Abstract

An environmentally friendly, versatile multicomponent reaction for synthesizing isoxazol-5-one and pyrazol-3-one derivatives has been developed, utilizing a freshly prepared g-C3N4·OH nanocomposite as a highly efficient catalyst at room temperature in aqueous environment. This innovative approach yielded all the desired products with exceptionally high yields and concise reaction durations. The catalyst was well characterized by FT-IR, XRD, SEM, EDAX, and TGA/DTA studies. Notably, the catalyst demonstrated outstanding recyclability, maintaining its catalytic efficacy over six consecutive cycles without any loss. The sustainability of this methodology was assessed through various eco-friendly parameters, including E-factor and eco-score, confirming its viability as a green synthetic route in organic chemistry. Additionally, the gram-scale synthesis verifies its potential for industrial applications. The ten synthesized compounds were also analyzed via a PASS online tool to check their several pharmacological activities. The study is complemented by in silico molecular docking, pharmacokinetics, and molecular dynamics simulation studies. These studies discover 5D as a potential candidate for drug development, supported by its favorable drug-like properties, ADMET studies, docking interaction, and stable behavior in the protein binding cavity.

Keywords: g-C3N4·OH, Nano-catalyst, Isoxazol-5-ones, Pyrazol-3-ones, PASS online, Molecular docking, Pharmacokinetic properties, Molecular dynamics simulations

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Chemistry

Introduction

Heterocyclic chemistry, a pivotal branch of organic chemistry, explores the synthesis and properties of compounds containing one or more heteroatoms within their ring structure1. These heteroatoms, such as nitrogen, oxygen, or sulfur, introduce unique chemical reactivity and diverse functionalities, making heterocycles integral in pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, materials science, and beyond2,3. In recent years, the principles of green chemistry have gained significant traction, aiming to minimize environmental impact and promote sustainability throughout the chemical synthesis process4,5. Green chemistry emphasizes the design of efficient, environmentally benign reactions that reduce waste generation, energy consumption, and the use of hazardous substances6,7. One notable strategy within green chemistry is the development of multi-component reactions (MCRs), which offer streamlined pathways for synthesizing complex molecules8. MCRs refer to the one-pot synthesis of molecules from three or higher starting materials with high yields, reduced reaction steps, and minimal waste production9–11. Integrating green chemistry principles with heterocyclic chemistry's versatility, multi-component reactions have emerged as powerful tools for accessing diverse molecular compositions with high efficiency and sustainability12. These reactions play a crucial role in modern organic synthesis, facilitating the rapid construction of structurally complex molecules for various applications in drug discovery, materials science, and chemical biology13,14.

Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) has attracted significant attention from researchers in the recent years15. Its stability, large surface area, and customizable electronic properties make it an excellent catalyst for various organic transformations, providing a sustainable alternative to metal-based catalysts16,17. Besides its established uses in catalysis, photocatalysis, and sensing, g-C3N4 has also emerged as an active catalyst for synthesizing fine chemicals and pharmaceutical intermediates, enabling multi-component reactions and selective transformations18,19. Graphitic carbon nitride modified with hydroxyl groups (g-C3N4·OH) is highly versatile and performs exceptionally well in aqueous environments. Its hydrophilicity, enhanced by hydroxyl groups, facilitates dispersion and stability in water-based systems20,21. This material's surface reactivity promotes specific interactions with target molecules, boosting catalytic activity in various chemical processes22,23. The ongoing research into synthesizing and applying g-C3N4·OH as a catalyst in the synthesis of heterocycles is poised to unlock further potential and drive continued innovation in this exciting field.

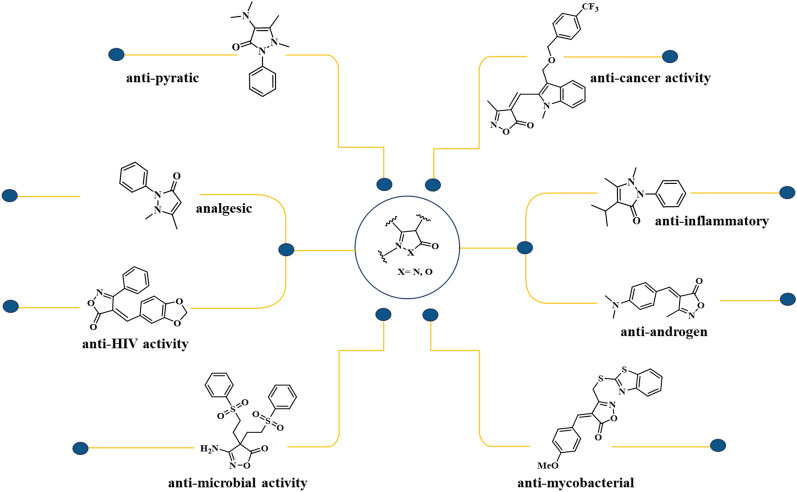

Isoxazol-5-ones and pyrazol-3-ones are heterocyclic compounds that have garnered significant attention in medicinal chemistry due to their diverse biological activities and structural versatility24,25. These scaffolds serve as key building blocks in the synthesis of bioactive molecules and pharmaceutical agents, owing to their unique structural features and pharmacological properties26. The isoxazole-5-one scaffold consists of a five-membered ring containing oxygen and nitrogen atoms adjacent to each other, while the pyrazol-3-one scaffold comprises a five-membered ring with adjacent nitrogen atoms27,28. These structural motifs offer opportunities for molecular recognition and interaction with biological targets, making them valuable templates for drug design and discovery29. Both isoxazole-5-one and pyrazol-3-one scaffolds have demonstrated a wide range of pharmacological activities, including antimicrobial, anticancer, anti-mycobacterium, anti-HIV, anti-obesity, anti-androgen, analgesic, and HDAC inhibitor properties, as represented in Fig. 130–32. Their efficacy in modulating biological pathways and targeting specific molecular targets has led to the development of numerous therapeutic agents across various disease areas. Despite the extensive research devoted to synthesize isoxazole-one and pyrazole-one scaffolds, a pressing need persists for a protocol that fully embodies the green chemistry matrix. Such a protocol would prioritize environmentally benign solvent systems, moderate operating temperatures, eco-friendly catalysts, and high product yields achieved within decent reaction times. This holistic approach is crucial for advancing sustainable synthetic methodologies and effectively meeting the demands of modern organic synthesis.

Figure 1.

Several biologically active drugs incorporate the isooxazol-5-one and pyrazol-3-one moiety.

Therefore, our study introduces a novel and eco-friendly approach for synthesizing these scaffolds, employing an efficient green catalyst, g-C3N4·OH. This catalyst, synthesized from urea and meticulously characterized, exhibits remarkable efficacy in the synthesis of isoxazol-one and pyrazol-one derivatives under mild conditions, notably in water at room temperature. Water as a solvent is vital in organic synthesis and green chemistry due to its non-toxic, environmentally friendly nature33. Its unique properties, such as high dielectric constant and hydrogen bonding, facilitate various reactions while reducing reliance on hazardous organic solvents and it promotes safer, more sustainable, and cost-effective chemical processes34,35.

Computer-aided drug design (CADD) revolutionizes medicinal chemistry by speeding up drug discovery, optimizing chemical structures, and predicting biological activity and side effects36. This technology reduces the time and cost of traditional methods, explores vast chemical spaces, and aids in developing safer and more effective therapeutics37,38.

Results and discussion

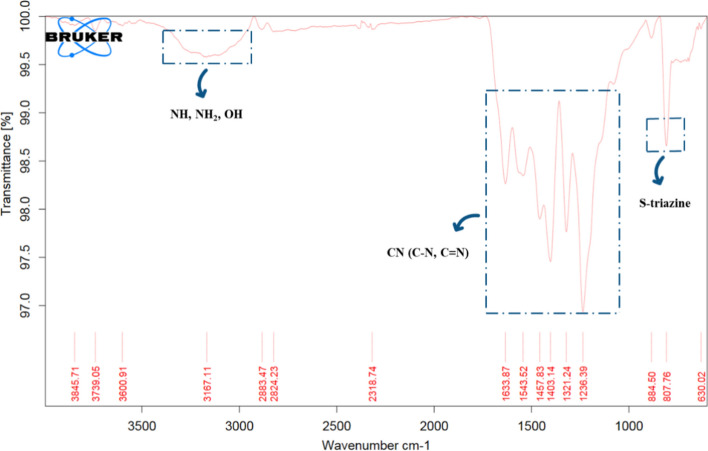

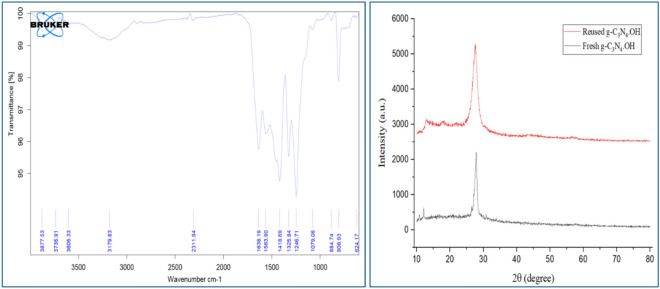

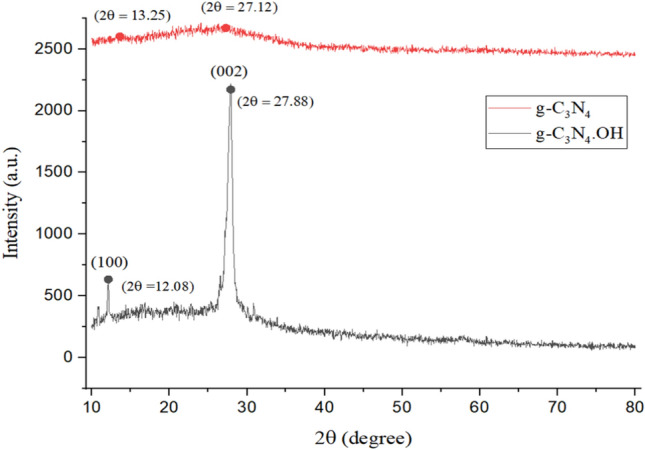

The synthesized g-C3N4·OH underwent comprehensive characterization through FTIR, XRD, FE-SEM, EDS and TGA/DTA studies, aligning with previous literature findings and affirming the successful synthesis of the catalyst20,21,39. XRD analysis revealed characteristic peaks: for g-C3N4, peaks were observed at 2θ = 13.25 (100 plane) and 27.12 (002 plane). Conversely, g-C3N4·OH displayed peaks at 2θ = 12.08 (100 plane) and 27.88 (002 plane), matching JCPDS card no. 87-1526, indicating that functionalization did not disrupt the CN wedge. The addition of hydroxyl groups exhibits negligible impact on the peak intensity observed in the XRD pattern of the catalyst. However, there is a discernible shift towards higher angles for the (002) crystal plane. This shift suggests that hydroxyl grafting results in a reduction of the interlayer spacing within the catalyst. Such a denser structure is likely attributed to electron localization and enhanced binding between the layers Fig. 2. FT-IR spectrum confirmed the presence of functional groups in g-C3N4·OH, with a notable triazine network stretching frequency at 807.76 cm–1 and peaks at 2950-3450 cm–1 corresponding to NH, NH2, and OH frequencies, ensuring g-C3N4·OH formation Fig. 3.

Figure 2.

Comparative XRD spectra of the synthesized g-C3N4 and g-C3N4·OH.

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of FT-IR spectra between synthesized g-C3N4 and g-C3N4·OH.

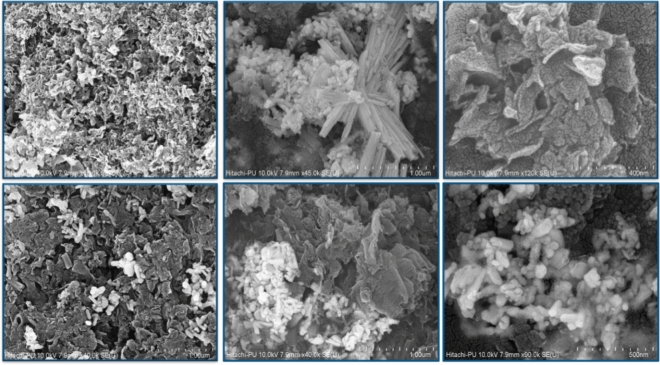

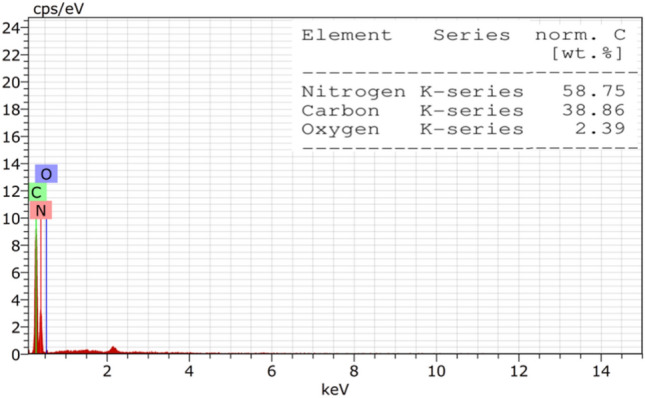

FE-SEM analysis at varying magnifications revealed a loosely wrinkled porous sheet-like structure, indicative of increased surface area, void presence, and stacked thin layers or sheets Fig. 4. EDX spectrum analysis of g-C3N4·OH exhibited elemental constituents: nitrogen (58.75), carbon (38.86), and oxygen (2.39), consistent with previous literature20,39, establishing a congruent composition of N, C, and O as main elements Fig. 5.

Figure 4.

FE-SEM images showcasing synthesized g-C3N4·OH at varying magnifications.

Figure 5.

Elemental composition analysis using EDX spectrum.

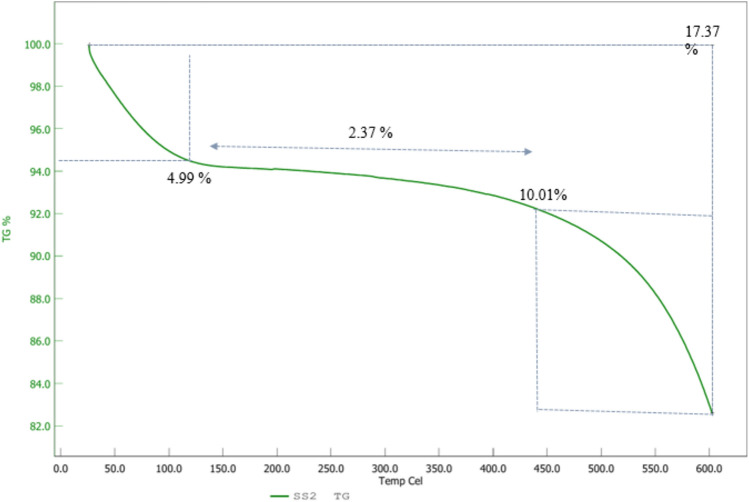

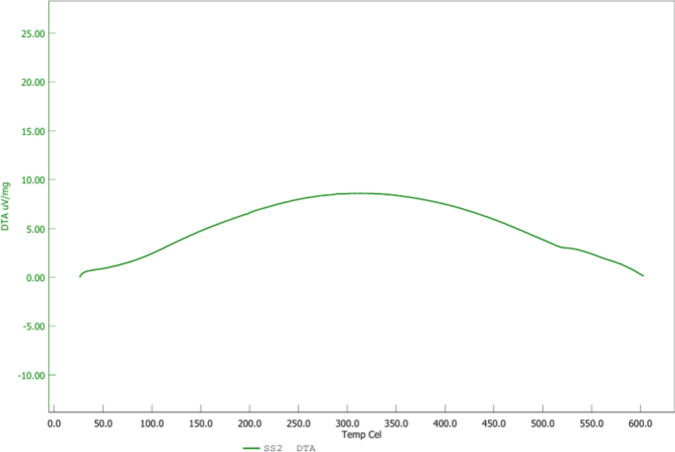

As depicted in Fig. 6 the TGA curve for g-C3N4·OH shows distinct weight loss stages. Initially, a 4.99% weight loss occurs around 120 °C, likely due to the evaporation of physically adsorbed water and volatile impurities. Between 120 °C and 440 °C, an additional 2.37% weight loss is observed, which can be attributed to the removal of hydroxyl groups (–OH) and decomposition of organic components or residual solvents. From 440 °C to 600 °C, a significant 10.01% weight loss occurs, indicative of the thermal decomposition of g-C3N4·OH itself, including the breakdown of its structure and loss of more stable organic components. Notably, only 17.37% of the compound was decomposed up to 600 °C, highlighting the excellent thermal stability of g-C3N4·OH. The DTA plot (Fig. 7) for g-C3N4·OH demonstrates an initial increase in the DTA signal from room temperature to 325 °C, indicating endothermic processes such as the evaporation of water and the decomposition of surface groups. Following this, the DTA signal decreases from 325 °C to 600 °C, indicating exothermic reactions likely due to the thermal breakdown of the material. This behavior suggests that the material absorbs heat initially for the removal of moisture and volatile components, and subsequently, it releases heat as it undergoes thermal degradation. The increase to 10 μV/mg followed by a decrease to 0 μV/mg highlights the distinct endothermic and exothermic phases of the thermal behavior of g-C3N4·OH.

Figure 6.

TGA analysis of g-C3N4·OH in N2 atmosphere at 10 ◦C/min up to 600 °C.

Figure 7.

DTA analysis of g-C3N4·OH conducted in N2 atmosphere at 10 ◦C/min up to 600 °C.

To refine the reaction conditions, we specifically selected 4-methylthiazole-5-carboxaldehyde, ethyl acetoacetate, and hydroxylamine hydrochloride as the key components for synthesizing 4-methyl thiazole-substituted methylene isoxazole-5-one, serving as our model reaction. Initially, we commenced the reaction without any catalyst at room temperature in water and also without any solvent but observed only minimal product formation (Table 1; entry 1, 2). Subsequently, we embarked on catalyst optimization, exploring a variety of readily available catalysts, including both acid and base types, with a 20 mg loading, while employing water as the solvent at ambient temperature (Table 1; entries 3-10). Unfortunately, the results did not meet our expectations. Turning our attention to synthesized g-C3N4 and g-C3N4.SO3H, previously synthesized in our laboratory, we achieved yields of 75% and 87%, respectively, under identical reaction conditions (Table 1; entry 11-12). Remarkably, utilizing g-C3N4·OH led to a substantial increase in product yield, reaching 91% within a 30-minute reaction time, marking our most successful outcome so far (Table 1; entry 13). Subsequent optimization of catalyst quantity, temperature, and solvent choice with g-C3N4·OH (Table 1; entry 14-20) revealed the optimal conditions: 15 mg catalyst loading at room temperature in water (Table 1; entry 14). Utilizing these optimized conditions, we proceeded to explore the substrate scope, incorporating a range of aliphatic and aromatic aldehydes. Subsequently, we diversified the hydroxylamine source, substituting it with phenyl-hydrazine and hydrazine hydrate, resulting in excellent yields. The notable advantages of g-C3N4·OH catalyst include its high catalytic efficiency, ease of synthesis, and compatibility with aqueous media, making it a promising candidate for sustainable and environmentally friendly synthetic methodologies.

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditions for the synthesis of 4-methyl thiazole-substituted methylene isoxazole-5-one as a model reaction. Significant values are in bold.

| S.N. | Catalyst | Catalyst loading | Medium | Temperature | Time | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | – | – | R.T. | > 48 h | – |

| 2 | – | – | H2O | R.T. | ~ 48 h | 12 |

| 3 | Acetic acid | 20 mg | H2O | R.T. | 24 h | 39 |

| 4 | p-Toluene- SO3H | 20 mg | H2O | R.T. | 10 h | 45 |

| 5 | Carbon- SO3H | 20 mg | H2O | R.T. | 12 h | 59 |

| 6 | Silica- SO3H | 20 mg | H2O | R.T. | 10 h | 60 |

| 7 | Chitosan-SO3H | 20 mg | H2O | R.T. | 8 h | 62 |

| 8 | Taurine | 20 mg | H2O | R.T. | 15 h | 53 |

| 9 | NaOH | 20 mg | H2O | R.T. | 12 h | 58 |

| 10 | Urea | 20 mg | H2O | R.T. | 10 h | 67 |

| 11 | g-C3N4 | 20 mg | H2O | R.T. | 8 h | 75 |

| 12 | g-C3N4.SO3H | 20 mg | H2O | R.T. | 2 h | 87 |

| 13 | g-C3N4·OH | 20 mg | H2O | R.T. | 30 min | 95 |

| 14 | g-C3N4·OH | 15 mg | H2O | R.T. | 30 min | 95 |

| 15 | g-C3N4·OH | 10 mg | H2O | R.T. | 45 min | 94 |

| 16 | g-C3N4·OH | 15 mg | H2O | 80 °C | 30 min | 92 |

| 17 | g-C3N4·OH | 15 mg | H2O | 100 °C | 30 min | 89 |

| 18 | g-C3N4·OH | 15 mg | H2O: EtOH | R.T. | 30 min | 90 |

| 19 | g-C3N4·OH | 15 mg | EtOH | R.T. | 1 h | 92 |

| 20 | g-C3N4·OH | 15 mg | – | R.T. | 2 h | 83 |

Following synthesis, the products underwent purification via column chromatography and were subsequently characterized using 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy to confirm the structure of the compounds, ensuring the integrity and accuracy of our findings.

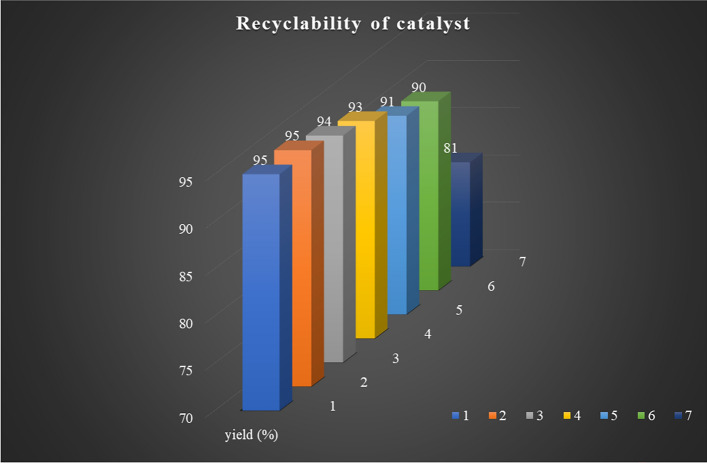

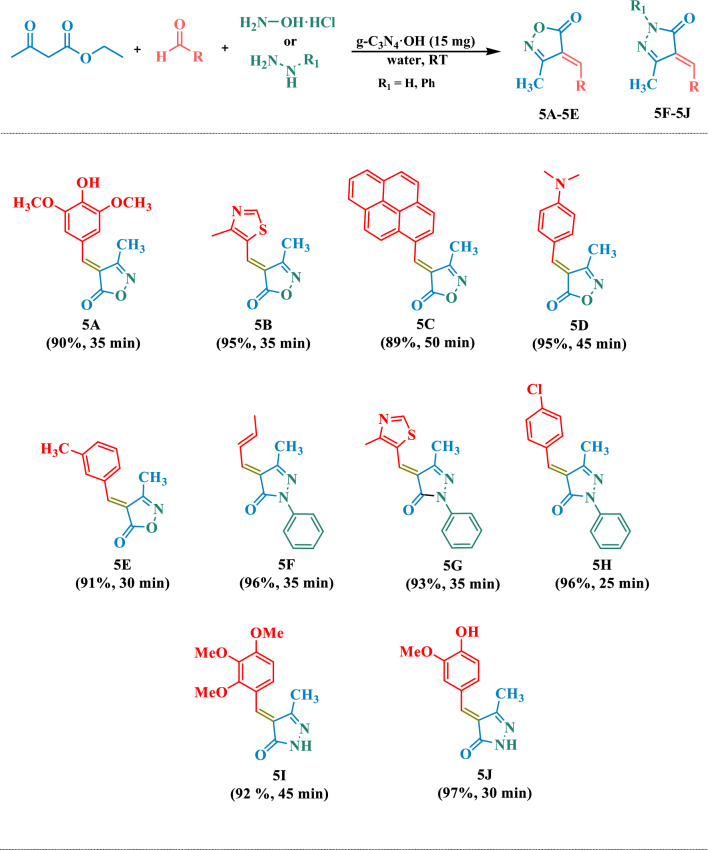

Following the optimization of all reactions, we investigated the reusability of the catalyst in the model reactions over multiple runs. The results are presented in Fig. 8. Remarkably, the synthesized g-C3N4·OH demonstrated impressive reusability, maintaining its catalytic activity over six consecutive cycles without any discernible loss, as confirmed by FT-IR and XRD studies (Fig. 9). To explore the versatility of the optimized reaction, its efficiency was further evaluated for synthesizing various derivatives as shown in Table 2. The efficacy of the protocol was further examined through a comparative analysis between the current study and prior research efforts as shown in Table 3.

Figure 8.

Assessing the sustainability of the g-C3N4·OH catalyst through recyclability studies.

Figure 9.

The comparative spectral analysis of FT-IR and XRD of both freshly synthesized and recycled catalyst.

Table 2.

Compilation of synthesized isoxazol-5-one/pyrazol-3-one derivatives.

Table 3.

The comparative investigation of synthesizing the Isoxazol-5-one/Pyrazol-3-one scaffold using the current method with reported methods.

| S. no. | Catalyst | Condition | Time | Yield (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fe3O4@MAP-SO3H NPs (20 mg) | EtOH-H2O, 25 °C, U.S. | 20-30 min | 85-92 | 40 |

| 2 | DMAP, (8 mol%) | EtOH:H2O (1:1) | 20-80 min | 86-98 | 41 |

| 3 | Sulfamic acid (15 mol%) | EtOH:H2O (1:1), reflux | 1-4 h | 58-92 | 42 |

| 4 | CuI@Met-β‐ CD (2%wt) | Water, 50 °C | 1-20 min | 80-97 | 43 |

| 5 | Piperidine (1 mL) | EtOH, R.T. | 24 h | 70-97 | 44 |

| 6 | g-C3N4·OH (15 mg) | Water, R.T. | 25-45 min | 89-97 | This work |

Significant values are in bold.

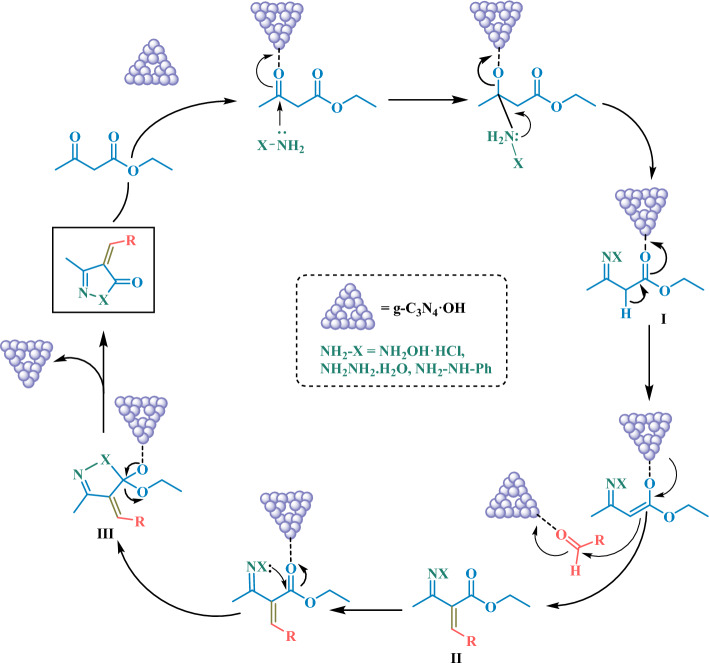

Based on the literature40,45, a plausible mechanism for the proposed reaction is depicted in Scheme 1 g-C3N4·OH in water served as a catalyst, facilitating the generation of a hydronium ion that accelerated the reaction, likely through the formation of an active cationic species. In this proposed mechanism, ethyl acetoacetate and a NH2-bearing compound (second reactant) underwent reaction in water solvent, leading to the expected formation of an oxime intermediate (I). This intermediate subsequently underwent Knoevenagel condensation with an activated aldehyde, yielding intermediate (II). Following this, intramolecular cyclization among hydroxyl and carbonyl groups occured, resulting in the formation of intermediate (III). Finally, intermediate (III) eliminated an ethanol molecule to yield the final desired product.

Scheme 1.

Proposed reaction mechanism for the synthesis of isoxazole-5-one and pyrazol-3-one scaffolds.

Docking analysis

The synthesized molecules were docked in the proteins predicted by the PASS online software (Table 4) to check their binding with the respective enzymes. The three proteins of insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) with PDB ID 3E4A, agonist-boundi G-protein couple receptor (GPCR) with PDB ID 6KPC, and Fibronectin type-III (FNIII) domain of human with PDB ID 2CRM were retrieved from the RCSB database. The IDE is responsible for the proteolytic inactivation and degradation of the insulin46. Insulin belongs to the class of the family that regulate the peptide hormone that are involved in various physiological process like homeostasis of glucose and energy to cognition and memory47. Inhibition of IDE can reduce the catabolism of the insulin, by potentiate the insulin signaling within the cell48. GPCR protein takes part in many crucial physiological functions, which makes them a pharmaceutically suitable druggable target49. FNIII is a glycoprotein that act as a crucial link within cells and their outer matrices50. This target is recognized as a target for many bacterial proteins51.

Table 4.

Additional evaluation of the biological activity prediction for 5J using the PASS online program (with similar findings across other results).

| Pa | Pi | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| 0.914 | 0.008 | Membrane integrity agonist (6KPC) |

| 0.808 | 0.031 | Aspulvinone dimethylallyltrasferase inhibitor (2CRM) |

| 0.716 | 0.007 | Insulysin inhibitor (3E4A) |

| 0.664 | 0.008 | Cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase inhibitor |

| 0.683 | 0.029 | Antineoplastic |

| 0.690 | 0.042 | Chlordecone reductase inhibitor |

| 0.649 | 0.003 | Alkaline phosphatase inhibitor |

| 0.655 | 0.013 | HMGCS2 expression inhibitor |

| 0.666 | 0.024 | HIF1A expression inhibitor |

| 0.599 | 0.032 | JAK2 expression inhibitor |

| 0.583 | 0.028 | Preneoplastic conditions treatment |

| 0.547 | 0.016 | Antinociceptive |

| 0.529 | 0.009 | PfA-M1 aminopeptidase inhibitor |

Compounds exhibiting Pa > Pi is expected to demonstrate biological activity, as indicated on the biological activity spectrum. A Pa value exceeding 0.5 suggests a high likelihood of activity in experimental settings.

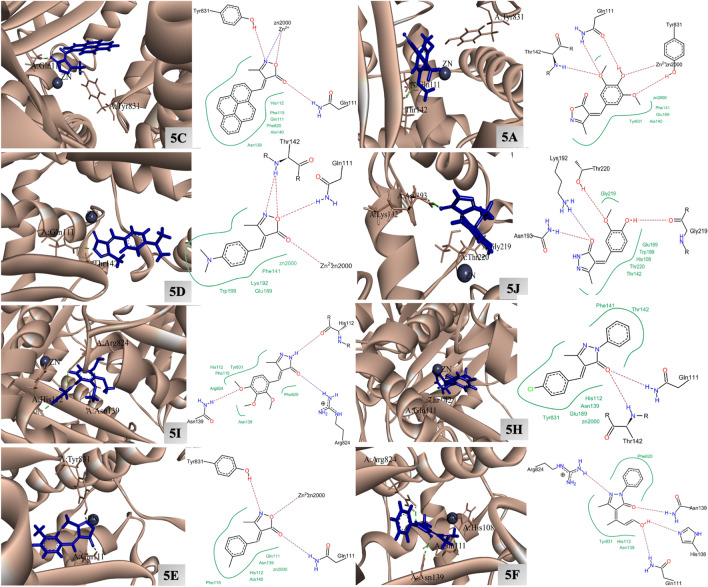

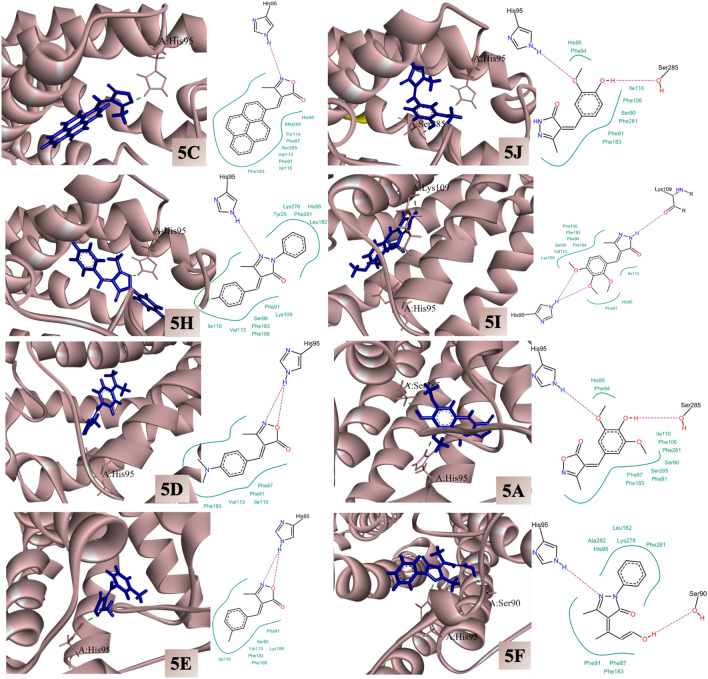

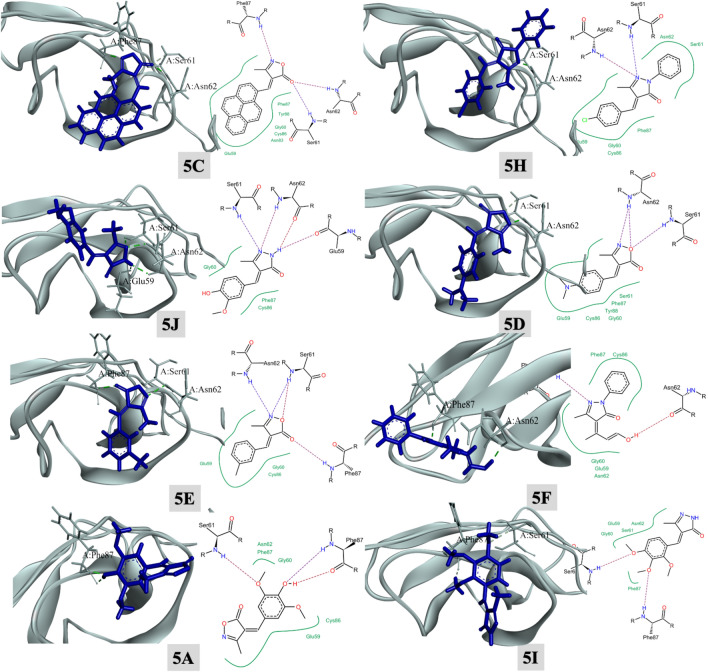

Based on the number of enzymes, against which our ten synthesized ligands displayed the best predicted activity, three set of docking calculations were conducted. The outcome of the calculations is reported in the Tables 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 and Figs. 10, 11 and 12. Tables 5, 7 and 9 represent the docking score along with other parameters. Tables 6, 8, and 10 displayed the crucial interactions formed during the interaction study. Figures 10, 11 and 12 represent the 3D and 2D interaction plots of the eight ligands with 3E4A, 6KPC, and 2CRM respectively. Interestingly, it was observed that all the three set of calculations, molecules 5B and 5G were not docked in the selected PDBs.

Table 5.

List of the docking score of the synthesized eight molecules with insulin-degrading enzyme (3E4A).

| Pose name | Docking scorea | Match scorea | Lipo scorea | Ambig scorea | Clash scorea | Rot scorea | Matchb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5C | − 23.47 | − 20.85 | − 10.34 | − 7.06 | 9.38 | 0.00 | 21 |

| 5A | − 22.02 | − 23.90 | − 3.54 | − 5.85 | 1.67 | 4.20 | 7 |

| 5D | − 21.16 | − 21.15 | − 4.31 | − 4.49 | 3.40 | 0.00 | 10 |

| 5J | − 20.92 | − 19.15 | − 6.94 | − 6.91 | 3.88 | 2.80 | 11 |

| 5I | − 19.88 | − 17.86 | − 7.37 | − 7.16 | 2.90 | 4.20 | 16 |

| 5H | − 18.42 | − 14.08 | − 6.43 | − 7.11 | 3.80 | 0.00 | 12 |

| 5E | − 17.92 | − 14.43 | − 8.98 | − 5.38 | 5.47 | 0.00 | 10 |

| 5F | − 17.43 | − 15.58 | -4.89 | − 6.66 | 2.90 | 1.40 | 8 |

akcal/mol, bnumber of matches.

Table 6.

List of the docked candidates with their docking score and amino acid interaction with insulin-degrading enzyme (3E4A).

| Name | Docking score (kcal/mol) | Amino acid interaction |

|---|---|---|

| 5C | − 23.47 | Gln111, Tyr831, Zn2000, Gln111, His112, Phe115, Asn139, Ala140, Phe820 |

| 5A | − 22.02 | Gln111, Thr142, Tyr831, Zn2000, Ala140, Phe141, Glu189, Tyr831, Zn2000 |

| 5D | − 21.16 | Gln111, Thr142, Zn2000, Phe141, Glu189, Lys192, Trp199, Zn2000 |

| 5J | − 20.92 | Lys192, Asn193, Gly219, Thr220, His108, Thr142, Glu189, Trp199, Gly219, Thr220 |

| 5I | − 19.88 | His112, Asn139, Arg824, His112, Phe115, Asn139, Phe820, Arg824, Tyr831 |

| 5H | − 18.42 | Gln111, Thr142, His112, Asn139, Phe141, Thr142, Glu189, Tyr831, Zn2000 |

| 5E | − 17.92 | Gln111, Tyr831, Zn2000, Gln111, His112, Phe115, Asn139, Ala140, Zn2000 |

| 5F | − 17.43 | His108, Gln111, Asn139, Arg824, His112, Asn139, Phe820, Tyr831 |

Amino acids in bold represents hydrogen bonding, and not bold represents van der Waals interactions.

Table 7.

List of the docking score of the synthesized eight molecules with cannabinoid receptor-GiComplex (6KPC).

| Pose name | Docking scorea | Match scorea | Lipo scorea | Ambig scorea | Clash scorea | Rot scorea | Matchb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5C | − 33.96 | − 23.63 | − 16.11 | − 4.68 | 5.06 | 0.0 | 37 |

| 5J | − 21.08 | − 15.91 | − 10.93 | − 5.62 | 3.17 | 2.8 | 14 |

| 5H | − 20.87 | − 12.98 | − 14.34 | − 5.58 | 6.63 | 0.0 | 19 |

| 5I | − 19.14 | − 16.85 | − 11.80 | − 6.48 | 6.39 | 4.2 | 20 |

| 5D | − 18.07 | − 14.38 | − 9.41 | − 3.30 | 3.62 | 0.0 | 18 |

| 5A | − 17.95 | − 16.72 | − 10.33 | − 6.09 | 5.59 | 4.2 | 17 |

| 5E | − 17.03 | − 13.95 | − 9.93 | − 4.21 | 5.66 | 0.0 | 18 |

| 5F | − 12.48 | − 12.93 | − 9.25 | − 4.01 | 6.91 | 1.4 | 13 |

akcal/mol, bnumber of matches.

Table 8.

List of the docked candidates with their docking score and amino acid interaction with cannabinoid receptor-Gi complex (6KPC).

| Name | Docking score (kcal/mol) | Amino acid interaction |

|---|---|---|

| 5C | − 33.9601 | His95, Phe87, Phe91, His95, Ile110, Val113, Thr114, Phe183, Met265, Ser283 |

| 5J | − 21.0830 | His95, Ser285, Ser90, Phe91, Phe94, Phe95, Phe106, Ile110, Phe183, Phe281 |

| 5H | − 20.8709 | His95, Tyr25, Ser90, Phe91, His95, Phe106, Lys109, Ile110, Val113, Leu182, Phe183, Lys278, Phe281 |

| 5I | − 19.1381 | His95, Lys109, Ser90, Phe91, Phe94, His95, Phe106, Lys109, Ile110, Val113, Phe183, Pro184 |

| 5D | − 18.0698 | His95, Phe87, Phe91, Ile110, Val113, Phe183 |

| 5A | − 17.9485 | His95, Ser285, Phe87, Ser90, Phe91, Phe94, His95, Phe106, Ile110, Phe183, Phe281, Ser285 |

| 5E | − 17.0277 | His95, Ser90, Phe91, Phe106, Lys109, Ile110, Val113, Phe183 |

| 5F | − 12.4799 | Ser90, His95, Phe87, Phe91, His95, Leu182, Phe183, Lys278, Phe281, Ala282 |

Amino acids in bold represents hydrogen bonding, and not bold represent van der Waals interactions.

Table 9.

List of the docking score of the synthesized eight molecules with forth FNIII domain (2CRM).

| Pose name | Docking scorea | Match scorea | Lipo scorea | Ambig scorea | Clash scorea | Rot scorea | Matchb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5C | − 18.19 | − 10.59 | − 10.55 | − 7.13 | 4.68 | 0.00 | 9 |

| 5H | − 17.54 | − 8.69 | − 11.68 | − 6.41 | 3.84 | 0.00 | 10 |

| 5J | − 16.14 | − 14.57 | − 5.98 | − 5.22 | 1.44 | 2.80 | 9 |

| 5D | − 16.08 | − 8.96 | − 10.62 | − 6.07 | 4.17 | 0.00 | 7 |

| 5E | − 13.12 | − 9.05 | − 6.98 | − 6.31 | 3.81 | 0.00 | 7 |

| 5F | − 12.75 | − 11.05 | − 6.34 | − 3.94 | 1.77 | 1.40 | 7 |

| 5A | − 12.34 | − 11.90 | − 6.11 | − 4.96 | 1.03 | 4.20 | 6 |

| 5I | − 10.86 | − 9.65 | − 8.87 | − 6.04 | 4.10 | 4.20 | 7 |

akcal/mol, bnumber of matches.

Figure 10.

The 3D and 2D interaction plots of the synthesized molecules with insulin-degrading enzyme (3E4A).

Figure 11.

The 3D and 2D interaction plots of the synthesized compounds with cannabinoid receptor-Gi complex (6KPC).

Figure 12.

The 3D and 2D interaction plots of the synthesized molecules with forth FNIII domain (2CRM).

Table 10.

List of the docked candidates with their docking score and amino acid interaction with forth FNIII domain (2CRM).

| Name | Docking score (kcal/mol) | Amino acid interaction |

|---|---|---|

| 5C | − 18.1877 | Ser61, Asn62, Phe87, Glu59, Gly60, Asn83, Cys86, Phe87, Tyr88 |

| 5H | − 17.5364 | Ser61, Asn62, Glu59, Gly60, Ser61, Asn62, Cys86, Phe87 |

| 5J | − 16.1362 | Glu59, Ser61, Asn62, Gly60, Cys86, Phe87 |

| 5D | − 16.0819 | Ser61, Asn62, Glu59, Gly60, Ser61, Cys86, Phe87, Tyr88 |

| 5E | − 13.1248 | Ser61, Asn62, Phe87, Glu59, Gly60. Cys86 |

| 5F | − 12.7543 | Asn62, Phe87, Glu59, Gly60, Asn62, Cys86, Phe87 |

| 5A | − 12.3431 | Ser61, Phe87, Glu59, Gly60, Asn62, Cys86, Phe87 |

| 5I | − 10.8640 | Ser61, Phe87, Glu59, Gly60, Ser61, Asn62, Phe87 |

Amino acids in bold represents hydrogen bonding, and without bole represent van der Waals interactions.

3E4A docking

On observing the docking score of the eight compounds with 3E4A, it was observed that 5C displayed the higher docking score (− 23.47 kcal/mol) followed by 5A, 5D, 5J, 5I, 5H, 5E, and 5F (decreasing order). The results of best four docked molecules are tabulated in the form of Table 5.

On observing the 2D docking interaction pattern, it was observed that in all the docked complexes, the crucial interactions were present48. Moreover, it is clearly visible from the Fig. 10 and Table 6, that top three candidates displayed crucial interaction with the Zn(II) atom. Apart from the interaction with Zn(II), interaction with important residues like, His108, Gln111, Asn139, Arg824, and Tyr831 was reported in the eight docked complexes (Fig. 10 and Table 6). It is well reported in the literature that IDE is an metalloenzyme, and the interaction with Zn(II) metal ion can cause the inhibition in the proper functioning of the protein48.

6KPC docking

On observing the docking score of the eight compounds with 6KPC, it was observed that 5C displayed the higher docking score (-33.96 kcal/mol) followed by 5I, 5H, 5I, 5D, 5A, 5E, and 5F (decreasing order). The results of best docked molecules are tabulated in the form of Table 7.

On observing the 2D interaction plots of 6KPC docked complexes, the crucial interactions were witnessed52. Moreover, it is clearly visible from the Fig. 11 and Table 8, that the eight docked candidates displayed crucial interactions with the residues like, His95, Lys109. Ser285. More specifically, in all the complexes, a common interaction with the residue His95 was witnessed, and the interaction with this amino acid is considered important to inhibit the proper function of the enzyme52.

2CRM docking

On observing the docking score of the eight compounds with 6KPC, it was observed that 5C displayed the higher docking score (− 18.19 kcal/mol) followed by 5H, 5J, 5D, 5E, 5F, 5A, and 5I (decreasing order). The results are tabulated in the form of Table 9.

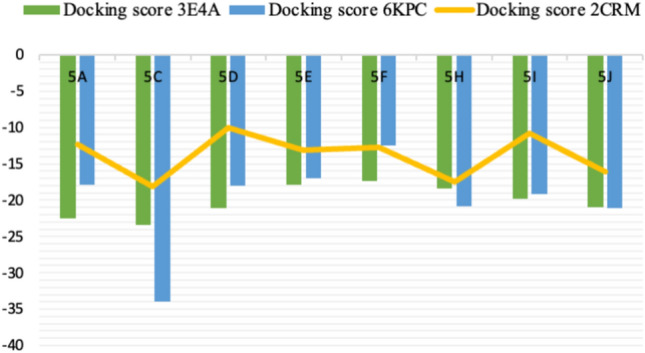

On observing the 2D interaction plots of 2CRM complexes, all the reported crucial interactions were observed53. Moreover, it is clearly visible from the Fig. 12 and Table 10, that the eight docked candidates display hydrogen bonding interactions with the amino acids residues like, Ser61, Asn62, and Phe87. All the eight docked candidates displayed at least two hydrogen bonding. More specifically, in all the complexes, a common interaction with the residue Ser61 (except 5F) was witnessed. The successful interaction of these molecules within the binding domain of 2CRM may cause inhibition of the enzyme. The docking scores of all active compounds against proteins 3E4A, 6KPC, and 2CRM are illustrated in a visual format in Fig. 13, providing a clearer understanding.

Figure 13.

Visual depiction of the docking of eight active molecules within the binding pocket of proteins 3E4A, 6KPC, and 2CRM.

ADMET/pharmacokinetics and physicochemical properties

The common docked candidates, 5C, 5A, 5D, 5J, 5I, 5H, 5E, and 5F were selected to check their ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) properties. This step is considered the most crucial step in the drug design and development. Therefore, the physicochemical and ADMET properties of the eight shortlisted compounds were carefully examined using online web-based tools. The predicted physicochemical parameters from SwissADME are reported in Table S1. These parameters help to evaluate the drug-likeness rules, as per Lipinski’s rule of 554, and Veber’s rule55. These compounds show molecular weight less than 500 Dalton, H-bond acceptors less than 10, H-bond donors less than 5, and MLogP (Lipophilicity threshold) less than 5. Moreover, all eight molecules successfully follow the drug-like properties as per the Ghose model56, Egan model57, and Muegge model58. The selected compounds did not violate the drug-likeness rules. This suggests that all compounds possess drug-like attributes and, thus, can be considered as biologically active molecules.

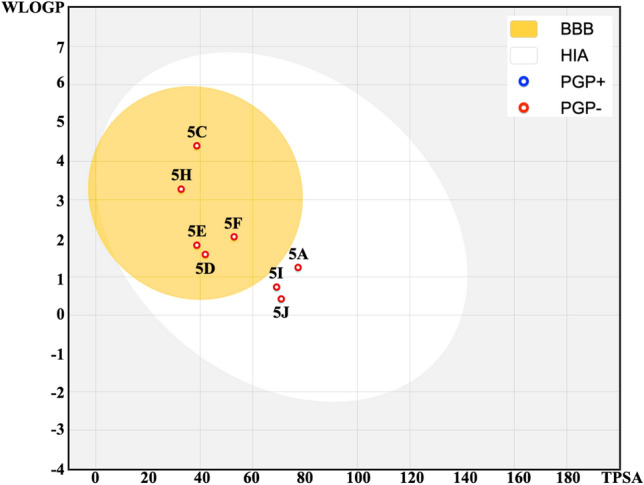

Figure 14 shows the Egan BOILED-Egg plot of the selected eight molecules. The BOILED-Egg plot studies the two pharmacokinetic behaviors and predicts gastrointestinal absorption and brain penetration (BBB) of the molecules. The yellow region in the plot corresponds to the physicochemical space of molecules with the highest probability of being permitted to the brain. It represents the hydrophobicity (WLOGP) and polarity (TPSA), which allow the graph to present good gastrointestinal absorption. The white region corresponds to the space with the highest probability of being absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract, i.e. molecules that possess only good gastrointestinal absorption. The potential substrate of P-gp (PGP+), and non-substrate (PGP-) are represented by blue, and red dots respectively. The BOILED-Egg plot reveals that all compounds can be passively absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract. However, compounds 5C, 5H, 5E, 5F, and 5D lie within the yellow region, indicating that these molecules are highly likely to be absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract and permeate into the brain. Also, all the molecules were predicted to be non-substrate, suggesting that, they have the potential for higher absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, increased BBB penetration, higher bioavailability, and better distribution within tissues. Figure S17 represents the bioavailability radar chart. It is a graphical method used to evaluate the drug-likeness of a molecule with the help of various physicochemical properties: (1) LIPO (Lipophilicity): It measures the ability of the molecules to dissolve in non-polar solvents, (2) size (molecular weight): It indicates the size of the molecule, (3) POLAR (Total polar surface area): predicts the ability of the molecule to form H-bonding, (4) INSOLU (Solubility): predicts the solubility of the molecule in water, (5) INSATU (Insaturation): indicates the proportion of unsaturated carbons in the molecules, and (6) FLEX (Flexibility): indicates the number of rotatable bonds responsible for molecular flexibility. It is clear from the figure that all the compounds exhibit the most physicochemical properties in the acceptable pink region while following Lipinski’s rule of five and Veber’s rule. This suggests that the molecules are well-optimized for drug-likeness, like, compound 5I. However, a minor deviation is seen in the INSATU parameter of compounds 5A, 5D, 5J, and 5E, and a large deviation is seen in compounds 5C and 5F. Minor deviation in INSATU suggests that the molecule has a slight imbalance in its degree of saturation, but may not significantly impact the drug-likeness of the molecules. Thus, compounds, 5I, 5A, 5D, 5J, and 5E can act as promising drug-like candidates. The predicted ADMET properties of the eight molecules are present in Table 11. These properties are based on the predicted parameters from pkCSM. The reported absorption parameters include water solubility (logS in mol/L), Caco2 permeability (logPapp in cm/s), Intestinal absorption (% Absorption), Skin Permeability (log Kp), and P-glycoprotein II inhibitor. From the water solubility parameter, compounds 5A, 5D, 5J, 5I, 5E, and 5F show better solubility, with 5J being the most soluble. The compounds 5C and 5H show moderate solubility. In Caco2 permeability, compounds 5C, 5D, 5H, 5E, and 5F shows good permeability, whereas, compound 5A, 5J and 5I shows lower permeability. Except for 5J, all the remaining compounds show high intestinal absorption in the % absorption. Also, 5C and 5E show 100% absorption. In skin permeability, compound 5A, 5J, 5I, 5C, and 5F shows good skin permeability, whereas, 5D, 5H, and 5E are on borderline. Distribution parameters contain BBB Permeability (log BB), and CNS Permeability (log PS). From BBB Permeability (log BB), molecules 5C, 5D, 5H, and 5E show good BBB permeability, indicating the potential for central nervous system (CNS) activity. Compounds 5A, 5J, 5I, and 5F have lower BBB permeability, which may limit their CNS activity. The CNS permeability parameter shows that compounds 5C and 5H have the highest CNS permeability, indicating potential for CNS activity. The molecules, 5D, 5E, and 5J have moderate CNS permeability, and compounds 5A, 5I, and 5F show the lowest CNS permeability, thus, limiting CNS penetration. From the metabolism parameters, compounds 5J and 5F are the best candidates for metabolic safety, as they do not inhibit any of the major CYP enzymes, thus, reducing the interactions with the drugs. Compounds 5A, 5D, 5I, and 5E, inhibit only CYP1A2, whereas, compounds 5C and 5H may cause significant metabolic interactions due to their broad inhibition profile of various CYP enzymes. The Excretion parameters include Total Clearance (in L/h/kg), and Renal OCT2 Substrate. From the Total Clearance parameter, molecules 5C, 5A, 5D, 5J, 5I, and 5E show moderate clearance values, favoring maintaining effective drug levels. Molecules 5H and 5F show low clearance, suggesting potential issues with drug accumulation and toxicity. In Renal OCT2, none of the compounds are substrates of OCT2 transporter, thus, indicating a reduced risk of renal drug-drug interactions through this pathway. On analyzing the toxicity parameters, compounds 5A, 5D, 5J, and 5I are negative, making them the safest option, whereas, compounds 5C and 5F may possess the risk of mutagenicity and liver toxicity, compound 5H possess the risk of hepatotoxicity, and compound 5E shows the risk of skin sensitization. Based on a balance among the ADMET parameters, the compounds 5A, 5D, 5J, and 5I can be further recommended for drug development. However, among the shortlisted four compounds, the 5D compound emerges as the best candidate that passes all the key ADMET properties and toxicity tests. Compound 5D possesses the following characteristics: (1) Good permeability and intestine absorption, (2) Good BBB permeability and moderate CNS permeability, (3) only inhibits CYP1A2, thus, reducing the risk of drug-drug interactions, (4) moderate clearance, suggesting balanced profile, and (5) negative for all tested toxicity parameters 9AMES toxicity, hERG I inhibition, hepatotoxicity, and skin sensitization). These properties demonstrate that compound (5D) can be the most promising candidate for further drug development. Based on the ADMET profile, compound 5D has been selected for the molecular dynamic simulation studies with the selected enzyme 3E4A, 6KPC, and 2CRM (3E4A-5D, 6KPC-5D, and 2CRM-5D).

Figure 14.

BOILED-Egg diagram evaluating passive gastrointestinal absorption (HIA) and Blood-brain barrier penetration (BBB) with WLOGP vs TPSA for the eight common docked candidates after drug-likeness and lead-likeness studies generated from the SwissADME59 web tool.

Table 11.

List of the predicted ADME/pharmacokinetics properties of the eight common docked inhibitors retrieved from web tool pkCSM60.

| Properties | Predicted parameters | 5C | 5A | 5D | 5J | 5I | 5H | 5E | 5F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Water solubility (mol/L) | − 5.89 | − 2.88 | − 2.96 | − 2.21 | − 3.17 | − 5.06 | − 2.88 | − 3.50 |

| Caco2 permeability (pkCSM) | 1.29 | 0.22 | 1.66 | 0.15 | 0.52 | 1.47 | 1.25 | 1.34 | |

| Intestinal absorption (% Absorption) | 100 | 94.93 | 96.99 | 74.15 | 95.74 | 95.22 | 97.60 | 93.92 | |

| Skin permeability (log Kp) | − 2.73 | − 3.30 | − 2.28 | − 3.53 | − 3.50 | − 2.31 | − 2.51 | − 2.95 | |

| P-glycoprotein II inhibitor | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Higher water solubility is preferable for better absorption, Caco-2 > 0.90 (good permeability), % absorption > 80%, skin permeability < − 2.5 | |||||||||

| Distribution | BBB permeability (log BB) | 0.16 | − 0.38 | 0.27 | − 0.01 | − 0.44 | 0.27 | 0.35 | − 0.11 |

| CNS permeability (log PS) | − 1.49 | − 2.58 | − 2.14 | − 2.51 | − 2.93 | − 1.33 | − 2.03 | − 2.79 | |

| log BB > − 1 (good BBB penetration), log PS > − 3 (penetrate the central nervous system (CNS), < − 3 (unable to penetrate the CNS) | |||||||||

| Metabolism | CYP2D6 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | |

| CYP2D6 prediction: no | |||||||||

| Excretion | Total clearance | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.73 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.01 | 0.67 | 0.07 |

| Renal OCT2 substrate | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Moderate range of clearance is acceptable, Renal OCT2 substrate: no | |||||||||

| Toxicity | AMES toxicity | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| hERG I inhibitor | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Hepatotoxicity | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | |

| Skin sensitization | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | |

AMES toxicity: No, hERG I inhibitor: No, Hepatotoxicity: No, Skin sensitization: No.

Molecular dynamics simulation studies

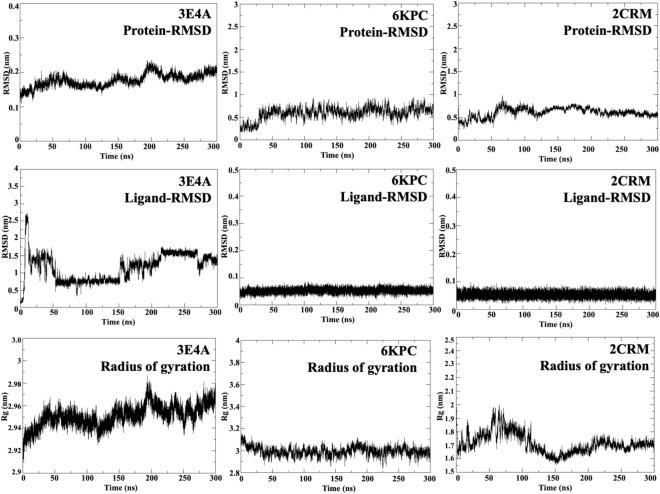

Molecular dynamics simulations were conducted for 300 ns on the ligand 5D in complex with 3EA4, 6KPC, and 2CRM to check the stability of 5D within the biological environment of the three proteins. The stability of these complexes was evaluated via plots like RMSD (protein and ligand), RMSF (protein and ligand), Rg, and H-bonding as shown in Figs. 15 and S18. The average values of protein-ligand RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and H-bonding are shown in Table S2. Protein-RMSD of complexes was carried out to check the structural deviations throughout the time duration of 300 ns. The average RMSD values for the 3E4A, 6KPC, and 2CRM were found to be 0.18 ± 0.02 nm, 0.59 ± 0.14 nm, and 0.61 ± 0.10 nm respectively. We observed from Fig. 15 that the stability of the protein backbone has not been impacted by the docked compound bound in the active site of the respective protein. The stability of the ligand in the active site of the respective protein is analyzed by the ligand-RMSD plot. The average ligand-RMSD values for 3E4A-5D, 6KPC-5D, and 2CRM-5D are 1.16 ± 0.40 nm, 0.05 ± 0.04 nm, and 0.05 ± 0.01 nm respectively. The outcome from ligand-RMSD plots revealed that molecule 5D displays a similar kind of fluctuation behaviour in 6KPC and 2CRM, indicating consistent binding stability and interaction pattern in these complexes. In contrast, the higher RMSD value for 3E4A-5D suggests greater fluctuation in the complex. The RMSD analysis confirmed that all the docked candidates have greater stability than the reference in the CDK5 binding site. Overall, the protein-ligand RMSD analysis indicates that molecule 5D exhibits stable binding in 6KPC and 2CRM, it shows greater fluctuation in 3E4A despite the protein fluctuation in 3E4A being lower. Lower protein RMSD and higher ligand RMSD depict that while the overall protein structure remains stable, the ligand shows significant fluctuations within the binding site of the protein, suggesting less stable binding of the ligand to the protein. The Rg measures the compactness of the protein structure and provides insight into the overall shape and folding of the protein. The average Rg values of 3E4A, 6KPC, and 2CRM are 2.95 ± 0.01 nm, 2.99 ± 0.04 nm, and 1.71 ± 0.07 nm respectively. On comparing Rg with the protein RMSD, the 3E4A shows lower protein RMSD, indicating overall structural stability. The average Rg value of 3E4A indicates a relatively compact structure, which might contribute to the observed stability of the protein. In the case of proteins, 6KPC, and 2CRM, higher average protein RMSD values indicate more structural deviation over time. However, the Rg value of 6KPC and 2CRM indicate that 6KPC is similar in compactness as in 3E4A, while 2CRM is more compact, possibly contributing to the more stable ligand binding in the 2CRM protein. Overall, the structural stability and compactness of the protein correlate with the observed binding stability of the ligands, indicating that a stable protein structure ensures stable ligand binding as in the case of 6KPC and 2CRM. However, in 3E4A, the protein deviation pattern highlights a stable protein behaviour, but, shows significant fluctuations within the active site of the protein.

Figure 15.

Graphical representation of protein-RMSD, ligand-RMSD, and Rg of 5D-6KPC, 5D-3EA4, and 5D-2CRM formed during the molecular dynamic simulations of 300ns.

Further to check the flexibility of residues in the protein backbone, protein RMSF plots were generated, as shown in Fig. S18. The average protein-RMSF of 3E4A, 6KPC, and 2CRM is 0.10 ± 0.05 nm, 0.27 ± 0.10 nm, and 0.75 ± 0.46 nm respectively. The average protein RMSF for 3E4A is relatively low, indicating that the individual residues of the protein are stable and exhibit minimal fluctuation. In the case of 6KPC and 2CRM, the average RMSF values are higher, indicating that the residues in these protein chains are more flexible. Ligand- RMSF measures the atom’s deviation from its average position during the simulation run. The average ligand-RMSF of 5D in 3E4A, 6KPC, and 2CRM is 0.10 ± 0.06 nm, 0.05 ± 0.04 nm, and 0.05 ± 0.04 nm respectively. The average ligand RMSF of 5D is similar in 6KPC, and 2CRM, indicating their similar behaviour in the binding site of the respective proteins. A similar pattern is also observed in the ligand RMSD plots of 5D, which show consistent binding stability of 5D in the two proteins 6KPC, and 2CRM. The average ligand RMSF of 5D in 3E4A indicates moderate fluctuations in the position of the ligand, correlating with its fluctuation observed in the ligand RMSD. Additionally, average H-bonds were evaluated from the three complexes, as shown in Fig. 7. Hydrogen bonding reflects bonding between the ligand and protein formed within the complex during the simulation run. The average H-bond value of 3E4A, 6KPC, and 2CRM is 0.16 ± 0.47, 0.40 ± 0.55, and 0.16 ± 0.45 respectively. The average number of H-bonds formed indicates the involvement of these bonds in stabilizing the complex with the ligand 5D and the respective proteins. Overall from all the studied properties, we can conclude that 6KPC and 2CRM displayed slightly higher protein fluctuations with stable ligand binding, supported by a more compact structure (2CRM) and moderate H-bonding. Protein 3E4A displays a stable protein structure but exhibits fluctuations in ligand binding, possibly affecting its interaction dynamics.

Gram scale synthesis

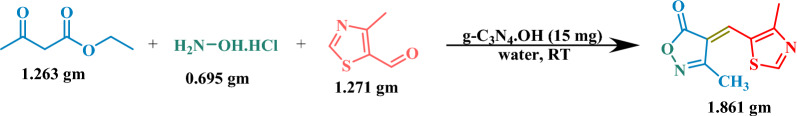

We showcased the robustness of our methodology for industrial-scale applications through a compelling demonstration of gram-scale synthesis. Initially, 4-methylthiazole-5-carboxaldehyde (1.271 gm), ethyl acetoacetate (1.263 gm), and hydroxylamine hydrochloride (0.695 gm), were reacted for the synthesis of 4-methyl thiazole-substituted methylene isoxazole-5-one (1.861 gm). This synthesis was seamlessly executed with the assistance of a mere 15 mg of the g-C3N4·OH catalyst in water at ambient temperature, culminating in an impressive 89% product yield achieved within a mere 45 minutes. The validation of reaction completion was confirmed through TLC analysis, ensuring precision and reliability. Subsequently, a pivotal step in our process was the efficient recovery of the catalyst utilizing methanol further enhancing the sustainability and cost-effectiveness of our approach. Following this, the crude product underwent a rigorous purification process, elevating its quality to unparalleled levels. This meticulous purification yielded the product in its purest form, boasting exceptional yields that underscore the viability of our methodology for large-scale industrial applications. This demonstration represents a significant leap forward in industrial chemistry, promising enhanced efficiency, sustainability, and economic viability (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 3-methyl-4-((4-methylthiazol-5-yl)methylene)isoxazol-5(4H)-one on a gram scale.

Green chemistry matrix

In recent years, there has been a notable shift towards developing environmentally friendly and sustainable methods for synthesizing organic compounds. One such pioneering approach is green chemistry, which provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating the environmental impact of chemical reactions61–63. An exemplary illustration of this approach is the utilization of g-C3N4·OH as a catalyst in the synthesis of isoxazol-one and pyrazol-one derivatives. This methodology has exhibited remarkable attributes, including a low E-factor (0.28–0.72), high atom economy (63.63–81.06), superior reaction mass efficiency (57.96–77.97), elevated process mass intensity (1.30–1.75), and an impressive eco-score (74.66–78.71). These compelling findings underscore the viability of employing g-C3N4·OH catalysts in the synthesis of these scaffolds as a sustainable and eco-conscious strategy, with minimal adverse effects on the environment. [Detailed data and calculations are provided in the SI File].

Experimental section

The chemicals employed were sourced from suppliers Sigma-Aldrich, Loba-Chemie, and Merck, ensuring the highest quality standards. They were utilized without the need for additional purification, underscoring their exceptional purity. Melting points were meticulously determined using an electric thermal melting point apparatus, with results reported precisely and without any compromises. The progression of reactions was meticulously tracked through thin-layer chromatography, executed on top-of-the-line silica gel 60 RP-18 F254S plates under the illumination of advanced 3 NOS UV cabinets. The catalyst's IR spectrum was meticulously recorded using a Bruker FTIR spectrometer, ensuring a detailed analysis of its chemical composition. For the comprehensive characterization of the synthesized catalyst, both Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) studies were conducted using the renowned Hitachi, SU8010 SERIES system, guaranteeing unparalleled insights into its morphology and structure. Furthermore, the XRD spectrum was acquired using the Rigaku Ultma IV X-Ray diffractometer, providing precise information on the crystalline properties of the catalyst. The TGA/DTA analysis was recorded on Hitachi NEXTA STA300 system to measures changes in weight and differential temperature to analyze thermal stability and composition. To complement these analyses, 1H and 13C NMR spectra were meticulously recorded using the high-performance JEOL 400 MHz instrument, with CDCl3 and DMSO-d6 as solvents, and TMS serving as the internal standard, ensuring the utmost accuracy and reliability in structural elucidation.

General procedure of g-C3N4·OH catalyst

20 gram of urea powder was carefully placed into a crucible, which was then covered with aluminum foil. The mixture was heated at 550 °C for 2.5 hours to initiate pyrolysis, resulting in the formation of approximately 1 gram of crude g-C3N4. Subsequently, the crude product was introduced into a 50 mL solution of hydrogen peroxide (20 wt%). The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 hours. After filtration and thorough washing with a mixture of ethanol and water, followed by additional rinsing with water alone, the product was dried at 80 °C. The final product obtained was a pale white powder.

Recycling of the catalyst

The catalyst was removed from the reaction mixture by filtration with methanol. After filtration, the catalyst was collected on the filter paper and was washed sequentially with a water-ethanol mixture followed by ethanol. The washed catalyst was then dried at 80 °C for 2 hours before being reused in the next reaction.

General procedure for the synthesis of isoxazole-5-one/ pyrazol-3-one derivatives

A solution was prepared by combining 1 mmol of each hydroxylamine hydrochloride/phenyl hydrazine/hydrazine hydrate, ethyl acetoacetate, and aldehyde, along with 15 mg of g-C3N4·OH catalyst, using water as a solvent at room temperature. The mixture was stirred in a round bottomed flask for an appropriate duration. The reaction progress was monitored using TLC in a 20% ethyl acetate: hexane solution. Afterward, the catalyst was recovered through filtration using acetone. The pure product was obtained via column chromatography. Subsequently, the product was characterized using 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy.

Molecular docking

On searching the PASS online program for the synthesized compounds, the synthesized compounds were found to predict the activity against the IDE, GPCR, and FNIII domain of human. The three proteins of insulin-degrading enzyme with PDB ID 3E4A, GPCR with PDB ID 6KPC, and FNIII domain of human with PDB ID 2CRM were retrieved from the RCSB database. To check the binding affinity of the synthesized compounds within these selected enzymes, molecular docking calculations were performed. Molecular docking played a crucial role in the field of drug design, as it predicts and study the interactions/binding of ligands and proteins64. In the current study, the docking calculations were performed by using Incremental construction-based algorithm using FlexX module65 of LeadIT 2.1.8 program66. All the selected enzymes were prepared by using receptor preparation module of LeadIT 2.1.8 program. During preparation of the proteins, atom-types were assigned, polar hydrogen atoms were added, and crystallographic water was removed. The selection of the binding site was made based on the presence of co-crystallized ligand in the respective PDB, Q1X ligand in 3E4A, and E3R inhibitor in 6KPC. However, in case of 2CRM, there was no reported inhibitor, thus, we conducted blind docking to search for the suitable cavity followed by the docking calculations. For conducting docking in 3E4A and 6KPC, a radius of 10 Å was selected from the center of the respective ligand. It is predicted that within this radius, all the crucial residues are present. These residues are responsible for forming bonding with the ligand. Further, the chemical ambiguities present in the binding site of the proteins were resolved by ProToss module of the LeadIT 2.1.8 program. Moreover, ProToss module is also involved in optimizing the amino-acids, reference inhibitors, co-factors (if any), and assign the proper protonation state along with the proper tautomers to the binding site of the protein. Default docking parameters were applied to conduct the studies. From each docking calculation, top 50 poses were requested. The results were generated in the form of 2D interaction plots of the docked candidates. The docked candidates were further subjected to pharmacokinetics studies to evaluate their drug-likeness and ADMET properties.

ADMET/pharmacokinetics and physicochemical properties

The ADMET/pharmacokinetics and physicochemical properties of the common eight docked compounds were assessed using the free web tool pkCSM60. Also, the SwissADME59 web tool was utilized to generate the BOILED-Egg (Brain Or IntestinaL EstimateD permeation method) model67, and Bioavailability Radar Chart. This model predicts a molecule's ability to balance gastrointestinal absorption and blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration. The SwissADME web tool also predicts whether a compound is a substrate of P-glycoprotein (P-gp), a key active efflux mechanism involved in the biological barriers. SwissADME software is available as a web server by the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. For ADMET/pharmacokinetic and physicochemical analysis, the molecules were converted into SMILES (simplified molecular input line with entry system) format. The shortlisted candidates that show an acceptable range of ADMET/pharmacokinetics and physicochemical properties were selected to conduct the molecular dynamics simulation studies.

Molecular dynamics simulation studies

The shortlisted candidate (5D) was selected for simulation studies with three PDB structures: 3E4A, 6KPC, and 2CRM. Consequently, three simulations (3E4A-5D, 6KPC-5D, and 2CRM-5D) were performed for 300 ns using the amber99sb force field68 within GROMACS 5.0.7 software69. The ligand topology file was generated with an amber atom-type force field via ACPYPE70, and ligand charges were accurately determined using the AM1-BCC method implemented in the antechamber. The TIP3P water model was employed for its high mobility, which preserves the protein's thermodynamic characteristics and enhances simulation sampling effectiveness. The protein-ligand complexes were centered in a dodecahedron box filled with water molecules, maintaining a 1nm distance from the protein center. The systems were neutralized with Cl-/Na+ counter ions71,72. Energy minimization was achieved using the steepest descent algorithm until a maximum force of > 10.0 kJ/mol (50,000 steps) was reached to stabilize the system. Position restraint equilibration was performed for 1 ns under the NVT ensemble, maintaining constant volume (100 ps) and temperature (300 K) using the Berendsen thermostat algorithm. Subsequently, NPT equilibration at a constant pressure of 1 bar for 100 ps using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat73 was performed. Long-range electrostatic, coulombic, and Van der Waals interactions were computed using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method with a 1 nm cut-off. The Linear Constraint Solver (LINCS) algorithm was employed to maintain the stability and preserve molecular geometry by imposing constraints on bond lengths74. The simulations were conducted with the default parameters for 200 ns. The coordinates were recorded every 2 fs and Leap-frog integrator was used to compute the equations of motion. Properties like root mean square deviations (RMSD), root mean square fluctuations (RMSF), radius of gyration (Rg), and hydrogen (H)-bonding were computed to determine the stability of the complexes. The XMGRACE software was utilized to generate the plots75.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the development of a novel multicomponent reaction technique utilizing the g-C3N4·OH nanocomposite catalyst represents a significant advancement in green synthetic methodologies for the synthesis of isoxazole-one and pyrazole-one derivatives. The exceptional yields (89–97%), short reaction durations (25–45 min), and outstanding recyclability of the catalyst (6 runs) highlight its potential for industrial-scale synthesis while maintaining environmental sustainability. This study not only contributes to the advancement of sustainable synthetic chemistry but also demonstrates its adherence to green metrics such as the E-factor and eco-score, confirming its environmental viability. Moreover, the comprehensive analysis of the synthesized compounds for pharmacological activities, supported by computational methodology, underscores the significance of this research in guiding drug design and discovery. From docking calculations, it was depicted that two compounds, 5B and 5G, were not able to bind to the selected proteins. Furthermore, the trend in docking scores suggests that among the three sets of docking calculations, molecule 5C displayed the highest docking score, indicating a high affinity towards the respective receptors. From the docked molecules, compounds 5I, 5A, 5D, 5J, and 5E exhibit favourable drug-like properties, meeting the criteria of bioavailability and CNS permeability. Among these, compound 5D stands out as the most promising candidate due to its optimal ADMET profile, including good BBB permeability, low risk of drug interactions, balanced clearance, and absence of toxicity concerns. From the molecular dynamics simulation study of 5D in complex with the three proteins, 3E4A protein showed structurally stable behaviour with fluctuating ligand binding, 6KPC, and 2CRM display higher structure flexibility with stable ligand binding. These outcomes emphasize the potential of compound 5D as a promising candidate for drug development across different protein structures, supported by its favourable drug-like and ADMET properties, interactions observed through docking, and stable behaviour in the binding cavity as explained in the simulation studies. Through the integration of experimental and computational approaches, this research offers a promising pathway for the development of green and efficient synthetic methodologies in organic chemistry with applications in pharmaceutical drug discovery.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Department of Chemistry, MLSU, Udaipur for providing research facilities, and Department of Physics, MLSU Udaipur, CIL, Punjab and SAIF, IIT Bombay for XRD, SEM, EDX, and TGA/DTA studies respectively. P. Teli wish to acknowledge CSIR, India (09/172(0088)2018-EMR-I) (09/172(0099)2019-EMR-I) for senior research fellowship as financially support. S. Agarwal acknowledges DST-SERB, SURE (No. SUR/2022/001312) for financial support. S. Agarwal also sincerely acknowledges the Ministry of Education, SPD-RUSA Rajasthan for providing NMR facility under RUSA 2.0, Research and Innovation project (File no. /RUSA/GEN/MLSU/2020/6394).

Author contributions

S.S. wrote the main manuscript, A.M. and P.C. Jha performed the docking, pharmacokinetic, and simulation studies, S.T. and P.T. helped in data analysis and writing, S.A. wrote, and revised the manuscript and overall supervision.

Funding

The funding was supported by Science and Engineering Research Board, Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, India, Rashtriya Uchchatar Shiksha Abhiyan.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article as supplementary information files which include 1H and 13C NMR of synthesized compounds

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-70071-9.

References

- 1.Galehban, M. H., Zeynizadeh, B. & Mousavi, H. Ni II NPs entrapped within a matrix of l-glutamic acid cross-linked chitosan supported on magnetic carboxylic acid-functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotube: A new and efficient multi-task catalytic system for the green one-pot synthesis of diverse heterocyclic frameworks. RSC Adv.12(26), 16454–16478 (2022). 10.1039/D1RA08454B [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mousavi, H. A comprehensive survey upon diverse and prolific applications of chitosan-based catalytic systems in one-pot multi-component synthesis of heterocyclic rings. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.186, 1003–1166 (2021). 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.06.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soni, S. et al. Advances in the synthetic strategies of benzoxazoles using 2-aminophenol as a precursor: An up-to-date review. RSC Adv.13(34), 24093–24111 (2023). 10.1039/D3RA03871H [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teli, P. et al. Synergistic applications of nanocomposite, ultrasound, and on-water synthesis for efficient and green synthesis of spirooxindole derivatives via cascade C-N, C–O, and C–S bond formation. Appl. Organomet. Chem.38, e7393 (2024). 10.1002/aoc.7393 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galehban, M. H., Zeynizadeh, B. & Mousavi, H. Introducing Fe3O4@ SiO2@ KCC-1@ MPTMS@ CuII catalytic applications for the green one-pot syntheses of 2-aryl (or heteroaryl)-2, 3-dihydroquinazolin-4 (1H)-ones and 9-aryl-3, 3, 6, 6-tetramethyl-3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9-hexahydro-1H-xanthene-1, 8 (2H)-diones. J. Mol. Struct.1271, 134017 (2023). 10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.134017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teli, S. et al. Unlocking the potential of Ficusreligiosa tree bark-derived biochar sulfonic acid: a journey from synthesis and characterization to its astonishing catalytic role in green synthesis of perimidines. Res. Chem. Intermed.50, 1–21 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmerman, J. B. et al. Designing for a green chemistry future. Science367(6476), 397–400 (2020). 10.1126/science.aay3060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma, U. K. et al. Sequential and direct multicomponent reaction (MCR)-based dearomatization strategies. Chem. Soc. Rev.49(23), 8721–8748 (2020). 10.1039/D0CS00128G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castiello, C. et al. GreenMedChem: The challenge in the next decade toward eco-friendly compounds and processes in drug design. Green Chem.25(6), 2109–2169 (2023). 10.1039/D2GC03772F [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mousavi, H. A concise and focused overview upon arylglyoxal monohydrates-based one-pot multi-component synthesis of fascinating potentially biologically active pyridazines. J. Mol. Struct.1251, 131742 (2022). 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131742 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soni, R. A., Rizwan, M. A. & Singh, S. Opportunities and potential of green chemistry in nanotechnology. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng.7(3), 661–673 (2022). 10.1007/s41204-022-00233-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.John, S. E., Gulati, S. & Shankaraiah, N. Recent advances in multi-component reactions and their mechanistic insights: A triennium review. Org. Chem. Front.8(15), 4237–4287 (2021). 10.1039/D0QO01480J [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jana, R., Begam, H. M. & Dinda, E. The emergence of the C-H functionalization strategy in medicinal chemistry and drug discovery. Chem. Commun.57(83), 10842–10866 (2021). 10.1039/D1CC04083A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anthony, E. J. et al. Metallodrugs are unique: Opportunities and challenges of discovery and development. Chem. Sci.11(48), 12888–12917 (2020). 10.1039/D0SC04082G [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alaghmandfard, A. & Ghandi, K. A comprehensive review of graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4)–metal oxide-based nanocomposites: Potential for photocatalysis and sensing. Nanomaterials12(2), 294 (2022). 10.3390/nano12020294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iqbal, O. et al. A review on the synthesis, properties, and characterizations of graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) for energy conversion and storage applications. Mater. Today Phys.34, 101080 (2023). 10.1016/j.mtphys.2023.101080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soni, S. et al. Exploring the synthetic potential of a gC 3 N 4· SO 3 H ionic liquid catalyst for one-pot synthesis of 1, 1-dihomoarylmethane scaffolds via Knoevenagel-Michael reaction. RSC Adv.13(19), 13337–13353 (2023). 10.1039/D3RA01971C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song, X.-L. et al. Engineering g-C3N4 based materials for advanced photocatalysis: Recent advances. Green Energy Environ.9, 166–197 (2022). 10.1016/j.gee.2022.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raha, S. & Ahmaruzzaman, M. A novel Ag/g-C3N4/ZnO/Fe3O4 nanohybrid superparamagnetic photocatalyst for efficient degradation of emerging pharmaceutical contaminant (Pantoprazole) from aqueous sources. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.10(6), 108904 (2022). 10.1016/j.jece.2022.108904 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen, Q. et al. A hydroxyl-induced carbon nitride homojunction with functional surface for efficient photocatalytic production of H2O2. Appl. Catal. B Environ.324, 122216 (2023). 10.1016/j.apcatb.2022.122216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muhammad, I., Mannathan, S. & Sasidharan, M. Quaternary ammonium hydroxide-functionalized g-C3N4 catalyst for aerobic hydroxylation of arylboronic acids to phenols. J. Chin. Chem. Soc.67(8), 1470–1476 (2020). 10.1002/jccs.202000141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muhammad, I. & Usman, J. Antibacterial studies of molecularly engineered graphitic carbon nitride (gC 3N4) to quaternary ammonium hydroxide (gC 3N4-OH) composite: An application towards generating new antibiotics. Chem. Int.9(3), 77–85 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tonelli, F. M. P., Roy, A. & Murthy, H. A. Green Nanoremediation: Sustainable Management of Environmental Pollution (Springer Nature, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 24.da Silva, A. F. et al. Isoxazol-5-ones as strategic building blocks in organic synthesis. Synthesis50(13), 2473–2489 (2018). 10.1055/s-0036-1589534 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das, N. et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of some new aryl pyrazol-3-one derivatives as potential hypoglycemic agents (2008).

- 26.Bensaber, S. M. et al. Chemical synthesis, molecular modelling, and evaluation of anticancer activity of some pyrazol-3-one Schiff base derivatives. Med. Chem. Res.23, 5120–5134 (2014). 10.1007/s00044-014-1064-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arya, G. C., Kaur, K. & Jaitak, V. Isoxazole derivatives as anticancer agent: A review on synthetic strategies, mechanism of action and SAR studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem.221, 113511 (2021). 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaikh, J., Patel, K. & Khan, T. Advances in pyrazole based scaffold as cyclin-dependent kinase 2 inhibitors for the treatment of cancer. Mini Rev. Med. Chem.22(8), 1197–1215 (2022). 10.2174/1389557521666211027104957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cherukupalli, S. et al. An insight on synthetic and medicinal aspects of pyrazolo [1, 5-a] pyrimidine scaffold. Eur. J. Med. Chem.126, 298–352 (2017). 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rimaz, M. et al. Facile, capable, atom-economical one-pot multicomponent strategy for the direct regioselective synthesis of novel isoxazolo [5, 4-d] pyrimidines. Res. Chem. Intermed.45, 2673–2694 (2019). 10.1007/s11164-019-03757-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pandhurnekar, C. P. et al. A review of recent synthetic strategies and biological activities of isoxazole. J. Heterocycl. Chem.60(4), 537–565 (2023). 10.1002/jhet.4586 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ebenezer, O., Shapi, M. & Tuszynski, J. A. A review of the recent development in the synthesis and biological evaluations of pyrazole derivatives. Biomedicines10(5), 1124 (2022). 10.3390/biomedicines10051124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chanda, A. & Fokin, V. V. Organic synthesis “on water”. Chem. Rev.109(2), 725–748 (2009). 10.1021/cr800448q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeynizadeh, B., Mohammad Aminzadeh, F. & Mousavi, H. Chemoselective reduction of nitroarenes, N-acetylation of arylamines, and one-pot reductive acetylation of nitroarenes using carbon-supported palladium catalytic system in water. Res. Chem. Intermed.47(8), 3289–3312 (2021). 10.1007/s11164-021-04469-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rimaz, M., Khalafy, J. & Mousavi, H. A green organocatalyzed one-pot protocol for efficient synthesis of new substituted pyrimido [4, 5-d] pyrimidinones using a Biginelli-like reaction. Res. Chem. Intermed.42, 8185–8200 (2016). 10.1007/s11164-016-2588-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mousavi, H., Zeynizadeh, B. & Rimaz, M. Green and efficient one-pot three-component synthesis of novel drug-like furo [2, 3-d] pyrimidines as potential active site inhibitors and putative allosteric hotspots modulators of both SARS-CoV-2 MPro and PLPro. Bioorg. Chem.135, 106390 (2023). 10.1016/j.bioorg.2023.106390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mousavi, H., Rimaz, M. & Zeynizadeh, B. Practical three-component regioselective synthesis of drug-like 3-Aryl (or heteroaryl)-5, 6-dihydrobenzo [h] cinnolines as potential non-covalent multi-targeting inhibitors to combat neurodegenerative diseases. ACS Chem. Neurosci.15(9), 1828–1881 (2024). 10.1021/acschemneuro.4c00055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sabe, V. T. et al. Current trends in computer aided drug design and a highlight of drugs discovered via computational techniques: A review. Eur. J. Med. Chem.224, 113705 (2021). 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guan, Y. et al. Alkali hydrothermal treatment to synthesize hydroxyl modified g-C3N4 with outstanding photocatalytic phenolic compounds oxidation ability. Nano15(07), 2050083 (2020). 10.1142/S1793292020500836 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nongrum, R. et al. A nano-organo catalyst mediated approach towards the green synthesis of 3-methyl-4-(phenyl) methylene-isoxazole-5 (4H)-one derivatives and biological evaluation of the derivatives as a potent anti-fungal and anti-tubercular agent. Sustain. Chem. Pharm.32, 100967 (2023). 10.1016/j.scp.2023.100967 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Faramarzi, Z. & Kiyani, H. Steglich’s base catalyzed three-component synthesis of isoxazol-5-ones. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd.43(4), 3099–3121 (2023). 10.1080/10406638.2022.2061533 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boureghda, C. et al. Sulfamic acid catalyzed facile synthesis of Arylmethyleneisoxazolone derivatives (2022).

- 43.Tajbakhsh, M. et al. A green protocol for the one-pot synthesis of 3, 4-disubstituted isoxazole-5 (4H)-ones using modified β-cyclodextrin as a catalyst. Sci. Rep.12(1), 19106 (2022). 10.1038/s41598-022-23814-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shaglof, A., Ali, M. F. & Elzlatene, H. Synthesis and evaluation of biological activity of pyrazolone compounds. J. Pharm. Appl. Chem.7(1), 8–22 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barkule, A. B., Gadkari, Y. U. & Telvekar, V. N. One-pot multicomponent synthesis of 3-methyl-4-(hetero) arylmethylene isoxazole-5 (4h)-ones using guanidine hydrochloride as the catalyst under aqueous conditions. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd.42(9), 5870–5881 (2022). 10.1080/10406638.2021.1959353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.González-Casimiro, C. M. et al. Modulation of insulin sensitivity by insulin-degrading enzyme. Biomedicines9(1), 86 (2021). 10.3390/biomedicines9010086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rahman, M. S. et al. Role of insulin in health and disease: An update. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22(12), 6403 (2021). 10.3390/ijms22126403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leissring, M. A. et al. Designed inhibitors of insulin-degrading enzyme regulate the catabolism and activity of insulin. PLoS One5(5), e10504 (2010). 10.1371/journal.pone.0010504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alhosaini, K. et al. GPCRs: The most promiscuous druggable receptor of the mankind. Saudi Pharm. J.29(6), 539–551 (2021). 10.1016/j.jsps.2021.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.To, W. S. & Midwood, K. S. Plasma and cellular fibronectin: Distinct and independent functions during tissue repair. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair4, 1–17 (2011). 10.1186/1755-1536-4-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vaca, D. J. et al. Interaction with the host: The role of fibronectin and extracellular matrix proteins in the adhesion of Gram-negative bacteria. Med. Microbiol. Immunol.209(3), 277–299 (2020). 10.1007/s00430-019-00644-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hua, T. et al. Activation and signaling mechanism revealed by cannabinoid receptor-Gi complex structures. Cell180(4), 655-665.e18 (2020). 10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reddy, T. S. et al. Efficient approach for the synthesis of aryl vinyl ketones and its synthetic application to mimosifoliol with DFT and autodocking studies. Molecules28(17), 6214 (2023). 10.3390/molecules28176214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lipinski, C. A. et al. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev.23(1–3), 3–25 (1997). 10.1016/S0169-409X(96)00423-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Veber, D. F. et al. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem.45(12), 2615–2623 (2002). 10.1021/jm020017n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghose, A. K., Viswanadhan, V. N. & Wendoloski, J. J. A knowledge-based approach in designing combinatorial or medicinal chemistry libraries for drug discovery. 1. A qualitative and quantitative characterization of known drug databases. J. Comb. Chem.1(1), 55–68 (1999). 10.1021/cc9800071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Egan, W. J., Merz, K. M. & Baldwin, J. J. Prediction of drug absorption using multivariate statistics. J. Med. Chem.43(21), 3867–3877 (2000). 10.1021/jm000292e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muegge, I., Heald, S. L. & Brittelli, D. Simple selection criteria for drug-like chemical matter. J. Med. Chem.44(12), 1841–1846 (2001). 10.1021/jm015507e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep.7(1), 42717 (2017). 10.1038/srep42717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pires, D. E., Blundell, T. L. & Ascher, D. B. pkCSM: Predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J. Med. Chem.58(9), 4066–4072 (2015). 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sheldon, R. A. Metrics of green chemistry and sustainability: Past, present, and future. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng.6(1), 32–48 (2018). 10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b03505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Constable, D. J., Curzons, A. D. & Cunningham, V. L. Metrics to ‘green’ chemistry—Which are the best?. Green Chem.4(6), 521–527 (2002). 10.1039/B206169B [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Aken, K., Strekowski, L. & Patiny, L. EcoScale, a semi-quantitative tool to select an organic preparation based on economical and ecological parameters. Beilstein J. Org. Chem.2(1), 3 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Solanki, P. et al. A comprehensive analysis of the role of molecular docking in the development of anticancer agents against the cell cycle CDK enzyme. Biocell47(4), 707–729 (2023). 10.32604/biocell.2023.026615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kramer, B., Rarey, M. & Lengauer, T. CASP2 experiences with docking flexible ligands using FlexX. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform.29(S1), 221–225 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rarey, M. et al. A fast flexible docking method using an incremental construction algorithm. J. Mol. Biol.261(3), 470–489 (1996). 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Daina, A. & Zoete, V. A boiled-egg to predict gastrointestinal absorption and brain penetration of small molecules. ChemMedChem11(11), 1117–1121 (2016). 10.1002/cmdc.201600182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hornak, V. et al. Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform.65(3), 712–725 (2006). 10.1002/prot.21123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van Der Spoel, D. et al. GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem.26(16), 1701–1718 (2005). 10.1002/jcc.20291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sousa da Silva, A. W. Vranken, ACPYPE-Antechamber python parser interface. BMC Res. Notes5, 1–8 (2012). 10.1186/1756-0500-5-367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Florová, P. et al. Explicit water models affect the specific solvation and dynamics of unfolded peptides while the conformational behavior and flexibility of folded peptides remain intact. J. Chem. Theory Comput.6(11), 3569–3579 (2010). 10.1021/ct1003687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jorgensen, W. L. et al. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys.79(2), 926–935 (1983). 10.1063/1.445869 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys.52(12), 7182–7190 (1981). 10.1063/1.328693 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hess, B. et al. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem.18(12), 1463–1472 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Turner, P., XMGRACE, Version 5.1. 19. Center for Coastal and Land-Margin Research, Oregon Graduate Institute of Science and Technology, Beaverton, OR, 2 (2005).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article as supplementary information files which include 1H and 13C NMR of synthesized compounds