broader range of brain processes might be associated with binge drinking in late adolescence.8

Strengths and Limitations

The strength of the present study lies in our use of rich longitudinal data collected by the IMAGEN project to track the differential association of a diverse range of established factors with alcohol abuse over a broad neurodevelopmental window in a large sample. There were limitations to the study as well. First, limitations concern a selective bias due to dropouts that might have contributed to an underestimation of alcohol misuse.25 Second, alcohol misuse was only obtained via self-report; no external validation was administered. Third, as of yet, we have no information about whether participants with risky drinking trajectories will develop AUD in later life. Fourth, statistically the model showed an acceptable, but not a good fit, which is still highly informative for the field and future analyses.

Conclusions

This cohort study found an association of social and personality factors with adolescent alcohol misuse compared with reward-related brain functioning and family history. This finding suggests that known risk factors for adolescent drinking may contribute differently to future alcohol misuse. This approach may inform more individualized preventive interventions.

eMethods. Description of Assessments

eTable. Paths Estimates of Predictor Domains (Social, Personality, Brain)

eReferences

Nonauthor Collaborators

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Glantz MD, Bharat C, Degenhardt L, et al. ; WHO World Mental Health Survey Collaborators . The epidemiology of alcohol use disorders cross-nationally: findings from the World Mental Health Surveys. Addict Behav. 2020;102:106128. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Looze Md, Raaijmakers Q, Bogt TT, et al. Decreases in adolescent weekly alcohol use in Europe and North America: evidence from 28 countries from 2002 to 2010. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(Suppl 2)(suppl 2):69-72. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sartor CE, Jackson KM, McCutcheon VV, et al. Progression from first drink, first intoxication, and regular drinking to alcohol use disorder: a comparison of African American and European American youth. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(7):1515-1523. doi: 10.1111/acer.13113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whelan R, Watts R, Orr CA, et al. ; IMAGEN Consortium . Neuropsychosocial profiles of current and future adolescent alcohol misusers. Nature. 2014;512(7513):185-189. doi: 10.1038/nature13402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heinrich A, Müller KU, Banaschewski T, et al. ; IMAGEN consortium . Prediction of alcohol drinking in adolescents: Personality-traits, behavior, brain responses, and genetic variations in the context of reward sensitivity. Biol Psychol. 2016;118:79-87. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2016.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yap MBH, Cheong TWK, Zaravinos-Tsakos F, Lubman DI, Jorm AF. Modifiable parenting factors associated with adolescent alcohol misuse: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Addiction. 2017;112(7):1142-1162. doi: 10.1111/add.13785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meque I, Salom C, Betts KS, Alati R. Predictors of alcohol use disorders among young adults: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2019;54(3):310-324. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agz020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gowin JL, Manza P, Ramchandani VA, Volkow ND. Neuropsychosocial markers of binge drinking in young adults. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(9):4931-4943. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-0771-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Halloran L, Nymberg C, Jollans L, Garavan H, Whelan R. The potential of neuroimaging for identifying predictors of adolescent alcohol use initiation and misuse. Addiction. 2017;112(4):719-726. doi: 10.1111/add.13629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mascarell Maričić L, Walter H, Rosenthal A, et al. ; IMAGEN consortium . The IMAGEN study: a decade of imaging genetics in adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(11):2648-2671. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-0822-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schumann G, Loth E, Banaschewski T, et al. ; IMAGEN consortium . The IMAGEN study: reinforcement-related behaviour in normal brain function and psychopathology. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(12):1128-1139. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tschorn M, Lorenz RC, O’Reilly PF, et al. ; IMAGEN Consortium . Differential predictors for alcohol use in adolescents as a function of familial risk. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):157. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01260-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nees F, Tzschoppe J, Patrick CJ, et al. ; IMAGEN Consortium . Determinants of early alcohol use in healthy adolescents: the differential contribution of neuroimaging and psychological factors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):986-995. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castellanos-Ryan N, Struve M, Whelan R, et al. ; IMAGEN Consortium . Neural and cognitive correlates of the common and specific variance across externalizing problems in young adolescence. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(12):1310-1319. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13111499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill SY, Shen S, Lowers L, Locke J. Factors predicting the onset of adolescent drinking in families at high risk for developing alcoholism. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(4):265-275. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00841-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuckit MA, Smith TL. An 8-year follow-up of 450 sons of alcoholic and control subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(3):202-210. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030020005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood PK, Brent EE. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100(4):427-448. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robbins TW, Gillan CM, Smith DG, de Wit S, Ersche KD. Neurocognitive endophenotypes of impulsivity and compulsivity: towards dimensional psychiatry. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16(1):81-91. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stolle M, Sack PM, Thomasius R. Binge drinking in childhood and adolescence: epidemiology, consequences, and interventions. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106(19):323-328. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0595b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Oertzen T, Brandmaier AM, Tsang S. Structural equation modeling with Ωnyx. Struct Equ Modeling. 2015;22(1):148-161. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2014.935842 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clogg CC, Petkova E, Haritou A. Statistical methods for comparing regression coefficients between models. Am J Sociol. 1995;100(5):1261-1293. doi: 10.1086/230638 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakamoto Y, Ishiguro M, Kitagawa G. Akaike information criterion statistics. D. Reidel Publishing; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavior Sciences. 2nd ed. Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snow DL, Tebes JK, Arthur MW. Panel attrition and external validity in adolescent substance use research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60(5):804-807. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.60.5.804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Description of Assessments

eTable. Paths Estimates of Predictor Domains (Social, Personality, Brain)

eReferences

Nonauthor Collaborators

Data Sharing Statement