Abstract

Glioblastoma is the most common and deadliest brain tumour in adults, with a median survival of 15 months under the current standard of care. Immunotherapies like immune checkpoint inhibitors and oncolytic viruses have been extensively studied to improve this endpoint. However, most thus far have failed. To improve the efficacy of immunotherapies to treat glioblastoma, new single-cell imaging modalities like imaging mass cytometry can be leveraged and integrated with computational models. This enables a better understanding of the tumour microenvironment and its role in treatment success or failure in this hard-to-treat tumour. Here, we implemented an agent-based model that allows for spatial predictions of combination chemotherapy, oncolytic virus, and immune checkpoint inhibitors against glioblastoma. We initialised our model with patient imaging mass cytometry data to predict patient-specific responses and found that oncolytic viruses drive combination treatment responses determined by intratumoral cell density. We found that tumours with higher tumour cell density responded better to treatment. When fixing the number of cancer cells, treatment efficacy was shown to be a function of CD4 + T cell and, to a lesser extent, of macrophage counts. Critically, our simulations show that care must be put into the integration of spatial data and agent-based models to effectively capture intratumoral dynamics. Together, this study emphasizes the use of predictive spatial modelling to better understand cancer immunotherapy treatment dynamics, while highlighting key factors to consider during model design and implementation.

Subject terms: Immunology, Computational biology and bioinformatics

Introduction

Glioblastoma is the most common and deadly primary brain tumour in adults1. Though combination surgical resection, temozolomide, and radiotherapy have provided survival benefits2, the median survival time for glioblastoma patients remains just 15 months even with these aggressive treatments3,4. Cancer immunotherapies encompass a variety of treatment modalities aimed at stimulating and targeting the immune response against tumours5,6. Though certain immunotherapies have been used for decades (e.g., Bacillus Calmette–Guerin to treat bladder cancer7), recent advances have propelled immunotherapies into the clinic for the treatment of both liquid and solid tumours5,6. Examples include adoptive T-cell transfers and CAR T cell therapy to treat leukaemias5,8 and sipuleucel-T to treat hormone-resistant advanced prostate cancer9. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) that block PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 pathways are also now extensively used for the treatment of several solid tumours10,11. In addition, oncolytic viruses (OVs) like talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), first approved in 2015 to treat advanced melanoma12,13, are promising immunotherapies under intense study. Each of these therapies have thus far provided significant benefits to patients in certain contexts but have been limited to specific tumour types.

Given the significant need for new treatment options in glioblastoma, several immunotherapy clinical trials (alone or in combination with temozolomide) have been performed14–17. These have largely focused on ICIs but also include oncolytic viruses. Trials testing the efficacy of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 ICI nivolumab in glioblastoma have all concluded without showing improvements to patient outcomes18,19. Recently, the OV teserpaturev (G47∆), a triple-mutated, third-generation oncolytic herpes simplex virus type 1, was approved in Japan after interim evaluation, achieving its primary endpoint (1-year survival rate) in a phase 2 intratumoral injection trial.

OVs are genetically engineered viruses that preferentially target tumour cells and play dual anti-tumoral roles20. First, they directly infect tumour cells causing lysis, which ejects virions into the tumour microenvironment (TME) allowing for continued infection of the surrounding cancer cells. In parallel, infected cells upregulate gene pathways to send signals of the infection to the immune system20. Through the interaction between antigen-presenting cells like dendritic cells and CD4 + T helper cells, cytotoxic CD8 + T cells are activated and begin killing infected cells, increasing overall tumour killing. A recent clinical trial of rQNestin21–23, an oncolytic HSV-1 virus to treat glioblastoma, reported safety data for glioblastoma patients and found that patients with the longest survival responses after the OV treatment were, amongst other things, characterised by differences in T-cell clonotype metrics and tumour transcriptomic signatures that are associated with immune activation programme23. However, besides G47∆ and T-VEC, OVs have not shown efficacy as a monotherapy24. Recent lines of study have thus focused on combination strategies (i.e., OV + chemotherapy, OV + immunotherapy, OV1 + OV2) to bolster their effects and overcome limitations any specific OV may have25. For example, dual OV therapy has focused on regimens administering viruses that provide localised infections (e.g., vaccinia virus) to enhance the efficacy of a second, more potent OV like vesicular stomatitis virus26–28. Experimental and modelling work have shown that this strategy may be beneficial if administered to the correct patient26.

Unlike OVs that work by activating CD8 + T-cell cytotoxicity through stimulation of anti-infection cytokine secretion, ICIs act to block checkpoint proteins from binding with their ligands29,30. Immune checkpoints are essential components of immune regulation. Their role is to maintain the delicate balance between immune response and self-tolerance. ICIs act by redirecting immune responses against tumour cells, thus increasing T-cell activation against cancer cells. However, sufficient numbers of T cells are required to provide an effective anti-tumoral response. The brain is not as immunoprivileged as once thought; recent evidence has brought to light the overall immune activity present in the central nervous system and its associate lymphatic system31. Nonetheless, the blood–brain-barrier and other physiological considerations22 represent impediments to immune activity in the brain, resulting in the reduced presence of most immune cell subtypes, including T cells. Recent experimental and computational modelling work have shown that the decrease in immune cells can explain the failures of ICIs in glioblastoma32. Thus, as in the case of oncolytic viruses, research has turned towards combining ICIs with other immunotherapies or small molecules to provide a longer-lasting treatment benefit to patients.

Given the difficulties in developing improved treatments for glioblastoma, mathematical and computational modelling have been deployed to identify mechanisms of treatment response and to implement and design combination immunotherapeutic strategies33–35. For example, for some time now, researchers have been using deterministic models of glioblastoma growth and treatment36–39. More recently, agent-based models (ABMs) have been used to model tumour growth26,32,40–43. Given this extensive support from the literature, the evaluation of the use of ABMs in the context of glioblastoma to investigate combination cancer treatments is timely and needed44.

We have recently constructed ABMs of rQnestin (oncolytic HSV-1) and combination nivolumab with temozolomide (TMZ) to determine the factors governing the success of these immunotherapies in glioblastoma. Jenner et al.26 developed an ABM capturing glioblastoma cell and stroma cell interactions during treatment by OV. Their work proposed that stromal density is a crucial driver of OV efficacy. Building from this platform, Surendran et al.32 investigated the efficacy of combining TMZ with ICI in the context of patient tumours. In this paper, we combined these models to illustrate how the integration of such models contributes to our understanding of the combination of oncolytic virotherapy and ICI for the treatment of glioblastoma. We combined new imaging mass cytometry (IMC) data45 to study the effects of combination immunotherapy for individual patients based on this spatial imaging modality. Our results show that an ABM initialised with patient-specific spatial data can effectively predict response to combination treatments as long as the initial cell count is high enough to allow the model to effectively capture at its full length the action of the adaptive immune system.

Results

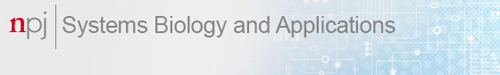

Oncolytic virus drives combination treatment responses

To characterise how a glioblastoma grows under monotherapies or combination treatments, we simulated different treatment regimens with the ABM initialised from IMC data for six patients. To consider the cell distribution heterogeneity and how it may affect the treatment response, we identified the three patients with the lowest (Patients B1, B2 and B3) and the three patients with the highest adaptive immune cell proportions (Patients T1, T2 and T3) (see “Methods”). Figure 1a, b describes the respective cell distributions of our subgroup of patients. On average, they had 3085 initial cells. Importantly, patients B1, B2 and B3 did not have any adaptive immune cells in their respective IMC profiles; they also exhibited lower initial macrophage proportions than Patients T1, T2 and T3 (21.79% vs 67%) and had higher relative proportions of glioblastoma cell proportions (76.82% vs 25.56%). All patients had similar initial stromal cell proportions.

Fig. 1. Agent-based simulations of various combination treatments for six heterogeneous patients.

a Cell distributions of six patients, in percentage of all cells in the TME. b Total initial cell counts for each of the six patients. c Fold change in cancer cells after 7 days depending on the administered treatment. Fold changes on the right of the red dotted line represent an increase in cancer cells over the simulated period, while fold changes on the left of the line show a decrease in cancer cells. d Change in cancer cells as the percentage of initial cell count. Solid lines represent the average of the ten replicates per patient. Shaded areas show the standard deviation of the ten replicates.

For both subgroups, our model predicted that none of the patients responded substantially to TMZ or ICI in monotherapy, but that all patients showed a robust response to the OV treatment, whether given in monotherapy or in combination with TMZ and/or ICI. The difference in treatment response between OV monotherapy and combination therapy was minimal, suggesting that the OV is the driver of treatment efficacy.

To evaluate differences in treatment efficacy, we looked at the fold change in cancer cells after seven days for all patients, depending on the treatment regimen (Fig. 1c). The fold change quantifies changes in cancer cell numbers with respect to their initial count. Patients B1, B2 and B3 appeared to have a generally lower final cancer cell fold than Patients T1, T2 and T3. This is surprising, given that the former have no adaptive immune cells and that our previous work32 has shown that patients with higher numbers of cytotoxic T cells respond better to ICIs. Patients B1, B2 and B3 had slightly more initial cells than patients T1, T2 and T3, with an average of 3687 cells for B1-B3 compared to 2483 cells for T1–T3 (Fig. 1b). Crucially, all patient samples had fewer than 3768 initial cells, whereas most simulations performed in ref. 32 had 17,756 initial cells. Thus, we speculated that a small initial cell count could affect the prediction of the ABM.

Higher initial cell counts are needed to model adequately the adaptive immune system

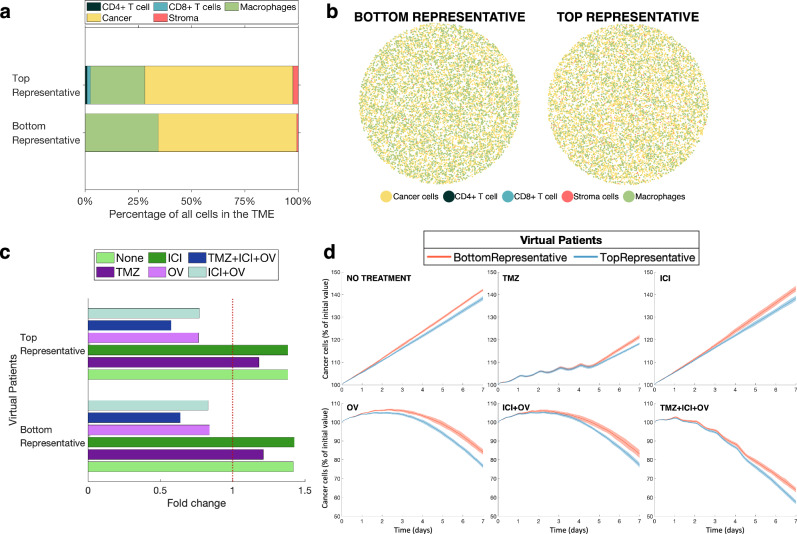

To test the impact of the initial cell count on predicted treatment outcomes, we simulated the same treatment combinations for our two representative samples with 10,000 initial cells (see “Methods”). BottomRepresentative had no initial adaptive immune cells and fewer initial cancer cells than the TopRepresentative. However, BottomRepresentative had more macrophages (Fig. 2a), and both had a similar number of stromal cells.

Fig. 2. Agent-based simulations of various combination treatments for two representative virtual patients.

a Distributions of cells as a percentage of all cells in the TME for the two representative virtual patients. b Initial cell configuration of two representative tumours (BottomRepresentative and TopRepresentative). c Fold change in cancer cells after 7 days depending on administered treatment. Fold changes on the right of the red dotted line represent an increase in cancer cells over the simulated period, while fold changes on the left of the line show a decrease in cancer cells. d Cancer cells evolution in percentage of initial cell count. Solid lines represent the average of the ten replicates per virtual patient. Shaded area shows the standard deviation of the ten replicates.

Similar to the six patient samples, both representative samples were not predicted to respond to the ICI given in monotherapy, which is in agreement with results from clinical trials of ICIs15,46,47 and similar to the results in ref. 32. Although we still observed glioblastoma cell growth during TMZ in monotherapy, the fold increase was smaller than in the simulations of the six patient samples (Figs. 1c and 2c). For treatment regimens that included the OV, we found that the TopRepresentative virtual patient ended the 7-day simulation period with fewer cancer cells (with respect to the percentage of initial cancer cell count) than BottomRepresentative. This is consistent with our expectations, since TopRepresentative had a higher initial adaptive immune cell proportion than BottomRepresentative. Thus, the ABM prediction accuracy appears to be dependent on the total cell count at initialisation, especially when it comes to the impact of the adaptive immune system. This shows that IMC data can allow for patient-specific predictions if they are first processed to increase the number of cells while maintaining the same initial cell distributions.

We found key differences between the cell distributions of patients B1, B2, B3, T1, T2 and T3, and the cell distributions of BottomRepresentative and TopRepresentative, especially with respect to macrophages (Figs. 1a and 2a). Indeed, patients T1, T2 and T3 (i.e., those with an adaptive immune system) had more macrophages than cancer cells, whereas both representative patient samples had the reverse. The fact that the representative patient without an adaptive immune system (BottomRepresentative) had more macrophages than TopRepresentative who had cells from the adaptive immune system in their sample is also not in accordance with Patients B1, B2 and B3 having lower initial macrophages proportions than Patients T1, T2 and T3. These differences can be explained by the heterogeneous nature of the data, which is intrinsically linked to glioblastoma being a highly heterogenous tumour48. Since patients B1, B2, B3, T1, T2 and T3 are the six patients at both ends of the adaptive immune cell proportion spectrum, they differ from BottomRepresentative and TopRepresentative considering that the latter represent the proportions of the median bottom and top 10% of 145 patients, respectively. Despite these differences in the proportions of innate immune cells, we still observed that the presence of the adaptive immune response is important in treatment outcomes49.

Treatment response correlates with intratumoral cell density

To better assess how the initial number of total cells in the simulation impacts on predicted treatment outcomes, we used the average growth speed of the tumour cells (, see “Methods”). For treatments that included the OV, we observed that the cancer cell fold increase was smaller in the six patients than in the two representative samples. However, it is important to exercise caution when interpreting the results, as the fact that the six patient simulations were predicted to respond more to the treatments does not necessarily imply that this result will bear out in reality. This is because the IMC data used for the analysis had less than half the total number of cells compared to the representative samples that we generated.

Figure 3a shows the normalised heatmap for various inputs and outputs of the simulations. From this analysis, we found that when patients B1, B2, B3, T1, T2 and T3 were treated with the OV in mono- or combination therapy, there was a negative correlation between cancer cell density and the speed of growth and a positive correlation between the percentage of white space and the growth speed (Fig. 3b). A higher percentage of white space means that the tumour has a lower cell density. A higher growth speed represents a smaller response to treatment. These results would mean that denser tumours, in terms of cancer cells and of all cells, respond more to the oncolytic virus. This is similar to the results of ref. 22. where tumours with higher tumour cell density were found to respond better to the OV treatment. This correlation was also observed in our two representative samples. In these simulations, TopRepresentative had a higher initial percentage of cancer cells than BottomRepresentative. Since both virtual patients had the same initial same count, this implies that TopRepresentative had a higher tumour cell density than BottomRepresentative.

Fig. 3. Correlations between simulations inputs and combination treatment outputs.

a Heatmap of the inputs and outputs of all the simulations. Values in every column were min–max normalised, i.e., 0(1) represents the minimum(maximum) value for the column. b Correlation plot between the simulations’ characteristics. Pearson correlation coefficients with a P value (t test) smaller than 0.05 are denoted by an asterisk symbol (*). P values were calculated using Matlab’s function corrcoef. Corrcoef computes P values by transforming the correlation to create a t statistic having degrees of freedom, where is the number of rows of the correlation table. Here, .

For all treatments, TopRepresentative’s growth speed was found to be smaller than BottomRepresentative’s. Figure 3b shows the correlation coefficients between all the considered inputs and outputs of the simulations. We found that the growth speed when treated with the OV, TMZ and the ICI in monotherapy, or with a TMZ + ICI + OV combination treatment was significantly negatively correlated with the tumour cell density.

Treatment efficacy depends on glioblastoma cell count and is influenced by CD4 + T cell numbers

To test which cell types drive the combined treatment efficacy, we simulated the TMZ + ICI + OV treatment on ABMs with an initial cell count of 5000 and varied one cell type at a time in increments of 1000 cells (see “Methods”). We found that increasing the number of cancer cells results in increased efficacy of treatment (Fig. 4a). We hypothesise that this is due to the OV being the driver of treatment efficacy, meaning that an increased number of tumour cells implies more viral production through infection. In fact, the amount of virus increases as the number of cancer cells increases (Fig. 4b). Fixing the amount of cancer cells reveals that treatment efficacy is also largely a function of the CD4 + T-cell count and, to a lesser extent, of the macrophage count.

Fig. 4. Impact of cell types on agent-based combination treatment simulations (TMZ+ICI+OV).

a Fold change in cancer cells after 7 days depending on the total number of cells and on which cell type was increased. Values were min–max normalised over the entire table. A fold change equal to 1 represents the smallest response to treatment, while a fold change equal to 0 represents the best response. b Virus density over the simulation 7 days according to the total number of cells. Only cancer cells were increased in these simulations. Solid lines represent the average of the three replicates, and shaded areas show the standard deviations.

Discussion

This study examined how computational models can integrate new spatial data in the form of imaging mass cytometry (IMC) to study combinations of treatments involving immunotherapies in the context of glioblastomas. Immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) is an extremely promising cancer therapy, with recent successes in clinical trials in a variety of solid tumours, including melanoma, lung, breast, and colon cancers. Recent evidence points towards combination therapy with ICIs as being a promising avenue for improving their efficacy as an anti-cancer treatment. Unfortunately, in glioblastomas, combinations of ICIs with OV or TMZ have thus far failed to show efficacy. Fortunately, computational modelling can allow us to predict patient responses to therapy to attempt to understand why and how combination therapies fail. In cancers with high intratumoral heterogeneity, such as glioblastomas, agent-based models are particularly useful since they simulate each cell individually in their local microenvironment and neighbourhood, and provide predictions on spatial interactions, which is critical to improving our understanding of treatment response.

To understand how promising new immunotherapies treat glioblastoma, we extended our previous ABMs26,32 to analyse and compare the response of glioblastomas to three monotherapies (TMZ, ICI and OV) and two combination therapies (ICI + OV, TMZ + ICI + OV). New IMC data allowed for the individualisation of our agent-based models and thus patient-specific predictions. Based on these, we found that monotherapies with TMZ and ICI were ineffective, which is consistent with clinical results. In contrast, however, we found the OV to be highly effective, and seemingly the driving force behind mono- and combination treatment efficacy. As revealed through our simulations with larger representative sample sizes, this is in line with the fact that the response to treatment was predicted to be dependent on the number of cancer cells present, as a higher count of such cells can lead to an increased spread of infection. The stark difference we observed between the treatment outcome with TMZ and OV could potentially be explained by the way these therapies are administered, given that the OV was modelled to be administered at the centre of the domain (intratumoral injection) while TMZ infuses in from the periphery. Future investigations could include integrating analysis of the tumour vasculature into our ABM to account for potential differences in therapeutic outcomes due to drug administration routes and microvascular density. Nonetheless, of the immunotherapies tested in glioblastoma, only OVs have thus far shown potential promise and have been approved for treatment, which is accurately captured by our model’s predictions.

Care must be taken when analysing the patient-specific predictions. Indeed, the patient datasets studied herein, while extremely rich and informative, only represent a subsection of a patient’s tumour and thus contain fewer cells than a complete tumour. With these lower cell counts, the model does not sufficiently reproduce the action of the adaptive immune system, which results in the patients with the highest initial adaptive immune cell proportions responding less than those with the lowest initial adaptive immune cell proportions. This result contradicts previous articles that concluded that treatment efficacy relies on a strong adaptive immune system32, and with our understanding of the mechanisms of actions of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

In the virtual representative samples with higher initial cell counts, we still observed that the OV drove treatment efficacy. However, the model better captured the adaptive immune response, as the TopRepresentative (with the higher initial adaptive immune cell proportion) was predicted to have a greater treatment response than the BottomRepresentative, who had the lowest initial proportion of adaptive immune cells. These results suggest that there is a relationship between the domain size and the ABM’s predictions, and that a high enough initial cell count is required to make coherent predictions. Hence, our study highlights that although clinical data are pivotal to individualise predictive computational models, it is critical to ensure that these data are properly assessed and evaluated within the context of a mechanistic, spatial model. This work suggests paths forward for the scale-up of portions of tumour samples to provide accurate model predictions by, for example, increasing the initial cell count from IMC samples to create simulations that remain representative of patient heterogeneity.

Our previous work predicted that a higher count of cytotoxic CD8 + T cells in the TME leads to an increase in immunotherapy effectiveness32. Interestingly, our model predictions showed that treatment efficacy was more correlated with CD4 + T cell numbers than with CD8 + T cell counts. This is largely consistent with our finding that the OV was the strongest driver of treatment response since CD4 + T cells are activated through interactions with a tumour cell in their neighbourhood and secrete chemokines, once activated, that recruit cytotoxic CD8 + T cells to the site of the tumour. Further, CD4 + T cells are also involved in macrophage interactions during OV treatment. Thus, we hypothesise that CD4 + T cells were found to be important for treatment responses due of their coordinating role. As such, they could potentially be interesting targets for treatments combining TMZ, ICI and an OV.

Together, this work demonstrates the use of spatial modelling approaches to understand whole tumour dynamics and the treatment of spatially heterogeneous tumours like glioblastoma. Computational models are increasingly integrated within drug development and clinical decision-making. As experimental data increase in precision and specificity, it is imperative to understand the capacities and limitations of current computational modelling modalities, including agent-based models, to ensure their predictability and reliability. Ultimately, a fully integrated process starting from clinical empirical knowledge ending with computationally driven predictions will allow for the optimisation of treatment strategies and to expedite the bench-to-bedside translation of combination regimens in glioblastoma and beyond.

Methods

Agent-based model of glioblastoma

We recently developed an ABM for glioblastoma growth and treatment with either an OV22, or an ICI and TMZ32 in PhysiCell, an open-source cell-based simulator50. In this framework, cells are considered agents and move off-lattice in a 2D domain with movement governed by a series of force-balance equations. Substrate diffusion, secretion and uptake are modelled as a system of partial differential equations (PDEs) using BioFVM51. BioFVM is a biotransport solver that simulates diffusing substrates and cell-secreted signals in the microenvironment. With BioFVM, cells also update their phenotype depending on their local microenvironment conditions. PhysiCell has extensive documentation and numerous extensions and examples of applications52–55. Here, we briefly describe our main modelling assumptions from our previous glioblastoma growth, OV, TMZ and ICI models.

Our model assumes we have five main cell types: glioblastoma cells, CD8 + T cells, CD4 + T cells, macrophages, and stromal cells (Fig. 5a). There are four substrates considered in the model: OV, chemokine, ICI, and TMZ, all of which are modelled by the BioFVM PDE:

| 1 |

where is the diffusion coefficient, the decay rate, the secretion rate with maximum density , is the uptake rate, the cell volume, the cell position. All estimates for these parameters can be found in our previous work22,32.

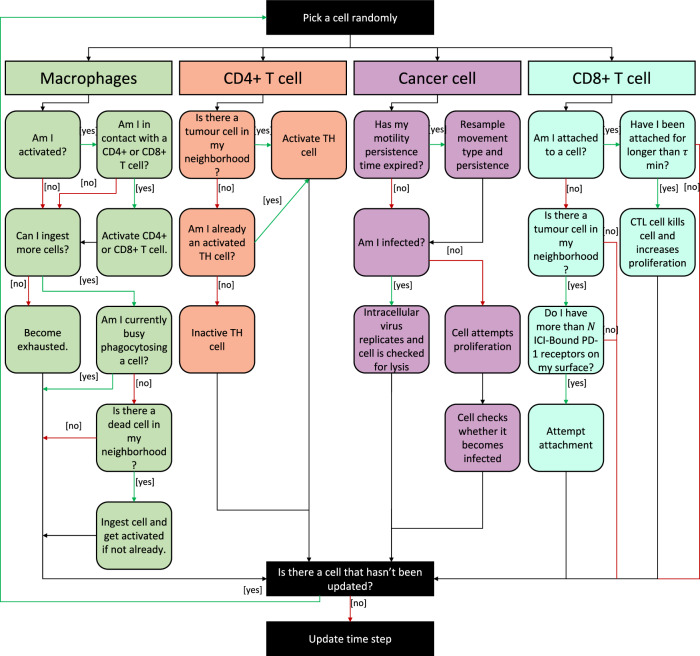

Fig. 5. Model and treatment schematics.

a ABM describing combination treatment with TMZ, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, and an HSV-1 oncolytic virus. b We simulated the first seven days of treatment wherein the patient first receives a single administration of the oncolytic virus with the anti-PD-1 agent administered over the first hour; TMZ is given orally on days one to five. To account for the oral administration of TMZ, we use a three-compartment pharmacokinetic model to describe drug concentrations in the gastrointestinal tract, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid. Details can be found in “Treatment with temozolomide”. The oncolytic virus dosage depends on the initial cell count and is equivalent to a dose of 5 plaque-forming units (PFU) per cell for 9740 cells. PFU is a measure of virus quantity used in virology. More details on how PFU relates to viral dose size are given in “Treatment with an oncolytic virus”.

As mentioned above, cells are considered individual agents that each have their own set of rules for their interactions with other cells as well as their local microenvironment. At every cell update timestep, the simulator randomly picks a cell and goes through a decision tree to determine its outcome at the next timestep (Fig. 6). Once the cell is updated, another cell is randomly selected, and this process continues until all the cells have been updated. The decision tree used in this paper is the combination of the two decision trees from our previous models22,32.

Fig. 6. Flow chart of the decision tree implemented for the update of cells in the agent-based model of glioblastoma.

In each cell time step, a cell agent in the simulation is chosen at random and, based on its cell type, follows a series of decision tree rules. The time step is updated only once all cell agents have been evaluated.

We briefly describe the core rules of the model. Glioblastoma cells proliferate at a baseline rate . The probability for a glioblastoma cell to proliferate depends on the local cell density: if an individual cell is too crowded, it will not proliferate. The local cell density is correlated to the mechanical pressure from neighbouring cells. As in ref. 22, we use PhysiCell’s inbuilt cell–cell pressure calculation to compute the mechanical pressure felt by an individual cell. We define a mechanical pressure threshold and cells proliferate at a rate if their mechanical pressure from neighbouring cells is less or equal to this threshold. For a given cell , PhysiCell defines its set of neighbours as the list of cells located in neighbouring voxels, i.e., those that share an edge with ’s current voxel, and the cells in ’s current voxel22,50.

Glioblastoma cells die in three main ways: (1) a cell becomes infected by an oncolytic viral particle and dies through lysis, (2) TMZ induces cell death (see “Treatment with temozolomide”), and (3) a CD8 + T cell induces apoptosis26,32. Macrophages are activated once they phagocytose a dead cell, after which they can activate a CD4+ or a CD8 + T cell in their neighbourhood and ingest a certain number of cells; they then become exhausted, and their death rate is increased. CD4 + T cells become activated through interactions with a tumour cell in their neighbourhood. Once activated, they secrete chemokines that recruit CD8 + T cells to the site of the tumour. In the presence of an anti-PD-1 treatment, if the CD8 + T cell has more than ICI-bound PD-1 receptors on its surface, it can attach itself to tumour cells in its neighbourhood. Once a CD8 + T cell has been attached for more than minutes, it kills the tumour cell. We refer readers to ref. 32 and ref. 22 for complete details.

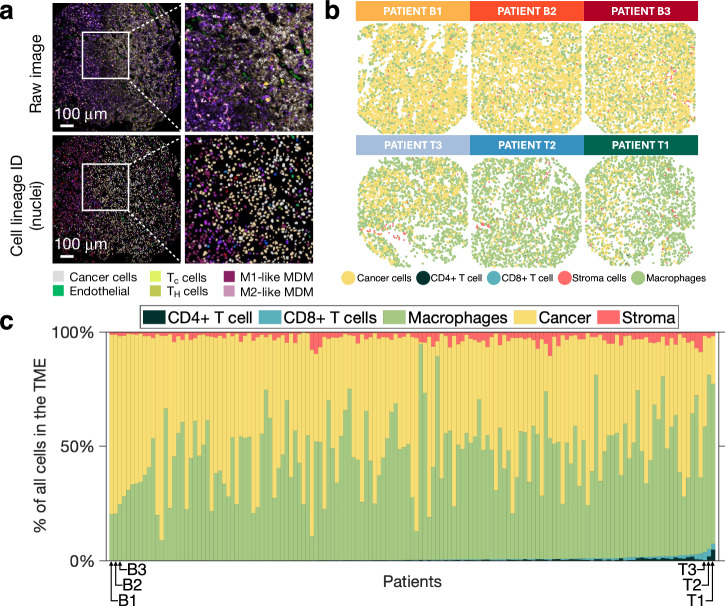

Initialisation of the glioblastoma model with IMC data

To initialise the tumour in our ABM, we incorporated IMC data of tumour resections from untreated glioblastoma patients from ref. 45. All data are published and publicly available; a complete description with details of ethics oversight is available in ref. 45. As described in ref. 45, written informed patient consent was obtained prior to collecting surgical specimens and clinical information. IMC on glioblastoma patient samples was performed as previously described by Karimi et al.45 and Surendran et al.32. We used spatial data from ref. 45 to localise cancer cells, macrophages, CD4 + T cells, CD8+ cells, and endothelial cells that we considered to be stromal cells56, and implemented it into our agent-based model to individualise the simulations (Fig. 7). Since microglia cells and macrophages have similar functions in the glioblastoma TME and are often recognised as one cell cluster57,58, we included microglia within the macrophage category.

Fig. 7. From Imaging mass cytometry data to an individualised agent-based model.

a IMC images from Karimi et al. (top) and corresponding lineage assignment (bottom), with magnified regions to the right of each image. Image reproduced under Creative Commons. b Initial spatial configurations of six chosen IMC data samples. The six IMC samples were chosen according to their adaptive immune cell proportions. Thus, we first ranked patients in our cohort by their initial CD4+ and CD8 + T cells proportions. In the case where two patients had the same initial adaptive immune cell proportions, we ranked patients according to the respective initial macrophage proportions. We then selected the bottom three patients (B1–B2–B3) and the three top patients (T1–T2–T3) as representative individuals. c Cell distributions of 145 patients in the percentage of all cells in the TME, measured in IMC. Patients are ordered according to their adaptive immune cell proportions (CD4+ and CD8 + T cells), in ascending order from left to right. Distributions corresponding to the six chosen patient samples are indicated with arrows.

IMC images were all 1 mm2. Supplementary Table 1 summarises patient-related data. Samples contained between 910 and 6033 total cells and displayed a high degree of heterogeneity in the distributions of cell populations as a percentage of all cells in the TME (Fig. 7). The proportion of adaptive immune cells (CD4 + T cells and CD8 + T cells) varied between 0% and 7.38%, with an average of 0.66%. On the other hand, samples had, on average, a cancer cell proportion of 50.25%, ([0.84%; 89.54%]). Stromal cell proportions were between 0.2% and 10.54%, with an average of 2.87%. Finally, macrophages made up between 8.79% and 94.38% of samples, with an average of 46.23%.

Treatment with temozolomide

We used the same TMZ pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model as in ref. 32. To predict TMZ concentrations in the cerebospinal fluid (CSF), we used a three-compartment model with first-order absorption in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) from ref. 59. TMZ pharmacokinetics were modelled according to

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

where , and are the amount of TMZ in the GIT, plasma, and CSF compartments, respectively (with and the TMZ concentrations in the plasma and the CSF compartments), is the absorption rate, and are the rates of exchange from the plasma to CSF and from the CSF to plasma, respectively, is the TMZ clearance, is its volume of distribution in the central compartment, and is its volume of distribution in the CSF compartment. The integration of this three-compartment model into the ABM and the variations in local TMZ concentrations tracked by the BioFVM biotransport system are detailed in ref. 32.

TMZ is considered to be primarily cytostatic60 and to induce cell death in proliferating cells by arresting their cell cycle61. As such, we assumed that TMZ results in reduced proliferation and in increased death of glioblastoma cells. As in ref. 32, the cytostatic effect of TMZ on glioblastoma cells can be described by the following three equations:

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

Here, is the number of glioblastoma cells, is the temozolomide concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid, and is the number of dead cells after cell cycle arrest induced by TMZ. Finally, is the half effect of TMZ. Surendran et al.32. adapted this system of equations to model stochastic cell division and death with PhysiCell’s inbuilt “Live” and “Apoptosis” models50. According to the “Live” cell division model, a cell can divide with a division rate such that in a given time interval, , the probability of cell division is given by Ghaffarizadeh et al.50

| 9 |

As in ref. 32, we defined . Similarly, the ”Apoptosis” model defines the probability of a cell dying in the time interval to be50

| 10 |

with representing the death rate. Based on ref. 32 in our model, the death rate of glioblastoma cells is given by . Surendran et al.32 fitted the standard Emax effects curve to dose–response data from ref. 62 and found an estimate of .

Since TMZ reduces the probability of cell division of proliferating glioblastoma cells, it has no effect on cells whose proliferation is already blocked for another reason, such as infection by an oncolytic virus. Given that we lack specific data of combination HSV-1 oncolytic virus with TMZ, we consider this modelling choice to effectively capture the OV treatment in combination with TMZ while preventing our model from overpredicting the combined effect of therapy.

As we did in our previous model, we considered a dosing schedule where 175 mg/m2/day of TMZ was administered for 5 consecutive days, which is consistent with standard-of-care for glioblastoma2,32,59. Supposing an average adult male has a body surface area of 1.9 m2, this dosing schedule corresponds to 332.5 mg of TMZ per day for 5 days.

Treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors

We kept the same glioblastoma growth model with a treatment with nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 drug, as in our initial TMZ + ICI model32, which was based upon a previous model published by Storey et al.63. For each time (in minutes) at which nivolumab is administered,

| 11 |

where is the source of anti-PD-1 drug concentration as a function of time. Variations in the local concentration of the anti-PD-1 drug () are tracked by the BioFVM partial differential equation

| 12 |

as detailed in ref. 32. and are the ICI diffusion coefficient and decay rate, respectively. The standard administration schedule of nivolumab is a single intravenous dose of mg every two weeks administered for one hour32,63. As we performed 7-day long simulations, we administered nivolumab for the first hour of the simulations.

As in ref. 32, we assumed that CD8 + T cell induced apoptosis in glioblastoma patients can only occur when the number of ICI-bound PD-1 receptors on a T cell is above a threshold . For each CD8 + T cell, its number of ICI-bound () and unbound () receptors is tracked by

| 13 |

| 14 |

where and are the binding rates, and is the amount of nivolumab in the local microenvironment of the CD8 + T cell tracked by Eq. (13), as detailed in ref. 32.

Treatment with an oncolytic virus

The OV was administered as a single dose in the centre of the domain, in a circular region with a radius of , at the beginning of the simulations. Given that some of the patients’ IMC samples had blank spaces containing none of the cells considered in our study, to make sure that we administered the OV into a region that contains cells, we found the position of the closest cell to the centre of the domain and set its - and - positions as and , respectively. The OV was then administered in the region

meaning that every voxel in has an initial viral concentration equal to .

Details of the OV integration in the ABM can be found in ref. 22. As in ref. 22, we assumed a one-to-one relationship between the number of virions and plaque-forming units (PFU). PFU quantify the number of viral particles needed to produce one plaque by lysis after infection. In ref. 22, simulations were performed with 9740 initial cells and viral dosages of 5 plaque-forming units (PFU) per cell. Since the patient datasets used in our work had an unequal number of initial cells, we calculated the viral dosages (i.e., the PFU specific to patient ) according to

| 15 |

where is the initial number of cells in patient ’s sample. The initial viral concentration administered for patient is thus given by

| 16 |

where is the radius of the regions of administration (). At the beginning of the simulations, every voxel in as an initial viral concentration equal to , while every voxel outside of have an initial viral concentration equal to .

Patient sample stratification and simulations

Our previous TMZ + ICI model showed that patients with higher numbers of cytotoxic T cells within their tumour respond better to treatment with ICIs32. With this in mind, we ranked patients according to their initial adaptive immune cell proportion (i.e., CD4+ and CD8 + T cells) (Fig. 7c). Adaptive immune cell proportion ties were broken according to the macrophage proportions. We then picked the three patients with the lowest adaptive immune cell proportions (patients B1, B2 and B3), and the three patients with the highest adaptive immune cell proportions (patients T1, T2 and T3), and initialised an ABM for each of these patients according to their respective IMC data (Fig. 7b). Patient data for these samples are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

For each of the six patients, we simulated the model without treatment, as well as five different combination treatments: TMZ, ICI, OV, OV + ICI and TMZ + ICI + OV (Fig. 5). Since an ABM is a stochastic model, two simulations with the same input will not produce the same output. Thus, for each treatment regimen of interest, we performed ten runs of our model and used the average when analysing outcomes. Based on our previous results32, we would expect patients T1, T2 and T3 to respond better to treatment combination schemes that include immunotherapies since these patients have a higher proportion of adaptive immune system compared to patients B1, B2 and B3.

Simulations of representative patients

To study the effects of increasing the domain size and the initial number of cells, we generated two virtual patients. To generate both representative patients, we found , the average proportion of the domain that contains cells in all the 145 patients’ samples and defined as the average cell radius between the five considered cell types (macrophages, CD4 + T cells, CD8 + T cells, tumour cells, and stroma cells). We then calculated , the circular domain radius needed such that a proportion of contained cells when populated with 10,000 cells of radius equal to .

We ranked the patients according to their initial adaptive immune cell proportion and generated a representative patient sample with 10,000 cells (BottomRepresentative) that respects the proportions representing the initial adaptive immune cell proportion of the median patient of the bottom 10% of the cohort with respect to the order described earlier (Fig. 7c). Similarly, we also generated a representative sample consisting of 10,000 cells that maintained the proportion (TopRepresentative—initial adaptive immune cell proportion of the median patient of the top 10% of the cohort). For both BottomRepresentative and TopRepresentative, cells were assigned an initial position in the domain according to a uniform distribution.

As with the six patients’ samples, we simulated these representative samples ten times under the same treatment combinations (i.e., No treatment, TMZ, ICI, OV, OV + ICI, TMZ + ICI + OV). For both representative samples, and the region of OV administration were calculated as described in “Treatments with an oncolytic virus”. Schedules of administration for our 7-day long simulations are described in Fig. 5b.

Confirmation of the model’s predictive capacity

Both the TMZ + ICI and the OV models were validated with data in our previous work by Surendran et al.32 and Jenner et al.22, respectively. Given that they generally respond more to checkpoint blockade than patients with primary glioblastoma19,32,64, Surendran et al.32 used samples from metastases from patients with primary lung cancers, breast cancers, and melanomas32 and found that brain metastases exhibited significantly higher CD8 + T-cell counts, which was one of their predicted features of better responders. Their model predictions also showed that brain metastases responded better to ICIs, which is consistent with clinical observations65.

The OV model was calibrated to a number of in vitro, in vivo and ex vivo datasets, and predictions from the model were further validated against clinical measurements22. For example, the OV model suggests that increasing the diffusivity of an oncolytic virus and/or decreasing its clearance would significantly improve treatment efficacy. This was consistent with evidence that arming OVs with a transgene degrading the extracellular matrix, such as hyaluronidase66,67, decorin68,69, or relaxin, improves viral spread and enhances viral potency. Also, in glioblastoma, OV clearance was linked to natural killer cells that cause diminished OV-efficacy70. Inhibiting the recruitment of natural killer cells by combining TGB- and the oHSV OV showed increased viral efficacy71 .

To confirm our combination model’s predictive capacity, given the lack of data on the TMZ + OV + ICI combination, in this study we selected six patients’ samples based on their adaptive immune cells proportions to make predictions for two immune system extreme scenarios: patients with a weak adaptive immune system and patients with the strongest immune response. Similarly to the six chosen patients’ samples, the two virtual domains (Top and Bottom Representatives) illustrate these two immune system extreme scenarios (i.e., weak versus strong adaptive immune system). Doing so allowed us to confirm our model’s predictions aligned with biological expectations since we know that the increased presence of adaptive immune cells (i.e., CD4+ and CD8 + T cells) enhances ICI efficacy32.

Statistical analyses

For each patient sample (IMC and representative), the fold increase in cancer cells for an administered treatment was defined as

| 17 |

for , with the number of cancer cells after days of simulation with treatment . Since we were interested in the association between model inputs and predictions of the different initialisations of the ABM, we measured correlations between the eight different model initialisations (real or representative patient) and various characteristics (input or output) of the simulations. The correlation coefficient between characteristics and , was defined as the Pearson correlation coefficient, i.e.,

where is the covariance between the two characteristics, and is the standard deviation of characteristic . Statistical significance was defined at , and correlations were measured using corrcoef in Matlab2023b72. corrcoef computes P values with a t test by transforming the correlation to create a t statistic having degrees of freedom, where is the number of rows of the correlation table. Here, . It tests the null hypothesis that there is no relationship between the observed phenomena. The P value is the probability of getting a correlation as large as the observed value by random chance when the true correlation is zero.

For the input characteristics, we looked at the total initial cell count, the initial proportion of each of the different cell types, the initial percentage of blank space in the model, and the initial tumour density. For the output characteristics, we defined treatment response as the average growth speed of the tumour cells

| 18 |

where is the tumour cells growth speed of the simulation under the simulated treatment and is defined as

with

If , then and represents the average killing speed of the tumour cells. In this case, the smaller the value of is, the more patient responds to . Conversely, if , then the cancer has grown over the simulated period.

We defined the percentage of white space as the percentage of the initial tumour area that does not contain any of the cell types included in this study, i.e.,

| 19 |

To adequately assess differences across different conditions, we min–max normalised across the columns. Let and be the not normalised and normalised tables of characteristics, respectively. Then,

| 20 |

where refers to the (min–max normalised) value of the characteristic for the initialisation. In this way, all values in are between and .

Effects of increasing cell types

To identify the effect of each cell type on the response to a TMZ + ICI + OV combination treatment, we generated a virtual patient with 5000 cells according to patient T1’s cell distributions. Cells were assigned an initial location uniformly within a circular domain of the same radius as BottomRepresentative and TopRepresentative. Then, we increased the number of cells up to 10,000 in increments of 1000, varying only one cell type at a time. Additional cells were also assigned an initial location uniformly within the same domain. To analyse the variation in treatment response, we looked at the fold change in cancer cells as defined by Eq. (18). Results were stored in a table where the element in position (i.e., ) represented the fold change in cancer cells when cells of type i are added to the 5000 initial cells. The table was then min–max normalised, i.e.,

| 21 |

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the patients who participated in this study. B.M. was funded by Fonds de recherche du Québec-Nature et Technologies and Natural Sciences and Research Council of Canada Master’s scholarships and funding from the Université de Montréal. J.H.D. was supported by a Bourse d'été de premier cycle from l’Institut des sciences mathématiques and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant RGPIN-2018-04546 to M.C. I.M.C. was supported by the Brain Tumor Funders’ Collaborative (D.F.Q. and L.A.W.). M.C. is an FRQS J1 Research Scholar and was supported by the Fondation du CHU Sainte-Justine. Funders played no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author contributions

B.M.: participated in research design, conducted experiments, contributed new reagents or analytic tools, performed data analysis and wrote the manuscript. J.H.D.: contributed new reagents or analytic tools and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. A.S.: contributed new reagents or analytic tools and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. E.K.: conducted experiments and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. B.F.: conducted experiments andf contributed to the writing of the manuscript. D.F.Q.: conducted experiments, contributed to the writing of the manuscript and secured funding. L.A.W.: conducted experiments, contributed to the writing of the manuscript and secured funding. A.L.J.: participated in research design, conducted experiments, contributed new reagents or analytic tools, wrote the manuscript and supervised the study. M.C.: participated in research design, performed data analysis, wrote the manuscript, secured funding and supervised study.

Data availability

Datasets resulting from simulations and needed for reproducing figures in the current study are available on Github: https://github.com/blanchemongeon/ABMGBM. Any further datasets are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The computational code to implement our agent-based model is available on GitHub at https://github.com/blanchemongeon/ABMGBM.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. M.C. is an associate editor but played no role in the peer review process of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41540-024-00419-4.

References

- 1.Wirsching, H.-G. & Weller, M. Glioblastoma. In Malignant Brain Tumors: State-of-the-Art Treatment (eds. Moliterno Gunel, J. et al.) 265–288 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2017).

- 2.Stupp, R. et al. Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. New Engl. J. Med.352, 987–996 (2005). 10.1056/NEJMoa043330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madani, F., Esnaashari, S. S., Webster, T. J., Khosravani, M. & Adabi, M. Polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery in glioblastoma: state of the art and future perspectives. J. Controlled Release349, 649–661 (2022). 10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delgado-López, P. D. & Corrales-García, E. M. Survival in glioblastoma: a review on the impact of treatment modalities. Clin. Transl. Oncol.18, 1062–1071 (2016). 10.1007/s12094-016-1497-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dana, H. et al. CAR-T cells: early successes in blood cancer and challenges in solid tumors. Acta Pharmaceutica Sin. B11, 1129–1147 (2021). 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guha, P., Heatherton, K. R., O’Connell, K. P., Alexander, I. S. & Katz, S. C. Assessing the future of solid tumor immunotherapy. Biomedicines10, 655 (2022). 10.3390/biomedicines10030655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herr, H. W. & Morales, A. History of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin and bladder cancer: an immunotherapy success story. J. Urol.179, 53–56 (2008). 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garber, H. R., Mirza, A., Mittendorf, E. A. & Alatrash, G. Adoptive T-cell therapy for Leukemia. Mol. Cell Ther.2, 25 (2014). 10.1186/2052-8426-2-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kantoff, P. W. et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. New Engl. J. Med.363, 411–422 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Wojtukiewicz, M. Z. et al. Inhibitors of immune checkpoints—PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4—new opportunities for cancer patients and a new challenge for internists and general practitioners. Cancer Metastasis Rev.40, 949–982 (2021). 10.1007/s10555-021-09976-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandey, P. et al. Revolutionization in cancer therapeutics via targeting major immune checkpoints PD-1, PD-L1 and CTLA-4. Pharmaceuticals15, 335 (2022). 10.3390/ph15030335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trager, M. H., Geskin, L. J. & Saenger, Y. M. Oncolytic viruses for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol.21, 26 (2020). 10.1007/s11864-020-0718-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haitz, K., Khosravi, H., Lin, J. Y., Menge, T. & Nambudiri, V. E. Review of talimogene laherparepvec: a first-in-class oncolytic viral treatment of advanced melanoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.83, 189–196 (2020). 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown, C. E. et al. Bioactivity and safety of IL13Rα2-redirected chimeric antigen receptor CD8+ T cells in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res.21, 4062–4072 (2015). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reardon, D. A. et al. Effect of nivolumab vs bevacizumab in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: the CheckMate 143 phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol.6, 1003–1010 (2020). 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Assistance Publique—Hôpitaux de Paris. Safety and Efficacy of the ONCOlytic VIRus Armed for Local Chemotherapy, TG6002/5-FC, in Recurrent Glioblastoma Patients. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03294486 (2017).

- 17.DNAtrix, Inc. A Phase 1b, Randomized, Multi-Center, Open-Label Study of a Conditionally Replicative Adenovirus (DNX-2401) and Interferon Gamma (IFN-γ) for Recurrent Glioblastoma or Gliosarcoma (TARGET-I). https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02197169 (2018).

- 18.Bristol-Myers Squibb. A Randomized Phase 3 Open Label Study of Nivolumab vs Temozolomide Each in Combination With Radiation Therapy in Newly Diagnosed Adult Subjects With Unmethylated MGMT (Tumor O-6-Methylguanine DNA Methyltransferase) Glioblastoma (CheckMate 498: CHECKpoint Pathway and Nivolumab Clinical Trial Evaluation 498). https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02617589 (2023).

- 19.Lim, M. et al. Phase III trial of chemoradiotherapy with temozolomide plus nivolumab or placebo for newly diagnosed glioblastoma with methylated MGMT promoter. Neuro Oncol.24, 1935–1949 (2022). 10.1093/neuonc/noac116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engeland, C. E., Heidbuechel, J. P. W., Araujo, R. P. & Jenner, A. L. Improving immunovirotherapies: the intersection of mathematical modelling and experiments. ImmunoInformatics6, 100011 (2022). 10.1016/j.immuno.2022.100011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Totsch, S. K. et al. Oncolytic herpes simplex virus immunotherapy for brain tumors: current pitfalls and emerging strategies to overcome therapeutic resistance. Oncogene38, 6159–6171 (2019). 10.1038/s41388-019-0870-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenner, A. L. et al. Agent-based computational modeling of glioblastoma predicts that stromal density is central to oncolytic virus efficacy. iScience25, 104395 (2022). 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ling, A. L. et al. Clinical trial links oncolytic immunoactivation to survival in glioblastoma. Nature623, 157–166 (2023). 10.1038/s41586-023-06623-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eissa, I. R. et al. The current status and future prospects of oncolytic viruses in clinical trials against melanoma, glioma, pancreatic, and breast cancers. Cancers10, 356 (2018). 10.3390/cancers10100356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nassiri, F. et al. Oncolytic DNX-2401 virotherapy plus pembrolizumab in recurrent glioblastoma: a phase 1/2 trial. Nat. Med.29, 1370–1378 (2023). 10.1038/s41591-023-02347-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenner, A. L., Cassidy, T., Belaid, K., Bourgeois-Daigneault, M.-C. & Craig, M. In silico trials predict that combination strategies for enhancing vesicular stomatitis oncolytic virus are determined by tumor aggressivity. J. Immunother. Cancer9, e001387 (2021). 10.1136/jitc-2020-001387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Boeuf, F. et al. Synergistic interaction between oncolytic viruses augments tumor killing. Mol. Ther.18, 888–895 (2010). 10.1038/mt.2010.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bridle, B. W. et al. Vesicular stomatitis virus as a novel cancer vaccine vector to prime antitumor immunity amenable to rapid boosting with adenovirus. Mol. Ther.17, 1814–1821 (2009). 10.1038/mt.2009.154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Webb, E. S. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. J. Biomed. Res.32, 317–326 (2018). 10.7555/JBR.31.20160168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pardoll, D. M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer12, 252–264 (2012). 10.1038/nrc3239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Louveau, A., Harris, T. H. & Kipnis, J. Revisiting the concept of CNS immune privilege. Trends Immunol.36, 569–577 (2015). 10.1016/j.it.2015.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Surendran, A. et al. Agent-based modelling reveals the role of the tumour microenvironment on the short-term success of combination temozolomide/immune checkpoint blockade to treat glioblastoma. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther.10.1124/jpet.122.001571 (2023). 10.1124/jpet.122.001571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Falco, J. et al. In silico mathematical modelling for glioblastoma: a critical review and a patient-specific case. J. Clin. Med.10, 2169 (2021). 10.3390/jcm10102169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kronik, N., Kogan, Y., Vainstein, V. & Agur, Z. Improving alloreactive CTL immunotherapy for malignant gliomas using a simulation model of their interactive dynamics. Cancer Immunol. Immunother.57, 425–439 (2008). 10.1007/s00262-007-0387-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Banerjee, S., Khajanchi, S. & Chaudhuri, S. A mathematical model to elucidate brain tumor abrogation by immunotherapy with T11 target structure. PLoS ONE10, e0123611 (2015). 10.1371/journal.pone.0123611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khajanchi, S. The impact of immunotherapy on a glioma immune interaction model. Chaos Solitons Fractals152, 111346 (2021). 10.1016/j.chaos.2021.111346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khajanchi, S. & Nieto, J. J. Spatiotemporal dynamics of a glioma immune interaction model. Sci. Rep.11, 22385 (2021). 10.1038/s41598-021-00985-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swanson, K. R., Rostomily, R. C. & Alvord, E. C. A mathematical modelling tool for predicting survival of individual patients following resection of glioblastoma: a proof of principle. Br. J. Cancer98, 113–119 (2008). 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eikenberry, S. E. et al. Virtual glioblastoma: growth, migration and treatment in a three-dimensional mathematical model. Cell Prolif.42, 511–528 (2009). 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2009.00613.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Storey, K. M. & Jackson, T. L. An agent-based model of combination oncolytic viral therapy and anti-PD-1 immunotherapy reveals the importance of spatial location when treating glioblastoma. Cancers13, 5314 (2021). 10.3390/cancers13215314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Montigny, J. et al. An in silico hybrid continuum-/agent-based procedure to modelling cancer development: Interrogating the interplay amongst glioma invasion, vascularity and necrosis. Methods185, 94–104 (2021). 10.1016/j.ymeth.2020.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grimes, D. R., Jansen, M., Macauley, R. J., Scott, J. G. & Basanta, D. Evidence for hypoxia increasing the tempo of evolution in glioblastoma. Br. J. Cancer123, 1562–1569 (2020). 10.1038/s41416-020-1021-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benítez, J. M., García-Mozos, L., Santos, A., Montáns, F. J. & Saucedo-Mora, L. A simple agent-based model to simulate 3D tumor-induced angiogenesis considering the evolution of the hypoxic conditions of the cells. Eng. Comput.38, 4115–4133 (2022). 10.1007/s00366-022-01625-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malinzi, J., Basita, K. B., Padidar, S. & Adeola, H. A. Prospect for application of mathematical models in combination cancer treatments. Inform. Med. Unlocked23, 100534 (2021). 10.1016/j.imu.2021.100534 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karimi, E. et al. Single-cell spatial immune landscapes of primary and metastatic brain tumours. Nature614, 555–563 (2023). 10.1038/s41586-022-05680-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Omuro, A. et al. Nivolumab with or without ipilimumab in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: results from exploratory phase I cohorts of CheckMate 143. Neuro Oncol.20, 674–686 (2018). 10.1093/neuonc/nox208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duerinck, J. et al. Atim-38. Glitipni: a phase 1b clinical trial combining surgical resection with direct intracerebral injection of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncol.21, vi10 (2019). 10.1093/neuonc/noz175.037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eisenbarth, D. & Wang, Y. A. Glioblastoma heterogeneity at single cell resolution. Oncogene42, 2155–2165 (2023). 10.1038/s41388-023-02738-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seidel, J. A., Otsuka, A. & Kabashima, K. Anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 therapies in cancer: mechanisms of action, efficacy, and limitations. Front. Oncol.8, 86 (2018). 10.3389/fonc.2018.00086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghaffarizadeh, A., Heiland, R., Friedman, S. H., Mumenthaler, S. M. & Macklin, P. PhysiCell: an open source physics-based cell simulator for 3-D multicellular systems. PLoS Comput. Biol.14, e1005991 (2018). 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ghaffarizadeh, A., Friedman, S. H. & Macklin, P. BioFVM: an efficient, parallelized diffusive transport solver for 3-D biological simulations. Bioinformatics32, 1256–1258 (2016). 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bergman, D. et al. PhysiPKPD: a pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics module for PhysiCell. GigaByte2022, gigabyte72 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Savić, M., Kurbalija, V., Balaz, I. & Ivanović, M. Heterogeneous tumour modeling using PhysiCell and its implications in precision medicine. In Cancer, Complexity, Computation (eds. Balaz, I. & Adamatzky, A.) 157–189 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022).

- 54.Letort, G. et al. PhysiBoSS: a multi-scale agent-based modelling framework integrating physical dimension and cell signalling. Bioinformatics35, 1188–1196 (2019). 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gonçalves, I. G., Hormuth, D. A., Prabhakaran, S., Phillips, C. M. & García-Aznar, J. M. PhysiCOOL: a generalized framework for model calibration and optimization of modeLing projects. GigaByte2023, gigabyte77 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pietras, K. & Östman, A. Hallmarks of cancer: interactions with the tumor stroma. Exp. Cell Res.316, 1324–1331 (2010). 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.02.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang, G. et al. Tumor-associated microglia and macrophages in glioblastoma: from basic insights to therapeutic opportunities. Front. Immunol.13, 964898 (2022). 10.3389/fimmu.2022.964898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sadahiro, H. et al. Activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase AXL regulates the immune microenvironment in glioblastoma. Cancer Res.78, 3002–3013 (2018). 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ostermann, S. et al. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid population pharmacokinetics of temozolomide in malignant glioma patients. Clin. Cancer Res10, 3728–3736 (2004). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Strobel, H. et al. Temozolomide and other alkylating agents in glioblastoma therapy. Biomedicines7, 69 (2019). 10.3390/biomedicines7030069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hotchkiss, K. M. & Sampson, J. H. Temozolomide treatment outcomes and immunotherapy efficacy in brain tumor. J. Neurooncol.151, 55–62 (2021). 10.1007/s11060-020-03598-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saha, D., Rabkin, S. D. & Martuza, R. L. Temozolomide antagonizes oncolytic immunovirotherapy in glioblastoma. J. Immunother. Cancer8, e000345 (2020). 10.1136/jitc-2019-000345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Storey, K. M., Lawler, S. E. & Jackson, T. L. Modeling oncolytic viral therapy, immune checkpoint inhibition, and the complex dynamics of innate and adaptive immunity in glioblastoma treatment. Front. Physiol.11, 151 (2020). 10.3389/fphys.2020.00151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aquilanti, E. & Brastianos, P. K. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for brain metastases: a primer for neurosurgeons. Neurosurgery87, E281–E288 (2020). 10.1093/neuros/nyaa095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Preusser, M., Lim, M., Hafler, D. A., Reardon, D. A. & Sampson, J. H. Prospects of immune checkpoint modulators in the treatment of glioblastoma. Nat. Rev. Neurol.11, 504–514 (2015). 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ganesh, S., Gonzalez-Edick, M., Gibbons, D., Van Roey, M. & Jooss, K. Intratumoral coadministration of hyaluronidase enzyme and oncolytic adenoviruses enhances virus potency in metastatic tumor models. Clin. Cancer Res.14, 3933–3941 (2008). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Martinez-Quintanilla, J., He, D., Wakimoto, H., Alemany, R. & Shah, K. Encapsulated stem cells loaded with hyaluronidase-expressing oncolytic virus for brain tumor therapy. Mol. Ther.23, 108–118 (2015). 10.1038/mt.2014.204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Choi, I.-K. et al. Effect of decorin on overcoming the extracellular matrix barrier for oncolytic virotherapy. Gene Ther.17, 190–201 (2010). 10.1038/gt.2009.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang, W. et al. Efficacy of an oncolytic adenovirus driven by a chimeric promoter and armed with decorin against renal cell carcinoma. Hum. Gene Ther.31, 651–663 (2020). 10.1089/hum.2019.352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alvarez-Breckenridge, C. A. et al. NK cells impede glioblastoma virotherapy through NKp30 and NKp46 natural cytotoxicity receptors. Nat. Med.18, 1827–1834 (2012). 10.1038/nm.3013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Han, J. et al. TGFβ treatment enhances glioblastoma virotherapy by inhibiting the innate immune response. Cancer Res.75, 5273–5282 (2015). 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.The MathWorks Inc. MATLAB version: 23.2.0.2485118 (R2023b). (2023).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Datasets resulting from simulations and needed for reproducing figures in the current study are available on Github: https://github.com/blanchemongeon/ABMGBM. Any further datasets are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

The computational code to implement our agent-based model is available on GitHub at https://github.com/blanchemongeon/ABMGBM.